STREET LIFE

An interdisciplinary urban studies course, analysing street life in Sydney and Phnom Penh

Built Environment

University of New South Wales

Sydney

Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism

Royal University of Fine Arts

Phnom Penh

Coordinators

Eva Lloyd

Giacomo Butte

Richard Briggs

Pen Sereypagna

www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com

e.lloyd@unsw.edu.au

STUDIES

2019/20

Street Life Studies

Context

Course overview

The course runs for one week in Sydney and two weeks in Phnom Penh, in January each year. Students work in interdisciplinary and intercultural groups to engage with the spaces, people and systems of the street.

New Colombo Plan Logo

In a moment of time when the balance between the public and the private is arguably shifting in favour of the latter, it is important that a close eye is kept on the status of public space in our cities. Vital and inclusive public space tends to emerge as a product of numerous competing forces. Attitudes, planning guidelines and levels of enforcement can strangle or let flourish the behaviours which can enliven these places so key to cities. The course is an opportunity to better understand the potentials and limitations of these diverse conditions.

The New Colombo Plan logo is a registered trademark and is legally protected.

Street Life Studies puts forward the premise that the vitality of public spaces hinges on their ability to facilitate a diversity of often unexpected usages, movements and interactions, by a broad spectrum of people, over varying time periods. It suggests that streets, as the public veins of the city, are where this activity can and should occur.

The logo is the primary, most easily recognisable image of the New Colombo Plan. The logo is comprised of:

• The New Colombo Plan logo

• New Colombo Plan written in full

New Colombo Plan Logo

Within this framework, the course suggests designers take an active role in engaging first hand with the complex layers of place throughout the design process. This intrinsically means an engagement not only with space but with the people who use it.

• The New Colombo Plan tag line: Connect to Australia’s future - study in the region.

White logo on the gradient background (prefered option)

Phase One: STREET LIFE OBSERVATION consists of students working in groups to undertake on-field analysis of urban streets in selected areas of Sydney and Phnom Penh. Using hand drawing and simple data collection techniques, students are guided through a series of observational exercises. They identify, document, and analyse the spaces, systems, users and usages of each street environment. The drivers behind spacio-behavioural patterns are interpreted as a way to begin to understand the needs of those who use the streets.

The logo is the primary, most easily recognisable image of the New Colombo Plan. The logo is comprised of:

• The New Colombo Plan logo

• New Colombo Plan written in full

The logo should be included on all external New Colombo Plan correspondence and documents, both printed and electronic.

• The New Colombo Plan tag line: Connect to Australia’s future - study in the region.

The course analyses two very different street environments; Lakemba in Sydney and Khan Daun Penh in Phnom Penh. These places hold in common both imminent change and clear expression of street life. Not without their challenges, Phnom Penh streets see diverse urban dwellers playing out much of their lives in the public domain. Street space is appropriated by its users in a ‘bottom-up’ manner to meet varying needs, rather than predominantly emerging as a result of those involved in the broader level design and legislation of the built environment. In Sydney, this kind of mixed informal activity is much less apparent. The physical street space itself is not dissimilar but usage tends to center upon vehicular and pedestrian circulation, and regulation of activity is significantly more controlled. The opportunities and constraints of each place can be understood through direct observation and comparison.

The New Colombo Plan logo is available in two variations:

• White and light blue for the use on the gradient and dark coloured backgrounds

on the gradient background (prefered option)

White logo on the gradient background with the Australian Government Crest

White logo on the gradient background with the Australian Government Crest

Phase Two: STREET LIFE INTERVENTION asks students to use their street observations as design ‘evidence’, to identify an urban challenge and inform an urban brief and intervention. Propositions act as urban acupuncture, scalable, and with the overall aim of fostering vital, people-centred public street space. The course encourages students to challenge their understanding of design intervention as purely physical and ‘provided’ by the designer or legislator. They are asked to imagine design systems and strategies developed with and by end users. Students consider how transcultural precedents might inform approaches across cities.

The logo should be included on all external New Colombo Plan correspondence and documents, both printed and electronic.

The New Colombo Plan logo is available in two variations:

• Reversed version of light blue for the use on light coloured backgrounds.

Partnerships

• White and light blue for the use on the gradient and dark coloured backgrounds

• Reversed version of light blue for the use on light coloured backgrounds

Light blue logo

The program has been built, and relies upon, ongoing relationships developed from 2010 between University of New South Wales Sydney (Built Environment), The Royal University of Fine Arts (Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism), Sa Sa

Light blue logo with the Australian Government Crest

Light blue logo with the Australian Government Crest

Art Projects, The Vann Molyvann Project, New Khmer - Architecture, and the people of Kahn Daun Penh and Lakemba. The program is funded through the Australian Government New Colombo Plan.

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 2

The New Colombo Plan logo is a registered trademark and is legally protected.

logo

Light blue logo White

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts,

Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 3

Phnom

Lakemba, sydney

khan Daun penh, phnom penh

lEARNING process

STREET OBSERVATION

"Direct observations help to understand why some spaces are used and others are not."

Gehl, J., & Svarre, B. (2013). How to study public life. Island press.

STREET INTERVENTION

"Construct situations rather than objects, design processes that can result in chance meetings ...leaving room for users to adapt and appropriate space."

Schneider, Tatjana, Till, Jeremy, 2016, Spatial Agency - Atelier Bow, https:// www.spatialagency.net/database/ where/social%20structures/atelier.

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 4

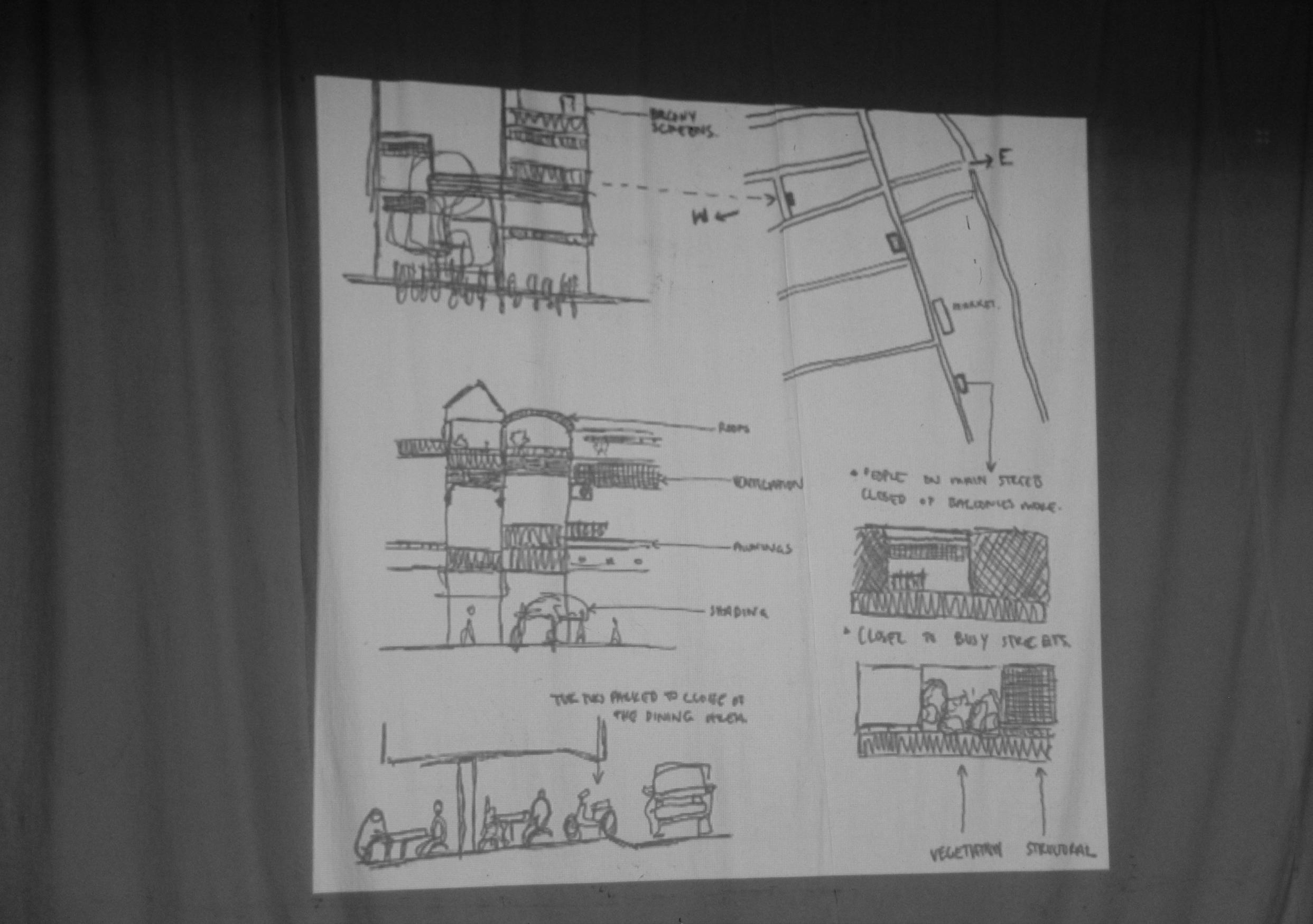

Diagram created by Eva Lloyd and Jayde Roberts, UNSW

research themes

The idea of urban vitality underpins student’s investigations of street life and is examined through the lens of a chosen sub-theme in small interdisciplinary and intercultural teams. This course draws on Adams and Tiesdell’s (2007) incremental description of vitality as, at one level, “simply being alive and able to survive”, and then, “the capacity not just to survive but to grow and develop”, and ultimately, “that mysterious, immaterial power that variously generates life, enables survival, produces growth, and gives health, energy and vigour.” In the context of the city, urban vitality can then be linked to the fostering of resilient, inclusive, convivial places that are a result of social structures, spatial arrangements, economic forces and governance . Exploring these facets across two cities, students examine diversities and commonalities in the emergence of urban vitality. Adams, D., & Tiesdell, S. (2007). Introduction to the special issue: The vital city. The Town Planning Review, 78(6), 671-679.

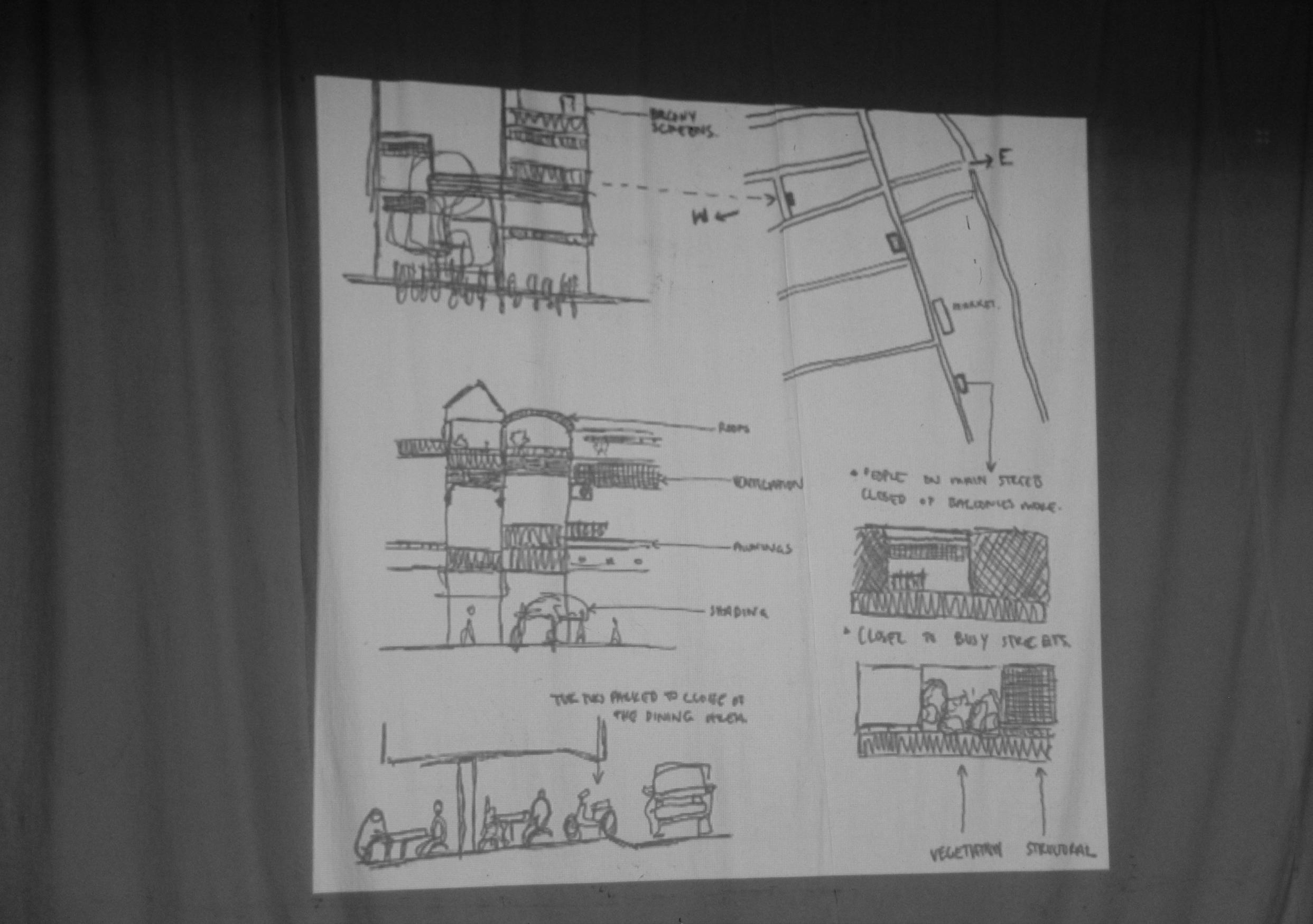

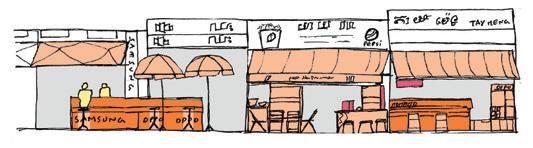

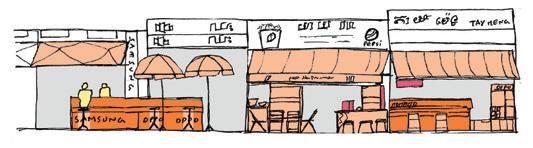

THEME 3 THE FACE OF THE CITY: FACADES

THEME 4 THE POROUS CITY: PRIVATE PUBLIC BUILDING THRESHOLDS

THEME 5 THE POROUS CITY: PRIVATE PUBLIC FENCE THRESHOLDS

Private public threshold

Vital streets encourage a level of ‘adaptability’ by their users. Users have an innate knowledge of their surrounds and are often the most effective 'designers' of the spaces they inhabit. Facades are an overt expression of this; their planned and unplanned manifestations often a strong contributor to the visual identity of a place. How can the 'base' components of a facade allow for adaptability by users?

