11 minute read

Peter Kennerley

Eastern Yellow Wagtail Motacilla tschutschensis at Dingle Marshes and Corporation Marshes, Dunwich, November 7th to 19th: New for Suffolk

Paul Green and Tom Williams

October 25th, 2019 had been a fairly ordinary working day that involved checking the Konik ponies and the water levels in the reedbed at Dingle Marshes, Dunwich. With lunchtime approaching, Paul Green decided to walk to the beach and on reaching the shingle ridge almost immediately heard what sounded like the call of a Western Yellow Wagtail Motacilla flava. Scanning the beach, he soon located what he took to be a Yellow Wagtail feeding around the edge of the saltmarsh. No sooner had he done this than it called and took flight, flying south and calling frequently before landing out of view in the middle of the grazing marsh. He thought that the call sounded quite ‘sharp’ and slightly different from the typical flight call of Yellow Wagtail with which he is familiar. With the bird having disappeared he phoned David Fairhurst for a chat, mentioned the wagtail to him and put the news out as a Western Yellow Wagtail. This sighting generated little interest within the Suffolk birding community and realistically I didn’t expect that it would be seen again.

Fast forward to November 7th. Paul Green’s final job of the day was to check on a contractor who was re-profiling the pools and ditches on the reedbed edge at Dingle Marshes. Tom Williams, the newly-appointed RSPB intern accompanied Paul and, fortuitously, happened to have brought along his camera. As we approached the digger, Tom shouted, “Yellow Wagtail”. We both heard it calling as it flew towards the disturbed earth around the working excavator. Tom managed to get several images of the bird and filmed a short video sequence using his phone before we left. That evening, the photographs and the video sequence were widely circulated. Opinions were divided but by late evening the consensus was that it was ‘just’ a Western Yellow Wagtail, albeit on a very late date for this species.

Peter Kennerley takes up the story

Early the following morning, Peter Kennerley visited Corporation Marshes and located two wagtails in the marsh by the edge of the shingle beach, in the exact location where Paul Green found the original bird on October 25th, and some 700 m from the previous day’s sighting at Dingle Marshes. Over the course of the morning he obtained a series of photographs (plates X and Y) and sound recordings of both wagtails (figs. 1 and 2); these established that one bird was Eastern Yellow Wagtail M. tschutschensis and the other was Western Yellow Wagtail. The news was released that both species of Yellow Wagtail were present. Shortly afterwards he was joined by Steve Abbott, Nick Mason and Kenny Musgrove who had been searching for the wagtail at Dingle Marshes where it had been seen the previous day. Together, they were able to appreciate the differences in the calls and plumages of the two wagtails.

Subsequently, both wagtails remained faithful to their favoured spot on the edge of the saltmarsh at Corporation Marshes and were enjoyed by many hundreds of visiting birders. Many had the opportunity to study them side-by-side and, crucially, to appreciate the difference in their calls. Some observers reported that three wagtails were present but no evidence has emerged that satisfactorily demonstrates this to be the case.

Identification

Both species of Yellow Wagtail and their many distinctive sub-species exhibit considerable plumage variation. In the breeding season, identifying adult males to a particular race is generally fairly straightforward and it is also possible to clinch the identification of some females. Variation and intergrades between races can produce some birds that defy identification, and outside of the breeding season, when sub-species mix freely, it is generally considered unsafe to assign any other than adult males to a specific race. Thus, identifying an individual in first-winter plumage to a particular race is particularly difficult, and establishing the identification in a late-autumn, vagrant context based on plumage characters alone is not possible.

