Keith Mayerson in conversation with

+ Remembering Diane Noomin by Bill

Keith Mayerson in conversation with

+ Remembering Diane Noomin by Bill

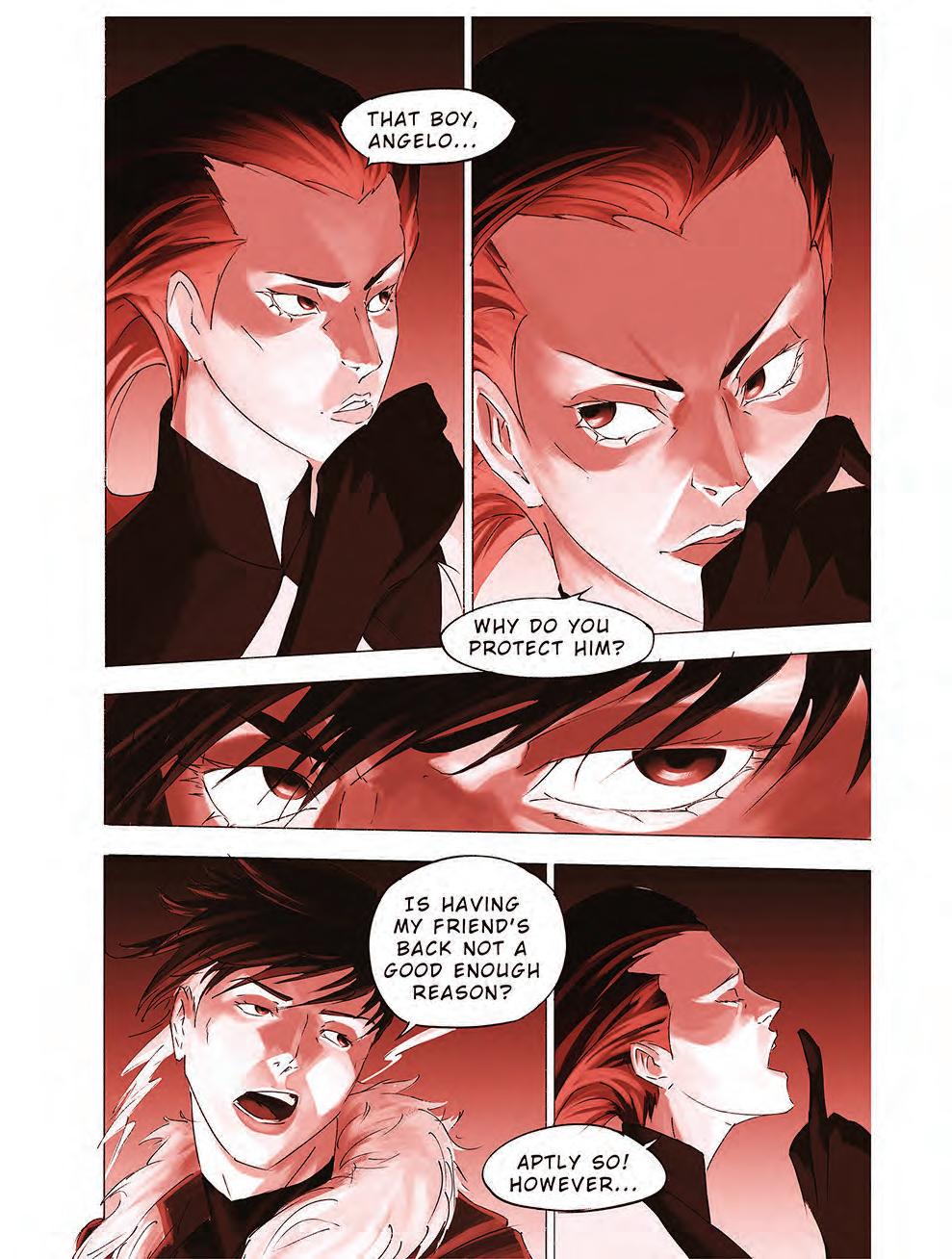

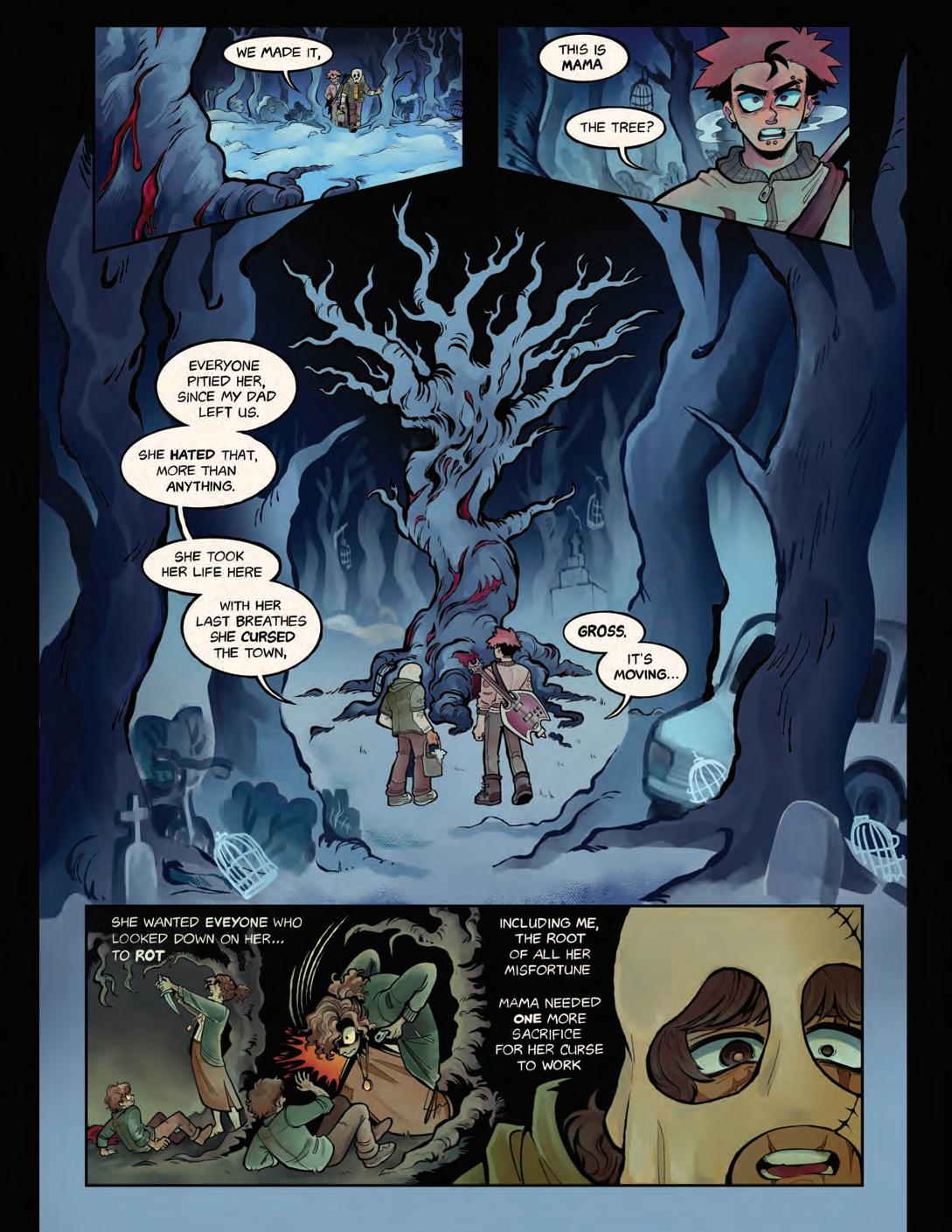

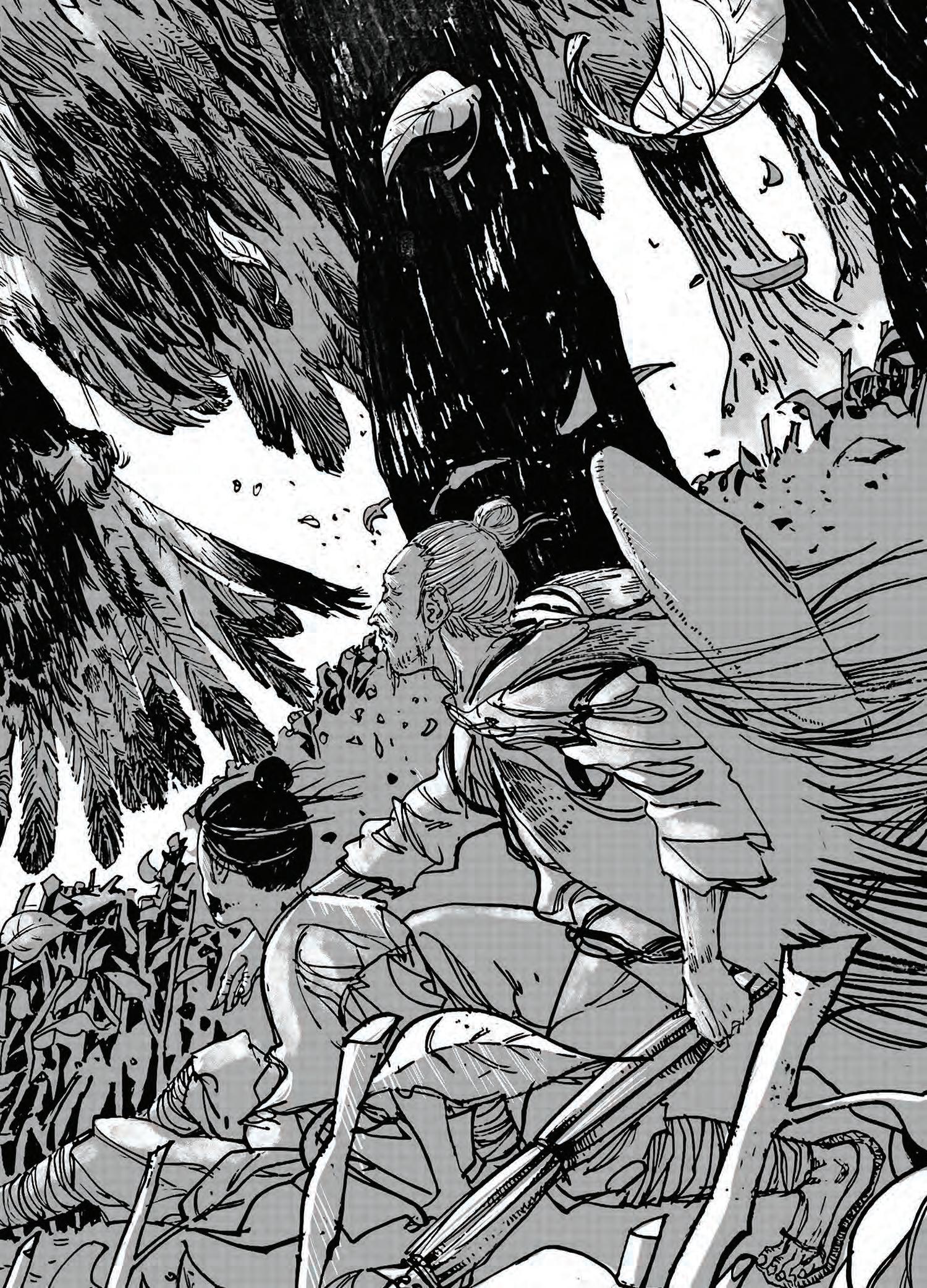

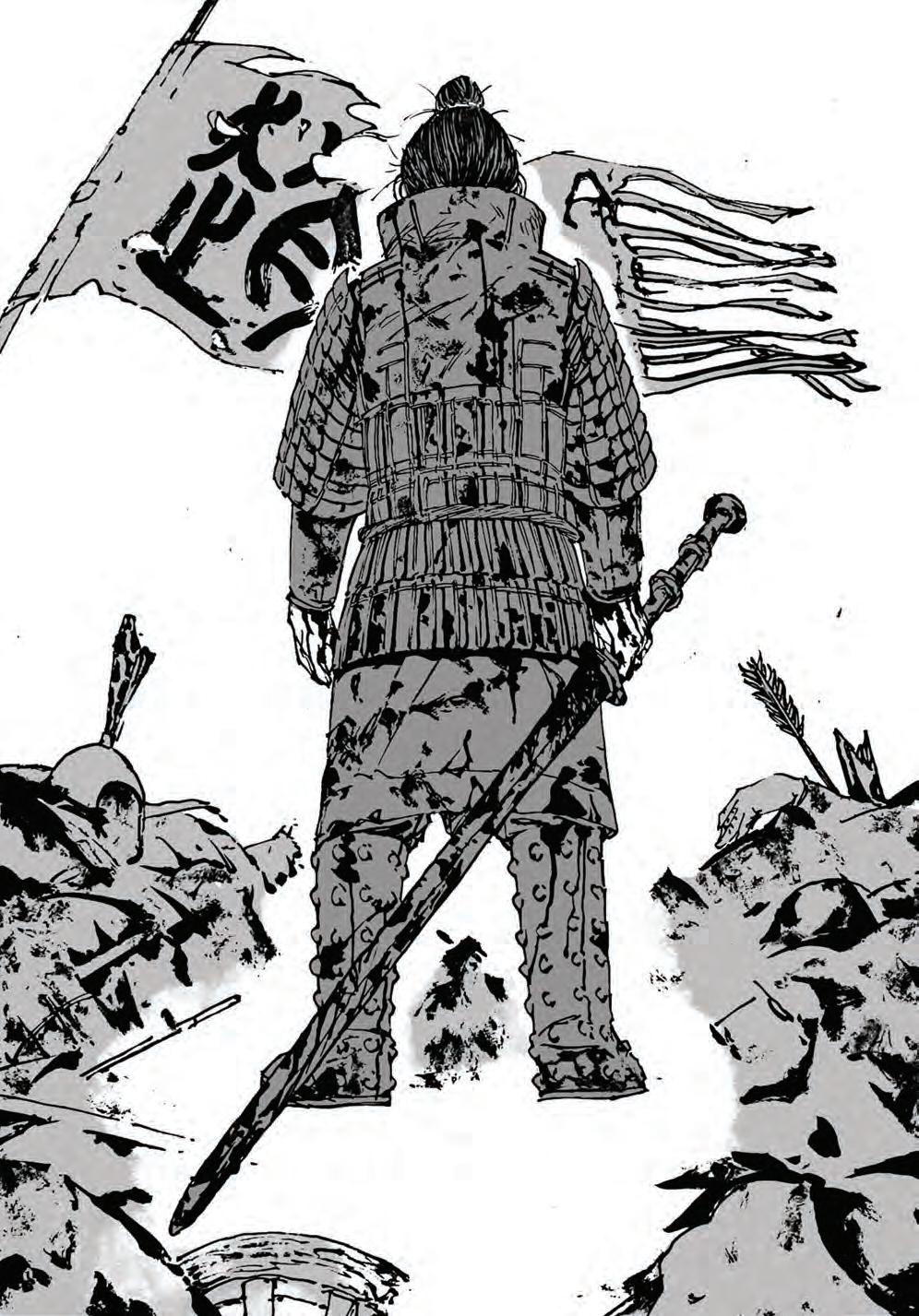

Cal

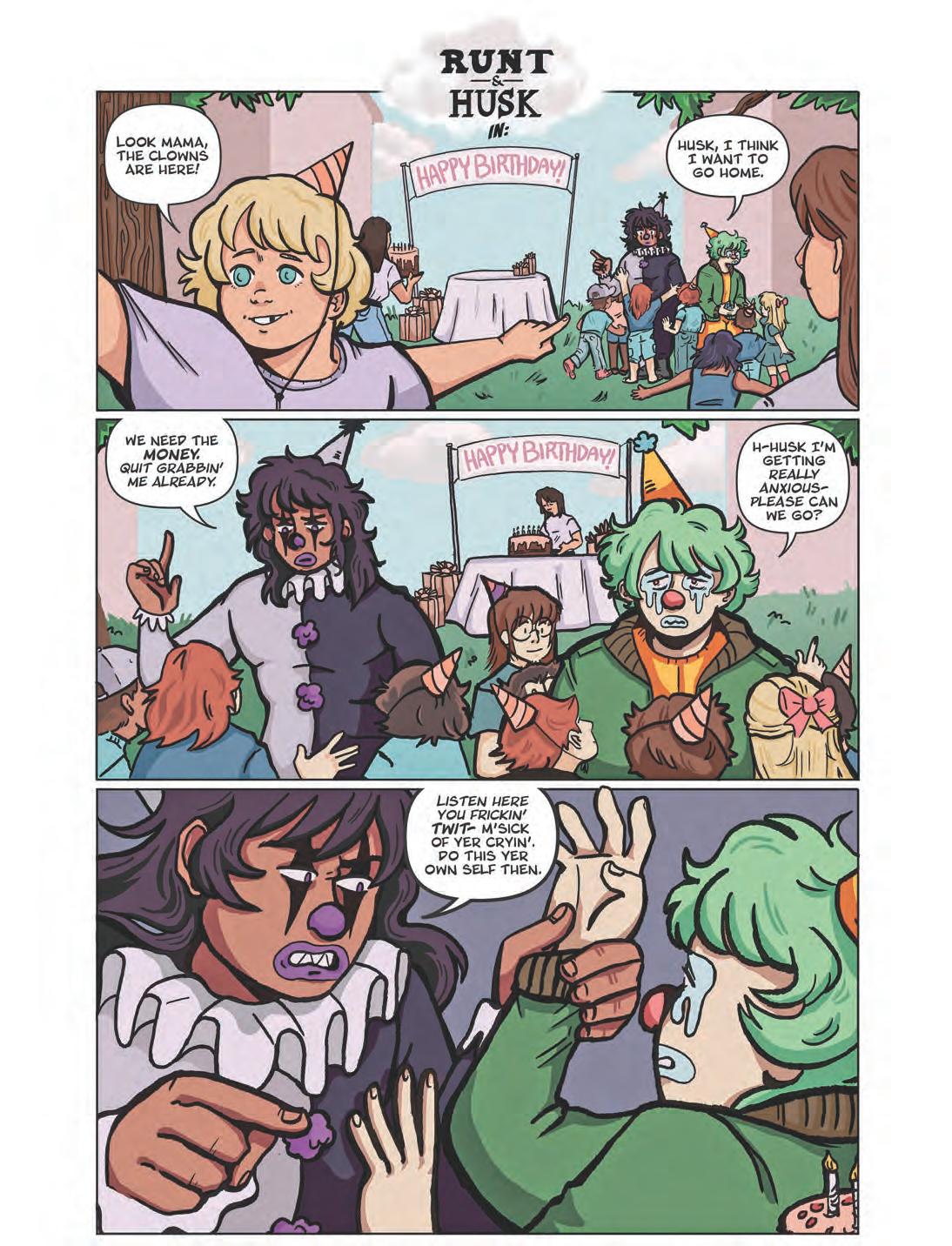

Xiomara Pardo

Zhiyu

Sabrina

Apollo Baltazar

Ian Van Doren

Yoo

BFA Comics Senior Thesis Faculty

JOSHUA BAYER

NICHOLAS BERTOZZI

DAVID ROMAN

