SURFTIME THE JOURNAL

GROM POWER

WESTERN AUSTRALIA

CANGGU

WESTERN AUSTRALIA

CANGGU

With the collapse of the Bingin cliffs due to greed, Surftime asks, is an ethical future for tourism development possible in Indonesia? Or is it just too much to ask? For this month’s editorial, something a little different. We put this question to writer Jack Oneill Paterson. Here he is:

Bali, more so than any other surf location on the planet, is romanticized in the memories of old white men. Nowhere was as good, and nowhere has been so cruelly spoiled by fame. Nostalgia is a hell of a drug. Bali has always endured an unrelenting onslaught of slanderous commentary from surfers, critics and moral purists across the globe. It has been mocked for being inauthentic, over-populated, polluted, and sterilized. Whilst Bali’s early clientele of dope-smuggling surfers turned into today’s OnlyFans millionaires, buff business moguls, and Russian fitness bloggers, surely this would make for an interesting study in human metamorphosis. The cost of this change is never owed to the cynical expat.

Tourism, when done correctly, can be a great driver for wealth, education, and opportunity. For this to be the case, it’s important to ensure that the local community is running the show and not being taken advantage of, and it’s here that some well-meaning western surfing involvement might actually be beneficial.

Surfers should be aware of this. Whether or not we can help create ‘Surf Protected Areas’ has yet to be tested, but it’s a hell of a start. So far, 23 Surf Protected Areas have been implemented across Indonesia. When developers come knocking, the goal is for these communities to know the value of their land and surf. But let’s face it, development money talks.

Being forced to share the Bukit with a few hundred more friends is a flesh wound compared to the theft of local land and ecosystem destruction. Obviously, tourism in Bali is ripe with complexities, contradictions and ethical dilemmas, but most people’s disgruntlement doesn’t extend much further than the crowded lineups and traffic. Yet, the “surfing paradise” that may have disappeared over the years is felt firstly by the local community. What right do we, as western surfers who have committed every environmental and political sin, have to comment on the way another country chooses to monetize its resources? Well, we don’t really have one. Development be damned, full speed ahead. But, surfers may actually have a lot more to answer for here than one might think. Nobody, over the past 50 years, has been more efficient at exposing untouched utopias across the world than the humble surf explorer. While this is a very modest and low-impact example of foreign investment, it does sow the seed for unethical developers to descend upon the treasures.

And so, visiting these places like can be a remarkably good way to spend your money and establish this worth. If these communities are given the opportunity to develop sustainably, on their own terms, then you’re free to live your surf fantasies, knowing that your pennies are going straight into the communities, whilst also protecting ecosystems, culture, and local land ownership. Who knew you were such a philanthropist? Like growth, the diaspora of the privileged is unavoidable, and there probably will, one day, be ten other versions of Bali scattered across Indonesia. This will be good. This will be bad. But as always, it’s up to us to balance the two so that the people who call these places home will reap the benefits in direct correlation to our pleasures. Really now, as human beings, is this really too much to ask?

-J.O.P-Travel within Indonesia is becoming easier and easier for the young sponsored set, prepping them for the global travel that will surely come. Philip Duke, taking full advantage of a recent strike mission to the southeast. Photography by WM

Once an outland of mud and back breaking toil in the rice paddies, today Canggu is the new motherlode of rave tourism and development for the dreamseeker. Swerving this place of ancient agriculture into the hands of European interlopers and rapacious developers. Canggu now rivals the reputation of Ibiza as one of the grooviest places on earth to see and be seen. The thing is, just how much can it take? Because Canggu is all on its own. Once a surfing outpost, now an overpopulated colony, it’s been cut off from the rest of the Island of Bali. The natural disaster known as tourism, combined with an absolute lack of civil infrastructure to handle it, has resulted in a geographical isolation due to snarled traffic. From Kuta Beach to Canggu, once mere minutes of driving, is now a bad two hours of breathing near pure carbon monoxide. And the once promised green zone “shortcut”, is now a famed biblical traffic jam that becomes as full as an egg. This traffic is a result of a massive exodus of adventurers, scoundrels, criminals, dreamers, investors, carpetbaggers, draft dodgers and vegans who have forged Canggu into the most outlandish surfing community in the world. Astonishingly, usurping the Holy Grail of Uluwatu as Bali’s prime surf destination. Canggu has morphed into a miasma of every surfing creed, color, and philosophy drawn to its perceived promised land of cool for any surfer on earth who wants to reinvent themselves. Once an influencer’s paradise, now a paradigm. And all of this phenomenon happens minus the picture-perfect, clear blue, airbrushed dream tunnels that have made Indonesia every surfer’s fantasy. Canggu’s best waves break within a steaming hot beach break zone with silty, ricepaddy-run-off seas up against a dark, volcanic sand beach that at noon, can burn the soles off the hooves of water buffalo. A surf zone that is a bouncy castle for aerialists and a renaissance fair for retro riders.

Previous page:

Top Left: Tai Graham, still the one. Photography by Liquid Barrel

Bottom Left: Cold Beers and long boards, the song remains the same.

Photography by Simon Dobby

Right: The reason why at Black Sands Brewery.

Photography by Reynaldi Harisy

This page:

Top: Locals like Arya Blerong have the left wired and it shows.

