“Draw what you like, draw what you know” –Marshall Arisman

I still have that copy, but I didn’t think that I was going to be a children’s book creator, or that it was even a career. I did take one children’s book class when I was a junior with Yumi Ha. During that class, I learned how to make a dummy book for the first time, and she taught us about how to submit to publishers. I continued working on children’s book art in my thesis year and after I graduated. After graduation, I did research and I dropped off my portfolio with publishers. But there was nothing solid coming out of it because my work wasn’t very strong.

STEPHEN: That always happens. You have to start at the bottom. You have to start with nothing to show or nothing of quality, and people have to say you’re not there yet—you don’t have anything yet.

ARAM: You know that’s so hard to hear. And I don’t mean hard to hear emotionally, but no professional would say that because no one is that invested in you, to tell you the truth. No one wants to be a bad person and say, “Hey, your portfolio is not good enough. You have to improve yourself.” Something which is so important, but it’s really hard to find anyone who would tell you that.

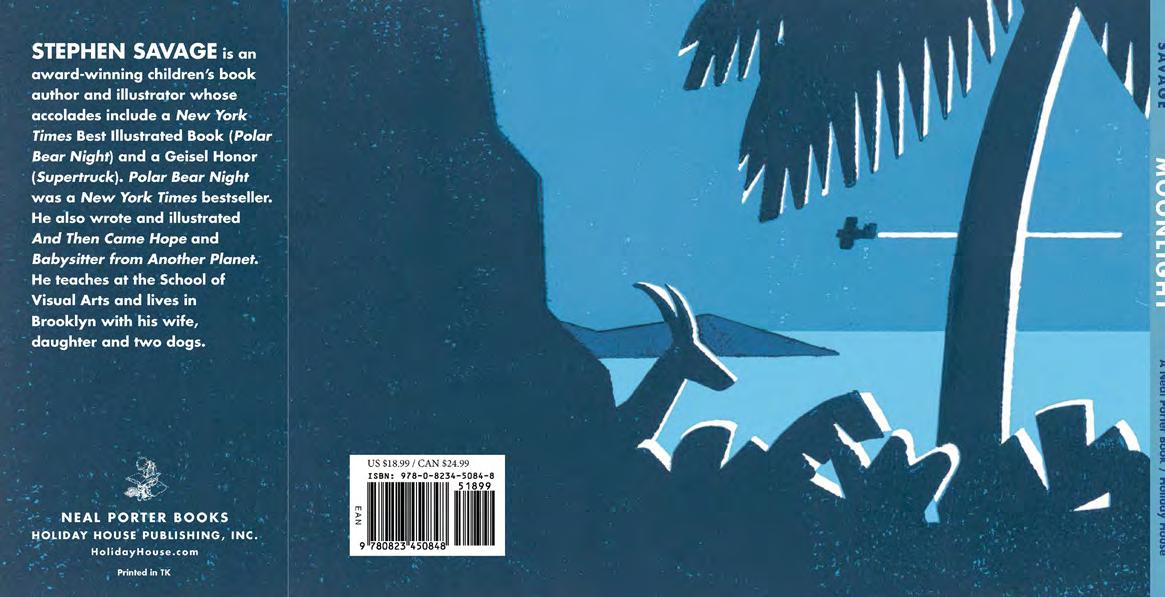

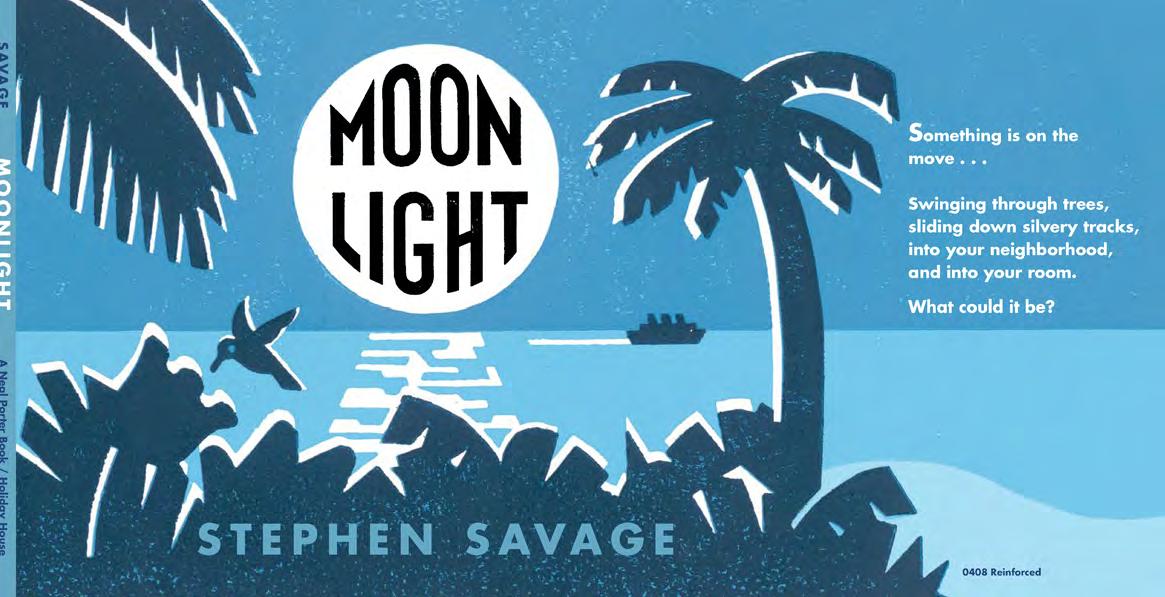

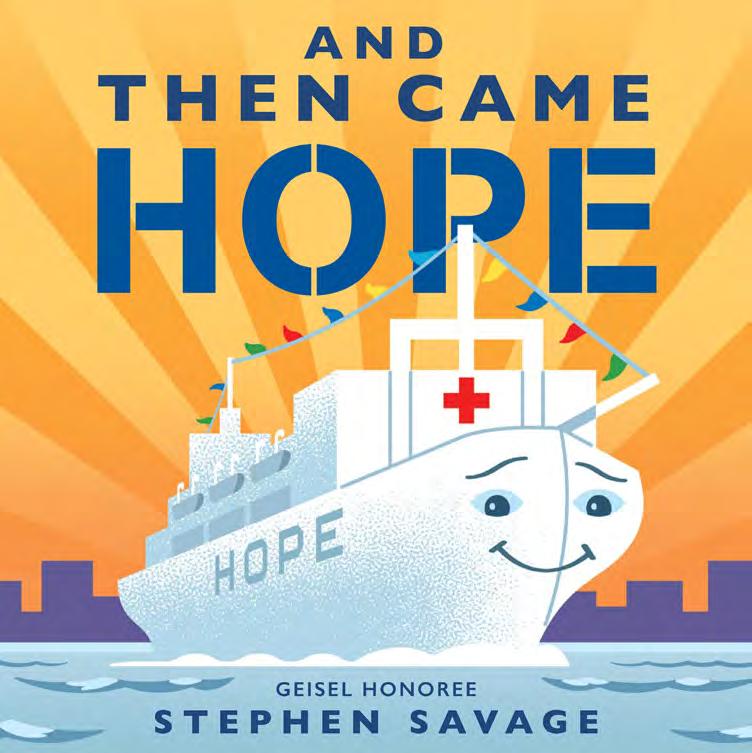

STEPHEN: It wasn’t until 10 years after graduation that I started doing kids’ books. I had some success with the editorial work, and I wanted to try something different. I had a friend who was starting to publish at Scholastic with David

Saylor, and I sent him a promotional postcard. It was a portrait of Cary Grant. If you sent a picture or a portrait of Cary Grant to someone in children’s books today, they’d think it should have gone to an editorial art director.

But [David Saylor] could see the essence of my style in that portrait and thought that it could work for a children’s book. So there was a lot of room for latitude in these decisions. There’s not as much these days; now you have to hit the ground running.

[David Sayor] knew that I had another career in illustration, that I wasn’t a beginner. I think there was a trend also at the time when editors were plucking illustrators from the pages of magazines and newspapers.

It’s interesting when I think back to those days because, as I said, I don’t think I was ready. I had these naive perceptions of what a children’s book writer is. For my first book, Polar Bear Night, I was able to learn on the job.

ARAM: If people are willing to learn and can work collaboratively, they always end up making great work.

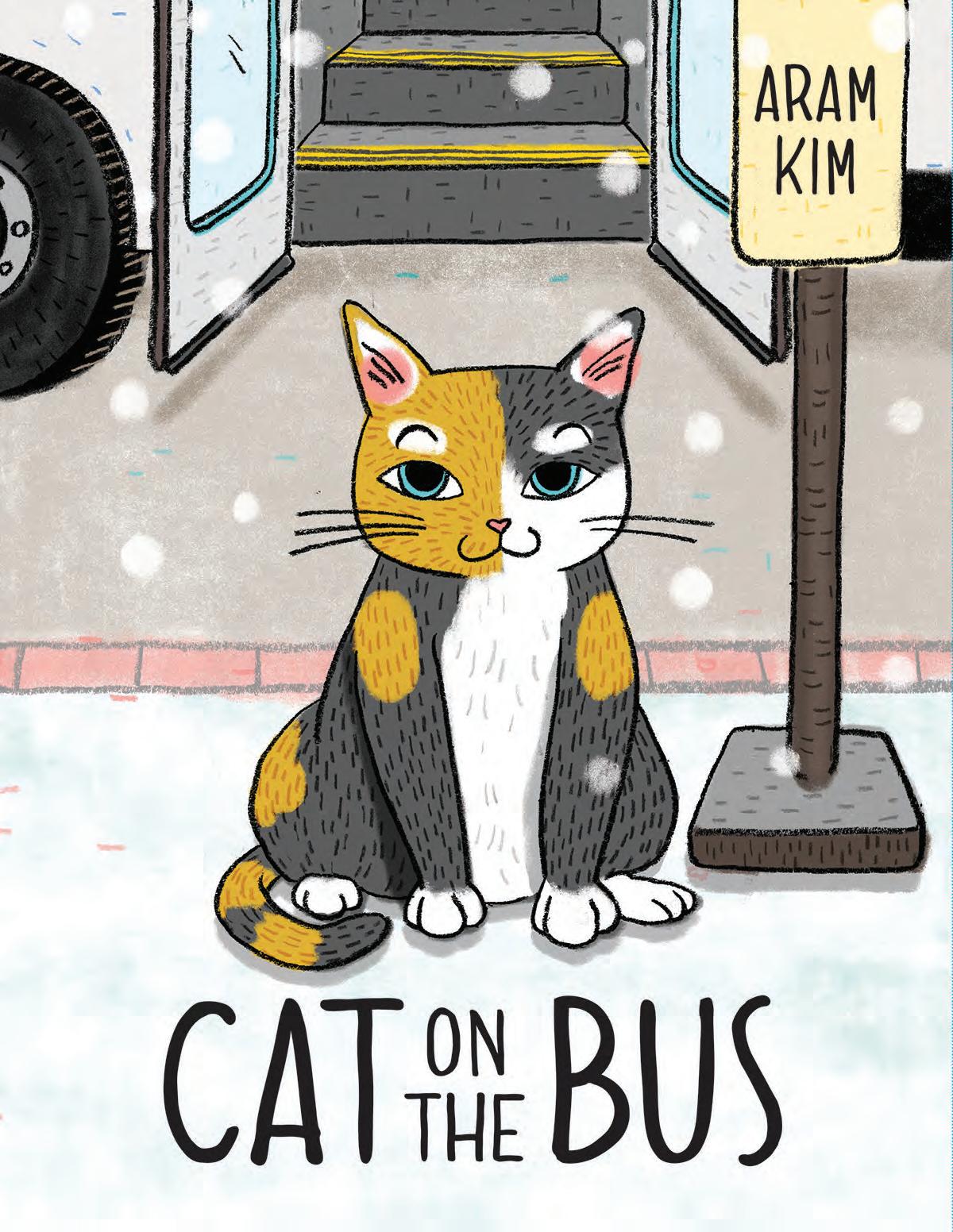

STEPHEN: Your thesis was a book that actually got published, Cat on the Bus. Did that book need a lot of help or were you able to take your thesis and just turn it over to the publisher? Did it need a lot of work, a lot of editing?