Vital streets support interactions across the thresholds of private, interior space and public, exterior space. How can this boundary be re imagined to encourage a stronger relationship (be it direct or indirect) between internal and external users and activities.

DELIVERABLES x6 A5 observation cards for each city

OBSERVATION 1

OBSERVATION 2

OBSERVATION 3

Visual Card Data Card

Visual Card Data Card

Visual Card Data Card

Essential reading

The Slow City

1 Till, Jeremy. 'Architecture and Contingency.' 120. ISSN: 1755-068. www.field-journal.org. vol.1 (1)

2 Inara Nevskaya. 'Soft Dimensions' Volume Magazine n.33

3 'Edges and Paths' (pp 49-66) in: Lynch, Kevin. The Image of the City. Cambridge MA: MIT Press 1960

Encouraging longer stays

Essential reading

The Adaptable City

Essential reading

Fostering agency and identity

SCALE scales shown refer to drawing in sketchbook. final output scale (on A5 cards) may be smaller/larger.

1 Gehl, Jan; Johansen Kaefer, Lotte; Reigstad, Solveig, ‘Close encounters with buildings’. Urban Design International (2006) 11. Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. 2006

2 Paramita Atmodiwirjo, Yandi Andri Yatmo and Verarisa Anastasia Ujung. 'Outside Interior: Traversed boundaries in a Jakarta urban neighbourhood (pp 78-89) In: Atiwill, Susie. Urban+Interior. IDEA Journal ISSN 1445/5412. 2015

The Porous City

1 Maltby,Elliott+ Nandan, Gita. The Field Guide to Fences. Jan 2017 https://nextcity.org/features/view/nyc-field-guide-fences-public-space

SCALE

2 "Control architectures, Jittery enclaves, Passage point urbanism' (pp99-109) Graham, Stephen. Cities Under Seige. Verso. New York. 2011

Increasing threshold interactions

scales shown refer to drawing in sketchbook. final output scale (on A5 cards) may be smaller/larger. ensure clarity

The Inclusive City

3 Sperber, Elliot. 'The Concept of the Wall.' Roar Magaine. Issue 4. Nov 2017. https://roarmag.org/magazine/the-concept-of-the-wall/

OBSERVATION O1: THRESHOLD POROSITY

Focus points

· Modifications to original facade by users

Vital streets allow people to linger. Longer stays can contribute to streets that are a ‘hive’ of diverse activity. How can streets encourage a slowing down that broadens their purpose beyond circulation?

Field of view: facade full building height 2-3 buildings wide

Repeat in: Locations x3 (2-3 ‘units’ each)

Time frames x1

Show Layers: Planned

Focus points

· Proportion of porosity in GF façade

· ‘Level’ of porosity in each opening

· Drivers of porosity

· Internal building function (GF)

Vital streets allow adaptability by their users. Modifications made to facades often express the cultural identities of a place. How can the spatial componentry of facades foster these appropriations?

Field of view: int/ext thresholds windows or doors ground floor only commercial OR residential

in: Locations x3 (2-3 ‘units’/each)

OBSERVATION 1: FENCE POROSITY

Focus points

· Level of porosity

· Fence + human body

· Fence + building function

Vital streets prompt interactions between diverse users and activities. How can the urban-interior boundary be re-imagined to increase the frequency of such interactions?

Field of view: several fences in a row

Repeat in:

OUTPUT

Activating edges peripheries of space. In increasingly demarcation of space or blocking of

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. 5

Visual Card Data Card ENCOURAGING LONGER STAYS Longer 'hive' of broaden their excercise 03 _ images sidewalk movement _ 12 pm 03/ site 14 plan _ sidewalk movement _ 6 pm students staff others Nostrand York: internal areas of building or movement paths Data Card OBSERVATION 3 SCALE scales shown refer to drawing in sketchbook. final output scale (on A5 cards) may be smaller/larger. ensure clarity Sidewalk/Road Visual Card Data Card OUTPUT OBSERVATION O1: USER APPROPRIATIONS

?

Facade ZARAH BAITZ Z5016303 A N A C P R A D E D R N G T R E T Y D N E Y M O D C A O N S D A G R A M TV AERIALS CHANGE OF FACADE COLOUR GLAZING AWNINGS SUN SHADING SIGNAGE SECURITY BARS AWNING FOR SHADE FROM AFTERNOON SUN SUSPENDED SIGNAGE TO ATTRACT ATTENTION STRIPED COLOUR CHANGE ON FACADE TO CREATE IDENTITY AND STOP CUSTOMERS C M M AWNINGS SUN SHADING SIGNAGE AFTERNOON SIGNAGE TO ATTRACT STRIPED COLOUR CREATE IDENTITY AND DELIVERABLES: x6 A5 observation cards for each city Visual Card Data Card OBSERVATION 1 Visual Card Data Card OBSERVATION 2 Visual Card Data Card OBSERVATION 3

ensure clarity Visual Card Data Card OUTPUT

Repeat

Time frames x1

?

(2-3 fences/location)

frames x1

Layers: Planned Modified

public threshold

Locations x3

Time

Show

Private

?Vital streets support interactions across the thresholds of private and public space. In increasingly privatised societies how can the fence be reimagined to support activities beyond the blocking of access?

: x6 A5 observation cards for each city Visual Card Data Card OBSERVATION 1 Visual Card Data Card OBSERVATION 2 Visual Card Data Card OBSERVATION 3

scales shown refer to drawing in sketchbook. final output scale (on A5 cards) may be smaller/larger. ensure clarity Building threshold

DELIVERABLES

SCALE

Facade

Sidewalk Fence

street life explores...

Dynamic relationships between:

The environment, people, their behaviour, their stories

The formal and informal systems of place (acknowledging these are non-binary)

Space, culture, politics, economics

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20.

www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 6

Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh.

policy context

Enabling Delivery of Our Strategy

28 D1: People and culture

29 D2: Operational effectiveness and sustainability

30 D3: World-class environments

Next steps

11.3 By 2030, enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management in all countries

11.4 Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage

11.7 By 2030, provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces, in particular for women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities

11.7.1 Average share of the built-up area of cities that is open space for public use for all, by sex, age and persons with disabilities

NEW URBAN AGENDA

37. We commit ourselves to promoting safe, inclusive, accessible, green and quality public spaces, including streets, sidewalks and cycling lanes, squares, waterfront areas, gardens and parks, that are multifunctional areas for social interaction and inclusion, human health and well-being, economic exchange and cultural expression and dialogue among a wide diversity of people and cultures, and that are designed and managed to ensure human development and build peaceful, inclusive and participatory societies, as well as to promote living together, connectivity and social inclusion.

PHNOM PENH SUSTAINABLE CITY PLAN 2018-2030

ANNEX B: SUSTAINABLE CITY DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS*

1. The detailed land-use and zoning plan for the Daun Penh District will protect streetscapes, building stock and public areas of critical importance to the identity of the city. It will improve the livability and functionality of the area and increase its attractiveness to residents and visitors alike.

(to be read in conjunction with the Phnom Penh Master Plan for Land Use 2035)

17.

Air Pollution

The creation of a walkable and bike friendly urban setting with public transportation modes and green public spaces, can help to increase the health and wellbeing of urban dwellers.

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 7

2 03 04 06 07 08 10 11 12 17 23 27 31 From the Chancellor From the President and Vice-Chancellor UNSW Vision UNSW 2025 Our Commitment Our Strategy in Context The UNSW Strategic Matrix Strategic Priorities Strategic Priority A: Academic Excellence 13 A1: Research quality – a world leader 15 A2: Educational Excellence - The UNSW Scientia Educational Experience Strategic Priority B: Social Engagement 18 B1: A just society 20 B2: Leading the debate on Grand Challenges 21 B3: Knowledge exchange for social progress and economic prosperity Strategic Priority C: Global Impact 24 C1: UNSW model of internationally engaged education 25 C2: Partnerships that facilitate our strategy 26 C3: Our contribution to disadvantaged and marginalised communities

www.habitat3.org #NewUrbanAgenda #Habitat3

the course focuses on:

place-based immersion

Fedesco, Cavin and Henares (2020, p.76) describe place-based immersion as fitting within a constructivist learning paradigm that involves “being deeply involved with the place for an extended period of time and absorbing all the nuances of interconnectedness that exists in the area”.

Fedesco, H. N., Cavin, D., & Henares, R. (2020). Field-Based Learning in Higher Education: Exploring the Benefits and Possibilities. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 20(1), 65-84.

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 8

learn about the street, in the street

Experiential learning is core to the program, occurring through daily observational tasks based directly in urban streets. Public street space acts as a laboratory for social investigation (Hubbard & Lyon, 2019), drawing on Lefebvre’s (2004) ideas of the street as an inherently social production, brimming with complexities and contradictions.

Field-based pedagogies, when compared to ‘pure’ classroom learning have been shown to increase not only motivation but skills in critical inquiry, knowledge building and cooperative learning (Nugent et al., 2008). When positioned early in a student’s career, field experiences can be transformative, leading to future career paths (Hutson, Cooper, & Talbert, 2011).

Lefebvre, H. (2004). Rhythmanalysis: Space, time and everyday life. A&C Black.

Hubbard, P., & Lyon, D. (2018). Introduction: Street life–the shifting sociologies of the street. The Sociological Review, 66(5), 937-951.

Hutson, T., Cooper, S., & Talbert, T. (2011). Describing connections between science content and future careers: Implementing Texas curriculum for rural atrisk high school students using purposefully-designed field trips. Rural Educator, 33, 37-47.

Nugent, G., Kunz, G., Levy, R., Harwood, D., Carlson, D., (2008), ‘The Impact of a Field-Based, Inquiry-Focused Model of Instruction on Preservice Teachers’ Science Learning and Attitudes’, Electronic Journal for Research in Science & Mathematics Education (EJRSME), Vol 20, No. 2, 2.

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South

Architecture and

University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 9

Wales, Sydney.

Urbanism, Royal

look and listen over proposition

Understanding of place through on-field observation and listening is the core focus of the program. This questions pedagogical approaches in architectural education that prioritise design proposition. Through ethnographic research methods, students observe street environments over extended time periods and engage directly with street users. The International Federation of Red Cross/ Red Crescent Societies describes this as a people-centred approach key to building resilience, “listening to and understanding what people think at all times, rather than imposing ideas or projects on them” (IFRC, 2016, p14).

International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Road Map to Community Resilience (2016), https://media.ifrc.org/ifrc/wp-content/uploads/si tes/5/2018/03/1310403-Road-Map-to-Community-Resilience-Final-Version_EN08.pdf).

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 10

examine ‘Everyday resilience’

(Hawken,

Sunindijo,Sanderson, 2020)

Students investigate ‘everyday’ challenges faced by street users and the ‘bottom-up’ mechanisms employed to cope with often dynamic contingencies. Such adaptive mechanisms are often described as fitting within the realm of urban informality however this course aims to examine formality/informality as non-binary and interconnected. In “the domain of lived experience, everyday struggle, routine, and organisation, the informal does not exist in isolation from the formal city: they are blurred” (Simone 2005). Schröder and Waibel (2012) discuss how informality can contribute to formal institutions “by organising social interaction in the absence of the state... for example, during rapid urban development”. Given the short timeframe of this course, the major focus is on physical, “place-based adaptations” (Hawken, Sunindijo, Sanderson, 2020) that tend to be more explicit through field observation and short dialogue. Students employ bottom-up, local scale ways of understanding (Hamdi 2004) and their observations of the street environment have highlighted categories of place-based adaptations as tending to be: economically driven (supporting livelihood), socially driven (supporting peoplepeople relationships), culturally driven (supporting self and collective identity), climatically driven (protection from environmental exposure), and security driven (protection from crime-based activity).

Hamdi, N. (2004), “Small change”, About the Art of Practice and the Limits of Planning in Cities, Earthscan, London.

Hawken, S., Sunindijo, R. Y., & Sanderson, D. (2020). Narratives of everyday resilience: lessons from an urban kampung community in Surabaya, Indonesia. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment.

Simone, A. 2008. The politics of the possible: making urban life in Phnom Penh. Journal of Tropical Geography, 29, 186-204.

Schröder, F. and Waibel M. (2012) Urban Governance and Informality in China: Investigating Economic Restructuring in Guangzhou. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie, 56(1/2), 97-112.

SOURCE: AESTA1, HTTPS://WWW.GOGLOBALTODAY.COM/THE-STREETS-OF-PHNOM-PENH.HTML

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 11

students as investigators

A student-centred and research-based educational environment provides learners the reigns as primary investigators (Healey, 2005, Beckmann, Weber, Whitehead, Nicotra, 2017). Students identify research questions and data collection methods under a series of broad themes, exercises and geographic locations. Crucially, these questions and methods emerge and evolve through ongoing field observation and user engagement. Students analyse and visualise their findings, working in teams to determine relationships between their observations. They then present a collective body of work to peer groups and tutors.

Beckmann, B., Weber, X., Whitehead, M., Nicotra, A. (2017) ‘Research-based learning: Designing the course behind the research’, Ch14, in Zurcher, H., Chia Ming-Dao, C., Whitehead, M., Nicotra, A. (Eds), ‘Researching functional ecology in Kosciuszko National Park’, 141-151, , ANU eView, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia. dx.doi.org/10.22459/RFEKNP.11.2017.14 ANU eView

Healey, M (2005) Linking research and teaching: Exploring disciplinary spaces and the role of inquiry-based learning. In Barnett, R (ed.), Reshaping the University: New relationships between research, scholarship and teaching, pp. 67–78. Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press, Maidenhead.

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 12

draw, to engage with place

Hand drawing on the field is employed as a powerful cognitive tool for analysis of place, allowing deepened interpretation and embedding in one’s memory through simultaneous visual, kinesthetic and semantic learning (Fernandes, Wammes, Meade, 2018).