Photography by Antonio Vargas

Bottom: Putu Andrea, Kadek Dafa, Putu Riski. Generation next is ready and willing. Photography by Antonio Vargas

Gemuk Swastika. Photography by Antonio Vargas

Sunset Session. Photography by Simon Dobby

Gemuk Swastika. Photography by Antonio Vargas

Sunset Session. Photography by Simon Dobby

Kadek Dafa. Photography by Antonio Vargas

The Lawn, Canggu , showing its

Kadek Dafa. Photography by Antonio Vargas

The Lawn, Canggu , showing its

Canggu, is the petri dish of restored western grooviness, art, fashion, food, multi-national sexual opportunity, and unchecked development, complete with the subsequent environmental and cultural disaster that such prosperity exacts. But despite its long being ground zero for the surfing hipster movement, the prime destination of a diaspora that longs for the way we were in the ’70s, Canggu is now reaching critical mass. Like a run-over Ibiza with rice, a place like this can only maintain its cool for so long. Today, the business of Canggu is business. And a swollen cumulonimbus of human over-saturation is fast approaching from the horizon. Tai Graham has managed to carve out a realm like no other in Canggu. A part owner of some of the hottest clubs on the island, he maintains his credibility by being the real deal when he hits the water. “It’s easy to sit there and complain about all that is going on here,” Says Graham, “but it’s just an evolution. And in many ways the best kind. Local kids are going to better schools, better hospitals, healthier, stronger, wealthier. A better future than back-breaking work under the sun, up to your knees in the mud for pennies? You wouldn’t want a better world for your kids? And their kids? C,mon man, we all live a great lifestyle here. The one we want. And all the issues will be dealt with. Just like anywhere worth dealing with.”

Sunsets do take all priority in Canggu, and none more than the one that sizzles into the horizon out beyond the “Old Man’s” surf spot. Once a refuge from the high-pressure lineups of neighboring Echo Beach, now Old Man’s features a parking lot the size of a football field. And at thirty cents a spot, it’s jammed without fail every evening. But still, this is one of the last local strongholds.

The Balinese people of Canggu still hold sway in their creaky bamboo warungs bursting with beer. Perched on the small limestone beach berm is a plywood promenade where one can get everything from a gin and tonic to a fresh coconut to a ten-times repaired rental surfboard. A local reggae band on a leaning wooden stage can be found on the beach blasting out hit after hit. All the songs you want to hear as the sun goes down in Bali. You know, “Hotel California,” “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” and the like. There is often up to eighty people in the surf. When the waves steamroll in, it’s carnage.

Home to the world. Photography by Antonio Vargas

Theo Radcliff. Photography by Antonio Vargas

Times Beach Warung, Canggu.

Theo Radcliff. Photography by Antonio Vargas

Times Beach Warung, Canggu.

Kahu Kereama Graham. Photography by Liquid Barrel

Made Dera. Photography by Antonio Vargas

Kahu Kereama Graham. Photography by Liquid Barrel

Made Dera. Photography by Antonio Vargas

Nose-riding girl longboarders and outback-bearded guys on retro boards clunking rails all the way to their disasters in the sandy shore break. There is often five hundred people on the beach and sundry dogs. Like the people, most of the dogs are imports too. Siberian huskies seem to be a favorite. Ask the old Balinese woman who was sells you three-dollar beers where you should pee and she will indicate the Ocean with a vague wave of her hand. Which was absolutely correct. Because vile, shattered, public toilets or no, in Canggu, it all goes there anyway. And you might think about the local surfers, with their club contests and their daily battles in the lineup with the hordes of famous guitar plunking freesurfers that come to visit. Which seems a perfect fit for Canggu. Most visitors in Canggu don’t want to listen to a band; they want to be in one. And yet, by the time the sun sets and you walk back to your rental scooter here, behind you, out there beneath a purple sky, are the waves. As they always will be. Hissing and crashing and pumping money into this place with the power of solar flares. And that’s a story this island knows only too well. .

Kian Martin. Photography by Antonio Vargas

Tipi Jabrik. Photography by Antonio Vargas

Kian Martin. Photography by Antonio Vargas

Tipi Jabrik. Photography by Antonio Vargas

Fraser Standen. Photography by Antonio Vargas

Jared Mel. Photography by Reposar

Jared Mel. Photography by Antonio Vargas

Fraser Standen. Photography by Antonio Vargas

Jared Mel. Photography by Reposar

Jared Mel. Photography by Antonio Vargas

Words

and Photography by Michael Kew

“Always do sober what you said you’d do drunk. That will teach you to keep your mouth shut.” —Ernest Hemingway

Boozing and deep-sea fishing have long been choice pastimes for visitors to seaside Kenya, the “Swahili Coast,” East Africa’s ancient crossroad that centuries ago was a kingdom of progress. In the 6th century a rumor of ivory lured Persians there, sailing south with the northeast monsoon, loading their wooden dhows with ivory and gold and animal skins, then reversing course and sailing north with the southwest monsoon, to growth and profit in the desert. That was the beginning. Soon wealthy city-states like Lamu, Malindi, and Mombasa materialized, each teeming with trade goods like African slaves for Arabia, leading to intermarriages of Arabs and Indians and Kenyans, spawning the Swahili diaspora, “Swahili” a derivative of sawahil, Arabic for “coast.”

Border to border, Somalia to Tanzania, Kenya’s sawahil is 360 miles of blue and white strewn with huge desolate beaches, dusty villages, weedy bays, cornfields, salt flats, coconut palms, mangroves, rivermouths, jagged cliffs, luxury resorts, mountainous dunes, mud huts, marshes, potholed roads, cargo ships, dhows, downtowns, and the dregs of an African-Arab-Muslim society today fueled by tourist cash, an ebb and flow which funds the entire coast, because today nothing is exported and because neither fishing nor alcohol can. So came the tale when Hemingway blazed through in ‘33, when tourists were rare, the American author a sauced rogue from afar, a Great White Hunter, his goal to shoot big animals and get drunk and see the Kenya of legend, at the time a bizarre British colony.

Between safaris he tried to hook billfish, eventually settling into smoky seafront pubs in Mombasa and Malindi, downing daiquiris with the tongue of Kiswahili surrounding him. Hemingway spoke none of the local language, yet absorption into the fray was never an issue, and he left an endearing if romanticized footprint 75 years before I decided to go there—but not for the fishing or safaris or iced fusions of rum.

“Kenya—just 39 years old and speaking at least 60 languages— has been many things for a very long time, but only one bewildered pretend nation for one generation.”

