11 minute read

Nocturnal Migration: Phil Whittaker

Phil Whittaker

Since 2018 I have been recording bird calls in the night sky on favourable evenings from my garden in the Gipping Valley in Mid-Suffolk. My recording sessions have focused on the spring and autumn months, or occasionally in response to weather events that might perhaps induce weather-related movements. Migrating birds fly over Suffolk on a broad front and it is not necessary to live on the coast, or a migration flyway, to be involved in recording nocturnal flight calls.

I must stress that I am not expert at this activity; there are many other enthusiasts involved in this who have a better knowledge and skill at identifying calls and reading spectrograms and processing than I have! I am very much a beginner on a steep learning curve with much still to learn. The process has become known, and abbreviated, as Nocmig or NFC (Night Flight Calls) and more and more birders are becoming involved nationally and internationally in night-time recording from gardens, in both urban and rural areas. It is easy on autumn evenings to sit in your garden and pick up by ear the ‘tseee’ calls of Redwings Turdus iliacus passing over for short periods of time, but much less easy to cover a full ten hours of passage through the night. Nocturnal recording can fill an important gap in our knowledge of the fascinating phenomenon of bird migration. Night flight recording allows analysis of a full night of calls at leisure on the following day or whenever you please. It is essentially birding whilst you sleep!

Equipment and Recording

Many birders I have talked to about my experiences have said that it sounds “too technical” or” I’m no good with computers”. I must admit that I was initially cautious when I started, especially when I looked at a series of daunting-looking spectrograms and was confronted with the prospect of using audio processing software and recording hardware. It can, however, be quite a simple process, albeit a very time consuming one! There is also a wealth of online advice and support that helps considerably.

You can start recording birds at night for free with a mobile phone (what can’t you do with a mobile phone?) and a computer using free, downloadable, Audacity sound-processing software.

My recording set-up is quite basic, and cost-effective compared with some that I have seen. I use an HTDZ shotgun microphone, £20 from eBay, linked to a Tascam DR-05 Recorder, cost £70. I power this through the long hours of night with a Pebble ancillary battery which I have used for many years as a back-up to charge my phone. I did a bit of DIY to fit the microphone in a plastic pipe with an attached spike that temporarily fixes it into the ground. I put the recorder in a weatherproof bag, switch it on and leave it out, usually, from just after sunset, often until past dawn.

A computer/laptop is required for the processing of the resulting recording and, although not essential, a set of headphones can be useful, especially with faint, or distant, calls. I find it useful to have a good set of external speakers linked to my laptop which allows additional volume control of faint calls. I have experimented with linking up my microphone to dustbin lids, large flowerpots and mixing bowls to try and replicate a parabolic reflector and improve signals from the night sky. As there was no discernible improvement, I now just use my shotgun microphone as a stand-alone (see picture below). A Parabolic Reflector is the, ‘state of the art ‘, microphone for capturing bird calls; I might get one if my interest develops, but they are expensive! All of the equipment that I use is easily transportable and can also be used in the field for daytime recording.

Photo1: shotgun microphone, recorder and battery pack in situ.

Processing and Identification of calls

Once made, a recording is loaded into processing software via a laptop.

