SwedishLapland

THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE culture | people | nature | taste | design

2 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE 61° anchorage , alaska 64° reykjavik , iceland 66°arcticcircle68°abisko Photo: Me and Leila

swedish lapland

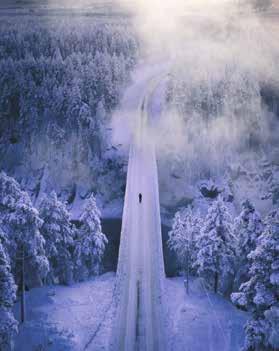

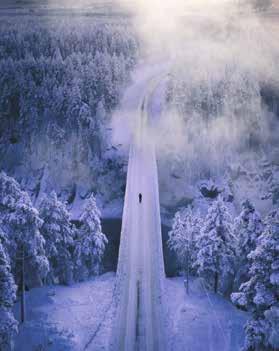

We define the destination Swedish Lapland in a hundred ways or more. For the mountains, forests and wetlands, and for the major rivers flowing continuously to the sea and the archipelago. For the people who live here and for the broad, untouched expanses of untamed nature. For the art, music and literature. For a cultural landscape and for wildlife. Naturally, our everyday arctic lifestyle also defines us as people. The seasons, distances and climate have not only dictated a special way of life, but also a life in which nature is a major aspect, almost like a religion.

Of course, for many, the geographic boundaries of Lapland, drawn by rulers many hundreds of years ago, are more important than the actual soul of the place. But what we are trying to define is an arctic soul. But what is that?

Indigenous people lived here long before a Swedish king moved the boundaries for his domain farther north. The king's men called these people Lapps, but they called themselves the Sámi and their homeland Sápmi. Sápmi is a borderless land that stretches across the entire Nordkalotten region, from northernmost Norway, over northern Sweden, into northern Finland, all the way to the Kola Peninsula in Russia.

Swedish Lapland

Sápmi

Swedish Lapland represents the Swedish part of the Arctic region, shared with six other countries: USA (Alaska), Denmark (Greenland), Norway, Finland, Russia, Canada and Iceland.

How far north is Swedish Lapland actually? For example:

• Whistler in Canada has the same latitude as Frankfurt in Germany at 50° north.

• Hokkaido in Japan has the same latitude as Rome in Italy at 43° north.

Today we also refer to this region as Arctic Europe. It is a part of the world that has become increasingly interesting for major political powers, foreign investors and oligarchs. Naturally, this destination, Swedish Lapland, is a vital part of the global fabric, but it has been shaped since time immemorial in a multicultural melting pot. Via our neighbours to the east and west – Finnish Lapland and northern Norway – we are the only part of Sweden to share national boundaries with two countries. And, somewhere at this intersection, there is something that we wish to define as a unique lifestyle. Amid the clatter of reindeer hooves, fiery sermons and weathered log cabins, something very exciting has emerged. It is an everyday arctic lifestyle deeply rooted in nature that we wish to share. We live our lives under the northern lights and the midnight sun, amid hail and black flies, wet snow and intense sunlight.

We dry our meat in the spring, smoke our fish in the summer and boil our coffee over an open fire all year round. And we put 'coffee cheese' in our boiled coffee, because we love the taste and the squeaky sound it makes between our teeth.

For us, Swedish Lapland is not really a place, but rather a way of life. And you are welcome to share it with us. /

ED.

3

SÁPMI

map

INTRO

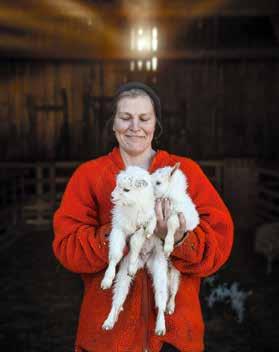

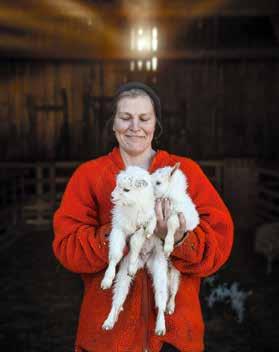

Maj-Doris Rimpi is all that Arctic lifestyle personalised. A reindeer owner, mother, model, artist, and actress. You have probably seen her in the film Sameblod (Sami blood, 2016), and her handicraft is, of course, award-winning. In the winter, before she feeds her tame reindeer the hand-picked lichen, she will cleanse it from dry and sharp pine needles. That tells you all you need to know about this lady’s character.

PHOTO Carl-Johan Utsi

EDITOR’S NOTES

At the editorial office of this magazine, we know that we are fortunate. As we, every day, wake up at one of the best places in the whole wide world. We also know why. Thanks to all the hard-working entrepreneurs and enthusiasts, that make this place ticking. Whether it’s braving this year’s first snowstorm to take care of the reindeer herd, or staying late at night tending guests at the restaurant, working every morning to get the best local produce, or just maintaining the ski slopes – we all owe you thanks! We know that this magazine wouldn’t be possible without all your contribution and support.

This edition wouldn’t be possible either without the contribution from some of the industry’s finest. Maria Broberg and David Björkén, thanks for your words. Andy Anderson, Per Lundström, Tor L. Tuorda, Carl-Johan Utsi, Linus Granberg, Daniel Olausson, Anthony Tian, Sandra Hansson, Andreas Nilsson, Me and Leila, Cody Duncan, Viggo Lundberg, Philipp Herfort, Asaf Kliger, Linda Broström, Dan Norin, Jens Wennerberg, Anders Bobert, Graeme Richardson, Mattias Fredriksson, Tobias Hägg, Sven Burman, Peter Rosén, Pernilla Ahlsén, Thomas Larsson, Fredrik Broman, The Common Wanderer, Linnea Isaksson, Carina Forsén and David Björkén for your amazing work with the cameras. Leila Nutti and Lisa Wallin for your beautiful illustrations. Mark Wilcox and Mia Linder for spot-on translations. And Josefine Ås for a pair of extra eyes. Finally, if we hadn’t been so busy having fun, we would had finished this edition last year – so we won’t promise when the next issue will appear. But somehow it will. Until then, stay safe and see you soon.

THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

The Arctic Lifestyle Magazine is a standalone publication, published by Swedish Lapland Visitors Board – the regional representative of the tourism industry in Sweden’s arctic destination, Swedish Lapland. Opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author, or persons interviewed and do not necessarily reflect the view of the editors.

EDITORIAL Swedish Lapland Visitors Board in collaboration with the regional network of communicators. Contact us at redaktionen@swedishlapland.com

PRINT Lule Grafiska, Luleå.

SWEDISH LAPLAND® is a registered trademark used as destination brand of Sweden’s northernmost destination. The region includes the municipalities of Arjeplog, Arvidsjaur, Boden, Gällivare, Haparanda, Jokkmokk, Kalix, Kiruna, Luleå, Pajala, Piteå, Skellefteå, Sorsele, Älvsbyn Överkalix and Övertorneå.

4 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE CONTENTS

THE COVER

THE ATLANTI C NORWAY 70 42 78 94

culture people taste nature design

THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

SwedishLapland

SWEDEN

5 CONTENTS V N D E LÄ LVEN LAINIO RIVE R A R C T I C C I RCLE FI N L A N D e4 e4 PITE RIVER L ULE RIVER R Å N E RIVER K A L X R I V E R TO IV E R LAKE TORNET R ÄS K A R C H I

SKELLEFTERIVER B VINDEL RIVER MÄÄ RIVER M U O N I O R I V ER KIRUNA GÄLLIVARE ÖVERKALIX ÖVERTORNEÅ PAJALA KALIX BODEN ARVIDSJAUR ÄLVSBYN HAPARANDA LULEÅ JOKKMOKK ARJEPLOG PITEÅ SKELLEFTEÅ SORSELE 18 11 84 63 Illustration: Lisa Wallin

The places we go to

Visiting Swedish Lapland is about rich cultures and enchanting natural vistas. From the mountains to the sea, over the rolling hills deep into the wooded valleys, along ancient trails and winding roads, these are the places we go to.

FACTS:

• Laponia became a world heritage in1996.

• The world heritage consists of Sarek, Padjelanta, Stora Sjöfallet and Muddus national parks, as well as the nature reserves Sjávnja and Stubbá. The areas Tjuoldavuobme, Ráhpaäno sourgudahka and Sulidäbmá are also included.

• Laponia is approx. 9,400 square kilometres, a bit larger than Cyprus.

6 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE SIGHTS

1

Photo: Linus Granberg

2Gammelstad church town

In 1996 the church town in Gammelstad outside Luleå was appointed a World Heritage Site by the UN agency Unesco. The red church cottages are a legacy from a time when there was an obligation to attend church in Sweden. The farmers in villages around Gammelstad church town needed somewhere to stay the night to be able to attend service. Some of them lived as far as 40 km from church, and it took time to get there, even using a horse and carriage. That is why these red overnight cottages were built and created a little town of their own. There used to be 71 church towns in Sweden and only 16 remain. Gammelstad is the best-preserved church town and as such it has a unique universal value for humanity that is worth preserving.

directions: Gammelstad is easily accessible by car, only 10 kilometres northwest of central Luleå, with signs from road 97. www.lulea.se/gammelstad

Go west

In 1996 Laponia was granted the same status by Unesco, for its outstanding universal values. Laponia is unique as a World Heritage Site because it has been appointed for its rich culture as well as its natural values. Most other World Heritage Sites are named for one of these values, rarely for both. In Laponia there is, and there will be, a living Sámi nomadic culture, and at the same time it offers one of Sweden’s most unique nature experiences. Everyone can visit Laponia – the E45 road passes through the world heritage site at the edge of Muttus national park. But above all, the Road West, BD 827 to Ritsem – sometimes known as ‘the longest cul-de-sac in Sweden’ – is a fantastic opportunity, also for the disabled, to get an insight into one of Europe’s most beautiful natural and cultural heritages.

directions: The easiest way to visit Laponia is by car on road E45 from Jokkmokk or Gällivare. www.laponia.nu

To measure the world

The Struve Geodetic Arch is the third of Unesco’s World Heritage Sites located in Swedish Lapland. But the ‘arch’ actually extends from Hammerfest in Norway down to the Black Sea. Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve wanted to measure the curvature of the globe, to be able to determine its shape and size. In the beginning the chain of measuring points crossed three countries: Sweden, Finland and Russia. Nowadays the chain extends through 10 countries along its 2,820 km-long stretch. There are four measuring stations in Sweden, in Kiruna, Pajala, Övertorneå and Haparanda municipalities.

directions: Driving road 99 along Torne river, between Haparanda and Karesuando, you will pass crossroads to the stations. bit.ly/StruveKiruna

FACTS:

• 520 culture-historically valuable and protected buildings, of which 405 are church cottages.

