TABLE TENNIS HISTORY

September 2025

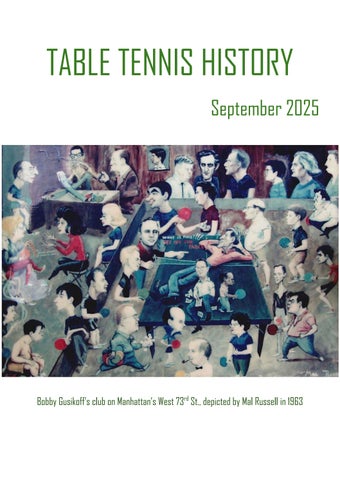

Bobby Gusikoff’s club on Manhattan’s West 73rd St., depicted by Mal Russell in 1963

Bobby Gusikoff’s club on Manhattan’s West 73rd St., depicted by Mal Russell in 1963

Each of the first six issues had a world champion on the cover. This time ... three world champions, all Americans, along with a number of other U.S. national champs. This New York City club boasted one of the all-time strongest member lists. We tell you about its 1963 cast of characters and then add separate articles on The Funny Guy, The Artist and more.

When the reigning world champion, just 23 years old, shatters his playing arm, you can only hope for the best. In this issue, for the first time anywhere in public print, Victor Barna tells us the true before, during and after of his pivotal 1935 auto accident. Our talented new illustrator Art Intelli portrays the unsettling crash scene. His rendering is not meant to be sensationalist, but rather to hit home with just how serious this truly was and how much worse the outcome could have been.

The new Marty Reisman movie trailer is out: Marty Supreme. USA release date is December 25.

Your articles, ideas and comments are welcome. You can reach us through our TT History website. Swaythling Club International makes past issues available on its Publications page.

Steve Grant

Every table tennis club has its own unique cast of characters. The cast of Gusikoff’s, the 1960s New York City club, was frozen, immortalized, in this 1963 painting. The artist, No. 25 Mal Russell, sits on the table with paper and pen. He was NYTTA president 12 years earlier.

What’s unusual about THIS cast is its high concentration of champions. This was a heck of a club, the most talent-packed in U.S. history. Jibes and joking set the mood, but this was the home of serious matches with stakes on the line. Let’s start with the three former world champions:

30. Sol Schiff, 1938 world doubles champion (with Jimmy McClure) and 1937 world team champion. Sol used this caricature, with some additions, for his equipment business logo, left.

31. Dick Miles, 1949 world mixed doubles champion (with Thelma Thall). He also won a world silver and four bronzes.

15. Leah Neuberger (Thelma Thall’s sister), 1956 world mixed doubles champion (with Erwin Klein) and at one time ranked World #3. Known as Miss Ping, she won five world bronzes, too. The words next to her say, “Ping Stamps (A Penny a Point).” A 1960s club habitué, Arthur Nieves, recently explained this for us: “Ping stamps never physically existed, but they were often referred to by Leah. ("Want to buy some Ping stamps?") They stem from the fact that Leah would play every jabloney in the place for a penny a point. Those were her stakes, always, and she wasn't gambling. "Penny a Point!" I lost many pennies to her. The highlight of my table tennis career was the day she said "Let's just practice," because it meant that she no longer thought she was a lock.”

The other two members of the 1956 women’s team (4-3 record, 4th place) were also future Gusikoff’s members. (Gusikoff opened the club in 1960.)

17. Pauline Robinson Somael 33. Lona Flam Rubenstein

The 1955 U.S. World Men’s Team (5th-8th place of 32 teams, captained by 5. George Schein) were all future Gusikoffers, too. They were Dick Miles plus: 2. Bobby Gusikoff 11. Bernie Bukiet 34. John Somael 18. Harry Hirschkowitz

USATT historian Tim Boggan on Bobby Gusikoff: “Back in his corner of the world, the center of all about him, half astraddle his desk, was the long-legged Goose interrupting one of his hundreds of stories, ‘Tell me, who knows more about this (expletive) game than I do?’”

Six of the above won a U.S. national singles championship, namely Schiff (1934), Miles (ten times), Neuberger (nine times), Bukiet (1957, 1963, 1966), Gusikoff (1959) and Somael (1944). And 28. Bernice Charney Chotras (right) was the 1946 and 1963 singles champ. So club members accounted for 27 U.S. singles titles in all, of which 25 were in 1944-1963. Put differently, of the 40 titles awarded in those 20 years, 19 were won by Miles and Neuberger and six by other Gusikoffers.

After winning the 1962 junior championship, 20. Danny Pecora (left) of Wisconsin moved east for the competition at Gusikoff’s and environs and made the 1965 U.S. World team. (But this drawing could instead be Bobby Fields, the 1961 national doubles champion with Bukiet.)

12. Jerry Kruskie (right) had moved east from Michigan and was another member of the 1965 U.S. team, as well as 1966 U.S. doubles titlist with Dell Sweeris. Kruskie was also a tournament golfer and tennis player.

27. Dean Johnson (left) is today in the USATT Hall of Fame for his various contributions to the sport. To learn more about the 11 Hall-of-Fame Gusikoffians, see the profiles by Boggan at HOF

Tim “No-Look” Boggan (right, 1953, a future Hall-of-Famer himself) was another club member but not until 1965, two years after the painting. He wrote, “Some of the happiest moments of my late 30’s and early 40’s life would be spent at this Club. Well I remember how, after I’d finished teaching my afternoon classes, I’d hurry away from school and, on coming up out of that Manhattan subway, would literally run the two blocks that remained, then dart down those Hotel-basement steps. It was also in this dark, subterranean world that my two sons began to learn not only about table tennis but about people in all their life-giving, life-loving variety.”

When it opened, the club called itself “A Place Where You Can Bring Family and Friends.” Like all New York clubs in those early decades, Gusikoff’s quickly became a gambling den. Boggan tells a story he heard: Marty Reisman was out of practice and so visited the club (even though he owned his own club) to prepare for the 1962 U.S. Open. But the club stars would play him only for money. He lost heavily at the beginning yet (if the story is true) finished ahead for the night. Gambling was always in the air. By the way, the aforementioned 31. Lona Flam Rubenstein, a philosophy teacher, became a tournament poker player 40 years later (left).

Other identifications: 1. Irv Wasserman won the 1962 Pennsylvania Open with surprise wins over Gusikoff and Miles. 3. Morty Albert, at times Schiff’s doubles partner. 4. Doon Wong. 6. Howie Ornstein, a top-40 U.S. player who captained the 1962 U.S. team vs. Canada. 7. ?. 8. Barry Michelman, at times a top-10 U.S. player. 10. ?. 13. Sam Hoffner, who soon moved to Miami to battle Laci Bellak for senior titles.14. Leo

Plastrik. 15a. The head on Leah’s shoulder, overlooked in the numbering, could be her husband Ty, or could be Claire(e) Gordon. 19. ?. 21. Jim Blommer (a guess), Pecora’s doubles partner from back home in Wisconsin. 23. George Chotras. 24. Marty Doss, native of Germany, at times a top-10 U.S. player. 26. Al Ayer. 29. Dr. Andreas Gal, who won the 1957 U.S. over-40 championship with a thick, oversized plain sponge racket, a few months after escaping Hungary. 32. ?.

That glorious building that housed the club, the Riverside Plaza on West 73rd (left), began as a Mason’s club in 1927, went through several phases and is today a residential condo. In the 1940s, the subbasement had a bowling alley that was Babe Ruth’s favorite hangout. In the 1960s, that bottom-most level was a gym with swimming pool. Meanwhile, the building’s fourth-floor ballroom saw 2000-guest weddings, major political meetings, dachshund club competitions, numerous show rehearsals (such as The Crucible with Melvyn Douglas, Colleen Dewhurst, Fritz Weaver and Tuesday Weld) and probably a table tennis tournament or two.

In 1970, Gusikoff, a drummer and singer, moved to Los Angeles to study film, but the club survived several more years

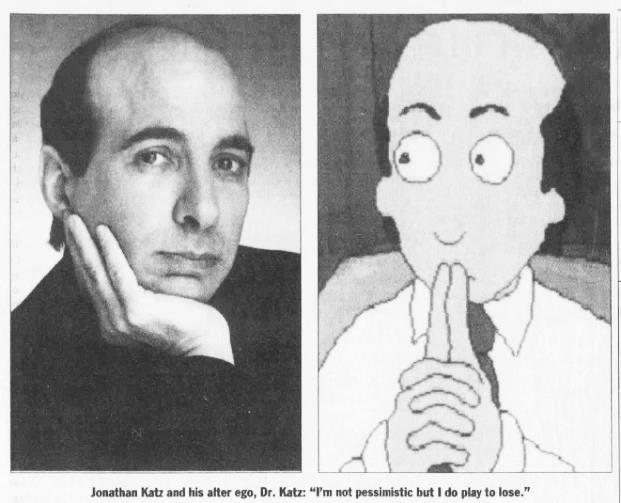

22. Jonathan Katz (left), only 15 years old in the painting, found success in comedy see the article on page 10.

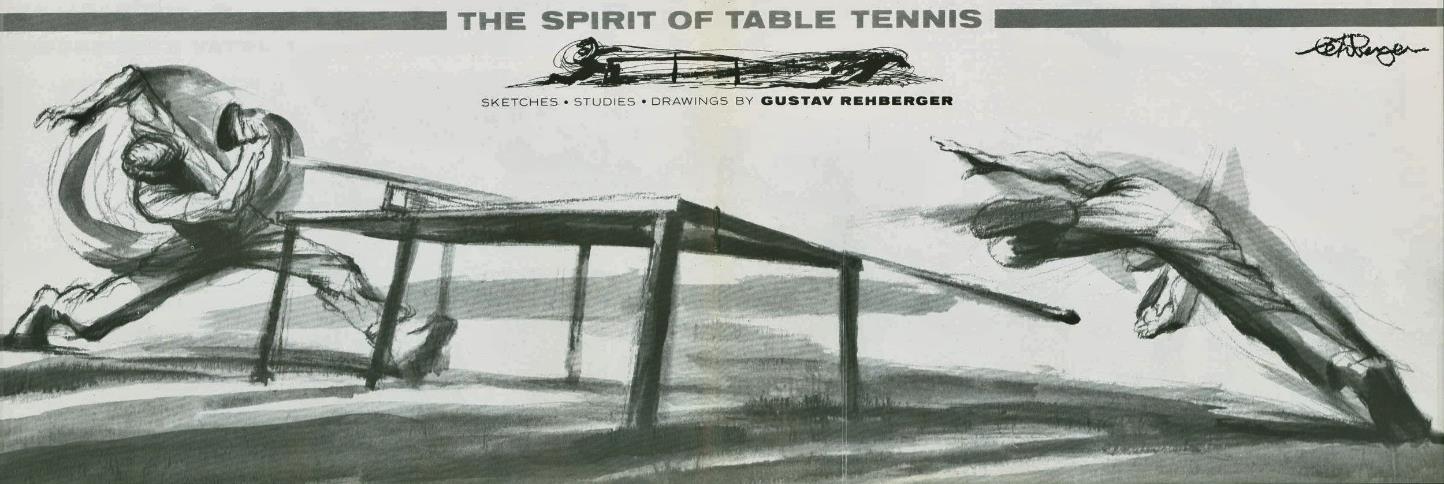

9. Gus Rehberger (right) continued his admirable art career see page 12

We can’t resist showing one more photo of Somael, 18 years before his appearance in the painting. The caption says Cpl. John Somael, the 1944 national singles champion, is teaching other “stars” at the 1945 championships how to grip the paddle. (One is 15-year-old Marty Reisman.) The stars apparently found it amusing.

