The CFO and finance team are well positioned to mitigate the prolonged supply chain disruptions that have challenged cash flow and profitability.

26/ 34/ 40/ 48/

COVER STORY By combining data analytics and business insights, CFOs can act as partners and catalysts in helping to overcome supply chain challenges.

BY THOMAS G. CANACE, PH.D., CPA; AYAZ JAFFER, CPA; AND PAUL E. JURAS, PH.D., CMA, CSCA, CPA

BY THOMAS G. CANACE, PH.D., CPA; AYAZ JAFFER, CPA; AND PAUL E. JURAS, PH.D., CMA, CSCA, CPA

A survey examines the impact that practices have on organizational success.

BY LU JIAO, PH.D.; KEVIN BAIRD, PH.D., FCPA; AND NURADDEEN ABUBAKAR NUHU, PH.D.The Earned Capital Approach provides a clear and simple solution to a long-standing challenge.

BY MARY HILL, PH.D., CPA; GEORGE W. RUCH, PH.D.; AND RICHARD A. PRICE III, PH.D.Want more out of your accounting and finance career? Then you need to establish a personal brand that best reflects your abilities, values, and ethics. For aspiring professionals, it has become a necessity rather than a nice-to-have.

BY DONALD W. CAUDILL, PH.D., AND PHILIP J. SLATER, CMA

IMA helps you gain in-depth expertise on important issues shaping the finance and accounting profession.

This six-course certificate program provides essential education to finance and accounting professionals that will demystify business sustainability and offer keys to effectively deploying initiatives that comply with evolving ESG requirements.

IMA Member $299 // Nonmember $449 10.8 NASBA CPE

This five-course certificate program provides critical knowledge, skills, and effective practices to help finance and accounting professionals foster a diverse, equitable, and inclusive environment.

IMA Member $149 // Nonmember $249 7.5 NASBA CPE

with each certificate program.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF CHRISTOPHER DOWSETT, CAE cdowsett@imanet.org

SENIOR EDITOR ELIZABETH KENNEDY ekennedy@imanet.org

SENIOR EDITOR NANCY FASS nfass@imanet.org

FINANCE EDITOR DANIEL BUTCHER daniel.butcher@imanet.org

STAFF WRITER/EDITOR LORI PARKS lori.parks@imanet.org

SENIOR DESIGNER JAMIE BARKER jamie.barker@imanet.org

Bruce R. Neumann, Ph.D. Academic Editor

Ann Dzuranin, Ph.D., CPA Associate Academic Editor

William R. Koprowski, Ph.D., CMA, CFM, CFE, CIA Associate Academic Editor

For more information on the role of the Editorial Advisory Board and a complete list of reviewers, visit sfmag.link/reviewers

The R.W. Walker Company, Inc. mike@rwwcompany.com (925) 648-3101

FOR REPRINT INFORMATION, CONTACT: sfmag@imanet.org

FOR PERMISSION TO MAKE 1- 50 COPIES OF ARTICLES, CONTACT: Copyright Clearance Center, www.copyright.com

Strategic Finance® is indexed in the Accounting and Tax Index by ProQuest at www.il.proquest.com

Except as otherwise noted, the copyright has been transferred to IMA® for all items appearing in this magazine. For those items for which the copyright has not been transferred, permission to reproduce must be obtained directly from the author or from the person or organization given at the end of the article.

Views expressed herein are authors’ and do not represent IMA policy unless so stated. Publication of paid advertising and new product and service information does not constitute an endorsement by IMA of the advertiser or the product or service.

Strategic Finance® (ISSN 1524-833X/USPS 327-160) Vol. 10 4, No. 12, June 202 3. Copyright © 202 3 by IMA. Published monthly by the Institute of Management Ac coun tants, 10 Paragon Drive, Suite 1, Montvale, NJ 07645. Phone: (201) 573-9000. Email: sfmag@imanet.org

MEMBER SUBSCRIPTION PRICE: $48 (included in dues, nondeductible); student members, $25 (included in dues, nondeductible).

www.sfmag.link/sustainability

A monthly blog covering ESG strategy, reporting, and disclosure topics such as:

● Accountants’ role in sustainability initiatives

● Success stories of companies that prioritize sustainability/ESG

● Insights on decision-useful nonfinancial metrics and data

PEOPLE HAVE KNOWN for a long time that AI tools are incredibly relevant for our profession, but lately we’ve been hearing about some new technologies that are significantly changing business, academia, science, and potentially every aspect of life.

The key to getting the most out of both ChatGPT and Auto-GPT, however, is the ability to pose the proper prompts. Without this, you’re facing the classic “garbage in, garbage out” problem. The same is true for many areas of life: Asking the right questions is the best way to get at the heart of a difficult decision or navigate the clutter of a multitude of choices. In my own experience, I’ve also found asking questions is often the simplest and most effective way of learning.

Gwen van Berne, CMA, is director of finance and risk at Oikocredit and Chair of the IMA Global Board of Directors. She’s also a member of IMA’s Amsterdam Chapter. You can reach Gwen at gwen.vanberne @imanet.org or follow her on LinkedIn at bit.ly/3LVeRGM

Recently, I was walking the family dog with a friend who is a well-respected technology expert, and we talked about our ideas and experiences with one of these AI tools, ChatGPT, which has dominated the news lately. ChatGPT is a chatbot that generates human-like responses to various prompts, and we had some fun testing the output to several heavy-content questions and seeing how ChatGPT dealt with these and our follow-up questions.

ChatGPT has already become an enormous game changer, but when my friend told me about Auto-GPT, which automates task-oriented conversations and provides structured and specific responses, all without requiring human intervention, I was really blown away and confronted with a mind-boggling and pretty hard truth. My friend showed me how the agents from Auto-GPT worked with an assignment he gave, and he told me about a variety of new products and services now possible through this tool. Seeing the output and independent thinking and acting abilities of Auto-GPT gave me a very concrete picture of the potential AI has to change the way we work and our lives in general.

In the world of business, accounting and finance professionals can gain influence and advancement opportunities if we practice and perfect the art of asking the right questions. Having excellent communication and interpersonal skills helps as well, as does being cognizant of the needs of those who have a stake in the questions posed and answers given. On this subject, I was inspired by a recent Het Financieele Dagblad interview (bit.ly/42c3a7q) with Ellen Garvey-Das of Egon Zehnder, where she explained that modern leaders need to be able to listen to their stakeholders. In my view, active listening requires being open-minded, using all your senses, paying attention to verbal and nonverbal clues, and refraining from judgment. If you combine these listening skills with your ability to ask the right questions while also trusting your value system, you’ll be able to lead in the world of tomorrow.

With these words, I conclude my final Perspectives column as your IMA Chair. It has truly been an honor to serve as IMA’s volunteer leader this past year, and I hope to contribute to the profession in new ways once my term of service is done. I will always be grateful for this opportunity. Thank you. SF

BERNE, CMA

«It has truly been an honor to SERVE AS IMA’S VOLUNTEER LEADER this past year.»

IMA members became CMAs between April 1 and April 30, 2023.

The names of all the new CMAs can be found on the Strategic Finance website at sfmagazine.com/issue

/june-2023 .

For more information on CMA certification, visit www.imanet.org /cma-certification .

Mentoring, toughness, and teamwork can improve performance in the finance function.

Eric Kapitulik and Jake MacDonald are former U.S. Marines who adapted their special forces training into a book called The Program: Lessons from Elite Military Units for Creating and Sustaining High Performance Leaders and Teams, as well as a live seminar. The program is intended to help organizations build stronger teams and improve leadership by explaining concepts through the lens of team-based physical disciplines as well as military training programs.

They also utilize analogies from the world of sports, corporations, and even schools. Kapitulik and MacDonald explain takeaways from their experiences running a military training program, climbing Mount Everest, and overcoming other challenges, often stepping well out of their comfort zone to accomplish their goals.

Kapitulik and MacDonald believe that talent is common, but discipline and a framework to accomplish team missions are often lacking. Teams need to learn and adhere to core values of their own choosing, and the authors lay out the groundwork for doing so. They also provide information on what it means for colleagues to hold each other accountable.

Although the book stresses the importance of physical and mental toughness, the program entails a significant amount of relationship building and concern for the well-being of others. The authors criticize management styles that create sharp divisions between team members and leadership. Hands-on mentoring and coaching are considered far more suitable for effective team building. There’s no shortage of examples to drive home the points in the book, from the University of Michigan’s basketball team’s infamous time-out disaster to battlefield medicine in a crisis situation.

The Program, especially in the beginning, may bog down a reader with jargon and definitions that can be hard to follow at first glance, and the level of detail with which these concepts are described seems more suited to a live audience than a printed work. Nevertheless, the book is a fascinating read that explains the thought process behind the authors’ philosophy. The advice in The Program could help others succeed in their missions, whether they’re in an elite military unit, the finance function of a company striving to increase business, or a sports team looking for an edge.