• The unique environment consists of the 15th-century stone church with surrounding church cottages, a medieval network of streets and buildings stemming from the 17th-century burgher town.

• World heritage since 1996.

FACTS:

• The Struve Geodetic Arch runs through ten countries: Norway, Sweden, Finland, Russia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine.

• There are seven station points in Sweden and four of them are on the world heritage list, situated on the mountains of Tynnyrilaki, Jupukka, Pullinki and Perävaara.

• The points are marked by drilled holes in rock, iron crosses, cairns or obelisks.

• World heritage since 2005.

7 SIGHTS

Photo: Ted Logart

Photo: Dan Norin

The sculpture ‘von Struve’s Triangle’ , is overlooking Nedertorneå kyrka on the Finnish side of the Torne River. The 40 metre high church tower is one of six World Heritage measuring points in Finland.

A slow train

Inlandsbanan, the 1,288 kilometers long railway between Kristinehamn and Gällivare, is an attraction in the summer. And of course, the part running through the destination of Swedish Lapland is a high note. Stays in Sorsele, Arvidsjaur, Jokkmokk and Gällivare comes natural. On Fridays and Saturdays, in July and August, a steam train runs back and forth Arvidsjaur and Slagnäs, a perfect happening.

directions: The Inlandsbanan stops in Sorsele, Arvidsjaur, Jokkmokk and Gällivare. res.inlandsbanan.se/en

Grodkällan – the Frogs’ den

The spring Tsuobbuojája, or Grodkällan as it is named in Swedish, is situated on the bog Slengmyran not far from Lomträsk village in Arvidsjaur. The spring has been a place to visit for years. And last year the trail and the facilities around the spring were refurbished.

directions: From Arvidsjaur, take the E45 north. After Auktsjaur, follow the gravel road towards Lomträsk, and then follow the signs to the spring. bit.ly/grodkallan

The Arctic Circle

The northern polar circle is known as the Arctic Circle. Its position is 66˚ 33’ 38” N, but the truth is that the Arctic Circle moves a little bit every year because of the gravity of the Earth and the moon. You could say that the Arctic Circle is the place that defines the midnight sun and the midwinter darkness, based on the summer solstice or the winter solstice. In the destination Swedish Lapland, you cross the Arctic Circle in several places. You can swim, bike, hike or just enjoy the crossing through a train or car window.

directions: By car, you can cross the Arctic Circle just south of Jokkmokk on road E45 or 97, in Juoksengi on road 99, in Överkalix along road E10, in Jockfall on road 392 as well as in Merkenes on road 95. By train, you pass it in Murjek.

8 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE SIGHTS

6 5

Photo: Ted Logart

Photo: Per Lundström

4

Photo: Håkan Stenlund

Storforsen rapids

The largest unregulated rapids in Europe, with a fall of 82 metres. On average 250 m3/s whirls past in the current. It is a powerful spectacle, and it is easy to understand why Storforsen is one of our most popular excursion destinations. In summer, the rapids also attract plenty of sun lovers, as the dried-up rocks heat up and some of the overflowing water creates excellent pools for bathing.

directions: Follow road 374 40 km northwest of Älvsbyn, or drive south from Jokkmokk for 100 km, first on the E45 and then left on road 374. storforsen-hotell.com

9 SIGHTS

Photo: Jens Wennerberg

7

The salmon show

The mighty Jockfall, on the river Kalixälven, is always an interesting sighting. In July, from the bridge at the fall, you have a front-row view of some of the world’s biggest salmons trying to jump the fall. Kalixälven is one of Sweden’s four National rivers. The others being Torne-, Pite- and Vindelälven.

directions: From Överkalix, drive north on road 392 along Kalixälven. When the road makes a right turn towards Pajala, just go straight on along the river. jockfall.com

The Jokkmokk market

For more than 415 years, on the first week of February, the Jokkmokk market has been a unique part of the Sápmi experience. People from all corners of the world meet here, but above all relatives and friends from the geographically dispersed Sápmi meet up. Ask anyone in Jokkmokk and they will tell you that with regard to the market there is a before and an after. It is the real beginning and end of the year. The market showcases the best Sápmi has to offer in terms of culture and design. You do not want to miss the art exhibition at Sámij åhpadusguovdásj, the handicraft exhibition at Ájtte, the inauguration, the meat soup at Akerlunds and the Sámi Duodji exhibition, and more.

directions: In the town of Jokkmokk. jokkmokksmarknad.se

An iconic silhouette

uonjávággi or goose valley, if translated from northern Sámi language, is Sweden’s most iconic landmark. The u-shaped valley, south-east of Abisko, is the most photographed scenery of the north. The valley, a remain of the last ice age, immediately draws attention to itself, with a classic silhouette.

directions: Go by train or car, from Abisko towards Kiruna, to enjoy this iconic view. Or just sit down in the restaurant at Hotell Fjället in Björkliden. bjorkliden.com/en

10 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE SIGHTS

Photo: Per Lundström

8 9

Photo: Tobias Hägg

Photo: Carl-Johan Utsi

10

THE GRAFFITI of gentleness

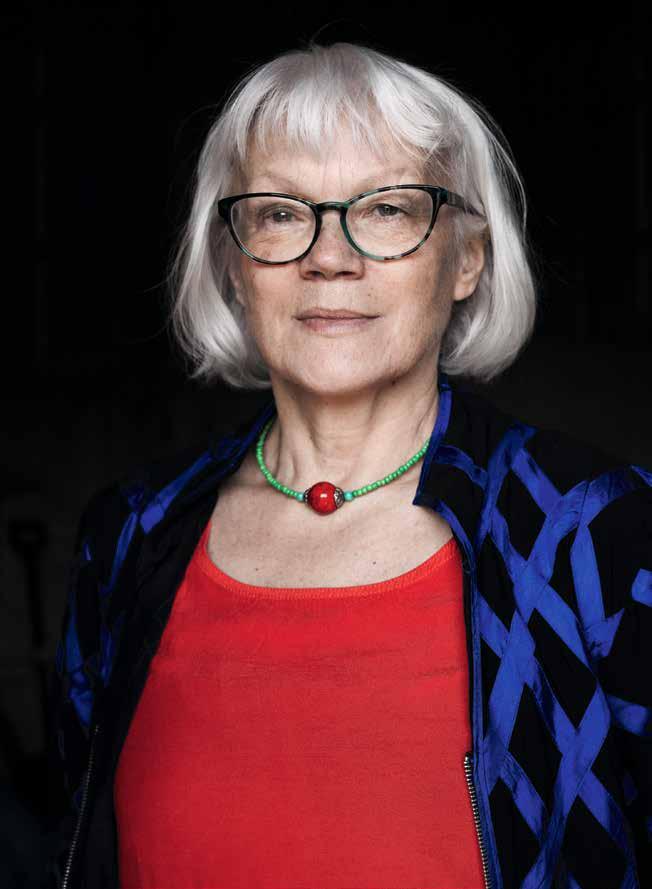

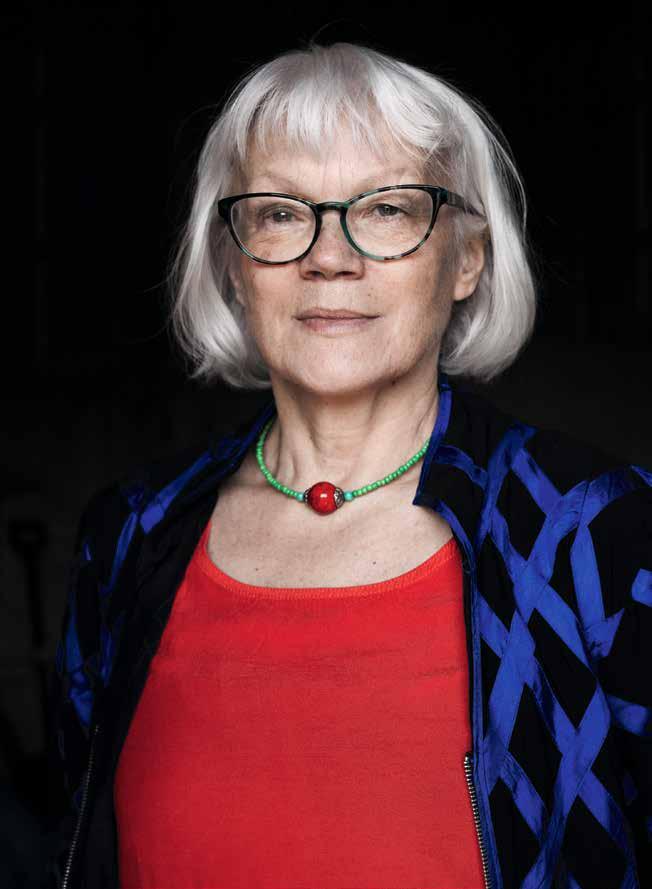

She celebrates her 40 th anniversary as an artist, Sámi narrator Britta Marakatt-Labba. This is also how long it has taken Swedes to discover her art. The breakthrough was international for this resistance artist who tells her story with the needle as a brush.

