Grieving The Natural World

Hello! My name is Summer. I am a recent Fine Art graduate. I have started Solastalgia zine as a place for artists, activists and writers to express their feelings of grief towards climate breakdown. It is a collection of artists’ works that highlight environmental issues or celebrate the natural world.

The term Solastalgia was first coined by Glenn Albrecht in his book Solastalgia: a new concept in human health and identity in 2003. Solastalgia describes emotional distress caused by climate change, similar to eco-anxiety. Albrecht suggests that feeling solastalgic is comparable to feeling nostalgic, a kind of homesickness, except solastalgia can be felt whilst in your own home. Solastalgia is feeling homesick for our collective home, planet Earth, the way we remember it in our childhoods, a world that no longer exists because of climate change.

Solastalgia is felt by many in our current climate crisis; it is imperative for us not to ignore these feelings or replace them with manic solution finding and over-production. By welcoming the sadness and grief we can, in time, gain clarity and move forward to change and progress our complex human society to live harmoniously with nature’s ecosystems.

There are many great solutions to the climate crisis already out there from Indigenous knowledge to Western academics. However, humanity, so far, seems unreceptive to these ideas. Is it possible this is because we haven’t taken the time to grieve all that has been lost?

You could argue that being still and embracing the sadness is unproductive, but productivity may be an integral cause of the climate crisis. Immersed in capitalist ideologies we’ve learnt to value productivity above all. We saw great things

happen for the planet in the 2020 Covid-19 lockdowns when productivity stopped and the world had a chance to recover. Mother Earth gave us a glimpse of what our future could be like, nature returning, air pollution declining, re-wilding, and cleaner water. Simply being still may be the most radical thing you could do for the planet; joining the natural world in winter and taking a break from productivity to allow ourselves and the Earth time to rest and recover from our busy summers.

So, let’s stop and sit with our sadness and grieve what we have lost during the Anthropocene because it is A LOT. Only in the past half century we’ve lost the ivory billed woodpecker, yangtze river dolphins, the northern white rhino, splendid poison frogs, pinta giant tortoises and many others. Take the time to remember our losses and protect what precious life we have left.

Process image of Hob being returned to the Earth (2022) 55 x 24 cm

Foraged clay

Vessels (2022)

Approx 60 x 90 cm

Foraged clay

Kitty Mills is a ceramics artist, who creates vessels embedded with meaning. She recently took part in a residency at Caro in Bruton, Somerset, where she worked with purely with foraged materials.

She states ‘I remember how I used to see, I carry my childhood around with me. I am blessed to still know the ways of play.

The land, I feel, is an entity. It knows and welcomes me. We observe each other quietly attempting to figure out if we are separate or the same.

It has taken me a while to figure out in words why I do what I do. To me the sculpture is a playful enactment of remembering, a form born of losing myself in my imagination. These characters emerge from the child’s mind,

amongst bracken dens and vast fields. We were equals and I was a part of their world. In listening and noticing I welcome the trace of memory.

The instinctual movement in the hands brings process into focus, I am mindful about how I forage and process the material of the land. The gathering is thoughtful and quiet. On walks I am also collecting sounds, curating them into a soundscape.

Material is gathered from this local land and that of my own, clay that is dug from the sea on opposite shores, married with the earth of Bruton’s woodland. It’s important to me to take only what is needed. And after it will be returned.’

Tilly Lakin is a graphic designer and illustrator based in Bath, Somerset. She is intrigued by the abstract nature of the subtleties and sensitivities of life. She combines her passions for health, nature and poetry within her illustrative design. She is passionate about people’s connection with the planet and how the hidden and intricate intelligence of nature underlies everything in our lives.

Nature’s love is unconditional and all forgiving Nature’s power can bring the whole world into lockdown

Nature is like the furthest part of the subconscious mind that we struggle to comprehend

Nature is within our own bodies: an ecosystem of energy and tiny creatures

Nature is far beneath our feet and high above the stars

Nature is cyclical and never cynical Nature never forgets but always moves on Nature is within cells, atoms, roots and spirits Nature is uncontrollable, majestic and complex Nature is the universe’s precious jewel Nature and us can thrive as one

Soil - The Healing Stomach of The Earth (2022)

59.4 x 84.1 cm

Mixed media

Sophie Mason is a visual artist who makes objects shaped by and from her local landscape. For over a decade her work has explored different approaches to the natural world, working and thinking within the intersections of ecology, climate change, the domestic space, health and gender.

Sophie’s textile works use the fabric of a mordanted canvas both to document the marks made from her experiences within the landscape and from the pigments processed from the mineral and plant based materials she finds around her. Over time the accumulative residue stains the canvas to build a map of care, tracking her relationships with the land around her.

At a certain point the canvas or ‘blankets’ spend more time in the studio than outside.

Sophie draws on them with children’s pencils or ground up pastels, sews pockets into them for medicinal herbs, seeds, feathers or makes shelves for found objects.