Cover: Nahia Mouhica

@PEACHIARE

NAMOUHICA.WIXSITE.COM/ NAHIAMOUHICA

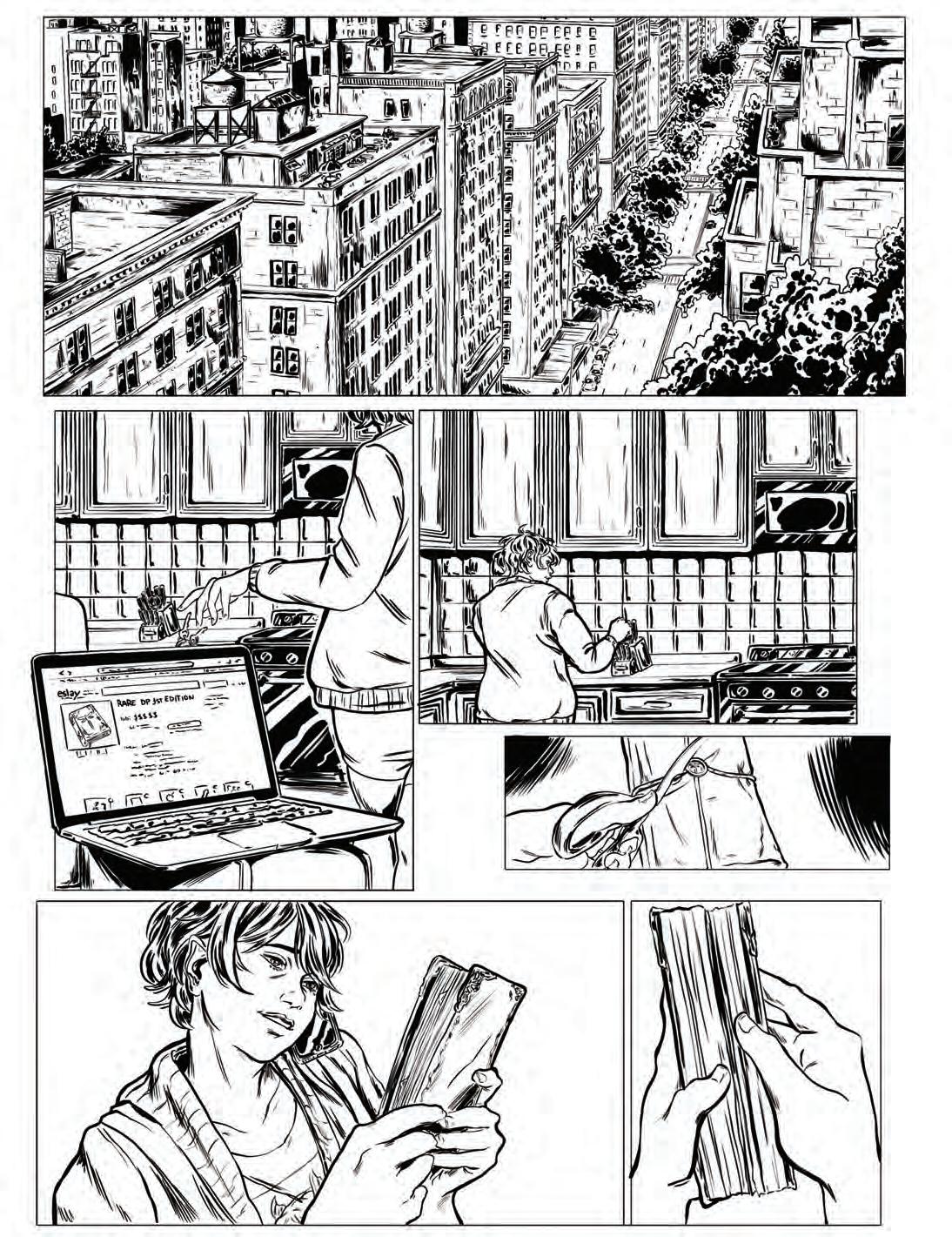

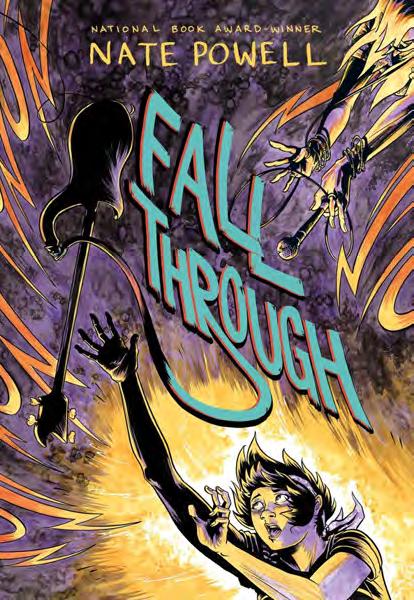

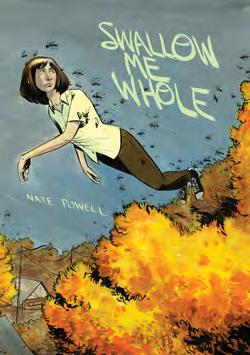

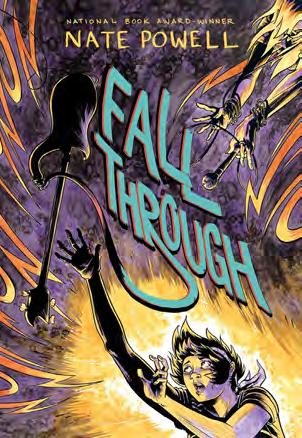

After graduating from SVA in 2000, Nate Powell began a prolific career writing and drawing comics, winning two Ignatz Awards for his debut graphic novel, Swallow Me Whole. He is best known for drawing the acclaimed March trilogy in collaboration with Congressman John Lewis, which has won a number of prestigious prizes including the National Book Award.

Keith Mayerson, Nate’s former SVA teacher, recorded a conversation with Nate for COMX magazine. Keith is the author of Horror Hospital Unplugged, and the recently published “wordless novel” My American Dream. Keith taught Cartooning at SVA from 1994 to 2016, was Cartooning coordinator from 2005 to 2016, and is now professor of art at the University of Southern California (USC), where he began a Visual Narrative Art program and minor.

