TABLE TENNIS HISTORY

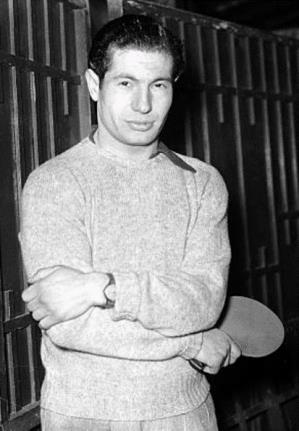

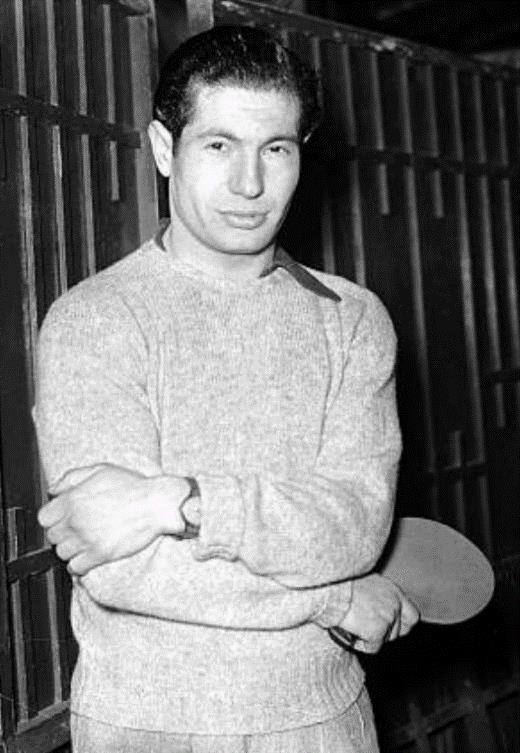

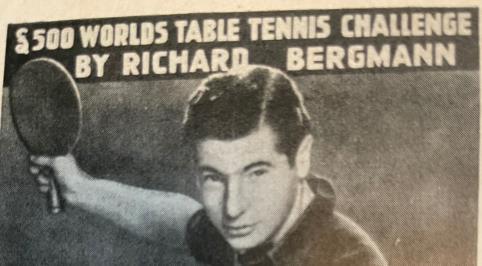

Richard Bergmann was 20 years old when he won his second world singles championship in 1939. He didn’t compete for the title again until he was 29, missing out on what should have been his prime years, age 21 to 28. In the span 1937 to 1950, he was in six worlds and won four of them. Bergmann was a great sportsman and a great fighter at the table, perhaps the greatest.

In this issue we set the record straight on three Bergmann matters: his £500 challenge, his famed 1948 world semifinal match and his birth year. If there were a theme to this issue (see also the Bromfield and 100 Issues articles), it would be, Nevertrustanythingyouread. This journal excluded, of course. (In that spirit, I have finally updated my ancient personal photo, unretouched).

As with our first issue, the core of this edition is the series “100 Issues: Updates, Expansions, Corrections,” examining the 30 years of TableTennis Collector/TableTennisHistoryJournal , 1993-2023. Where topics merit deeper exploration, we carve out separate articles.

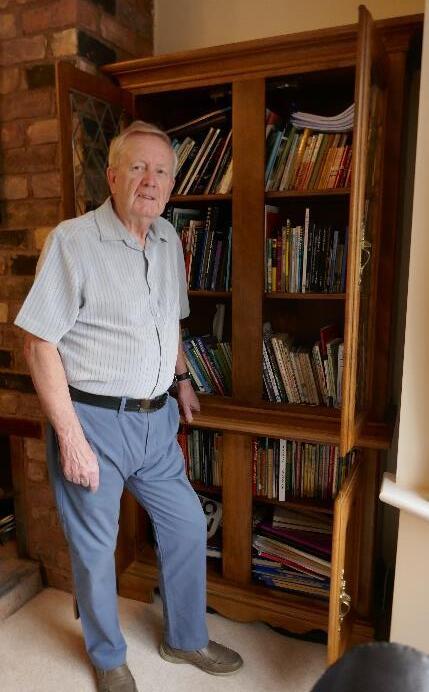

Plus we present another lover of table tennis. (In our first issue the lover was Fred Perry.) Barry Hayward player, coach, book expert extraordinaire writes for us about his English table tennis life from the 1960s onward and reveals his top-12 favorite table tennis books of all time.

And more...including the just-discovered 1932 Parker Cup of the controversial American Ping Pong Association.

I welcome comments and article contributions. Please spread the word about our journal by directing readers to https://pingpongfeverautho.wixsite.com/table-tennis-history

Grant

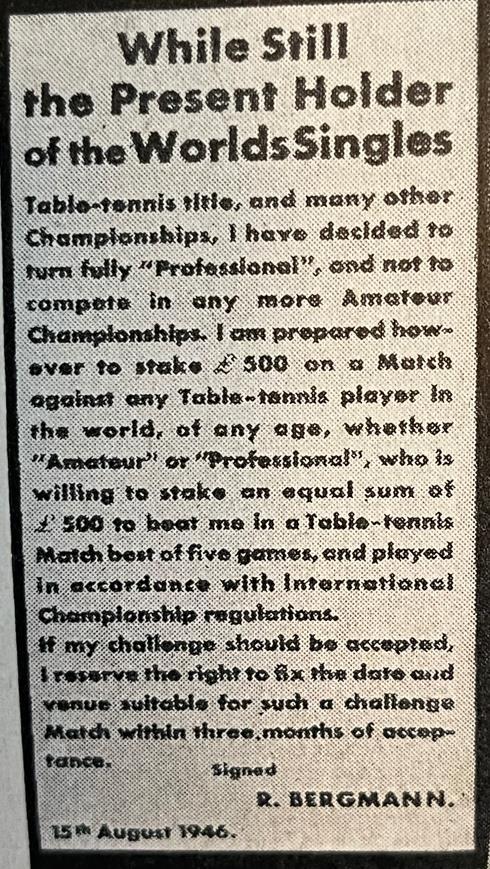

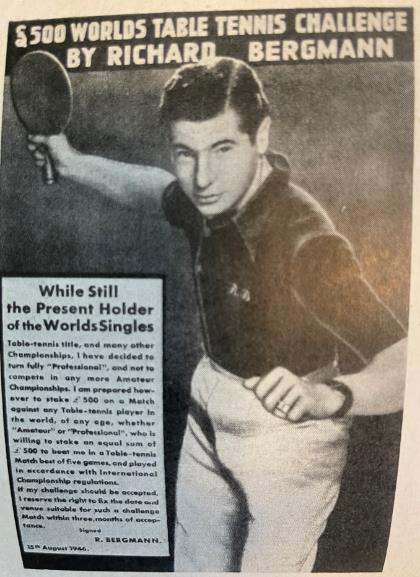

In 1946, Richard Bergmann issued a £500 challenge, offering to play a match against anyone who would put up the same amount (a lot in those days), winner take all. Numerous writers have since twisted this chapter into fiction that is not only wrong but sometimes unjust.

For example:

The 1997 book by former ITTF president H. Roy Evans, Around the World with Table Tennis is reviewed in TTC Issue 46, page 21. Chuck Hoey says his favorite story in the book is about Bergmann’s £500 challenge at the 1947 world championships in Paris. “Evans tells how Richard was denied the chance to defend his title, because of having played exhibitions at basketball halftimes on the Harlem Globetrotters tour.”

In truth, Bergmann was NOT denied the chance to defend his title; he simply chose not to. He was not suspended, and he may not have ever even heard of the Harlem Globetrotters basketball team at the time. It was not until 1954 that Bergmann first played in those halftime shows.

In TTC Issue 56, page 8, we are told Bergmann was not allowed to participate in the 1947 worlds “because during the war years he played exhibitions for money, without the required permissions.” This is repeated in Issues 73 and 100.

Wrong. The ETTA kept a tight leash on Bergmann beginning in 1938 and during the war years. “I was owned by them body and soul,” wrote Bergmann in his book Twenty-One Up. He was resentful at times, but as a refugee from Nazi-occupied Austria he was also grateful for their life-saving sponsorship. He toed the line. The ETTA paid him a modest stipend and set up exhibitions, a welcome fundraising source for the Red Cross in the early war years. And again, he WAS allowed to enter the 1947 worlds; he simply chose not to.

From Zdenko Uzorinac’s book ITTF 1926-2001 Table Tennis Legends:

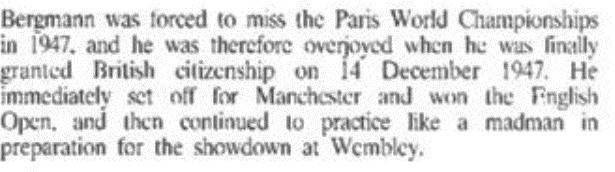

No, Bergmann was not “forced” to miss the 1947 worlds, nor did his citizenship status affect his ability to enter individual events.

Now for the real story, the full story. First, let’s go back to late 1943, early 1944, from his book

“I hatched out a scheme, nursed for some time and designed mainly to oust Victor Barna from his position as Public Idol No. 1. While, so I imagined, I was rapidly being forgotten as a mere obscure R.A.F. sergeant, Victor toured the country with his popular stage act, which, it would appear, could not exactly have been unprofitable. So I issued a challenge offering £1000 against £500 against any comer in a best of five match, winner take all. The idea was primarily conceived to lure and ensnare friend Victor... who, of course, did not accept, but for that matter neither did anybody else.”

Completely unmentioned in his book is that he first issued the challenge a year earlier, in late 1942, as reported for example by a newspaper in December 1942 in Portsmouth, where he was stationed. (He reported for RAF duty in April 1942.)

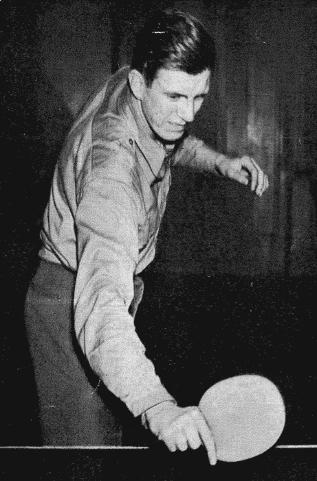

He IS able to set up a match on April 12, 1944, against the American Garrett Nash (left), who had been performing in many USO shows for the troops. Bergmann loses, 21-8 in the fifth. It is unclear what kind of money changed hands at the venue, London’s Queensberry Club. Certainly he did not have, had never had, anywhere near £500 to his name, though he says he did have a backer at times. Meanwhile, while raising a modest amount for Red Cross, the match raised a tidy sum for the American GIs betting against the British troops.

In his book, Bergmann writes that he is against gambling in table tennis, other than an occasional fun match for pocket change. Of course he had to write that because gambling can be grounds for ITTF suspension. His actions, though, may have been speaking a different language. Here is Marty Reisman, writing on page 60 of The Money Player not long after Bergmann’s death: “Bergmann was quite a gambler...” He then mentions two big money matches this Nash match and a $5000 bet versus Reisman himself in about 1967, when Bergmann would have been 48 or 49. That match, before a packed crowd in New York City, is detailed on Reisman’s page 240: “Bergmann was a little stockier ... but he looked pretty much the way he had” at the 1948 worlds, when he beat Reisman 3-2 in the round of 32 (not in the round of 16, as Reisman mistakenly writes elsewere in the book). “He was still in excellent condition and stood far away from the table, bird-

dogging returns. My game was the same too. I smashed everything I could,” winning 23-21 in the fifth.

In 1946, world championships are still not held, but Bergmann returns to major tournament play, winning the French Open. He makes the final of the English Open in March, losing 3-0 to his biggest rival, the Czech Bohumil Vana, seen here holding the trophy. Bergmann also made the final at the Wembley Open, losing deuce in the fifth to Johnny Leach. If he was not yet back at the top of his game, he was at least shedding wartime rustiness.

In July 1946, Bergmann’s active RAF service ended. From his book “Still not naturalized, in search of a plan in a broken world ... I performed for three weeks at Butlin’s Holiday Camps, but in my line of business it is a full-time job to keep the wolf away and I accepted with undignified haste when Alec Brook, English international and a great showman, asked if I would consider partnering him for a six weeks [exhibition] tour of Germany.”

In August 1946, “I re-issued my £500 challenge in six languages. A printing works in Germany supplied me with 5,000 posters and 20,000 leaflets. No one took the slightest notice of it.”

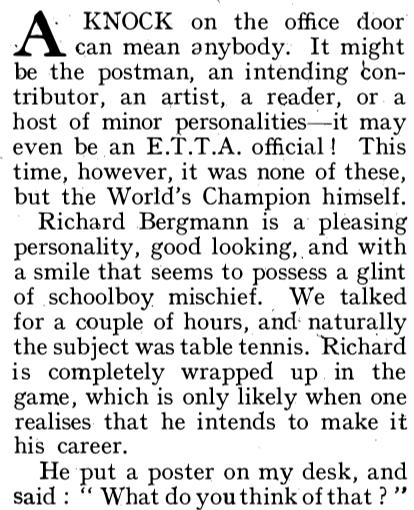

In October 1946, editor/publisher Arthur Waite writes in Table Tennis Review

Bergmann firmly believed that star players should be fairly compensated for the crowds they draw. From London’s Daily News, February 20, 1947

He continued to publicize his challenge in early 1947, after returning to London from yet another European military entertainment tour.

“Grimly sticking to the ‘Challenge’ plan, I refused point blank to enter any competitive Table Tennis and started a ferocious wholesale distribution of leaflets. Appropriately I gathered up two Salvation Army men and gave them ten shillings each in hard cash with stern instructions to stand outside the hall where the visiting Americans played an all-England team. This they did, in fact they stood nailed to the ground motionless and inanimate, like statues. Inside the crowded hall... I saw no one in possession of a pamphlet. Yet the challenge idea stirred up some dust and I fully intended to let the world know that I was very much alive and still kicking freely.

“Two days before the end of the Paris World Championships, I crossed the channel again... armed to the teeth with several thousand leaflets.” French Customs thought these multilanguage leaflets with German imprint rather suspicious, but finally let him through. In Paris, after a day-long search for distribution personnel, a bistro proprietor “put me onto four unwashed characters, who were prepared after lengthy negotiations, conducted on a very high level, to take over the job of distributing the leaflets outside the hall. I gave each man 1,500 copies and for fully 40 minutes they actually contrived to give them away. I left them with their task to have a look at the progress of the championships and my campaign inside. When I returned the men had vanished. A cadaverous elderly bystander, half-choking with laughter,

and whom I could really have murdered in cold blood, told me splutteringly that ‘La Police, she come. Hopla! and Ha, Ha, Ha. Les pamphlets phouff away Ha, Ha, Oui!!’

“Flames spouting out of my eyes and ears, I repaired to the police station and persuaded them to return the confiscated leaflets a bare thousand. The whereabouts of the remaining 4,000 was not known to them, they protested vehemently. On doubling back to the venue, I was given to understand that some French Table Tennis officials, assuming an air of compassionate authority, went out through the main gates and said to my noble staff: ‘Alors garçons, all right hand them over, we will distribute them for you inside.’ Sad! Both the men and the pamphlets lived happily ever after, but where no one knows.

“...Such is the fickleness of fame that almost everybody in England conveniently forgot that I existed and put me in the dusty file marked ‘have beens.’”

Let’s bring back Uzorinac’s book one more time. He wrote that the challenge leaflets were scattered out of an airplane. This was repeated by Swaythling magazine in October 2019.

Didn’t happen. Bergmann could not afford such a luxury, nor would this inefficient distribution method make any sense. And an episode like that certainly would have made it into Bergmann’s book if it were true.

