WE LIVE OUT HERE

In a time of growing intolerance, polarizing politics and aggressive invasion, a united path forward seems all the more perilous. Still, we firmly believe in the power of community journalism & modern storytelling campaigns to bridge divides and amplify the diverse voices of our local social innovators.

The backbone of our editorial is our in-depth interviews with community changemakers who prove their influence toward positive lasting change – from addressing social inequality to saving the planet from environmental ruin.

By representing the diverse voices of our local social impact leaders, we can creatively and critically encourage greater collaboration and help find our common human ground in what can feel like an increasingly divisive environment.

If we estimated the time of all the interviews we recorded for this issue, it would total about 180 hours. That’s the equivalent of spending one week, day & night, in meaningful, thought-provoking conversations with communities’ dreamers and doers. We learned that enacting longlasting change requires all sectors of society to work for a shared mission with a system of accountability in place. But what really stood out was the repeated theme of choice.

Researchers estimate an adult makes about 35,000 conscious decisions a day, and the more we make, the more likely we experience decision fatigue. But sometimes, that fatigue sets in when people believe willpower is a limited resource. This is the lightbulb moment.

In this new issue of Impact.Edition magazine, you’ll meet humans who’ll fuel your willpower to ask and answer: Do I minimize my carbon footprint? How do I feel, really? What sustainable development goals can I address? Do I take nature for granted, or have I realized my responsibility to protect a fragile ecosystem? How do I

connect to the land I live on? What do I know about coral bleaching and how to stop it? Do I shop sustainably? What happens to my plastic trash, and where do I compost my food scraps? What's the history I preserve? Do I belong or exist?

Our big & small decisions move our communities to be healthier and more sustainable. We can elect to discover our history & ecology, meet new community champions, and find volunteering opportunities.

Achieving collective impact starts with meaningful communications, and this is the choice our small (yet mighty) volunteer editorial team makes: to produce community journalism and creative storytelling campaigns, so that your choices are clearer.

It is our sincere hope you enjoy reading this newest collection as much as we did while producing it.

With love, peace, & gratitude, Yulia & Samantha

Yulia Strokova, Founder & Publisher

Samantha Schalit, Editor-in-Chief

Juan Ortega, Art Director

Greg Clark, Photographer, Good Miami Project

Kacie Brown, Social Impact Writer

Anjuli Castano, Social Impact Writer

Sofia Zuñiga, Contributor

Impact.Edition is a nonprofit community media that empowers people with best practices and creative solutions for a more just, more sustainable world. Impact.Edition print magazine (ISSN 2832-4706) is published twice per year. Articles proposals, advertising, and reprints go to impactedition.org.

Solutions to our world’s biggest problems start locally and get done when there’s a system of accountability. Building the just, equitable and sustainable data ecosystems that showcase best practices and effective governance requires time, resources and a mindset shift: changing the world is a team sport. Meet Miami’s SDGs Consortium, a collaborative and inclusive space for impact leaders eager to drive social, environmental and economic progress.

by Yulia Strokova, Samantha Schalit

by Yulia Strokova, Samantha Schalit

Alejandro Burgana manages OBE Power, the nation’s second-largest electric vehicle-charging network. Sandra Louk LaFleur drives Changemaking Education and Social Innovation at Miami Dade College. Sam Ligeti is a program experience coordinator with Venture Café Miami. Cesar S. Murillo works with Emergent Global Investments. Andreina Weichselbaumer is a director of culture & strategy at Radical Partners. Two years ago, this group of diverse and committed leaders had likely never met before, and now they are part of a new social impact acceleration ecosystem born in Miami – the SDGs Consortium, a collaborative and inclusive space for impact leaders eager to build on their commitment to social progress, economic growth, and environmental protection.

During her career, Scarlett Lanzas, founder of the SDGs Consortium, worked in diverse areas ranging from the United Nations World Food Programme to social innovation, leading Puentes New Orleans, a nonprofit focused on developing economic and leadership-building

It’s no longer an option. It’s a musthave instrument. Governments, companies, academia, schools, and entrepreneurs must start adopting the UN Sustainable Development Goals, which offers a holistic, measurable and proven framework of interdependent economic, social, and environmental objectives that is being implemented in over 185 countries and thousands of cities around the world.

initiatives for Latinos. Today, she leads Accountable Impact and works tightly with Claudia Akel, founder and CEO of Social Impact Movement, to advance sustainable goals and strategies in Miami.

Claudia and Scarlett are true SDGs champions who, for years, have been educating and challenging our local leaders to make sustainable choices in our governments, businesses, and communities. Last year, Claudia and Scarlett also launched the SDG Impact Pledge to ignite authentic and meaningful collaboration among businesses in Miami to adopt the SDGs.

In 2015, the UN announced the SDGs as a call to action for countries, governments, funders, and investors to unite to accomplish 17 global goals to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure prosperity for all. The UN has outlined specific indicators to measure progress and a timeframe to achieve them by 2030, both of which help drive a shared understanding and urgency of this work.

Despite our officials’ and established foundations’ reluctance to speak the SDGs language — the goals are persistently absent from officials’ speeches, and rarely referred to or integrated into foundations’ impact reporting or social media — there are individuals, businesses, educational institutions, and community organizations in Miami that are working to affect change and elevate local-level, community-led societal advancements in the context of the global sustainability agenda.

“Miami is my home, and I want to make sure that our children and our children’s children can live and thrive in Miami,” says Scarlett. Originally from Nicaragua, she has lived in Miami for over 20 years. “I wish, and I hope that my nephew, in 10 years, when he becomes a doctor, can come down here, and either start his own practice or work at a hospital, and have a good, healthy life.”

While Miami makes headlines as the land of opportunity for tech and innovation, we’re still battling gender and racial bias and the rapidly occurring and increasingly drastic effects of climate change. In Miami-Dade County, sea levels are projected to rise by more than 15 inches in the next 30 years, increasing flood risk further inland and with greater frequency. Communities of color will likely bear the heaviest burden from the changes brought by climate change, including more deaths from extreme

heat and property loss from flooding. And although hundreds of separate initiatives are underway to address all these problems, we won’t scale our impact without an infrastructure of accountability and a collaborative mindset trained on inclusive and sustainable solutions.

“The United States is among five countries, including Haiti, Myanmar, South Sudan, and Yemen, that have never presented a Voluntary National Review, which is a self-assessment of the implementation of the SDGs; other countries started their VNRs in 2016,” notes Scarlett. “This lack of accountability must be challenged at every level. The only way to build a system that holds entities accountable is by creating mechanisms of collecting and reporting local data.”

Scarlett was “blown away” by the City of Doral’s ISO Smart City Certification, which requires an investment in high-tech infrastructure that collects, crunches, and delivers data to residents and businesses. In 2016, Doral solidified its Smart City status by obtaining Platinum Level certifications from the World Council on City Data, which includes over 100 measures based on international standards for smart and sustainable cities. Doral is the only city in Florida to achieve this certification, and through this internationally recognized third-party certification, Doral joins a network of cities like Boston, Dubai, Amsterdam, London, and Shanghai, adopting a culture of data to drive innovation. In 2021, Doral became one of only 10 cities in the world, and the first in the United States, to acquire the ISO 37122 certification for Sustainable Cities and Communities. In addition, the City of Doral has collected data aligned to the SDGs Cities.

Another Florida city that stands out in sustainability and reporting is Orlando. It’s the fourth city in the nation to complete a Voluntary Local Review of Progress on SDGs.

Scarlett envisions Miami’s progress on reporting and accountability coming to fruition through the SDGs Consortium, which is devoted to three pillars of sustainable development: Social Progress, Environmental Protection, and Economic Growth.

Solutions to our world’s biggest problems start locally and get done when there’s a system of accountability. Impact.Edition is proud to join Catalyst 2030, a global movement of people and organizations coming together across borders and cultures to confront the world’s most pressing problems. By collaborating in deep and meaningful ways, we can strengthen local advocacy by connecting it to the bigger story.

From the beginning, Impact.Edition stories track local initiatives that’ll bring us closer to achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. The 17 goals outline measurements for progress and a timeframe to achieve them by 2030.

