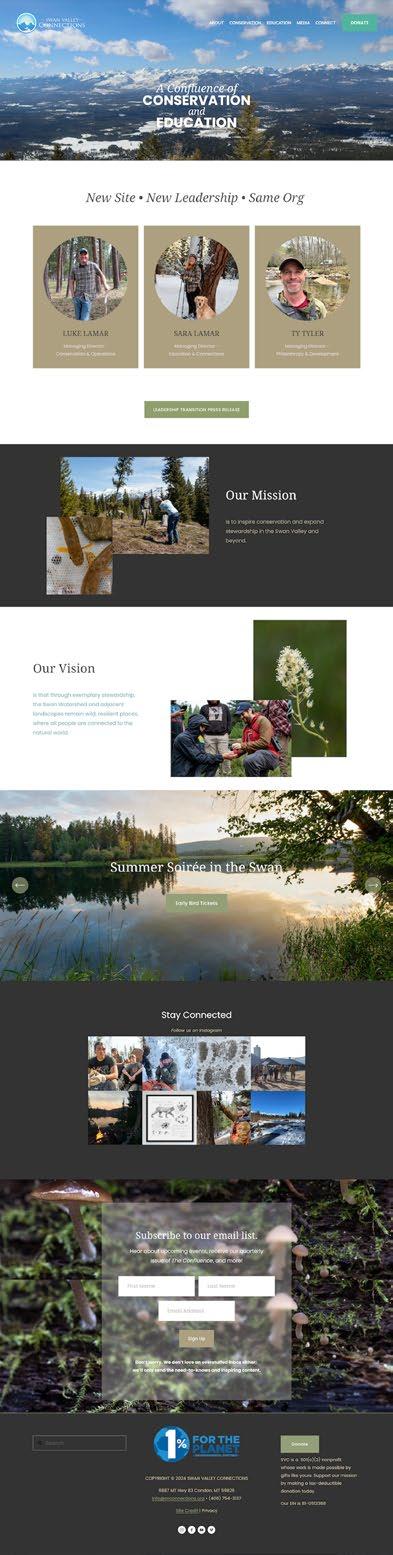

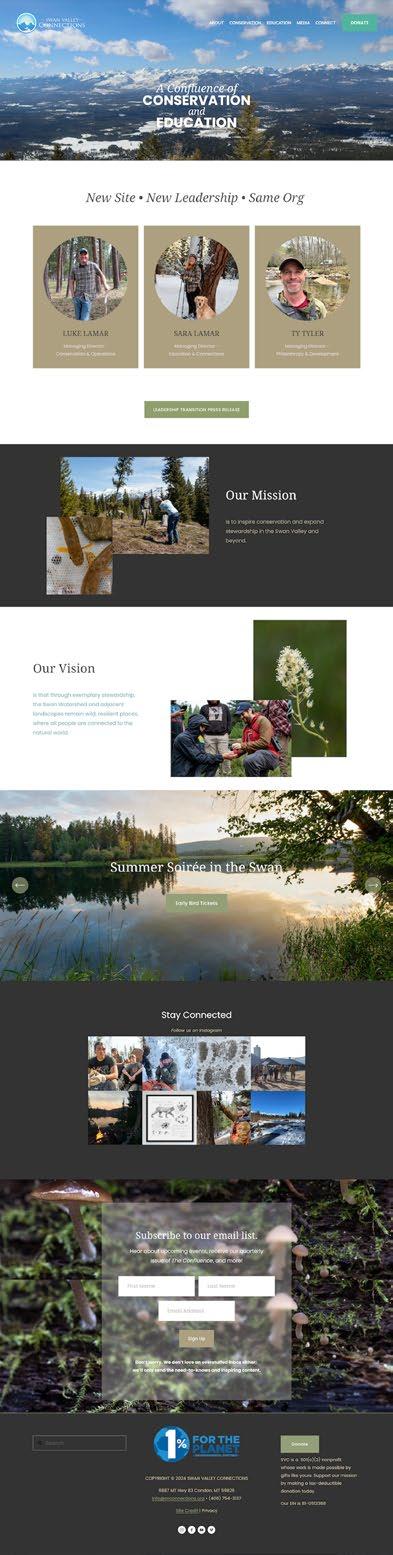

The Confluence

Spring 2024

Throughout my hiring process, Swan Valley Connections (SVC) board and staff would repeatedly ask, “What is it about SVC that pulls you in?” Beyond the simple beauty of the Swan Valley, the lure of Montanasized adventure, or even the potential to see some exciting wildlife, it was the dedication to collaboration that inspired me. SVC’s mission and values speak to this dedication, while our program work showcases our commitment to a network, an additive process where one organism works in conjunction with another to make big things happen. I love collaboration and although it starts slow and takes time, the results can be truly grand.

For the last 11 years, leading right up to the moment I joined the SVC team, I was more of a “desert rat,” spending the bulk of my time and work guiding collaborative stewardship and conservation efforts across the Southwest. It’s a region covered with one of our smallest natural, collaborative communities with far-reaching impacts: biocrusts. Biocrusts are a conglomerate of multiple organisms, including mosses, lichens, algaes, microfungi, or cyanobacteria, all living together, working side-by-side for survival and growth.