That was Binyavanga Wainaina in the July 2007 issue of Vanity Fair. One of Kenya’s new literary stars, Wainaina wrote with fire and aplomb, exposing and mulling the many problems and solutions of his great country. Kenya had been a sore victim of colonialistic centuries, freed at last from England in ‘63, but only recently it had morphed into somewhat of a positive place, economically and politically, something Kenyans gripped tightly, nurtured steadily— or so Wainaina said. “We have learned to ignore the shrill screams coming from the peddlers of hopelessness. We motor on faith and enterprise, with small steps. On hope, and without hysteria.” Hysteria was a bad thing to experience in Kenya, especially in the coastal towns where desperate thievery and violence seared through the local sector, targeting moneyed tourists who each summer flocked to the palmy beach resorts. Mombasa, Kenya’s main seaport and the coast’s largest city, was a smaller, saltier version of Nairobi, the energy and societal stink less visible, yet there was a certain charm

to an African city built on an island in an idyllic natural harbor, for centuries a hub for Arabian and Indian merchants, now site of an interesting Islamic heritage and a cultural complexity that was characteristic of all Swahili settlements.

It was a promise done from a promise made a year prior in Zanzibar, the Indian Ocean island best known as the name of many pubs worldwide. (“Bullshit,” you hear drinkers say. “There’s actually an island called Zanzibar?”) In July 2006 a surf magazine-sponsored crew to Tanzania eventually led me to that clove-scented isle. Our crew spent days searching in cars and dhows; we exhausted all resources and settled for less. We found surf but apparently were missing the point.

“If you want waves in East Africa, you’ve got to go to Kenya.” This was Troy, a white Kenyan who a few years prior had moved south to manage one of Zanzibar’s most upscale resorts, just up the road from the small, dirty motel we were staying in.

We spent our last night on Zanzibar drinking inside his nice Zanzibari restaurant where’d he’d been “chefing”—cooking—all evening. Tall and blond, age 31, cocky, with a sharp British accent gained from an English education, Troy bought us rounds of Serengeti Lager noting our desperation wrested from the bad tides and bad winds, minds adrift in nearby places where photogenic surf existed—Madagascar, Maldives, Mozambique. Our Tanzanian surf timeframe had pinched shut, but word of another African.

wavescape spawned personal plans for the next season, a year distant.

“Where’s the surf in Kenya?” I asked him.

“Don’t worry about it. Just meet me there.”

I vowed to contact Kenya Airways and see what they could do about getting me to Kenya at the prime nexus of wind, swell, and tide. From my home in southern California, Kenya’s capital of Nairobi was easily accessible, but certainly the Swahili surf was fickle—an expensive and iffy trip. Perhaps the beer had greased my decision to spend hard-earned cash to get there. But a year later it was still a promise, and as the plane from Nairobi sank toward the tarmac of Mombasa’s airport, the shimmering blue Indian Ocean below with its brown barrier reefs laced in white, it became clear that Troy had spoken true.

Hemingway: “In Africa a thing is true at first light and a lie by noon and you have no more respect for it than for the lovely, perfect weed fringed lake you see across the sun baked salt plain. You have walked across that plain in the morning and you know that no such lake is there. But now it is there absolutely true, beautiful and believable.”

Adapted from Swahilia, Micheal Kew’s new East African travelogue published by Spruce Coast Press. Available worldwide from Amazon. @michael.kew michaelkew.com

There is no lack of power in this piece of the Indian Ocean. The only question is, can you match it?

A local charger on his way to finding out. Photography by Jack O’Grady

There is no lack of power in this piece of the Indian Ocean. The only question is, can you match it?

A local charger on his way to finding out. Photography by Jack O’Grady

Mother of this land.

Mother of this land.

It’s the sky. That big sky above you. That’s what hits you first. The space of it all. A kind of eternity. Room to move. Western Australia for the surfer is about expansion. Expansion of the mind, expansion of your eyesight, you drink the place in as if your eyes and mind are thirsty for it all at once. And the quality of light in the morning, where cobalt blue swells march in like an army, impossibly beautiful and in perfect rank groomed by the offshore winds. Wind so clean and air so pure pushing at your back as you stand on the bluffs and take it in, all of it. And then the waves rear up and fringe and smoke and crash over the clear cold water and the white water appears impossibly white, like something alive, a species all its own. It is a breathless moment for a surfer when you set eyes upon this ocean off this land. And morning empties your lungs in anticipation and fills it back up with a kind of wonder, a kind of love. A love of the land and sea that you are not just an observer of, but a participant. It’s you who is going to jump off the edge of the continent, into the very forces that form the shape of the continent. It is you who will suit up with the thrilling smell of neoprene and and a bar of wax in your nostrils. And it is you who is going to join it all. This wild, big sky place with its cruising giant cotton clouds and its desert winds that seem made by the forces of nature just for you and these waves you are going to ride. Western Australia is one of those rare places that, with all that room, all that space, you cannot help but believe that you are exactly who you should be. And that this is exactly where you should be on earth in that moment. And then that first touch of the sea. Not too cold, just cooling. And you lay down on your board and you start paddling and now, now you are really in it. It’s the kind of place where you paddle out with nothing on your mind but the waves ahead. That first duck dive. And that sound. The waves of Western Australia sound like no other. A hissing, fizzing, roaring sound, connected to everything around you. And you take off on that wave and realize you are part of a majesty.

The way back with the founding fathers.

The way forward with Kelly Slater. Photography by Pete Frieden

The way back with the founding fathers.

The way forward with Kelly Slater. Photography by Pete Frieden

Crosby Colapinto, applying the power. Photography by Pete Frieden

Jacob Willcox, mastering the power. Photography by Jack O’Grady

Crosby Colapinto, applying the power. Photography by Pete Frieden

Jacob Willcox, mastering the power. Photography by Jack O’Grady

It is impossible to not think of how old the world is when you are in Western Australia. What has come before. The signs are everywhere. They come up through the soles of your feet and into the end of your fingertips. You can almost hear the echoes of the land and its original people who you are sure felt and feel the same things you are feeling when you are here. The profound belonging, the order of things on this earth. Where you stand, where you really stand, what you breath and what you think. And you smile quietly when you get it. The dreaming they called it. The original people here called it the dreaming. A belief in all that is around you. That connection that is here and so far from the madness of the world. Time slows here. Appreciation of your heartbeat grows here. And it seems the perfect way to think about what you are feeling. That dream of existence. Of how you are riding waves on a dream and in one. The journey you are on and the destination you have found. As much a thing of the body as the mind. Everything makes sense. Because it hits you, right in the chest. You are walking on a dream.

