Newsletter 73 Summer 2009 SUFFOLK NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY

WHITE ADMIRAL

EDITORIAL

POEM The Lumbering Beast SNIPPETS

THE 2009 PAINTED LADY IMMIGRATION DUNWICH FOREST BUTTERFLY MONITORING

PHOTOS FROM THE BEAUFOY ARCHIVE

THE DEVOURING VERMILLION-SPOTTED

CREATURES AT ORFORD

‘iSpot’ - WILDLIFE WEBSITE LOOKING FOR NATURALISTS NEWS

THE STAG BEETLE - SOME ASPECTS OF LARVAL ECOLOGY

SEAWEED IN AN UNUSUAL HABITAT BOOK REVIEWS

British Moths & Butterflies - A Photographic Guide

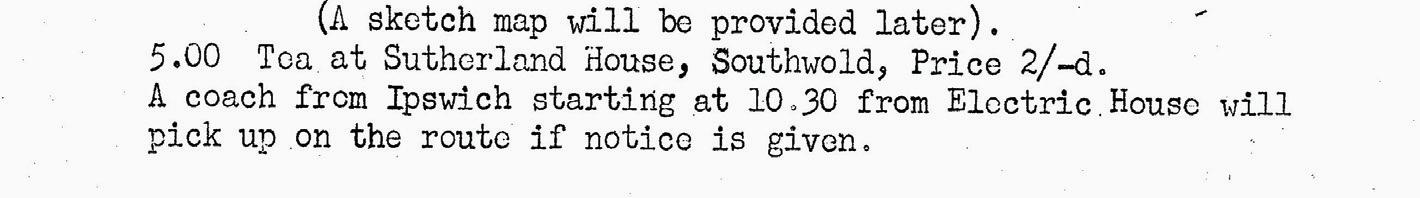

The Mammals of Suffolk POEM Horseman to Lad

ISSN 0959-8537 Published by the Suffolk Naturalists’ Society c/o Ipswich Museum, High Street, Ipswich, Suffolk IP1 3QH Registered Charity No. 206084 © Suffolk Naturalists’ Society

CONTENTS Cover drawing - Bittern by Anne Beaufoy

CRAMP BALLS OR KING ALFRED’S

COFFEE

FROM THE AGM TRENTEPOHLIA ON WESTLETON COMMON

CAKES

WITH A LEAF-CUTTER BEE

JOTTINGS FROM

A HERBALIST’S VIEW OF HYPERICUM HENSLOW’S LEGACY: THE HITCHAM HISTORIC BIODIVERSITY PROJECT ARCHAEOLOGY MONOGRAPH LETTERS, NOTES AND QUERIES Nest boxes for swifts Birdbaths in churchyards Sparrows RECORDS PLEASE

Juliet Hawkins Rob Parker Anne Beaufoy Rasik Bhadresa Rob Coleman Adrian Knowles Michael Kirby Neil Mahler Michael Kirby Colin Hawes Geoff Heathcote Tony Prichard Bob Stebbings Alasdair Aston Juliet Hawkins Caroline Wheeler Edward Martin Judith Wakelam Norma Chapman Joan Hardingham David Nash David Nash 1 2 4 5 6 7 8 10 11 12 13 14 22 24 25 26 29 30 31 32 33 34 34 35 36 36

MILDEN HALL

In praise of scientific names - a postscript Results of appeal for beetles in MV traps Editor

SUFFOLK NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY

SUMMER 2009

David Walker

Ancient House

Lower Street, Stutton

Suffolk IP9 2QE

Quercus121@aol.com

In the current (June 2009) edition of British Wildlife there is an article by Simon Wotton et al (Boom or bust - a sustainable future for reedbeds and Bitterns?) about conservation of bitterns and reedbeds. The authors spell out the state of the bittern in the UK, weigh up the danger of saline invasion of the Minsmere-Walberswick reedbeds and assess the impact of this on the UK bittern population. (In 2008 there were 41 booming bitterns across the UK, the highest number since the 1950s, but only 39 occupied nests, seven of them at Minsmere, making the Suffolk sites the ‘core nesting area’ in the UK - with only seven nests! The chance of a major storm surge, with tides 2.5 m above normal may be as high as 1 in 50 in any given year. Permanent saline incursion of existing sites, rendering them useless for bitterns, is a matter of ‘how soon’ rather than ‘if’). Reedbed creation/restoration is under way at a few sites e.g. Lakenheath, but these must be close to existing sites and a ten-year lead in time is needed to create a functioning bittern habitat. Many more are required.

Wet reedbeds suitable for the bittern provide habitat that supports many other wetland species (water voles, a range of threatened moths, many invertebrate species, UK BAP priority species such as the harvest mouse, the European eel, great crested newts and so on). So creating new sites is a ‘win-win’ investment (it is also a government obligation under Annex 1 of the 1979 EU Birds Directive).

The authors summarise by suggesting a way forward to meet the bittern and reedbed conservation challenge in a four-pronged effort. These are: audit and restore existing reedbeds; create new reedbeds near to the existing ones; protect existing sites in Suffolk as long as possible to provide colonisers for new sites; manage new and existing reedbeds to give the right mix of wet reed and open water.

The above précis does not do justice to the mass of detail and argument of the original paper, which may in time prove to be a seminal study.

Just over a month ago the deadline for copy for White Admiral had passed and I had received only two items. In desperation I e-mailed my naturalist colleagues with a plea for material. Thank you all who came to the rescue – this newsletter is the result. There are some fine articles and it wouldn’t be fair to single out one as the best. As usual there is poetry. Some may think it a bit peripheral. However, we celebrate nature and Suffolk in a variety of ways in these pages: read them and see what you think...

White Admiral No 73 1

***

The lumbering beast

The sun is shining

And grass is grasshopper green

Stridulating song is on the breeze

It’s time to leap and flirt

To impress the girls

And sing our hearts out (may the best man win)

But, Holy Christ, boys

Here comes the lumbering, swishing beast

Loud, ungainly, clumsy in our peaceful meadow, Crashing through this glorious summer day.

Definitely diurnal (preferably when sunny), And armed with numerous appendages.

Two body parts – head and plump, ovoid abdomen, Four clumsy legs but only two aid movement

While the other two are quite adept

At holding objects hard, black and shiny

Or swishing stick with something black and lacy

To chase, pounce, pause, manipulate.

Her two poor attempts at eyes don’t attune to much -

They can’t distinguish real colour, And don’t detect the subtle antennal flicker.

She’s no antennae to smell or feel, Or experience our gentle tibia touch.

Of course, that’s often our escape –We align ourselves with stems

Conceal ourselves in grasses brown and green

Or drop down deep beneath her tread.

The beast moves hither and thither

Thundering around, upsetting webs, Treading grass and moving leaves.

Waving black and lacy, she’ll pounce again, Pause and, unsuccessful, moves on.

This lugubrious beast can’t hear –We sing and really make a racket

But she never turns an ear in our direction.

White Admiral No 73 2

If I were as big as the bumbling beast I’ll tell you what I’d do.

I’d build a big, transparent thing, I’d catch the dismal brute and put her in it

And observe her for a while (see how she likes it),

I’d prod and poke her, check out all her bits

And then I’d kill her (nicely but haven’t thought of how)

And pin her up for all to see

And then …she wouldn’t trouble me.

By Chorthippus brunneus, the field grasshopper

JH August 2008

White Admiral No 73 3

SNIPPETS

• SWT’s water vole and mink control project is paying off - a survey in April this year shows water voles are back in strength along the River Stour between Bures and Daws Hall, and doing well on the Alde and Deben. 300 landowners have trapped 1,750 mink during the five years of the project.

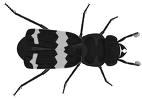

• The Silphidae (burying and carrion beetles) is a small family of large beetles with 21 British species. They are very suitable for beginners to identify. Members of the genus Nicrophorus (sexton beetles) are attracted to lighttraps, so are found by lepidopterists. A pdf document for easy identication can be obtained from richardwright@yahoo.co.uk.

• The cuckoo has been added to the Red List of the UK’s endangered birds. There are now 52 species on the list, which in 2002 totalled 40. Other species newly listed include dunlin, fieldfare, golden oriole, lapwing, redwing, ruff, tree pipit, whimbrel, scaup, wood warbler, yellow wagtail, hawfinch and herring gull. Bullfinch, reed bunting, stone curlew and woodlark are removed from the Red List.

• The Bird Ringing Scheme is 100 years old. Over 36 million birds have been ringed since the first, a lapwing, on 8th May 1909.

• Three new hedgerow advice booklets covering planting, cutting and tree management are available for download from the Natural England website.

• Natural England’s website has a new section dealing with the law and nature conservation: see www.naturalengland.org.uk/ourwork/regulation/default.aspx

• “The Million Ponds Project” is a 50-year initiative to reverse a century of pond loss. Phase 1 starts this year and aims to create 5,000 clean-water ponds by 2012, which will support more than 80 BAP species. See www.pondconservation.org.uk

• ‘Froglife’ and the Herpetological Conservation Trust have merged to form Amphibian and Reptile Conservation. ARC’s first campaign, to encourage interest in reptiles and amphibians in gardens was launched at the Hampton Court Flower Show.