Our SDGs partners:

Scarlett continues, “We’re building an interdisciplinary and multisectoral, collaborative space for diverse groups of individuals and entities to co-create a common and sustainable agenda for all. They are all committed individuals, entities that care about Miami, and that really want to drive progress, and make sure that our children and our children’s children can live and thrive in Miami. We’re going to create a data infrastructure and, more specifically, a powerful communityled and open-source data platform where all the entities that are joining the Consortium can share data, produce reports, and effect change.”

Data holds power to tackle society’s greatest challenges and improve lives across the globe, but our institutions must invest in analyzing that data, extracting insights, and acting on them. This transformation and impact will not happen overnight; it’s a long journey. Building just, equitable, and sustainable data ecosystems requires a collaborative mindset, time, and resources to define standards, showcase effective governance and model best practices to drive social, environmental, and economic progress.

“We might not achieve all global goals at once, but as former UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon said, our struggle for global sustainability will be won or lost in cities. And I believe together, we can unlock a better future for Miami,” Scarlett says. “So, it’s up to us to implement those types of programs and policies to effect the change we need for current and future generations.”

Art by Miami-based visual artist Troy Simmons. Wynwood 2300 was nominated for a prestigious CODAaward, given to those who successfully integrate commissioned art into interior, architectural, or public spaces.

How can we reawaken our roles in urban design and reimagine our relationship with the land?

by Anjuli Castano

by Greg Clark, Good Miami

by Anjuli Castano

by Greg Clark, Good Miami

In the cool sunshine of South Florida winter, the Everglades National Park river of grass hummed with the vibrations from underwater life and distant airboats touring the park. That afternoon, I joined a group of artists, architects, environmentalists, and curious citizens who were there to learn about indigenous structures and cultural landscapes.

Symbiotic House, which researches and develops adaptive architectural solutions for Miami’s environmental challenges, organized an airboat ride to visit tree islands in the Everglades where chickees and other traditional structures, which survived years of hurricanes, remain. Our tour guide explained the historical significance of these home structures, the way they served as quick solutions for Seminoles migrating south from northern Florida, fleeing colonialism. The structures reflected the state of their builders who

needed little more than a roof and a firm foundation to rest on. The palm and cypress used in the construction echo the environment in which the structures were built, creating kinship between the natural and manufactured environments. As stewards of the land, the Seminole and Miccosukee people respect the interrelation between the human need to make place and the existing earth. Yet, within our urban fabric, only 40 miles away, this kinship is lacking.

Birthed into the generation of private transportation, metropolitan Miami has never known a world without cars. To make way, the industry paved through dense Seminole and Tequesta wetlands to lay the city grid, which domesticated the swamp and radically changed the people’s relationship to this land. What was once a coexistence of nature and humanity had turned into a uniform playground of driveways and avenues.

Miamians’ relationship with the city today is often transactional, attempting to mimic the very rich and the luxury-seeking travelers the city caters to. Its urban design is composed of car-centric streets, hidden residential parks, and private beachfront properties: commodities proven effective in amassing new residents, yet accessible to few. The vibe is exclusivity. Working-class locals know a Miami of scarce public space and limited modes of transportation. Learning the historical context of Miami’s trajectory to metropolitan mecca, I found myself wondering, who was Miami built for? What if we measured success as equitable access to social mobility, or the extinction of food deserts and heat islands?

By divesting from conventional ideas of progress, which champion vertical development, we can invest in people-centric horizontal development. Vertical

development, which aspires to maximize profit for private owners and encourages the consolidation of capital, is exclusive by nature. Horizontal development is inclusive. Think: converting vacant lots into public commodities, or redesigning large roads to accommodate promenades and bike lanes. If you walk through your neighborhood, you will surely find a space that can better serve your community if it’s reimagined and repurposed. Urban designers and developers may be the ones with the technical knowledge to turn an idea into reality, but residents know their communities’ needs better than anyone. Practice your imagination and expertise of your lived experience; they are powerful tools in urban place-making.

“Why don’t we turn this into something?” asked Meg Daily. She is the creative soul and brain of The Underline, the 10 miles of metrorail underpass that’s

being redesigned and reinvigorated as a linear park with bike lanes, walk lanes, green spaces, an urban gym, and so much more.

Meg is an avid cyclist, but after a cycling accident which left both of her arms broken, she had to reacquaint herself with the other means of transportation that were available to her disabled body. Once healed enough, she would take the metrorail to her physical therapy appointments. “There was something about slowing down and walking in a space rather than driving by it,” she said. Feeling a space goes beyond your interaction with the physical or tactile aspects of the area. What Meg felt in the immense size of the metrorail underpass was an opportunity to create connection and enhance the lives that pass by it. She spoke about the metro stations in New York, how you can get a cup of noodles, the latest paper or catch a live show along your daily commute. As Meg put it, “The transit can be a destination in its own right.”

As our modes of communication evolve and our desires to connect expand, so must urban infrastructure evolve as a means to connect. As Meg says, “We have to look at urban infrastructure as having different purposes over time.” The key is listening to citizens who interact with this infrastructure, as their insight is critical to good design, and good design fully considers how a space can benefit all who come in contact with it. For most of modern history, that was not the approach.

INFRASTRUCTURE IS EXPENSIVE, INFRASTRUCTURE IS MESSY, INFRASTRUCTURE IS NECESSARY.

Segregation By Design, a project that documents how communities of color have been historically impacted by discriminatory urban design practices, studied the construction of the I-95 interstate highway, which streamlined traffic through Miami-Dade but also “required the forcible relocation of over 12,000 residents — nearly 100% of them Black.” The construction of I-95 stemmed from the seed planted by motor lobbyists who successfully downsized Miami’s public transportation. The fruit of this labor is a minimal metro system and fractured bus routes. While this push to design Miami to accommodate a new type of private transportation touted adaptation to modern ways, it actually left a large part of Miami-Dade disconnected and isolated.

Today, we have to lean into the evolution of purpose. Throughout construction, leadership of The Underline held numerous community meetings, and more importantly, publicized them by going to “churches,

neighborhood associations, even hanging out at Publix to tell people to come,” shares Meg.

The progression of The Underline — from community input to design, construction, and communal enjoyment — is a case of successful cross-sectoral collaboration. During one community meeting, the sound of Miami residents cheering at the proposal of bocce ball at the Underline reverberated in the small Vizcaya meeting room. It wasn't just the excitement of another activity at the park that electrified the people in the room. Being asked, What do you care about? What do you envision in your park? and having those answers taken into account crafts a relationship between the people and their public place.

Ultimately, our greatest responsibility is our ability to respond. Aaron DeMayo, founder of Future Vision Studios understands that poor design exacerbates environmental issues and affects residents' quality of life.

“The causes from one system are having huge ramifications across the other systems as well,” Aaron explains. A clear example is our water system. He recalled a recent rain event that halted all traffic on I-95 because an additional four inches of water caused massive flooding on the highway. “South Florida has a complex, intertwined system of water management across various scales. From the stormwater drain on the corner of your street...to the rivers and canals that move water throughout all of South Florida. Our existence relies on that network of water infrastructure.” Miami’s relationship to water grows precarious as the years pass. As a city defined by water, how do we turn threat into opportunity?

As an architectural designer and urban planner, Aaron has been a champion of green roofs as a rudimentary and interdisciplinary response to challenges we face in the emergent climate. For Miami, these are landscaped areas strategically planted on top of buildings that provide topographical variety. These green roofs maximize our urban capacity to capture and filtrate stormwater runoff, provide green space to residents, and combat heat island effects.

Working in unison with the environment is not a radical idea. Aaron emphasizes that we have the infrastructure to move toward climate resiliency and spatial justice, citing urban projects that exemplify the tools and ingenuity available: like Brickell City Centre, an engineering feat of human comfort as its structure manipulates wind to keep the outdoor mall cool, or the Design District's thoughtful layout that diverts car traffic and protects its pedestrian paseos.

NATURE INTO CONSTRUCTION IN INNOVATIVE WAYS, WE CAN SOLVE A LOT OF THESE ISSUES THAT WE'VE CREATED OURSELVES.