KEITH: Nate, it’s great to see you! Remind me, where were you living when you were in high school, and when did you graduate? And how did you end up at SVA?

NATE: That was ‘96. I’m from Little Rock, Arkansas. In my senior year of high school, I had an existential crisis where I listened too much to the prevailing wisdom of my parents’ generation, and, despite the fact that my lifelong passion was comics, I hadn’t really thought about anything that I was going to do to continue to hone those skills. I wound up signing up to go to George Washington University in D.C., which, thankfully, had a pretty good drawing program. But the existential crisis hit, and I was like, “I know what I have to do!”

I broke it down to my parents. I immediately transferred to SVA for my second year of college. So I had you in ’98 to ‘99. It seems unreal that I only had you for one school year, because your class was the vortex around which so much of my other classwork revolved.

KEITH: Wow, thank you! Probably you were in sophomore Principles of Cartooning.

NATE: Right. Since I got all my humanities classes pretty much done in my freshman year of college, I had, like, 18 studio credits every semester junior and senior years and was just extremely focused on integrating any class work and lessons into the comics that I was already doing on my own time.

KEITH: How did you know about SVA, back in that era?

NATE: Comics were running really deep throughout my band, and two of my best friends had already started art school. I heard about SVA through Mike Lierly, who was in your class as well. I kept getting word about teachers, classes, projects and stuff that was going on at SVA. It was kind of a no-brainer. Mike and I immediately combined forces and decided we were going to move to New York City together to continue the path that comics had opened up for us.

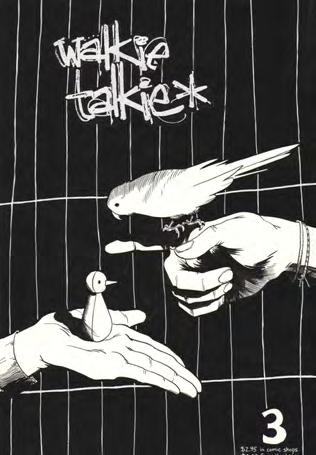

KEITH: Being in a band was really important for you then, and I know you’re about to publish a book, Fall Through, about your punk rock years, told through different personas, coming out around the same time that this interview is going to be in print. You would tour with your punk band and sell your issues of Walkie Talkie to promote your work. Comics are like punk rock in that they’re really about speaking to your community, to help people relate to one another through the “music” of your drawing and writing.

NATE: Punk, in essence, is a folk art. The people who consume and view and engage with the art are typically also the people making the art. It works great in terms of people finding and magnifying their voices. At that time, I had given up on being able to make a full-time living out of drawing comics. One reason was

because my entire life was wrapped up in extremely do-it-yourself pursuits, mostly with my band. A lot of my work was structured around what was filling my time, through music and the punk community.

All of my work in comics revolved around the fact that I scheduled my life around being in a punk band—always touring, playing shows or recording. I was rather prolific at the time with comics, but I never did a story longer than 50 pages because of that.

I stopped being in my main band. All of a sudden, I had as much time as I needed to make a story, whether it was 50 pages or 500 pages. It was such a major shift in how I organized my time and what I expected of the work I made in comics.

I moved to Kansas City for a bit, then started hop, skip and jumping across America, living in Michigan, Massachusetts and Rhode Island, before settling here in Bloomington, Indiana.

KEITH: All inexpensive places to live, which is healthy for a cartoonist, especially when you’re starting out. Comics are not provincial, like in the fine art world, where you need to be in New York, or L.A., or a place where there’s a marketplace. With comics you can live anywhere, as long as you go to conventions and let people know that you’re alive. When you were touring, you were also distributing your comics, right?

NATE: Yes, my band’s first tour in ‘97 was my first experience actually making my books accessible to people who did not live in my home state of Arkansas. It was still very much a do-it-yourself operation, in that I was physically handing copies of my comics to people at gigs in basements or living rooms. It expanded from there.

KEITH: How did you end up settling in Bloomington?

NATE: One big reason is, during those very intensive years of touring, we became deeply embedded in the worldwide hardcore punk underground. Bloomington remains a really strong punk hub. I knew that it was a cheap, friendly, supportive place. It’s a college town in a very conservative, mostly rural state, so it had an oasis-like quality to it.

So alongside making comics and doing all this stuff, for 10 years before I started doing comics full time, I was doing direct care and advocacy work for adults with developmental disabilities. I thought it was important to begin to grow some roots here, as a professional caregiver. And then I fell in love and got married. And all that sort of snowballed at the same time that I had an opportunity to take a chance on quitting my day job and doing comics full time. So it all happened really fast.

KEITH: Our class was a particularly great class, right? I was thinking of the other band that had a great cartoonist in it, My Chemical Romance.

NATE: Gerard [Way] started at SVA the year after I was done there. We had a lot of crossover through friends and classmates from the in-between years, like Becky Cloonan.

KEITH: Wasn’t Farel Dalrymple in that class?

NATE : Farel was, and Brendan Burford, and Carlo Quispe, a fantastic cartoonist. And letterer extraordinaire Cory Petit! I’ve kinda fallen back in love with the X-Men. I’ve re-read thousands of pages of X-Men. All of these books are lettered by my old friend and classmate, Cory, and he’s an incredible letterer. Lettering is the glue that holds comics together on a formal level. I think my Eisner nomination for best letterer is the one that is the highest honor for me. I’ll read X-Men and really focus on Cory’s lettering and what he’s doing, page by page, and it’s been

very helpful for me as a cartoonist.

KEITH: Superhero comics are the Wall Street of the comics world. We need superhero comics to do well. They keep the comic book stores open.

SVA has an older history, where comics had become sort of misbegotten within the administration. I’m so glad that you guys were the first generation rebooting it. I started teaching there around that same time in ‘96. We sort of revolutionized the comics program to where it is today, that they could say it’s the Harvard of comics colleges. Not that there are many comics colleges to compete with, but it’s really a great program. My job teaching there, growing into being Cartooning coordinator, and Tom Woodruff taking over the program and really focusing on comics and making it a much better program, led us to where we are now.

Then in 2000, there was a sea change where all of a sudden, half my classes, wonderfully, were women.

NATE: It was a revolutionary shift. Then if you skip ahead even just five years, the impact that Raina Telgemeier made, transformed that sea change into a new generation of creators. It’s amazing now to be 18 years past that point and realize that Raina’s readers are adult creators now!

KEITH: There was a group at SVA called Estrigious. It was Becky Cloonan and her friends. They had their own website— before people really had websites—that would get like a thousand hits a day. They would do compilation comics and go to comics fairs together and support one another.

The male equivalent of that was Meathaus. Were you a part of Meathaus?

NATE: Yes, I was back in Arkansas and started corresponding with several of the Meathaus folks. I contributed to two of the issues between 2001 and 2002. I consider the Meathaus crew to be my

peer crop of cartoonists from that sliver of time. Farel was in it and James Jean, Becky Cloonan, Esao Andrews, and Tomer and Asaf Hanuka. And Dash Shaw and Tom Herpich. It had a really solid lineup.

