TABLE TENNIS HISTORY

Our cover star Marty Reisman was on several covers in his lifetime. Below is one I came across recently while sorting through my old boxes of memorabilia --- the cover of a 1980 takeout menu.

I suppose Reisman scored some free meals off of that. He enjoyed hustling an angle in anything. In the upcoming new movie Marty Supreme, it will be interesting to see how they portray the character inspired by him. They certainly chose the right table tennis player for an action-comedy. (My second choice would be Richard Bergmann, man without a country.)

Grateful thanks go to our three new contributors in this issue from Japan, England and Hungary. Articles, ideas and comments are welcome. You can reach us through our TT History website.

The Swaythling Club International website makes our past issues available on its Publications page.

Steve Grant

Cover: Marty Reisman, 44, doing his thing for a Time magazine photographer in 1974.

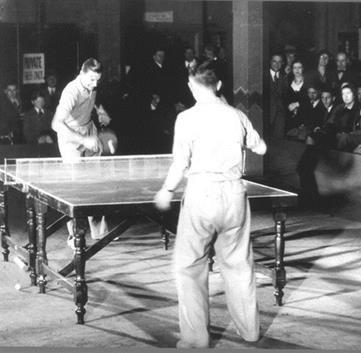

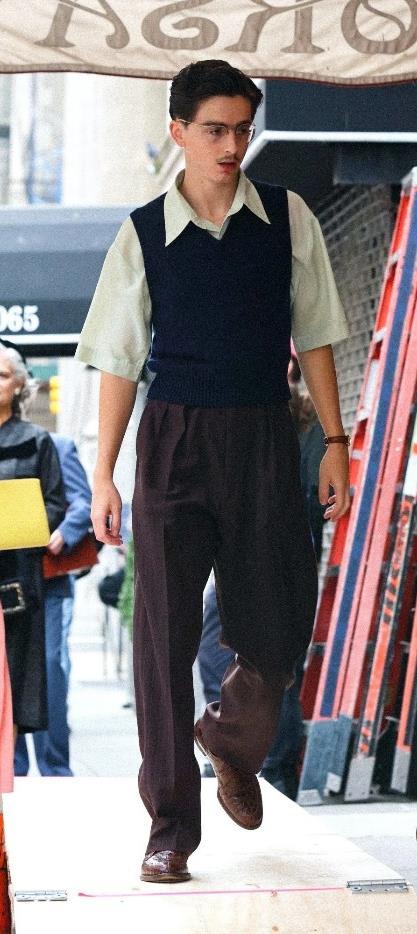

That’s the title of a new movie in the making, “inspired by” U.S. table tennis star Marty Reisman (1930-2012). Think of it as an adventure-comedy, with the story line taking whatever path maximizes the adventure and the comedy, regardless of Reisman’s actual life. Filming began in New York City in September; scheduled release date is Christmas Day 2025. Even if you know the star Timothee Chalamet, 28, from Dune or Wonka, you may not recognize him in Full Reisman (left). Gwyneth Paltrow plays his older love interest.

We served as a history consultant and can give you a small sneak peek. Settings include 1950s New York City, Paris and Tokyo. The director Josh Safdie, 40, frequented NY table tennis clubs in his younger days and wanted to get the details right. For example, he was concerned about the exact look and feel of Satoh’s 1952 sponge bat and what ball brand was then used in Japan. Above is one of the film props, a sidewalk wall sign in New York.

Little known is that this is not the first ping pong rodeo for director Safdie. The Pleasure of Being Robbed (2008) has a four-minute scene at a table tennis club in New York’s Chinatown, where the female protagonist, a troublemaking novice (below right), enters a tournament. Some of the real players (below, from the film) probably still don’t know they were in this low-budget production. This club happened to be my hangout at the time but closed a few years later. You can watch the 68-minute film here; table tennis starts at the ten-minute mark.

But getting back to Reisman: The movie is not his first big publicity event. It is now fifty years since he toured the U.S. to promote his book The Money Player in 1974. For an article on Reisman that year, Time magazine enlisted photographer David Gahr, best known for his photos of famous musicians. Gahr’s contact sheet appears for the first time anywhere on the next two pages. None of these images made it into the article, shown in part on page 7.

magazine, Nov. 11, 1974

Reisman’s 1974 book presented good autograph opportunities.

To my good friend Walter

After watching you play I can see that a new star looms on the horizon.

Marty

4/21/78

P.S.

I helped Kokomo the Chimp so there is hope for your game!

M.

8/7/74

Dear Norton,

This gift to you is a token expression of my high regard for our friendship.

I hope that we can be friends long after the R.T.T.C. [Riverside TT Club] is just a memory.

Thanks very much for your dedicated & loyal patronage of my place.

Best wishes in all your future endeavors.

Sincerely Marty

To my good friend Bob

The only guy who has beaten me!

See next page for details of the exciting match that Bob won.

over please

I gave Bob 18 points while I was seated in a chair. He hit the net once and the edge twice.

Best wishes Marty Reisman 3/21/77

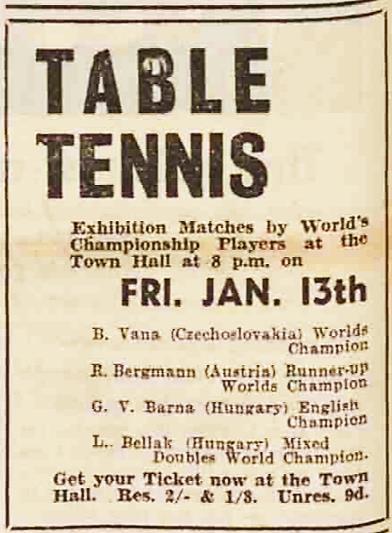

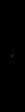

How about this for a show? Hire the 1937 world champion Richard Bergmann, 20, and the man who took the title away from him in 1938, Bohumil Vana of Czechoslovakia, just turning 19. Pit them against each other right before the 1939 world championships. Don’t stop there. Add two old-timers from the 1938 world champion team, Hungary Victor Barna and Laci Bellak, each age 27 and see how all four do against each other. Wait, there’s more. Let England’s best test their mettle against the stars, too. And Bellak will perform his table tennis comedy act, with Barna as straight man.

Worth seeing? In 30 towns across England, from Jan. 11 to Feb. 25, sold-out crowds said Yes! Fans also got to watch these players battle it out in three important tournaments, including the 1939 English Open in late January, where the finals drew over 8,000 spectators.

It was a lucky break that the timing worked out just right. Barna and Bellak had recently finished their tour of New Zealand, Australia and India, followed by the French Open in late December 1938, where Barna beat Bellak in the final. Vana, meanwhile, was just arriving in England after his 19-city exhibition tour of the U.S. And Bergmann had recently left uninhabitable Austria to become an English resident (still wearing his AusTria shirt, above). Best of all, the 1939 world championships would start later than usual, March 6, so the players had weeks of availability before making the trip to Cairo. (Bellak went to the U.S. instead of Cairo.) The same players had staged a very similar and successful tour a year earlier, but in that case it was after the English Open and after the world championships. This year Vana and Bergmann would instead treat fans to a fiercely contested preview of their upcoming rematches.

Jan 11 Chelmsford

Jan 12 Ilford

Jan 13 Cheltenham

Jan 14 Southend

Jan 16 London

Jan 17 Burnleyp

Jan 18 Corby

Jan 19 Sittingbourne

Jan 21 Hampshire tourn.