Crosby Colapinto, a scream in blue. Photography by Pete Frieden

Crosby Colapinto, a scream in blue. Photography by Pete Frieden

Our hero at the Margaret River Pro. Photography Matt George

Jack Logsen, in over his head at the box. Photography by Pete Frieden

Our hero at the Margaret River Pro. Photography Matt George

Jack Logsen, in over his head at the box. Photography by Pete Frieden

Fast, Confident.

Homegrounds: Halfway Kuta Beach.

Surftime call: “Natan’s aerial act is outrageous. High flying, connected and successful. He is already an expert at finding the speed he needs in small surf, finding the power spots. Watching him charge down the line is a joy because you just know he is going to pull something off. This young man takes his surfing seriously and so should we”.

Graceful, Committed Homegrounds: Legian Beach.

Surftime call: “This young lady’s frontside hacks are as good or better than the boys her age. And she does them smoothly, with a mature sense of power. Never desperate, her wave riding looks polished from take off to kick out. Paris finishes her waves on her feet with grace and polish. This is a class act”.

the benefit of great surfboards and an understanding of them,

at only 10 years

looks like a developing pro. You can see it in his eyes when he paddles for a wave, this kid wants to send it. Already boosting airs higher than he is tall, Rocco surfs tough. This kid is going places”.

Strong, Ambitious. Homegrounds: Legian Beach. Surftime Call: “With Rocco, old,Jhuan Nanda,12 yrs

Aggressive, Electric.

Homegrounds: Halfway Beach, Kuta

Surftime call: “That’s easy. This photo says it all”.

Philip Duke and his first love. Portrait by Matt George

Philip Duke and his first love. Portrait by Matt George

No fourteen-year-old boy escapes teenhood without a keen awareness of exactly how the world sees him, what it expects of him. He knows the weight of the world’s desire down to the ounce. Every day is of ferocious importance. Particularly to Philip Duke. He has a lot to prove. But he’s given up on proving it to others. They have all been too mean hearted. It’s all about himself now. Proving to himself that they are all wrong. And this takes a supreme effort. A focus. An isolation. An aloneness. An advanced sense of self. Even a coldness. After all, in his teen world, so much of it has been so cold to him. The ridicule, the jokes, the snide remarks, the deeply hurtful ones. And not only has he had to hear them, but he has had to take it. Still waiting for a life changing growth spurt at fourteen, still wanting to look his peers in the eyes without looking up, still waiting to be on a level playing field with girls, still waiting, he has suffered the ignorance of others. That meanness in this world. His physical size a constant and obvious issue. It is to any teen. But all those vicious peer judgements have been so brutal. Like running across a no man’s land of criticism while dodging the cheap shots the best you can. Hoping against hope that if others cannot help, then at least they could not hurt. Wishful thinking indeed. But so it goes in teenhood. The merciless test of not only how you take criticism, but how much.

It takes so much courage to attempt to grow up and become who you really dream you are. So as good a surfer as Philip Duke is, and as good as he wants to be, and as far as he is willing to go, there is no room for doubt. And arrogance becomes an asset. But the genius of Philip Duke, and it really is a genius, are the ramparts he has built around himself while he deals with it all. Cocksure, he is imposing his will upon this world. With unquestioned bravery in the surf and growing in skill daily, he has become a badass in any line-up. An accomplished and ranked boxer, he can kick the ass of anyone twice his size. And he has. Not afraid of being alone and away from the punishing ridicule, he often fills his days with his own joys and adventures, all alone. He knows his day will come. With golden sponsorship from Rip Curl and …LOST and a pocketful of trophies and international surf trips in the rear view mirror, it’s already halfway done.

A birds eye view of the playing field. Photography by Max De Santis

A birds eye view of the playing field. Photography by Max De Santis

Already possessing a heroic approach in bigger surf, Philip Duke’s deep bottom turns are going to fit into any wave he chooses to surf in the future, no matter the size. Photography by WM

Already possessing a heroic approach in bigger surf, Philip Duke’s deep bottom turns are going to fit into any wave he chooses to surf in the future, no matter the size. Photography by WM

He knows that his youth is not a time of life, it’s a state of mind. He knows that if you have a why in life than you can handle how. He has proven this to himself with his surfing and his winning and his focus on his upcoming glories. He has no interest in finding himself, he’s focused on creating himself. Focused to the marrow. With the lessons he has already learned about human nature, telling Philip Duke the facts of life is like giving a fish a bath. Why bother? Nobody understands 14-year-olds. Not even fourteen olds. But this kid does. He’s had to. Both the bad and the good. That’s teenhood for you. Like living in a zoo in the jungle. And enemies? Good. At least he knows he stands for something. And stands up to it. To hell with personal feelings, Philip Duke is about survival. And there it is. Life is hard, they say. Yeah? Says Philip Duke, compared to what?

Working with discipline on his aerial assault is paying off. Photography WM

Training all by himself with the dedication of Rio Waida, Philip Duke is on his way to the same place as his hero. Photography by Matt George

Working with discipline on his aerial assault is paying off. Photography WM

Training all by himself with the dedication of Rio Waida, Philip Duke is on his way to the same place as his hero. Photography by Matt George

Escape

Escape

Slide

Slide

Airborne

Airborne

Exhaust

Exhaust

Vaporized

Vaporized

Hope

Hope

That is no misspelling in the subtitle. The land-grabbing and development here is dizzying. This was written as a sequel to my “FLESH AND BLOOD” feature. A confession. I wrote this for myself, then sent it out freelance. I was surprised when it got published. —Mg.