Fernandes MA, Wammes JD, Meade ME. (2018). ‘The Surprisingly Powerful Influence of Drawing on Memory. Current Directions in Psychological Science.’2 7(5):302-308. doi:10.1177/0963721418755385

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 13

compare cities, examine interconnectivities

The opportunity to connect learning across global locations allows students to understand diverse patterns of urban development and to “acquire knowledge and understanding of local, national and global issues and the interconnectedness and interdependency of different countries and populations” (UNESCO, 2015, p.31). The UNESCO Global Citizenship Education framework describes this as falling within cognitive learning and emphasises the importance of integrating this with socio-emotional and behavioural learning.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, ‘Global citizenship education: topics and learning objectives’ (2015), https://unesdoc. unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000232993

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment,

www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 14

University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh.

learn iteratively,

begin with the familiar

The program aims to improve students’ ability to engage with new place-based contexts. The course scaffolds learning, repeats tasks and begins with that which is familiar (these techniques are complimented by approaches to building cultural responsiveness). Observational research tasks are introduced and trialled in the classroom setting. They are then implemented on-field in the ‘home’ location (Lakemba, Sydney) and then again in the ‘host’ location (Kahn Daun Penh, Phnom Penh). Through this structure, students iteratively practice and develop their skills as scaffolds ‘fade’ (Taber, 2018). Students demonstrate an evolving ability to grapple with the rich complexities of place and to self-direct their research.

Taber, K. S. (2018). Scaffolding learning: principles for effective teaching and the design of classroom resources. In M. Abend (Ed.), Effective Teaching and Learning: Perspectives, strategies and implementation (pp. 1-43). New York: Nova Science Publishers.

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 15

“The dance around world view”

(Nakata, Nakata, Keech and Bolt, 2012)

Concepts of cultural literacy are introduced, however rather than fixed ‘knowns’ about a particular culture, students are introduced to the process-based concept of cultural responsivity (Halbert and Chigeza, 2015). Klump and McNeir (2005) emphasise the dynamic nature of the term responsivitity, requiring acknowledgement of unique situations, the need to take action to address these and the importance of adaptation as situations change over time. Muller (2006) describes globally literate citizens as possessing ‘informed tentativeness’ over defined cultural knowledge. In turn, in this program, students study both culture and urban place-making through relational systems thinking. It is argued that both culture and the urban realm are in a constant state of flux, and both require an engagement with complexity and interconnectivity. In practice this means students are asked to explore meaning in situations encountered, to investigate and create processes over end-products, and to be flexible in their conceptions of self and peer identity in collaborative work.

Halbert, K., & Chigeza, P. (2015). Navigating discourses of cultural literacy in teacher education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education (Online), 40(11), 155.

Klump, J., & McNeir, G. (2005). Culturally responsive practices for student success: A regional sampler. Retrieved February 12, 2021, from www.nwrel.org/ request/2005june/textonly.html

Muller, W. (2006). The contribution of ‘cultural literacy’ to the ‘globally engaged curriculum’and the ‘globally engaged citizen’. Social Educator, 24(2), 13-15.

Nakata, N. M., Nakata, V., Keech, S., & Bolt, R. (2012). Decolonial goals and pedagogies for Indigenous Studies. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education and Society, 1(1), 120–140.

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 16

build relationships exchange knowledge

The program is cognisant of the history of colonisercolonised power dynamics in the Global South and the educational structures that can sustain these ways of knowing and operating (Martin & Pirbhai-Illich, 2015). Aiming to ‘solve’ perceived urban challenges or ‘save’ those perceived to be in need are not the aims of the course. Rather, students are introduced to the “cumulative nature of design and planning” that “highlights relationship building rather than merely goal accomplishment” (Hou, 2007). As such, although the content of the course focuses on ways of understanding, and ultimately improving, the way public streets develop, the processes of knowledge exchange and relationship building through which this occurs are of equal priority in learning tasks. It is also intentional that in this two week course, students engage with public street spaces and the lived experience of their peers, as opposed to a more direct relationship with a particular community group. Such community-based ‘service-learning’ courses often benefit the academic institution more than the partner community, Martin & Pirbhai-Illich (2015) argue such courses can inadvertently perpetuate the server-recipient/ us-them relationship due to students’ lack of understanding of the socio-historical factors that establish inequities.

Hou, J. (2007). Community processes: The catalytic agency of service learning studio. Design studio pedagogy: Horizons for the future, 285-294.

Martin, F., & Pirbhai-Illich, F. (2015). Service learning as post-colonial discourse: Active global citizenship. In Contesting and constructing international perspectives in global education (pp. 133-150). Brill Sense.

Thamrin, D., Wardani, L. K., Sitindjak, R. H. I., & Natadjaja, L. (2019). Experiential Learning through Community Co‐design in Interior Design Pedagogy. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 38(2), 461-477.

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 17

co-create, interdisciplinary + intercultural

Students are prompted to act in ‘joined-up’ ways to better address the types of wicked 21st century challenges of society and nature (Jones and Wingfield, 2010) that they witness first hand in urban streets. Exchanging and synthesising ideas in diverse teams builds collective knowledge and develops skills in deconstructing fixed notions of identity; disciplinary, cultural, behavioural, self and ‘other’. This approach draws on theories of metadesign that Jones and Wingfield (2010) describe as a design process that transcends specialist boundaries and emphasises emergent systems thinking. McCarthur (2018) argues for augmenting this with transcultural pedagogical practice that equips students to operate in interconnected global contexts. Leveraging social identity theory, Hughes (2010) asserts that teams may work more effectively if a sense of group identity is established, and that allowing fluidity in individual identity may allow team members to experience a greater sense of belonging to the group.

Hughes, G. (2010). Identity and belonging in social learning groups: the importance of distinguishing social, operational and knowledge‐related identity congruence. British Educational Research Journal, 36(1), 47-63.

Jones, H., & Wingfield, R. (2010). MetaboliCity: How can metadesign support the cultivation of place in the city?

McArthur, I., Priestman, M., Miller, B., (2018), ‘Collaborative mapping as a new urban design pedagogy’, in McArthur, W., Xu, F., Miller, B., (Eds). ‘Investigating the Visual as a Transformative Pedagogy in the Asia Region’, (p.121-150), Champaign, IL: Common Ground Research Networks.

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 18

connect with local urban actors

Students interact with local urban actors to translate the learnings from their more ‘simulated’ research projects to ‘live’ development sector work taking place in Cambodia. These actors play a dual role as both guest speakers and teaching staff, exposing students to the roles of not for profit community groups and international non-governmental organisations. The goal here is to leverage the impact of connection to a professional context in the ‘real’ world to trigger a more transformative educational experience.

Oliver, B. (2015). Redefining graduate employability and work-integrated learning: Proposals for effective higher education in disrupted economies. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 6 (1), 56-65.

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 19

explore participatory methods through exhibit

The course closes with an exhibition that exposes students work to an audience beyond their peers and tutors and invites public interaction with a series of research-based artefacts. This approach continues to expose students to participative methodologies, shifting he role of the audience from passive viewer to active contributor. Bjerregaard (2019) argues that we re-imagine exhibitions as “knowledge-in-the-making rather than platforms for disseminating already-established insights”.

Bjerregaard, P. (Ed.). (2019). Exhibitions as Research: Experimental Methods in Museums. Routledge.

Richards, N. (2011). Using participatory visual methods. TRealities, Morgan Centre, Sociology, University of Manchester. Accessed 12 February 2021. https:// hummedia.manchester.ac.uk/schools/soss/morgancentre/toolkits/17-toolkit-participatory-visual-methods.pdf

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and

University of

Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 20

Urbanism, Royal

Fine Arts, Phnom

extend learning through internship

Students are able to deepen their learning through a month-long group-based Professional Placement program working on a participative community development project in Phnom Penh. The program aims for a ‘critical service learning’ (Rhoads 1997) approach ‘that not only attempts to meet the needs of a particular community’ (Martin & Pirbhai-Illich, 2015, p.2) but also addresses issues at the root of social inequities through a social awareness lens (Ginwright and Cammarota, 2002). Having developed knowledge and sensitivities through the Street Life Studies course, students enter the professional placement program more equipped to appreciate the wider social and political contexts framing and impacting upon their work. Students partner with interdisciplinary organisations involved with systemic change, and an ‘urban talks’ series throughout the program offers diverse cross sectoral perspectives on issues at the core of project work. These authentic, in-situ connections offer the opportunity for reflexive learning, critical consciousness and engagement in ongoing advocacy (Mitchell, 2008, Martin & Pirbhai-Illich, 2015).

Ginwright, S., & Cammarota, J. (2002). New terrain in youth development: The promise of a social justice approach. Social justice, 29(4 (90), 82-95.

Mitchell, T. D. (2008). Traditional vs. critical service-learning: Engaging the literature to differentiate two models. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 14(2), 50-65.

Rhoads, R. A. (1997). Community service and higher learning: Explorations of the caring self. SUNY Press.

Thamrin, D., Wardani, L. K., Sitindjak, R. H. I., & Natadjaja, L. (2019). Experiential Learning through Community Co‐design in Interior Design Pedagogy. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 38(2), 461-477.

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 21

SA SA ART PROJECTS + NEW KHMER-ARCHITECTURE

HABITAT FOR HUMANITY CAMBODIA

create an ecosystem

Now in it’s sixth year, the Cambodia program continues to evolve in an organic manner through investment in long-term relationships that practice collective knowledge building, value reciprocity, exercise flexibility and are underpinned by trust. Pedagogically speaking, this ecosystem provides an authentic WIL (work integrated learning) landscape for students. They witness first hand, and become a part of, a global collaboration that spans government, civil society, academia, and private sector across Australia and Cambodia. Importantly, students dip their toes into the navigation of what is at times a ‘messy’, complex and evolving system of relationships that reflects the very nature of 21st century collaboration.

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 22

course work

Phase 1: Street life Observations

Phase 2: Street life Interventions

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 23

phase 1: street life observation

Phase one of the course asks students to undertake on-field analysis of urban streets in selected areas of Sydney and Phnom Penh. In interdisciplinary groups, students examine streets and the life they host through the lens of a chosen theme; slow cities, adaptable cities, porous cities or inclusive cities.

Through a series of observation and interview exercises, students use hand drawing and data collection to identify and deconstruct the physical, behavioural and systemic layers of each street environment. They interpret key patterns to consider the driving forces behind their findings and then communicate these using basic data visualisation techniques.

"Streets and their sidewalks-the main public places of a city-are its most vital organs."

Jane Jacobs (2016). “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”, p.27, Vintage

“While architects and urban planners have been dealing with space, the other side of the coin – life – has often been forgotten.”

Gehl, J., & Svarre, B. (2013). How to study public life. Island press.

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 24

phase 2: street life intervention

Phase two of the course asks students use their findings as ‘evidence’ to develop a design brief and proposal for an urban intervention, in either Sydney or Phnom Penh. The goal is to create a small scale, yet scalable, intervention that acts as a social catalyst, supporting or improving street life.

Students are challenged to think beyond the paradigm of design intervention as a physical construct ‘delivered’ to the end user by the creative professional. They are encouraged to consider adaptive systems developed and maintained with and by the people who will ultimately use them. The comparison of cities in the observational phase of the course becomes a means by which students may draw on ‘real world’ precedents and reinterpret these within new socio-spatial contexts.

Students unpack the findings of their observations and interviews through team workshops. They reflect on their collective findings to identify opportunities and constraints that lead to the development of a series of inquiry-based open-ended design briefs. Students then develop a response to their brief, presented through public presentation and exhibition.

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 25

"Construct situations rather than objects, design processes that can result in chance meetings ...leaving room for users to adapt and appropriate space."

Schneider, Tatjana, Till, Jeremy, 2016, Spatial Agency - Atelier Bow, https://www.spatialagency.net/database/where/social%20structures/atelier.

CAN THE ‘OBJECTS’ OF INFORMAL ECONOMIES ACT AS SOCIAL HUBS?

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 26

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 27 How is a street food cooler box used over a day? A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A COOLER Preparing the shop | 7AM | St. 154 Lady buying a drink | 9AM | St. 154 No activity | 11AM | St. 154 Resting | 2PM | St. 154 Chatting | 4PM | St. 154 Having lunch | 12PM | St. 154 Preparing dinner | 6PM | St. 154 Close | 10PM | St. 154 Walking pass | 5PM | St. 154 PHNOM PENH, RATANAKVISAL OUM OBSERVATION

