by

I still remember the day I walked up to Grace Garlesky’s house–our chapter’s cofounder–for my first shoot during Issue 02. I was eighteen with fiery red hair, a pounding heart, and completely intimidated to step into a space full of creators I admired. On the door hung a handmade paper sign, written in Sharpie:

“STRIKE. Come in!”

That was four and a half years ago. I could never have imagined then how much I would grow within this space, or how many rooms of collaboration and creativity I would walk through since that day.

This semester, I stepped into the role of Editor-in-Chief for the first and last time. Like Grace once did for me, I opened my house and my heart to our team-–filling them with laughter, late-night meetings, and streamlining photoshoots turned into cherished memories. Over the years, Strike St. Augustine has grown in number, in scope, and in the reach of its voice. Yet at its core, Strike remains a close-knit, collaborative collective built on trust, passion, and the belief that creativity flourishes best when shared.

The Body as an Archive is a testament to my time with Strike—a reflection of every season, every struggle, and every person who has shaped this space. It stands in honor of those who came before me, who built the foundation I now stand on. It is a meditation on memory: how the body becomes an archive, how experience lingers in gesture and gaze, how creation of art itself is a record of where we have been.

To my incredible team–thank you. For your artistry, your dedication, and your trust. You are the heartbeat of this home, and it has been the greatest honor to create alongside you. We come from different places, but we chose to walk through this same door. As I prepare to step back, I will leave it ajar for those who follow–to enter, to reshape these rooms, and to keep the lights on.

The door is always open.

Daisy Pflaum Editor-in-Chief, Strike St. Augustine

Throughout my time with Strike Magazine St. Augustine, I have had the honor of working alongside many incredible artists. Evita Carrasco, our previous Creative Director, inspired me to approach design with intention, and I would not be in this role today without her.

Our process is constantly shifting—concepts evolve, designs adapt, and styling takes new shape through collective input. That collaboration not only strengthens the final product, but also creates a community where genuine friendships and growth develop naturally.

This version of graphic design, the one I’ve learned, explored, and refined through Strike, has become my favorite. Strike gave me the space to experiment, to learn from those who came before me, and to discover my own voice. As Creative Director and Graphic Design Director, I have been able to pass on what I’ve learned to other members who are just beginning their own creative journeys. Teaching others the skills and lessons that were once shared with me has been an incredible experience.

I want to extend my gratitude to our entire Issue 10 staff. Your dedication and creativity are visible in every detail of this issue.

Thank you for holding this issue in your hands, for supporting our evolution, and for believing in what Strike stands for.

With gratitude,

Sophia Johnston Creative Director, Strike St. Augustine

WRITING DIRECTOR

Jessica Giraldo

EIC ASSISTANT

Olivia Pagliuca

WRITING ASSISTANT

Kaya O’Rourke

DIRECTOR

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

CREATIVE ASSISTANT

by Max Gibbs

We stand poised in an exhibition so vast it devours thought itself. The brain’s hollow atrium yawns above us, reverberating with the soft static of memory. Beneath our feet, the soul’s chamber throbs—a slow, seismic pulse syncing with our own as the architecture exhales. Corridors split and spiral like arteries too narrow to follow. The air hums with a low vibration, trapped between ribbed walls that press against our chests. Every passage multiplies, folding into a labyrinth of living flesh.

In the adjoining room stands a single statue—impossibly tall, painfully alive, carved in excruciating detail. He kneels, a sword lodged deep in his chest, the wound still mid-beat. Calloused hands rest at his sides. His face is serene. His eyes are closed in surrender.

This is not a metaphor. This is biology and biography.

The body is an archive, a living record of every sensation—joy, grief, desire, terror—etched into tissue, threaded through breath, blood, and bone.

Trauma does not linger only in memory; it anchors itself in posture, in tension, in the shallowness of a breath never fully released.

The lungs ache with fear caught mid-breath, the skin bristles with touch—too soft, too hard, too soon. In a crowded room, a single glance can redraw the map of a lifetime. The heart takes note, quietly setting out extra chairs at the table for ghosts that still pass through. Waiting becomes ritual; grief seeps into the spine, bending the body into its familiar curve of exhaustion. Every sound—a door closing, a footstep on the porch— makes the pulse quicken. Maybe this time, a traveler has stopped to stay, to take a bite, to remind the nerves what connection feels like.

We move through the world as walking galleries, each scar a small plaque. What we call healing is often just curation—the careful rearranging of what still hurts until it appears bearable. Yet inside us, the rooms remain dimly lit and history hangs from the walls.

How much of us is still alive and how much is only on display?

by Daisy Pflaum

Dedicated to my Grandma Pat

Once I walked through the open gates of a cemetery with overgrown memories and tokens of offering sprawled throughout the landscape.

Stopping at each gravesite, the freshly turned soil reminded me of how I would bury things in adolescence: taking doll accessories, wrapping them in tissue with a handwritten note and gently placing them into the ground. The earth lived under my fingernails and stepping stones bruised my knees, as if my body was a small sacrifice for a sacred offering.

I paused in front of the mausoleum—how could I not? Grand, intricate, holy. My eyes follow the marble’s veined patterns to its delicate engravings. When the light hits it just right, it glows. It feels familiar, though I know I’ve never seen it. It represents death, but also an enduring love for whoever rests within.

I took my time to read the words carved into every headstone, calculating how old each person would have been when they passed. In a century or two, another little girl just like me will live in my home and dig everything up, my gift to her. Maybe her imagination was wild too; some fairies left their belongings behind, or a family of crows stashed their goods there.

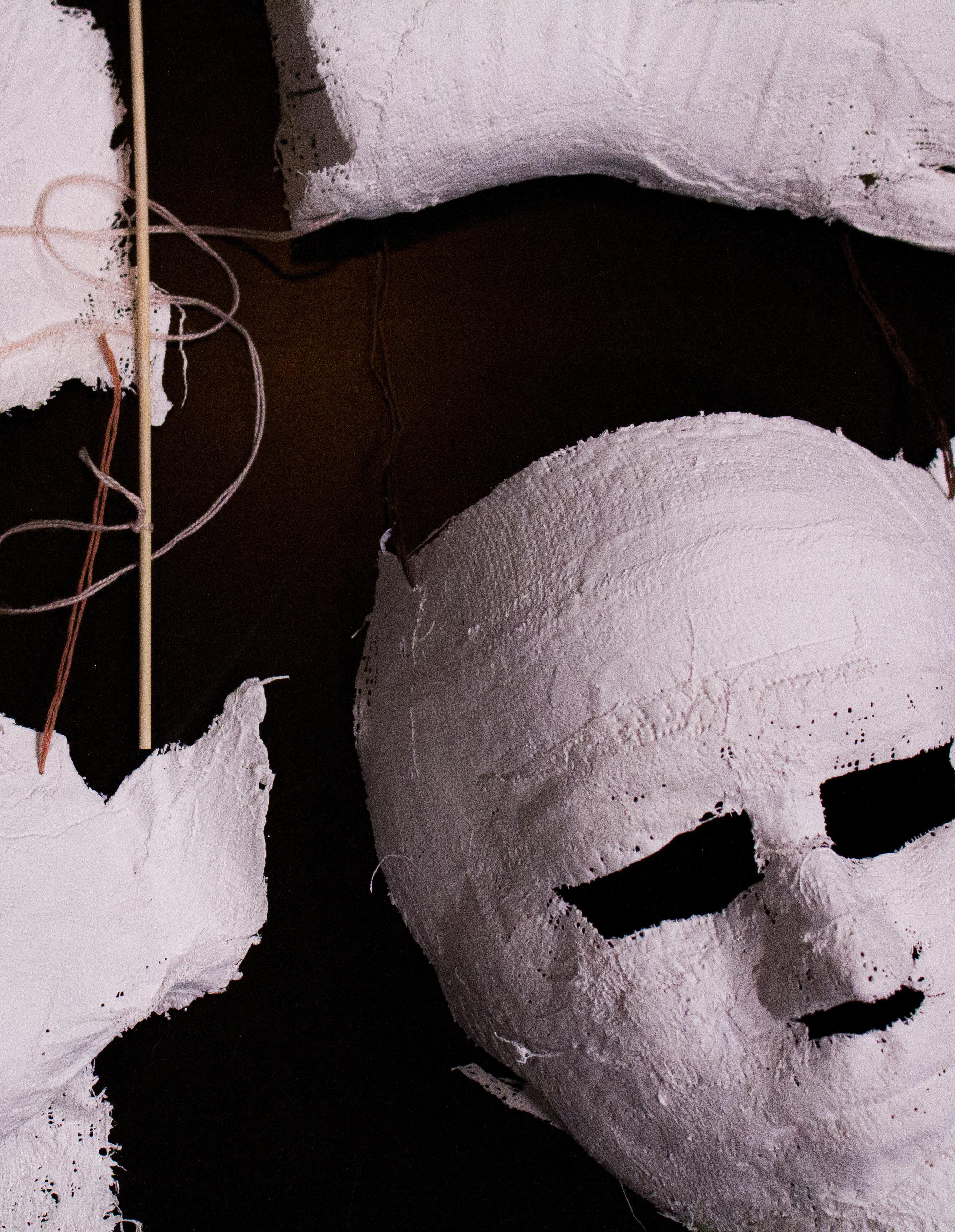

Even then, I innately understood that imagination, playfulness, and creativity connected human beings, withstanding generations. I am nineteen years old now and I no longer bury things in mud. I express imagination in other forms, making something out of nothing: rearranging scraps of paper, dousing fabric in plaster and swiping colors on canvas.