Home 4 (2021) 187 x 88 x 15cm

Avocado stones, madder root, hail, snow, sun bleach, oxygen bleach, rust, iron, rain, soda ash, colouring pencils, charred wood, clay, apple blossom, gorse flowers, river water, mould, rescue remedy, vinegar, willow bark, lavender oil, children’s chalk, house brick, canvas, wood, brackets, screws etc.

The Anthropocene is the term that is used to describe the current epoch in which human activity has altered the Earth’s climate and environment, beginning in the mid 20th century to present day. The prefix ‘anthro’, meaning human, states it is humanity who has influenced the climate. However, Jason Moore has proposed a new concept called the Capitalocene, which suggests this age is dictated by capitalism, and that has influenced the climate and environment.

‘Earth systems have been overstretched only under capitalist conditions- in the process transforming humans themselves into a biotechnical Avatar hybrid. Modern capitalism thus is more than a social formation. Capitalism changed human existence; it interpenetrates both earth systems and the mental worlds of each (social) individual.’ (Altvater, Anthropocene or Capitalocene?,2016)

Altvater argues capitalism has evolved from an economic system to a planet altering way of life that has consumed humanity. Capitalism, like a disease, is collectively destroying ecosystems and the human brain. This economic system has changed the way the human brain thinks, to value worth based on labour and productivity. Altvater implies capitalism has turned humans into compliant machines by his use of language. ‘Biotechnical,’ the use of living organisms to make products, has a ‘hybrid’ meaning, the combination of human and the living organisms. The combination suggests a machine whose purpose is to create and consume products.

Humanity has changed from proposing and creating systems and being in control of them, to the system of capitalism running humans, with no one person or group of people powerful enough to oppose the systems and stop the inevitable destruction of the environment caused by the relentless use of Earth’s scarce resources that humanity needs to survive. The system has created a very few people with huge wealth and power who could implement change, but they are unwilling to because they are so enthralled by the system that enabled them to create that wealth and gave them their power. I am linking Altvater’s writing to artist Ai Weiwei’s installation piece Sunflower Seeds (2010) because the piece illustrates modern capitalism.

See fig. 1, Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds (2010) consists of millions of handmade, porcelain sunflower seeds placed on the floor of the

1.

Tate Modern, London. The installation was accompanied by a film of how the seeds were made. In the film Weiwei doesn’t say much about the meaning behind the work but instead focuses on the 1600 people of Jingdezhen who were involved in making the porcelain seeds, highlighting the importance of bringing them work and how he’d like to support them in the future with more work. Weiwei also mentions that many political paintings include sunflower seeds. The example he gives is a painting of Mao Zedong (b.1893), founding father of the People’s Republic of China, where he is surrounded by sunflowers, symbolising him as the sun and the sunflowers as people loyal to the party. (Weiwei, Artist Interview Tate, 2010)

Simone Hancox writes an article about the work and its geopolitical themes. She explains that culture plays an important role in the global distributions of power, especially in wealth and quality of life. (Hancox, Art, Activism and the geopolitical imagination, 2012) The work Sunflower Seeds embodies the cultural power difference because it was only made possible by

the lower minimum wage in China that allowed the artist to pay £0.58 per hour, in comparison the UK’s minimum wage at the time which was £5.93. This difference in value highlights the geopolitical understanding that the East is a producer and the West is a consumer. It would be impossible to reverse the roles because the products made in the West would be unaffordable to the consumers in the East.

I think it’s worth exploring that these sunflower seeds are a duplicate of a real sunflower seed, which typically holds lots of nutritional value. The fact these sunflower seeds are produced by human hands means they no longer hold nutritional value, similarly to the way food is produced. Food production, because of capitalism, now must be done so cheaply to maximise profits that it no longer holds any goodness, so food ends up looking the same but having no benefits at all. There is also sadness in that these sunflower seeds will never blossom into sunflowers because of their artificiality. Their natural purpose stripped away for human consumption.

Hancox states ‘the structures that enable the production of Sunflower Seeds also sustain the hegemony of global capitalism and the transnationalization of production.’ (Hancox, Art, Activism and the geopolitical imagination, 2012) She explains the cheap labour in China is what keeps the capitalist system going across the world. The exploitation of non-Western civilisations allows the system to keep growing and the West to consume more excessively. Weiwei’s piece allows the Western audience to consider their consumption, as by visiting the Tate Modern and being able to hold the seeds they are consuming the work. Weiwei has created a visual representation of global capitalism and the production of goods by having the work made by Chinese hands and consumed by Western hands. Hancox goes on to explore connections between East and West oppression:

‘Ai points to the relative degrees of hypocrisy and contradiction that are also practised in the West: on the one hand, condemning the political oppression of Chinese citizens by the Chinese state, and on the other, permitting the economic oppression of Chinese citizens by Western economies of neo-liberalism.’ (Hancox, Art, Activism and the geopolitical imagination, 2012)

Hancox indicates that Western civilization criticizes how the Chinese government treats their population but has chosen to ignore how Western consumer culture impacts the Chinese workers and how companies exploit their labour. Furthermore the question arises of, are the Chinese government or consumers responsible for the inequality and mistreatment of the Chinese working class? The term Anthropocene suggests all humans are to blame for climate change including the Chinese workers not just the consumers or powers that be.