And while innovating new, clever methods of climate-resilient design and construction requires much effort and creativity, we are not alone. Aaron emphasizes there are existing tools for the industry, like the LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification, an internationally-known green building ranking system, which supports responsible development. Adaptation is crucial. Ensuring locals adapt with us is non-negotiable, “because if we let them leave, if we show that we don't have plans in place to help keep them here, our community may start eroding.”

Urban planners, residents, and environmentalists are all calling for the same thing: collaboration. Tactical urbanism is the practice of using scalable interventions in neighborhood building and urban planning that harness the creative potential of social interaction. Miami natives Myke Lydon and Anthony Garcia, authors of the book Tactical Urbanism and founders of the firm Street Plans, use tactical urbanism in two ways: they create temporary plans for cities looking to change and produce guides for citizens to spearhead their own projects. “Both ways expand public engagement and break down communication barriers between cities and

citizens,” says Dana Wall, a senior project manager at Street Plans.

Dana shares the example of Slow Streets in her own neighborhood, Flamingo Park in Miami Beach. What was originally a one-month pilot program pushed by a group of residents, remains an effective method of traffic management and pedestrian safety that uses signs and lights to slow down drivers, and makes biking & walking more attractive. Now the City is revisiting the project to find ways to improve its durability. “This is the ideal progression,” says Dana.

The greatest advantage of a tactical urbanism approach is its humility to accept adaptation as a part of sustainable growth. Like the best teacher, a pilot program shows our shortcomings and tactical urbanism gives space to try again.

When working for spatial equity and comprehensive community development, we are deconstructing the limitations of ineffective, inequitable systems. In bureaucratic settings with little to no public voice, this progress is impossible. This especially happens in communities of color, explains May Rodriguez, the executive director of The South Florida Community Development Coalition (SFCDC). Through a lens of racial equity, May and her team examine how we're building communities and developing assets within them.

"Unfortunately, in our city, like many other metropolitan cities across America, inflation and the cost of living has increased astronomically, and not in a proportionate

The opportunity and the challenge is: how do we continue to expand those projects, let them grow organically where they make sense…so we can ensure that if people want to lead more car-free, pedestrian-oriented, healthy lifestyles, they're able to.

rate to our jobs wages. And so being able to generate wealth has been a very big problem, particularly for Black and brown neighborhoods. And so they tend to be under-invested in, they tend to be overlooked often. Until it's a matter of gentrification."

The displacement of the people is a displacement of the culture that makes the urban fabric of South Florida so attractive. As historian N.D.B. Connolly describes in his book A World More Concrete, it’s been happening since the legitimization of Miami as a city when the Black and brown people who built it were uprooted by wealthy developers and the tourist industry. The Florida lineage of native and Black communities fights for preservation every day. “Although these folks may take up less space in our communities, that doesn't mean that they have less value as residents, as business owners, and as contributors to our local economy,” says May.

SFCDC formed Public Land for Public Good (PLPG) to engage and empower residents to influence the future of the 19-acre Allapattah GSA Lot. When PLPG asked for the city to create a request for approval process, the organization cooperated with The Allapattah Collaborative and shared a survey with Allapattah residents. The results showed a real need for, of course, housing, but also necessary amenities like green spaces, which ranked first in the poll. Participants overwhelmingly answered “yes” when questioned if they would like to engage in the development of the lot.

Making people aware of their agency over their environments and lives should not be seen as a privilege but as the foundation for a healthy, interconnected urban fabric that values sustainability. Development is not inherently negative; removing people’s autonomy for the capital gain of a few is. “It's about minimizing and eliminating displacement altogether and figuring out ways in which we can still be pro-development,” May says. “But do it in such a sense that — first and foremost — takes care of the community needs that are already present before adding on additional opportunities.”

Hold The Line is an organization that demonstrates phenomenal success in engaging communities. In

less than a year, it has grown from 300 members to more than 5,000 individuals, organizations, and municipalities who pledged to protect our green space, farms, and drinking water from overdevelopment and urban sprawl.

“The Line” refers to the County’s Urban Development Boundary (UDB) that was adopted in 1983 to limit western expansion and protect the Everglades & local agricultural land.

We are highlighting issues that people can feel and touch. If you can get 10 or 20, or 30 people together, you can influence your city government, and if you can get 100 people together, you can influence your county government. By giving people a sense that this is achievable, we can make our voices matter.

Josh Groot Policy Director, Hold The LineWe can and should feel safe and welcomed in our city. We can foster connection and get to know each other not as island municipalities but as a cohesive urban organism with the collective goal of staying afloat and staying true to what Miami has always been: a place where dreams meet reality like water meets land.

by Greg Clark,

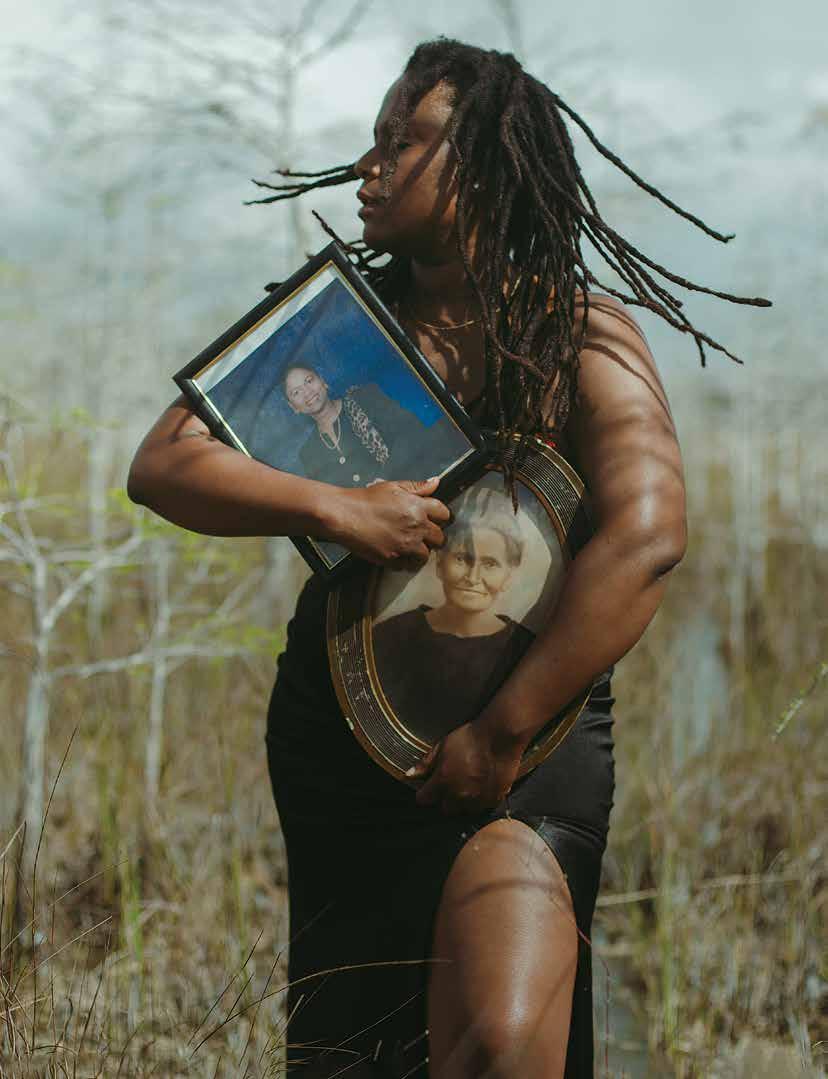

Growing up in Miami, Cornelius Tulloch had only visited the Everglades once. “I never really felt a tie to Florida as the state. Miami, it's kind of its own world.” As a young adult and emerging artist, he lived there for a month during his artist residency with AIRIE (Artists in Residency in the Everglades). Through his experience, Cornelius felt kinship with the river of grass and its history, and he found renewed purpose in telling its stories.

He was first inspired by the Florida Highwaymen: artists who painted the Florida landscape on coastal highways, defying the constraints of the Jim Crow era and pronouncing their influence through public art.

“And that's what I applied to AIRIE,” Cornelius explained, “to deal with the question how do I, as a Black artist, now taking up this space, begin to depict and learn more about Florida, through my artwork and through storytelling?”