He gave the leaflets one more try at the following week’s English Open, where his distributors threatened a strike unless they received snow-hardship pay. No one ever accepted the challenge. And it didn’t stop critics from accusing him of fear of defeat in tournaments.

So he returned to tournament play in the spring of 1947, with much immediate success, culminating in the hard-fought 1948 world championships in London, where the photo below was taken. Then he immediately turned pro again.

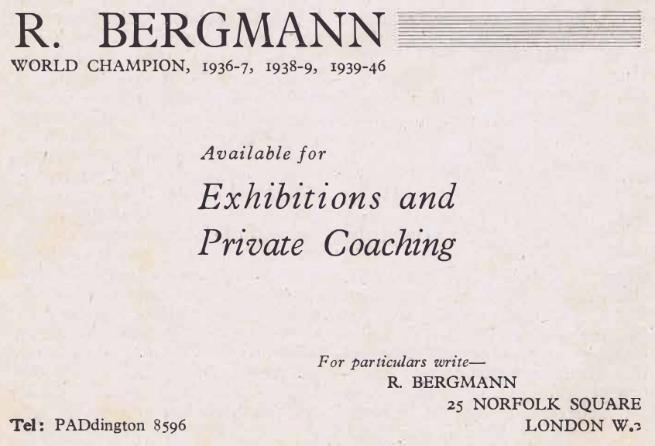

“I am finished with competitive amateur tournament table tennis,” Bergmann told the Daily Express reporter as he hugged his trophy in the dressing room afterwards. “I shall go in now for coaching, exhibitions and theatrical work. This is definitely my last competition.”

From Table Tennis Review, Summer 1947. Note that he styles himself World Champion 1939-46.

At the same time the very next day, according to one source he got married. Victor Barna was best man. Bergmann’s marriage lasted only a bit longer than his tournament abstention. He won 11 more medals at world championships, 1949-55, for a lifetime total of 22.

Richard the Lion-Hearted finally made a good living from table tennis, including traveling the world with the Harlem Globetrotters show for many years. I’m sure he could have succeeded in other lucrative career choices. But only serious illness, at age 51, could take this showman off the world stage.

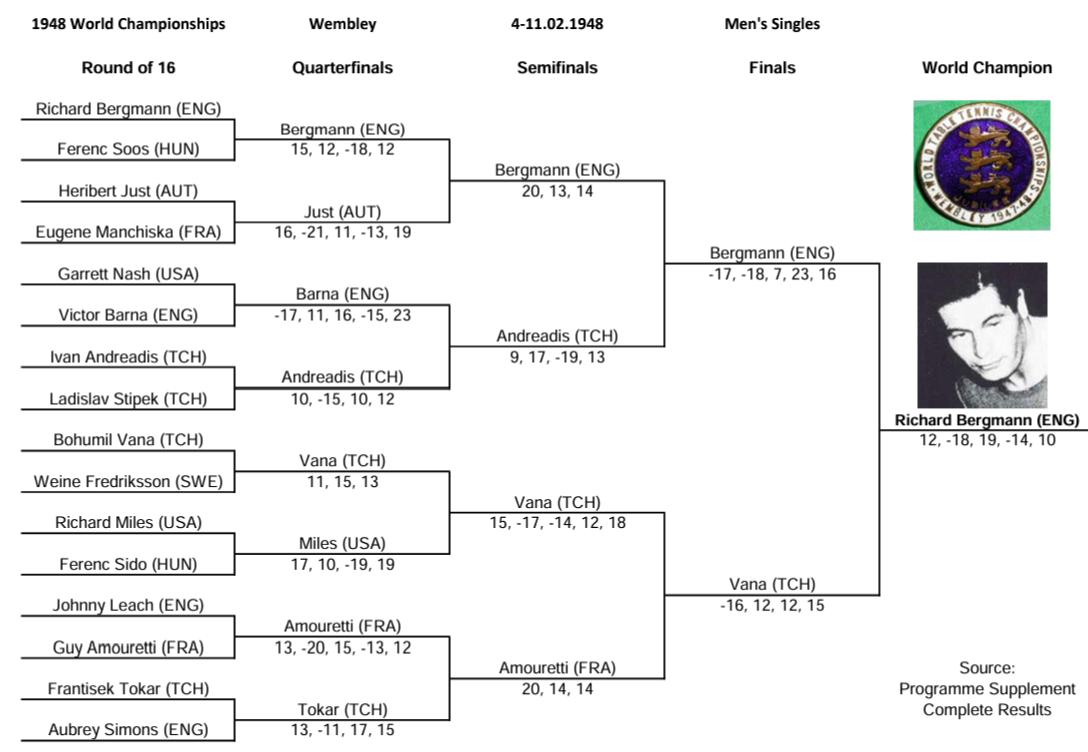

Richard Bergmann is referring to the semifinals of the 1948 World Championships in London, versus Ivan Andreadis of Czechoslovakia, which he also called “the most nerve-racking match” of his career. Many experts, according to his 1950 book Twenty-One Up, consider this “the most classic and outstanding match in the history of table tennis.” After Bergmann won the world singles crown in 1937 and 1939, no championships were held in the seven years 1940-1946. He skipped the 1947 event (see the previous article) but still styled himself the undefeated world champion. After so many years, could he once again grab the brass ring?

It’s a match that has been much written about. Unfortunately, almost every account finds a different way to get it wrong. How can we sift out the correct version?

I believe the most trustworthy source is Bergmann himself but not his book, where he had more than a year to forget and/or purposely change the story. I’m talking instead about the Bergmann who wrote about this match right after it happened, in the Spring 1948 Table Tennis Review.

It was the other Czech, the 1938 and 1947 world champ Bohumil Vana, whom Bergmann saw as his number-one nemesis. By comparison, Andreadis usually did not give him much trouble.

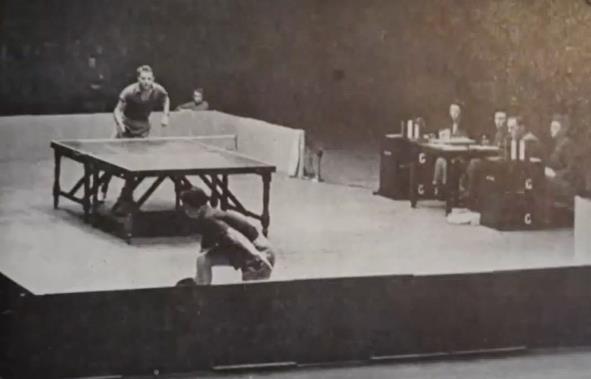

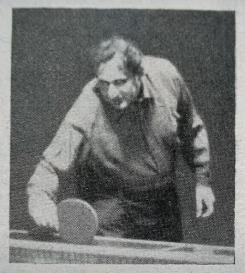

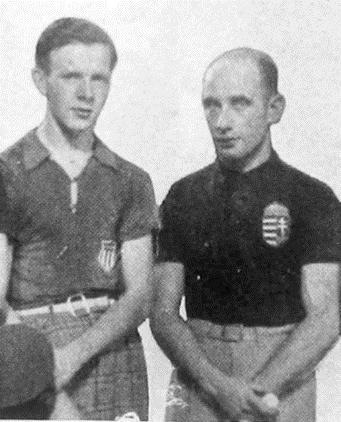

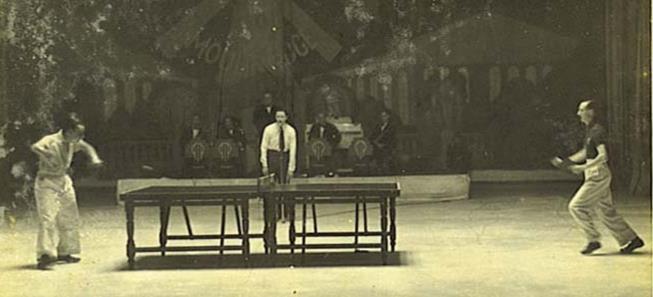

But on this day, Andreadis threw him ten tons of trouble. It was the offense of Andreadis versus the defense of Bergmann. This photo has been published many times, but it seems to be the only one we have from the match and it well captures the typical action.

Andreadis’s attack was sharp as he took the first two games at 17 and 18. In Game 3, Bergmann writes in TT Review, he decided to stick with defensive tactics but double down on focus. Meanwhile, Andreadis temporarily lost focus, became too free with his hitting and lost that game 21-7.

Some sources already have the story wrong at this point, saying Bergmann was behind 19-16 in Game 3. That includes Ron Crayden’s account in SCI News No. 62, November 1996, as reprinted in TTC Issue 16. He may have copied this from the October 1950 Table Tennis Review, page 33. TTC Issue 73 got the game score wrong, saying it was 21-17 rather than 21-7.

Game 4 was a thriller. Bergmann took leads of 19-16 and 20-18, as told in his TT Review article.

Zdenko Uzorinac, in his book ITTF 1926-2001 Table Tennis Legends, mistakenly writes that it was Andreadis who led by those scores, and Swaythling magazine, October 2019, copies that mistake. In his book, Bergmann changes his story, writing that the score was 18-18 before he took that 20-18 lead, and TTC Issue 73 copies that error.

Andreadis won three straight points to go up 21-20, needing only a single point to move on to the finals. He had match point again at 22-21 and again at 23-22. Bergmann saved all three match points and finally won Game 4, 25-23.

Uzorinac mistakenly has it 24-22. In his book, Bergmann adds flourishes to those overtime points that were not included in his 1948 account. We can be skeptical of such details added later, but they certainly made for an exciting, heroic story.

In Game 5, Ivan took a 9-4 lead with steady hitting. From there, his optimal strategy was probably to play it safe for a victorious time-limit win (20 minutes). Instead, he then failed on six forehand winner attempts, giving Bergmann a 10-9 lead. After some back and forth, Bergmann then took ten of the last 14 points to win 21-16.

The writer in Table Tennis, February 1948, apparently slept through the fantastic Game 4, then woke up in Game 5 and called it Game 4. He said nothing about a Game 5, simply adding, “Sadly for the crowd, who had taken the versatile stroke-player [Andreadis] to their hearts, the grim sticking power of Bergmann came out on top.”

The ITTF publication From London to London copied this mistake in 2012.

In the final, with almost no rest, Bergmann faced Vana in another exciting match. TTC Issue 73 states that Bergmann “had very little trouble.” That is wrong. From Table Tennis Review, Spring 1948: “At two games all the atmosphere was electric. Everyone was of the opinion that this was surely the finest display of table tennis that had ever been played. Bergmann's footwork and ability to run in and take over the attack was his bulwark against Vana's phenomenal attack.” It was a very strategic match. In the final game, Bergmann attacked much more than he had against Andreadis, and won 21-10.

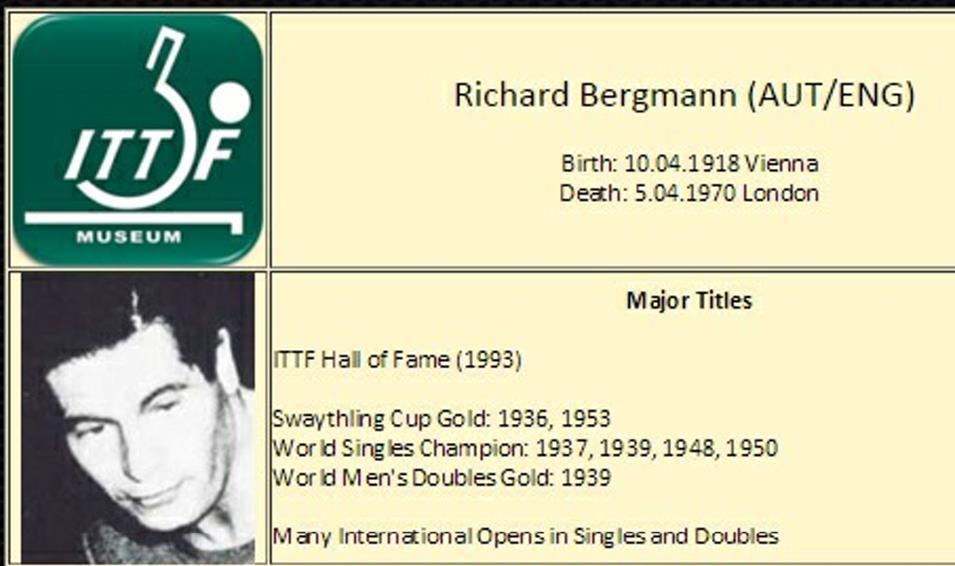

Richard Bergmann was born April 10, 1918.

The ITTF celebrated Bergmann’s 100th birthday in 2019. Unbeknownst to them, they were a year late. The ITTF also said Bergmann was not yet 17 when he made the world singles semifinals in March 1936. They made a big deal of this ahead of the 2019 world championships because Tomokazu Harimoto of Japan, born 2003, had a shot at beating this youth record (but even today Harimoto has not yet reached the semifinals). Swaythling magazine repeated these errors in its October 2019 issue. Bergmann was actually 17, almost 18, when he made the semis.

We can blame Bergmann’s 1950 book Twenty-One Up for much of the confusion. He titles Chapter 3 “World Champion at 17,” and writes, “At seventeen I had confounded all the critics and doubting Thomases to become the youngest-ever player to hold the highest honour.” This was the February 1937 worlds, when he was actually 18, almost 19. (TTC Issues 16, 49 and 73 make the same mistake, as do several other sources.) In his book Bergmann also says he was 13 in 1933. He was actually 14/15.

The 1939 English Open program incorrectly said Bergmann was 16, not 17, when he led Austria to the 1936 Swaythling title.

Zdenko Uzorinac, in his book ITTF 1926-2001 Table Tennis Legends, mistakenly says Bergmann was 16 at the March 1936 worlds and 39 at the March 1957 worlds. Bergmann may have had a rough life at times, but nobody can age that quickly. Both ages were wrong. He was 17 and 38 at those events.

The Hall of Fame of the European TT Union says Bergmann was born in 1919, as does Wikipedia. Encyclopedia.com says 1920. Ron Crayden in TTC Issue 16 said 1919.

Ivor Montagu wrote the May 1970 obituary in Table Tennis magazine, giving Bergmann’s age as 50. TTC Issue 73 made the same error. He was actually five days short of his 52nd birthday.

Skeptical that all those sources could be wrong? Look at who got it right

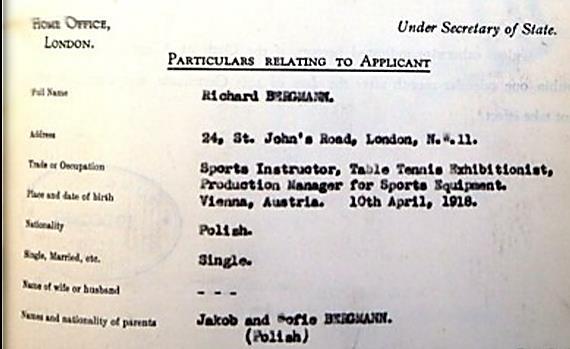

The English naturalization application of Bergmann, in 1946-47, uses the birthdate April 10, 1918, in official documents throughout the process. That was also the date on his final Certificate of Naturalization, seen on the previous page. You can see all the paperwork in TTC Issue 77, page 20, thanks to our colleague Alan Duke.

The English newspapers that ran next-day obits correctly stated his age as 51.

TTC Issue 44, page 3, correctly states Bergmann’s age as 17 in the photo taken at the 1936 worlds (right). (Even if he looks 13.)