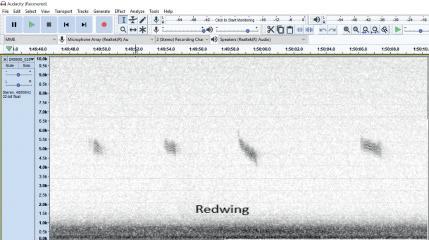

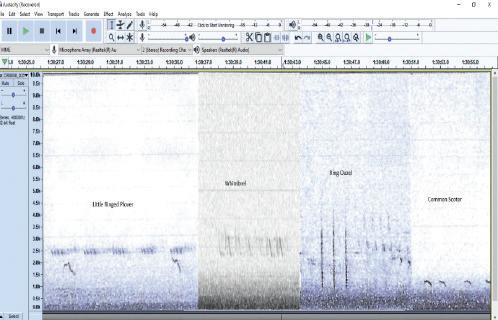

The programme used for processing is Audacity which is multi-platform and a free download. It is relatively user-friendly. After adjusting a few basic Audacity settings, the real fun begins! I scan through the resulting night-hours of recording, visually searching the screen panels of spectrograms on the laptop for visual signs of calls and then listening to them. A spectrogram is basically a picture made of sound. I find the filters available on Audacity particularly useful for removing road noise and other unwanted sound interference which can obscure calls especially at lower frequencies. Some calls quickly become obvious on screen and I have recorded Redwing calls that appear to be almost jumping down my microphone, but others can be very faint and easily missed when scanning hours of recordings. Faint calls can often be identified easier when heard through headphones. It can take between two and three hours or more to process a session after a busy night. This is not done in real time as Audacity allows the process to be speeded-up on screen so that eight hours of recording can be scanned in perhaps two hours.

Analysing calls and spectrograms initially proved very time-consuming. Unfortunately, where I live noise pollution is a problem throughout the night. I live between a busy trunk road and main line railway route, with a military base quite close, so I was confronted with some very strange sounds such as car horns, vehicles braking, train brakes squealing and helicopters, which initially took time to work out and then discount! Also add to this, when sifting through recordings nonavian residents such as rodents, foxes, deer, cows, barking dogs and sheep, all calling within microphone range. Initial spectrograms and sounds of this night-time cacophony caused much confusion, but after many hours of scanning recordings I have started to become better at discounting most irrelevant noises. There is always lots of electrical activity cropping up on my processing screens and I often have no ideas as to what it is!

Photo2: Audacity Screen capture

Not being expert at identifying bird calls did not help when I started analysing recordings, but that is partly why I started this journey and I have improved in ability through this experience, albeit slightly! It is still a ‘dark art’ for me in many respects and somehow quite different and totally out-of-context from hearing calls in the daytime. I soon realised that I was never going to identify every call. Xeno-canto is a useful resource; it is an accessible online sound library which provides welcome opportunities to search and listen to calls and compare spectrograms of species that are being considered for identification. Following other birders who are involved on Twitter and Trektellen also provides a useful resource as it is surprising how many birds of the same species are logged at different sites throughout the country or in Europe on the same nights.

Bird call sonogram correlation software that can do all of this for you does exist, but I believe that it is far from comprehensive and is, at the present time, expensive.

Unsurprisingly, I find some calls and spectrograms impossible to identify, especially ‘single calls’ which can be extremely difficult. It took me quite a while to get to grips with migrating Song Thrushes Turdus philomelos and Robins Erithacus rubecula which emit single high-pitched calls. Even the most experienced Nocmig enthusiasts regard night-flight call identification as a ‘work in progress’ with knowledge still developing. Social media has been useful for me in this respect, as much knowledge and debate is freely shared in relation to specific nocturnal calls. I have spent hours considering and re-considering intriguing calls, discounting them as unidentifiable, then returning to them over and over and asking myself whether could they could be a rarity? Is this a bird? Or just electrical interference? I have a computer folder full of these and maybe I shall one day get around to identifying some. It still surprises me how difficult it can be, for instance, to differentiate the sonograms and recorded calls of Whimbrel Numenius phaeopus and Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis which are quite similar unless heard well.

Weather, timings and seasons

Weather permitting, I usually aim to make at least one recording a week during migration periods. I have tried recording a few times outside of key times of passage but with only minimal success.

The most fruitful nights have been ones of constant low cloud when birds passing over are probably forced down nearer the garden. Clear nights are generally less successful, as birds are usually passing at higher levels, out of my equipment’s range. Wind and rain should be avoided as there is far too much interference and risk of equipment damage. I am beginning to get a feel for what will be a good night by careful considerations of weather forecasts before deciding to record. Just like day-time birding!

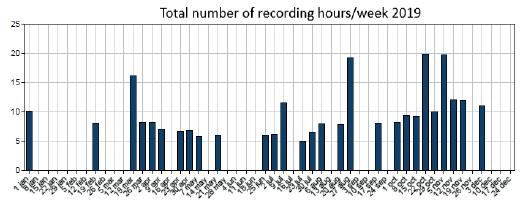

The above graph shows the weekly totals of my hours of recording in 2019.