Yuliya BaranovskayaIMA® would like to thank and acknowledge the following members, chapters, councils, individuals, and companies who made tax-deductible contributions to IMA’s Annual Giving Campaign designated to the following themes from May 1, 2022, to April 30, 2023:

■ IMA initiatives and its overall Annual Giving Campaign

■ IMA Leadership Academy

■ IMA Memorial Education Fund, Inc. Scholarship

■ IMA Research Foundation

Tax-Deductible Contributions Received from May 1, 2022, to December 31, 2022:

Tax-Deductible Contributions Received in 2022 Designated to IMA initiatives and its overall Annual Giving Campaign

Robert Half

Shauna Aryee

Whitney Allison Glover

Peter J. Dolan, CMA, CSCA, CFM, CPA

Tax-Deductible Contributions Received in 2022 Designated to IMA Leadership Academy

Jason Larue Barrett

Gail S. Sawyer-Walker

Felix A. Telado, CMA, CFM

Anindya Bagchi, CMA, CSCA

Yuqing Zhang, CMA

Jonathan Camacho, CMA

Sameera Vimarshan

Mallawa Arachchige

Don, CMA

Mahmoud Ibrahim Husseini

Mohamed Eltawil, CMA

Suitao Yang, CMA, CPA

Fahim Ashraf, CMA

Daniel F. Cleary, CMA, CPA

Brendon K. Sehorn, CMA, CPA

Wael H. Al Rasheed, CMA, CSCA

Tad C. Miller, CMA, RTRP

Larry F. Core, CMA, CPA

Jerry Stecher

Karvol Karlos Mackey, CMA, CPA, CTP

Catherine B. Long, CMA

Richard T. Brady, CMA, CGFM

John B. Dever, CPA

Thomas G. White, CMA

Susumu Sakiyama

Abdulaziz Ashur Said, CMA, CFM, CPA, CFA

Kareem Nuseibeh

Jacklynne Fair Sy Cabigunda, CMA

Jamil I. El Halabi, CMA, CFM, CPA, CFE

Martha C. Gibson, CMA

Lisa M. Coyle, CMA

Cherryl Almazan Tolentino, CMA

Amin Bogari, CMA

Esam Ziad Taan

Elizabeth Helbig

Nanda Senathi, CMA, CPA

Gerald C. Reiss, CMA, CPA

Nancy C. McCleary, CPA

Krishna Prasad, CMA

Katherine Sheena Tugade, CMA

Sandra D. Giani-Kipnes, CMA, CPA

Troy K. Senter, CMA, CPA

Derek McSpadden, CMA

Scott G. Davis, CPA

Sean M. Phillips, CMA, CFM, CPA

Rodora Medenilla Lizardo, CMA, CPA

Ntshana Jim Matsemela Jr.

Faizan Ashraf, CMA

Kaneez Zainab Jamal

John C. Macaulay, CMA

John E. Hetrick, CMA

Marc L. Paper, CMA, CPA

Mazen I. Al Sadi, CMA

Sherin Joseph

Yin Chen Hsu, CMA

Raymond M. Tokarz, CMA

Shyama P. Banerjee, CMA

■ IMA Stuart Cameron McLeod Society Scholarship

■ IMA Student Leadership Conference

■ IMA Century Student Scholarship Fund

Tomas Raymond Martinez, CMA

Anne Leighty

Lisa S. Pendergrass, CMA, CPA

Louise E. Crider

Fadi Sami Al Amer, CMA, CSCA

Marina Capobianco, CMA

Ahmad Almaie Sr., CDP, PMP

J. Stephen McNally, CMA, CPA

Tracy L. Taylor

Tax-Deductible Contributions Received in 2022 Designated to IMA

Memorial Education Fund, Inc. Scholarship

Eric D. Weedon

Philip A. Zammataro Jr., CPA

Jason Larue Barrett

Shauna Aryee

James E. Duffie, CMA, CPA

John J. Cifu, CMA, CFM

Cynthia L. Preston, CMA, CFM

Anindya Bagchi, CMA, CSCA

Jonathan Camacho, CMA

Daniel Christopher Miller

Prakash Chandra Sharma, CMA

Essam E.M. Moustafa Hussein

Henry A. Rueden, CMA, CPA

Loutfi K. Echhade, CMA, CFM, CPA, CFE, CIA, CISA, CBM

Monica A. Zillman, CMA

Yuen-Ching Choi, CMA

Steven F. Mahns, CMA, CPA

Cynthia J. Khanlarian, CMA, CPA

Brad Ledford, CMA, CPA

Stephen E. Platt, CMA

Daniel F. Cleary, CMA, CPA

Wael H. Al Rasheed, CMA, CSCA

Emma Cole

Karvol Karlos Mackey, CMA, CPA, CTP

Catherine B. Long, CMA

Charlie J. L’Heureux, CMA

Richard T. Brady, CMA, CGFM

Sally K. Hagen, CMA

Howard B. Allenberg, CPA

Rodger L. Muschett

John B. Dever, CPA

Catherine Weber, CMA, CPA

Kenneth Alfred Sam, CMA

Owen King

Abdulaziz Ashur Said, CMA, CFM, CPA, CFA

Kareem Nuseibeh

Jacklynne Fair Sy Cabigunda, CMA

Melissa A. Howsare

Steven E. Shamrock

Constance D. Larsen, CMA, CFM, CPA

Daniel F. Viele, CMA, CPA

Lee H. Nicholas, CMA, CPA

Timothy D. Cairney

Patricia Siegfried

Cherryl Almazan Tolentino, CMA

Mostafa Ahmed Tawfik, CMA

Veronica Alexander

Amazon Smile

Douglas E. Ziegenfuss, CPA, CGFM

Nick Morganti, CMA, CFM

Michael F. Ruff, CMA, CPA

Esam Ziad Taan

Ratheesh Avaronnan, CMA

Nanda Senathi, CMA, CPA

Gerald C. Reiss, CMA, CPA

John R. Myles

Bruce E. Willman, CMA, CFM

Krishna Prasad, CMA

Huggins Phiri, CMA

Jose E. Munoz Jr.

Mark H. Komatsu-Yonezawa

Katherine Sheena Tugade, CMA

Sandra D. Giani-Kipnes, CMA, CPA

Troy K. Senter, CMA, CPA

Derek McSpadden, CMA

William M. Watts, CMA

Scott G. Davis, CPA

Joseph M. Hargadon, CMA, CPA

Bruce A. York, CMA

Pemberton Smith, CMA, CFM

Sean M. Phillips, CMA, CFM, CPA

Michael F. Monahan

David J. Barrett, CMA

Sinan Alpozer, CMA

James D. Beck, CPA

Ntshana Jim Matsemela Jr.

Victoria Abdurashitova, CMA

Faizan Ashraf, CMA

Kaneez Zainab Jamal

Shirley J. Daniel

John E. Hetrick, CMA

Tufail Potrick, CMA

James A. Rimmel II

Sherin Joseph

Judson Buchan, CMA

Kristine K. Parsons, CMA, CFM

Tomas Raymond Martinez, CMA

Robert D. Brew, CPA

Lisa S. Pendergrass, CMA, CPA

Glenn C. Campbell, CMA

Megan J.F. Will, CMA

Kenneth M. Ashford

Louise E. Crider

Ahmad Almaie Sr., CDP, PMP

Peter J. Dolan, CMA, CSCA, CFM, CPA

Frederick E. Schea, CMA, CSCA, CFM, CPA

Christopher E. McCoy, CMA

Thomas Lenin, CMA, CPA, CITP, PMP Kathy Williams

Tax-Deductible Contributions Received in 2022 Designated to IMA Research Foundation