ARAM: A lot of editing was done during the program with the help of Pat Cummings, who was my advisor at the time. She was just an excellent mentor. Everything I’ve done in children’s books I owe to her. I learned so much over time. And I did three pieces at a time with her. That was her advice—doing multiple projects at the same time, and Cat on the Bus was one of them. After graduating, I really pushed that book to be submitted because it was the book that was getting the most reaction from people.

I’d go to a few publishers, and then

each time I got feedback, I would make edits, but the big arc in the story actually stayed pretty much intact. The biggest change they made during the submission process was adding text because it was originally a wordless book. Wordless books are amazing for creators who want to tell stories through pictures, but it’s very hard to sell on the market.

I got great feedback from an editor from FSG [Farrar, Straus and Giroux] to bring in some text, and then it actually got published by Holiday House.

STEPHEN: So [Pat Cummings] makes you work on a bunch of projects so that you don’t put all your eggs in one basket, that you’re trying different things.

ARAM: When you work on one project, especially as a student, you get so attached to it that you don’t let things go. It’s hard to get feedback, and then you’re stuck with one idea or story. And so I think it actually gives you room to have some distance from your personal project and be more objective.

STEPHEN: So you’re my art director right now, and we’re linked in all these different ways. Did you start art directing right away after graduation?

ARAM: It’s been only about three years since I started working as an art director. I started as an intern at Little Brown Books, but that happened the summer

after I graduated from the MFA program. It was an amazing experience. I got to see all the original art from Sophie Blackall and Jerry Pinkney, these great illustrators who were already working with Little Brown. It was a great experience to see how these things work, like what is done when illustrators submit, how they review work, how they have to talk to all these different departments in the publishing house, like the editorial department, design department, production department, copy editing department; it’s all such a collaborative process that I didn’t know about. I never would have thought that I was suited for a corporate environment, but I was really enjoying it, so I ended up staying as a freelancer. During that time, Cat on the Bus was published and the design team came to celebrate with me. By that time, I was working on my second book, so I thought I had learned all the secrets. I thought I should be ready to go off as a full time author and illustrator. So I left Little Brown to work on my book, and then worked continuously as a freelance book designer with different publishers. One year later, I started working as a full time designer again at MacMillan.

STEPHEN: When I found out that you were my art director, I already knew your books, and I saw that you art-directed We Are Water Protectors, which won a Caldecott in 2021. And there’s another, A Place Inside of Me? That also got a Caldecott honor—

ARAM: It was the same year, which was insane to me. You never know which book will win the Caldecott awards. I do the same work for every single title. When it comes to winning awards, for me, it’s luck. But for the illustrators, it’s pure work, right?

STEPHEN: I disagree. The art director’s vision of the book is key. Of course, the illustrator is making the images, but an illustrator relies on the art director to

provide a vision. The illustrators are in a state of chaos and flux and the art director is kind of like the adult in the room who tells them to wait, calm down, you’ll be fine. So without that kind of guidance, the book doesn’t get made. There has to be a captain of the ship, that’s what the art director is.

ARAM: I really love the process that we have working together. Another thing that I want creators to know is that there is a whole team working on your book. There’s a production manager, who chooses the paper; a special effects and production editor who’s working on the grammar and punctuations and spacing between the text; so many people rooting for your book.

STEPHEN: When doing both illustration and art direction, do they help each other? Most of the art directors that I work with are not artists. So when I have an art director like you, it feels different when you give me feedback because it’s coming from another illustrator. You can be really sensitive to my needs as an illustrator, whereas most of the time, an art director is a designer and doesn’t know that much about illustration. I’m not saying that’s bad, but they don’t know anything about the picture-making process and might not be able to help me solve a problem. But I’m curious, you work at Macmillan and then you come home to work on your own books. How do the two things feed each other?

ARAM: Normally I think they work well together, except for one thing, which is that I’m so tired! Aside from a time crunch, I think the synergy between getting to work with other illustrators as an art director is great because I get so much inspiration by seeing different illustrators’ work and processes. And because I work with so many different people, I see so many different ways of solving problems. Also, being on the side that reviews their art and gives feedback has given me the ability to look at my

own work objectively. I couldn’t do that before working as an art director—you get too attached. When I give feedback to myself, it’s as if I’m critiquing an illustrator that I’m working with.

STEPHEN: That’s amazing. That’s a skill that illustrators really need to develop.

ARAM: It’s hard!

STEPHEN: You need good illustrators who can be art directors for their own work— to know what needs to be better, what part isn’t working.

ARAM: Yeah, that’s such great practice for students. The illustrators I work with

give me a little more credit because I’m an illustrator, so it feels more collaborative. There is kind of a mutual respect. I am blown away when I get artwork from illustrators, and that feeling never goes away.

STEPHEN: I just got my corrections yesterday for Rescue Cat from Astor, a designer who works for you. The email was several pages long! It’s funny because during the initial read of all the notes, all I could think was I can’t do that! I can’t change that! But then I realized these are all things that are going to make the book better. You know a children’s book takes a long time, so it’s a long slog. I’ve been working on that artwork for six months,

and now I have all these things to do, all these changes to make. You’re running a marathon and someone pushes back the finish line.

It’s so amazing to have people that are looking at the work and are invested in the book. There was a lot of thoughtfulness that went into those notes that you guys sent over.

ARAM: Art directors really do care. And we love Rescue Cat! Emily, the editor, is so in love with the book.

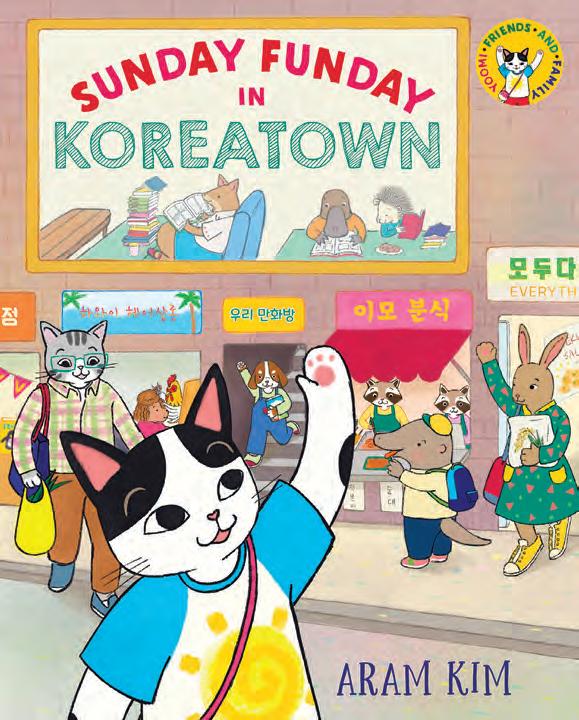

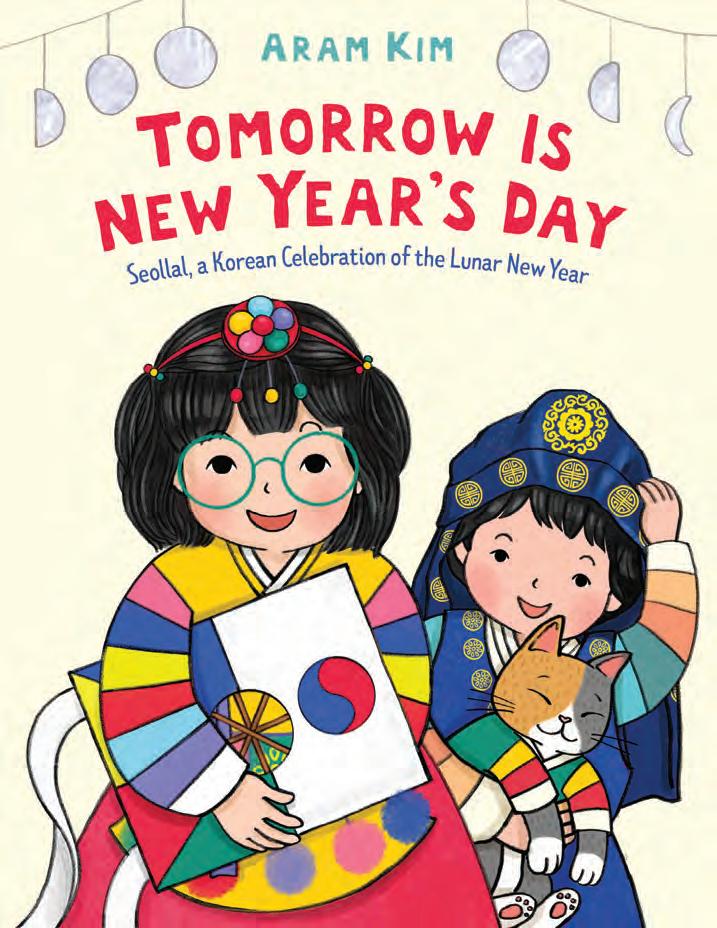

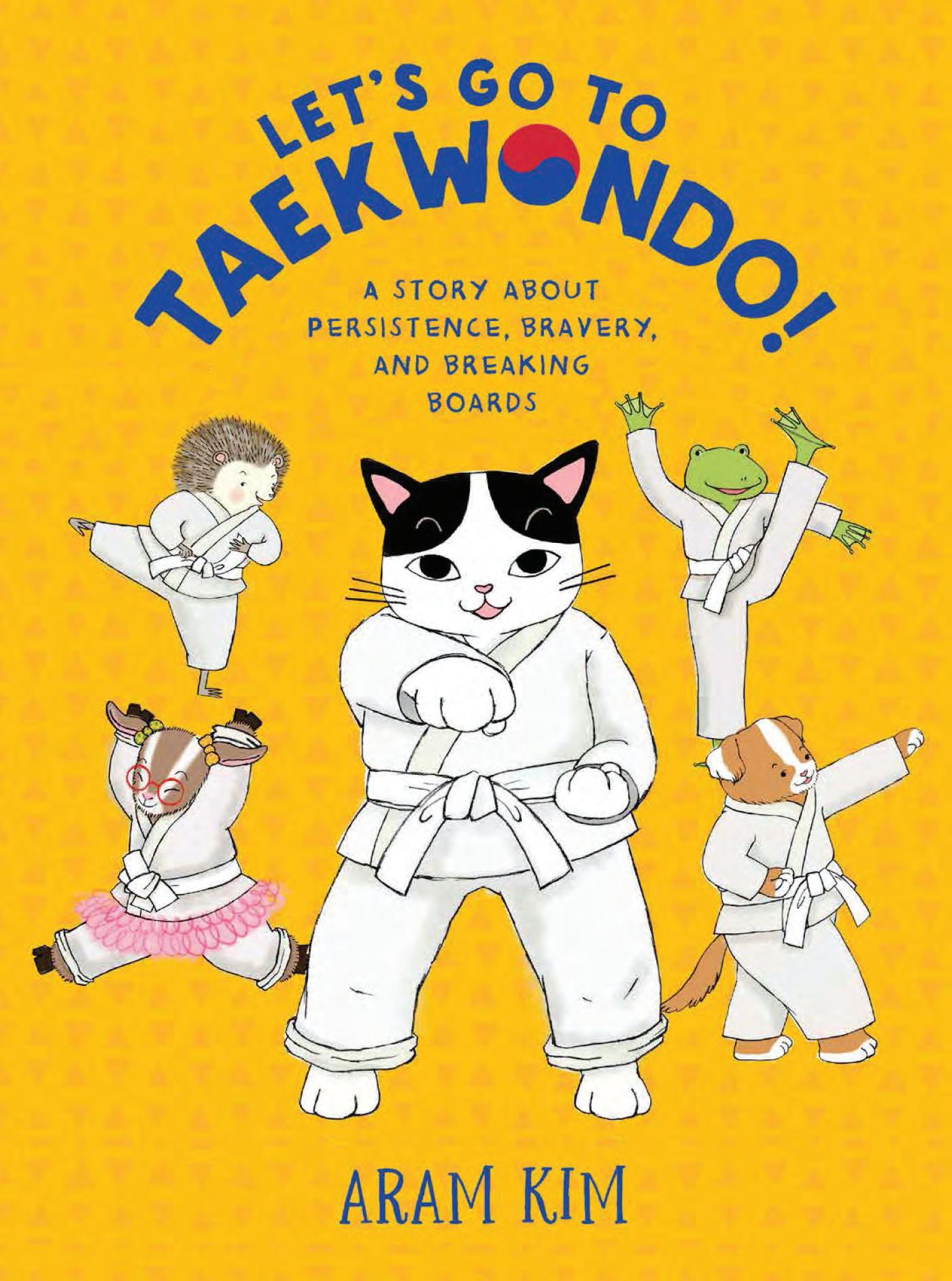

STEPHEN: I’m so excited to hear that there’s that much love for the book. I also think it’s hysterical that four of your five books have had cats in them, and now I’m doing a cat book.