by Arthur Nieves (USA)

Sol Schiff was the only world champion from the 1930s that I ever had the chance to watch. At times I saw him at Gusikoff’s in New York, but that was not my main club (Reisman’s was), so I saw him mainly at tournaments. Of course this was the 1960s and he was past his prime, but still ...

My most vivid memory of Schiff came at a Long Island Open or Easterns. It was shortly after Dal Joon Lee had arrived in the U.S. Lee was seeded to play Fuarnado Roberts in the Quarters, so Robbie spent the week before the tournament explaining how he was going to beat Dal Joon to anyone who would listen. (I listened, but I have to admit that I didn't follow his strategy.)

Anyhow, comes the day of the tournament, and it turns out that, in the Eighths, Robbie first has to get by tooold and too-slow Sol Schiff. Robbie serves first, short to Sol's backhand and Sol cracks it right off the bounce for an angled cross-court winner. 0-1. And the rest of the match was mostly more of the same. I believe his sponge bat was pips-out. Sol didn't push more than maybe twice a game, and he moved very little. He just planted himself in the middle of the table, took every ball where it came, and hit every shot.... either a consistently hard forehand, or a backhand that seemed even deadlier because it came quick off the bounce with a short stroke and could go hard down either side. It wasn't a complete runaway, but I do remember feeling that Robbie was outclassed and Robbie was a top player who had a legitimate shot at beating anyone in the country (except, of course, Dal Joon Lee). And Sol was, well .... born in 1917 and out of shape. And even though he was easily beaten 3-0 by Dal Joon, he made some awesome shots against him too. Sol must have been quite frightening in 1937!

He was also a nice guy. Everyone knew Sol, and I never heard anyone say a bad word about him. My contact with him was limited, but he was always cheerful, honest, friendly and never caused any trouble. He once umpired my match with Jack Weiner. Sol had lost in his event, and every loser had to umpire one match. He did it pleasantly and professionally and even had some words of encouragement and advice for me when Jack won. If I'd been a former world and national champion, and had just lost a match, I don't think I would have umpired a trivial Class A quarterfinal. But Sol did.

That’s Sol, folks.

The youngest person on our Gusikoff’s cover is Jonathan Katz, 15, later a wellknown comedian. Born in 1947, he lived at 90th and Lexington in New York City and started playing table tennis at the nearby Y as a child. One day, in about 1960, his mother took him across town to Marty Reisman’s club at 96th and Broadway. Katz’s new role model, Reisman himself, would probably say, “Another life I’ve ruined!”

Katz was taken by his dad to various tournaments, and by 1962 he became one of the top juniors in the Northeast. He began playing more at Gusikoff’s. Arthur Nieves, who knew him, tells us in a recent email:

“Jonathan was a nice guy, a good player, and with a smooth defense that was fun to watch. If you weren't very close to being a top player, you couldn't beat him and even the best players had to take him seriously. He was always funny, and I didn't know he was later a comic. When I finally saw an episode of Dr. Katz [his 1990s animated TV series about a psychotherapist], I thought "What's the big deal? He's just 'doing' Jonathan."

Katz studied at Goddard College, an experimental school in Vermont. In his freshman year, he ran this ad several times in the local Times Argus, February 1966:

He performed occasional exhibitions with Reisman or Sol Schiff. He also started a college table tennis club. One member was a fellow theater major, David Mamet (born one day before Katz), who became a famed playwright. Katz and Mamet have remained lifelong friends and collaborators. An early partnership was a table tennis hustle in Chicago, where Katz purposely lost to the inferior Mamet to set up a bet with another player. Katz also occasionally hustled pool, not far from Gusikoff’s, while Mamet was more of a poker player. Fittingly, Katz and Mamet co-wrote the 1987 movie House of Games, about gamblers and con artists. In 1996 Mamet voiced his cartoon self on an episode of the aforementioned Dr. Katz: Professional Therapist.

After college Katz continued playing table tennis off and on, adopting long-pips Phantom in the late 1970s. “I just love the game so much,” he later said. “I was never going to be as good at anything else.” He considered himself a top-20 U.S. player.

His entertainment career gradually took shape. Katz led a rhythm and blues band called “Katz & Jammers” (his other

college major was music), was musical director for Robin Williams’ 1979 tour, and co-wrote an ABC pilot with Mamet. He finally realized that comedy was his forte. Stand-up gigs led to appearances on David Letterman and similar shows.

Then came his Emmy award-winning animation Dr. Katz, six seasons on the Comedy Channel. One episode featured table tennis and contained an inside joke that few viewers comprehended, featuring a five-second voiceless cameo by 1956 world mixed doubles champion Leah Neuberger of the U.S. (left). To appreciate it, you had to know that Leah had died several years earlier (1993). You also had to know that Leah spent more hours at the table tennis club than anyone, even when she was no longer playing much. The episode has Katz visiting a club and saying, “Leah, hi, I thought you died.”

This marked the second time that caricatures of Katz and Leah had appeared together, the first being 35 years earlier in our cover painting.

At another point in the episode, Katz’s son goes into a video store (this is the 1990s), says he needs to rent “Legends of Table Tennis” (an actual video in real life, left, produced by Bobby Gusikoff and now on youtube ) and asks if the store has a table tennis section. “Of course we do,” says the clerk. “We’d be out of business by now if we didn’t have a complete table tennis section. Let me look that up on the computer... Oh gosh, there was a quicker geek, so it’s out. I have Myths of Table Tennis. I have Great Moments of Table Tennis. I have Good Moments of Table Tennis. I have Typical Moments of Table Tennis.” The full episode can be viewed at table tennis.

Katz and alter-ego Dr. Katz: "I'm not pessimistic but I do play to lose."

At one time there was a syndicated Dr. Katz comic strip. An example:

It was the 1960s. Gus was one of the regulars at the New York Table Tennis Courts, better known as Gusikoff’s. He was once a top-25 U.S. player, but that didn’t count for much at this club ... not with its many world and national champs. The owner himself, Bobby Gusikoff, was the 1959 U.S. champion, singles and doubles.

Gus Gustav Rehberger (1910-1995), Austrian-born but an American since 1923, had another talent, though. He was an artist, both commercial and fine art. He drew this marketing piece for Bobby.

This wasn’t the first time he had applied his artistic skills to table tennis. He drew an invitation for his 1942 match with a fellow Chicagoan:

You can watch film of this exhibition at Rehberger, set to the music of his favorite composer. The video also includes scenes from a 1952 exhibition Rehberger did with former U.S. champion Johnny Somael.

Nordhem and Rehberger previously met for an exhibition in 1938, also illustrated by Gus:

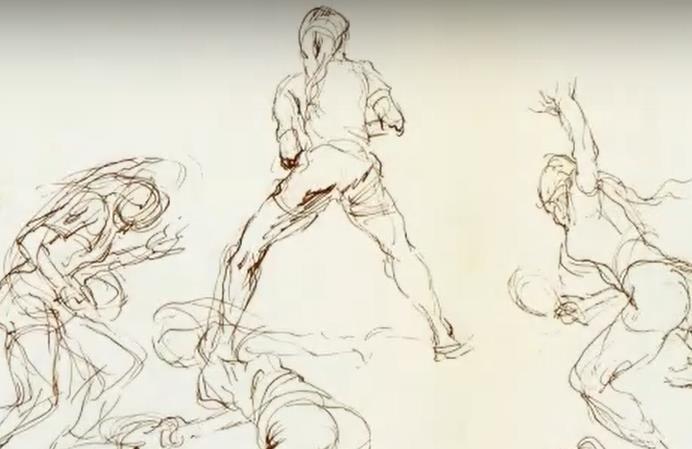

Only later did Rehberger’s art style mature into the “volcanic expressionism” for which he became known. TT Collector 88 shows many drawings that Rehberger did for the program of the 1962 U.S. Open. One was cut into separated halves , so we show it here in full:

At left is the full cover of that 1962 program.

When Dick Miles needed an illustrator for his 1968 book, he of course chose Gus:

Rehberger also did sketches for the 1972 U.S. Open program, including these:

See TTC 89, page 23, for a larger image of his cover design for that program (right) and the reaction to it.

Gus was one of the first Marlboro Men. This selfportrait as a conductor is one of four 1959 Marlboro ads he drew. Rehberger was a big fan of Beethoven and Toscanini. Soon, though, you had to be a cowboy to be a Marlboro Man.

Early-1940s shots of Rehberger.

Upstairs at Carnegie Hall was his home/studio, 1951 to 1995.

Gus Rehberger (see preceding article) was sometimes known as the “Babe Ruth of Table Tennis” because of his powerful forehand drive. But he wasn’t the only Babe Ruth of Table Tennis. Indeed, you could put together a whole baseball team of them.

Babe Ruth was known for his home-run power in the 1920s and ‘30s. He didn’t play much table tennis, but his daughter Julia was on the 1935 U.S. Corbillon Cup team (see our May 2024 issue, page 23).