• The Suffolk Tree Sparrow project is under way. Administered by the SWT, this first year’s work is with landowners to identify flocks. Then SWT will work with local people to provide food and nest boxes at suitable sites. Funding for work is from Natural England’s Countdown 2010, and from Suffolk Ornithologists’ Group and SNS for research. Report all tree sparrow sightings to your County Recorder.

• The RSPB is working with a network of swift action groups to compile a national inventory of where the birds are. Help by answering an online questionnaire at www.rspb.org.uk/helpswifts. There is also advice on providing artificial nestboxes. (See Letters, p.34).

• The ‘Hot News’ page of the British Dragonfly Soc has up-to-date news of sightings and is collated by Adrian Parr. See www.dragonflysoc.org.uk.

White Admiral No 73 4

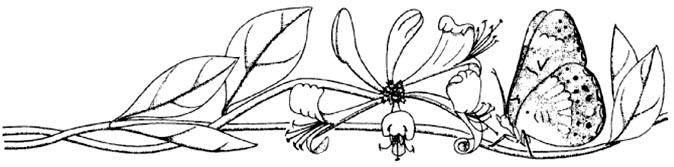

THE 2009 PAINTED LADY IMMIGRATION

Following two years with barely any immigrant butterflies, it was with some excitement that we received one of the largest influxes of Painted Lady for many years. Conditions were favourable in North Africa, and a large build-up of the population occurred early in 2009. By early April they were observed moving north across Spain in large numbers, and some isolated worn specimens turned up in Suffolk from 19th April. The first significant multiple sightings along the Norfolk and Suffolk coasts came on 15th May, and thereafter they dispersed inland, with singles being seen daily in the King’s Forest, Thetford.

Sunday 24th May was something special. All across Suffolk, observers watched a mass migration. Streams of fast-flying butterflies moving in small clusters, passed by for hours on end. Generally they were flying determinedly at about waist height across open country, climbing to pass over trees or houses, and moving on without stopping to take nectar. This is classic behaviour for migratory flight, but is not often seen widely in East Anglia. The individual butterflies were so worn that people had difficulty identifying them at first glance. Here are a few clippings from observations that reached me on that day, under a blue sky, and the warmest day of the year, until then.

Wenhaston: “Just seen PL migration in action in this country for the first time. On Black Heath this morning, in superb weather, I counted 182 flying fast and low up and over the summit ridge across a 40m wide front. All were on a WNW heading and in one hour from 09.30 BST”.

Beccles: “Birders’ web site reports: ‘large influx of PLs along Norfolk and Suffolk coast this morning, including c.100 per hour at Beccles” “A constant westerly passage through Beccles at 12:00, increasing in numbers per hour”.

Mutford: “I managed 67 in 15 minutes watching from my garden, then a move to a more open area south of the village produced 164 in ten minutes. All were heading steadily North-west.”

Saxmundham: “My husband and I have just counted over 200 (yes two hundred) Painted Ladies between 11am and noon flying over our garden from slightly east of south to slightly west of north in a straight line. Mostly in ones, twos and threes. They are still coming though not quite so frequently.”

Rushmere St Andrew: “Has there been another influx of Painted Lady butterflies? I counted a steady stream of 22 in half an hour heading strongly north through our garden this morning.”

Dunwich and Westleton Heaths: “Large numbers crossing the roads back north towards Lowestoft this morning. They were all over the place. Whether the PLs were coming in off the sea here so early in the day or were flying northwards up the coast is not clear at this stage.”

Broom Hill Hadleigh: “Some 500 passing northwards during a period of one and a half hours in threes & fours”.

White Admiral No 73 5

Thetford Forest: “1130 for 4 hours, Over 500 flying high over the pines, all moving in the same direction, not stopping”.

Beyton:“1120 to 1320. Hundreds in all, flying fast at about 4ft & moving from SE to NW, sweeping up over houses & down the other side”.

Bury St Edmunds Continental market morning: “A dozen individuals on the move noticed at roof top height”.

Bury St Edmunds afternoon: “Eight singles passed over during my transect walk, 1530 to 1600, all flying low, heading NW”.

“Steady stream through our field in Little Blakenham today”. “It seems that Large Whites and Red Admirals are flying west too but in less numbers than Painted Lady”.

The migration continued through the following day, as the butterflies moved north-west across Suffolk, and more and more people noticed them. Meanwhile, a similar invasion was arriving along the South Coast of England, and also moving north. Butterfly Conservation organised a UK-wide morning watch for Sat 30th May, but this was an anti-climax in Suffolk, as the majority of the butterflies had moved on by then. Those that remained were exhausted, and glad to pause to take nectar and recuperate.

As for the total numbers, several attempts have been made to offer a reasoned estimate, and figures from 10 million to 50 million have been suggested for the UK as a whole. From local observations, it would seem that the butterflies did not arrive across a broad front, but came in streams, often following routes like the Waveney valley, but with broad areas in between which did not see the same intensity. This makes it difficult to guess at totals. Certainly, after landfall, most paused for an overnight stop, and the next day’s overflights were not always fresh arrivals. The first waves were mostly very battered and short of wing scales, but later arrivals seemed to be in better shape, though not pristine. Ten days after the influx, Painted Ladies were still to be found in most villages, but mostly as singletons lingering. The immigration was over.

With any luck, many eggs will have been laid on Suffolk’s abundant thistles, and we shall have the pleasure of seeing a second generation later this summer.

Rob Parker

Dunwich Forest Butterfly Monitoring

The “greening” of Dunwich Forest requires close monitoring of the flora and fauna of the forest, and the habitat alterations should benefit the four BAP butterfly species found there (White Admiral, White-letter Hairstreak, Silver-studded Blue and Grayling). Two butterfly transect walks will be set up in time to go live for the 2010 season (starting 1st April, and monitoring once a week until the end of September). The Suffolk Wildlife Trust is looking for volunteers prepared to learn the ground rules and walk a set route through a part of the forest. The walk will be conducted with participation shared by members of a team. A training day has been arranged for Saturday 19th September 2009:

White Admiral No 73 6

10:00 Assemble at the Dunwich Reading Rooms for an indoor presentation by Rob Parker, the Transect Co-ordinator for Suffolk:

• What is a transect?

• Time and weather limits, Counting & Recording rules.

• Butterfly recognition.

11:00 Transfer to Dunwich Forest

11:15 Briefing on the Dunwich Forest Project by Dayne West (Reserve Warden).

11:30 Outdoor session along one of the intended routes; practical butterfly counting & recording.

Familiarity with butterfly identification is a useful starting point, but volunteers should not be discouraged by a lack of knowledge at this juncture. Transects are a very enjoyable pursuit, and one learns a lot “on the job”. If you live within striking distance of Dunwich Forest and would like to participate, please make contact with the SWT warden on 07902 315378.

PHOTOS FROM THE BEAUFOY ARCHIVE (1)

By kind permission of Anne Beaufoy

By kind permission of Anne Beaufoy

White Admiral No 73 7

Minsmere sea wall

1954

THE DEVOURING VERMILLION-SPOTTED CREATURES AT ORFORD

It was on my birthday that we decided to take the National Trust ferry across to the bleak and desolate terrain of Orford Ness. Straightaway, it had the feel of ex-military about it, lots of concrete and bizarrely-shaped abandoned installations. However, not far along the red route, we spied tough silken nests of caterpillars on a small, no more than a metre tall, solitary hawthorn shrub. One of these disc-shaped constructions with tenacious silken threads running in all directions was nearly 12cm across and 4cm deep and heaving with dark larval forms, most around 20-25mm long, (photographs on p 16). The morning sun of early May was no doubt activating the denizens of this fine silken creation.

These occupants were simply lovely to watch; they were not in a hurry and were not going to be travelling very far anyway. They were already where they wanted to be – on their food plant! As far as they were concerned, life couldn’t get much better. Being active and growing at the same time as the new ‘soft and nutritious leafy shoots’ of your ‘parent’ plant can only be a lovely coincidence of nature’s wondrous design. What identified them as Brown-tail caterpillars were a couple of small but very striking vermillion protrusions near the back end of the darkish but very hairy body in the style of a true tussock moth. A couple of parallel broken crimson lines on the top and rows of white tufts on either side of the slender body with a dark shiny head, made these larvae very distinctive. The large primary nest firmly and securely fixed with strong silk fibres, which incidentally would have had to withstand the blustery wintry hostile weather of Orford Ness while its baby occupiers lay dormant, was itself a thing of amazing beauty. But as was to be expected, there were small bead-like dark scatological remains scattered throughout the nest.