ARAM: Draw what you like and draw what you know, right?

STEPHEN: It takes a lot of courage when you’re young to say, “Oh, draw what you like” and “Well, I don’t know what I like!” I started thinking about becoming an illustrator in 2006—that’s 15 years ago. But you’ve been on this journey for a long time to try to answer those two very simple questions. You showcase your Korean heritage so beautifully in your books. How long did it take for you to figure out that that’s what you wanted to do?

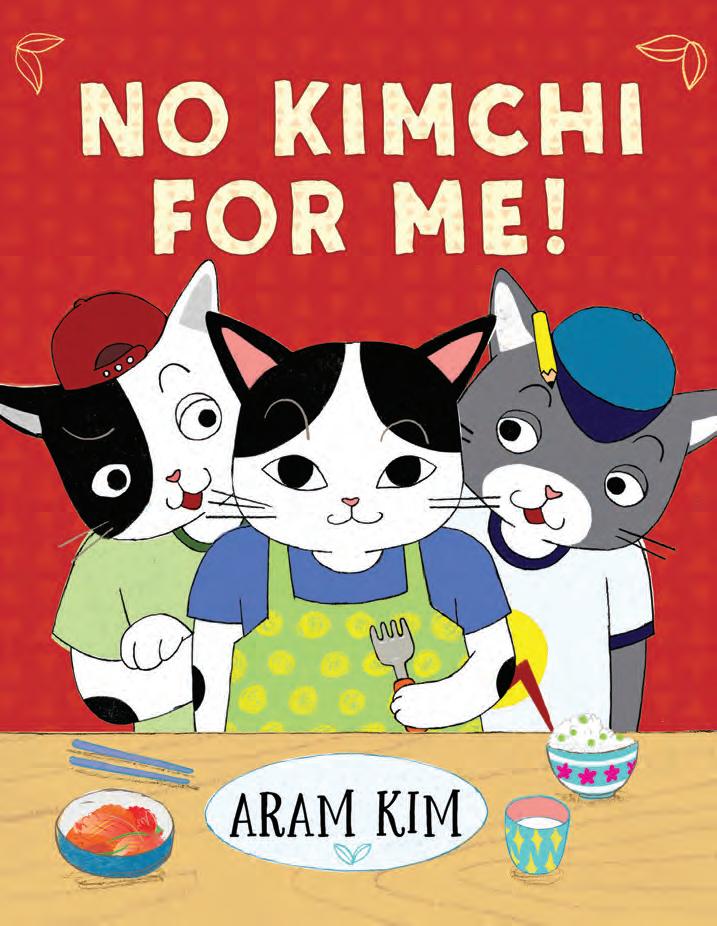

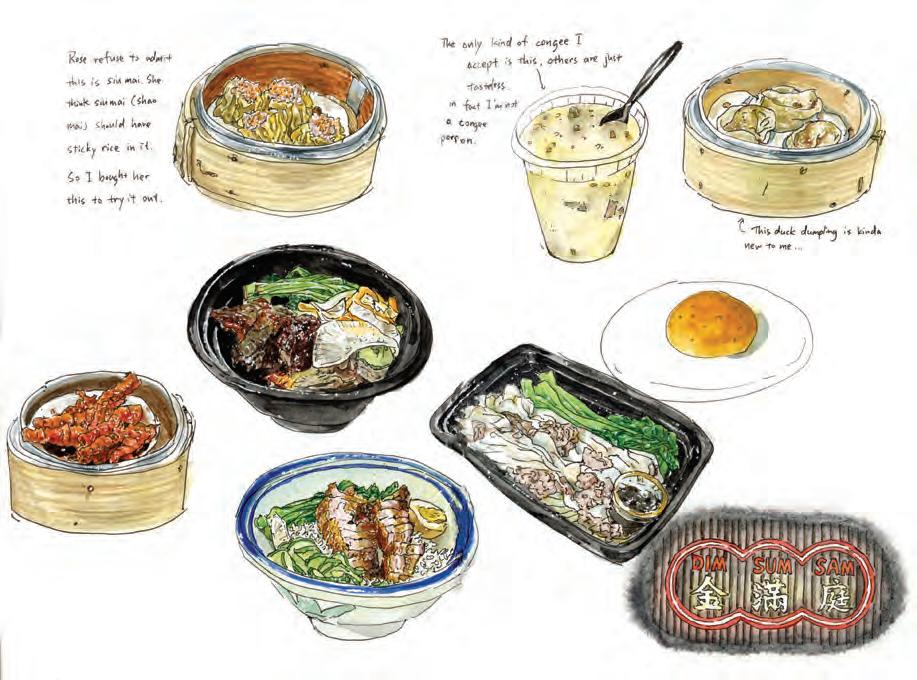

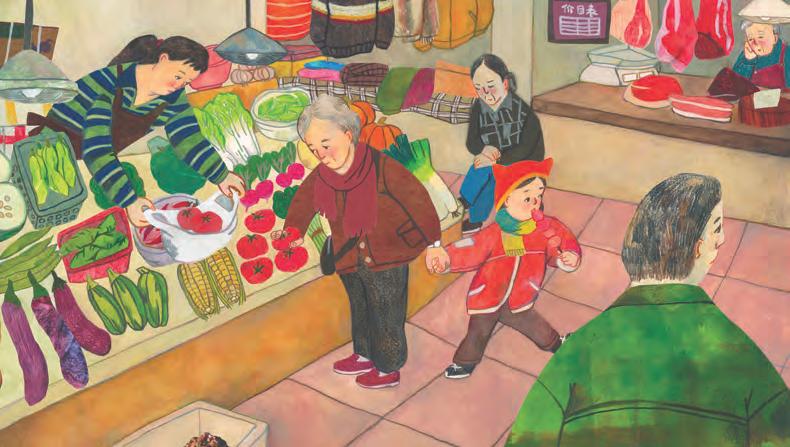

ARAM: When I was in the MFA program, Marshall Arisman said, “Draw what you like, draw what you know.” I remember writing this down in my sketchbook thinking, Oh my gosh, I don’t know anything But I wrote down three things: cats, Korea and food. But what am I going to do with this? And then I end up making a book about Korean heritage. The first book I did about Korean culture is No Kimchi for Me, which was my second book.

STEPHEN: Marshall was so good at meeting people on their level, and you start with those two phrases: Draw what you know,

draw what you love, and don’t worry about it. Start with what’s in your heart and what’s in your mind.

ARAM: It’s so deceptively simple.

STEPHEN: You knew what your goal was, but you had to figure out how you were going to get there.

Nobody can tell you how to do that. It’s a lot of trial and error that gets you to that goal.

ARAM: With that book especially, there was a lot of trial and error, and I owe that to my editor in Holiday House, Grace Maccarone. I learned so much about storytelling from her.

Working with Grace, I learned how to boil down the essence of the story, which took me a long time. There is so much that you want to tell, but then there’s only 32 pages.

You really need to have focus, and you really need to have a single strong storyline that kids can follow through.

STEPHEN: It was Neal Porter who would tell me I’ve got to get to the idea of the book quicker on page three. Otherwise the reader is so lost.

ARAM: That’s very good advice for children’s book storytelling in general. There’s no long introduction. Everything has to happen fast and you need to get to the problem, you need to serve it, and you need to have a satisfying ending.

STEPHEN: They say an editor is not really your boss but your first reader. They’re going to put themselves in the role of some seven-year-old, six-year-old kid in a library opening your book. If they’re a good editor, they should be able to channel that six-year-old reader. I want to ask you for some practical advice, and maybe, gosh, this will even help me! But it’ll help anybody who wants to get into children’s books. What should they have in their children’s book

portfolio? Many people don’t know what to include. They don’t even put kids in it! Does it always have to have kids? What should those kids be doing?

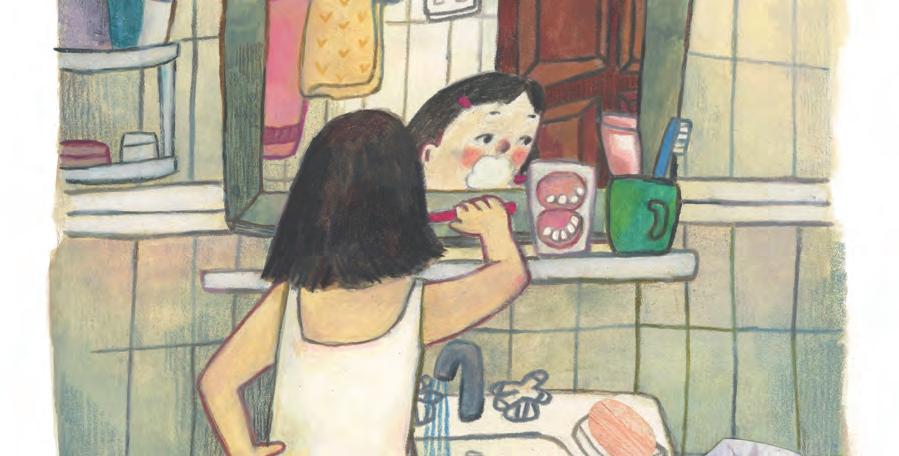

ARAM: I would be super practical. You don’t have to follow this to the letter, but this will make it easier to get into the industry. When pitching, there are a lot of opinions coming from sales and marketing, too, because the book is a product that we need to sell. It’s always much easier if you have a portfolio curated for a children’s book field to be hired as a children’s book illustrator. So yes, kids—because children’s picture books. You need to have an illustration of your target audience—not a portrait but them in action; set them in relation to someone else. If you look at any children’s book, we are not going to see a kid sitting around doing nothing. We need to see them in an environment. I often get portfolios with only character studies, which doesn’t give me confidence that this person can do a full spread of say, a school setting.

If it’s bedtime for the kids, don’t just have a kid in bed. Maybe the kid is having a storytime with one of the caretakers. Ask yourself: What is their body language? What are their expressions? We say the most important thing in a children’s book is emotion. If I look at a piece and don’t know what this kid is feeling right now, then it’s not a successful piece.

STEPHEN: It’s also interesting that in my notes that you gave back to me about Rescue Cat—and, of course, you need to always go back to our conversation about art directing yourself—you asked, “What are my characters thinking and feeling and how do you want the reader to respond to that?”

ARAM: But, Steve, what about you? What kind of advice do you give to your students who might want to do children’s books? What would you say?

STEPHEN: I think the biggest piece of advice is that you can’t do it without knowing what children’s books are. You need to sit down and research these children’s books and get to know them as pieces of literature and approach it as literature.

So many of my students have so many amazing skills, but they’ve got to be telling a story and all these images have to link up. You have to make a 32-page dummy, basically a rough draft of the entire book to see if you can take some loose sketches and create a story that has a beginning, middle and end.

If you’re thinking about going into children’s books, there’s all of this preliminary work that you have to do before you even get to the final art. It’s going to occupy you for probably several years to get right. Your audience should feel like they want to read the book again, a story they’re going to read over and over.

ARAM: Having loose sketches to really tell

a complete story from beginning to end—that is the best practice you can do.

STEPHEN: It’s hard to sit down now and create a dummy that’s 32 pages. It’s excruciating. The blank page is staring you in the face. I don’t know if I’ll ever feel like the sketch process is easy; it’s always the hardest.

Do you get pitched a lot of ideas?

ARAM: I used to get a lot, but not so much anymore because I’ve been making it clear that I don’t accept dummy books. I accept art samples from anyone because we’re always looking for artists but that’s my boundary. I also don’t acquire books, editors acquire books. So when a pitch comes to me, I feel like it’s a waste of time for both parties because, even if I think it’s a great idea, I’m not going to the acquisition meeting.

