Plastic Alchemy

Information Pack for Volunteers

Key Definitions and Overarching Themes

• A polymer is a large molecule composed of repeating chemical units covalently bonded together. Typically, there are more than 100 units.

• Polymers are found in nature (e.g. proteins and starches), and are also synthesised by humans from carbon sources, such as sugars and petroleum.

• “Plastic” strictly refers to polymers that are deformed permanently under mechanical stress (i.e. plastic deformation), but it is a catch-all terms for any type of polymer.

• Polymers can be brittle or glassy, breaking under stress. Others are fully elastic (e.g. rubbers), recovering their dimensions after the release of stress. Some polymers are viscoelastic, which means that they are elastic at short times but can flow liquid a liquid over long time. A good example is silicone putty, which can bounce like a ball but will also spread slowly on a flat surface.

• Plastics play a critical role in energy (fuel cells, batteries, composites for wind turbines, and photovoltaics), aerospace, medicine, pharmaceuticals, protecting infrastructure (e.g. coatings on bridges), and various high-tech applications owing to its light weight, durability, optical transparency, versatile mechanical properties, and easy formability.

• Plastic is useful with outstanding properties. We use it for a reason.

• Plastic manufacturing has a high carbon footprint and accounts for 4.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Plastic manufacturing has an associated environmental damage from its reliance on the petroleum industry, which is subject to spills and leaks.

• There are well-documented negative effects of plastic pollution on wildlife, especially in waterways