11

PEOPLE

TEXT & PHOTO: HÅKAN STENLUND

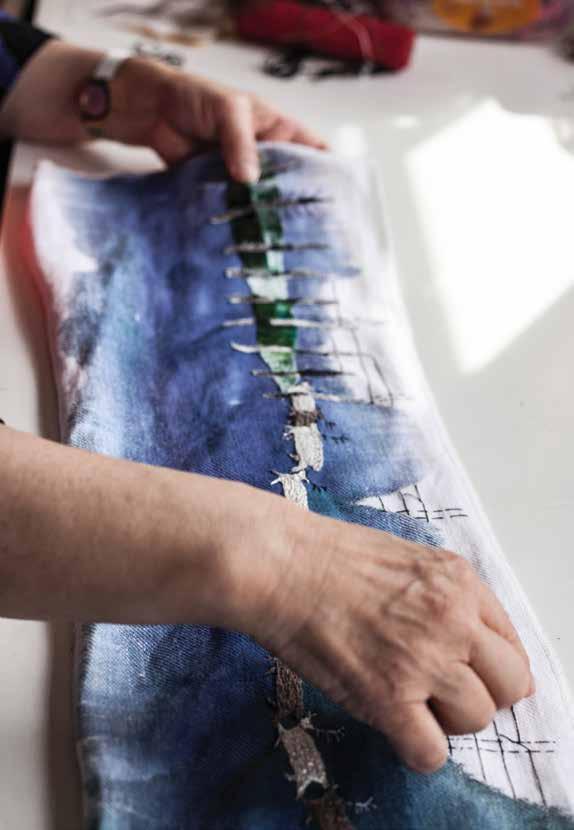

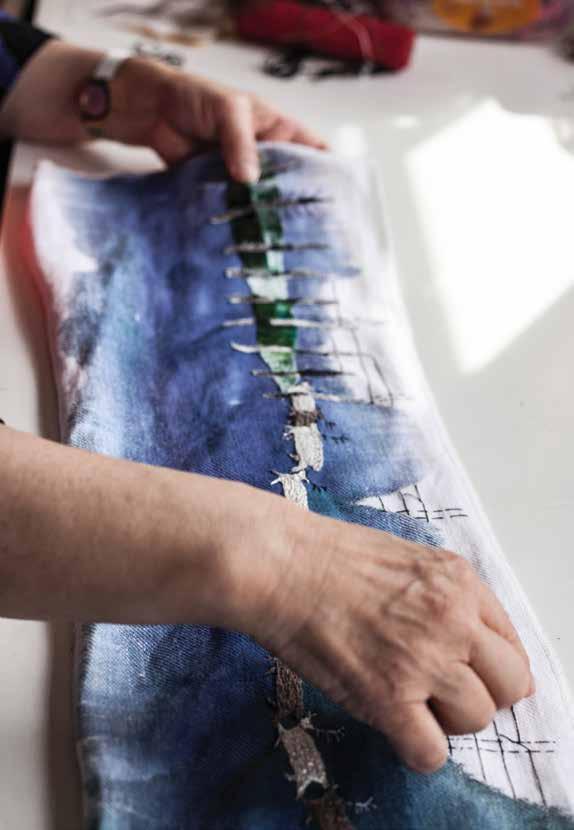

the needle powerfully penetrates the white cloth, almost like a skier moving across untouched snow where poles and skis sink into the newly fallen snow to slowly create a pattern. The skier – or the needle – slowly embroiders Sámi history. Huts and snowmobiles, shamans and deforested land, reindeer and humans, the mundane and the mythical, good and evil. Everything finds its place in Britta Marakatt-Labba’s embroidery.

Today, as we meet her in her home in Övre Soppero, she has just returned from a European trip. Despite 40 years of diligent work, it took an international breakthrough to get noticed in Swedish cultural life. An international breakthrough at the same time as other artists in Sámi contemporary life were given more space too. With people like Anders Sunna and Sofia Jannok, the film Sámi Blood and the winner of the August Prize, Linnea Axelsson’s Ædnan, the Sámi have begun to gain their rightful place in general culture.

“Yes, but I worry it’s just a wave, a trend, and that we’ll soon be forgotten again”, says Britta while she cooks mashed potatoes and souvas.

“When you’ve driven that far, you have to eat something. Would you like gáhkku and coffee first?”

Of course I say yes, please. The Sámi culture is a culture of hospitality and I would be foolish to say no, when offered home-baked bread and mashed potatoes by a popular Swedish artist. As I sit down, drinking my coffee I wonder if all the curators and managers from the world’s art galleries and museums who are on their way to Övre Soppero will be as lucky. Then I have a refill.

when britta started with her art in the 1970s people could hardly believe their eyes. Embroidery wasn’t exactly

trendy then, and people tended to refer to their grandmother’s old-style kitchen tapestries. Some kind of kitsch.

“Yes, I remember many people wondered. Many said I should paint instead of wasting my time.”

“But I liked it this way. The textile material allows me to express myself.”

For Britta there is a point in taking her time, as it allows for reflection –perhaps we could call it the aesthetics of slowness, or the graffiti of gentleness. It goes without saying: if you are making a 24-metre-long tapestry like the famous Historjá at Tromsö University, you have time to think about what it is you want to express.

Between 2003 and 2007 Britta worked at that piece or art, where stitches were added to stitches along the path of Sámi history. Historjá was shown at the large art exhibition Documenta in Kassel, Germany, and this meant that a great number of people discovered Britta Marakatt-Labba. Internationally it became a huge success and suddenly Swedish press also realised that something very special was going on in Övre Soppero. But the world very nearly missed the whole excitement, by a hair’s breadth.

“Yes... well, first I said I didn’t want to participate. But then a colleague called and said I “had to” participate, that I’d be crazy not to, and then I changed my mind.”

“I don’t know what to say. Of course it’s great to be noticed after 40 years’ worth of work, at the same time it just takes up so much time.”

britta was born in Idivuoma in 1951. Her mother had twelve children, two of whom died, and Britta grew up with nine siblings in the Sámi administrative unit Saarivuoma. One Christmas Eve

12 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

PEOPLE

Everything finds its place in Britta Marakatt-Labba’s embroidery and art. From nature to myth. And she, herself, is now exploring new fields for her art.

her father went out to see to his reindeer and was hit by a taxi travelling from Finland. He died. Britta was five years old. She was sent to the nomad school in Kiruna, which she describes as misery, in a time and town full of racism and contempt towards the Sámi. Then she chose the college for adult education in Sunderbyn before continuing to the School of Design and Crafts in Gothenburg. A time she describes as yet another extreme. As a Sámi she was considered exotic. The two extremes have left their mark: the feeling of being there, but never really being part of the context.

The potatoes on the cooker are done and Britta peels them as we chat. She is careful with details. To make proper mashed potatoes you should not peel the potatoes before you boil them, “no, then the mash will be watery and tasteless”, you peel them afterwards. The minerals and flavours are left, and it gets thicker.

“I like details and organisation. In that sense my studio probably doesn’t look like that of other artists”, she says and chuckles.

We enter the studio, a fairly simple room, bright and tidy, and not very big.

“Did you make Historjá here?”

“Yes, exactly, over there at the table with the pincushions. I had it on a roll, and embroidered one length at the time.”

“But 24 metres?”

“I know, it wasn’t ideal. First, I made a 16-metre section, and then I made another one that was eight metres long. I should have made several sections of four metres each instead, that would have been easier.”

Everything is about images, images that exist inside Britta’s head, slowly travelling down the white fabric of her embroidery. She treasures her images. She worries they will disappear. But this is also a practical problem. To get orders

The slow work of embroidery also gives Britta time to reflect on the story she wants to tell, some stories take years.

13

PEOPLE

14 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE PEOPLE

from larger institutions, those with money, she needed to be able to show sketches. But Britta was not able to turn her images into sketches, instead she cut and pasted various collages to show her ideas. Today it is easier, these days she also makes illustrations.

in the studio there are a set of stone sculptures sitting on wooden logs. I ask her who made them and she answers that it is her work.

“What?”

“Yes, I’ve started going to the stonepolishing workshop in Lannavaara. It’s damn hard work, but it’s fun.”

“But what does it feel like? I mean, going from needle and thread and soft fabrics to big noisy machines that polish stone. There is a difference, surely?”

“As a child I loved stones. Our reindeer herding land is in Norway. I used to play with stones there, stones that would become other things in my imagination.”

Before I know it, Britta sits down on a low stool in the studio and starts carving on a piece of wood.

“I have taken a course in wood carving as well. This is how we used to sit in my childhood, together around the fire, crafting and telling stories.”

As Britta Marakatt-Labba sits on her stool carving she conveys in a very steadfast manner that she is well aware of not being finished with her art at all. There are lots of things left to do. Many stories left to tell.

when she started with her art many laughed at her embroidery. They said: “But why don’t you paint instead? You’ll never finish that.” Now she has noticed how a lot of other artists have started with embroidery. But Britta herself has never been interested in anything else but being able to tell her images. “First, I could do it through my embroidery needle, now I can use other tools too.”

“It’s impressive that now that you have the opportunity to make money on your embroidery you choose other paths or expressions. Why?”

“I’m not interested in money. If that had been important to me, I’d never have started embroidering resistance art in the first place. Getting that breakthrough isn’t something that’s been a driving force either.”

“But sure, I could travel all the time if I wanted to, talking about myself and my art, you know, lectures, but it’s no fun. I want to tell stories.”

in 1981, once Britta had finished her education in Gothenburg, she joined the protest against the power plant expansion by the Alta River in Norway. She ended up in prison, as did many of the others who protested.