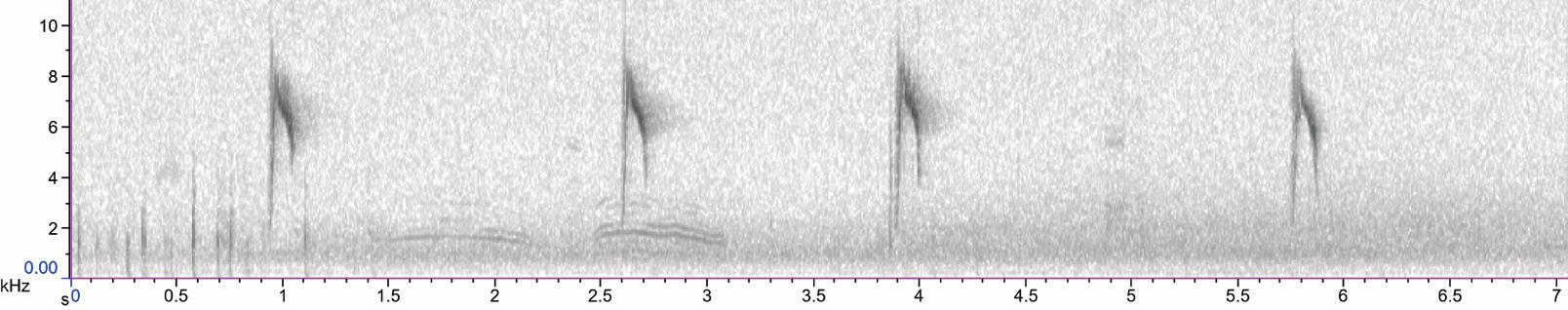

Fortunately, the flight calls of Eastern Yellow and Western Yellow Wagtails differ and this difference is widely accepted as being diagnostic (Bot et al. 2014). Observers of the two wagtails at Corporation Marshes were in the fortunate position of being able to hear these flight calls, at times in quick succession, and appreciate the subtle but diagnostic differences; that of Eastern Yellow had a distinct rasping, buzzing quality which it gave multiple times in flight, and usually called when arriving and departing (fig 1; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/186816921). In contrast, the Western Yellow Wagtail gave a thinner, weaker flight call (fig. 2; https://macaulaylibrary.org/ asset/187895981).

Fig. 1. Sound spectrogram of the flight call of the Eastern Yellow Wagtail Motacilla tschutschensis. Recorded at Corporation Marshes, Dunwich, on November 8th 2019. Four calls given in quick succession as the bird flew and landed. Peter Kennerley

Fig. 2. Sound spectrogram of the flight call of the Western Yellow Wagtail Motacilla flava, recorded at Corporation Marshes, Dunwich, on November 8th 2019. This bird typically gave a just single call in flight, and this spectrogram illustrates four separate sequences, three of a single call and one in which two calls are given. Peter Kennerley

Bot et al. (2014) provided a useful and detailed discussion of the identification of Yellow Wagtails and suggested other features that might be useful in the separation of Eastern Yellow and Western Yellow Wagtails. These included Eastern Yellow having a longer hind claw and an eye-ring that is broken below the centre of the eye, but they concluded that first-winter Yellow Wagtails are extremely variable and cannot usually be assigned to either species based on morphology alone.