Cynthia L. Preston, CMA, CFM

Emma Cole

Catherine Weber, CMA, CPA

Lee H. Nicholas, CMA, CPA

Ahmed Elsyed Hazza

Veronica Alexander

Michael F. Ruff, CMA, CPA

Mark H. Komatsu-Yonezawa

Shirley J. Daniel

Taylor & Francis Group LLC

Peter J. Dolan, CMA, CSCA, CFM, CPA

Tax-Deductible Contributions Received in 2022

Designated to IMA Stuart Cameron McLeod Society Scholarship

Loutfi K. Echhade, CMA, CFM, CPA, CFE, CIA, CISA, CBM

Edward J. McCracken

Donald F. Killion, CMA

Mary Ann F. Barker, CMA, EA

John C. Macaulay, CMA

James R. Romesberg

Evan Scarbrough, CPA

William R. Smith

Tax-Deductible Contributions Received in 2022

Designated to IMA Student Leadership Conference

Eric D. Weedon

Rollin D. Brewster, CMA

Felix Affoh Bannerman

Edward Marcelino

Erasmus

Shauna Aryee

Anindya Bagchi, CMA, CSCA

Jonathan Camacho, CMA

Loutfi K. Echhade, CMA, CFM, CPA, CFE, CIA, CISA, CBM

Monica A. Zillman, CMA

Bryan D. Barr, CMA

Daniel F. Cleary, CMA, CPA

Stephen P. Donahue, CMA, CPA

Manjunath Devaru Hegde

Karvol Karlos Mackey, CMA, CPA, CTP

Catherine B. Long, CMA

Richard T. Brady, CMA, CGFM

John B. Dever, CPA

Andreas Udbye

Thomas G. White, CMA

Srinivasan Krishnasawamy, CMA, ACA

Brian D. Edwards, CMA, CPA

Xiaohong Huang, CMA

Abdulaziz Ashur Said, CMA, CFM, CPA, CFA

Kareem Nuseibeh

Jacklynne Fair Sy Cabigunda, CMA

Michelson Pierce Kohls, CMA, CPA

Daniel F. Viele, CMA, CPA

Cherryl Almazan Tolentino, CMA

Noman U. Haq, CMA, CFM

Veronica Alexander

Esam Ziad Taan

Patrick A. Haggerty, CMA

Nicole J. Olesen, CMA, CPA

Bruce E. Willman, CMA, CFM

Kristi Anne Kemple

Mark H. Komatsu-Yonezawa

Katherine Sheena Tugade, CMA

Troy K. Senter, CMA, CPA

Anthony P. Pencek, CPA

Mark C. Woodbury, CMA

Derek McSpadden, CMA

Joseph J. Mesquita

Scott G. Davis, CPA

Joseph M. Hargadon, CMA, CPA

Sean M. Phillips, CMA, CFM, CPA

Ntshana Jim Matsemela Jr.

Faizan Ashraf, CMA

Kaneez Zainab Jamal

John C. Macaulay, CMA

Shirley J. Daniel

John E. Hetrick, CMA

Anthony N. Caspio, CMA

Hadassah Baum, CMA, CPA, CAE

Carlos Eriel JimenezAngueira

Kristine K. Parsons, CMA, CFM

Anand Satchit

Jammalamadaka, CMA, FCMA (India)

Tomas Raymond Martinez, CMA

Lisa S. Pendergrass, CMA, CPA

Joseph D. Nycum

Megan J.F. Will, CMA

Hassan Abdulrahman A. AlShahrani, CPA

Louise E. Crider

Ahmad Almaie Sr., CDP, PMP

Christopher E. McCoy, CMA

Raymond H. Peterson

Thomas Lenin, CMA, CPA, CITP, PMP

Tax-Deductible Contributions Received in 2022

Designated to IMA Century Student Scholarship Fund

John C. Macaulay, CMA

Daniel Christopher Miller

Tax-Deductible Contributions Received from January 1, 2023, to April 30, 2023:

Tax-Deductible Contributions Received in 2023 Designated to IMA initiatives and its overall Annual Giving Campaign

Zach James

Jim Asperger

Tax-Deductible Contributions Received in 2023 Designated to IMA Leadership Academy

John T. Powell, CPA

Sharon N. Griffith, CMA

Joseph Lubanski, CMA

George S. Maniatty Jr.

Rajkumar Patra, CMA

Beaatrice QuintanillaAbercrombie

Stefano Bastianetto

Debra Crutchfield

Kelly M. Anderson, CMA, CPA

Renata T. Serban, CMA, CPA

Gloria Gasgonia

Robert Levy

Nargiza Rakhmonova

Premchand Muraleedharan, CMA

Carlo Martin Vallone

Tapas Ranjan Swain, CMA, PMP

Haitham Essa, CMA

Elizabeth Gibbar, CMA, CPA

Presanna Narayan

Hussein Kh. M. Shehadeh, CMA, CSCA, CPA

Clarence Edward McFadden II

Rohidas Nagappa Moger

Larry Dodd

Sridhar Sethuraman, CMA, ACMA (India)

Srikrishna Mankal, CMA

Sara Farid, CMA

Robert M. Tobben, CPA

Kiran Krishna Kumar, CMA, CSCA

Nathan L. Malone, CMA

Arthur E. Campbell, CMA, CPA

Philip A. Zammataro Jr., CPA

Brandon Pfeffer, CMA

Jacob Wolstenholme

Dmytro Ivchenko, CMA

Khalifa Ahmed Almansouri, CMA

Ronald D. DiMattia, CMA, CPA

Lynette Pebernat, CMA, CFM, CPA, CITP

Tax-Deductible Contributions Received in 2023

Designated to IMA Memorial Education Fund, Inc.

Scholarship

Louise P. Wong

Robert A. Gunter, CMA

Joseph Lubanski, CMA

Nicos C. Kacoullis

Alma Kuttner

George S. Maniatty Jr.

Gloria A. McCartney, CMA, CPA, CISA

Hazem Khalil El Haj Khalil, CMA

Rickey Coslett, CMA

Harshi Motwani

Ann C. Dzuranin, CPA

Richard Hoyt Reginald

Brooks W. Kelley, CMA

Kelly M. Anderson, CMA, CPA

Beverley A. Brooks, CPA

Terri A. Chepregi, CMA, CPA

Edward H. Hodge, CMA

Tawanda Jera, CMA, CSCA

Gloria Gasgonia

Premchand Muraleedharan, CMA

Syon Niyogi, CMA

Jack L. Winstead, CPA, CISA

Barry J. Nathan, CMA

Elizabeth Gibbar, CMA, CPA

Erwin Melger, CMA

Dinesh Pandurang Raorane, CMA, CSCA

Joe Seltz, CMA, CPA, CIA, CFE

Hussein Kh. M. Shehadeh, CMA, CSCA, CPA

Christoph Dopf, CMA

Larry Dodd

Viktor Lavrenyuk, CMA

Sunil S. Deshmukh, CMA

Srikrishna Mankal, CMA

Sara Farid, CMA

Kimberly Kemp Brown

Robert H. Zaleski, CMA

Ee Oh

Robert M. Tobben, CPA

Kiran Krishna Kumar, CMA, CSCA

Nathan L. Malone, CMA

Thomas A. Rubin, CMA, CFM, CPA

William W.H. Tam, CMA

Arthur E. Campbell, CMA, CPA

Philip A. Zammataro Jr., CPA

Edward J. Furticella, CPA

Brandon Pfeffer, CMA

Jeremy A. Jenkins, CMA, CPA

Charles R. Wright, CMA, CPA

Jacob Wolstenholme

Ibrahim Omar A. Aldawsari

Hsiu Hui Wang, CMA

Dmytro Ivchenko, CMA

Khalifa Ahmed Almansouri, CMA

Varghese Kaleekal Parambil Mathew, CMA

Jaypal Jain, CMA

Ronald D. DiMattia, CMA, CPA

Loutfi K. Echhade, CMA, CFM, CPA, CFE, CIA, CISA, CBM

Surya Narayana Murthy Dantu, CMA

Tax-Deductible Contributions Received in 2023 Designated to IMA Research Foundation

Ann C. Dzuranin, CPA

William H. Black, CMA, CPA, CFE, CVA, ABV

Jack L. Winstead, CPA, CISA

Cynthia L. Preston, CMA, CFM

Jaypal Jain, CMA

Paul E. Juras, CMA, CSCA, CPA

Tax-Deductible Contributions Received in 2023 Designated to IMA Stuart Cameron McLeod Society Scholarship

Marcia M. Vinci

Robert A. Gunter, CMA

Brooks W. Kelley, CMA

Beverley A. Brooks, CPA

Il Woon Kim

David W. Skora, CMA, CSCA, CFM

Loutfi K. Echhade, CMA, CFM, CPA, CFE, CIA, CISA, CBM

Lynette Pebernat, CMA, CFM, CPA, CITP

Tax-Deductible Contributions Received in 2023 Designated to IMA Student Leadership Conference

Robert A. Gunter, CMA

Sharon N. Griffith, CMA

George S. Maniatty Jr.