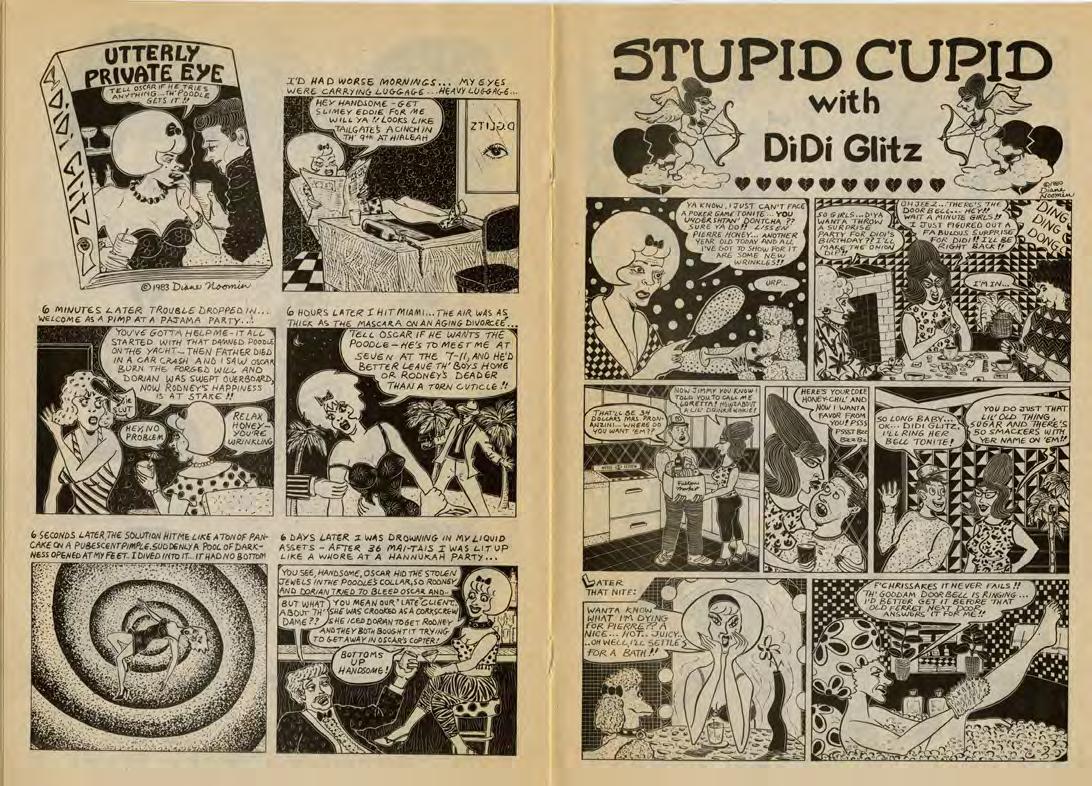

KEITH: There is strength in numbers. All great art movements happen with like-minded people, oftentimes who went to the same art school. The surrealists all left a school that they didn’t like, together. R. Crumb and the underground cartoonists got together. The women of that generation, with Twisted Sisters and Diane Noomin—who also was a wonderful teacher at SVA—did their own anthologies.

With your class, I still remember the real feeling of … a commune of cartoonists and how you guys were so dedicated each week to bringing in work and putting it on the wall. Was Steve Uy in that class?

NATE: Yes! He brought the thunder more than any other student. You were like, “Okay, you guys, we’ve got this 16-page story you’ve got to turn in. What do you have, Steven?” And he’d be like, “Well, I completed this 80-page book. It’s fully inked and lettered. I’ve already printed it. Would you like a copy?”

KEITH: Yeah, Steve got hired right away! He was at the bar near SVA after graduation, and he had his portfolio with him, and he was with a friend who was there with a Marvel editor, and the friend said, “Marvel editor! You should check out Steve’s work!” The Marvel editor looked through dozens of pages in his portfolio, and was like, “Yeah, I’ll hire you right away.” It’s usually not like that!

NATE: Right on. Luck is a real thing. There is so much to be said for diligence and discipline and vision, but you always have to be ready for unexpected stuff to happen just whenever, and be open to it changing the course of your life.

KEITH: Molly Ostertag did a comic called

Strong Female Protagonist in their sophomore year at SVA. They continued it for three years, and then, with the Kickstarter campaign, they published it.

And they got, like, 60 or 80 thousand dollars to publish their graphic novel, and I remember being at New York Comic Con with Cartoon Allies kids, and Molly was at the Top Shelf booth with their books. And I said, “Top Shelf! You’re distributing Molly’s book? They began this in my class!” And Top Shelf was like, “Yes, we’re so proud of it.” First Second was right across from Top Shelf’s booth, and I was like, “Oh my gosh, that’s my student, Molly Ostertag.” And they were like, “Oh, yes, we have them contracted with us for next year.”

NATE: Those Witch Boy books are beloved classics here in the house. The Witch Boy trilogy has influenced my more recent fiction; I’ve become more embracing of genre. It’s been very freeing. Those books are one of the best examples of genre.

KEITH: Witch Boy took ideas of genre and, within the genre, critiqued it … Why can’t boys be witches? It’s very gender-fluid, and it really helps the world. Witch Boy, I think, was picked up by Fox Animation. Molly’s partner, N.D. Stevenson, did art direction for She-Ra, which, I think, is kind of like Becky Cloonan doing Conan stories; feminist creators retelling these very masculine kinds of adventure narratives.

NATE: And N.D. Stevenson’s work on She-Ra stands the test of time, as it’s a full execution of classic themes and tropes, throughout hero narratives, and being able to do it in a loving way that also confronts the source material, it’s able to turn it on its head.

KEITH: Cartoonists make great storyboard artists. We mentioned Tom Herpich; he worked on Adventure Time and Steven Universe, along with Hilary Florido. Rebecca Sugar from Animation at SVA

was the head of Steven Universe.

NATE: My kids are eight and 11 now and watching Steven Universe with them has been fantastic. It’s been great being able to recognize that this is a radical shift in the expectations of narrative and emotional weight and in what is expected when we’re talking about narrative conflict.

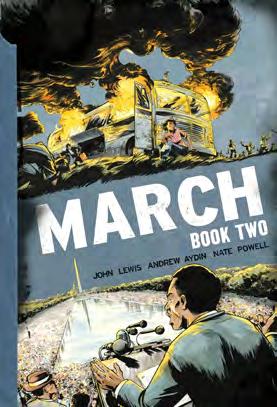

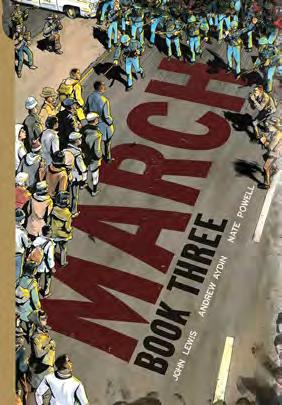

KEITH: Nate, what did you do between graduation and March? March in particular, for our politics right now, is so pertinent. With Congressman John Lewis, that collaboration, how did that begin?

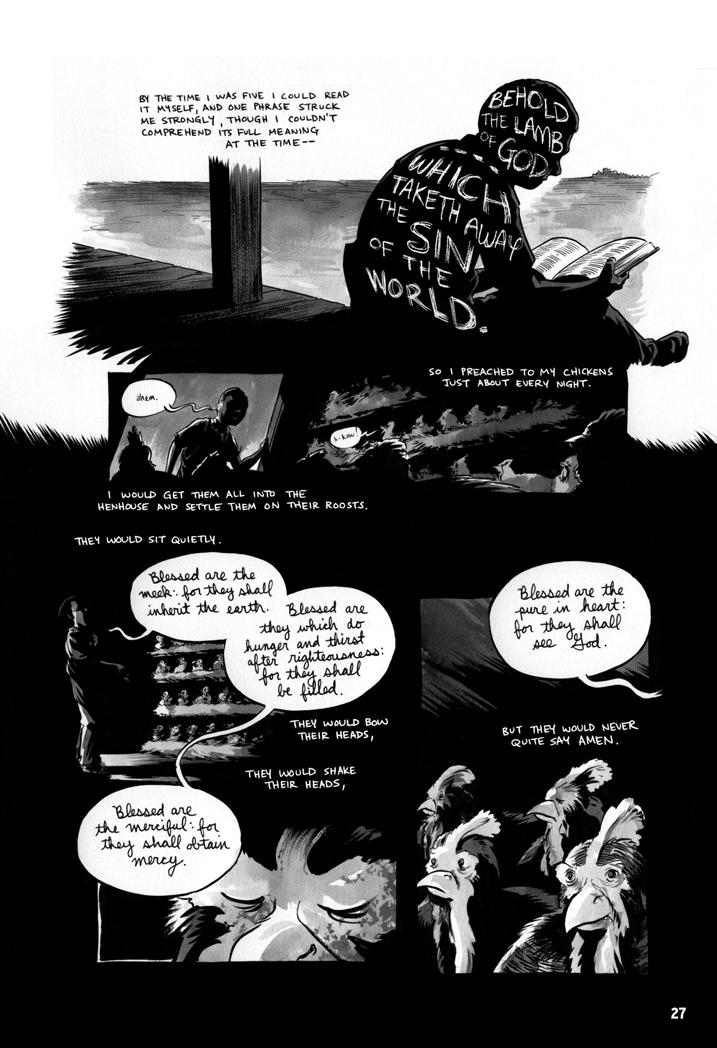

NATE: My first graphic novel came out in 2008, Swallow Me Whole. It took about six years total to make it happen. Once it was released I was surprised that people were actually reading it and were affected by it.

