CONTENTS

4 CHARTING A NEW COURSE: THE CASE FOR A JUST ENERGY TRANSITION

The oil and gas industry has long been defined by convention and capital.

B y : Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr.

5 THE FUTURE WE LEAD

Why women are central to sustainable business and the law.

B y : Fatima Gattoo, directorReal Estate Law.

7 CROSSING THE AISLE

Allies in the struggle for gender justice and beyond.

B y : Nadeem Mahomed, director – Employment Law.

9 DISRUPTION, DETERMINATION AND DISCOVERY

Not your typical law story, but one about finding your niche.

B y : Lebohang Mabidikane, director – Competition Law.

10 WOMEN BREAKING BARRIERS AND SHAPING LEADERSHIP

Women play a powerful and positive role in leading transformation.

B y : Lucinde Rhoodie, director –Dispute Resolution.

11 THE POWER OF THE PIVOT: LESSONS FROM AN UNCONVENTIONAL LEGAL PATH

Despite an on-off start to her career, mentorship has been the common thread in her career journey.

B y : Denise Durand, director — Dispute Resolution.

12 MILESTONES, STRUGGLES AND TURNING POINTS

Rising to become a leader through experiences and challenges.

B y : Yvonne Mkefa, director –Employment Law.

13 FROM XENNIAL TO ZENNIAL: TWO LAWYERS, ONE JOURNEY OF GROWTH AND GROUNDING

How generational differences shape experiences in the legal profession and what it means to grow while staying grounded.

B y : Nastascha Harduth, director –Dispute Resolution and head –Corporate Debt, Turnaround & Restructuring, and Tebello Mosoeu, senior associate.

15

THE ARCHITECTS OF SUSTAINABLE BUSINESS

Why women are central to sustainable business – connecting gender equity with business resilience and sustainability.

B y : Calinka Murray, Practice Development director.

16

WOMEN BREAKING GROUND

How women are carving a path in Namibia’s oil and gas sector.

B y : Ilda Dos Santos, director –Corporate & Commercial and Oil & Gas sector (Namibian Office).

17

ADVANCING GENDER PARITY IN INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION

The legal profession has long been marked by under-representation of women, however, international arbitration presents a more optimistic picture.

B y : Veronica Connolly, senior associate – Dispute Resolution.

18

CHANGES, CHALLENGES AND COURAGE

Recounting her experiences in a not-always-smooth sailing career journey.

B y : Belinda Scriba, director –Dispute Resolution. 19 26 25 25

19 THE WEIGHT OF THE BLAZER

Reflections on her career, challenges, choices and responsibilities.

B y : Deborah Sese, senior associate – Corporate & Commercial (Kenyan Office).

20 PREPAREDNESS AND OPPORTUNITY

Reflections on a career filled with aspirations, possibilities, challenges and achievements.

B y : Sheilla Mokaya, associate –Corporate & Commercial (Kenyan Office).

21 LIFTING AS WE RISE

The importance of women mentoring women in law and business.

B y : Brigitta Mangale, director –Pro Bono and Human Rights.

22 WHEN OPPORTUNITY KNOCKS

Sometimes, the most rewarding careers begin not with a plan, but with an unexpected opportunity.

B y : Tessa Brewis, director –Banking, Finance & Projects and joint head – Projects & Energy.

23 MENTORSHIP AND COLLECTIVE UPLIFTMENT

Stories from mentorship relationships that have changed the trajectory of careers and lives.

B y : Kuda Chimedza, director –Banking, Finance & Projects.

24 THE PEARL THAT BROKE ITS SHELL

Embracing her youth, identity and circumstances to take her place at the table.

B y : Nomlayo Mabhena-Mlilo, director – Dispute Resolution.

25 SHOWING UP, AND DOING SO CONSISTENTLY

Secrets behind her success.

B y : Phetheni Nkuna, director –Executive Management Office and director – Employment Law.

26 THE FABLE OF THE FEE-BURNER

How the shared pursuit for excellence in the legal sector has shaped her career.

B y : Emma Hewitt, practice management director –Corporate & Commercial.

27 PURPOSE WITH POWER

Empowering change in

South African legal practice: the story of SA LawLabz, HiveLaw and the transformative role of female leadership.

B y : Retha Beekman, managing director of SA LawLabz.

29 LEGAL REFORMS EMPOWERING WOMEN

Two pivotal employment law developments advancing gender equality in the workplace.

B y : Anli Bezuidenhout, director – Employment Law, and Nadeem Mahomed, director – Employment Law.

31 BUILDING A BRAND WHILE BUILDING CONFIDENCE

Reflecting on her career journey, mentorship and leadership.

B y : Leila Moosa, senior associate – Employment Law.

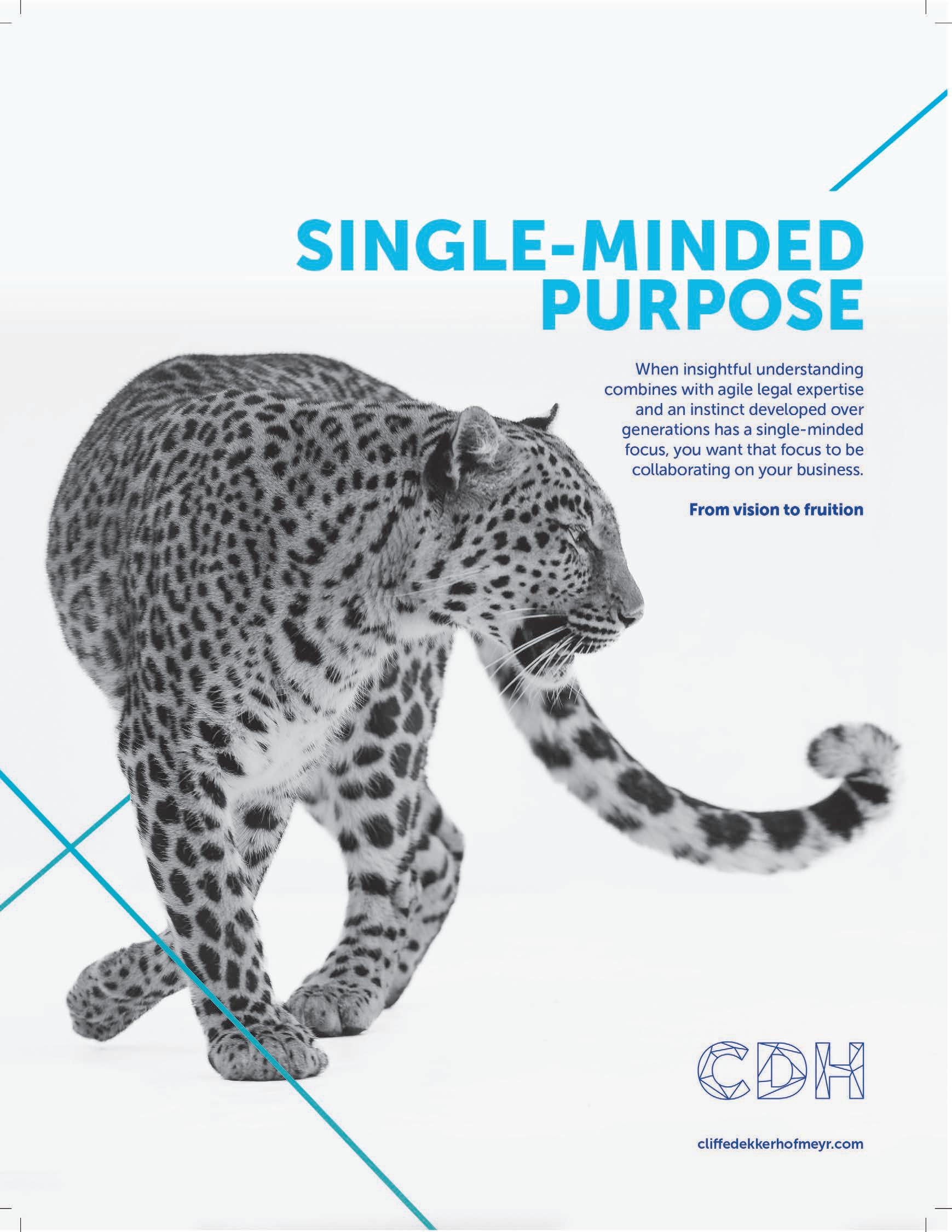

Charting a New Course: The Case for a Just Energy Transition

The oil and gas industry has long been defined by convention and capital. However, as we peer deeper into the mists of complexity, what this sector truly needs – and has always needed – is something bolder: a catalyst for transformation. Megan Rodgers, head of the Oil & Gas Sector at Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr, embodies that bold, forward-thinking leadership – guiding the industry toward a more innovative and inclusive future.