I was raised under Creationism, which teaches that divine hands formed the universe and everything living. Influenced by its words, I find creation to be deeply personal, religious and intimate; being an artist is the closest you can get to playing God. Creation has always been a constant in my life–not just in artistic ways, but theological ways. Whatever God felt seeing Adam take shape from the Earth’s dust must feel similar to pressing clay into form, coaxing limbs and features into existence–a body formed under my own. Jesus himself felt a sense of pride when his community gathered around a table he built himself.

What else could be more heavenly than earthly beings attempting to play their hand in creation? To make something from nothing requires trust in what you can’t yet see. And on the days when I can’t recall the last time I opened a holy text or called to the Creator, the paint on my legs or scraps glued together worship louder than a sinner on a Sunday pleading for heaven. Before this issue of Strike,

by Daisy Pflaum

death and I were strangers—a rare privilege. Our photoshoot concept, Spine, brought toward the question of how we carry the weight of what we survive, particularly grief.

In some sort of divinely morbid timing, my grandma passed away.

For as long as I can remember, my grandmother poured her time and energy into creating. She saw the unconventional and turned it into something that told a story or made you feel. Her vision stretched beyond any single medium. It wasn’t the materials that made our time special— it was having her beside me. When I sculpt, I sometimes catch glimpses of her hands in mine: the angle of her wrist, the precision of her fingers, the gentleness of a creator’s touch.

At her resting place, I didn’t bring any flowers but I couldn’t leave without offering something. When I was given the opportunity to sculpt pieces for this issue, I instantly knew they belonged to my grandma. Before she passed, I told her I would never be able to do any of this without her influence. I am her grandchild—maybe not by blood, but by creativity. A legacy kept alive through artistry, existing as a living archive of her imagination.

On my walk home, I admired the changing trees, their colors complementing each other in ways

Once I walked through the open gates of a cemetery with overgrown memories and tokens of offering sprawled throughout the landscape.

Stopping at each gravesite, the freshly turned soil reminded me of how I would bury things in adolescence: taking doll accessories, wrapping them in tissue with a handwritten note and gently placing them into the gr earth lived under my fingernails and stepping stones bruised my knees, as if

I paused in front of the mausoleum—how could I not? Grand, intricate, holy. My eyes follow the marble’s veined patterns to its delicate engravings. When the light hits it just right, it glows. It feels familiar, though I know I’ve nev er seen it. It represents death, but also an enduring love for whoever rests within.

I took my time to read the words carved into every headstone, calculating how old each person would have been

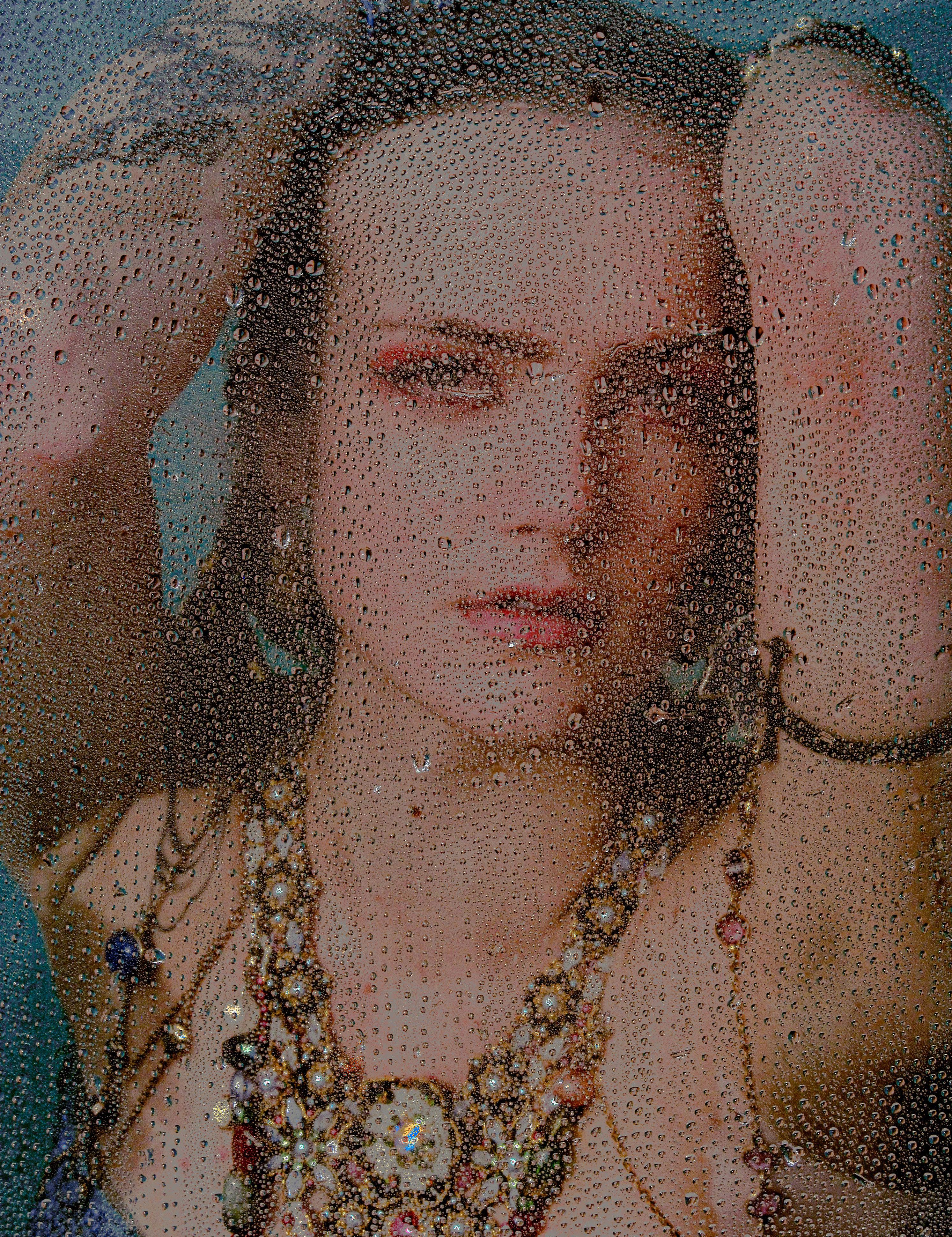

You get out of the shower: where does your immediate gaze go? You are probably going to say the mirror. One of the first things you do is wipe off the thick layer of steam coating the glass, clouding its reflective nature. It might take a second for a clear image to appear, but once it does the assessment begins.

Did your razor catch every hair you intended it to? Is that extra slice of pizza from lunch today showing? If it is, maybe you’ll have a smaller dinner. Did your boobs get bigger, your butt get smaller?

When you finish performing your physical evaluation, you move to your room. Looking at your closet you ask yourself which articles of clothing will accentuate your assets whilst hiding your insecurities. You get dressed and take another look in the mirror – its reflection is a pretest before you enter the public eye for a true examination. You want to make sure that you study enough so that there is no chance you fail it.

Now that you are bathed and dressed, you head back into the bathroom. You brush your hair, apply some moisturizer, maybe even add a little makeup. Once you get in your car you check your face in the rearview mirror one last time just in case your previous judgment failed you.

We fixate on the things that we can control in an effort to ignore those that we cannot. The truth is, we will always know imperfections are there, but the hope is that others will not. You can try to say that you are doing this for yourself, but the reality is that this is not in the name of ‘self care.’ What you are doing is in spite of yourself; it is to please everyone else at the expense of your sanity.

When I think about how much time I spend worrying about other people’s perception of me, I realize that much of what

I do is for their approval. How much of who I am exists because of me, and how much because of what I think others will like? My existence feels like a museum, and I am the curator.

Every time I go in public the exhibition opens for ticket holders to judge. The reviews always come later, but at that point I have already imagined them in print. I anticipate their inner monologue before it reaches group discussion. They probably notice my crooked teeth, think I am acting weird, that I talk too much. The anxiety makes me overcorrect, confirming their suspicions. Earning their approval has become a lifelong game I never remember choosing to play.

But what is the game’s collateral? How many conversations am I checked out of because internally my mind is obsessing over a check list? How many times do I repeat questions or forget things someone has told me because I am never really listening? I am too busy managing the exhibition.