An excerpt from the new book IN DEEP: The collected Surf writings of Matt George (with a foreword by Kelly Slater) Di Angelo Publications, 2024Publications, 2024

June 10, 2012 — Uluwatu, Bali, Indonesia It is your birthday. You are a surfer. Today, you find yourself eight degrees below the equator, standing on a cliff’s edge in the backyard of a luxury villa of Uluwatu, Bali, overlooking the famed surf break. Considering a fall over the vertical 300-foot limestone cliff makes your knees go wobbly. You have your surfboard under your arm and a waterproof pack on your back. You are going to climb down the cliff’s southern path and you are going to walk, surf, and paddle the entire Bukit Peninsula over the next three days. You will be dusting off memories. Your first visit here was twenty-eight years ago. When things were much different.

With your peripatetic lifestyle, you and Bali have crossed paths innumerable times in the past. But you live in in Bali now. With a full-time job here, the proper green card, and a local woman you are planning to marry, you are no expat. You are an immigrant. Drawn to this far-off place, far from the USA because of the different brand of freedom it offers. An adventurous kind. A romantic kind. And because you have never been able to shake her call. A courtesan, Bali makes you feel special, makes you feel like you are the only one on earth who loves her in the right way. Even though millions of others can have her, too. And they do. Anytime they like.

You are drawn to Bali and the Bukit Peninsula because of the daredevil rules here. Watch your back, make the right friends, no sudden moves. Like any jungle, that’s what gets you noticed— sudden moves. And then you get eaten. And you find there is a strange beauty in knowing that. Here, it’s every man, woman, and child for themselves. Survival, but with perfect waves and the freedom of taking care of oneself without anyone sticking their nose in your business. Unless, of course, you fuck up. Then it’s all over. As sure as a popped balloon. If not the horrors of the Kerobokan jail, then surely an escort to the airport and an economy flight back to wherever the hell you came from. But you love the risk. Bali is Dodge City with palm trees. And you, the gambler, but you are not drawn to the dark side. The illegal. Because knowing you can be anyone you want to be here is enough. You can reinvent yourself. Or just be who you always were with no trouble from nobody.

No government, no cops, no hassles. Just keep your paperwork in order and don’t pop any flares. Then it’s all smiles. As long as you are aware that here, the smiles are like icebergs, where unimaginable dangers lurk below. Romantically, philosophically, physically. Good luck. As long as you keep your nose clean, don’t misstep, and thank the spirits everyday—whether you believe in them or not—you just might make it. Remember, you

have no rights here. Only privileges. Only savvy will see you through. From the booze-addled, sex-brutalized carnival of the construction site formerly known as Kuta Beach, to the eat, pray, love of the creaking bamboo forests of Ubud. And you know this. Learned this. All the while, Bali intertwined herself with your fate. Your station in life. You are here now. You are fifty-three years old. You reach the bottom of the cliff, just. The frayed rope section was a little hairy. You walk the beach along the secret cove, past the topless sunbathing Germans, crunching along in the seashell sand, your feet covered in mittens of the stuff. That has never changed.

You can smell the cliffside Uluwatu village up ahead. The cliff sagging under the weight of the astonishingly irresponsible real estate development. The luxury villas, the beer-soaked warungs— bars and resorts—the sewage, the litter, and the paper money that drives it all into the sea. Scads of paper money. You can remember a time when there were only three warungs up there. So it goes.

The surf’s not half bad and there’s only sixty-five guys out. It is off season, after all. You’ll put in at the cave, grab a wave, and make your way to Padang Padang for the night. You can see the Bukit white kids are out in the surf, their porcelain skin standing out amongst the brown. There is always brown skin in the lineup now; that is one thing that has changed for the better. The locals have taken this place back from the invaders. Not the empires of the Dutch, the English, nor the Japanese could take this island forever. Why should it be any different for the Western surfers? We could only hold the place so long. Too much treasure.

The twelve-year-old Balinese girl, who once carried your surfboards in on the footpath to Uluwatu for one dollar, is now a millionaire. Her family was able to lease their cliffside land to one of the Korean Resort Developments for twenty years and six million in cash. The Koreans brought the money in suitcases that night. It took the young lady’s family all night to count it. And another day to wrap it in foil and plastic and bury it in various secret locations near the temple. The young lady, now a rich woman of forty, still sells her homemade bracelets to the tourists for a dollar a pop. As she always has. All her life. This woman has no idea what she is going to do with her share of the millions. Despite the fact she has never been more than four miles from the Uluwatu Temple, she is thinking of buying a car. Though she’s not sure she wants to go anywhere.

To read full story and many more visit www.diangelopublications .com/books/in-deep or Amazon.com

Surftime Editor Matt George, Uluwatu, 1984. The beginning of a 40 year love story. Photo Bernie Baker

Surftime Editor Matt George, Uluwatu, 1984. The beginning of a 40 year love story. Photo Bernie Baker

Kelly Slater, looking fit and athletically composed, carries a new wetsuit and two fresh surfboards under his arm as he strolls toward the WSL accreditation booth where he will pick up his all access pass to the Margaret River Pro in Western Australia. It seems like a bit of a joke, really, as if he would really need a pass at any WSL contest to go anywhere he damn well pleased. This the truth, considering the fact that he casts his own shadow at any contest site, even on cloudy days. His star power is as overwhelming as it has ever been. When he paddles out for a heat here, the crowds swell to three thousand. When he paddles in, half of them go home. Griffin and Jack are just a blips on the radar by comparison, considering all the rumors of yet another possible retirement announcement from Kelly buzzing around like the very flies that annoy all visitors to Western Australia. Still, on this beautiful bluebird day at the most spectacularly beautiful site of all the WSL contest venues, Kelly seems no where near quitting. And why should he? He has never had any quit in him. That and the fact that he whsipers to you that he only needs eight good waves in this contest to be back where he belongs. The confidence with which he makes this statement makes you feel as if it is preordained. So you think of it this way, if you were a 52 year old boxer maintaining your stadium filling status and still striking fear into the hearts of opponents less than half your age, would you quit? One look in the eyes of a certain rookie as he waits behind Kelly to get his competitors pass puts all this talk about Kelly now being the easiest draw in the field to rest. That is something that will never, ever be. And anyone worth their salt knows it. And as Kelly grabs his VIP passes and walks with timeless purpose toward the changing rooms, you see this rookie watch Kelly go until the woman in the booth has to remind the rookie of why he is in line. And later, ready as a warrior, Kelly makes his way through the pre-contest civilian crowd like Moses parting the Red Sea. And you can sense, like a powerful spoor in the air, the respect that Kelly still garners and wears like a Viking Laird’s wolf skin. Then, after a few smiles and how-ya-goin’s to some worshipful little kids, Kelly paddles out into a pre-contest line-up of such talent that it seems that aliens have landed and have taken over the break. My God, you think, how far surfing performance has come. And then the great man takes off and there it is. The class act. Hip surgery or no, Kelly Slater is, as he has always wished to be, is as he once declared long ago “fitting into the patterns of water”. And all the questions about his retirement are answered on that one wave. Kelly will never be leaving the ring. Nor should he. If nothing else, he is still the DNA strand of what makes Pro surfing fascinating and meaningful. And with a lifetime of wildcards ahead of him in the most meaningful competitive surf spots on the planet, Kelly will never surf a legends heat as long as he lives.