By CLIFFE DEKKER HOFMEYR

According to the 2021–2025 Women’s Empowerment and Gender Equality Strategy for the Energy Sector, women make up just 20 per cent of South Africa’s oil and gas workforce, with a mere 17 per cent in middle or senior leadership roles. In a sector still shaped by deep-rooted barriers, where do aspiring women turn for a roadmap – or a role model? Enter Megan Rodgers who trained as an upstream mergers and acquisition (M&A) corporate and commercial lawyer. For the past decade, she has had a ful lling and fast-paced career in this unique area of law, viewing the energy sector in South Africa through an African lens.

“The energy sector sits at the heart of our nation’s growth story,” says Rodgers. “This is not just about volumes and capital. We need to focus on the transformation of our economy, our institutions and the opportunities we create for future generations.” Aligned with this, Rodgers brings legal precision, strategic foresight and a deep sense of responsibility to what she believes is one of South Africa’s most consequential industries. As a result, her name commands respect across boardrooms, government ministries and multinationals. However, it’s not just her expertise across the oil and gas value chain that sets her apart. It is her vision of an equitable energy economy that is commercially sound, socially inclusive and legally robust.

A TRUSTED ADVISOR, A PASSIONATE MENTOR

Rodgers is considered one of South Africa’s foremost experts on petroleum regulation and energy law. She is a trusted advisor on matters from upstream M&A transactions to the intricacies of the Upstream Petroleum Resources Development Bill in South Africa. Her work bridges the demands of global investors with the imperatives of national development. Yet, her leadership carries another weight: Rodgers is among the rst black women to occupy such a senior legal role in the male-dominated sector. And, she is determined not to be the last. “I’ve often walked into rooms where I was the only one who looked like me,” she re ects. “Now, part of my role is to make sure that changes.”

frameworks that enable both investor con dence and broad-based participation.

Rodger’s leadership arrives at a pivotal moment. As South Africa accelerates the Just Energy Transition, the country needs legal minds who can translate ambition (and emotion) into action and do so with integrity. Rodgers is just that kind of leader. She does not just interpret the law; she helps shape the future it makes possible.

To the next generation of young women looking to get into oil and gas (or any industry for that matter), her advice is powerfully direct: “Be unapologetically excellent. Be clear on your purpose. Prepare thoroughly. Give yourself permission to learn every day, to make mistakes and to break down new barriers. Once you’ve claimed your space, use it to open the door for others.”

Rodgers isn’t simply advancing energy law. She’s forging a legacy – one deal, one policy and one up-and-coming leader at a time.

As part of this, Megan mentors young legal professionals with the same passion she brings to complex energy deals. She drives transformation not only through policy advice, but also through the culture she helps build within CDH, as a member of CDH’s executive committee, and across the profession. Rodgers also contributes thought leadership on the intersection of energy, justice and regulation, advocating for policy

Megan Rodgers

THE FUTURE WE LEAD

Why women are central to sustainable business and the law

In the hive of leadership, true transformation begins with intention. When we speak of sustainability, the conversation often turns to technology, policy, and innovation. Yet one of the most powerful drivers of lasting change lies within our own organisations and communities: women. By

FATIMA GATTOO , director – Real Estate Law at Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr

As we navigate an era de ned by climate urgency, social upheaval and economic recalibration, the case for centring women in sustainable business – and in the legal profession – is not just compelling. It’s critical.

NATURE’S BLUEPRINT:

THE HIVE AS A MODEL FOR LEADERSHIP

Consider the honeybee. When a hive loses its queen – the singular being capable of giving life to the colony – it faces collapse: no new eggs, no future.

However, the bees do not panic. They respond with clarity and collective wisdom. They choose transformation.

LEADERSHIP IS NOT INNATE – IT IS CULTIVATED. TRANSFORMATION OFTEN BEGINS NOT IN TRIUMPH, BUT IN CRISIS AND VISION.

Ordinary larvae are fed royal jelly – a rare, nutrient-rich substance. This act of nourishment changes everything. The chosen larvae are not born different, but they are treated differently. Their bodies grow stronger. Their life spans expand. Their destiny shifts.

A queen emerges – not by birthright, but by care, vision and support.

This is not just biology. It is a lesson: leadership is not innate – it is cultivated. Transformation often begins not in triumph, but in crisis and vision.

THE LAW FIRM AS A HIVE: A LIVING, BREATHING ORGANISM

In the legal profession, the metaphor holds. Law rms, like hives, are complex ecosystems. When faced with disruption – from climate regulations and environmental, social and governance (ESG) compliance to arti cial intelligence (AI) ethics and corporate accountability –they must respond not with fear, but with foresight.

And, in these moments, women lawyers rise – not by chance, but by crisis, vision and transformation.

The strongest leaders often emerge not from pedigree, but from potential. Not from privilege, but from preparation. Women in law, especially those who have been mentored, supported and fed opportunity, embody the qualities today’s clients and communities demand: resilience, empathy, clarity under pressure and a deep commitment to justice and sustainability.

WHY WOMEN MATTER TO SUSTAINABLE BUSINESS AND LEGAL PRACTICE

Sustainability is not just about carbon footprints or climate disclosures. It’s about longevity, responsibility and building systems that adapt and endure. In law rms and boardrooms alike, this means cultivating leadership cultures that re ect society – diverse, inclusive and driven by long-term purpose.

Women bring transformative value in at least four critical areas:

• Collaborative leadership: like the collective intelligence of the hive, women often lead with inclusion, empathy and consensus – fostering cohesion and trust.

• Client alignment on ESG goals: female legal and business leaders are at the forefront of integrating environmental, social and governance principles, not just advising on compliance, but shaping ethical direction.

• Resilience during crisis: research shows women excel in crisis leadership, navigating transitions, social change and economic upheaval with steadiness and clarity.

• Mentorship and legacy building: women who rise often uplift others, creating sustainable leadership pipelines that rely not on luck or legacy, but on support and shared vision.

A SILENT BUT PROFOUND LESSON

The bee shows us, without words, that in times of great crisis, despair is not a gamble, but a moment for clarity. A plan. The right choice.

In the hive, a queen is not born. She is supported. Fed. Guided. And so it is in life, law and leadership.

It is not what you start out with that matters most, but what you are given, how you are treated and the choices others make around you, especially in dif cult times. Sustainable business is not just about better products; it’s about better people, better values and better leaders. Sometimes, it is in the darkest moments that the strongest leaders emerge. Not by chance, but by crisis, vision and transformation.

THE PATH FORWARD: INTENTIONAL INCLUSION, SUSTAINABLE PRACTICE

To build businesses and law rms that thrive for generations, we must move from

tokenism to transformation. That means we must be serious about women. We must design ecosystems – like the hive – that nurture potential over pedigree, and cooperation over competition.

• Make equity intentional, not incidental. Choose equity not as a slogan, but as a strategy.

• Support, promote and invest in women at every level.

• Rede ne success – not as short-term pro t or billable hours, but as sustainable impact.

• Lead beyond the boardroom or courtroom into the community.

SUSTAINABLE

BUSINESS IS NOT JUST ABOUT BETTER PRODUCTS; IT’S ABOUT BETTER PEOPLE, BETTER VALUES AND BETTER LEADERS.

Just as bees respond to existential threat with remarkable instinct, so too must we meet this moment of global transformation by creating space for new leaders to rise. Often, those leaders will be women. Not by chance, but by choice. Not just for diversity, but for the future.

In the hive of business – the hive of the law – the future we lead depends on who we choose to support and how we choose to grow.

Women are not a “nice-to-have” in sustainability; they are central. They are the future we lead.

For more information: www.cliffedekkerhofmeyr.com

Fatima Gattoo

CROSSING THE AISLE Allies in the struggle for gender justice and beyond

Allyship, particularly from those in positions of privilege, is more than a gesture – it’s a moral responsibility. True allyship to all women demands humility, self-reflection, and a willingness to lean into discomfort, writes NADEEM MAHOMED , director – Employment Law at Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr

As a lawyer, I was trained to view the law as a powerful mechanism to shape and structure society; an instrument to right wrongs, resolve uncertainty and impose order. In many contexts, this is partially true: the law can provide stability and predictability, particularly where the rule of law is rmly upheld. Yet even in such contexts, the stability law brings is often layered upon histories of exclusion and violence. More often than not, the legal system upholds the prevailing social order even when that order is unjust.