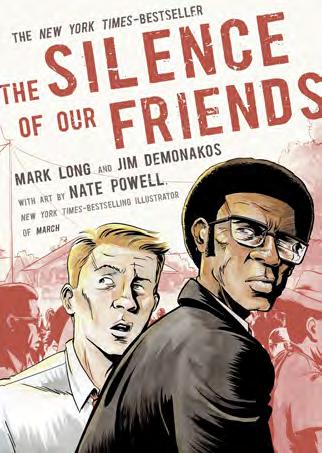

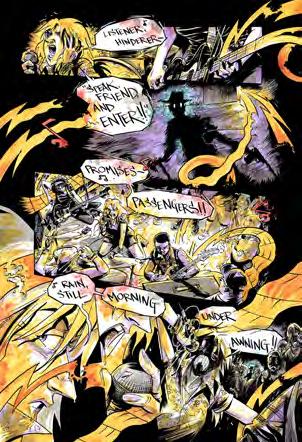

What allowed me to quit my job to try being a full-time cartoonist was drawing a graphic novel for First Second called The Silence of Our Friends, which revolved around writer Mark Long’s life growing up outside of Houston in the sixties, set against the backdrop of a forgotten moment in the civil rights movement. I consider my work on The Silence of Our Friends as a boot camp for the March process, especially the reference and research, and issues of authorship, voice and privilege that went into working on March

Andrew Aydin, the March co-writer, was a staffer for Congressman Lewis. They’d been working on the script for a couple of years. They cut a deal with Top Shelf to publish March, but with no artist. Chris Staros from Top Shelf called me up about a week later and suggested that I try out. One reason was because of my previous work blending fiction and nonfiction. I had done a little bit of it in short-form comics, journalism and nonfiction work for Brendan Burford’s Syncopated anthology.

KEITH: He was also the editor at King Features Syndicate.

NATE: Yes, and a real gem of a person. I did some demo pages from the script, and very quickly we realized that we clicked well together. I’m also a Southerner; as a kid, I lived in Montgomery, Alabama. My parents are from Mississippi. So it was very important that I had a lot of cultural and historical familiarity but also topographical familiarity, in terms of what kind of dirt, what kind of

roads, and what kinds of plant life.

One reason why they wanted me to draw the March trilogy was because of my ability to balance this dreamy, intuitive, very personal kind of storytelling with a more objective, realistic, cartooning approach. So whenever I could, I was encouraged to lean on my own experiences and memories of living in the South in the eighties and nineties, especially watching these social and political shifts, which foreshadowed this dangerous return of very regressive outright fascism in the 2020s.

KEITH: My parents are also from the South, and I relate to that, too, in terms of my legacy. They got the hell out of there in the sixties, when they saw their friends become fascists.

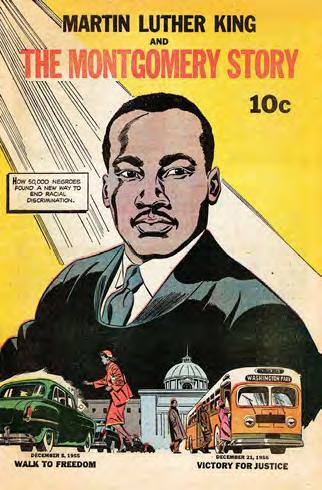

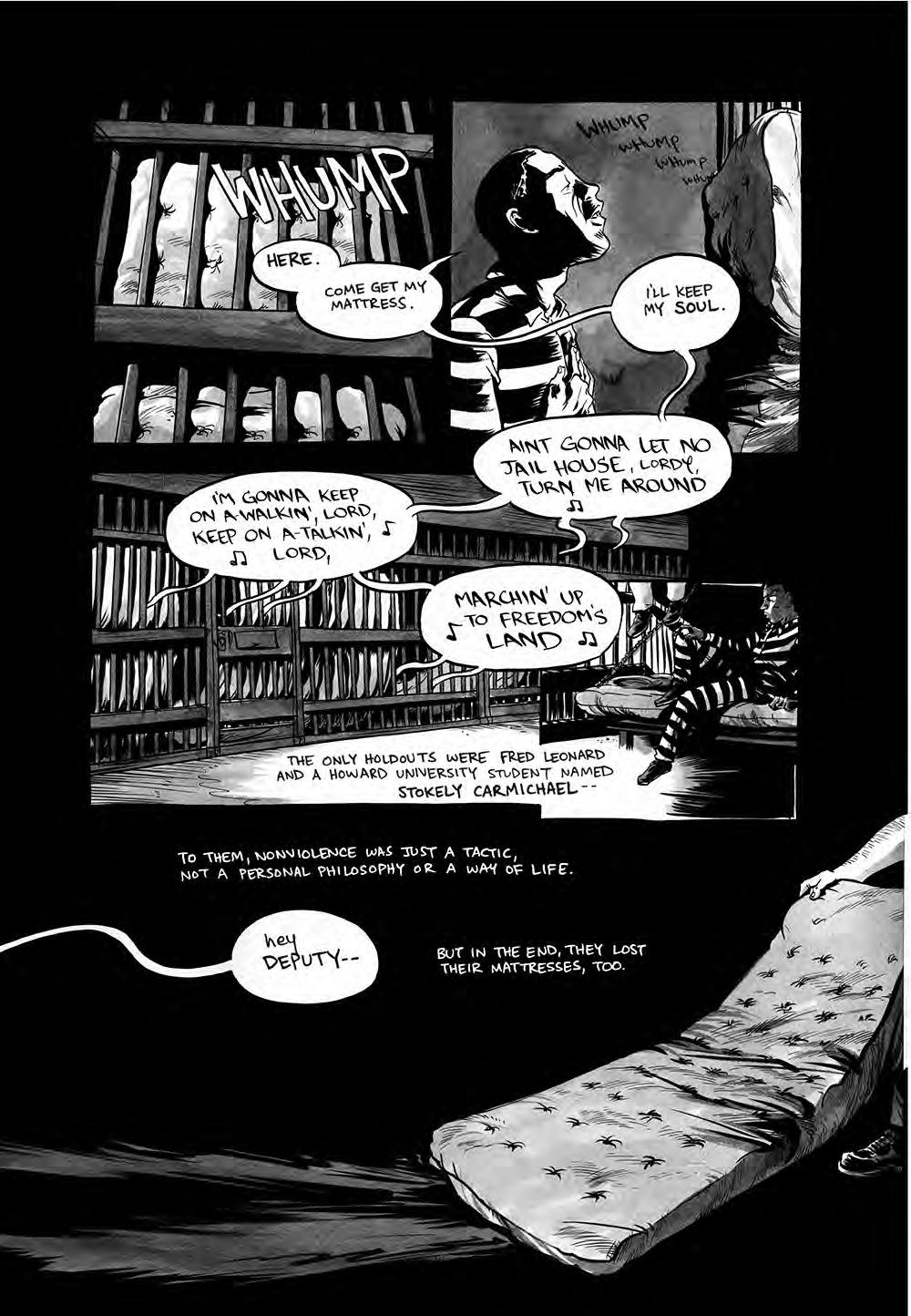

A lot of people don’t realize that one of the reasons John Lewis got into the civil rights movement was because of a comic, right? The Montgomery Story And it seems like your covers, and the color choices were emulating The Montgomery Story

NATE: Yes, Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story was the impetus for March. It was this 1957 comic that teenage John Lewis used as a training primer in nonviolence workshops in Nashville. Dr. King and other early nonviolence leaders distributed the comic out of the trunks of their cars and in church basements during training sessions. It directly impacted not only the civil rights movement but also a variety of justice, equality and pro-democracy movements throughout the world, like Cesar Chavez’s labor movement…. It even had bootleg translations in Arabic and Farsi during the lead up to the Arab Spring in 2010 and 2011. It has a fascinating history of its own, and that history is still alive.

One of the big reasons why March happened was because John Lewis told Andrew about this comic’s role in his legacy and how baffled he was that this

level of significance would essentially be relegated to obscurity.

KEITH: It’s really well written, and drawn, I think, by an anonymous illustrator.

NATE: Andrew did his graduate thesis at Georgetown on that comic, and in 2018, he actually had a face-to-face meeting at Dragon Con with cartoonist Sy Barry and confirmed that he was, in fact, the artist on the book. But it was a Silver Age book, and oftentimes creators were entirely uncredited.

KEITH: Now March is read all around the world and is on so many syllabi in high schools and colleges. It’s so neat to see March on bookshelves behind people talking on MSNBC. At the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, I had a meeting with Judy Baca, the great Latinx muralist. I walked in and turned the corner, and behind her desk, she had a blow-up of one of the pages from March

NATE: A county defender in Minnesota used March: Book One to be sworn into office just this year.