Here are other Babe Ruths of Table Tennis, according to journalists of the past:

“Victor Barna of Hungary the Babe Ruth of table tennis, a stern-faced, balding, five-time world champion ... “ Men’s Journal article about Marty Reisman.

Jimmy McClure, the 1930s three-time world doubles champion from the U.S.

In 1940, Sandor Glancz, the Hungarian star who immigrated to the U.S., played an exhibition match against McClure in Yonkers, New York. On this occasion, it was Glancz, not McClure, who was described as the Babe Ruth of Table Tennis.

“Sol Schiff is sometimes referred to as the Babe Ruth of Table Tennis.” April 1952 newspaper article.

Jan-Ove Waldner of Sweden. But he was more commonly known as the Mozart of Table Tennis, the only player to receive that compliment.

Li Zhenshi, Tampa Tribune, July 1991:

Slugger Carr, an employee of Florida Power & Light, March 1939

In British periodicals, we found no Babe Ruths of Table Tennis. But there was one Jack Hobbs of Table Tennis Victor Barna in the 1930s. Barna probably appreciated that. Hobbs was a famous cricketer, and Barna tried that sport a few times. He later wrote in his memoirs, “A good British person and cricket are inseparable concepts ... No one can shake my conviction that if I had been born English, I would have achieved greater fame as a cricketer than as a table tennis player ... “ By the way, Hobbs loved table tennis, even playing in this filmed demonstration

Three Gusikoffians

First up was many , August 11, 1954. His secret: He is the U.S. table tennis champion. “Champion pie

Next was Marty Doss , April 26, 1961. This one you can view at

came

One non-Gusikoffian panel gamer was 15 Bochenski (later Hoarfrost), who appeared on both Tell the Truth in 1971. On each introduced as Judy Bochenski, just returned from the China Ping Pong Diplomacy trip. By quizzing each of them, the panel tried to guess the real Judy. “They pretty easily figured out it was me,” she told us recently.

Part Seven, Issues 85 thru 89

We continue our analysis of the 101 issues of Table Tennis Collector/Table Tennis History Journal. Those issues can be viewed at https://www.ittf.com/history/documents/journals/.

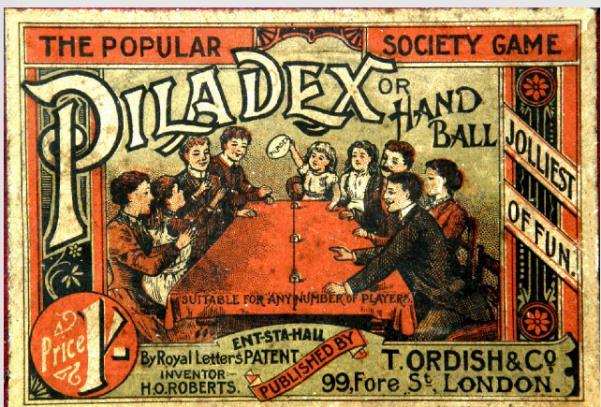

Issue 85 ***Page 4. Shows the 1902 table tennis set “Fluff-Fluff” but incorrectly states that Koocah is the maker. Koocah is the trademarked brand name, which the maker, Cook’s Athletic Co., London, used on a variety of sporting goods sold in Britain, New Zealand, Australia and India. That included Koocah Table Tennis, shown in Issue 96, page 67.

In 1903 Cook’s made a game called Koocah, or Circle-Tennis: In place of the table tennis net, the ball was hit through a large circular tin frame, pictured here, which had a built-in ball rack at the bottom.

Henry Adcock Cook (1858-28) started Cook & Co. in the 1880s or ‘90s. It went through several partnership changes and a name change, but Cook owned the firm when it was forced into winding-up in 1928. He considered himself a financial failure and was depressed, according to his son at the March 1928 inquest. Coroner’s ruling: “Found drowned.”

Issue 85 ***Page 8. We learn from F.A.O. Schwarz, the New York toy store, that in 1902 it offers tables in two narrow sizes: 8 feet by 4 and 9 feet by 4 (versus the Cavendish Club standard of 9 x 5, still in use today). They add (below) that the green cloth cover is marked off like a tennis court. Meanwhile, in London, H.G. Goodwin & Son was offering the same sizes plus an 8 x 5 and 9 x 5, each made of composition-board guaranteed not to warp. At a March 1902 tournament in Vienna, tables were 2.62 x 1.3 meters, or about 8.6 x 4.3 feet.

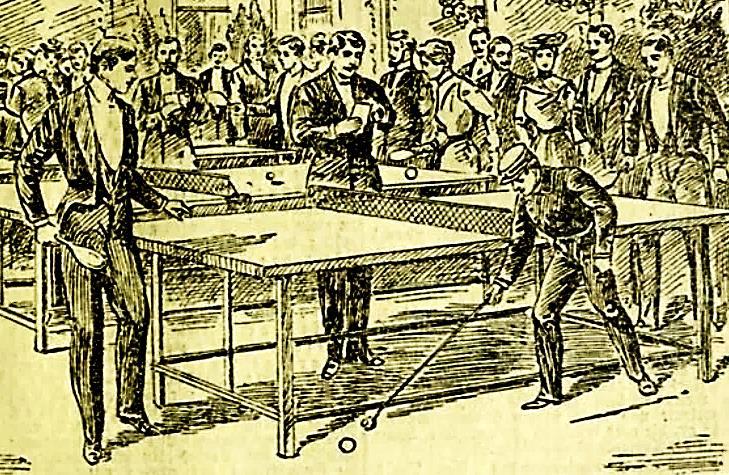

Issue 85 ***Page 10. Shows this newspaper photo (left) from a 1902 Vienna tournament (shown again in Issue 91). Correction: The tournament was not held at the Ramblers Sports Club (the organizer), but rather at the Continental Hotel. The three-day “international” competition, March 10-12, included at least a couple of British expatriates. Four events were offered: men’s and women’s singles, and men’s and women’s handicap. Spectators included several members of Austrian nobility. The English organizer, Edward Shires (right), easily won men’s singles, the score in the final being 30-21, 30-21. He also won the handicap. Shires (1879-1937) was a top football and cricket player, too, and his father was a founder of the Vienna Cricket and Football club.

Issue 85 also showed a drawing (from a photo) of the November 1902 tourney at the Vienna Bicycle Club. At left is a sharper cropped version. An added fifth event, mixed handicap open to both men and women, was won by Shires, who also took the men’s open to extend his reign as the most successful 1902 player in town. About 80 people attended the posttournament banquet.

Issue 85 ***Page 11. A photo shows eight top 1926 players, including these four Austrians. Interestingly, they favor longhandled bats. On the left are Eduard Freudenheim (1925 and ’26 Austrian champion) and Trude Wildam (ten times Austrian champion), who partnered for mixed doubles bronze at the first world championships in 1926. Trude was also the 1929 world silver medalist in singles and doubles. Also pictured is her husband August Wildam, 1924 Austrian champ but more successful in hockey as the long-time captain of the Austrian team. The other woman is Josephine Wiesenthal, 1923 Austrian champion, 1926 German Open winner, and sometimes Trude’s doubles partner.

Issue 85 ***Page 48. Shows the February 1902 ad at left placed in Games Gazette by Herbert Benham.

We’ve met Benham before. It was in Issue 76, page 27, where he was listed (below) as the author/artist of a copyrighted drawing in February 1902. See the issue for that interesting drawing of royalty and statesmen.

Issue 85 ***Page 49. Shows this February 1902 ad (left) placed in Games Gazette by Arthur Friedheim (misspelled Freidheim).

We’ve met Friedheim before: See the copyright entry above. Friedheim came to England from Germany in 1870 and started this company in 1898. It failed in 1905.

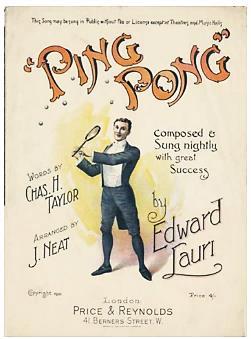

Issue 86 ***Page 3. The “Ping Pong Song” polyphon disk is shown. This can be heard at polyphon, where you can also see the polyphon machine in operation. But that is just the tune, without singing. Here are the lyrics, written in early 1901 by Charles H. Taylor, when the craze for the game was very new:

"When I went home the other night, And open'd the parlour door, I nearly fell on my back with fright, I heard such a wild uproar; I thought at first that the family Was mad, or the house aflame.

But I found we had only some friends to tea, Who were learning a parlour game.

(Chorus) They were having a game of Ping-Pong, Ping-Pong, Ping-Pong, And all agreed it was indeed, A wonderful game to play; But what'll I get for what remains, Of the ornaments and the window panes, When the popular game of Ping-Pong's been and had its day?

When an evening at a house you pass, Where Ping-Pong's on the whirl, And happen to meet the kind of ass Who flirts with your Sunday girl, You can give him a lovely smack in the eye With an accidental stroke, And everybody who's standing by Will appreciate the joke.

(Chorus) For it's only a game of Ping Pong, Ping Pong, Ping Pong, They're all agreed it is indeed A wonderful game to play. But you wonder how you are going to hash The chap who endeavours your girl to mash, When the popular game of Ping Pong's been and had its day.

For neighbours we've a man and wife, And very much out they fall, So we frequently hear the sounds of strife Distinctly through the wall. The other night I was really sure That blood was being shed, So I went and gave a knock at the door, And the husband came and said:

(Chorus) They were having a game of Ping Pong, Ping Pong, Ping Pong, And we both agreed it was indeed A wonderful game to play. Then across the lobby a saucer flew, And we're wondering now what they're going to do, When the popular game of Ping Pong's been and had its day.

I hear the House of Commons Now Is smitten with the craze, For certain members like a row, And fancy that it pays. One night the Speaker they defied, And an awful rumpus made, So he beckoned some men in blue inside, And spat on his hands and said,

(Chorus) "Well, let's have a game of Ping Pong, Ping Pong, Ping Pong, We're all agreed it is indeed A wonderful game to play. It's ten to one that I bag the pool, And you shan't have a chance to play the fool, When parliamentary Ping Pong's been and had its day."