Even where laws are progressive, the assumption that they automatically yield justice is misguided. The transformation of moral aspirations into legal principles does not guarantee the realisation of justice in lived experience. The association between law and justice is persistent, but

Nadeem Mahomed

dangerously simplistic. Take apartheid South Africa as a stark example: legality and systemic injustice were often synonymous. Racial segregation, economic disenfranchisement and the violent subjugation of black people were legal norms, sanctioned by the judiciary and entrenched through statute. The same system upheld deeply patriarchal structures. In the Cape Colony, sanctions for sexual crimes against women were not applied equally. Race, especially that of the victim, determined how or whether justice was pursued. Women of colour were denied the dignity and protection afforded to white women, who themselves were not adequately protected from patriarchal violence within marriage. In these systems, the law did not correct inequality, it reinforced it.

MISOGYNY, PREJUDICE AND EXCLUSION

Fast-forward to contemporary South Africa where gender-based violence remains a crisis. While the Constitution and statutory framework offer protection for all human bodies, the reality is dissonant. The gap between legal ideals and lived realities is often vast. It is from this place, of both legal training and life experience, that I write: not necessarily as a lawyer, but as someone acutely aware of the many ways exclusion is perpetuated, legally and otherwise. Misogyny, like racism, is not always overt or intentional. It can manifest subtly: in assumptions, in cultural norms and in systems where power is measured by conformity to a dominant mould. In the corporate world, discrimination often masquerades as a lack of “ t.” However, “ t” is frequently code for assimilation into pre-existing, male- (or race-based) dominated norms (how one works, demonstrates ability, speaks, thinks or socialises). Women and people of colour, among others, are often required to dilute or surrender parts of themselves to be accepted. They are judged against unspoken criteria that exclude difference.

TRUE ALLYSHIP DEMANDS MORE THAN SYMBOLIC GESTURES; IT REQUIRES SUSTAINED, TANGIBLE, AND PURPOSEFUL ACTION.

REAL TRANSFORMATION REQUIRES ACKNOWLEDGING THAT SYSTEMIC VIOLENCE AND EXCLUSION ARE OFTEN EXECUTED TACITLY, THROUGH STRUCTURES, SYSTEMS OR TRADITIONS AND SILENCES.

Toni Morrison captures this painful yearning for acceptance in The Bluest Eye, where a young black girl believes that if her eyes were blue, if she could embody whiteness, then she would be beautiful, she would be worthy. This internalisation of inferiority is not only in ction. It is the legacy of societies structured around narrow and harmful ideals of worth, legitimacy and exclusion.

THE HALLMARKS OF GENUINE ALLYSHIP

In this context, allyship, particularly by those who occupy positions of privilege, which is always relative and shaped by circumstance, is not a mark of distinction, but a moral obligation. With respect to gender and gender identity, being an ally to women, including transgender women and transgender men, is not an act deserving of praise or celebration; it is a duty. It entails recognising human dignity and actively making room for others and being willing to relinquish power when justice so requires. True allyship demands more than symbolic gestures; it requires sustained, tangible, and purposeful action.

Genuine allyship is a process. It requires humility, re ection and the willingness to be uncomfortable. Declaring oneself “anti-sexist” or “anti-racist” is easy. However, real transformation requires acknowledging that systemic violence and exclusion are often executed tacitly, through structures, systems or traditions and silences. Often, those who perpetuate it do so unconsciously, as passive custodians of an unjust order.

To not be sexist (or racist, or homophobic, or xenophobic, or Islamophobic, or antisemitic) is not a xed state. It is a continuous ethical journey. It demands that we scrutinise our beliefs, our assumptions and the reasons behind our actions. It demands that we ask dif cult questions about the ideologies that shape our politics, economics, world views and everyday interactions. The ever so eloquent writer, James Baldwin once wrote, in respect of the American context:

“Whatever white people do not know about African Americans reveals, precisely and inexorably, what they do not know about themselves.” The same holds true for men in respect of women, or heterosexuals in respect of queer people, for example. Our prejudices, even when buried under years of moral labour, never fully disappear. They linger as the residues of the societies and communities that shaped us. They remind us of the persistent gaps in our ethical selves, gaps that require constant vigilance, care and correction.

MISOGYNY, LIKE RACISM, IS NOT ALWAYS OVERT OR INTENTIONAL. IT CAN MANIFEST SUBTLY.

Allyship, then, is not only about speaking on behalf of others, it is also about listening. It is about stepping back, stepping aside and sometimes stepping down. It is about confronting the hollow spaces within ourselves where prejudice and indifference thrive and refusing to let them de ne who we are, or what kind of society we build.

more information: www.cliffedekkerhofmeyr.com

DISRUPTION, DETERMINATION AND DISCOVERY

Let me start with the ultimate disclaimer: law is not for the fainthearted. It’s not glamorous. You will not suddenly become in uential, prestigious or purposeful the day after you graduate. It’s a calling that demands all of you, especially at the start of your career. And, if you’re a young woman, particularly a young black woman, that demand can feel endless. However, this is not a story of despair. This is my story of disruption, determination and discovery. One that, I hope, will inspire you to follow the legal path that works for you.

I didn’t follow the script. I became a mother straight after matric. While my peers lled lecture halls, I was working at a bank, raising a child. I stayed there for six years, steadily climbing, but always feeling like I was capable of more. Law wasn’t a passion at the time – it was a practicality because I needed to attain professional and nancial stability for my daughter’s sake.

STUDYING, SURVIVING AND SOUL-SEARCHING

At 24, I walked into my rst lecture hall. Most of my classmates were barely out of high school. I was soul-searching in tutorial rooms and packing lunchboxes in the morning. Balancing parenting with studying wasn’t a cute juggling act –it was a matter of survival. While my peers were buying their rst cars, I was catching taxis to class. I had to remind myself it wasn’t a race. I wasn’t competing. I was building something big.

A turning point came in my second year. I was accepted for a vacation programme at one of the top law rms in South Africa. That exposure was everything. It opened my eyes to what was possible. Thereafter, I went on to do vacation work at various top law rms every six months.

This is not your typical law story, which is precisely why you should read it, writes LEBOHANG MABIDIKANE , director – Competition Law Practice at Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr

SAY HELLO TO “BIG LAW” –WHEN THEORY MEETS REALITY

Even after excelling at university, nothing prepared me for articles in a top-tier rm. Nothing! It was like being ung into the ocean with only the theory of how to swim to keep you alive. I was the oldest in my intake. I was married. When serving articles you’re not a top student; you’re an extra pair of hands. It requires great humility to accept that you’re at the bottom of the food chain, which can be challenging.

THIS PROFESSION IS INTENSE AND REQUIRES PLENTY OF SELF-SACRIFICE.

I wanted to quit. The culture, the long hours and the fast pace drained me. My self-esteem was shredded. I was working myself into the ground, and it still didn’t feel like enough. When I nally nished my articles, I left practice to think about my career path; I was convinced I was done with practice. Then, I joined the Competition Commission as a junior merger analyst. That was my redemption. I felt valued, I rebuilt my con dence. My career ourished, and I learned something crucial: I was good at this, and I wasn’t done.

STAYING AT THE TABLE, ON YOUR TERMS

We don’t talk enough about how many women leave law practice and never return. This profession is intense and requires plenty of self-sacri ce. Without mentors, a support system or a reason bigger than the next promotion, you will struggle.

Becoming a partner at Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr and a member of the executive committee was a milestone for me. However, it wasn’t the pinnacle. The real achievement has been learning to trust myself and knowing that the buck stops with me when it comes to advising clients and being comfortable with that. Now, I mentor young lawyers, especially women. I ask them the one question no one asked me during articles: “Is this what you really want and are you willing to work hard to grow in the profession?” I’ve seen people change their lives because of that question. Law has many paths. You don’t have to choose the one everyone else is on.

WOMEN BREAKING BARRIERS AND SHAPING LEADERSHIP

When I entered the legal profession in 1998 at the age of 23, the landscape for women was markedly different. Over the years, it has been encouraging to witness the transformation within the industry. Although the journey has been challenging, today we see a growing presence of women in courtrooms, client consultations and, increasingly, the boardrooms of leading law rms.