As any good curator does I study other successful exhibitions, pulling inspiration from them as I conceive my own. I find myself looking for clothes that others were praised in, blowing out my hair because that is what the ‘it’ girls do, and trying to mimic any quality the general public has deemed desirable.

Eventually I become this mosaic of everyone else’s desires, and I find myself questioning if there are any parts of myself that are truly ‘me.’ When did I begin measuring myself against public opinion, and when did that measure transform from a consideration to being the epicenter of my entire existence?

The thing about being a curator is that the museum is your life’s work, not just a place you visit for a few hours when you are in town. You pour more energy into the exhibition than anyone else, but you are the only one who cannot enjoy it. You are working the event so that everyone else can bask in its beauty, but that means you never get to do the same. Then people tell you that this is just what it means to be a woman.

But when the museum is closed and the curator is alone she falls apart. When nobody is visiting the exhibition its purpose loses clarity. Conviction blurs and you begin to ask yourself if you have any authenticity. The mind races to find answers that will take a lifetime to ascertain.

That is until the next day comes. You sweep up the mess and rearrange anything out of place before you reopen. Everything has to look perfect – even if it isn’t – because you are on display.

Strolling through museums, I feel studied—not just by the marble women lining the halls, but by the centuries of eyes that have defined beauty through them. Their forms are precise and measured: the subtle rotation of the hips, the calculated curvature of the spine; every muscle rendered in tension, every gesture controlled. I find the statues anatomically reverent yet emotionally distant—perfect but lifeless. Their figures are mere vessels of symmetry rather than spirit, stripped of their humanity.

We use clinical terms to describe them: proportion, contour, equilibrium. The female form became an idealized system when the “divine ratio” that governed classical sculptures shifted from aesthetic principle to that of a mathematical equation. It is studied, dissected, immortalized. Yet the living body, with its irregularities and impulses, defies such containment. The heart does not beat to maintain visual balance; it contracts and expands because it must—because life demands rhythm over perfection.

Younger me believed those marble women represented reverence, proof that femininity had once been sacred. The older, more actualized version of me understands that their sanctity was conditional. They were not celebrated for who they were or what they contributed to their time. Their postmortem admiration was stillness. Their beauty depended on silence, on the absence of blood and breath. What was once worship was really just control disguised as admiration.

Our world mirrors that contradiction. We idolize the feminine form in museums but critique it in motion. The softness we glorify in stone becomes a liability in flesh. Venus’s full hips are divine; a living woman’s are “unprofessional.”

Women on the street model their frizzy hair, torn-apart cuticles, and stretch marks painted onto their skin, while statues showcase nothing less than perfection. Every scar, divot, and roll is seen in its truest and most personal form, yet not allowed within the confines of molded marble. The body that was once sculpted to be adored is now dissected by algorithms and comment sections—a cultural paradox that seeps into the psyche.

The paradox evolves into psychological conditioning. Accustomed, the brain splits the body into two selves: one that our eyes see and one that our souls feel. We cultivate the visible body with filters, good posture, and discipline, while the internal body—the beating, breathing, living organism—becomes something private, often shameful. Cultural ideals translate into biological tension.

Still, I am drawn back to those statues—not to emulate them, but to reclaim what they lost. Standing before them, I feel my pulse echoing through the museum’s quiet, a reminder that I am both study and subject, both anatomy and soul. My body metabolizes, perspires, adapts; it defies stillness by its very nature. Perhaps that is the truest form of beauty, not the flawless preservation of form etched in marble and stone, but the persistence of life inside.

My journal holds the deepest, darkest parts of my mind, yet never fails to receive the words that spill out of my mind embalmed. I don’t know what I would do without it. There is no world in which I am not writing within it, communicating each inner monologue that conjures in my brain everyday.

You–a mere leather bound book–have archived my growth from past tragedies I never envisioned overcoming, listening to every individual word sprawled across your body.

What horrible things You must think of me.

Yet, You must love to see the version of who I am today; I pay respect for creating the person who sits and writes this piece dedicated to You.

At times I wonder whether you’ve had enough, yet You are eager to allow me to bleed out words, dampening each one of your pages.The binds that keep You together–just barely intact–are held together for my sake. As I skim through the collection of thoughts I have conjured over time, I cannot help but fall to my knees in awe of the record preserved despite the swiftness of time–each flip of the page is a newborn season-constantly evolving.

These words are everything I am, and will forever be a part of me.

April 8, 2021: My mind is a dark place I am appalled to live in.

April 15, 2022: My body is nothing more than a vessel for a broken soul.

March 3, 2022: Years spent, drained out of my emotions, I’m thankful to finally feel human.

November 25, 2022: I am nothing without my past.

February 9 2023: I am learning to love both my masculine and feminine and side, I am so uneasy.

I don’t know what this means.

February 16, 2023: I can’t understand this mind of mine.

February 19, 2023: Reality is more of a nightmare than my own dreams.

June 24, 2023: You are pathetic, wasting space for others who want to live.

You will forever remember who I was and I will forever look back, appreciating You and the space in which I was granted relief.

October 19, 2024: Growing pains hurt so bad, but are so important in molding us as humans

January 16, 2024: I feel like clay being molded in someone’s hands, changing shape constantly.

by

At eight years old, I knelt beside a twin bed dressed in faded Cinderella sheets, the kind that smelled faintly of dust and detergent, a wooden cross hung above my pillow. In the dining room—where we ate beneath the haze of a yellow bulb—The Last Supper watched over a family that could not make it through a single meal without someone muttering, “Can I be excused?”

I pressed my forehead into my thumbs until bone met the bridge of my nose—because if I did not, if I let the words slip, my family's souls might be crucified before dawn. I, the small and quivering child, would have failed the reaping. I learned the choreography of salvation: bow, recite, repent, repeat.

Now I lay me down to sleep, I pray the Lord my soul to keep. If I should die before I wake, I pray the Lord my soul to take. God bless my family. God bless my friends. God bless everybody who needs it. Amen.

What a gruesome thing for an eight-year-old to pray; to be saved is to internalize mortality before bedtime.

The Just Judge has appeared to me twice—both times through the mouths of the almost-dead. I used to nod and think, yeah, right, until the day He fell from the wall, the nail in plaster giving way. For a split second, I swore He was alive. Yet, this wooden figure, the body of Christ, could have simply been a physics problem: nail, plaster, and gravity. The collapse of object into something almost bodily alive lingered with me; a meditation on what separates devotion from examination, the relic from the specimen, and holiness from the body itself.

Eleanor Crook’s Santa Medicina embodies this tension between science and faith with a figure both surgeon and saint. The stethoscope becomes a rosary, and her hands, casted from the shape of cardiac surgeon Francis Wells, hold a scalpel and scissors: instruments of healing and symbols of death’s fate. Beneath her skirt rests a fragile form, body and soul sustained by both medicine and belief. Crook’s imagined patron saint of medicine invites viewers to consider what it means to die well—to reconcile the sacred and the scientific in our pursuit of a “good death.”

The most extravagant act of purity: to protect the body from the very decay that makes it human, to preserve the corpse from returning properly to the earth, sealing itself inside its own coffin. In the chamber, the embalmed corpse begins to decompose in slow motion, deprived of air. These polymer corpses carry the same impulse that once hung saints’ bones in cathedrals or sealed mummies in Egyptian sarcophagi: our hunger for worship of endurance itself. It seems humans have confused preservation with grace, constructing a heaven that smells faintly of formaldehyde.

When an insect enters our home, we escort it outside in a small ritual of mercy. Yet when a human dies, we encase them in lacquered boxes, display their corpse, burn their remains, seal them beneath manicured plots of earth, and tell them it is either Heaven or Hell. Is it not more ethereal to decay naturally—to feed the peonies, the mold, and the maggots birthed from within our rotten flesh and be absorbed into the very earth that once birthed us? It is called respect, but it is really just control keeping the body from doing what it was designed to do—decompose.

I have spent my life being told that obedience ensures admittance to heaven, that salvation is a matter of displayed performance. But when He fell from the wall before I even touched the lover beside me, I wondered: was this a warning? Is this sexuality of mine enough to damn me to hell for eternity—so much so that a relic of Jesus had to fall from the nail in the plaster to tell me Himself? I thought the point of reciting prayer gave voice to the hope that, because I was baptized, I would rise from the sleep of death to life in Christ.

We tell ourselves this is dignity, that the lacquered box keeps us pure and safe, when in truth it interrupts the cycle that once made us holy—the exchange between flesh and ground. I do not seek to revoke Genesis 1:1, but I question how we came to interpret its divine hierarchy, and wonder if what we call dignity has become little more than denial. Our prayers, our rituals, our obsession with preservation—they are all attempts to control what cannot be, to resist the inevitability of decay. The Eucharist turns bread into body; rot turns body into bread for the world. And yet, life reclaims what we try to sanctify: what we enshrine in boxes and polish with ceremony ultimately returns to our collective earth.

by

Jessica Giraldo

Encased in the brush, a pair of lungs rest—darkened, fragile, suspended in smog. The pleura clings to them like a thin veil, a translucent membrane cradling what remains of breath. It is both barrier and sanctuary, a thin film of endurance that has borne witness to tenderness and violation alike. Here, survival begins; a choreography of expansion and retreat, of breath both taken and withheld. Each residue of smog becomes a memory; each tightening of the airway, a rehearsal for threat.