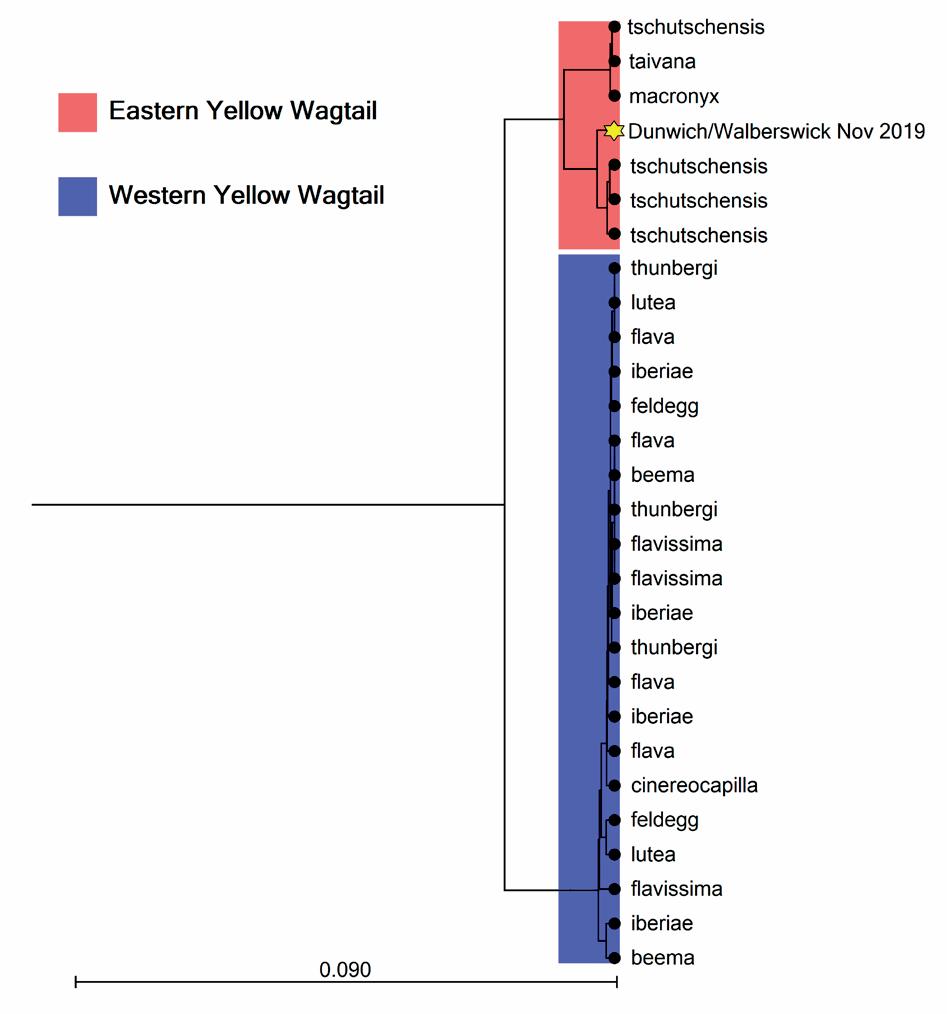

During its prolonged stay at Corporation Marshes, a faecal sample from the Eastern Yellow Wagtail was collected and sent to Dr Martin Collinson’s lab at the University of Aberdeen. They were able to extract DNA from this and Thom Shannon, PhD researcher, commented that: “we managed to retrieve 233 bp of mitochondrial control region sequence. This came back as 100% match for multiple M. tschutschensis sequences of known provenance, which alone confirmed the identification. When we then factored in all Eastern Yellow and all Western Yellow Wagtails sequenced in Genbank, the Dunwich bird was a 98.3–100% match for all Easterns, compared with a 93.8–97.4% match for all available Westerns. All other Motacilla taxa could also be excluded.”

Thus, the identification of the Eastern Yellow Wagtail was initially based on comparison of the flight calls and their sound spectrograms, with the details in Bot et al. (2014) proving essential. Some months later, further confirmation was forthcoming based on mtDNA sequence (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Cladogram illustrating the position of the Eastern Yellow Wagtail Motacilla tschutschensis at Corporation Marshes, seated firmly within the Eastern Yellow Wagtail clade.

Range and other 2019 occurrences

An exceptional arrival of Eastern Yellow Wagtails into Britain occurred in autumn 2019, with reports coming from Anglesey, Essex, Isles of Scilly, Norfolk (2), Northumberland and Suffolk (2), between September 25th and December 23rd. Europe also experienced unprecedented numbers in autumn 2019 and into winter 2019/20. Three were found in Sweden between October and December, two in Norway in November and December, and one reached Ireland in January 2020. Farther afield, two were found on Fuerteventura, Canary Islands, in November 2019 and February 2020, and one was on Malta in December. Most extraordinary, however, was the discovery of 13 first-winter birds in a rice field near Vila Franca de Xira, Portugal, on February 8th 2020. Most of these claims were sound recorded, though not all have yet been accepted and some await a decision by the relevant national records committees.

Eastern Yellow Wagtail breeds widely throughout eastern Asia, from upper Yenisei river in central Siberia east to Kamchatka and south to northern Mongolia, northern China and northern Japan. Its range also extends into North America where it breeds in western and northern Alaska and northern Yukon, Canada. It migrates throughout eastern Asia and winters in southern China and throughout southeastern Asia, the Philippines, and Indonesia and south to northern Australia. Within this vast range, four races are recognised that fall within two sub-species groupings; the northern pair of M. t. tschutschensis and M. t. plexa, and a southern pairing of M. t. taivana and M. t. macronyx.

Discussion

The Eastern Yellow Wagtail preferred to feed along the edges of the pools and generally kept out of the longer grasses favoured by the Western Yellow Wagtail. It occasionally flew onto the shingle, sometimes joining the Snow Bunting Plectrophenax nivalis flock. It wasn’t as confiding as the Western Yellow Wagtail; 25 m was about its limit before it became nervous and backed off. The two wagtails kept apart and were generally not seen side by side. Furthermore, neither wagtail associated with the Meadow Anthus pratensis and Rock Pipit A. petrosus flock in the marsh, but the Eastern Yellow Wagtail tended to fly when the pipits flew and on a couple of occasions it flew towards Dingle Marshes and disappeared, but returned again within 30–45 minutes.