I am a director at one of South Africa’s top-tier law rms, where I practice in its Dispute Resolution department and lead a team that includes a female senior associate and a female junior associate. Sometimes I look back and wonder – how did I manage to get here? A signi cant part of my success, in addition to hard work and dedication, is due to the commitment, sacri ces and strides women have made in the legal profession.

LUCINDE RHOODIE , director –Dispute Resolution at Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr, writes that women play a powerful and positive role in leading transformation

Our strength lies in embracing who we are – women in law – and leveraging that identity to lead with integrity and purpose. To pretend otherwise is misguided. The progress we see today is the result of generations of women who broke barriers and rede ned leadership in the legal eld. These advancements were not accidental nor were they easy; they were driven by individuals committed to change. The path forward demands continued advocacy, resilience and a collective commitment to equity.

We must continue to recognise, elevate and celebrate the invaluable contributions women make to leadership and social progress. Their collaborative and inclusive leadership styles, unwavering commitment to justice and equity and ability to drive transformational change are reshaping both communities and organisations.

Let us remain committed to creating spaces where women’s voices are heard, their leadership is celebrated and their impact is undeniable.

According to the 2024/2025 annual report published by the Law Society of South Africa (as it was then known), women now comprise approximately 45 per cent of the 33 929 registered attorneys. Furthermore, data from 2022 indicates that there has been a seven per cent increase in women holding CEO and managing director positions between 2019 and 2022.

While these gures re ect meaningful progress, signi cant work remains, particularly in traditionally male-dominated legal practice areas such as corporate and commercial, tax, banking and nance, and dispute resolution.

INTENTIONAL ACTION AND SOLIDARITY

Young female attorneys often seek guidance on how to advance in this profession. My advice is simple: success does not require abandoning one’s identity.

Despite the progress, women still face systemic, cultural and institutional challenges, including gender bias, under-representation in executive roles and unrealistic expectations around work-life balance. Addressing these issues requires intentional action by all women in the legal eld. Women in leadership, in particular, must actively mentor emerging professionals, contribute to the development of gender equity policies within organisations and, most importantly, celebrate and amplify the achievements of other women.

Throughout my career, I have observed a growing culture of solidarity among women in law. In earlier years, young female attorneys often encountered more resistance from senior women than from their male counterparts. It has been great to see that, fortunately, this dynamic has shifted and mutual support among women is increasingly becoming the norm.

As Michelle Obama so powerfully stated: “There is no limit to what we, as women, can accomplish.” Her words serve as a reminder of the boundless potential that emerges when women are empowered to lead.

Lucinde Rhoodie

The Power of the Pivot: Lessons from an Unconventional Legal Path

Despite an on-off start to her career, DENISE DURAND , director –Dispute Resolution at Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr, reflects on her journey

Ihad the time of my life at university, so much so that in my penultimate year, I was unaware that many of my classmates had already secured articles at law rms or were actively pursuing them. By the time I realised I should be doing the same, it was too late. I accepted my fate and decided to take a gap year armed with a law degree.

Less than a few weeks into my gap year, my father gave me the boot, no daughter of his was going to sit at home with a degree. That push turned out to be pivotal. A university mentor referred me to an internship opportunity at a mining company. What began as a short-term role evolved into a two-year stint managing mineral rights at a mining exploration and investment rm. What seemed like a series of chance events would later de ne the sector where I would build my career. While working as a mineral rights manager, I attended law school part-time in the evenings and completed half of my board exams. Eventually, I knew I had to nish what I started. I resigned to take up articles at a small rm in Sandton, aware that not having articles would eventually become a stumbling block. It was a tough decision, one that meant taking an astronomical pay cut and moving in with a friend to reduce costs. However, it was an incredible experience. I learned fast, I had to. It was sink or swim. Within a year, I quali ed as an attorney, and six months later, I secured an associate role at CDH, where I have been ever since.

I never saw any of my roles as temporary or transitional. Whether onsite with geologists in Phalaborwa or handling matters at the Randburg Magistrate’s

Court, my mindset was always: “I’m here, let’s learn as much as possible.” I believe this openness allowed me to grow deeply and meaningfully.

Looking back, I now see how those early experiences laid a strong foundation. Today, as a director, it’s remarkable to see how mining-related matters make up half of my legal practice, an interest that began during that internship.

MENTORSHIP’S GUIDING HAND

The common thread throughout my career has been the power of community and mentorship. A university mentor encouraged me to apply for the internship; a friend told me about a vacancy at a small rm and an acquaintance of a friend handed my CV to the hiring director at CDH. The relationships we have built, no matter how slight the connection, can impact our lives in unexpected ways. While “mentorship” has become a buzzword, I’ve been fortunate to have managers who actively trained and guided me. This journey has not been easy and as I continue to grow professionally, the nature of mentorship has evolved. It’s no longer just about technical skills; it’s about navigating the complexities of work-life balance. This balance is a pendulum swinging between sacri ce, boundaries, rest and nancial independence. I haven’t mastered it, and that’s why mentorship remains essential. It helps guide and reset, and I am where I am today because of the support I received from others.

Some people have a clear vision of their career path from the start. For others, like me, clarity comes in hindsight. I often sit with recent graduates or interns who

MENTORSHIP REMAINS ESSENTIAL. IT HELPS GUIDE AND RESET.

are grappling with grand ideas of how their careers should begin. Sometimes, these expectations cause them to overlook valuable opportunities because they don’t t a preconceived image of success. My advice: stay open and exible. The right doors often open when you least expect them and when they do, embrace them fully.

Denise Durand

MILESTONES, STRUGGLES AND TURNING POINTS

Leadership is a journey that involves others, and an individual rises to become a leader through their experiences and challenges, writes

The debate about whether leaders are born or made has persisted for ages. My view is that a person becomes a leader. Leadership is beyond innate abilities; it is about assuming the role of a leader and accepting the challenge to lead.

Having begun my journey at Bhekimfundo Primary School in Ekurhuleni, Gauteng, then studying law at Rhodes University, and now a director in one of the respected and leading law rms on the continent, I can attest that my journey has been one of becoming a leader.

Some individuals rise to leadership by repeatedly, consistently and diligently availing themselves of seemingly menial and mundane tasks. Over time, their consistent efforts are noticed, leading to greater responsibilities and involvement in signi cant projects.

YVONNE MKEFA

, director – Employment Law at Cliffe Dekker

of analysis paralysis. We have come to know this as the impostor syndrome. What happens when you become conscious of your leadership role? How do you respond when you realise that your actions and words shape how others show up and perform in their daily lives and that your decisions steer organisations?

I APPROACH EVERY TASK AND ASSIGNMENT AS AN OPPORTUNITY TO SERVE OTHERS.

RESPONSIBLE AND SERVANT LEADERSHIP

servant leader. I can trace this from my formative years and see it now in the way I approach important societal and life issues. One example is the longstanding ght to have “a seat at the table”. The ght is about diversity, equity and inclusion. However, it creates inner dissonance because it feels as if I must seek permission to serve others, and this does not resonate with me. There is no doubt in my mind, I became a leader. Although one could argue that I possessed leadership qualities all along, I cannot discount that the encouragement and belief of others enabled me to recognise and embrace my potential and gifts.

That has been the unassuming trajectory of my leadership journey. In my formative years, I led cultural events groups and cleaning projects. At university, I was involved in community outreach programmes. In the earlier years of my career as a young legal practitioner, particularly as in-house legal advisor, I was tasked with leading negotiations with employee organisations in SA and other parts of the world. In the latter years, when COVID-19 hit our shores, I was part of the crisis management committee for a listed company in nancial services, chairing some sub-committees.

You must be intentional about your leadership. You must be clear about your purpose, vision and direction. I became an ardent reader, reading about other leaders and their organisations. In 2022, I obtained a postgraduate diploma in leadership (cum laude) from Stellenbosch Business School (SBS). Through this course, I learned of my leadership style – servant leadership – and, more importantly, about responsible leadership

“The aim of responsible leadership is to create a better world for all and to ensure long-term sustainability,” states the SBS, Centre for Responsible Leadership Studies (Africa) website.

humbling. I never feel I have of I was part of the crisis nancial

Throughout this journey, maintaining balance has been crucial. It was essential to keep my home warm and ensure my family felt valued and an integral part of this journey. I am grateful to the Mkefa Clan for allowing me to “become”.

What’s next for me in my leadership journey? The title of Professor Bonang P Mohale’s book, Lift As You Rise, sums it up. As a leader, I must have a keen interest in the next generation of leaders. I must pay it forward.