Uzorinac’s book correctly states the birthdate as April 10, 1918. He also correctly states that Bergmann was 13 when he made money for table tennis equipment in 1931 (by singing in a mosque choir).

Richard Bergmann, as quoted in Uzorinac’s book regarding the 1937 worlds, said, “My whole body shook out of excitement. I had become world champion at less than nineteen.” Correct not less than eighteen. In Bergmann’s book he says he was almost 30 when he won the February 1948 worlds. Correct again, assuming he means 29.

Alfred Liebster, Bergmann’s Austrian teammate, correctly wrote in the March 1937 Table Tennis magazine, “Bergmann, the new world champion, has no nerves, marvellous defence; a small, young boy, aged 18. If he can improve his attack I cannot see him losing the Singles title.”

Table Tennis Review, May/June 1951, correctly stated that Bergmann was 31 when he won the world championship in February 1950.

The ITTF Museum research tool installed by curator Chuck Hoey had it right, as seen below and in Issue 77. Unfortunately, it seems that tool is among those that are no longer available yet obviously badly needed.

Part Two, Issues 31 thru 43

We continue our look at the first 100 issues of Table Tennis Collector/Table Tennis History Journal. Those issues can be viewed at https://www.ittf.com/history/documents/journals/.

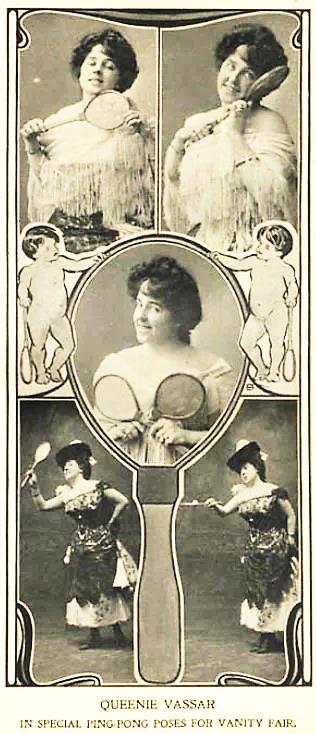

Issue 32. ***Page 6. Shows four postcards from 1950s world championships with autographs of the English team. Issues 29 and 30 show other star-signed postcards, but one that appeared in a later issue is especially poignant, as explained in a separate article on page 26.

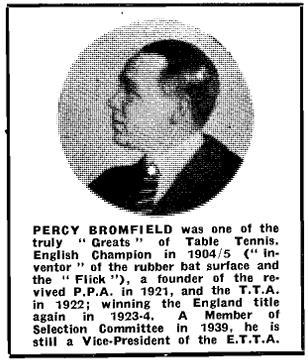

Issue 33 ***Page 12. The biography pages from the 1926 world championships program have two birth-year errors. Percival Bromfield was not born in 1886 at Beckenham; he was born in April 1883 in Birmingham, as seen for example in his 1918 Royal Air Force records. James Thompson was born in 1888 or late 1887, not 1889. His November 1967 obituaries, which called him Jimmie or Jimmy, put his age at 79.

Issue 33 ***Page 14. I am impressed and surprised that Ivor Montagu took two games from the great defender Raja Suppiah, at 12 and 14, as shown here in the 1926 world championships men’s singles draw.

These images show Ivor two decades later, from the video "Reise durch die Tischtennis Geschichte" by our colleague Günther Angenendt of Germany. You can view this 84minute video at Journey Through Table Tennis History. It includes many great photos that I had not seen before. To translate the German narration, use the settings/CC options.

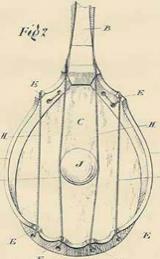

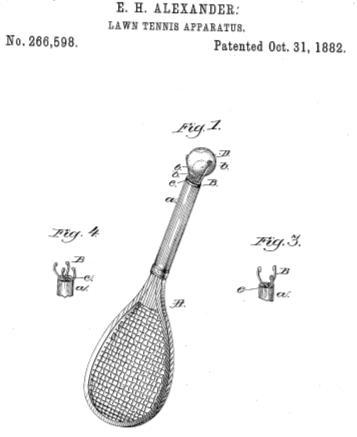

Issue 33 ***Page 16. Gerald Gurney shows a Hamley ad from October 1902. One item is the Challenge bat (left), which he states is “almost certainly the first pimpled bat.” That claim is best saved, I believe, for the Atropos bat that came out at the beginning of 1902. See editor Chuck Hoey’s article on page 4 of Issue 46 for details. He starts the article with a joke: What is the difference between God and a historian? Answer: God cannot change history. In Issue 47, page 10, Chuck follows up with a similar patent filed shortly after the Atropos.

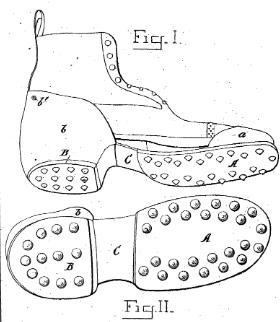

And then there was the wealthy rubber manufacturer George Boyd Thornton of Edinburgh (1852-1908), who translated his footwear expertise into table tennis innovation. In 1895 he patented an improved foot grip attachable to heels and soles made of roughened vulcanized rubber (left). In February 1902 he filed the pipped design at right, shown by our colleague Alan Duke in Issue 74, p. 22.

Chuck is undoubtedly correct that the story of E.C. Goode and the coin mat is just a myth. See Alan Duke’s analysis in Issue 87, page 14. Ivor Montagu, it seems, propagated this twisted tale in his 1924 and 1936 books.

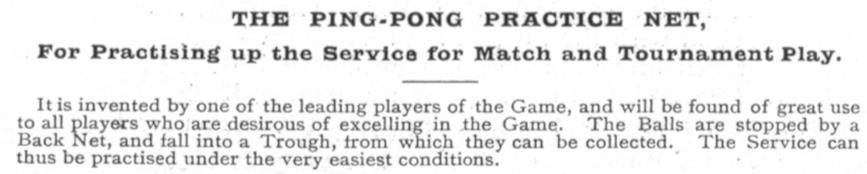

Issue 33 ***Page 16. Regarding the net apparatus (below) in the same October 1902 Hamley ad, I disagree with Mr. Gurney’s statement that serving practice without a human partner is useless.

Spelling lesson demonstrated in this ad: I learned that the British use “practise” only in verb forms and otherwise use the U.S. spelling, “practice.”

Issue 35 ***Page 13. Shows an article written by Percy Bromfield, as edited by Table Tennis, the ETTA official publication, April 1953. We analyze this unusual essay and the strange 1931 original in a separate article on page 29.

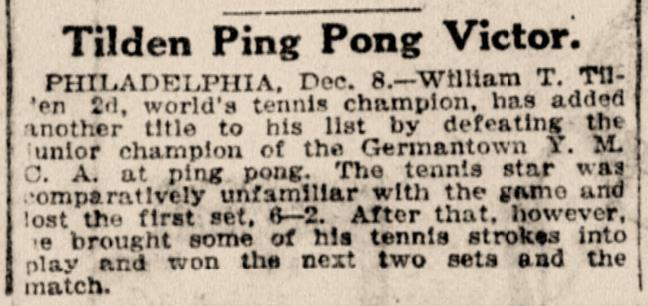

Issue 36 ***Page 3. Gerald Gurney asks whether the great tennis player Bill Tilden was truly a table tennis enthusiast, as represented in his introduction to Cornelius Schaad’s 1928 book A Manual of Ping-Pong. Elsewhere in that book, Schaad writes that Tilden is “naturally a very expert and brilliant player.” Coleman Clark, the U.S. champion, addressed the topic in his 1933 book Modern Ping-Pong and How to Play It. “I got a big kick in Cleveland last winter when Bill and I gave a radio interview on the same program. Tilden said he couldn’t understand why people thought he should be a crack ping-pong player just because he was a shark at tennis. He went on to say that he thought the strokes of the two games were executed in entirely different manners, and concluded with the startling remark that he saw no reason why he should play ping-pong any better than golf.” Later, Clark said Tilden is “scarcely above the dub class.”

Gurney is incorrect that table tennis went unmentioned in Frank Deford’s Tilden biography. It was brief, but Deford wrote, “One Christmas at the Germantown Y, Big Bill made a stirring comeback from one set down to beat the local boys’ Ping-Pong champ.” It was 1921, when he was 28. At right is the coverage in the NY Herald.

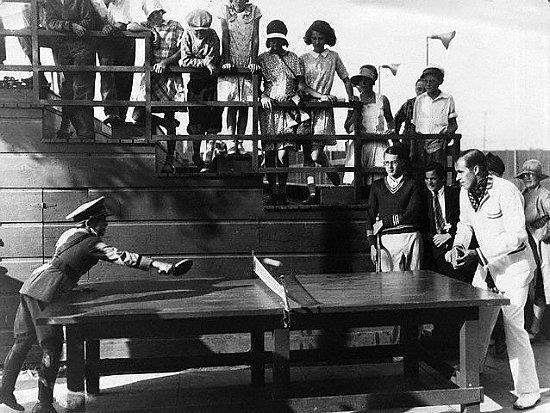

In a 1932 celebrity ping pong tournament at the Hotel Algonquin in New York City, Tilden lost in the semifinal to another tennis player, Ramon Najuch. The champion was songwriter Howard Dietz. This photo is probably from that occasion, with Tilden on the far left, next to boxer Max Schmeling.

In 1936, Tilden watched an exhibition by American table tennis star Jimmy McClure, 19, who had just won the world doubles title (and was to win again in 1937 and 1938). There, he invited McClure to play tennis in his 12-week cross-country U.S. exhibition tour. A good tennis player before he concentrated on table tennis, McClure signed up, premiering as Tilden’s doubles partner only a few hours later.

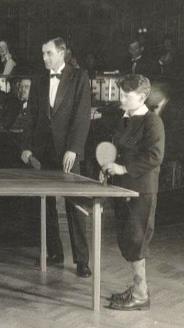

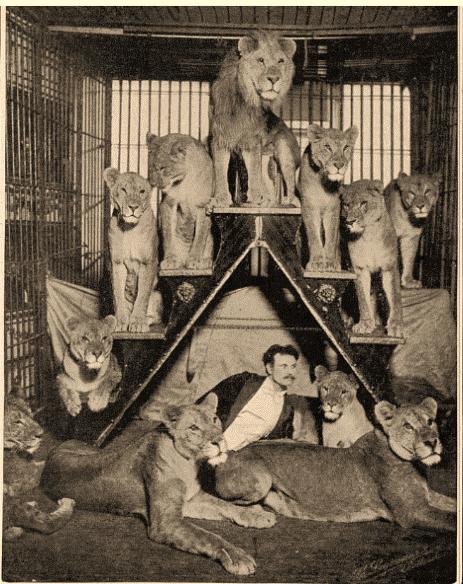

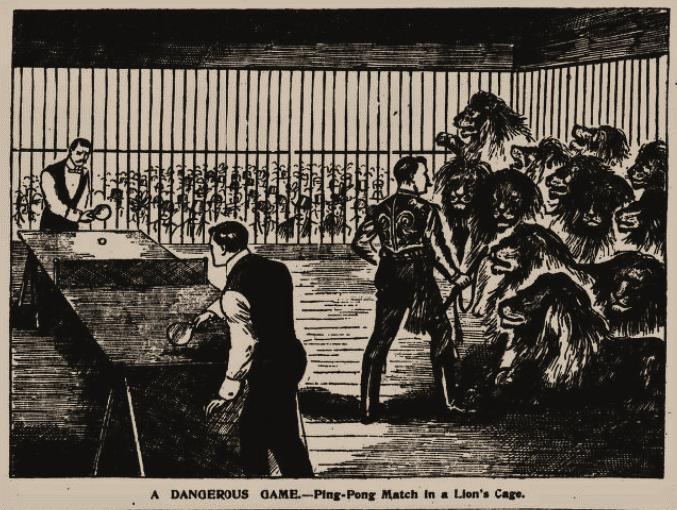

Issue 38 ***Page 6. Displays the commemorative bat from the lion cage ping pong match in Brighton, England, March 8, 1902. Only a week later, in Wales, two members of the Rhondda Ping Pong Club played a match in a 12-lion cage for a gold medal. Lion acts were big at the time, and these were not the only cases in which civilians entered the cage. For example, one lion tamer had his infant son christened among the lions, another had his barber shave him, and a bride and groom were married in a public show (while the other wedding party members stayed safely OUTSIDE the cage).

At right is trainer Charles Prinz and his lions at the Canterbury Music Hall in London, from The Tatler, Feb. 19, 1902. That show included hand-feeding the lions while a female fire dancer did her thing in the cage.

It was good entertainment, and no one was hurt, but some observers were critical. Regarding the Brighton ping pong, one reporter called it “an inconceivably stupid exhibition ... The action of the authorities, in allowing such a dangerous exhibition to take place, has been sharply criticized.” The event was widely covered in the press, but only Illustrated Police News was kind enough to provide a drawing

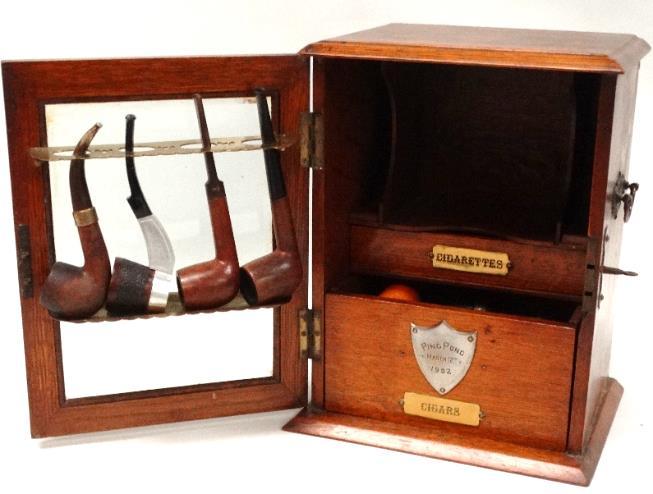

Issue 38 *** Page 7. A small wooden box in the shape of a table tennis table is shown. See the separate article in this issue, page 46, where we exhibit a variety of such boxes.

Issue 39 ***Page 16. Chuck Hoey shows a ball signed by Barna, Bellak, Bergmann and Vana, imprinted 1938-39, and writes that it likely was obtained at the English Open In late January 1939, since all were present then. It more likely was obtained on the England-wide exhibition tour by the four players, January 12 through February 25, a whirlwind of over 30 stops, complete with factory tours and community center speeches. The fifth signer, Hyman Lurie of Manchester, participated in stops nearest his home in early February, when the photo below was taken of Bergmann, Bellak, Lurie, Vana, Barna. Maybe that’s even the same ball!