Jan 23 Chard Junction

Jan 24 Coventry

Jan 25 London

Jan 26 English Open

Jan 30 Hanley

Jan 31 Newcastle

Feb 1 Bishop Auck

Feb 2 Carlisle

Feb 3 Barrow

Feb 6 Leeds

Feb 7 Bury

Feb 8 Macclesfield

Feb 9 Stockport

Feb 10 Grimsby

Feb 11 Nottingham

Feb 13

Wolverhampton

Feb 14 Bolton

Feb 15 Liverpool

Feb 16 Ellesmere Port

Feb 17-18 West of England tournament

Feb 20 Exmouth

Feb 21 Plymouth

Feb 22 Birmingham: Czechoslovakia vs. England

Feb 23 London

Feb 25 Perivale oops wrong countries!

Feb 24 Woolwich

A sample headline from the tour:

Was it just chance that the Jaguar ad highlighted “exhilarating performance,” too? The Bergmann/Vana match was the grand finale of each exhibition evening. In results we could find, Bergmann beat Vana in eight of 11 matches.

Since his loss to Vana in the finals of the 1938 Worlds, -20, 9, 16, 4, Bergmann had been devoting much thought to strategy. “Before the tour began,” wrote English international Stanley Proffitt in the Daily Herald, “he told me he had a plan to beat Vana, who was the only player he feared, and that he would put it into operation as frequently as possible in order to undermine the champion’s confidence.”

Proffitt was writing on January 24, right before the English Open, where the rivals met in the final. “It was a brilliant match,” wrote one reporter. “At first Vana hit through him with those terrible whipped forehand drives which have to be seen to be believed, and when the Czech took the first two games he looked a certain victor. Then Bergmann’s defence took charge. He got everything back, some of his retrieving being from impossible angles. His own attack also shone. Gradually he wore Vana down to march to a great win.” Wrote another observer, “Vana won his world title by forcing Bergmann from the table with terrific forehand drives, then scoring with drop shots, but this time Bergmann refused to be forced back; indeed, he took the attack oftener than Vana.” A third said, “Bergmann, usually a defensive player, hit like fury...” He won -18, -19, 17, 8, 14.

What did Bergmann himself have to say? From his book TwentyOne Up, page 65: “Despite a good lead in each of the first two games, I lost them both by defending and using my bat halfheartedly. At this stage I made a drastic decision, and as it was clearly a case of either win or bust, I determined to switch

completely and hit everything all the time. I went fighting mad and the onslaught proved too much for Vana ... Nobody had expected that I would dare use an attack which I had developed only tentatively in the course of one short year. Bohu Vana may have been overconfident and, despite his exhibition losses, put too much trust in his lucky star; yet my whirlwind attack on both wings must have been something out of the ordinary, for even Barna admitted afterward that he had never seen anything like it.”

Bergmann also beat Vana at the two other tournaments these tourists entered.

Bergmann had winning exhibition records versus the other two players, too, at least among results we could find. He was 6-3 versus Barna and 7-2 versus Bellak. Vana was 5-3 versus Barna and 7-1 versus Bellak. Barna was 9-1 versus Bellak.

Bellak was frustrated with his results, according to Bergmann’s book, and once smashed his bat and trashed the dressing room after yet another loss to Barna. Yes, the players did take the exhibition matches seriously. They commonly bet on themselves, which certainly increased incentives. True, they would sometimes agree in advance that whoever won the first game would lose the second, just to keep things exciting, but the third game would then be mightily fought.

Rivalries were keenly felt. As Bergmann tells it, “We even vied with each other on matters of everyday routine. I would consider it satisfactory to outwit the great Victor Barna, who regarded the front seat of our driver’s Humber as his private property, but on occasion found it occupied by little Richard much to his annoyance.”

The packed match schedule must have become one big blur for them, together with the receptions, factory tours and community center speeches. In the photo below, Bergmann doesn’t look pleased to be there while Barna and Bellak somehow escaped.

Not surprisingly, Bergmann looked for ways to break up the routine. He took delight in throwing Vana off balance, even away from the table. Vana’s English was not good, but as world champion he believed he deserved prime speechmaking honors at public occasions. So the other three wrote a very short thankyou speech for him to memorize. From Bergmann’s book: “One fine day I had an itch and said his speech for him, before he had a chance to rise. That left poor Bohu stone cold and when pressed, he airily declined the honour waving his hand wildly about instead.”

Here are photos from Plymouth, a typical stop on the tour except that the top English players Adrian Haydon and Hymie Lurie joined them. Bellak must have been out exploring the town when this photo was taken.

The next day brought a long trek to Birmingham at least for Vana and Lurie where they staged an England vs. Czecho-Slovakia match. The Czechs beat England 6-3.

At the World Championships two weeks later, the teams met again. This time Hamr took Loewy’s place and won both his matches. The Czechs won 5-1, their only loss being an upset of Vana by Hyde:

By the way, Lurie won a bronze in men’s doubles at those Worlds for a second straight year. His partner in 1938 was Eric Filby; in 1939, Ken Hyde. Oh, and Bergmann beat Vana in the singles semifinals, 13, 20, -15, -15, 19, and then Alojzy Ehrlich 3-0 in the final.

Part Five, Issues 66 thru 75

We continue our analysis of the 101 issues of Table Tennis Collector/Table Tennis History Journal. Those issues can be viewed at https://www.ittf.com/history/documents/journals/.

Issue 66 ***Page 5. The Mystery Photo (right) was a stumper. The solution provided in the next issue was wrong, except that it correctly named one player, Fred Perry. See page 27 of this issue for the story.

Issue 66 ***Page 8. “The Official Organ” reported that some past issues of the official English TTA publication, dating as far back as 1935, were now available online. Update: All issues are now online, 1935-2010, along with the unofficial publication Table Tennis Review (1946-1955), individually searchable, at https://archive.tabletennisengland.co.uk/, thanks to our English colleague Graham Frankel. This is a very important history research source. We have been pushing to establish a similar resource in the U.S., even offering financial assistance, but so far without success.

Issue 66 ***Page 25. Gerald Gurney explains how he aided the production of “Edwardian Country House,” a reality series that aired in 2002 on BBC in the UK and then in 2003 as “Manor House” on PBS in the U.S. The show enlisted volunteers to go back in time to 1905, living as the original inhabitants did. Six people are given the roles of the upstairs family, while 15 are servants. The photo at left is from the 25 seconds of table tennis: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ILfXMhFNE7c&t=1710s

Issue 66 ***Page 27. Displays 1901 articles about the important Queen’s Hall Ping Pong tournament. Fourth place among women was Mrs. C.S. Marsland, age 28 or 29. Many years later, she made an appearance at the English Open, as reported in Table Tennis Review, March 1949: “An interested spectator at Paddington one afternoon was 76-year-old Mrs. Marsland, who claims to have been finalist in the 1901 English Championships staged at the Albert Hall [a mistake it was Queen’s Hall, and it was not the English Championships]. She used to play with a banjo-type vellum racket and after watching some of the present-day players her only comment was that we had taken up the game where they left off.”

Issue 67 ***Page 3. A tribute to the late Helen Elliot of Scotland mistakenly states that her world women’s doubles title with Beregi was in 1949; it was 1950. It also provides a link to an incorrect Pathe video. But the link on the same page for Marty Reisman (USA), who had also recently died, features both Elliot and Reisman at the 1949 English Open: http://www.britishpathe.com/video/table-tennis-crown-is-won-byamerica. That video also shows the iconic Arnold “Ping Pong” Parker (left) awarding the singles trophy to Peggy McLean (USA), who beat Elliot in the final, 46 years after Parker’s own important victory.

Issue 67 ***Page 5. Presents two more Mystery Photos. The solutions were never given, so here they are. The first (right) showed English team member Eric Findon and the great French tennis star Suzanne Lenglen. The photo was published Dec. 2, 1933, at the start of the world table tennis championships in Paris. In this issue, see page 28 for more about Findon’s short, action-filled life. Also see page 33 to learn about Lenglen’s several ties to table tennis.

