秋は夕暮れ Aki WA Yuugure

Autumn, the evening)

tWilight PortrAits

CeCeliA levin are a residue of thought. —Miya Ando

Art is thinking and artworks“ ”

Howoften do we turn our gaze toward the everchanging skies … to its sunrises… its sunsets…the stars and planets… and its meandering clouds? We admire them for their beauty; are captivated by their mystery; and humbled by our place in this infinite universe and our evanescent existence. It is understandable that from time immemorial they have been envisioned as the celestial realm. Through the skies we recognize nature’s great powers and— in our current times—also recognize its fragility. Skies are the keepers of time: announcing the

rhythmic pattern of the seasons and punctuating the transitions of each day. Each of these temporal states ignites a differing set of physical sensations and an immeasurable array of deep emotional responses—including remembrances of people and events in our lives—and throughout the ages our creative impulses have compelled us to capture these diurnal and seasonal manifestations of nature in words, music, art and dance. Among all others, it is the Japanese veneration of the natural world that is primordial and transcendent, sacred and sublime.

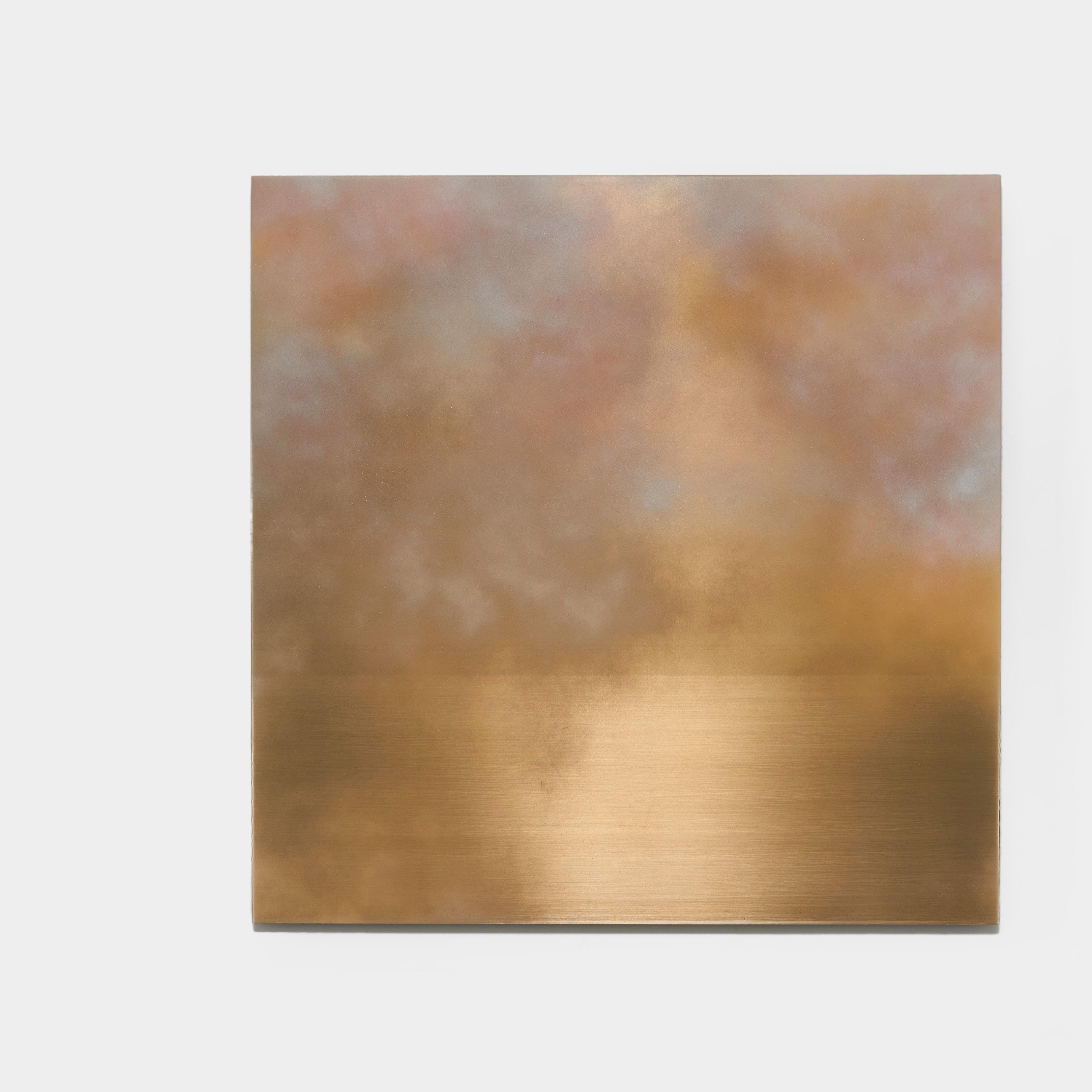

Tasogare (Twilight) June 6 2022 8:26 pm (detail), 2022 ink, mica, pure micronized silver, resin and urethane on aluminum composite, 50 x 50 inches/127 x 127 cm

Throughout her artistic practice the artist Miya Ando has drawn from her Japanese origins and legacy. Her art, however, extends beyond the emulation of associated imagery or methods, or the instillment of Japan’s cultural traditions and philosophical systems. Her works of art are birthed from a bond that is more profound and much deeper—embodied in her heart, mind and spirit—and through creative responses that are innate and visceral.

The most vital catalysts of Ando’s artistic formation were her descent from a lineage of Bizen sword makers, and her childhood years spent at a Buddhist temple in Okayama where she became attuned to this exceptional Japanese reverence for nature and the spiritual realm. These were forged into a constant leitmotif in her work: the confluence of the permanent and tangible— represented by the materials she employs— with the conveyance of the most transient and ephemeral phenomena of the natural world. It is fervently and majestically epitomized in her current assemblage of twilight portraits rendered on aluminum composite canvases.

