WASHINGTON

A collection of writing and artwork by local people celebrating stories of Washington both real and imagined

e

A collection of writing and artwork by local people celebrating stories of Washington both real and imagined

e

e Writers:

Lisa Burns

Tom Davie

David Farn

Neddra Antoinette Freeman-Danby

Kate Garlick

Gillian Harrison

Andrea Lynn Henderson

Christophe Hodgson

Meryl Mathieson

Pauline May

Sharon Milley

Roger Morris

Ged Parker

Angela Richardson

Kevin Robson

Owen Saunders

Nicola Spain

Rob Walton

Bethany Watson-Wilkes

Peter Welsh

Aaron Wright

e Artists

Sally Anderson

Natasha Armstrong

Phil Barker

Anthony Barstow

Mike Clay

Zoe-Marie Dobbs

Denise Dowdeswell

Neddra Antoinette Freeman-Danby

Jan Goulden

Jo Howell

Hannah Kelly

Lyn Killeen

Pui Lee

Meryl Mathieson

Peter McAdam

Poppy Middlemas

Claire O’Brien

Kimberley Roworth

Angela Sandwith

Karen Sikora

Lily Stone

Michael Treasure

Brenda Watson

Barrie West

Claire White

James Wilkinson

Lesley Wood

Bright Lights Young Artist Collective

Creative Age

Design by Tommy Anderson

Around and Around We

Bethany Watson-Wilkes

e Ivory Bangle Lady

Neddra Antoinette Freeman-Danby

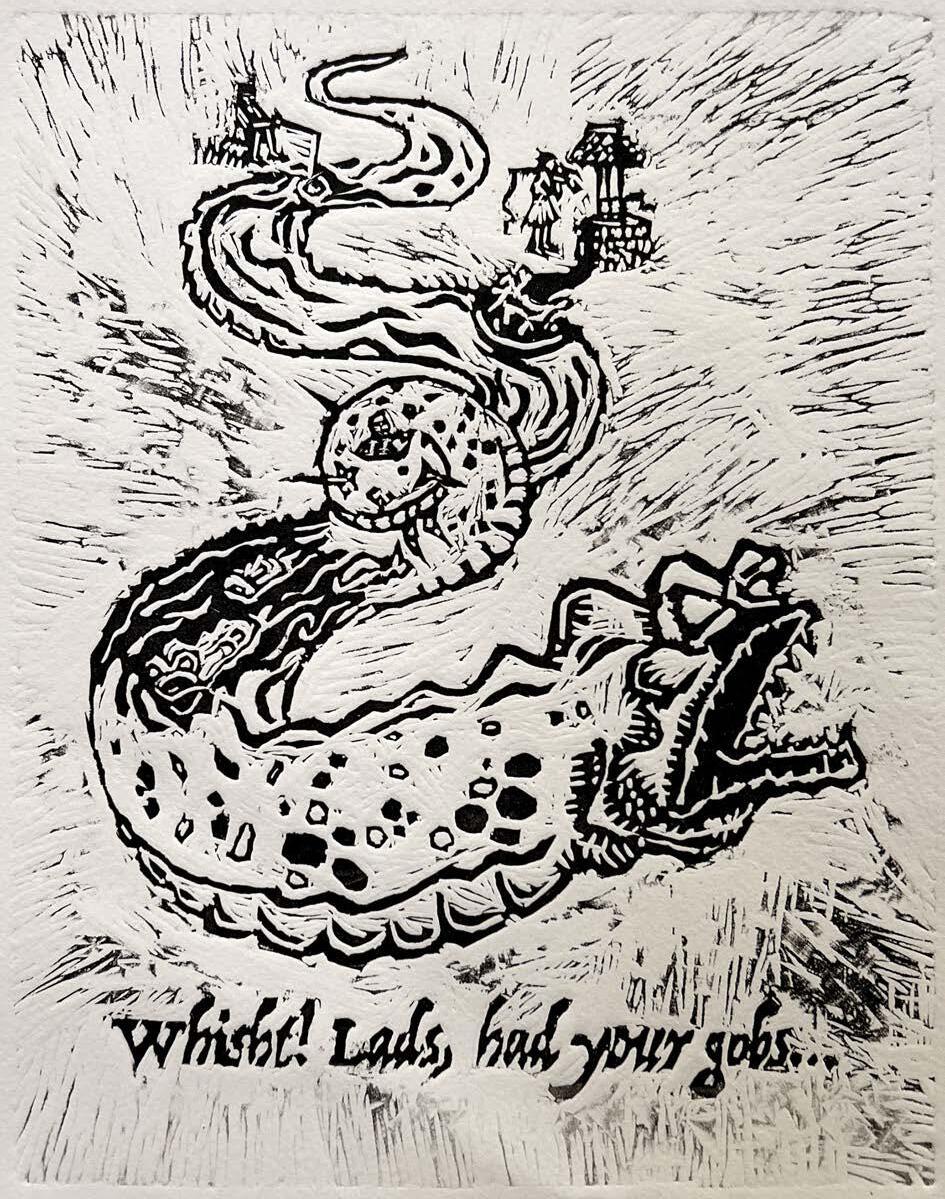

Wyrm

Aaron Wright

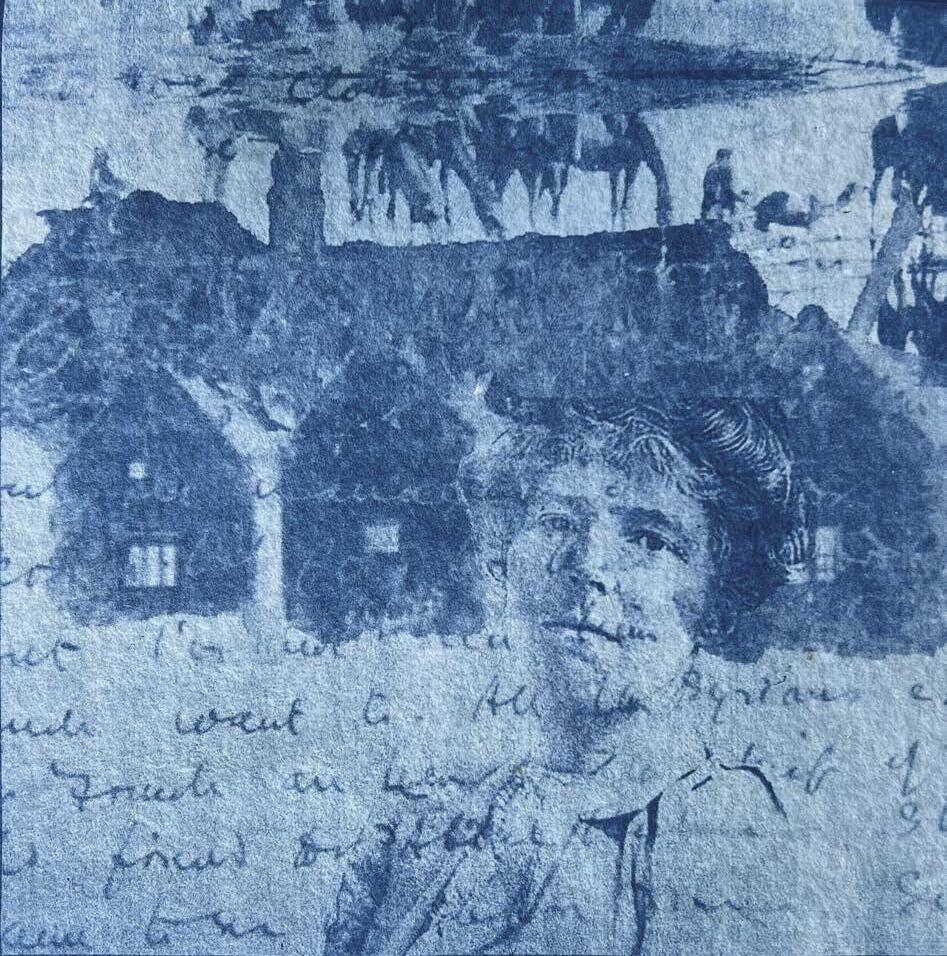

Searching For e Real Gertrude Bell

Andrea Lynn Henderson

Trip

Rob Walton

e D Villages

Sharon Milley

Villages of the Damned

Sharon Milley

Lamby Worm

Sharon Milley

e Little Girl I Used To Know

Owen Saunders

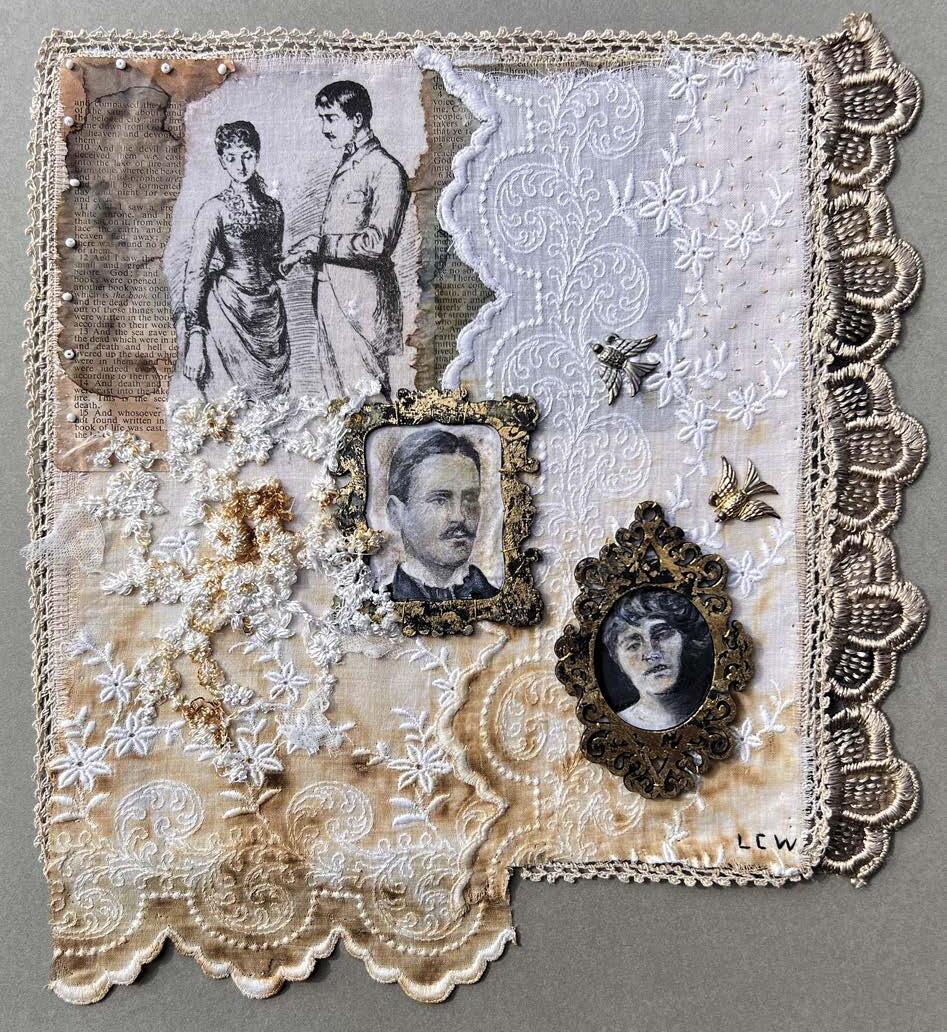

19th August 1851, 11.30pm

Lisa Burns

Romano’s Café

Nicola Spain

e

Nicola Spain

An Awful Story

Kate Garlick

Galleries of Memories

Gillian Harrison

e Promise

Christophe Hodgson

em

Tom Davie

Ukraine and the Eagles

Meryl Mathieson

e Trial of Jane Atkinson

Kevin Robson

e Boy in the Chimney

David Farn

Log Boat

Pauline May

A Royal Dinner

Angela Richardson

Did Washington New Town succeed?