KEITH: I had Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly come to talk to my students at USC about the subversive power of comics and to talk about Maus [Spiegelman] realized it’s so important to keep talking about it because we have

to convince 40% of America that Nazis are real, and they exist and they are evil. And they’re in America.

NATE: Comics are a very easy target for this current wave of censorship. People insist on comics being just one thing that they can define in a narrow way. It’s really interesting to butt up this limitless communication tool against the insistence of a lot of unfamiliar people to define it. Comics are a medium and a language on their own.

Last year, when the organized bookban movement started really in earnest, I did some shorter op-ed comics for The Washington Post and for The Nib. Then, I went on the counteroffensive. I made a poster that the American Library Association distributed that provides a simple set of unique strengths that comics has pitted against the unique weaknesses of these book-banners. I thought it would be nice to be able to define what comics is, how it works, and to know what the benefits are. I think it’s important for comics lovers and creators to go on the offensive and get familiar with how to talk about how comics work and why they are valuable.

The older I get, the more I realize that it’s important to recognize when you’re simply out of touch with something and when it’s time to listen, in terms of literacy, in terms of new ways of telling and absorbing stories, and new ways of thinking about the world.

KEITH: Do you have any good advice for young cartoonists?

NATE: The number one thing is to show up. I know that we’ve all had a massive setback, socially and community-wise with the last three years of the pandemic, living in holes scattered across the globe. But it is important that we begin to truly reclaim our community spaces. Comics is an industry and an art form, but comics is also a community.

I toiled and self-published and put out one-off books for, like, 15 years before things really started clicking. But what’s important is that you are ready to spend an entire paycheck getting some convention table space and printing up some comics to sell. A lot of it is about being in the same physical space as other people. Over time, even if you’re not selling very many books, people remember you. Believe it or not, they are already a little familiar with your work. It may not feel like it, but it’s absolutely true. Showing up is really important.

KEITH: Nate, you’ve shown up in every way. You’re keeping at it, making these stories that really matter, for the art of it and for telling stories that make the world a better place.

NATE: Thank you! Another thing is, as you’re working on your big idea and really trying to make it be the thing that

rocks the world … one of the biggest mistakes is betting everything on that one big idea and languishing, sometimes for years, because it’s not hitting. What’s more important is the first question people will ask: “What are you doing next?” People want to know where you’re going from that, and that has a lot more currency than the thing that you’re pitching around to get published. People want to know what’s in the future more than what is in their hands at the comic convention.

The other major thing is … whenever I talk to young people, I try to adjust to the reality of what it means to sign up for higher education and being able to not only pursue their passion but find a way out of a potentially very risky situation in terms of taking on student loan debt. It’s something that can’t be ignored. Very few cartoonists make a full-time living off of comics. And that’s absolutely okay. The vast majority of cartoonists, as you said, have day jobs, whether it’s in the arts or teaching. And this returns to what DIY punk means to me. People feel like they need to make a comic, to let something out or to tell a certain story… It must be made, no matter what it takes, and it’s important to embrace that. What’s important is that the work comes first; the work will find a way. Don’t sweat your work, your big idea, your emerging projects as a means to an end, in terms of paying your rent. Comics is a life journey. Sometimes that takes five or 10 or 15 years. But don’t sweat that. What’s important is what you’re putting on the page.

KEITH: That’s right, that’s the integrity of comics.

NATE: I’m a full-time cartoonist. But that means a different thing for everyone. For me, it means that I do my weird, usually magical realist fiction that has a smaller readership. That’s my real passion project. Then, I have a second project I usually do concurrently that’s nonfiction-based,

“Comics is a life journey. Sometimes that takes five or 10 or 15 years. But don’t sweat that. What’s important is what you’re putting on the page.”

—NATE POWELL

usually with another writer, that mixes more of my worldly concerns and that by balancing those things I’m able to make it. So I put out a lot of books; I think I’m about to put out my nineteenth and twentieth book-length comics in the next year.

But what’s wild is, I’m turning 45 this summer. I’ve got, like, 50 more years. There’s no health insurance or retirement plan for cartoonists. So I’m gonna die at the drawing table.

KEITH: Charles Schulz did that.

NATE: But that’s fine with me, recognizing, like, what do you do when you have 45 or 50 more years of comics to do? This year over the winter, I had a mini existential crisis. For the first time in, like, 25 years, I was like, “I’m out of ideas. Inbox at zero!” But then one day an idea popped into my head. I’ve been noodling at it over the last couple of months, and very recently, I’m like, “Wait a minute. I’m not out of ideas. This is the next book.” I think it’s important to impart to students that this is something that happens along the way, and don’t beat yourself over the head about it.

KEITH: And just love the meditation of doing it. I’m co-editing a book for Fantagraphics, two volumes of outsider cartoonist Frank Johnson’s work. He

was an itinerant musician; he would travel and play banjo on radio stations back in the thirties. But lo and behold, when he died—and his wife didn’t even know—he’d done thousands of pages of comics! He just loved being in that world. It was a meditative space. And it seems like you must be in that space, where it’s your safe zone to be at your drafting table, rendering, right?

NATE: I’m a big believer in compartmentalizing your time. The more I can compartmentalize what I do, the happier I am, instead of trying to live like a chaotic artist, looking for flashes of genius. Once my kids are at school, between nine and three, I do nothing but work furiously, so that I’m able to switch back over to the dad zone for the rest of the day. It has made my studio into such a refuge and such a happy place because I allow myself to leave it at an appropriate time, so that I miss it, and I can’t wait to get back to it.

KEITH: Any last words of wisdom?

NATE : Yeah, just stay loud and stick together. We’re in for a turbulent decade-plus ahead of us. That’s not a joke. But we’re gonna win. The fascists are going to lose. Keep on doing the weird stuff that is [off] kilter. It requires your unique voice, and you just being you.

KEITH: Sadly, we’re in this politically turbulent time. But as Dr. King said, “The moral arc of justice…” What’s the exact quote?

NATE: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” The important takeaway here is that it does not bend by itself. We bend the arc. So, please, actually show up, and bend the arc.

KEITH: Comics are such a democratic medium, and we need them, seriously, to help save democracy.

NATE: Definitely. Yeah. Not an exaggeration.

COMX magazine thanks Nate and Keith for sharing their thoughts and memories with us.

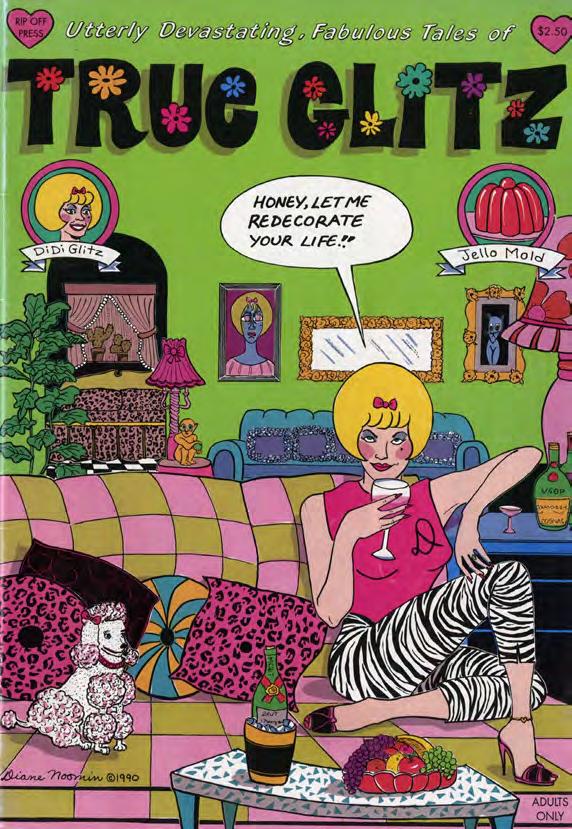

In September 2022, the SVA community lost Diane Noomin, a groundbreaking cartoonist who taught students a subject she nearly pioneered decades ago, “Personal Comics.” As an artist, Diane is remembered for the body of comics she drew that spoke so eloquently in her own voice. As a teacher, Diane helped SVA Comics students find their voices. And in fact, lifting up the voices of others was a substantial part of her career. In 2019, Diane published her last book, Drawing Power, an anthology of autobiographical comics about sexual harassment and sexual violence featuring personal comics by more than 60 diverse women—including Diane. In her preface, she wrote that the #MeToo movement had motivated her to take on this project. “I’m a cartoonist and an editor,” she wrote. “The only logical way I could respond to this onslaught was as a cartoonist and editor.” It’s important that we remember Diane the way she described herself: as both a cartoonist and an editor.

