the bears Stadium soap opera

John: We are talking about the Chicago Bears stadium, which has been an ongoing soap opera, flipping back and forth between the lakefront and Arlington Heights. First, from 2021 to 2023, it was going to be Arlington Heights, where they purchased the old Arlington Park Racecourse. Then, they flipped it to Chicago.

The Bears franchise wanted $2.4 billion from public funds for a new lakefront stadium in 2024. The Illinois General Assembly never proposed legislation on this, but Gov. JB Pritzker let it be known he was not in favor. Speaker of the House Emanuel “Chris” Welch had the same response, so they were back to Arlington Heights. Unlike Jacksonville, unlike Buffalo, who have worked out their stadium plans, Chicago remains in limbo.

Russell: The Bears should stay in Chicago. I would hate to see them go to Arlington Heights, but they have all that property there, so they have to do something with it. It could be four or five years, though, so in the meantime, enjoy Soldier Field.

Allen: Soldier Field is a good part of Chicago. To me it’s a historic landmark as far as football games for the Bears. Not only the Bears, but the Chicago Fire too. And a lot of activities, including concerts. They say they would have the Chicago Marathon there. I don’t know how that would work, because the Marathon is 26.2 miles, so I think they mean the ceremonies at the beginning and end.

And in June, the Fire announced plans for a privately funded, soccer-only field along the Chicago River at Roosevelt.

John: The Bears’s lease is not up until 2033, but they can leave there in 2026 if they think Arlington Heights is ready to go. The problem is, if they leave after the 2026 season, they would have to pay a hefty tax. That’s why I think the politicians in Illinois are playing with which way the wind blows.

They did that in 2002, during reconstruction of Soldier Field, when the Bears played in Memorial Stadium at the U of I Champaign. Now the Bears want to ask for a new loan. I think that is kind of suicidal on the part of the Bears and the city itself. Not only Chicago, but the state of Illinois can’t get its act together in terms of pensions: $144 billion is still owed, and there is also a declining population. If you ask me, the likelihood is Arlington Heights, but we’ve seen this soap opera before.

Russell: I think this is just status of the field. Remodel it. Same with Cubs at Wrigley Field: an old property, remodel it. The New York Giants play in New Jersey, they’re not the New York Giants.

Allen: I am like Russell. Soldier Field has a special place in my heart and will forever be a Chicago landmark. They talk about tearing it down,

but they should leave a couple columns and some scoreboards so you can see the score of the game wherever they may be playing. Whenever I go by there on a Sunday, I get a special feeling for football because I can see the fans going into the stadium. And then when the game is over, I can tell by the looks on their faces whether the Bears won or lost.

John: I can see where the Bears are coming from in terms of a retractable dome. These state-of-the-art domes are more than just eight games at home. They want 65,000-seating not only for Bears games, but potentially Super Bowl, Final Four, college basketball, concerts.

Any comments, suggestions or topic ideas for the SportsWise team? Email StreetWise Editor Suzanne Hanney at suzannestreetwise@yahoo.com