Then, they enter the room. The inhale falters. The lungs seize, startled by familiarity. Panic flares beneath the sternum as the ribs tighten like shutters in a storm. The body remembers before the mind can speak. You feel the old pulse of safety—the nest, the old walls, the ache of wanting to belong to what once nearly drowned you.

Home, the word hums against the trachea.

Stay, and the lungs hold their breath, trapped within their own defense. Go, and you risk tearing the pleura—exposing yourself to the raw air of pain, of possibility.

As panic stirs beneath the sternum, you ask: am I evolving, or merely surviving long enough?

Growth demands damage; healing asks for rupture. The lungs ache for motion, even as the chest trembles beneath its own expansion. This tension extends beyond the body: it lives in relationships that both soothe and suffocate, in families whose love bruises as it protects, in dependencies that promise relief while quietly stealing air. We confuse enclosure with safety, stillness with peace.

Even the smallest inhale is rebellion. Life, always, is a negotiation between survival and freedom, between the comfort of enclosure and the ache of breath. Every act of staying carries a cost, and every act of leaving requires exposure. Growth is never gentle. Liberation, always, asks for air.

Photo by Eryn Wagner

Z.K. Domingo

“The sheep that are My own hear My voice and listen to Me; I know them, and they follow Me. And I give them eternal life, and they will never, ever, by any means, perish; and no one will ever snatch them out of My hand.” – John 10:27-28.

Sweet, innocent lamb–fragile, crystallized, protected, sore from the hacksaw.

Hacksaw or hand?

Dually equipped with conservatorship, what happens to the pasture of the lambs when the shepherd becomes polluted?

The hacksaw drags, against the surface, in between pauses–puncture. They saw the tissue to nothingness.

Let it out, little lamb–

How dare the pathetic little lamb!

Nightmares of mutton, daydreams of smoke.

Your presence is my priority, necessary for survival.

Your static bleats toll in my ears; repetition becomes routine.

Drown, drown, drown it out–I maneuver the staff around the bottleneck of each lung. Keep the smoke in, resist not. Pasture polluted.

I bend at your command, willingly–to be so vulnerable at your hand, is the highest blessing of all.

A haven once sacred deteriorates. dependency grows stronger, morals grow weaker. I am left to rot–to choke on recycled oxygen, to feed off of tissue soaked in flammable fluid; but I plead for more.

Deserving of gentleness, but never receiving. Your shushing soothes, yet sickens me, submitting to your authority to be made a fool.

Forgive me, shepherd, I cannot stop returning to you. I choke back my tears, choke on the ashes in my airways.

Once untainted ivory wool–lose sight of me now, indistinguishable through billowing clouds. Tears push to the surface, camouflaged by self-servience.

What have I done to you? What is left of you? Return to the herd soon.

The shepherd returns home, unharmed.

The shepherd ignites the flame, burning the throat.

The shepherd mourns loudly, wails reverberating.

A shepherd without a lamb to herd?

No purpose at all.

Herd polluted–

The shepherd assumes the position as pollutant, all-consuming.

The lamb is lost–collapsed.

by Eryn

Lydia Corbin

Nourishment, adornment, love; how can love feel both so fulfilling in one moment, yet devastating in another? As a society, we are so focused on finding our person—someone you would love until your last dying breath as your lungs give out. The hand-crafted other half of you that makes your heart beat. When you find that one, everything changes. You go on that first date with them, and your heart is beating out of your chest, butterflies swarm your stomach, and an anxious excitement rises in your lungs. Love begins in the body before it ever reaches the mind. The pleura–that delicate lining around the lungs–expands and contracts with each shallow breath of anticipation. Desire feels cellularat first. The ribs act as a birdscage for the delicate nest inside.You create the nest, nourish it—until you open that cage for the right person. When you let that nest flourish, you let love in and your heart opens wide. Months—or even years—go by, and suddenly a new ache begins. Your bird’s nest is overgrown, and something has shifted. The person you once thought was your forever can no longer nourish your desires. The weight inside expands, pressing against your ribs and lungs, making every breath a reminder of love lost. The pleura exists to protect what keeps us alive. Love functions much the same way: when it’s healthy, it cushions us, but when it ruptures, every breath becomes a wound. One wrong move from the wrong lover leaves your nest broken and damaged, your birdcage rusty and shut. Maybe the relationship ended on their terms, leaving you blindsided. The body

goes into fight or flight—that anxious, fluttery feeling returns, but this time for the wrong reasons. Your soul aches deeply for what you once had, leaving you crushed and in despair. You are suffering from a case of a broken heart. Broken heart syndrome (Takotsubo cardiomyopathy) is a temporary condition where the heart muscle weakens after a stressful event. It can affect the lungs by causing fluid to back up into them–a condition known as pulmonary edema. The brain sends neurological signals that turn grief into physical pain. Essentially, the heart betrays the body and drowns itself from the intensity of the mind. And yet, the body begins to heal. When you take that first breath of freedom again, it can feel new and painful—but it welcomes you to a newfound openness. The pleura heals, and the heart relearns its rhythm. You breathe love into new spaces, and your nest begins to grow once more.

Love takes many forms. You are created from it and placed in this world to give it back. First, you receive it from your mother and father; then you grow and find your closest friends—those you adore—and who you choose to give your love to next becomes what matters most. When you love yourself, you feed the bird’s nest inside of you. You build your nest knowing it is your safe place to rest and recover. You protect it with your heart and ribcage, and even allow it to be a place of nourishment for others. What we call heartbreak is not just metaphor—it is the body archiving loss in tissue, breath, and bone. And yet, even knowing the risk, we build the nest again. Love insists on returning, fragile as a bird’s nest and just as necessary for flight.

by Eryn

Camille Crawford

A tiny child sits alone at the dinner table beneath the warm glow of the kitchen light, her plate half-eaten as her parents rush through the next room, packing an overnight hospital bag. The blurred sounds of zippers and hushed voices fill the air. Her fork rests loosely in her hand as she struggles to form words. Her chest rises shallowly as she watches her parents move past, searching for even a breath of recognition—but they pass through her. The house hums with urgency while she fades quietly into the chair: present but unseen, already learning that even in stillness, she must not break.

The “Glass Child” will be expected to be healthy, capable, and resilient–the one who requires no emergency room visits, no specialized treatment plans, and no dedicated caretakers. Meanwhile, their sibling suffers from something they did not ask for. Yet, in this very “health,” they become invisible. Their lungs expand quietly so others can breathe easier.

Their struggles are not recorded in diagnostic criteria or tracked in medical charts; instead, they are contained in the tightening of their chest, the unspoken sigh before sleep, the silent gasp that never

leaves the throat. Always expected to be present but never waited on, this child grows too accustomed to worrying about others’ needs–never their own.

This tainted form of love is conditional, earned through perfection, silence, and being “no trouble at all.” They constantly exceed their family’s already toohigh expectations. But those in pain will always overshadow excellent test grades or groundbreaking achievements. Each success feels hollow, a temporary inhale before the next emergency. The guilt of seeking attention consumes them, yet leaves them perpetually starved for air.

Growing up in the dim periphery of another’s care–where attention is always drawn elsewhere– the Glass Child learns early that the family operates on triage. Their own issues are not a priority. Clinically, they internalize a role of secondary importance, adapting to the implicit family hierarchy where illness dictates the distribution of oxygen and care. These are praised for their maturity, but that maturity arises from necessity, not choice. Their ability to remain dependable and self-sufficient becomes both their

survival strategy and their suffocation.

This adult-like responsibility reshapes the entire family dynamic, causing a complete role reversal. According to Psychology Today, this experience is defined as parentification. This occurrence can arise from financial instability, the absence of a parental figure, or the presence of chronic illness. A child thrust into such independence becomes hypervigilant, learning to recognize the subtle cues that signal when to step out of their childlike role into one that demands compliance and care.

This hyper-responsibility rewires the body’s system itself: the lungs constrict at every sound, the diaphragm tightens before the crisis even arrives. The body of the Glass Child registers emotional invisibility as an unacknowledged form of trauma. While they appear strong on the surface, they carry feelings of jealousy and guilt–emotions that often remain unspoken. Over time, they may develop an affection for invisibility, believing that to be valued means to take up as little air as possible. But this self-effacing resilience becomes a carefully constructed mask, hiding the cost of

being overlooked in a household where survival depends on self-erasure.

