Alison Bechdel is an alternative American cartoonist and prominent pioneer of underground queer comics. Bechdel began her career with her long-running personal comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For . Running from 1983 to 2008, DTWOF became a staple in gay, feminist, and alternative North American publications. She has since received critical and

commercial recognition for her awardwinning 2006 graphic memoir Fun Home , which was soon adapted as a Tony Awardwinning Broadway musical. Bechdel continues to create, having released her latest book, The Secret to Super Human Strength , in 2021. Through her lifelong work as a cartoonist, Bechdel has cemented her status as one of the most influential and beloved cartoonists in the current-day queer comics scene. .

Let’s jump right in; as someone with a liberal arts education—

Are you putting that in quotation marks?

Of course, “liberal arts” education. How did you make your way into comic tools and techniques?

Very haphazardly, stumbling along on my own. There weren’t any school programs. You couldn’t get an MFA in cartooning back in those days, or I totally would have signed up. Actually, when I first heard about the Center for Cartoon Studies here in Vermont, I was like, “That’s crazy! You don’t need to go to school to learn to be a cartoonist!” But you do. Especially now with the whole technological side of things. There is a lot to learn. But I just read comics that I liked. I copied things from them that seemed like good techniques, and slowly learned about equipment.

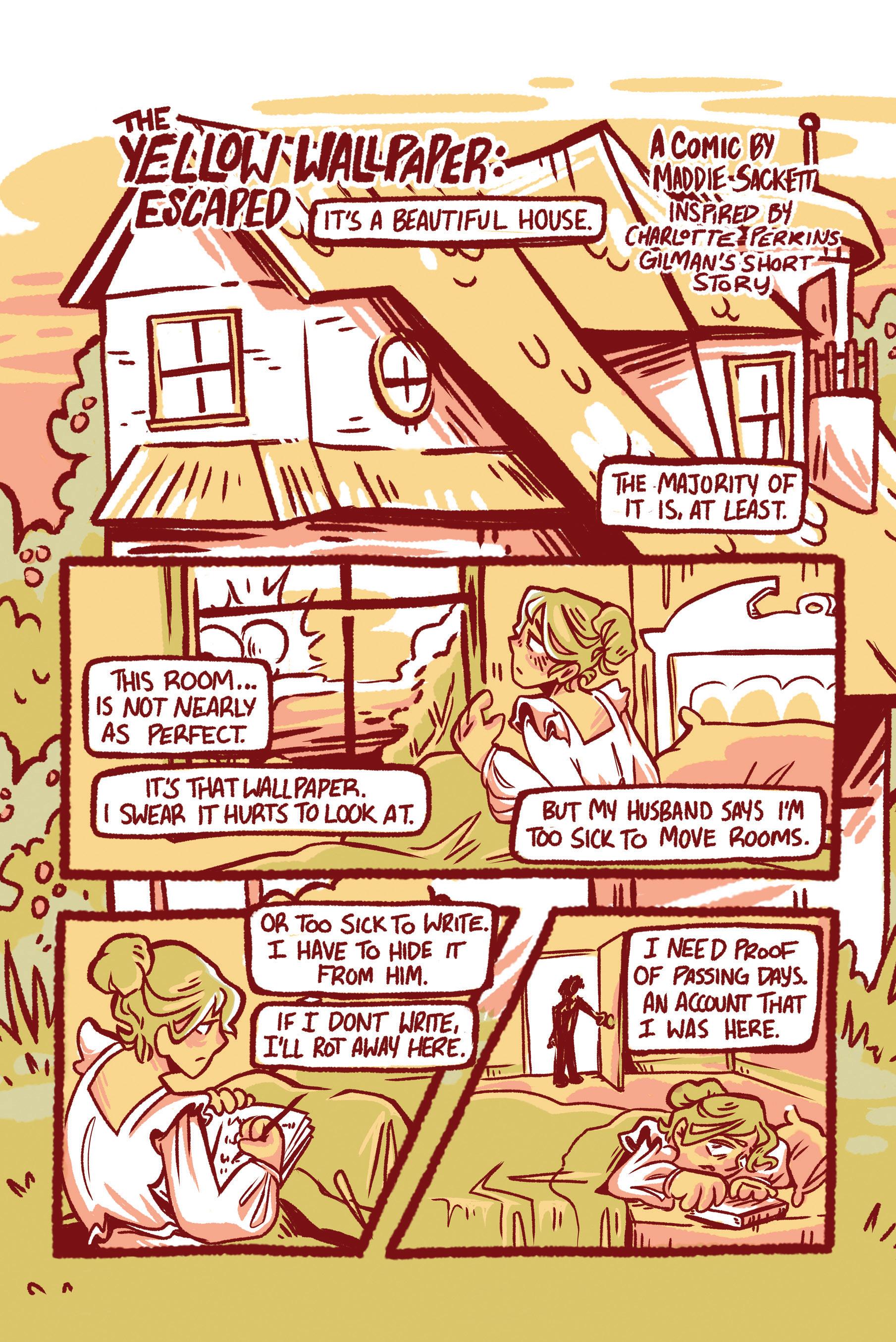

graphic narrative is that it very much matters where everything falls on the page. If you’re just writing prose, it doesn’t matter. The text just runs from left to right across the page and keeps going until you’re done. But if you’re writing a comic, you put certain things in certain places; you might want a page turn that will surprise the reader. You want to make use of a spread, if you can. Learning to bind a book was really very revelatory for me. The same teacher—Arthur Hillman, at Simon’s Rock—who taught me bookbinding was also my printmaking teacher. I’ve always just loved the idea of reproduction, you know. Which is another cool thing about comics; the point is to make a lot of them.

Is there an early body of comic work that predates Dykes to Watch Out For?

Were there any specific art or writing classes or teachers that shaped your creative practice?

I stumbled onto a fantastic class in my sophomore year of college, a book arts class. We learned to make a physical book, to write and illustrate it. And then, most importantly, most magically, learned how to bind a book. And I feel like I somehow learned so much about cartooning from that class just because of how you grappled with the physical page—learning how to fold a signature and stitch these things together. I mean, the magic of a

Well. I guess I consider all of my childhood artwork to be that body of work. I still have most of the stuff I made as a kid and a teenager. I feel like I can see my development very clearly evolving through all of that. In a way, I’ve always been a cartoonist. That’s just been my natural inclination, to make these kinds of funny drawings all my life. I feel like all of my work is just one continuous spectrum… it’s all the same project.

I’m assuming that Dykes to Watch Out For was a hit because of support from gay and lesbian print publications. Can you talk a little bit more about the underground queer press, preinternet?

My comic strip actually sort of coevolved with that network of publishing outlets. Just at the time I began writing the comic strip, gay and lesbian newspapers were starting to be formed in most big cities around the country. So there was this venue where it was possible to start publishing. It took me a while to figure that out. I began publishing just for free, in a feminist newspaper in New York City, just for fun. There was no infrastructure that in a million years could have paid me at that point, of course.. But gradually, these other newspapers that were more of a business—getting local real estate ads, or local nightclubs and bars to pay for ads; those papers paid my bills for a long time. I self-syndicated the strip to these emerging newspapers all over, and I was able to eventually cobble together an income from that.

How has that landscape changed since you got your foot in the door?

It’s been completely obliterated. Gone?

There are big LGBTQ newspapers here and there. But the internet just changed everything. General cultural attitudes shifted enough that we didn’t feel so marginalized and didn’t have to create our own newspapers. Gay people were represented and seen more in the culture at large. So, yeah, that world doesn’t...Well, I don’t mean to say it doesn’t exist at all . There’s still a pretty thriving queer comics scene.