One of her first and strongest pieces of art is Garrját, or ‘The Crows’. The crow has always been a symbol of authority to the Sámi, a creature that grabs everything it can. In Garrját they fly across the protesters in Alta, but as

15

PEOPLE

“I’m not interested in money. If that had been important to me, I’d never have started embroidering resistance art in the first place.”

they land, they turn into police officers. The state authority that came there to carry out government work, grabbed the rapids and the land, and freedom, and stuffed electricity into its own pocket. Another piece of political work that has received a great deal of attention is Deattán, or ‘Nightmare’. Looking at one of its details you can see rats invading a Sámi hut. Many are struck by the terrible sight of rats eating the sleeping people around the fireplace, but an equally important symbolism is the number of rats that have invaded the most sacred spot in the hut – the kitchen area. No one was allowed to be there, just the housewife. You could only behave in a certain way there, using certain patterns of movement. The goddess Sáráhkká was the guardian of the home, but also the guardian of female reindeer during calving, and pregnant women in the home. Sáráhkká is perhaps the most beloved goddess in Sámi mythology, worshipped by both men and women. Having rats invade her world carries a strong symbolism in Deattán.

the entire life of the sámi is based on storytelling. The written word came late, and the oral story carries the culture.

As Britta and I talk today, I can hear how she talks in images. For example, when we speak about how it took 40 years of embroidery for her to get a breakthrough, she first says that she has never been keen to change her way of

working just because something else has been trendier. How other artists have been inclined to change their form of expression – she uses the word ‘turncoats’ – and then her imagery comes in:

“You know, they’re more like a spring fire jumping from one tuft of old grass to the next. What happens is that those old tufts flare up, the ground gets slightly burnt, but it doesn’t burn deep.”

“Sure, green grass will grow there quickly, but the animals don’t like it. It’s pretty to look at, but of little use.”

deattán is about another kind of violation, not the kind that takes place in public, visible to others. The Sámi live by and from nature and are in a way bound to the soul of nature. The rats invading Sáráhkká’s kitchen area is also a violation of Sámi mythology, as it affects the land. A tree is more than just a tree, a fish is not just a fish, and a cloudberry is more than just a berry.

“When the Sámi pick berries or catch fish, they say a kind of prayer: ‘Do not let my hands ruin the land that I have borrowed’.”

“Life is constant interaction between event and mythology.”

Sámi culture is colourful and ornate in so many ways. Traditional costumes and jewellery are full of expression and provide a parade of colour. But Britta Marakatt-Labba’s art has always been low-key and almost graphic. Why?

“Why? Well, because that’s how I see my images.”

16 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

PEOPLE

For generations, life in Sápmi was based on oral storytelling. In her studio, Britta Marakatt-Labba gives color and life to the stories and myths of the past.

17

Photos:

Carl-Johan Utsi

PEOPLE

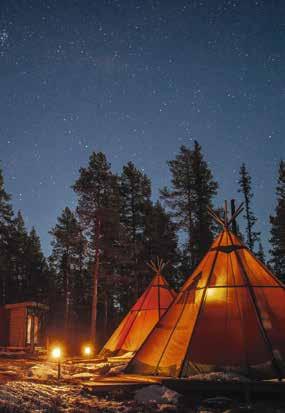

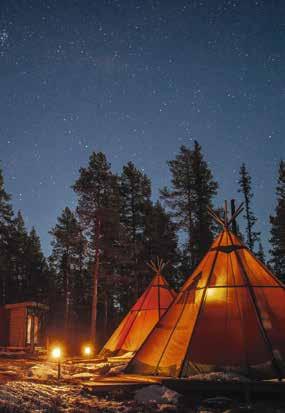

OUR TILTED WORLD

If you visit Swedish Lapland during the summer, you’ll notice that it never gets dark. You have entered the world of the midnight sun, an extraordinary experience that might affect your sleep quality. In other times of the year, you probably don’t want to sleep either since you want to enjoy another light show of sorts.

18 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

TEXT & PHOTO : DAVID BJÖRKÉN

NATURE

19 NATURE

the arctic circle marks the southernmost point at which the centre of the sun is visible during the June solstice. The summer solstice is the time of the year when the sun is always visible –the sun just never sets. In the northern hemisphere, the summer solstice falls around June 21 and the farther north you are, the longer is the polar day.

In reality, the Arctic Circle is not an absolute border – you can see the midnight sun as far as 90 kilometres south of the Arctic Circle. There is also a

slight variation from each year and varies depending on the topography.

in the sámi language, the sun is called Beaivi, but Beaivi is also the goddess of the sun and has a central place in Sámi mythology. Every year – back in the days – a white reindeer was sacrificed as an assurance that the sun would return after the long and dark winter. At the summer solstice, they tied together rings of leaves and flowers which was put up to honour the goddess. You could find this custom today in the traditional Swedish midsummer celebration – a tradition that might have pagan roots. But there is no known historical link between the Sámi custom and the old Nordic one.

It is also said that when the sun returned, they prayed for the feebleminded because they thought that mental illness was induced by the long and dark winter. As we should learn further down, we are indeed affected by the light in different ways, a custom that has scientific support. As a first-time visitor it can be a challenge to cope with. That the Sámi adored the sky was nothing different from the rest of the world. The stars have always captured our interest. Wherever they could be seen.

but, as you know, our amazing night sky has more to offer than midnight sun and northern lights. Yes, during the dark part of the year, we often get to enjoy the dance of aurora borealis. A magic show created by charged particles from the sun accelerated by the Earth’s magnetic field towards the poles where they collide with particles in the upper atmosphere: the origin of the northern lights. But experiencing the starry sky on a clear night without northern light, or moonlight, is almost as fascinating.

20 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

Aurora borealis – the northern lights – is visible from August until April.

NATURE

Photo: Cody Duncan

21

NATURE

The North America Nebula (NGC 7000) in the constellation Cygnus photographed from a location close to Jokkmokk. The shape of the nebula resembles that of the continent of North America, complete with a prominent Gulf of Mexico.

22 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

NATURE

Photo: Mattias Fredriksson

Standing in the dark, looking up and seeing the multitude of stars in the Milky Way stretching out across the sky. Discovering the tiny, blurred spot in the constellation Andromeda, the most distant object we can see with our naked eye – our spiral galaxy neighbour M31, the Andromeda Galaxy, located some 2.2 million light-years away. Marvelling at the tiny group of twinkling stars that make up the small open-star cluster The Pleiades. Or watching the mighty constellation Orion extend across the starry sky in wintertime.

It’s an almost overwhelming feeling as I stand there in the dark. Not only does it remind me of our own smallness, in relation to our universe. It also gives a sense of contact with our own history – our human history. I stand there in awe looking at the same stars as our ancestors did. There is something profound and existential about this, and you get a sense of why the starry sky with its different phenomena has been so important to mythologies and the creation of stories for all time and all folks.

in general, we are not aware of the precision in the timing and coordination of numerous events in our bodies, unless it’s disrupted (most of us know the feeling of being jet-lagged). However, processes as fundamental as the timing of sleep and its coordination with feelings of hunger are a manifestation of numerous physiological and biochemical events that change systematically and predictably throughout the day.

Light is essential for a lot of nonvisual functions: synchronisation of our biological clock, stimulation of human alertness and cognition, memory, reproduction, energy balance, to name a few.

The mechanisms underlying the positive effects of light for mammals remain

23

NATURE

The midnight sun

What is the midnight sun

the midnight sun is a natural phenomenon that occurs in the summer months north of the arctic circle. it means that the sun remains visible at nighttime. locations south of the arctic circle experience midnight twilight, which means daytime activities are still possible without artificial light during nighttime. this is also known as midnight light or white nights.

What to bring

sunglasses may be handy when driving a car at night since you may be blinded by the sun being low in the sky.

Summer solstice

also means that the sun reaches its highest position in the sky during day. this occurs approximately on:

JUNE

21

mostly unknown. However, researchers have discovered a new type of light-sensitive cells in the retina of our eyes, called melanopsin. This photoreceptor is thought to relay information about light to non-visual centres in the brain through direct pathways.

hypothalamus is part of the limbic system, a system of the brain that is involved in the regulation of a variety of fundamental and essential functions of the body. The hypothalamus as such is a small almond-sized structure involved in functions such as thermoregulation, blood pressure, heart rate, arousal, energy balance, memory, and sleep.

The suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) is a small region in the hypothalamus, responsible for controlling circadian rhythms, which is an oscillating biological process that helps us establish a sleep pattern – our master clock.

The retina of our eye consists of rods and cones responsible for vision, but the retina also contains photoreceptor cells that project directly to the SCN in the hypothalamus, thus providing information about light and dark.

Through different pathways, the SCN controls the release of various hormones such as somatostatin, oxytocin, and melatonin from structures as the hypophysis and the pineal gland as a response to the incoming information from the eye as well as the interpretation and expression of specific clock genes in the SCN.

When the sun goes down, melatonin (and other hormones) is released as a signal that it is time to head to bed. But what if the sun doesn’t go down?

researchers at the University of Tromsö has found that some Arctic animals such as the reindeer show circadian rhythms only in the parts of the

24 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE NATURE

1. from mid march the north end of the axial of the earth tilts increasingly towards the sun, reaching a maximum 23° tilt at solstice.

2. at this angle everything above the arctic circle at 66°n is exposed to the sun 24 hours a day.