These were periods of unconscious leadership, lled with self-doubt and episodes

Responsible leadership is not another leadership style, but a benevolent quality that must be engrafted in all forms and styles of leadership. I have embraced this call. This journey has been humbling. I never feel I have “arrived.” I approach every task and assignment as an opportunity to serve others. While I can lead using other styles, I am a hard-wired

Hofmeyr

Yvonne Mkefa

From Xennial to Zennial: Two Lawyers, One Journey of Growth and Grounding

Cliffe

Dekker Hofmeyr’s NASTASCHA HARDUTH , director – Dispute Resolution and head –Corporate Debt, Turnaround & Restructuring, and TEBELLO MOSOEU , senior associate in the same team, reflect on how their generational differences shape their experiences in the legal profession. One a Xennial, the other a Zennial, both navigating legacy, leadership and what it means to grow while staying grounded

As women in law, the career journey is shaped not only by matters argued or contracts drafted, but rather by the moments that put you to the test, the mentors that lift you up, and the values that keep you grounded.

Q: Tebello, what drew you to the insolvency and restructuring profession?

Tebello: Early in my career, I worked with a director focused on insolvency. I noticed that we often came in too late –when companies were already distressed and disputes had escalated. That made me realise the value of earlier intervention, which helped me pivot more towards restructuring.

profession and continue to do so even now. As with many others, this profession really chose me rather than the other way around.

Q: Can you both share a memorable experience that shaped your approach?

Q: Nastascha, did the profession find you as well?

Nastascha: Absolutely. I started my articles in 2008 in an insolvency practice during the global nancial crisis. Work slowed down quite a bit during my commercial rotation in 2009 and when I was retained as an associate, I chose to return to insolvency practice. And then, business rescue was introduced just as the 2008 Companies Act took effect in 2011. You can say that I evolved with the

Nastascha: Early on, walking to court I was confronted by a vagrant who tried to grab and kiss me, which was really unsettling. However, it taught me a big lesson: con dence is key. I decided to walk with con dence and purpose after that, and it changed how I carry myself professionally (and, I haven’t been accosted by anyone since then). More recently, being involved in restructuring an airline and hearing from a stakeholder how I helped buy time and preserve jobs gave me real meaning and purpose in this work.

Tebello: I was involved in winding up a mutual bank and that, of course, required us to make recoveries in terms of the bank’s debt book. Given the various

“I HOPE WE MOVE TOWARDS PROACTIVE RESTRUCTURING WITH REGULAR FINANCIAL HEALTH CHECKS TO AVOID CRISES.”

– TEBELLO MOSOEU

Tebello Mosoeu

corporate entities that held accounts with the bank, it really showed me in a very short space of time the different forms of recoveries and their applicability to various scenarios.

Q: What trends do you see shaping the insolvency and restructuring field?

Tebello: Generative arti cial intelligence is a big one that is being incorporated into most industries, and I think its application to insolvency and restructuring could be quite exciting. It could help with data analytics and early distress detection, giving companies more runway to get themselves out of nancial trouble. I hope we move towards proactive restructuring with regular nancial health checks to avoid crises.

Nastascha: The future of this eld is also shaped by economic cycles. However, one must bear in mind that mismanagement of companies can happen in good times and bad. During economic downturns, there may be a greater volume of cases, but quality restructurings tend to be better during economic upturns due to more available capital.

“THE FUTURE OF THIS FIELD IS ALSO SHAPED BY ECONOMIC CYCLES. HOWEVER, ONE MUST BEAR IN MIND THAT MISMANAGEMENT OF COMPANIES CAN HAPPEN IN GOOD TIMES AND BAD.”

– NASTASCHA HARDUTH

Q: What advice do you have for aspiring insolvency and restructuring professionals?

Tebello: Stay informed by reading industry publications, attending conferences, and especially networking. Joining professional associations like SARIPA or the TMA can also be invaluable for growth.

Nastascha: Tebello is quite right –organisations like SARIPA and TMA don’t only give you access to formal education through accredited courses, but you can also learn a lot from their members who share their struggles and triumphs. Also, nd a mentor who will guide you and

sponsors who will promote you when you are not in the room. Lastly and probably most importantly, nd meaning in what you do.

THE EVOLVING FACE OF INSOLVENCY AND RESTRUCTURING LAW

Q: How do you see the future of the profession?

Together, Nastascha and Tebello embody the evolving face of insolvency and restructuring law – deep expertise with fresh perspectives. Their stories reveal that success in this demanding eld is about more than legal acumen; it’s about resilience, empathy, continuous learning and the courage to lead through change.

as regulations and economic

Tebello: I think we will see the greater use of technology, a stronger focus on sustainability, and far more cross-border collaboration. Professionals will need to be agile and adaptable as regulations and economic environments evolve.

rescue. Unfortunately, I am also seeing far too many companies

Nastascha: While I agree with Tebello, I am also seeing a trend towards informal turnarounds (achieved by means of nancial and/ or operational restructuring) and away from formal processes like business rescue. Unfortunately, I am also seeing far too many companies going into liquidation that could have been saved through early intervention and a process like business rescue. Compromises in terms of section 155 of the Companies Act are underutilised, and I look forward to seeing if there will be an uptick in this area in the future.

For

Nastascha Harduth

THE ARCHITECTS OF SUSTAINABLE BUSINESS

As businesses across the globe shift toward sustainability, one of the most impactful, yet often underacknowledged, drivers of this change is the leadership of women. We are shaping strategy, embedding environmental, social and governance (ESG) principles into operations, and fostering workplace cultures grounded in inclusion, ethics and resilience. Our work is not just helping companies meet sustainability goals, it’s rede ning what sustainable success means.

The role I play within my organisation, alongside many other female legal professionals, illustrates that women are not just contributors to sustainable business; we are the architects.

REIMAGINING LEGAL CAREERS

Why women are key to sustainable business: linking gender equity with resilience and longevity.

By CALINKA MURRAY , Practice Development director at Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr

From a young age, I knew I wanted to pursue law. The ideal of doing what’s right and ensuring fairness deeply resonated with me. I started my career as a dispute resolution lawyer, but soon realised I was drawn toward building systems that support lawyers – especially junior ones –in more meaningful, lasting ways.

That realisation led me to a professional support lawyer role, and later, to complete a management development programme at the Gordon Institute of Business Science, equipping me with skills in operations, nance, innovation and strategy. Today, as a practice development director, I, among other things, lead transformation in one of my rm’s largest teams, helping shape the future of legal practice.

It hasn’t always been easy. Career paths are in uenced by many external factors. However, staying true to my values – prioritising growth and ful lment –has helped me chart a purposeful and sustainable career.

PEOPLE FIRST: MENTORSHIP AND INCLUSION

Sustainability is not just about climate and compliance; it’s also about people. A core part of my role is mentoring junior lawyers and building inclusive, supportive environments where these individuals can thrive. I’ve seen many women succeed in corporate legal practice, though few would say it was easy. The progress we’ve made is built on the efforts of those who came before us.

That’s why mentorship and advocacy remain essential. We all have a responsibility to be the change, supporting one another, opening doors and laying the foundation for future leaders.

ALIGNING LEGAL PRACTICE WITH ESG

Women across the legal profession in South Africa are leading ESG integration, structuring sustainable nance deals, driving climate risk disclosure and embedding ethics into business operations. My role focuses on aligning practice development with these goals: designing systems, processes and tools that re ect long-term thinking, social impact, commercial excellence and future-proo ng young individuals.

It’s not always smooth. Some innovations take time to prove their value. But in a rm like CDH, where agility is encouraged, I’ve learned that trial, error and persistence are part of driving meaningful change.

HIGH-PERFORMING, INCLUSIVE WORKPLACES

Inclusion fuels high performance. I strive to build a culture of openness, collaboration and knowledge sharing. Diverse teams where people feel safe to contribute consistently deliver better outcomes. Sustainability and inclusion aren’t separate goals; they reinforce each other.

Flexibility has also been key. As work models shift, I encourage people to de ne what balance looks like for them and communicate it clearly. This creates healthier engagement and more equitable, manageable work environments.

WOMEN AT THE CORE OF CHANGE

Women are not just supporting the sustainability movement; we’re leading it. Through mentorship, strategy, innovation and inclusive leadership, we are building businesses that are both principled and pro table.