We spent a most engaging 15 minutes observing before deciding to look in again on the way home. Hoards of St Mark’s flies and, beyond the Bailey bridge over Stony Ditch, carpets of sea campion were to delight us but those are other stories! On our return three hours later (the warm sun had been out all morning) the nests were almost empty of caterpillars. Instead they were everywhere on this coastal bush, it was as if an inner voice had told each one of them: ‘go forth, fatten-up and flourish’. We saw several zealously chomping away at the young leaves. They had dispersed via the branches in all directions and to derive most benefit, it appeared as if they had managed to avoid each other. Further up the bush, we had also noticed a couple of smaller constructions, which we thought could only be satellite nests. This meant the caterpillars did not have to return after the day’s feeding to the ancestral nest further down which was probably getting overcrowded anyway. It was important that they had a refuge to retreat to for the night for protection, group adhesion and warmth. But don’t be fooled by the beauty of these beings. A gentle word of warning: do not handle or get too close because the poisonous hairs can cause rashes, headaches and even breathing difficulties!

While the caterpillars munched their way along the stems and twigs, in the process

White Admiral No 73 8

stripping the poor hawthorn, we had our own lunch to think about and so we hurried back. We didn’t want to miss the last orders at The Crown and Castle.

Rasik Bhadresa

Biological footnote: The Brown-tail, Euproctis chrysorrhoea (L.), belongs to the family of tussock moths Lymantriidae. A resident moth, it is found mainly on or near the coast, primarily from Hampshire to Suffolk. The adults are almost pure white with the tail end of the abdomen chocolate brown, hence the name Brown-tail. The eggs laid on the lower branches of the host plant in the summer, hatch out in late August and while still quite small the caterpillars go into hibernation in a robust silken web. In spring when active again, brown-tail larvae construct new nests until they are fully grown around June when they pupate singly or communally predominantly on the food-plant. Apart from hawthorn, the other most common plants are sloe, bramble and sea buckthorn.

PHOTOS FROM THE BEAUFOY ARCHIVE (2)

Blythburgh old railway track, September 1954

White Admiral No 73 9

‘ iSpot’ - A WILDLIFE WEBSITE LOOKING FOR NATURALISTS

iSpot is a new website designed to bring people with an interest in nature together. Billed as ‘your place to share nature’, iSpot draws inspiration from the success of ‘social networking’ websites such as Facebook to provide a forum for people of all ages to share observations and experiences.

Created by the Open University (OU) and funded by Open Air Laboratories (OPAL) iSpot was originally conceived as an educational resource to assist with biological identification. Users can post observations, pictures or descriptions of things they’ve seen and others can respond suggesting identifications or providing information. Albums of observations can be created, tagged and searched and sightings are linked with locations provided by Google Maps. The website is designed to be simple to use but with some powerful underpinning features that can be expanded as the project develops.

Whilst many groups cannot be readily identified to species level without a specimen, it is hoped that iSpot will become a useful biological recording tool in the future. Links with the National Biodiversity Network species dictionaries and distribution maps will help to identify unusual records worthy of further investigation and information from iSpot can be exported to other organisations for recording or survey purposes. This will also be linked with the OU’s ‘Bayesian Keys’ project – aimed at applying computing power to traditional identification keys so they can be accessed rapidly in the field via handheld devices.

The success or otherwise or iSpot will ultimately be decided by whether or not it is able to deliver useful information to its users, be it assistance with an observation by a novice or an interesting new record for a biological recorder. To this end iSpot is appealing for new users, whatever their background or experience, to become involved with the new community. So log on to www.ispot.org.uk and have a go!

Rob Coleman Biodiversity Mentor, East of England

Suffolk Naturalists’ Society Members’ Autumn Evening Meeting

Thursday November 19th at 7.30 pm

Wolsey Room, Holiday Inn, Ipswich

An invitation is being extended to members of the Colchester Natural History Society for some cross-boundary chat.

White Admiral No 73 10

The 80th Annual General Meeting of the Society was held at 7.30 p.m. on Wednesday 22nd April 2009, at the Holiday Inn, Ipswich. The most significant parts of the formal business were a series of Resolutions to modernise and improve the Constitution of the Society. These Resolutions were all passed unanimously. As a result, the post of internet “web-site manager” now becomes an Officer of the Society; Ordinary Members of the Council may now serve two 4-year terms before having to stand down, should they so desire; the relationship of the Society with like-minded natural history special interest groups and Society sub-committees has been clarified; and finally, the meeting gave approval in principle for the sale of land at Rose Hill.

Adrian Chalkley and Tony Prichard ended their four-year terms as Ordinary members of Council. However, Adrian immediately returns as our web-site manager and Tony returned under the newly sanctioned rule regarding two terms on Council. Other vacant positions were filled as follows: Colin Hawes has long sat on Council as an observer in his role as one of the Rivis Vice-presidents but is now a full ordinary member with voting rights. Ann Ainsworth is the natural history curator at Ipswich museum, with a particular interest in geology. Gen Broad heads up the Biodiversity Action Plan team in the museum and has an interest in marine life as well.

Howard Mendel has been acting Chairman for the last year but was voted in as Chairman at the meeting. There is now the need to find a replacement Treasurer since Howard, quite understandably, does not wish to maintain both posts!

The formal business of the society was then followed by an informative talk given by Simone Bullion of the Suffolk Wildlife Trust on her new book on Suffolk mammals, copies of which were for sale on the night. Our thanks go to Simone for providing such a good talk for our members.

Adrian Knowles Honorary Secretary

OTHER CHANGES AMONG SNS OFFICERS AND RECORDERS

• Dr Robert Stebbings has been reappointed as SNS President until 2013.

• Scott Mayson has been appointed by SORC as Bird Recorder for south-east Suffolk.

• Gen Broad has been appointed as Marine Recorder.

• Neil Mahler has been appointed by Council as Fungus Recorder

• Adrian Parr is the new Recorder for the Dragonfly group.

Email addresses of all officers and recorders can be found on the website, sns.org.uk

White Admiral No 73 11

NEWS FROM THE AGM

TRENTEPOHLIA ON WESTLETON COMMON

The bark of some trees on the Common has an incrustation of the green alga Trentepohlia. It occurs on the trunk of a sallow tree growing in a thickly populated group of Salix caprea, S. cinerea and hybrids, and on a wild plum, again in a thicket of an abandoned hedge (Fig. a, p.18). The patches of the alga may be up to 25 x 100 cm, usually on one side of the trunk only; the colour varies from yellowish orange to brick red. Even though the trees are probably quite old, the bark is relatively smooth and the sallow has not developed the deep fissuring sometimes seen in mature S. caprea.

This year the alga was also seen growing in the open on an area of depauperate heather and stony, sandy bare ground. Early in March S.F., looking for fungi, noticed a widespread, brick red layer, usually spreading from a stunted heather plant over the bare sand. By the time it had been identified and photographed early in April, (Fig. b p. 18) it had largely dried up and was confined to the heather clumps. It has now (late May) disappeared altogether.

Although a green filamentous alga it appears reddish in colour, due to the orange pigment, haematochrome (β-carotene), which hides the green of the chlorophyll. Trentepohlia is also a widespread photosynthetic photobiont in lichens. (A good web site for more information is: www.biol.paisley.ac.uk/bioref/Chlorophyta/ Trentepohlia.html)

The species was identified as Trentepohlia umbrina by Dr Hilda Belcher who described its distribution mainly in the West and North West of the country. More recently she has found it on a Tulip tree in a Cambridge College garden (to be written up in ‘Nature in Cambridgeshire’) and has learnt that Professor Bate and a research student are researching its apparent spread in the south of England, possibly in response to the decrease in SO2.

Dr Belcher has suggested that this note may produce new records, so keep your eyes open for more!

Michael Kirby and Sheila Francis

White Admiral No 73 12

CRAMP BALLS OR KING ALFRED’S CAKES

Practically everybody must have come across these weird blackish blobs sitting on dead logs or standing trunks at some time; some people may even be surprised at their charcoal-like consistency, and thanks to Ray Mears, we can all have lots of fun with them.

In Britain, these are usually found on Fraxinus and the scientific name is Daldinia concentrica, but occasionally these are also found on other trees and especially burnt gorse. In fact the species on gorse is so different in having a barely visible stalk that it has long been called D. vernicosa, although this name has recently been changed to D. fissa.

Over the years this genus, like so many others, has come under close scrutiny, and in Britain it is now recognised we have 7 different species. To try to keep things simple, those found on Fraxinus, Fagus and Sorbus will usually be D. concentrica, on Betula, D. loculata, and Ulmus, D. grandis. Daldinia decipiens can also occur on Betula, but this is very rare in Britain; and also Daldinia caldariorum can be found on burnt gorse, this too appears to be rare.

Superficially, they all look very similar, the main difference being in the spore measurements, which are not readily available to the amateur mycologist such as me. To confuse things even more, recently I was contacted by an SNS member in Stonham Aspal who told me he had a Cramp Ball growing on a dead Betula in his garden.

Knowing we have no records of D. loculata from Suffolk, I immediately went out to obtain a sample to send off to Kew hoping for confirmation.