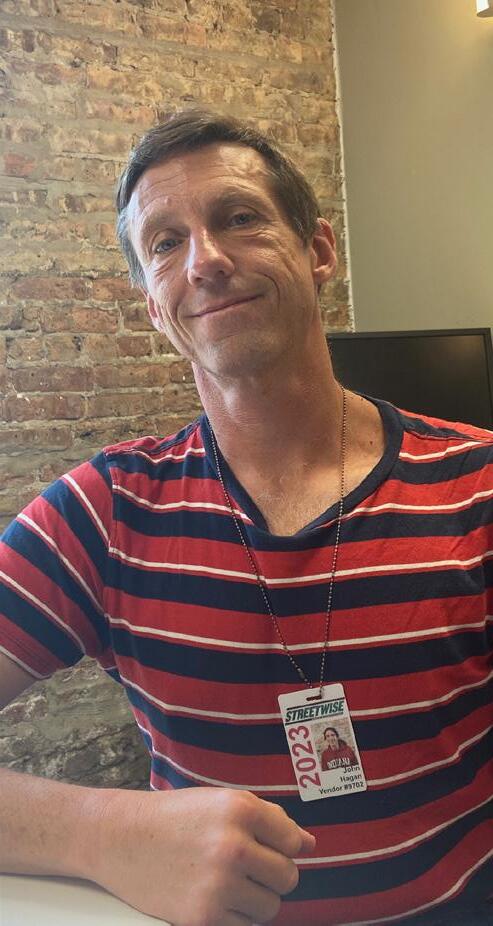

Vendors John Hagan, Russell Adams and A. Allen chat about the world of sports.

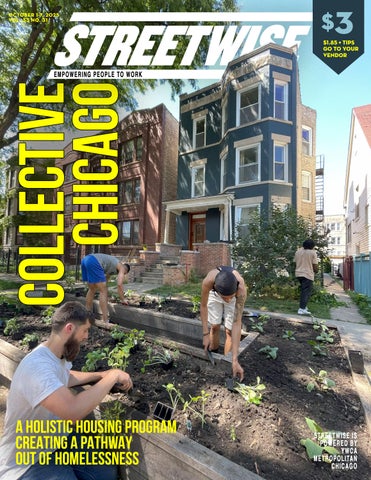

How holistic housing programs are creating pathways out of homelessness

by Patience Hurston

The blue three-flat in Uptown looks like every other house on the block. The garden beds out front are still thawing out after a cold winter. A few raspberries litter the steps leading to the front door, but a small bird, who has made the front awning its new home, drops down every few minutes to gobble them up. The red latched gate leading around the side of the house opens to a quiet backyard with a handmade, in-ground fire pit that sits unlit.

For the last 10 months, Avante Matthews has called this place home.

Matthews, a transplant from Memphis, came to Chicago after graduating high school to build a better relationship with his father. But after a falling out and several months of bouncing between his grandmother’s, his partner’s and a friend’s houses, he was charged with a felony and put on 24 months of probation, making it extremely difficult to find stable housing and employment.

At first, he spent a few months at a friend’s house on 77th and Commercial. "It's a not-so-great area, but I was happy enough to have some[where]; that was my main thing,” said Matthews.

But due to the terms of his probation, he could no longer stay with the community he had in the city and couldn’t travel back to Memphis to be with his mom. He called 311 about places to go for the duration of his probation. The operator referred him to Collective Chicago, a housing-first nonprofit based in the Uptown neighborhood of Chicago working to combat chronic homelessness by combining affordable housing with restorative community care. The organization provides rent-capped housing in its co-living community where residents receive help with job searches, financial advice, therapy and access to healthcare.

“I got a break from the violence. I can sleep comfortably; I could cook my own meals. I didn't have to worry about anybody else being in harm or putting myself in harm's way,” Matthews said. “It was like I was calm and collected when I first got in. My first night here, I slept for like 12 hours straight. I say it was a good sleep.”

The collective serves young men across Chicago between the ages 18 and 35 who have a history of at least 3 months of homelessness or couch hopping.

Opened in 2018, Collective Chicago had been a long time coming for cofounders Dan Minea and Adam Gianforte, who currently serve as respective executive director and president of the board.

The duo were roommates in Uptown and had built a relationship with a local tent community, allowing people to come do laundry and charge their phones at their nearby apartment. “We would just go hang out with the tent community and our friends there,” Minea said. “I quickly invited [Adam] into all those things and relationships with people that I knew and… it was just like, 'oh, this is, this is where the goodness is,’ not to be the provider, but to be present in that space.”

Gianforte was invited to live in the tent community with their friends, where he played violin and busked for seven months. After the alderman shut the tent community down and the duo consulted their landlord, they invited four of their unhoused friends into their two-bedroom apartment until their lease was up.