The other Mystery Photo (left) showed the great track star Jesse Owens.

Issue 67 ***Page 18. Discusses the earliest English/UK championships in 1902-04. On page 34 of this issue, we look at the participation of the top lawn tennis players at these table tennis tournaments.

Issue 68 ***Page 7. Reprints a February 1902 Kent Times article that states that T.H. Oyler played table tennis 12 years earlier with vellum battledores and cork balls at Canterbury. Update: We have found a letter that Oyler wrote soon after to a different local newspaper (Kentish Express, March 1, 1902), stating that “ten years ago” he played table tennis with “one of the inventors” of table tennis, who was a top cricketer for Cambridge and Kent (right). That is additional evidence to support the belief of our English colleague Alan Duke in Issue 69, page 12, that Vivian P. Johnstone was an 1888 inventor of table tennis, given Johnstone’s known athletic history. There is an unrelated twist. Oyler wrote the letter (and another two weeks earlier) in response to this Feb. 8 item: “In righteous indignation a correspondent asks me ‘What are Men of Kent doing? Playing ping-pong. I was at Maidstone today and actually saw young, well-knit fellows playing this effeminate game and I do not believe one in ten could fire a rifle. No wonder that England is degenerating. These young swells ought to be made to take off their acres of collars and cuffs and do a couple of years’ service in the ranks of the army.’”

If that sounds vaguely familiar, it’s because our September 2024 article “Real Men Shoot Rifles” showed a very similar letter. That one, though, was from the Feb. 22 Guernsey Press, quite a distance from Kent. While newspapers commonly copied articles from one another, copying letters to the editor shamelessly/shamefully enters fake-news territory. Similar letters were also published in the Tonbridge Free Press of Feb. 15 and the Bexhill-on-Sea Chronicle of March 1. Details were changed, such as the location of course, but favorite phrases such as “effeminate game,”“well-knit fellows,” and “acres of collars and cuffs” were retained. Publishers wanted to ignite a controversy. Responses, such as Oyler’s, were authentic, as were the two letters from the original Kent correspondent, who was soon revealed to be military man Archibald Mortimer.

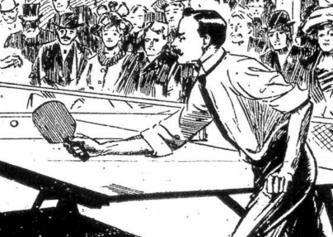

Issues 68 ***Page 24. Provides “proof” that this Table Tennis game (below) dates to the 1902 era, citing the clothing and the service rules.

This is simply wrong. First, the clothing, hairstyles, activity and typeface point clearly to circa 1920 or later Second, the service rules are consistent with this later era Third, proof is found in the lower right corner of the box lid: “HPG&S LTD. LONDON E.C.1.” Harry Gibson founded H.P. Gibson & Sons in 1919, and the postal code E.C.1 did not exist until 1917. (By the way, in 1921 Gibson produced a table badminton game called Zing-Zang.)

Issue 69 ***Page 18. Declares that the Bristol league in England is the world’s oldest continuous table tennis league. Unfortunately, the analysis was flawed. See page 42 in this issue for the facts.

Issue 71 ***Page 5. An article about a 1902 ping pong school includes a photo of the teacher and student. For more photos of this school, see page 47 in this issue.

Issue 71 ***Page 15. Gerald Gurney hosts a TV antiques show at his home, displaying his racket sports collection. For photos and details, see page 26

Issue 71 ***Page 25. Shows this silver-plated mahogany bat. This had earlier been shown in TTC 69, page 31, described as fetching 1150 pounds at an auction. (Actual hammer price: 1100 pounds.) TTC 71 tells us that the shield inscription reads, “DOSH, XMAS, 1902.,” and that the bat has a retailer’s mark for 512 Oxford Street [London]. It failed to note that this was the address of Hamley’s Toy Warehouse, owner of the Ping Pong trademark. Also not mentioned was that the words “Ping Pong Challenge” were somewhere on the bat, according to the 2013 Graham Budd auction catalog.

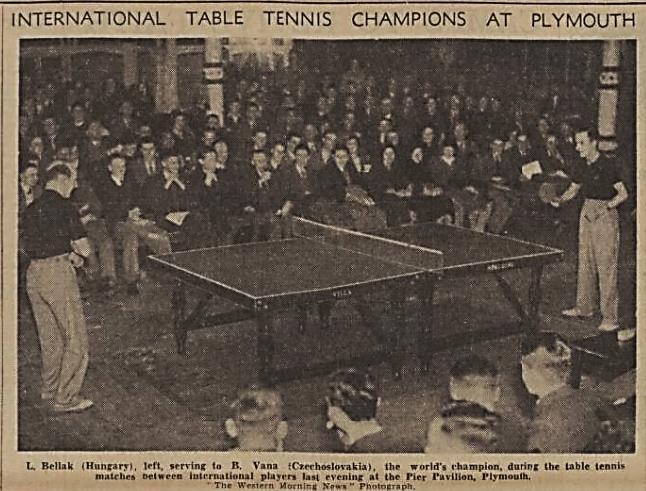

Issue 72 ***Page 55. Cor du Buy blades pictured various players and coaches in the 1960s and ‘70s. Shows this example (near right) and wonders who Dusan Tigerman is. Born in 1933 in Ljubljana, Yugoslavia, he was known as Dusco and played for the top Slovenia table tennis team. In the 1960s he became a coach, and in 1968 moved to Netherlands to coach their national team, soon replacing Cor du Buy. In 1972 his book Table Tennis Stroke by Stroke was published in Dutch. He is shown at left in 1973. A Tigerman bat in TTC 77 (far right) sold for 67 pounds; the other example, 102 pounds.

Issue 72 ***Page 56. Our colleague Laszlo Polgar’s new book about Victor Barna is announced. The heading at right translates Viktor Barna/My Career; Laszlo Polgar/From Young Braun to Adult Barna. Written in Hungarian, the book’s 700+ pages include over 250 pages of photos Volume I is a biography that opens with a 128page autobiographical manuscript by Barna. Volume II ties the world of Barna and table tennis to the world of chess and Polgar’s invention, Starchess. Polgar is known for his education theories and many chess books, and he and his wife raised three top female chess players. Indeed, Judit was one of the top chess players in the world, male or female. When young, they played in table tennis tournaments, too:

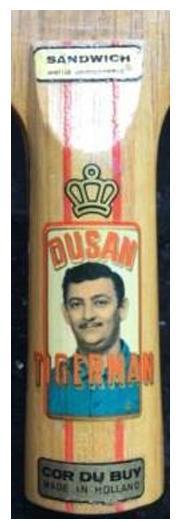

Issue 74 ***Page 6. ITTF Museum curator Chuck Hoey reveals his want list of photos of celebrities playing table tennis (below). The first two on the list are still elusive, but retired English football star David Beckham obliged us a year later, in 2015, when he visited Nepal in a campaign for UNICEF even if he had to use bricks for a net.

Chuck's Want List

Issue 74 ***Page 14. Shows a London exhibition program from Feb. 23, 1939, which included a photo of the four stars Bergmann, Vana, Bellak, Barna (right). The editor says he would love to know the scores, But this meeting was just the tip of a 30-city iceberg. See the full story on page 10 of this issue.

Issue 74 ***Page 16. Shows an unusual 1936 rubber-covered bat (below) and wonders if this could herald future sponge bats. Fails to mention that the ad itself offers a sponge backing option (for an extra shilling), which we circle below. This is the earliest-known commercial sponge/rubber sandwich bat, twenty years before they became popular.