Nights will become long and restless–a body trained to anticipate the next disturbance: a creaking down the hall, a sibling’s cough, the sudden call of a parent in need. Anxiety hums like static in the lungs, the chest tightens as if danger approaches fingers twitch, the heartbeat quickens at the slightest disruption. Even in moments of solace, the body refuses to believe it is safe–oxygen pulsing unevenly through veins as if preparing for a disaster that never arrives.

Over time, this invisible vigilance becomes second nature: gritted teeth, shallow breaths, stomachs tied in knots. Learning how to breathe just enough to soothe— never enough to rest. Experts in emotional triage, tending to everyone’s pain but their own. The world praises their strength, as they slowly erode from within, each withheld breath a small fracture beneath the surface. The Glass Child’s trauma is not shouted but whispered through sleepless nights, aching lungs, and a constant readiness to hold in what should have been exhaled long ago.

Victoria Jackson

In the dark, lodged between the hollow spaces, I am engulfed by you.

I spend my days lost within the lull of your sweet embrace. Nestled in your ribs, I cage myself in with your heart and lungs; your pulse reverberates–each beat an echo, a signal of my fate, etched into my marrow.

I, attached to you, am the universe; with outstretched fingers, I touch the outskirts of existence–a thin layer between the known and the nothing beyond you. I am alone in this world of your immaculate design–a kingdom or flesh and bone, created in your likeness, the reflection of your eye.

I wish to spend forever here, basking in infinite solitude, but a serpent slithers, a tree grows, and its bearings, I bite.

Paradise is falling–I cling to its sides.

You, my maker, pressed me from wet earth, clay, and bone, locked me in this garden, squeezed between a dream and a home, planted thoughts like seeds in my skull with such little time to grow.

As my limbs have begun to sprout, this cage grows smaller. My spine presses up against your tightening walls.

I feel the pull of gravity tug me towards the darkness beneath, into the abyss that lurks under my feet.

Mother, I am scared.

Is this the end?

Will you crack as I tear myself free?

My fingers dig deep, my legs push, my chest heaves–I kick; you scream.

What is on the other end of this invisible string?

Are you waiting there for me?

Light sears my eyes, my skin ablaze as I fall through space, There is a rip in time–I am eternally displaced.

My body convulses as my lungs expand and then deflate.

A cry rattles through me as my bones begin to ache.

That which has tethered me to you is now severed with a kiss, pressed upon my soft head before you lay down to rest.

A storm has centered around me; calm settled within my chest. I don’t know if this is death.

I close my eyes; I find myself back in the dark. It is now barren and bereft.

I take in air–a long inhale–there you are again.

Mother, you haven’t gone; I still feel you with every breath.

Selah Hassel

“Into my heart an air that kills / From yon far country blows.”

So begins one of A.E. Housman’s most haunting poems from A Shropshire Lad. His “air that kills” is memory and the ache of youth. Today, the air we speak of is growing intolerant and, quite literally, the air that kills. The lungs of the Earth fuels itself with panic–suffocation, a “help me,” and the frantic search around the room for relief. It seems, on a global scale, our hearts fail to sympathize with the damage we are causing–until of course, it finally catches up with our own.

What we often mistake for autonomy is heteronomy—behavior not freely chosen but quietly agreed upon, patterned by the systems we inhabit. In the factories, in the fields, in the exhaust-filled streets, even in the smokers’ economy, our lungs are the workplace. Within that workplace, humanity suffers from what is called the “Big Five”: asthma, COPD, acute lower

respiratory infections, lung cancer, and tuberculosis. These are among the most common causes of illness, disability, and death worldwide. Such symptoms derive from something chronic—our collective failure to imagine another way of living.

Our bodies read like letters to a younger self. They are sacred texts, testimonies we are called to recite aloud in one breath. If I were to look at my body through the eyes of the little girl I once was, I would apologize—for the damage inflicted, for the neglect in nourishment and movement, and for the recklessness of countless blurred Friday nights. For when life administers its pulmonary tests, the question of whether or not to poison ourselves is now hardly a choice at all.

Our current way of life is exhausting. We suffer physically from the impact of our decision fatigue. This works because, daily, it feels easier to choose the faster, cheaper, disposable option. Thus, instant gratification is a fever that festers in every unseen corner of our lives. What if we can not quit this bad habit? We will continue to strip forests and drain wetlands for our wants. Our dependencies will destroy our land for the sake of a growing economy, pushing us closer to tipping points we may

cross without ever noticing–until turning back is no longer possible.

This is slow violence, derived from the promises behind quick hushes of pleasure. We trade fresh air for the sting that quiets our mouths. After a sharp inhale, I knead my breast with my palm as an act of surrender, the pain, a remedy and the insatiable proof that I am still alive. Affliction is inscribed on ribs, on skin, in marrow, the lungs remind us of the problem of pain. Each contraction of the throat, even as it corrodes the body that bears it–is clinging to this paradox: pain as both a punishment and proof of our survival. The problem is that pain deceives us. It feels like vitality and, in some instances, maybe even a sense of control. Pain floods us with endorphins, confuses such torment with relief, and convinces us that this endurance itself is a pleasure, anchoring us to that cycle.

But that necessary breath–for both body and planet–is growing hypoxic. If we could see the exchange of our oxygen for what it really is—limited—I believe that everyone would treat the collective body with more tenderness. We would say: enough of the chemical. Every drag is a wildfire. So the question remains: can we imagine pleasure that does not cost us our world?

“That is the land of lost content, I see it shining plain, The happy highways where I went And cannot come again.”

And so we return to Housman: “Into my heart an air that kills.” Even the air that kills us, at its core, is the simplest commonwealth. Ventilation is what binds strangers and lovers, forests and cities. To blind ourselves to our own self-destruction is to blind ourselves to the world. But first, we have to admit we have a problem–and we have to hold ourselves–and those allowing mass destruction to our planet, accountable.

Even though we can not see the lungs inside of us, we know that if the diaphragm–that dome-shaped muscle cradling our breath–weakens, breathing then becomes a labored act. The delicate relationship we share with our body and the Earth serves as a reminder of the interconnectedness of us all.

The nature of breathing fully is involuntary, so we often discredit the magic behind it. We need to recognize that it can be more than passive survival or an outlet for pain. Breathing can also become an act of agency and discipline. If we live our lives with the intention to protect it and each other, we can open our eyes and finally come to respect the lungs and land of our primal home. Then, the “land of lost content” need not be lost. It can shine plain again, available for generations.

by

Jessica Giraldo

The myocardium is the heart’s muscle—its engine and endurance sustains and propels every contraction. Every movement, every breath, and every feeling owes its rhythm to this silent laborer. Once, in childhood, that pulse was wild—reckless in its joy, hammering at the ribs like a neverending song. We ran until we choked on laughter, until the thumping itself became an addiction. Even now, something in us keeps returning to that chaos, the unfiltered rush of being young and believing every beat promised forever.

The heart has four chambers—the right and left atrium, the right and left ventricle—each a room that receives and releases, that welcomes and lets go. Picture them as the entryways of an abandoned house. Through a window, you can almost see the dining table—set, but unscathed.

A strange, sponge-like cake sits in the center, surrounded by empty chairs. Red cells drift through the air, circling endlessly, never cutting the cake,

never fully coming down to rest. The house hums faintly, waiting for a guest that will never return.

Love, no matter how eternal it sounds, brings with it the white rabbit—darting just ahead of us, glancing back with bright, knowing eyes. It runs alongside every promise, every vow whispered with the certainty of youth, its presence a quiet reminder that even devotion has a pulse. We chase it because we still want to believe in forever, because part of us always will. But the rabbit keeps time. Longing works in a continuous cycle of reaching, contracting, releasing, and reaching again; its feet patter like a metronome beside us as even the most storybook heart grows tired.

We spend entire lifetimes retracing invisible pathways, searching for whatever once jolted us awake, whatever once made the chambers feel full. We mistake the body’s instinctive return for renewal, for destiny. Perhaps that is the nature of desire, not to be completed, but to continue its unending circuit.

The heart listens for itself in every pulse, always moving toward the promise of something more.

by

Lauren Boonstra

The phantom does not haunt the atrium. No fibrillations beat against spongy pink walls— only an imposing silence that begs me: Listen. But for what? There are no cues.

There is an awareness here of elapsing time that the phantom does not want to touch, a sentiment that stifles but never knocks.

The atrium is desolate–a wide expanse of empty space where company is only imagined in peripheral vision.

Wallpaper, shot through with deoxidized blue, swells and deflates on occasion, willing me to follow its veiny trail.

T———dum, —dum, Tu-

The valves are noisy on occasion, the air here full of creaks and bangs that disturb the moment’s silence.

The wallpaper’s veins bulge outward, nearly escaping their trappings to coat the floor with their refuse.

The flaps of the valves open and close like swinging doors, in tune with uneven pulmonary pulses.

The spirit passes through here, it’s residual breath fogging the hallway with afterimages of bruised knees,

whispered secrets, and elementary humiliations.

But the ghost never lingers long. A door swinging closed signals its leave.