The future of work and sustainability demands more than technical solutions. It requires people, especially women, who lead with courage, empathy and vision. For those of us who’ve taken a nontraditional legal path, the message is clear: we are not just adapting to the future of business – we are shaping it.

Calinka Murray

WOMEN BREAKING GROUND

ILDA DOS SANTOS , director

– Corporate & Commercial and Oil & Gas sector at Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr’s Namibia

office, discusses how women are carving a path in the Namibian oil and gas sector

When I began my career at the Legal Assistance Centre in 2001, I was driven by a desire to make a meaningful contribution to society. Over two decades later, having worked across public interest law, Namibia’s state-owned energy sector and now private practice, I remain deeply committed to helping organisations navigate complex challenges in a way that is legally sound, commercially viable and, increasingly, socially responsible.

I’VE

SEEN HOW WOMEN BRING DISTINCT INSIGHTS TO CORPORATE STRATEGY, GOVERNANCE AND RISK, PARTICULARLY IN SECTORS LIKE OIL AND GAS, WHERE LONG-TERM THINKING IS CRITICAL.

These experiences have shaped how I now view inclusion and leadership. Gender equity is about more than female representation; it’s how we build institutions, support people and make space for under-represented voices in decision-making. In my career, I’ve seen how women bring distinct insights to corporate strategy, governance and risk, particularly in sectors like oil and gas, where long-term thinking is critical.

One of my proudest achievements was earning a master’s degree in oil and gas law from the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. This academic foundation supported my work in the Namibian and Angolan upstream oil and gas markets as well as downstream and midstream sectors, where I advised on acquisitions and disposal of acreage through farmout processes, supply, distribution, storage and handling transactions, and participated in contract negotiations.

SHARING KNOWLEDGE, BUILDING CAPACITY

While progress has been made in Namibia, with more women now occupying senior roles in the legal profession, systemic barriers remain. Gender bias still creeps into client or stakeholder meetings, where male colleagues are sometimes assumed to be the leads by default.

To shift the status quo, we need greater allyship from our male counterparts –both by deliberately creating space for women to lead and recognising the value of diverse perspectives in decisionmaking. Effective support means not only giving women a seat at the table, but also considering them for leadership roles on equal footing and acknowledging their skills and contributions.

Looking ahead, I’m focused on broadening my exposure to more international upstream, midstream and downstream transactions. The legal challenges in cross-border oil and gas deals are evolving, particularly with growing expectations around ESG (environmental, social and governance) compliance. Women lawyers have an important role to play here – not just as legal technicians, but as strategic partners who can bridge commercial imperatives with broader social goals.

To young women pursuing a career in law, I would offer this advice: be resilient, assertive, focused and committed. Never stop learning. Reach out to experienced professionals to grow your knowledge and build your capabilities. And, most importantly, know that your voice and contribution matter. Women are not just part of that future – we are helping to shape it.

As a woman in Namibia’s legal sector, my journey has required assertiveness, resilience and a continuous willingness to learn. When I joined the National Petroleum Corporation of Namibia (NAMCOR) as legal manager, I was one of the few women operating at a senior level in a male-dominated industry. Being heard, especially in technical negotiations and high-stakes meetings, often meant having to prove my credibility repeatedly. I quickly learned to stand my ground, prepare meticulously and lead with competence and composure.

What made these experiences especially rewarding was the opportunity to build capacity in others, particularly young women in the legal and energy sectors.

meant having to prove my meticulously

During my time at NAMCOR, I supervised several interns and employees and embedded knowledge transfer into our processes and corporate and commercial, particularly in the oil and gas sector. For me, true mentorship isn’t about handholding; it’s about setting high standards, offering support and trusting others to rise to the challenge.

Ilda Dos Santos

Advancing gender parity in international arbitration

While the legal profession has long been marked by under-representation of women, particularly at senior levels, international arbitration presents a more optimistic picture, writes VERONICA CONNOLLY , senior associate – Dispute Resolution at Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr

From Asia to America to Africa, women occupy some of the most senior leadership roles at international arbitral institutions:

•Singapore International Arbitration Centre: both the CEO and COO are women, and over half of the secretariat is female.

•Judicial Arbitration and Mediation Services (JAMS), US: led by a female CEO and president.

•International Chamber of Commerce: presided over by a woman, with women comprising more than half of the vice presidents.

•Stockholm Chamber of Commerce (SCC) and Arbitration Foundation of Southern Africa: both led by female secretary-generals.

These examples suggest that, at the institutional level, gender parity is not merely aspirational, but is increasingly the norm. In that respect, the gap might be considered “closed”, although caution should always be exercised to ensure equal representation remains.

ARBITRATOR APPOINTMENTS: A MIXED PICTURE

Representation of women on arbitral tribunals reveals a more uneven story. Institutional appointments re ect their leadership values, with a consistently high percentage of women being selected:

the story. The majority of appointments are made not by institutions, but by parties or co-arbitrators. In those instances, the proportion of women appointed is signi cantly lower:

•Female arbitrators were appointed by parties in LCIA arbitrations in just 22 per cent of cases in 2020, a proportion that had not improved by 2023 when it was just 21 per cent.

•The percentage of female arbitrators appointed by parties in SCC arbitrations has remained low and static over the last few years, uctuating between 27 and 31 per cent from 2022 to 2024.

•In 2024, only three per cent of appointments in proceedings before the Cairo Regional Centre for International Commercial Arbitration were women.

CLOSING THE GAP: ACCOUNTABILITY AND ACTION

To address the disparity between appointments made by institutions and those made by parties and co-arbitrators, it’s important to understand why the gap persists.

visibility in sectors where the profession has historically been male-dominated. Encouragingly, arbitration practitioners have launched signi cant initiatives to address this disparity. This year marks the 10-year anniversary of the Equal Representation in Arbitration Pledge being drawn up. With an aim to achieve fair representation of women on arbitral tribunals, it now has almost 6 000 organisational and individual signatories across six continents. Transparency initiatives, such as institutions publishing diversity data, are also driving accountability and accelerating change. There is much to celebrate in the strides international arbitration has made toward gender equality, particularly at the institutional level. However the persistent disparities in re ecting equality in arbitrator appointments demonstrate that real change depends on greater engagement on the issue by parties, their legal advisers and arbitral institutions. Maintaining progress requires ongoing attention to diversity, not just in gender, but also in race, age and background.

VISIT WEBSITE

•London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA): appointment of women by the LCIA court has remained high and stable, uctuating between 43 to 48 per cent from 2018 to 2023.

• London 48 per cent from 2018 to 2023.

• SCC: appointed women in ect reputation and informal the

•SCC: appointed women in 57 per cent of cases in 2024. However, appointments by institutions are only part of

One hypothesis is that appointments by and at institutions are subject to transparent processes with clear diversity policies and organisational accountability. By contrast, party appointment of arbitrators is governed by the discretion of parties (and their legal advisors), which can re ect unconscious bias or reliance on “safe” familiar names based on personal reputation and informal networks. This can lead to the overselection of male arbitrators who may have higher

information: www.cliffedekkerhofmeyr.com

Veronica Connolly

CHANGES, CHALLENGES AND COURAGE

Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr’s BELINDA SCRIBA , director – Dispute Resolution, recounts her experiences in a not-always smooth sailing career journey

When choosing the legal profession as your career choice – no matter your ethnicity, gender or culture – you knew (and know) it was (and is) going to be gruelling (academically and in practice). Coupled with that I was choosing to take the path in the 1990s. What that meant, given South Africa’s history, was that I was naively gearing myself up to tackle a white-male-dominated industry, hesitant to accept change of whatever nature. Add to that the big, no-nonsense “personalities” for which law was (and is) renowned, a tradition of teaching by breaking you down. If you were different from the traditional norm, it was always, by the very nature of the circumstances, going to be brutal. My saving graces were these – I have been blessed by my Maker to be a Gen Xer, I had wonderful mentors, I found an awesome partner in life, and (albeit slower than we would like) times were primed to change and start breaking norms, where differences are embraced and encouraged and bad behaviour is intolerable no matter your status.

Has it been a smooth journey? Of course not. However, the dif culties make you stronger and appreciate where your journey has landed you (even if you are still on it).