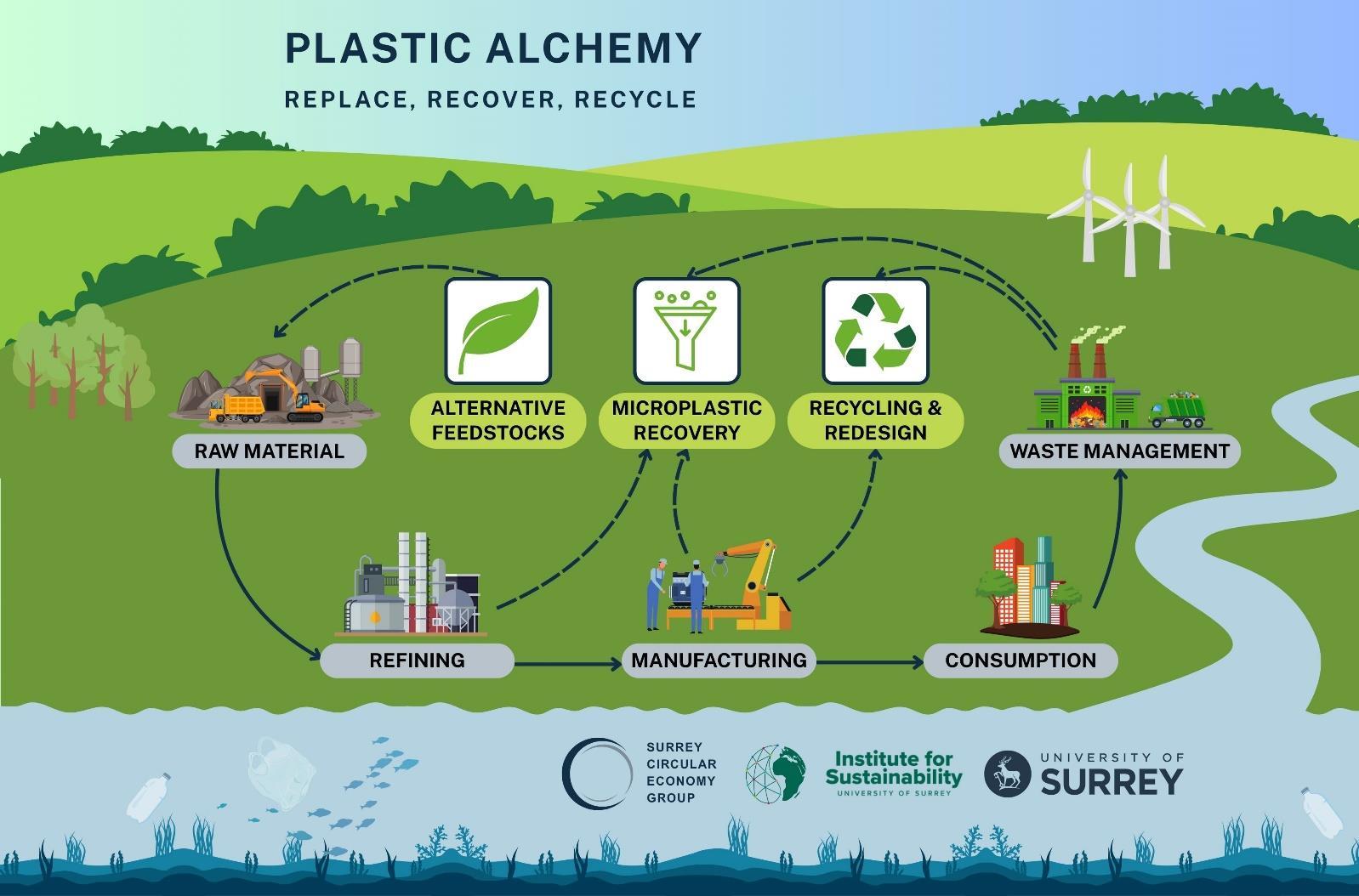

How Plastic Alchemy presents the issues above:

• How can we better use what we have and reduce the burden of plastic waste on the planet?

• Topics considered in the exhibition include replacing petroleum-based plastics with bioplastics and natural materials, preventing microplastics from going into the environment (especially water), and recycling plastic. (A related topic – but not explored in the exhibition – is re-using materials.)

Reduce & Replace

Key facts

• Every day, 1.9 billion plastic bottles are manufactured globally

• In the UK alone, 700,000 plastic bottles are littered every day.

• One way to reduce the use of plastics globally is to replace it with other materials.

• Glass is commonly used for the packaging of drinks. To meet Net Zero targets, there is a drive to move away from glass because of its high carbon footprint to manufacture and transport

• For the packaging of liquids, any alternative to petroleum-based plastics will need to have a low permeability and sufficient mechanical properties (e.g. to survive crush testing).

Which Materials Can Replace Petroleum-Based Plastics in Packaging?

Any replacement material should have a low carbon footprint. Furthermore, the properties should be competitive with conventional plastics, such as PET.

Pulpex is small-to-medium enterprise (SME) that has a promising solution: a bottle made from cellulose fibres (such as used in paper). This bottle is estimated to have a 30% lower carbon footprint compared to PET. The bottle can be recycled with paper, using existing facilities. And, if not recycled, the cellulose fibres degrade naturally in the environment. Cellulose is the most abundant organic molecule on Earth.

On its own, paper will not hold liquids. The Pulpex bottles are lined with a barrier coating with a low permeability to water, oil, and small molecules (e.g. surfactants). In the existing Pulpex bottle (recently being used commercially), the coatings are made from conventional polymers. The coatings are only about 5% of the weight of the bottle (on the order of 100 m thick). However, the bottles can still be recycled with paper in existing and well-established waste streams. (The bottles are intended for recycling – not for composting.)

Research at the University of Surrey is addressing a couple of challenges:

Challenge One: Making the interior barrier coatings with even lower permeabilities and zero pinhole defects, which will raise the shelf life of the liquid product from 6 months to the 2 years required in some applications

At Surrey, we are designing new coatings consisting of multiple layers to get the best properties from each. We are using computational modeling to understand how liquids flow through the coatings. Dr Solomon Melides is computationally modelling the water transport as part of an Innovate UK project with an industrial consortium.

Challenge Two: Replacing the conventional polymers in the barrier coating with bio-based and biodegradable materials, but without compromising properties.

We have been investigating a natural cellulosic material called "chitosan" as a candidate. Waste crustacean shells from the seafood industry are being processed to extract chitin, which is then processed to create chitosan. In combination with other materials, chitosan is functioning well as a barrier. It is fully degradable in the event that the packaging is not recycled, but small amounts of chitosan can also be recycled with paper. In the UK, chitosan is being manufactured from langoustine shells (waste from a scampi production facility) by a company in Scotland (called CuanTec). Solomon Melides is measuring the permeability through chitosan and multilayer. Grace Cohen, a PhD student funded by industry, is developing new degradable adhesives (for things like labels on bottles) that will make recycling easier.

Impact of the Research

• Lower environmental impact: lower carbon footprint and less plastic in the environment

• There will be manufacturing jobs creation at Pulpex and by their customers. Pulpex are presently setting up a brand-new factory near Glasgow, Scotland. The paper bottle technology was developed in the UK and can be exported globally.

• Pulpex are working with major global brands in the foods, drinks, personal care (e.g. shampoo), household goods (e.g. detergents), and cosmetics sectors who are seeking alternative materials for packaging their products.

