4 minute read

THE ENERGY CONUNDRUM

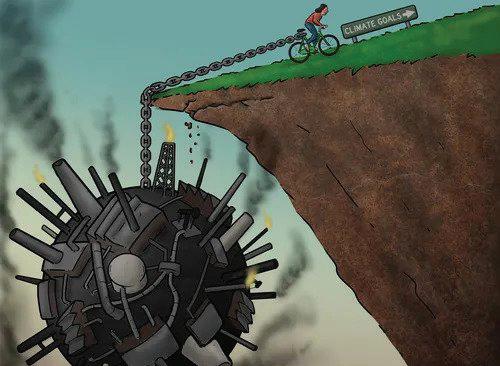

India must balance out its net zero emission goals with the aspirations of its billions.

Widely dubbed as the ‘COP of Implementation’, the recently held 27th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP27) witnessed, among other nations, India’s submission of its Long-Term Low Emissions Growth Strategy. This was particularly significant in the context of the Prime Minister Office’s announcement of the nation’s pledge to achieve net zero emissions by 2070.

Advertisement

One of the most fundamental aspects of the document was the plan for scaling up green hydrogen production at a swift pace in a bid to further the de-carbonisation of India’s transition to clean energy.

BANKING ON RENEWABLES?

As the world’s fifth-largest economy with the second-largest population base (the largest by the end of 2023), India’s hunger for energy is only surpassed by that of China in the Indo-Pacific. As the nation of 1.3 billion strives to meet the demands of the burgeoning upward mobility of its population, there are stark contradictions in its ostensibly ambitious goalposts for achieving net zero emissions and the challenge to make its population prosperous.

A Harvard University study has claimed that renewable energy such as wind and solar can be effectively harnessed to defenestrate India’s overwhelming current reliance on coal-seventy per cent of the country’s electricity requirements are currently met by coal. Renewables can fulfil as much as 80 per cent of India’s energy demands by 2040 if the right steps are taken today. The study further claims that such a change would reduce India’s carbon emissions by a whopping 80 per cent.

Other weapons in the green arsenal of India include increased use of biofuels like ethanol blended in petrol (20 per cent by 2025), deeper EV penetration and using green hydrogen in the transport segment. More importantly, there is a significant shift towards mass public transport for moving freight and passengers.

The salient aspects of India’s Long-Term Low Emission Development Strategy include making the country a green hydrogen hub. This would entail the rapid expansion of green hydrogen production and increasing electrolyser manufacturing capacity in the country. In addition, a three-fold increase in nuclear capacity by 2032 is planned.

CHANGING END-USE PATTERNS

Other weapons in the green arsenal of India include increased use of biofuels like ethanol blended in petrol (20 per cent by 2025), deeper EV penetration and using green hydrogen in the transport segment. More importantly, there is a significant shift towards mass public transport for moving freight and passengers. Billions are being expended in creating expensive metro train networks in all major cities to reduce traffic and carbon emissions. Future sustainable and climate-resilient urban development will be driven by smart city initiatives, integrated planning of cities for mainstreaming adaptation and enhancing energy and resource efficiency, effective green building codes and rapid developments in innovative solid and liquid waste management.

Pitfalls And Their Solutions

The resultant quandary lies herein- India cannot afford to abandon a major fuel source like coal and oil to meet its people’s energy and electricity needs, not yet, at the very least. And so, the question that requires further exploration is the short-term and long-term strategies to be deployed in ushering a faster switch to renewable energy, the sources of which, particularly wind and solar, are generously endowed in the nation.

In addition to solar and wind power, the Indian government’s National Hydrogen Mission has finally materialised into a palpable financial engagement, with the Union Cabinet having declared an outlay to the tune of INR 19,744 crore as of January 4. This by itself is a very encouraging move. The recent COP27 commitments outlined by India have certainly played a crucial role in pushing the wheel forward in operationalising key policy decisions made previously. However, the dilemma of a sustained and rapid transition to cleaner energy continues to persist in light of India’s rising subsidies for fossil fuels.

In 2022, the country’s subsidies for fossil fuels such as gas, coal, and oil were deemed to be nearly nine times higher than subsidies for renewable energy as well as electric vehicles. These subsidies have taken the form of price regulation, financial incentives, as well as direct subsidies. They only highlight the need for a change in these subsidies’ direction to channel them increasingly towards renewable energy sources to realise the nations’ international and national obligations and targets. Even so, the discourse in India and several countries in the Global South remains focussed on creating a ‘loss and damage fund’ largely sustained by the Global North. This is an acrimonious demand and more so when the rich nations face an energy crisis, recession and historically high cost of living.

Therefore, the agreement that has emerged in COP27 for the creation of such a loss and damage fund is the best news heard on the climate front for a long time. This, along with the reiteration that countries responsible for the highest carbon emissions, will compensate vulnerable countries reeling under the impacts of climate change most acutely.

In the Indian context, a painful fact is that while India remains a major carbon-emitting country, it is also one that is amongst the most severely affected by climate change. Therefore, a push to transition to clean energy at the required scale of mitigation necessitates that funding streams from multilateral organisations such as the World Bank and the IMF are fortified for implementation to occur synergistically and comprehensively.

Assessment

India must ensure that the industry’s drive towards low-carbon development transitions should not impact energy security, energy access and employment. The transition must be seamless, equitable and carefully calibrated.

The transition to green energy will not be cheap and entail the high cost of developing and adapting new technologies, creating new infrastructure and other transaction costs. To meet these costs, amounting to trillions of dollars by a conservative estimate, India will have to turn to climate financing by international investors and global multilateral institutions against the stiff competition by other aspiring nations.