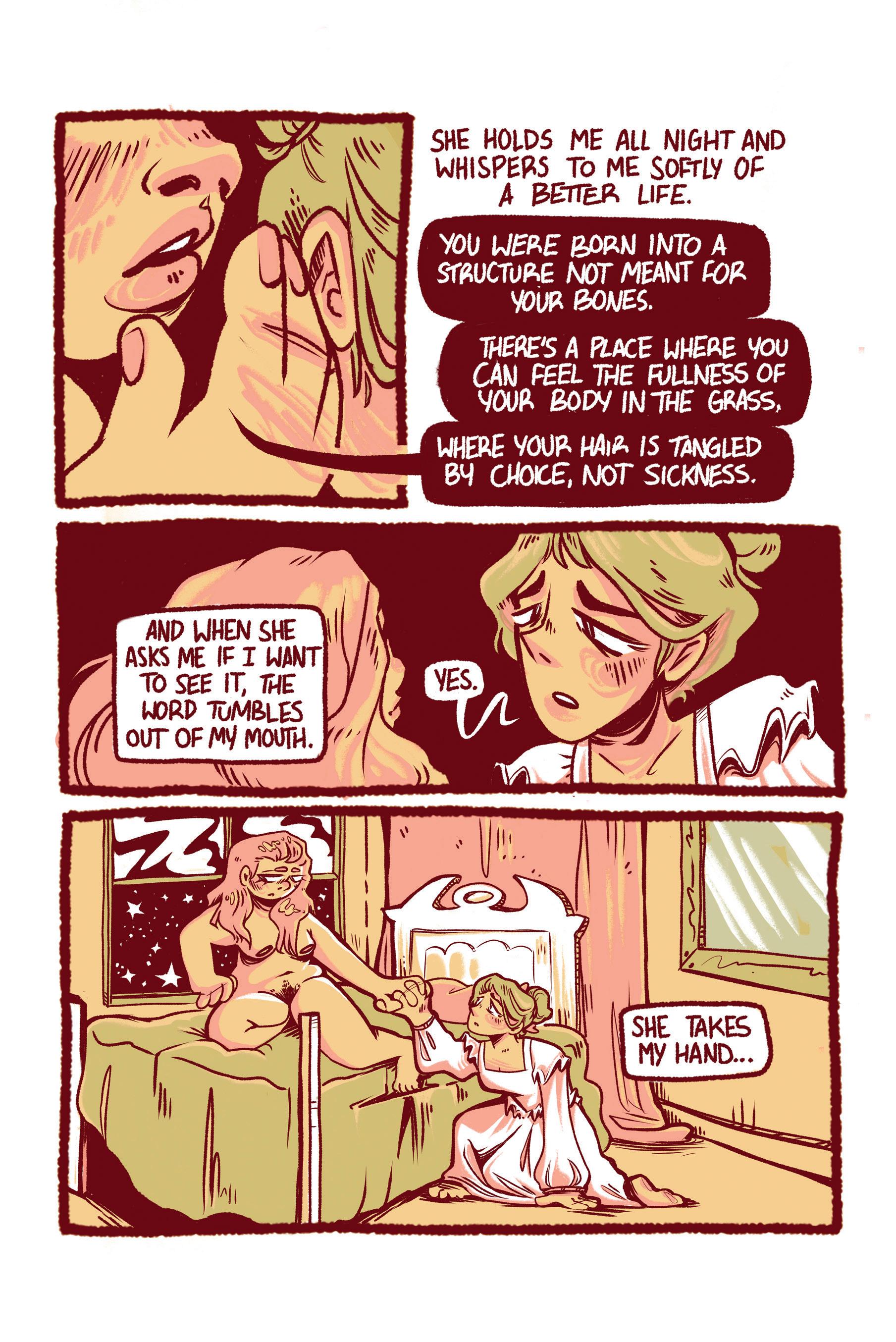

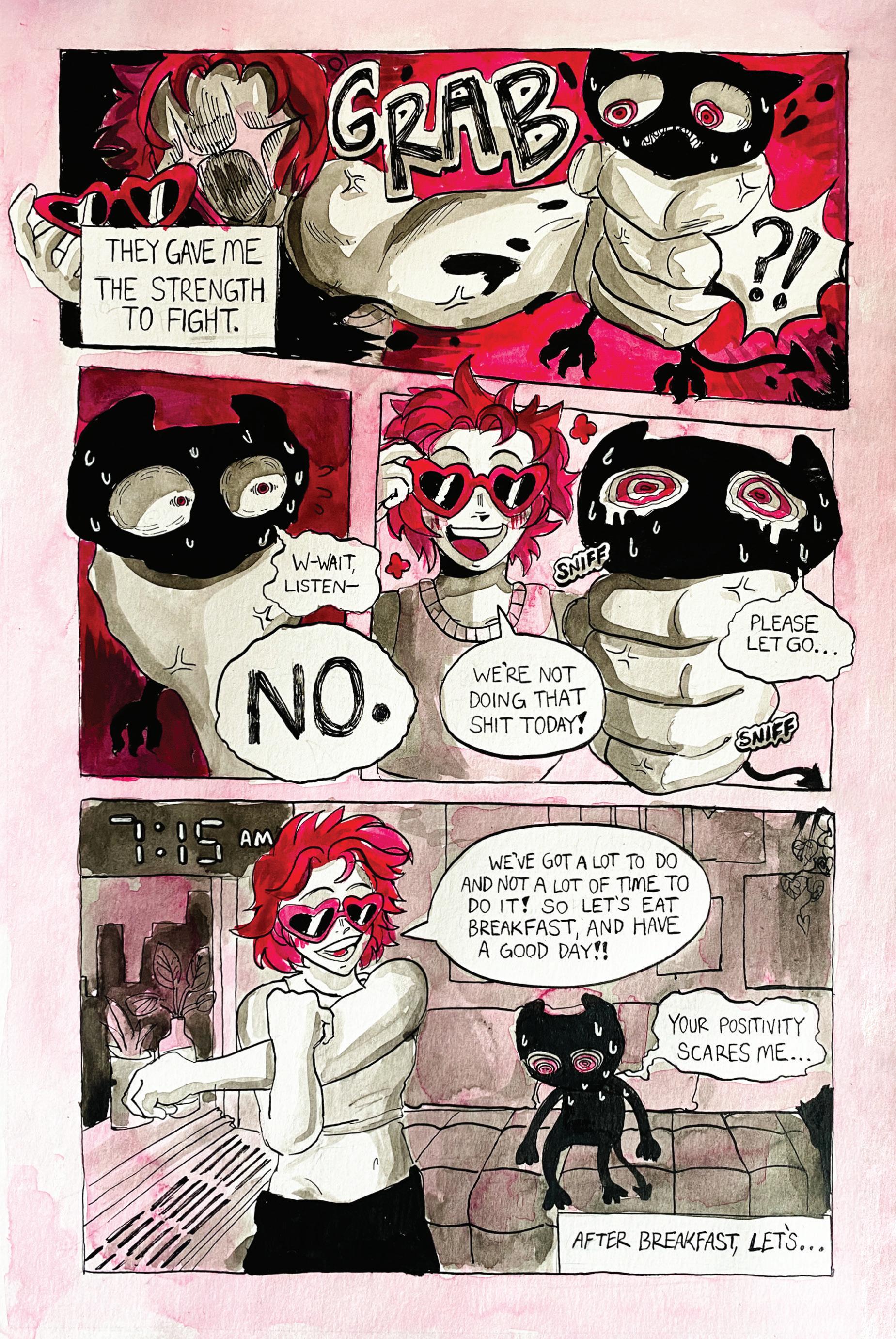

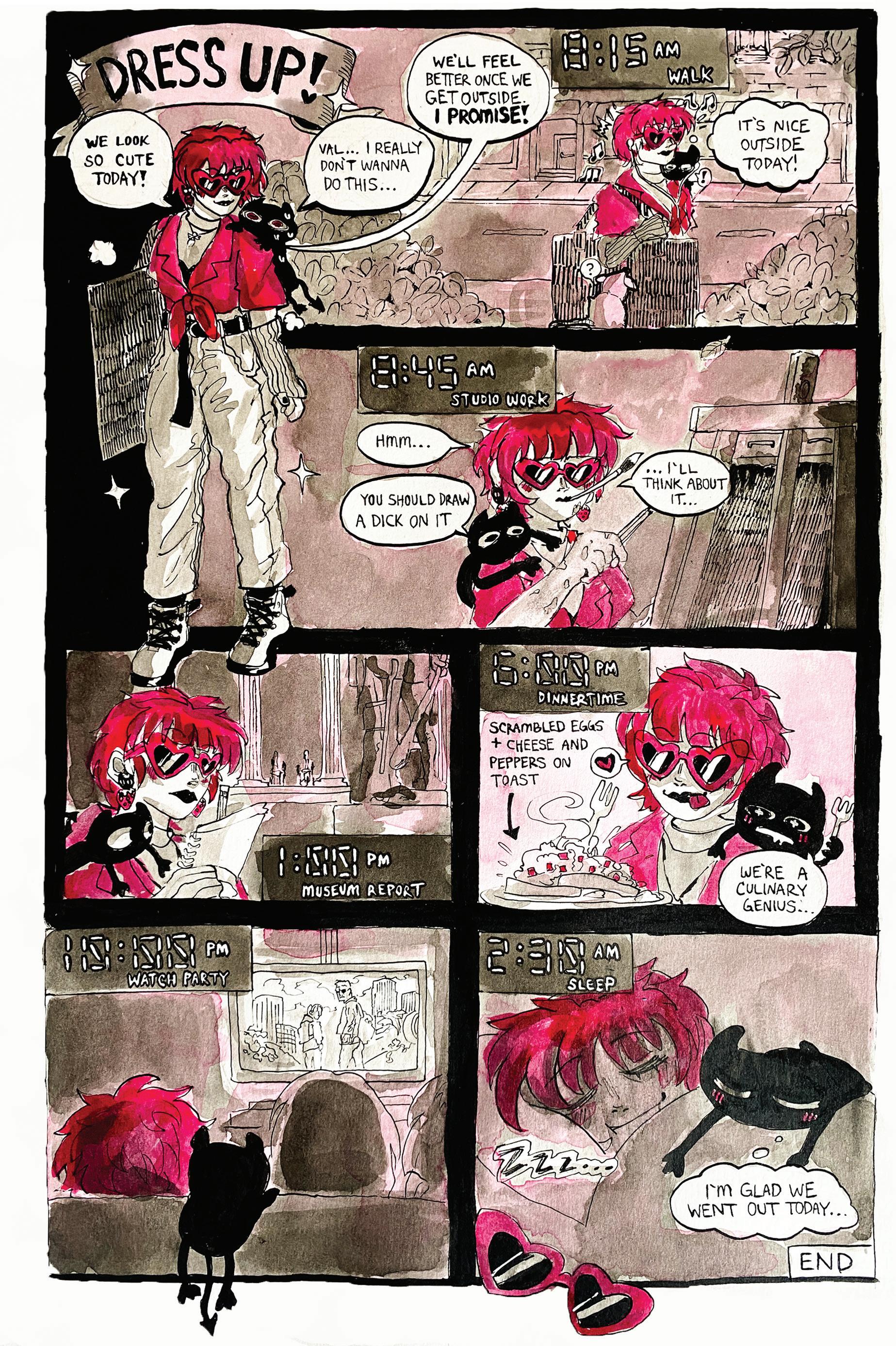

comics, from Dykes to Watch Out For to The Secret to Superhuman Strength , there seems to be this evident loosening up in that regard. How do you think your process has changed over time?

“That’s crazy! You don’t need to go to school to learn to be a cartoonist!”— but you do. Especially now.”