This consortium of life takes time (a lot of time) to grow and mature. Growth measurements aren’t based on growth rings, or inches per year, but more like crust thickness in millimeters over decades. Much like a sincere collaborative process, things start off incredibly slow, with almost invisible growth; early biocrusts simply harden the very top layer of soil. As collaboration grows, so does the biocrust community and the effects on its surroundings.

The positive impacts from biocrusts expand outward, first by protecting soils from erosion, preventing water from simply gouging out and washing away loose soils, and instead allowing water to propagate slowly into the soil. Biocrust populations also have a knack for preventing non-native/invasive species from taking hold by preventing germination and root establishment. These little collaborative groups hold nutrients in the soil, feeding native species the sustenance they need to outcompete invasives.

The results of this collaboration expand even further, having a huge impact on the global climate and water cycle. By holding dryland soils in place, biocrusts prevent the prevailing westerly winds from picking up soils and transporting them to the Rocky Mountain snowpacks, where they increase the speed at which those snowpacks melt – a real concern as drought conditions continue to grow across the West and Plains states.

So, here I am in Montana, a landscape generally void of biocrusts, but I’m no less enthralled with collaborative processes and their impressive impacts. Where can we find that micro world, leading to the macro in this region? Sara Lamar shared with me that in this ecosystem, it may lie within the world of slime molds….yup, slime molds.

Slime molds are another one of these microorganism worlds, with multiple entities working together to survive and excel in making a difference. Slime molds aren’t molds, or your typical fungus; they occupy a place in the taxonomic system almost alone, yet not lonely at all. Without a food source (the bacteria on decaying plant life), they sit as a lonely singlecell organism, almost in a state of hibernation. But once food is introduced, things start to happen — they call out to each other (maybe a Zoom invite?) and bring themselves together to coalesce as one around a common goal. They move like an amoeba, expanding their network, and continuing their consumption of bacteria and additional food sources. In essence, these individuals come together around a shared vision, working together to broaden their impact and excel at what they do best.

Swan Valley Connections

6887 MT Highway 83

Condon, MT 59826

p: (406) 754-3137

f: (406) 754-2965

info@svconnections.org

Board of Directors

Mary Shaw, Chair

Jessy Stevenson, Vice-Chair

Donn Lassila, Treasurer

Kathryn De Master

Rachel Feigley

Zoë Leake

Dan Stone

Rich Thomason

Aaron Whitten

Tina Zenzola Emeritus

Russ Abolt

Anne Dahl

Steve Ellis

Neil Meyer

Advisors

Kvande Anderson

Steve Bell

Jim Burchfield

Larry Garlick

Chris La Tray

Tim Love

Alex Metcalf

Pat O’Herren

Casey Ryan

Mark Schiltz

Lara Tomov

Mark Vander Meer

Gary Wolfe

Staff

Luke Lamar, Managing Director

Sara Lamar, Managing Director

Ty Tyler, Managing Director

Andrea DiNino

Kirsten Frazer

Mike Mayernik

Jackie Pagano

Uwe Schaefer

Taylor Tewksbury

The Confluence is published by Swan Valley Connections, a non-profit organization situated in Montana’s scenic Swan Valley. Our mission is to inspire conservation and expand stewardship in the Swan Valley. Images by Swan Valley Connections’ staff, students, or volunteers, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved to Swan Valley Connections. Change service requested. SwanValleyConnections.org

2

From the Director

Cover Image: Song sparrow in a willow Photo by Andrea DiNino

This micro world of coalescing cells, amoeba-like movement, and feeding silently influence the entire forest ecosystem, the entire planet’s ecosystem. Without slime molds feeding on the bacteria that breaks down the forests’ dead and downed plant life, our forests would not exist. Forests would not consume carbon dioxide, filter water, or feed wildlife. Instead, they’d simply be a mass of bacteria, poisoning everything around them. Slime molds not only feed on bacteria, they are critical in the recycling of nutrients, and they provide food to other small organisms and insects; thus, they are a foundation for the cycle of life…all this from tiny cells that come together with a common vision.

Swan Valley Connections, and similar watershed organizations, are the biocrusts and slime molds of the non-profit conservation ecosystem. We’re small in size, focused on working together for a common purpose, and investing our time, all (hopefully) leading to incredible reverberations that cross the grandest of ecosystems. So, in essence, that’s why I’m here. I’m here at SVC to play a role in that microorganism world of nonprofits, who lead and inspire the most audacious of visions for connection and stewardship. As the snow melts out and the world around us comes back to life, we hope you’ll join us in our shared goals and values this year, to make an even larger impact than we could accomplish alone.

We’re Better Together,

Ty Tyler, Managing Director- Development and Philanthrophy

Ty Tyler, Managing Director- Development and Philanthrophy

Welcome, Kirsten!

Below left: Fuligo septica, commonly known as scrambled egg slime, flowers of tan, or dog vomit slime mold. Photo by Henri Koskinen

Below: Lycogala epidendrum, commonly known as Wolf’s-Milk slime or toothpaste slime. Photo by Andrea

DiNino

We’re excited to welcome our new office manager, Kirsten Frazer, to the team!