• There could be spin-offs of technology in other sectors. An ongoing EPSRC project in collaboration with Pulpex, called SustaPack) is using computer vision, AI, multi-scale modelling, and new manufacturing methods

Key facts

• Globally, products such as sunscreens, cosmetics, facial scrubs, disposable wipes, washing sponges, and clothes all contain microplastic particles or fibres However, the use of microbeads in cosmetics and personal care products has been banned in the UK since 2018 .

• 50% of microplastic found in wastewater treatment plants are fibers from laundry washings.

• More than 700,000 microplastic fibers are released in a single wash of clothing

• Each day, billions of litres of household wastewater are sent to the wastewater treatment plants.

• Micro and Nano plastics could act as carriers of pollutants when they adsorb and/or absorb pollutants such as organic compounds, metals and pharmaceuticals These micro and Nano plastics can then be ingested by marine organisms and enter the food chain to pose potential health risks to humans.

Describe the area of plastic pollution that you are tackling?

A lot of products we apply on our body (i.e. glitters in decorative cosmetics) or wear (i.e. synthetic polyester clothing) contain microplastic particles or fibres, so when we take a shower or wash our clothes, these microplastics get flushed down the drains and end up in the local wastewater treatment plants. These microplastics can then break further to even smaller micro or nano plastics, making them difficult for current wastewater treatment plants to capture them.

Wastewater contains a lot of micro and nano plastics and if not recovered, then millions of micro and nano plastics could be released into inland waters and the sea.

How is it being addressed/how can it be addressed?

While some countries are banning the manufacturing and sale of products containing plastics, such as facial scrubs, not all countries have enforced this ban. To tackle the current levels of microplastics in wastewater, researchers are designing better filters for washing machines and wastewater treatment plants to catch the microplastics just before the treated wastewaters are discharged.

What are the issues with current solutions?

Currently there are no laws on how much plastics are allowed to be discharged into the environment, so companies are not forced to put processes in place to capture these plastics. This may change in the future

Filters are a good solution but are prone to clogging, so more research is needed to develop new filters and to understand how clogging occurs to enable more efficient filtering of wastewater.

How are you improving current research/design?

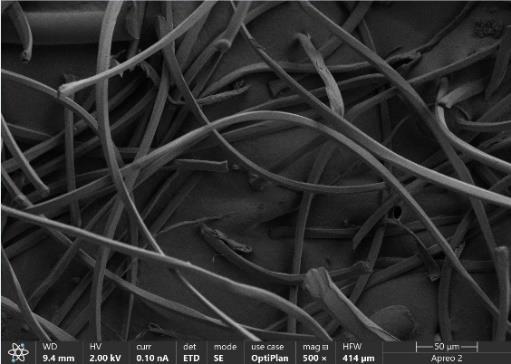

Real wastewater is complex with a lot of material other than plastics. However, to better understand the clogging, we need to first understand just the plastics in water, then the plastic in real wastewater systems. We are using real microplastics from textile fibers then cutting them into different sizes.

What does your research involve?

Our research focuses on the use of membrane filtration technology, using polymeric membranes to recover these microplastics so they are not discharged into the environment. We want to understand the impact of different sizes and amounts of plastic in water impact the clogging of filters. To do this we are looking at applying special coating on filters and changing the filtering conditions to minimise clogging.

What have you found/how have you improved on existing technology?

Microplastics can fragment or shed into much smaller plastics that can easily clog filters and making filter surfaces more “hydrophilic” reduces the clogging. We have also seen that it is important to filter at low pressures to minimise clogging.

What would success in your research area look like?

To reduce clogging of the membrane filters and allow the membrane filtration system to be run for a long time before you need to clean or change them.

If scaled up how will your research reduce plastic pollution?

Ideally to have our membrane filters installed at wastewater treatment plants to capture the micro and nanoplastics before they are discharged into local rivers.

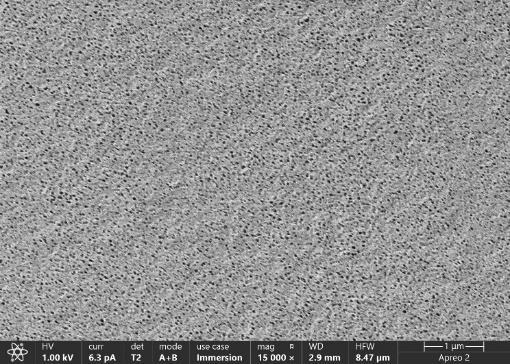

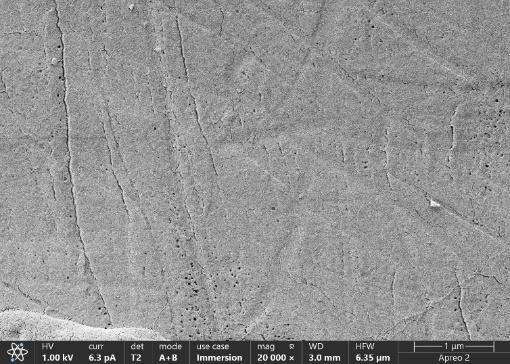

Pristine Polysulfone Membrane Fouling layer (biofouling) Polyester textile fibres