Outcomes

I have logged and saved all of my counts on the Dutch migration site Trektellen which links directly to Birdtrack in Britain. Some of these records have contributed to this edition of Suffolk Birds. These data go automatically to the three Suffolk Bird Recorders from this site and it has proved a time-saving and efficient way of submitting records.

Over the two years I have been recording, I have never had a blank night with no calls (except once when I didn’t turn my recorder on correctly!) - there’s always something calling even if it’s only Coots Fulica atra and Moorhens Gallinula chloropus.

During spring and autumn 2019 I logged significant Redwing passage, with good numbers of migrant Blackbirds Turdus merula and Song Thrushes passing over throughout the night. My peak Redwing count was 332 on October 28th 2019 which is significant if you consider the range

that my basic microphone can cover which is only the small amount of sky above my garden. How many passed over the whole of Suffolk during that night?

Scarcer birds recorded have included: Ring Ouzel Turdus torquatus, Whooper Cygnus cygnus and Bewick’s Swans Cygnus columbianus, Common Scoter Melanitta nigra and Long-eared Owl Asio otus. The latter species was a possible migrant, as I have only recorded them in the autumn, but surprisingly two years running so far, but only on a few consecutive nights.

Waders have featured: Whimbrel, Redshank Tringa totanus, Dunlin Calidris alpina, Little Ringed Plover Charadrius dubius, Common Actitis hypoleucos, Green Tringa ochropus and Wood Sandpipers Tringa glareola and Golden Plover Pluvialis apricaria all passing over.

My main objective has been to record migrating nocturnal bird calls, but I am also interested in local species that call at night. I rarely see Barn Owl Tyto alba in my area these days but I have recorded them more times in 2019 than I have seen them. This included one Barn Owl that sounded like it was attacking my microphone, possibly being attracted to its furry wind muffler. It can be surprising how many birds call through the night and not just owls: Blackcaps Sylvia atricapilla, Cetti’s Warbler Cettia cetti and Skylarks Alauda arvensis are just some of the many species that have performed well for me during the hours of darkness. It surprised me that Skylarks here usually start off the dawn chorus, often well before any other birds. As many of my recording sessions have extended past sunrise, it is also a great way to experience the dawn chorus without getting up early.

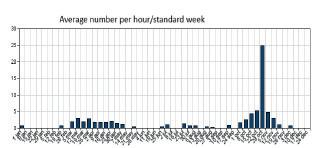

The graph shows the average number of calls of all species recorded on an hours/week basis with peak activity in late October.

Conclusions

Through persistence, nocturnal recording can become an interesting and rewarding activity. It provides many valuable insights into the often unseen spectacle of night-time migration. Also, from my perspective, it has enhanced my knowledge of birds both passing over Suffolk and over my local inland patch. In the two years that I have been involved, I have added quite a few yearticks and even a few patch-lifers! It has also improved my ability to recognise a wider range of common and scarce bird calls in a nocturnal context which is completely different from the daytime experience.

Hopefully, there will be more exciting nocturnal ‘finds’ in the next few years, as who knows what will pass over Suffolk in the nocturnal hours on any given night?

Online Resources:

There are plenty of resources to help the aspiring, and experienced, nocturnal-sound recordist available online. The following are some that I have found most useful:

audacityteam.org : an accessible programme which is free to download and cross-platform. Designed for processing and editing music projects, but equally appropriate for processing bird calls after a few minor ‘tweeks’ of its settings.

nocmig.com the team running this site are a fountain of useful information and it is indispensable for anyone considering, or actively involved and experienced in, nocturnal recording. The standardised protocol for recording nocturnal monitoring which can be seen on this site provides a useful framework for structuring a programme of recording. Technical advice on appropriate settings and processing calls with Audacity proved invaluable when I started.

soundapproach.co.uk: useful advice on every aspect of the process of nocturnal recording and frequently updated with new approaches and innovative ideas.

trektellen.org: an online platform for entering and saving recorded data and checking out what other enthusiasts are hearing in Britain and throughout the rest of Europe. Links directly to Birdtrack if appropriate permission is sought from BTO.

xeno-canto.org: a comprehensive library of world-wide audio bird calls and accompanying spectrograms. Also contains excellent advice about using Audacity and extensive nocturnal recording advice forums.