planned modified activities users OBSERVATION

CONCLUSIONS

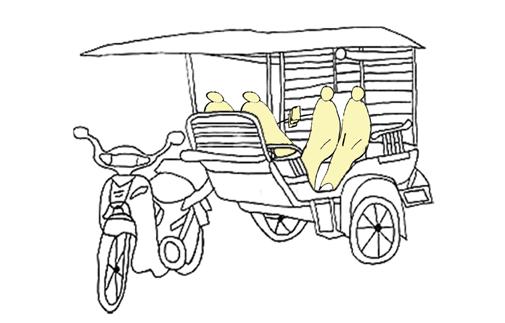

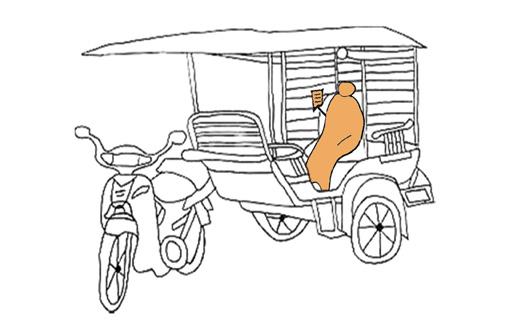

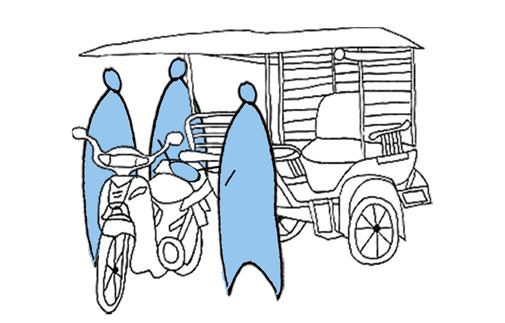

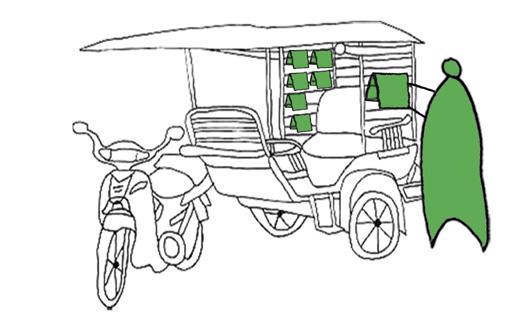

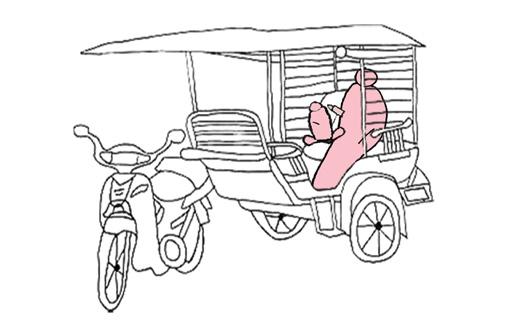

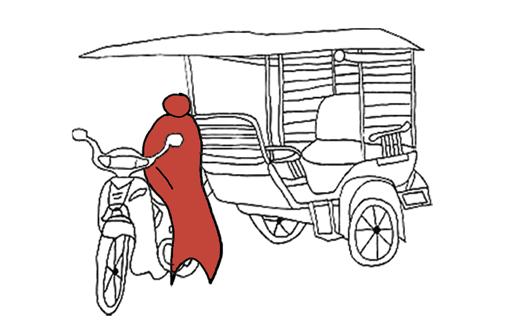

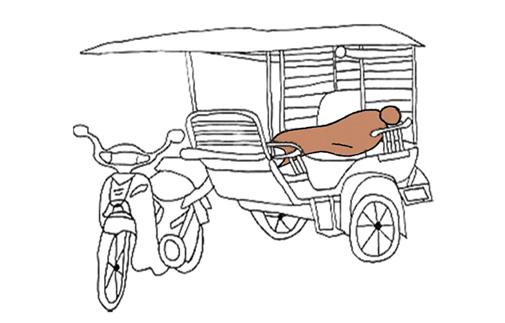

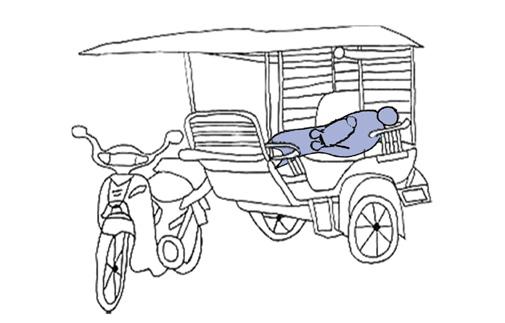

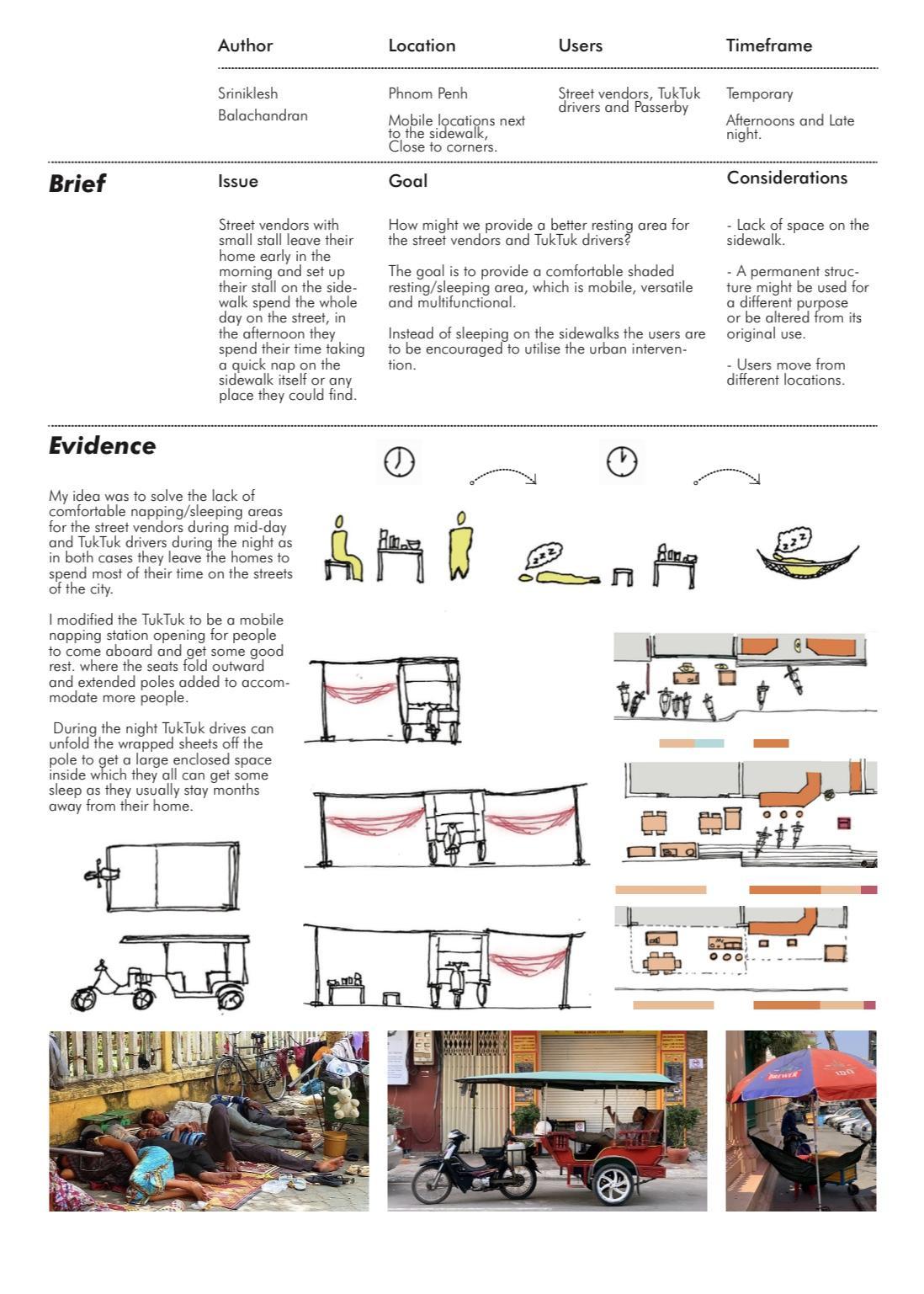

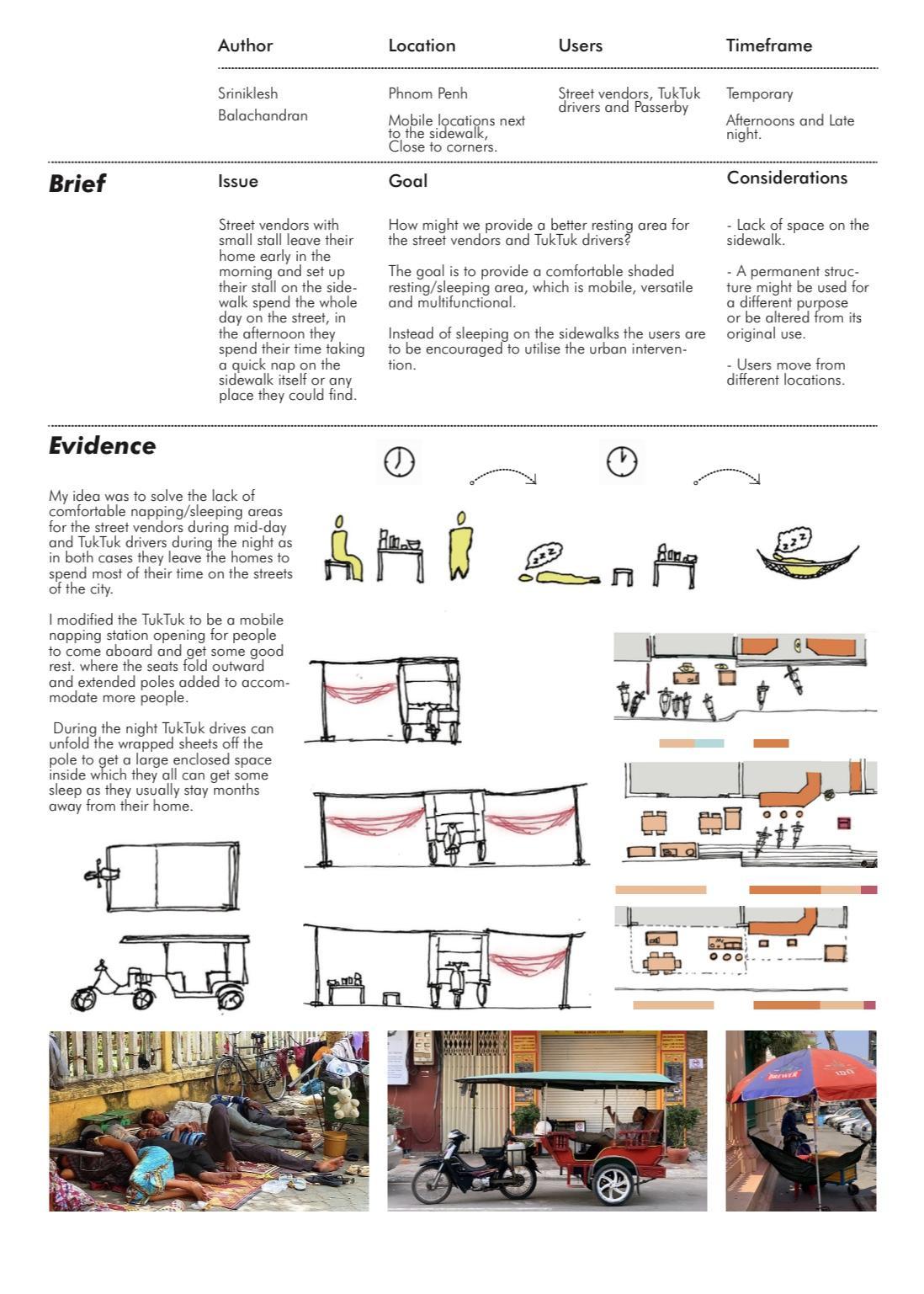

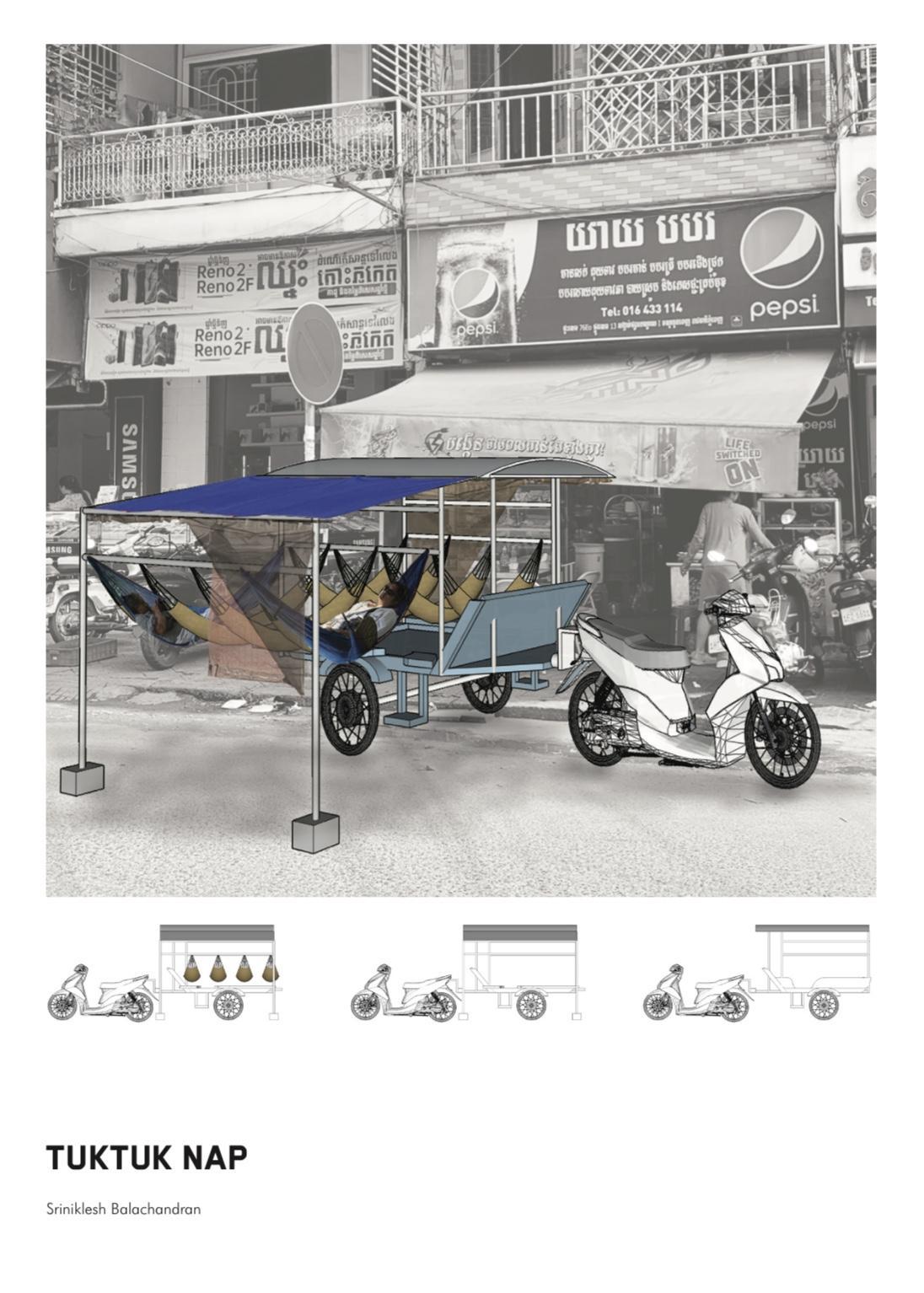

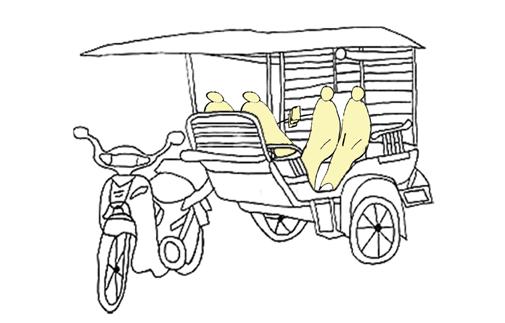

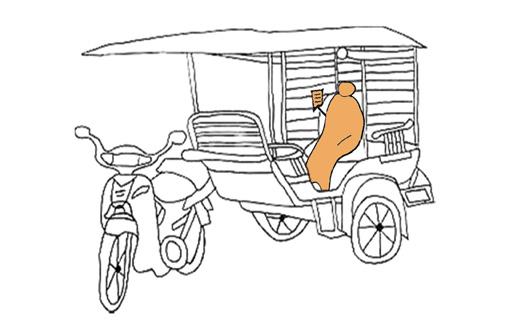

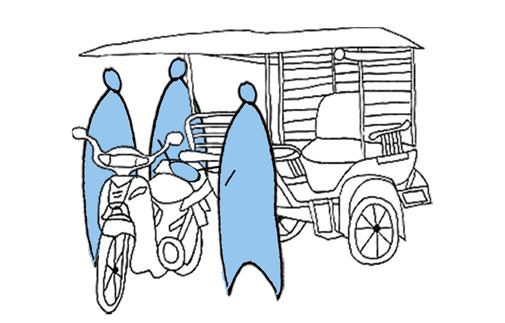

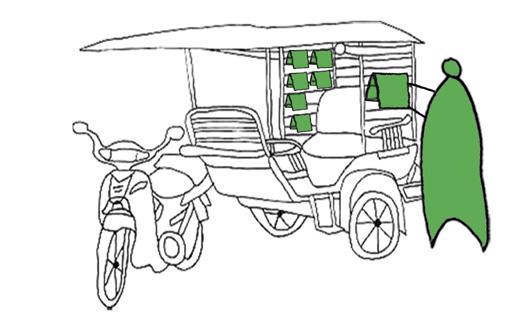

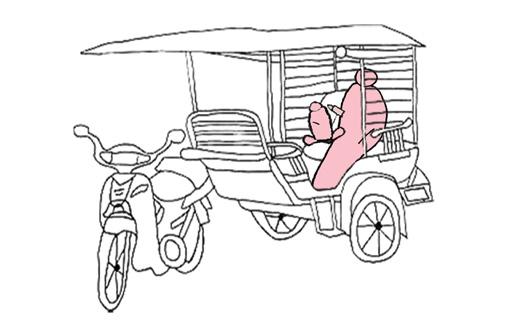

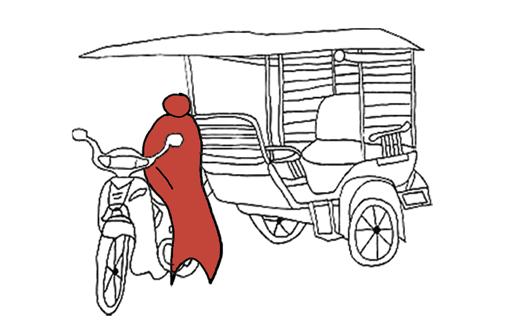

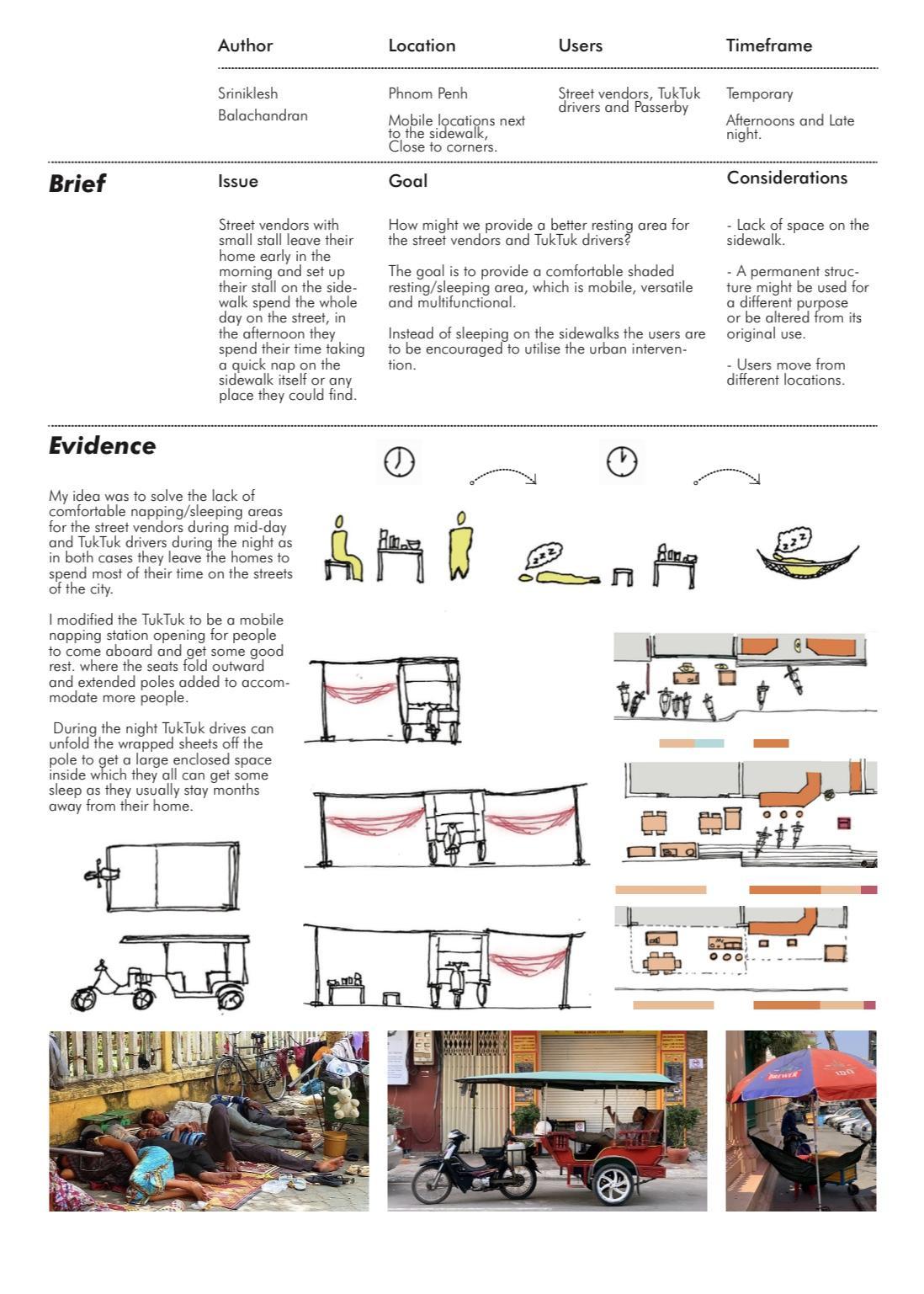

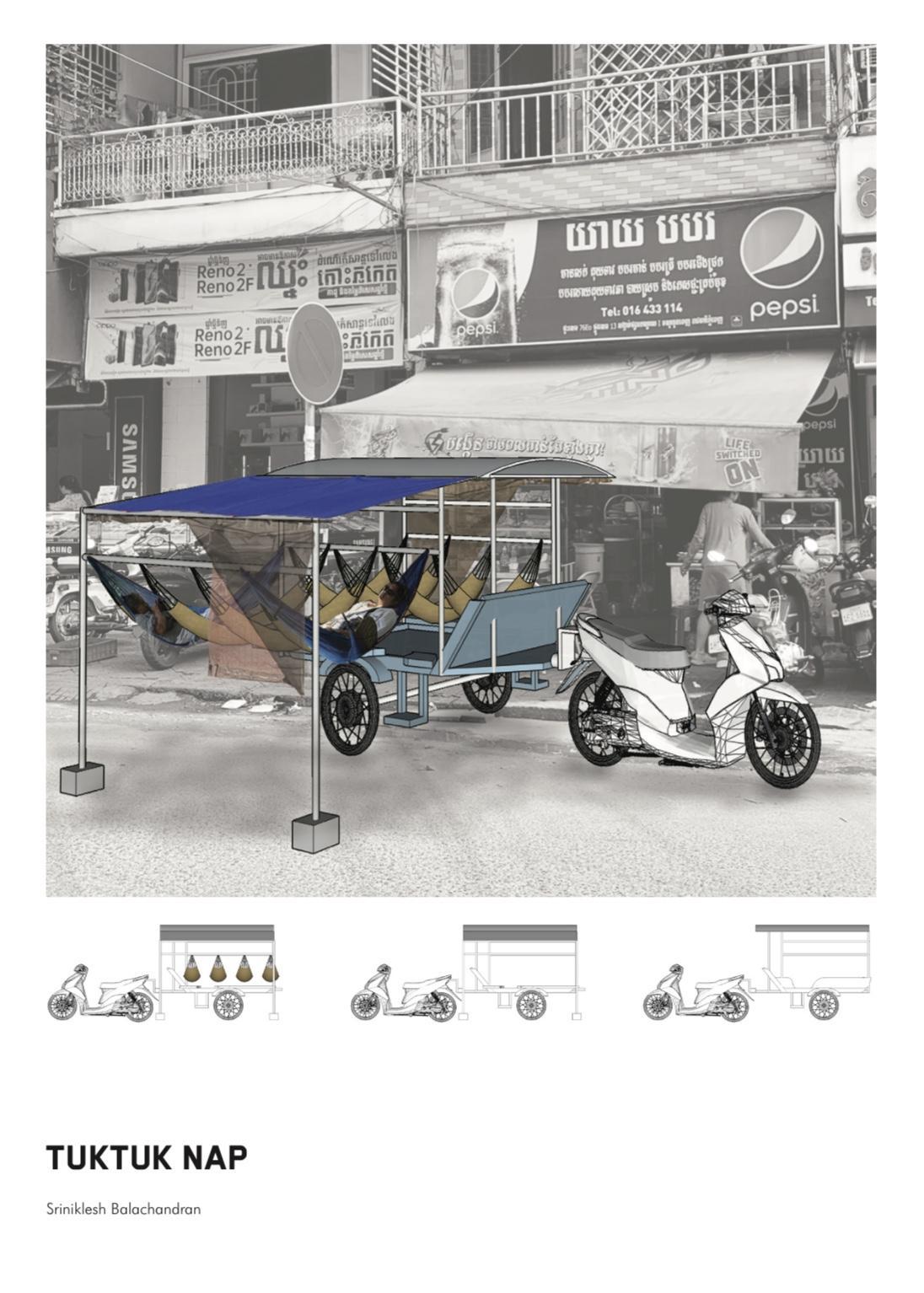

Tuk Tuk’s can be seen everywhere throughout Phnom Penh at all times of the day. The range of activities and users these motor vehicles attract ranges deeply on external factors such as where they are parked and whether they are in shade or are just relying on the fixed sheltered roof.

This particular observation looks at stationary tuk tuk’s around the city and how they allow users to create new experiences. I believe that moving around the streets in a stationary tuk tuk allows you to gather what is going on outside and provide you with views of the street life. It is a notion that Jan Gehl touches on as she expresses ‘a place to sit must have a good view of surrounding activities as they will be used more than seating with no view’.

INFOGRAPHIC

City Sleeping With Child | 6am | Waiting for Customer | 8am | Feeding Child | 10am | Hanging Laundry | 2pm | Browsing Phone | 4pm | Sleeping | 12pm | Eating In A Group | 8pm | Playing Cards | 10pm | Eating Individually | 6pm |

City Sleeping With Child | 6am | Waiting for Customer | 8am | Feeding Child | 10am | Hanging Laundry | 2pm | Browsing Phone | 4pm | Sleeping | 12pm | Eating In A Group | 8pm | Playing Cards | 10pm | Eating Individually | 6pm |

In my infographic, I gathered results three different times of the day by going on a 2km walk each period and recording how many times I saw certain activities occur. I focused on the main activities I initially observed to see how common these really were in the city of Phnom Penh.

sidewalk facade building threshold fence threshold Comparing Tuk Tuk Activity Throughout the Day Based on 2km distance.

What activities do informal transport systems host other than transport?

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 28

PENH, DANIELA

Focus area

PHNOM

NOVAKOVIC

Author Daniela Novakovic Phnom Penh A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A TUK TUK

How might tuk tuks offer a place to sleep for those in need?

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts,

Phnom Penh.

Niklesh NikleshNiklesh

‘TUK TUK NAP’, PHNOM PENH, SRINIKLESH BALACHANDRAN

INTERVENTION

CAN FENCES BECOME PLACES TO GATHER...?

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 30

Phnom penh Yan ZHANG

CONCLUSIONS

INFOGRAPHIC