STEPHEN: Giving someone a really good

critique on a book means that you’re allowed to read the book and you have to think about it.

Just like all the corrections I have to do this weekend on my next book that came from Aram! But honestly, I can’t wait. I’m excited for a long weekend to work on it. Thank you, Aram. It’s always great to talk to you.

ARAM: Us working together has been great! I’m also so excited about Rescue Cat.

The Art of Illustration

BY CHARLES

There’s Art, and then there’s Illustration. We are all born artists—many of us were drawing before we said our first words. But only a few of us continue down the artistic path. Making marks as a child seemed natural, drawing pictures—we drew what we saw. In my own experience, the marks I made were merely scrawls on the pages of one of my favorite children’s books, The Little Engine That Could. I was fascinated by the story of the little engine and motivated by the full-color illustrations, which, at the time, were just art to me. In trying to capture the drawings, I saw I made circular ink marks on each page, to the consternation of my mother. It is the only book I remember my mother reading to me, and I can still hear her say, “Don’t you want me to read you another book?” “I think I can, I think I can” was the mantra of the little engine, which has had a profound influence on my journey as an artist, illustrator, designer and art director.

I was never the best artist in grammar school. If the best artist, Harry Miller, was busy doing one poster for class, I got to do the other. He was a big influence; I actually collected his work after projects were finished. I’m certain that, today, Harry is either an accountant, lawyer or a stock trader, as the art he created didn’t mean anything to him—he gave it away freely.

As artists, we love exploring the world around us, observing and recording as best we can. In grammar school, there weren’t art classes, there were no instructors, no critiques—everyone was free to draw whatever they pleased. Yes, there were class projects for Thanksgiving cards or to create Christmas gifts using popsicle sticks but these were just projects; no one was judging whether the outcome was good or bad. Afterall, art is subjective.

As young drawers—the description “artist” seems a bit premature—we drew for pleasure. We copied comics found in the Sunday funnies, or drew airplanes, battleships, princesses, or whatever we fancied. We did it on lined notebook paper, cardboard, even envelopes that were lying around. The materials didn’t matter, Crayolas, ballpoint pens or pencils were always at hand. I loved Crayolas, the smell especially, and insisted my parents buy me a new box every year—mostly because I had used up the black crayon—but also because there was something special about getting brand new “tools.”

Moving onto college, the challenges increased; to be an artist wasn’t easy. Drawing turned from a pleasure into a task that needed to be completed in a much more professional way. There were live models, still lifes, plaster casts—all meant to give us a definitive subject to try and capture on our pad. There were a great many avenues to explore and a world of tools at our disposal. Going to class was a joy; there was always something new to learn or to be exposed to. There were artist visits. I remember one in particular when the artist Lee Krasner came to our class. What I started to notice was that the really good artists didn’t look like the stereotypical artists—scruffy, unkept

posers—instead, they looked pretty conservative. It’s something that I also observe today when meeting illustrators.

Not everyone is cut out to make art as their living, whether it’s fine art or illustration, but everyone who has laid their path as an artist will always be an artist. Creativity is the backbone of all art; making things that matter either individually or professionally can only be accomplished by the creative mind. What makes the difference between fine and applied art is the purpose. The artist’s goal is self-expression. The illustrator’s main purpose is communicating a message, imparting information in an interesting way.

While illustration is an art, not all art is illustration. Artists can create whatever they like, whenever they like. Illustrators are given assignments, briefs and deadlines. Other creative fields offer some respite, i.e., if an art director didn’t come up with any new ideas today, they won’t be fired. Illustrators are put under pressure, especially in the editorial realm, with three- or four-days max to come up with the idea and execute it. And if the idea fails, the artist fails. As opposed to being a fine artist where failures go unmarked.

The typical picture of the artist is alone in the studio making art. And while many may start out that way, soon there will be assistants to help with creating the final work. Not so with illustrators. Illustrators live a solitary existence, many have started out working on the kitchen table, or a corner of the living room or bedroom. No studio. No studio mates. No assistants.

During our monthly portfolio reviews at 3x3 magazine, I get to meet artists at all levels. Our 30-minute sessions allow us to explore why they want to be illustrators and what they contribute that no one else can. Illustration is like fashion, there are always trends, trends I’ve experienced since founding 3x3 in 2003. And like fashion, trends go in and out of style. What was prevalent in 2003 is not in 2023. Illustrators are hired based on their personal voice, also known as style. In the United States, and in most of the world, it’s a singular style that identifies how the individual sees the world and how the world sees them. Gaining a distinctive style is no easy task. It helps being open to personal experiences, to your cultural background, to literature and music—all can help define you as an illustrator. Having broad experiences—either naturally, through classes or through books—better enables an illustrator to solve visual problems; it’s the chief criteria for a successful career.

Being successful in any career is not easy, but it is especially hard for illustrators. Let’s define success: it’s the ability to make a living as an illustrator. But beware: illustration assignments do not come with any regularity. Many talented illustrators have second or third jobs to make ends meet. So how do you succeed? Part of it is luck—let’s be honest—and part of it is talent, part of it is self-promotion, and a big part of it is having a champion, some art director or editor or publisher who fancies your work.

Illustration is a highly competitive field. I’ve found every graduate wants to be either an editorial or children’s book illustrator or sometimes both. It’s important to seek out other opportunities to use your illustration skills beyond what you may think you know. No matter which area of illustration you choose, it is an art practice where quality is crucial—quality of approach, quality of drawing, quality of concept or storytelling. You can be a good illustrator with quality alone. But to be a great one, you need both quality and significance—your work must stand head and shoulders above what’s already out there. It’s not an easy task to be an illustrator, but be an artist first, then decide which is the best fit for you.