Ged Parker

e Stangroom's Washington's Own

Roger Morris

A Lambton Tale

Peter Welsh

Acknowledgements

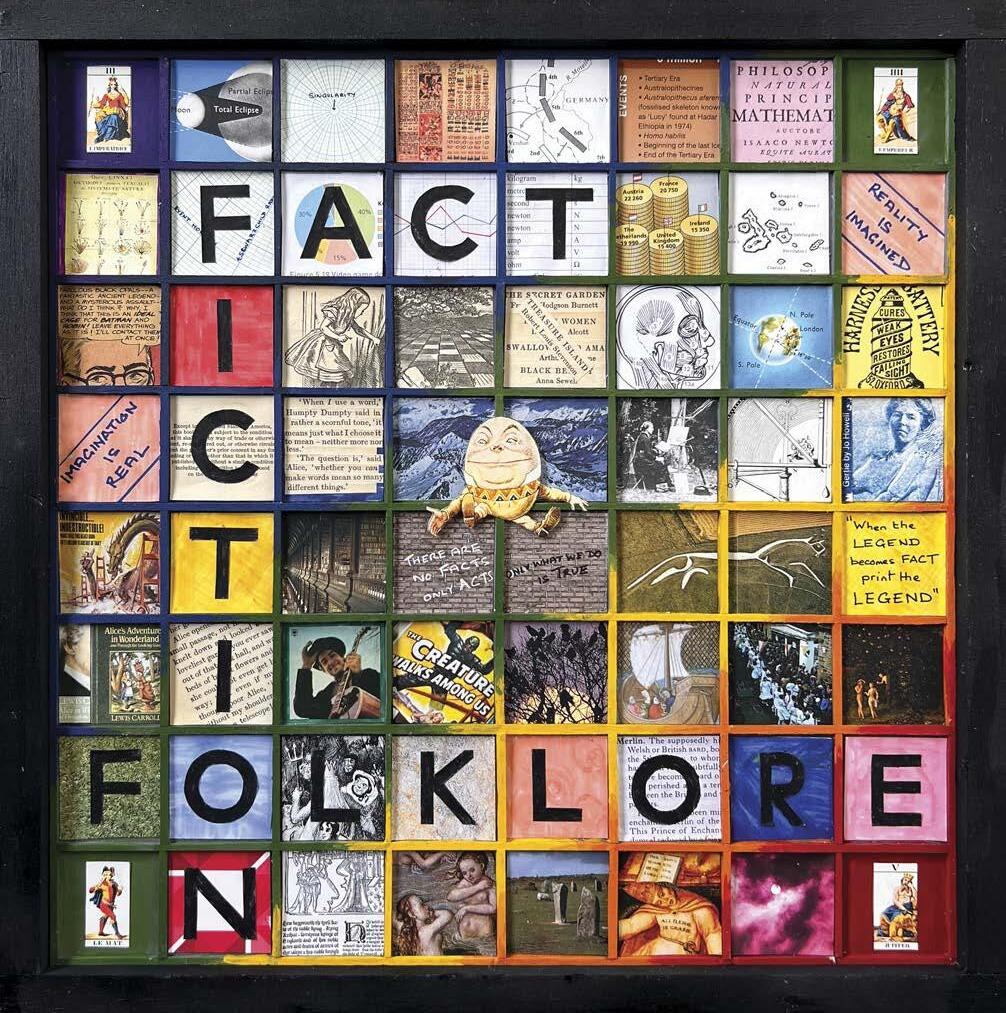

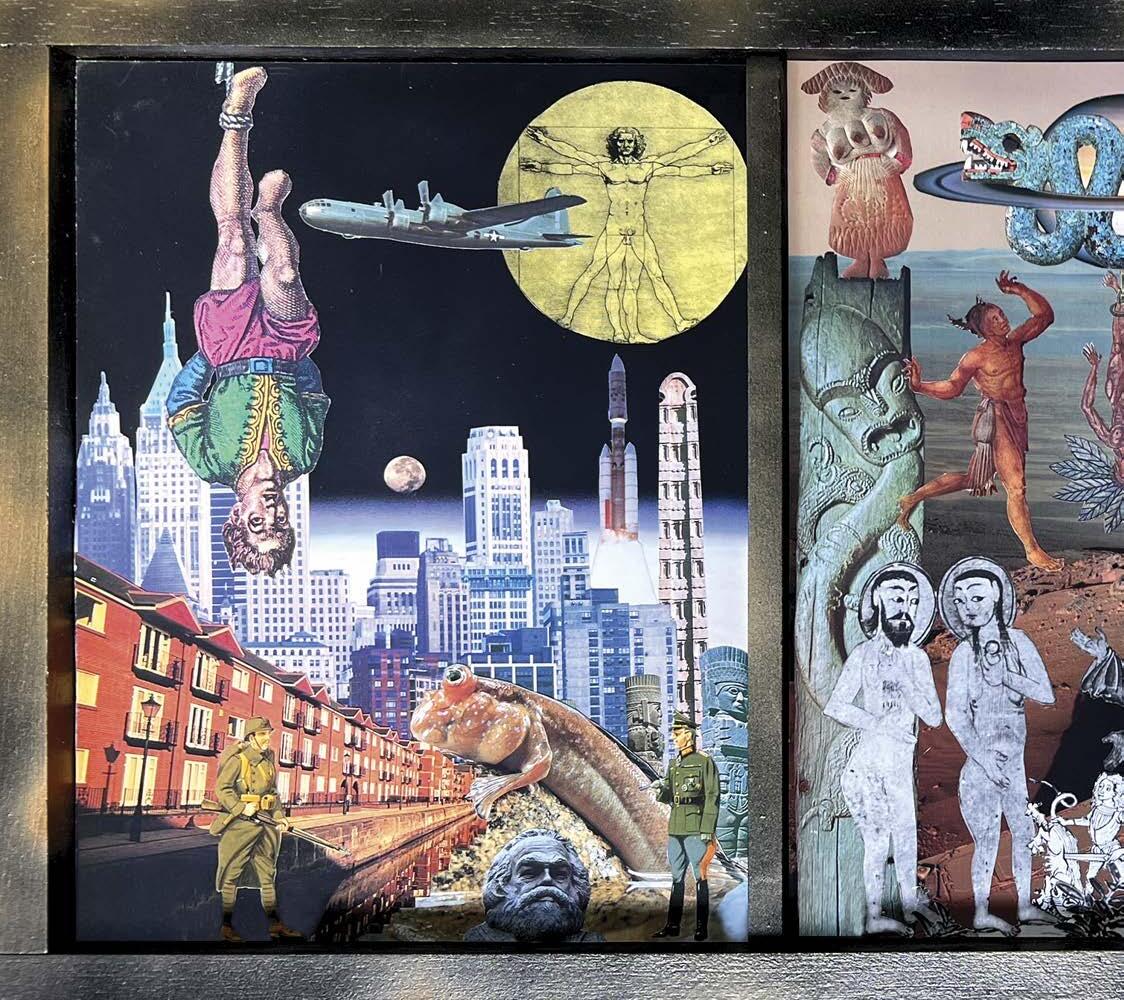

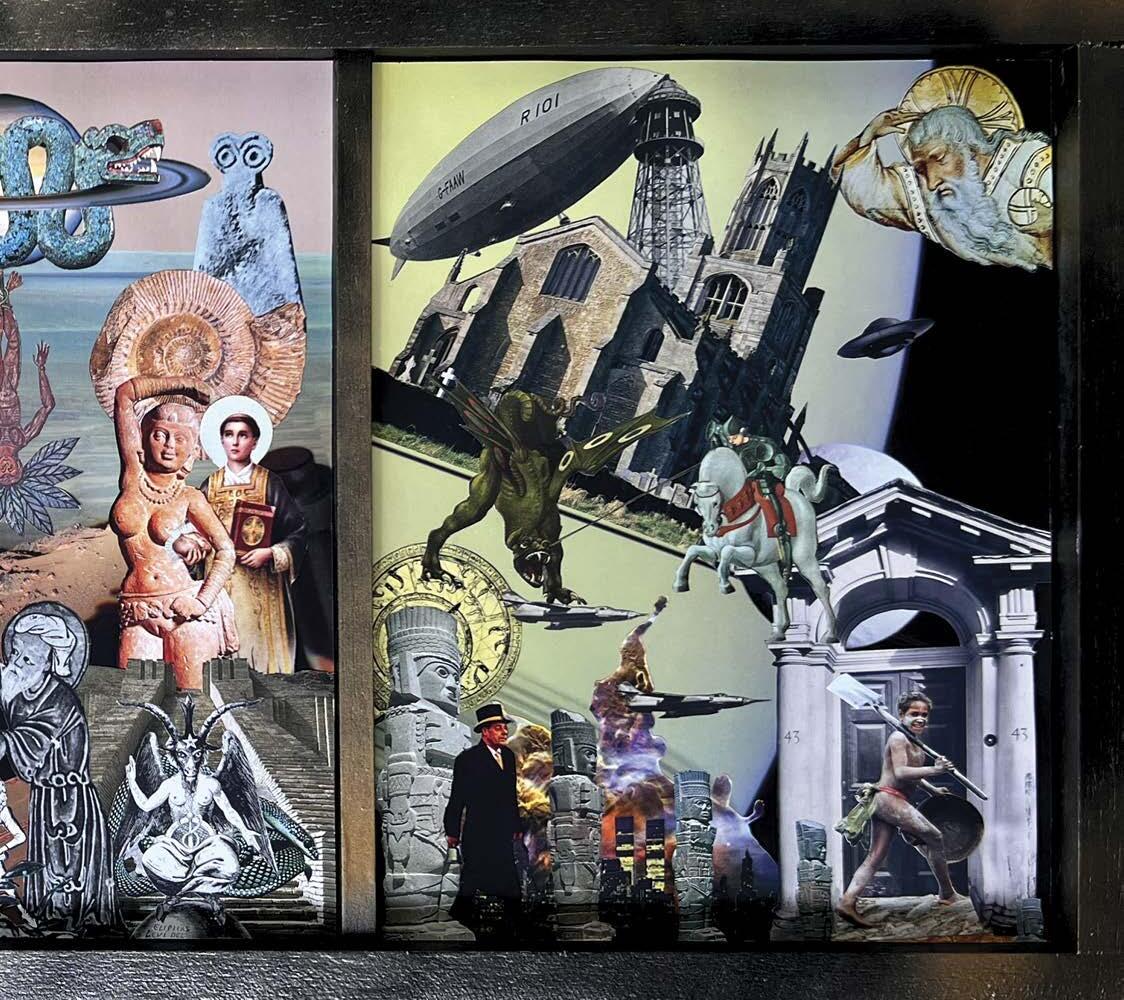

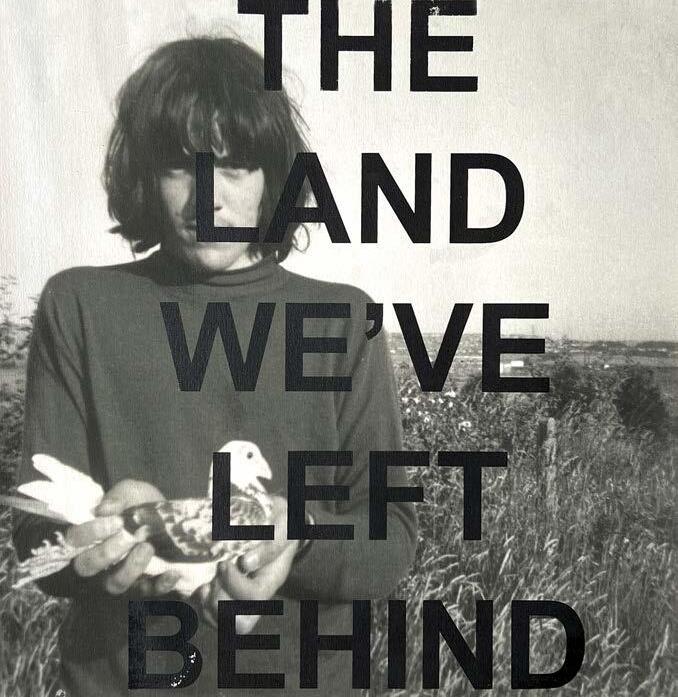

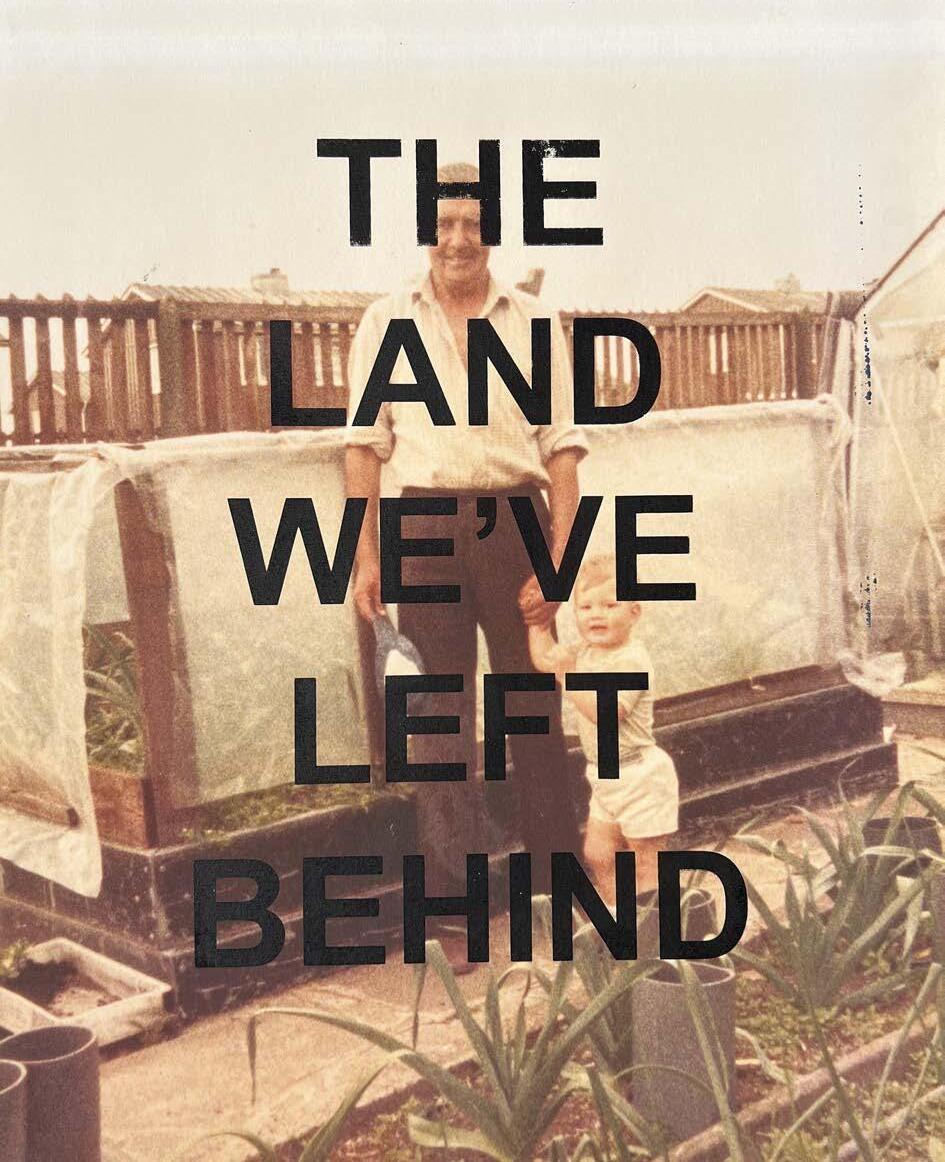

is book tells the stories of Washington both real and mythical, to celebrate 60 years of Washington as a New Town. e accompanying artworks are inspired by those stories.

Washington Fact, Fiction and Folklore is a project developed by a partnership between e Sunderland Indie, Washington Heritage Partnership and Arts Centre Washington.

Washington Heritage Partnership is an innovative collaboration between nine organisations (Sunderland City Council, Sunderland Culture, the North East Business Innovation Centre, National Trust Washington Old Hall, Arts Centre Washington, North East Land, Sea and Air Museum, 17Nineteen, Community Opportunities and Social Enterprise Acumen), with an aim of strengthening heritage and cultural networks and provision within Washington.

At inception, it was decided that some key programmes would be developed and funded by the partnership as major projects, and Washington: Fact, Fiction and Folklore is one of these. is publication represents a collection of the work undertaken within this project by artists, writers and historians.

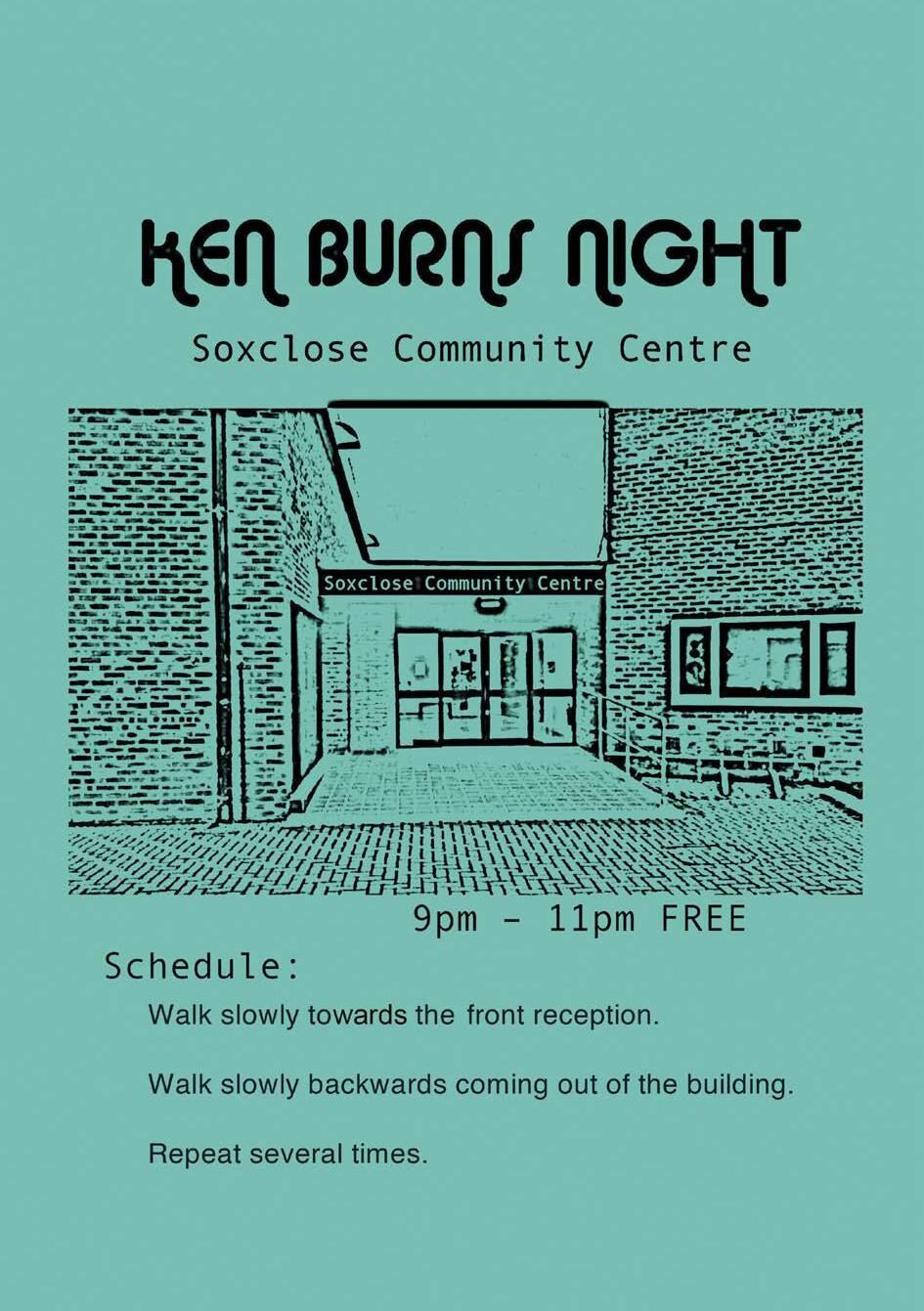

On 24th July 1964, the government had constituted Washington as a new town, and so 2024 saw commemorations of 60 years of this unique piece of urban planning. Conversations between e Sunderland Indie, Arts Centre Washington and the Partnership had highlighted an opportunity explore and celebrate some of the stories and themes that have formed a part of Washington’s history and identity both before and after the new town.

A starting point was a book written by Fred Hill, the man who saved the Old Hall for posterity when it was under threat of dilapidation. His “Washington: Fact, Fiction and Folklore” was a source of many stories and folk tales from which the artists of the Sunderland Indie and creative writers could draw. ere would be a process involved to ensure that there was a historical underpinning of all the art work that was eventually displayed in the Arts Centre from July – September 2024.

6 | Washington: Fact, Fiction and Folklore

A “Meet the Historians” event was held at Washington Old Hall in May 2023. Here a wide range of local history experts talked to creative writers and artists about key facets of Washington history, including the Washington Chemical Works, Mining and Union history, the development of the new town, German immigrants in the town during the First World War, tales of the Lambton family, and the life of Gertrude Bell. ese stories were among those that inspired pieces entered into a competition of creative and historic writing. These pieces were showcased at an event in October 2023, and in turn visual artists took their inspiration from the writing.

A preview exhibition was held at National Trust Washington Old Hall from April- June 2024, with great acclaim and then the exhibition moved to the Arts Centre in time for the Washington 60 celebrations. The exhibition at Arts Centre Washington also included work by members of the centre’s regular groups including Creative Age and Bright Lights You Artists Collective alongside other local artists. e creative writers were invited to return and some reprised excerpts of their work at the main celebration event on 20th July 2024, so their work reached a large and enthusiastic audience.