Minea said the idea for the collective was born out of “how do we get to stay here in this space?” stemming from the love for the communal care they were providing their friends.

His biggest concern? How to fund communal living. It’s something that racked his brain as an ad sales consultant at Viacom before the launch of Collective Chicago. “We just can't make the money make sense. Where can we live the way we want to be in the community?”

Application process

Applications are submitted through the collective's website and once they are looked over, potential residents go through a four-step process, meeting with Minea and the collective’s coaches to begin creating a resume. Because

many applicants are from the South and West Sides, the collective only does two rounds of in-person meetings (a half-day meeting with the coaches and a dinner with the current residents) to keep things accessible, said Minea. For every available spot, the collective received 125 applications last year, which Minea said is about the average for the last few years.

For young men who aren’t accepted into the program “we connect them to a variety of different resources and next steps,” said Minea.

“We have a little score system where the level of need is the number one, most, highest, regardless of all the other criteria,” said Minea. The second step is a resume workshop, ensuring even if someone doesn’t make it into the program they still leave with a resource. The final step

is a dinner with their potential housemates, where both parties get grilled on how well they’ll mesh in the house.

Tristion McDowell, the director of community development and engagement, said he’s seen how protective residents get when inviting new people in.

“The longer a resident stays, the more protective they are of the space, the more they ask them legitimate questions and things,” said McDowell. “And when the potential resident or applicant asks the residents, ‘what is it like here?’ We've heard multiple times that ‘this is not a real place, right? This is a place that doesn't exist in the real world.’”

“It was more kind of like showing your best self,” said Matthews. “The best version of yourself to the current residents putting the best effort out, despite your past, what you are looking towards and what you trying to do to get in.”

Dignified Affordable Housing

Once accepted into the program, residents receive housing, a cell phone, laptop, groceries, transit, mental health resources, a gym membership, physical therapy, professional attire, financial management, life coaching, legal aid and education and lifestyle resources like cooking classes.

Each floor of the collective house has a few bedrooms near the back of the apartment, with open furnished communal space where residents can read, work and relax.

Residents rearrange the common spaces as needed. A recent arrival turned the back corner of one floor into a makeshift music studio complete with a keyboard, guitar and microphone.

Minea calls it, “some of the most dignified affordable housing in Chicago.”

The second floor holds a large 12-seat dining table where residents and the collective’s life coaches have weekly dinners, vet potential new residents and catch up on the week. Matthews had his final dinner before his graduation on Wednesday, April 23.

The life coaches at the collective meet with residents to help them write resumes, apply for jobs, organize the weekly house meals and the bi-monthly fundraising events.

Avante Matthews sits in front of Collective Chicago, a housing-first nonprofit working to combat chronic homelessness by combining affordable housing with restorative community care (Patience Hurston photo).

The first 45 days of living and working in the collective are free, with residents working with coaches and creating their financial plan. After 45 days, residents begin paying rent, which is capped at $400 a month, a buy-in that Minea says makes the place feel more like home. The rest of their paychecks are split between savings and spending. The average resident saves about $1,880 per month.

Coaches meet with residents at least once a week, depending on how much a resident is working per week. Meetings with coaches decrease in frequency when residents gain employment. Unemployed residents meet with coaches four times a week, and spend four to five hours daily on resumes, job applications and assessing their finances.

Getting Jobs and Stability

Matthews works as a bus cleaner through Chicago Transit Authority’s Second Chance Program, which provides employment opportunities to individuals with barriers to work, including those with criminal records. The program offers paid, temporary positions with on-the-job training, mentorship, and access to support services, helping participants gain valuable work experience and a pathway to long-term employment. Just a few weeks shy of his graduation from the collective, he received an offer to make his position permanent.

Coach meetings have two main goals: advising residents on life skills, checking in about everyday challenges and connecting them with interview attire, therapy, etc. and financial advisory meetings to go over and track monthly budgets, savings plans and helping fill out things like apartment or food stamp applications.