It’s not

are, it’s

how old you

how you are old. Kelly Slater, looking back into the future. Photo Tom Servais. Photography byTom Servais

how old you

how you are old. Kelly Slater, looking back into the future. Photo Tom Servais. Photography byTom Servais

With an alarming rise in catastrophic drunken rental scooter crashes here on Bali, we offer this true story as a cautionary tale to all who visit.

-Editor-

Her name is Jilly and she is just 18 years old and she is lying supine on a hospital bed in a windowless room in a small, dusty hospital in Denpasar, Bali. She used to have beautiful blue eyes. She only has one now. After the accident. Torn out by a branch on the side of the road along with three of her toes that were ground off her left foot by the asphalt. The amount of skin she has lost on the left side of her body is horrible. With that one eye she stares up at the buzzing fluorescent light on the ceiling and listens to the lonely sounds of the hospital hallways and feels her memory sluggishly coming back. Her concussion is making her eye tear up over and over. Or maybe it’s just her numbing sadness. It was night and, as usual, her boyfriend was maggotted on shrooms and Jim Beam and they were tear assing around Uluwatu from booze up to booze up. Coming into to hot to a sandy curve on their crappy rental scooter and the blinding high beams of a water truck was all it took. Christ, she thought, what were we thinking? She in a bikini and sarong, and the idiot barefoot, boardshorts and a cigarette. She moves under her bandages at the thought and the searing pain of them coming loose from her raw skin on her hip makes her draw air in between her clenched teeth. She closes her eye and let’s the pain settle. She feels disconnected from everything. Life, family, love, the world. And she is still not sure how she feels about the idiot’s death. That is what she is calling him now. The idiot. She feels anger toward him, certainly, rage really. She told him a hundred times to slow the f*ck down. And it was never love anyway, just a schoolie hook-up. She gazes at the ceiling, and questions who she really is, what kind of person she is, for feeling nothing for the idiot who is dead. And God, she thinks, Mum and Dad on the way from Oz, what the f*ck am I gonna say to them and how the f*ck are they gonna handle the cops? This is gonna cost a my parents a fortune. And one eye? Jesus. I’m done. She knows the numbers now. She has been given a pamphlet that a silent nurse has handed out to everyone in the ward on this Sunday night. She knows now that over ten thousand tourist scooter accidents are reported every year in Bali. Twice that if you think about the unreported ones. And at least a thousand deaths. One thousand and one now, She thinks, that idiot. And again she winces at her cold heartedness, but forgives herself a moment later. It was all the dumb f*cker’s fault anyway and now I’m scrwed for life. And she barely knew him. Couple of drunken tumbles into bed is all. And she had always been told how pretty she was and then the perfect figure happened in her teens and now the accident has ruined her. And that makes her wince again. What is Mum gonna think? And am I gonna cop it from Dad. Jesus. And I reckon netball is over for life. I guess I could swim? This last random thought makes wonder what the hell she is thinking and so she moves again and hisses in pain as

all the bandages seem to stick at once. She strains and absorbs the hot pain and reaches up with her good arm and hits the button for the nurse. The pain is really throbbing now, half the skin on her left side is gone and all the sutures suddenly feel too damn tight. Like feeding black caterpillars all over her left side and the one snaking up her chin and over her cheek to her empty eye socket. It’s the freedom of the goddamn things, she thinks. You get over here and you hop on a scooter and the wind is in your hair and the sun on your skin and the things feel like an amusement park ride. You can’t believe you are allowed to behave like this and drive like this and everybody is doing it and the surfboard racks and the ripping up to surf spots and the fun and freedom of it all. Problem is you’re no good at it. And you have no experience with scooters and the goddamn things are awkward on the road and the roads are kinked and potholed and awkward too and trying not to get hit by cars is like being inside a video game. And then the booze and the shrooms and the speed and the freedom of it all is tailor made for fun and sex games until it all comes crashing down in a scraping, agonizing, face ripping, heart wrenching instant and someone is dead as a coffin nail. And you? You’ll be all scarred up and have to wear a black eyepatch for the rest of your life. And your were always told how perfect your skin was. How pretty you were. F*ck.

She watches the silent nurse approach and reach up and open up the painkiller I.V. drip a little more. A warmth grows from where the tube is inserted into the back of her right hand. A number of the other patients are signaling and calling for the same treatment like defeated zombies. And then she feels the nurse lay a gentle hand on her forehead and hears the nurse say, Tidur, cantik, tidur. And with that the nurse steps over to the other patients. And Jilly looks up at the ceiling with her one eye and thinks about how life’s greatest regret is knowledge learned too late. Had she’d known. Had she only known. She never would have got on the back of the goddamned scooter in the first place. The tears have come again to her eye and Jilly stares through them at the fluorescent lights on the ceiling, staring at nothing. Nothing.

Bali- Popular Tourist Destination Bali has had enough of unruly motorcyclists. Foreign tourists will not be allowed to use motorcycles or scooters to get around the Indonesian island after string of accidents led to injuries and deaths.

“They are disorderly and they misbehave” said Governor Wayan Koster, adding that from now on, foreigners should only use modes of transport prepared by tourism services that meet certain standards “to ensure quality and dignified tourism”. It remains unclear how the ban would be upheld.