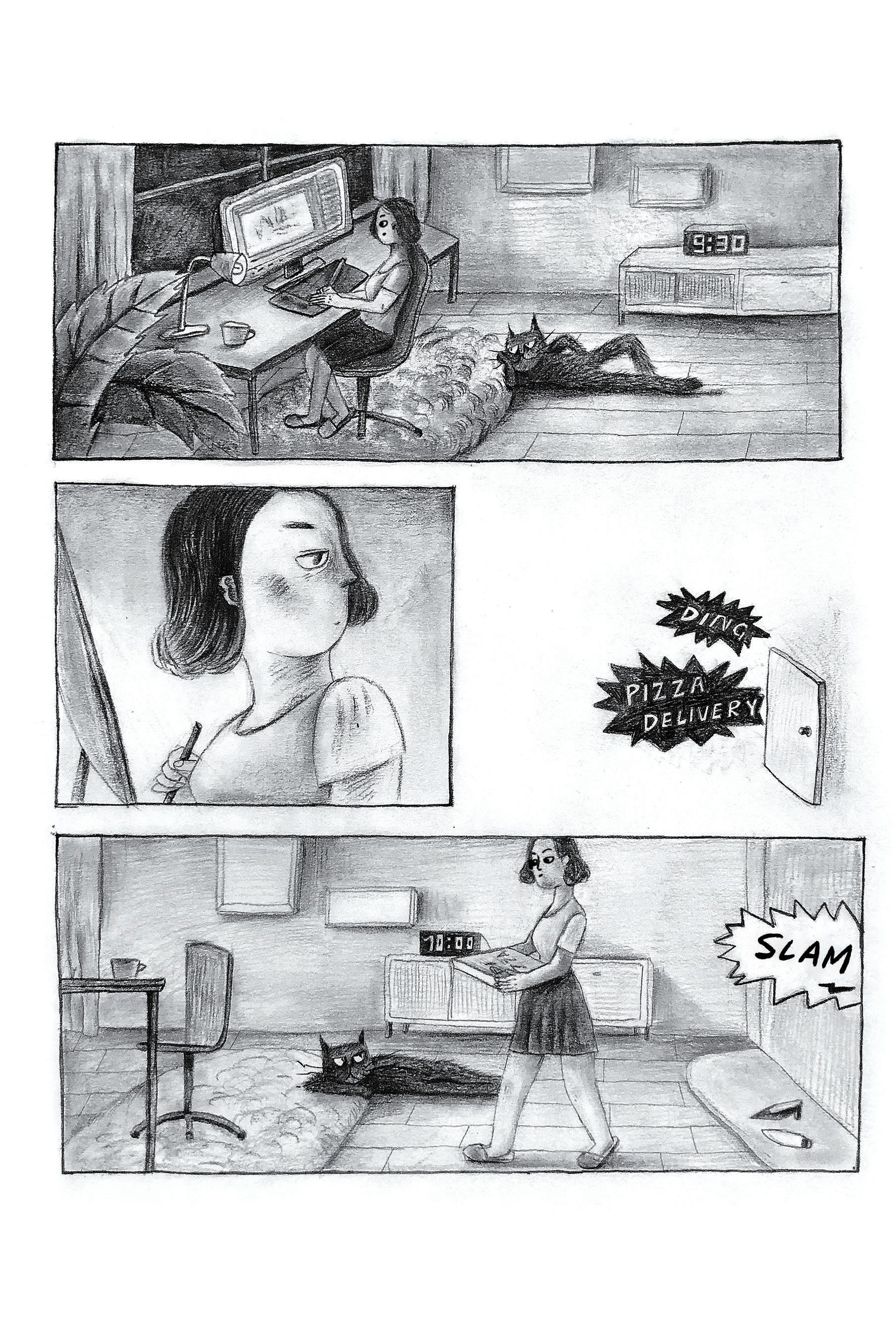

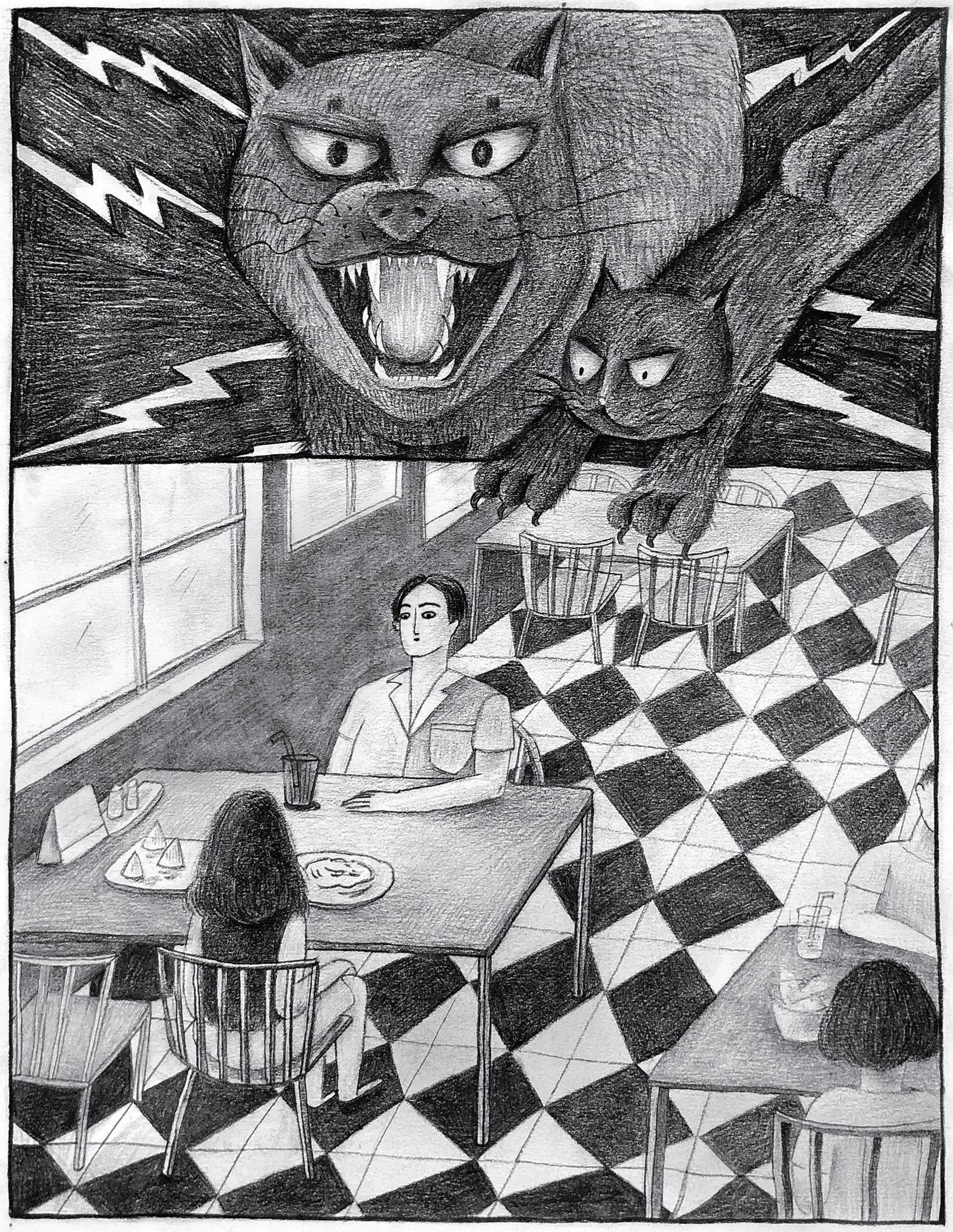

Something that I’ve always seen as very definitive of your work is detailed and structured inks. Through your