Issue 86 ***Page 7 and Issue 87 ***Page 27. Rare English Foley porcelains are shown, with the observation that only three pieces are known with a table tennis theme. Moreover, all three had the same image, yet the 1902 government registration (left) showed six different designs. The editor asks for help in finding more pieces. We have now found more see page 43.

Issue 86 ***Page 12. Discusses a 1902 British trademark filing by Marie Robinson Wright of Philadelphia for the name “Pom Pom” to be used for an unspecified table game. Not mentioned is that two days earlier, in her home country, the U.S., she had filed a patent application for a game involving a spinning top that knocks down pins. The name Pom Pom was absent in the filing, perhaps because that title was already being used in the U.S. by Wright & Ditson for table tennis or table badminton. Also not mentioned in the TTC article was that, a few weeks earlier, according to a local newspaper in Hull, England, a resident of that town, Marie Robinson Wright, filed a patent for an unspecified game. Well, she WAS famous for her travel writing, and perhaps this Philadelphian got around even more than we realized.

Issue 86 ***Page 28. A 1901 newspaper article describes Euchary, which is simply table tennis with an alternate way of affixing the net, without clamps that can harm the dining table. We found an example of a box lid:

TTC 99, page 57, shows the quite ordinary contents of one example, with long-handled drumhead rackets. Contrary to the description given, Euchary is just the product name, not the manufacturer, which was H.E.H., London, according to a 2003 Christie’s auction catalogue.

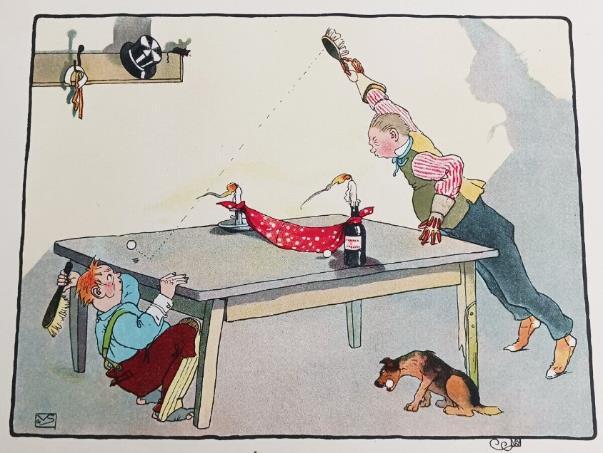

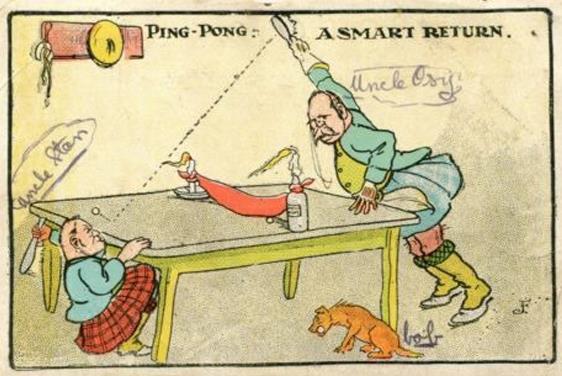

Issue 86 ***Page 55. Below left is a drawing from the 1904 book Comic Sport & Pastime (left), published in London and New York. The book featured drawings of 12 different sports, including mountaineering, motoring and fishing, each accompanied by a comical poem. TTC 86 showed a similar drawing (below right) on a card postmarked 1915 in New Zealand. In the intervening 11 years, the participants had aged considerably and changed their apparel radically, including the hat on the hook.

Issue 87 ***Page 26. Shows a 1902 newspaper article that incorrectly states that British Xylonite made ping pong balls at its Brantham factory. We tell all about the once-beloved Halex ball on page 35.

Issue 87 ***Page 45. Mentions Launceston Elliott, the famous Scottish strong man, as an entrant in the big December 1901 tournament at the Royal Aquarium in London. When it came to athletic competition, Elliott (1874-1930) drew no boundaries. At the 1896 Athens Olympics, he competed in wrestling, rope climbing and the 100-meter dash and won gold and silver in the weightlifting events. The 1900 Olympics had no weightlifting, so he entered discus. Outside the Olympics, he won bodybuilding contests with his 6’2”, 225-pound frame. When ping pong came along, he had to try that, too (as did his wife). M.J.G. Ritchie wrote (see TTC 91 for Ritchie’s newspaper series), “Anyone who has seen Mr Elliot’s massive frame and enormous muscular development, for he has been quite the strongest amateur weight lifter in the world, will appreciate the smile that went round on the countenances of the bystanders, who quite expected to see Mr Elliot smash the ping-pong ball to pieces at his first stroke No such thing happened, however, and if there is any special point about his game it may be said to be generally noted for its weakness.” In the opening round robin, on a draughty night inside the Aquarium, he lost to Roper Barrett (right), later a gold medalist in tennis at the 1908 Olympics and three-time Wimbledon doubles champ.

Issue 87 ***Page 58. Shows this artwork (left) by important Croatian artist Milivoj Uzebac (1897-1977), who lived most of his life in France. Four players are swinging simultaneously at two or more balls. This was one of many sports drawings Uzebac did for a 1932 book, Joies du Sport. In 1954 he painted actress Lilli Palmer (right), probably without knowing she was a former high-level table tennis player. Our May 2025 issue had a profile of this 1930 German team member, known then as Lilli Peiser.

Issue 88 ***Page 4. Repeats the mistake made in Issue 76: Victor Barna was awarded the halfsize replica of the St. Bride’s Vase for his fourth singles world championship, not his third.

Issue 88 ***Page 9. Discusses the 1889 Peerless Parlor and Lawn Tennis set. For more on this rare U.S. set, including an example with possibly original celluloid balls, see the book Ping Pong Fever: The Madness That Swept 1902 America, page 201.

Issue 88 ***Page 14 and Issue 89 ***Page 23. Shows the table tennis art of table tennis player Gus Rehberger. For more, see page 12 of this issue.

Issue 88 ***Page 21. A brief discussion of the 1930s gold medalist Gertrude Kleinova Vogel and her coach husband made us want to know more. See page 48 for their moving story.

Issue 88 ***Page 22. Our English colleague Alan Duke relates the history of Hamleys toy store in the first of a two-part series. Alan raised questions about the firm’s beginnings. Given his groundwork, we have dug deeper and found that the supposed 1760 founding date of this children’s store is an adult’s fairy tale. See page 31.

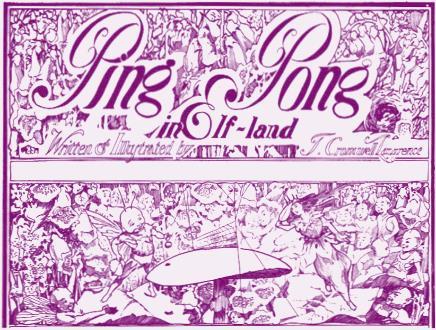

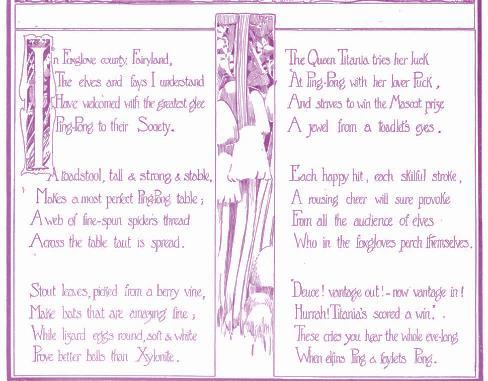

Issue 88 ***Page 31. Shows a drawing from the July 1902 issue of The Delineator, but not the poem it illustrates, so we provide it here. The poem was reprinted as the last entry in A Little Book of Ping-Pong Verse later that month.

Issue 88 ***Page 34. Shows German versions of the English postcard series “Ping Pong in Fairyland.” Here is one more, wishing a Happy New Year:

Issue 88 ***Page 58. This medal found its way to eBay. This was the first of 14 gold medals that Nancy Jackson won at the Welsh national championships from 1930 through 1946. That included six singles titles won consecutively 1935 through 1939, and then 1946 at age 43 when the war-interrupted series resumed. After marrying fellow Wales team member H. Roy Evans in 1933 or ‘34, she variously went by Nancy Evans, Nancy Roy Evans or Mrs. H. Roy Evans. At right, Nancy and Roy are front and center in this crop of a 1935 group photo. In the decades ahead, they became well known and admired for their leading roles as international administrators and organizers. Roy’s book Coloured Pins on a Map: Around the World with Table Tennis was published in 1997. They died two months apart in 1998; he was 88 and she was 95.

Issue 88 ***Page 61. The TT Collector caption says this card was signed and dated 1947/48, but of course that’s not really the date of the signature. It’s the season of Bergmann’s third world singles championship title. Bergmann was simply updating his printed publicity card. According to this card, he won the title every year during the war yet no championships were held in those years. Bergmann always liked to say he was the undefeated champ during that long span. He never tired of his role as impish promoter extraordinaire.

Issue 89 ***Cover and Page 17. Claims to show the first ad for a Barna bat, August 1933, in the French magazine Ping Pong. But this was not the first; Issue 90, page 16, shows an ad from a month earlier in the same publication. And a month before that they ran a pre-announcement ad.

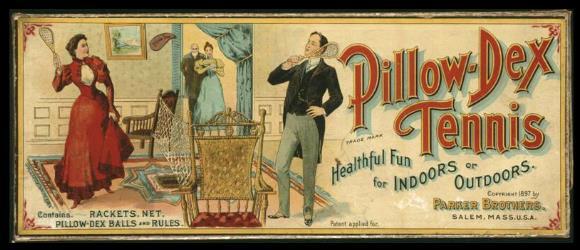

Issue 89 ***Page 6. Shows a Pillow-Dex Tennis set, copyright 1897.

This description is from the 1899 Parker Brothers catalog:

A box insert claimed, “It is the only indoor game resembling tennis!” Soon, of course, a much more popular indoor game took its place: Ping Pong.

Pillow-Dex Tennis had a rather short life. It never sold as well as the lower-priced original Pillow-Dex, played without racquets, which was still in the Parker catalog in 1931:

But below is the real original, from 1890 England, before it was stolen to the U.S. by Parker and craftily renamed.