The 1935 patent for the bat makes no mention of sponge:

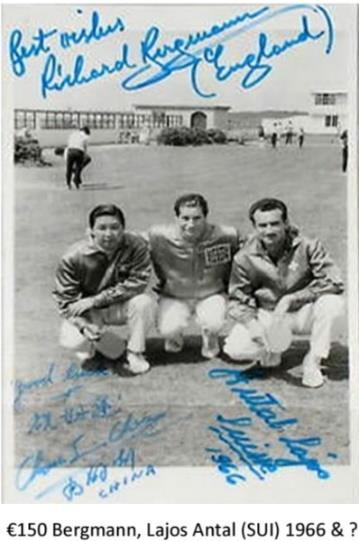

Issue 74 ***Page 43. Shows an autographed card (right) but is unable to identify the player on the left. That is Chou Lin Chen of Taiwan, who appeared in our September 2024 issue as one of Bergmann’s Globetrotters partners.

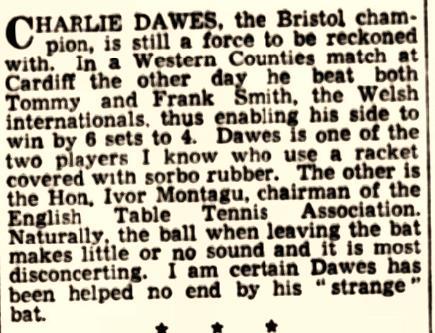

Issue 75 ***Page 12. “The 1950s Arms Race” provides a deep look at the sponge controversy of that decade. Examples were given of sponge use prior to the 1952 Satoh upheaval, by Ivor Montagu and others. Charlie Dawes was one example; here is added detail about him from a Daily News reporter in January 1939:

Another example given in the TTC article was Austrian Waldemar Fritsch (left), who had success with black sponge at the 1951 Worlds.

Two early sponge users were not mentioned in the TTC article: At England’s Hampshire Open, according to Table Tennis magazine, Feb. 1939, “The women’s singles final was between two exponents of sponge rubber bats and proved to be of little interest. Miss D. Boddie (Portsmouth) was the winner, and she beat Mrs. I. Enticott (Southampton) by 21-18, 21-7.” Richard Bergmann, who won the men’s title, wrote in his book: “The tournament is noteworthy mainly through the contribution of one of the lady competitors who used a sponge rubber bat, a remarkable contraption which combined shock-absorbing qualities with absolute silence. I don’t know about it being anti-magnetic or telling the time, but the opponents’‘pings’ sounded awfully lonely.”

From Table Tennis, March 1939: Iris Enticott “has a bat covered with sponge with which she wipes out many good opponents.” A few weeks later, she won her fourth straight Southampton championship. She is shown at right receiving the 1938 trophy from the mayor of Southampton.

This was one of the “Controversies” discussed in our last issue:

We have since dug deeper:

Let’s start by saying there was important recent history between Japan and Vietnam. At the Asian Games of May 1958, Japan was a heavy favorite to take the table tennis team event. Ichiro Ogimura and Toshiaki Tanaka had for years been the top players in the world, having split between them the four world singles championships from 1954 to 1957.

True to form, Ogimura swept all three of his matches against the strong Vietnam team. That included a 2-1 victory over Le Van Tiet, the 18-year-old who had won all 14 of his other team matches. But reigning world champion Tanaka lost all three of his matches, and Tsunoda lost his two, so Vietnam pulled off a 5-3 upset for the gold medal. Understand how mightily this earthquake shook Japan. The 3,000 Tokyo Sports Center spectators sat in silent pain. It was said that Tanaka, 23, cried at 1958 Asian Games

his mother’s feet in the stands. The crown prince was supposed to appear at the awards ceremony but stayed home in grief.

Ten months later at Dortmund, March 1959, Japan and Vietnam met again, two unbeaten teams in the Swaythling semifinal. Vietnam’s lineup was identical to its Asian Games roster, but for Japan only Ogimura remained. (World champion Tanaka did not make the team.) The teams split the first six matches, including a bad loss by Ogimura,15, -6, to Mai Van Hoa, whom Ogi had beaten 2-1 at the Asian Games.

Could the teenager Le Van Tiet (right), now more experienced, also reverse his Asian Games loss to Ogimura? Accounts vary as to whether Ogi was up 20-17 or 20-18 in Game 1, but one thing is clear: He killed the ball for what he thought was the winning point. In doing so, though, he partially rolled onto the table. The umpire said he thereby moved the table and awarded the point to Le Van Tiet. (Some claimed that Ogi also put his left hand on the table.) Ogi and the Japanese team howled. The referee, Ossi Bruckner of Germany, entered the scene and overruled the umpire, awarding the game to Ogi. Now the Vietnamese howled. They refused to play on. A big crowd gathered officials, players, interpreters, journalists, photographers. Spectators hooted and performed a slow clap: Watching a 40-minute argument was not what they came for.

Finally, ITTF president Ivor Montagu brought the two captains together and told them: You may or may not like the umpire’s call, and the call may be wrong or right, but it cannot be overruled. Point was awarded to Le Van Tiet, who then deuced the game, but Ogi won 22-20.

1959 World Championships Semifinal JAPAN 5, VIETNAM 3

Soon after the start of Game 2, the umpire was replaced. Later in the game, Ogi again did his kill/ roll thing and the new umpire gave another point to Le Van Tiet. This time the umpire calmly waved off the Japanese protest and play continued. Ogi won the game anyway, 21-19, and Japan went on to take the match 5-3, finally getting revenge for the Asian Games loss. Teruo Murakami was the hero, winning all three of his matches in straight games (scores at left).

Murakami beat Mai Van Hoa 14, 17

Hoshino lost to Le Van Tiet -18, 11, -12

Ogimura beat Tran Canh Duoc 15, 18

Murakami beat Le Van Tiet 18, 19

Ogimura lost to Mai Van Hoa -15, -6

Hoshino lost to Tran Canh Duoc -14, -20

Ogimura beat Le Van Tiet 20, 19

Murakkami beat Tran Canh Duoc 8, 6

Two weeks later, in the French Open final, it looked like Murakami would easily score another win over Le Van Tiet when he won the first two games at 17 and 13. But Tiet, seeded only 16th, won the championship by taking the last three games 16, 12, 16.

Toshiaki Tanaka won his second singles world championship in 1957 at the age of only 22. Why did he never play again in this event? Zdenko Uzorinac’s history book called it a mystery, adding that Tanaka was a withdrawn, serious person who attempted suicide in February 1960 because of unrequited love.

We turned to our colleague in Japan, the journalist Ito Jota, and he kindly provided the following: In the 1950s, there were no professional table tennis players in Japan, so most of the top players who played in the World Championships were university students. They practiced 8 to 10 hours a day to become top-level players. After graduating from university, though, even world champions could not make a living playing table tennis, so they had to find a regular paying job. Naturally, they cannot maintain the amount of practice, so their ability declines.

Tanaka graduated from Nihon University in Tokyo in March 1957 and went to work for a steel company called Yahata Seitetsu in Fukuoka, in the far south,1000 km from Tokyo. It was 34 hours by train in those days, and his home town Hokkaido was in the opposite end of Japan, the far north. The attraction was that Yahata Seitetsu was focusing on table tennis as a corporate sport and actively recruiting strong players. Tanaka was able to find some good practice partners and competition. For example, Goro Shibutani, who won the 1959 All-Japan championship, joined Yahata Seitetsu the following year. Still, Tanaka had to devote many hours to his day job, and this took away from practice time. After winning the All-Japan in 1954, ‘55 and ‘56, he was only top 4 in November 1957, no better than top 16 in November 1958, and top 8 in December 1959. As seen in the preceding article, his May 1958 Asian Games performance was also disappointing. (Three decades later, Tanaka returned to table tennis to captain the Japanese team at the world championships.)