I sent this off together with another Cramp Ball I found growing on Aesculus at Thornham Walks, but I was to be disappointed and even more confused for Kew told me the one on Aesculus was D. concentrica and the section I sent of the one on Betula was almost certainly the same, but he needed the entire specimen to be certain. So back I go to Stonham to pass on the disappointing news, but was able to come back with the whole specimen, with some bark still attached, to be passed on to Kew. Before doing so I was able to measure some spores myself and they were well within the range of ordinary D. concentrica, but at least this is the first known record of D. concentrica on Betula from Suffolk.

It would appear that D. loculata only occurs on burnt or scorched Betula, so if you come across such a specimen or indeed any Cramp ball growing on any species other than Fraxinus or burnt gorse, then please do contact me at fungi@sns.org.uk.

Neil Mahler

White Admiral No 73 13

COFFEE WITH A LEAF-CUTTER BEE

This year, as with the last seven, our coffee breaks in the garden have been enlivened by watching the life and times of leaf-cutter bees (Megachile species).

It all started when a small bonsai dish was filled with a mixture of sandy soil and coarse grit, planted with Sempervivum offsets and set on a table in the garden. Within a year or so the plants were well established and started to ‘heap up’ as the offsets grew through the established plants eventually overtopping them and shading them out. At this stage, in about 2003, it attracted the attention of leaf-cutter bees which exploited small gaps at the edge to burrow under the plants and make their nests. As they dug, the excavated material was tipped over the edge of the dish, in time reducing the level of the soil by about 3 cm. They also tried to throw out particles of grit, but unable to get a foothold on the glazed edge of the dish, gave up after a brief struggle, leaving an accumulation of small stones. Some time during this period a moss established itself where the bees were digging and now it occupies about one fifth of the area, gradually infiltrating the Sempervivum and submerging it (Fig. a, p.16).

At the end of May, the first of the latest generation of bees appeared excavating its burrow under the moss. It entered the hole head first and after about two or three minutes backed out dragging the spoil between its front legs and down-bent head. It retreated three or four centimetres before releasing its load and flying off, making a small circuit before re-entering the burrow and repeating the operation. (The excavated material appeared to be largely organic with a few small stones, indicating that it was digging in the decomposed plant material rather than any remaining soil.) This was followed by a period when it left to collect large, rectangular sections of leaf which it held beneath its body, supporting each one with its legs by hooking its claws over the edge of the leaf. As it entered the hole it used only its mandibles to pull the leaf section, some times with a struggle, into the hole (Fig. b, p.16). After repeating this operation two or three times the bee next visited the nest with a load of pollen, which it gathers on the hairs on the underside of its body rather than pollen baskets and thus is visible as a rim of yellow around the rear of the abdomen (Fig. c). The final act before it started again on another cell was to fetch a smaller more circular section of leaf to close the cell.

As the leaf-cutter was working, the site was visited by other bees and wasps which lurked around the nest. The most colourful was the ruby tailed wasp, Chrysis sp. which was seen on two occasions to nip into the burrow to lay an egg or inspect progress. This is a parasite which lays its egg in the bee’s cell, from which the wasp larva on hatching eats the leaf-cutter bee larva.

Another more sinister looking visitor with its pointed abdomen and dark head and thorax was the bee, Coelioxys sp. (Fig. d, p.16). (I am grateful to Adrian Knowles for his identification.) This, like the ruby tail, kept the nest under close observation and once was seen to enter the burrow, only to make a hurried exit as the owner was working within. Unlike the ruby tail wasp this bee does not parasitize the larva of the leaf-cutter bee, but is a kleptoparasite which lays its egg in the cell. This

White Admiral No 73 14

hatches before that of the leaf-cutter bee and then destroys its egg before eating its food store (O’Toole & Raw 1991).

The dish was watched closely for about an hour around 11 am on most days. Casual observation throughout the rest of the day suggested that the main period of activity was from about 10 am when the dish was in full sun until mid afternoon. After about six days the bee was not seen again although the hole was left open. Reflecting on the bee’s behaviour, I was amazed at the way in which it performed a complicated series of tasks and the effort involved. Flying with a relatively large piece of leaf acting like a sail clearly took a lot of effort: the bee sometimes landed near to the dish and took a minute or so to summon up energy to finish the task.

The source of the pollen and nectar with which the bee provisioned each cell was not identified. To gather pollen on the underside of its abdomen presumably requires a flower with exposed upstanding stamens like a daisy or other Asteraceae, but there were few flowers of this type in the near vicinity.

The regular nest building by leaf-cutter bees over a period of years suggests that each generation returned to the place where it was hatched to make its own nest. The same may be true for the two parasitic species, i.e. the bonsai dish is a small self contained ecosystem ideal for nature study in comfort.

Reference

O’Toole, C & Raw, A (1991). Bees of the World. Blandford Press.

Michael Kirby

White Admiral No 73 15

PHOTOS FROM THE BEAUFOY ARCHIVE (3)

Blythburgh, September 1954

Leaf-cutter bees

(a) The bonsai dish in 2006. The activity of the bees has removed a quantity of soil and moss is encroaching. A leaf -cutter bee is approaching its nest hole at the junction of the moss and the Sempervivum

(b)

A leaf-cutter bee dragging a large section of leaf into its hole. At this stage it is holding the leaf with its mandibles.

(c)

A leaf-cutter bee entering its hole with a load of pollen collected on the hairs under its abdomen and visible around its rear end.

(d)

A kleptoparasitic bee (Coelioxys sp.) lurking near the leaf –cutter-bee nest. The red dot is a passing mite.

White Admiral No 73 16

The

(a) Close-up of main nest

(b) Satellite nest

(c) Main nest, side away from the sun

White Admiral No 73 17

the Brown-tail moth, Euproctis chrysorrhoea.

Rasik Bhadresa

Trentepohlia

(a) Trentepohlia on wild plum (Prunus domestica) in an overgrown hedge. There is moss growing at the base of the trunk and the small grey patches are lichen.

(b) Trentepolia in April. At this time it had dried up and was present as small red nodules amongst stones and dead heather. The grey threads at the top of the picture are a lichen (Cladonia portentosa).

White Admiral No 73 18

Michael Kirby

White Admiral No 73 19

Cramp balls

(b) Daldinia concentrica on dead Betula Neil Mahler

(a) Daldinia fissa on burnt gorse

Stag beetle larva and food

White Admiral No 73 20

Fig. 1. Final instar larva of Lucanus cervus, almost ready to pupate

Fig. 2. Piece of dead sycamore trunk showing excavations made by stag beetle larvae

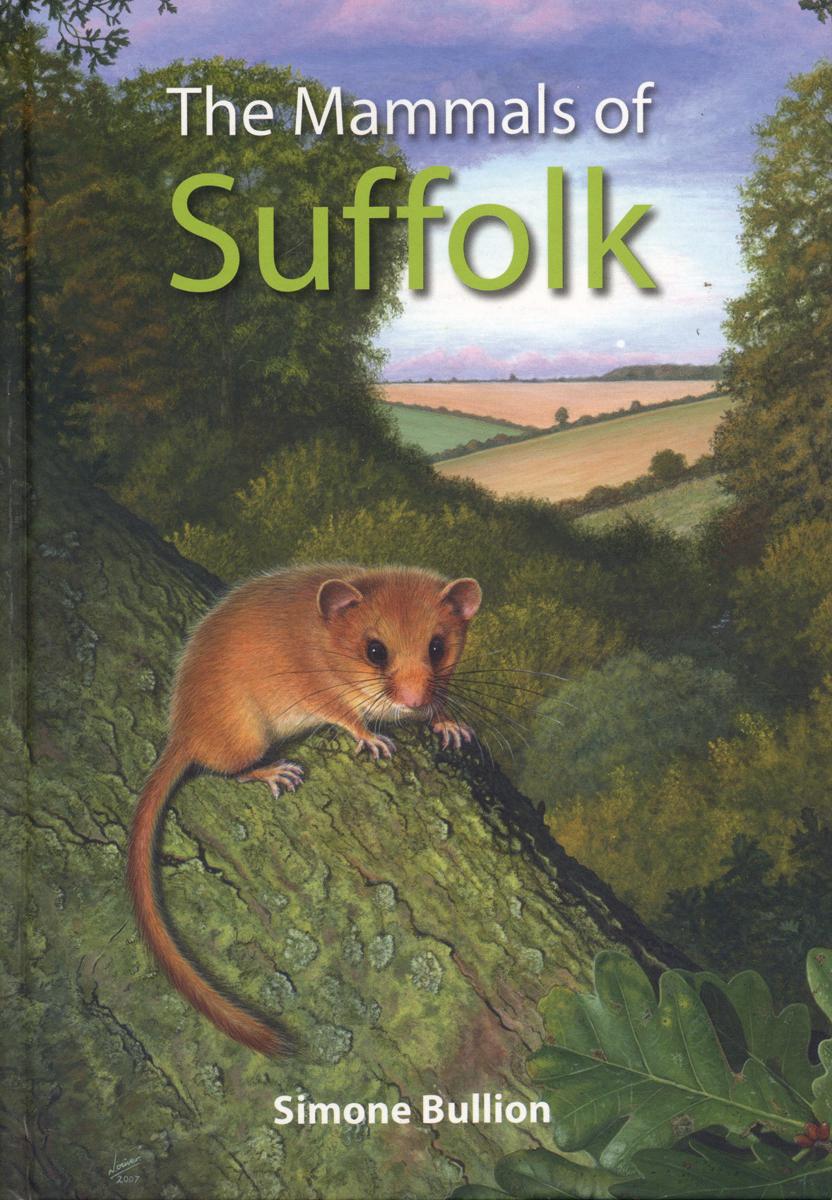

The county’s first comprehensive account of Suffolk’s mammals is jointly published by Suffolk Naturalists’ Society and Suffolk Wildlife Trust. TheMammals ofSuffolk by Dr Simone Bullion, is an accessible and attractive book with stunning colour photographs throughout and distribution maps of more than 60 species, from bottle-nosed dolphin and Minke whale to soprano pipistrelle bats and red deer. It is a superb addition to Suffolk’s natural history and is as likely to appeal to the lay naturalist as to those with a more specialist interest.