We have now translated Victor Barna’s privately published autobiography (see the January 2025 issue, page 19). We will share the revelations, starting in this issue with the car accident that jeopardized his career. TT Collector 79 related that story as told in French newspapers. But the papers missed the full story, even omitting the front-seat passenger, a beauty queen.

Barna, only 23, was already five-times world singles champion. Accompanying him on the May 1935 exhibition tour through France were fellow greats Laci Bellak (age 24), Raymond Verger (about 26) and Alex Ehrlich (21), and manager Constant Bourquin. Writing 20 years later

... I bought a car, my first! It was a French-made Fiat, the latest 1935 model. After the old jalopy [on the previous tour], this was a great experience. I was looking forward with joy to continuing our campaign journey.

Many of my friends urged me to take out insurance for any possible accident, but especially for my right arm, which meant my livelihood. Thinking back to the fact that I had recently just narrowly escaped an accident while rolling down a mountain, I decided to take my friends’ advice. I discussed all the details with my agent and only formalities remained, i.e. signing, paying the first premium, etc. The agent agreed to come to my place in rue Gervex [Paris] at 11 a.m. on the opening day of our tour. I waited almost until noon, but he didn’t show up.

Since we had hundreds of kilometers to travel that day for the first exhibition, I gave up waiting. There would be plenty of time to finalize the deal when I got back.

I had never played better in my life. In addition to my youth, I had enough experience and was in great physical shape! But the campaign tour was not a cakewalk. In France, our evening performances never started before nine. The French like to eat their dinner first. Accordingly, after our own dinner and other obligations, we rarely got to bed before 2 a.m. We covered an average of 120 to 150 miles a day, sometimes more, so you can imagine we needed endurance. We were testing our youth.

Below: On their earlier tour, in 1933, Barna, Bourquin, Bellak and Verger are hosted at the Luchon stop. These same four ambassadors reunited for the 1935 tour, joined by Ehrlich.

I usually won my matches. We played for the audience, but we also tried to beat each other ... In Dijon the table we had to play on was terrible. This in itself was nothing new, as we had encountered more bad playing conditions than good ones during our trip. Slippery floors, bad

tables, tight space behind the table, all of this was not unusual. But this table was really slow, almost unusable.

Ehrlich [left] found a Polish compatriot there and apparently wanted to show off how good he was, because at the beginning of our game his left hand was in his trouser pocket. He wasn’t trying to play a proper game. I would have taken advantage of that, but it was an exhibition match, so I purposely lost in four games. After the match, in a reckless moment, I promised Ehrlich that from now on I would beat him in three games every night. Laci and Verger, of course, enjoyed the situation very much. Every time Ehrlich and I played, they sat in the front row and watched the fight in good spirits. Over the next five nights, I kept my promise.

Then the inevitable happened. Looking back years later, I am sure that this was bound to happen. I drove hundreds of kilometers every day, drank like a Caesar, played grueling games every day, and I wasn't particularly shy about girls. It had to happen.

We played on the evening of May 9th. I didn't go to bed until six a.m., and by 10 a.m. we were on our way to Lancieux [actually Lorient]. We stopped for lunch at a seaside restaurant famous for its specialties. From beginning to end, every dish offered was seafood, and to make it go down better, we drank Muscadet with it. It was a very delicious lunch and I felt great. It didn't even occur to me that I should sleep. Anyway, it didn't matter, we had to keep going.

After lunch, Laci said that for the sake of variety, he would go on in Bourquin's car. So Raymond Verger traveled in my back seat, because a friend of mine was sitting next to me in the front. As a beauty queen, she did shows for Coty. She was also a table tennis fan and was traveling with us to Lancieux [Lorient] to watch our show. [ nameless woman whom he had kept out of the newspapers

To make a long story short, we had a terrible accident. The car skidded off the road, overturned, and rolled three times before coming to a stop. queen on the side, and with my knee stretched out and tangled in the steering wheel, I was thrown all over the place. I thought the car would never stop.

Lying on the ground in the pouring rain, I had only one wish: to sleep! Although my eyes were closed, I was conscious and remembered every detail. Laci and Bour didn't take long for Laci to get to me. Blood was flowing from my forehead into my mouth, but Laci thought it was the other way around and immediately took off my gold watch. He was always very thorough.

My first words to him were: “I broke my playing arm.” I hoped it wasn’t true, but deep down I knew it had happened. Needless to say, I was right. They took us to the nearest hospital. My knees were crushed, there was a nasty wound above my right eye, and o worst possible place.

[Writing much later, Barna may have forgotten that Laci’s car also skidded off the road at that same notoriously dangerous curve, with no injuries. Right after, a third car crashed, killing a 22 female passenger from Lorient.]

I will never forget that excruciating first night in the monastery. I couldn’t move or turn around because of my knees, but to be honest, it wasn’t my own physical pain that tore at me. I received the bad news that Raymond was still unconscious, and my girlfriend's hysterical cry of "Tu m'a tué," or "you killed me," rang in my ears without ceasing.

Early the next morning, Raymond was the first to enter my room. A huge weight lifted from my heart. His head was bandaged and he seemed to be doing well. "How are you?" I asked him. He just laughed and said, "Ca va. Je suis devenu foux!" ("I'm fine. I've gone crazy."). Even years later, whenever he talked about the accident, he said that it had made him somewhat "crazy." As for my other "victim," she calmed down and nothing serious happened to her, except that they had to shave off a little of her golden hair. But it grew back and she received a very large compensation from the insurance company. We parted as good friends.

The local doctor wouldn't touch my broken arm. Since I was a champion, he didn't want to complicate the situation any further. He was subtly hinting that I might never be able to play again. Others later hinted at this. I just smiled! I was convinced they were wrong. My arm barely hurt, and I was sure it would heal quickly. They were wrong in a way, but now I see that they were basically right. I played again, but never as I had before the accident.

My good friend Hecht, with whom I lived in the apartment at 2 rue Gervex, came to pick me up in his car to take me home. But the doctor said I wasn't in good enough shape to travel by car. So we decided that I would go by train, in a sleeping car, while Hecht would take Raymond by car, and they would pick me up at the train station the next morning.

But when I arrived in Paris, no one was waiting for me. I took a taxi home, but Hecht was not there either. I didn’t know what to make of it. Then the phone rang in the hallway, and I was informed that my friends had been in a bad accident not far from Paris. They had collided with a truck and were lucky to survive. Raymond Verger had suffered only minor injuries. Of course, if there was an accident, he would be in it! He should learn to write his own story! The passengers of the first car that arrived at the scene of the accident were shocked to see Raymond already bandaged up. Well, this is a story you could laugh about - months later, though, because when it happened, it didn't seem so funny at all.

In my case, the doctors were arguing with each other. They suggested surgery, but they left the final decision to me. What should I do? How would I know what was best for me? So I relied on friends and well-wishers who convinced me to have surgery. The arm would have to be opened, the two broken bones then put together and reinforced with my table tennis career might have been over. After much hesitation, I decided to have the surgery. It wasn't painful, but as I lay in bed, doubts began to creep in. My self-confidence was shaken and the future seemed dark.

The following days brought even more gloomy thoughts. The first day after the operation, my hospital room was full of visitors. They kept coming. The next day, a few more came, but on the third and subsequent days, not a soul came to see me. I thought they had forgotten me. By the second week, I had really had enough. I dressed myself as best I could and rang the nurse to help me put on my shoes and call a taxi. The nurse protested, but I was adamant and went home. At that time, our home 2 rue Gervex had become a private clinic. I forgot to mention above that Hecht's fiancée, Yvonne, was also in the car at the time of their accident, so the apartment was full of the disabled.

I was also nervous about my family. Immediately after the accident, I asked Laci to send a telegram home that everything was fine with me. Of course, he complied, but that only complicated things. He signed the telegram "Viki", as he calls me. But to my family I always wrote "Viktor". So they knew I had not sent the telegram. Meanwhile, the Hungarian newspapers were full of gruesome details. Apparently, they had picked me up in pieces from under the car. I called home after returning from

the hospital. My sisters did not want to believe that apart from my broken arm, everything was fine with me.

They said that my mother had heart problems and that she knew nothing about the accident. They "censored" her newspapers and letters, and they asked guests not to mention what had happened. So as soon as the skin on my knees began to heal and I was able to travel more or less freely, I decided to go home. Bourquin also thought it was the wisest thing to do in this situation. I could certainly not find a better place to recover than at home, pampered by my family. They could hardly do enough to please me, and I lived like a king.

But something was making me angry. Wherever I went, acquaintances and even strangers stopped me to ask if it was true that I had made a fortune in insurance. Rumor had it that I had made £15,000 in this way. [One newspaper said 200,000 Swiss Francs; another, 50,000 Hungarian Pengo.] When I said "no," they naturally did not believe me. Finally I began to say "yes." I cursed my insurance agent countless times, and of course my own stupidity.

The first part of my recovery was very pleasant, but as time went on, more and more serious things began to worry me. First, my mother had another heart attack. The doctors had given up hope, saying that one of the coronary arteries in her heart was blocked. I was beside myself and refused to accept their opinion. As the days and weeks passed, I began to believe that they were wrong and I was right!

Then it was time to take off the cast. It quickly became clear that something was very wrong. My arm still hurt a lot, and even weeks after the cast was removed, I still had no strength in it. I couldn't even turn a key to open a door, and shaving was a long, painful process. My arm felt like it had a piece of wood inside. The famous Hungarian doctor, Professor Molnár, who has helped many athletes, advised me to undergo another operation to remove the plate and screws. In his opinion, these fasteners were not necessary at all and only caused complications.

He asked me to come to him the following week. If my arm continued to hurt, he would operate on me. But I was stupid and hoped that this was not necessary. So when I went to him, I said that it was much better. To which he replied that "if it doesn't bother you, then let's leave it for now " I wish I had said something different.

Of course, I really wanted to play again. I tried, but I wasn't satisfied. Everyone said that this was natural and that it would take months before I would be able to play properly again. I wanted to believe in this. I had full faith in my fighting spirit and was not willing to accept the idea that my career was over at the age of only 24.