Shin Won Kang, CMA

Bruce W. Runyan, CMA

Ann C. Dzuranin, CPA

Philip Modayil Ninan, CMA

Ruth A. Morgan-Brown, CMA

Kelly M. Anderson, CMA, CPA

Beverley A. Brooks, CPA

Renata T. Serban, CMA, CPA

Robert Levy

Premchand Muraleedharan, CMA

Christine Palmer Andrews

Jack L. Winstead, CPA, CISA

Elizabeth Gibbar, CMA, CPA

Lorna E. Hardin, CMA, CPA

Dinesh Pandurang Raorane, CMA, CSCA

Joe Seltz, CMA, CPA, CIA, CFE

Hussein Kh. M. Shehadeh, CMA, CSCA, CPA

Larry Dodd

Melinda Kay Radford

Christina Palestine, CMA, CPA

Sridhar Sethuraman, CMA, ACMA (India)

Robert M. Tobben, CPA

Nathan L. Malone, CMA

Richard G. Nadalini, CMA

Yu Cheng, CMA

Arthur E. Campbell, CMA, CPA

Edward J. Furticella, CPA

David Perrins, CMA

Brandon Pfeffer, CMA

Jacob Wolstenholme

Virginia D. White, CMA, CSCA

Cynthia L. Preston, CMA, CFM

Dmytro Ivchenko, CMA

Khalifa Ahmed Almansouri, CMA

Joan A. Cox, CMA, CPA

Paul E. Juras, CMA, CSCA, CPA

Ronald D. DiMattia, CMA, CPA

Loutfi K. Echhade, CMA, CFM, CPA, CFE, CIA, CISA, CBM

Tax-Deductible Contributions Received in 2023 Designated to IMA Century Student Scholarship Fund

Ronald D. Luther, CMA, CPA

D. Robert Okopny, CMA, CFE, CIA

Nashville Chapter

Paul E. Juras, CMA, CSCA, CPA

Robert Half

SF articles are in a digital format that’s easy to read, share, and print. Access SF using your mobile device. You can search content based on the topic of your choice. Read our monthly blogs, including SF Sustainability and IMA Moments.

While ethics is often thought about at an individual level, it’s crucial to consider companies’ impact on societal issues.

BY DANIEL BUTCHERWHILE NO ONE EXPECTS management accounting and finance professionals to be able to fix systemic ethical issues on their own, stakeholders—including customers, employees, shareholders, and society—do expect business leaders to address challenges such as workplace inequality to the extent that they’re able. The Conference Board, a member-driven, nonpartisan, not-for-profit think tank, regularly convenes senior executives across industry verticals in virtual and in-person conferences, asking their opinions on ethics and corporate citizenship and researching the steps the attendees are taking to drive lasting change in their own organizations and communities to work toward a more just and civil society.

Chuck Mitchell, executive director of content quality at the Conference Board, argues that leaders have both a moral obligation and a business imperative to address environmental, social, and governance (ESG)—as well as economic—threats to achieve a sustainable business model providing prosperity for all. Objectives include opening equal opportunities in education, workplace advancement, upward mobility, and wealth creation in the context of benefiting the business.

Mitchell stresses that social justice and corporate citizenship aren’t about altruism or being good for goodness’s sake. Finance leaders can help to make the business case for it to be driven from the top down as part of the organization’s long-term strategic plans.

“There’s such an acute awareness of issues around civility, justice, equality, and equal opportunity and a change in the attitude of a workforce that’s looking for businesses to lead in these areas,” Mitchell says. “Even though there’s that realization that now it’s part of corporations’ responsibility, the first issue that one has to overcome is that there’s still a perception out there that there’s a trade-off, sacrificing profit for social good, and that simply isn’t the case—there’s enough data out there to show that you can do both effectively, and, in fact, if you take care of the community, the business, in some instances, will take care of itself.”

Conference Board research shows that an overwhelming percentage of employees want their organizations to be engaged and to speak out on social issues, especially around gender and equal pay, as well as, to a lesser extent, race.

“So if you’re head of the finance function or if you’re managing people, the most important thing is to find out what issues are on [employees’] minds and that they feel the company can do more, both internally and externally, to address issues of equal opportunity,” Mitchell says. “It’s really about taking care of the overall well-being of your staff, listening, and getting input from your team members and those that you manage, being very open and transparent and trying to understand what issues they have [top of mind].”

After listening to the issues that matter to employees and other stakeholders, a strong leader can help the finance function to lead by example in being advocates for ethics and corporate citizenship. Mitchell suggests that leaders can begin by recognizing that there’s probably been inequality of opportunity within the organization and across the profession for a long time. Now finance leaders and hiring managers need to address it.

“If you can start…building equal opportunity within your own function, then you don’t have to wait for the headquarters to lead,” Mitchell says. “Individual leaders within their function can take that

responsibility, and it really starts with the recruitment process, making sure that you’re looking at a diverse slate of candidates and that equal opportunities are given for internal promotion opportunities from within, and that the career needs of minority staff are being met through mentoring.

“It’s not going to be solved all at once, but you can start with small steps, even within your function, and it really starts with making sure that the recruitment pipeline is diverse—you have to have a diverse slate of candidates for each open position, and the same goes for internal promotions,” Mitchell says.

“On an individual basis, there’s a lot that a CFO, the head of a function, and managers can do with their own teams, and as long as those conversations are open, transparent, and honest, it’s going to work.”

Mitchell says that becoming a socially responsible company requires thoughtful discussions among leadership during the strategic planning process informed by both financial and nonfinancial ESG metrics. After leaders agree to a plan for which social issues to address and how to do so, the next step is internal communications to get employee buy-in, establishing a mission and sense of purpose across the organization.

“You don’t just say, ‘We’re going to be socially responsible’ and then do it piecemeal,” Mitchell says. “It has to be a strategy that’s embedded across the enterprise, from the board and the C-suite to middle management and individual contributors.”

For clarification of how the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice applies to your ethical dilemma, contact the IMA Ethics Helpline.

In the U.S. or Canada, dial (800) 245-1383. In other countries, dial the AT&T USA Direct Access Number from www.business.att.com /collateral/access.html, then the above number.

The IMA Helpline is designed to provide clarification of provisions in the IMA Statement of Ethical Professional Practice, which contains suggestions on how to resolve ethical conflicts. The helpline cannot be considered a hotline to report specific suspected ethical violations.

The Conference Board is careful to emphasize that prioritizing social justice and corporate citizenship isn’t just the ethical course of action but it’s also in organizations’ best interests. More investors are now seeing it as a road to profitability and long-term sustainability, not a separate ethics issue.

Mitchell acknowledges the validity of looking at these issues through an ethics lens, but it’s hard to separate that view from business imperatives without weakening the sense of urgency or motivation to act. He cites the diversity, equity, and inclusion function, which is still battling the idea that it’s an add-on that’s somehow separate from a company’s core business.

“I get a little bit concerned if you separate social justice issues and put them in an ethics bucket, because the essence of what we see from these CEOs, CFOs, and other conference participants, from our data, they tell us that it’s very much a business decision,” Mitchell says. “Yes, it’s the right thing to do, but it’s all part of doing business—this whole social justice and corporate social responsibility push shouldn’t be a separate vision from the business; it’s part of it, and one has to do the cliché ‘walk the talk’ to preserve and enhance the organization’s reputation.” SF

Daniel Butcher is the finance editor at IMA and staff liaison to IMA’s Committee on Ethics. You can reach him at daniel .butcher@imanet.org

Accountants with a strong business partner mindset might face identity-related challenges when confronted with strict productivity measures.

BY LUKAS GORETZKI AND JAN A. PFISTERMANY PROFESSIONALS ARE challenged to improve their productivity and provide quantitative evidence to manage and make visible their productivity gains. For accountants, this can lead to a dilemma. On the one hand, they try to establish themselves as strategic advisors and partners for business managers. On the other hand, they’re under increasing pressure to perform their tasks in cost-efficient ways.

Company efforts to streamline accounting processes through automation, augmentation, and the elimination of redundant activities often result in the rearrangement of accounting work through outsourcing or the creation of shared service centers—accompanied by a growing demand for accountants to quantitatively prove their productivity.

In this context, we had an opportunity to explore how accountants designed and implemented a new performance measurement system to assess their own productivity, a phenomenon that hadn’t yet been studied in depth. Our study, “The productive accountant as (un-)wanted self: Realizing the ambivalent role of productivity measures in accountants’ identity work” (Critical Perspectives on Accounting, August 4, 2022, bit.ly/3NfMUOl), examined the question: How do accountants experience and respond to increasing productivity pressure and a corresponding measurement regime monitoring their work?

We traced how accountants in a fast-growing multinational technology company faced the challenge of dramatically increasing their productivity and presenting constant improvements through strict measures. At first, the accountants were open to the productivity challenge and willing to demonstrate their performance through the newly developed metrics. Over time, however, they realized that subordinating themselves to those metrics would downgrade what they do and who they are (i.e., their occupational identity).

The accountants in the case company had developed a business partner identity built on a strong sense of strategically performing important and complex expert work that made a significant contribution to management. Their challenging role implied that they often

needed time and flexibility to dive into and solve difficult accounting problems that were relevant for managers (e.g., integrating newly acquired companies or designing complex deals with customers).

The emerging focus on productivity measures, however, meant that processes needed to be streamlined and ideally standardized to be performed in an increasingly cost-efficient way. The company thus experimented with accounting and control tools (e.g., activity-based costing supported by detailed time tracking). To ensure that the new tools could work properly, accountants needed to meticulously track their activities and tag them according to predefined categories.

This conflicted with their understanding of their complex and multifaceted role as business partners, which they felt couldn’t easily be expressed in standardized units. To deal with the productivity challenge, accountants engaged increasingly in activities aimed at innovating their work. Thus, endeavors to standardize their tasks resulted in more nonstandard project work. Although their work increasingly shifted toward process innovation tasks, the new productivity measures focused on capturing routine activities. Paradoxically, the increasing productivity pressure caused by the measurement and shift in the nature of work tasks made productivity measurement more difficult.