Unintentionally Altavter proposes an answer to my question of responsibility: ‘Humanity- acting through capitalist imperatives- is organising nearly all its productive and consumptive activities by tapping (and depleting) the planets energetic and mineral reserves. This planetary dominance – like the industrial revolution- is also a revolution.’ (Altvater, Anthropocene or Capitalocene? 2016)

He explores how people have established ‘planetary dominance’ through abusing the planet’s properties, systems and materials. However, to answer my question, he suggests that this is abnormal human behaviour, that humans are acting through capitalist commands. If humanity is being controlled or conditioned to do these things, then they are therefore not responsible for the mistreatment of other beings or to blame for depleting the planets reserves, making the term Capitalocene more appropriate.

However, large corporations consciously choose profitability as their main objective. ‘Ai astutely raises an ethical expectation that the fundamental issue of human rights should be prioritized over trade negotiations.’ (Hancox, Art, Activism and the geopolitical imagination, 2012) Weiwei’s idea of what should be done is a question of ethics for corporations, which do they value more profit or well-being? I think not valuing others well-being can be linked to Agamben’s (b.1942) theory The Anthropological Machine. Large corporate companies may see their suppliers as less than human, allowing them to exploit their labour. This leads me into my next chapter about anthropocentrism.

The full essay is available to read on the Solastalgia website.

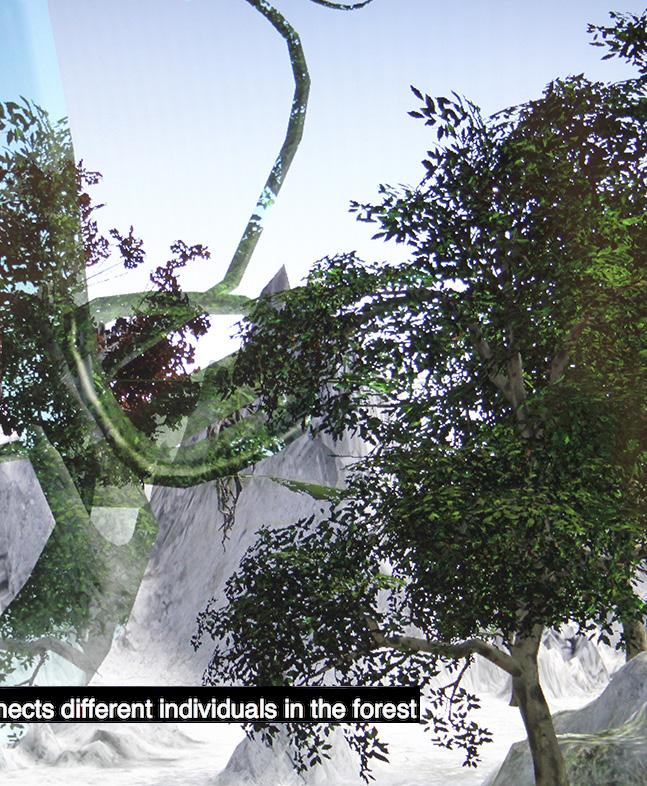

Ella

This image is a still from Ella’s two minute film ‘Forest Virus.’ It features a broken virtual forest originally created for a virtual reality headset, overlaid with scientific and folkloric subtitles. It was inspired by an article which described the forest’s communication network using digital metaphors; calling it an ‘underground fungal internet’ known as the ‘Wood Wide Web’. Forests even have their own version of ‘cybercrime’, attacking intruders with ‘viruses’. The digital forest steadily decays and the subtitles slip between fact and folklore as though delirious with the ‘virus’ they describe.

The collapse of the digital forest creates a commentary not only on our current deforestation crisis, but also our increasing dissonance with nature and reality in today’s digital era.

from ‘Forest Virus’ (2019) Digital Forest

Untitled (2022) Colour medium format film photograph

Untitled (2022)

Colour medium format film photograph

Ellen Carter is a photographic artist, primarily working with medium format film. These images are part of an on going project photographing the landscapes of Chobham Common in Surrey which was started during lockdown, after looking for green spaces near her parents home. The photographs were taken a year after the Chobham Common wild fires.

Sky used to be blue, grey, black. Sometimes lined by clouds, blue, grey, black. When, in those lovely sunny days, golden colour, so hot, almost white, shimmering heat would feel just right.

This was the time for perfect picnic, food and a drink, perhaps to sink.

To sink in a river, lido or a pool, have a swim, don’t be a fool!

These days you have to be cautious as companies pump sewage, how nauseous... Also of lately, the sky is strange, not so lovely, that’s a shame...Peppered with grey lines when sunny, making it all a bit funny.

The summers are now really hot, all those fumes and what not. Pollution in the air, not so pleasant when struggling for air!

Sea levels rising and yet inland water vaporising. Either flood or drought, there is nothing normal, have no doubt.

Governments will allow fracking, who cares about the Earth cracking.

Wake up, wake up, before it’s too late, this really matters, there is action to take!