My first competition was a great success. In September 1935 [actually Oct. 25-27, though Barna tested his arm in a local match on Sept. 7], the Hungarian Federation celebrated its "anniversary" and organized a "Hungary against the world" tournament. The members of the world team were Ehrlich (Poland), Kohn (Austria) and a third player whose name I no longer remember [Kolar, Czechoslovakia]. The dear reader has probably already noticed that I have a good memory for numbers. I can recall scores accurately even years later. I also remember faces, but as for names, unfortunately I don't remember them and always have trouble when I meet an "old friend" and can't remember his name ... I won my three individual matches and we won 7-2 [actually 6-3; Hazi lost two, Szabados one]. I also won the individual competition that followed the team competition Everything seemed to be fine with my game...

Barna’s future held more good wins, but l’Invincible never again reached a World’s singles final. This autobiography reveals that he finally had the plate and screws removed in 1942.

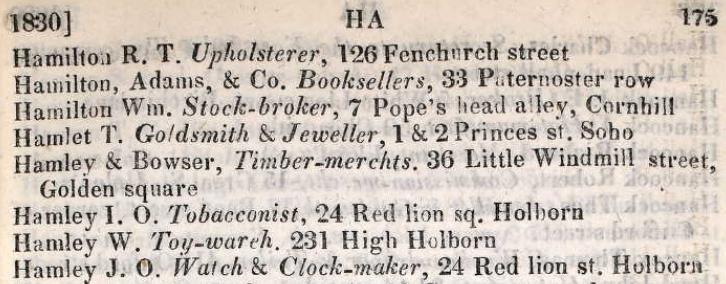

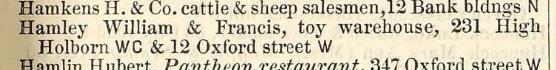

NOT TRUE: William Hamley, a young man from Cornwall, moved to London in 1760 with the dream of creating the finest toy store in the world. Leasing 231 High Holborn, he called his shop Noah’s Ark. Hamley’s son and grandson continued the mighty cause, and by the 1830s the highly successful famous store was attracting royalty and other prestigious customers.

This Founding Myth is on the Hamleys website and repeated across the internet. It is stuff and nonsense.

As the calendar turned to 1860, 56-year-old William Hamley thought back on the store he had been operating for thirty years. Until 1829, no Hamley was the proprietor of any London toy business, as verified by dozens of city directories. When William took over Noah’s Ark in late 1829, it had already been around for nearly 40 years, under several different names. Hamley had probably heard, without knowing the full history, that this had long been Benjamin Pearsall’s shop, offering toys, medicines and hardware. After Pearsall, several others ran it in the 1820s.

In ads, Hamley called his shop “old established.” But in 1860 he conceived a better idea. How about “Established 1760”? (Ads at right.) That would make his business exactly 100 years old, a nice, round, venerable number. If he overstated the age, who was to know? Even he didn’t know exactly when Pearsall started up, or if Pearsall had a predecessor.

Thus the seed of the Myth was planted. Hamley’s descendants couldn’t resist fertilizing the Myth, shoveling in a fabricated backstory, and it sprouted into today’s wondrous fairy tale of toy heaven history.

For the past 165 years, Hamleys has used “Established 1760” on multitudes of signs, banners, ads and websites, happily accepted by multitudes of historians, bloggers and wikis. At left is the Green Plaque erected by Hamleys at its Regent Street location when they celebrated their so-called “250th anniversary” in 2010.

A few others have questioned the Founding Myth, including our English colleague Alan Duke in TT Collector 88 and 89. Alan provided evidence that, until 1830, 231 High Holborn was the site

of other proprietors and/or other business types. Given the Hamleys 1760 claim, Alan called this a puzzling “loose end” requiring further investigation.

We now, for the first time, fill in the key remaining puzzle pieces.

London business directories of the 1760s show no shop at 231 High Holborn, and no Hamleys in any business. In 1773 Joseph Wilson entered the picture. He was a cabinet maker and auctioneer at that address until 1780. Then Thomas Waldron moved in with a similar business. The directory called him an “upholder,” meaning a maker of upholstered furniture who was often also a cabinet maker, undertaker, auctioneer and appraiser. (Waldron’s move to a fancier, larger showroom in the Strand ended in bankruptcy in 1790.)

In 1782, a saddler and harness maker named John Allingham took 231 High Holborn, remaining until his 1785 bankruptcy. In that year Henry Rider moved in, but his glass and china manufacturing business ended in his 1789 bankruptcy. Then it was the turn of haberdasher Samuel Lamb, who lasted only about a year until his 1790 bankruptcy.

The failures finally ended when Benjamin Pearsall installed his toy, medicine and hardware business. In those days, a “toy warehouse,” as the city directories called his shop, was more than just toys, generally stocking trinkets, jewelry, decorative items and more. Pearsall carried on for 25 years, until dying in 1818 at age 56. Associates kept the business going for several more years, still under the “Pearsall’s” name.

By 1824 or 1825, John Selot had taken over the store. He soon ran into trouble, though, and the ad at right appeared in late 1826, listing for sale everything down to the counters, shelves and gas fittings. (Part of Selot’s trouble was caused by non-payment of a debt owed him by another toyman, Henry Oppenheim of Mansell St.)

Yet just four months later, the shop was open for business again, this time operated by Ward and Co. The retailer had a new name, “Noah’s Ark”:

A city directory shows that the proprietor was John Ward, 23, the first of several Wards to enter our story. Then the 1828 and 1829 directories instead name John’s older brother William Lapthorn Ward as proprietor.

Meanwhile, John Selot, that 1826 owner, had recently been released from debtors’ prison (Fleet), yet another bankruptcy victim of 231 High Holborn. He agreed to work with creditors to satisfy his debts. Our William Ward (right) was the Assignee on the case, in charge of liquidating Selot’s assets and distributing them to creditors. Ward’s main line of business was a partnership with brother James Ward that sold building materials, elsewhere in London. Perhaps the Wards were involved in the toy store only because of a Selot debt owed them.

And now William Hamley, 25, ambles into the picture for the first time: He marries the Wards’ 20-year-old sister Ann Jane Ward in June 1828.

In 1829, the Wards gave up on Noah’s Ark. They were trying to liquidate the entire stock in August:

But then Hamley must have stepped up, agreeing with his in-laws to give the business a go himself. He is first listed as proprietor in an 1830 city directory:

Hamley had found his calling. This directory listing continued for another 44 years. Hamley’s wife died in 1832 after giving birth to their only surviving child. A good guess is that Ann’s 17-year-old sister Susannah Ward (1815-1895) then moved in to take care of the baby. She married Hamley in 1842, producing five surviving children. Hamley died in 1874. Two of his children from Susannah were newly listed in the 1875 city directory:

Now you know the real story: Hamley married into a shop opened by Pearsall before he was born.

Suggestion to Hamleys: If you still love the idea of an “Established” date, try 1829. You would still qualify as the world’s oldest toy store. A date in the 1790s, to include predecessors, would also work. As for the Founding Myth of a 1760 William Hamley coming to the big city with dreams of creating the best toy shop in the world, all fairy tales should begin with the words, “Once upon a time ... ”

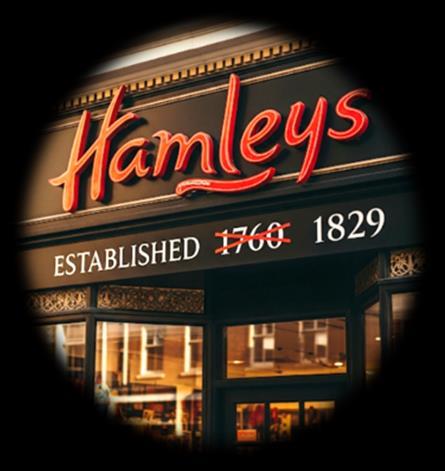

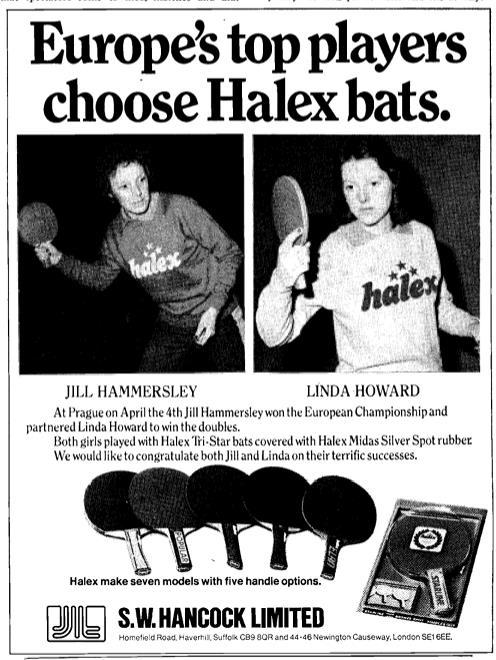

Certainly the older generation remembers. Halex in its day was one of the top brands officially approved by the ITTF and national associations. It could almost be called iconic. If you’ve read The Mighty Walzer, by Howard Jacobson, you might recall that its 1950s Mancunian title character rescues a ping pong ball bobbing in the local lake. It was a Halex 3-Star, and it launched this 11-year-old’s successful table tennis career. Halex remained a serious competition ball until the 1990s. You can still find them, but you would probably need to look in bodegas or grocery stores, not table tennis clubs.

British Xylonite trademarked the Halex name in January 1902, combining “Hale” End, their London location, with the X from xylonite, the British term for celluloid. Shown above is a 1950s product, along with the metal printing die.

A 1902 article described the company’s other factory, about 100 miles east of Hale End: “The works at Brantham practically make all the balls used in the game of the hour, at any rate as far as England is concerned,” adding that the work took place under conditions of secrecy. So secret was the work, that the newspaper got it wrong. No balls were made at Brantham. That factory made only the raw material, then sent the sheets, rods and tubes by land and water to Hale End.

As per the journalistic practice back then, this mistaken article was reprinted in more than a dozen unrelated publications across Great Britain. Flash forward another century-plus, and we see it reprinted yet again in TT Collector 80, p. 19. In the same issue, p. 25, our English colleague Alan Duke did not outright declare the article to be wrong but contributed a nicely detailed study of British Xylonite that set things straight. (We offer two corrections to that corrective: 1) Not all Hale End

works closed in 1971 the ball factory stayed in operation, having been purchased by M.Y. Darts Ltd. for £300,000. The new owner soon also used the Halex name on its darts and other sporting goods. 2) The British Xylonite 1938-39 reorganization included a third subsidiary, Cascelloid renamed Palitoy which made finished goods such as table tennis sets, not raw material.)