Its title, Aki wa Yuugure (In Autumn, The Evening), reawakens a Japan of more than a millennium ago when these words were originally scribed among the opening phrases of The Pillow Book, a unique literary masterwork presenting an extraordinary window onto this epoch:

In autumn the evenings, when the glittering sun sinks close to the edge of the hills and the crows fly back to their nests in threes and fours and twos; more charming still is a file of wild geese, like specks in the distant sky. When the sun has set, one’s heart is moved by the sound of the wind and the hum of the insects.1

At the time of its creation around the year 1000, Japan was at the height of a four-century-long cultural and artistic efflorescence, centered at its imperial court and emblematic of Yamatodamashii (the Japanese spirit)—a world view that embraced traditional and indigenous Japanese expressivity while rejecting foreign cultural

conventions and forms. The literary arts excelled above all others—especially poetry—and one of the remarkable aspects of this time is the recognizable preeminence of women authors whose works have been preserved for posterity: it is a phenomenon that has never been experienced in any other pre-modern culture or era.

This dramatic societal and cultural transition—the inward turning of Japan—fueled the development of kana, a syllabary—or phonetic—form of writing, and a surge of indigenous poetic forms such as waka (Japanese-style poem). For the aristocratic and courtly women of the era—who were excluded from learning Chinese characters—it was fortuitous, and advanced their vernacular writings, literally known as “by women’s hands” (onnade). Best known among their achievements is The Tale of Genji by Lady Murasaki (c. 978–1014) and The Pillow Book, 2 authored by her courtly contemporary, Sei Shōnagon (c. 966–1025).

The prestigious rise of literature and poetry was coupled with the evolution of the Japanese language into one of great richness and beauty.