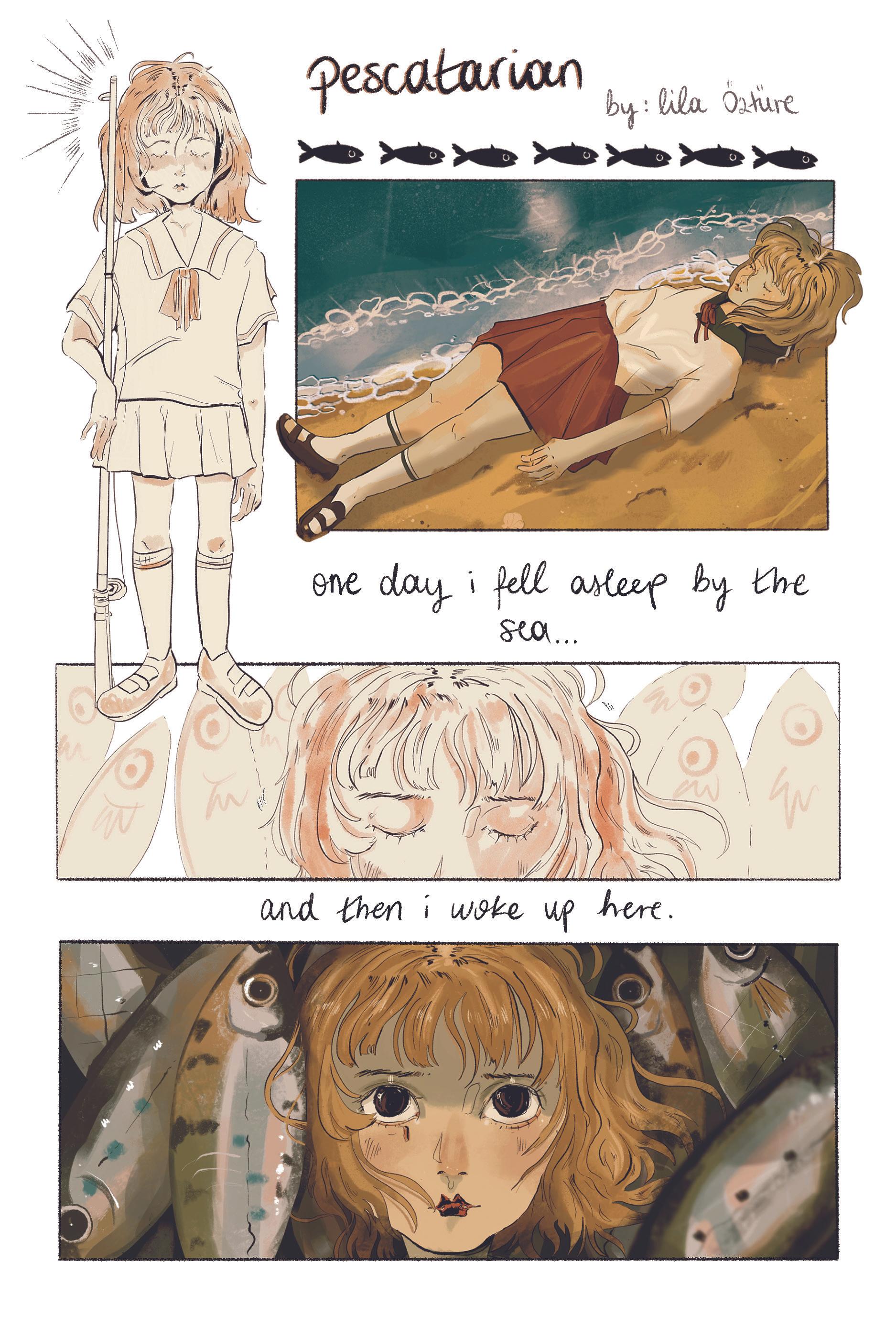

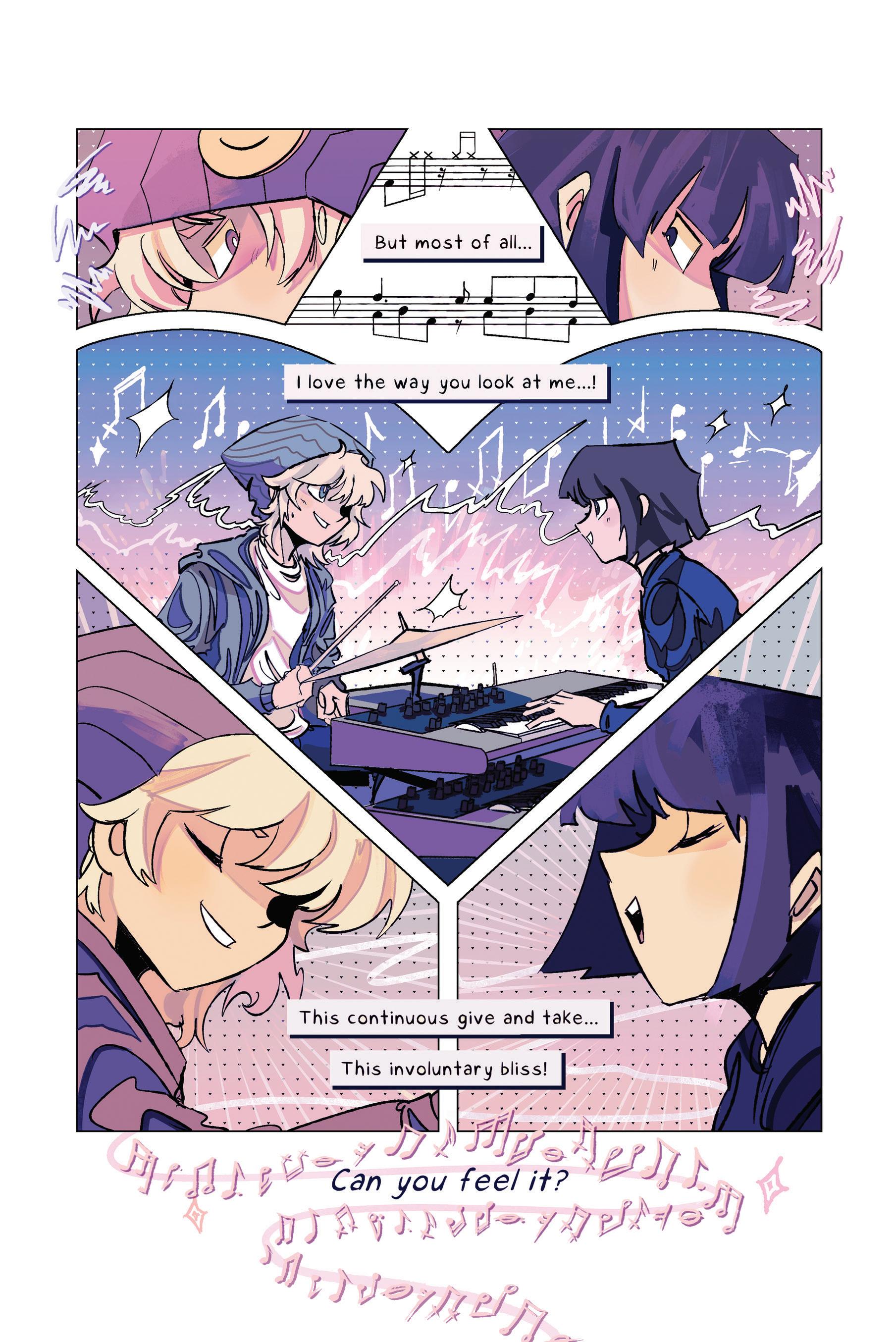

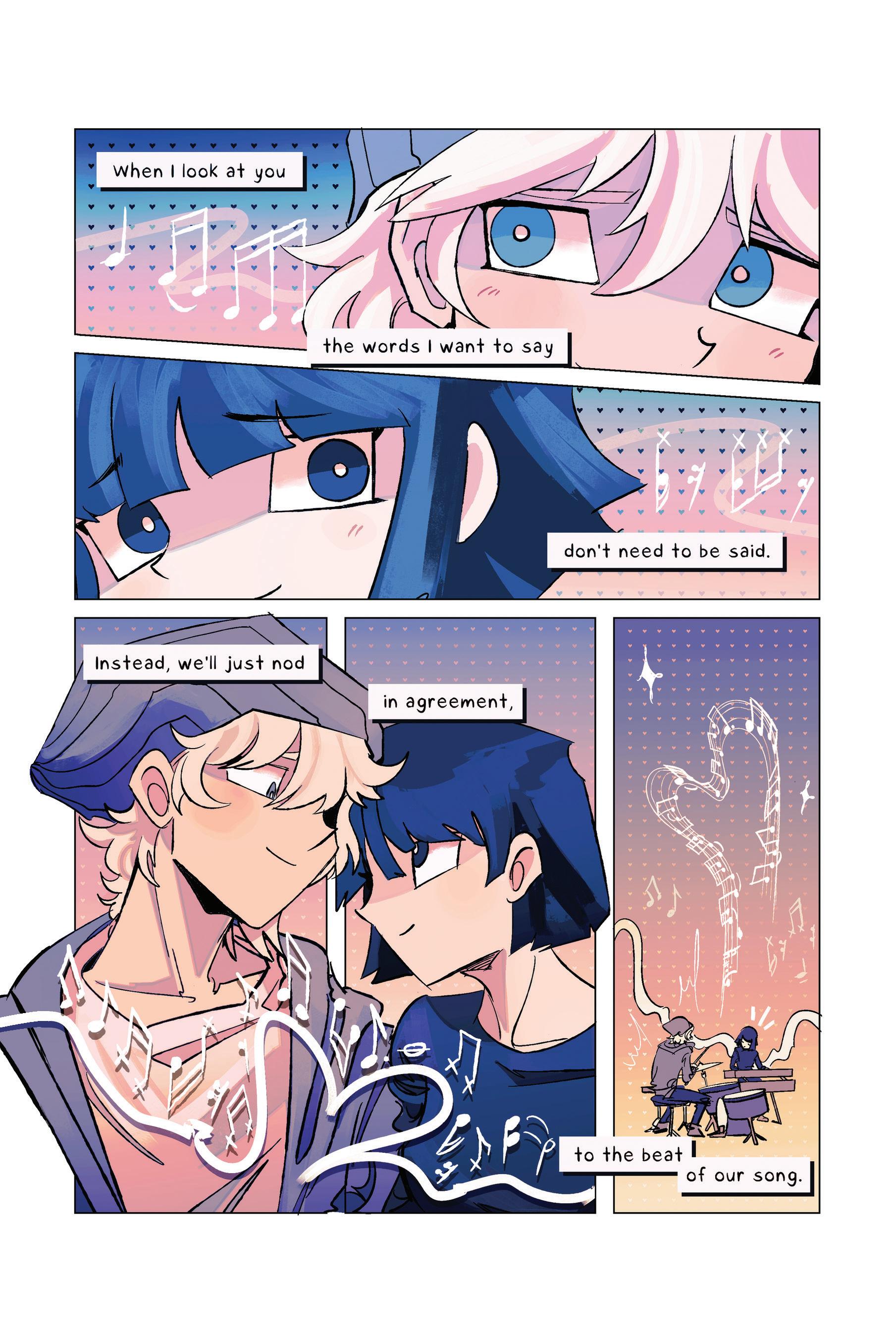

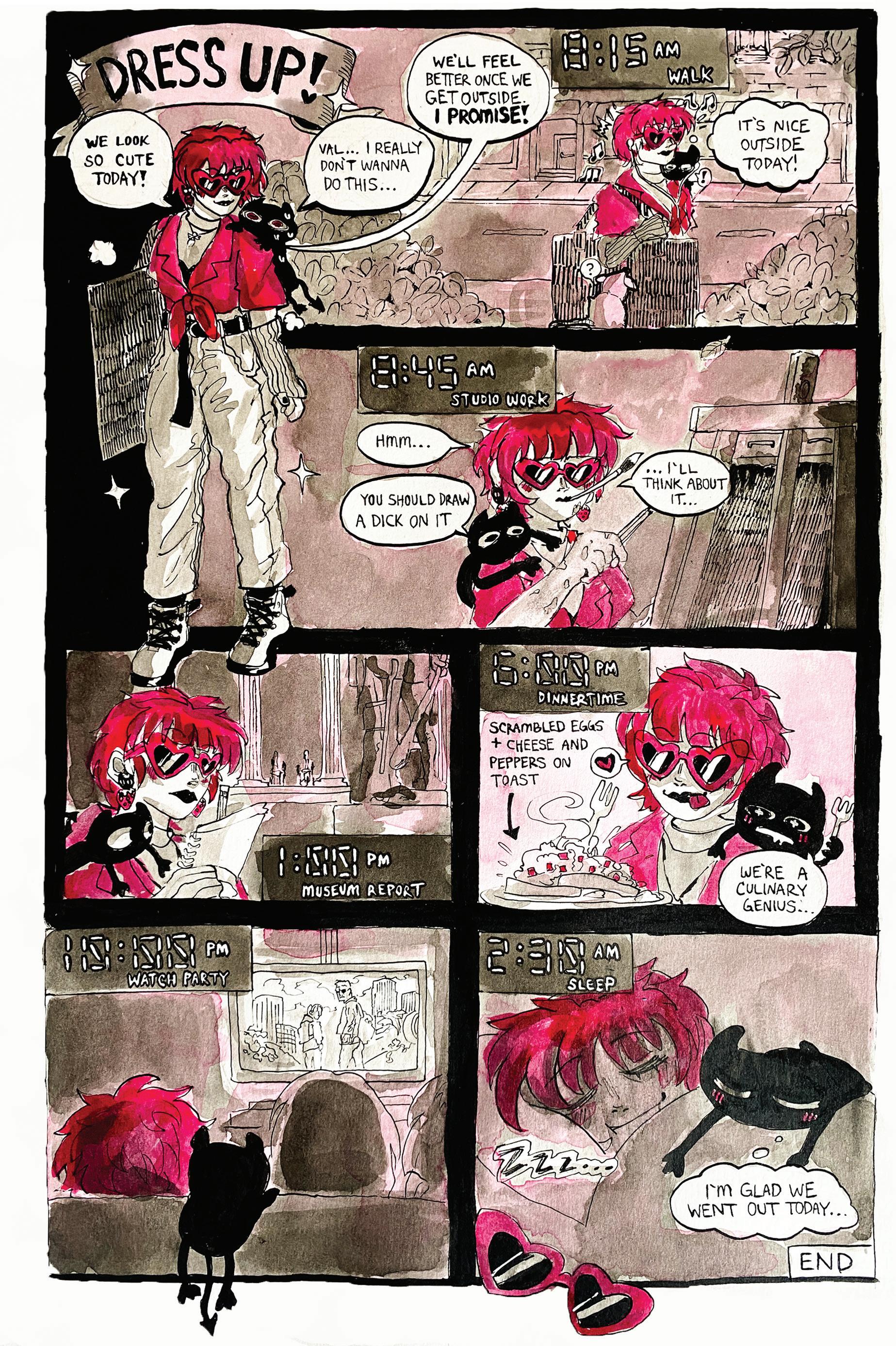

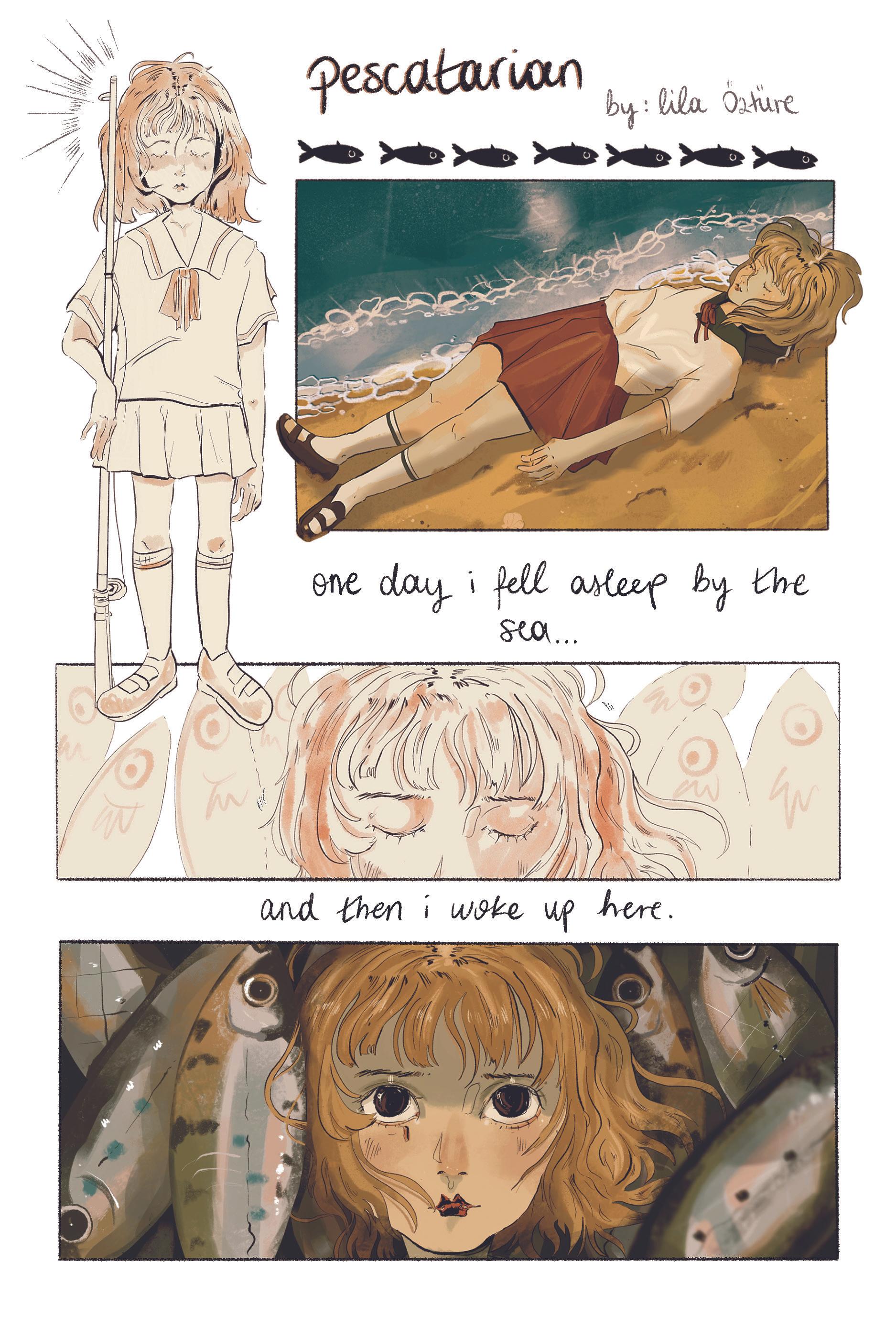

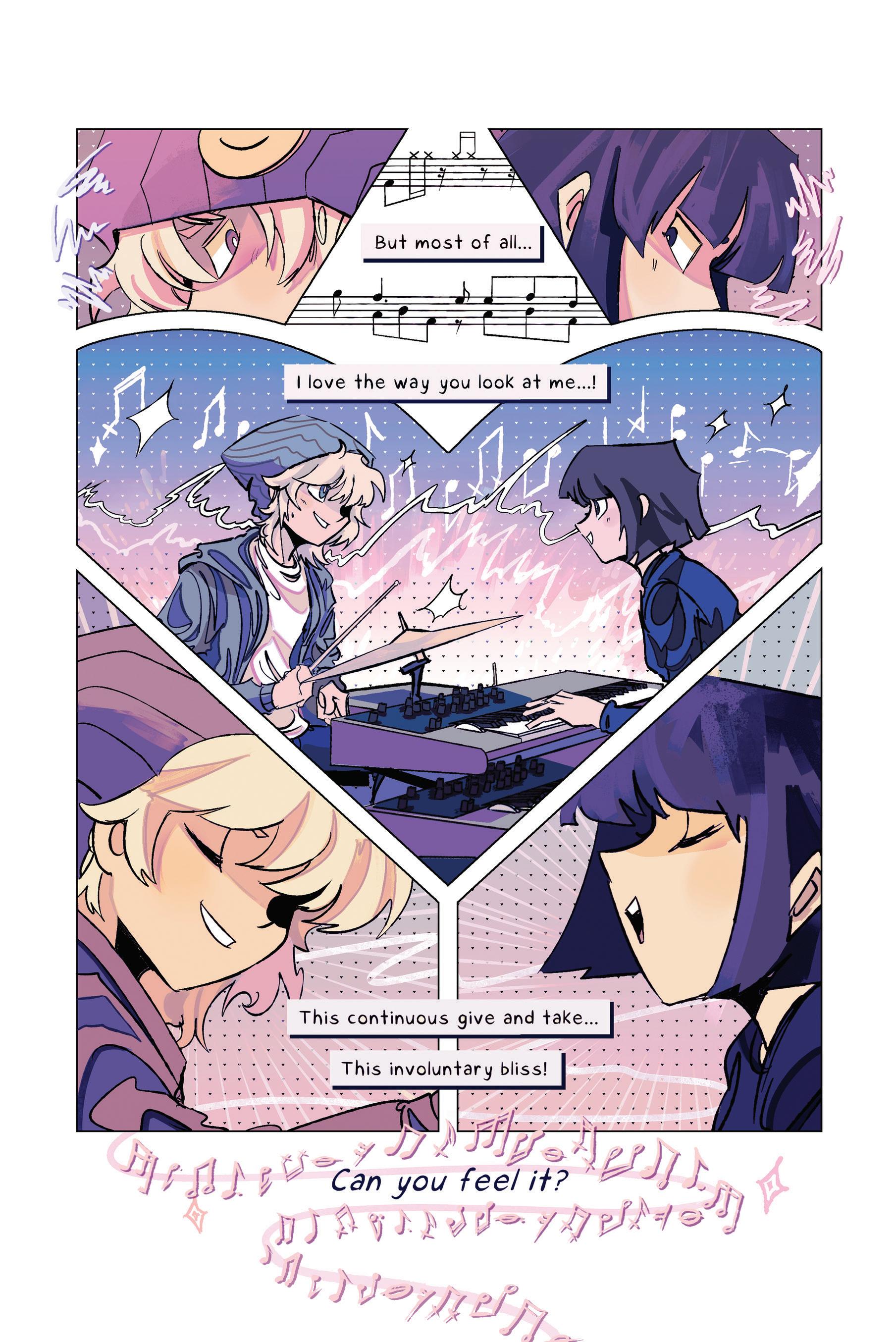

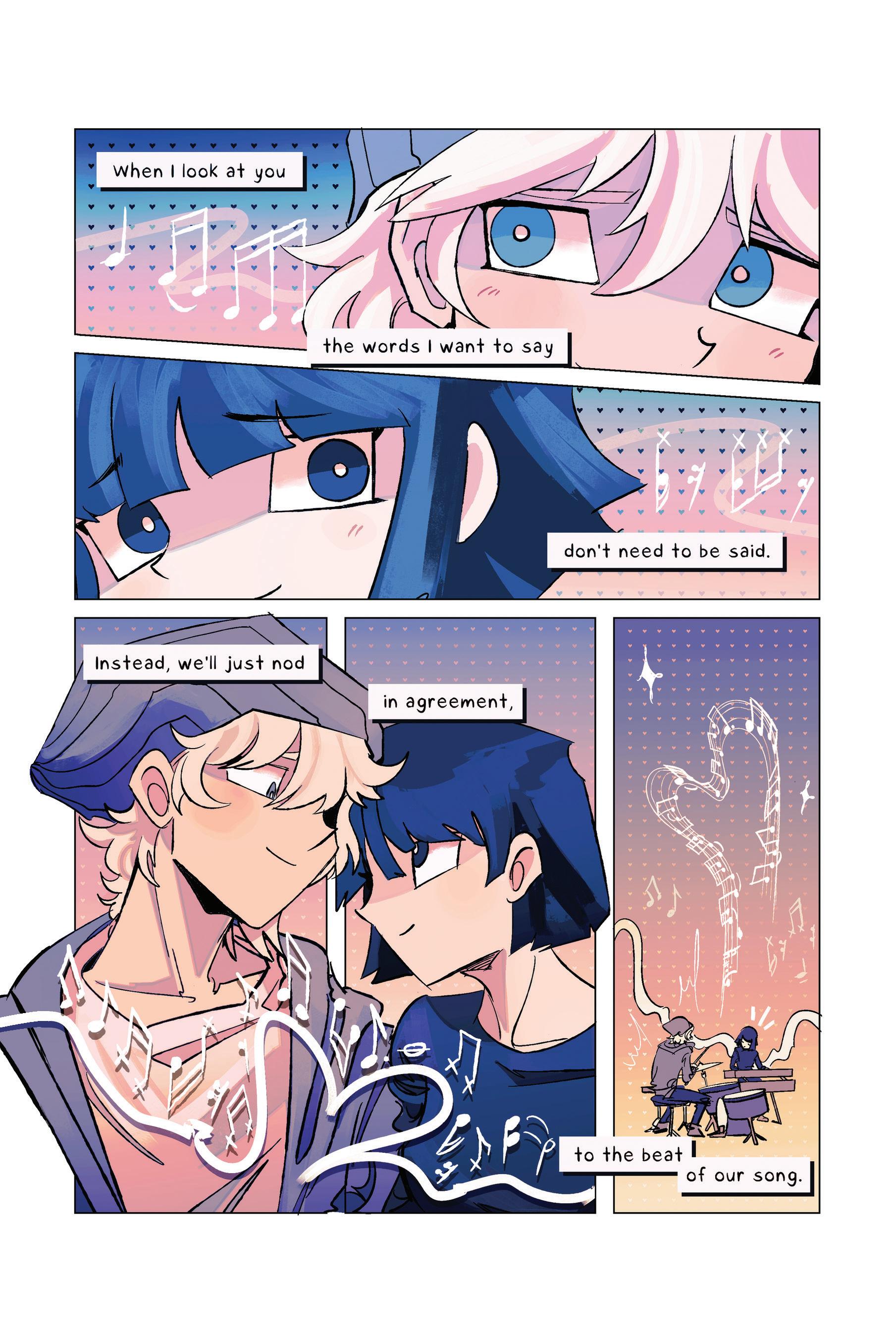

Oh, man, I mean, I’m still learning how to be a cartoonist. Like I’m just looking at this page from your work—this is so sophisticated, this incredibly complex page structure. I didn’t know how to do that back then! I still don’t know how to do that. I just wrote a comic strip, where everything had to fit in a certain space in the newspaper. I never played around with form at all because there was no room