Over four years ago I decided to go vegan. I wonder now why I didn’t make the change sooner? I’d been a vegetarian off and on since I was a child. I’d grown up in a family where my brothers, father and uncles were all obsessive huntin’, shootin’, fishin’ men and both my brothers went to agricultural college. It was one day in the mid-summer when I went to visit one of my brothers who was on a work placement at a local pig farm, that made me go vegetarian. As it was a hot day sitting in the passenger seat of my mum’s car I had the window down and could hear unholy screaming from miles away. When we arrived in the farmyard the scene was akin to a horror film with a crowd of men including my brother around a metal apparatus that they would haul the pigs’ back legs over and then slice off their balls and slap on some hot tar to cauterize the wound. You’d think I’d never eat bacon again but, to my shame, I did, such was my indoctrination that this was the way things were and the ridicule that came my way from expressing my ‘lefty’ opinions.

But the picture in my head had been changed. I was no longer able to eat meat with impunity. I always felt bad. I even trained as a chef in a French restaurant where I’d gag as I prepped sweetbreads and calves’ liver and run from the smell of the corpulent butcher delivery man who had the hots for this young, trainee chef and would corner me ‘for a cuddle!’ This was the early 90’s, oh for a Me Too movement back then. So why did it take me another 30 years to finally

take the plunge and do what I now consider to be one of the best things I’ve ever done for myself, on a par with stopping smoking and giving birth!

The more I find out about veganism and animal farming the more I understand. There’s a cognitive dissonance that’s deliberately created by the farming industry to protect the status quo that argues that humans are natural meat-eaters and that the land needs livestock on it. If, however, we were born meat eaters we’d not have to hide meat and dairy production behind closed doors and make it illegal for whistle blowers to show the public what really goes on. We’d be fine with it. Baby’s and young children, like wild puppies and kittens would think nothing of ripping the legs and heads off small prey but in reality one of the listed traits of a psychopath is ‘cruelty to animals.’ (Jon Ronson The Psychopath Test, 2011) and such behaviour is considered an aberration.

As a cooking teacher I had to teach the Eat-well Plate which has sections for meat, fish, eggs and ‘alternative protein sources’ and another section for dairy and with every source of nutrient the first on the list would be meat, fish and dairy. All secondary school children have to learn this information as it is part of the National Curriculum. Ask any school child where protein comes from and they’ll confidently shout to you that it’s meat. Then came The Game Changers 2018 documentary film about athletes including Arnold Schwarzenegger who ate a plant-based diet as it enhanced their performance and I had disengaged teenage boys sitting up and taking

notice as they wanted some of that! Mind you I also had furious farming parents (the school I worked in is in the heart of Somerset farming community) saying how dare I teach their kids such rubbish and to keep such ‘way out’ opinions to myself!

Considering the enormous amount of research that has been in the public domain about the dire consequences of the Western diet, I find it shocking that we are still teaching every one of our children that meat and animal products are not only good for them but essential for a healthy diet. The China Study, published in 2005 by T Colin Campbell and his son Thomas M. Campbell, is the most comprehensive study of nutrition ever conducted and extols the benefits of a predominantly whole-food, vegan diet to avoid chronic illnesses such as coronary heart disease, diabetes, breast cancer, prostate cancer and bowel cancer.

In 2015 Michael Greger M.D. published How Not To Die which takes all the nutritional research published and summarizes from it, in lay-man terms, how to avoid the common degenerative diseases in the West. The over-whelming evidence he finds? ...That a wholefood, plant based diet will keep you healthiest for longest.

For me all this has been vindication, I’m not saying for one minute that I’m super-healthy or that my change of diet has solved all by problems, but it has enabled me to live a more authentic life, a life that I’m proud of as I’m doing my small bit in line with my core values.

There are so many anomalies in peoples’ justifications for why they eat meat and I would not judge were it not that their choices to eat meat, fish, eggs and dairy have real-suffering and painful consequences for animals we purport, as a ‘nation of animal lovers’ to value and are, more than anything else, responsible for the destruction of our planet. I miss seeing kingfishers in my local river because the dairy farmer has twice now flushed his slurry into it and killed all the wildlife. My heart bleeds when we go camping in the early summer and you can hear the mother cows calling for their babies and we often walk through fields packed with day old calves looking so forlorn and innocent desperately huddled together for safety. It’s easy to go vegan today. Supermarket shops are brimming with every conceivable plant-based product and You Tube and Tik Tok are full of enthusiastic vegan cooking teachers. You will not miss a thing, on the contrary you’ll feel better as you align your compassionate, loving nature with your food choices. After all we call the way we kill animals ‘humane slaughter.’ I’m not sure the animals would agree as no animal wants to lose its life and the fear is palpable whether they are gassed (pigs and chickens) or stunned and their throats slit (cows). But that speaks of a different human to what we have become. It’s time to take our power back and no longer be intimidated by big brother as I was for so long.