It is comprised of great nuances and often intentionally nebulous in its expressiveness: myriad words can be used to define the same phenomenon or object, while a singular term can spark a variety of meanings. It abounds in multivalences, puns, allusions, metaphors, homonyms and the use of repetitions: often significances would only be appreciable to its original readers. However, beyond a bravura use of these aesthetic literary practices, the utmost criterion for an author or poet’s success was the compelling conveyance of human sentiments and the evocation of emotional resonances in a listener or reader. Yet, underlying this great artistic renaissance was the foreboding of its finality; one rooted in the crucial Buddhist principle of impermanence (mujō) and embedded in this religion’s essential teachings on the illusionistic nature of human existence. During the lifetime of Lady Murasaki and Sei Shōnagon, these beliefs especially reverberated, for it was predicted that the end of the Buddhist World of Order was imminent. As this sense of fatality and ephemerality overshadowed their world view, the

Tasogare (Twilight) June 2 2022 8:23 pm, 2022 (detail)

unique qualities of the Japanese language and literature—alongside other meaningful modes of the Japanese essence—were brought into play to express the most profound aesthetic ideal of the era: mono no aware. Typical of the character of the Japanese language, this crucial sensation may be defined by various terms: “pathos,” “empathy,” “a heightened sensitivity,” and “poignancy”: it is seen as a deeply emotional response to each and every phenomenon in

our world and to our experiences, with the essential acknowledgement of the transitory and momentary nature of all things.3

In the summoning of mono no aware, the Japanese exaltation of nature has been integral: nature is employed for its transient and impermanent character as well as used metaphorically for myriad human emotions. In the arts it has been specifically epitomized by the theme of the Four

Seasons. Its ongoing esteem is attested to in the early collections of waka poetry,4 and in the visual arts it was manifested in the development of the genre “four seasons painting” (shiki-e), commonly portrayed on four-panel screens and in scroll paintings.

Of the seasons, it is autumn (aki) that reigns supreme and is regarded as most resonant of mono no aware. While admired for its beauty,

autumn is equally recognized as the shortest and most dramatic of the seasonal transitions. The loss of leaves, shorter days, mists, and rains all tell of the ebbing and waning of nature: they are harbingers of its continuous maturity and annual decline. Autumn’s colorful leaves are a forewarning of a colorless winter to come. Above all else, this season is a reminder of the impermanence of our own existence, of the winding down of our lives to an ultimate ending.

That Sei Shōnagun’s impressions of each of the four seasons was her premier entry in The Pillow Book also suggests the preeminence of this theme. They additionally relate another pivotal convention in Japanese aesthetics: the interconnection and pairing of the seasons with particular times of day. Of the four, it is spring and autumn that are matched with the more paramount moments in a day’s cycle, those that are most temporal and rapidly fleeting: the rising and setting of the sun. The decrescent nature of autumn and twilight, or dusk, are especially kindred and mutually shared: beautifully conjured through the imagery of Sei Shōnagun—and now in the works of Miya Ando.

It is through the depiction of clouds that Ando has created her own visual poetry and evocation of mono no aware; and following in the footsteps of the poets of an earlier Japan, she presents a rich interpretation through a pictorial language permeated with nuance and multivalency.

The intertwining of autumn, twilight and clouds for their common aesthetic implications is a deeply rooted Japanese tradition. Clouds may be seen as

the most fragile of the elements. They are mutable and unpredictable; surprisingly appearing and vanishing and everchanging in their formation, size and texture. They are perpetually in motion, at times offering an impression of wandering aimlessly through the sky. They are ambiguous. They obfuscate: they have the power to obscure. They can rob us of clarity or the ability to see the “complete picture.” For all these reasons, clouds may be viewed as another metaphor for our own ephemeral lives and the uncertainty of our future path.

Ando’s cloud compositions are realized in her hallmark medium—metal. Throughout the expanse of her artistic repertory this earthly element has not only been emblematic of her familial links but also suggestive of the contrast between ancient traditional Japanese craftsmanship and modern metallurgical technology. This current series adds a striking dissonance through the juxtaposition of the most perdurable of elements— associated with strength and permanency—with the softness and ephemerality of the clouds: one accentuated further by the painterly treatment of these forms against the flat metallic surfaces symbolic of the skies.

It was the artist’s intent to elicit this phenomenon with the greatest of precision: each canvas presents an entirely singular and unrepeatable instance. In her enriched interpretation of mono no aware, Ando envisions that one should exalt the temporality of each instant and feel graciously rewarded. Every moment is uniquely experienced and unlike any other and, to the artist, “beauty is sublime due to its ephemerality.”