It’s all fun and games until someone dies. Photography by Mason Loggie

It’s all fun and games until someone dies. Photography by Mason Loggie

On the morning of January 6th, a day when the political drama currently unfolding in the U.S. House of Representatives dominated the news cycle, CNN.com ran this bold banner headline: “Mad Dog” Surfer Dies Riding Giant Waves In Nazarè, Portugal.” Similar stories could be found on sites of The New York Times, BBC News and The Guardian, the features reporting on the unfortunate death of Brazilian big wave surfer Marcio Freire, who apparently drowned following a wipeout at Nazarè’s notorious Praia do Norte. Even as the global big wave community grieved, processing the loss of this popular, though largely unheralded, fellow heavy water devotee, the level of international coverage of Freire’s passing serves to highlight two related realizations, one relatively new, the other quite old. First, that giant wave surfing has really pushed itself to the forefront of broader society’s awareness (seen any CNN stories about Filipe Toledo’s choice of boards at Lowers lately?), with coverage of intrepid male and female surfers apparently cheating death while riding mountainous waves at spots like Praia do Norte captivating civilians and capturing headlines like no other time in our sport’s history. The second—and this realization has been with us since earliest days—is that despite how absolutely catastrophic big wave wipeouts appear, surfers very rarely die while surfing giant waves. Which raises the question: just how dangerous is big wave surfing today?

This isn’t the first time the question has been raised, not by a long shot. On a 1965 issue of SURFER Magazine the neon cover blurb read: “Big Wave Danger—A Hoax!” In the related feature Peter Van Dyke, brother of big wave pioneer Fred Van Dyke and an experienced waterman his own right, wrote:

“I’m awfully tired of all the phony talk about big surf with descriptions of death-defying surfers and those lousy Hollywood movies with all the dramatic background music for the rolling, tumbling surf and bone-breaking dialogue. Big wave surfing is a hoax! Why? Because riding big waves isn’t perilous, dangerous or as hairy as it’s cracked up to be. In short, riding big waves is overrated.”

While Van Dyke certainly was entitled to his opinion, and the exact meaning of “hairy” can be left up to personal interpretation, the term “danger” can be defined, and often is, as “exposure or liability to injury, pain, harm or loss.” The apex of these eventualities, of course, being death. But if danger means simply to run the risk of the worst happening, then the only way to accurately measure danger is with statistics. Viewed in this light, using number of deaths and serious injury per participants total over, say, a sixty year period, the analysis of existing data would indicates that big wave surfing isn’t all that dangerous. In all those years, for example, less than a dozen surfers have reportedly been killed riding big waves [read: 25 feet and over.]

So with this being the case, and vastly more surfers being hurt, seriously injured and even killed in smaller surf conditions, why aren’t we all slipping on our inflation vests and waxing up our tenfooters during the next XXL swell? The answer to that question could be because of what big wave surfing has in excess, in lieu of statistical danger, is fear.

Ask “Why?” of just about any big wave surfer and the topic of fear will inevitably come up, most commonly framed in context of using fear, recognizing fear, controlling fear…making a friend of fear. Lots of fear talk. Which is perfectly natural, and no mere rationalization. Because while for most other extreme athletes death could result from a mistake, as soon as a big wave surfer’s head goes underwater, they’re dying. Which is why just about any wipeout is traumatic, and big wave wipeouts exponentially so. Peruse any list of the five phases of drowning and phase number one may surprise you:

Surprise

In this stage the victim recognizes danger and becomes afraid.

Small wonder, when those who study this sort of thing report that “…the physiology of submersion includes chilling items like fear of drowning, diving response, autonomic conflict, upper airway reflexes, water aspiration and swallowing, not to mention emesis and electrolyte disorders.” Recognizing the terms or not, that’s a lot to have running through your head while experiencing a two-wave hold-down at Maverick’s. Which is why big wave surfing, while it might not be statistically dangerous, is extremely, viscerally, scary as hell.

And yet this sort of trauma is something big wave surfers find themselves experiencing on a regular basis…and still going back for more. In 2012, for example, San Clemente’s Greg Long was pulled from the water after a three-wave hold-down at Cortes Bank, unconscious and near death, but then was one of the chargers out in max-size Todos Santos during last week’s megaswell; in 2013, Brazil’s Maya Gabeira’s lifeless body was dragged from the Nazarè shorebreak and revived with CPR, yet in 2020 she entered the Guinness Book of World Record riding a 73.5 ft. giant at the same fearsome break.

There’s no question that today’s big wave surfing is decidedly less dangerous—and maybe just a little bit less scary—than ever before, what with rescue teams, inflatable vests, heavy-water training and emergency protocols in place. And still Marcio Freire, an experienced surfer wearing a flotation vest, surfing in a lineup patrolled by a number of PWC teams, tragically died at Nazarè. A stark reminder that while death in big waves is not probable, it is still possible. Those rare surfers are the ones who have accepted those conditions, judged that the reward is worth the risk, and move toward the sound of thunder, while the rest of us watch from the safety of shore.

It’s been going for awhile now. Jay Moriarity, Mavericks, December 23rd, 1994. Photo by Bob Barbour.

It’s been going for awhile now. Jay Moriarity, Mavericks, December 23rd, 1994. Photo by Bob Barbour.

The boy becomes a man. Varun Tandjung, all grown up, trained up, fueled up and surfing with authority in his homegrounds.

The boy becomes a man. Varun Tandjung, all grown up, trained up, fueled up and surfing with authority in his homegrounds.

It is a glorious day when a surfer hits the water all healed up from an injury and long recovery.

Bronson Meidy, back in tune and blowing minds again at Keramas.

Bronson Meidy, back in tune and blowing minds again at Keramas.

FOCUS EXHILARATION DEVOTION INTIMACY

There is something special about watching a local rip his local break. Made Balon, carving his initials into a Canggu

wall.

Photography by Antonio Vargas

wall.

Photography by Antonio Vargas

and

and

we find ourselves

The bays

coves

beaches

surfing during the magic sunset hours of our days will linger in our memories forever.