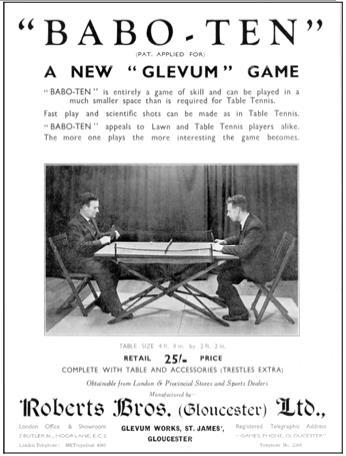

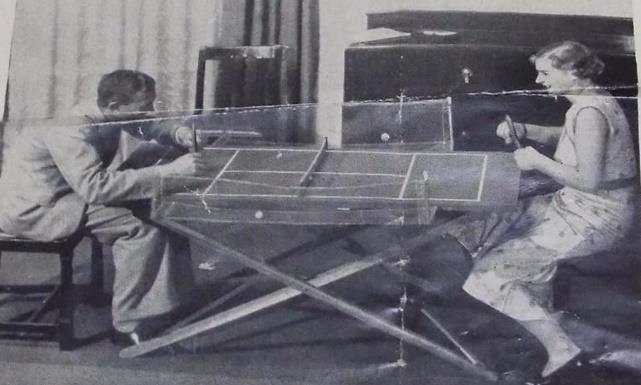

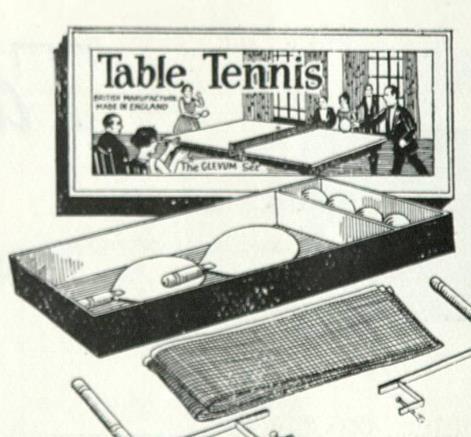

Issue 39 *** On the cover is this ad (right) from 1936, mini table tennis played with a two-handled paddle, made by Roberts Bros. Ltd. of Gloucester, England. So who were the Roberts? See our separate article on page 39 for the story of their important Glevum Games.

Issue 40 ***Page 2. As the editorship of Table Tennis Collector transfers from Graham Trimming to Chuck Hoey, founding editor Gerald Gurney thanks Graham for three years of service. Oops, Graham actually served four years, for which he deserves full credit as the crucial link that kept the publication going. More than that, he did a great job of modernizing TTC and adding new features. While we’re at it, we are of course very grateful to Gerald and Chuck for their superb editorships and dedication. And among all the muchappreciated contributors, I must highlight Alan Duke for the terrific sustenance he provided to TTC throughout the years in the form of meticulously researched, enlightening articles.

Issue 41 ***Page 3. Announces ITTF Museum archives website, a great research resource created by Chuck Hoey. Unfortunately, years later the ITTF stopped supporting most of it, making it tougher today to find data, when it can be found at all.

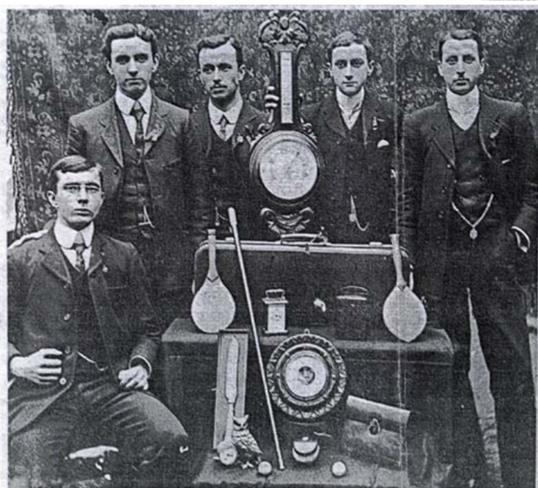

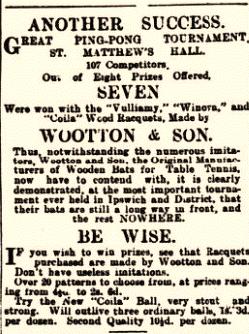

Issue 41 ***Page 8. Shows this great photo of the Woottons and their impressive array of prizes (right), along with two of their special-design bats. I think Gerald Gurney is wrong that the Vulliamy bat was named after their patent lawyer but more on that in a moment.

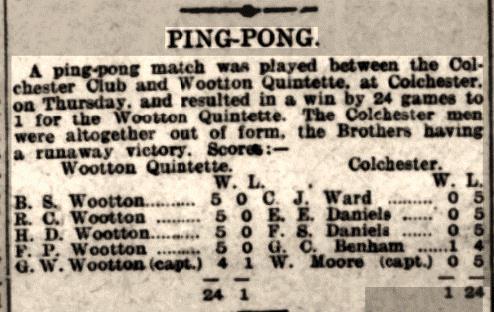

The Woottons made a formidable Quintette, as seen in this box score from March 1902

The Wootton family hairdresser salons were founded by their father, who died in 1893. The salons also sold items such as stationery, toys, perfumes, leather goods, tooth powder and Wootton’s Corn Cure.

In late 1901 they enthusiastically added table tennis equipment of their own make. By the end of November, the East Anglian Times reported, “they have found it necessary to erect a special workshop for its manufacture at the back of their Tavern Street premises, and here several men are employed in executing large orders for Leeds, London and other big centres of population. The wooden bat has already asserted its superiority over all others and is said to have revolutionised the play of ping-pong clubs. Messrs. Wootton have found it necessary also to extend their premises by providing a new showroom for fancy goods and Christmas cards...reached by a staircase descending from the front shop.”

In Issue 65, p. 11, Alan Duke shows us the Wootton design registration application (below) for the Vulliamy bat in November 1901. He ponders why certain parts are crossed out (see inset) and whether the bat was named after the solicitor handling the registration or someone else in the Vulliamy family. [Post-publication late addition: See Alan’s update discovery in Issue 72, pp. 15,17 ]

Here are the answers that make sense to me. First, I believe the drawing and original writing were by the 18-year-old son, Bertram Lewis Vulliamy (the crossed-out “BLV” at far right), who probably created the original design. He was the Vulliamy who was a competitive (if not great) table tennis player, as seen in the box score below (where he lost to George Wootton) from the East Anglian Times, January 28, 1902. He also organized an Ipswich tournament in March with over 100 entrants on six tables. The design and drawing required at least a little artistic talent, so it is worth noting that Bertram’s mother was an exhibited painter (when not giving birth to her 13 children) and his sister Blanche Georgiana Vulliamy was a celebrated ceramicist, painter and writer. His cousin George Vulliamy designed unusual lampposts and benches that I believe you can still see today on London’s Victoria Embankment. Our B.L. Vulliamy went on to a long career not in art and not in law (like his father and one brother) but in language instruction, residing for a time in Finland and Russia.

Second, I believe the three deletions and replacements were done for important reasons by one of the solicitors. Design titles should minimize specificity to be less limiting, so “The Vulliamy” was not optimal. “Ping-pong” was of course a protected trademark, so Table Tennis was substituted. And the name of BLV was not to go on the application, which instead was in the name of G. Wootton & Son.

in January 1902, the widowed mother, Mary Jane Wootton, was named on the registration of “Winova” and “Coila,” along with the eldest son George Ward Wootton (1874-1918). These were done as trademarks, instead of the design route used for the earlier Vulliamy bat, because they realized it was more important (and easier) to protect the brand name than the design.

In March 1902, with tournament season in full swing, they ran ads like the one at right in the East Anglian Times.

Issue 41 ***Page 15. Shows a mystery photo (below). Identification was not provided, nor was the answer given in the next issue. Sandor Glancz and Laszlo Bellak were Hungarian teammates since the 1920s, but Bellak’s hairline measures the year to the 1930s, perhaps a publicity shot for their 1937 U.S. vaudeville tour. At right they appear in the 1928 filming of Ivor Montagu’s Table Tennis To-day. We discuss the film on page 23 of this issue.

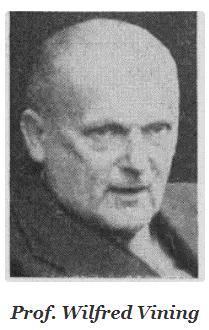

Issue 41 ***Page 16. Shows this medal from the Mixed Singles event of the big Royal Aquarium tournament in January 1902. The tournament had separate events for men and women, so this was a chance for a battle of the sexes. Unfortunately, only one woman entered, versus about 50 men. Constance Bantock was a top player, but she lost in an early round, transforming this into just another men’s event, which was won by a frequent high finisher, Charles Wilfred Vining. A medical student, Vining (18831967) became a pioneering pediatrician and researcher.

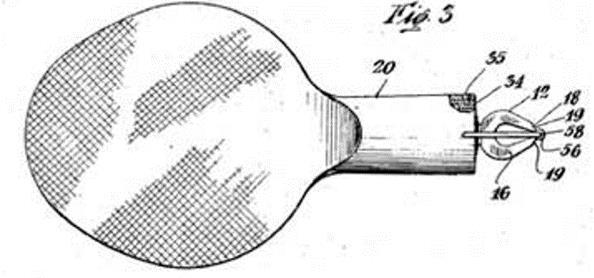

Issue 42 ***Page 3. Discusses several 1902 bats with built-in ball pickup devices. One was patented by George Greenham of London and consisted of a playing surface on one side and lacings on the other suitable to pick up balls. This was impractical and did not catch on, yet Spottiswood Duthie (1866-1926) of Scotland patented a very similar bat at about the same time, GB190202803A. From an important shipbuilding family, he and another Duthie also filed a 1902 patent application for an improved fishing net. But Mr. Duthie was primarily an artist whose paintings today go for thousands of pounds. One theory is that his painted creation at right was embarrassed by his table tennis creation.

Regarding the bat with a pickup cup at the base of the handle, a similar concept had been tried 20 years earlier in lawn tennis (left). Gerald Gurney, in about 1985, had a replica of the table tennis cup bat made and found it was satisfactory (Issue 77, page 18). Our colleague Fabio Marcotulli later did the same, and agreed (Issue 89, page 20). But a demon-style bat, with a semi-circular cutout at the top of the blade, proved ineffective, according to Fabio.

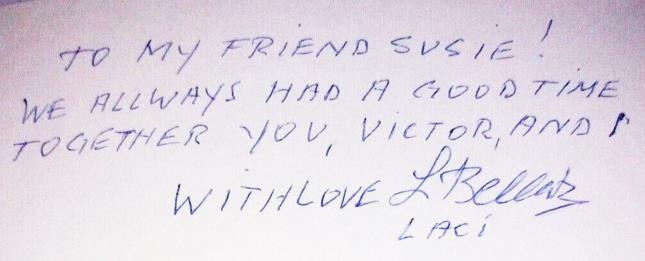

Issue 42 ***Page 9. An obituary of the great Hungarian player Laszlo Bellak (1911-2006) mentions his 1990 book How a New Sport was Born. A signed copy was sold on eBay in 2022, with an inscription (right) to Susie, who married Victor Barna in 1939.

One more built-in ball picker (left) is shown in Issue 45, page 24. This one is from 1940 and uses a pincer extension and balls with magnetic dust. Imaginative, anyway.

Left, world champions Jimmy McClure and Laci Bellak, 1940 and 1990.

Right, Susie Barna (1918-2014) holds a copy of the new biography of her late husband Victor Barna, 1975.

Issue 43 ***Page 3. States incorrectly that an 1895 Tiddledywinks game called Table Tennis is the second-earliest use of that term. It is usually a mistake to state absolutes; such an assertion should at least be qualified by the modifier “known.” Another error was stating that the 1884 Singer game was the first to use the name Table Tennis. Close, but that board game was actually called Table Lawn Tennis, and only in 1887 was it renamed Table Tennis when George Parker put it in his 1887 catalog. Issue 95, page 31, correctly used the 1887 date in showing an example that auctioned for over $1500, calling the game the first known use of the term Table Tennis.

I know an earlier use. Here is an ad that ran every day for a month in the Baltimore Sun, January 1886

This was almost certainly a card or board game, not an action game with bats. In 1892, the Spalding action game Indoor Tennis was called table tennis in the New York Tribune. And 1894 saw the earliest known action game to be named Table Tennis by its marketer, as detailed in the September 2023 premier issue of this journal.

The ambitious maker of that 1884 Table Lawn Tennis, Jasper Hamlet Singer (1846-1922), was one of many heirs to the Singer Sewing Machine fortune of his father Isaac Merritt Singer (1822-1875), who

had 22 children. Living his entire adult life in New York City, J.H. Singer held patents on a sewing machine treadle (1871), bird cage mat (1874), toy theater stage (1881) and bagatelle board (1889), among other registrations. He had a patent gravel paper business, then tried oleomargarine, before hitting on the toy and games business. But that did not always go well either. He entered bankruptcy three times, in 1899, 1901 and 1913, and lost a costly trademark infringement case to competitor McLaughlin Bros

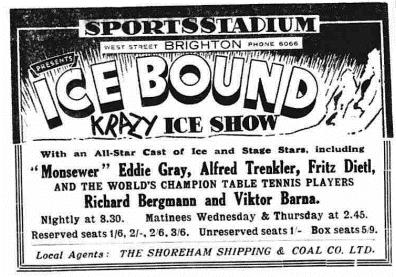

Issue 43 ***Page 4. A postcard pictures table tennis on ice between two left-handed English internationals, Charlie Seaman and Alec Brook. Brook is seen in his usual role as defender, farther from the table. The editor states that they were not wearing skates, which was true, but they WERE wearing special spiked shoe. A few additional details about this Ice Carnival: It took place December 20, 1939, in Empress Hall of Earls Court in London. Ticket proceeds aided the News Chronicle Tobacco Fund for the Fighting Forces. The show included some of the world’s top skaters, plus comedians, acrobats and others, and next traveled to Belfast for a week of performances.

Brook and Seaman had been part of a similar show in Brighton in May and early June before Victor Barna and Richard Bergmann took over for the rest of the summer (left). It was a big year for ice shows, including two popular movies, notably The Ice Follies of 1939, starring Joan Crawford and Jimmy Stewart. The other was Everything’s on Ice.

One of the earliest table tennis matches on ice took place in 1902 New York, as told in Ping Pong Fever: The Madness That Swept 1902 America, page 142. At this Brooklyn Christmas Carnival match, won by Allan Carmichael, “the players did not seem to be bothered much” by the conditions, said the Brooklyn Eagle

Issue 43 ***Page 12. A 1946 poster declares Richard Bergmann’s £500 challenge to all comers. See page 5 of this issue for the full story of the challenge.

Issue 43 ***Page 13. Shows magic lantern slide numbers 2 and 3 of a story entitled Ping Pong and the Mousetrap and speculates incorrectly about the number and content of missing slides. It turns out there were only three slides in this tale, which can be seen in Issue 93, page 58.

Issue 43 ***Page 14. Announces the release of Volume VI of Tim Boggan’s History of U.S. Table Tennis. This series later grew to 23 volumes covering history through 1999. Here we show the cover of Volume I, a greatly detailed, fascinating account of the years 1928-39. See http://www.timboggantabletennis.com/.