For Cornelius, reconnecting and reclaiming Florida history meant forming a relationship with the Everglades

and adapting to the nature of the swamp. Through his Passages, Cornelius faced profound self-discovery that prompted his interest in drawing comparisons between the ways people connect with the land and the ways his peers experienced integration with surrounding cultures.

“A passage can be like a short story or excerpt of writing, or it can be literally a connection of land or water. This is how we begin to connect our stories in this landscape, the Everglades,” explains Cornelius.

Passages is the artful partnership between Cornelius and other 2022 AIRIE residents. The immersive exhibit showcased the residents’ talents in video, music, and poetry to transport viewers to the river of grass at sunset and acted as a portal to the inner parts of us that are mirrored in the ecology of the Everglades, inspiring a responsibility to know and care for the land.

“My key message was for us to look more deeply at the Everglades, not just as an ecological concern, but also

as a large cultural context: what happens when this landscape gets erased, and what stories aren't fully told?” emphasizes Cornelius.

Passages implicitly asked us to reflect on our own relationship to the Everglades in the moments of silence offered. The moments when the only audio is crickets, and you are surrounded by the digital landscape, and native plants serve as windows for contemplation. “It was finding that balance of telling the story but also allowing it to be something that isn't just flashy but meaningful in how people are able to engage with it,” continues Cornelius. It was this balance between artistic interpretation and environmental accuracy which bridged the audience to the landscape in a more personal way, and incited the same curiosity which inspired the artists of Passages.

“That's the beauty of this residency,"Cornelius shared. No one starts out as an environmental

activist, they're [not] about one sort of specific thing. But I think that genuine curiosity for this environment brought a lot of us there, and then we found ourselves communicating these stories that were unheard.”

The residents exposed how climate health is intrinsically linked to the survival of culture and history, and Cornelius begs the question: who is at risk when these spaces are in danger?

Living in the bustling urbanism of Miami, it is easy to forget our proximity to climate catastrophe. But as these issues grow more precarious, we must find ways to reconnect to these environments, which provide examples of resiliency and synchronicity. Passages exemplified the use of a creative and expressive medium to connect to this calling.

“Now we find ourselves in the Everglades all the time,” says Cornelius. And we should too.

You can say it in English, Spanish, Portuguese, French, or a combination of 20 other languages spoken here; Miami means home. Here’s a look at what it means for the city to house its wealth of diverse cultural communities and how we go from coexisting to thriving.

by Anjuli Castano

by Anjuli Castano

SoFlo Asians, a Facebook page for organizing meetups and creating social ties among the small Asian population in South Florida, was founded by Phong Luu as he adapted to a new city.

Feeling isolated can distort our perception of what community exists out there for us. But Luu proves that there is always community if we seek it.

The connections Luu built through SoFlo Asians introduced him to the National Association of Asian American Professionals (NAAAP) and led him to co-found a chapter in Miami. Since

then, NAAAP Miami has provided a digital and in-person communitybuilding platform for Asians in South Florida to find and empower each other as well as the cities they now live in.

This connectivity is not only happening among Asians but within and among all cultural diasporas in South Florida. The Miami chapter of NAAAP participates in the annual 10 Days of Connection by hosting a family-style picnic Luu described as an “opportunity for people to connect cross-culturally in a human to human way.”

WHEN I MOVED TO SOUTH FLORIDA SIX YEARS AGO FROM VIETNAM, I EXPECTED FOR THERE TO BE A SMALL ASIAN POPULATION; THAT’S WHY I NEEDED TO CREATE AN ORGANIZATION, TO BRING PEOPLE TOGETHER... I MADE MYSELF AT HOME HERE.

The 10 Days of Connection (May 1-10) is a collaborative movement that brings together social impact leaders, community organizations, and locals to step out of their comfort zone and join conversations on taboo topics in a safe environment. Produced by Radical Partners and powered by hundreds of leaders, the 10 Days of Connection is an open invitation to everyone to engage in acts of connection. Please visit 10daysofconnection.org for more information.

Feeling othered or disconnected from the place you reside obscures one’s connection to the community and challenges one’s ability to put down roots. It tests our resourcefulness and affirms communities need resources to build wealth that provides safety and security for this and the next generations.

Leonie Hermantin came to this country as a child with her younger sister to meet their mother in New York. She described her upbringing there as familiar; living in predominantly Haitian neighborhoods, her language and identity were never questioned. Coming to Miami was another experience of familiarity: moving into the historic neighborhood of Little Haiti, she saw signs written in Creole, another signal of recognition.

But, on settling into her new home, she says, “I realized we were not being treated fairly when it came to resources and inclusion. People around me were living in poverty and almost uninhabitable housing.”

In Leonie’s upbringing, and now in her position as director of development at Sant La, she has firsthand experience with the kind of unfair treatment Haitian migrants face. Fleeing from poverty, violence, and political instability, Haitian migrants have the lowest rate of asylum granted out of 84 national groups. Sant La served over 900 migrants in 2021, primarily Haitian asylum-seekers. The greatest frustration she says “is the people who have been granted status to stay in this country are not being granted access to the same survival resources extended to other migrant populations.”

South Florida has long been regarded as a melting pot of people because a wealth of cultures exist here. Yet, simply existing is not enough. We can’t excuse ourselves from examining and critiquing how accessible our communities’ resources are. We can’t excuse ourselves from a monitoring and accountability structure that ensures — on a continuing basis — all cultures in our community thrive equitably.

Given our country’s historical role in slavery, racism and class-based social structures, confronting how Black migrants are treated when trying to come to the US is a first critical step in building the infrastructure for Miami’s

cultural diasporas to thrive. Without that, Black migrants (and ultimately all migrants) will always struggle to heal from and combat oppressions.

Caribbeans all come from plantocracies, the apex was white people, and we still carry that with us.

Leonie points to how it's “difficult to get stories from Haitian refugees who come by boat because they are usually jailed. And jail is a big source of shame for us.” Still scarred by the 2021 images of Haitian refugees accosted at the Texas border and the reality that Black immigrants are still disproportionately at risk for deportation, it's critical to discuss how, we as a city, are going to redefine our acceptance of immigrants and create true diversity for a progressive world.

One way to have these conversations is to be bold in your approach and initiate sitdowns with the people you theoretically have little in common with. The result will usually be the revelation that you are not as different as you thought. We can see this in Shabbir Motorwala’s approach as founding member of the Coalition of South Florida Muslim Organizations (COSMOS). Any spike in conflict among Israel, Hamas-controlled Gaza and various Arab states causes ripples of cross-culture tension

throughout all Jewish, Palestinian and Muslim diasporas. During one such spike, Shabbir reached out to Jewish community leaders to meet.

The meetings are a commitment to each other that both communities will not let the hatred and conflict happening in the world spread into their communities in South Florida. Beyond these reoccurring touchpoints, leaders within South Florida’s Muslim and Jewish communities step up for each other in moments of tragedy.

When the mosque in Kendall was vandalized, Rabbi Solomon Schiff, the late Miami Interfaith leader, demanded it be called a hate crime. And in 2018 when there was a mass shooting in a synagogue in Pittsburg, there was a vigil held at the Jewish Holocaust Memorial in South Beach where COSMOS attended to show solidarity. Shabbir recalls when a reporter asked him why

Muslims were at the vigil. He explained, “if you attack a synagogue, or a church, it is like attacking a mosque; they are all places of worship.”

Originally from India, and as a Muslim immigrant, Shabbir has worked to take back control of the narratives that surround his Indian and Muslim identities by educating those around him. It's an effort that he says “creates understanding of Muslim culture, eradicating misconceptions and, in turn, unnecessary issues.”

We’re not going to be able to solve the problems in the Middle East, but we can work together to address the antisemitism and islamophobia happening in our home South Florida.The 10 Days of Connection, by Greg Clark, Good Miami

Building tolerance through education is one of COSMO’s core praxis with initiatives like Educating the Educators; in collaboration with the Miami-Dade Public School System, COSMO provides speakers to talk to students about Muslim culture and the common elements among Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. A different program, with MiamiDade College students, covers topics on Muslims’ contributions to science, medicine and math.