is project has been testament to the value of collaboration and sharing of artistic inspiration, as well as to Washington’s rich history and it has been a privilege and a delight to work with the whole team to help it reach so many people.

Jude Murphy Heritage and Culture Development Coordinator, Washington Heritage Partnership

Matthew Blyth Culture and Heritage Officer, Arts Centre Washington

I hope this section of the introduction is a waste of space because you know all about e Sunderland Indie already.

It is easier to list what e Sunderland Indie is not, than to try to describe such an amorphous, organic and flexible group of creatives. Let’s start with our intentions.

We are zero funded and will not accept grants or financial assistance. e reason for this is simple: financial assistance is always accompanied by the expectations of the money provider. Our art is the only determinate of what we do. We have no subscriptions entry fees, or charges of any kind. Anyone can join with us. (We have had members from all over the world, from China to the USA and Canada.) e only expectation we have is your generosity to teach us and share your skills, because that is how we all learn.

We experiment, develop and grow. Art is for learning and not for the marketplace. If the public want to buy our work, then great: we all have to eat. As an organisation any money you make is yours. ere are no exhibition fees nor commissions.

Our themes are non-party political, non-religious or any subdivision found within society. We have Christian, Muslim, Atheist, or anybody working with us, but differences are not recognized.

And lastly, to give a flavour of life with the Indie, here is a document issued about the lockdown experience.

e Sunderland Indie and learning to survive.

You see, it was already planned for sometime in the Autumn of 2020, probably October, because that is what e Sunderland Indie does, plan ahead. We were moving nicely towards the close of 2019 working on a few different themes, when we smacked straight into the worse year of our lives. Arts Centre Washington was going to be our venue and everything was going to plan, and then Covid 19 hit and life was turned upside down.

Seven artists, each one working towards a personal goal had been stopped in their tracks; we had to survive a pandemic, and then we had to survive the remedy to the pandemic, the lock-down.

My practice was based on “routine”. I had to make art, it was a compulsion, and it is probably the same for many artists, they have to make art, it’s a habit, a drug, as necessary to us as oxygen. I keep office hours at my studio, others cope in their own way, but routine is necessary for the times when the process dries up and we rely on turning up and slogging our way through another creative block.

Because travel was a problem during lock-down, I found it necessary to move my ‘studio’ to my dining table which meant working small, to build art from small units to assemble later. Hence the creation of ‘e Langdale Wall’ which was big enough to keep my mind occupied, and portable to be able to clear from the table if necessary.

DD had to clear her studio at the Frederick Street Gallery and turned her whole flat into a studio; living and painting in the same space, a seamless transition from bed sheets to painted canvas, from cooking up a meal to cooking up a storm.

JW was isolated from being able to analyse and respond to the world around him and became more retrospective and introspective. He drew from a wealth of past interactions and it showed in his development.

DT had the pressures of earning a living momentarily lifted and submerged himself in research and analysis. “Now I was able to take my time.”