To achieve a temporal exactitude in the creation of her “portraits of a time of day,” the artist worked from prototypical sketches and photographic images. Matte inks and pigments were employed in her portrayals of the clouds: these were often applied in multiple layers to suggest textures varying from the diaphanous to thick. However, even more so than the conveyance of the clouds’ diverse personalities, it is the transitory and

visceral experience of light at the ending of a day that that is paramount. Light is omnipresent, yet its source is not identified nor suggested. It is never made tangible: resonating with the ideals of Japanese aesthetics, it is only implied. To capture each compelling and momentary experience of a diminishing sunlight–or perhaps an advancing moonlight—Ando brought into play a subtle and nuanced palette of colors and tones ranging from tan, peach, and pink to purple, gray and silver. Darker gradations were used to convey the underbellies of several of the clouds, hinting at their lessened interaction with light. The addition of resin and urethane to the canvases, with their reflective qualities, further enhance the radiancy of each twilight, and the preeminence of light— and nature—are even more greatly epitomized through the application of pure micronized silver and mica to the canvases’ surfaces.

As a result of Ando’s use of materials and processes—combined with her artistic vision— each canvas conjures an emotional response to a specific and not-to-be-repeated moment in time. Each also has the potential to trigger the viewer’s imagination: to imply a wider set of circumstances, or story. The gossamer and