to do it. When I did graduate from the strip to making books, I still stuck to a six-panel grid. No one taught me how to make more complex pages. But I’ve figured it out a little bit over time. I’m still not very good at it. That’s really my great weakness as a cartoonist, is that I

don’t use the page terribly well. Let alone the page spread. That’s even more of a challenge.

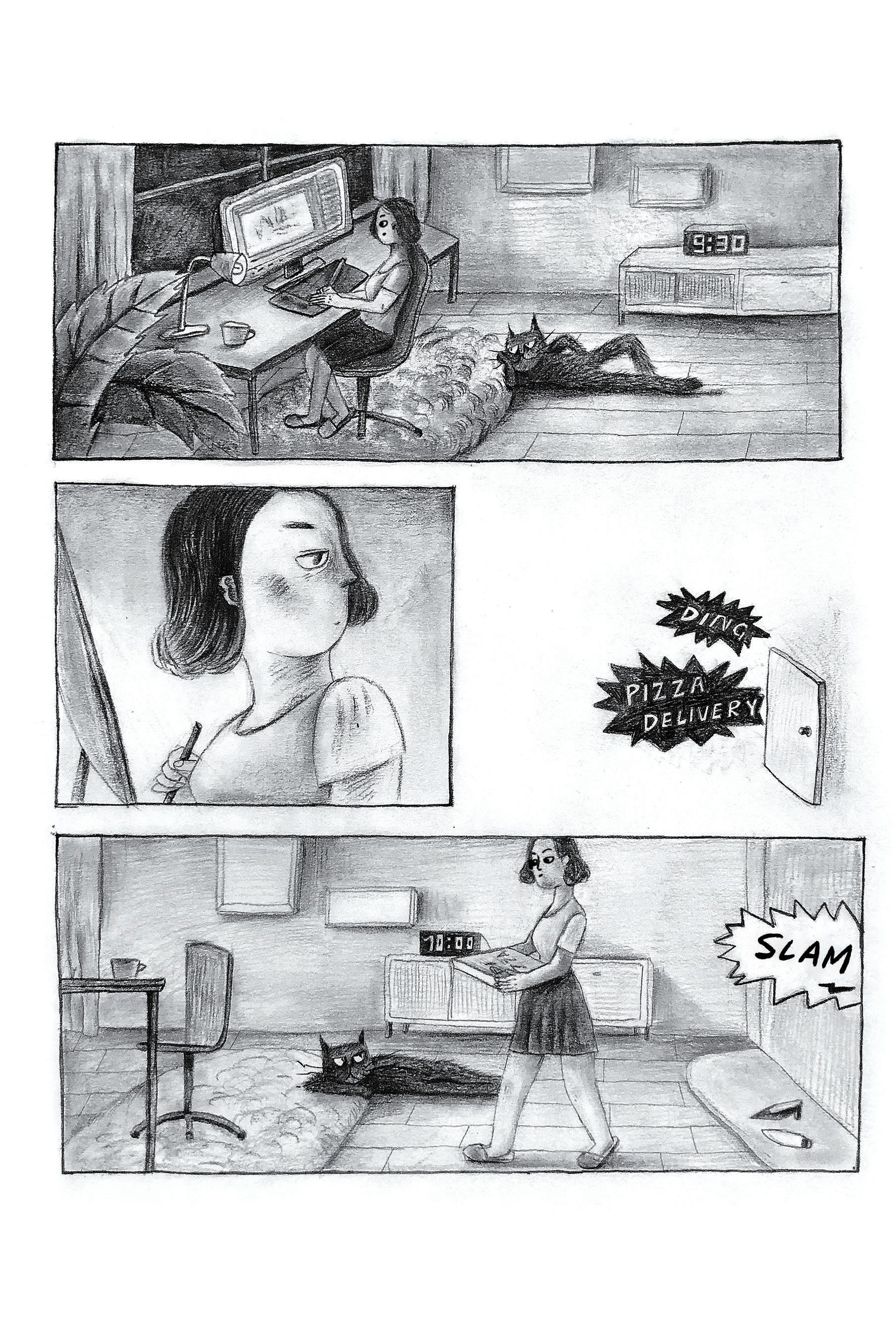

On a similar note, the jump from monochrome in some of your earlier works to color in The Secret to Superhuman Strength is, I saw that as a similar jump. I understand you used a handseparated color process. What was that like? Is there a reason you went with that specific process?