In 1972, Diane was a young art school dropout in San Francisco, filling up notebooks with drawings and poems. By a great stroke of luck, she met Aline Kominsky-Crumb (then Aline Kominsky) at a party, and Aline invited her to the first organizational meeting for Wimmen’s Comix, a collectively run underground comics anthology series exclusively featuring

work by women. When Wimmen’s Comix #1 was published in 1972, it was only the third such publication in American history (after 1970’s It Ain’t Me, Babe and alongside 1972’s Tits and Clits #1). It also proved to be the most long-lasting, publishing 17 issues over 15 years.

Diane and Aline both published work in early issues of Wimmen’s Comix, but, by 1975, they felt stifled by the perceived pressure to produce work for the publication that upheld the ideals of what was then called the “Women’s Liberation” movement (and which we now identify as second-wave feminism). The following year they broke away from the collective and published their jointly created, one-shot comic book Twisted Sisters. That comic book’s cover greeted readers with a self-portrait by Aline, seen seated on the toilet in a moment of physical self-loathing. Twisted Sisters was a space where Diane and Aline could give full range to their thoughts and feelings—lustful, petty, self-deprecating, joyous and sad—and articulate the full range of their beings without limits. Aline’s stories stuck close to the core of her career-long autobiographical self-exploration in art. Diane spoke to readers through the persona of “DiDi Glitz,” an alter-ego based on the women Noomin had observed growing up on Long Island.

In the years that followed, Diane continued to publish

stories in various comics and edited Lemme Outa Here! (1978), a one-shot anthology satirizing the false dreams and stifling environment of American suburbia. In the years that followed, the underground comix milieu dissipated, and independently motivated comics moved from the magazine racks of “head shops” that catered to countercultural tastes to the back shelves of a rising network of dedicated comic book specialty stores, which principally catered to male collectors of commercial genre comic books.

As a new “alternative” comics scene developed, Diane noticed a rising generation of young women artists publishing their work in independent comics like Weirdo, in magazines like the National Lampoon, in hand-stapled mini-comics, and elsewhere. These women were producing great, individualistic work that exhibited precisely the kind of narrative freedom and aesthetic diversity that motivated Aline and Diane to publish their own comic book in the first place. Diane saw these artists as kindred spirits, fellow twisted sisters. Diane knew this work was good and that it was important, and that it was saying things that weren’t being said in the larger culture. But Diane also perceived that this work was not going to find its ideal appreciative audience languishing in the backs of male-dominated, fan-oriented comic book stores. Diane wanted to show

this work to an outside world of potential readers who might be ready to read adult comics made by talented women speaking impolite truths. So she reinvented Twisted Sisters to create a better platform for their voices.

Against all odds, Diane made a deal with Penguin to publish a book—Twisted Sisters—that would collect work made by women working in the alternative press. That first Twisted Sisters book collection appeared in 1991, and it’s important to understand its significance at that moment. It can be difficult now to remember how few adult-oriented comics were published by mass-market publishers and distributed to mainstream bookstores in 1991. Certainly, Art Spiegelman’s Maus had been very successfully published in two volumes in 1986 and 1991. Spiegelman and his partner and collaborator Françoise Mouly had already brought their comics anthology series RAW to Penguin and had edited a handful of striking individual book projects at Pantheon and elsewhere, featuring work by Charles Burns, Ben Katchor, Gary Panter, and others. Doubleday had published two collections of Harvey Pekar’s autobiographical American Splendor comics as well as Larry Gonick’s Cartoon History of the Universe. But in 1991, there was little else on the shelves of American bookstores that didn’t look like a Garfield collection or a Batman book.

In that context, it remains striking how uncompromising that first volume of Twisted Sisters was in its editorial choices, anthologizing riveting, risky stories by MK Brown, Julie Doucet, Phoebe Gloeckner, Krystine Kryttre, Dori Seda, and others that had previously been published in comparatively obscure comic books and anthologies. It also remains clear just how seriously Diane took editorial work. She spared no effort to present this work to a potential audience of serious, adult readers who might not otherwise know that these comics even existed—and likely hadn’t thought much about the artistic potential of comics. Twisted Sisters featured blurbs by Spiegelman and Robert Crumb, the two artists making comics for adults who were most likely to be recognized by a general audience. But even further, the book included a blurb by experimental feminist writer Kathy Acker, whose work continues to be rediscovered and studied today, and, across the back cover, in big red letters, an endorsement from pop superstar Madonna, then arguably at the height of her cultural prominence and influence. In securing this promotional quotation, Diane achieved something that even seasoned book publicists can only dream of.

Diane was driven and she pulled out all the stops on behalf of other people’s work. She believed an audience for this work was out there, somewhere beyond the comic book shop. She created a vessel for these comics that was designed to get out into the world, and between the covers, her editorial choices were, as I said, uncompromising. But one compromise is evident: two sexually explicit panels originally published in Young Lust were censored for publication by Penguin. So if Diane was quite early to see the positive potential of working with the mainstream book publishing industry, she also was quick to encounter the downsides of commercial publishing. The book sold out its first print run, but Penguin was in a state of disarray at the time—as corporate publishing companies seem to cyclically be. A new editor-in-chief came in who decided that Penguin was not in the comics publishing business. Clearly, the stigma against comics for adults still persisted in American culture, and so this book that had everything going for it and was selling well did not even go back to press for a second printing.

Nevertheless, Diane still believed in the project and began working on a sequel—this time featuring original work and longer stories. She returned to the independent press, where she knew she would retain full editorial control, and published the second volume of Twisted Sisters in 1994 with Kitchen Sink, one of the few surviving underground comix publishers, and one that had made some inroads into the mainstream book retail marketplace.

As an editor commissioning new work, Diane truly shone in that second volume of Twisted Sisters. Working directly for Diane and producing longer stories at her request, some of the artists in Twisted Sisters 2 made comics that are among the best of their careers—certainly up to that point, at the very

least. These include “Sixteen” by Debbie Drechsler, “Minnie’s 3rd Love,” by Phoebe Gloeckner, and Diane’s own autobiographical story “Baby Talk,” in which she stepped out from behind the persona of DiDi Glitz and told her frank and heartbreaking story of multiple unsuccessful attempts to carry a pregnancy to term.

Diane’s two volumes of Twisted Sisters showed anyone who cared to look how good comics by women cartoonists could be. And a few years ago, with Drawing Power, she reminded us how timely and important they could be, too. As an artist, Diane has enriched the world of comics with her smart, funny and emotionally unflinching work. As an editor, she was always a teacher, even before she joined the SVA faculty. We mourn that she is no longer with us. But her work leaves us all with the opportunity to learn from her example: her keen editorial sensibility, her powerful sense of mission, and the uncompromising, deeply motivated drive she brought to all of her work are her inspiring, insistent gifts to us. We can miss her dearly, and we can celebrate that we live in a world that is better because Diane Noomin was here with us, giving us her all.

FOR THE LOVE OF COMICS

At the end of this year of teaching, I knew it had been a really good year, one full of discoveries and learning experiences for me. The indicator was: when summer came, instead of dropping school stuff like a hot potato in favor of rest and recreation (you know that teachers look forward to this as much as you do), the first thing I did was look at next fall’s rosters to see if anyone had registered for my classes yet.

Would there be enough enrollment for my classes to run? Would there be some interesting diversity among my students? I looked, and then sighed with relief. All my classes were fully enrolled, with a nice variety of both new and familiar faces, in a great mix of colors and genders. Phew. Good. I get to do this again.

I am very fortunate in that my job is highly addictive. I get to spend my time sharing my enthusiasm for a subject I dearly love—comics. I assign my students comics to read. They read them. Then, they make comics for me to read. Repeat for 30 weeks, with myriad variations.

It helps that comics is such a fantastically layered and eclectic medium. You get out of comics what you put into it, so comics can be childishly simple or thrillingly busy. Comics can be broadly accessible or bizarrely esoteric, highly commercial or defiantly iconoclastic, deeply emotional or brilliantly intellectual. Or any combination of the above and more.

Falling in love with comics means knowing that you will never be bored. You will be too busy for that. There will always be something new to discover… or to invent.

Comics is a collection of nested modular objects: letters within words within balloons within panels within tiers within pages within chapters within books within epic 20-volume shoujo manga series. Plus, of course, some characters and backgrounds. And that nested modularity lends itself to endless creative and scholarly pursuits.

Falling in love with comics means knowing that you will never be bored. You will be too busy for that. There will always be something new to discover… or to invent.

Jason Little BFA Comics Coordinator BFA Comics/BFA Illustration