The materials affect the way how to apply things on it such as a tie, droving, weld and lean, and the combination with the way of connection influences human activities. Connections are different due to material variety and building functions. for example, Droving can be used on stone, but it can not be applied to the temple because it would break the pattern and the importance of the temple.

CONCLUSIONS

The way of tie up is more common in the stone and metal fence, which produce a series of activities such as hanging cloth for sundry, tied up tent creating eating area.

Ribus, quis eos ni aliquat ibusapiciam, sitas quam cum et eum dunde pos esto dolupta earum seque quatur? Qui dolest eostem hario mi, conseque prehenisci tem elestotas perepti ratatus, omnimpe rspient rempossime non eum, sinctemquis dolum sit volorepro maximagnis sunt que ni iuntota tquae. Ut quamus, offici dolupitio voloria comniss iminus re earchitassit volorae pedigen tendiandis ea est res as suntiation periae mod most utecat. iuntota tquae. Ut quamus, offici dolupitio voloria comniss iminus re earchitassit volorae pedigen tendiandis ea est res as suntiation periae mod most utecat. Ribus, quis eos ni aliquat ibusapiciam, sitas quam cum et eum dunde pos esto dolupta earum seque quatur? Qui dolest eostem hario mi, conseque prehenisci tem elestotas perepti ratatus, omnimpe rspient rempossime non eum, sinctemquis dolum sit volorepro maximagnis sunt que ni iuntota tquae. Ut quamus, offici dolupitio voloria comniss iminus re earchitassit volorae pedigen tendiandis ea est res as suntiation periae mod most utecat. iuntota tquae.

Droving is the special way for a brick fence, because of it’s solid so that anything can be fixed in and the human activities changes with the thing in it

The materials affect the way how to apply things on it such as a tie, droving, weld and lean, and the combination with the way of connection in nections are di and building functions. for example, Droving can be used on stone, but it can not be applied to the temple because it would break the pattern and the importance of the temple.

The way of tie up is more common in the stone and metal fence, which produce a series of activities such as hanging cloth for sundry, tied up tent creating eating area.

Ribus, quis eos ni aliquat ibusapiciam, sitas quam cum et eum dunde pos esto dolupta earum seque quatur? Qui dolest eostem hario mi, conseque prehenisci tem elestotas perepti ratatus, omnimpe rspient rempossime non eum, sinctemquis dolum sit volorepro maximagnis sunt que ni iuntota tquae. Ut quamus, o dolupitio voloria comniss iminus re earchitassit volorae pedigen tendiandis ea est res as suntia tion periae mod most utecat. iuntota tquae. Ut quamus, o earchitassit volorae pedigen tendiandis ea est res as suntiation periae mod most utecat. Ribus, quis eos ni aliquat ibusapiciam, sitas quam cum et eum dunde pos esto dolupta earum seque quatur? Qui dolest eostem hario mi, con seque prehenisci tem elestotas perepti ratatus, omnimpe rspient rempossime non eum, sinctem quis dolum sit volorepro maximagnis sunt que ni iuntota tquae. Ut quamus, o comniss iminus re earchitassit volorae pedigen tendiandis ea est res as suntiation periae mod most utecat. iuntota tquae.