3. when the axial of the earth tilts the other direction during winter everything above the polar circle is hidden from the sun.

arctic circle

23° the sun

Ideal

conditions

to give you the best oppurtunity to enjoy the midnight sun, check the weather forecast for a clear night and go to an open area.

on the north pole, the sun only rises once a year at the end of march and stays up until sunset at the end of september. this phenomenon is also referred to as polar day.

year that have variations in brightness between night and day. The researchers could see seasonal changes in foraging, metabolic activity, and power of diel and circadian rhythmicity; effects that could be viewed as adaptations to the extreme living conditions in the high Arctic. Reindeer even change the function of the eye between summer and winter. In summer the reflective surface behind the retina gets golden, something that mammals active at night usually have. In winter, the same part of the eye will get deep blue, to better deal with the lack of light. With these winter eyes reindeer are able to see into the ultraviolet spectrum. However, this is not the case for humans. So even for the inhabitants of Swedish Lapland and the other Arctic regions, sleep deprivation could be a problem. How could we cope with the midnight sun and what can we do to maximise our beauty rest?

it’s quite easy actually. We need to reduce the light reaching our eyes. That could be done wearing sunglasses during the most intense daylight. And in the night use thick curtains in your bedroom – it should be as dark as possible so the photoreceptors in your eyes signals to the suprachiasmatic nuclei, which in turn tells the pineal gland to release melatonin, making us sleepy. Easy, right?

A good tip could be to bring a sleep mask, but to be honest – who travels to Swedish Lapland to sleep through those fabulous lukewarm and bright nights? The best recommendation is for you to stay up all through the night. Just get out and experience all the wonders Swedish Lapland has to offer. This place is for adventures and thrill. But to sit down and relax, grasp the beams from the sun that never sets behind the horizon, is nothing but pure magic.

25 NATURE 23 –24/5 – 18 –19/7 27–28/5 – 14 –15/7 31/5 –1/6 – 10 –11/7 4–5/6 – 6–7/7 8–9/6 – 2–3/7 12–13/6 – 28 –29/6

SORSEL EA RV IDSJAU R

ARJEP LO G SKELLEFTEÅ

PITEÅ JOKKMOKK ARCTIC CIRCLE

LU LEÅ PA JA LA GÄ LLI VA RE

KALI X ÖV ERTO RNEÅ ÖV ERKALIX KIRUNA HA PA R ANDA BODEN ÄLVS

BY N

Where and when to see the midnight sun

the map shows which dates the phenomenon is visible. the further up north you go, the longer the period of the midnights sun gets.

Quirky fact

26 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE PEOPLE

All about ÁRBEDIEHTU

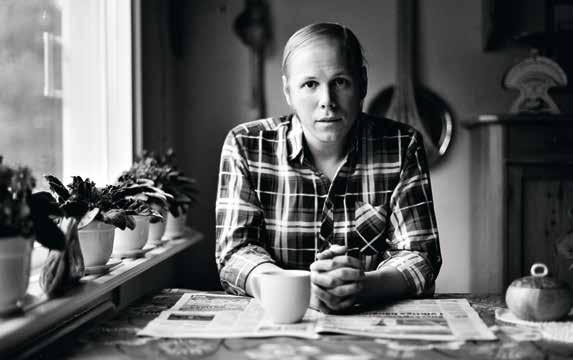

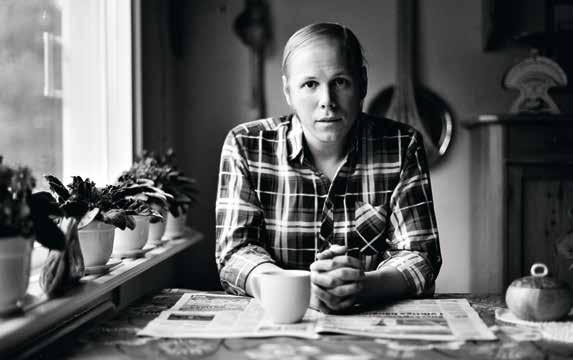

Simply put, painter and craft artist Leila Nutti is a jack of all trades. But what she does is perhaps more aptly described by the Sámi word árbediehtu.

when leila turned 18 her father registered a company in her name. That’s just how things are in the Nutti family.

“While I was I growing up I noticed that people were always working. For me, work is a natural, everyday part of life. Just doing. When you sit around the fire and tell stories or, nowadays, when you’re watching Netflix, your hands are always busy. I think there is some kind of mindfulness in allowing your hands to be occupied with art craftwork.”

Leila always saw her mother and grandmother busy with duodji, Sámi craftwork. They were making pewterembroidered leather bracelets and handbags that would be sold at markets. And she had seen her father fixing something that was broken or crafting something new, or deliberating with her mother about what must be done with the reindeer. Always the reindeer. Although so much else can be said about the Sámi culture and way of life, reindeer are never far from discussion.

When we decided to meet for this interview I suggested a date. Leila replied that it would probably work

leila nutti: reindeer herder, artist, author and more

With her roots in the Sámi culture, Leila Nutti’s passion for root weaving and colorful painting creates traditional artifacts as well as cool prints.

for her, provided it wasn’t during the season when the reindeer must be separated from the herd.

not only a reindeer owner and painter, she is also a craft artist and has written a book about reindeer herding with dogs. This, in turn, has attracted tourists, who come to learn about the latter. In addition, Leila co-manages a project to promote Arctic design throughout the world. When we meet at the Ájtte Museum in Jokkmokk, it is snowing heavily and she has just returned from New York. As part of the project, together with several other designers from Norrbotten and Västerbotten, she has attended a seminar and an exhibition of the group’s work.

“It’s an incredibly exciting project to work with. With us in New York were Care of Gerd, a producer of skincare products, Hikki, who makes supercool outdoor bathtubs, and the Sámi glass artist Monica L. Edmondson. There is such an incredible range in a project like this, as well as in our designs. And it’s not just Sámi things, but more about what the northernmost part of Sweden

27

PEOPLE

TEXT: HÅKAN STENLUND | PHOTO: CARL-JOHAN UTSI

Duodji are handicraft items made by Sámi artisans. The items have their own artistic expression and background in Sámi traditions and way of life. Duodji often has a practical function. The materials used are normally what can be found in nature or provided by the reindeer. Duodji is an important part of Sámi culture.

has to offer. The intention is that about 50 companies from the north will have the chance to attend these shows throughout the world. First up was a visit to Copenhagen, and then New York. The next one will be in Paris, followed by Toronto, and then Tokyo.”

the difference between Tokyo and Eanonjálmme, where Leila’s reindeer graze during the summer in Sweden’s largest Sámi village, Sirges, couldn’t be more striking.

“I couldn’t agree more. Tokyo is an entirely different world. And new technology has made the world a completely different place.”

Leila Nutti, born in 1991, is somehow at home in a time that no longer exists. When she concluded here studies at the Sámi college, Samij Åhpadusguovdásj, in Jokkmokk, she made an item in woven root, sewed a coat from the pelt of a reindeer calf and fashioned a gietka, or crib. At the same time she has all the social media she needs to be present in the digital marketplace.

“That’s so strange. If I could choose, I wouldn’t live in the digital world at

all. But that’s impossible, since I run a company, and that’s just how things are. The implication is that I sometimes know more about what’s happening in American politics than I do about what is really important to me. Will it be good conditions and grazing during winter for my reindeer, or not?”

Everyone in her family works with reindeer. Her parents are still active. Her older sister has scaled down a bit since starting a family, so her younger brother is now the one who is most often out freezing on a snowmobile. That’s family life among the Sámi; everyone helps out when and however they can.

“During certain periods reindeer are the only concern. When it’s time to work with the herd, you can’t simply say, ‘Sorry, I have a meeting.’ It would be irresponsible to book a meeting at the wrong time.”

leila sees herself as more of a painter than a craft artist. The artistic streak is part of her family heritage. Lars J:son Nutti was her father’s uncle. As we wander through Ájtte we pause to admire a gigantic work by the famous artist.

28 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

Leila’s work is inspired by the Sámi lifestyle and the environment that surrounds her.

Photos: Håkan Stenlund

DUODJI

PEOPLE

Jokkmokk is the home turf for Leila, but her work with the project Arctic Design of Sweden aims to bring Arctic designers out to the broader market. arcticdesignofsweden.com

At first it looks rather abstract. And, certainly, it is abstract and very colourful, but amid the profusion of colours appear various more or less detailed images. I stand eye-to-eye with a beast that seems to be hiding in the painting.

“It might be some kind of gufihttarat, says Leila, smiling. The Sámi culture has always been very didactic. Parents frighten their children by saying that, if they poke a stick in the fire, their reindeer calves will go blind. Of course, no one wants to blind the calves; we love our animals, but it was really just a way to prevent sparks from flying out and starting a fire in the hut or tent. I sort of miss that these days. Now, we just give the kids a tablet to play with instead, so they don’t play with fire or wander off into the woods.”

Her paintings are inspired by the Sámi lifestyle and the environment that surrounds her. She wishes to represent the natural environment and express the feeling of contentment she experiences when she is in it.

one sámi word that often crops up is árbediehtu – the transfer of traditional

knowledge that the Sámi people carry with them, without it ever actually being taught. It is a sort of collective knowledge that is born within the individual. In Leila’s case it is rather obvious; since she grew up watching people who were always at work and doing crafts, she has inherited it naturally. At the same time, she has a strong will to preserve and pass on certain things that are vanishing, for example, root weaving.

“I had fantastic teachers when I attended the Sámi college, ‘Samernas’, in Jokkmokk. The school has always had great teachers, the kind who really know how to pass on the tradition.”

“There, root weaving was important for me; not because I wanted to make money doing it, but more because it is an important part of Sámi tradition.”

We pause in the new section of Ájtte museum that features duodji to look at a woven root artefact by Ellen Kitok. At first glance it looks like a sun hat and could well function as one, but it is actually a large sort of dish. A masterpiece, it is a wondrous work of art in which birch root has been tightly woven into a magical basket dish. She has rendered

29

Photo: Tor L. Tuorda

Illustration: Leila Nutti

PEOPLE

it with astonishing skill, especially when you know how difficult the root weaving technique is and how many hours of painstaking work it takes.

during our discussion Leila frequently mentions the school, which is often simply referred to as Samernas. Does it have great meaning?