CHANGING OF THE GUARD

The reason being Gen X is relevant is because we are the generation that has been willing participants in important, groundbreaking transitions. We embrace arti cial intelligence assistance, yet we also remember receiving faxes (and sometimes miss “those days”). We were afraid to push back lest the dire consequences, but now encourage, support and learn from the subsequent generations who refuse to accept that old “norms”. The advantage

THE PROGRESS WE SEE TODAY IS THE RESULT OF GENERATIONS OF WOMEN WHO BROKE BARRIERS AND REDEFINED LEADERSHIP IN THE LEGAL FIELD.

of this? The old ways made us resilient and adaptable, the new ways allow us to be better mentors and teachers and, yes, lawyers. The “old guard” has either moved on or learned to change (perhaps reluctantly at rst, but for the most part, while it has been and continues to be a challenging expedition to change, it is happening).

Boy, have I been through the “wringer” (I challenge you to nd someone in this profession who has not). Articles, personality clashes, being told that having a baby was a death knell to my career, corporate politics, unreasonable clients and malicious opponents. All of which, at some point, make you question whether it is worth it or whether you are worthy of it. However, and I cannot emphasise this enough, most importantly, people who have your back, who teach you and guide you, who pick you up when you are down, who take you under their wing when you come back from

maternity leave, who ght your battles for you when you cannot, who let you cry with them when you have lost some battles (and believe me there have been some epic losses) are what gets you through when being resilient and adaptable is not enough. I have been blessed with these people (of both genders) throughout my entire journey.

In a nutshell, how I got from there to here? God, tenacity, an unwillingness to just “die”, a willingness to adapt a nd amazing mentors (professional and personal).

I can honestly say that the best part about being a woman when I rst started practising (and sometimes still today) is that your opponents underestimated you, taking your gender and timidness for weakness. Their mistake. The worst part is that your colleagues had the same attitude.

My goal for the future? To be as awesome a mentor as I have had in my journey, to continue ghting the good ght for clients, colleagues and juniors alike and to have the courage to continue pushing for change in one of the oldest professions.

Belinda Scriba

THE WEIGHT OF THE BLAZER

Using a blazer as a metaphor for responsibility, DEBORAH SESE , senior associate – Corporate & Commercial at Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr’s Kenyan office, reflects on her career, challenges and choices

As a career woman, I have to choose the weight I carry every day, every minute and every second, but let’s go back a few years for context. I am an ordinary female, born and raised in Nakuru, Kenya. My mother, an ordinary woman from a not-so-well-off background who is a successful registered nurse, always impressed upon me that as a female, I must beat extra odds compared to male counterparts to achieve what I wanted in life. My mother has been a feminist for as long as I can recollect. When I asked her why university-entry grades in Kenya were lower for girls at the time, she explained that girls always start at a disadvantage – before they go to school, before they do their homework, they have to take care of some things, based on both nature and society’s gender role assignment. My father has been a great supporter of women empowerment and always afforded my brother, sister and me equal opportunities. He has also always supported his female siblings and contributed to their elevation in society.

While my parents’ efforts look like ordinary stories, they are worth telling to lightly demonstrate the role of parents in the choices their daughters make.

you believe is right, to take your place at the table and to not drop the ball when it comes to your family.

As a woman in legal practice, I have bene tted from good mentorship, which helped me beat many of the odds and enjoy my career as a family woman. My mentor, who was my supervisor from when I started my career, was very supportive, and when I communicated my intention to change employers, opened the door and wished me the best.

However, I have had to contend with the guilt of ambition, the consequences of the change in routine on my young family and the guilt of what could have been had I stayed on a bit longer, but I have recently understood the true meaning of change and hard choices. Surprisingly, male colleagues at my career level who have made such choices have not suffered from this guilt at any point. This realisation (and acceptance) informs my message to the ambitious girl/woman reading this –go for what you want, and it is okay to

THE CHOICES YOU MAKE EVERY DAY AFFECT HOW

HEAVY YOUR BLAZER IS AND HOW LONG YOU CAN KEEP WEARING IT.

battle with the doubt of consequences even as you make tough (but wise and informed) decisions.

CHOICES AND CHALLENGES

As a child, I worked extra hard in school, understanding that I had no room for failure. I set high goals for myself and believed I could achieve anything I put my mind to. Fast-forward to joining the legal career, in a eld of practice that can be quite competitive and consuming. Now in my sixth year of practice as a mergers and acquisitions and private equity lawyer, the blazer gets heavier by the day. The blazer is the choice to show up every day, to choose ambition over loyalty, to stand up for what

Your nature as a human being is a nurturer; this means you will battle with the longing to nurture society, work relationships and loyalty. You, however, need to be conscious of your goals and what you have to do, and go for it with grace and good coping mechanisms to wear a blazer that weighs differently every day. In short, nurture yourself rst. Most importantly, you can reduce this weight by choosing wisely –a good employer, good friends, a good partner and a positive attitude. The choices you make every day affect how heavy your blazer is and how long you can keep wearing it.

Deborah Sese

PREPAREDNESS AND OPPORTUNITY

Reflections on a career filled with aspirations, possibilities, challenges

and achievements.

By SHEILLA MOKAYA , associate – Corporate & Commercial at Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr’s

Kenyan office

This being my birthday month, I re ect on aspirations, achievements, disappointments, and uncertainties, all of which are important for a balanced world view. Successes encourage us for the possibilities of the future and disappointments remind us that we are human and should be gracious to ourselves and others.

DO

NOT WAIT TO TICK ALL THE BOXES BEFORE SEIZING AN OPPORTUNITY AS THAT

I gured that the combination of a law degree, banking knowledge and my accounting quali cation would be a good t for transaction advisory. As such, I began the journey that has led me to my current position at Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr.

As the rst-born child of my mother, a tailor, and my father, a welder, life has been a rollercoaster with many episodes in my childhood that have shaped my viewpoints. My “nomadic” experience, due to economic circumstances, saw me living in several towns in Kenya. It was very challenging to live away from home, and I quickly realised that if I wanted to have a better life, I needed to put in a lot of effort. Knowing what I know today, I wonder how I survived, but such are the Lord’s works – inexplicable. Would they be miracles if they could be explained? This upbringing instilled in me a sense of discipline and mental fortitude that has guided me so far. My parents’ love, belief and tenacity to ensure we received a quality education even in dif cult circumstances is something I will forever be grateful for.

WILL LIMIT YOU. THE SUREST WAY TO FAIL IS NOT TO TRY.

BE OPEN TO OPPORTUNITY AND BE PREPARED

So, what are the lessons here? Firstly, give yourself a chance. Do not wait to tick all the boxes before seizing an opportunity as that will limit you. The surest way to fail is not to try. Open yourself up to the chance and learn while at it. Always ask for help and seize opportunities to showcase your abilities, rather than waiting for them to be presented to you. Secondly, pursue excellence. Strive to be and give your best in all that you do. Aim for the gold standard. Choose to be honest, to be dependable and to do things right. Always aim for the best. Thirdly, be strategic and prepare for the opportunities. While waiting for the next big thing, improve yourself, acquire new skills and learn a new art. Opportunity should meet preparedness.

and set pathways for one to accomplish more after secondary school. This was particularly critical for me as no one in my paternal home had gone beyond secondary school, and everyone had almost accepted that secondary education was the ceiling for us all. Fast-forward and I excelled in the national high school exams and was admitted to a law degree programme with government sponsorship. After admission to the bar, I worked as a legal counsel for a local bank and later obtained an accounting quali cation.

national examination for primary education and secured a place at one of the top

magical key,

While at Rusinga Island, I sat the nal national examination for primary education and secured a place at one of the top national schools in the country, Alliance Girls High School, which would test my resilience and later open up limitless possibilities. Like the proverbial Zelda’s magical key, this would be my key to unlocking many doors. It was a realisation that education can transform lives

Zelda’s

Sheilla Mokaya

LIFTING AS WE RISE

Cliffe

Women constitute roughly 47 per cent of South Africa’s overall labour force. Yet, despite their overall presence, women remain signi cantly under-represented in senior management and leadership positions. Surveys conducted in 2024 revealed that women made up just 36 per cent of board seats in JSE Top 40 companies and only 23 per cent of executive management positions. While women are undoubtedly ambitious and aspire to career growth, they continue to face barriers to entry in advancing to higher-level positions. These barriers are varied in nature, but across industry and discipline, a common thread that cuts across these spaces is the absence of dedicated mentorship spaces for women on the rise, leaving a gap in women’s ability to aspire and inspire.

The value women in leadership positions add to business is undeniable. Female leaders are on average more trusted than their male counterparts, create spaces for collaboration and show empathy and compassion in engaging with their juniors and peers. Women in C-suite positions can offer unique and diverse perspectives, positively in uencing a business’s culture and environment, leading to increased productivity and pro t.