Yet that faulty 1902 article still refused to die, popping up again in Issue 87, p. 26. Then, referring to Margaret Thatcher’s employment at British Xylonite (1947-51), the contributor added, “But the production of ping-pong balls had, I think, long ceased. Does anyone know how long?”

The Halex ball remained on the short approval list of the English TTA for decades to come.

Halex made the popular Barna ball, too, as noted in the small print at the bottom of this 1940 ad. As for the ad’s claim of “perfectly spherical,” well, no ball is perfect. An ITTF study a few years earlier had found that roundness was a weak point of this ball choice, compared to Jaques’ Tema brand.

Used at the 1973 world championships in Yugoslavia: “Consistent Speed, Perfect Bounce, Longer Life”

1924

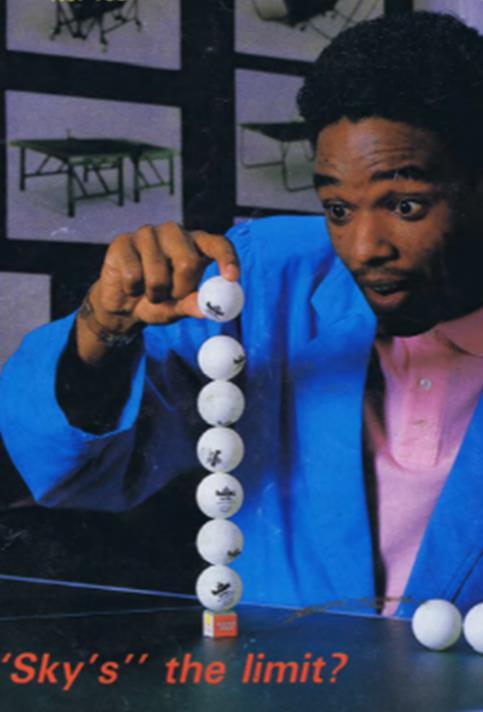

New owner M.Y. Darts added bats (left, 1976), rubbers and tables to the Halex product line. In the 1980s, Halex was a top sponsor of English table tennis, putting its name on leagues, league teams, tournaments and even the national ranking system. But keeping all the balls aloft proved too tricky (right, Halex balls on a 1987 cover of Table Tennis News, with English international Sky Andrew), and in 1993 the firm toppled into receivership.

British Xylonite used the Halex name on other celluloid products, too. Indeed, if you asked the 20thcentury British man in the street what the name “Halex” calls to mind, he would most likely say “toothbrushes.”

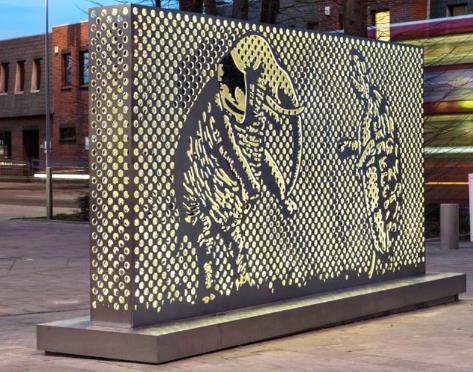

The former site of the Hale End factory is remembered today with an elephant and tortoise sculpture, symbolizing the animals saved when xylonite took the place of ivory and tortoiseshell in household items. Visitors are invited to write their fondest wish on a table tennis ball and insert it into the sculpture. The most common wishes are peace, happiness and love.

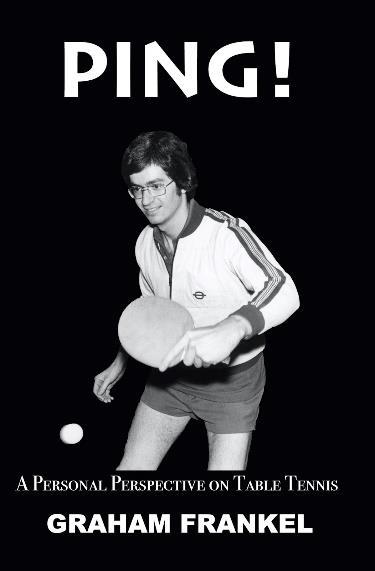

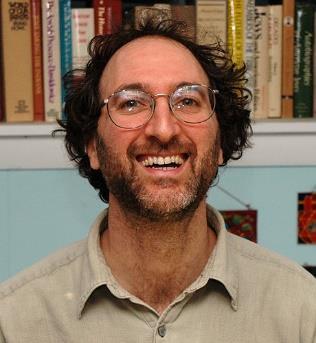

by Graham Frankel (England)

One of the chief benefits of studying history is learning from the past. When I began studying table tennis history I had been addicted to the sport since childhood. During the latter part of my fifty-year playing career I began to have some misgivings about how table tennis had evolved in England. I had no intention of simply abandoning the sport. Luckily for me, I made a very satisfying transition from playing to coaching. This increased my determination to dig in and see what had really gone wrong. How had England slipped from being one of the leading nations in the sport, to a level where they could no longer compete seriously against other European nations, let alone the rest of the world?

There were early surprises in my research. When I studied the world ranking lists from the 1950s, it appeared that the problems began during that decade. At the start of the 1950s all was going well. Johnny Leach had become World Champion in 1949 and 1951. British women regularly reached the quarterfinals in the world championships during the early ‘50s. Indeed, at the 1954 world’s there was a British woman in every quarterfinal match singles, women’s doubles and mixed doubles. But by then, the sport had already witnessed the start of a dramatic evolutionary step. At the ’52 world’s Hiroji Satoh of Japan (left) emerged from obscurity to conquer the best in the world, using a sponge racket. This sponge was nothing like the coverings on today’s rackets, and his skill was not in topspin but mainly spinning the ball below the surface of the table. This kind of sponge was not new. But until Satoh arrived, it was not seen as a threat.

Over the next seven years, the table tennis world became embroiled in a bitter dispute, divided into two camps. On one side, England and Germany, followed by some other European countries, were in favour of banning sponge completely and standardising with the traditional pimpled rubber. On the other side, most Asian countries favoured allowing sponge. A few leading nations, including the USA, were undecided. The November 1955 editorial of Table Tennis, the ETTA’s official magazine, gave a melodramatic summary of the situation after the first three years of the conflict:

England’s opposition to sponge created significant problems for their leading players who had already made the switch. For several years they were faced with a bizarre situation, banned from using sponge at English tournaments but not in most other countries. Faced with this frustration, Ann Haydon (right), who reached three finals at the 1957 world championships, abandoned table tennis completely and focused all her energy on tennis, going on to win Wimbledon in 1969.

As the sponge war dragged on, the ETTA believed they would influence the rest of the world to follow them in banning sponge. In the light of what would ultimately happen, it is clear that this was an arrogant view, totally unfounded.

The war over sponge continued for longer than either of the two World Wars. In 1959, peace was declared at the ITTF meeting during the world championships at Dortmund. Sponge would be allowed, but with restrictions on the materials and thickness. By now, however, sponge bats had evolved significantly. The “reverse pimples” sandwich racket, capable of imparting heavy topspin, had been invented. The era of topspin attack had arrived. Given that the majority of British players had followed the advice of the ETTA and not used any kind of sponge, it is likely that the eventual compromise left them at a disadvantage.

The seven-year sponge war may have been the start of England’s decline in table tennis. But it was not the only cause. After the Dortmund compromise, other European countries in particular Germany, France, Sweden, and the Netherlands began to recognise the possibility that table tennis could become a professional sport. Before I launch into a brief analysis, note that there are no less than seven national governing bodies for table tennis in the UK. England is by far the largest, but most of my comments apply equally to all parts of the UK.

While most of the leading European nations were setting up professional leagues during the 1960s and 1970s, the UK governing bodies had no intention of changing from the strictly amateur status that had always prevailed.

Across the whole of the UK, a vast network of local leagues provided all the competing opportunities required for most players. Every league was loosely administered by the county in which it was situated. The league boundaries overlapped, enabling clubs/organisations to participate in multiple leagues. Players could also appear in as many different leagues as they wished, even representing different organisations. This gave keen players the possibility of playing competitive table tennis on every weekday evening. Weekends were reserved for tournaments and inter-county competitions.

The vast majority of British players were oblivious to the significant changes in table tennis in the rest of Europe. Few noticed when Trevor Taylor, 23, moved to the Netherlands in 1975 when a Dutch club offered him a professional contract. It merited the briefest mention in the 32-page Table Tennis News:

It was the start of a trend that has continued to the present day.

While most British enthusiasts were unaware how the UK was falling behind its European rivals, a vocal minority of the top players were pushing the national governing body for changes. This was nothing new. The ETTA had been under pressure for many years to recognise their international stars in a more tangible way. Finally, the ETTA changed its regulations, allowing players to earn money from table tennis. In 1979, the door was opened for the creation of a National League. It was highly controversial. Opposition came mainly from the county associations, because National League matches were scheduled at weekends, clashing with the inter-county competitions. Local league players did not see the National League as a threat, for two reasons: 1) The vast majority were moderate players who had no expectation of competing at the high standard offered by the National League at its inception; and 2) There was no scheduling problem, since local leagues operated entirely during weekday evenings.

What the local leagues failed to appreciate, in those early days, was that the National League would eventually expand. As this happened, local league play became unattractive for the top players. Leagues also failed to see other factors that would chip away at participation levels. Companies and other organisations who funded teams became less inclined to support these minority activities as economic pressures limited budgets.

The National League organisers had high hopes for generous sponsorship. For a while, their optimism appeared to have some justification. Sponsors were found for the league and for some of the more successful clubs. But this support dwindled steadily, and at the same time national media interest in table tennis dropped to almost zero.

By the turn of this century it was starting to become clear that local leagues were dwindling in popularity. But the decline was extremely slow. A few leagues merged with others nearby and some disappeared completely, but most just carried on, not recognising the real causes of the decline. Players were uncomfortably aware that the average age of participants was rising steadily.