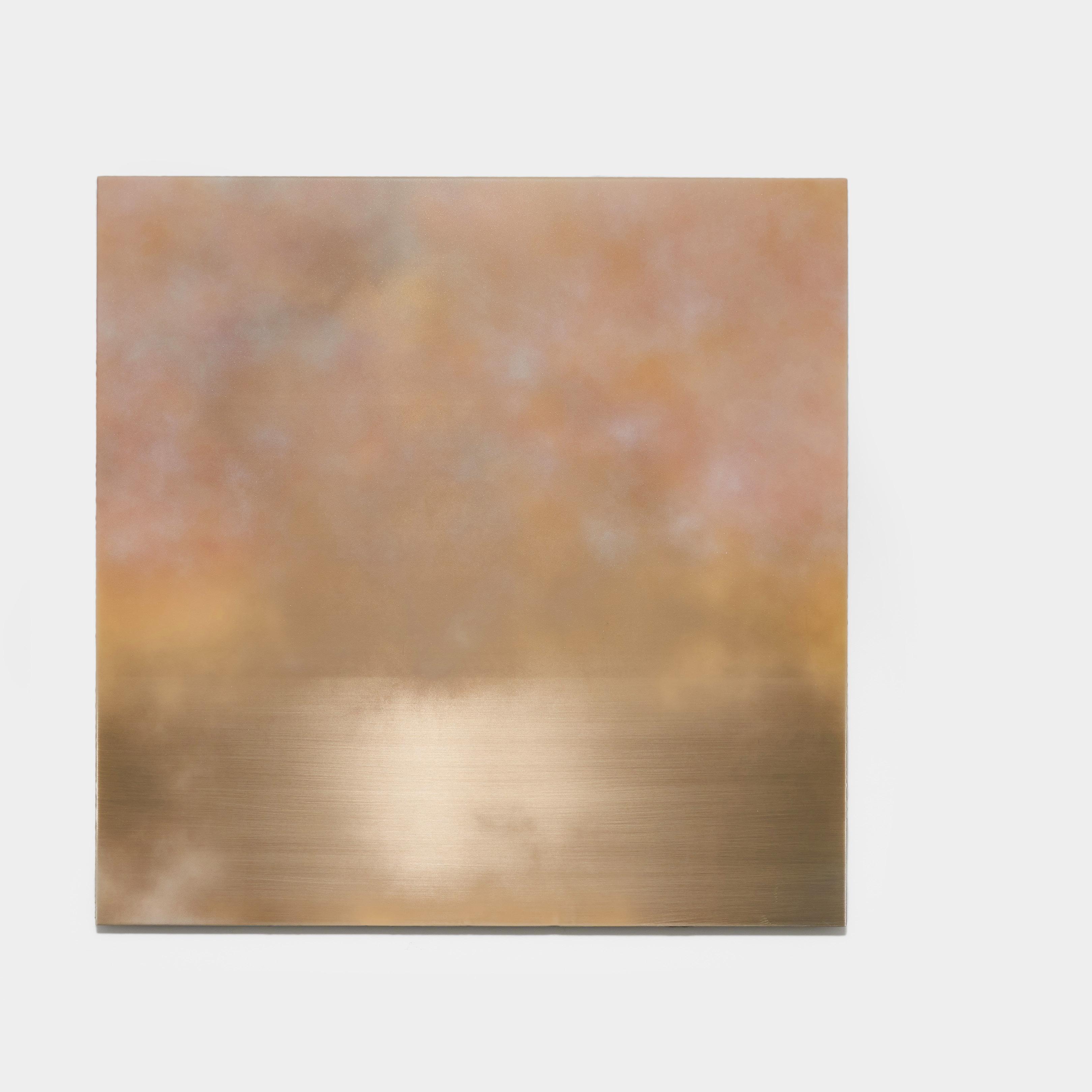

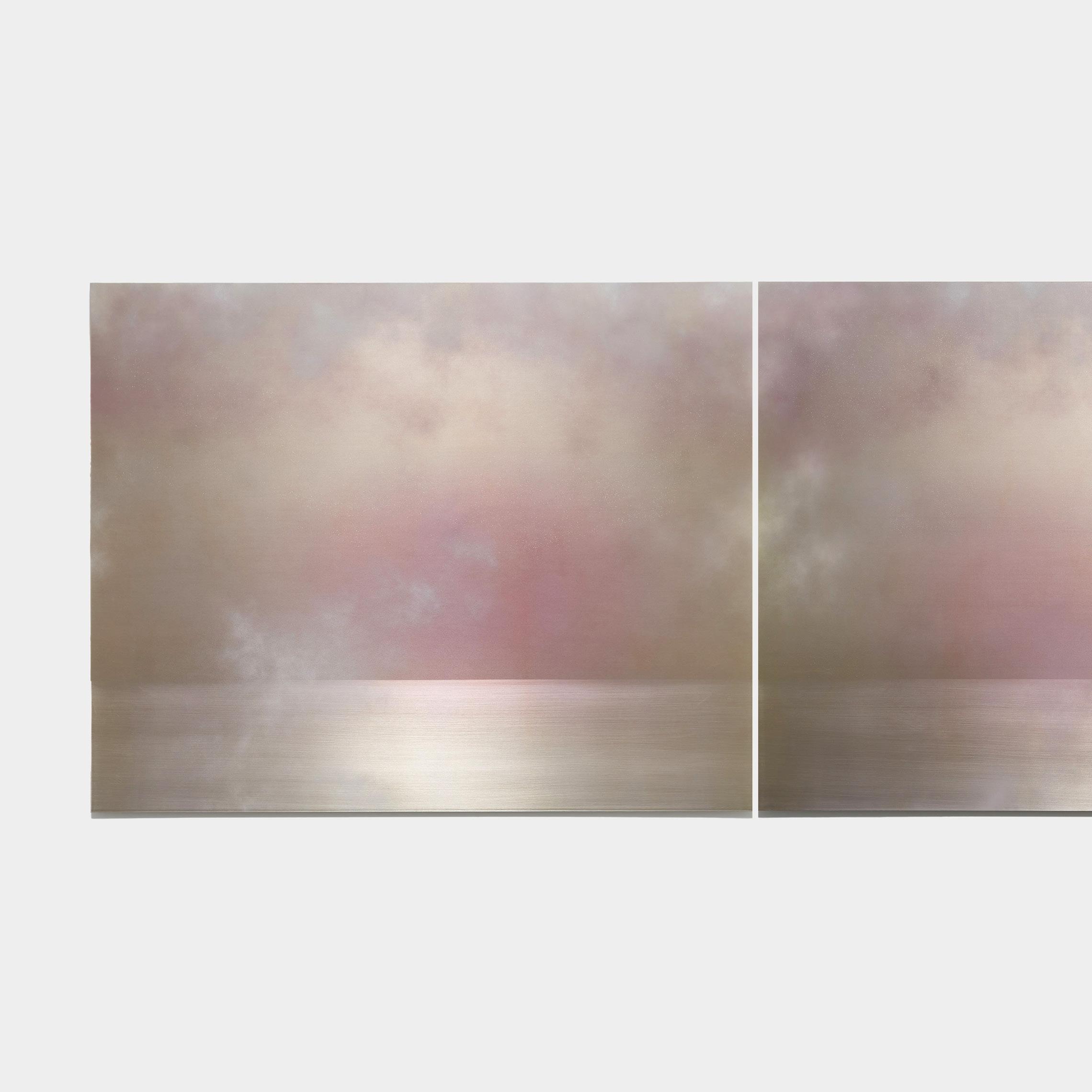

salmon-colored clouds that permeate a lucent sky in Tasogare (Twilight) June 2 2022 8:23 pm and float slowly across the vista may relate the end of a day of peace and calm. In contrast,

Tasogare (Twilight) June 4 2022 8:25 pm elicits an almost menacing mood with its darkened sky and sombrous, gray and humidity soaked clouds. It is a minimal twilight experience: a day possibly ending with the forewarning of a storm to come. A dark burnt-sienna coloration pervades the entire canvas of Tasogare (Twilight) June 7 2022 8:26 pm, announcing the liminal moment when the sun becomes invisible behind the horizon, and alluding to the end of a very hot day accompanied by a fiery sunset. Moreover, this trio of differing images may also be perceived as synchronistic: they capture practically the same minute in time—if not moment in time—during a series of relatively consecutive days. It is once again a reminder of nature’s ever present and fluctuating powers: ones than enhance our own experiences and responses to life on earth.

Ando’s artistic approach is deliberate and intentional, encouraged not only by the demands of the materials she employs, but also by her ideals. The contrasting qualities—both inherent

and intended—in her work are not contradictory: they should be seen as enrichments. Above all, she holds the view that “Art is thinking and artworks are a residue of thought.” In her work nothing is absent of meaning, yet it elicits an innate spontaneity: it relates the convergence of the human condition and the natural world— and beyond. In its essence Aki wa Yuugure (In Autumn, The Evening) reflects on universalities, for throughout time the clouds and sky belong to us all, despite being beyond our reach, as well as beyond our control—and in light of the dynamics of our current times—Ando hopes this series will foster a recognition of our shared humanity, while inspiring a new path forward founded upon a unison of nature and humankind.

their composition took place in an intimate setting, possibly before the author retired to sleep.

3 Western scholars, in their attempts to define this emotional state, often compare it to lacrimae rerum, or “tears for things,” a phrase employed by Virgil in the Aeneid.

4 During this era, poetry contests known as the “battles of the seasons”—in which both men and women participated— were important events at the imperial court.

1 Ivan Morris (trans. and ed.), The Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon (New York: Columbia University Press, 1967), 16.

2 This unequalled belle lettres opus represents an informal compilation of Sei Shōnagon’s intimate impressions, personal preferences, experiences and keen observations on contemporary court life. Its title originates from the belief that her voluminous writings were placed inside the drawer of her wooden pillow, hinting as well that

Cecelia Levin is an art historian specializing in Asian art. She obtained her doctorate in this area from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. She has taught Asian art history at several colleges and universities and held curatorial and research positions in the Department of Asian Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Asia Society, the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Levin has served internationally as adviser to museums and cultural institutions on collections, exhibitions and educational programming. Throughout her career she has explored a special interest in visual narration and the power of storytelling in art. Her research and writings on art cover a broad expanse representing all eras and regions— including global contemporary art—and the impetus of Asian art and culture on Gilded Age America.