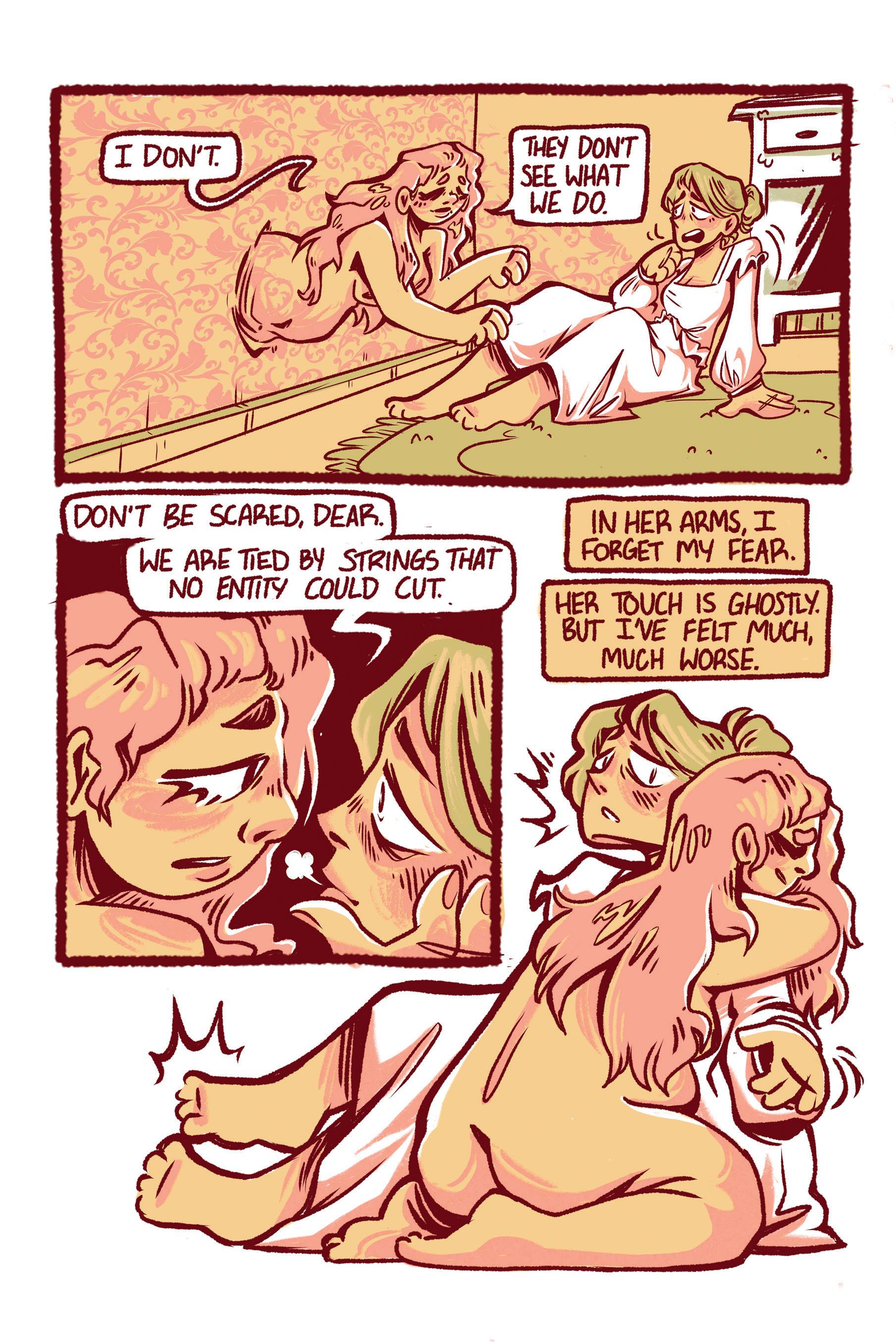

came up with this system which I thought would maintain some kind of consistency. Which ended up being incredibly arduous and complex for Holly, because she was essentially creating color separations for each page. What I would do was, I would give Holly a color sketch showing her what I wanted the page to look like. We’d sit down, and I’d do a very rough colored pencil thing. And she would make notations that she understood. Instead of just using color media like a normal person would do, she was painting everything in different gradations of ink wash, putting watercolor paper on a lightbox, and filling in areas with this gray ink.

Then what she’d end up with is: the cyan layer, the magenta layer, and the yellow layer. And a few more, actually, which was all incredibly difficult to keep track of. If she wanted to make something green, she had to make sure it showed up on two different layers. I did my own cyan layer of shading on each page, to kind of give it my own hand. And then we would scan all those layers into Photoshop, and tint them the corresponding colors. Then we’d combine them with the lineart. But it was completely unnecessary. We could have just done this with one layer of watercolor.

“

I think that’s also a really important corrective to your own version of reality in which you are the hero. Everyone else has their version, and they’re the hero.”

Okay, the coloring process for this book was totally crazy. First, it became clear that I was not going to have time to do it myself. So my partner Holly, who’s a painter, agreed to take it on. But because I’m a control freak, instead of having her just do the color with watercolors —we both knew we didn’t want digital color—I

I can’t imagine doing it all in gray and envisioning the color in your head!

I know! And, there are so many mistakes, because you couldn’t see them as you were working. And by the time we were done, it was too late to go back and fix them. It was incredibly complex to go back and fix them. It was just insane.

Do you have a recommendation for someone who’d want to get a similar effect without the pain?

Just use watercolor! Or gouache or something. I mean, printing technology is just so different from when I started out. You can do that now. I think I just retained some kind of Stockholm syndrome from the olden times. You can just do watercolor and it will come out beautifully.