The flight call was so distinctive that when the bird returned after being absent, it could be heard and recognised as being different from that of Western Yellow Wagtail before the bird was located in flight or had alighted. Those who heard the flight call remarked on how distinctive it was, and how unlike that of Western Yellow. It was aged as a first-winter bird based on retained juvenile greater coverts and tertials, and some replaced median coverts.

Remarkably, another Eastern Yellow Wagtail was discovered by David Fairhurst on Havergate Island on November 12th. Even more remarkable, this bird was also feeding around an active digger that was reshaping the earthworks there. This bird shared a similar rasping flight call but the plumage was a monochrome grey-and-white, lacking the green, yellow and brown tones of the Dunwich bird; it remained on Havergate Island until at least February 13th 2020.

The Western Yellow Wagtail

Surprisingly little mention has been made of the Western Yellow Wagtail that accompanied the Eastern Yellow at Corporation Marshes. Also in first-winter plumage, the combination of pale grey crown, nape and upperparts, and white supercilium, loral region and breast (the latter still retaining some dark juvenile feathering) created a monochrome appearance, offset only by vivid yellow undertail-coverts. It was often quite confiding, allowing an approach to within 15 m. When disturbed it typically flew a short distance without calling and alighted again within 25 m. When it did call, this was limited to just one or two weak calls in flight (fig. 2). It preferred to keep within cover, walking through grasses rather than in the open as did the Eastern Yellow Wagtail.

Western Yellow Wagtail, Corporation Marshes, November 8th Peter Kennerley

Grey-and-white Western Yellow Wagtails are rare in Europe. Aymí (1995) found 59 greyand-white birds in a sample of 5816 trapped birds at the Ebro delta, Spain, and noted that a similar study by Persson (1984) reported only 0.1% in a sample of 20000–40000 in Sweden, though their frequency increased in late autumn. Farther east, grey-and-white birds become increasingly common, with between a quarter and one-third of first-winter M. f. beema (which breeds in central Asia and winters in the Indian subcontinent) being grey-and-white (Bot et al. 2014). An internet search failed to reveal an identical bird in Europe or Africa, but images of similar individuals of the race beema wintering in India appear on Oriental Bird Images http:// orientalbirdimages.org/, although none is an exact match with the Corporation Marshes bird.

It is unlikely that this Western Yellow Wagtail can be assigned to a particular sub-species, nor is it possible to determine where it fledged, and an intergrade between two races remains a possibility. However, November is exceptionally late for a Western Yellow Wagtail in Britain, and an Asian origin is perhaps most likely.

Acknowledgements

We should like to thank Thom Shannon, University of Aberdeen, for providing details of the DNA analysis which supported the identification of this bird as Eastern Yellow Wagtail.

References

Aymí, R. 1995. ‘Grey-and-white’ Yellow Wagtails in western Europe. Dutch Birding 17: 6–10. Bot, S., Groenendijk, D. & van Oosten, H. H. 2014. Eastern yellow wagtails in Europe: identification and vocalisations. Dutch Birding 36: 295–311. Persson, C. 1984. Bestämningsproblem 1: Om svårigheten att skilja avvikande gulärlor från citronärlor. Fågelstudier 2: 81–82.

Eastern Yellow Wagtail https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/186816921

Western Yellow Wagtail https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/187895981

Footnote

Philip Murphy has made us aware of the excellent article by Adam Rowlands written in July 2016 – BBRC and Yellow Wagtails (British Birds 109: 389 – 411).

This article clearly sets out the key features that BBRC requires to confirm the identification of vagrant races of Western Yellow Wagtail, and of Eastern Yellow Wagtail. Adam refers to the wagtail that was present at Minsmere between October 17th and November 14th 1964. This bird was identified as being a Citrine Wagtail – this was accepted by BBRC at the time but in 2016 this decision was reversed. The only photograph shows that it is not a Citrine Wagtail and Adam states that “The grey-and-white plumage and late date indicate that this may well have been an Eastern Yellow Wagtail”.

And what of the Yellow Wagtail at Minsmere between November 16th and December 8th 1967 that was claimed to be M. f. simillima – not accepted by BBRC?