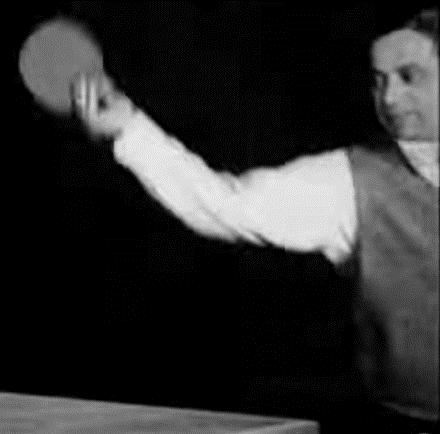

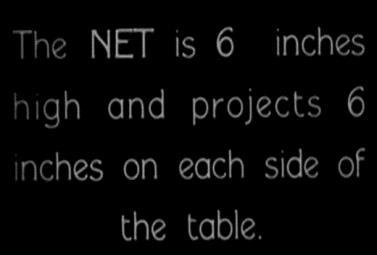

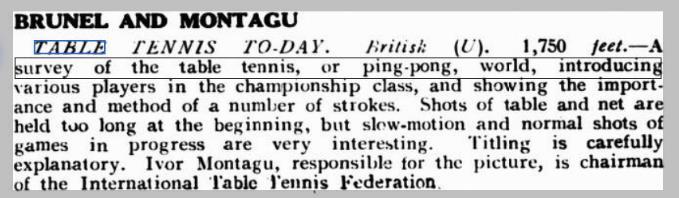

What a special treat to see table tennis stars of the 1920s in action! You can watch the 25-minute film Table Tennis To-day on youtube: 1928 film Table Tennis Collector Issue 48, page 8, reported in 2008 that the ITTF Museum had acquired a copy of the film but did not have the rights to put it on the internet. It was not until 13 years later that our colleague John Ruderham of England played the key role in making this widely available, which he discusses in Table Tennis Times, Autumn 2022. (The Swaythling Club International website has links to issues of TT Times, TT Collector and other publications at Swaythling Club)

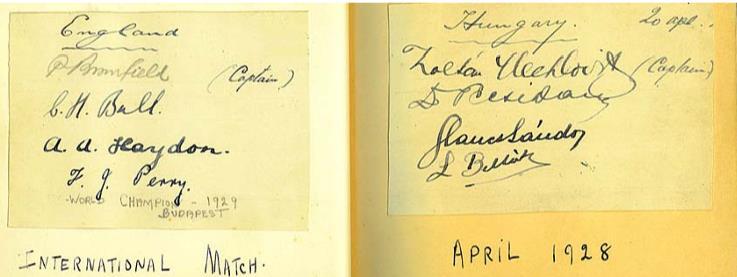

Ivor Montagu must have filmed this in April 1928. That’s when all the top players were in London for the April 21st English Open. The Hungarian stars played exhibition matches in Wales and England in the days before, including Friday the 20th at London’s Memorial Hall. That was when Percy Bromfield’s daughter Valerie obtained the signatures below (from Issue 42, page 10).

Those players are all in the film – Percy Bromfield, Charlie Bull, Adrian Haydon and Fred Perry of England, and Zoltan Mechlowits, Dr. Dani Pecsi, Sandor Glancz and Laszlo Bellak of Hungary as are Joan Ingram and Bernard Bernstein of England, Raja Suppiah of India and Erika Metzger of Germany.

At right is part of the Daily News coverage of that April 20th contest.

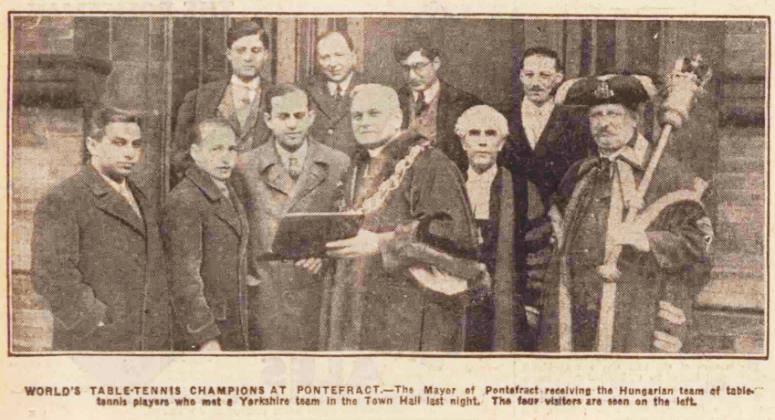

Far left, the four Hungarians (Mechlowits, Bellak, Glancz, Pecsi) at the prior exhibition stop. Referee Ivor Montagu is in the back, center.

The Open failed to finish on schedule on Saturday the 21st, so the finals were postponed until Tuesday evening. (Pecsi and Metzger became the singles champions.) Sunday may have been the filming day, since the Hungarians traveled to an Exeter exhibition Monday.

The film presents an opportunity to examine the varied hitting styles of the day.

Forehand Below, Bromfield begins the stroke. Below right, he uses two different follow-throughs, medium force and kill shot.

contrast to Bromfield,

are two stages of the same

Note the target chalked on the table for filming purpose.

Backhand Compare the Bromfield backhand follow-through at left with the penholder backhand of Mechlowits, which Montagu shows with two cameras, from the side and from above.

An error in the title cards: Montagu or his assistant left room to insert the fraction ¾ in smaller type between “6” and “inches,” but forgot to go back and add it.

Montagu undertook numerous film projects in 1928, so it was a while before he got around to finishing post-production on this one. His wife Hell may have helped with editing, as she did on some other films. She also worked for Montagu’s film partner Adrian Brunel, who called her “the magnificent and incomparable.”

It appears that Montagu saw the film as a potential aid to the English players’ technique. That would have been an incentive to finally get it done before the next world championships. On December 15, 1928, after the trial matches to select England’s international team, Montagu showed the film to the players. They found it “extremely interesting,” according to Kimenatograph Weekly, and indeed it must have been fascinating to see themselves in action for probably the first time ever. In early January, it was publicly screened in both London and Budapest. Above is the review from Kimenatograph Weekly.

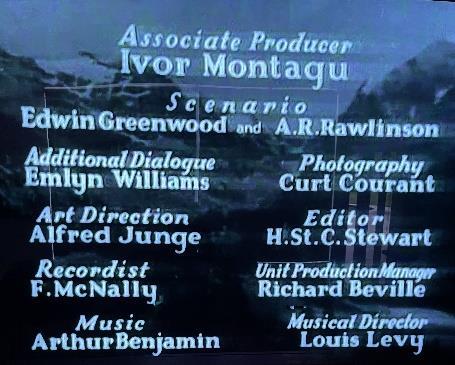

Montagu was a figure of importance in 20th century film history, as a pioneer of the art-house cinema movement, as a collaborator with Hitchcock, as a friend to Chaplin and Eisenstein, and as a director and producer in his own right. At right is a credit frame from Hitchcock’s 1934 The Man Who Knew Too Much.

We are fortunate that Montagu chose to make Table Tennis To-Day.

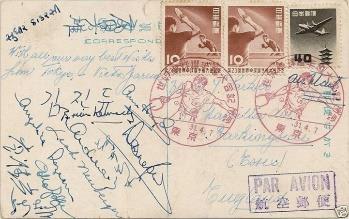

I would love to open my mailbox and find a postcard from the World Championships, signed by the star players. Such cards were shown several times in Table Tennis Collector, mostly in Issues 29, 30 and 32. Viewing them freezes a moment in time and captures the imagination.

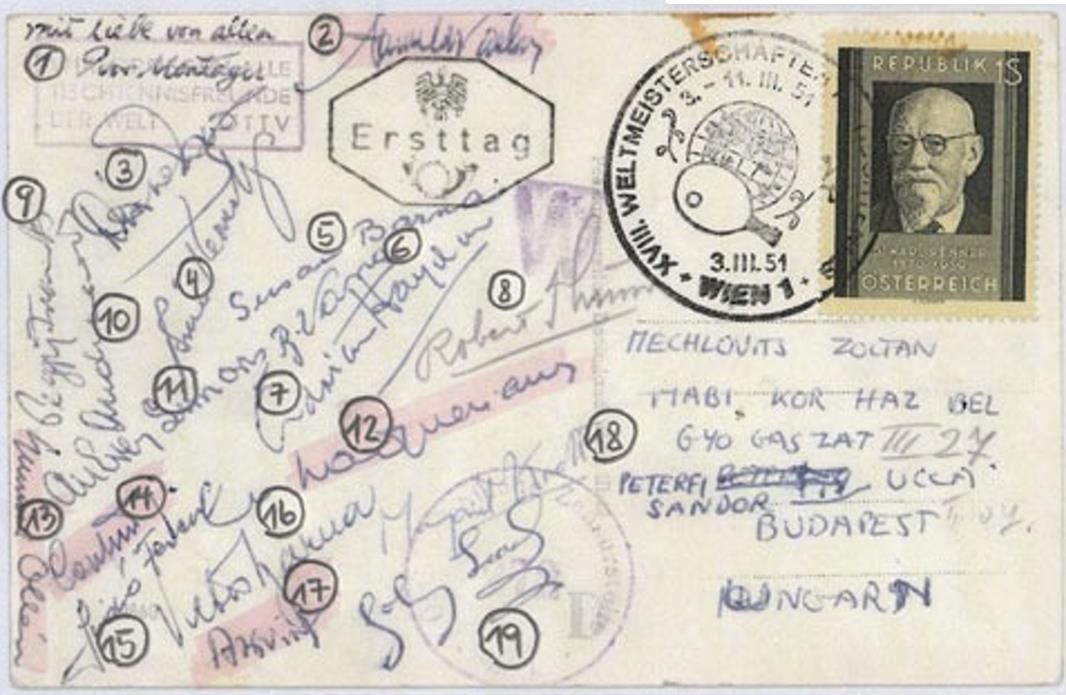

You will find one of them particularly poignant when you understand the circumstances. It was contributed by our Austrian colleague Christian Klaus in Issue 76, p. 50, seen below. (The numbering in this photo was used for autograph ID purposes, and numbers 2, 13 and 14 remained unidentified.)

Signed in March 1951 by the English team and several international stars

The ITTF president Ivor Montagu signs a simple message in the upper left, “mit liebe von allen,” with love from all, to a hospitalized former player in Hungary. This long-time friend had twice escaped from death camp transports during the war, and then suffered a serious post-war injury, all of which left him in ill health. Yet he continued attending world championships, where he coached and encouraged the young players, even himself playing in the 1948 veterans event. He captained the Hungarian team for many years both before and after the war. But he was forced to miss this 1951 championship: Zoltan Mechlovits, winner of six world gold medals in the 1920s, died three weeks later at age 59.

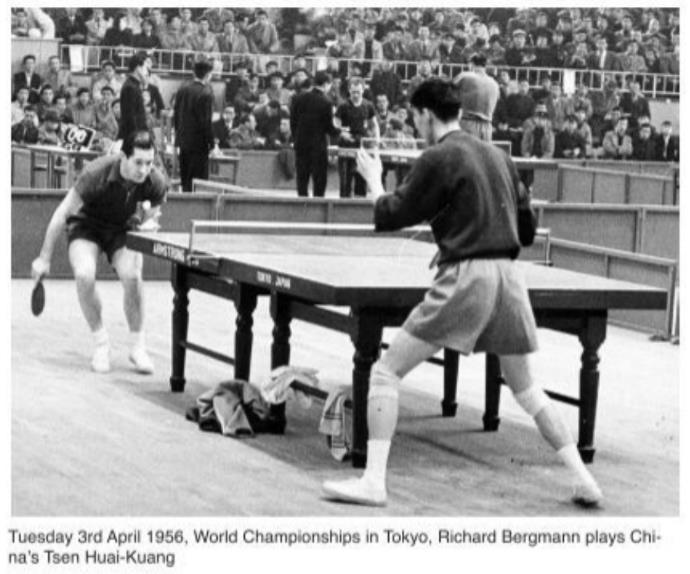

Signers of the above card included Victor Barna and his wife Susan. In coming years, Victor himself sent a number of autograph postcards from World Championships. I have one, shown on the next page, that has a signature of special significance. That is Tsen Huai-Kuang, the earliest autograph of a Chinese world medalist. He and his four teammates took bronze in the 1956 Swaythling Cup, the first

Worlds success by China in its long, long dynasty to come. Tsen signs in the lower left, just above Johnny Leach.

Tsen is seen at right playing Richard Bergmann in the China vs. England match a few days earlier.

Other autographs on this card include four gold medalists from that year: Yoshio Tomita (Japan), doubles and team; Leah Neuberger (USA), mixed doubles; and Angelica Rozeanu and Ella Zeller, doubles and team champions from Romania. Other signing 1956 medalists were Ivan Andreadis (CZE), Ann Haydon (ENG), and Diane Rowe (ENG).

Several other 1950s postcards sent by Barna from the worlds can be seen in the Hungarianlanguage two-volume biography of Barna by our colleague Laszlo Polgar, reviewed in Issue 72.

Here is a list of other autographed postcards mailed from the worlds that appeared in TTC, mostly from the collection of our colleague Hans-Peter Trautmann of Germany:

1948, signed by Czech team; 1953, Hungarians and Yugoslavs; 1955, Czechs (Issue 29, p. 16)

1948, signed by French team (Issue 30, p. 3)

1951, 52, 53 and 55, English players, posted by team member Adrian Haydon or his daughter Ann, each sent to the Arundel family (Issue 32, p. 6). The Arundels, husband and wife, were competitive in Birmingham table tennis tournaments. I know of a similar postcard that Adrian Haydon sent in 1952 to Mr. W. Hackett, another Birmingham player.

1955, signed by several international stars (Issue 79, p. 33)

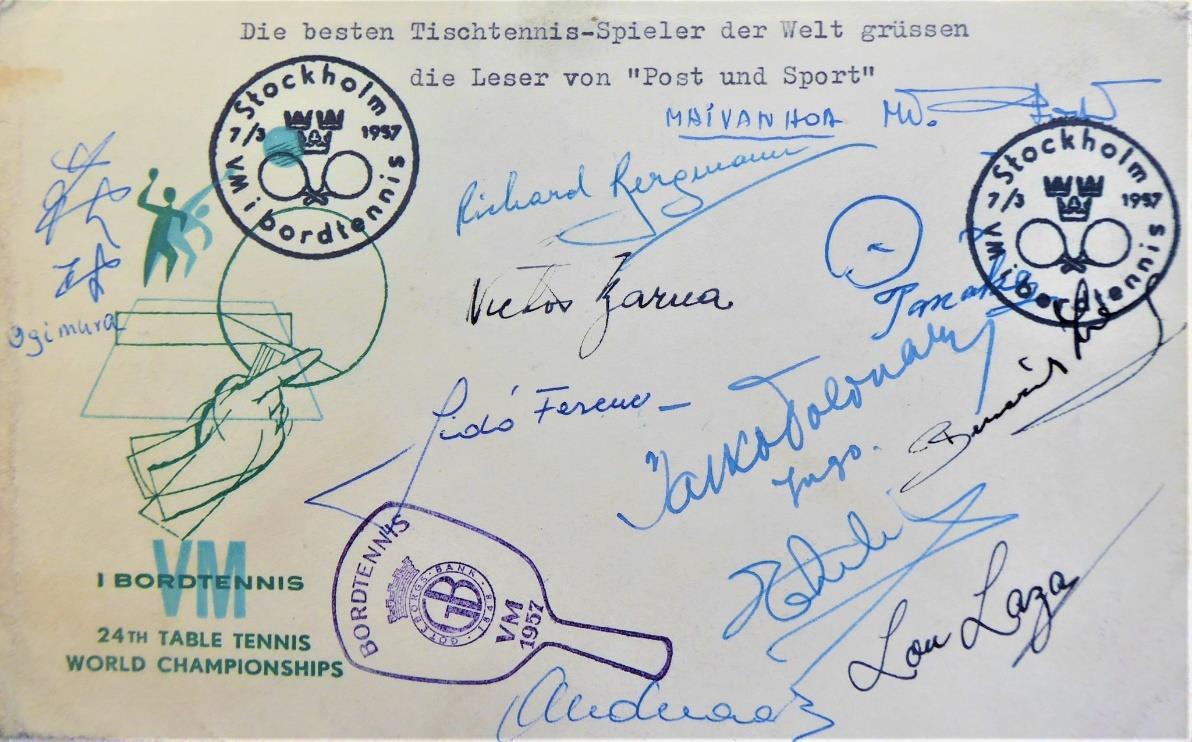

Finally, here are two 1957 cards signed by world champions and others. They look quite alike, and the signers are only somewhat different. They both send greetings from “the best table tennis players in the world,” one card to readers of Sportbericht (Sports Report) and the other to readers of Post und Sport. I suspect many such cards were sent to periodicals back home, hoping to publicize the sport.