One other Japanese world champion did not defend her second title: Kimiyo Matsuzaki (right), who won world singles in 1959 and 1963. She had never planned to play internationally beyond the 1963 world championships, and winning the world title again at age 24 did not change her mind. The necessary many hours of hard practice was just not something she wanted to do forever. Also, she had undiagnosed health problems, later found to be a kidney malady.

The table below shows what an extraordinary athlete Ichiro Ogimura was. He graduated from Nihon University (same as Tanaka) in March 1955 and joined a company in Tokyo. He probably maintained his practice hours and ability through natural negotiating skills and thick skin, and won his second world singles title in 1956. He would use any means to achieve his goals. At the time of Ogimura’s playing retirement a decade later, there were no Japanese professional coaches, so his subsequent coaching activities were also unusual.

“Celebrity Antiques Road Trip” is a BBC series of over 200 episodes that has run since 2011. In TT Collector 71, page 15, Gerald Gurney briefly discussed his appearance on a 2013 episode. We were recently able to view this Season 3, Episode 4, on the Pluto channel. It is also available to PBS members and perhaps on BBC or other sources.

The Gurney piece runs for nearly six minutes, starting at about the 34minute mark when guest celebrity Simon Williams and antiques expert James Lewis pull into the Gurney driveway in Great Bromley. Williams is a British actor best known for his role as James Bellamy on “Upstairs Downstairs” 50 years ago.

Gurney shows his guests around the large room filled with tennis and table tennis memorabilia. One display features Fred Perry, and the guests are surprised to learn that Perry was a world table tennis champion. Examining a trophy Perry received for that (pictured), Williams asks its value, but neither Gurney (above right) nor Lewis are willing to hazard an answer.

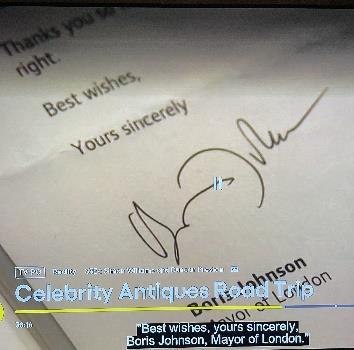

Another topic was Boris Johnson’s 2008 statement that Whiff Waff was the first commercial table tennis, rather than the much earlier Gossima. Gurney wrote Johnson to correct him. In response, on mayoral stationery, Johnson wrote, “Thank you so much for your letter about Ping Pong/Whiff Waff. I know I am right.” (Right.)

For unstated reasons, part of the central display table was covered.

The Mystery Photo in TT Collector 66 (right) remained a mystery for longer than usual. The solution provided in TTC 67 was wrong, stating that this was Fred Perry and Adrian Haydon at the 1929 World Championships in Budapest. The Hungarians could conceivably post a sign in the English language stating “Private; Press Only,” as seen in the left background. But it is unlikely that lefthander Haydon would be playing with his right hand.

Then in TTC 68, page 2, the issue introduction states: “Alan Duke (ENG) sends a fine vintage photo [left, from page 10 of that issue] that sheds some light on a previous Mystery Photo.” Actually, a LOT of light! It showed that the confidently stated solution had simply been wrong, yet this was not acknowledged.

The five players representing England that went to the 1932 world championships in Prague were Charlie Bull, Adrian Haydon, David Jones, Andrew Millar and Edward Rimer. That appears to be Bull in the top photo, back to camera, playing against Perry.

Here is another photo from the event, players unidentified:

He was an excellent table tennis player but no more accomplished than hundreds of others who do not merit a five-page article. Eric Charles Findon (1913-1941), however, led a multifaceted, action-filled life in London. He was a keen promoter of the sport. Meanwhile, he turned another kind of playing acting into a fulfilling second career, in keeping with his Gilbert & Sullivan bloodline. Findon made the news as a daredevil, too. And then there was his patriotic third career.

Let’s start with the

Findon was only 18 when he published the first issue of Table Tennis World magazine in 1931, which lasted for 21 issues, until 1933. He came from a publishing family, but even so that is strikingly young.

He represented England at the December 1933 World Championships in Paris, where he went 9-6 in Swaythling Cup matches. Findon made the round of 16 in both singles and doubles, and the quarterfinals in mixed doubles with Wendy Woodhead. He represented England against India in 1933, too, and Wales in 1934.

The years 1935 and 1936 saw Findon in exhibitions with the Hungarian stars (left) on their visits to England. His humor made him a crowd favorite, along with Laci Bellak. One article said, “In spite of the keenness of the game Findon yet found time to produce some of the amusing ‘parlour tricks’ for which he is famous.” He frequently fell into the crowd while retrieving hard-hit balls.

Spalding produced an Eric Findon bat in 1936.

He wrote coaching columns for Table Tennis magazine:

In the same issue was an ad for his exhibition squad:

... and an ad for his school:

Findon reviewed Montagu’s 1936 book.

He was one of the stars at Selfridge’s Autumn Sports Festival in September 1936.

Findon’s earliest known table tennis activity was at age 15, during his

He played table tennis with fellow cast members while filming The Rising Generation, a nowlost 1928 comedy silent. One of those actors happened to be Betty Nuthall, 17, a top tennis star and avid table tennis player. The article at left is from the Sunday Dispatch in July 1928, when Findon may have been a novice at table tennis. Perhaps his love of the game got its first spark from these encounters.

(Right) Betty Nuthall during a tennis tournament rain delay in September 1927

Reviews of Findon’s first stage role:

Era, January 19, 1927

Table tennis was not listed among August 1928 athletic interests.

His film career did not advance far for whatever reason perhaps the crossover from silents to sound or from youth to manhood? But Findon worked in theater throughout the 1930s. In 1939 he even had his own repertory company. Theater ran deep in

shared with Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900) of Gilbert & Sullivan fame. Eric’s grandfather and grandmother were each a first cousin of Sullivan, though not blood relations of each other. The grandfather, Benjamin William “B.W.” Findon (1859-1943), was Sullivan’s close friend and most adulatory biographer. B.W. was a prominent drama and music critic, editor of The Play Pictorial for over 30 years, songwriter, organist, lecturer, playwright and poet. In the First World War, he was an Honorary Lt. (right) and took hundreds of wounded soldiers to matinee and tea.

Eric’s father Arthur C. Findon (1887-1957) therefore had a double-dose of Sullivan cousin blood. Arthur was a lyricist and a leading film critic, and also had a long on-and-off career of publishing Competitors’ Journal and similar magazines for contest entrants. His grandson Ben Findon (Eric’s nephew) was a successful songwriter/producer for Billy Ocean and others, beginning in the 1960s.

In 1915 Arthur was arrested on a minor charge associated with antiGerman riots in London. In 1917 he enlisted in the Royal Air Force.

Eric followed in his father’s footsteps in 1940-41, his year of RAF Service

The theater world did its best to ignore the war, and Findon’s newlywed bride Edith continued her show career in 1941, as seen below. The Air Raid note is from the program of that show:

In August 1941, Findon co-piloted a mission to Dusseldorf, Germany. On the return, their plane was shot down over Belgium and all five aboard perished.

In his book Richard Bergmann called Findon “an intelligent daredevil with a forceful personality.” “Daredevil” aptly describes Findon’s newsmaking 1936 failed attempt to cross the English Channel in a collapsible canoe (left).

Bergmann added, “The sport of Table Tennis doubly deplores his death, as a fellow human being and as one of the solid pillars who would have loyally fostered and advanced the good cause.”