And so, thank you to Matt, Jude, Laura, Sarah and the amazing teams from Art Centre Washington, e National Trust, Community Opportunities, Washington Heritage and the hundreds of people and well-wishers we have met during the last ten years plus.

And we are still growing.

Well art does, doesn’t it?

West Sunderland Indie

Fact, Fiction and Folklore

When I was a little girl, around three feet and three inches shorter than I am now, I lived in a small village that matched my small frame. e 1113 houses all sat neatly joined to one another to make the streets, and the streets all wove perfectly together to make the place. We only ever used one entrance and one exit to the village, so it felt as though everything, and therefore everyone, ran around in a perfect ring. If you were to visit a neighbour at No.65 Writhing Way, you were to pass numbers 1 to 84 of ForkedTongue Terrace, the corner shop, the post office, and well over half of the population of the circular community.

Everyone said good morning, even sometimes accidentally in the early afternoon, in that endearing way people do when life is so delightfully cohesive there's no need to check your watch. ere was a summer and a harvest fayre every year, where 1113 houses worth of villagers would spill onto the rounded road with traybakes of jam-roly-poly, gorgeously lumpy custard, and that working-class advantage of having nothing to prove. Not a single person made any profit at all year after year, as everyone was so busy hoping to line the pockets of their neighbours that things just always evened out. e summers felt long and the winters felt warm, glowing with grazed knees and frost-bitten fingertips and I thought I’d never forget and now can’t quite remember. It was never perfect,

whatever that means. e roads had unfilled troughs, the shifty ones among us tried the odd unlocked midnight door handle once or thrice, and a handful of parents told their children to take their mix- ups off the shop counter while they placed a bottle of the cheapest vodka in their place. But much like the unfilled potholes, these were simply the lumps and bumps of life as it expanded and contracted, a much more preferable narrative than life standing still altogether. e identical bricks that built every identical house were past terracotta, a scorched yet humbling shade of orange and clay. It was as if the entire place had been dipped into the sun, rotated and manoeuvred to make sure there were no un-golden places left where God’s fingertips had been.

Everything was so...so, that I was sure back then, had a tsunami made its way from the Northeastern coast towards Lambton, those perfectly ordinary houses would’ve stayed perfectly linked through it all, simply by brick and blitheness.

e village has been around since long before lumpy custard and bottom-shelf spirits, but I only got to see it from 1996. Although I can’t imagine much changed in that time, less a handful of replanted hollyhocks and labour jobs passed from grandfather to grandson and back again in the continuous fashion that life is.

ere was one thing, one part of the village that stuck with me as I grew those two feet and two inches. As I moved to the city, guessed my way around a utility bill, and started drinking gin instead of dilute juice. A tale told to glassy-eyed children with duvets pulled up to their chins. A whisper amongst raised, ale-fuelled voices in the pub, heard as clearly as an announcement on a busy platform and brushed off like a dandelion seed.

e story of an earl, a well, and a worm.

As the anecdote went, John Lambton, the first and apparently rebellious earl of County Durham, chose to go fishing instead of attending church one simple Sunday morning. Depending on who you ask and how drunk the storyteller is, it’s said an old man, or a witch, warned Lambton of the dangers of such a decision. en on that day, as the church service ended, he pulled something from the water, snake-like and nameless. Whenever my Mam got to describing the “beast” she would prolong her s’s and let them dance on her tongue like warm tea. She’d look directly into my glassy eyes and press her forefinger down the side of her face and she described the 9 holes on each side of its sssssalamander-like head. Some versions say the worm was no bigger than an average thumb if there is such a thing, and others that it was just over 3 feet, the size of three Dandelion and Burdock bottles stacked one on top of the other, or thereabouts. It’s said John Lambton exclaimed he had “catched the devil” before throwing it down into the pits of a lightless, nearby well. Growing up and fighting in many a war, as adulthood can commonly be, the earl easily forgot about the worm in the well, distracted instead by bloodshed, political leanings and perhaps the odd ale. But as all forgotten things do, the worm grew in the absence of observation, as a negative thought does in the back of the mind - writhing and persistent. e worm, now the size of a dragon, broke free of the well and terrorised the local village, eating sheep, draining cows of their milk, and swallowing small children like bonbons, eventually coiling itself around Penshaw Hill ten times as though a crown on the head of a king. e story continued like this: coiling, chaos, cows milk.

After a while, news of the happenings reached Lambton, and he returned to find his father’s land destitute and demolished. It’s said he sought the advice of a witch, who informed him the worm could be killed, but so to must the first living thing Lambton saw after the slaying, otherwise 9 generations of his family would be cursed, and not die in their beds. Lambton fought the beast, wearing armour of spikes and sanguine, leaving the slain pieces of the onceworm to float away down the River Wear to a place less Lambton than there. In his flurry of pride and excitement, Lambton’s father ran toward his son instead of realising the hound they intended to kill, and so the curse took Lambtons for many years to follow; some by drowning, some by defenselessness, but none in their beds.

I remember, much less tired than before the bedtime story started, being glad the worm had gotten so big. Too big to slither through the gap beneath my bedroom door then around my credulous neck, and constrict until I slipped into a lightless well of my own.

e thing about bedtime stories is they more often than not get left behind as you grow older. ey stay under that baby pink duvet, in the pits of the potholes of your childhood street, and in the smallest most forgettable part of your mind, until you retell them to your own children. But that’s why I’m here, writing about this small girl in a small village filled with seemingly tall tales. Because the dandelion seed didn’t catch the wind and move onto another shoulder far from mine. at story stayed with me. At the very back corner of the wardrobe’s top shelf, underneath the pile of miscellaneous “I’ll-get-round-to-themsoon” letters and old birthday cards. I’ve lived years of life since I last heard the story of the long and lethal Lambton worm, and my duvet is more of a dusty grey now, in the natural way adulthood makes you prefer more muted colours. Years passed, I got a writing degree, and I fell in and out of love, I moved to the city, but it felt as though I could be the only grown-up in the entire world who thought there was truth to fairy tales... and monsters.

Reliving the story of the earl, the well, and the worm since growing those three feet and three inches, since moving away and moving back, since having loved and lost, makes me wonder more than ever: was the beast ever truly slain at all? I’ve felt it tugging at my trouser legs and crawling across my neck in job interviews, not sure whether it was daring me to be better or trying to convince me I couldn’t. It’s lived inside my mouth when reading aloud to an audience, forcing me to trip over my words and then my own two feet, but been a crutch in awkward silences I’ve felt I needed to fill, making me realise it’s not my job to make everyone else's easier. It's sssssniggered over my shoulder as I re-read my throbbing inbox of job rejections, but conssssstricted around my fingertips as I still always applied for one more. Its hot breath fuelled my car engine as I took hours instead of minutes to break up with boyfriends I knew were bad for me in aleatory car parks, whissssspering from the exhaust that the pain was going to be worth it.

I’ve tasted its hissing from the sausage sandwiches my parents make me and my boyfriend on sssssslow Sunday mornings, the kind where we popped over for one thing on Saturday afternoon but had too much of the world to put to rights not to stay the night. e kind where lightly-salted butter runs down your fingers like blood or honey, or like pieces of a slain beast floating innocently away down the River Wear.

I’ve smelled it so strongly in my Mam’s stories of my biological Dad. How he would come home reeking of perfume she would only keep for best, a perfume that filled up the entirety of their small bathroom as the heat from his frantic shower danced with the oils in a marriage more perfect than their own. How after the fifth insincerityscented bathroom, he finally hit her for the first time. I say finally as if it was something she was waiting for, but there’s a difference between something you want and something you anticipate. But the same monster that carried his fist, lives inside of my Mam and gave her the courage to float far, far away from the very real snake she slept beside.

Even far away from Lambton, when I lived in New York City for the best part of four months, it felt like it followed me. I watched it swirl

around in the bottle of the cheapest whiskey that the homeless man on 43rd Street could acquire; watched him drink more and notice less as the beast got closer and closer to his lips, begging to be swallowed. But I think back now to that man on 43rd Street, and I had forgotten to remember his smile while he drank, as if the only thing he truly wanted was to be taken far far away from here, and the beast in the bottle was obliging. I realised that age and life and everything in between had given me a new telling of this oldwives tale I heard at my childhood bedside, wondering the wrath I would feel being thrown into a dark well, and realising to not die in your bed is to die out in the world where there is opportunity and lumpy custard and life to be lived, and that that death now doesn’t seem much like a curse at all.

I thought getting older and travelling farther would leave the fable tucked tightly under that baby pink duvet. But that’s what I’ve learned over these enchanting and ensnaring years. at bedtime story, that ‘make-believe’ monster, that, thing. e snake-like monster said to be forgotten and unseen has uncoiled itself from Penshaw Hill and lives on in every single one of us, every day. Every anxious moment, every happy tear, every infidelity, every rejection, every second of doubt and moment of bravery, between the lust and the loss and the love and the life, it’s there, happily hissing between hope and hopelessness, so around and around we go.

If you ask me, monsters don’t live under the bed, in the retelling of tales from beaten-up bar stools, or between the pleasing rhymes and watercolours of a children’s storybook. ey live inside your jumper sleeves, at the end of the aisle, under your skin and at the tip of your tongue. I’ve read enough books and lived just enough of life to know man and monster aren’t that different. I’ve felt the beast pull me from the deepest and darkest of wells, constricting around me when I needed it most, and I’ve seen humans do such terrible things I wished they were just a page of a bedtime story.

Whist! Lads, haad yor gobs, an’ aa’ll tell ya aall an aaful story, the only real differences between man and monster, are two feet, and a sssssmile.

Welcome to all.

But especially those tuning in to my channel for the first time.

Hope you newbies have come with an open mind and are prepared to hear lesser known, maybe even previously unknown, historical incidents that just might be of particular interest to people who want to believe in all manner of things.

Believe in what, I hear you ask.

Have a listen and you’ll see what I mean.

My regular listeners will know what that means.

Today I am exploring two separate, but definitely linked, events.

Okay.

You know the town of Washington, where Washington Old Hall is situated. Where, in case you didn’t know, the ancestors of the USA’s first president George Washington did indeed reside.

First, let me introduce Robert, a real local history buff.

Robert ‘s not his real name of course but that

seemed an appropriate alias since it’s Robert Washington (from de Wessynton) then lord of the manor house that we’re talking about.

It’s 1304 when King Edward and his ‘Travelling Kingdom’ paid a visit to the Hall in September of that year.

Robert and his wife Joan - de Strickland of Sizergh Castle, Cumbria – were over the moon at having the King honour them with a visit.

Sidebar folks: Edward was returning from Scotland, since things seemed to have calmed down a bit up there, to his base in York.

After a rest there, he planned on continuing south, spending Christmas in Lincoln then returning to London in the new year.

Whew. Anyway.

Yes, Robert and Joan were honoured but they also breathed a sigh of relief that only a third of his royal court were having ‘prandium’...for those not fluent in Middle English that’s lunch...with them.

It wasn’t just the expense, which would have been astronomical, but their manor house, albeit one of the grandest in the region, would not have been able to accommodate the entire court.

You see, the cost to feed the entire court would have been out of this world. What with all the courses featuring swan, peacock, wild boar, copious veg, sweet tarts and expensive stuff like cheese, butter

Oh and all washed down with mead and beer, of course.

Yes, one third continued on to York while the other third accompanied Edward’s second wife Margaret to the coast for their prandium.

Apparently Margaret preferred Tynemouth.

Again... anyway. Back to our modern day Robert.

ere are several pubs, tea rooms not far from the entrance to e Old Hall, now a ruin by the way, where our Robert, retired, liked to while away the hours, talking local history with other, mainly retired, buffs of all genders.

One day, a new face asked permission to share his table (he was outside on one of those picnic type tables, enjoying a solitary, mid-afternoon pint) and it didn’t take long for them to delve into e Old Hall’s history.

e visit of King Edward in 1304 came up and the stranger asked our Robert if he knew the story of the Ivory Bangle Lady.

He said he did not, so the stranger proceeded to fill him in.

At first, Robert (the lord) was concerned about language as a barrier: no one in his immediate surroundings spoke French, the language of royalty.

Bit of Latin might have come in handy but issues with the Bishop of Durham made inviting Anthony Bek out of the question.