There were several harmful consequences of the local league culture. By offering players unrestricted freedom to appear in as many leagues as they liked, representing as many clubs as they liked, there was little opportunity to develop any significant club identity. Many of the local league clubs operated on one or two tables, making it impossible to allow any significant playing time outside the league matches, and any involvement of juniors or coaching. It was a commonly held misconception that youngsters were no longer interested in table tennis because of alternative opportunities for entertainment. The reality was that youngsters could very easily be attracted to the sport, but not to participate in local league matches that would often not begin until 8pm and finish at 11pm or even later.

Yet more problems went largely unnoticed. Allowing players to fill their weeks with match play (often competing against the same opponents) meant that they neglected skill development. Even worse, there was little or no expectation of efforts to help train others or encourage juniors.

As the leagues continued to shrink, the remaining participants needed to find someone to blame. The obvious scapegoat was the ETTA. As the governing body it must have been their fault that the sport no longer had national media attention, that UK players could not compete successfully against European or most other countries in the world, that the top British players almost never played in the UK, that top European and other world players never played in UK competitions, and of course that the local leagues were losing players.

The blame directed at the ETTA was almost entirely unfounded. Despite carrying the title of “national governing body,” the organisation’s primary activity was administering the wishes of its membership. The majority of members were those players who continued to participate in the declining network of local leagues. The counties, who in principle controlled the leagues, were represented by an enormous advisory body, the National Council. This archaic institution may have included some who saw the need for radical change. If so, they were always outvoted by the majority whose main interest was to maintain the league and county system that had been in place since the 1930s. They also saw themselves as the guardians of the main source of funding in the sport, which came from taxpayers via “Sport England” and “UK Sport”, both of which were intermediary bodies responsible for overseeing the distribution of funding to different sports.

The first decade of the 21st century was an uneasy period. An economic crisis was looming. Sport England took a closer interest in the success of the sports they were supporting. They brought in a team of independent consultants to review the issues in table tennis. Among their recommendations were the abolition of the National Council. The ETTA rebranded itself as Table Tennis England (TTE), but the National Council remained in place, and there were no other fundamental changes.

TTE survived the threats to their funding but remained powerless to bring about any radical change. The National League had now been rebranded as the British League. Rebranding was becoming a favourite method of pretending to implement genuine strategic change. While the British League was steadily growing, there were no prospects that any of its clubs would ever become professional. Leading British players continued to play in the European leagues, appearing in England only at the National Closed Championships. The English Open, once second in prestige only to the world championships, was last held in 2011. In recent years, top players from Europe and the rest of the world have not been seen in the UK.

The decline of British table tennis can be summarised by looking at the number of British players reaching the last 16 of the World Championships singles since 1970. During the 1970s, four British players reached the last 16 (Denis Neale, Trevor Taylor, Des Douglas and Jill Parker). In the 1980s two players reached the last 16 (Des Douglas and Alan Cooke). After 1987, no British players reached the last 16 until 2021 (Liam Pitchford) and then 2025 (Tom Jarvis). Meanwhile, no British player has ever won an Olympic medal.

The few British players who made any recent impact in worldclass table tennis did so only by virtue of playing in professional leagues outside the UK. Pitchford began playing professionally in Germany from the age of 18, and Tom Jarvis (right) has lived in Sweden since he was 16. These players are, of course, perfectly justified to make the decision to play in other countries. Their success demonstrates that if the UK could ever achieve a radical regeneration of the sport, we could expect to generate a reasonable flow of truly world-class players.

But I see no prospect of any substantial change. The archaic competition structure, held together by the National Council, coupled with total reliance on a chronically inadequate funding source will continue to block any chance of a professional level of table tennis in the UK. Youngsters with aspirations to reach world class will have to relocate to parts of the world where they can make a living from their skill and commitment. Table tennis is a sport where serious training needs to start early. To succeed as professionals, the youngsters from the UK will need to train and compete with their peers in other countries well before they reach 18 years of age. It is not difficult to imagine the problems this can create.

Despite all these issues, Table Tennis England have continued making strenuous efforts to convince members that all is well. Their reports fail to mention that any success has only been made possible by abandoning play in the home country. Instances of embellishing the truth have sometimes been extreme. Here is the opening of a recent report:

The article fails to explain that “WTT Feeder” events are not aimed at top world players. The average world ranking of the participants was around 170.

Other examples have demonstrated that Table Tennis England is out of touch with reality. At the Paris Olympics in 2024, when Team Great Britain returned with 65 medals in other sports, most of the reports from TTE focused on their team of volunteers umpiring matches. The failure of GB to progress beyond the last 64 was not even mentioned. Back in 1955, the English Table Tennis Association was also out of touch, even though the situation was very different. National arrogance, whether from governing bodies of sport or from governments, is nothing new.

Is there any hope for British table tennis? It is hard to be optimistic, based on the track record of the last 70 years. But learning from history would be a useful starting point.

© Graham Frankel 2025

For more about the conflicts in the evolution of table tennis, read my first book Ping!

My second book on table tennis is a novel, Kate’s Progress. Set in the future, it is the inspiring story of a young girl whose life changes when she discovers table tennis.

Both books are available from Amazon as paperbacks or Kindle versions.

TT Collector Issue 86 discussed the three known Foley table tennis pieces made by Wileman & Co. in 1902. They each displayed the same image:

Our English colleague Alan Duke found the design registration at left (Issues 73 and 87), indicating there were potentially five other table tennis designs out there.

I recently found one of those designs in Shelley Group magazine number 109, December 2013, a candy dish:

And the owner of Shelley Group, Gerry Pearce, kindly sent photos of this pin dish residing in Australia. The W intertwined with C stands for Wileman & Co.

That leaves three designs still to be found. Collectors are dreaming of finding all three missing images on a single piece, something like this:

Barring that, the full set would potentially be 30 pieces, multiplying the five known Wileman dish types times the six different images. A tough collector goal indeed! And there may very well be more than five dish varieties, so the full set could be 36, 42 or more pieces.

More within the realm of collecting possibility, but still very difficult, is the attractive 1904 Royal Bayreuth set. Former TTC editor Chuck Hoey, the honorary ITTF Museum curator, is the leading collector. He surveys the full scope of this set in TTC 44, including this photo (right) of his holdings as of that date.

Close-up of a cream pitcher:

More obtainable is this (Japanese?) set shown by our colleague Jorge Arango in TTC 99. It was made in several color varieties.

This children’s tea set, also described as Japanese, shows table tennis, too.

Pieces from this Chinese soup set are often found on eBay.

[This excerpt is from Appendix A of The Ping Pong Player and the Professor (2023). Author Richard Sosis is an anthropology professor, table tennis player, and father of a table tennis player.]

“Are you moving out?" Aviva, my youngest daughter, asks. I look at her quizzically but silently, pretending not to know what she is talking about. My kids like to pick on me evidently, I'm an easy target and I know from experience that responding verbally will only encourage her.

“What do you have in that thing? Aren't you just going to the table tennis club?" she continues.

A verbal riposte is clearly required

"Yes, but I have to bring stuff for Eliel as well," I say, which reveals shades of truth. I do bring some things for Eliel, but he does not request that I bring these things, and he brings a bag of his own to the club. I could fit three of his bags, even if they were overflowing, into my bag.

“And I'm over six feet tall so my clothes take up a lot of space." Also shades of truth. Over twenty years of fatherhood has helped me master this art. My clothes do take up more space than, say, Eliel's clothes, especially my size-thirteen sneakers, but this hardly requires a bag three times the size of Eliel's bag.

She is not satisfied, so I try a different tack. I rely on wisdom from her Girl Scout days for the rescue.

"Isn't your motto 'always be prepared’? I just want to be prepared in case we need anything at the club." I think my argument is unassailable. Aviva is undeterred, although I think she is surprised to learn I was paying attention to the Girl Scout activities of her youth.

"So why is your bag ten times the size of Eliel's bag?" We've entered the world of exaggeration, and I know this is not an argument that can be won or lost. It's simply the way my kids remind me that I'm a nut and they know it. I consider a parting shot to Aviva, but for the moment I play the role of the adult and wisely refrain.

I pick up my bag, realizing that under the circumstances I can't, without risking further insult, ask Eliel to carry it to the car as I usually would. "See you later!" I exclaim through a forced smile. "We'll be home after dinner."

Aviva and my other children, as usual, are not wrong. We often joke that I could fit a Chinese coach inside my table tennis bag, which of course would be more useful than anything actually in the bag. In my defense, I'm open to the possibility that I'm a nut, as my children insist, but lugging around my large bag feels rational to me. And since my goal in this book is to make the obscure world of table tennis seem normal and natural to readers, I think it is worth defending myself and justifying the size of my bag.

The bag was purchased at the U.S. Nationals in Las Vegas. To evaluate my purchasing decision, one must fully appreciate the size of the playing hall at the Nationals. The yearly tournament is held, at least in recent years, at the Las Vegas Convention Center. I don't know the square footage of the playing hall, but I can report without exaggeration that it takes about five minutes to walk from one end to the other. The place is massive. Moreover, the walk from the hotel to the playing hall, even though the hotel is connected to the convention center, is considerable. On our first day at our first Nationals, in 2016, I schlepped my medium-sized table tennis bag over one shoulder, a cooler bag with snacks and lunch food over the other shoulder, and a backpack across my back, which held my computer that I was reluctant to leave in our hotel room. After a few hours it was clear that this was unworkable.

Most of the major table tennis companies have booths at the U.S. Nationals, so I poked around the booths and stumbled across my solution: a bag that could fit into it all three of my current bags, and most importantly, it had wheels. I didn't hesitate. I made the purchase, stuffed in my other bags, and rolled my behemoth away. This was a literal weight off my shoulders, and I felt like I was flying at that moment. Afterward, on many occasions, I would remark that this bag was one of the best purchases of my life and I still stand by that sentiment.

I'm aware that my defense has holes. As Eliel likes to point out, yes, the behemoth bag makes sense for Las Vegas, but we are there only once or twice a year. Why carry it around for the rest of the year? Here l am on shakier ground, but my rationale is a combination of Girl Scout principles noted earlier, an insatiable tendency to hoard, and an inherent laziness that rarely goes unpunished. The bag is not only useful for Las Vegas, but it is useful for all tournaments because it carries everything we could need at a tournament, which I'll describe in a moment. Eliel attends a tournament about once a month, so the bag has been put to good use.