Key facts

• To improve the mechanical properties of plastic they often reinforced with Carbon or Glass fibres

• Composites have almost 30-50% plastic in them.

• Carbon fibre composites are as stiff as steel (sometime two times stiffer than steel depending on the type of carbon fibre) while it is almost 4 times lighter1

• So, it is not a surprise while its use in structures that need to be lightweight like aeroplane, cars or wind turbine are increasing.

• 75-85% of a modern formula 1 car body is made of carbon fibre composites2 .

• The global demand for Carbon Fibre Reinforced Polymers (CFRP) has tripled in the last decade and is expected to surpass 190 kilo tonnes by 20503 .

• Relatively short service life for planes and wind turbines (about 25 years)

• 85% of the composites produced in the UK each year are currently not reused or recycled at the end of their life. That's 94,000 tonnes of glass and carbon fibre composite waste going to landfill in the UK alone4 .

• Making steel is known to be energy intensive but making carbon fibre consume more energy than steel so it is very important that we reuse it.

• At the moment 30-40% of composites are wasted through manufacturing.

References

1. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym7101501

2 https://www.bpf.co.uk/article/plastics-in-formula-one-3292.aspx

3. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S135983681936946X

4 https://www.nccuk.com/what-we-do/sustainability/suscom/challenges/

Describe the area of plastic pollution that you are tackling?

Plastic plays a critical role in energy, aerospace, and other high-tech applications due to its lightweight, durable, and versatile properties. In aerospace and automotive sectors, plastics reduce weight, thereby improving fuel efficiency and lowering emissions key factors in achieving net-zero goals.

In the majority of high-tech applications, plastic is used in combination with other materials such as glass or carbon fibre as a composite. However, while plastics support technological advances toward sustainability, their widespread use creates a growing waste problem. The global demand for Carbon Fibre Reinforced Polymers (CFRP) has tripled in the last decade and is expected to surpass 190 kilo tonnes by 2050. Relatively short service life for planes and wind turbines (about 25 years) means composites will be entering the waste stream in significant volumes in the near future.

What causes this problem?

Without proper reclaiming and recycling, these discarded plastics will contribute to pollution and undermine the environmental benefits they help create. The big challenge in recycling composites is figuring out how to separate these materials from surrounding plastics in a way that uses less energy while keeping them strong and useful. The current in-process waste generated during manufacturing, also resulting in an immediate and growing problem. At the moment 30-40% of composites are wasted through manufacturing.

How is it being addressed/how can it be addressed?

What are the issues with current solutions?

Majority of composite are made using thermosets (type of polymers that are not easy to recycle). To recycle these currently plastic is burnt through Pyrolysis, the only commercial technology for recovering fibres, but not very environment friendly. Using thermoplastic (type of polymers that can be melted and reused) can significantly improve recyclability. However, there are still lots of processing issues with thermoplastics.

Thermoset: a plastic that irreversibly hardens when heated.

Pyrolysis: decomposition at high temperatures.

Other recycling technologies are being developed such as fluidised bed pyrolysis and chemical recycling, but these technologies are all at an early stage of development and, to become economically viable, they would have to achieve much shorter processing times.

How are you improving current research/design? What does your research involve?

What

would success in your research area look like?

The ability to recycle carbon fibre is critical to reducing its environmental impact Reusing the material with minimal reprocessing for second-life applications is essential however, we must first address the lack of a market for recycled materials.

Mechanical recycling is cheap and energy efficient but often provides inferior mechanical properties. Our aim is to increase demand by leveraging thermal and electrical properties of recycled carbon fibre in addition to mechanical properties.

Success means finding smarter manufacturing routes to reduce the manufacturing waste and create the knowhow of design with recycled materials. This will create confidence to design with recycled materials. Creating new opportunities particularly around multi-functionality will increase the opportunities for second-life applications and increase the circularity of composites.

If scaled up how will your research reduce plastic pollution?

Cutting down waste and using reclaimed material can lower the pressure on using raw materials.