Tu-dum, Tu-dum, Tu-dum, Tu-dum

My bedroom has been co-opted by a ghost. It rests, nestled between towers of taxidermy in my bed.

Plastic cars in hues of fuchsia collide in a series of crashes without a hand to guide them.

The phantom watches from within a plush cocoon, half-concealed by a tulle tapestry that hangs down. Coiled like a snake, the aorta houses the haunting. The ghoul leaves glitter sprinkled across the carpeted floor, caught in its gaps like some kind of confettied ectoplasm. There is a taste on my tongue–like

that of cherry popsicles in summer, the anxiety of trying to finish before it melts present on my taste buds, too.

I know it is the ghost’s doing; there is no one else whose presence would taste so sweet.

The veins in the walls transform into branches, each one bearing finger-painted leaves in colors unnatural, pastel, and neon.

I smell grape in the air, the artificial kind found only in a Magic Marker with its cap absent.

The ghost wears it as a perfume. I climb into bed beside her, burrowingin between plush rabbits and puppies.

Here the phantom remains beside me, amidst glitter, grapes, and groans. It is hard for her to believe that I have ever been alone. Yet in the morning, I must wake, returning to the noiseless atrium, where the ghost is just recollection–, a seductive thing that only pulls me in closer to the rhythm of its reminiscence.

I want to hold her tight and steal the innocence pebbled across her skin for myself, but when I reach, she dissipates like a plume of smoke.

by

Kaya O’Rourke

Old television sets and hosptal-grade heart monitors exist within the same strange sphere. Both blink to life, their light flickering across a screen to reveal something vital. Hospitals are equipped with televisions for their patrons to scratch an uncomfortable itch as they wait for a doctor to help them. If you stop to think about it, the glow of a movie screen feels eerily akin to the machinery that tracks our hearts—on and off, pulse and static, the same electric tremor that romance leaves behind. Each flicker, flatline, and spike captures the wild rhythm of falling in and out of love.

This kind of ache does not reside within the mind, but within the body itself–deep in the myocardium, where the heart contracts and releases in quiet rebellion. Longing is not simply emotional–it is physiological; a disturbing cardiac rhythm and bending time into suspension. When we yearn, the ventricles tighten around a name, a memory, even a face that never really belonged to us, no matter how badly we wanted it to. The body reacts before reason: pupils dilate, breath hitches, and the skin hums with awareness–all working together to become an echo chamber of desire. More importantly though, our hearts burn and sting, leaving us with a sharp, powerful feeling.

In cinema, this sensation transmutes into visual poetry. It unfolds onscreen through lingering glances, pauses in dialogue that last just a beat too long, and confessions left unsaid. These gestures—paired with the internal ache of not feeling enough, the instinct to mold oneself into a lover’s ideal, or the dizzying instant when their gaze finally meets the protagonist’s—reveal how desire transforms both the personal and collective body, allowing film to shape the invisible architecture of wanting.

Wong Kar-wai’s drama film In the Mood for Love (2000) is one of cinema’s most delicate portrayals of restrained desire. Its cinematography breathes in tandem with its characters–slow, deliberate, always one step behind the heart. The two leads, Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan, move through dimly lit hallways like blood flowing to keep us alive. Each shared glance becomes a systole; each retreat, a diastole–the myocardium flexing between impulse and restraint. This leaves the heart beating faster than we are used to without spiking, steadying for brief moments to remind you of the brewing tension deep inside. Their yearning is physical yet wordless, alive in the tightening of shoulders and the brush of silk against skin. It is love suspended in arrhythmia–a heart refusing to rest.

In Joe Wright’s Atonement (2007), starring Kiera Knightly and James McAvoy, longing transforms into a chronic cardiac condition–inflammation without cure. Their love story is severed by a lie, turning the remainder of the film runtime into the struggle of breathing through a blocked artery. Separation accentuates every heartbeat and memory, each one growing heavier and sharper with every blink. The letters they exchange are artificial pulses–desperate attempts to revive what the world has already pronounced dead. One long soundwave to signify a flatline, then intermittent beeps when our memories remember something we thought was long gone. The imagined, guilt-ridden reunion that closes the film is a postmortem rhythm;a dream that offers comfort even as it reminds us of what has been lost. Here, longing is both the pain and proof of love’s endurance.

2016’s Academy Award winning film Moonlight by director Barry Jenkins turns yearning inward, translating it into a quiet, aching heartbeat beneath the surface of Chiron’s identity. His desire for Kevin is tender but repressed, his silence a defense mechanism against the world’s violence. When they reunite as adults, the air itself seems to breathe with potential energy–the heart preparing itself to beat freely once more. Their conversation is hesitant but gentle, every pause weighted with shared history. The simplicity of the touch in the diner becomes a moment of reoxygenation, blood flow returning to the long-numb chambers of selfhood. Like the stabilization of the heart, there is a return to the heart’s normal rhythm. It says everything words cannot–the ache, the forgiveness, the relief of finally being seen. Moonlight turns yearning into a kind of healing: a slow, steady return of warmth to a heart that had forgotten how to feel.

Across these three films, we witness an embodiment of heart palpitations–each one portraying the failure to maintain steady rhythm under the pressure of restrained love. Longing is not passive; it is transformative. It reshapes bodies, rewires minds, and carves new pathways through the heart’s dense tissue. Each incision becomes a record of survival, proof that the heart adapts to the ache it cannot escape. Desire, in this way, is both wound and repair—tearing through what was once whole only to let light, oxygen, and new rhythm in. We feel our own pulse tighten with restraint, falter under pressure, then slow and steady itself, learning to beat without restraint.

Each story, then, mirrors the body’s response to love. Heart monitors beep loud and relentless, offering proof of life—much like the heart itself. Their rhythm reminds us that longing never ceases; it only contracts and releases, keeping us alive through every flicker, every fade

Photo by Eryn Wagner

by Lydia

“Iron rusts from disuse, stagnant water loses its purity and in cold weather becomes frozen; even so does inaction sap the vigors of the mind.”

The stillness yet restlessness of the body is consistent no matter how hard your heart beats, no matter how much blood is pumped through you. The embodiment of a lifeless object reflects the stagnant feelings that come with being human. Protecting your heart, with the assistance of the epicardium, creates this shell of hope inside all of us. Our myocardium allows us to push harder and overexerts itself toward what we know will end the cycle. Whether it is conscious or subconscious, your heart understands the need to break the curse.

We injure ourselves by allowing stagnation to grow and spread.. Being afraid of feelings only pushes them deeper within, and your cardiomyocytes work harder to provide your body with what it needs. The fast-paced beating, burning, and sinking feel as if they are welcomed by you. The lack of coordination between the mind and body causes internal stress and inflammation, together signaling that you should go beyond your reach!

No one tells you how vital it is to yearn for something more–something that could be. There is so much life constantly flowing from your heart;

- Leonardo Da

Vinci

it is easy to give that bodily function purpose. As humans, we are given the ability to look at our lives and change our future to better suit what we desire, but I feel as though we take that for granted. Existing in stagnation is not living life to the fullest. Your heart knows what you are capable of reaching, so why not strive for greatness? When the alternative is being stuck and on tenterhooks, the answer seems obvious.

The process of growing is not always easy if your heart is not in it. Sometimes you have to sit in the bad feelings and wonder what you could add to give your life value. The rush that comes from your mind matching the energy your heart is putting in–that is just a taste of what your life can and will become. The vibrance that follows once you understand that you are allowed to dream bigger than just existing is sultry. The passions you connect with, the goals you reach, and the purpose you give to living in this society are resilient. You have to be honest with yourself and consider who you are truly living for and why; your heart is beating for you and you only. The mind-body connection builds the soul–a soul that is heart-stirring.

Finding myself in a place where I faced the same trials consistently–repetition, overwhelmed, lack of control and motivation–taught me how sticky stagnation can truly be. The concept of your mind and heart being in different worlds within the same universe is tiring. My heart compensating for my mental exhaustion by overworking itself was involuntary, yet I unknowingly had complete control over it. I faced an internal battle with my heart and its intercalated discs time after time, telling it to push forward and win. Not recognizing that I was sinking in the water that then became mud allowed me to embrace the stagnation and not see the potential I could have been reaching for.

Our being is not only mind, body, or soul–they are a team. This team helped me find exactly what I was looking for: a breakthrough on the surface. In such a stiff position, I stopped listening solely to what was in my mind and followed the signals from within the myocardium. It takes trial and error to find a way out, and the only way out is through. Swim through the mud. There is never only one way to fulfill your soul; your journey is entirely meant for you to experience. Once you can climb your way back onto land, the mind and body become one, your heart is at ease, your thoughts are steady, and your soul is eager with passion. The myocardium is the hardest worker in the body–don’t let it operate solo; you need each other.

The day you’ve been waiting for, has ultimately arrived. Dress on the door–I long to be alive.

Anticipation squeezes–wrings–strangles your heart. Consumed by longing, unattainable from the start.