These cards and many more can be seen at Günther's postcards.

That is from the Facebook of our colleague Günther Angenendt of Germany, which has many great historic photos and collectibles, at Günther's Facebook.

Percy Bromfield’s article for Table Tennis World had a lot of potential. Unfortunately, he turned much of it into a mess in his effort to conceal his age. Just as important, this also hurts the credibility of his claim to have invented the rubber bat surface. This was a claim that had low credibility to start with, given the known early patents by others. For that, see the bottom of page 14 in this issue.

Elsewhere on page 14, we noted that the 1926 worlds program mistakenly had his birth year as 1886 instead of the 1883 date of official records, including his Royal Air Force enlistment. This could have been an innocent mistake. More likely, it was either vanity or Bromfield’s thinking that his advanced age (43) worked against his longevity on the English national team, or both.

Asked in 1931 to write about his early table tennis life, Bromfield starts by stating that he “felt very much like one who is about to enter the confessional box.” What was there to confess, other than his age? Instead of confessing, though, he targets a still-earlier birth year, 1887. Steadfastly adhering to that, he changes the dates of events and even their order.

In the first half of his article, Percy names no dates. Nonetheless, there is one chronological oddity he has his younger brother Donald Arthur Bromfield (1885-1915) finishing school before him. At right is 15-yearold Donald as he appeared in a Boys Own Paper article about the top schoolboy cricket players, July 7, 1901. In future years, Donald and Percy were also noted for their football skills.

Then he arrives at the most awkward part, what he calls “the more intimate part” the part where the guilty party first declares he is telling the truth to block any accusation otherwise

Yet “deface time” he does, badly. He won the UK championship in 1903-04, not 1904-05, and he was 20 at the time, not 17. He goes on to state that the TTA was formed during a service controversy in 1905-06. The TTA was actually formed in late 1901, and the PPA vs. TTA service controversy took place in 1902-03. Indeed, by 1905 organizations, national championships and table tennis itself had mostly gone into hibernation.

There is still more to this strangeness. In the early 1950s, the ETTA was having difficulty locating Bromfield, who was a vice president of the organization. Meanwhile, in the April 1953 Table Tennis, they reprinted his 1931 article in a shortened, edited version (shown in TTC Issue 35 and again in Issue 59), with the following head

“Thanks to some data given to us”? Going through contortions to avoid citing the source, they clumsily write that based on that data, “...we have been able to make up and present...” the writing by Bromfield 22 years earlier. I think they were concerned that they had neither Bromfield’s nor the defunct publication’s permission to print this, so they distorted the original article in an effort to protect themselves.

While the 1953 version made many edits to his writing style (mostly unnecessary) and deleted the final section, it made only one edit to the facts, the elimination of Bromfield’s error about the TTA formation date.

This photo accompanied the 1953 article. The caption repeats the mistake of calling his UK title 1904-1905 instead of 1903-1904. It also states that he is “still a Vice-President of the E.T.T.A.,” even though he had died six years earlier. Presumably, the duties of a VicePresident were not onerous. The obituary finally appeared in the April 1954 issue: “...some months ago...it was clearly established” that Bromfield died in 1947.

Unmentioned by Percy is his younger sister Gladys Mary Bromfield (1888-1904), who also enjoyed table tennis success. Athletic Chat, Feb. 18, 1903, stated she is “no doubt profiting by family practice ... a keen player and no doubt soon will equal her brothers.” The reporter, A.W. McQue, was covering and competing in the Alexandra Palace handicap tournament. Gladys won ladies’ and Donald won men’s, with Percy third. (Both brothers owed 10 points in a game to 40.) McQue, who was also at times a tournament organizer, added, “Being unable to secure a game with her sons, I challenged Mrs. Bromfield, but I will not cause bad feeling by giving the result, in case I have to meet Percy or Donald in the next tournament.” Gladys won the March 1903 handicap, too, as a Receives 5, and won again in November as a Receives 3, when she was called “a young player of great promise.” Sadly, she apparently died only months later, of causes I am unable to discover.

Finally, yet more strangeness: Though we are informed by two sources that Percy died in 1947 (see also the update by Alan Duke in Issue 97), a Table Tennis Review columnist wrote the item at left in the October 1950 issue. The final sentence says it all.

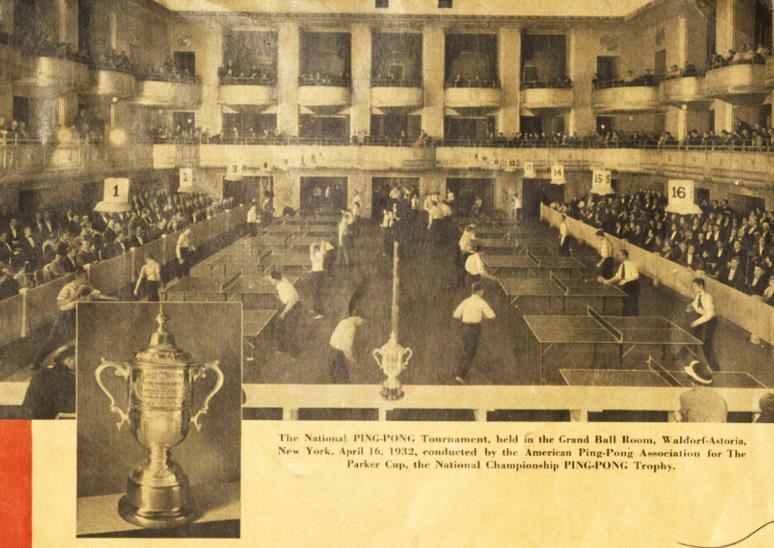

First please allow me to relate some history. Parker Brothers backed the formation of the American Ping Pong Association in 1928. The APPA would spread the gospel of true wholesome Ping Pong throughout the land. Not generic disorganized table tennis, you understand, but only the right stuff, particularly Parker equipment and rules.

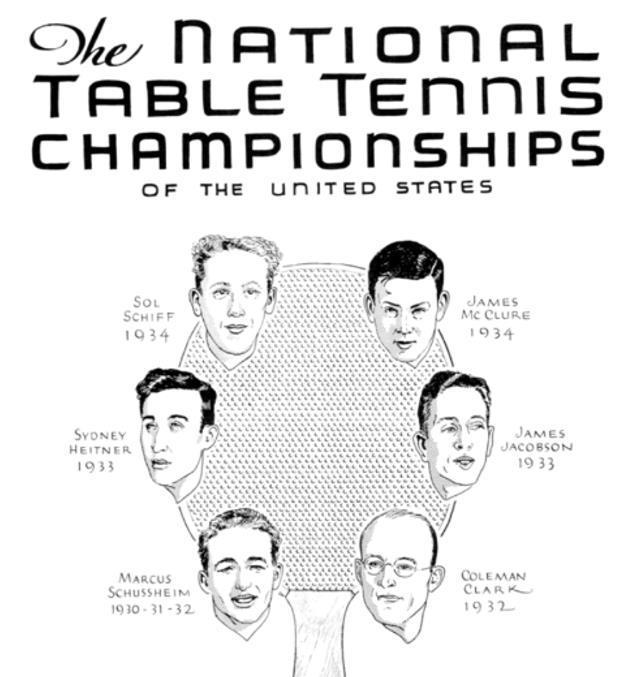

Parker encouraged clubs across the country to join. Numerous local and regional APPA tournaments were held in 1929 and 1930, and Parker sponsored the first national tournament in 1931 in New York City. The winner was Marcus Schussheim (who had also won their unofficial national title in 1930), seen in the trophy presentation photo in the 1931 Parker catalog

Historian Tim Boggan points out that nobody is smiling, and suggests Parker executives were not pleased by the image projected by this winner: a lower east side New York City 18-year-old rather than, say, a Bill Tilden or Douglas Fairbanks type. (My examples, not Tim’s. Read Volume I: 19281939 of his History of U.S. Table Tennis for a superb, wonderfully researched telling of these years.)

The trophy in that 1931 photo is not the Parker Cup, which was not yet created. Observe the fourth gentleman from the right, in suit with pocket square. He would become the first winner of the Parker Cup a year later. Coleman “Cokey” Clark of Chicago was more the Parker type decorated World War veteran and all-around athlete (though a bit old, born in 1896).

Here is coverage of the more glamorous second tournament, the 1932 APPA, by Time magazine

“Lo Wenching comes from Peiping [Beijing] and he learned to play ping-pong at Tsing-Hua University. He, like other ping-pong players, hates mention of table tennis because so many people confuse it with ping-pong which is played with patented equipment, on a standard court, by standard rules. [Hmm, I wonder, did the Time reporter gather this info from Mr. Lo himself or from Parker Brothers?] Lo Wenching and 255 other able ping-pong players last week assembled in Manhattan for the second annual U. S. championship. The matches were played in the grand ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria hotel. Among the 1,000 spectators...happily watching the matches from a lavish box was George Swinnerton Parker of Boston, decorated by a white goatee and a pique evening waistcoat. He had donated the Parker Cup, to be engraved with the name of the

champion. His firm, Parker Brothers, controls the U. S. rights to ping-pong and manufactures 640 other indoor games of which Mr. Parker personally invented more than 200.

“...Most of the contestants wore leather-soled shoes because rubber ones gripped the carpet and made it slide...Only 10% of the players used the old-fashioned penholder grip. Their rackets were faced with rubber, not sand or wood.

“...Abraham Krakauer of New York University, an unseeded player...played Coleman Clark of Chicago in the final. Clark, accustomed to the finest ping-pong room in the U. S. (at the Chicago Inter-Fraternity Club), is an investment banker with A. C. Allyn & Co. He used to be on the University of Chicago football team and was a tennis star in the Western Conference. The amazing speed and variety of his strokes chops, drives, sidespins, baffling changes of pace were too much for little Krakauer, who stood well back from the table and played in a shrewd but more defensive style. When he began to make Clark miss his shots in the last game, it was too late to do any good. Clark had match & championship, 21 10, 21 13, 21 15.”

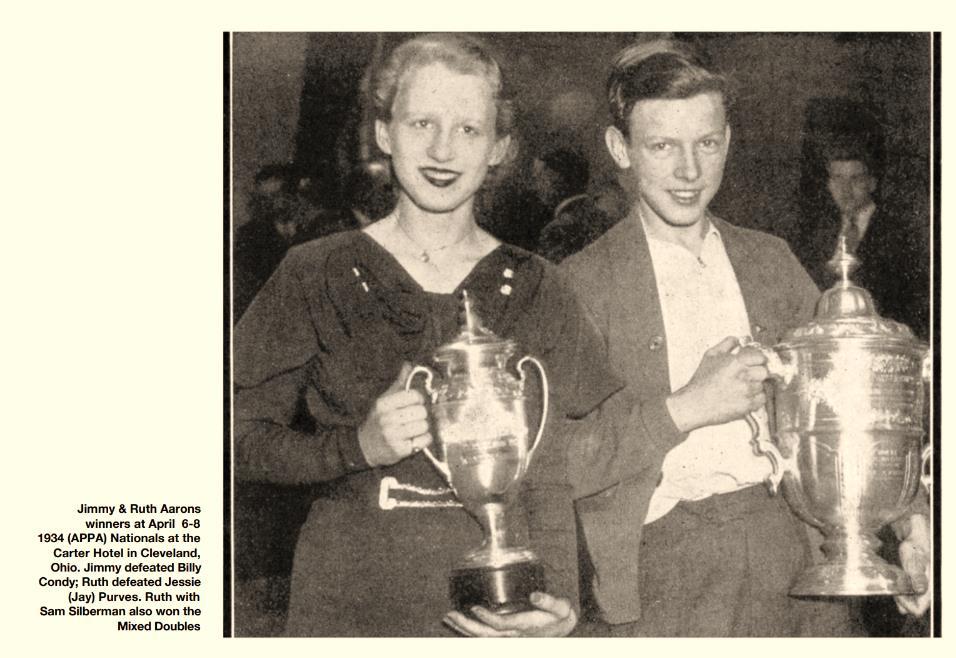

Clark’s personal experience, from his book

But there was a cloud over this very successful 1932 tournament, a cloud that would soon grow. Missing in 1932 was the 1931 champion Schussheim, as well as many others from the New York area. That’s because they left the APPA to form the NYTTA and become independent of Parker Brothers. They held their own national championships in May 1932 at the Bamberger store in Newark, New Jersey, where the defender-style Schussheim successfully defended his title over 150 entrants. The 1933 NYTTA nationals shifted to a New York store, Gimbels, where chopper Sidney Heitner of New Jersey, a young insurance salesman, was the winner among the 188 entrants.

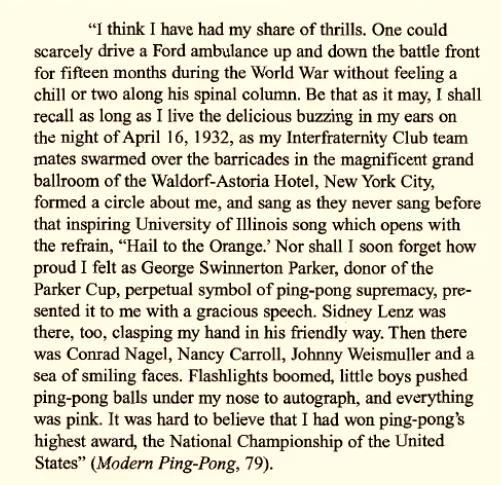

In 1933 the APPA moved the national championships to Chicago and another fancy ballroom. Jimmy Jacobson, an NYU freshman from Westchester County, north of New York City, was the winner. He is said to have used the windshield-wiper (Seemiller) style, though his grip is difficult to interpret in the pose shown here. These photos are from Boggan’s Volume I

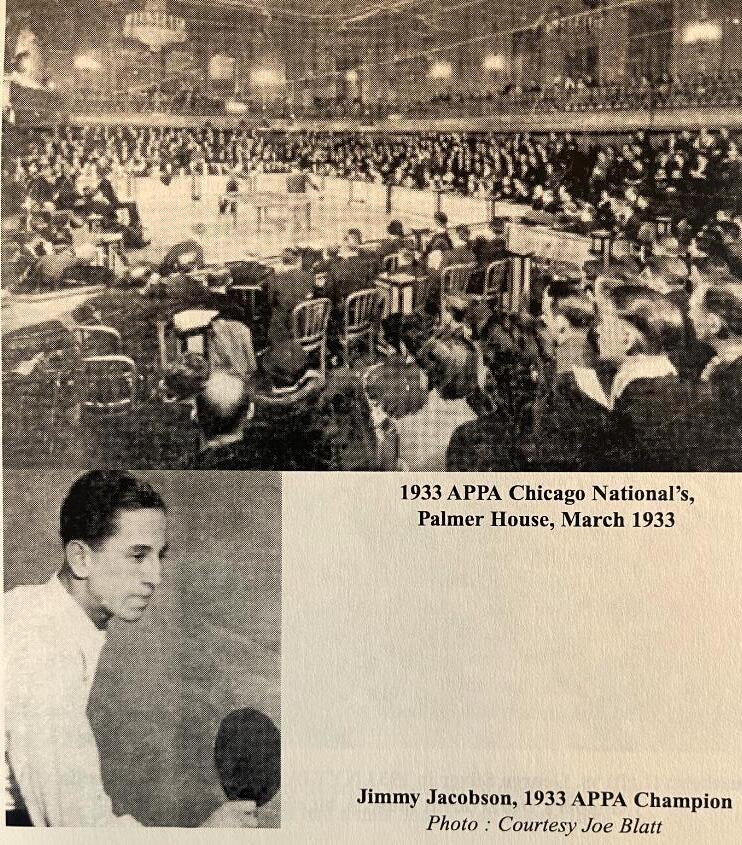

In 1934, Jimmy McClure of Indianapolis, future world doubles and team champion, became the third name to be engraved on the Parker Cup. This photo is from Jimmy McClure, A Retrospective by Dean Johnson and Tim Boggan.