Accountants eventually felt increasingly uncomfortable expressing their performance through the new measures. This

discomfort was further intensified by accounting managers’ increased focus on productivity as a key performance indicator. The accountants in the case company eventually started to resist productivity measurement and to champion a more qualitative assessment of their work based on performance narratives.

While productivity measures have potential benefits, our study demonstrated that predominantly relying on them might have problematic consequences for employees. The measures can produce a false sense of clarity and direction for accountants’ performance. Strong reliance on those measures can in this sense create the impression that what counts for an accountant to perform well is to emphasize productivity over other criteria (e.g., internal customer satisfaction).

Also, productivity measures are incomplete representations of accountants’ performance, making the resulting transparency and comparability of those measures problematic. While highlighting specific criteria that are amenable to quantification, productivity measures disregard performance dimensions that accountants (and managers) might consider more important for the business partner role but are potentially more difficult to measure. Over time, a strict focus on productivity measures thus creates the risk that those performance dimensions lose relevance.

Senior practitioners (e.g., CFOs or accounting managers) must be cautious when designing performance measures for accountants and consider the developments that the accounting occupation has undergone in the last several decades. The accounting profession has worked hard to establish its members as professional knowledge workers who deal with complex strategic and operational issues in organizations.

Drawing solely on productivity measures might not adequately consider those developments and present accountants with challenges that can render fragile their identity as business partners. This can eventually lead to frustration or resistance against performance measures, as the study shows.

More broadly, the findings of the study have implications for the relationship between the design and use of productivity measures and any occupational identity. As the case study demonstrates, productivity measures are unable to capture the full complexity and variety of tasks. The ability to quantify performance might thus come at the expense of unquantifiable elements that employees consider as meaningful or prestigious work and that motivate them the most.

Even more, performance measurement might crowd out employees’ aspirations to perform such meaningful work. Aligned with the phrase “what you measure is what you get,” the focus of employees might turn to the measurable activities and move away from those

strategically and operationally important tasks that aren’t well captured by the measurement system.

Senior managers should keep employees’ occupational aspirations in mind and remain alert to the limits of measurement. This means creating a performance culture where productivity measures aren’t blindly followed as pure and objective truth but where everyone is encouraged to remain critical of what the measures track, incentivize, and motivate. This is important to avoid dysfunctional countereffects of productivity measures, like employees’ demotivation and perception of being unvalued, unfairly judged, or hindered in their occupational aspirations.

Ultimately, productivity measures are a tool that can’t be taken at face value but rather as input for discussion and reflection. Otherwise, important productivity-enhancing activities might be diminished, and productivity measures can paradoxically create a reverse effect of what they’re intended to do. SF

Lukas Goretzki is professor of management accounting and control in the Department of Accounting at Stockholm School of Economics. He can be reached at lukas.goretzki @hhs.se

Jan A. Pfister is associate professor of management accounting at Turku School of Economics and an affiliated researcher at the House of Innovation and the Mistra Center for Sustainable Markets at Stockholm School of Economics. Jan can be reached at jan .pfister@utu.fi

Affordable automation tools and effective implementation strategies can strengthen duty separation.

BY WASSIA KAMON, CMA, CPAMOST SMALL BUSINESSES STRUGGLE TO maintain adequate separation of duties in their accounting functions due to their limited staff. Often only one or two people handle all the accounting and treasury tasks of the business, with little to no oversight. This leads to situations where the same person could commit and conceal fraud or make significant errors that go undetected. Fortunately, affordable automation tools are now available that provide small businesses with solutions to mitigate such concerns.

The separation of duties (SoD) principle is an internal control that recommends that the bookkeeping, custody, and authorization aspects of a business transaction be handled by different staff members. But this involves a minimum of three employees working in an accounting department of any given business, which often isn’t realistic for smaller companies.

Small businesses are characterized by tight budgets, lean operations, and limited resources. Therefore, internal controls are often an afterthought, as employees wear multiple hats to get things done. The challenges of hiring and retaining employees since the COVID-19 pandemic are making it worse.

Without proper checks and balances, mistakes can easily go unnoticed, and dishonest employees may take advantage of the situation. As a result, the same person can:

1. Set up a new vendor in the accounting system (including, name, address, or payment information).

2. Record the invoice charges and description.

3. Issue and authorize payment.

4. Reconcile bank statements.

This clearly goes against SoD principles, making smaller companies more susceptible to fraud. According to the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), the lack of internal controls, such as SoD, accounts for one

third of fraud committed. Small businesses are the most vulnerable, with 43% lacking proper internal controls and 60% never recovering their losses from fraud (see the ACFE’s 2020 Report to the Nations, bit.ly/3iRQldN).

With the help of technology, small businesses can now better mitigate these risks. Accounting automation tools now provide built-in checks, balances, and audit trails at affordable rates for small businesses. Though only one or two people will continue doing the bulk of the accounting functions, business leaders and owners can have greater transaction visibility during the approval and review process of accounting transactions. The following are three automations that can help small businesses mitigate risks associated even without proper SoD and optimize their business processes at the same time.

1. To ensure SoD in the accounts receivable process, the employee creating and sending the customer invoice should be different from the employee collecting and recording the payment for that invoice. Whenever those tasks are handled by only one person, automation software should be implemented.

Accounts receivable automation software streamlines invoicing and payment collection. Invoices can be automatically generated and sent to customers as soon as

the sales process is completed. Due dates and payment reminders are also sent automatically. Payments from customers are matched to the transactions received by the system, with often no manual input needed from accounting staff. System audit trails are available in case auditors or business managers want to review manual overrides.

2. To ensure SoD in the expense reporting process, the employee requesting the expense reimbursement should be different from the employee recording and disbursing the respective payment. Whenever those tasks are handled by only one person, automation software should be implemented.

Expense reporting tools allow all employees to submit their own expense reports directly into the system, along with the appropriate receipt. These expenses are then reviewed by their managers and disbursed to their preferred method of payment, with little to no intervention from accounting staff.

3. Accounts payable automation software works almost the same as expense reporting tools, with the added benefits of validating vendor charges, reducing the risk of duplicate payments, and taking advantage of early payment discounts.

Beyond error and fraud prevention, the insights businesses get after automating routine accounting tasks are phenomenal in terms of transparency and timeliness of relevant information. Invoice exception rate, early payment discounts cap-

tured, and late payments rate and penalties are just a few key performance indicators that can be effectively tracked through an accounts payable automation tool.

Finding the right accounting automation tools is just the first step; the next and equally critical step is implementation. Many underestimate the amount of planning involved at that stage, resulting in missed opportunities to maximize the tools’ benefits. Small businesses with limited IT resources should consider the following tips as they embark on their automation journey.

1. Start with a thorough assessment. Existing processes, workflows, and challenges should be thoroughly assessed before starting any search for process improvement tools. Ideally, the desired SoD should be mapped out among existing staff, managers, and leaders so that the search for an adequate tool is effective.

2. Leverage current resources. If the business already has an accounting system, look for automation solutions that easily integrate with it. For example, well-known small business accounting systems, such as QuickBooks and Sage, have app marketplaces that list several resources that integrate seamlessly with their core accounting systems. These integrations usually allow for automatically syncing data between systems and reducing the

need for repetitive manual entries.

3. Add structure early. Determine the main objectives and budget and establish a well-defined selection process that has questionnaires that all vendors must complete. Having a predefined list of items that should be covered during the demos is also helpful.

4. Recruit adequate help. Consider which efforts will be led in-house vs. external consultants. Hiring temporary staff to assist during implementation is often beneficial.

5. Make room for potential difficulties. Add some buffers to your project timeline and budget. There’s always something that may go wrong when implementing a new tool. But with proper planning, implementing such helpful technology shouldn’t be painful.

Small businesses face many challenges when it comes to maintaining adequate internal controls, particularly regarding SoD, due to limited resources. Automation tools can help mitigate these concerns, providing businesses with affordable options for streamlining their accounting processes. By automating key accounting functions, such as accounts payable, small business owners and accountants can improve their internal controls and reduce the risk of fraud, while saving time and resources. SF

FOR FINANCE PROFESSIONALS TO PERFORM EFFECTIVELY, they have to understand their company’s goals and be able to explain what financial data means for the pursuit of those desired outcomes. Storytelling isn’t just about crafting a compelling narrative from data but also the ability to communicate effectively so that leadership and stakeholders know how much progress the organization is making toward achieving its strategic objectives.

In a conversation with Strategic Finance, Jenn Ryu, CFO of global consulting and staffing firm RGP, and Efrain Rivera, senior VP and CFO of Paychex, a human resources, payroll, and benefits platform provider, talk about the work that accounting and finance professionals perform, starting with analysis and interpretation to get an accurate view of the data, then weaving an insightful, coherent narrative that ties into the organization’s strategic plans and goals.