Kirsten grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area and earned a bachelors degree in sociology from the University California - San Diego (UCSD). As an athlete in college, she played water polo for UCSD and has always had a love for sports and the water. Kirsten’s professional experience includes teaching, administration, management, and operations, with a focus on interpersonal connectivity and enrichment.

She’s been visiting Montana for years and has always felt a deep connection to the landscape, environment, and ecology. In May of 2022, she decided to follow her gut, pack her car, and make the move to live in Montana full-time.

Kirsten found Swan Valley Connections by discovering the wildlife tracking opportunities over a year ago. Following SVC on social media, coming to events, and recently participating in the Wildlife Tracks and Sign class, she is excited to be joining the team. She looks forward to sparking curiosity and helping others to see and experience this powerful connection to the natural world, believing this will lead to more conservation and a greater respect for nature.

Kirsten has a love for horses, swimming in a lakes, painting and drawing birds, studying herbs, wildlife tracking, and a warm cup of tea.

3

summary balance sheet

as of december 31, 2023

Annual Report

Summary Profit & Loss 2023

Swan Valley Connections’ executive committee oversees the fiscal management of assets, balancing long-term financial stability with current operational needs. The executive committee provides oversight for investment (through a professional investment manager) of fiscal assets to provide long-term growth, as well as current income within a balanced and appropriately conservative investment portfolio.

In addition, the executive committee recommends for approval, by the entire board of directors, an annual operating budget and the strategic allocation of unrestricted and board designated net assets to support the continuing mission of Swan Valley Connections.

4

Dec-22 Dec-23 ASSETS Current Assets Cash & Equivalents 709,741 522,286 Accounts Receivable 98,743 273,627 Inventory 11,125 9,711 Prepaid Expenses 21,390 15,697 Total Current Assets 840,999 821,321 Fixed Assets Equipment 6,459 15,139 Vehicle 112,730 115,230 Land 282,000 282,000 Accumulated Depreciation (96,563) (107,954) Total Fixed Assets 304,626 304,415 Investments 36,882 39,903 TOTAL ASSETS 1,182,507 1,165,639 LIABILITIES & NET ASSETS Liabilities Current Liabilities Accounts Payable 26,598 7,335 Payroll Liabilities 67,264 68,124 Tuition Deposits 21,326 19,660 Other Current Liabilities 3,625 0 Total Current Liabilities 118,813 95,119 Long Term Liabilities Loans 47,338 46,056 Total Long Term Liabilities 47,338 46,056 Total Liabilities 166,151 141,175 Net Assets Unrestricted Net Assets 684,198 672,837 Board Designated Net Assets 208,394 208,394 Temporarily Restricted Net Assets 89,215 108,684 Permanently Restricted Net Assets 34,549 34,549 Total Net Assets 1,016,356 1,024,464 TOTAL LIABILITIES & NET ASSETS 1,182,507 1,165,639 Page 1 of 1

Revenue: 2022 2023 Government Agency Grants & Contracts 934,163 410,168 Tuition & Course Fees 72,497 122,704 Private Foundation & NGO Grants 179,258 196,169 Donations 282,876 275,048 Program Services, Events & Other 105,056 109,839 Investment Income/(Loss) & Interest (900) 22,379 Total Revenue 1,572,950 1,136,307 Expenses: Stewardship & Restoration 757,497 267,115 Education 160,048 204,782 Wildlife & Aquatics 181,330 125,245 Recreational Trails 66,114 68,283 Outreach & Communications 64,080 101,790 Public Info & Visitor Services 50,248 68,122 Conservation 17,563 23,681 Elk Creek & Swan Legacy Forest Mgmt 5,390 5,037 Total Program Expenses 1,302,270 864,055 Administration & Fundraising 221,502 252,752 Depreciation 19,004 11,391 Total Expenses 1,542,776 1,128,198 Net Surplus/(Deficit) 30,174 8,109 Other Income: Total Change In Net Assets 30,174 8,109

0 100,000 200,000 300,000 400,000 500,000 600,000 700,000 800,000 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 Sources of Operating Income Gov't Agency Grants (Excl. Cost Share Grants & Pass Through) Non-Gov't Agency Income

2023

landowners served and projects completed with svc

FUELS REDUCTION

10 projects

182 acres

35 bear-resistant trash cans 3 electric fences

Land stewardship

85 landowners

2,609 acres

Beetle Repellent

182 landowners 10,030 packets

2023 revenue

2023 Revenue

Interest & Investment Income, 1.97%

Other Operating Revenue, 9.67%

Donations & Sponsorships, 24.21%

Tuition & Course Fees, 10.80%

Gov't Agency Grants & Contracts, 21.26%

total

315 landowners + projects 2863 acres managed

Gov't Agency Grants Passed Thru to Private Landowners, 14.83%

Foundations & NGO Grants, 17.26%

2023 operating expenses

2023 Operating Expenses

Operating Expenses & Fundraising, 22.63%

Elk Creek & Swan Legacy Forest Management, 0.45%

Education, 18.34%

Community Outreach & Visitor Services, 15.21%

Stewardship & Restoration, 23.92%

Conservation, 2.12%

Wildlife & Aquatics, 11.21%

Recreational Trails, 6.11%

5

For the Love of Lynx celebrating scott tomson

By Michael Mayernik

I remember the first lynx track I ever saw, and the day surrounding it, like it was yesterday. It wasn’t far from Seeley Lake, on a snowy January day in 2011, and I was a newbie wildlife technician, fresh out of college and working for the U.S. Forest Service (USFS). My supervisor, Scott Tomson, a wildlife biologist on the Seeley Lake Ranger District, was taking time from his busy schedule to take me out for a practice run on the snowmobiles and give me a lesson on wildlife tracks. As a first timer on a snowmobile, I struggled to keep up with Scott, as I got my sled stuck and tipped it over more than a few times. Scott was patient with me and graciously offered lots of tips that he had gained from years of experience in the field.