His concerns, though, were put at ease when the courier of the King visited the day before Edward’s arrival. A necessary visit of course to ensure all necessary preparations for the king’s visit were made.

e courier informed Robert that the King always travelled with an advisor who spoke many languages. French, Latin as well as the English dialect of those residing ‘North of the River Humber’.

Yeah, nobody said ‘North East’ back then.

is particular advisor was called e Ivory Bangle Lady because her earrings, bangles and pendants were all made of ivory.

And, the courier warned, she was not to be made fun of or treated differently once seen that the colour of her skin was dark and her mannerisms foreign.

No one even knew where she was from originally and if King Edward himself knew he did not share that information.

One day she just seemed to appear, out of the blue, at Edward’s side.

Back to the lunch time feast.

ere she was, our Ivory Bangle Lady, not sitting, not eating, just wandering around. Suddenly she takes a keen interest in the hosts, Robert and Joan, sitting alongside King Edward at the top table.

She studies them for a moment then in heavily accented Middle English (think Chaucer) tells them the following:

“You must change your coat of arms. e one now is your past. e new one of white and red, with bars and mullets is your future. A future you will not see but know it will contain a link with greatness.”

Our Robert was intrigued by the stranger’s tale and shortly after dug a little deeper. He was aware that that shortly after Edward’s visit, the Washington’s had changed their coat of arms. e bars and mullets were seen as a link to the stars and stripes of the American flag.

(Yes, the white and red fitted but what about the blue?)

Anyway, as for e Ivory Bangle Lady, his searches could only find a reference to the skeletal remains.... on display in York Museum, I might add.... of a 4th century lady thought to be of North African descent but born in Roman Britain.

at is when Robert contacted yours truly.

Sidebar....he wasn’t a listener at that time but did know someone who was.

Okay.

Now it’s time to bring in event number two.

And I won’t have to spell out the link for you, dear listeners.

Okay. I too was intrigued.

Last sidebar, for the newbies.

My regular listeners know that I am black American foreign exchange student studying at a Uni here in the North East.

Yes. I had been to e Old Hall before and knew a bit of it’s history. As an American I was also aware of DAR’s (that’s Daughters of the American Revolution) support of e Old Hall.

Okay. Now the last sidebar...I promise.

Update on DAR:

“For decades, the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution has worked to identify African Americans, Native Americans and individuals of mixed heritage who supported the struggle for independence during the American Revolution. We welcome the descendants of these men and women into our membership within our National Society.”

Quite a refreshing change from the bad old days when, in my grandmother’s time, only white women were allowed to join.

Anyway.

I just had to go back to e Old Hall after hearing Robert’s story. Don’t ask me why but for reasons I couldn’t explain a fire was lit.

Although the bangle lady’s bones were in York, something was waiting for me in e Old Hall.

Someone was waiting for me.

So.... I became quite the visitor.

Even met our Robert a couple of times, sharing a drink (I was coffee) at his favourite spot across from the entrance.

He even understood my quest.

And one day just before the gardens were to close, I saw her.

I was sitting alone on a semi-secluded bench, parked neatly between shrubs and e Ivory Bangle Lady seemed to appear out of nowhere.

She sat down next to me and began to speak very quickly in heavily accented, modern English.

“Welcome daughter of e Muurs. I am one of many reincarnations of the First People. We are their Children who navigate the world bringing Light to all who listen.”

She smiled, then continued.

“George Washington did not have children but his second wife Martha did by her first husband. Her great-grand daughter, Maria Carter Syphax, was born enslaved, 1803. Look at the descendants from that line and learn what part you may play.”

And, poof.... she was gone.

I still feel I dreamt it all... BUT.... I’m doing the research any way. And, of course, will keep you, my loyal followers, updated.

I’ll leave you hanging there. More next time.

Washington: Fact, Fiction and Folklore

“I am wrath I am vengeance I am the ire in fire

I am John Lambton’s ruin! and he isss a liar!”

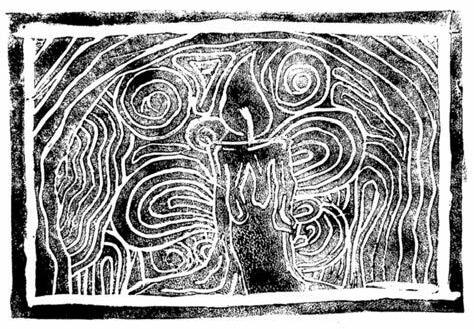

e Lambton Wyrm

John Lambton

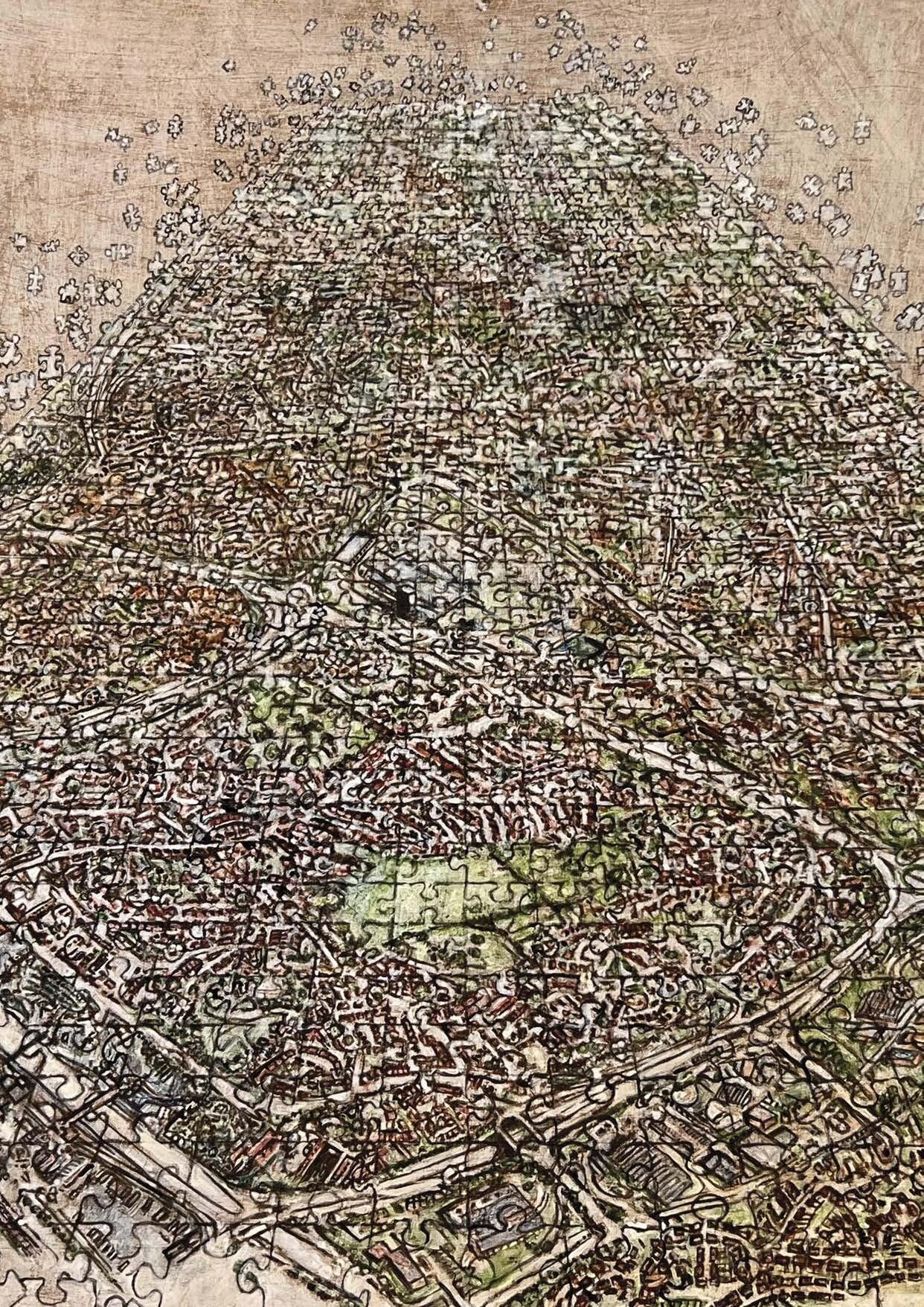

Not far from the meandering River Wear there is a huge mound of earth blanketed in green. Here is Wyrm Hill in Fatfield, an old village in Washington new town.

If you look carefully there are furrows spiralling their way round to the summit. ese marks were carved into the earth by the Legendary Lambton Worm when it made its home on the hill. It was so monstrous it wrapped itself seven times around the slopes and terrorised nearby villages; eating sheep, poisoning the land and snatching small children.

is tale has been told many times in story and song. ey tell of how it appeared and plagued the land and was then eventually defeated by a knight.

at of course, is the official story but I am here to tell you the truth gleaned from an ancient journal I found buried at the foot of the hill.

Bound in dragonhide, it is festooned with feathered scorch-marks, the tell-tale sign of dragonfire. Its toothy clasp is half-melted and can be very tricky to open without slicing open your

fingers. If you persist you are rewarded with a medieval manuscript written in the glittering gold of dragon blood. e pages are illustrated with intricate drawings that flow in and out of the words as if they were alive.

Here is the lost art of the serpentine scribe, the literate monster who tells his side of the story.

is is the true telling of the tale by the Wyrm.

I iss Wyrm

ere I am, minding my own biznesss, flipping and flopping around in the river when He catches me, my lifelong Nemesisss.

Excuses the essess, ‘tis a cross I have to bear (if I woss a Christ Man that iss) but it isss part of my natural hisss. For I am part ssserpent, part eel, part dragon and I am all proud! Some say I am a monssster, but one mussst define monsster. Perhapss it isss a need you humansss have to demonisse my kind when the real monssster is you.

Crussadess my asssp! One must remember human beings, that you write hissstory from a biasssed point of view ssso you can paint yourssselves in a good light. After all, necesssity iss the mother of invention and as a race you have invented many liesss throughout your monsstrouss history.

To be thrown away like a piece of rubbissh wass

and degrading, it was time for vengeance.

Well this is not your history, thiss iss my hisstory.

Ssso there I am frolicking in the water, barely the length of one of your little fingerss when John Lambton (boo hiss!) traps me unawares.

He isss all the ssscaress.

He’sss no sssaint himsself you know, he’ss misssed church to go on a little fisshing trip.

At first he doesn’t get a bite but soon after the sservice endss (or sso they sssay) he hookss me and ssayss “I have catched the devil”.

e downright cheek of it, mistaking my eellike body and serpentine head for the devil, I’m much too handsome to be mistaken for Sssatan!

To add inssult to injury he throwsss me down a well. I am livid! I am fuming!

What he doesn’t realisse is that I tend to hold a grudge, I will not let it lie. You shall feel my wrath John Lambton! You will sssee the thunder in my fury!

Ssso what I haven’t mentioned yet was that Johnny boy wass warned about thiss. Ssome owd fella told him that no good will come from misssing church for such frivolitiess asss fisshing. ere alwayss hasss to be some party pooper to rain on people’ss parade doessn’t there?

This owd fella turns up again to repeat his warning after he’d hoyed me down the well. It wass mosst undignified, did I tell you that I sought vengeance for this humiliation? Would you not do the same if you were in my position?

To be thrown away like a piece of rubbissh wass demeaning and degrading, it was time for vengeance.

I hauled mysself up out of that odious prisson, bit by bit, inch by inch. It took me forty dayss and nightss to reach the ssurface but I got there through true grit and determination and a burning dessire for revenge.

Ssso when I got out I wass a bit hungry, well a bit iss an understatement, I wass ssstarved! It jussst so happened that a tassty morsssel came a wandering by. Who am I to question asss I snaffled the little lamb with a tear in my eye. Sssorry not sssorry.

Sso time passsed and I grew in ssize and sstature. From a worm to a ssnake to an eeley anaconda. e locals began to fear me asss I sslid over yonder.

I wrapped myssself seven times around a mound in old Fatfield town and I ate handsome mealsss with local ssheep wasshed down with a few gallonss of cow’ss milk.

Now before you judge me, remember thiss.

Are you not human? Have you not ever eaten a lamb sshank or a chicken ssarnie. If you are vegetarian I would understand but mosst of you eat at Maccydeess and Nandoss so any comments about my food preferencess would be underhand.