TT Collector 67 showed a Mystery Photo of Suzanne Lenglen of France at the ping pong table with England international Eric Findon (shown again on page 17 of this issue). Lenglen (18991938) was the top women’s tennis player in the world in the 1920s, and won Wimbledon singles five years in a row, 1919-1923.

Soon after she won the 1914 World Hard Court championship in Paris at age 15, Femina magazine did a long feature on her in the July 1 issue, including these photos of her and her father:

From the article (translated):

But the father's voice is heard:

Suzanne, it’s time for your ping-pong.

And Suzanne, in this miniature tennis, displays her usual talent. Mr. Lenglen explains to me: “Table tennis vs. tennis is comparable to the foil vs. the epee. Thanks to this practice, we maintain precision and wrist finesse. Just as after swordplay it is good to take the foil lesson to get back into position, get in line, correct any errors that may have been made in training and attack preparation, so the same after a day of tennis and intense action, it's good to come and calm your nerves with ping-pong. This game requires your head and judgment.”

In 1926 Lenglen made the surprising, controversial decision to turn professional. Her first pro job was to play public ping pong outdoors for a film scene (right). Her opponent was the comedian Biscot, and the film was Le P’tit Parigot.

England was the first country to organize national table tennis championships. The table below shows the initial champions, as published in TT Collector Issue 67, page 29. (After 1904, the next truly national tournament was not until 1922.)

(Comments and additions:

1. The first championship, which had almost 300 entrants, included a Mixed Singles event shared by both men and women. That event’s omission from the table makes sense, given that player interest was disappointingly low, especially among women, and that the event was never held again. For the record, the winner was C.W. Vining (who also made the semifinals of Men’s Singles) over Mr. M. Said in the final, 20-13, 20-12. We discussed Vining and this event in our January 2024 issue, page 20.

2. The first championship shows the first two Women’s games as 19-20 and 20-19. The actual scores were 21-22 and 22-21. Under the rules, when the score got to 19-all, they played a best three points out of five, another way of saying that the first player to 22 wins.

3. In the 1903 tournament, the Men’s score was 30-22, 30-29. The Women’s was 30-20, 23-30, 3024. Sporting Life, March 2, 1903.

4. The 1904 Women’s winner is listed as Gladys Taylor, but this was a guess. The newspapers gave her name only as Miss Taylor of the Crystal Palace Club. A better guess is Alice Taylor, who won two major London tournaments in 1903 when she was “about 16.” Gladys Taylor had some tournament success in early 1902, when she was described as being about 14. We can’t rule out that they were one and the same person.)

Many early tournament players came from the world of tournament lawn tennis. They figured they would also be good at the small version, and usually they were, up to a point at least while table tennis was getting its footing and nobody yet had much experience. In this article, we take a look at the early champions who were also high-level lawn tennis players.

The first Men’s champion, George Greville (1868-1958), seen at right with his plain-wood homemade bat, was a half-volley defensive player. A few months later he made the Wimbledon singles quarterfinal for the third time. Greville competed at Wimbledon from 1896 to 1927, when at age 59 he was the George Greville

oldest men’s singles competitor ever. A banker, Greville was the son of a Rear Admiral and an heir of the Earls of Warwick. His Wimbledon record is at right.

Greville’s friend Harold Mahony, the 1896 Wimbledon champion who knocked out Greville in the 1899 Wimbledon quarterfinals, was on hand to watch him beat Arnold Parker in the table tennis final. Parker was not a lawn tennis player, but one Aquarium semifinalist, Brame Hillyard, made the singles quarterfinals at Wimbledon in 1903, his best result there in 15 appearances. In 1930, Hillyard was the first-ever player to wear shorts at Wimbledon.

The January Aquarium women’s finalists, Mrs. Garner and Miss Good, were not serious lawn tennis players.

The best lawn tennis player at the tournament was not even an entrant it was organizer/secretary/referee M.J.G. Ritchie (Major Josiah George Ritchie, 1870-1955). He coauthored a table tennis book and could play the game well. But lawn tennis was where Ritchie really shined. For years he was one of Wimbledon’s top players, as seen in this table, and he won gold, silver and bronze medals at the 1908 Olympics. He happened to be the son of Josiah Ritchie, the managing director and part owner of the tournament venue. When the Aquarium opened in 1876, it was intended as high brow with opera and art, but Josiah shifted the entertainment to circus and similar acts.

The next championships, in late 1902, were also at the Royal Aquarium. The Men’s titlist R.D. Ayling was a tournament tennis player but not high level. The Women’s winner was a different story. As shown below, Connie Wilson (1881-1955, later full married name Constance Mary Wilson Luard) made the Wimbledon singles final in both 1905 and 1907, losing each time to the great May Sutton (herself a table tennis champion in 1902 California; for details, see Ping Pong Fever: The Madness That Swept 1902 America, pp. 188-190).

23, 1907

In the table tennis final, Connie beat Ethel Reynolds, who was not a serious tennis player, though Ethel and her husband Dr. Bernard Gore Reynolds did belong to a tennis club. (They celebrated their golden wedding anniversary in 1949 and Ethel died in 1956, age 80, contrary to the belief stated in TTC 67 that she died in 1943.)

The 1903 championships, unlike the earlier versions, were organized by the Table Tennis Association and were for the UK title rather than simply England. They were held at Crystal Palace. (The Royal Aquarium had closed.) The Men’s finalists were not lawn tennis players. The Women’s winner Helen Madden, better known as Agnes, played occasional tennis tournaments but not at a high level. Runner-up Dora Boothby (1881-1970), though, was later a headline lawn tennis star. She won Wimbledon singles in 1909 and doubles in 1913, and did well in other years, too, as shown in the table below. In yet another sport badminton Dora won the 1909 national mixed doubles title. She was later known by her married name Geen (not Green as stated in TTC 67).

Finally, turning to the 1904 championships, none of the table tennis finalists were serious lawn tennis players, who by then had left the table to return to their first love. What remained were dedicated table tennis specialists who had grown more experienced and skilled.

Can one properly crown a national champion when half the country is excluded from the competition? Of course not.

Table Tennis Collector issues 67 and 80 boasted of the discovery of previously unknown Champions of England. These were undoubtedly top-notch players. But the competitions (these were not tournaments) fell well short of the truly national standard that would justify awarding the title of English champion. They would be better described as simply a long-term rivalry between two players.

We reproduce here the relevant part of the table published in TTC 80:

The two finalists were always the same: Midlands champ Tom Hollingsworth and North of England champ Andrew Donaldson. In 1921, Donaldson was not even the North champ but played Hollingsworth for the “title” anyway.

We needed to talk. The three of us Tom, Andy and I recently gathered for an illuminating discussion.

Me: Congratulations guys on your excellent table tennis careers! Please tell me how you got started in the sport.

Andy: I learned the game at school in the early years of the century and then played for a YMCA team. But I was only about 16 when the craze ended and table tennis activity in England became disappointingly sparse. I then devoted myself to my other two loves, rugby and cricket.

Tom: I essentially missed out on the early era. I was only about 11 when the craze ended.

Andy: I wanted to get back into table tennis, so in March 1910 I helped found the Sunderland Ping Pong Union. I won the Sunderland championship by final-round scores of 50-16 in 1910, 50-21 in 1911, 50-32 in 1912 and 50-26 in 1913, and indeed kept winning every year through 1917. I also won the North of England championship every year, which to be honest mostly meant beating the same Sunderland people, who did not offer me much competition.

Tom: In similar fashion, I was easily the Midland Counties champ in 1913. Each of us was so far ahead of local competition that we could give dozens of points in handicap contests and still win nearly all our matches. I used the penhold grip and, like Andy, I used a plain-wood bat.