So, if this is what the data is showing, why do women still face these barriers to to entry, and

Dekker Hofmeyr’s BRIGITTA MANGALE , director – Pro Bono and Human Rights, discusses the importance of women mentoring women in law and business

why don’t we see more examples of women lifting as they rise, creating spaces for female juniors to thrive and excel, decreasing the need for these female juniors to have to reinvent the proverbial transformation wheel?

AN ONGOING FIGHT FOR EQUALITY

In my experience, the issue isn’t as straightforward as one would think. For as long as we can all remember, women have had to ght tooth and nail for a seat at the table, and then have had to continue to ght to be heard once seated at the table. In advancing my career, I have found that, on average, it was my male seniors who freely created mentorship spaces and dedicated themselves to my growth, while my female seniors seemed preoccupied. It was only as I began to grow in seniority that I began to understand this preoccupation: role, often, doesn’t equate to respect.

Most reputable businesses have internal transformation targets that require a certain number of women to ll positions at various levels within the company. However, unfortunately, most businesses simply leave it at that and

don’t take the further steps necessary to ensure their company moves towards true empowerment and transformation, not merely tick-box gestures. Structures are not put in place to allow women the choice to advance in their careers and simultaneously nurture their families, to deal with workplace harassment that doesn’t magically disappear when women rise through the ranks or break down the barrier to entry to the ever-elusive boys’ club. Instead, when women rise to power in title, they still have to ght to earn the respect of their male counterparts and for their voices to be heard.

The ght is not over when women are promoted; they must simply turn their attention to a different ght, leaving little room for attention to mentorship and empowerment. Businesses can better support women’s ability to create mentorship spaces by ensuring women in leadership positions are properly and meaningfully supported in their roles, allowing them to not only turn their attention to mentoring juniors, but also giving them the space to ourish and positively contribute to pro tability and culture. Women mentoring women is critical to a business’s success, but it can only be achieved through collective action and collaboration.

Brigitta Mangale

WHEN OPPORTUNITY KNOCKS

TESSA BREWIS, director – Banking, Finance & Projects and joint head – Projects & Energy at Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr, writes that sometimes, the most rewarding careers begin not with a plan, but with an unexpected opportunity

Working as a lawyer in a large law rm for over two decades, with more than 18 years at my current rm, Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr, has been both demanding and deeply rewarding. Much of my work has focused on the corporate and commercial aspects of projects, particularly in the renewable energy space. This has given me the opportunity to contribute, in a small but meaningful way, to sustainability – something that aligns closely with my personal values and brings added purpose to my professional life. Over the years, one of the key lessons I’ve learned is the value of gaining broad experience and a solid foundation before narrowing your focus. To young professionals, especially women entering the legal eld, I often say: don’t be in a hurry to specialise. Be open to unexpected paths, even if they don’t align perfectly with your studies or early career plans.

SHIFTING DIRECTION

Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPPP), which created space for new practice areas to emerge.

The early stages of REIPPPP felt like a formative time in the sector. We worked to build teams with experience in project nance, corporate, construction, environmental, property law and economic development. Collaborating with international colleagues – many of whom were generous with their insights – helped us grow and develop quickly. Later my mergers and acquistions background also meant I became involved in some of the early secondary market transactions where clients sold stakes in operational renewable energy projects.

This kind of work also touches on broader themes – sustainability, inclusion and social impact – all of which are at the heart of the G20’s Sustainable Development Goals. It also serves as a reminder that women can lead and thrive, building expertise and creating space for others along the way. That, to me, is a powerful form of progress.

My personal journey re ects this. I started out concentrating on corporate and commercial law, with no plans to work in the energy sector. Then in 2009, when a colleague emigrated, I was asked to take over one of his matters and assist with a lease amendment for a wind farm. As a quali ed notary and conveyancer, the request made sense. At the time, I had no background in energy law and hadn’t given much thought to the sector, but that rst matter sparked an interest. One instruction led to another, and soon thereafter, South Africa launched the Renewable Energy

What continues to motivate me is the sense that our work contributes to something larger than any one deal. While legal work is often driven by business needs, I believe there’s real value in playing even a small part in helping South Africa shift toward cleaner, more sustainable energy sources.

I hope more women feel encouraged to explore emerging elds like this where legal skills can align with meaningful change. Sometimes, the most rewarding careers begin not with a plan, but with an unexpected opportunity.

more sustainable

Tessa Brewis

MENTORSHIP AND COLLECTIVE UPLIFTMENT

KUDA CHIMEDZA , director – Banking, Finance & Projects at Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr, shares real stories from mentorship relationships that have changed the trajectory of careers and lives

The year 2023 marked 100 years of women meaningfully participating in the legal sector. Yet, two years later, I still nd myself in meetings where I am the only woman (of

colour) present. There is still work to be done in opening doors for women. That said, I’ve been fortunate to build a career that illustrates how mentorship can be a powerful ladder for women to enter, engage and rise in law.

My introduction to mentorship was through my faith. At rst, my quiet demeanour and, if I’m being honest, lack of con dence (at the time), led to months passing without me approaching prospective mentors. I had not settled on a career, or anything really, until a church member offered to mentor me. She encouraged me to create a structured action plan for the next few years and this forced me to re ect and strategise. Dividing my life into categories, and speci cally planning for each of them, was the rst step to the career I now enjoy. She was brilliant and remained my mentor until her passing. Since she wasn’t a lawyer herself, there was a gap from a career perspective. So, I ended up having more than one mentor. Over the years, this has offered relief to mentors who generously offered their help, but didn’t have the capacity to be my “be-all-and-end-all”.

I’VE BEEN FORTUNATE TO BUILD A CAREER THAT ILLUSTRATES HOW MENTORSHIP CAN BE A POWERFUL LADDER FOR WOMEN TO ENTER, ENGAGE AND RISE IN LAW.

As the rst person in my family to pursue law, I was navigating unfamiliar territory. I met my second mentor through a law school mentorship programme. She taught me the prerequisites for a career in law: identifying strengths and weaknesses, dealing with imposter syndrome and other matters that would have been stumbling blocks in my career. Her guidance helped me to navigate law school and secure articles at one of the top rms in the country. She continues to provide great support as I grow in my career.

ALL TYPES OF MENTORS

As a candidate attorney, I was allocated to a director who became a technical skills mentor. She walked me through key sections of legislation, line by line, ensuring that I truly understood our work. She sparked an interest so deep that I eventually completed my master’s degree with research on a question I had asked during one of our training sessions. She was one of many colleagues who invested in ensuring I had the technical training required to excel. I have also been informally mentored by other colleagues who modelled what a successful legal career can look like for a woman of colour. My rm’s former chairperson is a great example. She demonstrated how to conduct oneself in a corporate environment, including dressing appropriately for a legal career. Although I did not work directly with her, she regularly checked on my upskilling and reminded me to pursue work-life balance. Although there was no structured mentorship relationship, I learnt volumes from observing and chatting with her.

Informal mentors have also been impactful advocates who have changed the course of my career. There were no

regular meetings to discuss career steps, but they became my sponsors in rooms I wasn’t in. Hard work and ambition could only take me so far. What moved the needle at key milestones was having people who advocated for me in my absence.

Mentorship has also come from unexpected sources. For example, a client who was a senior partner at another rm, now in-house counsel, provided me with invaluable advice on, among other things, business development. At this stage of my career, this guidance could not have been better timed.

I’ve been privileged to have many people invest in my growth. My career is evidence of the contributions of the women who brought me along as they rose and the men who choose to be allies in the upliftment of women in law.

Kuda Chimedza

THE PEARL THAT BROKE ITS SHELL

In December 2014, a 19-year-old law student, experiencing Sandton for the rst time, carried the hope of a future that was in the hands of an interviewer at one of the big ve law rms.

What did not occur to me at that time was that more than my hand-me-down suit, I remained clothed in the circumstances I had temporarily left behind, which would inform my performance in this new world. I was uncertain, timid and lacking in con dence. My background was rearing its head in a different environment. From that day and many days thereafter, the anthem –she needs to break out of her shell – rang.

In her book, The Pearl that Broke Its Shell, Nadia Hashimi explores the ancient Afghan tradition of bacha posh, where a girl lives and behaves as a boy to enable her to behave more freely and effectively provide for her family. Essentially, the girl assumes a different shell to t into a particular environment and achieve a particular objective.