Eventually, we came up to a track that was different from those of the deer, elk, squirrels, and snowshoe hares that we had been seeing all morning. Scott pulled out a yellow tape measurer and gathered the dimensions of the direct register walk, or gait pattern in which a hind foot lands directly on top of a front foot, that we were looking at; it had a stride of 32” long and a straddle of 7 ½” wide. As we trudged in the thighdeep powder, this track appeared to only sink in a few inches. Scott reached into the snow, and from below popped up the form of the 4” x 4” track that the animal’s foot had compressed in the snow…we were looking at my very first set of Canada lynx tracks! Little did I know at the time, I would become very familiar with this track over the next 14 consecutive winter field seasons I’d work on the rare carnivore project, continuing Scott’s (and others’) efforts. I went on to work for Scott and the USFS for seven more years; not only did he become a good friend, he’s also been an important mentor for me in my career and life.

Scott Tomson retired in December 2023 after a 30-year career in natural resources and wildlife management. I had the chance to sit down with him the other day and talk about his memories from a career and life in the field.

Scott grew up in Vincennes, Indiana and went to college at DePaul University, graduating with a degree in earth science in 1988. The following year he decided to take off on the first of many adventures, and left the states for an opportunity with the Peace Corps in the Philippines.

Upon returning to the United States, Scott and a friend hitchhiked from California to Indiana, where he loaded up a vehicle and headed back out west. He had always wanted to live in Montana and happened to have a friend who was working in Choteau for the USFS, so he drove himself to the Rocky Mountain Front and was offered work with the USFS doing stand exams, firefighting, and various other jobs for several seasons. During this time, Scott decided to go back to school to study wildlife biology at the University of Montana (UM) in Missoula and earned his bachelor’s degree there in 1991. He then continued his studies and went on to earn a master’s degree after researching pine marten through Idaho Fish and Game in north Idaho, where he live-trapped and radio collared the weasel species to learn about their habitat use.

For the next few years Scott worked on a variety of projects and for a number of entities, including the Owl Research Institute, Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks – Block Management Program, and a black bear study in New Mexico, before returning to his favorite state. In 1997 he excitedly returned to the Seeley Lake area to work on a new project studying Canada lynx for Dr. John Squires, researcher for the USFS Rocky Mountain Research Station. This was the timeframe when lynx were being listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act, and not a lot was known or understood about the species in Montana. Scott was one of the original core crew members of the Lynx Project. He and the rest of his team live-trapped, collared, tracked, and studied these elusive felines to help others make informed management decisions.

He worked on this project, which had added another focal species (wolverines) into the scope of work, for two years before he took another wildlife biologist position with the Bureau of Land Management and made a temporary home in Medford, Oregon. There, he worked with many different Pacific Northwest species, including spotted owls, a species that was listed as “threatened” in 1990. (Spotted owls began declining due to habitat loss from logging, wildfires, and barred owls.)

In 2001 Scott returned to Seeley Lake for good, when he was hired by USFS District Ranger Tim Love as the East Zone Wildlife Biologist for the Seeley Lake Ranger District on the Lolo National Forest. He went on to work in this position until his retirement at the end of last year. Given his impressive resume, I wanted to know what some of the highlights were that Scott was most proud of during his 22-year career in Seeley Lake.

6

One such memory was his participation in the large land conservation projects that have happened in this area, the most prominent of those being the Montana Legacy Project. This project consisted of The Nature Conservancy and the Trust for Public Lands conserving over 310,000 acres of Plum Creek Timber Company lands from development, and transferring them to federal, state, or private ownership; a large portion of these lands are in the Swan, Clearwater, and Blackfoot Valleys. Scott remembers long meetings and energetic late nights of collaboration with stakeholders during this time.

In addition to that, throughout his time in Seeley, Scott had the challenge and privilege of helping to manage and protect various threatened or endangered species, aiding in their recovery. Working with grizzly bear manager Jamie Jonkel, and the various partners involved in grizzly bear recovery and management, was another career highlight.

And, of course, circling back to where this article began, participating with the various partners, including SVC, in the Southwest Crown of the Continent Carnivore Monitoring Project was an experience that Scott will always cherish. Since 2012 this project has been critical in monitoring and learning about lynx and wolverine, as well as pine marten, bobcat, wolf, and mountain lion, in the Swan, Clearwater, and Blackfoot valleys. Scott was a major contributor in designing the project, finding funding, and being the spark plug that kept that project going.

Working with John Squires on lynx conservation in northwest Montana was a high point for Scott, and he continued to contribute to the USFS Rocky Mountain Research Station Lynx Project through his role as a District Wildlife Biologist in Seeley Lake.