Do you see anything missing from McClure’s trophy, something that was in the photos on the previous page? Somehow, somewhere, the black plastic base went missing and is still missing.

Here is the trophy today, 20 inches tall

Three names were engraved

The trophy was recently discovered and lovingly restored by Phil Orbanes (below), who worked at Parker from 1979 to 1990. Phil told me the story

“I ran the R&D department at Parker Brothers for 12 years and never saw the Cup, although I knew the location of a deep storage room where it and many other priceless games were sealed in boxes. In 1991, Hasbro acquired Parker Brothers and ordered its archives to be merged with that of its other major game acquisition, the Milton Bradley Company in East Longmeadow, MA. During this process, most of those sealed boxes of rare games “disappeared.” I assumed the Cup was amongst those that had gone missing. Fortunately, I had gained access to the combined “PB-MB” archives on a number of occasions to conduct research for manuscripts. Late in 2022, the Cup emerged from the clutter in a seldom seen room. With all the items in this room targeted to dispersal, the Cup found its way to me. I then removed nearly nine decades of tarnish.”

Phil had a long career in the toy and game industry, both before and after Parker. He has authored a number of Parker-related books, including The Game Makers: The Story of Parker Brothers from Tiddledy Winks to Trivial Pursuit (2004), available at Amazon. Among the many interviewees for his

research was Robert B.M. Barton (1903-1995), who took over the top Parker job in the early 1930s from his father-in-law George S. Parker (1866-1952), the company founder, who is seated in this cropped photo. Barton is standing at left. The full photo is among the extensive research archives contributed by Phil to the Strong Museum of Play in Rochester, NY.

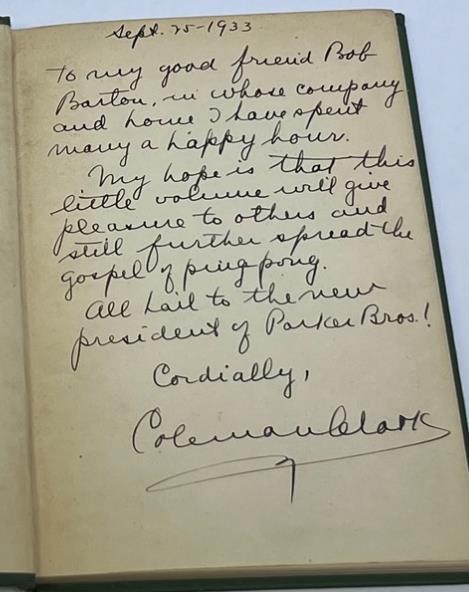

At right is an interesting signed copy of Coleman Clark’s 1933 book Modern Ping-Pong, given to Robert B.M. Barton. Several years ago this was presented to Phil by Randolph P. Barton, Parker’s grandson, who ran Parker Brothers from 1973 to 1985. The inscription reflects a real love affair between Clark and Parker Brothers that began even before Clark won the Parker Cup.

It seems the love soon faded, though, because Clark was among many who switched allegiance to the new USTTA in 1934. That marked the end of the APPA national championships, especially since Parker Brothers was struggling badly in the economic depression and had to cut expenses. (The company was soon saved by its new hit game, Monopoly, in 1935-36.)

Parker tried a new approach in 1935, marketing Ping Pong racquets endorsed by Victor Barna and Parker Cup winner Jimmy McClure. That got McClure in hot water with the USTTA, but that is another story. The bats did not sell well, and Barton wanted Mr. Parker to finally abandon his big Ping Pong hopes. The following is from an interview of Barton conducted by John Fox in 1986, which can be found in the online archives of the Strong Museum of Play

“That was Mr. Parker’s sorrow. He tried to establish a trademark. I knew it would never work. Nothing to pin it on! A tables a table!...I begged him not to spend any more money on it...He was determined he was going to establish that thing as The Thing....I said, it’s just impossible, Mr. Parker. You have a tennis tournament, if you were to tell the people they had to have a Wilson racquet or a Spalding racquet, or something else, they’d just tell you to go fly a kite! You can’t do it. He, he had never had anything to do with sports. That’s the one mistake he made in his whole career...that Ping Pong trademark...you couldn’t force people to use that, so didn’t do you any good at all. Table tennis racquet, as far as the public’s concerned, they can see it. Now Kodak, what’s inside of it, you can’t see it.”

At one time, the APPA had hoped to hold an international championship in conjunction with the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, if not sooner. But ITTF president Ivor Montagu enforced a firm eligibility rule against trade-related national organizations. By breaking away from Parker, the U.S. could finally enter the world championships. Schussheim won the American Zone title in November 1933, giving him an expense-paid trip to Paris for the December worlds, where he saw numerous players better than he had ever seen before. At the following worlds, in 1935 London, the U.S. sent its first full team, namely Jimmy McClure, Sol Schiff, Gilbert Marshall and Bill Stewart. In 1937, the U.S. won the world team championship over the great Hungarians.

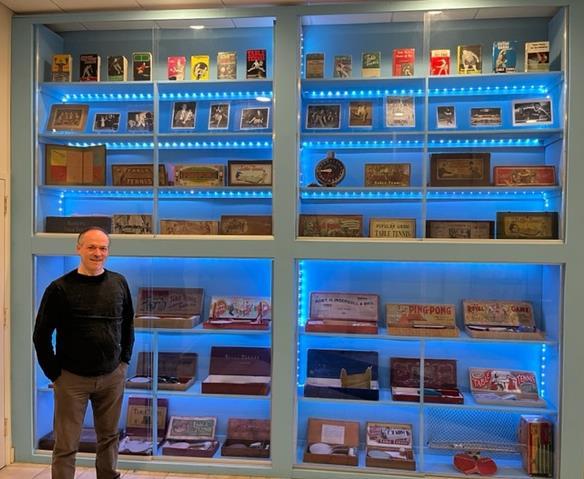

Our colleague Will Shortz recently acquired the Parker Cup from Phil. Will is the long-time owner of one of the top clubs in the U.S., the Westchester Table Tennis Center, which expanded to 30 tables a few years ago. I believe it awards more prize money in more tournaments than any other U.S. club.

Will has stepped up his collecting game in recent years and has installed a beautifully lit display in the club lobby.

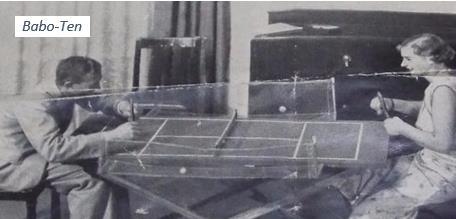

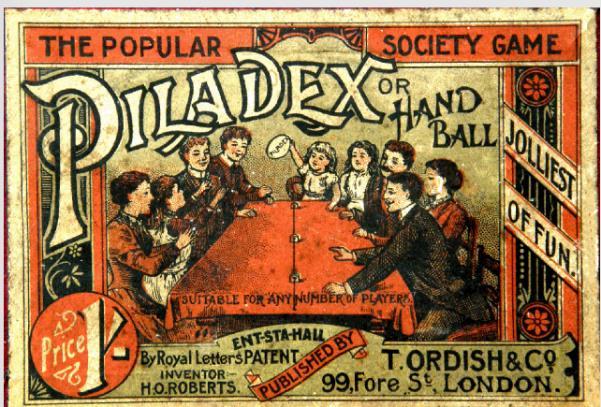

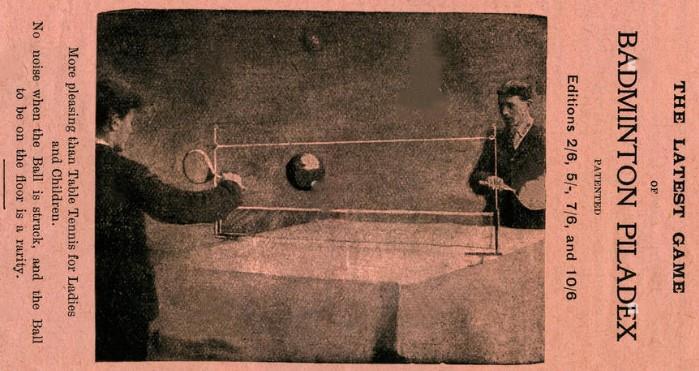

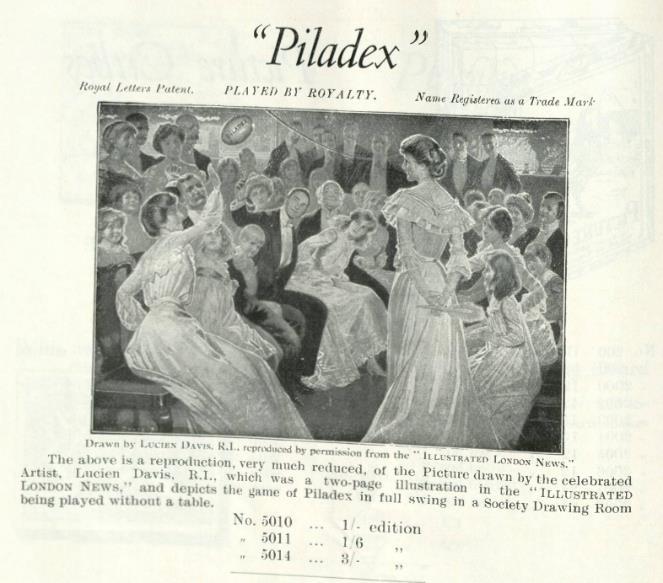

The cover of TTC Issue 39 shows this ad (left) from 1936, mini table tennis played with a two-handled paddle, made by Roberts Bros. Ltd. of Gloucester, England. So who were the Roberts? Harold Owen Roberts (1860-1929) invented Piladex and placed the ad below in December 1890. This became the foundation of Glevum Games, which grew to a firm with hundreds of games and hundreds of employees. His brother John Owen Roberts (1862-1935) was his partner, and they became two of the most prominent men of Gloucester government and business. (In Roman times, Gloucester was known as Glevum.)

At one point, Glevum may have been the largest British toy and games manufacturer. Their 1932 catalog carried 14 different table tennis sets, including the one below, plus games such as Plopitin and old favorite Piladex (below right), still using the decades-old Lucien Davis illustration.

In 1954 Glevum was acquired by British toy firm Chad Valley.

Badminton Piladex, introduced not long after the Ping Pong craze, required hitting a balloon over a net but under a wire.

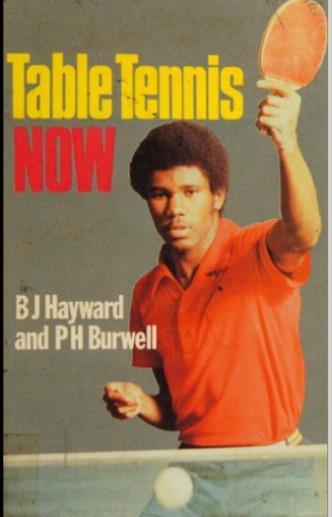

In TTC Issue 71, ten years ago, I thanked our colleague Barry Hayward of England for his help on an article about Arnold Parker’s 1902 book, and added, “Barry has perhaps the largest collection of table tennis books in the world, and his website www.tabletennislibrary.co.uk is the most complete table tennis bibliography, a great resource with summaries/reviews of over 350 editions.”

Recently, while seeking his new email address, I stumbled upon a 2021 interview Barry did with the Scotland TTA. You can watch it here.

The interview was all about his top-12 favorite table tennis books. Here they are, in order, along with some of his comments.

1. The Money Player, Marty Reisman, 1974. “An enthralling tale, well told”

2. Table Tennis Fascination by the ITTF, a ten-book series of photographic studies, 2001 through 2015. “Great photos wonderfully capture the excitement and explosive shots”

3. Ping Pong Fever: The Madness That Swept 1902 America, Steve Grant, 2012. “Fantastic anecdotes, yarns and factual evidence of how ping pong gripped the world in 1902”

4. Table Tennis with Timo Boll, by Timo Boll and German coach Bernd Ulrich Gross, 2018. “Brilliant text, photos and instruction”

5. Sizzling Chops and Devilish Spins: Ping Pong and the Art of Staying Alive, Jerome Charyn, 2001. “Hairraising tales, chronicles his love affair with table tennis”

6. Ping Pong: The Game and How to Play It, Arnold Parker, 1902.

“Important in popularizing the game, the best seller of those early years”

7. Twenty-One Up, Richard Bergmann, 1950. “Who else could have had a story like this to tell?”

8. Everything You Know is Pong: How Mighty Table Tennis Shapes Our World, Roger Bennett, Eli Horowitz, 2010. “Photos you’ve never seen before, a treasure trove of table tennis miscellany”

9. More Than a Match, Chester Barnes, 1969. “The story of the meteoric rise to success of Chester Barnes”

10. The Mighty Walzer, Howard Jacobson, 1999. “Very funny novel”

11. Ogi, Mitsuru Jojima, 2009. “Ogimura’s journey to becoming world champion, a very good read”

12. Table Tennis from Then Till Now, Rowden Fullen, 2020. Collection of instructional articles, lectures and seminars over many years.

For more details on any book, see Barry’s website at the address above.

In the interview, Barry was asked about the rarest book. He named How to Become a Champion at Table Tennis by the former world champion Miklos Szabados, 1954, published in Australia, which took him a long time to find. As to what new book he would like to see, he hopes a top Chinese player will write about their development, training regime and rules.

Fortunately, Barry gave his new email address at the end of the YouTube interview. I sent him the first issue of Table Tennis History and said I welcomed any article he might like to contribute. Some weeks later, he kindly sent the following (edited, by permission) about his early years in table tennis, becoming a coach and author, and collecting table tennis books

I was a member of the local church Boys Brigade, where we played a little table tennis. It was common practice to balance upright one of the old ten-sided threepenny-bit coins on each side of the table. The objective was not so much to score points but to knock over your opponent’s coin and thereby pocket both coins. Gambling? Well maybe, but it was certainly addictive. This was probably why, early on, I had very few real strokes. The one thing I did well was poke the ball over the net very consistently, leading to being a good retriever and not much else.

I left school when I reached age 16 and took a job as a commercial apprentice at Midland Counties Dairy. I owe them for giving me a useful start, which eventually led to becoming a Chartered Management Accountant. Much to my surprise, the Dairy had a snooker room to use during lunch breaks and a couple of unused and unwanted table tennis tables. A fellow apprentice, David Taylor, was as bad at snooker as I was, and it wasn’t long before we were snatching a quick sandwich and rushing to the table tennis room. The ‘Room’ was really a hallway used by staff going to lunch, who contributed a regular session of catcalls and sarcastic comments when David and I were trying to concentrate.

We were becoming reasonable players. One lunchtime a guy from the production lines came to watch. He introduced himself as Steve Faultless (I kid you not). He had played league table tennis in earlier days and could still handle himself pretty well. Wearing his working white overalls and Wellington boots, he picked up a bat and thrashed the pair of us quite comfortably. Steve was also a lovely man, and he showed us how to play numerous shots, spins and techniques we had never dreamt of.