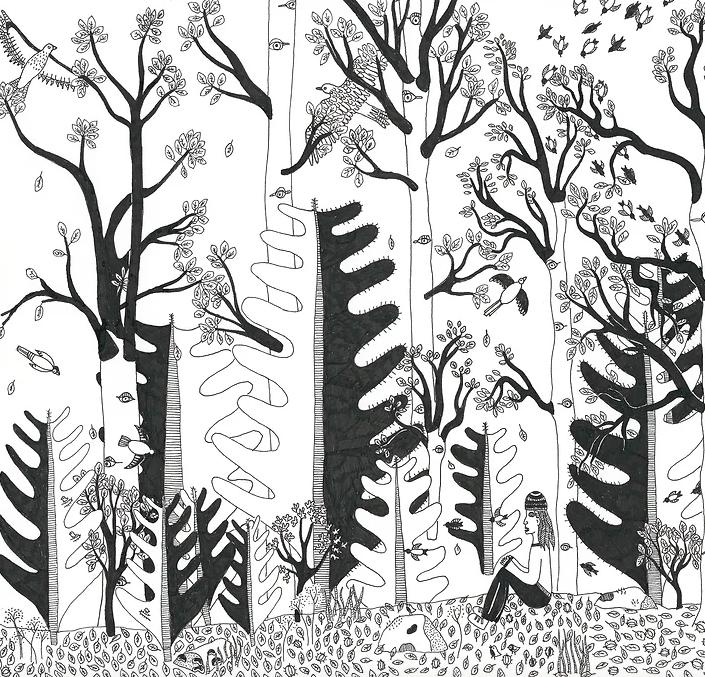

Lauren Goodey is a multi-media illustrator. Raining leaves is a part of her Swedish Story Collection, an illustrative and written journal from her time walking in Sweden.

It’s autumn and golden beech leaves are falling all around me, when the wind blows they fly into the sky, covering the grey clouds with glittering gold. A flock of birds visit me often, thousands of them, landing all around me, in the branches and in the leaves on the floor, feasting on beach nuts which would rain down from the sky. Little wings, brown tufts and pinky orange feathers, black diamonds as they fill the skies. A robin lives in a young beech forest near by, flocks of pigeons joyfully pass, buzzards whistle overhead, merlins weave in and out of the spruce trees in the forest.

I spent 48 hours in this spot. I was so overwhelmed with the beauty, so I drew. After a few hours of drawing, I went to sit in the spot I had drawn my self in. I looked back at where I had been sitting and I could see my life from a different perspective, and I could not work out if I had ever really been there or not.

Jenny Glas is an English Literature graduate from the South West of England who studied at the University of York when the coronavirus first emerged. Creative writing allowed her to respond to a set of circumstances with sensitivity, whilst literature, nature and music have provided her with solace from the situation imposed by the pandemic.

These images are of Jenny’s hand painted Japanese inspired ceramics set. The sunflowers represent positivity, strength, good luck and loyalty. The calligraphy symbols on each mug translate as hope, peace, love and kindness.

She states ‘I’ve been inspired by the literature of Haruki Murakami and have always loved the drinking cultures associated with Japanese and oriental traditions. Peace and hospitality are essential.’

Summer Auty is a recent Fine Art graduate from Central St Martins; her work explores the relationship between people and land through photography and interactive installation.

Over the last year she has looked at feelings of grief towards the quickly vanishing countryside, in England, to new housing developments and the impacts this has on communities and individuals.

Her recent exhibition Homesick focuses on the proposed Selwood Garden Community development in Frome, Somerset.

Photographs of the site are printed onto multiple pages of A4 and tiled together, to divide them into sections with white borders, reflecting the way we build houses in rows and grids like boxes, breaking up the landscape. The work mirrors the complexity of a new housing development through the layers of image. Each page is stapled to the wall so that the pages are easy to remove, revealing the photograph behind. When a page is removed the audience discovers a quote on the back from a local resident, voicing how they felt about the proposed development.