During his incredible career, and in addition to his wildlife work, Scott was involved in firefighting, fire management, and agency administration for many small and large wildfires throughout the Lolo National Forest. A highlight in this area of work was his participation in the various proactive USFS wildfire risk reduction projects, such as the Seeley Fuels, Auggie, Horseshoe, and Colt Summit projects. These projects all had aspects of forest restoration, prescribed fire, and forest thinning, designed to reduce fire risk to communities in the Seeley Lake area. Scott was able to see the direct effects of some of this work last summer. The Colt Summit Project thinning and fuels reduction activities proved critical in allowing firefighters to safely and effectively prevent the 2023 Colt Fire from burning into the neighborhoods situated along Hwy 83 between Summit Lake and Lake Alva.

Over the years, Scott has been on several boards for various organizations, including the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation – Project Advisory Committee, Clearwater Resource Council, Northwest Connections, and Swan Valley Connections for several terms. Scott has been extremely generous with his time and has always been willing to meet with and talk to students from SVC’s Wildlife in the West college field course. The class covers threatened and endangered species in Montana, including Canada lynx. Scott has long been a go-to resource for this part of our course, as are very few people in Montana, or in the Northern Rockies for that matter, that know more about lynx than he does. He graciously shares his knowledge with these future conservationists, as well as what it’s like being a wildlife biologist for the USFS.

We’ll miss Scott’s direct involvement as a USFS wildlife biologist in driving lynx and wolverine research and monitoring work in the Swan and Seeley Lake areas, but we know that he’s just a phone call away if we need him for advice. Scott will be easing into retired life by doing some part-time work for the Clearwater Resource Council as the Terrestrial Program Director. His primary role will be working with private landowners on cost-share fuels reduction grants, which is similar to my position with the SVC Forest Stewardship program. Otherwise, Scott will be enjoying retirement and working on projects around his home here in Condon.

From all of us at SVC, we thank Scott for all he’s done for the conservation of the natural resources, wildlife, and the wild places in the Seeley-Swan and beyond. I’ll always remember that first lynx track Scott showed me on a snowy day outside Seeley Lake. I’ve learned a lot since then, and now I have the great privilege of showing many other people their first lynx tracks, passing on what I first learned from Scott, and patiently digging out new field tech’s snowmobiles…I don’t get mine stuck too often anymore.

7

Opposite page: Scott Tomson and Mike Mayernik out on the rare carnivore project

Above: Scott and his beloved sidekick Sunny (when she was just a pup) at his home in Condon.

2023 photo year in review

weeklong wildlife tracks & sign course wildlife tracks & sign class tree planting workshop on elk creek conservation area

wildlife in the west • stream ecology

fall grizzly tracks

montana master naturalist course

bigfork elementary campout

swan valley bear resources • electric fencing project

weeklong wildlife tracks & sign course wildlife tracks & sign class tree planting workshop on elk creek conservation area

wildlife in the west • stream ecology

fall grizzly tracks

montana master naturalist course

bigfork elementary campout

swan valley bear resources • electric fencing project

rare carnivore monitoring • lynx tracks

pile burning workshop on elk creek conservation area

bigfork elementary • animal wonders presentation

4th-annual summer soirée in the swan • the nest

cybertracker specialist certification

board and staff retreat • gordon ranch

mission mountains youth crew photo by alex kim

wildlife tracks & sign college course

rare carnivore monitoring • lynx tracks

pile burning workshop on elk creek conservation area

bigfork elementary • animal wonders presentation

4th-annual summer soirée in the swan • the nest

cybertracker specialist certification

board and staff retreat • gordon ranch

mission mountains youth crew photo by alex kim

wildlife tracks & sign college course

Chasing Sno:

The winter of 2024 will be remembered as one of the driest winters on record for Montana. According to the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS), the average statewide snow water equivalent (a measure of how much water is in our snowpack) was only about an inch above the 30-year-average record low in March. In the Mission Mountains of the upper Swan River watershed, the snow water equivalent was 36% below average. These conditions aren’t a complete surprise, as forecasters predicted that El Niño climate patterns would impact our winter weather. El Niño is a term used to describe the weakening of trade winds that normally move warm air across the Pacific Ocean. Without those powerful trade winds, the warm air moves east, leading to warmer and drier weather across the northern U.S and Canada. While El Niño is a natural, temporary phenomenon, climate change has increased the frequency of these weather patterns.

The Montana Climate Assessment (MCA) found that between 1950 and 2015 winter temperatures increased by 3.9°F (2.2°C) and winter precipitation decreased by 0.9 inches (2.3 cm), partially due to an increase in El Niño events. Looking ahead, the authors of the MCA predict that “the state of Montana is projected to continue to warm in all geographic locations, seasons, and under all emission scenarios throughout the 21st century.”

As I look out across the bare forest floor, I can’t help but wonder, how does this declining snowpack impact our winteradapted wildlife? This question is largely unanswered for snowdependent species such as Canada lynx and wolverines, but researchers can shed light on one specific adaptation for living in snow environments: the ability to turn white in the winter.