Tasogare (Twilight) June 6 2022 8:26 pm, 2022 ink, mica, pure micronized silver, resin and urethane on aluminum composite, 50 x 50 inches/127 x 127 cm

Tasogare (Twilight) June 3 2022 8:24 pm, 2022 ink, mica, pure micronized silver, resin and urethane on aluminum composite, 50 x 50 inches/127 x 127 cm

Tasogare (Twilight) June 2 2022 8:23 pm, 2022 ink, mica, pure micronized silver, resin and urethane on aluminum composite, 50 x 50 inches/127 x 127 cm

Tasogare (Twilight) June 7 2022 8:26 pm, 2022 ink, mica, pure micronized silver, resin and urethane on aluminum composite, 50 x 50 inches/127 x 127 cm

Tasogare (Twilight) June 4 2022 8:25 pm, 2022 ink, mica, pure micronized silver, resin and urethane on aluminum composite, 50 x 50 inches/127 x 127 cm

Wherever you are, you are one with the clouds and one with the sun and the stars you see. You are one with everything. That is more true than I can say, and more true than you can hear.

Suzuki

t

Zen monk, 1904–1971)

Yuugure (Evening) June 8 2022 8:28 pm, 2022 ink, mica, pure micronized silver, resin and urethane on aluminum composite, 50 x 50 inches/127 x 127 cm