“Well, yes, you could certainly say that. Going to Samernas is a bit like compulsory military service; it isn’t a question of whether you do it or not, it’s a matter of when. In our community there is a before Samernas and an after Samernas.”

Ellen Kitok, mentioned above, has been a teacher at Samernas. A grant honouring Ellen’s mother, Asa Kitok, who taught root weaving, has been awarded annually at the Jokkmokk winter market since 2005. The first to win the grant was wood and antler craftsman Jon Tomas Utsi, who taught at Samernas for many years. Root weaver Fia Kaddik, also a former teacher at Samernas, has also won the grant. The transfer of traditional knowledge and skills is not something to be taken lightly. And it has to be done well.

leila hopes to be able to learn more about root weaving. As a student at Samernas, she discovered that the techniques and forms of expression used by Sámi craft artists in the far north differed from those used by Southern Sámi craftspeople. She wants to know why. But when will she find the time? When it comes to work, she already has at least five irons in the fire.

“I work in a very structured way. I let the seasons dictate what I’m going to do.”

Now, during November and December, all of her time must be devoted to the reindeer. The animals must be

separated from the large communal herd and identified according to their owners, and it is vital that they reach good winter grazing lands. After Christmas and New Year’s she returns to her studio and produces the art she will exhibit at the winter market. Then comes a period during which she welcomes tourists who come to Jokkmokk to work with their herder dogs. In May, during the calving season, she pulls the plug, heads for the high country and lives the simple nomadic life. This is a time when she tries to scale down.

“It can be difficult to reach me in May. That’s when I charge my batteries, when I’m up in the mountains with the reindeer during calving. It’s probably our most wonderful time of the year. It gives me the renewed energy I need for a trip to Paris or Tokyo, or even to just pick up my phone.”

but what do the mountains mean to her, really? Is it the place or the reindeer?

“I can’t really say if it’s the one or the other. The two go hand in hand. Holistic may sound pretentious, but that’s exactly what it is. It’s all one and the same thing and we are part of the ecosystem. For me, personally, the mountains are my happy place. I’d rather go there any day of the week than travel abroad. Up there, you get back to basics, the modern world is placed on hold and you only concern yourself with simple things. Will we catch any fish for lunch? Do we have enough firewood at our camps? There is an overwhelming sense of gratitude for being part of nature, while there is a realisation that it is all so fragile. During the calving season, when the new cycle of life is born, everything is so delicate and vulnerable. Nature can wipe everything out with a snowstorm. The modern society can obliterate it all

30 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

PEOPLE

31

PEOPLE

“It can be difficult to reach me in May. That’s when I charge my batteries, when I’m up in the mountains with the reindeer during calving.”

by opening a new mine. All of this beauty is also threatened. It can be so liberating when the simple, day-to-day tasks become most important. Hauling firewood is quite simply a form of mindfulness.”

naturally, the reindeer is a central feature in Leila’s art. Her watercolours are not full of abstract explosions of colour; instead, they are more minimalistic and free of embellishment. Otherwise, the Sámi visual expression is often characterized by bold colours. This becomes apparent when you see Ájtte’s new exhibition. Hundreds of incredibly beautiful and colourful woven bootlaces are displayed in a cabinet. How is it that indigenous peoples who have lived so close to the earthy, subdued tones of nature can be so taken by these bold colours?

“I really don’t know. But I have noticed that people from other indigenous cultures throughout the world also like bold, bright colours. I also know that the Sámi were very good at bartering. They were clever hunters who could trade pelts

and hides for silver and beautiful fabrics. Then, back in the day, you received the equivalent of a lumberjack’s weekly wage in exchange for a fox fur or wolverine pelt. The hunter held hard currency in his hand.”

Leila tells us that, according to Sámi tradition, a piece of silver jewellery is placed in the crib of a newborn child. Nowadays, young parents hang a silver ring in the child’s baby carriage. Otherwise, the gufihttarat (the underworld people) will exchange the child for one of their own. You might take similar tales with a grain of salt, but here, in ‘normal’ society, many of us still have Luther on our backs. In the Sámi culture the birth of a child was not taken lightly. If you can afford to put a piece of silver jewellery in the crib, at least you can support your family.

When Leila Nutti turned 18 her father registered a company in her name. That’s just how things are in the Nutti family. Cultural heritage in a modern form – contemporary árbediehtu.

32 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

PEOPLE

DESIGNER’S DREAMS

One room looks like a bird’s nest while another resembles a UFO. There is also the hotel with a train depot ruin straight through the kitchen. And the city hotel that cleans the air to the same extent as an entire forest. We travel between excellent accommodations in Swedish Lapland.

33 DESIGN

TEXT & PHOTO: HÅKAN STENLUND

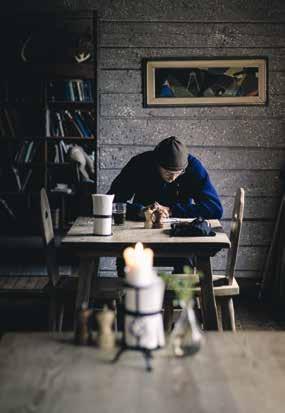

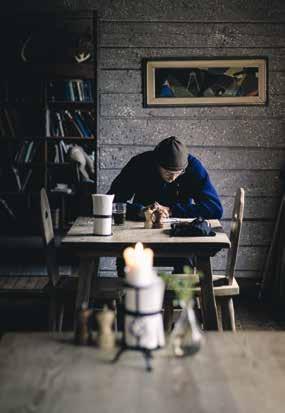

mikael vinka sits at the rough-hewn dining table in the dining room at Geunja, the Sámi eco-lodge he built by hand 20 years ago. He remembers the effort.

“To sum it up, it was damn hard work. That’s probably all it was.”

In those days, eco-things were not in fashion, like they are now. The mountain world where Geunja is located belongs to Sorsele municipality. It became an eco-municipality already back in 1989, one of the first two in Sweden, but even so, saying that it was something of a movement back then would be an exaggeration. Mikael and Anki Vinka’s idea, however, was to build Geunja and make it something extra special. The location was an old residence at Tjulån, in the Ammarnäs mountains. There was a spring on the site: a prerequisite for good water in summer as well as in winter.

Mainly it gave you a feeling of being welcomed on the spot. That’s the most important thing when you look for somewhere to live. That you feel like you want to be there.

Mikael hand-hewed the logs, insulated them with moss and used peat and birch bark as roofing. Everything was done the same way it was when the first nomadic Sámi became settlers, part of the Sámi tradition that is sometimes forgotten.

“You know, even the nails are old handforged nails. If carrying the stone for the fireplace was a struggle, that was probably nothing compared to the frustration of trying to hammer in hand-forged nails. You quickly learn to hit them straight”, Mikael says.

Today, Geunja welcomes twelve guests about twelve times per year. They do everything to make sure the place does not get worn out, and for us to feel welcome.

in riksgränsen, a bit further north in the mountain world, there is Niehku Mountain Villa. A hotel dream as far north and as far away from the rest of Sweden as you can g et, more or less. At a Unesco gala in Paris,

Niehku won the prestigious Prix Versailles for the best hotel interior in the world. Stylt Trampoli, responsible for the interior design and Krook & Tjäder for the exterior design, have succeeded in capturing the uniqueness of the history of Riksgränsen – the Ore Railway – and it breathes new life into the building. The stone wall of the old train depot runs straight through the hotel building and in the restaurant the grease pit for the steam trains of the time has become the perfect wine cellar. Niehku, the Northern Sámi word for dream, is founded by two friends: Strumpan and Jossi, or Patrik Strömsten and Johan Lindblom, names hardly anyone uses. Both of them came to Riksgränsen in the 1990s. Skiing youths with a greater passion for snow than school. The mountain and the distinguished old Riksgränsen Hotel were a haven. They hardly knew back then that it would also become a landmark in their lives. Jossi trained as a mountain guide and Strumpan became one of Sweden’s foremost sommeliers – the perfect combination to run a hotel filled with style-conscious skiers and travellers from all over the world.

design and/or boutique hotels, let us call them lifestyle hotels, is nothing new. They started to emerge already in the 1980s and perhaps Icehotel in Jukkasjärvi could be called the first in Swedish Lapland. In the 2019/2020 season, Icehotel celebrated its 30th anniversary and as always, design and the work of artists have been a priority. If mentioning five key points for a hotel to be referred to as a lifestyle hotel, the first thing to remember is your Shakespeare. “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players”. Icehotel has been offering today’s bucket-list travellers a stage for three decades. That desire to blur the boundaries between outside and inside is something Icehotel always succeeds in.

More than anyone else, it was the Americans Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell who set the criteria for what a lifestyle hotel is. They are the founders of the legendary club Studio

34 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

35 DESIGN

“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.”

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

Photo: Ted Logart

Photo: Asaf Kliger / Icehotel

Photo: Philipp Herfort

Geunja, the Sámi eco-lodge

Icehotel

Niehku Mountain Villa

54 in New York, and the creators of the hotel

The Morgans. According to them, a lifestyle hotel should indeed be a theatre stage with the lobby as its centre. The hotel should reflect the lifestyle of its guests and blur the boundaries between outside and inside. Preferably, the hotel itself should be the main reason why someone would visit the location at all. The hotel should be a destination in itself.

in the lobby of kust hotel and spa in Piteå there is an old, dry pine tree. The combined restaurant and rooftop bar at the hotel is called Tage. Both things are attributable to Tage Skoog, the man behind the Skoog Group who owns the hotel. Tage found the tree when the lobby was almost finished. He called his daughter Christina and said he had “found a twig” and that he thought it would look good in the lobby. Since it was her dad calling her, the tree ended up in the lobby, of course. They actually had to rebuild the entire entrance of the hotel to accommodate the tree. Remember what you read earlier: in a boutique hotel, the

36 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

Photo: Jens Wennerberg

Photo: Viggo Lundberg

KUST Hotel & Spa

Arctic Bath

DESIGN

Bertil Harström in front of UFO, one of the tree houses he designed for Treehotel.

lobby is the centre. In the lobby bar, that could also be called the gin bar, I have a gin and tonic this afternoon while I wait for Christina Skoog, who is going to answer some of the questions I have.