Matthews credits the life coaching with helping him save enough money to purchase a car. “I can actually save money,” he said. “By me budgeting…I'm able to maintain and sustain stuff.”

Each floor of the house is available to everyone. Minea said the floors were designed intentionally, “you can feel the energy and interconnectedness of being able to use those different floors and meet folks and not just be isolated," he said, noting how important community is for residents. "Men, in their stuff that they're struggling through, definitely tend to isolate."

As residents reach their savings goals, and near the end of their time with the collective, coaches help apartmenthunt with them and team up with Chicago Furniture Bank to provide affordable furniture. Once the lease is signed, coaches then help them pack up and move them to their new place, “officially crossing the graduate finish line,” said Minea.

The finish line and what it means

Since being involved with Collective Chicago, Matthews saved $6,000. He is slated to complete probation in November. He moved into his first apartment on May 1, and he said it has been much harder with a record. “Anything that you apply for, and they check that background, and it comes up with something bad. It's an automatic ‘no.’”

He managed to get around that with the help of his attorney and coaches at the house, letting the landlord know his status, writing an appeal and providing an attorney letter.

Many of the men who come to the collective struggle with chronic homelessness, legal problems, mental disabilities or substance abuse issues.

McDowell, who has been with the collective for four years, said it’s hard for trauma-informed work to stick when the outside environment doesn’t allow for peace. He previously worked at READI Chicago as a trauma-informed facilitator.

“I experienced a wave of guys…who were looking for trauma-informed work, but their life couldn't reflect that. When they went into the world, their life didn't reflect the trauma-informed from work that we did there, and it felt like we were running into a dead end,” he said.

This disconnect between the healing work being done and the instability of the outside world is a challenge not just for READI, but for the collective as well. While staff are trained in trauma-informed care and strive to create safe, supportive environments, the impact of that work can be undermined when participants return to neighborhoods marked by violence, poverty, and systemic neglect. Oftentimes, these areas have the most affordable rent prices, a dilemma that grows as Chicago’s housing crisis rages on.

Minea believes the foundation Chicago Collective provides is key and an important first step to a broader change, “So any level of like, what's the complication, what's the obstacle?” translates to “Our system is broken…and I will do anything to give you the resources that you deserve and that are going to serve you and change your life forever.”

The bigger picture

M Nelsen, the manager of city policy at Chicago Coalition to End Homelessness (CCH) who leads the Homelessness Data Project, said that there are a number of local resources to address homelessness, such as the Continuum of Care (CoC) or Coordinated Entry System. Unlike Collective Chicago, however, many of them rely on state or federal funds and are confusing to people looking for help, they said.

Jordan Holmes, a life coach at Collective Chicago, said that while resources are out there for women and families, single men tend to fall through the cracks, “Usually the ages of 21ish to 24, a lot of programming and support and all types of things for grown men kind of disappear.”

In Chicago, that gap is evident. While a handful of transitional housing programs exist—such as A Safe Haven Foundation, which reserves 210 beds for single men, and Inner Voice’s Robert Johnson House—demand consistently exceeds supply. Other programs like Breakthrough Urban Ministries and Epworth Shelter for Single Men offer critical support, but collectively, these services fall short in meeting the needs of the city’s large population of single men facing homelessness or reentry after incarceration. This shortage makes the work of organizations like Collective Chicago vital in filling a void left by the broader system.

Left: Staff and residents meet inside Collective Chicago. Right: Collective Chicago team members Adam Gianforte, Co-Founder and CFO (left); Dominic Johnson, life coach (front & center); Dan Minea, Co-Founder and Executive Director (top & center); Tristion McDowell, Community Director and life coach (right). (Both photos courtesy of Collective Chicago).

“In most transitional housing models, you're not necessarily required to get your own lease, and so it provides access to something without having to do those while you can work on [mental, financial and physical health],” said Nelsen. “It can also provide a place to start to recover from some of the trauma, so that you can do those other things. It's an entry way into creating a foundation for stability in a lot of ways.”