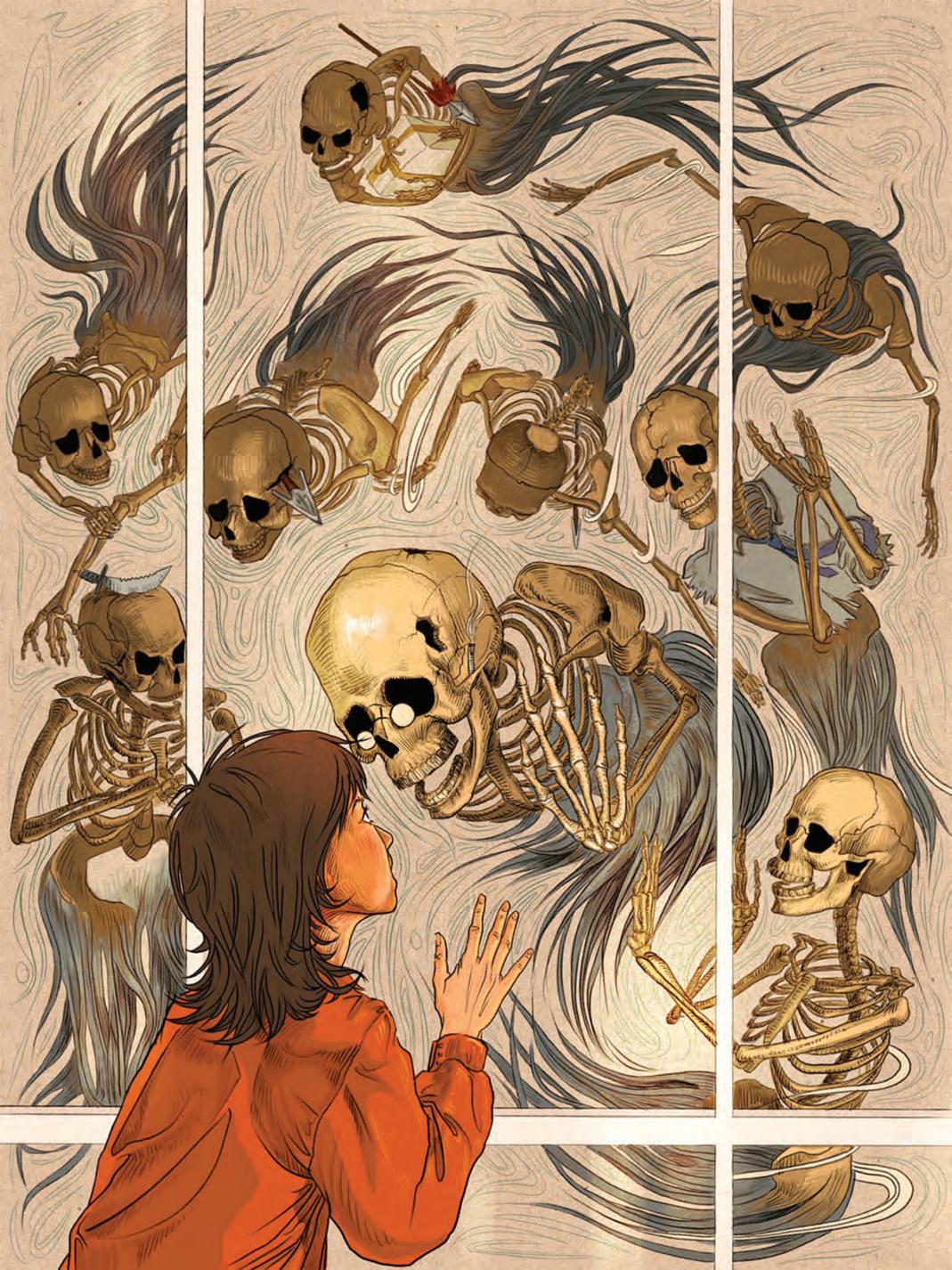

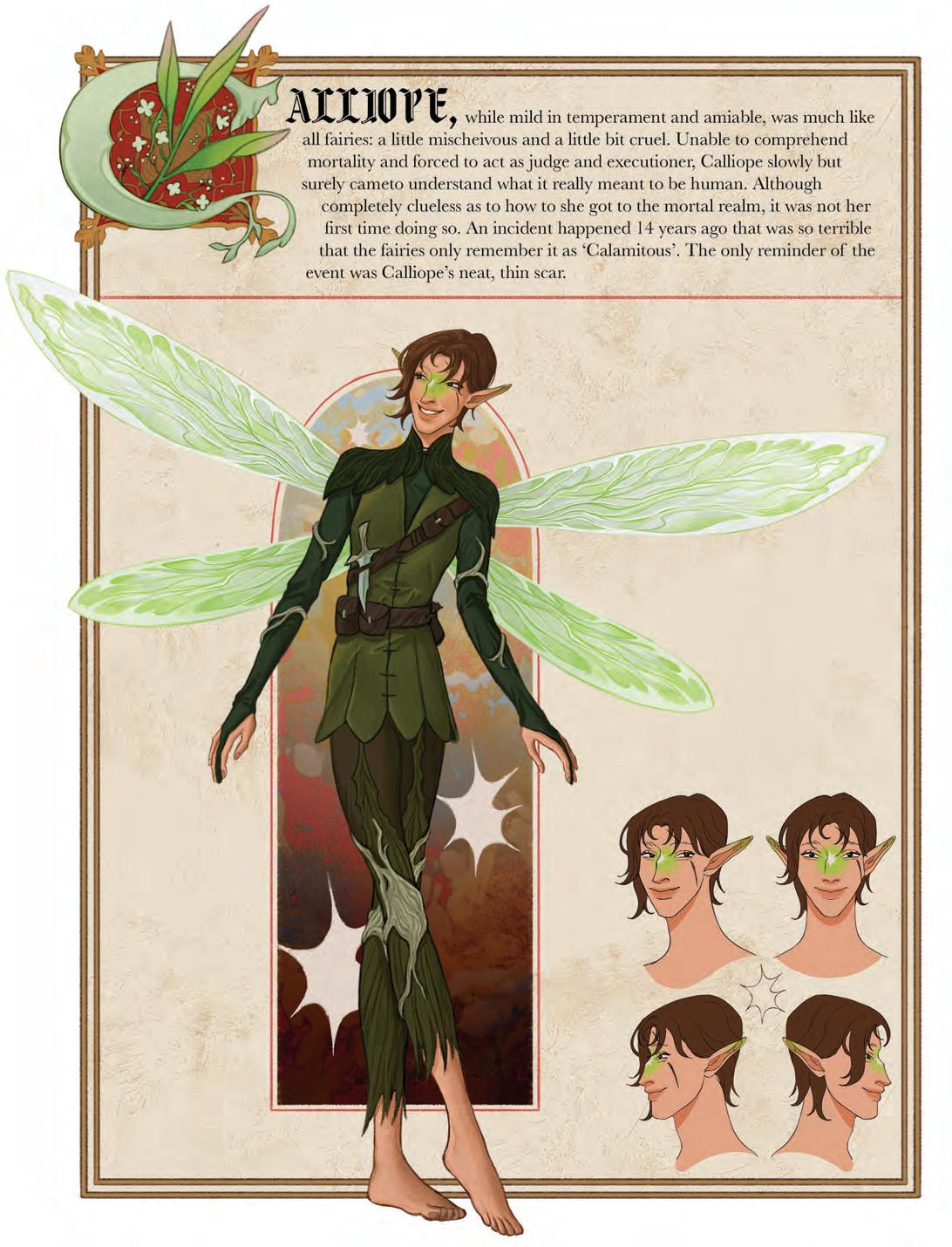

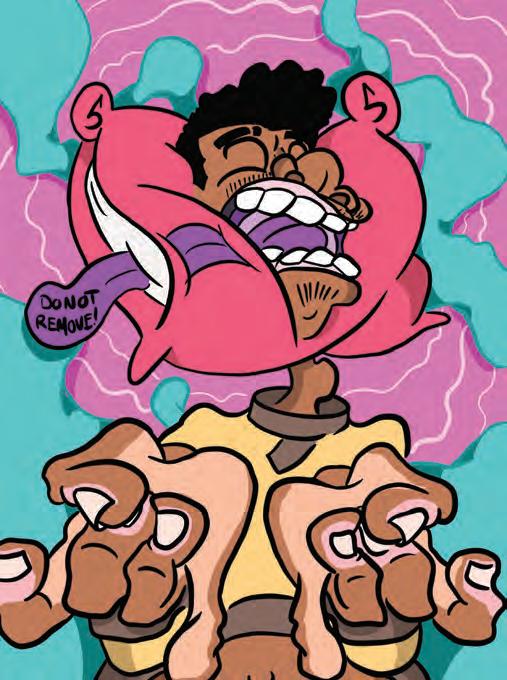

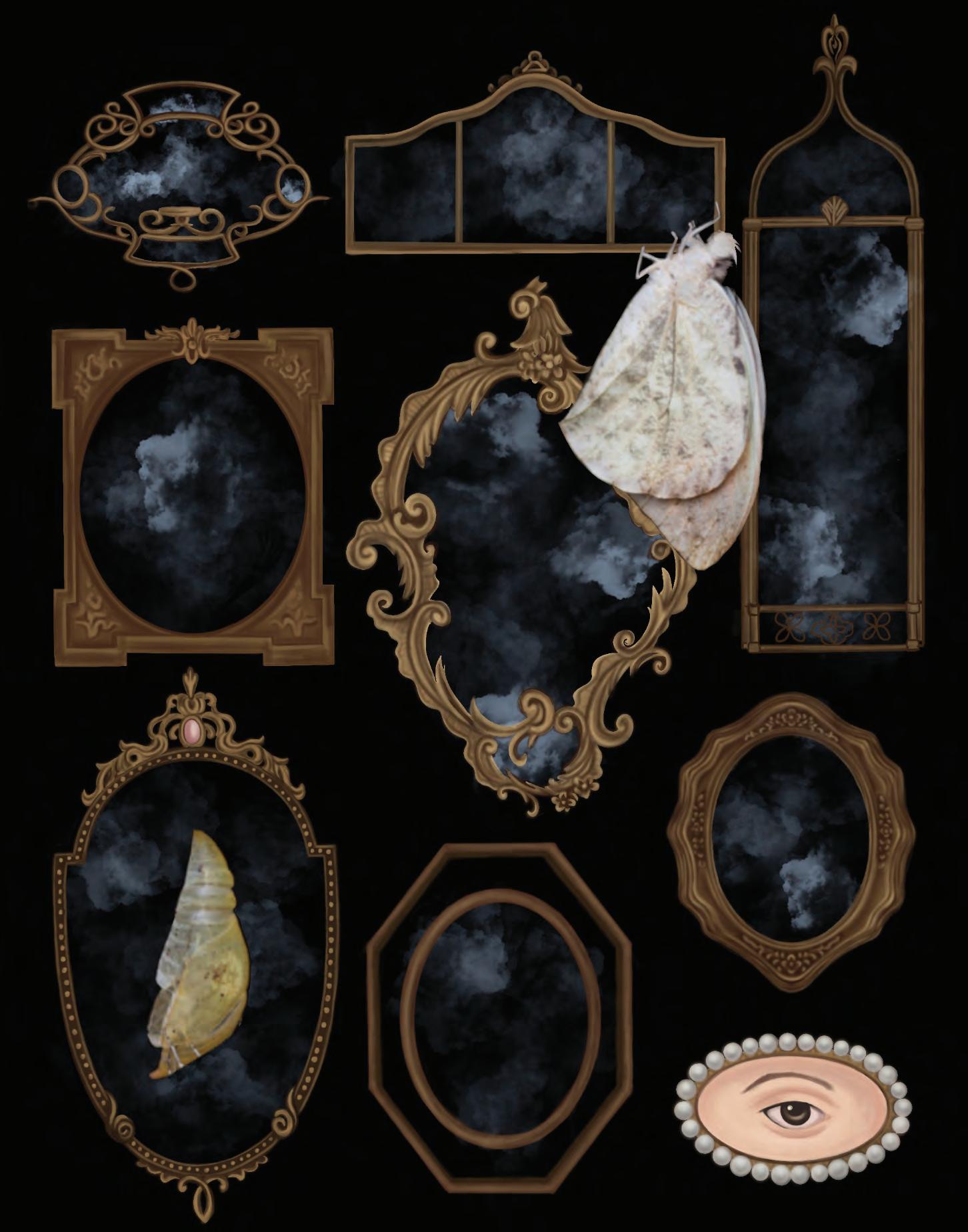

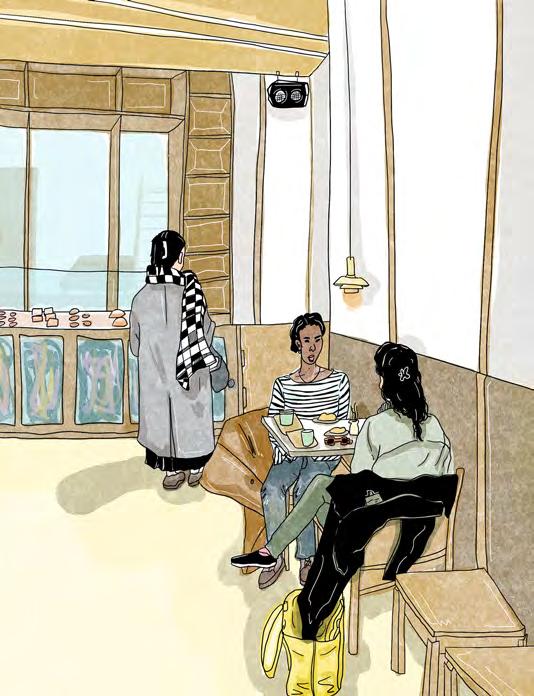

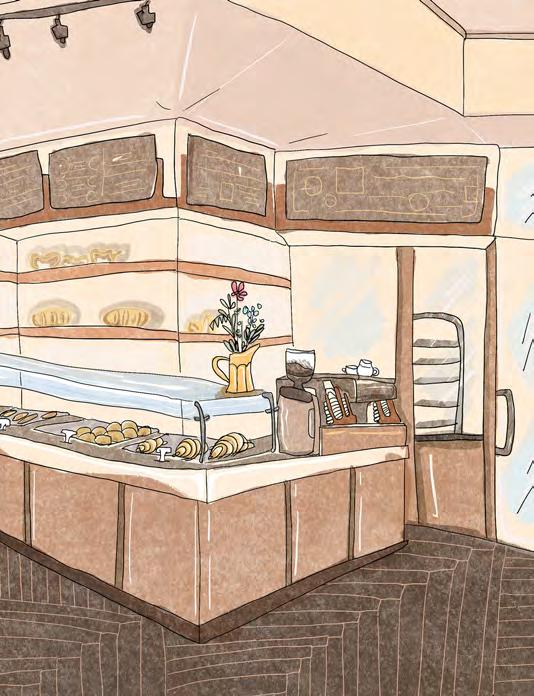

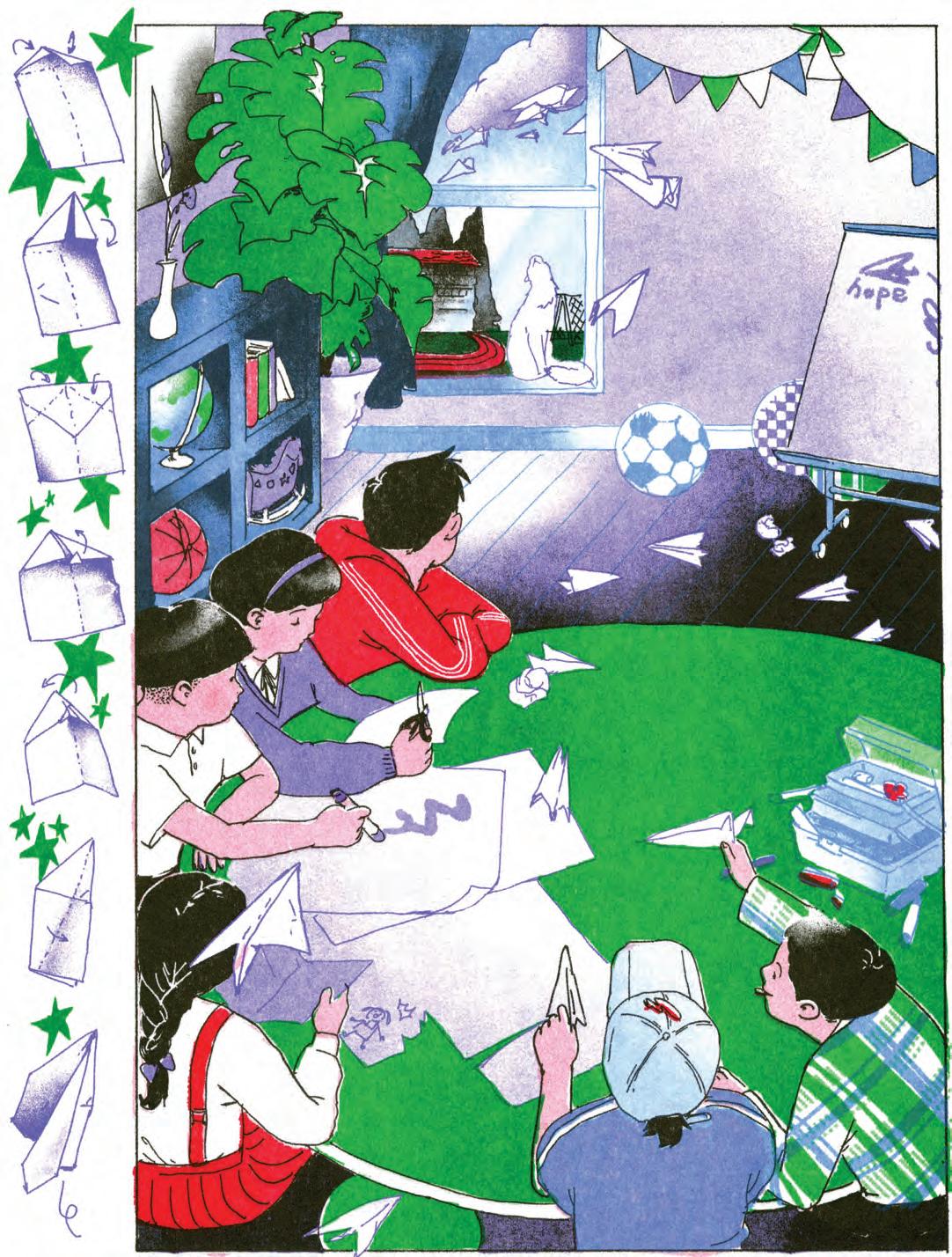

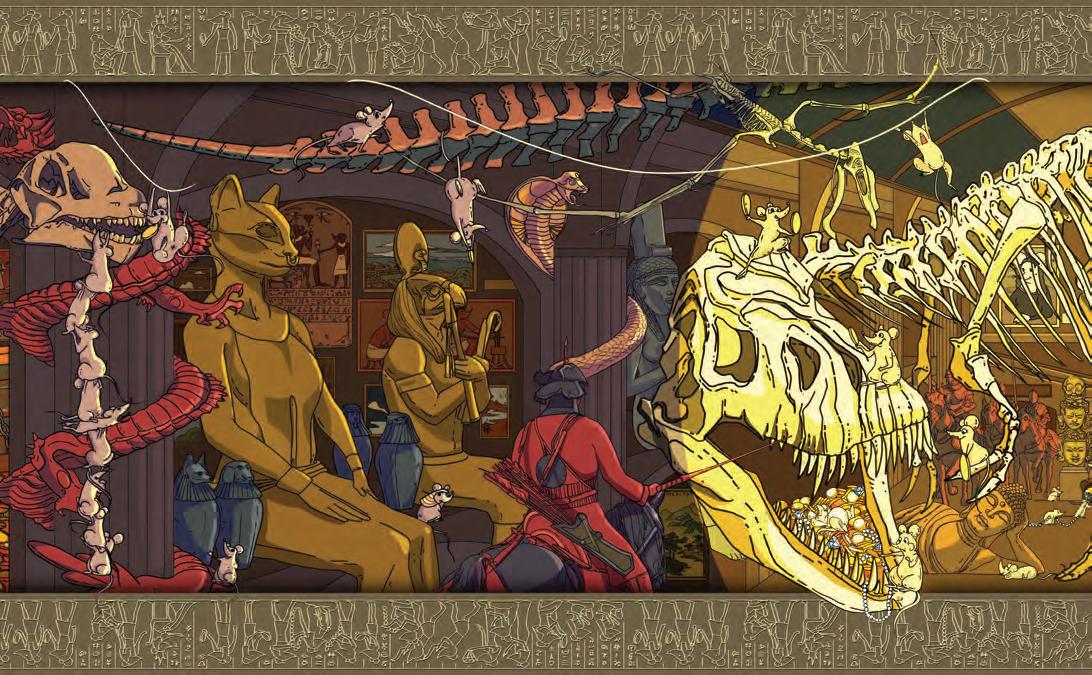

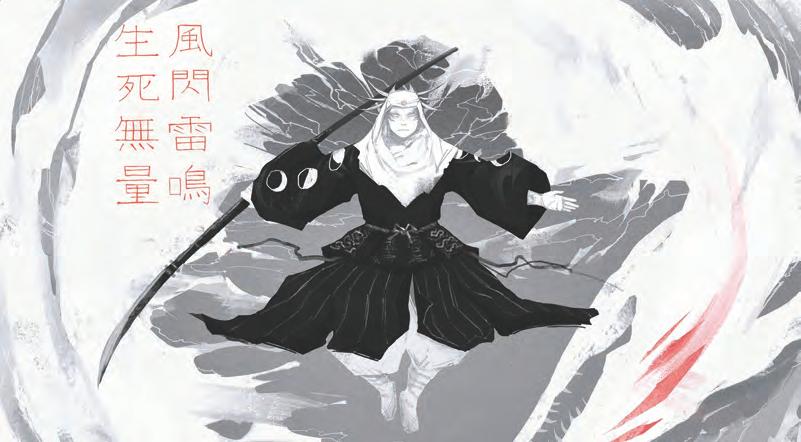

[1] Katherine Lam

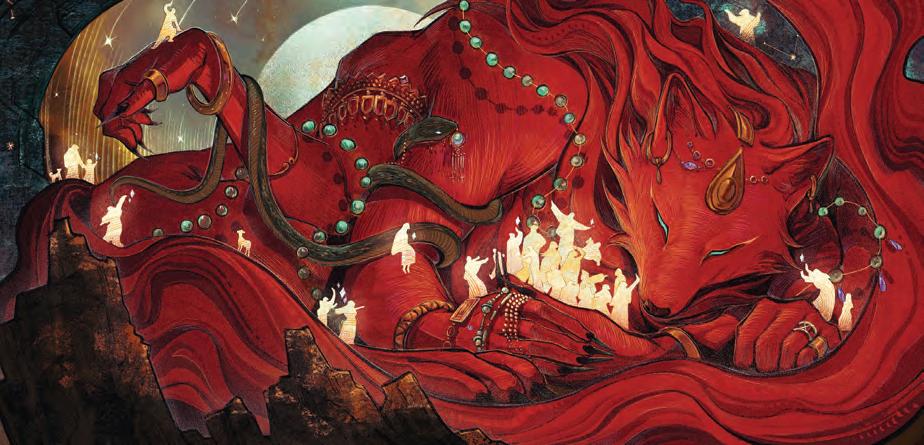

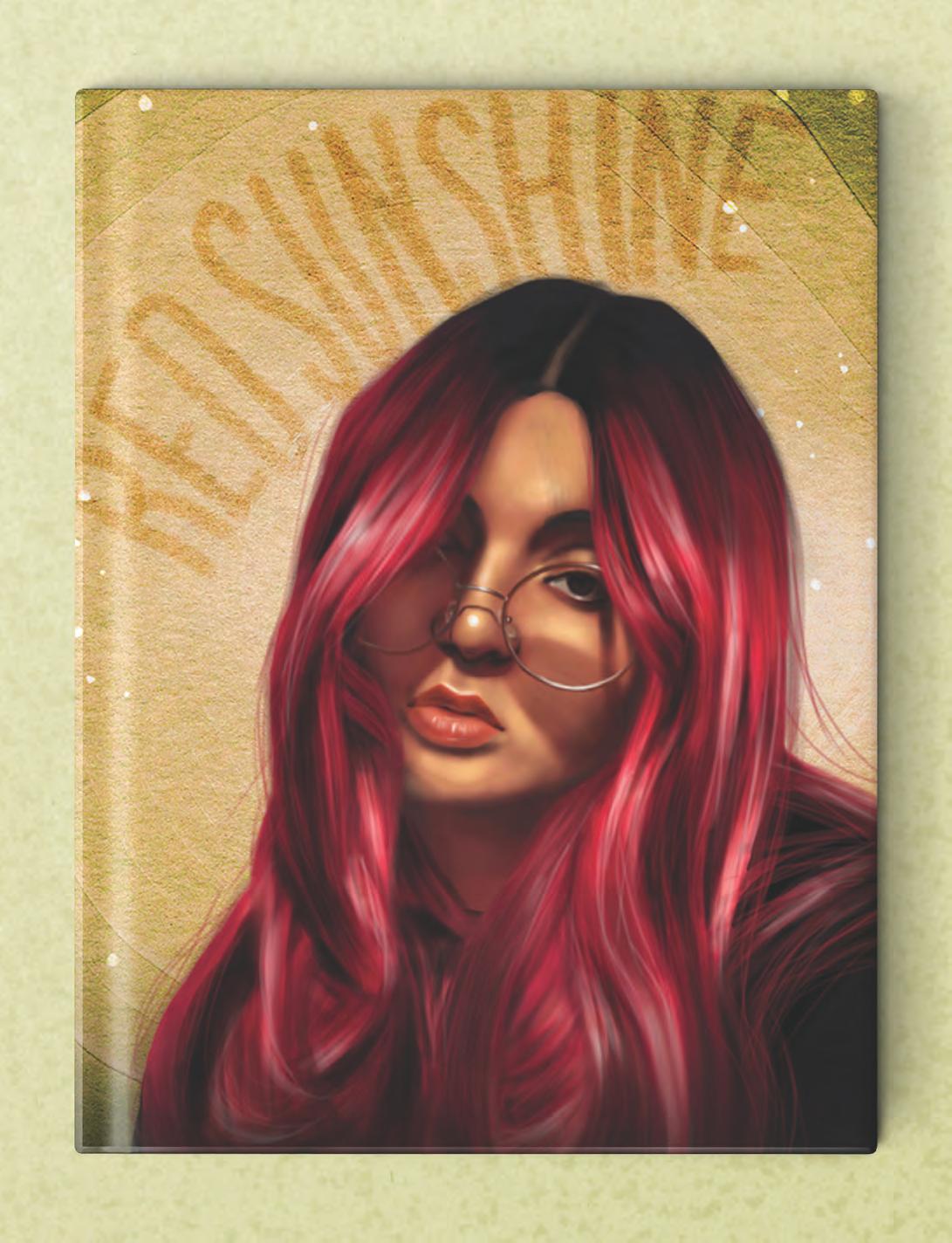

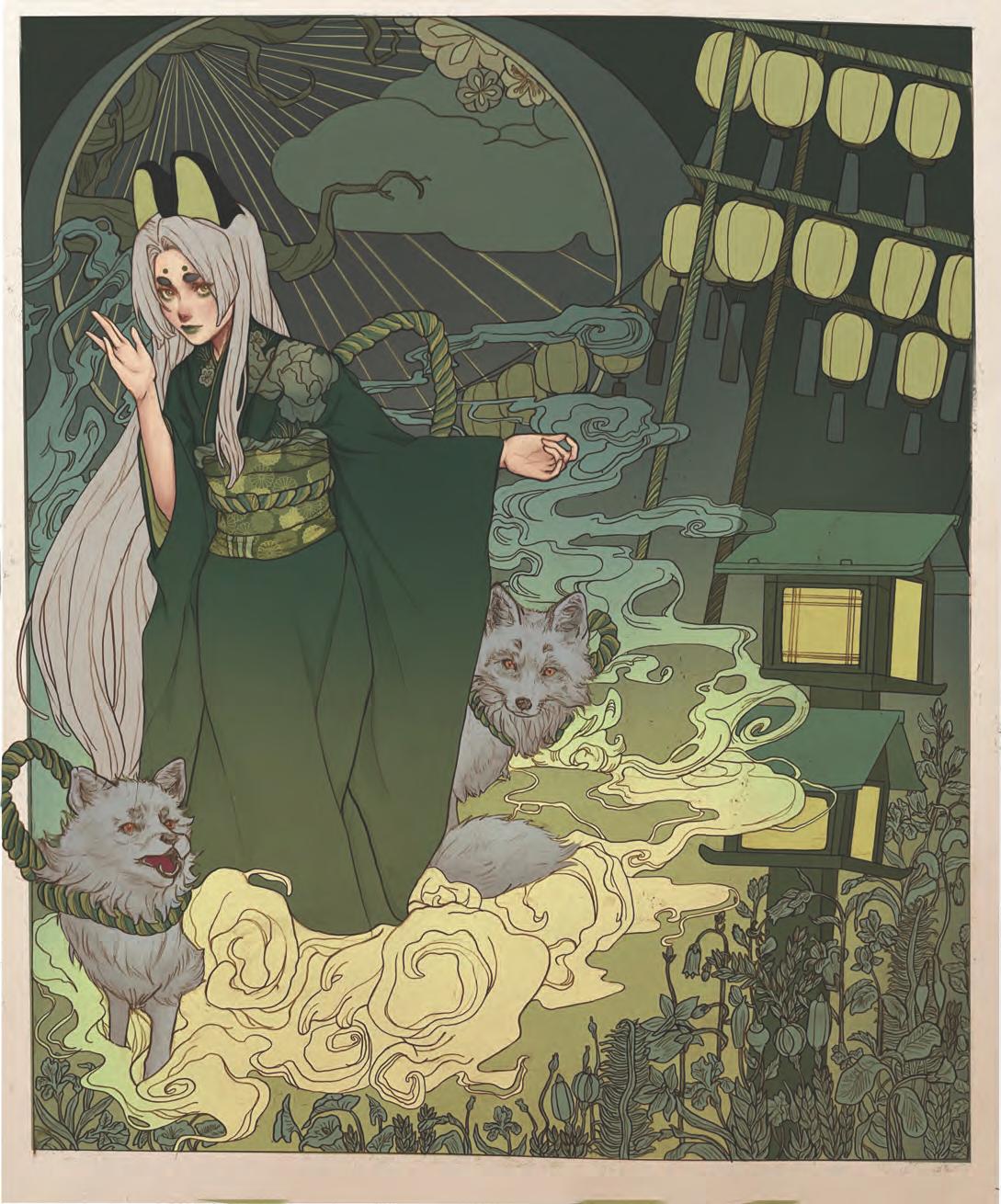

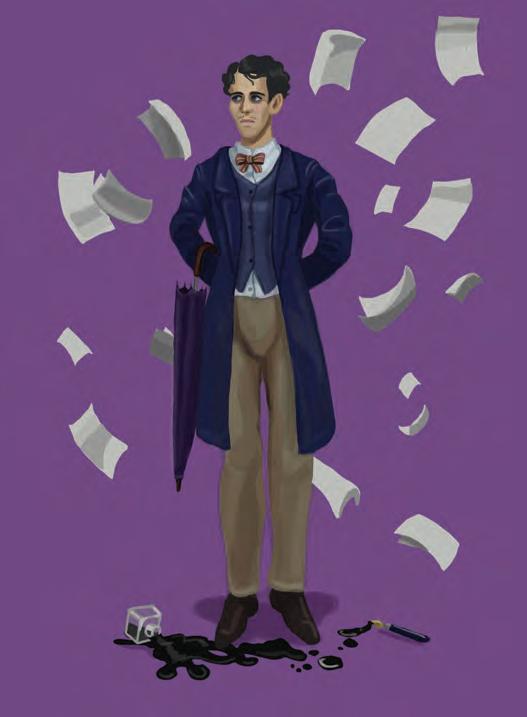

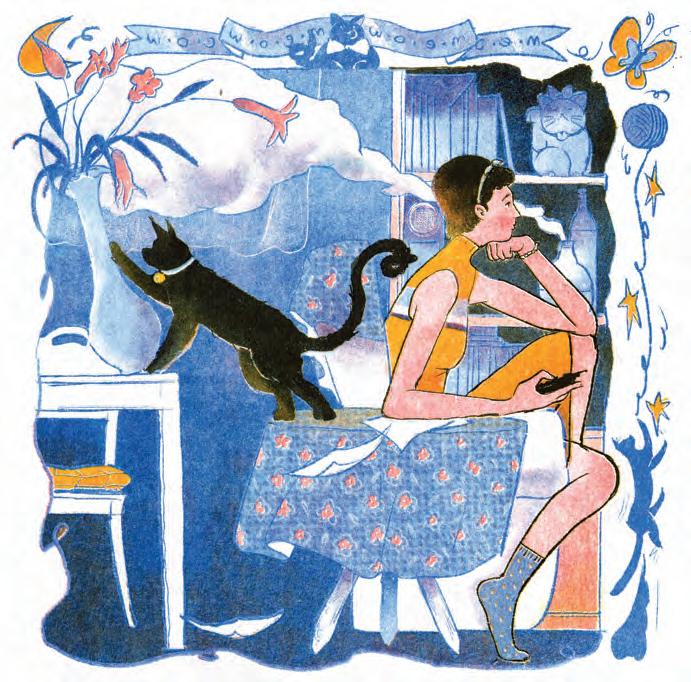

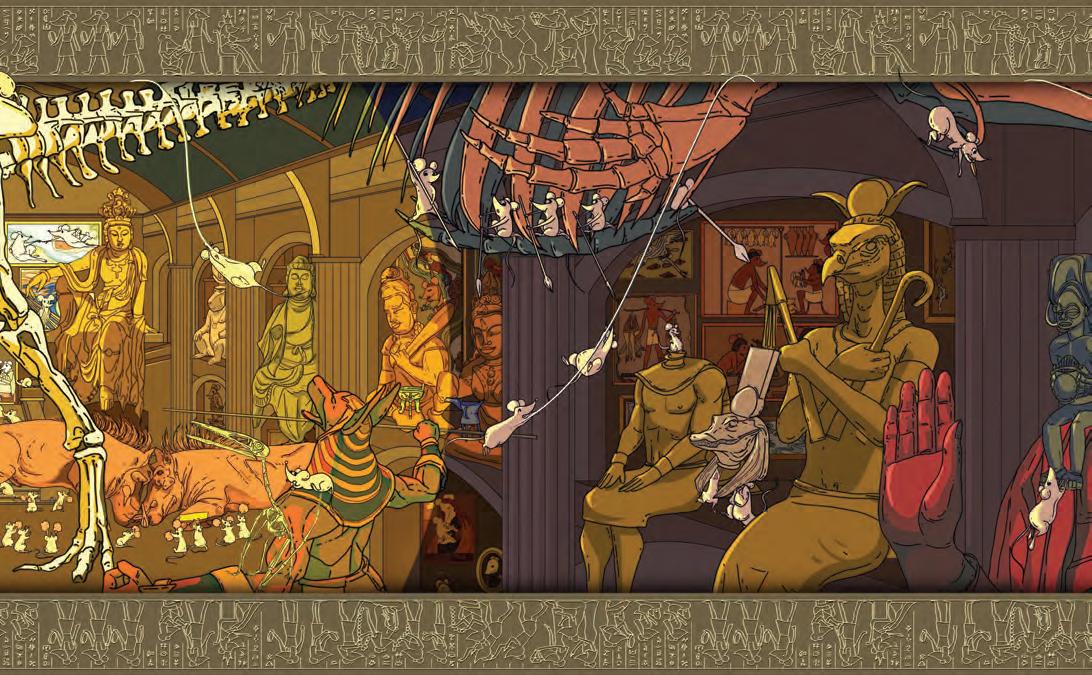

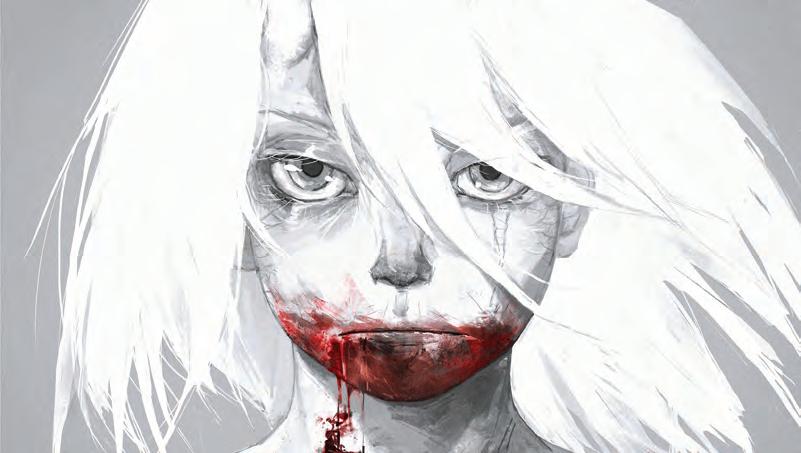

[2] Feifei Ruan

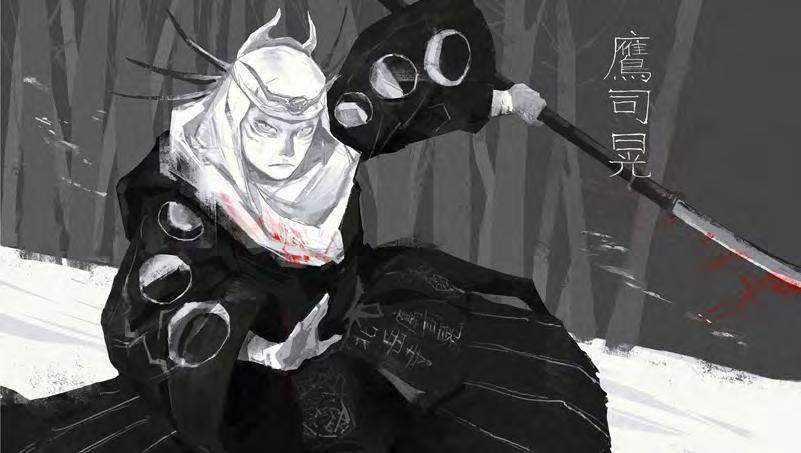

[3] Katherine Lam

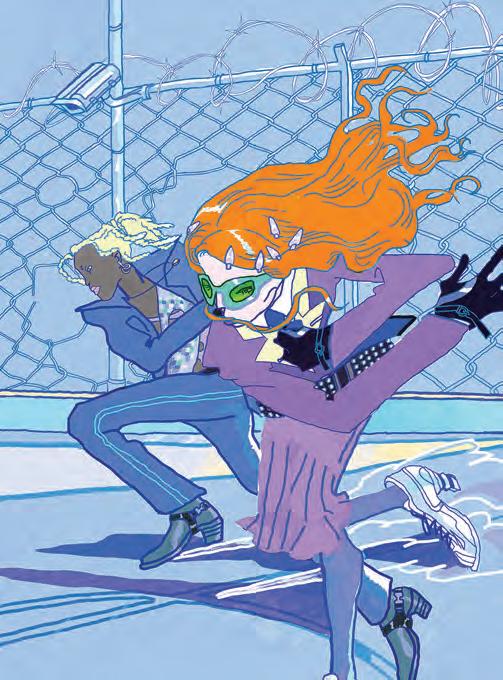

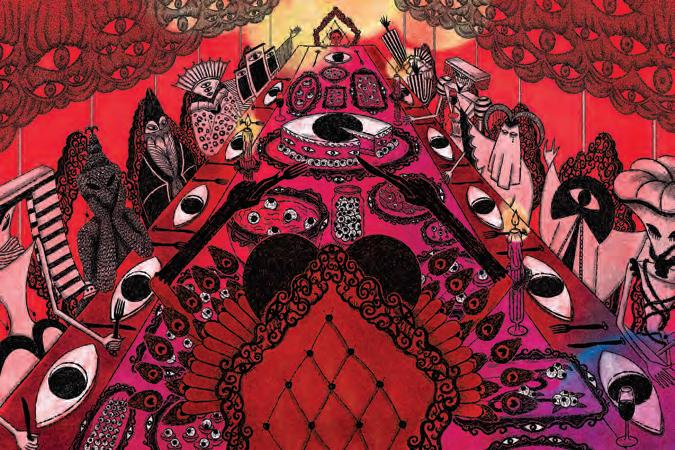