Andy: We were able to build our Sunderland league up to as many as 18 teams, but this was quite the exception in 1913 England, and even at that the ability level was not high. I was quite keen to grow the sport and see it return to its earlier popularity across the country.

Me: Your league success was admirable. Did you do anything else to promote table tennis?

Andy: I did what I could. I wrote to numerous newspapers, giving them match results and letting them know the upcoming schedule. Our local Sunderland Echo published these items two or three times a week throughout the season. I even sent free tickets to newspaper columnists around the country and told them they could make a big difference in growing the sport. Unfortunately, we were too far from London and other major cities to get these writers interested.

Me: I see.

Andy: Also, I made myself available for matches or exhibitions at ping pong clubs in my area. At one club, I gave everyone 20 points in a game to 40 and beat all nine challengers. The Echo printed the scores I sent them, along with a similar match against my own Southwick Trinity teammates. [At right, from Feb. 7, 1913.]

Tom: Andy’s strong reputation was known to us in the Midlands, and naturally we wanted to play each other. For extra publicity, we decided we should call this the Championship of England.

Me: Was this officially sanctioned?

Tom: There was no national association at that time. It was just something we did on our own.

Me: Did you have any qualms about that? It must have felt strange to call this the national championship when half the country’s population was excluded outright. No London aces like the Bromfield brothers, for example. No James Thompson, the 1909 West of England champ who was quite active in 1913, when his YMCA team won the Bristol championship.

Andy: I’m sure it seems a bit odd to you. But we just wanted to maximize the publicity opportunity. Tom and I played one championship match in February 1913 and a second in October. Each time I sent the local news clippings to many newspapers to spread the word of Tom’s victories and his national title. I was

hoping to draw out top players from London and elsewhere, if any were still active. But nobody contacted us, and soon the War intervened anyway.

Me: I suppose one could say there was precedent. In 1902, those two supposed national championships at the Royal Aquarium were not sanctioned by either of the national associations.

Andy: Quite true. The Aquarium managing director Josiah Ritchie, together with his son the tennis star, labeled the tournaments national championships to attract more entrants and publicity. Players around the country had the opportunity to enter, but very few outside the London area chose to travel the distance.

Me: At least those two Aquarium tournaments were designed to be truly national and open, whereas your regional battles were not.

Tom: I have to agree.

Andy: My knowledge of those Aquarium tournaments comes from the brother of one of the champions. Rev. Leslie Vining played on the St. Gabriel’s Church team in our league in 1914. His brother Wilfred Vining won the Mixed Singles title in that first national championships in 1902 and made the semifinals of Men’s Singles. By the way, Wilfred became a groundbreaking pediatrician and was married to the sister of the famous Hollywood movie star Ronald Colman. Leslie later became the first Anglican archbishop of West Africa.

Me: Oh, very accomplished brothers.

Andy: Oh, I should also mention that in Sunderland we held the first-ever international table tennis match, England versus Scotland, on March 11, 1913. I was born in Scotland and lived there for the first few years of my life. So I represented Scotland, along with another Sunderland gentleman, while two other locals represented England.

Me: Sounds fun, though I don’t think we should officially count that as the first international. Moving ahead, when the war ended, you started up again.

Andy: Yes, we reactivated the Sunderland Ping Pong Union in 1919. My handicap was again -30 in a game to 100, and it remained hard to find good competition. I was glad Tom agreed to a rematch in March 1920.

Tom: This time Andy gave me the toughest fight yet, but I eked out a 200-195 win. But then in 1921 Andy took the title from me.

Me: That title was supposedly the English national championship, but again it was really a regional competition, wasn’t it?

Andy: True, true, but we felt there was no harm in calling it the national championship. Believe me, it was not for the glory. Ha! In those days, if you told people you were a ping pong champ,

they would just laugh or give you a strange look. We just felt this was a way to gain publicity for our great sport, maybe one more step to get people to take it seriously.

Me: Pardon me for saying that your 1921 match was not even between the two regional champions. Two weeks earlier, Andy, you lost the North of England championship to a fellow Southwick player, David Woodward, the man you beat in the previous year’s final.

Andy: You are correct. Woody couldn’t make it to the match with Tom for some reason, so I made the trip.

Tom: Things did finally take a positive turn in 1921-22 with the creation of a national association, and at last there was an officially sanctioned English national championship. I’m pleased to say that Andy won that, demonstrating that we really were playing at a top level in our regional contests. [From a newspaper account of the semifinal: “In the first two games Bromfield’s attacking shots were little short of marvellous, but Donaldson gradually got the measure of his opponent, and his wonderful defence enabled him to win.”] Both of us soon joined other top English players in international competition, too.

Me: Congratulations again to each of you. Thank you for candidly sharing this history with our readers.

Andy Donaldson, a schoolteacher, did a great deal to promote school table tennis (as well as rugby) and was named a vice president of the English TTA in 1935. He returned to Sunderland league play in the early 1930s, when he was well over 40 and again one of the top players. At right, the Sunderland mayor and Andy celebrate the league’s 50th anniversary in 1960. The league is still thriving today.

Tom Hollingsworth became a leader in Wednesbury government and was named mayor in 1944. Later that year he suffered the loss of his first-born son Tom in the war. In 1946 he went to the cinema to view the popular new film about his son’s last battle, Theirs is the Glory, which weaved actual scenes into re-creations. He was shocked to see his son in the film (below). The scene was two or three seconds long, at 11:47: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fiFeYxlPYy4

An article in TT Collector 69 carried the above headline. The analysis purported to show that the Bristol/Gloucestershire league in England is the oldest continuous table tennis league in the world, dating to 1902, ahead of Plymouth’s 1903.

Unfortunately, the analysis was faulty. The league dates to no earlier than 1906, as shown in the article at right.

The TTC article declared that the formation of the Gloucestershire PPA in 1902 marked the initiation of a league, simply because certain teams within the GPPA district played each other. There was no evidence of any organized schedule, league standings or league champion, nor was the term “league” ever used in the many match newspaper reports in 1902 and 1903. But even if we accept this very loose defintion of a league, the 1906 article clearly shows that any previous league had ended.

The TTC article’s proof of continuity hung on a single slender thread, a league box score in January 1906 (right). But this is clearly a billiards box score, and indeed the full newspaper page reveals that it was part of a column of billiards scores.

Prior to 1906, the only true GPPA league existed from January to March 1904, as seen in newspaper accounts. Note that the article at left, from the January 7, 1904, Western Daily Press, refers to the “first League match.”

This leaves Plymouth as the claimant for oldest continuous league, dating to 1903. But wait, not so fast. Plymouth has a similar problem. Their 1903 league must have had a short life, because the Three Towns PP League was newly formed in 1905 (right).

Gloucestershire held a ping pong tournament in the spring of 1903 that included singles, doubles and club teams. Because there was no league, they used the team events to determine the top clubs.

Yet another example: The list provided in TTC 69 stated that the Luton league has been continuous since 1921. Then how explain these newspaper clippings from October 1925?:

Be skeptical of any league that claims to be continuous for very long periods. Proof is very difficult to come by, and few if any can offer it. Even the definition of continuity is itself unsatisfying because it allows indefinite exclusions for wartime.

Suggestion: Dial back on the continuity idea and be proud of any league that started in the early years and also exists today. Overlook missed years and restarts. Those 100-year anniversaries (coming up on 125 years for some) should still be celebrated. The Plymouth League did so in 2003, as detailed in TT Collector 32. That league and others are to be heartily congratulated.