Learning about our similarities undoubtedly creates bonds amongst people. So does celebrating our differences. The GuatemalanMayan Center operates within this framework, dedicating their service to Mayan migrants, a majority non-Spanish speaking indigenous group, coming from Guatemala.

Fighting for acknowledgment of their difference is especially difficult coming from a region generalized en mass as Hispanic. Generalizing an entire region without consideration for the inevitable nuances among its cultural subsets leads to misunderstandings and mistreatment. Being on the receiving end of those misunderstandings and mistreatments is psychologically challenging and there’s no onerule-fits-all-cultures solution. But the place to start is creating communal space that builds resilience and a sense of pride in a culture’s own uniqueness.

Lindsay McElroy, a longtime employee of the Guatemalan-Mayan Center, explains the organization has “a long history of not only serving the people but advocating for them as well.” She shares how “a lot of the kids grow up ashamed of being Mayan and undermine their own uniqueness.” The Center is intentional in using storytelling and songs like The Mighty Mayan to instill confidence in the kids and inspire pride in coming from such a rich culture. “A lot of times, our families are alienated because not only are they immigrants, but they are immigrants who don’t speak Spanish as their first language.” In a society that considers Hispanic a monolith, finding representation is a struggle the Maya face every day.

“Even though there are a lot of cultural differences, people who seek help through the Center can all relate to the common ground of being an immigrant. No matter what country they come from, they have to advocate for themselves,” says Lindsay.

Our current systems of labor and social acceptance require self-advocacy, and in this reality, groups who advocate for each other find more strength and enact more change than those who remain isolated.

Florida Immigrant Coalition (FLIC) advocates for all who live under this struggle. Working with a long list of immigrant- and worker-centered organizations, all the member organizations represent the vastness and intersectionality of the immigrant struggle and identity.

FLIC dedicates itself to not only protecting immigrant rights through policy but also increasing local leadership representation. “What people call diversity is in itself a unifying quality,” Tessa says, and that comes to fruition when there is representation in government at state and local levels of all the immigrant groups that make up Florida. Tessa describes Florida as “practical but not progressive,” as more often than not, our representatives do not speak for us but for the practicality of business, of profitability. “This is where our diversity ends,” says Tessa.

The reality for many Floridians, documented or not, is that our sense of security is precarious. Yet we can find strength through the human ability to adapt and to learn from each other. South Florida’s diversity is often taken for granted but we are privileged of so many examples of people who overcome fear, inaccessibility, and misrepresentation to combat humanity’s most pressing issues.

Now, we must move with the time, answer the call to create communities where all cultures can thrive, or allow time to move us.

by Greg Clark, Good Miami

As the saying goes, the world is your oyster. But sometimes, the oyster (and other seafood we eat) absorbs toxins from man-made pollution. Knowing how and where your seafood is harvested might be the key to protecting our oceans and ensuring a long-term seafood supply. We met with Sarah Curry, founder of Sereia Films, who uses her skills and passion to tell stories of changemakers who impact the health of what’s in our waters and on our plates.

by Greg Clark, Good Miami

by Greg Clark, Good Miami

by Sofia Zuñiga

by Sofia Zuñiga

On the southwest coast of Florida, hidden on a 17-mile-long island, is a nine-year-old shrimp farm named Sun Shrimp. With her cinematographers, Daniel Kaplan and Dan Diez, Sarah Curry drives out to see the team of around 100 farmers in action and taste the garlic and butter shrimp sustainably farmed by Robin Pearl, the owner of Sun Shrimp.

Upon arrival, the film crew follows farmers into the shrimp lab to document how they hatch baby shrimp and then stock them in the tanks to grow. No antibiotics, no pesticides or waste runoff. Instead of constructing industrialized shrimp ponds, Sun Shrimp uses a landbased system, housing shrimps in closed containers, where temperature and water conditions are under strict control. The farm doesn’t just flush used water back out into the environment — risking pollutants and pathogens damaging surrounding ecosystems — but filters and reuses its water onsite.

“Every seafood product has a story to tell,” says Sarah Curry. She founded Sereia Films in 2016, combining her passion for storytelling and the ocean to catalyze change in the seafood industry.

Scientists across continents alarm: global fish supplies will decline as a result of climate change, ocean acidification, overfishing, and continual destruction of marine ecosystems. Urgent efforts need to be taken to make the seafood industry, at large, more sustainable. Sarah’s documentaries tell stories of changemaking innovators, like Sun Shrimp, who impact the health of what’s in our waters and on our plates. Before creating Sereia Films, Sarah studied marine biology at Louisiana State University and worked on commercial fishing boats.

“It was the first time I saw industrial seafood production and the bycatch that’s associated with it,” Sarah says. “I got to speak to all the fishermen, and that lifted back the curtain.”

Later, Sarah moved to Miami to work with Fish Navy Films to create documentaries on fish farms in 2011. After Fish Navy Films closed, she hopped on a plane to Portugal, known as one of the best fishing locations in Europe. Strolling Trilho dos Pescados (Fisherman’s

Trail) in the south of Portugal, she encountered a few fishermen about to embark on their daily journey. They kindly invited her to film on their boat, an offer she would never refuse.

On this adventure to collect Portugal’s delicacy, gooseneck barnacles, the fishermen taught Sarah a word that stuck: sereia, meaning “mermaid” in Portuguese.

WE TRY TO FOCUS ON BEING SOLUTIONORIENTED, TELLING POSITIVE STORIES, INSPIRING HOPE.Scan to watch Eating Out by Sereia Films

Sarah’s docuseries Eating Out: The Hunt for Sustainable Seafood tells of fisherwomen, scientists, NGO leaders, chefs, and fish farmers driving the sustainable seafood movement and explores the obstacles they face. From bycatch to the importance of healthy South Florida ecosystems, Sarah interviews people with unique perspectives to glean a more inclusive understanding of these complex issues.

We have to be hopeful. There are so many people working toward restoring the oceans. We could inspire other fishermen and aquaculture businesses to get on the right track to become sustainable.

In the most recent episode, Italian chef Mattia Danese demonstrates his method of reducing seafood waste: devising as many recipes needed to use an entire fish.

It’s impressive to see from just one fish, Mattia serves tartare with fresh garden tomatoes and parsley, fish fillet cubes with marinated cucumber and chile negro oil, fish liver glazed in honey, and bonito tiradito, from the belly, dressed with sesame oil.

For delicious and sustainable clams, Sarah brings you to Two Docks Shellfish, which operates an aquaculture farm just north of Sarasota, Florida. The company was founded by Aaron Welch Jr. and his son, Aaron Welch III. The Welchs raise seed clams that they plant in bags at the bottom of Terra Ceia Bay.

In order to feed the hungry clams with algae, the farmers use a system of pumps and passive upwelling to bring in unfiltered water directly from the bay; the water passes over the clams, and they siphon out the algae to eat. When the water leaves the nursery, it’s pumped back into the bay cleaner than when it entered,” explains Sarah. “Even at this stage, the farm is benefiting the local environment.

Since the United States imports approximately 80% of its seafood, most restaurants are likely serving seafood that isn’t fresh after transport. Two Docks Shellfish harvests fresh clams weekly and delivers their locally-sourced, sustainable seafood to area restaurants and retail outlets.

For consumers and business owners, being aware is the most important start to this journey. There are resources such as Seafood Watch, an organization by California’s Monterey Bay Aquarium that creates standards and recommendations for restaurants and other businesses purchasing sustainable seafood, or FishChoice, which offers guidance on which seafood products are safe to buy and from which suppliers.

Knowing how and where your seafood is harvested might be the key to protecting ourselves, our oceans, and ensuring a longterm seafood supply.

While some people and issues — whether by nature or by choice — are largely absent from online conversation, the organizations featured here haven’t forgotten them. These groups are doing the work that fosters something bigger: belonging.

by Kacie Brown

by Kacie Brown

From SNAP benefits to clothing drives, we hear a lot about initiatives to provide essential needs. But when was the last time you thought about diapers? Do you know how much they cost?