1-2-3-sound the knocks from your friends! Hesitate at the knob, kid; think again. Your heart is only a means to an end. To set you free would be less than human.

Visions of warm unfamiliarity wrapped in cerecloth, I have saved a seat for nostalgia’s evanescence. Ornamental swaddled presents litter tables at unholy costs, your voice shakes with gratitude for the pity of one’s presence.

I’ve sliced every serving of myself on a silver plate, yet you turn your nose upright at my hospitality; prophesize my certain consumption as heaven’s fate, inevitable as a shattered set of china tea.

Crooked smiles with wide-eyed stares, as loved ones croon to a familiar tune.

Hunger strikes again, craving to be consumed, preserved through routine party affairs. Destruction seeps from my pulsing open wound, the center of everyone’s crosshairs.

Decomposing innocence, the soul’s first heartbreak. Gouge me with a spoon and rip me to confetti shreds.

You were the one responsible for the birthday cake, the audience granted you the go-ahead.

Eat your heart out, kid.

by

Jessica Giraldo

What they do not tell you about growing up a very lonely little girl is that a part of you will always remain that same very lonely little girl. Ever since I was a child, I loved staying up late, tracing one flicker of feeling until it unraveled into a manuscript of fairytales. Lingering inside me still is that young orphan: chasing ghosts, clinging to the shimmer of affection.

My heart is a small, ornate music box–the varnish of its plum case scuffed from mishandling, a dozen tiny gold stars inlaid on the inside of the lid, with an angel mid-sorrow forever bowed on a screw, wings chipped, turning for eternity. Wind the mechanism, and the same song rises, patient and exact. My chest ticks like an antique metronome—mechanical, faithful, occasionally cruel—as the ventricles squeeze and valves snap shut.

When the winding calms down, the rhythm that remains is Tell-Tale Heart—a private madness of merciless drums. In its possession, this cognitive compulsion makes my companions knock, insisting they have nowhere else to go besides to become a melody I return to on the page. This exclusive chord becomes pure romance, keeping the spirit of every wound eternally pulsing.

Yet I noticed that what once felt like an alluring fault in my machinery suddenly belonged to a wider experiment—one a poetry professor seemed to name when she joked that young female poets were the most depressed people alive. The room laughed; I laughed too. In truth, we were all music boxes from the same factory, our chests splitting open in harmony, bleeding out metallic lullabies.

In 2001, psychologist James Kaufman published The Sylvia Plath Effect, a study that analyzed 1,629 writers and found that female poets were significantly more likely to suffer from mental illness than female fiction writers or male writers of any type. The report read like an autopsy of my soul, leaving me both relieved and violated, winding tight in my chest until I could hear my own pulse flinch.

When science says I am wired to suffer, the shame I feel for wanting anything at all becomes justified—a long-term, self-proclaimed prophecy. Each time I reached for a connection, it felt like a Barbie doll in the box that I was never allowed to open—perfect condition, limited edition. I swore I could love like a psychologist: observe, not touch. Yet every time, I tore the box open with my teeth.

The forbiddenness made the lonely little girl inside me twist the gear, whispering that if I just gave enough, bent into devotion, then perhaps she would let me play with her once. The longing surged with each high spike of systole and fell silent with each hush of diastole.

The lonely girl inside me conducted an orchestra for the phantoms, and by the spring performance, I could no longer tell whether I was the composer or the possessed. The

days blurred—delirious, unmedicated, feverish—as I filled my journal, trying to chart the chaos. Page after page, I traced where I was, who I was with, who I wanted, and why— and my God, did the pattern reveal itself.

When I finally stepped back, the truth was unbearable in its familiarity. My therapist’s words echoed: I was “rewriting” my childhood by abandoning myself in every reenactment. Every poem was pain disguised as purpose. Still, I told myself, at least I had something to write about.

I have always given the muse more authority than it deserved, letting it drain me dry to keep the story alive. But I am not its offering. I am not a divine, tragic thing forever nailed to a wooden box. I see it now—the same prophecy rehearsed in prettier

language each time. I refuse to keep conducting the same score.

This notion–the one I had traced across the margins of my notebooks–stemmed from two realizations: first, that I was worth more than that lonely little girl I thought I was, and second, that I would have to learn to hold her all by myself. No exquisite poem carved from grief can grant her justice, nor make living inside the wound noble.

When the orchestrator inside me finally set down her baton, the murmur was unbearable—and then, astonishingly, kind. It was the first sound of forgiveness I had ever recognized. The prophecy was never destiny; it was only a childish lullaby. Buried within the amaranthine, mechanical cathedral of my ribs, the lonely girl hums a coda through the pipes of my organ.

Jessica Giraldo

The shoreline hums under heavy air before the light comes, salt clinging to the throat at the edge of the tide as darkness begins to move through. Knees to chest, spine curved like a crescent moon; the sand folds beneath you, cool and damp, as if the earth itself exhales. The sun dips lower, its gold bleeding into rust, then into the deep bruise of dusk. The light thins across the water, a final confession before it sinks. Warmth leaves your shins first, then your hands. Everything slows: breath, tide, thought.

At the base of the skull, the neck bears the fracturing world. We hold our heads still, as if any movement might make the loss real. This is where disbelief lives, in the trembling between head and heart. We say no with our whole body: jaw

locked, throat constricted, eyes wide in refusal. The cervical spine strains to carry what we cannot yet name.

Mid-back, the thoracic burns. The ribs tighten around the lungs, and anger doesn’t always roar; sometimes it simmers—a pressure in the chest demanding release. Between the shoulder blades, the heat of what we’ve lost gathers. We lash out not because we hate, but because we cannot yet accept that love has nowhere left to go. If only I had…if only they could…

The lumbar holds the heaviest weight. We bend, plead, make invisible trade deals with air. The muscles knot with yearning, caught between hope and surrender.

The sacrum anchors us to the earth as grief spreads through the hips. We stop reaching, stop rising. As the pulse slows, we meet our sorrow fully—wordless and raw. There’s a strange intimacy in this stillness, a recognition that to suffer is to touch the deepest part of being human.

At last, the coccyx rests. Grief softens, becoming something we can live beside. The loss doesn’t leave; it only changes position, threading itself through the nervous system, humming quietly in the background of our days. By the time the sun stands high, it’s hard to tell if grief is a tidal wave that pulls you under or a familiar companion sitting beside you all along.

Selah Hassel

Grief resists diagnosis. It presents not as a disease, but as a symptom. The doctors keep looking for an exit wound, some proof that what is missing might show up on a scan, but there is nothing. Before the pain knocks you dumb, before you feel anything at all, the loss has already metastasized in your bones. I think of Dagoty’s Anatomical Angel, that figure turning over one excavated shoulder, trying to see herself–split apart. Something in that gesture symbolizes the intrinsic need to circulate our pain, to understand it, to locate the source of burning. I believe this speaks for our physical relationship with grief. It is a wound we keep turning toward in an attempt to understand where it began and just how deep it goes. There is no real answer, only the quiet work of living without.

Your mind’s first instinct is to name the pressure building between vertebrae C-five and six—a stubborn knot. Thinking it will eventually knead itself out. As your fingers trace the bone ladder of your spine, pressing into the small ridges of muscle, the ache blooms wider. You dig your knuckles into your own tissue as far as you can for relief, yet the pain travels up higher through the cervical column like a quiet current. Perhaps the pain remembers something you can not quite place, so it keeps screaming at you to notice. Though I guess it is common knowledge that when something is lost, it is rather ever-present.

Mourning turns nights sleepless—rising rates of insomnia and the ever-shifting way of lying on

your back. Mourning looms like a cold. Mourning is that phrase everyone hates when they are grieving: “the world keeps spinning.” Here the body is transforming emotional turmoil into a physical canvas for pain.

Confident that a diagnosis is submission to defeat, you stay in bed and let the symptom consume. Your heart rate spikes—it is a pulse you can feel in your throat. The pain in your shoulder blade travels to the base of your thoracic. Several words appear, images along with it—herniation, nerve compression, stenosis. Then suddenly the body remembers the familiar warmth of touch and stiffens, awaiting an embrace. It never comes. You fear that the pain is proof something inside you is permanently damaged—breaking at every bend—but you cannot discern whether it is your bones or your memory.

As I got older, I became more familiar with the phenomenon of health anxiety and its paradoxical relationship to grief. I remember sleepless nights in my youth, gripped by the sudden revelation of my own mortality. I would lie still and quiet beneath the shaking ceiling fan, practicing the art of relaxing every muscle in my body. My mind grew so calm it welcomed questions of what it might feel like to truly let go. Yet it wasn’t necessarily fear that kept me awake—it was the need for certainty. I wished to know that when the moment came, I would be prepared to meet it gently.