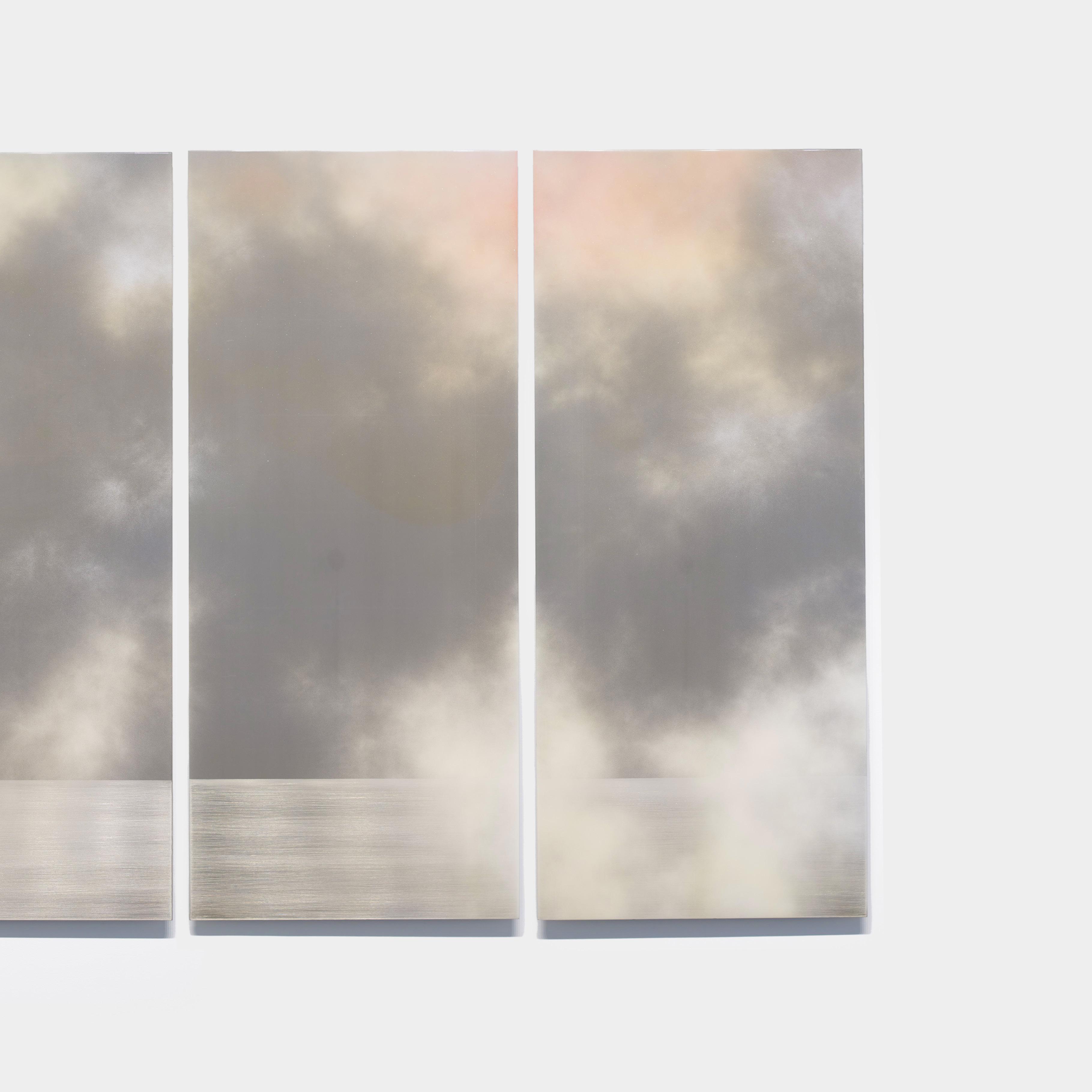

Yuugure (Evening) Triptych June 30 2022 7:46 pm, 2022 micronized pure silver, pigment, resin and urethane on aluminum, 48 x 96 inches/122 x 244 cm

Yuugure (Evening) June 11 2022 8:34 pm, 2022 ink, mica, pure micronized silver, resin and urethane on aluminum composite, 50 x 50 inches/127 x 127 cm

Yuugure (Evening) June 9 2022 8:29 pm, 2022 ink, mica, pure micronized silver, resin and urethane on aluminum composite, 50 x 50 inches/127 x 127 cm

Clearly I know, the mind is mountains, rivers, and the great earth; sun, moon, and stars. —Eihei Dōgen (Founder of the Sōtō Zen school, 1200–1253)

”

Miya Ando’s work has been the subject of recent solo exhibitions at Asia Society Texas Center, Houston; The Noguchi Museum, New York; Savannah College of Art and Design Museum, Georgia; Nassau County Museum of Art, New York; and American University Museum, Washington DC. Her work has also been included in recent group exhibitions at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Haus der Kunst, Munich; The Bronx Museum of the Arts; and Queens Museum, New York.

Ando’s work is in the public collections of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Nassau County Museum of Art, New York; Corning Museum of Glass, New York; Detroit Institute of Arts; Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Arizona; and Santa Barbara Museum of Art among other public institutions as well as in numerous private collections.

Ando has been the recipient of several grants and awards including the Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant and was commissioned to create artwork for Philip Johnson’s Glass House, New Canaan, Connecticut. She has produced numerous public commissions, most notably a thirty-foot-tall sculpture built from World Trade Center steel installed in Olympic Park in London to mark the ten-year anniversary of 9/11, for which she was nominated for a DARC Award in Best Light Art Installation.

The artist holds a bachelor’s degree in East Asian Studies from the University of California, Berkeley. She has also undertaken East Asian studies at Yale and Stanford. A descendant of Bizen swordsmiths, Ando apprenticed with a master metalsmith in Japan.

SUNDARAM TAGORE GALLERIES

NEW YORK

Chelsea: 542 West 26th Street, New York, NY 10001 • tel 212 677 4520 gallery@sundaramtagore.com

SINGAPORE

5 Lock Road 01-05, Gillman Barracks, Singapore 108933 • tel 65 6694 3378 singapore@sundaramtagore.com

LONDON

4 Cromwell Place, London, SW7 2JE

President and curator: Sundaram Tagore

Senior Director, New York: Susan McCaffrey

Director, Singapore: Melanie Taylor Director, New York: Kathryn McSweeney Registrar: Julia Occhiogrosso Designer: Russell Whitehead Editorial support: Kieran Doherty

WWW.SUNDARAMTAGORE.COM

MIYA ANDO | AKI WA YUUGURE (IN AUTUMN, THE EVENING)

OCTOBER 13 – NOVEMBER 12, 2022

Text © 2022 Sundaram Tagore Gallery

Photographs © 2022 Miya Ando

All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this catalogue may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover: Tasogare (Twilight) June 4 2022 8:25 pm, 2022, ink, mica, pure micronized silver, resin and urethane on aluminum composite, 50 x 50 inches/127 x 127 cm

ISBN: 978-0-9967301-8-1