TheMammals ofSuffolk is now available from Suffolk Naturalists’ Society, c/o Ipswich Museum, High Street, Ipswich (01473 433547) or SWT centres or SWT office at Brooke House, Ashbocking (01473 890089). You can order a copy by phone, cost £20 (+ £3.50 p&p).

White Admiral No 73 21

THE STAG BEETLE - SOME ASPECTS OF LARVAL ECOLOGY

The stag beetle Lucanus cervus has eclectic tastes, forming associations with a wide range of broad-leaved trees and shrubs as well as other woody material. A list of tree and shrub species in Suffolk with confirmed records of stag beetle larvae (Fig. 1) in the decaying wood (Fig. 2) was published in the Suffolk Naturalists’ Society’s Transactions Vol. 34, p. 43 (Hawes, 1998). Since then, a further 21 tree and shrub species have been added to this county list (Table 1).

Larval habitat is in the rhizosphere, the plant root region below the soil surface. Here, decaying wood retains the moisture that the larvae require. Wood above ground often becomes too dry for stag beetle larvae to survive, though they sometimes feed on the underside of logs when these are in contact with the soil. Larval pabulum varies from the wood of dead tree stumps and roots to logs, the sunken part of wooden fence posts, woodchip, compost, and most strange of all, cat litter. Oak Quercus robur and elm Ulmus procera seem to be the most favoured food species, closely followed by apple Malus sp., sycamore Acer pseudoplatanus and birch Betula sp. Coniferous wood seems rarely to be used as larval pabulum., probably due to its sticky, resinous content. Both native and non-native tree and shrub species can provide food for the larvae (Table 1).

Larval life, which can last up to six years, is spent partly in the soil and partly in the wood that provides their food. There are five instars. Stag beetle eggs are laid in the soil, sometimes up to 40cm deep, close to suitable dead wood (a female can lay up to 30 eggs). The first instar larvae hatch some three weeks after eggs are laid. The larvae then move towards the wood and tunnel into it using their chisel-tipped mandibles. Excavations are distinctive, so much so that tunnels made by the 4th and 5th instar larvae can be used to identify past occurrence of the species even when larvae are no longer present.

When the 5th instar larvae have completed their growth they pupate. Pupation takes place underground, up to 40cm deep, inside a pupal cocoon. Each pre-pupal larva builds its own cocoon from the material available around it, such as soil particles and woody debris. Cocoons are often the size of a goose egg, oval in shape, with walls about 1cm thick, and are quite fragile.

Larvae are sometimes unearthed when gardening in composted soil, or when removing old shrubs or tree stumps. If they are accidentally exposed, they should be reburied as soon as possible with some of the decaying woody material on which they were feeding. However, if for some reason they cannot be reburied either where they were found or at another location in the garden, please place them in a sealed container with some moist (not wet) compost or decaying woody material and contact me, Colin Hawes: telephone 01473 310678 or Email c.hawes@homecall.co.uk.

Colin Hawes

White Admiral No 73 22

White Admiral No 73 23

% Tree and shrub species Common name 1.0 Acer campestre* Field maple 7.2 Acer pseudoplatanus Sycamore 1.0 Aesculus hippocastanum Horsechestnut 1.0 Berberis sp Barberry 6.2 Betula sp* Birch♦ 2.1 Buddleia davidii Butterfly bush 1.0 Castanea sativa Sweet chestnut 1.0 Cotoneaster sp Cotoneaster 2.1 Crataegus monogyna* Hawthorn♦ 1.0 Escallonia sp Escallonia 1.0 Eucalyptus sp Gum 3.1 Fagus sylvatica* Beech♦ 1.0 Fatsia japonica Fatsia 1.0 Fraxinus excelsior* Ash♦ 1.0 Ilex aquifolium* Holly 1.0 Juglans regia Walnut♦ 1.0 Laburnum sp Golden rain 1.0 Mahonia japonica Mahonia 7.2 Malus sp Apple♦ 1.0 Pinus sp Pine 1.0 Pinus sylvestris* Scots pine 3.1 Populus sp Poplar♦ 3.1 Prunus sp Cherry♦ 1.0 Prunus spinosa* Blackthorn♦ 1.0 Pyrus sp Pear 1.0 Quercus ilex Holm oak 9.3 Quercus robur* English oak♦ 1.0 Quercus petraea* Sessile oak 2.1 Salix sp Willow♦ 1.0 Symphoricarpos rivularis Snowberry 2.1 Syringa vulgaris Lilac♦ 1.0 Taxus baccata* Yew 9.3 Ulmus procera English elm♦ 1.0 Viburnum sp Viburnum Other 1.0 Cat litter (wood shavings) heap 9.3 Compost heap 4.1 Composted vegetable plot 2.1 Horse manure 2.1 Sawdust heap 2.1 Woodchip heap

Table 1. Trees, shrubs and other woody material with confirmed stag beetle Lucanus cervus larval presence in Suffolk. (% to one decimal place. *native species. ♦species listed in Transactions of the Suffolk Naturalists’ Society 34, 1998)

SEAWEED IN AN UNUSUAL HABITAT

Seaweeds can be found in some fairly strange places: on one’s plate in Japan for example, or growing on a wrecked boat or plane if diving in shallow water in Malaya, but I never expected to come across a seaweed illustrated in a journal devoted to heraldry.

In an amusing note in Vol. 110 of The Heraldry Gazette Dr Gavin Hardy describes his coat of arms, granted by the College of Arms in 2006. He is a marine phycologist and has spent his life studying seaweeds. His attractive shield is gold (Or in heraldry) and green (Vert in heraldry) and the wavy diagonal bands (bends) across the shield represent the sea. Over these is a chevron representing the dichotomously branched thallus of Fucus vesiculosus L. bladder wrack, a brown seaweed, with its paired air bladders.

The crest on top of the helm also shows bladder wrack, in the mouth of his Labrador dog who used to help him collect seaweeds. She did not eat the plants, preferring sea urchins, and the dog is shown on a rock studded with them. My sketch of Dr Hardy’s arms is based on a design by Dr Clive Cheesman, Rouge Dragon Pursuivant, but I do not want to discuss red dragons here. I must stress that the arms are legally those of Dr Hardy and no one else can use them. However, the use of seaweed is not unique. The cormorant in the arms of the City of Liverpool has a piece of seaweed in its beak.

Geoff Heathcote

Contributions

Deadlines for copy are 1st February (spring edition), 1st June (summer edition) and 1st October (autumn edition).

The opinions expressed in White Admiral are not necessarily those of the Editor or of the Suffolk Naturalists’ Society.

White Admiral No 73 24

BOOK REVIEWS

British Moths and Butterflies - A Photographic Guide by Chris Manley. Published by A & C Black Publishers Ltd., 2008. £25. 352 pp, colour photos, softback ISBN 978-0-7136-8636-4 (available online at www.acblack.com)

As interest in moth recording has increased in recent times so has the available literature, and currently there are two popular books for the identification of the larger moths: The Colour Identification Guide to Moths of the British Isles by Bernard Skinner and the Field Guide to the Moths of Great Britain and Ireland by Paul Waring and Martin Townsend. Chris Manley’s book is a recent candidate for joining this group with its comprehensive species coverage of the butterflies, larger moths and a sizeable number of the micro-moths. The book’s introduction gives its objectives as providing enough information to identify almost any of the larger moths or butterflies and secondly to be visually stimulating, to celebrate and raise awareness of the beauty and diversity of butterflies and moths.

There are several short sections at the beginning and the end of the book giving information on how best to see and photograph lepidoptera, their lifecycles, how they are classified and a table of larval foodplants. Although the coverage of these subjects is rather brief it is what I would expect from an identification guide, a more expansive approach to these subjects would detract from the primary focus of species identification and is already covered in more detail in other moth books.