Both Holmes and McDowell said that transitional housing programs can be life-changing for young Black men because it allows them to process traumas in a safe space.

“I think a lot of people of color don't think that places like this are for them, that these good things are for them,” said McDowell. “I think that being here and recognizing that there are people who will care about you, there are people who will watch you fail at something that you tried this hard at, and it doesn't mean it's the end of the world.”

“We have this commentary and narrative of, ‘guys should be better, or we should be able to do this in the world and/or the world should look different, or there should be more support services.’ When you ask where they are, sometimes you just hear crickets,” said Holmes.

Nelsen said part of why men often fall through the cracks is because many social services have a “perspective of charity,” in which young women and families are seen as more needing of help.

“We don't think about young Black men as people who deserve enough charity,” said Nelsen. “Racism causes young Black men, young men of color, to be targeted and dehumanized, right? When we dehumanize someone, we don't think that they need housing. We don't think that they deserve love.”

But how do they make the money make sense?

Collective Chicago estimates spending $15,000 for each resident who goes through the six-month program. Since its inception in 2018, Collective Chicago has helped 31 men reach long-term housing stability. During the twoyear period that the organization closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic and construction on a new building, Minea and Gianforte each took the remaining two residents into their home.

The cost of running the program is something Minea recognizes is a lot to get off the ground, citing that the $900,000 building they currently inhabit was donated.

“Quality solutions are expensive. That's a big amount to raise when you haven't even started.”

Minea explained that pulling together coaches, providing a space and partner services is “not easy to replicate” but when it all comes together, “it's the most cost-effective thing in the world.”

“I might only be able to help 14 [men] a year. But if this thing exists, it's 140 in 10 years. And that's 140 leaving with $6K each.”

The collective has three major corporate donors: Bank of America, Northern Trust and the Polk Bros. Foundation. Minea said that the collective strategically does not take government funding, “and as such bypasses the housing waitlist. This allows an ability to have faster turnaround between tenants, and help reduce the red tape for those in immediate need, as the waitlist and system has a variety of complications to supporting those in need in an efficient and effective manner.”

The collective works with over 50 partners across the city including Heartland Alliance, Chicago Therapy & Wellness, First Ascent and the CCH, who often give discounted rates for services and allow the young men to use them at no charge.

The collective also takes one-time and monthly individual donations ranging from $50 to $1,000, targeted toward interview attire or a year of therapy, for example. A monthly pledge also entitles donors to a hoodie, and potentially a Patagonia jacket. Funds go toward providing services for residents and pay for coaches, who work part-time for $28 an hour.

The collective’s Advocacy Board members have a required monthly donation of at least $100 and must invite 12 members of their network to “give generously” as well.

The organization also held its second annual March Madness fundraiser. Each $50 donation sponsors 1 month of bi-weekly therapy for a resident.

“You have to pay for expensive solutions if you want quality results and people, you can still put that $900K towards something else,” said Minea. It may not be as in-depth and may take longer, but start-up money shouldn’t be a barrier, he said.

What’s next

Collective Chicago’s next step is to expand to another building, replicating this approach in the area. “Eventually we want to turn this into a rent-to-own at the next building, so we can put all that equity back into the hands of the grads,” said Minea. The goal is not just to provide transitional housing, but to create long-term pathways to stability and ownership for participants.

Housing remains a central issue in reentry efforts. “People need housing solutions now. We don't have enough of it. We need more of it,” said Nelsen.

For those directly impacted, the need is urgent and personal. “There's a lot of people that's out here living with other people. They don't got no real foundation, or they having problems with budgeting," said Matthews. “I feel like there should be more organizations like this, because it's going to put people in a better position in life. Nobody in the world wants to keep seeing people down. They want to see people winning."

Left: Interior communal space at Collective Chicago. Center: The building's back yard. Right: Participants partake in sports and other communitybuilding activities nearby. (All photos courtsy of Collective Chicago).