Parents earning the federal minimum wage can spend more than 8% of their income on diapers alone, and in Florida, diapers are not included in government assistance programs. One in three families in the United States doesn’t have enough diapers for their children. And when families can’t afford diapers — or have to make tough decisions between diapers and other basic needs like food — it doesn’t just have dire implications for babies’ health and hygiene. Parents suffer, too.

The Bank had humble beginnings. In 2012, Miami teen Jonah Schaechter focused his bar mitzvah community service project on collecting diapers for families in need, and with a local, posterpromoted school drive, he collected more than 10,000 diapers. Ten years, 6,200,000 diapers and 82,000 families later, Jonah’s dream serves six South Florida counties.

Gabriela states it’s their ability to mobilize a massive community of businesses, nonprofits and volunteers that enables them to disperse millions of diapers each year.

“Community and belonging, for us, just really mean the world because we wouldn’t be able to do what we do without the community, without having that sense of we can do this together,” Gabriela adds.

Gabriela Rojas

Miami Diaper Bank

MOST PEOPLE LIKE TO SAY IT’S JUST A DIAPER, BUT REALLY WE’RE ALLOWING THEM, EMPOWERING THEM, TO FEEL LIKE THE BEST PARENTS THAT THEY CAN BE.by

Sometimes, our basic physical needs overshadow our most intrinsic spiritual ones. When optometrist and breast cancer survivor Rosemary Carrera founded 305 Pink Pack, she discovered that the cancer patients she was hoping to help wouldn’t come to traditional support group sessions. So, they started gathering just to spend time together.

305 Pink Pack still provides basic services like rides to appointments, help with grocery shopping and mentorship through complicated treatments. They serve mostly Black and Latina women referred by social services because their circumstances or lack of resources may prevent them from completing treatment. But they also meet for mani-pedis and meals. They fundraise at drag brunches and open mic nights. It’s not the kind of support and visibility that someone who hasn’t experienced the disease might imagine needing.

head, someone would look at me with that pity face of oh, poor thing, and it was like, no, don’t look at me that way. I’m here, I’m alive, and I’m enjoying today.

In 2021, 305 Pink Pack partnered with Good Miami photographer Greg Clark, who took portraits of Pink Pack women and their families at a local park. Rosemary says in photos of people with cancer, you often see the illness, but in Greg’s photos, you see women and families enjoying a day at the park.

“It was such a wonderful sense of community and belonging because all those women knew why they were there. We’re obviously united by this one big thing called cancer, but cancer didn’t come up in the conversation at all,” she says.

When I was going through chemo, on the days that I felt well, I wanted to go out and conquer the world. But what was worse for me on those days, because I was bald and wouldn’t wear a wig or a scarf on my

NO, DON’T LOOK AT ME THAT WAY. I’M HERE, I’M ALIVE, AND I’M ENJOYING TODAY.by

For some, belonging comes through purpose. “I feel like I belong where I work, and am made to feel like I belong,” Jairo Arana says. But many on the autism spectrum, like Jairo, don’t have that opportunity.

He says many employers don’t realize that people with disabilities each have unique needs. Accessibility is about making sure wheelchair ramps and braille are available, but Jairo says these commonly-known accommodations aren’t the only ones that should be, well, common. He says accessibility also means creating quiet areas, providing captioning, using plain language and more; by considering the experiences of people of all abilities, the needs we often call “special” would no longer stand out.

Now, Jairo is making meaningful employment a reality for more people with disabilities. He works for University of Miami’s Center for Child Development, which provides leadership-focused training for anyone interested in advocating for greater accessibility. People with disabilities and their family members, students, and employers who have participated in their programs have led initiatives like “Inclusive After-School Activities” and “Improving Employment for People with Disabilities at the University of Miami.” Active advocates make accessibility the culture, not the exception.

Jairo says that self-advocacy is a huge component of the Center’s programs for people with disabilities, but that they also help people see beyond their own needs. And perhaps while showing others they belong, they’re finding space for themselves.

South Miami — the city’s first Black mayor — and one of the founding members of United Survivors of South Miami, or US, as Dr. Price calls it. This group of six women — three Black and three white — are working to heal the racial divide.

These women convened through mutual connections in the summer of 2020, shortly after George Floyd was killed by police in Minnesota. As South Miami residents whose professional backgrounds range from architecture to education, they had reached what Dr. Price described as a critical mass. These women knew the nation’s trajectory of racism could only lead to more pain, and not just for the victims.

The United Survivors were ready for change, and started their journey toward unity by interviewing longtime residents about their experiences with segregation in the city. Many of the women of US had lived in the area for decades but were surprised to learn about Jim Crow-era zoning laws that shut out Black businesses, discriminatory lending practices that kept property ownership out of reach, and yet another segregation wall in the American south that served as an architectural manifestation of racism.

“Belonging, for me, means that we’re all on the same team,” says Dr. Anna Price. She’s a former mayor of

US had unearthed a vibrant community that was senselessly repressed, and they wanted to celebrate it. We tend to think of change as a slow, grueling process, especially when government is involved. But these six women move fast. They pushed to have Juneteenth recognized as a paid holiday in the city of South Miami, and succeeded. Artist Gayle Alexander is transforming a rediscovered segregation wall into a mural of unity. Architect Alice Gray Read, a professor at Florida International University, is working on a virtual recreation of a street that, in the 1960s, was home to a thriving Black community: South Miami’s 59th Place. Visitors will be able to explore the street as it was before changes

“What I’ve learned is how to address the barriers that other people with disabilities experience, to call them out and find solutions,” he says.

IF YOU KEEP YOUR FOOT ON MY NECK, YOU CANNOT MOVE.

in zoning laws stifled South Miami’s Black business community — filled with stores, restaurants, hair salons, body shops.

Dr. Price has already restarted South Miami’s community relations board, which fosters mutual understanding among community members through educational programs and events, and the Marshall Williamson scholarship fund, named after South Miami’s first Black property owner. And these are just a few of the group’s ventures.

“We had no idea when we met that first time that all of these things would come forth,” Dr. Price says. And though the women of US come from vastly different backgrounds, she says they’ve achieved so much change because they’re united behind a common goal. United Survivors isn’t just showing people they belong in their communities or making space for people previously pushed out, they’re showing the community that they belong on the path to unity.

“We’re all on the same team, and the team is called life,” Dr. Price says.

THE CULTURE OF BELONGING IS TO CREATE SPACES THAT ARE MORE ACCESSIBLE THROUGH UNIVERSAL DESIGN.Photo courtesy of University of Miami

While plastic production is expected to double by 2040, we can, and must, change how we make and manage plastic pollution. From recycling machines to bamboo to-go boxes to hot pink composting buckets to plastic poetry — learn how Miami and its locals are dealing with waste more responsibly.

by Yulia Strokova

by Yulia Strokova

ext to Devia Juice Bar, found at Midtown Garden Center, you can always find the eye-catching pink bins with the attractive and instructive label Compost for Life. This cooperation between two innovative organizations began when siblings Diana and Juan Diego Devia decided to make their small business 100% plastic-free and divert their organic pulp from landfills. Devia Juice Bar serves their delicious blended superfoods in biodegradable cups and bowls that directly go to compost.

Food waste is one of the largest sources of methane emissions. Composting is an easy starting point to offset food waste emissions and make a positive impact on environmental and economic levels. When Francisco Torres began his pioneering journey to bring good, reliable, affordable composting options to Miami, commercial composting was not mainstream. Today, the company serves more than 40 businesses, including schools and hospitals, and offers their pickup residential service, starting at $19.99 per month. You can get a 5-gallon pink bucket to collect your food scraps at home and recycle it into high-quality soil to create a sustainable cycle.

"Composting food scraps is one the best things we can do for our environment. We are a community initiative, who have diverted more than 1 million pounds of food waste from landfills, and our mission is to leave this planet better than how we found it," adds Francisco.

Anastasia Mikhailochkina, the leader of Lean Orb, which specializes in producing compostable food service packaging, states that we all “have to shift to compostable materials and start composting so 50% of our waste will become healthy soil instead of landfill waste.”

Her company uses fibers from sugarcane, bamboo, banana leaf, wheat straw, and palm leaf to produce their cups, utensils, plates, and to-go boxes.