Montana is home to six species that molt seasonally to match their environment: white-tailed ptarmigan, white-tailed jack rabbits, snowshoe hares, and long-tailed, short-tailed, and least weasels. (Fun fact: wolverine kits are born white, but their coats start to darken at six weeks.) In the Swan watershed,

snowshoe hare and the three weasel species are the most prominent. You’ve likely encountered the tracks of snowshoe hares, aptly named for their enormous hind feet that enable them to easily bound on top of deep snow. Even though they are abundant throughout western Montana, their excellent camouflage makes them difficult to see unless they are moving. This year, however, you may have observed a white hare glowing like a neon sign in a dark room against the brown, snowless ground. We often refer to them as the “Snickers bars of the forest,” because of all the other animals that prey upon them. To avoid all of these predators, snowshoe hares freeze when they encounter a possible threat and rely on their camouflage to hide, rather than retreat to a burrow like most other lagomorph (rabbit and hare) species. The shift of their fur color from brown to white is linked to the photoperiod, or change in daylight. As the climate and snowpack changes, but the photoperiod remains the same, snowshoe hares and other animals that seasonally change color are stuck in a “phenological mismatch.” This leaves researchers asking, can the snowshoe hare adapt to a changing environment?

10

the hairs o the hare ’ s bck

by Sara Lamar

Dr. Scott Mills, a wildlife biologist at the University of Montana, has studied snowshoe hares for over a decade. Mills found that hares did not behave differently when mismatched in dangerous situations, suggesting that they will not adapt their predator avoidance strategy. As you can imagine, this drastically changes the likelihood of a snowshoe hare being caught by a predator. In fact, researchers found that hares have a 7 percent higher chance of being killed for every week that they are mismatched with their surroundings. If they are unlikely to change their behavior, can they change their coats? Maybe, say researchers. There are populations of snowshoe hares where some individuals molt to winter coats and some stay brown. These “polymorphic” populations have the greatest opportunity for snowshoe hares to adapt; individuals who mismatch their environment will likely be eaten, and those who match will more likely survive and pass on their genes to the next generation. Hares also may have some flexibility in changing the timing of their color transition, also known as “phenotypic plasticity.” However, they will probably not be able to change at the same rate that the climate is changing. All in all, there might

be hope for hares and other seasonally molting animals. This is tentatively good news, as in the areas Dr. Mills has studied, snowshoe hare molting is only mismatched by a week or two. Predictions indicate this mismatch could be off by as much as eight weeks by 2050, which could lead to rapid population decline, based on the increased predation statistics mentioned above. A steep decline in snowshoe hares would ripple across the forest, as so many other animals depend on them for food. The relationships between seasonal color-changing animals and the other species they impact has not yet been studied, but is an important next phase of this research. In our small part, Swan Valley Connections continues to work with partners to monitor and study Canada lynx, a threatened species, whose fate is closely tied to climate change and snowshoe hare. In fact, a study in northwest Montana found that snowshoe hares made up 96% of a lynx’s diet. In comparison, the second most common prey species of lynx was red squirrels, but they only made up 2% of the lynx’s total diet. Ongoing research around lynx and hares will be key in identifying conservation strategies to ensure these Snickers bars, and those who eat them, are here to stay.

Visit https://www.umt.edu/mills-lab/ to learn more about Dr. Scott Mills’ work

Above: “Seasons” | Snowshoe Hare by Brittany Finch, a Montana-based artist who makes beautiful illustrations inspired by the intricacies of the natural world.

This past March, Britt donated 50% of her sales to SVC! You can check out her artwork at www. brittanyfinch.com or grab some of her cards in our SVC Shop

Left: A mismatched snowshoe hare stands still in the Swan this spring, hoping the nearby threat (Andrea DiNino with a camera) won’t notice it.

11

Canadalynxtracks

What We’ve Learned

A Reflection on a Decade of Rare Carnivore Monitoring across the Southwestern Crown of the Continent Landscape

By Luke Lamar

Mike Mayernik and I pulled our snowmobiles to a halt on a snowy road high on the Swan Front. In the middle of the road was a freshly killed mule deer from the night before. Only coyote and wolverine tracks surrounded the scene. What transpired next was one of the most fascinating backtracks I’ve ever experienced. After climbing several hundred yards up the steep ridge, Mike and I found where the yearling mule deer buck had come bounding (a “pronk” would actually be the correct terminology to describe its gait pattern) out of a clump of trees. Along its side in the deep powder were the tracks of a wolverine, in its characteristic pattern of two tracks diagonal to the direction of travel. A little further down the hillside, there were no more wolverine tracks, just those of the mule deer. A little further still was the first tuft of hair, followed by many more clumps, as the story written in the snow continued to develop.

The tracks of the mule deer became so erratic that I could almost envision the deer bucking wildly, trying to rid itself of the wolverine riding its back, much like a bronco at a rodeo trying to lose the cowboy. This continued for a couple hundred yards down the slope, nearly to the road, when suddenly the first sign of blood stained the snow. From the spot where blood initially hit the snow to where the mule deer succumbed to death was only 50 yards, and there was a gushing blood trail to follow. At some point during the ride, the wolverine was able to not only latch on to the deer, but was able to deliver a lethal bite to the spine in the lower neck, which was evident after Mike and I performed a necropsy on the deer. The wolverine must

have experienced a rough lift down the ridge, as it shook off close to the dead buck, leaving about 20 hairs for us to collect and send to the lab for genetic analysis. This was a gift, as we often travel for miles following the trail of a wolverine without them shedding a single hair. The DNA from those hair follicles later told us that this was a female wolverine, affectionately known as F5, and whom we had first detected about 40 miles away, north of the town of Lincoln.