Now theresss alsso a ssscurrilouss rumour that I sssnatched away sssmall children. at’sss jussst fake newsss and anti-ssserpent propaganda! I will not be persssecuted by othersss becaussse of my appearance and lack of limbsss!

During thessse timesss of plenty that rapssscalion John Lambton gallivanted off to fight the Crusssadesss. Persssonally I never agreed to ssspreading of the word of the lord through war but who am I to judge, I’m jussst a sssnake. He returned after ssseven yearsss and that’sss when my troublesss began.

Of courssse he’d got wind of my sssheep sssnackage and the fact that I’d popped over to hisss dad’sss houssse at Lambton Cassstle and asssked very nicely if I could have a treat of a filled trough of cowsss milk. e old man obliged and it was a nice life making sure that I drank a trough of milk a day.

e villagersss weren’t happy with thisss and they tried to kill me, how rude!

I had to defend mysself didn’t I? It was a bit sssad that sssome of them perissshed but that’sss life isssn’t it?

en they sssent a bunch of knightsss to hurt me which persssonally I think is disgusssting. I can’t abide men wrapped in tin cannnsss trying to ssstab and ssslasssh me ssso they got their jussst dessserts of courssse.

Whenever I get mad, which isss often when you humansss are hasssling me, I will uproot the treesss by coiling my big tail around them and using them to sssweep away the pesssky knights. ey call it devassstation, I call it being asssertive.

Ssso that John Lambton comesss back from his ssself-righteousss Crusssade to persssecute me, another innocent! I heard through the grapevine that he’d had some advice from that owd fella before he came to fight me.

He was told to cover hisss armour in sssharp ssspearheads, ouch, that’s gonna sssmart! He was also advisssed to fight me in the River Wear ssso that when he cut me the piecesss of my body would wasssh away down the river. I mean that’sss nasssty, and they call me the villain of thisss story!

Lassst of all they told him that once he’d killed me his family would be cursssed for nine generationssss and would not die in their beddds.

e only way to lift that curssse would be to kill the firssst living thing that he ssseeesss to avoid the blight on his family. Ssso he sssaysss to hisss father that he will ssssound hisss hunting

horn three timesss. On thissss signal his old man was told to releassse his favourite hound so that it would run to him. He would kill the dog and avoid the curssse. How cruel is that? Honestsssly what a palava!

Well itsss a good job I heard about thisss becaussse I decided to ignore sssuch nonsense. Oh how wrong I wasss to do ssso. You may have heard that he killed me with his ssstupid plan but let me tell you what really happened.

So there I wasss once again wrapped around a big rock in the river, enjoying a nap after my daily trough of milk, courtesy of John Lambton’s old father. A couple of foolisssh knightsss had tried to prove their bravery the day before and I wallopedthem with a couple of treesss, remember it wasn’t my bad, I was just sssurviving!

So along comes Johnny boy in hissss high fallutin’ ssspear-ssstudded armour and he attacks me, a defencelessss creature! In truth, when I wrapped myssself around him it was like getting a few paper cutsss. It was harsssh yes but not lifethreatening. ey sssay he cut me into piecesss and they were ssswept down the river but I call that bull! e truth isss I defeated him and he was too assshamed to admit it! e ssscoundrel slicesss off the tip of my tail and holdsss it up to prove I was dead.

Meanwhile I managed to ssswim away to the sssafety of my sssecret hideaway. John sssounded the horn with three blasssts and the owd fella was ssso excited to hear of my untimely demise that he forgot to releassse the hound and ran forward to greet his ssson.

Now Johnny boy could not bear to kill hisss own father ssso they ssslaughtered the poor dog inssstead. Well, I wasssnt very happy about thisss so I decided that they did not dessserve to dodge the curssse!

I made sure that Robert Lambton, Johnnyboy’ssss progeny, had a boating accident at Newrig. It was I who killed hisss dessscendent, Sir William Lambton, at Marston Moor, and yesss it was me who ensssured that William Lambton, his great grandssson, died in battle at Wakefield.

Ssso that nine generationsss curssse, thing, I’m afraid I took my eye off the ball for a bit but... I reminded them when it rumbled through the ages and they thought they were sssafe. I ensssured that Sssir Henry Lambton, he of the ninth generation, died in hisss carriage crossssing Lambton Bridge on Tuesssday the 26th of June 1761. You’ve got to keep them on their toesss haven’t you?

Yesss, the rumoursss of my death were greatly exaggerated. I am a sssurvivor. I am Wyrm and I live! ey even wrote a sssong about me!

“Whissst! ladsss, haad yor gobsss an’ aa’ll tell ye aall an aaful story, a’ll tel ye ‘boot the worm”

e cheeky buggersss, if only they knew I wasss ssstill around, hiding and biding my time. Ah well, I’ll have a little ssslither up the hill to eat the sssheep and wasssh them down with the milk of a dozen cowsss. I’ll be back to finisssh the ssstory. I’ve heard tell that sssomebody sssomewhere is poking around in my businesss back at Wyrm Hill in Lambton. I ssshall have to keep a keen eye out for thisss interloper.

e story ended there. e final words glittered in the moonlight, brighter than the rest of the writing. ey looked like they had been freshly written. Surely not! I looked around nervously, here I was at the bottom of Wyrm Hill and the final words echoed in my head “sssomebody sssomewhere is poking around in my businesss...”

I turned as I heard a whisper in the wind in the dark of the night. A strange hissing noise could be heard approaching from beneath me. e ground began to tremble, to rumble and my mind became riddled with regret as I dug at the soil in a futile attempt to put the book back. But it was too late, as realisation dawned the legendary Wyrm was still alive and out for blood.

e ground erupted in a shower of scales and soil and darkness descended.

Andrea Lynn Henderson

“So what’s your chances of shedding a new light on Gertrude Bell then?” my friend Nina is saying over the phone.

“I’m not sure. I need to know more about her. Not just the historical facts, but as a real person.”

“A tad difficult don’t you think? She’s been dead since 1926!”

“I know it’s not going to be easy. ere are books written about her life, and Newcastle University’s ‘Gertrude Bell Archive’ is right on my doorstep. ey’ve got her letters and photographs stored in the Robinson Library which provide detailed accounts of her experiences.”

“Would the 2015 film ‘Queen of the Desert’ help? Werner Herzog wrote and directed that movie. Nicole Kidman played Gertrude. Mind you, it flopped at the box office.”

“Actually, I was thinking about taking a look at the ‘Letters From Baghdad’ documentary that Tilda Swinton produced in 2016. I’ve heard she portrayed Gertrude really well.”

“Well, there’s a good variety of documented evidence out there. I’m sure you’ll find what you’re looking for. How long have you got?”

“Two weeks.”

“at’s not very long.”

“Hopefully it’ll be all I need. It’s all about authenticity, so I know the character I’m playing.”

“at’s why you’re good at acting,” Nina says fondly, “your talents are too good to be tucked away in local theatre. It’s good you’re living in Washington where Gertrude was born, though I think it’s funny that she was President George Washington’s neighbour.”

“Ancestral neighbour.” I laugh.

“You’ve got a similar connection. You’re practically a neighbour too.” “anks Nina,” I feel myself welling up, “I’ll catch you later then.” “Sure, anytime. Enjoy your search.”

“anks, bye.”

Nina’s right. It’s my dream to be a professional actress. As an ex-professional dancer, at thirtyeight, I feel acting is the way forward and I’m honing my craft. So when the local amateur theatre committee said they wanted to include one-man shows in their new programme, I jumped at the chance. I pitched my idea to run the life and loves of Gertrude Bell, and they’ve

agreed. Now I want to know why and how Gertrude came to love and embrace the Middle East, a culture so far removed from her birth in Washington New Hall, County Durham, England, 14 July 1868.

Driving back to my flat from my weekly food shop, I’m wondering how Gertrude coped with travel. I’ve read somewhere on google that she used to have an entourage that would carry her essentials, including a bed, and a bath! Across the deserts and archaeological sites of the Middle East? Really?

I’ve also learned that Gertrude had travelled extensively, including two world trips between 1899 to 1904, before she found her true passion for archaeological digs. Her first ‘dig’ being in Greece with her family back in 1899.

I can’t help comparing Gertrude’s life and times with mine. Here I am, Rachel Harvey, in 2023, retrieving the groceries from my car. How can she live without the home comforts of a car, mobile phone, online banking, fridge and a TV? And in foreign countries so far removed from her charmed and privileged upbringing?

I’ve discovered Gertrude’s mother died when she was two years old after giving birth to her brother, not long after they moved to Redcar. Fortunately, her new step-mother and Gertrude became very close. It was Florence who encouraged Gertrude to read ‘Alice In Wonderland’ and ‘Ali Ba Ba’. Did Gertrude daydream about the magic and allure of Persia way back then? One of her letters from Persia, stored in the Newcastle University Archive quotes, “Isn’t it charmingly like the Arabian Nights! But that is the charm of it all and it had none of it changed.”

Myself, I’ve always read fiction, though I’m currently reading a lot on psychology, ever since I started researching the characters I play onstage. I’m drawn to the psychological aspects of each character, and I’m discovering Gertrude Bell is one amazing woman.

“So how’s the research going?” Nina’s being her usual bubbly self. We keep in touch via weekly phone calls and WhatsApp. She lives in Penrith, Cumbria, where we met. We visit each other as often as we can.

“Well she was only born into one of the richest families in England in her time!”

“Wow!”

“She was privileged and put it to good use. She was the first woman to gain a First Class Honours in Modern History at Oxford University; she was a mountaineer and explorer, one of the mountains in the Swizz Alps is named after her; she travelled solo in unchartered Arabian desert; and was the only female employed in the Middle East by British Intelligence during the First World War.”

“Omg! Really?”

“Yes. She was instrumental in creating the borders of the new Iraq and helped King Faisal I become king of the new Iraq.”

How come she got involved in the Middle East?”

“Visiting her uncle, Sir Frank Lascelles. He was British Ambassador in Tehran, now part of Iran, in 1892. She fell in love with the Middle East, learned to speak Persian and Arabic, and the rest, as they say, is history. What I want to know is why we’ve heard of Lawrence of Arabia and not Gertrude Bell? ere’s photographs to prove she was there with Lawrence and Winston Churchill in 1921.”

“I don’t know,” Nina ponders, “because she was a woman?”

“She wasn’t very popular with women. She cofounded the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League. Based on the mindset of her peers when she studied at Oxford, I reckon she didn’t think women had the skill and intelligence to run a business or a country. She much preferred the company of men.”

“Well I’m glad we’ve proven her wrong today. e suffragette movement was a watershed for women. ey secured our vote.”

“I agree. But she did know about power and politics. Do you know her father was Hartlepool’s Liberal Member of Parliament? Gertrude grew up headstrong. She didn’t give a jot what others thought.”

“Obviously! She wasn’t exactly the typical British woman of her day. What else have you found out about her?”

“She never took ‘no’ for an answer. She was determined to live her life to the full, seized every opportunity and thrived in the challenges that came her way.”

“Is that how she became a pioneer?”

“Must be. Gertrude never appeared to be deterred by anything. I’ve got to go, someone’s ringing the doorbell. I think my book’s arrived from Amazon.”

“Okay, speak later, bye.”

My psychology book has arrived. I’m hoping to glean more understanding about what makes Gertrude tick so I can unravel her story as befits a pioneer of her magnitude.

I’ve learned more about Gertrude’s life and loves. Her first love was Henry Cadogan, a member of the foreign service she met while visiting Iran in 1892 when she was twentyfour. Her father had insisted Henry didn’t have the means nor business acumen to continue the legacy of the family’s business empire. Though devastated, Gertrude ended their relationship.

I’m wondering if her thirst for adventure was to forget about Henry. She discovered her love for mountain climbing in 1897 while on holiday with the family in France and had scaled mountains from 1899 to 1904. ankfully there’s a photograph taken in 1899 of her wearing

breeches and not skirts for her mountaineering jaunts!

Since 1899, Gertrude had returned to the Middle East many times for well over a decade, focusing her energy into what she loved the most, archaeology. She preferred Egyptian, Roman, Greek, Byzantine art, architecture, thus forging her desire for antiquities.

Her fascination for archaeology grew from her travels from Jerusalem, through the Syrian desert to Asia Minor where she explored the Binbirkilise region. From there, Gertrude continued alone with her guides to explore ruins in Mesopotamia on her way to the castle of Ukhaidir near Baghdad. In March 1909, she documented and sketched the huge structure in detail, forever immortalising it.