Droving is the special way for a brick fence, because of it’s solid so that anything can be fixed in and the human activities changes with the thing in it

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 31 What street activities are afforded through small-scale fence details? PHNOM PENH, YAN ZHANG OBSERVATION TITLE Item 1 Item 2 Item 3 Item 4 Item 5 Combined Elevation & Modified elements Section & activities -viewing / hanging / dining Section & activities -urinate / setting / dining Combined Elevation & Modified elements Combined Elevation & Modified elements OBSERVATION 2 FENCE ACTIVITY Stone Activities connection Elements Brick Metal Tie up Tie up Drove Weld Layers Focus area Author sidewalk facade building threshold fence threshold planned modified activities users

City

INFOGRAPHIC

Lean Dining Dining hangViewing Dining Pee Put things Stone Activities connection methods Brick Metal Item 1 Item 2 Item 3 Item 4 Item 5

not print

not print

not print

Section & activities -viewing / hanging / dining Section & activities -urinate / setting / dining Stone Activities connection Elements Brick Metal Tie up Tie up Drove Weld Layers Focus area Author sidewalk facade building threshold fence threshold planned modified activities users

DRAWINGS here

grey box DRAWINGS here

grey box DRAWINGS here

grey box

City

Phnom penh Yan ZHANG

Lean Dining Dining hangViewing Dining Pee Put things Stone Activities connection methods Brick Metal OBSERVATION

INTERVENTION

Cambodia’s literacy rate remains low. With limited number of public library, the reading culture is still at its early growth. Moreover, this developing city still lacks common space for the general public to enjoy their time with the community.

Evidence

How might fences shape urban reading rooms around schools?

- Majority of the people that walked passed were individuals rather than groups or clusters.

- The busiest time period was during the time that school starts and ends which are 6:307:00 AM, 11:00 - 12:30 and 5:00 - 5:30.

The project aims to increase literacy rate and encourage reading culture through converting existing fences into a common reading space and a small public library that functions by donation. It would also divert people to use this side of the street more as this side of the road has very little activity.

- Most common age demographic is children & adults between the age of 6 - 45 years old.

Fency Books

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 33

Evidence Brief

Sekuan Phou

‘FENCY BOOKS’, PHNOM PENH, SEKUAN PHOU

spaces for children exist in the site area of Phnom Penh. I also noticed that many street stalls and store-houses have young children playing in and around them. I noticed that these children love superheros and imaginative play but have little resources to express this.

Evidence

How might school fences become playscapes?

surrounding Preah Norodom Primary School to create a space of play and interaction for both children of the school and the young children at the surrounding stalls?

How might we turn the sidewalk surrounding the school into an interactive space for both the children and the existing vendors?

How might we make this a multi-functional space that does not disrupt the current street life but rather enhances it and makes it appropriate for multiple age groups?

children playing on the sidewalk.

The way the play equipment effects that current vendors. That the space allows for role play & imaginative play of all ages.

a maze that protects from the street corner

a wall structure that protects from the street and allows kids to climb

a see saw passing through the school gate into the playground

a tunnel play and climbing structure

Preah Norodom Primary School

swings that act as play equipment and seating for the food stall a rope structure that you can walk along

a climbing structure that blocks / protects children from the street

a structure with woven rope loop seating that kids can hide and weave througout & provides seating for food stalls

weave through the ropes like spies weave through lazers, from interviews & observations i’ve noticed a lot of kids here LOVE superheros!

urban intervention

current street stall

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 34

INTERVENTION

‘THE PLAYGROUND CORRIDOR’ PHNOM PENH, TANDIA HARDCASTLE

CAN LANEWAYS PROVIDE PUBLIC AMENITY...?

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 35

. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 37

to see

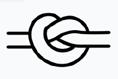

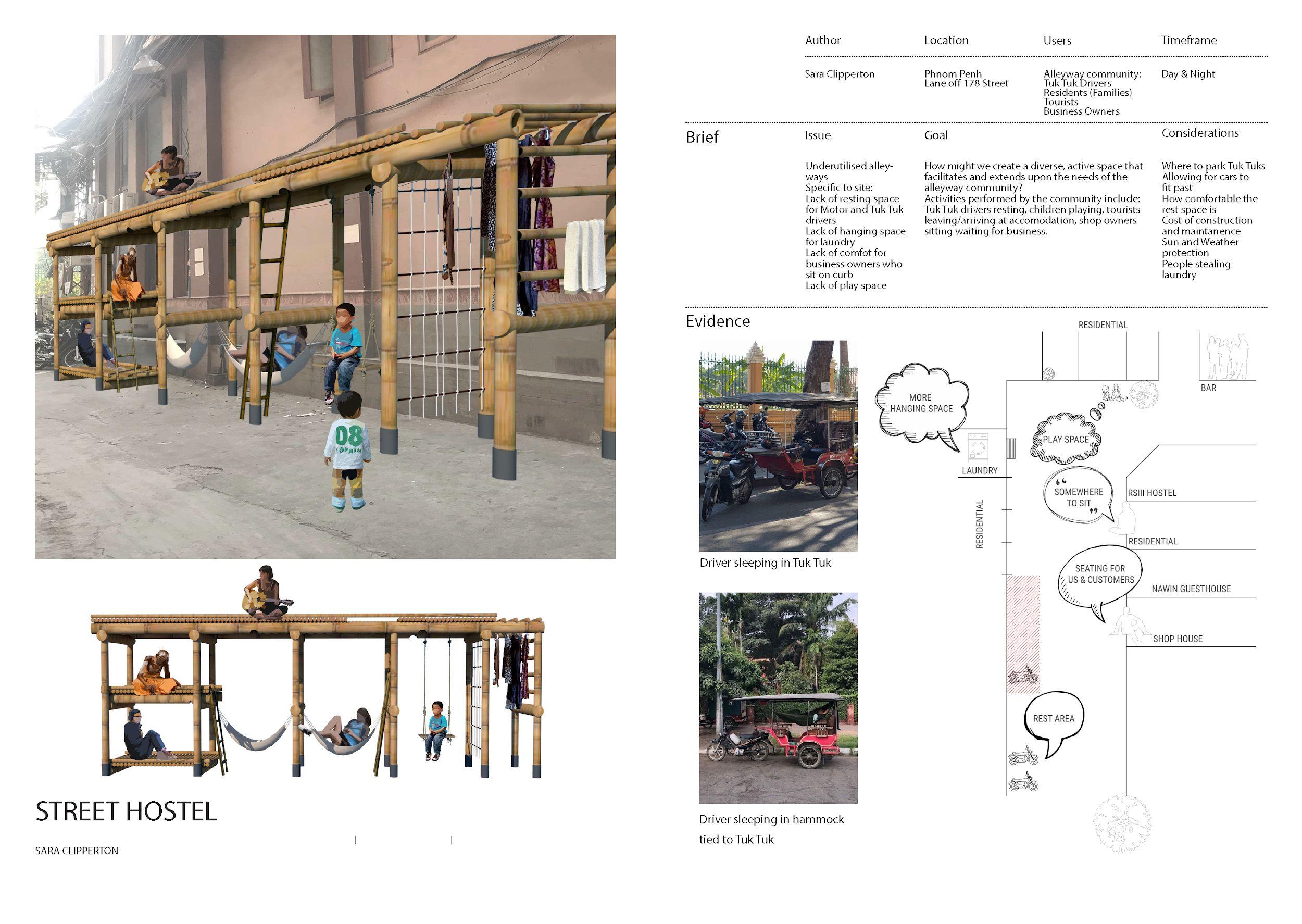

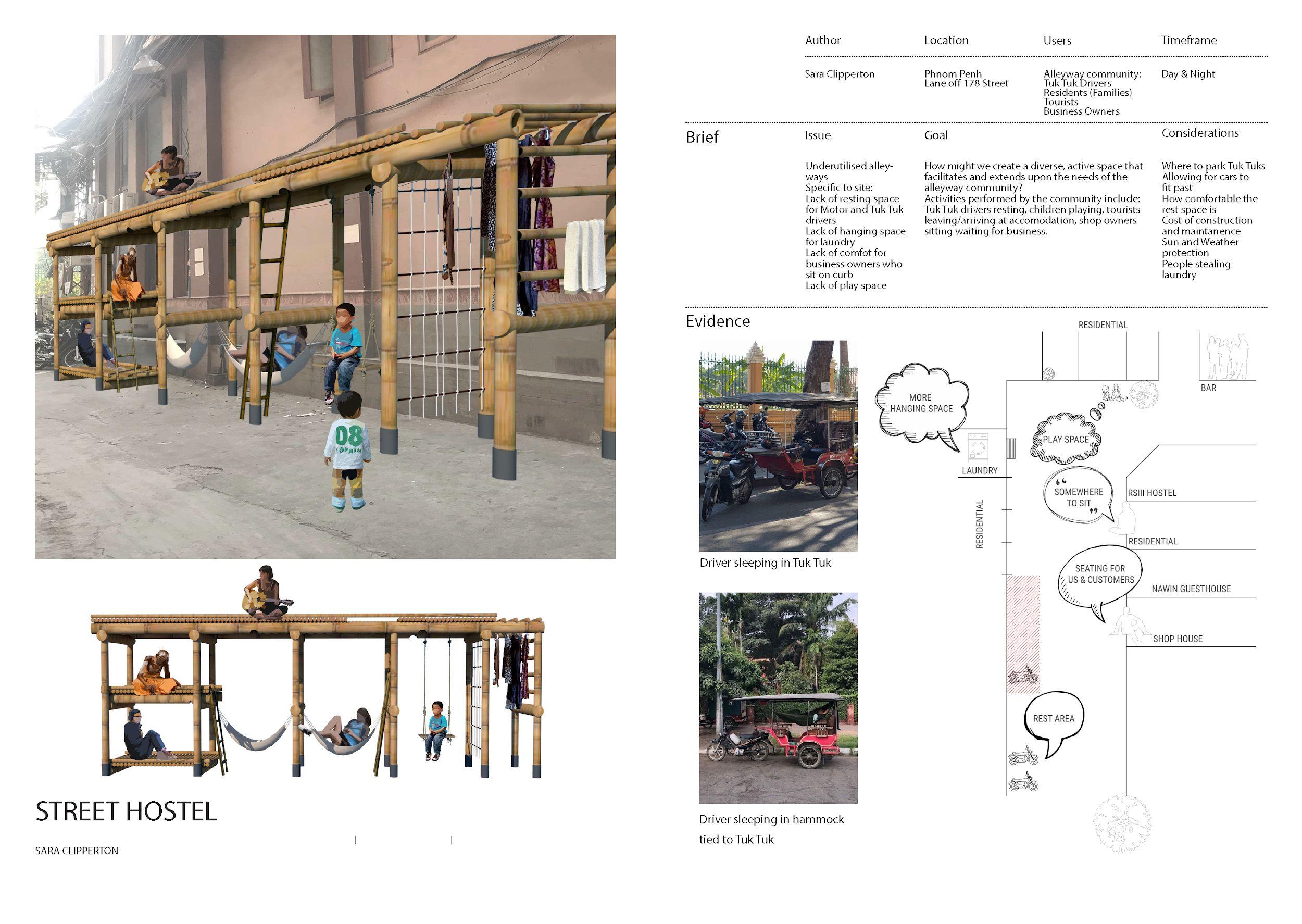

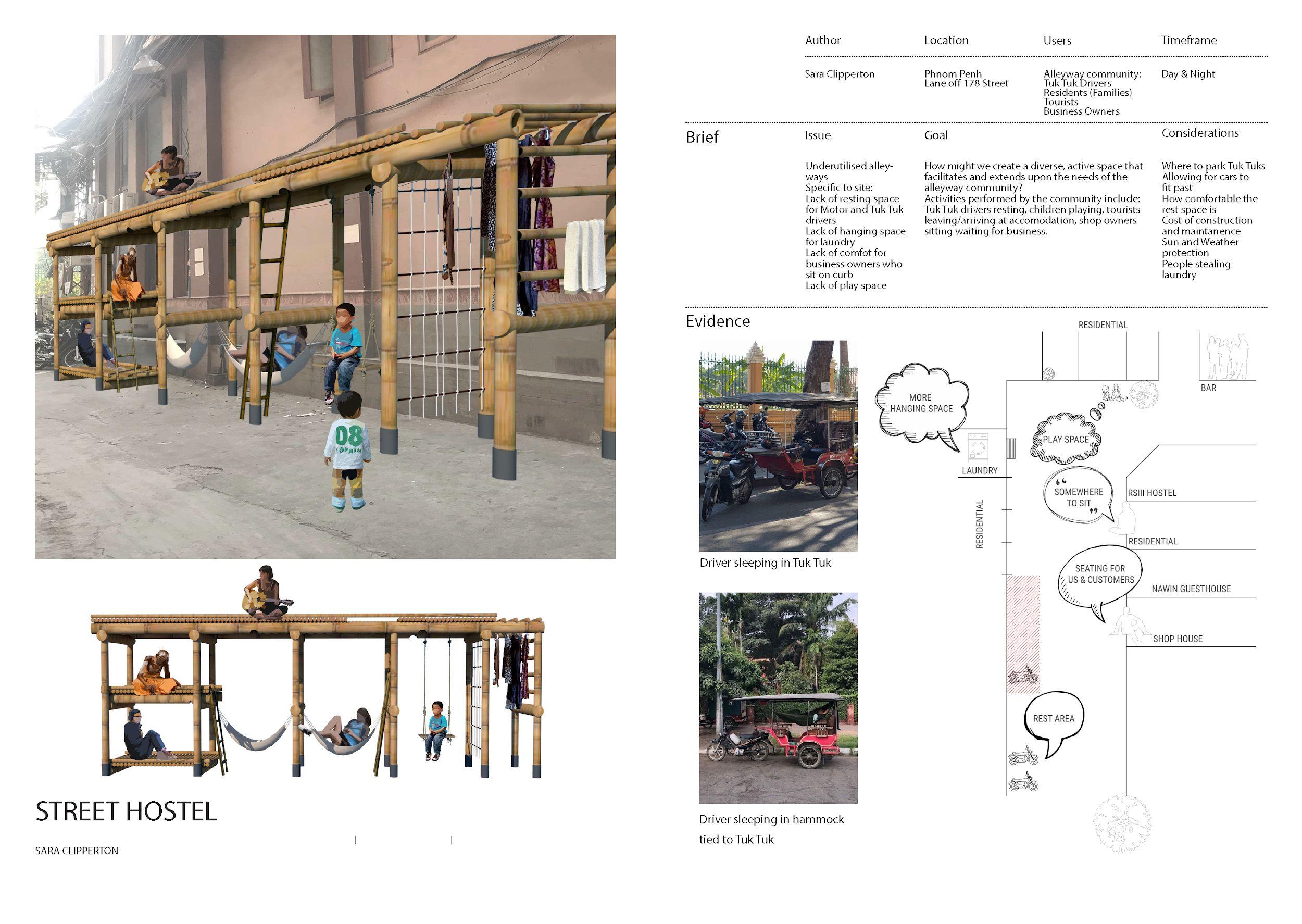

laneways improved? PHNOM PENH, SARA CLIPPERTON OBSERVATION

How do users want

their

How might a self-build ‘kit of parts’ support daily laneway activity? Sara

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh.