"Trash is pricey if you look at all the transportation and storage costs, so it makes sense to reuse our trash to make valuable biomass or fertilizers," Anastasia comments. "Compostable waste is a ‘black gold’ that society is not taking full advantage of."

To the question of whether Miami would be a zero-plastic city one day, Anastasia answers: “The aspiration is noble, but realistically speaking, that should not be our main focus today. We can put energy into responsible production and consumption of products, with an ultimate goal of renewable materials flowing continuously.”

Michelle Salas, known in Miami-Dade as the leader of Lady Green Recycling, has been dealing with local plastic trash since 2008. Lady Green Recycling services more than 1,000 locations from Homestead to North Miami, and

OUR MISSION IS TO LEAVE THIS PLANET BETTER THAN HOW WE FOUND IT.

what differentiates Michelle’s approach to recycling is the process customization her company designs for individual clients. Each client receives their own bins with QR codes on them. These QR codes allow Lady Green clients to access personalized videos which explain the recycling process so anyone ranging from children at schools or adults in offices knows how to use the recycling program.

Lady Green Recycling also owns their own plastic shredding and molding machinery, allowing them to shred plastic, make new products, and sell raw materials. Recycling is not performing at the scope and scale necessary to deliver the climate, economic, and waste

management benefits our planet needs. Fixing the system takes a strategy to mobilize collective action.

Plastic production is expected to double by 2040. Unless we change how we make and manage plastics, the problem of plastic pollution will keep growing.

To those who say that recycling is a myth, that it’s not economically & environmentally viable since there are thousands of different types of plastic which cannot be melted down together, and that it costs more to recycle than to produce new plastic, Michelle says we all need to upgrade our mindset:

“Some countries and states have successful recycling programs and prove that recycling systems work. So, we need to ask ourselves, why is it that in the majority of the states in the US, we see a lot of contamination, and why we're not recycling correctly versus these other states?”

even pay your reward foward by pledging your green compensation to a charitable cause of your choice right from your iPhone.

The successful on-campus program was launched in 2019. Today, Cycle Tech drives their municipal program in the City of Coral Gables in partnership with the Florida Beverage Association. In 2022, Cycle Tech also debuted at DRV PNK Stadium, making it easier for fans to recycle their empty beverage containers and win rewards in return. The process is simple: insert empty beverage containers at the machines, then scan a QR code to get a unique transaction ID. Once information is entered into the web app, users find out instantly if they are a winner and are given instructions for redeeming their prize.

According to the Eunomia & Ball Corporation report, the first comprehensive analysis providing an overview of the recycling rates among US states, the three states with the best overall recycling rates were Maine (72%), Vermont (62%), and Massachusetts (55%). Florida recycles only 21% of its waste.

Every state has different policies, different levels of access, and different infrastructure when it comes to recycling, making it exceptionally difficult to drive comprehensive and meaningful change. Still, effective recycling systems can lead to impressive environmental and economic impact and mitigate the packaging pollution crisis. Also noted in the report: recycling could support the reduction of more than 5% of global CO2, which is the equivalent of grounding all commercial flights globally and taking 65% of cars off the road for a year.

In Cycle Tech's case, recycling instantly rewards users for their sustainable behavior. Founded by University of Miami alums, the startup is expanding their network of Reverse Vending Machines to engage locals to make sustainable choices in a moment when people might not have enough opportunities to recycle their products. Whenever you bring an empty bottle (or empty beer can) for recycling, the system rewards you. You can

We're not saying that recycling is the only solution to the climate crisis, but it's certainly a necessary component. We just need to start asking the right questions and holding everybody accountable, not just consumers but the waste industry, bottle makers, and plastic manufacturers, to make effective recycling systems. Everybody has a role to play here.Photo courtesy of Cycle Tech

"Sports stadiums are an important part of American culture and represent a unique opportunity to educate and incentivize people to participate in the circular economy. The Cycle team is honored to be collaborating with Heineken USA and Inter Miami CF to launch this first-of-its-kind stadium recycling program," says Anwar Khan, co-founder of Cycle Tech.

Globally, we buy 54.9 million plastic bottles every hour. If all these empty bottles were collected into a pile, it would be higher than the Burj Khalifa in Dubai (which is the tallest building in the world). When plastic was invented in 1907, the world lacked the foresight to imagine how these highly malleable materials would become highly toxic for the environment; roughly 90% of drinking bottles are never recycled in the United States, so their life continues off our shores and in our oceans.

Scientists estimate 8 million tons of plastic enter the oceans every year, choking wildlife while they degrade for the next 500 years.

When Miami-based director and writer Franco Gonzalez created his animated trash monster, he didn't need to go far away. Franco collected trash from the beach and his sister's classroom. That one-minute video took the Sustainability in Action award, powered by Oolite Arts and the City of Miami Beach.

by Greg Clark,

Franco Gonzalez Film Director

by Greg Clark,

Franco Gonzalez Film Director

"I wanted audiences to have an emotional connection, not only to the monster, in the way it's portrayed, but also intellectually attached to the subject matter.

THERE IS SOMETHING REALLY BEAUTIFUL THAT HAPPENS WHEN YOUR CRAFT ALIGNS WITH YOUR PURPOSE.

Free Plastic, a local nonprofit driving community engagement, makes even trash poetic. They partnered with O, Miami to install a series of public artworks entitled Plastic Poetry. Each poem is written by a participating student in O, Miami's year-round education program and is displayed on the facade of their schools. Since 2020, the Plastic Poetry program has installed nine recycled poems across Miami and collected over 1,200 pounds of plastic trash.

Volunteer Cleanup connects local impact enthusiasts with cleanup events and estimates collected plastic in several hundred thousands of pounds. Through their website, you can find six to eight cleanups every week in MiamiDade County, led by a network of 80+ groups, including Clean This Beach Up, SENDIT4THESEA, Clean Miami Beach, and many others.

A tremendous amount of plastic is entering Biscayne Bay through stormwater systems, and the County and its 34 municipalities are cleaning the systems only once every five years — on average.

Dave Doebler is the co-founder of Volunteer Cleanup and also serves on the Miami-Dade County Biscayne Bay Watershed Advisory Board, among others. In 2022, he proposed new legislation to improve stormwater pollution control and increase maintenance — that proposal was passed by the commission unanimously.

Another big legislative success is a smoking ban on beaches and parks that went into effect on January 1, 2023.

"We realize enforcement will be difficult, but we are hoping the conversation gets smokers to realize that cigarette butts are made of non-biodegradable plastic that must be disposed of properly and that the planet (especially our beach) is not just a big ashtray," says cofounder of Volunteer Cleanup Dara Schoenwald.

"We spend much time identifying, mentoring, and investing in community leaders to help them succeed. When they succeed, they repeat. When they repeat, new people always have an opportunity to get engaged. It's not about us — it is about all of us."

by Anjuli Castano, Samantha Schalit

by Anjuli Castano, Samantha Schalit

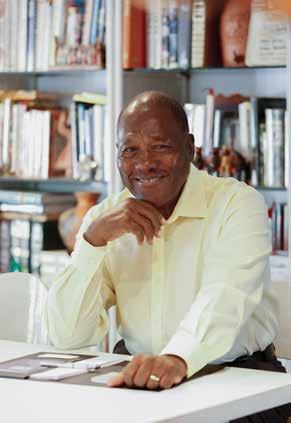

r. Marvin Dunn is a man who exemplifies the phrase knowledge is power. As a historian of the Black experience in South Florida and as a doctorate of psychology, he unfolds the why and how of race relations with an authority on historical accuracies and the emotional consequences. His ethos is built on academics and personal experience that pronounces a Black South Florida which is resilient and progressive yet still processing intergenerational trauma and its effects present today. Like a true stoic he speaks with impartial sternness, calling out the lack of historical awareness about who South Florida is. When asked what impact knowing Black history has on our youth, he responded anti-humorously, reiterating the question as if to confirm.

“What impact?” he responded. “Well, none that I can say because they don’t know it.” The weight of this assertion falls on us all who do not know the Black men and women whose hands constructed this city of limestone and coral. Or how they shaped its emerging culture with rich Caribbean and African descendance; their influence, more than their presence, cut through mosquito clouds and thick marshes to transform the Miami we’ve come to know.