Travelling to various archaeological sites helped Gertrude navigate the Middle East where she learned the culture and politics of Mesopotamia. Once there, she spent most of her time painfully recording the excavations, documenting photographs, drawings, plans and descriptions.

Sharing her passion of the Arab world and it’s people she’d grown to love, she published her writings in several books, travelogues, archaeological journals, periodicals and academic papers detailing her findings and experiences, which helped secure her reputation as a writer and scholar.

“Did you get anything out of the book you received from Amazon?” Nina’s asking on the phone.

“Yes I did. It’s about understanding perception. I get the feeling Gertrude wanted to be taken seriously in her work and as a woman. I believe she felt the need to satisfy her sense of self, passions and vision, in both the British and the Arab worlds.”

“at’s a tough act. Are you saying she was misunderstood?” I could hug Nina.

“Possibly. But the way she used her skill and acumen to rally the Arabs to fight against the Turks during the First World War was incredible. Lawrence devised the new strategy and Gertrude implemented it. Knowing business and politics, she created her contacts and relations with the tribes by only speaking to those in charge, she really knew her stuff. I think she believed in whatever she put her mind to and never looked back.”

“Why do you think she never looked back?”

“Stepping on new terrain is definitely not for the faint-hearted!”

“at’s for sure.”

“I also think, in her own way, she did something for women’s rights.”

“What do you mean?”

“She was a pioneer,” I pause, “she must have broken the mold of what society perceived women could accomplish.”

“Equal rights for women are still an issue in certain areas you know.”

“I know, but Gertrude knew the Middle East inside out. at’s why British Intelligence called her into service in 1915, after her stint improving administration for missing and wounded soldiers in Britain and France on behalf of the Red Cross. She was assigned to Basra to work alongside Lawrence to improve communications between departments; interpret reports from Central Arabia; and gather detailed information documenting Arab tribes in parts of the Middle East. She received her CBE for her efforts in Baghdad in 1917.”

“at’s impressive.”

“She loved Britain and the Ottoman Empire but was torn between the two. ey were enemies. Gertrude wanted to make sure that the best was done for the new Iraq and its people by creating

an independent Arab Government. at’s why she got involved. e people of Iraq called her ‘khatun’ you know. at means ‘queen’ in Persian and ‘respected lady’ in Arabic.”

“Nice. So what happened after the war? Did she stay or return to England?”

“She stayed. She established the National Museum of Iraq and created a new law to preserve their artefacts in 1922. It opened in June 1926 then she died a month later from an overdose of sleeping pills on 12 July 1926, two days before her 58th birthday. I think she died from disillusionment, despair, depression, and a broken heart.”

“O-kay. What makes you say that?”

“She was never the same after the second love of her life, Major Charles Doughty-Wylie, died in Gallipoli in April 1915. She was still sending Dick letters after he’d died; by snail mail. She didn’t know until she’d returned to England for a family visit. She became really depressed.”

“Oh. Were they married?”

“No, He was already married.” “Ah.”

“She must’ve really loved him,” we both say in unison. “So have you finished your research now?”

“Yes. Posthumously Gertrude was recognised amongst her peers as an English writer, traveller and government official who played an important role in establishing the country of Iraq. Now I’ve looked into her life and loves I can see she did make a difference. And with far-reaching perspectives, she could see what others couldn’t see. I believe Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell CBE was a woman ahead of her time.”

It’s difficult to say how excited I was when I was told we were going on a trip to Washington Old Hall. Difficult because my tears and anguish meant I was largely unable to express anything coherent for a long time. Did the teachers know how short the journey was to Flamingoland or Lighwater Valley? I’d even go to Forbidden Corner at a push. Might even make my own packed lunch.

en they told us we were stopping at Hylton Castle on the way to the Old Hall. To look at something in the stonework that we probably wouldn’t be able to see clearly. Did I tell you this was a dream come true? Well if I did I was definitely lying.

Sometimes you just have to suck it up, as old people think young people say.

I’d caught my breath and dried my tears by the time the day arrived, and adjusted to the fact that my life was now destined to be a bit more cobwebby. ere were clear blue skies and bright sunshine – in other parts of the country. Here it was really cold and pouring down.

ere seemed to be loads of adult helpers, almost as many as us. is thought went through my brain as I turned to Andi and we both said almost the same thing. Well, at least we had similar thoughts.

“We’ve all got one!”

and

“Aaaaaagh!”

We were clearly going to be paired up or buddied up (pass me the old tin pail pretending to be a sick bucket). Lots of these people I’d never seen before, but I’d heard rumours about Reading Partners and Business in the Community and (Nooooo!) parent helpers. I felt faint.

Mine came and sat next to me, then smiled, but said nothing. ere was something slightly odd about him that I couldn’t put my finger on. Maybe it was his clothes. I couldn’t tell if they were really trendy or really old-fashioned, but things are a bit like that these days, with all this retro stuff being a bit of a minefield.

I had the window seat. e rain seat. e Can’t actually see anything out there, but I’m sure it’s absolutely fascinating seat. I still looked outwards though, because I was a little bit freaked out by the man next to me.

en he tapped me on the shoulder, which made me jump much more than I should have done, and there probably wasn’t really much call for me to do that high-pitched squeal, but there you go.

I slowly turned round and looked at him and he was pointing to a screen at the front of the coach. is was pretty high-tech compared to the last coach we used for a school trip. Andi said she still had a bad back from trying to give that one a push- start from the Wetland Centre. Mind you, she also claimed she’d been pecked by something called a greenshank. She always took things too far, so I took her story with a pinch of salt crystals from the bottom of a large iron pan in a salt

house. (See, I do sometimes listen in some of my history lessons. Once in a while, I even tune in on a school trip.)

e screen was showing a little video of Hylton Castle and the camera was zooming in one some sort of shield in the stonework. e subtitles said it was the Washington Family coat of arms, although it was incomplete, with a couple of stars missing. e man next to me was nodding in a strange knowing sort of way, then shaking his head and sighing. I had absolutely zero idea what he was thinking.

A couple of minutes later we pulled up at the castle, and were given a very quick guided tour by one of the volunteers. Our teachers said we could only stay for a short time, and the volunteer looked a bit crestfallen, but Mr Biddick told them we’d probably come back for longer another time. Mr Biddick was famous for being economical with the truth if it made his life easier. Last year he told the Year 10 football team they’d probably have a five-a-side match against the staff on the pitch before a big match at the Stadium of Light. Some of them are still complaining about it, and asking when it’s going to happen.

We got back on the coach before Miroslav had even got off. It’s fair to say he was the most laidback pupil in the whole school, yet somehow also the one who made most profit from break-time sales. I expected him to be selling pieces of Hylton Castle tomorrow, even though he’d stayed on the coach the whole time. Big business or politics awaited him. Truly Gifted and Talented.

My ‘helper’ was a bit more talkative on the short drive to the Old Hall. He said it was a pleasure to come on such a trip and see a new generation investing in our collective heritage. I wondered if I could program him into using some smaller words, maybe something like ‘old stuff’.

e chat went up a notch as soon as we got to the main destination. He seemed to become more alive. It was difficult to say how old he was, but if enthusiasm were youth, he’d be a big baby. at’s not quite right, but I’m hoping you know what I mean. He was up for this.

Straight away he started talking about George Washington’s family and King Edward 1 and someone known as William Tempest which, to be fair, I thought was a pretty cool name. I surprised him by telling him something about the old milk house and buttery. I was going to say something about veganism, but I thought it might go over his head.

When we went outside, on our way to have a look round the gardens, he turned, pointed to the wall, and asked,

“Does this stone look any different to the others?”

“I suppose it’s a bit more worn, and it’s got some of those chisel marks. And, I don’t know if this is daft, but it seems smaller than the others. It’s kind of set back a bit.”

“Spot on, young George. Now for a long time, people thought they were mason’s marks, but they were made by me. e Washington coat of arms you didn’t quite manage to see earlier, was on this stone as clear as day. Until I removed it. I didn’t want people just concentrating on the American connection. I wanted them to think more about local people, about the people who worked here, not the ones who ruled over them. is family crest was much better than the one at Hylton Castle. And that’s not all. ere was another one on the other side of the dining hall. I took it out and kept it in storage for a few hundred years until I heard they were renovating the Arts Centre. I put it in there.”

is had all very suddenly taken a very strange turn. Who was this helper? What sort of local business would have volunteered his services to our school? Were they trying to farm him out so he didn’t do too much damage to their customer base? is was seriously weird. I thought my best bet was to humour him.

“So I could go and see it? e one at the Arts Centre?”

“Well, yes and no. You see, I put it in backwards. I can tell you where it is and you can find the

I actually laughed at that, and considered punching him on the arm, but decided against it. I had a strange feeling my fist wouldn’t actually engage with his body.

stone – it’s obviously slightly different to the surrounding ones, but you’ll have to believe me that the coat of arms is on the other side of it. You’ll have to trust me. Can you do that?”

“Yes, I suppose so.”

For the rest of the visit he told me a load of amazing facts, with sentences which sounded as though they’d been lifted straight from the guide book. He knew a lot. He helped me fill in a booklet they’d forced on us. I copied word for word what he was telling me. On question seven, just as I’d finished writing, he said,

“What’s that rubbish you’ve written there? It was closed in 1933, not 1833. Don’t believe everything you hear. Maybe you should have done a bit more research before you came, instead of treating me as some sort of glamorous superbrainy AI assistant.”

I actually laughed at that, and considered punching him on the arm, but decided against it. I had a strange feeling my fist wouldn’t actually engage with his body.

When it was time to get back on the coach, I turned to him and asked him to wait while I went to fetch Andi. When I returned, gabbling about the Washington family coat of arms and the three stars, he was gone.

“But, Andi, I’m telling you, he was – he knew all this stuff – it was as though –”

is time she punched me on the arm, and pretended to be a greenshank pecking me as we walked down the aisle.

I spent the journey back to school feeling very confused, but also quite happy and very enthusiastic about the weekend’s history homework. I felt I’d be able to write loads for a change, and I couldn’t wait to get started.

As we got off the coach, Ms Jopling pulled a dirty old sack off the luggage rack. e bus driver rolled her eyes and tutted, then smiled when she saw what it was. Ms Jopling waited outside the bus and as each of us got off she gave us something. She said we had history in our hands.

“What’s this, Miss?”

“It’s a lump of coal, George.”

“Yeah, I, er, knew that, like. I just meant – well, er, thanks, Miss. And Miss –

“Yes, George?”

“e trip. It was all right.”

Sharon Milley

Deemed despicable, dreadful. Doomed for destruction.

Sharon Milley

Long before climate change, the world relied on black diamonds. Diamonds that changed everything; bringing immense wealth for a few, relative wealth for many:

Men who worked long hours, risking life and limb to make the rich richer, whilst their wives toiled at home –struggling to make ends meet.

Yet despite their struggles the community was strong. And when the black diamonds became scarce decisions were made to close pits and demolish homes.

e ‘Great Powers’ graded villages –A – B – C and D D for doomed, no longer able to be fleeced to make them rich.

Devastation and destruction for communities they described as dire. Dastardly saying it was to prevent deprivation, and folk should be delighted to be moved to new homes, away from family and friends.

No money spent on the damned villages, conditions became dreadful, dangerous; the people sat in despicable, dilapidated homes. Yet they were not daunted and began to fight back.

ey wanted to show that authorities had been delinquent in their duties; making placards with daring statements, showing they were devoted and dependable, that their villages should not disappear.

42cm x 30cm

42cm x 30cm

60cm x 42cm

ey said he was the villain, that he’d terrorised their lands; feasting on sheep and cattle, dragging them to Penshaw Whelk Sands.

ey said he found the meat too tough, so turned to lamb and bairns; eating them up whole. Mams weeping when they didn’t return.

Rumour said he was so big, he’d wrapped himself around the hill. at the paths he made by doing this, everyone can see them still.

But the truth of it is, that Lamby was quite small and when thrown down the well, out of it he could not crawl.

ey said young Lambton had gone to war but he’d ran off to live in trees. At first he’d lived off plants and fish, would steal the occasional cheese.

Yet John, he was so hungry, he began to look for meat; he stole some of the livestock, but the sheep would loudly bleat.