‘STREET HOSTEL’, PHNOM PENH, SARA CLIPPERTON

INTERVENTION

INTERVENTION

Evidence through Process

Evidence through Process

1. Interview:

exemplifies how the war challenged the livelihood of the streets, though now provides opportunities for the regeneration of social activity within residential boundaries.

A local alleyway resident suggested “if the fence was seethrough I could watch my kids play whilst doing housework.”

Evidence through Process

1. Interview:

A local alleyway resident suggested “if the fence was seethrough I could watch my kids play whilst doing housework.”

fabric curtains and perfectly placed lighting, the Kim Son Shadow Dancers emerge. Combining with the local Sovanna Phum Arts Association and their artists, illuminated shadows educate its users on Phnom Penh’s devastating past, and the undeniable hope for a better future. The space provides the community with a streetscape that encourages social, cultural and educational activity.

resolutions for easy construction and removal of event.

- The effect of the fabric curtains on the walkway below during the day.

- The ability to use this intervention intervention in other sites.

Design Process:

Design Process:

Kim Son Shadow Dancers

2. Transparency challenges: Privacy and security are lost when the concept of transparency is applied

2. Transparency challenges: Privacy and security are lost when the concept of transparency is applied

1. Interview: A local alleyway resident suggested “if the fence was seethrough I could watch my kids play whilst doing housework.”

4. Site Research

The Kim Son alleyway was once home to the Kim Son Chinese Theatre House before the Khmer Rouge devastation

How might diminishing theatrical practices be re-imagined

4. Site Research

The Kim Son alleyway was once home to the Kim Son Chinese Theatre House before the Khmer Rouge devastation

The sensitive design approach emerged from the existing composition of the space, highlighting the organic nature of the social acitivity that takes place. Using the powerlines as sightlines, and boundaries as thresholds, the intervention does not interfere with its occupants and their residencies, rather it encourages you to experience the space from a new perspective

Design Process:

2. Transparency challenges: Privacy and security are lost when the concept of transparency is applied

3. Transparency opportunity: Combined with lighting, the fence boundary becomes a threshold for social activity through immersive silhouettes

How might we... regenerate areas of conflict to create thresholds for social, cultural and educational activity.

Taryn Love

in urban laneways?

Shadow Dancers

conflict to create thresholds for social, cultural and educational activity.

3. Transparency opportunity: Combined with lighting, the fence boundary becomes a threshold for social activity through immersive silhouettes

4. Site Research

The Kim Son alleyway was once home to the Kim Son Chinese Theatre House before the Khmer Rouge devastation

5. Incoporation: The regeneration of Cambodian/ Chinese history is retold through illuminated silhouettes to create a temporary, site-sensitive theatre

The sensitive design approach emerged from the existing composition of the space, highlighting the organic nature of the social acitivity that takes place. Using the powerlines as sightlines, and boundaries as thresholds, the intervention does not interfere with its occupants and their residencies, rather it encourages you to experience the space from a new perspective

5. Incoporation: The regeneration of Cambodian/ Chinese history is retold through illuminated silhouettes to create a temporary, site-sensitive theatre

3. Transparency opportunity: Combined with lighting, the fence boundary becomes a threshold for social activity through immersive silhouettes

The users can choose to lay down on mats and watch the shadows y through the sky, or occupy the main theatre space where the shadow dancers perform.

5. Incoporation: The regeneration of Cambodian/ Chinese history is retold through illuminated silhouettes to create a temporary, site-sensitive theatre

6. Engagement: The users can choose to lay down on mats and watch the shadows fly through the sky, or occupy the main theatre space where the shadow dancers perform.

The sensitive design approach emerged from the existing composition of the space, highlighting the organic nature of the social acitivity that takes place. Using the powerlines as sightlines, and boundaries as thresholds, the intervention does not interfere with its occupants and their residencies, rather it encourages you to experience the space from a new perspective for social, cultural and educational activity.

6. Engagement: The users can choose to lay down on mats and watch the shadows fly through the sky, or occupy the main theatre space where the shadow dancers perform.

Kim Son Shadow Dancers

How might we... regenerate areas of conflict to create thresholds for social, cultural and educational activity.

Taryn Love

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 39

KIM SON SHADOW DANCERS, PHNOM PENH, TARYN LOVE

Children do not have a designated place for play.

The streets are either too busy or narrow, and can be dangerous particularly at night.

In Observation 1, it was observed that the hostile security on residential facades can have an isolating effect and limit interaction between neighbourhood kids.

Goal - To transform unactivated residential alleyways into playgrounds that promote interaction between neighbourhood children.

Children will gather and interact with the auditory horn kit of parts to explore space, shape and sound in their streets. Through playful innovation, this activity aims to build a stronger sense familiarity within the community.

The playground will light up at night. This not only adds to the sense of safety and security, but also creates a unique sense of intrigue that inspires curiousity.

How might laneways temporarily close to vehicles for ‘pop up’ play sessions?

Considerations

‘Can Western design ideas be “indigenized” to meet Asian cities needs?’ - Pu Miao, Asia Public Spaces

Research and interviews demostrate a negative user response toward urban design that is too unfamiliar to the distinct physical and cultural characteristics of Phnom Penh. It is important to consider this to avoid useless and bad design.

Cost and maintenance should also be considered.

Users ranked the level of importance of residential facade qualities based on personal preference.

Pedestrian, Age 20 Street User, Age 18

Pedestrian, Age 16

It was observed that there is more of an importance placed on clean outdoor spaces with aesthetic qualities. This is a challenge particularly in tight spaces in narrow alleyways. Sufficient evidence from interviews show that children do not have an allocated safe space for play other than their homes.

Children playing - Data from interviews

60% at home

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 41

Acoustic Playground Andrea Picones Aesthetics Outdoor Space for occupants Security Adaptability Advertising Cleanliness More important Evidence Brief Day or Non-schoolNighthours Children Timeframe Users Location Author Phnom Penh Narrow Residential Alleyways Andrea Picones

Response

Issue

40%

LOCATION CHALLENGES RESPONSE Lack of security Insufficient space Lighting Moveable structures ‘ACOUSTIC PLAYGROUND’, PHNOM PENH, ANDREA PICONES INTERVENTION

on street

can facades tell stories of community identity?

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 42

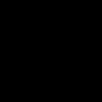

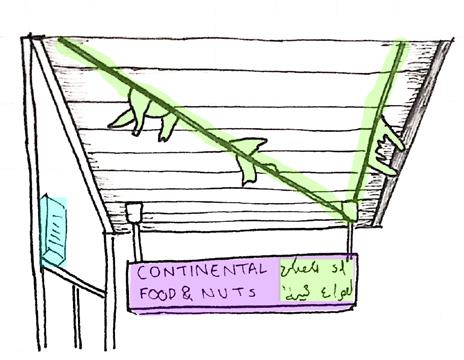

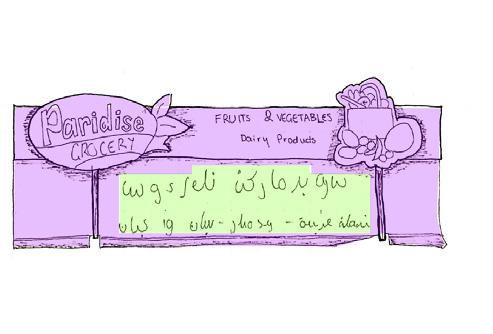

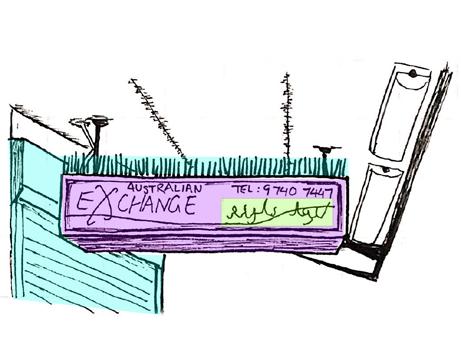

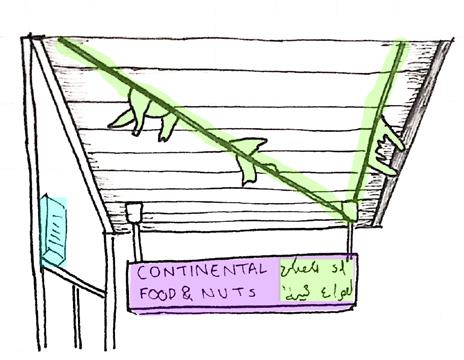

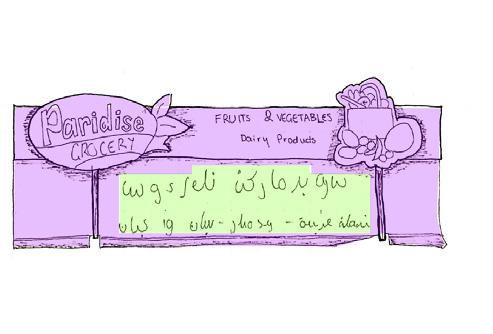

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 45 Elevation | 1pm | Joury Boutique | Sunny Elevation | 10am Paradise Grocery | Sunny Elevation | 11am Ali Supermarket | Sunny 3D | 10am Continental Food and Nuts Sunny 3D| 12pm Daily Shopping | Sunny 3D | 12pm | Australian Exchange | Sunny FACADE COMPONENT AWNING Drivers thermal comfort privacy cultural expression signage maximising display space sense of community security For

shopfront awnings modified

LAKEMBA, AMY GREENHALGH 1pm | Joury Boutique | Sunny 10am | Paradise Grocery | Sunny 11am | Ali Supermarket | Sunny Drivers thermal comfort privacy cultural expression signage maximising display space sense of community security OBSERVATION

what reasons are

by their users?