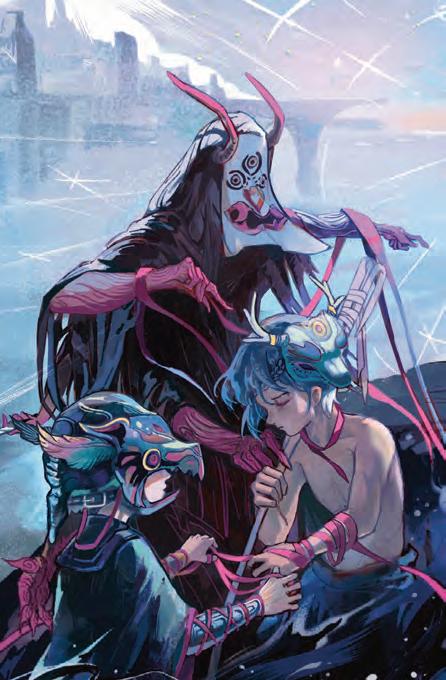

[4] Keith Negley

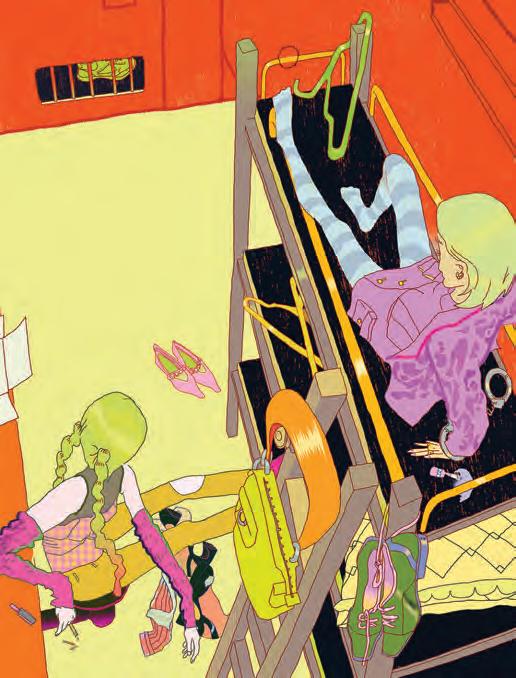

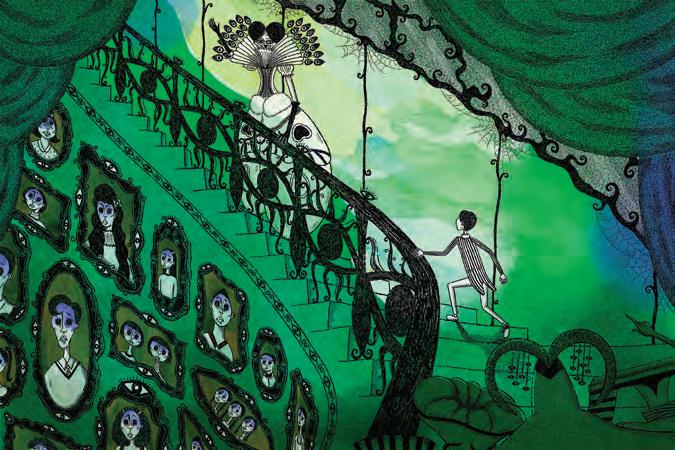

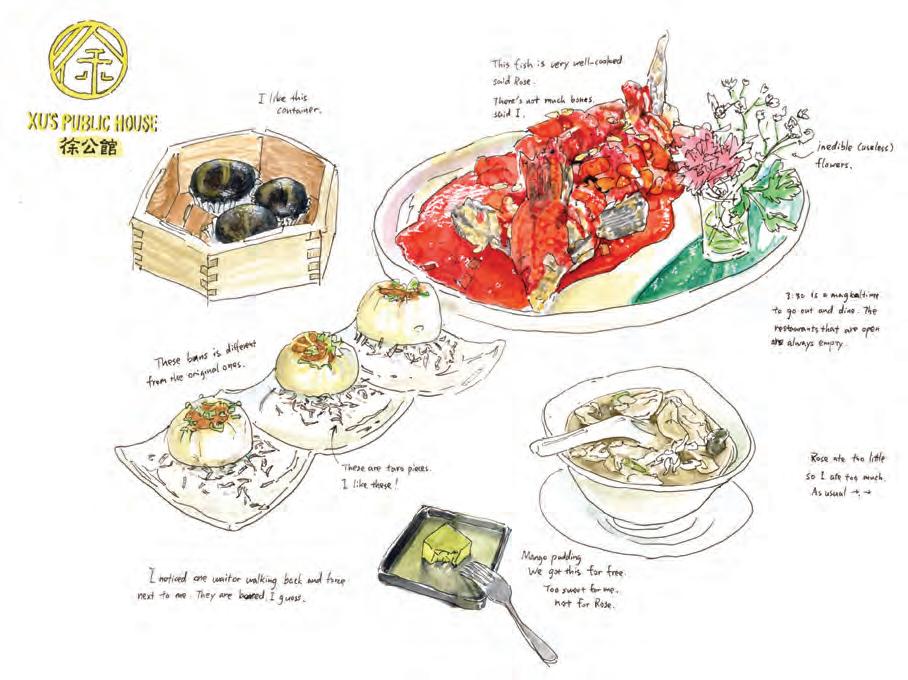

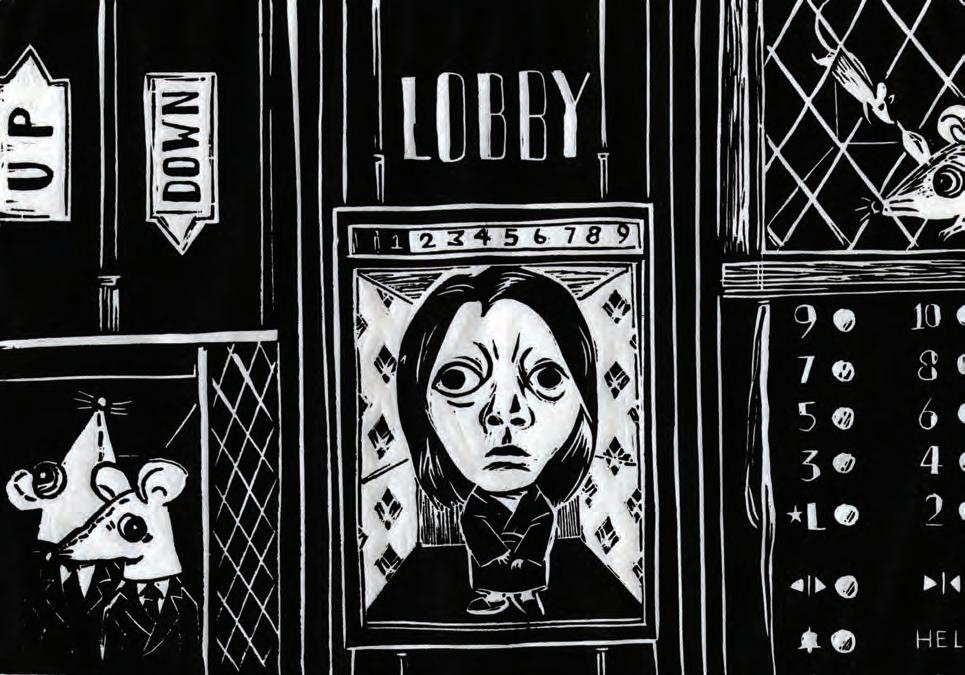

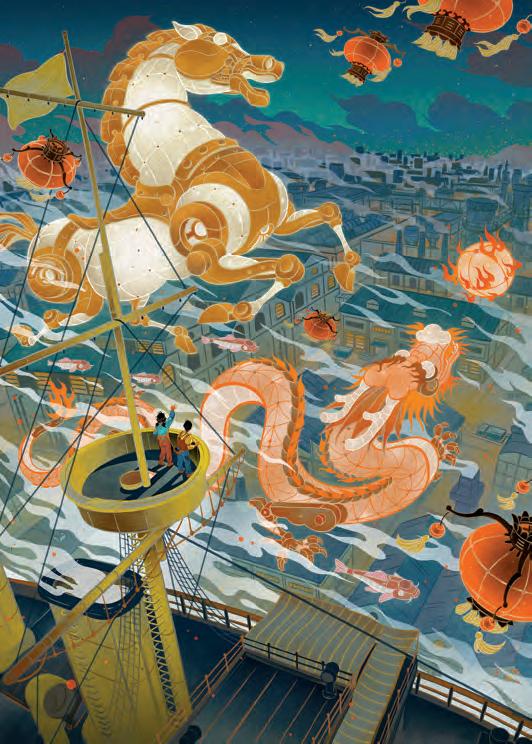

[5] John Han

CREATING

AS A MARATHON

There is a quote from Ira Glass, host of This American Life on NPR, that I heard years back and I still think about now when I get stuck in my head feeling unsatisfied with the work I am making.

“All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. But there is this gap. For the first couple years you make stuff, it’s just not that good. It’s trying to be good, it has potential, but it’s not. But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, is still killer. And your taste is why your work disappoints you.”

—Ira Glass