SF: What are the most important elements of effective storytelling in a professional context?

Ryu: The most important building blocks of effective storytelling are knowing exactly what story you want to convey— the what; understanding your audience so you know the best way to deliver the story—the how; and finally, what you want your audience to take away—the answer to the question “so what?” From a CFO’s perspective, the core components of a good story often originate from financial and operational insights that hinge upon the effective use of data and analytics. Organizations across every industry are investing in finance transformation initiatives to power business momentum and gain valuable insights, from unifying enterprise-wide data to deploying cloud and intelligent automation solutions.

But data and numbers only tell your audience so much on their own. Effective storytelling requires a sound understanding of your audience’s existing perceptions or awareness,

what drives their decision making, and the level of detail that will resonate with them. We must be able to understand the context, adjust the message, and filter out irrelevant information. Context is a vital element of effective storytelling, as dollar impacts and percentage growths may be perceived differently, especially for an emerging service or market.

Rivera: The first important building block of a good story is understanding what the numbers are actually telling you. That information has to be accurate. Secondly, beyond just accuracy, you have to interpret what that information means for the organization.

Let me give an example of how we can have the same top and bottom line, leading to very different conclusions. If you put together a budget that’s correct in totality, meaning the total revenue, total expenses, and net income are correct, then there could still be a lot of variations in between the components of the budget. This is a simple example of the value of variance

analysis. If we don’t understand what’s happening in the components of the budget, then we can miss a lot of what’s going on in the business. As finance professionals, we need to analyze the details at enough depth to truly understand the story that the results and variances are telling.

SF: What are best practices for improving accountants’ ability to communicate effectively and telling a captivating story?

Rivera: The first point that’s really critical is the ability to articulate your story clearly. Every time you tell the story by painting a clearer explanation of results or projections, you’re building and developing your communication skills. Many audiences may not understand all of the financial implications of the data, but you can drive a particular point home by using the right analogies. When you can connect with an audience by painting a picture of something that’s relatable, they can track what you’re saying more easily.

Secondly, you need to rehearse. When I speak onstage, most people think I’m speaking extemporaneously because I have a conversational tone and don’t use notes. In reality, I’ve rehearsed exactly what I want to say seven to 10 times.

Third, it’s important to find some point of connection with the audience. Good, effective speakers like their audience, understand them, and work to build a rapport with them.

If you’re trying to have a conversation with the audience, then make your presentation about them, not you. You need to recede into the background and let the information go to the foreground. People feel affirmed and heard when they’re part of the story, rather than being lectured to.

Ryu: It starts with finding the right narrative for the situation and the audience. Ask yourself what you ultimately want your audience to come away with, determine the right amount of relevant details to provide, and identify the decision points that will lead to agreement. To prioritize

“Many audiences may not understand all of the financial implications of the data, but you can drive a particular point home by using the right analogies. When you can connect with an audience by painting a picture of something that’s relatable, they can track what you’re saying more easily.”

—Efrain Rivera

the information that’s most relevant to your audience, you must consider each individual’s priorities, their backgrounds and knowledge of the material, and the questions they’re likely to ask.

Effective communication and captivating storytelling require lots of preparation and practice. Even more importantly, honest feedback from a trusted mentor or peer will add tremendous value in one’s journey to become an effective communicator.

SF: What aspects of the CFO’s role and responsibilities require storytelling skills or are made more effective by honing those skills?

Ryu: CFOs have always had to be good at translating data into insights and stories that illustrate value, but it’s becoming an even more important skill set as CFOs increasingly operate in a storyteller role. The responsibilities of the CFO have changed greatly over the years— we’ve taken on more of a role as value creators within organizations. Many CFOs are leading transformative initiatives that require an ability to convey to business teams and partners how the transformations fit into company strategies and operational insights in ways that extend beyond traditional financial communications.

The goals of every CFO should be to establish trust, build consensus, and drive strategic decision making. Essential to each of these goals is the ability to boil down insights into a persuasive business narrative while focusing only on what’s most relevant to your audience and what they care about most.

Rivera: As you hone your communication skills, there’s simply no substitute for storytelling consistently. Throughout your week, you can always find opportunities to share your ideas, and your storyboard is the financial information you present.

Most people have an innate ability to be a storyteller but simply don’t practice it enough. For example, I may have an innate musical ability to play guitar, but if I never practice,

then I won’t be able to play a song anyone would want to listen to. If you look [for chances to tell relevant stories], then there are always [growth] opportunities for those who are willing to learn and practice their skills.

SF: How can professionals focus on improving their storytelling to provide a boost to their career?

Ryu: It’s becoming increasingly important for accounting and finance professionals to develop effective communication skills that they can leverage in daily interactions, especially considering the rapid pace of change we’re all experiencing in today’s environment. Professionals at every level and function can benefit from the ability to deliver vital information to their colleagues in a concise and engaging manner. Being great at data analytics can only get you so far in your career if you can’t make the insights known and easy to digest for your executive team and other key stakeholders to drive better decisions and business outcomes.

SF: How can management accounting and finance professionals cultivate their creativity, communication skills, and storytelling abilities in a numbersdriven profession?

Ryu: Accounting and finance professionals can find many resources on this topic in online classes on platforms like LinkedIn and MasterClass, and through professional membership associations such as IMA® [Institute of Management Accountants]. But the best way for accounting and finance professionals to hone these important skills is to gain practical experience by presenting in real-world settings to mentors and colleagues.

Professionals can also develop these skills during everyday interactions, not just important presentations and meetings. Effective storytelling requires you to listen to colleagues, show empathy, take feedback, and constantly adapt your approach as you learn.

Rivera: Although we’re surrounded by numbers, those numbers on their own don’t tell a story for most audiences. They’re simply an input to the story. Our creativity comes in as we determine how to effectively communicate what the numbers are saying in a compelling way that’s meaningful for your organization.

Naturally, we shouldn’t give the exact same presentation to the accounting team as we’d give to the marketing team or the board of directors. When you consider your audience, think about an analogy that fits the [background and knowledge of that] audience. If you aren’t sure, then ask others if your understanding is correct and if your story conveys the desired meaning to the audience.

SF: How important is it for CFOs to acquire data visualization skills and use storytelling to convey the strategy to the organization’s key stakeholders?

Rivera: Data visualization techniques help to reinforce the points being made. There’s an excellent book written by a professor at Yale University, Edward Tufte, called The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Although it’s about statistics and data, the book reads like an art book with a display of numerical, graphical, and visual displays. Tufte believes that presenters can display numerical information so it can look like art and hammer home the point they’re trying to convey.

It’s critical for each slide to bolster the speaker’s story in a concise way. Some people put up complex graphs with tons of information and think that everyone can follow them, but often the audience can’t.

Think about how you display data and make it simple, whether it’s a line or bar graph or pie chart, and find ways to powerfully support the narrative. As you do this more, you’ll get better at choosing the visual display to drive your point home.

Ryu: Organizations are placing more priority on analyzing their business to gain the insight they need to make strategic decisions about how they can grow, whether that

means expanding their customer base or reevaluating the products and solutions they offer. Investments in [financial planning and analysis (FP&A)] and data analytics tools equip finance teams with the abilities to drill down, consolidate, and visualize data instantaneously, and, as financial leaders, we must be able to use all the tools at our disposal to create an effective narrative. Strong creativity, communication skills, and storytelling abilities ultimately help us draw connections between these finance transformation investments and how the data-driven insights they uncover are impacting opportunities ahead to create long-term value.

SF: How do you decide what medium is most appropriate to convey your story or what multimedia elements can best enhance your presentation?

Ryu: One should always consider their audience when choosing the appropriate medium to convey their story. In general, less is more. Use simple charts, graphs, and images to captivate your audience. Overburdening an audience with too many words or numbers tends to create distractions and diverts their attention

from listening to you to reading the presentation.

Rivera: When deciding what elements to use, leverage whatever you believe clearly conveys the idea you’re trying to present but never show a collection of tiny lines of information. When I first started at Paychex, I used to provide more detailed financials, but I found for most audiences, that level of detail wasn’t important. For most groups that you present to, you’re looking to convey key points to inform their judgment. That’s the art of the discussion: picking the right set of visuals.

For me, I’ve found that transportation visuals resonated since, like a business, vehicles move from one point to another. Find an element like a photo, movie clip, or sound clip that fits your presentation. If it works, then use it.

SF: What are examples of core messages that finance leaders should seek to convey with their stories?

Ryu: The purpose of a good story from a financial leader’s perspective is to create connective tissue between data, the organization’s strategy, and the messages that the

CEO and [the rest of] the C-suite are delivering. Credibility is of the utmost importance for CFOs, and it’s up to us to develop a financial narrative that threads the needle between strategy and performance data, and as a result, leading to calls for action.