It was not long after those years that the weight of my own body found a way to

suffocate me. Change circulated in my everyday life. Because of this, my anxiety propelled me. I cursed my heart for beating like a rabid animal, angry in its cage, cursed my blood for running, my teeth for their chatter. Each pulse was a reminder that I was trapped inside something so alive. Everywhere I went felt like a prison cell for I could not get my heart to stop palpitating. I knew I could not run away from myself. I found my mind subconsciously praying for the complete absence of feeling.

That sensation of impending doom still coils within me, but I am wise enough now to wash away the guilt that follows— its underbelly full of desire: to see again what was lost and to follow it. But now I understand this common cause of panic. Often, presence is missing. For loss is not just emotional, nor merely psychological—it manifests as the body turns its bones. However, recognizing what is missing, naming it, and learning how to move forward may be the first step toward reclaiming health.

You cannot let your losses nail your feet to the ground, nor can you neglect your wounds. You have to want to keep them clean, because grief is not synonymous with death. To confront death after loss is to choose to stay in the body—to release the grip on the spine, to let the nervous system quiet. To lie back on the same bed that once kept you up, feel the vertebrae align and breathe until the body remembers it is alive. Absence remains, but it no longer grows. The spine holds. The heart is loud. Love is not buried with the dead.

Photo by Molly Melton

The mirror hangs crooked, shattering glass splayed, reflection foggy, shards spilling down to the floor.

The creature sits centred to Its image–distorted.

Hunching, covered in flesh, flesh, flesh, nothing but bone piercing through delicate skin.

Sitting in silence, limbs tucking into the depths of Its ribs.

The creature stares, eyes piercing into Its reflection, mocking each crevice of Its carcass. It crawls closer toward Its reflection.

Spinal cord crracking, glass shards lacerating–tear–tearing into Its skin.

Blades, box cutters, thorns carving deeper into Its abdomen, so deep it can’t look away.

It shudders at the sight of Its demonic figure, cutting deeper as It stares, carrying the pain that is all too much to bear.

Blood melts down into Its skin.

So much blood, blood in every crevice.

The creature lies down on Its back.

Twisting, turning, breaking, skin to bone, bone to skin.

Gravity weighs heavy, smothering Its ribs, crrushing its neural cord into a hideous spiral.

The creature hunches over; It can hear Its skin rubbing against Its backbone–tendon pulling taut, grinding teeth at night. Unpleasant!

Her mind fills up with thoughts:

Too skinny, boney, weak, frail n thin.

She cries out to God, cursing this creation, a creature designed from the firey pits of the underworld.

The mirror falls to the floor, she hunches once more–a creature to society, and nothing more.

by

Victoria M. Jackson

“I see that man going back down with a heavy yet measured step toward the torment of which he will never know the end. That hour like a breathing-space which returns as surely as his suffering, that is the hour of consciousness. At each of those moments when he leaves the heights and gradually sinks toward the lairs of the gods, he is superior to his fate. He is stronger than his rock.”

– Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus

The black sun beats down my withered back; the skin blisters and cracks. The dark rays carve into me–another hour, another century–another line etched into my marrow. Where this weight takes claim of my eternal mortal body—where a heart is numb of lack. It crushes my spine, though fragmented, it remains upright as I tread that uphill climb— an internal mosaic of every wretched time —the stairs of my back grazed heaven, then collapsed.

Beyond the stone, I see a glimpse of my past–a phantom memory of home.

My name cascades from my mother’s tongue; her warm breath cradles my infant nose. In this torment, this is where my mind longs to go.

In youth, we lament and are swaddled, —in death, our mothers are gods, with no time to sweetly coddle.

I attempt to capture the heat; the fervent m in emory crumbles in my wake.

Treading up that unforgiving slope– knee to chest–I try to catch my breath.

Each gasp, a futile prayer for air, however, meaningless in a world without atmosphere.

Still, it remains a ritual of mine; to pretend I am among those with lungs that are alive. With each shallow inhale, every staggered in my step, I reach the summit.

—above my fate, I stand, and the gods do not know what they have given me.

The stone descends–my hour begins—and I, who have reveled in sin, is born yet again. Ecstasy of the mind—the nerves that map out the passage of time seize my soul, and I fly. In the world above, in a time of many moons long since passed beneath softer suns, I once was a man who knew every star in the night sky—where these strong legs once danced. I could recall the name of each blade of grass, and the sound of my father’s laugh

—I have memorized every face I have ever seen, the imprint by their cheek.

In life, I was a greedy man- I cheated death; slipped a chain, a noose, around her neck. I clawed my way free, a momentary lapse in divinity.

I lived on borrowed time, craving one more dawn, one more pulse of light. Years gathered like ash; my body withered away, and those I loved perished, and I, one foot in the grave, left to mourn those I have lost for the rest of my mortal days, —how I miss that miserable plain and must pay the price for the passions of its rain.

In my final moments before all is lost again, I brace myself and look down upon my old friend.

The mist of my eyes fog the scene as I enter back, another step towards my tormented path. The moment glistens, flickers as it absolves; its remains whisper, the hour falls, as forever calls. I will never reach the end— the eternal climb, which I will do yet again. But the weight of my stone has meaning at last —in the hour where it has become my past.

As I greet the stone, I kiss it for it has given me a home, and nature’s taken claim of my bones. Love rises within me as a smile begins to take shape;—it morphs into the sea and sky— every great escape, I had the pleasure of its weight.

I draw one more breath; I embrace my death with each step, clutching the secret I have kept. Memory binds the soul—and through it, I know of what the gods don’t know, —that they have given me hope.

Jessica Giraldo

“He placed his hand upon the trunk and felt the heart still beating beneath the bark.”

— Ovid, Metamorphoses I.553

I.

The dirt clings to our knees, as your finger finds the hinge of my jaw–the first touch of bone I’ve felt in months. Hand at my waist, tracing each discs, reading the braille inscribed against my vertebrae, then rising, you graze my ribs. Go higher, find the seam that trembles at my throat. Do you mean to unwind me slow, or bury me whole?

II.

The air splinters as your axis tilts–trembling lips divide like a fault line. Each breath drives your gravity through me, settling in my sacrum. I want to let you. I want your devotion to the hidden choir of marrow and sinew humming beneath my skin. I want to slip my fingers through the soft lattice that keeps you aligned, watch as your spine bends against the pressure of my palms.

III.

The column of my cartilage tremors at the sight—your neck bowed back, the mouth of heaven parting. You whisper my name like a ritual, a soft plea leaving the flushed lips of a soft pink apparition. From that small purgatory, I almost stopped straining.

IV. I want to lean towards you, though I’ve prayed to the wrong god before—planting my love into Earth’s exhausted garden of eternity. For months I slept there— grieving the hurricane winds from her absence that howled through my branches covered in the sap—retaining the rot. I still bear her carnage from Eden.

V. God storms through me turning my essence into wood, spine to trunk, so I cannot collapse into you. My toes clutch the earth, sprouting roots into the soil, carving my calves with bark–foolish to consume your fertilizer, while I bleed dry of crimson pulp.

VI. Take the droughted berries and turn them into raisins. Candied, rotted, pruned— sweet enough to swallow the bittersweet duality of me. God averts His eyes from what He’s curated–a forsaken metamorphosis euthanizing me–calling it mercy.

You were always tired, coming home to stand still for the first time all day, your hands wrecked with grease and fire, nicotine clinging to the dark walls of your jacket. Your spine less vertebrae and more rope, a series of knots crossing and tightening through you–though you never mentioned the pain. Feet so numb you couldn’t feel the ground beneath you.

Now you have calloused deeper–sunken beneath that weathered old ship of a body, bruised so blue you float from room to room, a ghost throwing shadows in our house.

Right back to work after it happened. A mother and father taken from you in one cruel, clean snap–one phone call, and two roots yanked out from beneath you. But right back to what you know,

and what else have you known but labor? Return to flame, to rush, to pressure, return because your bones cannot settle. Orbit that ache in dutiful circles, refuse rest like your fathers before you.

Looking at you I wonder how often you turn them over in your mind–Do you think of the last words you said to them? Have they become soft and worn-in or do they still ring like a sharp bell between your ears?

You come home now and carry that load with you. I hear it from your car up the street, in the way you turn the key through the door. Everything you touch feels it too; your bedsheets sink from beneath you. Your leather hands press into my palm, pull me down into the unknown waters you are drowning in.

See the grooves and lines running through your face, are you seeing him? Carry on the exhaustion that lingered

his whole life and weave it into your bones like a birthright. How many bodies has it passed through now, how many spines has it warped and rendered useless?

You fall asleep bathing in TV glow. I watch your back rise and fall in the flickering light; wondering why you hoard grief in your joints, tendons, and muscles? Why you hold it tight, lie beside it, will not let us take an ounce of it away from you.

Bearing your load dutifully; you need it–as if leaning on someone meant you would never stand again.

Keep it to yourself, even if it makes you go pale and buckles your back crooked. Hold it all and wait, patiently, for it to fall. Wait for it to slip from the walls of your skull, and sink to your foundation. Carry on, wait.

All you have ever let me do is watch.

by