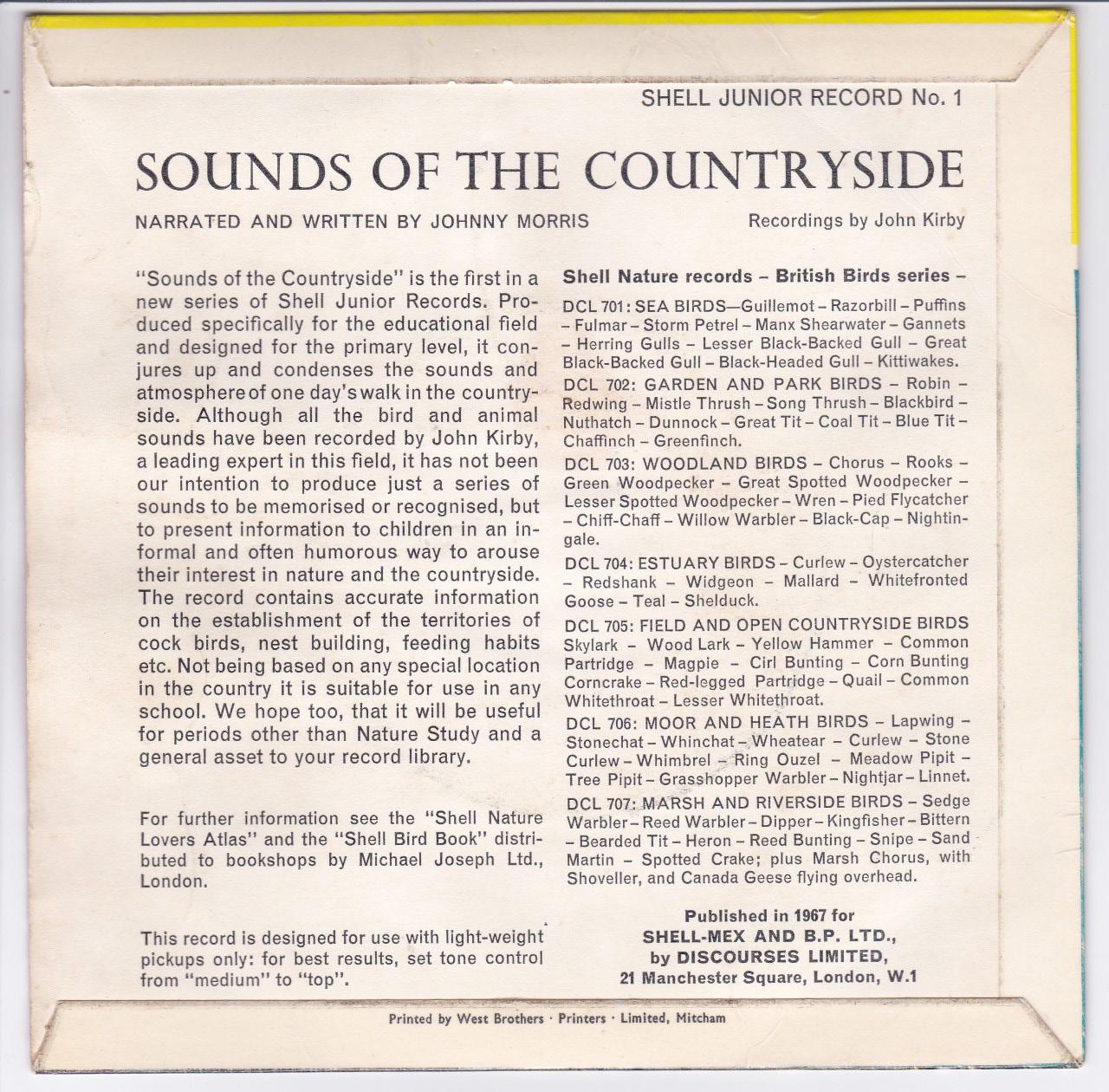

The following text is an extract from Common Salt, a book by artists Sheila Ghelani and Sue Palmer (Live Art Development Agency, 2021). Common Salt originated as a live show and tell about memory, nature and empire that toured museums and libraries, funded by Arts Council England. This extract focuses on how we learn about nature without recognising the contexts of colonialism and the oil industry, and their impact on the environment.

‘People and plants belong to the same colonial story.’ (Corinne Fowler, Green Unpleasant Land, 2020)