I decided that table tennis was the game for me. My brief and mediocre performances at football and cricket were enjoyable but somehow did not give me craving for more, but table tennis did. We found another ex-player in the Cash Office and entered a league team. Over the next couple of years, our team moved upwards in the Birmingham League. I think it was in 1963 that we entered in a Cup match, and as luck would have it, we were drawn against Central YMCA, the top team in the Birmingham area. We were whipped 10–0, and although I played reasonably well I was out of my depth. But I did gain an invitation from the YMCA to come to some of their practice sessions. This became a real milestone for me and before long I was a regular there, practicing a few nights every week with the likes of Ralph Gunnion, Derek Backhouse, Derek Baddeley, Derek Munt, Ron and Paul Judd, Peter Astley, Glen Warwick and in later years even Desmond Douglas.

The Y became a focal point for TT in the Midlands. There were often visits to this Mecca of Table Tennis from Worcestershire, Staffordshire, Leicestershire and Derbyshire players. I have often been asked what was so special about the Central YMCA. Physically, nothing was special. The real attraction was that there were always good-quality players there, both to play and to advise you sensibly when things were not going as you wished. The Birmingham and District League was probably the biggest league in the UK. At that time there were North B’ham Leagues, South B’ham, West B’ham and East B’ham. There was a Birmingham Women’s League, Business Houses League, Three a Side League and Four a Side League, and each of these leagues had about five divisions. Table tennis in the early 1960s was an important local sport, organized by various committees under the guidance of Maurice Goldstein (who later became ETTA President and a CBE, honours richly deserved). How sad to find the current Birmingham Association reduced to one League, with only four divisions.

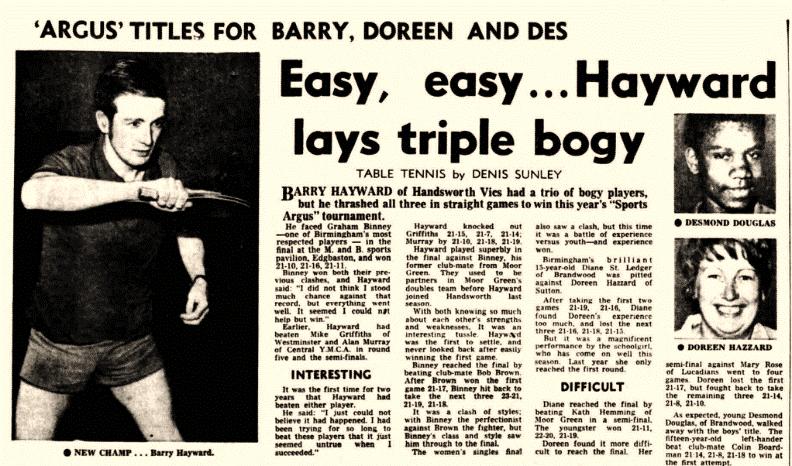

One of my treasured cuttings is an article showing a substantial photo of me and a small photo of Desmond Douglas, who had won Juniors. Des went on to become World No. 5, and when I saw him a couple of months ago I was able to remind him of the time when, for a little while, I had the headlines and he had only a mention. We are still good friends.

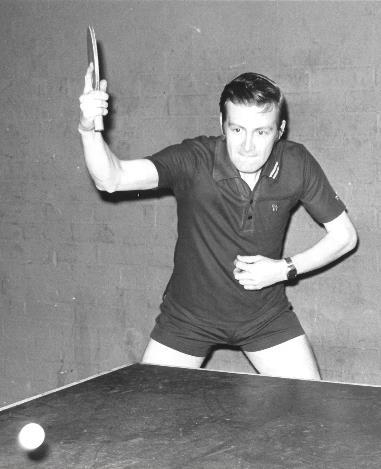

[I found the article you’re talking about, Barry! At left, from Sports Argus, July 10, 1971. Barry was a chopper, so this photo and the one above are uncharacteristic.]

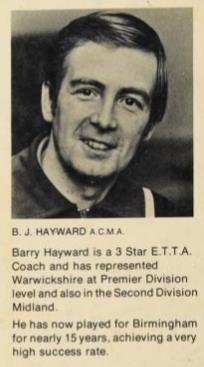

Table tennis took over my life. I graduated from being a mediocre league player to representing Birmingham and later the County of Warwickshire, and went on to win the County Men’s Singles title twice (1981 & 1982) and to play at the highest levels in the National League Premier Division. In my best year I managed to win 6 out of 12 singles playing at No. 1 for Warwickshire, including the scalps of England No. 2 and No. 6.

But my playing days were numbered. Because of my late start at the game, I was 36 years old at my best. My England Ranking of 31 was difficult to maintain. And there was the expense of playing equipment (not much sponsorship at No. 31) and travelling to matches that were often hundreds of miles away. I would not change any of my playing days. The pleasure, the friendships, the camaraderie, the joy of winning, were all a source of great memories that I will always treasure. There was of course also the frustration of losing, but let’s not talk about that.

There are times though, that I reflect over my career, when I took time off from studying, when I missed family occasions, when I took eight years to pass my Accountancy exams when it should have taken me only five years, and when my working life should have taken preference and didn’t. So somewhat reluctantly, I decided to close my playing activities and concentrate more on enhancing my coaching skills.

Coaching courses from Jack Carrington, the national coach, had a big impact on me. His enthusiasm for the game was infectious, and his knowledge and understanding of the game was immense. Jack decided me on trying to emulate the way he made the game fun. I always left a session with Jack feeling that his inspiration and passion for the game had done me the world of good. Eventually I did qualify as a 3 Star International Coach. I have great memories of my pupils and think I can claim to have helped five Junior Internationals to success, and perhaps some of my love for the game has rubbed off on the not so well known, too.

In 1977 the World Table Tennis Championships were held in my hometown of Birmingham, the first event at the new National Exhibition Centre. I was roped in by the local stalwart and ETTA President Maurice Goldstein [seen at left with Ivor Montagu] to assist with financial records. I was unable to see much of the play, but I did have the honour of meeting greats like Johnny Leach, Ivan Andreadis and Alojzy Ehrlich. One day, a gentleman entered the room, embraced Maurice Goldstein warmly, picked up a TT ball from the desk, tilted his head back and blew, keeping the ball in the air for about 15 seconds. ”Look Maurice, I can still do it,” he cried with a big grin on his face. After he left, Maurice told me it was just one of his friends, Laszlo Bellak, and that they had met at the Prague Worlds in 1936.

I had a brief chat with Phil Burwell, a fellow coach in the area, to discuss writing a TT book as a joint effort. We agreed that immediately the Worlds was over, I would go to local second-hand bookshops and buy a few TT books to learn about layout, style, photographs, etc. Little did I know the result that little conversation would have. I bought six books in the next few days, including Jack Carrington, Johnny Leach, Geoff Harrower, and Know the Game Series. We were a little disappointed in the quality of their photographs, which we thought should show more action. We put together an introduction and first chapter, and arranged a photoshoot using local International players. We were lucky to get Roland Roley, the chief sports photographer for the local paper, who was married to Jan Roberts, one of the best women players in Birmingham. We sent out our little package the Introduction, Chapter 1 and photos. The first four publishers

said no. The fifth would not commit but suggested we go ahead with more chapters. We did, and at last our book was in print with Kaye and Ward in 1978. We were pleased with the final outcome. It didn’t outsell Agatha Christie or Ian Fleming, but it did get good reviews in the Table Tennis magazine, and the Sunday Observer said it was ‘the definitive book of the Game.’ The book sold out of the 5,000 print-run quite quickly. It didn’t make us rich I doubt it even covered our costs but it gave us both a lot of self-satisfaction. [Photo at right is from the back of the book.]

Now, regarding those six books I bought, I have been a born collector, whether it be postage stamps, train numbers, Clint Eastwood DVDs or music albums. I thought ‘Oh well, there can’t be many more – let’s collect the lot.’ Well at the last count I now have about 362 and there are still a few that I have not yet found. I have had some good ‘finds,’ like the 1902 Parker book languishing in a bookshop just round the corner from the Castle in Nottingham, sporting a price of £7. Trying very hard not to show too much enthusiasm to the shopkeeper, I asked if this was his best price. He was most apologetic that it was, and for my part I could not push the money into his hand quickly enough and get out of the shop at top speed.

On my bibliography website, I include only books in the English language or in a few cases foreign languages with English translations. I do not include handbooks, programmes or result sheets of any kind. I am often asked if I have read all the books in the collection. I most certainly have, but there are a considerable number that I would not read twice. Others I may refer to frequently, for some fresh ideas, or inspiration, or simply the yarns and tales that are just good fun to read. Some of the old books are getting more expensive to buy. I noted this morning that one of the dealers had just auctioned off a copy of 1902 Clifford Bingham’s Ping Pong as Seen by Louis Wain for £720. Wow!

After a near lifetime in Table Tennis, I remain disappointed that the game that I love seems to have lost its way. I am convinced that the game was more fun under the old scoring system to 21. Unfortunately, the biggest change in England has been the declining number of playing venues. Almost all employers of a decent size had sports facilities in the 1950s and 60s, but not now. Most Civil Offices had their own Sporting Grounds and pavilions; this no longer happens. School facilities, which used to be available for a small fee, are now not suitable for evening matches because of the dreaded Health and Safety Regulations or the lack of someone in authority to lock up after the session, or the insurance cost. Yes, I am an old man, and I do moan like one, but it is all because I still love that wretched bat and ball. Table Tennis is still a great game.

Meanwhile, I always look forward to reading new table tennis books. At first, my collection expanded to take over one shelf in our bookcase at home. Sheila, my long-suffering wife, was very patient when I explained how one shelf was not enough space. Soon, even three shelves did not really provide enough room, and maybe a second bookcase ought to be considered. Now the second bookcase is nearly full. I suspect she has noticed this, but as yet negotiations for a third bookcase are only in the infancy stages.

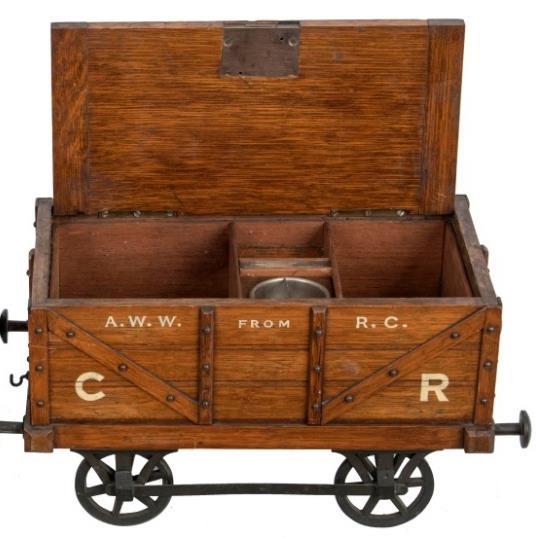

I am not the only person who likes small wooden boxes. When they are in the shape of a table tennis table, I like them even more. Table Tennis Collector showed several such boxes, and here I gather them and add a few more

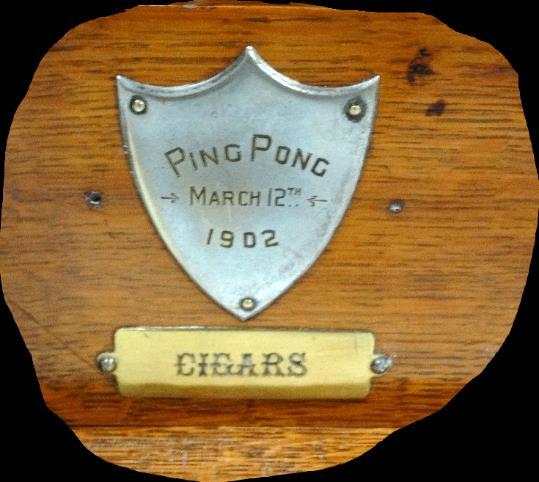

My favorite is easily this beautiful 1902 cigar box. It would have made a great tournament prize, with the shield on the front available for engraving.

It opens to reveal storage space and a match striker.

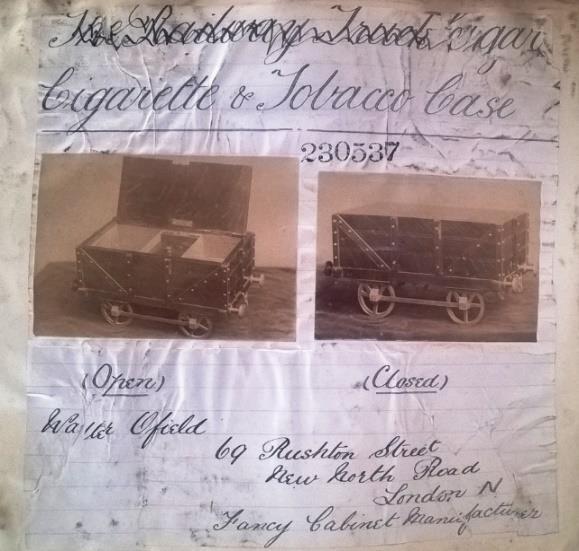

The box’s design registration was referenced by Gerald Gurney in Issue 40, page 16, and later shown (left) by Alan Duke in Issue 76, page 26. Note that the original corner brasses differ from the example we showed above. Also, the lids were later changed from center-hinged to the more attractive end-hinged. Walter G. Ofield, fancy cabinet manufacturer, was born in about 1846. In 1882 he described himself as a stationery case manufacturer. Founder and president of more than one philanthropic society in London, Ofield died in 1898. His son-inlaw, Frederick William Ring, son of a close Ofield friend, took over the business. Ring is named in the cigar box registration in 1902.

Ofield had been making unusual cigar cabinets for a while. In 1895 he presented one in the shape of a coal truck to the winner of a cycling race, according to a newspaper account. It must have looked very much like this registered design 230537, April 24, 1894, below. (Thank you to the editor of Train Collector, Nicholas Oddy of Glasgow, Scotland, for providing this.)

Probably very few of the Ofield ping pong boxes were made, but the little rail cars sold well. They were especially popular among train executives, who had them personalized for their particular rail line. A stationery cabinet variation (right) was registered in 1901 by F.W. Ring, trading as W. Ofield.

W. Ofield and Co. continued in the first years of the new century as ‘Wholesale Manufacturers of Stationery Cases and Cabinets, Paper Racks,

Cigar & Cigarette Cabinets &c., according to Mr. Oddy, but by the 1911 census the Rings had moved and Mr. Ring described himself as an actor.

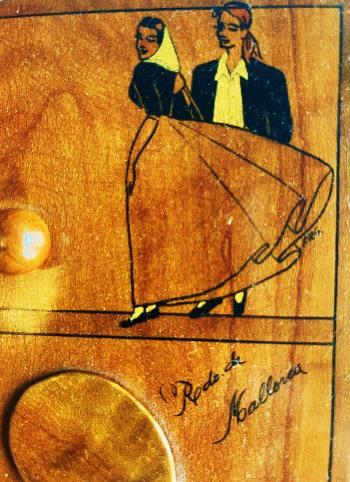

Moving decades into the future, we find another style of table tennis box, designed to tempt tourists at the popular Spanish island Mallorca. TTC Issue 38, page 7, shows this example, with an image of a lady sewing, dating to perhaps the 1950s. The Spanish writing translates “Souvenir of Mallorca.” Nice for storing sewing paraphernalia.

A very similar box has an image of two dancers instead. This is a music box that plays the popular Spanish song La Paloma.

The plain variation has no image on the table and no music.

This music box is a different design, with a one-piece lid instead of two-piece