The quote continues to say that what makes creative people different from everyone else is that rather than quit, an artist will take the years of struggle, of disappointment, of self-doubt, and continue to make work that eventually matches their innate taste level, and this only comes from making a lot of work. It is a marathon, not a sprint.

Technology has evolved, industry has shifted, but there will always be someone who wants to get better in order to scratch that specific itch at the back of our brains. But probably what struck me most about what Ira Glass said, what it really meant, was that with time and practice and hard work, my skill level would come closer to my taste level. There wasn’t any trick or quick answer, I just had to do a lot of work and be mindful of my practice. It is from that struggle and hard work that rewards in the most fulfilling way, in a way technology could never shortcut through. The artist you are when no one is watching, the skill you learn so that no one can look and want nothing more than to reverse-engineer how it was made. The trickier part, the part that Mr. Glass doesn’t explain is that learning is lifelong, and the likelihood that artists will ever create work that matches their own expectations of themselves is very slim. So rather than plateau, we could think of creating as a marathon against ourselves, and, once the race is over, we can start training for the next. We all know of the courage it takes to make a career out of art and that includes overcoming self-doubt and intrusive thoughts as you practice your craft.

Kelsey Short

BFA

Comics Coordinator

BFA Comics/BFA Illustration

Portfolio Selections

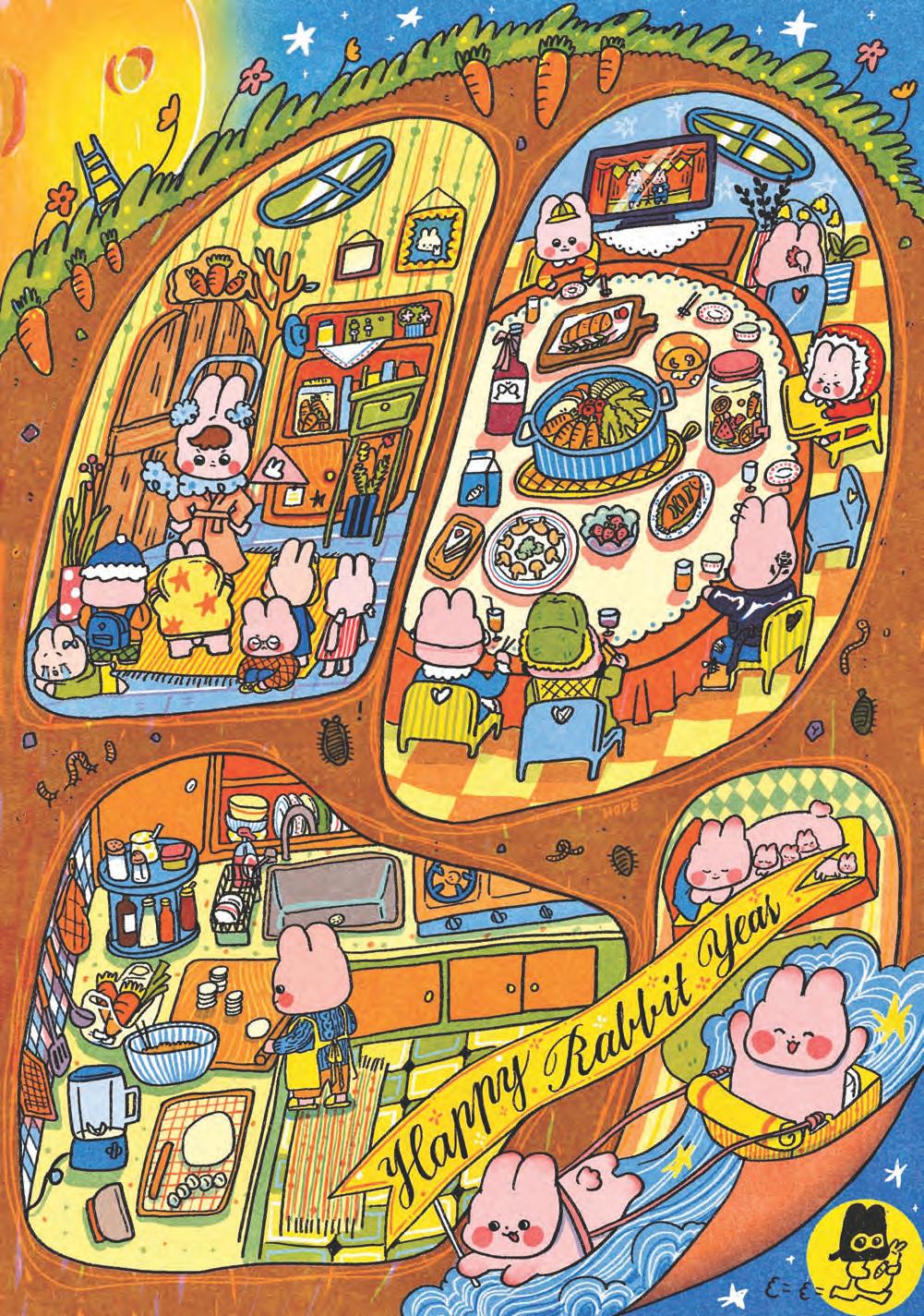

Jiaxi Chen