Rivera: The story lies within the meaning of a set of financial data. Storytelling for finance professionals isn’t just a compelling narrative woven from data, but also the ability to communicate effectively so the organization knows how it’s tracking against its goals and where it is on the journey. Spending sufficient time on analyzing data creates the ability to craft a compelling narrative.

Likely the most important set of messages we’re trying to convey is where we are currently, where we’re going in the future, and then what challenges and opportunities lie on our journey ahead. If you can state those things clearly to any audience, then you have the making of a good presentation.

SF

“Being great at data analytics can only get you so far in your career if you can’t make the insights known and easy to digest for your executive team and other key stakeholders to drive better decisions and business outcomes.”

—Jenn Ryu

BY THOMAS G. CANACE, PH.D., CPA; AYAZ JAFFER, CPA; AND PAUL E. JURAS, PH.D., CMA, CSCA, CPA

BY THOMAS G. CANACE, PH.D., CPA; AYAZ JAFFER, CPA; AND PAUL E. JURAS, PH.D., CMA, CSCA, CPA

The CFO and finance team are well positioned to mitigate the prolonged supply chain disruptions that have challenged cash flow and profitability.

ollowing the turbulent years of supply chain disruptions and product shortages during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, CFOs and companies alike have wondered when the most damaging effects will finally be in their rearview mirror. Yet supply chain problems have continued to intensify, leading to an inability to meet the pent-up customer demand that grew during the pandemic and stymying companies’ revenue growth.

CFOs possess the acumen to serve as valuable partners in the operations of their businesses and are uniquely positioned to act as collaborators and integrators throughout their organizations to counter these challenges with solutions. To enable their business partners to envision the future, they use data analytics to make predictions, gain insights, and guide strategic and tactical decisions throughout the business. Thus, CFOs are partners, catalysts, and visionaries who serve as agents of change—consistent with competencies embodied in the IMA® (Institute of Management Accountants) Management Accounting Competency Framework that finance professionals need to remain relevant in the Digital Age (bit.ly/39UFlc1).

In the face of these recent supply chain issues confronting global trade, CFOs have had no option but to adapt their businesses to yield positive results. What actions are they taking? We spoke with several CFOs to gain insights into the ways they’re addressing supply chain disruptions. There were some recurring themes of the short-term and long-term best practices they’re employing to adjust their supply chains. Table 1 summarizes key insights from these discussions.

First, while CFOs acknowledge the need to bring production closer to their customers, they also know this takes

time. Yet investors and boards of directors expect immediate results. Thus, CFOs are seeking changes to their shipping logistics by renegotiating and expanding contracts with third-party logistics companies as an efficient option for getting product to customers.

Second, while they see supply chain automation as important, they also concede it will take time and investment to build the technology into their operations. In the short term, they’re focusing on integrating more data analytics into their financial analysis so that the finance team can employ the right key performance indicators (KPIs) to help run the supply chain. Yet a common stumbling block in building data analytics capabilities is developing a clear return on investment, so CFOs are keen to point out that their focus must be on providing leading indicators that equip them with the right capabilities to drive strategy through insights and analysis.

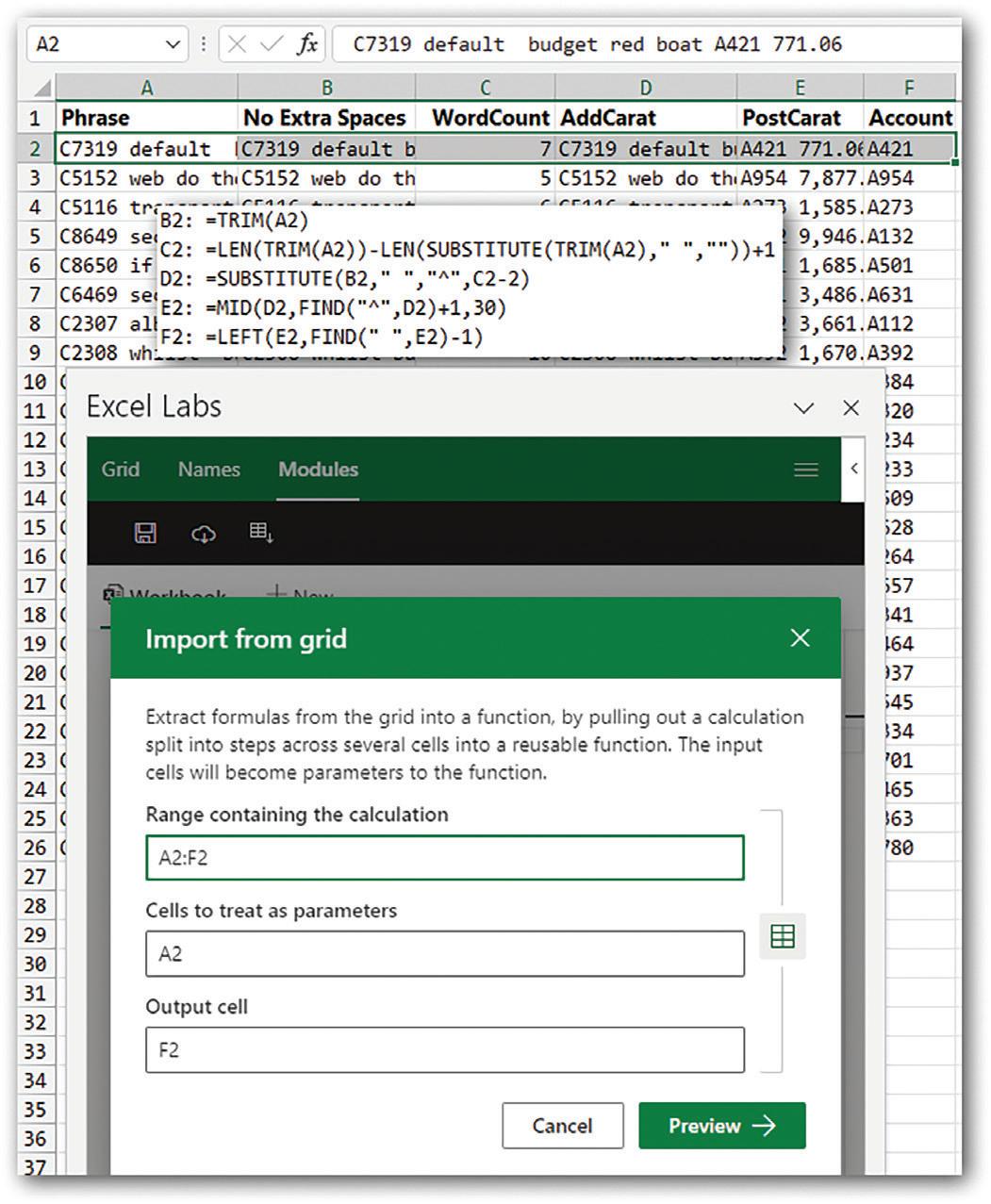

Key metrics they cited include the cash conversion cycle, the sea-to-air ratio, the amount of inventory on hand, and distribution and storage costs as a percent of sales. As shown in Figure 1, the cash conversion cycle (CCC) is an integrative tool that combines three metrics to assess a company’s efficiency in selling inventory, collecting receivables, and making payments as a broad indicator of actions needed throughout the business to improve cash flow.

The sea-to-air ratio, which measures the proportion of ocean freight shipments vs. air freight shipments (in dollars and weight), has recently become a focal point in the supply chain. One CFO explained the difficulty companies have in balancing between these two modes of shipment in the current supply chain climate. While the CFO cited a company goal of pushing the U.S. ratio to 50:50, the company currently ships more than 90% by air and the remainder by sea from the production facility to the U.S. distribution centers to maintain inventory to meet customer demand.

Although the high level of air travel is costly, there’s no end in sight due to shipment delays. For instance, the CFO mentioned that sea travel from overseas to New York has increased from a pre-pandemic average of 60 days to

■ Change shipping logistics

■ Integrate data analytics for financial analysis

■ Focus on customer-specific product order needs

■ Balance between JIT and keeping inventory on hand

■ Bring production closer to customers

■ Automate supply chain

■ Move to JIT inventory systems

95 days, while it takes only a few weeks to get product into the United States by air. The CFO further elaborated that “to compete within a tight supply chain, we’ve had to make tough decisions to just do air travel because we need product or else we lose sales to the competitor. We have to carry some inventory.”

Third, CFOs mentioned the need to focus on their major customers and emphasized that supply chain solutions can’t be a one-size-fits-all approach. Thus, they may need to employ different shipping logistics for customers based on their order sizes, order frequency, product sizes, etc. For instance, customers that buy product in bulk at routine intervals may need a shipping logistics plan that’s in close proximity to manufacturing or product-sourcing operations.