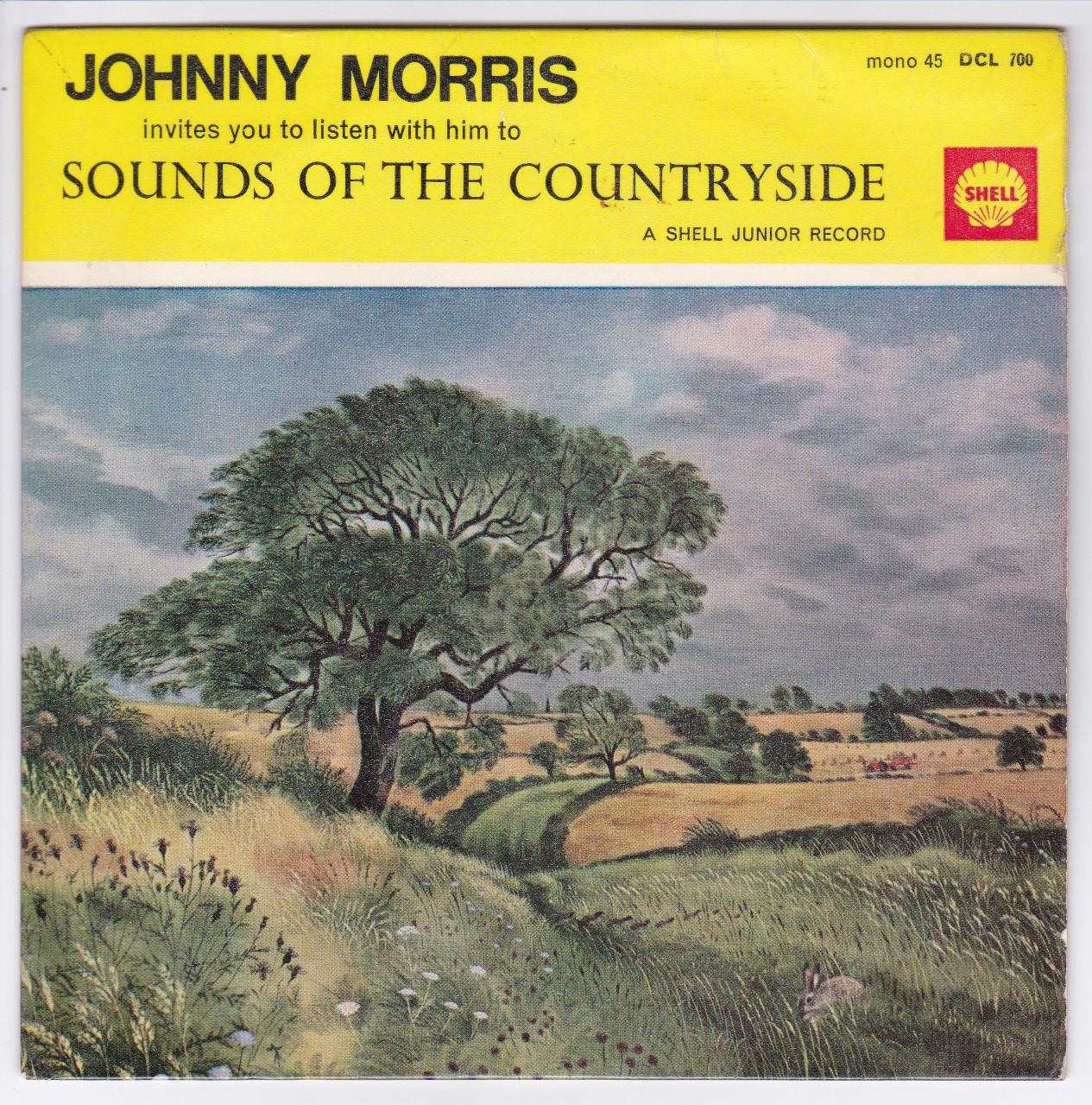

I grew up listening to the 45” single Sounds of the Countryside narrated by Johnny Morris. It was dreamy - pastoral dusky sounds, with a sleeve cover of a winding road with thick hedges, an oak tree and clouds. The record label was Shell. The small logo on the sleeve was that distinctive yellow scallop shell on a red background with red text. The record was part of their Natural History series that included Sea Birds and the Dawn Chorus. The vinyl record was made from polyvinyl chloride, the basic raw materials of which are oil and salt.

I absorbed that visual sign long before I knew anything about Royal Dutch Shell. That transnational corporation had normalised its appearance in my life and sewn itself in through the car, the farm, sounds, nostalgia - it made itself natural. I grew up not knowing. In my mid-30s, I saw Dan Gretton’s durational lecture performance ‘Killing Us Softly,’ with Platform London’s work around oil; it was a life-changing exposure to seeing the extraordinary power and invisibility of these corporations. Shell and the Niger Delta and Somerset - a triangulation linking colonialism with the English pastoral with environmental destruction in Africa.

As a child I was embedded in colonial histories with no knowledge of that, with ancestral connections to empire in both the East and West Indies. My extended family lived in India as part of the British Raj. I remember the awful moment when we found a crate of tiger and wild animal skins in the garage at the house clearance after their son died. That moment influenced a

previous live art work It Is For The Tiger in 2005.

Extraction, exploitation, displacement, hunting, collecting, forced land removals, extortion, market undercutting, enclosure, destruction of the aboriginal and the indigenous, racism, forced labour, cheap labour, market forces, environmental destruction.

We can do no more than bring to the surface just a fraction of the complexity of nature and empire; our gardens, the rural, cities, culture, food, industry - every aspect of our lives are completely entwined - of course they are.

‘Follow the path ... you come to Basildon Park, an estate now held by the National Trust. Its 400 acres of parkland were enclosed by Francis Sykes, the former MP for Wallingford and Governor of Cossimbazar, whose fortune was amassed through his work for the British East India Company. Ten miles south of us run the razorwire fences of Burghfield and Aldermaston’s nuclear weapons facilities. The interests of agriculture, hunting, aristocracy, colonialism and war were laid out before me in the undulating valley, like a series of open books’ (Nick Hayes, The Book of Trespass, 2020)

We took Common Salt to the Museum of English Rural Life in Reading, not far from Basildon Park. Ollie Douglas, the Curator at MERL put together a display in a case beside our show and tell table, of objects that connected the rural to the colonial including: a copy of the East India Company Charter signed by Elizabeth I, a salt jar, cricket balls, a hedge slasher and gloves, a hurdle, a Ladybird book of Ships, a box saying ‘Suttons Seeds’, a silver salver and a large brass Sutton & Son sign in Bengali and English with the Head Office at 130, Russell St, Calcutta-16. Why were we surprised Sheila? After everything we had already learned?

‘Suttons Seeds grew from a local shop into a global firm. In 1912 they established a Calcutta branch, from which they developed and grew seed for the UK and Indian markets. Indian independence came in 1947 but colonial structures persisted. The last British Managing Director of the Calcutta branch was given this sign and silver salver when he retired in 1972.

Suttons and Sons (India) broke away from

the parent company. It still trades out of Kolkata today.’