Most of the book is taken up with colour photographs and species accounts of the moths and butterflies. Coverage of the larger moths and butterflies is quite comprehensive with images of over 850 species of larger moth and 74 species of butterfly included. In addition nearly 500 of the 1500+ species of micro-lepidoptera in the country are also illustrated. A smaller section has 314 photographs of the nonadult stages. I would estimate that three-quarters of the page space is taken up with colour photographs, something of an achievement given the price of the book. The remaining page space contains short textual accounts for each species with information on its size, flight period, rarity, habitats, food-plants and brief help on identification where appropriate. For some species there are several photographs showing variations, aberrations and identification features. It would be better if more photographs showing identification features were included and illustrations of features on the underside or hindwing are largely lacking in those cases where they would be useful.

As a guide for use in the field the book has a couple of negative points: it lacks a hardback cover and the relatively flimsy paper used may not last as long as in the field as other moth guides. As a guide for identifying micro-lepidoptera I would hesitate to recommend it due to its patchy species coverage and lack of detailed information on differentiation of confusion species. However, it is refreshing to see so many photographs of micro-lepidoptera illustrated in a book aimed at the more general moth recorder; it may entice a few more recorders to begin studying these families in greater depth.

White Admiral No 73 25

Does the book meet its objectives? As an identification guide it would probably not be my first choice, I think the Skinner and Waring books provide more help to the recorder in this area. The textual accounts in these two books give more information on identification features and the more uniform layouts of moth images makes comparison between species easier. This new book would certainly make a good additional identification resource, providing further images for comparison during the identification process. As a book that aims to celebrate the beauty and variety of moths I think it would be very difficult to find a better example with the number and variety of high quality colour photographs within its covers.

Tony Prichard

The Mammals of Suffolk by Simone Bullion. Suffolk Wildlife Trust and Suffolk Naturalists Society, 2009: 207pp. Hardback: £20.00

Mammals tend to have been a neglected group of wildlife except by land managers, farmers and game keepers all of whom have sought to control perceived ‘pest’ species. Hence, there has been recording of the ‘bags’ made on estates and even in church records where pests such as bats sometimes had a price on their heads. The demise of species such as the pine marten was not formally recorded but estate records show how the number killed each year diminished but the date of extinction, probably sometime in the mid nineteenth century, remains unknown. (By definition, a rare species is difficult to find!)

Amongst the naturalists, mammals received scant attention because many are nocturnal and hide away by day and often, it only has been possible to discover much about species’ life histories with the use of modern technology. Generally, most mammalogists get to know about the presence of animals by what they leave behind them - droppings, scats or in modern parlance - poo!

Gathering together the scattered notes and records was first attempted by the Victorians such as Thomas Bell, 1874, in his account of The History of British Quadrupeds and J G Millais epic tomes on The Mammals of Great Britain and Ireland. These volumes provide largely anecdotes of discoveries and observations made by all kinds of people who often did not understand what they observed but, with present knowledge, we can interpret those carefully recorded notes.

Further assemblages of the then current knowledge were made by BarrettHamilton with Hinton in their multi-part ‘A history of British Mammals’ published from 1910 - 1921. Also, The Victoria History of the Counties of England (1911) for the first time includes sections specifically on the mammals of individual counties, including Suffolk. However, although interesting snippets of information was given on most of the Suffolk mammals, usually relating to named sites with dates, there was little knowledge of the distribution, population sizes or habits of each species of a kind we now enjoy.

White Admiral No 73 26

The next milestone in the Suffolk mammalian story was Claud Ticehurst’s paper on Suffolk Mammals published in the Transactions of the Suffolk Naturalists’ Society in 1932. However, this was really an annotated list with the particular interest being a description of the extinct species especially from the fossil record such as from the red crag strata. To me, one of the interesting comments concerned the otter which he described as ‘I think there is hardly a suitable stream ... in the County which lacks otters’. We now know that species became extinct around 45 years later but with the immensely successful river clean up and re-introductions, now has become a common Suffolk species again. No attempt had been made to produce distribution maps for species as there were no data bases. The next progression in assembling knowledge about our mammals came from our former SNS member, Dr Harrison Matthews with his British Mammals (Collins: New Naturalist 1952). This detailed the biology and natural history of each species as well as descriptions of distributions and comments on abundance. Later the Mammal Society of the British Isles produced the Handbook of British Mammals with first edition in 1964 with 465 pages to 4th edition in 2008 with 799 pages. That last volume was a full compendium of present knowledge about all species and is a standard work where mammal enthusiasts would find both a digest of the latest information as well as a comprehensive source work bibliography.

So it is with that background that the new book by Dr Bullion was eagerly awaited. The amount of effort required to produce such a work cannot be overstated. When taking on such a project it soon becomes a daunting prospect of how to find and collate all the sources of information and to write a reference and readable book while fulfilling a busy job helping to protect habitats and species in Suffolk. However, the task has been achieved with an attractive and concise volume which will form a standard work and stimulus for more work in our County.

The volume starts with an incredible list of all the sources of records, about 560 individuals submitting information, most in the last 15 years or so. The book then has sections on the history of mammals and a systematic treatment of all the known extant species and concludes with an interesting chapter on surveying for mammals and what can be done to encourage various species and what we can do to help reverse declines. Of course, this latter depends on detailed research to establish exactly what individual species require and recipes on what we can do in talking with landowners to help them manage habitats in an effective way.

A nice touch is a brief introduction to each mammal group with the history of introductions for such species as rabbits and un-natural introductions such as bats arriving as stowaways on ships or military aircraft.

Each species account gives information on the history, distribution and aspects of their behaviour and natural history. Distribution maps are augmented with a box giving vital information on the species and drawings showing food or other signs which can identify who produce the signs and all accounts are lavishly illustrated with colour photographs of the animals and habitats.

So, with Simone Bullion’s book we have an most attractive work to grace every bookshelf of all those interested in wildlife in Suffolk (and adjacent counties) but the

White Admiral No 73 27

real value is not for it to stay on the shelf but to be a stimulus for everyone to become enthused in observing this diverse group of fascinating animals. Most of us will have some of these species living in or visiting our gardens and there is always the opportunity to make new observations on aspects of their lifestyles.

As a teenager born in Bury St Edmunds and educated in Suffolk I was introduced in 1952 to a research project begun by SNS members in 1947 and on joining the Mammal Society in 1957 the fourth Earl of Cranbrook (the President of that Society, as well as SNS at the time) wrote to me saying he was ‘ploughing a lonely mammalian furrow in Suffolk’ and thereby persuaded me to join our Society. I greatly valued the support he gave me in my career in mammal research and in conserving mammals through the Wild Creatures and Wild Plants Act 1975 and the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. He was a principal mover of these vital pieces of legislation protecting Britain’s wildlife including some mammals.

Robert Stebbings President, Suffolk Naturalists’ Society

PHOTOS FROM THE BEAUFOY ARCHIVE (4)

White Admiral No 73 28

Horseman to Lad

You just standin there boy?

Ent you goin home?

Might as well get along

Back to the little woman

See what she's doin

Gettin her tongue ready

Sharpin it up for you

Just soo you unnerstan

How hard she work

For you and your kids

Cruel hard she do

And jist soo you know

She'll put a word in your ear

Suffin clear

Soo dont you just stand there

Gapin

Do you get along now

Get on home

No use thinkin of the pub

They ent oopen yet

Not for another five minutes

Or so

Alasdair Aston

White Admiral No 73 29

JOTTINGS FROM MILDEN HALL

Ups and downs – survey bias or annual fluctuations?

♣ Adders tongue (Ophioglossum vulgatum) thrived in 2007 on our lovely meadow at Milden but there wasn’t a single spike this year. Ladies smock (Cardamine pratensis) puts up a few flowers in a damp depression in the same meadow most years but this year has surprised us, flowering all over the place including our very dry lawn. Bee orchids were abundant on clay spoil around our pond in 2008 but barely a flower head in 2009.

♣ White tailed bumble bees ( Bombus terrestris) seemed very frequent this spring but the mason bees (Anthophora plumipes and Melecta albifrons) were very thin on the carpet (literally, for this is where they emerge from our wall and crawl around until rescued). This 2009 spring pied shieldbugs (Sehirus bicolour) appear more frequent on the farm whilst I barely saw one in 2008; and I haven’t seen a woundwort shieldbug (Eyacoris fabricii) for two years on the farm, whilst previously I saw them frequently, mating on woundwort leaves. This year’s big up so far has been the cardinal beetle (Pyrochroa serraticornis) which I have found on nettles and hawthorn leaves in far higher numbers than previously on the farm.

♣ I’ve seen more frog and toad tadpoles during my Suffolk pond surveys than I’ve seen in years – and fewer great crested newt. It does make one realise just how sensitive these species must be to factors way beyond our knowledge.

♣ We have four pairs of swallow this year (up from last year’s two pairs) and no house martin at all – down from 17 pairs last year. I’ve heard the cuckoo once; I’ve seen a pair of spotted flycatcher and thought they’d return to last year’s nest – both cuckoo and flycatcher moved on.

So are these very localised, commonly occurring, real, annual fluctuations (as I suspect) or simply the survey bias of an unscientific naturalist who takes opportunistic walks, at random times in varying weather and keeps unempirical notes on scribbled paper rather than a methodical, systematic diary which tells one very little?