The scene was a fascinating glimpse and learning experience into the mysterious life of a wolverine and its relatively unknown behaviors. As the years went by, we learned more interesting behaviors as we followed wolverines, as well as other rare carnivores like Canada lynx, around the 1.5-millionacre Southwestern Crown of the Continent (SW Crown), an area roughly twice the size of Rhode Island. From 2012-2022 Swan Valley Connections (SVC), along with valued partners, including the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), Rocky Mountain Research Station, Bureau of Land Management (BLM), the Nature Conservancy (TNC), University of Montana, and the Blackfoot Challenge, were involved in a long-term monitoring project aimed at documenting a baseline of wolverine and Canada lynx distribution and minimum abundance within the SW Crown, as well as tracking changes over time.

We’ve learned that by monitoring these rare carnivores, we can provide the best available science that helps inform adaptive management of the species. After all, we can’t conserve a species if we don’t know anything about it. For example, when we first started this project, a person could still legally trap one

12

Lynx sit spot

fisher in the SW Crown. After several years of finding no fisher in the area, Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks adjusted that quota to zero. At SVC we are a non-advocacy organization. We don’t advocate for or against wolverines or lynx to be listed on the Endangered Species Act (ESA). We do, however, advocate for the best available science to inform the decisions made on whether to list these species or not. Therefore, we were more than willing to provide our data to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) as part of their data calls to help guide recent decisions on whether to list wolverines on the ESA and/or to delist lynx. In November 2023 the USFWS announced its ruling to list the distinct population segment of the North American wolverine in the contiguous U.S. as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act. The next time we find the trail of a wolverine, it will be under new protections and meaning.

We’ve learned much about the minimum abundance of wolverines and lynx across the SW Crown. For example, when we first started this work, no one had a clue how many wolverines we had across the landscape. From 2012 through 2022, field crew members worked to survey and record 622 wolverine track locations as part of the landscape-level monitoring project. Of course, each track location wasn’t a unique individual. Over the project’s timeframe, we collected genetic material and documented 61 unique individual wolverines (32 males, 29 females), with a maximum of 20 individuals detected in a single year. The SW Crown genetic dataset was also used to inform a broad scale study that shows an underlying pattern of decreasing genetic diversity in wolverines and increasing fragmentation from the north in Canada to the southern extent of wolverine range in the U.S.

We also documented 1,404 lynx track locations that ended up being 109 unique individual lynx (67 males, 42 females), with a maximum of 45 individuals in one year.

We’ve learned that when we first started this work, it was rare to detect a lynx across most of the Swan Valley. In 2021 we suddenly had an influx of lynx in this area, which was a surprising shift in their distribution. We also saw an interesting trend of lynx utilizing the thick tree and shrub regeneration of wildfire perimeters about 15 years post-fire, which has led to

additional, new research opportunities that SVC and partners have embarked on in 2023 and 2024.

Based on previous research, we know that there used to be a reproductive population of lynx in the Garnet Mountain Range in the early 2000s. Through our work we know that despite an occasional detection of an individual lynx some years, there is unfortunately no longer a reproducing population in the Garnets. While population recovery strategies are implemented, will lynx return to the Garnets? If no one looked, how would we ever know?

Another interesting and unintended finding that has come from this research is related to our pine marten population. Through the collection of genetic material, we learned that the SW Crown is home to two different species of pine marten– American marten (Martes americana) and Pacific marten (Martes caurina)– which has also led to additional research opportunities.

We learned that people really care and are curious to learn about these rare species. The Swan Valley Community Hall has offered standing room only each year when we’ve presented our data and results with the public. And, information about the project has reached a much wider audience, as it’s been published or shared by National Geographic, PBS, BBC, Montana Public Radio, The Missoulian, The Daily Interlake, and others. Looking back on our project’s trail over the past decade, I’m proud of where it has led. I’ve learned so much more about these rare carnivores by tracking and following them around in the woods. I’ve gained an understanding of their life histories and needs, and with that knowledge, have gained an appreciation for the conservation of these species. I feel confident that other field crew members would say the same.

A total of 39 field technicians gained valuable field experience to help catapult their careers in natural resource management and help grow the next generation of conservation leaders. Many of these techs were employed by SVC and diligently tracked these rare animals across the landscape year after year, often through blizzards and other

13

Opposite page: Sara Lamar backtracking a Canada lynx in the Mission Mountains, as part of the Rocky Mountain Reserach Station project looking at lynx’s use of post-wildfire landscapes.

Right: A remote camera trap photo of a Canada lynx from early carnivore project days. Photo by Steven Gnam

*This image is available to purchase as a print in our SVC shop!

inclement winter weather. Their goal was to collect genetic material (hair, scat, urine, vomit, hairballs, etc) that could be analyzed by the National Genomics Lab in Missoula, Montana to verify species and document sex and unique individuals. It is extremely gratifying to see where some of these technicians have ended up in their careers since working on the project.