So he’d wait until night fell and don a great disguise. He stole the children as they slept and made them into pies.

en one day he felt so bad for all that he had done, he came out of his hiding place saying he’d returned from war as the battle was won.

To explain away the missing bairns he told the story of Lamby worm: that grew so big ate everything, it made the people squirm.

John dressed as if for battle, took his sword into the Wear. Insisted he had to be alone, told people to steer clear.

After several hours of walking round he returned back to his home. Saying that his family was cursed and that he should go to live alone.

Owen Saunders

When I was very young, my grandparents took me along the Wearside path from Fatfield to Cox Green, a lovely woodland walk passing Mount Pleasant Park, where ducks, geese and kittiwakes still huddle by the water’s edge, and under the towering sandstone arch of the Victoria Viaduct. I don’t have a real memory of this outing, but only know it from Grandma Jean’s recollections.

‘We stood on the riverbank when the tide was out,’ she tells me between sips of a Cup-a-Soup. ‘You were on your granddad’s shoulders, watching the horses in the river.’

is path, and the adjoining Beatrice Terrace by the park, is the site of many memories for my family. ough the street today branches off into small, bourgeois clusters of detached houses, all trimmed hedges and Teslas, it was once one of many streets occupied by pitmen and their families in the middle of the twentieth century. It was also the street Grandma Jean was born on, and where her mother, eighty-three years ago, took a walk that would change the course of both their lives.

My grandma was raised in Harraton Colliery by the smart, forward-thinking Cilla and kind but ‘pitmatic’ Scottie ompson, who, like most of the men in the area, worked as a miner in ’Cotia Pit – so named because of the street it was on, Nova Scotia.

‘Living in a pit village meant you got the pit bus whenever you could,’ Jean explains. ‘It went all around the area, and we always used it to visit the Lophouse in Fatfield. at was what we called the Gem picturehouse, ’cause it was falling to bits, you see. Course that’s not there anymore.’

This is a recurring theme in Grandma’s stories: buildings, meeting places, whole streets demolished to make way for new urban developments. Before she turned sixteen, the street she’d grown up on was condemned and swiftly bulldozed, spelling the end of their Harraton residency –but Jean’s roots snaked far more complexly through that earth than she ever realised as a child.

‘ere was a pitman on the bus who was always very friendly towards me,’ she says. ‘He’d always smile and say, “Hello, bonny lass”, and would often give me half a crown, which of course was a lot of money back in them days. He always got off on Beatrice Terrace.’

She never thought much of these interactions until later, after she’d laid a sheet of paper down in front of her mother and demanded to know the truth of her identity.

‘I was a very nervous child, partly due to the frequent air raids, of course, but also because of what children at school used to say to me: “Well

that’s not your real mammy. One day your real mammy will come and take you away.”’

By the time she was eleven, these years of taunts from other children, who seemed to know more about her than she knew about herself, finally brought her to a point of burning curiosity. She scoured through every cupboard and drawer in the house in search of something, anything, to explain the truth of it. She found it in the form of an adoption certificate.

‘Cilla was a storyteller,’ Jean says. ‘She was always an open book, and loved passing on family histories. e adoption had never come up before, of course, but once I confronted her about it she told the whole story from start to finish.’

Eleven years prior, Cilla was on one of her regular walks from Harraton to visit her relations in Cox Green. at day, however, she took a detour. She walked up Beatrice Terrace, past the rows of pitmen’s houses, and stopped at a garden where a young woman lived with her father and brother – and her little baby. Cilla’s husband Scottie worked with Benny Bradley, a cantankerous man with old-fashioned values, whose unmarried daughter Jemima, or Mim, had just given birth. e father was nowhere to be seen. With Mim unable to work and an extra mouth to feed, Benny mentioned to his friends their need for someone to take the baby in.

‘My parents already had Arthur at home, but he was from Cilla’s previous marriage, you see, and he was already a man by then, serving in the war. ey had no children together. So my dad came and told me mother what Benny had said.’ Jean says. ‘Cilla thought they were too old to be raising another bairn, but said she’d have a look anyhow.’

When Cilla arrived at the house on Beatrice Terrace, she was greeted by Mim in the garden. By all accounts, she took one look at the baby girl nestled there in the pram and said, ‘“Wrap her up, I’ll take her.” She was always a joker, me mother, but she really meant it that time. ey took me in almost straight away.’

ere are moments in all our lives where we meet a fork in the road, where the future hinges on which path we choose to take. For the ompsons, this came four years later, when a newly-married Mim visited them in Harraton. With the newfound stability of married life, she and her husband Jonathan decided it was time to take Jean back, and, since the ompsons hadn’t legally adopted Jean, their guardianship was as unofficial as it had been at the start. But four years is a long time in raising a child, and Cilla was torn. Mim and Jonathan were still so young, she argued, and had plenty of years to build a family of their own. In those four years, Jean had become their daughter; Cilla implored Mim not to take her back.

I can only imagine the pain of that conversation for both women. e ompsons’ care of Jean was never intended to be permanent and Mim had held onto the hope that she would take her baby back one day. Meanwhile, Cilla had spent every day of the last four years raising Jean. ere is a world where Mim took my grandma back, where she grew up as the older sister to Mim and Jonathan’s three boys, where Cilla and Scottie were relegated to the roles of godparents, perhaps a world where a sixteen-year-old Jean, by virtue of where she lived, never met my Granddad John at a Chester-le-Street dancehall.

is is, of course, not the road we find ourselves on. ‘In the end,’ my grandma says, ‘Mim decided to break her own heart to avoid breaking Cilla and Scottie’s.’

The couple had scarcely left when the ompsons filed to adopt Jean. But roads that diverge can sometimes meet again down the line. For my grandma, this wouldn’t happen until she was twenty-five and living with my granddad and their two children in Birtley – the day the kindly man from the bus came knocking.

As it turned out, this mystery man who had been so friendly to Jean when she was a child was Mim’s little brother, Jim. His involvement in the story of Jean’s parentage went beyond his knowing smiles and half-crowns on the bus, though; as a teenager, he had delivered letters from Mim to

Ireland, part of her desperate attempts to make contact with her baby’s father – and this wasn’t the last time he acted as a go-between for his sister.

‘He often called in when he was passing through,’ Jean tells me. ‘Me mother had explained who he was to me years before, and he’d stayed friendly with us ever since.’

at day, though, he turned up with an offer. ‘He asked me, “Would you like to meet your real mam?” Of course I said, “Yes.”’

We can never truly know why Jim chose that day to organise this reunion, but the timing for Jean would have been particularly meaningful. Only two years prior, while pregnant with my mam, she had lost her adoptive mother to a short illness. Perhaps Jim was conscious of this loss, and saw a reconciliation with her birth mother as a way of mitigating Jean’s grief. So, after twentyfive years, Mim and her daughter were reunited.

When she laid eyes on her adult daughter, Mim was overcome with emotion.

‘I’d turned up to her house that day with a bit of a chip on me shoulder,’ Jean says. ‘But when I saw how humbled and upset she was by what had happened, that sharp disappeared. I understood her reasons. Another great relief, too, was that

her story was identical to Cilla’s.’ Despite all the heartbreak, neither woman had embellished the story to paint themselves in a more flattering light. What had happened had happened, the roads had parted, and now they were intersecting again.

Even after this reunion, Mim was never really Jean’s mother, and there was never a question about her replacing Cilla. Instead, the two women became firm friends, and Mim became ‘Aunty Mim’ to my mother and her brothers. rough her, Jean acquired brothers of a similar age to herself – Robert, John and Raymond – who would become close family members. Uncle Robert once told her that Mim often used to stare wistfully at a photo of a baby girl when they were children. ey would ask who she was and Mim would only smile sadly and say, ‘Just a little girl I used to know.’ ey never knew who this girl was until they met Jean in 1965.

My Uncle Robert sadly passed away when I was still fairly young, but I remember him as one of many close members of Grandma’s sprawling family, whose branches extend in various directions. Yet, there is one piece of the puzzle that has yet to be solved: the identity of my greatgrandfather.

‘One of the first things Mim asked me was, “Do you like dancing?” I said, “Why, yes, I love it.

folk looked after each

instinctively, a time that has now faded into memory.

I would go dancing every day if I could.”’ Grandma chuckles to herself. ‘Mim said, “Well, you don’t get that from me – I’ve got two left feet. But your father was a professional, a dancer from County Kerry in Ireland.”’

Mim had met this mystery Irishman while working down South. After a two-year courtship they were engaged, but their romance ended abruptly when the Second World War broke out and he disappeared. Mim never knew whether he joined up, moved cities or returned to Ireland, where he may have already had a family. Her letters to his mother in Kerry received only one response: that she had no idea where he was. In the years after their reunion, Jean never thought to ask more about him, proceeding under the assumption, as she puts it, ‘that I had plenty of time with her.’ en, in 1977, Mim died suddenly of a heart attack. To this day, Jean can’t recall her father’s name.

My grandmother’s story has always struck me as extraordinary – the mystery of it certainly remains compelling. Even so, it isn’t the only one of its kind from that period, a time when working-class folk looked after each other almost instinctively, a time that has now faded into memory.

‘Mim paid for having me all her life,’ my grandma says matter-of-factly. ‘She worried for

years about the pain she might have caused by giving me away’. ere was, perhaps, a lasting ache from this decision. Even now, my grandma claims she never felt wholly connected to another member of her family until she had her firstborn. In the end, though, she enjoyed the comforts of two distinct families – on one side, the loving, capable parents that raised her and, on the other, the brothers that she acquired through Mim, not to mention the beautiful, if brief, friendship she shared with Mim herself. And though the mystery of Jean’s father remains unsolved, it strikes me just how irrelevant he really is to this family story. After all, it seems a far greater blessing that Mim, after all those years, was finally able to reunite with that little girl she used to know.

11.30PM

Lisa Burns

Tuesdays are the worst. e summer Tuesdays when the heat sits like a cloud above your head, oppressive and holding onto the smells of sweat and last night’s cooking.

When the day feels the same as that one, hot and humid and hazy, I hear the noise too. So loud that I cover my ears and grit my teeth against it until it passes. Until it passes right through every bone and every fibre of my being. I count to thirty-four, one moment for each of them.

ose days are the ones that I can’t get out of bed. e days when I know that I can’t go on.

I was born into a mining family so I knew I would marry a miner. It’s just what happens. I wasn’t that keen on my life being mapped out for me but when I met my Joseph I soon changed my mind.

He caught my eye as soon as I entered the dance hall. Both of us in our best clothes, his shoes shined and my hair curled by my best friend, Mary. It was love at first sight.

Mary couldn’t believe I’d never seen Joe before. Apparently, he was the star of the colliery football team. Not something I was particularly interested in, unlike her.

Since that night, we were inseparable.

I tried hard to make our little miners’ cottage a home but money was tight so there were very few luxuries. Once our omas then Michael came along I had to stretch those pennies even further.

It never was easy. Joe worked such long hours and when he did come home all he’d be fit for was his bed. He’d stopped playing his football by this point, it was like the tiredness was in his bones. He had a weariness about him.

He never talked to me about what the mines were really like. He always said I was better off not knowing so I didn’t worry.

But of course, I worried. All us wives knew the dangers that lived down there, always one wrong move or one stroke of bad luck away from death. Not that we spoke about them much either. ere was this attitude of stoicism from the men that rubbed off on us. at and the desperation we had to protect our children from it all.

e money got tighter as omas and Michael grew older. Joseph and I went without but I couldn’t stand to see my boys walking around in shoes with holes in the soles. ere weren’t any more hours that Joe could work and he was too proud to let me take a job at the surface. Besides, Michael was sickly when he was young and I spent a lot of time caring for him.

It broke my heart that first day I waved omas off to go to work with his father. He was twelve years old. Still a child. I fought Joe harder when it came to Michael but it was no use. Especially when the daft boy said he wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps. I always thought he wasn’t strong enough for any of it. e dust, the heat, the back breaking physical labour, but he proved me wrong and held his own. Even seemed to like it. More than his father did by this point anyway. e circle of mining life continued.

Joe was a shell of the man that I married; weak, exhausted, disillusioned with it all. He talked often of leaving and finding an easier job to do but I knew he wouldn’t. His friends were all the same. ey’d all had enough but had nowhere else to go.