The (swimming) slender groundhopper

Whilst loitering around ponds, as I do, this spring I have seen numerous slender groundhopper Tetrix subulata along the pond margins. I can’t help noticing that on my approach they purposefully leap into the water to avoid me. At first I thought they were accidentally doing this and tried to fish one or two out but then noticed that they swim very confidently underwater. Since then I have noticed them frequently leap towards the water and swim very happily downwards ‘to safety’ away from my tread. A strange defence adaptation for such a land-loving family of insects whose name suggests they are closely related to the ground as opposed to water!

Juliet Hawkins

White Admiral No 73 30

A HERBALIST’S VIEW OF ST JOHN’S WORT

As I write this in mid July, Hypericum perforatum has been in flower for several weeks, in gardens and on roadside verges. It gets its specific name from the appearance of its leaves. A leaf held up to the sun appears to be dotted with tiny perforations. They are in fact pockets of transparent oil. And why St John’s Wort? Richard Mabey tells us that it was one of the sun herbs, burned on Midsummer’s Day as part of the pagan purification ceremonies to enhance the power of the sun in purifying communities and crops. With the advent of Christianity, the plant was adopted for St John, since the feast of St John the Baptist is on June 24, conveniently close to Midsummer’s day.

Over the last ten years Hypericum perforatum has become a popular remedy for mild to moderate depression. Herbalists have always used it for this purpose and for many other conditions. Its efficacy in depression is supported by the results of many clinical trials. A recently published meta-analysis of 13 such trials found extracts of the herb to be as effective as selective serotonin uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in the treatment of mild to moderate depression. It also found a similar incidence of side effects associated with the two treatments. However, patients taking St John’s Wort were less likely to withdraw from a clinical trial as a result of side-effects than patients taking SSRIs, suggesting that the side-effects from the herbal remedy were less troubling.

One of the most useful items in the herbal dispensary is infused oil made from this plant. It is made by steeping the yellow flowers in a jar of oil (olive, almond or sunflower oils are all suitable) placed in direct sunlight for several weeks. The oil will turn a deep red as the constituents of the flowers are extracted. The oil is then strained off the flowers and used in a variety of external applications. It has an antiinflammatory action and is also effective against enveloped viruses, including those of the Herpes group. Thus it can be usefully applied to burns, insect bites, cold sores and the lesions caused by Herpes zoster (Shingles). It is often included in creams to treat eczema.

Caroline Wheeler

References

Mabey R (1996). Flora Britannica. London: Sinclair Stevenson. Rahimi R, Nifker S, Abdollah M et al (2009). Efficacy and tolerability of Hypericum perforatum in major depressive disorder in comparison with selective serotonin uptake inhibitors: a meta-analysis. Progr Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 33 (1): 118-127.

White Admiral No 73 31

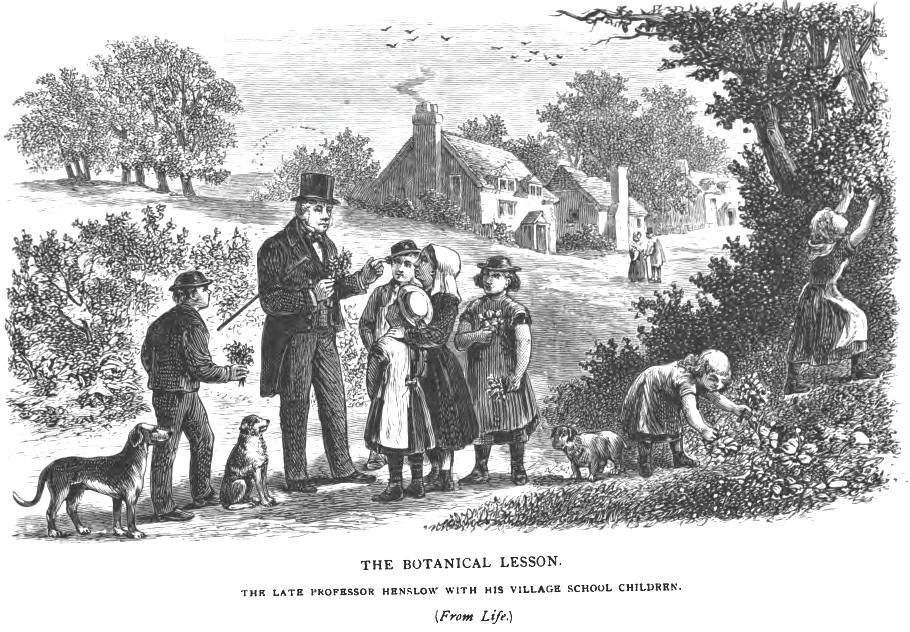

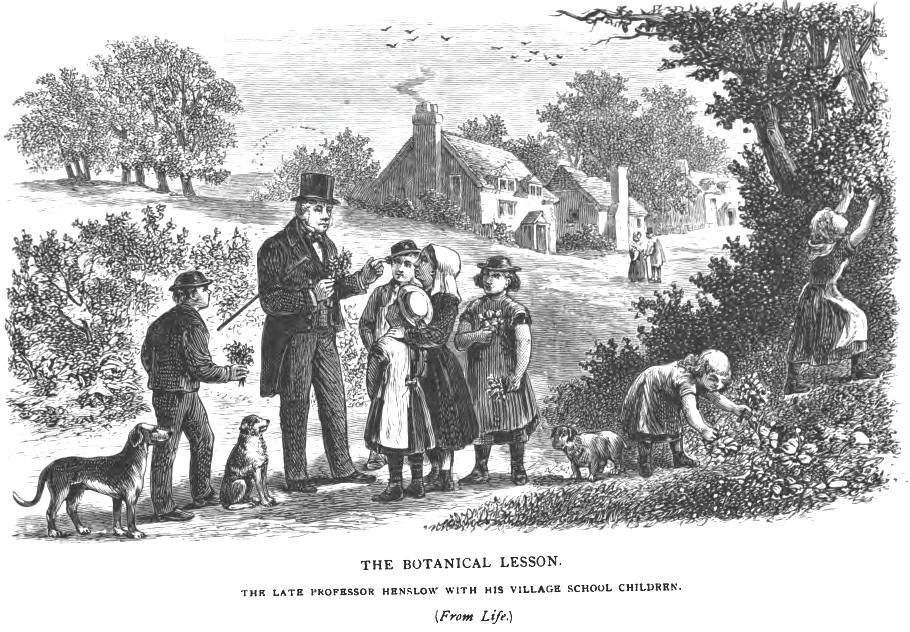

HENSLOW’S LEGACY: THE HITCHAM HISTORIC BIODIVERSITY PROJECT

The Rev. Professor J.S. Henslow (1796-1861) is best remembered as Charles Darwin’s tutor at Cambridge, where his inspired teaching fired Darwin’s great interest in the natural sciences. He secured for Darwin that all-important place on the voyage of the Beagle and acted as his friend and advisor throughout his life. But Henslow was also the Rector of Hitcham in Suffolk for 24 years, where he has left a unique legacy. He started botany classes for the children and adults of his parish and in the 1850s, partly to help and inspire the schoolchildren, he compiled a list of the flora of Hitcham. Copies of his lists survive in Cambridge, as do hundreds of his herbarium specimens in Ipswich Museum (which he helped to found in 1847). This is an extraordinarily early and full botanic record for a Suffolk parish.

Henslow’s legacy was reviewed a hundred years later by Alec Bull, the son of a Hitcham farmer and now a noted naturalist in Norfolk (a co-author of the 1999 Flora of Norfolk), who published an article in the Transactions of the Suffolk Naturalists Society in 1977 comparing the 1850s data with his own researches in the 1944-60 period. His data covered the crucial post-war years when there were great changes to the landscape and he was able to show changes in the flora.

Interest in Henslow has been renewed in this, the 150th anniversary of the publication of Darwin’s great work, On the Origin of Species, in 1859. A project is now being formulated by the Hitcham community and the Suffolk Biodiversity Partnership to undertake a new botanical survey of Hitcham and to consolidate the data from the two earlier surveys. The survey should be running in 2010, the 150th anniversary of the publication of the first Flora of Suffolk, which was co-authored by Henslow and mentions his Hitcham lists. Hopefully the new survey will be

White Admiral No 73 32

completed in 2011, the 150th anniversary of Henslow’s death.

The project will bring together an unrivalled 160 years of botanic information for a Suffolk parish. This will be a great resource for investigating changes over that period, some caused by the great changes to our farming landscape between the 1850s and now, and others perhaps indicative of climate change. It will also be a great asset in demonstrating the wide range of biodiversity contained within an ordinary Suffolk clayland parish. Suffolk’s claylands make up a large part of the county and are of great importance for their historic landscapes. However, they are largely devoid of designations for biological rarities and are thus perhaps underrepresented in considerations of Suffolk’s biodiversity. The project therefore has great potential, not least for inspiring a community’s interest in their biodiversity, something that would have pleased Henslow immensely.

The project is at an early stage of its planning and further details will be made available as it progresses.