This reality demands a different mode of questioning. The real question is: What would be? With a slight smile, Dr. Dunn said, “Good question. They would be proud.”

Florida is a unique place in the development of Black history in the South. Under Spanish colonization, enslaved men and women sought freedom that allegiance to the Spanish crown and Catholicism granted in Florida. The wild vegetation and wetlands became a refuge, a place where once-enslaved people could work for a wage and create community in towns like St. Augustine. And through the construction of emerging cities, Black voters were imperative in the numbers required for incorporation. In the case of Miami, 162 of the nearly 400 men who incorporated the Magic City were men of color. Suffrage for the Black man did not mean an end to the battle for equality and justice, but the spirit of Black resistance has always been strong in South Florida; it’s present in landmarks like the historic Virginia Key Beach and Overtown, originally called Colored Town.

Further north of the industrial and commercial boom in South Florida, a strong figure of Black progression lived. The town of Rosewood, a few miles inland from the Gulf Coast, was a fruitful Black neighborhood that flourished in the lumber industry and exhibited a unique economic and cultural freedom for the time. Those who remember it tell of the large white houses and tall cedar trees which enveloped a lively and interconnected community. Dr. Dunn interviewed Rosewood survivor Robie Mortin, who said, “Everybody had something going. People owned acres of land, not just lots, and the houses were mostly two-story houses. The white folks really wanted those houses.” This richness lasted from the early 1900s to 1923 when the town and its people were massacred by a group of white men from a neighboring town.

Throughout history, segregation, redlining, and gentrification have all been tools used to erase examples of Black progression. “Rosewood now has no Black people, it is completely gentrified,” Dr. Dunn said. He purchased five acres of Rosewood, preserving a piece of the old Seaboard Air Line Railway.

The displacement of Black people from the area does not eradicate Rosewood's Black history.

“Unless I hold on to those five acres, any trace of the railroad will be gone.”

Dr. Dunn is transforming the land into a historic park, placing benches where the railroad ran through and leaving the rest of the land as-is. Commemorating the lingering presence of this railroad preserves and punctuates a period of both prosperity and great injustice in Florida Black history.

The Rosewood Massacre is just one example of his extensive wealth of historical knowledge exhibited on his website, a digital museum accessible to all. In the narratives and discussions, researched and written by Dr. Dunn, we find a Florida history otherwise obscured and a call to change that. The histories forgotten are given new life with topics ranging from Civil Rights to Seminole and Black community relations, many of them still holding relevance today.

At his core, Dr. Dunn is an educator and a champion of integrity in honest portrayals of historical events. He says he studied psychology in university to better understand racism and its roots and motivations. Through his schooling he has come to learn a new side to his struggle.

“I knew about the struggle for power, for land, for political positions. But what I learned was that there are dramatic strains that cut through all of these, mostly based upon fear. And that is a very dangerous motivator,” he said. The foundation of our divisions is fear of each other; when we are alienated from other people’s histories, we are estranged from others’ humanity and find justification to fear them.

Dunn was able to hold onto his history because of his proximity to it. “I knew Jim Crow,” he writes. “I grew up in Florida under his dark, suffocating wings. I knew him intimately, as did every Black person I knew growing up in Deland and Miami in the 1940s and 50s.”

Since September 2020, more than 25 states (including Florida) have introduced legislation to restrict what can be taught about US history in schools and universities, taking aim at critical race theory. This has a chilling effect on conversations about race relations in the United States. Without these histories, we face a divided and unjust future void of the stories that contextualize the pain points experienced today by our diverse populations in schools, workplaces, and social systems.

“Through learning Black history, non-Black people learn about the challenges that Black people have had in this city and are more open to developing reparations.” This effort is for all to consider, as Dr. Dunn continues, “We who are Black should learn more about Appalachian or Cuban history so we better know what we’ve all given to this community. It makes us better citizens.”

We cannot forget the great lengths those before us went to demand the civil liberties we know to be natural in democratic society. We must not look away at the threats to these institutions which bubble up in times of tension. Fear of your neighbor will hold progress hostage. Working together to build respect and tolerance will unleash it.

IMPORTANTThe only house in Rosewood, Photography by Chuck Fadely, 1999, Courtesy of the Miami Herald Commemorating the 100-year anniversary of the Rosewood Massacre, the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum presents An Elegy to Rosewood. On display through April 16, 2023.

Lingering social stigmas and scarcity of services still bar access to mental health care. Yet there are those who challenge that notion and find unique pathways to nurture those having the hardest times. So, when and how must we change our attitude, actions, and approaches to others’ — and our own — mental health?

by Kacie Brown

by Kacie Brown

Asuccessful dog trainer and restaurant manager in South Miami, a young woman who chose the same name as her mentor’s after transitioning, a patient in distress who smiled and sang in community with others: these are just a few examples of people whose lives have changed, in big ways or small, because someone took the time to help them feel valued — and because they had access to mental health care.

In 2022, the World Health Organization reported a 25% global increase in anxiety and depression due to COVID-19. But the majority of these people will go untreated. In the United States, many people still lack basic physical health care. And access to mental health care lags behind despite the rise in mental distress.

The United States has also been facing its difficult past — and present. Conversations about the collective trauma of oppressed groups, grim effects of inaccessibility, and sorrows of systemic injustice aren’t happening at the margins of our societies anymore. They’re at the center of public discourse. As people are realizing the mental toll these stressors take, many organizations are using unique pathways to support them.

We talked with some of these changemaking organizations to find out how they nurture mental health in those having the hardest times.

Nurturing mental health, in part, means meeting people where they are on the journey of accepting and identifying their mental struggles, Peter O’Connell, CEO of the Center for Independent Living of South Florida (CILSF), says. In the community of people with disabilities, mental health issues are common. In fact, the Pan American Health Organization says they’re the world’s leading cause of disability. But the signs of mental illnesses are often invisible and the effects underestimated, and for people with disabilities, they’re yet another diagnosis, another stigmatized challenge.

As CILSF serves clients often represented more by numbers on a spreadsheet than their own voices, much of the organization’s work promotes what Peter describes as self-advocacy. They partner with initiatives like Catalyst Miami’s Enable Project to explore intersectionality and encourage civic engagement. And it’s not about pushing clients to become full-time advocates, Peter says. Sometimes the work is simply in discovering how to tell one’s own story. “It’s important that we can relate our experiences to someone who doesn’t share them,” Peter says. “And there is a much greater likelihood of achieving success if you bring a solution and a willingness to engage.”

FLITE Center (Fort Lauderdale Independence, Training & Education) serves a particular community of young people most disproportionately affected by mental health issues: LGBTQ+ teens transitioning out of foster care. This isn’t FLITE's sole focus, but their desire to create a safe, comfortable space for everyone — and adapt if they’re not achieving that — sets them apart.

Executive Director Christine Frederick says this group of young people faces the kinds of problems, like homelessness, that the rest of the population transitioning out of foster care does, but may also struggle with the trauma of being rejected for their identity and face a greater risk of exploitation and trafficking. Some of their emotional needs are actually very simple.

Working with this population really taught me a lot about how I wanted to be as a parent, the support that I wanted to give my children. I always wanted to make them feel they were loved beyond measure and that nothing would rattle that. And I think that’s so important because that’s a lot of what young people are missing, just that unconditional support.

When faced with a challenge, we often search for a tool to make overcoming it a little bit easier. Mind&Melody’s tool of choice is music. “I like to think of music kind of like a type of magic that we have as humans,” Program Director Eric Guitian says. The organization serves children and adults with neurological impairments through music groups and lessons that provide rich social interaction and cognitive, physical, and creative stimulation. And they see results.

He described working with one patient, a new resident, at an assisted living community where Mind&Melody

Sometimes we work with people who can’t talk, but just through the songs, we start to learn about them.

holds classes. She wandered around the room at first, agitated and upset. But as the group sang, Eric noticed a small smile on her face. She tapped her hands, shook a maraca, and finally joined in the singing. Mind&Melody can’t cure or fix the disorders their musicians face, but they can bring smiles and connection to people who we often forget still need them.