‘In 1848, botanist Robert Fortune stole tea plants from China for the British East India Company, helping to give rise to the Indian tea industry. That English mainstay - the cup of tea - conceals a complex and conflicted colonial history.’

‘Boundaries and access points play a vital role in the history of rural England. Fencing meant land could be enclosed and the rights of people and animals managed more easily. Across the British Empire land was routinely taken from local populations. These processes were enforced by marking parcels of land on maps and by the introduction of physical barriers and controls.’ (Ollie Douglas, Curator of MERL collections, 2020)

Both of us - you and me Sheila - are into nature; curious about other species and life forms, fascinated by how they live and what they get up to. My garden is full of the foliage and flowers that we lay on the table and string to make garlands. And it’s full with plants, descendants of those brought here by plant hunters.

We were charmed by the anecdote of a tame Robin landing on Eliza’s hand (Eliza Brightwen, Rambles with Nature Students, 1899), with those Lemurs living in her conservatory, but alarmed at the thought of her going to the docks to buy exotic traded animals. We were undone by Octavian Hume with time on his hands while Commissioner of the Great Hedge, able to fund those expeditions to catch, kill and catalogue Indian birds, to fulfil that voracious collecting drive. (Roy Moxham, The Great Hedge of India, Constable, 2002)

Collections, natural history, botanical drawing and colonialism. Now I see it, I cannot imagine how I haven’t always been able to see it - how could it have been so normalised, the connections so invisible; of course Shell would have its own natural history record label for children’s learning.

Sue Palmer is an artist and producer based in Frome.

Future generations may suffer the worst with eco anxiety as their futures are so unsettled. Equally, younger generations seem to be the most passionate and the most brave to stand up for planet, with Greta Thurnburg leading the way and millions of children around the world joining protests demanding action on climate emergency. Solastalgia received work from two secondary school students in Frome which were particularly moving.

Ted Neylor is an art student from Frome Community College. He writes ‘I was inspired to create this drawing because of the increasingly rapid destruction of our planet, which we infinitely rely on and take for granted. It aims to show the catastrophic effects of the climate crisis on us and how we live our lives. I drew inspiration from a quote by Greta Thunberg that simply states, “our house is on fire.” I chose to take this very literally as in order for humans to change, we need to understand the sheer power of what we have done and therefore we need a very hard-hitting message that makes people think, “Why?” The flames represent all of the effects humans have inflicted and are inflicting upon the world and how at the moment we may not see it but they are roaring and are out of control. Is this the end?’

Thomas Yeatman is a Year 9 art student at Frome Community College who looks at the saddening habitat loss in the Artic due to the climate crisis. He states ‘my drawing depicts a minute amount of ice as because of climate change polar bears must swim vast distances just to find sanctuary for another day. It is imperative that the polar bears stay alive as they are of cultural importance to people in the Arctic region as well as being of importance to the wider world and the loss of these magnificent creatures would disrupt the natural food chain.’

Solastalgia originated as a Somerset focused magazine however we reached much further than intended and had beautiful submissions from around the world. We felt it was important that we looked at other artist perspectives of climate breakdown from across the world, not just here in the South West of England.

Irina Tall Novikova is an artist, illustrator and writer. She graduated from the State Academy of Slavic Cultures, Moscow, with a degree in art. Her first solo exhibition “My soul is like a wild hawk” (2002) was held in the museum of Maxim Bagdanovich. In her works, she raises themes of ecology and anti-war, in 2005 she devoted a series of works to the Chernobyl disaster. She also writes fairy tales, poems and illustrates short stories.

This artwork is a small sketch that Irina made in the area that she lives. She depicts autumn trees and the Svisloch River, Belarus.

Adhie Kencana is an artist based in Indonesia. His piece Getting Desperate looks how the balanced ecosystems within a forest are disrupted by human intervention. The clearing of forests for the purpose of making roads will affect the ecosystems and future of the forest, including all the biodiversity within it. Road construction and clearing forests will lead to smaller and isolated habitats for the ecosystems to exist within. These ecosystems are becoming increasingly desperate which leaves the animals that live within them vulnerable to extinction.

The Rebirth of The Earth (2022)

100 x 80 x 55 cm

Chicken wire, puzzle pieces, crochet, crystals

Robelis Rodriguezuez Mijare is a German mixed media artist situated near Düsseldorf. Robelis’s work is made from recycled materials. The Rebirth of the Earth is made using chicken wire from her garage and discarded puzzle pieces that she saved from the rubbish. She crocheted directly on the wire and embroidered it with small crystals.

Solastalgia is a non-profit magazine to raise money to set up a Community Market in Frome, Somerset, as part of the Edventure Frome Start-up course. The market aims to promote community resilience by focusing on coming together to share, mend, swap, donate, and support each other. The course starts in January, and we hope to be testing our idea in March 2023. There are still some places on the course if anyone is interested in getting involved.

Edventure supports community entrepreneurship in Somerset, UK. At Edventure people come together to start things up, tackle community issues and gain skills and confidence to build a positive future, meaning livelihoods, a resilient town, and a fairer, greener world.

Thanks for supporting Solastalgia and Edventure!