Edward Martin (edward.martin@suffolk.gov.uk)

ARCHAEOLOGY MONOGRAPH

‘Wheare most Inclosures be’. East Anglian Fields: History, Morphology and Management East Anglian Archaeology monograph series no. 124, 2008, by Edward Martin and Max Satchell (ISBN 978 0 86055 160 7; 270pp; 116 illustrations; £30 (or £35 by post); obtainable from the Archaeological Service of Suffolk County Council: see www.suffolk.gov.uk/Environment/Archaeology/ Publications/EastAnglianFields.htm)

This report contains the findings of an English Heritage-sponsored investigation into the nature, date and working of the historic field systems of ‘greater East Anglia’ (Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, Cambridgeshire and Hertfordshire) with an emphasis on the region’s ‘ancient countryside’. Twelve detailed case studies are presented, together with commentaries on the evidence for prehistoric and Roman field systems, including the claims for the existence of large Iron Age co-axial systems; on the terminology of medieval farming; on why there is so little evidence for ridge-and-furrow in the region; on different types of common fields and their varying distributions and contrasts with lands held in severalty; and on the management of field boundaries. An unexpected discovery of the project was the identification of a significant cultural boundary running through Suffolk that has been termed ‘the Gipping Divide’. The possible reasons for this division of the region into southern and northern components are discussed and a case is made for a connection with the upheavals caused by the Viking interventions of the 9th/10th centuries.

White Admiral No 73 33

LETTERS, NOTES AND QUERIES

Nest boxes for swifts

I read with interest the Snippets section in the spring edition of White Admiral referring to the steep decline in swift numbers over the past few years. I too had noticed the decline and became concerned for the swifts that return each year to my village of Worlington in West Suffolk. Their main destination over many years has been a flint cottage with a pantiled roof, now under threat of demolition.

I have had a great deal of support from the village in my quest to have swift boxes installed behind the louvers in the tower of All Saints Church. Not only has it created a lot of interest, it has I hope, ensured that our Worlington swifts will continue to return to the village in future years once they lose their present nest site. I can only hope that whatever replaces the cottage in the future is developed by a sympathetic builder, who will incorporate swift bricks into the build. There are several ways of doing this with little effort and are aesthetically pleasing. As your Snippets stated, a great many nest sites have been lost due to the renovation and demolition of so many old buildings. Maybe churches could play a part in the solution to the problem!

Dick Newell and Bill Murrells from Swift Conservation installed our boxes in February; they have already had success with boxes installed in Ely and Haddenham churches in Cambridgeshire. I can only hope that our Worlington swifts will take advantage of the new safe nest site the boxes offer although it may take time. I am watching the Church tower with great interest. We’ve done our bit now it’s up to the swifts.

For more information and advice go to www.swift-conservation.org.

Judith Wakelam

Bird baths in churchyards

Many Suffolk churchyards are havens for wildlife: anyone who has seen a presentation on this subject by Yvonne and David Leonard will be well aware of this. Why do so few churchyards have a bird bath? What better tangible way to commemorate a loved one, either on a grave or in a suitable spot for anyone whose ashes were interred elsewhere.

Permission is required and someone needs to clean it regularly (e.g. weekly in winter, at least twice as often in summer) and fill the bath. A hand brush, hung in a nearby bush, is ideal for routine cleaning and an occasional thorough scrub is needed. Remember that a concave dish is much easier to clean than one with a vertical edge, and the greater the capacity of the bath the better.

Norma Chapman

White Admiral No 73 34

Sparrows

Has anyone else lost their house sparrows? I never thought I would be missing them. There used to be dozens cheerfully twittering along the gutter edges and chasing the tits off the bird table and then a few years ago I realised they had gone. Nothing else I can see has changed. They used to nest under the tiles of the old farm buildings and pick up grit and dust bath on the concrete path then suddenly I realised I hadn’t seen them for a while. The annoying thing is I can’t pin-point when that was but it must be 5 years now. I kept thinking they would come back; we are only a few hundred yards from the village which seems to have plenty. I have begun to feel guilty and even rather indignant that we have been rejected in this way and jealous when I sit in other people’s gardens who can still enjoy the idle twittering. Is there any way of encouraging them back? All the projects seem to be about encouraging tree sparrows.

Something I have noticed recently is that the dunnocks which lurk under the hedge near the bird table and sally forth to grab fallen crumbs have started to behave more like sparrows. They are much bolder and have started to feed off the bird table: I half expect them to start tackling the peanut feeder like the house sparrows did. You don’t know what you've got till it’s gone...

Joan Hardingham

WEATHER DATA

The weather data for Boxford have been left out of this edition owing to shortage of space.

Members who are interested to see rainfall and temperature data for the first six months of 2009 can find them on the website, www.sns.org.uk. If anyone needs to study the data and does not have access to the internet, please contact me at the address given on page one. I will be pleased to supply the graphs in a suitable format. Editor

White Admiral No 73 35

RECORDS PLEASE

In praise of scientific names - a postscript

David Walker recently drew attention to the rediscovery of the rare, so-called crucifix ground beetle at Wicken Fen, which he had seen reported on the BBC News website (White Admiral, autumn 2008, 71: 32). His article included a plea for the use of scientific names for living organisms as we have two Panagaeus species which have cruciform markings and superficially look alike but only one of which, Panagaeus crux-major L., is rare.

It has just been reported (Warrington, S. (2009). The Coleopterist 18: 33-34) that the record was an error - I assume for the locally distributed P. bipustulatus (F.). This highlights the way in which misinformation can be instantly disseminated on the web creating fiction from fact, something the original recorder can do little to control or emend once the process has begun.

David Nash

Results of the appeal for beetles from MV moth traps and other beetle records received

In response to my appeal for MV material in last summer’s White Admiral 70 I was pleased to receive from Neil Sherman at Ipswich Golf Club, beetles from his trap as well as a list of his other beetle records for 2008 and I am grateful to him for finding the time once again.

I must especially thank Nigel Cuming who has, as always, kept me up-to-date with his Suffolk captures and I am also grateful to Nigel Odin and Adrian Parr for their usual annual list of beetles from their respective recording areas. Thanks also to Jeff Higgott for sending a specimen found at light at Landguard for naming.

David Nash Coleoptera Recorder

White Admiral No 73 36

Advertisement Caroline Wheeler Herbal and Nutritional Medicine www.herbsnutrition.co.uk

SUFFOLK NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY BURSARIES

The Suffolk Naturalists’ Society offers five bursaries, of up to £100 each, annually.

Morley Bursary - usually awarded for studies involving insects (or other invertebrates) other than butterflies and moths.

Chipperfield Bursary - usually awarded for studies involving butterflies or moths.

Cranbrook Bursary - usually awarded for studies involving mammals or birds.

Rivis Bursary - usually awarded for studies into the County’s flora.

Simpson Bursary - in memory of Francis Simpson; this will be for a botanical study where possible.

Any member wishing to apply for a bursary should write, with details of their proposed project, to the Honorary Secretary. As applications are normally considered at the Council meeting in May of each year, proposals should be with the Hon. Sec. by 30th April.

Applications made at other times will be considered but, even if considered worthy of an award, may not be successful if all the bursaries for the current year have already been taken.

The following two conditions apply to the awards:

1. Projects should include a large element of original work and applications must include a breakdown of how the bursary will be spent.

2. A written account of the project is required within 12 months of receipt of a bursary. This should be in a form suitable for publication in one of the Society’s journals: Suffolk Natural History, Suffolk Birds or White Admiral.

THE SUFFOLK NATURALISTS’ SOCIETY

FOUNDED IN 1929 by Claude Morley (1874 -1951), The Suffolk Naturalists’ Society pioneered the study and recording of the County’s flora, fauna and geology, to promote a wider interest in natural history.

Recording the natural history of Suffolk is still one of the Society’s primary objects, and members’ observations are fed to a network of specialist recorders for possible publication before being deposited in the Suffolk Biological Records Centre, which is based in Ipswich Museum.

Suffolk Natural History, a review of the County’s wildlife, and Suffolk Birds, the County bird report, are two high quality annual publications issued free to members. The Society also publishes a newsletter, White Admiral, and organises two members’ evenings a year plus a conference every two years .

Subscriptions: Individual members £15.00; Family membership £17.00; Corporate membership £17.00. Joint membership with the Suffolk Ornithologists’ Group: Individual members £26.00; Family membership £30.00.

As defined by the Constitution of this Society its objects shall be:

2.1 To study and record the fauna, flora and geology of the County

2.2 To publish a Transactions and Proceedings and a Bird Report. These shall be free to members except those whose annual subscriptions are in arrears

2.3 To liaise with other natural history societies and conservation bodies in the County

2.4 To promote interest in natural history and the activities of the Society

For more details about the Suffolk Naturalists’ Society contact: Hon. Secretary, Suffolk Naturalists’ Society, c/o Ipswich Museum, High Street, IPSWICH, IP1 3QH. Telephone 01473 433550

The Society’s website is at www.sns.org.uk

By kind permission of Anne Beaufoy

By kind permission of Anne Beaufoy