“Tell me about the façade, how is it unique and how does it work?”

“It is a concrete façade made with a mixture of titanium oxide, which means that the entire façade absorbs carbon dioxide and works as a lung”, Christina says, and continues:

“But besides getting rid of carbon dioxide – and those results are completely measurable –the titanium oxide helps keep the façade clean.”

Because of this façade, Hotel KUST in Piteå won the Environment Prize of the year, awarded by the construction industry. And because of its interior, the hotel KUST, one of the main reasons for visiting Piteå, was named Northern Europe’s best new hotel and Northern Europe’s best boutique hotel by the World Luxury Hotel Awards.

bertil harström, fly fisherman and architect, has already turned 70. This afternoon he takes a stroll outside Arctic Bath, a new cold bath house on the Lule River outside Harads. The concept was born almost ten years ago, at the after-party of the inauguration of the newly opened Treehotel. Someone patted Bertil on his shoulder and said: “Now you have to design a sauna raft for the river, so people staying at the hotel have something to do”.

“So, this is basically an after-party that went overboard”, he says and laughs.

“At the time I didn’t really think a sauna raft would be my next project and I didn’t do anything about it. Ten years passed, but that’s when the idea about the river got firmly lodged in my head.”

The ‘sauna raft’ became a 700 square-metre cold bath house and hotel named Arctic Bath, where shape and design are inspired by old-fashioned log jams on the river. The resulting creation is Sweden’s perhaps coolest hotel project.

by now, most of you are familiar with the story about Treehotel. About a group of architects on a fishing trip with Kent Lindvall, and how they started talking about the film ‘The Tree Lover’ by Jonas Selberg Augustsén around the campfire one evening. The film had just been shown on Swedish television and brought to life a childhood dream of building tree houses. The project around Treehotel brings together some of the most recognised architects and designers in Sweden and Scandinavia. Tomas Sandell, Tham&Videgård, Cyrén&Cyrén, Sami Rintala, Snøhetta and Bertil Harström – they have all built a tree house each, now rented out as hotel rooms. Bertil is the only one who has two tree houses at Treehotel. One looks like the most common house in a forest: a bird’s nest. The other one is its opposite, the most unexpected thing you could come across in a forest: a UFO. Bertil has also designed the public facilities at Treehotel, such as sauna, relax and spa. He has an unfaltering love of wood.

“Yes, damn it. I don’t think there’s anything sadder than the image of trucks driving timber down to the coast.”

“Beautiful trees exported at the going dollar exchange rate. It’s so unimaginative.”

for more than 30 years Bertil Harström has been fighting for people’s right to build wooden houses. His love of tree houses and log jams sits deep inside his soul. He is an architect and designer, but deep down he is more of an idealist and tree hugger. These projects are not just an architect’s vision and dreams,

37 DESIGN

“Arctic Bath is basically an after -party that went overboard.”

they are based on a belief that in Sweden we actually miss something when we do not allow ourselves to build more using wood.

“Wood is a brilliant building material. It absorbs moisture, binds carbon dioxide, transports heat, but still every Swede has to enclose his house in plastic to get building permits or a mortgage. It’s sick.”

These days Bertil sits at home in his old log house in Sundsvall, working. He used to run Inredningsgruppen, the largest agency of interior designers in the north of Sweden. But it got too much and he got worn out. He had to start over and do things differently. The house outside Sundsvall became a refuge.

“You know, internet, that was the rescue. I’m as connected outside Sundsvall as in New York. It really is possible to live and work in the countryside. Perhaps that’s why I am running these projects. To put the countryside in focus.”

Bertil is the designer of Arctic Bath and the idea of a cold bath house in the shape of a log jam was born a long time ago. Together with Johan Kauppi from Tornedalen he was able to create a new design hotel in Harads that has become a world attraction.

there are many design favourites in Swedish Lapland, and one of them is actually located in Tornedalen. Arthotel in Risudden is a kind of Swedish Sextantio, albergo diffuso. You know the story of Daniele Kihlgren, of Swedish descent, who came to an abandoned mountain village in Italian Abruzzo and decided to rebuild the entire mountain village Santo Stefano di Sessanio into a designer hotel. Gunhild Stensmyr came to Risudden in Tornedalen on a summer’s day. She was born in a neighbouring village, but like so many others she and the rest of Sweden packed up and moved to the city in the 1960s. Gunhild worked at various museums and art galleries before eventually working her way down to Skåne, where she got homesick and went back up to Tornedalen. The Tolonen house in Risudden was empty. She bought it, then she bought the Wennberg house, and then three more houses. She has now renovated them all, with first-class design, and packaged them as a hotel experience that is both a visit to someone’s home and exclusive, spoiled luxury.

“I’m not sure if luxury is the word for it, anyway this isn’t that kind of hotel. But I suppose it’s a kind of luxury to stay in a place where the hotel owner knows everyone, from the artists whose work is featured on the walls to the fisherman who provides you with Kalix löjrom”, says Gunhild.

“The advantage of Arthotel is the simple luxury of being completely surrounded by art and design, and at the same time bringing all of Tornedalen’s history and beauty across the threshold of the house.”

“The experience shouldn’t end just because you enter the house, it should be reinforced. That’s why art exists.”

38 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE

more: samiecolodge.com niehku.com icehotel.com hotellkust.com arcticbath.se treehotel.se/en/ arthoteltornedalen.se

Read

DESIGN

Arthotel Tornedalen

CITY DWELLINGS

sara

A building called Sara is built in the middle of Skellefteå. It is one of the tallest wooden houses in the world – a role model for sustainable design and construction. It will host the town’s cultural life as well as an excellent hotel. Sara is named after author Sara Lidman. The Wood Hotel is run by Elite Hotels.

Architect: White Arkitekter

shopping

When Luleå’s shopping centre ‘Shopping’ was inaugurated on October 27, 1955, it was actually the world’s first modern mall: a meeting place in an Arctic context. It lacks distinct floor plans and the unconventional space creates an almost labyrinthine interior.

Architect: Ralph Erskine

kristallen

Due to Kiruna’s city transformation a brand new city hall has been built. The so-called ‘living room of Kiruna’ is named Kristallen (the Crystal) and houses the city council as well as the Regional Art Museum.

Architect: Henning Larsen

Architects

kunskapshuset (the Knowledge House) in Gällivare won the Swedish Design Awards. What happens when an entire town – Malmberget in this case – disappears? Where do all the memories and the knowledge go? Kunskapshuset is also a school, and it unites Sámi and industrial history in a magical building.

Architects: a collaboration between Liljewall Arkitekter and MAF Arkitekter.

39 DESIGN

Naturally, there are buildings with exciting design and architecture in Swedish Lapland that are not only related to the hospitality industry, but also part of the cityscape itself.

Sara Shopping

Kristallen Kunskapshuset

Photo: Håkan Stenlund

Photo: Anders Bobert

Illustration: White Arkitekter

Photo: Sune Sundahl/ArkDes

AND THE GOOD OLD ONES

1. Akerlund

Åkerlunds Hotel in Jokkmokk has been a classic hotel ever since the beginning of the 20th century. Renovated, modernised and renewed since then, of course. The Åkerlund family ran the hotel for several generations, but it has been run by others with roots in Jokkmokk for a few years now. The little hotel feels both cosy and traditional. Right next to the hotel is another classic Jokkmokk venue: the hundred-year-old cultural scene Bio Norden. Films and entertainment have been provided here since almost before the place existed. Bio Norden can be rented for conferences. hotelakerlund.se

2. Haparanda Stadshotell

The oldest city hotel in the destination Swedish Lapland is Haparanda Stadshotell, inaugurated back in December 1900. It was designed by architects Fritz Ullrich and Eduard Hallquisth, who also designed Haga Courthouse in Solna and the Eurydice district in the Old Town, both in Stockholm. At the turn of the century, Haparanda was where East met West, a meeting place between the Tsarist Empire and Europe. In April 1917 the Russian newspaper Novoje Vremja wrote that out of Haparanda’s 1,500 inhabitants, almost 250 people were estimated to be agents or spies. This is where the great powers held court; among crystal chandeliers, plush furniture and stucco work they thrived in the lounges at Haparanda Stadshotell. Nowadays the hotel has been meticulously and uncompromisingly renovated to once again provide an exciting setting for world travellers. haparandastadshotell.se

3. Pite havsbad

In 1944 Elof Söderberg from Jävre bought four hectares sandy beach on Piteholmen outside Piteå. There was a world war raging in the outside world. Land was cheap and a sandy beach was of little value. Elof was an electrician and entrepreneur, and he quickly set up some cabins for rent and opened a kiosk selling ice-cream. Piteå was the warmest place in Sweden for three years in a row in the early 1950s, and the public took to calling his place ‘the Northern Riviera’. People flocked and there was plenty of sunshine for Elof to make his hay. Today, Pite Havsbad is one of Swedish Lapland’s strongest brands: a full-scale seaside complex that has developed far beyond that icecream kiosk Elof Söderberg once set up. pitehavsbad.se