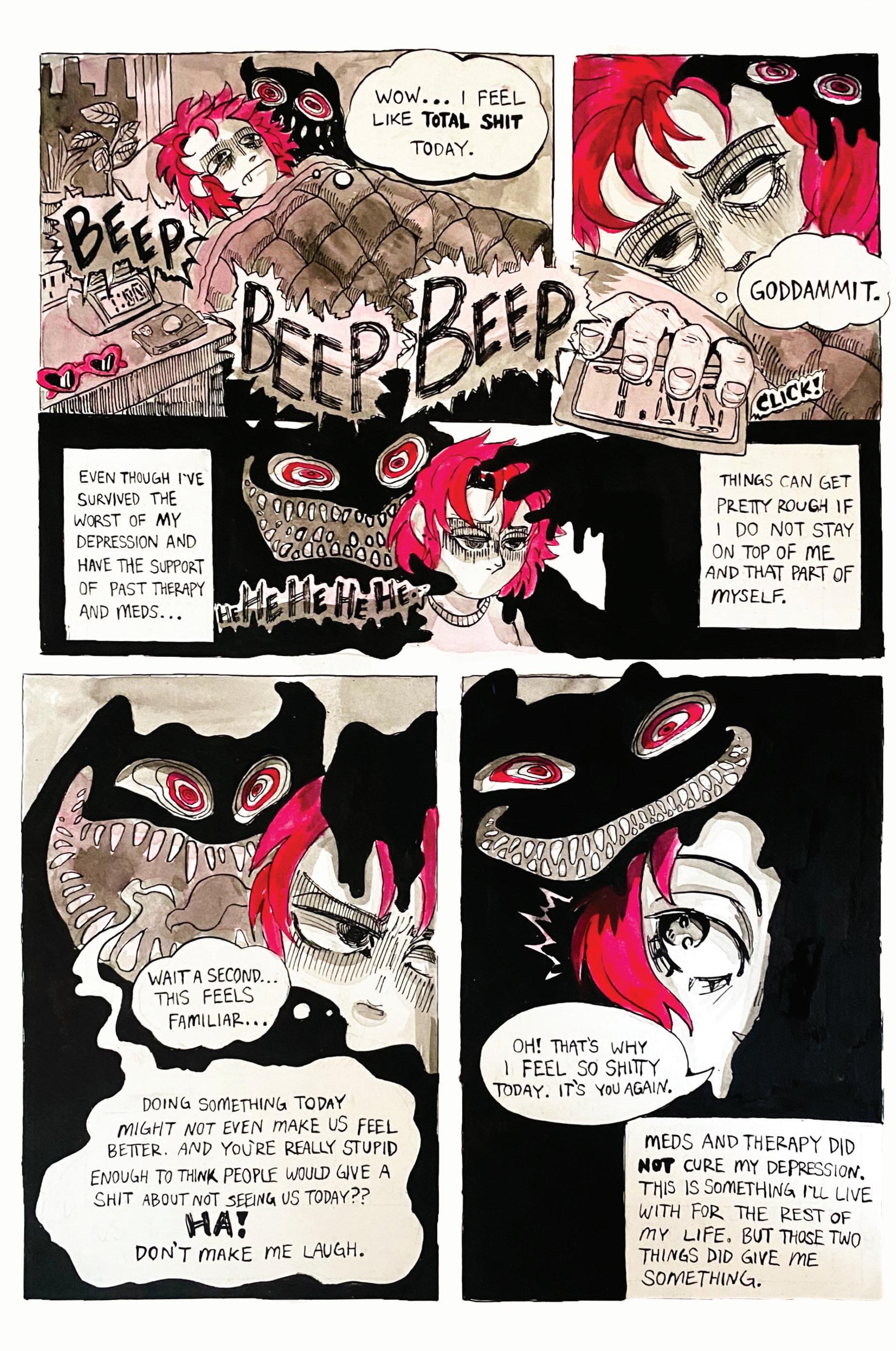

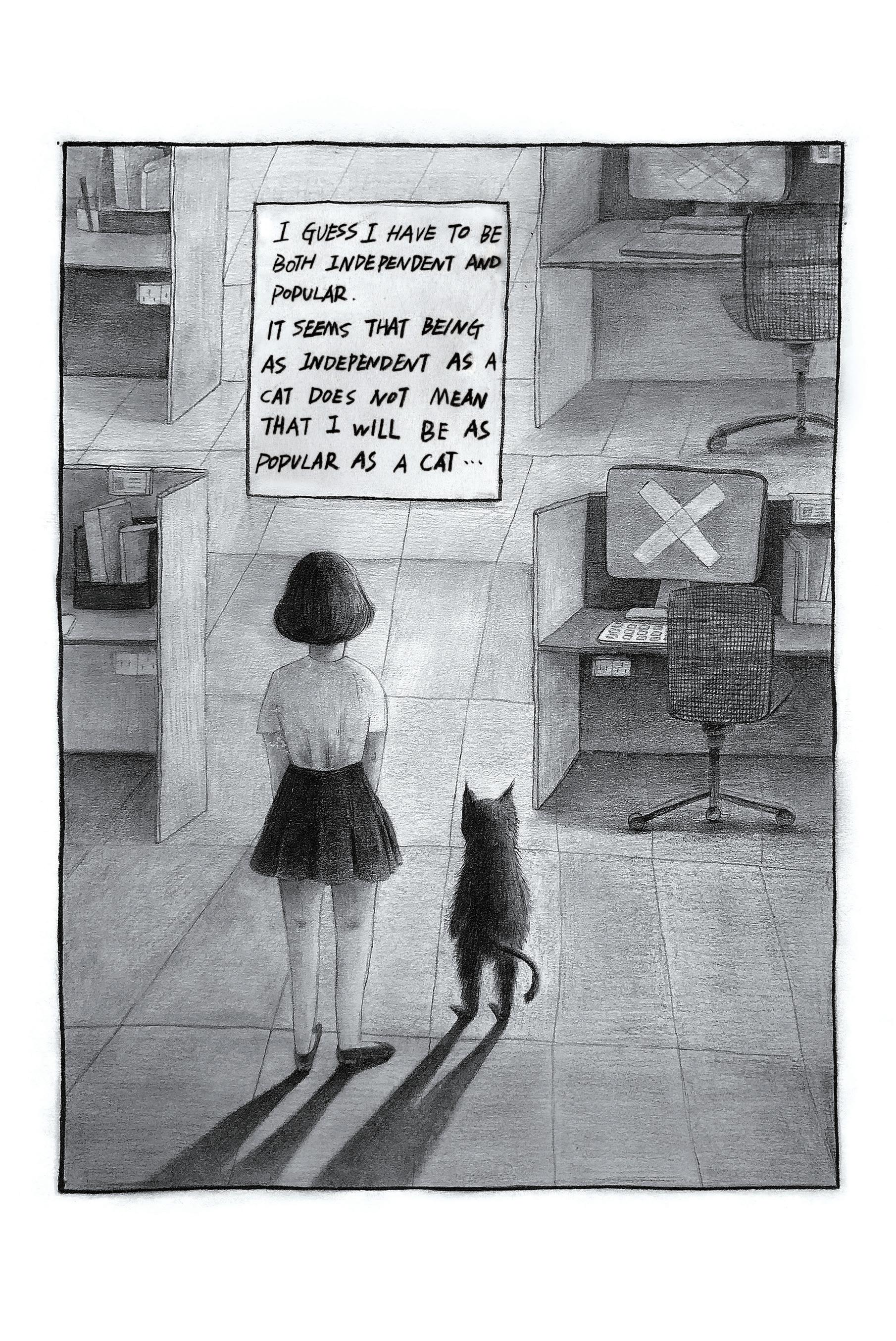

Moving on, a problem that often comes up in creating nonfiction, especially auto-bio work is, “when am I divulging too much?” like, the struggle of what personal information is integral to the story, and what could be extra weight. How do you sort through the slush of life experience to determine what’s necessary to develop a complete compelling story?

That’s the big question, isn’t it? I mean, that’s what writing autobiographically is always grappling with. I’m someone who keeps a lot of records, I keep a journal, I have all my photographs, I keep old correspondence. Sometimes I think I would be better at what I do if I didn’t have all that stuff as source material, because you can just get lost in it. And often, that’s my process. I just kind of get mired in some past episode of my history, and struggle to climb back out again. I want to tell everyone everything; I want to share every little tiny detail of my entire life. But you can’t do that, or your story will just be impenetrable. No one’s going to ever want to read it. So the trick is, what is really significant? In all of these things that have happened

to you, what matters, and what should you, ethically, perhaps keep to yourself, to protect other people?That’s the whole process. When it gets to something that I know is intruding on someone else’s personal story, I try to get their opinion. I try to show stuff to them and let them know what I’m doing. And that’s an uncomfortable process, because inevitably, they see things very differently than the way I did. But I think that’s also a really important corrective to your own version of reality in which you are the hero. Everyone else has their version, and they’re the hero.

One of my favorite aspects of your nonfiction work is the multiple personal or cultural tie-ins. Going back to Are You

My Mother , your work connects with Virginia Woolf, Donald Winnicott, the psychoanalytic study, and then eventually brings in work from Adrienne Rich. How do you decide what these companion narratives will be?

You know, I stumbled onto that technique when I was writing Fun Home . All the books that my father loved that I worked into the story were absolutely not part of my first vision for the book. At a certain point I realized, man! I don’t even remember my father. How can I, like, get back in touch with him, and who he was? And so I decided, okay, I’m gonna read some of his favorite books. And that became a device. But it really did something to the story, to

the writing, and added this whole other dimension that I hadn’t anticipated, and really loved when I saw what it could do. I could make this story not just my story. So I just kept trying to do that technique in all of my subsequent work. It wasn’t like, okay, who am I going to write about for this book? It just kind of organically happened. Like, I became very interested in psychoanalysis at a certain point in my life. And after reading a number of these books, that material started creeping into my new work, into the book I was writing about my mother. And so, oh, okay! This is also going to shape this book, this other material that I’m reading. These ideas of Donald Winnicott can be like a way to structure the whole narrative… and then I did it again in my newest book, in Superhuman Strength . I don’t know how I picked those people. I think I started with Jack Kerouac, just because I’ve always really loved his book, The Dharma Bums There was some feeling in there that I loved and wanted to get into my book…then that led to these other kinds of related thinkers and writers who I see as part of a similar lineage.

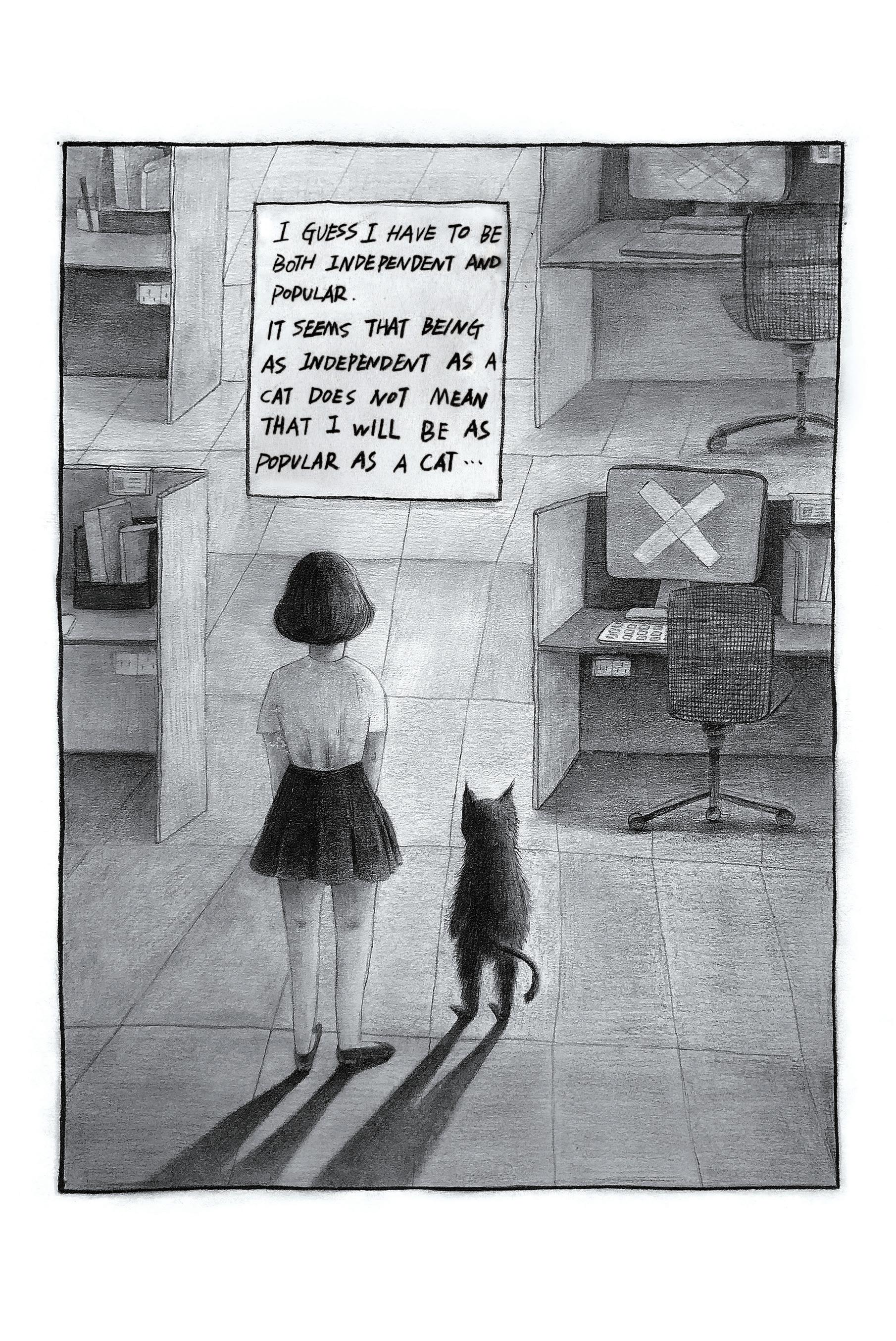

I always very consciously envisioned each of those characters as being some aspect of myself, so I would have access to who they were and what their motivations were, what their quirks were. You know, sometimes people will say, “Do you know those people? Are they your friends?” And I’m like, “No, are you crazy? Who would write a comic strip about their friends?” First of all, life is not that tidy. And who would let you do that? They’re made up! It was all very deliberately built around me. In a way, it’s a kind of autobiographical writing. I don’t know how to write about something that’s not me . In that way, it keeps everything grounded and very true to life.

Yes. Because then it’s harder to lie. It’s hard to be a good liar. So it’s better to try and tell the truth as much as you can. So I guess that in a way, that’s what I was doing.

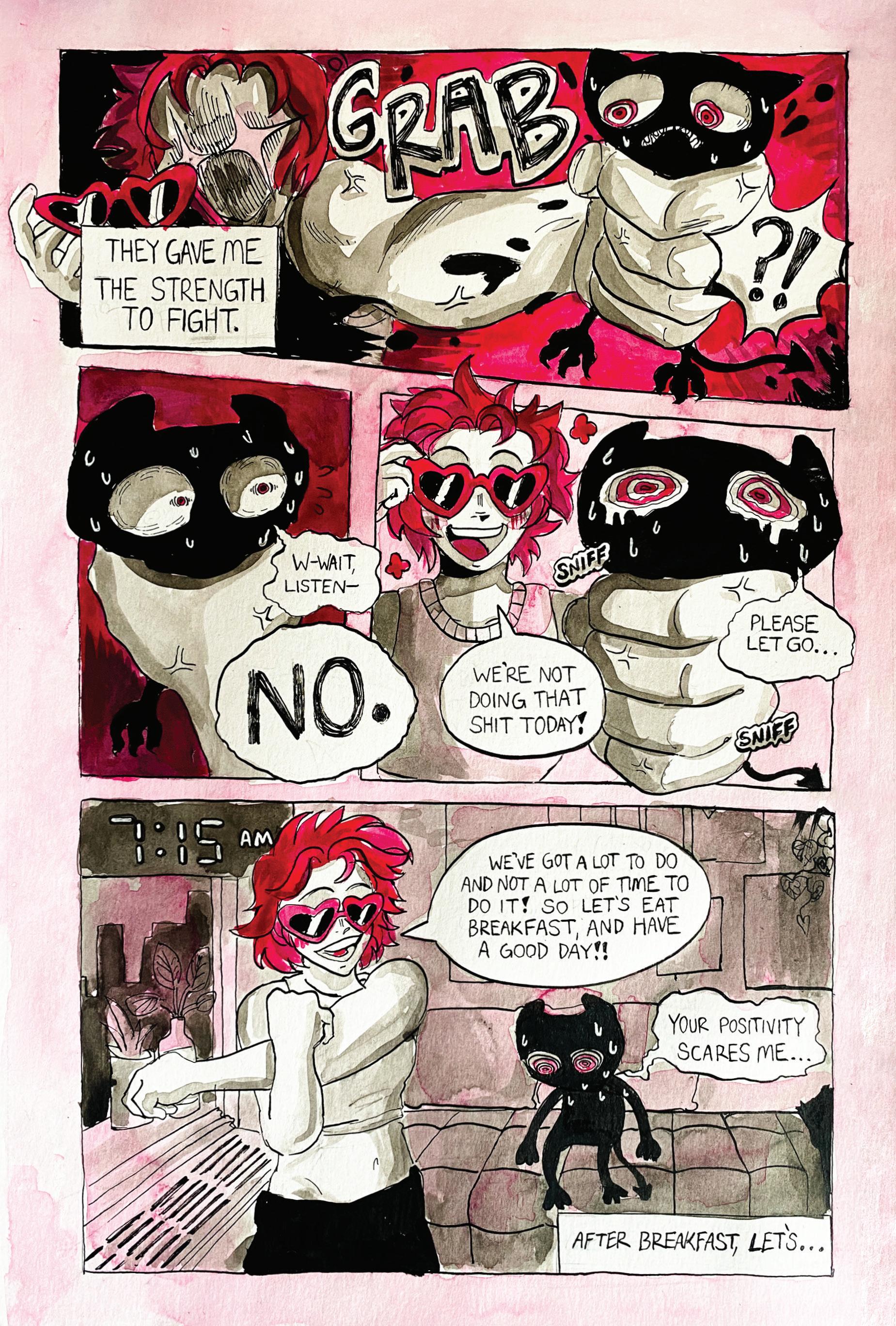

What advice do you have for students looking to pursue cartooning, professionally?