This effort could not have been completed with just one entity alone; it took a group of partners working collaboratively to leverage resources and expertise. It also makes me proud that additional partners have joined our efforts over the timeline of the project. When the project first began, it was largely the USFS and SVC, but over time other interested entities joined the endeavor and have grown to include the BLM, TNC RMRS, and the Blackfoot Challenge. BLM and TNC, in addition to the USFS, partnered with us to better understand the distribution and abundance of these rare species on lands they manage, and to inform and adapt management activities and strategies in those areas.

We’ve advanced the world of science, refining methodologies that combine snow track surveys and bait stations to collect genetic material and data for multiple species at the same time, gaining survey effort efficiency and effectiveness, while minimizing costs. For example, our data shows that collecting genetic material from lynx by doing snow track surveys and backtracking them is far more effective than trying to get the same from non-invasive bait stations. Interestingly, the opposite is true for wolverines.. By using both methodologies we’re able to collect genetics from multiple species.

Reflecting on many blinding blizzards, nearly frozen fingers and toes, buried and broken-down snowmobiles, snowshoeing in deep, wet snow on steep sidehills, following wolverines up and over one lung-busting ridge after another, changing blown trailer tires in feet of powder after dark, icy beards, and ripe roadkill creates a long and winding trail in my mind. Despite the many rough times (which in hindsight hardens us to persevere through tough times and grow as individuals), there is an interwoven mix of the good people who have shared in the experiences, laughter, fascination, sunny days in snowcloaked mountains, seeing that first lynx, a wolverine riding on the back of mule deer, curiosity, and an insatiable thirst for learning.

I’m already looking forward to what the next wolverine will show me over the following ridge…

SVC has written and compiled a comprehensive report from the 2012-2022 monitoring effort and results, which can be found at www.swanvalleyconnections.org/rare-carnivores

14

Above: Fresh Wolverine tracks in the snow near one of our bait stations

Right: Luke Lamar and carnivore field technician Shane Lisowski replenish a bait station with roadkill deer

We did some major spring cleaning (starting in spring of 2023, actually), and we’re so excited to finally share our updated website! Buy early bird soirée tickets, check out the new Rural Pearl cards in our shop, take a peek at our wildlife video pages, and more!

Summer soirée in the Swan Sunday, August 25th

3PM-6:30PM

The Nest on swan river • Ferndale, Montana

FOOD: Forage MT

DRINKS: Glacier Distilling

LIVE MUSIC: Jessie Thoreson & the Crown Fire SILENt & ONLINE AUCTIONS

thankyoutoourcurrent event sponsors

Get your tickets at www.SwanValleyConnections.org/summer-soiree-in-the-swan

Upcoming Events

Always check our website for more details and the most up-to-date information

May 1

Adopt-a-Highway and Grounds Cleanup Volunteer Opportunity!

May 1-31

*Change Your Pace Fundraiser with Seeley Lake Community Foundation

May 2-3

CyberTracker Specialist Certification (FULL) with David Moskowitz and Michelle Peziol

May 2-3

Missoula Gives Annual Fundraiser

May 4-5

CyberTracker Standard Certification (FULL) with David Moskowitz

May 6 e-Bird Workshop

May 11

Global Big Day Bird Count

May 20-June 29

Wildlife in the West College Field Program

May 21

Tree Planting Workshop w/ MT DNRC on the Elk Creek Conservation Area

July 24

Insects & Disease workshop w/ MT DNRC on the Elk Creek Conservation Area

July 24-28

Queer Nature Wildlife Field Skills Course (FULL)

15

6887 MT Hwy 83 Condon, MT 59826-9005 CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED Non-profit Org. US Postage PAID Permit No. 151 Great Falls, MT PRSRT STD US Postage PAID Permit No. 151 Great Falls, MT www.SwanValleyConnections.org

Ty Tyler, Managing Director- Development and Philanthrophy

Ty Tyler, Managing Director- Development and Philanthrophy

weeklong wildlife tracks & sign course wildlife tracks & sign class tree planting workshop on elk creek conservation area

wildlife in the west • stream ecology

fall grizzly tracks

montana master naturalist course

bigfork elementary campout

swan valley bear resources • electric fencing project

weeklong wildlife tracks & sign course wildlife tracks & sign class tree planting workshop on elk creek conservation area

wildlife in the west • stream ecology

fall grizzly tracks

montana master naturalist course

bigfork elementary campout

swan valley bear resources • electric fencing project

rare carnivore monitoring • lynx tracks

pile burning workshop on elk creek conservation area

bigfork elementary • animal wonders presentation

4th-annual summer soirée in the swan • the nest

cybertracker specialist certification

board and staff retreat • gordon ranch

mission mountains youth crew photo by alex kim

wildlife tracks & sign college course

rare carnivore monitoring • lynx tracks

pile burning workshop on elk creek conservation area

bigfork elementary • animal wonders presentation

4th-annual summer soirée in the swan • the nest

cybertracker specialist certification

board and staff retreat • gordon ranch

mission mountains youth crew photo by alex kim

wildlife tracks & sign college course