Agus Firmanto revelling in his time.

The bays

coves

beaches

surfing during the magic sunset hours of our days will linger in our memories forever.

Agus Firmanto revelling in his time.

Another incredible year of waves and surfing with world class action in and out of the water!

Saturday started with open mens and womens providing entertainment for the crowd through the course of the day. Stand outs including Rizal Tandjung, Shane Sykes , Western Hirst and Jaleesa Vincent.

Sunday’s finals day had perfect 4-6 ft waves on offer, there was nothing short of high flying world class twin fin surfing taking place. The mornings quarter finals set up for what was to be one of the best afternoon of finals and surfing we have seen for the Twinny Finny surfest. From the charging junior boys and girls,

to the highly anticipated opens women’s and men’s, all categories provided pure entertainment for the bustling batu bolong beach.

As the sun set, Kura Kura beers flowed to a completely packed beach of surf fanatics. So stoked.

The bar has been set and we thoroughly look forward to seeing you all next year for the 6th annual Twinny Finny surfest world championships.

Thanks all of our sponsors Kura Kura, billabong, JS, Onboard store, Channel Islands, DHD, Pyzel and ASC.

Rip Curl has celebrated it’s Canggu Store soft opening by hosting a Girls Go Surfing Day with Taina Angel Izquierdo on March 27th bringing at least 40 girls together in Batu Bolong Beach to surf, support each other and have fun for the day.

The design of the store brings back modern industrial design of exposed steel structures and the use of recycled teakwood and ulin to bring some of that rustic feel into the store. The idea was then to take that language and combine it with something more contemporary, which reflect the vibrant character of Canggu.

1ST floor carries full range of Men, Women and Kids apparel and a section to introduce Rip Curl surfboards.

2nd floor is the Surfboards area, with DHD, FIREWIRE and PYZEL as the pillars, a hardware section and a complete collection of Wetsuits for both Men and Women.

The major positives about giving more volume with that extra height is to give a sense of breather, given the context of the surrounding that is packed and visually busy. Here is the space, when you enter you feel at ease, to look at what Rip Curl brand is, the history wall, and eventually to find the products that you need from the extensive collections.

The Location

Rip Curl Canggu

Jl. Batu Mejan, Canggu

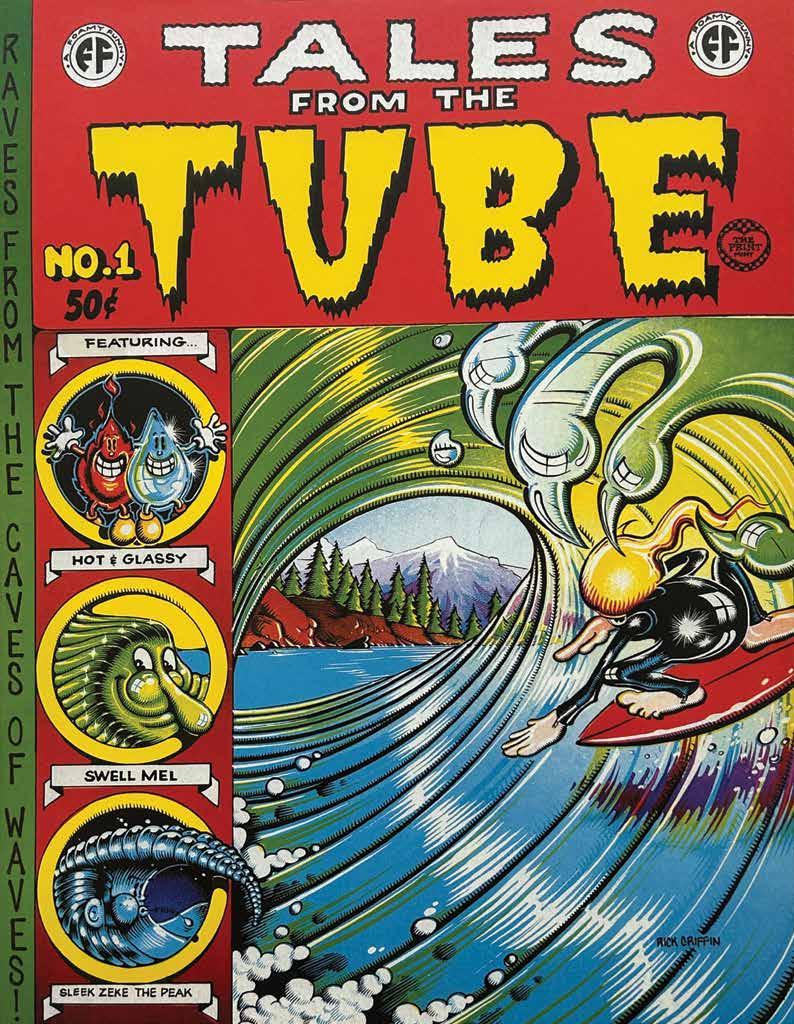

What a time it was. And what an artist to capture it. By 1970 the shortboard revolution had taken us to places on waves we could never have imagined. And, due to the prevalent drug culture of the times, to places in our minds as well. And it took a surfer/artist like Rick Griffin to manifest the cosmic vision. Famous for his flying eyeball Jimi Hendrix posters and putting the Grateful Dead on the map with his electro skulls, when Griffin turned his mind to his first love of surfing, it became ours. Let us never forget the “Murphy: cartoons of Surfer Magazine either. All said, Rick Griffin captured an era in ink. An era that still resonates today in Bali, especially in Canggu. Take good look at these pieces. One a spectacular naivety in comic cold water form and the other a reflection of the mother ocean (Which was also the poster for a seminal surf movie by John Severson). All told, an inner vision of the times from an surfer who was deeply connected to the sublime beyond the edges of our imaginations of the times. In honor of Rick Griffin, who is no longer with us, Surftime will dedicate a double page spread in our next issue to any artist that can capture the cosmic connection of our current times here in Bali. Open your minds and blow our minds. Send all submissions to: Surftimemagazine@gmail. com. We look forward to your vision.