Edited by Gwendolen Freeman, Published by Brewin Books (2003), 100 pages

Intriguing title. Our colleague Alan Duke of England took a look inside and provides the following, shedding light on United Kingdom daily life during the early ping pong craze:

These are edited extracts of diaries kept by Marjory Freeman when she was aged 16 to 19, covering the years 1901-03. It could be inferred from the title that the two subjects of the title were in some way related, but of course they are not (the craze came just a little too late for Victoria)! They are merely two of the many subjects covered in the diaries: Queen Victoria briefly as the early pages of the diary coincide with the death of the long-reigning monarch; and brief mentions towards the end of the book of ping-pong, occasionally sharing interesting details. On the book cover, Marjory is pictured on the left.

Here are the ‘ping-pong’ references, all from 1902:

[The first batch are from a visit to relatives in Dublin.]

January 25. But he [Willie Gerard] came back in the evening and played ping-pong with us.

January 26. We played ping-pong before tea.

January 27. Aunt Nell and Uncle Jim played ping-pong till nearly one o’clock [morning].

January 28 [Marjory’s 18th birthday]. In the evening we played ping-pong till past one o’clock.

January 29. Uncle Jim is very much taken with pingpong.

January 30. This morning Buz [her brother] sent Aunt Nell some verses composed by himself, and dedicated to her. They are called the “Ping-pong Ball” written after the style of the tin Gee-gee.

February 1. In the afternoon Aunt Nell and Uncle Jim went to see a ping-pong tournament.

February 2. Uncle Jim asked several men to come and play ping-pong. He put up a table in the empty room below, and had a fire lighted there.

February 5. Willie Gerard came to dinner and stayed till 9.30 in the evening. Mr. O’Brien came in the afternoon and they played ping-pong.

February 7. I cleaned and dusted the ping-pong room. … Willie Gerard came in the afternoon. He played ping-pong with Aunt Nell.

February 8. Willie Gerard came to play ping-pong with Aunt Nell. He has entered for the tournament which is to be on Tuesday next. When it grew too dark to play they came upstairs and sat talking.

February 9. Aunt Nell had a letter from Mums enclosing some more ping-pong ballads written by Buz. The one we like almost the best was “Mary had a little bat”.

February 10. Aunt Nell lit the fire in the ping-pong room. We were expecting Mr O’Brien to come and play, but he did not come till past five o’clock. Aunt Nell and I had a few games of ping-pong. I think I should play fairly with practice! Of course I have played so very little. … After tea Aunt Nell, Willie and Mr O’Brien went down and played ping-pong. Mr O’Brien is a nice little man. I played with him once. He won, of course.

February 11. Soon after dinner Willie and I went down to the ping-pong room where it was bitterly cold, and we spent some time playing games without counting and talking in brother and sister fashion. … There followed some more ping-pong with Aunt Nell. Soon after tea we went with Willie to the ping-pong tournament. It was in a small room of a church. There were only two tables, and it was very crowded. The playing was not good, but the girl who played against Aunt Nell was alright and she won. Willie was in the finals without having played at all because his partner [opponent] did not come. We got home about eleven o’clock.

February 12. It was nearly eight o’clock when Willie went to the pingpong tournament to play his final. … We found him looking rather blank as he had just been beaten. … He told us that the game was 14:20, they gave him an extra good man to play against.

[Back home in Surbiton, a London suburb ]

February 15. Pattie [sister] and I played ping-pong on the breakfast room table.

February 17. I played ping-pong with Diggs [brother] in the evening. Of course he won.

February 18. Lucy [future sister-in-law] came to tea. She tried ping-pong with me. I played with Diggs and won.

February 19. I played with Pattie. She plays better now.

February 24. Buz has made up another ping-pong verse. Dad has sold 147 wooden bats [in his fancy goods store].

February 26. We tried to teach Dad ping-pong but couldn’t.

April 25. Aunt Nell and Aunt Bird went to see some ping-pong at the club [possibly the tennis club, at Southall].

At left, Marjory, Buz and Pattie stand behind their parents.

Marjory later met her much older husband through the local Christian Science church. They had no children, leaving her free to care for her parents into the 1930s. Marjory lived into the 1960s.

In November the winning eBay bidder paid 880 pounds for this rather rare book, Ping Pong People. Raphael Tuck & Co. published it in London in 1902. We show the front and back covers and the first page of the diary. For more: TT Collector 37, page 11, displayed illustrations from Tuck’s 1903 calendar called Ping Pong Players, which repeated illustrations from this book.

From The Sketch, Dec. 11, 1901, during the Ping Pong craze in England:

Issue 71, page 5, of TT Collector explained an early 1902 scene at a London ping pong school. This page has additional photos of the school, with a continuous caption

[We asked Peter Bajusz to tell us about his new book The Stiga Collector’s Catalog and Price Guide and how it came about.]

I started to play table tennis in Hungary when I was 18 years old in 1997. It was too late a start to reach a high level, but it was enough to find out how wonderful is the world of table tennis. When I reached a decent level, I started to play with an old Hans Alser blade, because at that time almost every professional player used Stiga rackets. With no internet, no Tradera, no eBay, you can imagine how difficult it was to find proper vintage Stiga equipment at that time. If you found an old, repaired allround bat without decals (which today is worth almost nothing), you had to buy it immediately.

After 25 years of collecting, today I have more than 50 rare Stiga blades. Nowadays the situation is different, because you can find almost everything except the real rarities. The question is just the cost. But one thing did not change: You could not find comprehensive information about Stiga blades, except maybe piece by piece, not gathered in any one place. Information spread only from mouth to mouth. This was the reason I started to research this book three years ago. Finally, our newly published book has now changed this situation.

With the help of the Facebook group STIGA Blade Collectors, my colleagues and I attempted to collect information and photos of all blades produced by Stiga in each time period. Collectors around the globe helped us. After three long years we finally managed it, gathering more than 250 colourful Stiga photos.

Our book audience is not just the collectors, but every person interested in table tennis or beautiful antique materials. The book is organized into parts, by time period.

Stiga Table Tennis was founded in 1944 by Stig Hjelmquist (1911-1985) in Tranas, Sweden. This was the beginning of the Stiga golden age. The first section of the book covers the rackets from the earliest years up to 1970. These blades were produced with decals and had the same wood compositions. These are the most valuable items, and collectors are always searching for these rackets (such as the Tova, the Larsson, the Harangozo). At left are examples of this era from my collection.

Highest price I have seen: A Tova Stipancic blade sold for more than 2000 Euros on Tradera. An example is on top of the stack in the photo. There are five to ten blades in this rarest category; others include Harangozo, 1st edition Alser or Dolinar. In the book they are indicated with CP (collectors price).

After 1975 Stiga released several different blade compositions, and this caused a difficult task for us to collect every layer composition from every handle type. At that time almost every professional table tennis player used Stiga blades, because of its unique soft feeling. Stiga has always developed close associations with the great Swedish teams and has had an important relationship with the Chinese team since the 1990s.

Meanwhile, Bengt Andersson (1942-2024) started a table tennis company in Eskilstuna, Sweden. This was Banda, which became a very popular brand. Bengt and Stiga’s paths crossed in 1984, when Bengt acquired the table tennis division of Stiga, his biggest competitor. Then he continued to run the company under the name of Sweden Table Tennis AB. Bengt and family even changed their own name, from too-common Andersson to distinctive Bandstigen. This silver age went through 1993. At right are examples of this era in my collection.

Stiga then moved their factory from Tranas to Eskilstuna, where the headquarters remains today. The book covers items from this late era too, but of course not every blade, just the rarities.

You can take a look inside the book at Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lLhzRx-x-SE

Feedback has been excellent. Please place your order at https://www.stigacatalog.com

Thank you and welcome to your Stiga journey.

Even as a teenager, Marty Reisman loved the stage. Here, at age 19, he clicks his heels and bows, the matador after a bravura performance, having beaten Victor Barna for the 1949 English Open championship. Reisman would never again win such a prestigious tournament.