4. Luleå Stadshotell

In the beginning, this building was a combination of hotel and town hall. It was designed by architects Fredrik Olaus Lindström and Karl August Smith, and constructed in 1903. Smith went on to become Luleå’s city architect while Lindström became a city architect in Umeå, where he helped with the drawings after the great fire of 1888. Luleå Stadshotell now belongs to the Elite hotel chain and suffered a severe fire itself in 1959, which completely destroyed the hotel’s top floors. These days its decoration is slightly more modest. But there is still something wonderfully classic about its rooms, not least of all the stucco work in the festival hall, which is actually where breakfast is served. elite.se

5. ÅrreNjarka

The Mannberg family has operated a mountain farm in the village Årrenjarka since the beginning of the 19th century. The name means ‘Cape Squirrel’, indicating that the family earned some income through hunting – furs were hard currency – and agriculture was a way of getting some extra food. So perhaps it was not such a big step to start keeping a meticulously organised mountain farm – including their own, very tasty, potato variety – to house visitors on their way to Sarek and the Unesco World Heritage Site Laponia. The almond potatoes you can taste in the Njarka restaurant, where game and typical flavours from the area play the main role on the menu. This is a place filled with relics and stories from a time long before what we call modern, a story about a slowly changing cultural climate. arrenjarka.se

6. Saltoluokta

On the other side of lake Langas, at the outskirts of Sarek and Stora Sjöfallet, right in the middle of the King’s Trail, you will find the STF facility Saltoluokta. The timbered main building was erected as early as 1918, and has well-preserved fireplaces and plenty of charm. In winter you get here by following a prepared 3.5-km trail; in summer you take the boat, M/S Langas, across the lake (it follows the bus times). At Saltoluokta you have accommodation and activities conveniently located in the middle of the large, Unesco-designated World Heritage Site: Laponia. An area of outstanding universal value to humanity in terms of both culture and nature. svenskaturistforeningen.se

40 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE DESIGN

They are the old -time favourites we often go to. Like friends we learned to know years ago, whos company we still enjoy and seek out. They are the good old ones.

1 3 5

2 4 6

41 DESIGN

Photo: Håkan Stenlund

Photo: Håkan Stenlund

Photo: Håkan Stenlund

Photo: Linda Broström

Photo: Ted Logart

Photo: Ted Logart

THE MOVEABLE FEAST

Eating well is part of every journey. And on a road trip through Swedish Lapland you have every chance in the world to enjoy a moveable feast.

down at the shore of Alep Miekak stands chef Johan Eriksson, filleting a fish he has just caught. Planning to serve it as a starter for tomorrow’s dinner, Johann cures the fish quickly. Fresh fish straight from the lake, just the right amount of salt and sugar and it goes in the fridge. On the face of it, that doesn’t sound so remarkable. Even so, that’s about as simple and good as food can ever be. That’s pretty much what it was all about when the Nordic noir food trend went international. Fresh ingredients prepared and preserved according to ancient methods that were practised by the original inhabitants of the region. Smoked, salted, pickled or dried and, most of all, fresh and right on site. If the new Swedish cuisine wants to call itself progressive, Swedish Lapland can rightfully claim that it has been progressive for 6,000 years or more. We have never known anything else. A pot of water

is boiling over the fire, ready to poach another fish. Culinary art is second nature, even when Johan is up in the mountains.

restaurant oaxen, in Stockholm, with head chef Johan Eriksson from Piteå at the helm, was awarded its second Michelin star in 2015. The champagne corks hit the ceiling for an evening, and then it is time once again for low-and-slow cooking and simmering stock pots. Johan was head chef when Oaxen won its first star, and then its second. A colleague says jokingly that they will soon be on their way to the Holy Grail for fine dining establishments – a third Michelin star which had until then eluded Swedish eateries. Johan squirms a bit. He’s a little tired of that whole scene. He’s nearly going mad; he never has time to go fishing.

42 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE TASTE

TEXT & PHOTO: HÅKAN STENLUND

43 TASTE

Photo: Carl-Johan Utsi

we fast-forward the story a few years. Johan Eriksson grills a nicely aged entrecôte at the new bistro, Centrum Krog, which he has opened on the town square in Piteå. Between Oaxen and Centrum Krog he also did a stint at Hotell Kust, as well as baking some of northern Sweden’s best pizzas in the wood-fired oven at Kiosken pizza och vin. The Michelin star chef as a pizza baker. Laughing, he serves the rib eye to a regular guest and they chat for a while about this and that. It is just after eight on a Saturday night, this was the last order and the kitchen is about to close. Packed and ready, with a couple of fishing rods on top of his gear, Johan’s car is waiting outside. He’ll soon be on his way to the river.

The pizzeria is probably the final outpost of democracy. Without the local pizzeria, many communities in Sweden would have no restaurant at all. The taste of a Vesuvio pizza in Swedish Lapland barely differs from one in the south of Sweden. However, it goes without saying that Johan Eriksson’s pizzas are not of the run-of-the-mill reformed ham variety. The talent for good cooking never leaves someone who has led a two-starred Michelin kitchen. And the fact is, loving food and drink is getting easier, even in what is now known as Sweden’s Arctic destination, Swedish Lapland, over the past decade. Microbreweries and White Guide restaurants can now be found nearly everywhere.

but what does it take to be Sweden’s best sommelier? One way to do it is to quit high school, take a job in a ski-resort restaurant and ski your buns off while devouring as much wine knowledge as you can. Then, if you’re an autodidact, you might just have a chance

to be the first (and thus far only) wine aficionado to be twice winner of the Sommelier of the Year Award in Sweden. For Patrik Strömsten, “Strumpan” to most who know him, that was the perfect career path. And, along the way, a hotel came into the equation. Together with Johan “Jossi” Lindblom, Strumpan was part of the team behind the concept for Niehku Mountain Villa in Riksgränsen. From the kitchen, head chef Ragnar Martinsson serves up world-class food every day and the wine cellar is truly impressive. Although Strumpan has moved on, Riksgränsen, the place where his love of wine grew and flourished, will still be a part of his life. Naturally, Niehku remains; after all, what would you expect of a hotel that grew out of a railway ruin from another century? Under a glass floor in the middle of the restaurant, in what was once a grease-pit for steam locomotives, is a wine cellar. Sara Johansson is Niehku’s new sommelier. She has solid experience from having worked with Niklas Ekstedt, but also from her own project, Einer, in Oslo. In the wine cellar, she pauses in front of several cases of Phenomena, a Brunello di Montalcino Riserva by Giugi Sesti, but instead selects a Pinot Noir, from Domain de la Côte in Santa Rita Hills, in California.

vintner’s sasha moorman and Rajat Parr create magical wines. What started as a sort of garage project has become a world-class sensation. The organic philosophy has been replaced by all-out biodynamic wine growing. Nothing is added and nothing is taken away. What you get is the wines’ own character, from its own place, its unique terroir. And, in some way, this is

44 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE TASTE

“But what does it take to be Sweden’s best sommelier? One way is to quit high school, take a job in a ski-resort and ski your buns off while devouring as much wine knowledge as you can.”

45 TASTE

Jossi Lindblom

Sara Johansson

Johan Eriksson

The Niehku dining room.

The kitchen team at Niehku getting ready for service.

Photo: Mattias Fredriksson

synonymous with how good food and wine should be produced. You start with something that interests you deeply and turn into something phenomenal, whether it has to do with a keen interest in wine, a sense of how one’s own beer should be brewed or how quickly a fish should be cured.

a couple of days after meeting Sara Johansson at Riksgränsen, I enjoy a ten-course tasting menu at Bryggargatan in Skellefteå. It is a gastronomic experience conjured up by Icelandic chefs Jon Oskar Arnason and Runar Larsen. Delightful. Always good, in fact. Excellent fish with a hint of liquorice usually appears on the menu, a passion they brought with them from the island in the Atlantic. Before the two Icelanders came to Skellefteå the town was well known for its hockey team, but scarcely for its food. On a dismal square, people might have been heard

arguing over who made the best kebab. Back then, the speciality wasn’t exactly sirloin of reindeer and deepfried gnocchi.

“No, the food culture didn’t bring me to Skellefteå. But Bryggargatan promised great possibility,” says Runar. “And the town is surrounded by nature. I pick wild mushrooms and berries and I hunt. I try to get out as often as I can. Perhaps it’s that, more than the actual restaurant, that makes me love this place,” adds Jon Oskar.

The evening’s ten-course menu is rounded off with a dessert complemented by a savoury piece of Svedjan cheese, a favourite from the village Stor-Kågeträsk. Here, we have to be honest. Over the past decade attitudes to food have changed, even here in the North. We are in the middle of Ostriket (The cheese country) and we have always had our fantastic Västerbotten cheese. That a couple like Johanna and Pär Hällström

46 THE ARCTIC LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE TASTE

“Someone has to depart from convention and lead the way. As always.”

Jon Oskar Arnason and Runar Larsen

Photo: Sven Burman

at Svedjan Ost would suddenly appear on the scene and be asked to make cheeses for the Nobel banquet was unexpected but very cool. Someone has to depart from convention and lead the way. As always.

in stor-kågeträsk the cows are still out to pasture. But their freedom to graze all summer long and well into the mild autumn will soon end when the days grow short and the northern winter comes.

“Quite simply, healthy animals produce the best food,” says Pär, looking out over the meadow down near the lake.

“We started making cheese because we wanted our cows to have a good life. We wanted to preserve a living landscape and keep animals that are healthy and content, but it was hard to make a living by just producing milk. So, one day we decided to try making cheese instead. But there’s not much money in making

cheese either. Timewise, it’s a long-term investment.”

Svedjans Gårdsost, a grainy hard cheese for which Svedjan has won numerous awards, must be aged for at least a year before it is “just right”. And when you are new to making cheese, how can you know what “just right” is? Pär now has a pretty good idea of what constitutes a good cheese. It has to be just how he likes it. When he and Johanna began their dairy transition, he had only one thought in mind – but he couldn’t be entirely sure until he had reached his goal.