Obviously, there’s some aspect of yourself in one or more of your characters in Dykes to Watch Out For . How much does it reference you, your experience, or other experiences? How do you create that sort of realistic group?

Oh, I always hate this question. I mean, I would just say draw; you have to draw all the time. Try to keep learning. Try to copy the stuff that other people are doing that you like and make it your own. Keep a notebook, keep a sketchbook. But I don’t often take other people’s advice. So I feel a little sheepish, doling it out.

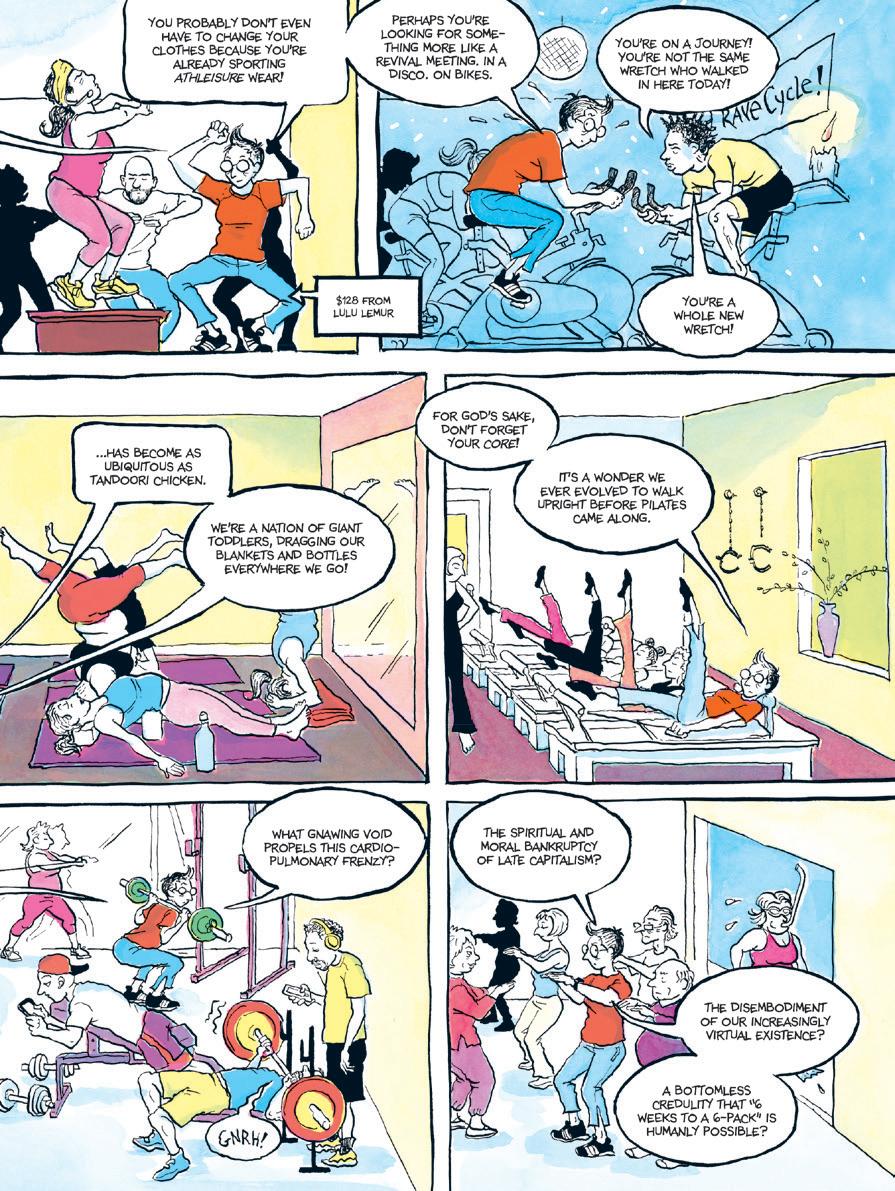

Do you feel the generation gap, In terms of what it means to be a cartoonist now and what it meant when you were starting out?

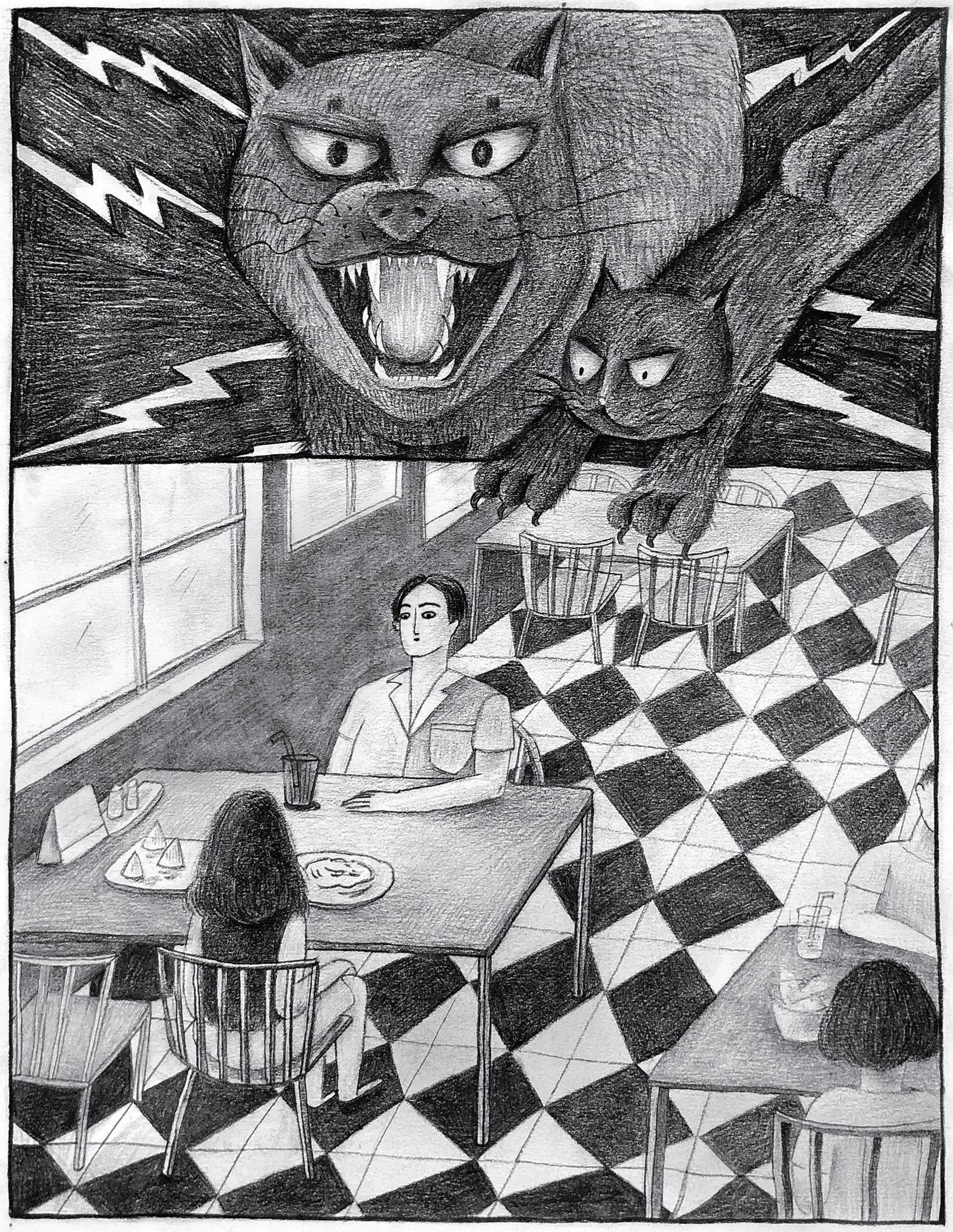

If I were a young person now, having to break into the world of comics, I would be paralyzed with anxiety. When I was starting out, it was just this thing for nerds. It was this place where no one was really watching you. There wasn’t a lot of criticism or critique. And that’s why I was drawn to it. Oddly, my parents were really great about encouraging me to, you know, be artistic and creative. But they liked fine art, they liked literary writing, and I didn’t want to compete in those areas. I felt I didn’t have the skills for that. But here’s the thing I can do. I can draw, I can sort of write—I can make comics. That’s still true, but it’s just much more competitive. Now your work gets critiqued and scrutinized, it gets taken seriously as literature if it’s good enough, and that was not the case back in when I was starting out.

Do you have any really notable artistic visual influences?

I’ve always loved R. Crumb’s drawings, and I’ve just tried to copy him in so many ways. But of course, you know, just failing spectacularly. I think he’s my, like, big role model. He has that super organic line. I’m always striving to be that accurate, but also cartoony, you know. He has the perfect balance.

Is there a way that you keep your process interesting, after working for so long?

I don’t have that problem. It’s not like I’m always doing the same thing over and over. I’m always doing some kind of new project or going in a new direction. I like learning new stuff. I was very excited about all the technological possibilities of going digital

when that happened, and I really went all in. And even now, I compose in InDesign, and I spend a lot of time taking reference photographs and scanning my drawings and just getting lost in the computer stuff. Like, I went a bit too far down that rabbit hole. And now I’m trying to come out. But just trying to learn new stuff keeps it all interesting.

The average person familiar with you and your work would consider you a successful cartoonist. But what does success mean to you? And how may the meaning have changed, the longer you’ve worked in the field?

I guess the main thing success means to me is reaching a point where you get to keep doing this work. And I—even as late as the early 2000s—when Dykes to Watch Out For was supposedly this very successful comic strip, and I was working on Fun Home but hadn’t published it, things had gotten so bad in the publishing landscape that I didn’t know if I was going to be able to keep doing it. I was not making enough money from my comic strip. I’m incredibly fortunate that Fun Home was as successful as it was, or I really would not have been able to keep cartooning. I don’t know what I would have done. I have no other marketable skills. But fortunately, I didn’t have to find out. So that’s one big thing, reaching a point where you’re making enough money from selling your books that you’re pretty sure you get to keep doing it. I mean, it’s a very materialistic definition of success, but how else are you gonna do it unless you’re getting enough money?

Alison, thank you for taking time out of your busy schedule to take part in this interview with INK Magazine!