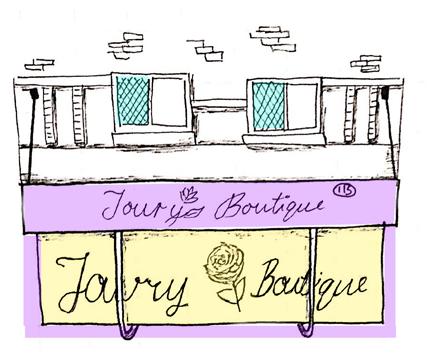

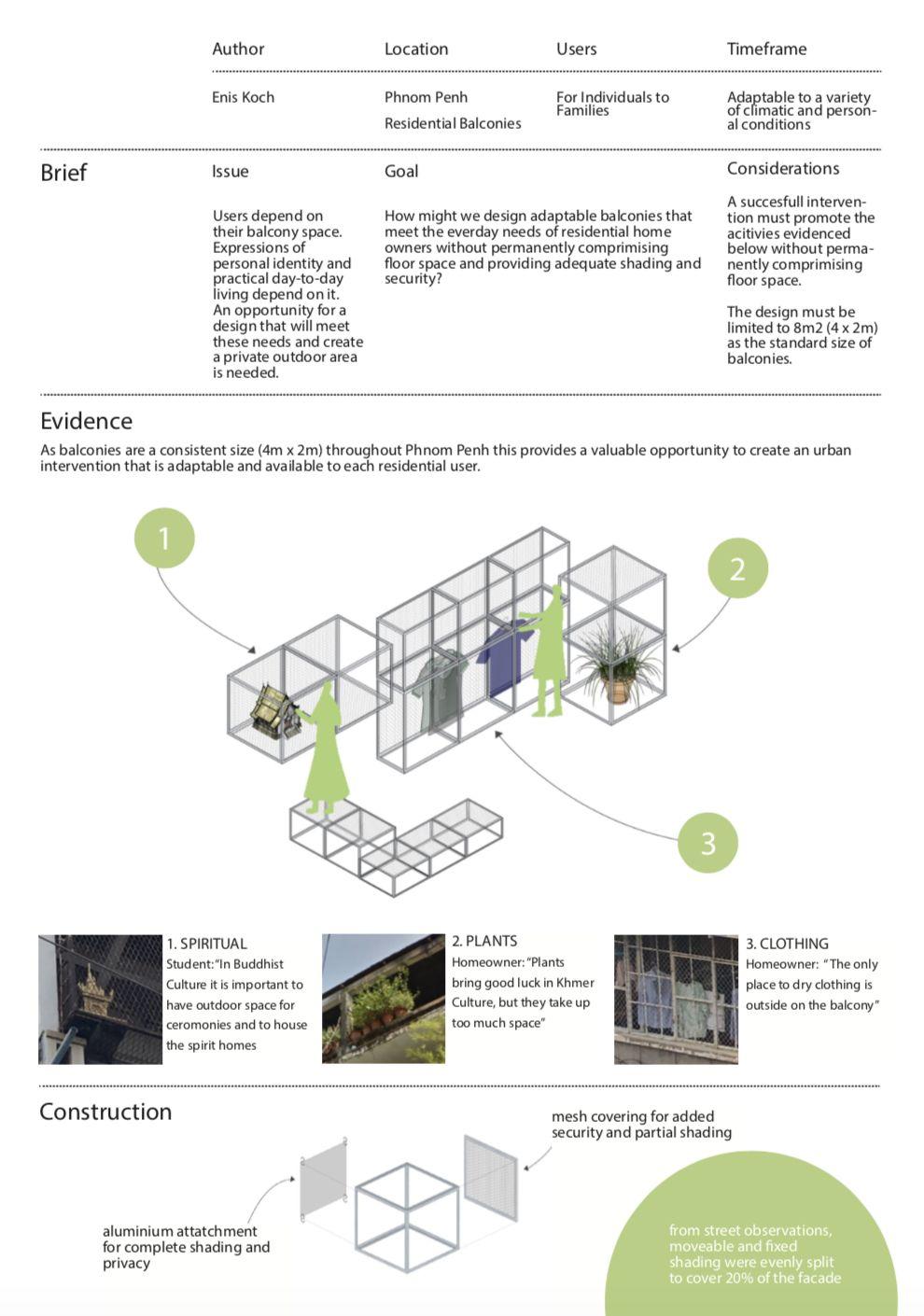

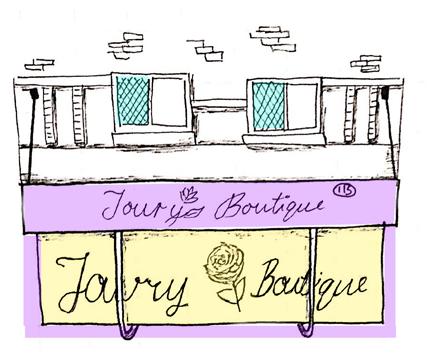

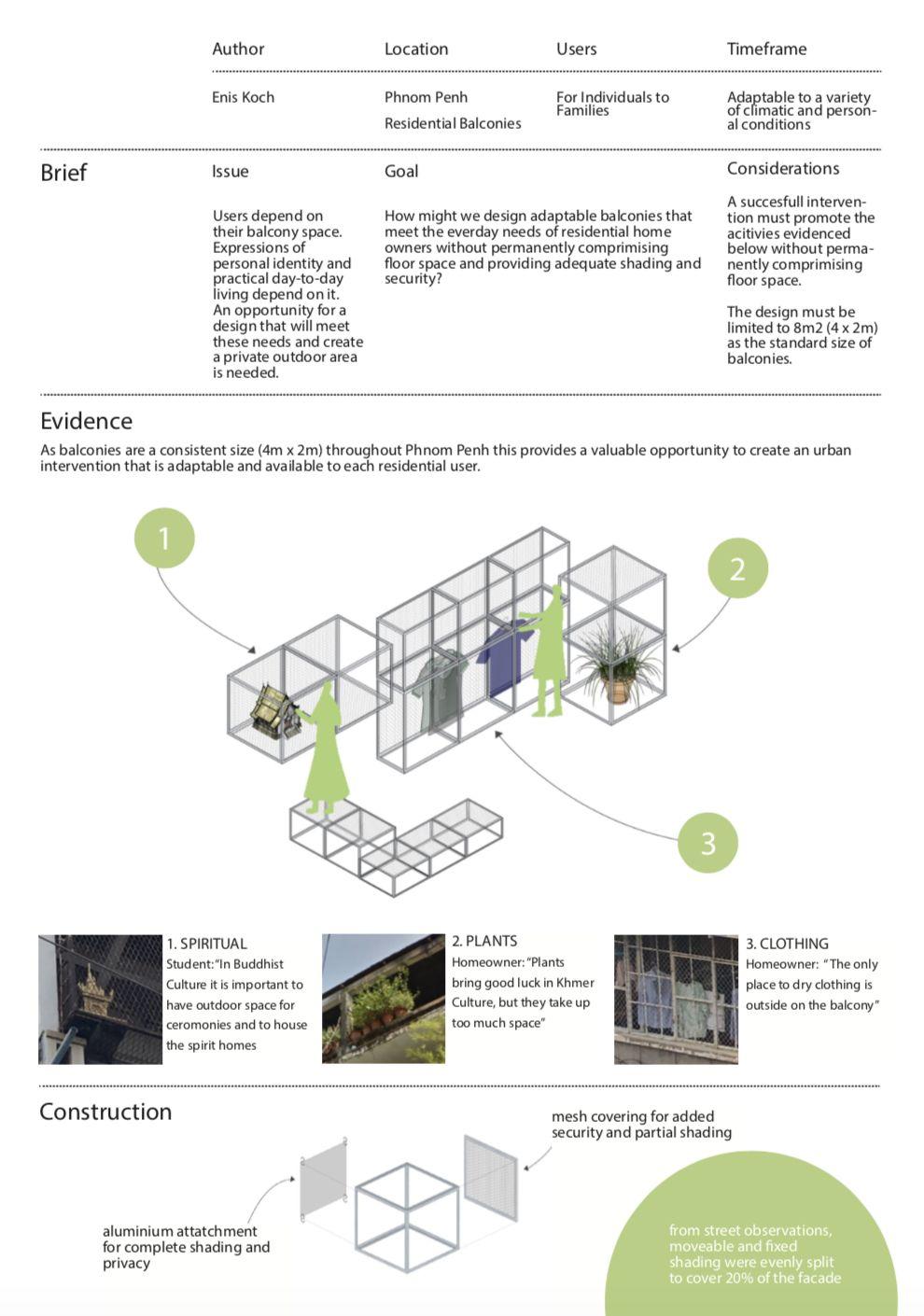

How might a modular system support everyday domestic activities on balconies?

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 46

‘THE URBAN ESCAPE’, PHNOM PENH, ENIS KOCH

INTERVENTION

INTERVENTION

How might a ‘drive-in’ cinema activate marketplace facades and underused streets at night?

Crowding of streets due to multiple activities; parking of motorcycles, serving of food, gathering to eat

Brief

How might we provide a ‘drive in’ experience for motorcycle drivers to maximise the usage of street space at night time?

Timeframe Users Location Author

Wide streets lacking activity at night time

Olivia Irwin

Most people travel by motorcycle with parked vehicles using a high portion of street

In order to be successful, the form of the intervention is to be in modules that are collapsable so they can be easily packed away and stored

Phnom Penh

In wide streets; in front of shops that shut down at night time

The proposed intervention combines the functions of parking, eating, gathering and cinema to effectively utilise valuable street space. It utilises unused building walls, maintains road space, provides an opportunity for market sellers to sell/ serve food and provides a unique cinema experience. The intervention could be implemented in multiple locations with similar spatial features.

Temporary event occurring weekly Motocycle users; all demographics

The streets chosen are to be wide and must have inactive/ closed shops behind, so not to detract sales

Issue Response Considerations

Motorcycles as urban furniture... How is a stationary motorbike used in the street at night time?

Crowding of streets due to multiple activities; parking of motorcycles, serving of food, gathering to eat

Wide streets lacking activity at night time

Most people travel by motorcycle with parked vehicles using a high portion of street

Evidence

Quiet, inactivated space at night time...

How might we provide a ‘drive in’ experience for motorcycle drivers to maximise the usage of street space at night time?

The proposed intervention combines the functions of parking, eating, gathering and cinema to effectively utilise valuable street space. It utilises unused building walls, maintains road space, provides an opportunity for market sellers to sell/ serve food and provides a unique cinema experience. The intervention could be implemented in multiple locations with similar spatial features.

In order to be successful, the form of the intervention is to be in modules that are collapsable so they can be easily packed away and stored

The streets chosen are to be wide and must have inactive/ closed shops behind, so not to detract sales

Motorbikes are used for multiple functions other than transport; resting, sitting, leaning, eating, collecting food

How does it work?

Motorcycles as urban furniture... How is a stationary motorbike used in the street at night time?

roll down screens with film on unused wall

films shown will be from upcoming & emerging directors serving of food

wide street

sit, relax, eat, view

Motorbikes are used for multiple functions other than transport; resting, sitting, leaning, eating, collecting food

Quiet, inactivated space at night time... roll down screens with

How does it work?

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 47

Brief moto in Olivia

Motocycle

Users Location Author Phnom

In

Evidence

Irwin Temporary event occurring weekly

users; all demographics Timeframe

Penh

wide streets; in front of shops that shut down at night time Olivia Irwin

Issue Response Considerations

happens during the day?

What

single module for 3 bikes front supports removed collapsable tables easily stacked & stored

‘MOTO IN’, PHNOM PENH, OLIVIA IRWIN

How might an app allow those new to a city to better understand local street food culture?

‘STREET FOOD SCANNER’, YUXIN (CYNTHIA) WANG

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. 49

INTERVENTION

CAN SIDEWALKS BECOME ‘URBAN ROOMS’?

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 50

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 51

Shop Preference 05 2pm | Hospitality | Sunny Shop Preference 06 | 2pm Hospitality | Sunny Seating Shading - Horizontal Thresholds Vertical Thresholds Privacy Shop Preference 03 2pm | Hospitality | Sunny Shop Preference 04 | 2pm Hospitality | Sunny Shop Preference 01 11am | Hospitality | Sunny Shop Preference 02 | 11am| Hospitality | Sunny 15% Enclosure 30% Enclosure 45% Enclosure 60% Enclosure 75% Enclosure 90% Enclosure What ‘urban room’ typologies exist? PHNOM PENH, TYLA VENISH OBSERVATION

OBSERVATION 03 THRESHOLD PREFERENCES

Objects on the sidewalk stretching to the streets attracts the attention of the passerby.

shops have placed seats close to the counters setting a of conversation.

Objects on the sidewalk stretching to the streets attracts the attention of the passerby.

The glazed stores tend to focus on a different set of people thereby cutting much interaction towards the streets.

glazed stores tend to focus on a different set of people thereby cutting much interaction towards the streets.

INFOGRAPHIC

INFOGRAPHIC

Phnom Penh Sriniklesh Balachandran

CONCLUSIONS

extending the counter out on to the sidewalk thereby broadening the threshold creates more interaction than those set the counters within the shopfront.

shops have placed seats close to the counters setting a of conversation.

Objects on the sidewalk stretching to the streets attracts the attention of the passerby.

OBSERVATION

How does the position of the retail counter affect social interaction across urban interior thresholds?

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 53

planned modified activities users INFOGRAPHIC CONCLUSIONS sidewalk facade building threshold fence threshold Phnom Penh Sriniklesh Balachandran 1 2 - Some shops have placed seats close to the counters setting a point of conversation. Objects on the sidewalk stretching to the streets attracts the OBSERVATION 01 Threshold porosity Layers of porosity with objects and Counters People Counter Objects Glazing Advertisement 3 Elevation 11:40am Street 13 Mostly Cloudy 2 Elevation 3:40pm Street 13 Mostly Cloudy 1 Elevation 3:00pm Street 13 Mostly Cloudy

Scale of Interaction

Scale of Interaction Layers Focus area Author planned modified activities users

INFOGRAPHIC City sidewalk facade building threshold fence threshold

Mobile stores and restaurants blur the threshold of the shop by the placement of counter and objects on the sidewalk. also varies the levels of interaction between the retailer customers.

glazed stores tend to focus on a different set of people thereby cutting much interaction towards the streets. PHNOM PENH, SRINIKLESH BALACHANDRAN

Phnom Penh, Sara Clipperton

Street users preferences in shop fronts is highly dependant on the objects that are found in their thresholds.

In the first interview the shop owners valued seating objects and open thresholds near the river side where there is less activity and street life that can allow for a more relaxing street experience. Interviewee 2 was a tuk tuk driver who preferred thresholds that attract a lot of custemors, this being a general store ‘Smile’. The stores closed threshold is still attractive to street users as this means air conditioning and respite from the sun is possible. The last interview differed from the first 2 as the shop owner valued objects on the street, but would prefer if stores could leave more room for the passing by. The market shop fronts were their preferred thresholds as many needs can be fulfilled in the one area. To conclude, it can be observed that differing objects are highly influential on users preferred thresh-olds and can change the experience of street life drastically.

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 54 Favourite Threshold Reason Section | 6:00pm | Market Shop Front Elevation | 5:30pm ‘Smile’ Mini Mart Sketch | 5:00pm Riverside Restaurant THRESHOLDS 03 INTERVIEWS & OBJECTS

front preferences and the

objects INFOGRAPHIC

Shop

corresponding

planned modified activities users sidewalk facade building threshold fence threshold Layers Focus area City Author

CONCLUSIONS

What would users like to see change in sidewalk spaces adjoining food outlets? PHNOM PENH, SARA CLIPPERTON OBSERVATION

Preah Norodom Wind Catcher

Matthew Johnstone

Matthew Johnstone

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 56

Evidence Brief

How might renewable energy infrastructure also provide amenity in sidewalks?

INTERVENTION

‘PREAH NORODOM WIND CATCHER’, PHNOM PENH, MATTHEW JOHNSTONE

the bubble to store unnecessary items such as rubbish.

INTERVENTION

EVIDENCE

Andy Kitsinger, consultant who focuses on helping clients build stronger communities studied the idea of tactical urbanism and how small scale interventions can alter the public realm, making it more user-friendly for the public.

A common theme throughout my observations was the importance of having a connection with spirituality on a daily basis. From this, spirituality became a big theme that arised and it allowed me to focus on the theme of Buddhism within Phnom Penh.

LINK TO OBSERVATION ACTIVITY + POTENTIAL SITE:

Positive Influences

Negative Influences

As a example of a potential site, the fence line and sidewalk along Wat Ounalom has been explored. This particular pagoda serves as the headquarters of Cambodia where some of the countries Buddhist brotherhood live, along with a large number of monks.

LINKING THE DESIGN TO BUDDHISM:

Buddhist Flag -> colour choice

Dharma Wheel -> form of structure

Eternity Knot -> connection between structural elements

SPIRITUAL BUBBLE

Daniela Novakovic

see smell

hear

STREET LIFE STUDIES 2019/20. Built Environment, University of New South Wales, Sydney. Architecture and Urbanism, Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh. www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com 57

What if small spaces for spiritual practice were allowed for on sidewalks?

‘SPIRITUAL BUBBLE’, PHNOM PENH, DANIELA NOVAKOVIC

stered

CREDITS

White

For more information

www.streetlifestudies.wordpress.com #streetlifestudies

Eva Lloyd e.lloyd@unsw.edu.au

Giacomo Butte giacomo.butte.2@gmail.com

Richard Briggs honbriggsdesign@gmail.com

New Colombo Plan Logo

of the New Colombo study in the region. xternal

Pen Sereypanga pagnaserey@gmail.com

New Colombo Plan correspondence

The New Colombo Plan logo is a registered trademark and is legally protected.

A sincere thank you to:

The logo is the primary, most easily recognisable image of the New Colombo Plan. The logo is comprised of:

• The New Colombo Plan logo

• New Colombo Plan written in full

The University of New South Wales, Built Environment, for supporting the fifth installment of this international summer elective.

• The New Colombo Plan tag line: Connect to Australia’s future - study in the region.

Our partner university in Phnom Penh, The Royal University of Fine Arts, Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism.

The logo should be included on all external New Colombo Plan correspondence and documents, both printed and electronic.

electronic. available in two variations: the gradient and the use on light Light blue logo

UNSW students

Olivia Irwin

Daniela Novakovic

Rennie Kwan Yee

Andrea Picones

Amy Greenhalgh

Enis Koch

Yuxin Wang

RUFA students

Oum Ratanakvisal

Moeung Manith

Sarin Sovann Rith

Pov Sonita

Dear Stephania

Phou Vannsim

Sonah Seang

UNSW staff

Course coordinators

Eva Lloyd

Giacomo Butte

Richard Briggs

Pen Sereypagna

Director Interior Architecture

Guest talks and critique

Vuth Lyno, Sa Sa Art Projects

Pen Sereypagna, New Khmer-Architecture

Makara Hong, UNESCO Cambodia

Nick Beresford, UNDP Cambodia

Site visits

The New Colombo Plan logo is available in two variations:

All students involved, who worked with dedication and rigour.

• White and light blue for the use on the gradient and dark coloured backgrounds