Finally, CFOs noted that recent supply chain disruptions have been a clear lesson to balance between Just-in-Time (JIT) inventory and keeping inventory on hand. JIT inventory systems have been the goal in recent decades because they provide the benefit of reduced working capital investments in inventory. Yet companies relying on JIT have been forced to turn away customers as the supply chain became locked up in recent years. In contrast, maintaining inventory stocks ensures there’s enough supply to reduce dependence on the supply chain in the event of material shortages and shipping disruptions. One CFO we spoke with mentioned his company currently wants 90 days of supply on hand to deal with supply chain issues. Of course, this independence comes at the cost of increased working capital investments and reduced cash flow.

How can CFOs manage these consequences? This is where the CCC metric can aid decision making. As slowdowns in inventory turnover, i.e., days inventory outstanding (DIO), adversely affect the company’s ability to turn investment into cash, managing CCC places emphasis on the actions needed throughout the business to improve cash flow. For instance, to keep CCC low, increases in DIO can be

offset by managing the timing of receivables and payables— through supply chain finance arrangements or by negotiating faster collections and prolonged payments.

Recent supply chain disruptions have impacted both the top line and the bottom line—not only have materials shortages slowed production and sales to customers, but rising production and distribution costs have threatened profitability. Thus, challenges in the supply chain affect manufacturing/ operations, marketing/sales, and administrative/support functions. Such vulnerabilities have placed a spotlight on the CFO to help navigate these challenges with actionable solutions.

The 2022 report Supply Chains: A Finance Professional’s Perspective, from IMA, the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA), and the Chartered Institute of Procurement & Supply (CIPS), described the role of the finance business partner (bit.ly/3npJhLt). It noted that the need for the CFO to work as a collaborative business partner is even more urgent in a disrupted supply chain as operational managers need data to drive deeper insight and support decision making.

As integrators touching all business functions, CFOs work collaboratively as a hub across the entity. This requires a deep understanding of the commercial business model, the strategy, and the execution issues. One CFO we spoke with summarized it well, stating, “We work as business partners from quote to cash in the business,” helping align business processes from manufacturing through sale to ultimate collection.

Applying the CCC metric as an example, the CFO can work with (1) the sales/marketing team and the treasury department to improve days sales outstanding (DSO) by helping to negotiate customer payment terms; (2) the

What happened?

Reporting SCM

✱ Shipping cost trends

✱ Shipping time trends

✱ Details by customer

Why did it happen? Explaining SCM

✱ Customer order specifics

✱ Shipping modes (sea/air)

✱ Economic/ political trends

✱ Supply/demand factors

Looking back

What is likely to happen? Forecast/outlook SCM

✱ Flexible budgeting/ sensitivity analysis

✱ Changes in shipping times

✱ Specific customer needs

What should we do? Recommended SCM actions

✱ Change shipping method strategy

✱ Make decisions about optimal shipment strategies by customer

Looking forward

Adapted from Raef Lawson, “New Competencies for Management Accountants,” Strategic Finance, March 2019, bit.ly/42EwIuu

manufacturing/operations team and sales/marketing team to improve DIO by helping to speed production, distribution, and sales; and (3) the purchasing department to extend days payable outstanding (DPO) by negotiating favorable terms with vendors.

The CFO’s role as business integrator also comes to the forefront with forecasts and outlooks. The CFOs we spoke with all mentioned the need for even better forecast accuracy, which requires the CFO to talk to both the sales and production functions to avoid “ripple” effects in the business.

One way for CFOs to alleviate the supply chain bottleneck is to focus on next quarter’s sales so product managers and operations teams can meet demand with more precision. But short-term forecasting isn’t enough. Long-term forecasting has required CFOs to work across business functions in understanding the life cycle of the product, especially for newer products where managers have less experience to bank on. For instance, one CFO explained that longer-term forecasts enable the factory to know what parts and materials to have on hand for continuous production.

As companies turn to finance for answers to critical questions, CFOs recognize their leadership role in using analytics to integrate data across various business functions. Analytics help finance professionals transform data into information and actionable knowledge for decision making, and accounting and finance professionals are expected to partner in decision making and provide financial expertise to help formulate and implement an organization’s strategy.

Figure 2 considers the four types of analytics and how CFOs can add value to the entity by using historical information to embrace a forward-looking mindset when tackling supply chain issues. Consider an example where a U.S. company makes its product outside the country and must decide how to deliver goods to customers. The CFO must partner in decision making to provide solutions about the company’s shipping logistics operations to its customers. The goal is to provide timely delivery at the lowest total shipping cost in a landscape where increased shipping costs and shipping delays are major considerations.

Advantages

■ Closer to JIT (which involves less inventory investment)

■ More control over inventory

■ May increase delivery time

■ Expertise, scale, and capacity of third-party logistics provider

■ May decrease delivery time

Disadvantages

■ Fees to third-party logistics provider

■ May not be cost-effective for low-volume orders made at high frequency

■ Less control (maintain inventory at warehouse)

■ More investment of inventory on-hand

There are two shipping methods to consider. One option is to send the goods via drop shipment. In this scenario, the goods are produced at a non-U.S. manufacturing plant and then immediately packed and shipped straight to the customer in the U.S. The second option is using a thirdparty order fulfillment company based in the U.S. Here, the company contracts with a third-party logistics provider and perhaps a separate carrier. A stock of inventory is delivered to the logistics provider, which warehouses the goods, packages them for shipment, and manages the inventory. When a customer places an order, the company notifies the logistics provider, which draws the goods, packs them, and ships them to the customer. Table 2 highlights the advantages and disadvantages of both approaches.

With access to financial and cost information as well as the general ledger, the finance team is uniquely positioned to explain what happened through descriptive analytics of the supply chain. This is where Big Data skills come in handy for CFOs to maneuver through large volumes of transaction-level shipping data to create information. Analytics could include such measures as actual shipping costs and shipping days per transaction and per customer for each shipping method to examine shipping efficiency.

This descriptive information aids diagnostic analytics to explain why there are differences in cost and timing for the two shipment methods. Qualitative considerations for examining differences could include customer order specifics (e.g., order size, product type), fixed vs. variable costs, supply/demand trends, and political risk factors.

Examining the past with such quantitative and qualitative analytics opens the potential to look forward with predictive and prescriptive analytics. Predictive analytics allows the CFO to formulate an outlook for the supply chain of what’s likely to happen in future periods to provide actionable knowledge for decision making. For instance, the finance team can create flexible budgets with sensitivity

analysis about changes in customer order volumes, shipping rates, etc. Such analytics can also consider potential changes in cost structure and shipping time for each shipping method (e.g., drop shipment vs. third-party logistics).

Finance professionals can integrate descriptive, diagnostic, and predictive analytics to develop prescriptive analytics. In a supply chain context, CFOs can use the actual shipping cost and timing information, specifics from customer orders, and the predictive output from the sensitivity analysis to make decisions about the best shipping method to use for each customer. These decisions can be communicated internally and externally by explaining the financial impact on revenues, profits, and KPIs to show investors how operational cause equals financial effect. Customer-specific metrics can also be discussed to address the likelihood of positive impacts on demand and customer satisfaction.

To illustrate, let’s take a look at a real-world business example. All amounts and names have been changed for confidentiality, but the relative magnitude of amounts is representative of the actual situation.

XYZ Corporation is a company with production occurring at the manufacturing facilities of its former parent company in Asia. In early summer 2021, the board of directors recognized potential supply chain issues with meeting the demands of its large customer base in North America. In response, the board commissioned XYZ’s finance function to employ cost data for transactions occurring during the fiscal year to analyze the shipping cost structure for its top 50 customers in North America. The primary objective was for the CFO organization to use financial analytics to make recommendations for each customer about whether to ship products through drop shipments from Asia or through a third-party logistics company in North America. As it

Use the four types of analytics (descriptive, diagnostic, predictive, and prescriptive) to add value with a forward-looking mindset when tackling supply chain issues.

Use KPIs such as CCC to manage quote-to-cash cycle, including the timing of inventory turnover (DIO), the timing of payables (DPO), and the timing of receivables (DSO).

Use data analytics to measure fixed and variable cost structure of supply chain within a relevant range of activity.

Rethink shipping logistics (e.g., sea vs. air; drop shipment vs. third-party logistics providers).

Plan to invest in supply chain automation in the long term.

View members of the finance function as collaborative integrators, aligning business processes between manufacturing, sales, and purchasing.

Consider supply chain finance arrangements between buyers/suppliers/banks to lengthen the timing of payables and to speed the collection of receivables.

Integrate next-quarter sales forecast into production schedules to ensure materials availability and to meet demand with precision.

Develop long-term forecasts to consider the life cycle of your product(s) and to enable continuous production.

Strike a balance between maintaining inventory supply on-hand (as a buffer against supply chain bottlenecks) vs. increased working capital investments.

Analyze, review, and renegotiate shipping contracts.

turned out, the XYZ board was ahead of the curve on the impending supply chain issues that rose to the surface later that year.