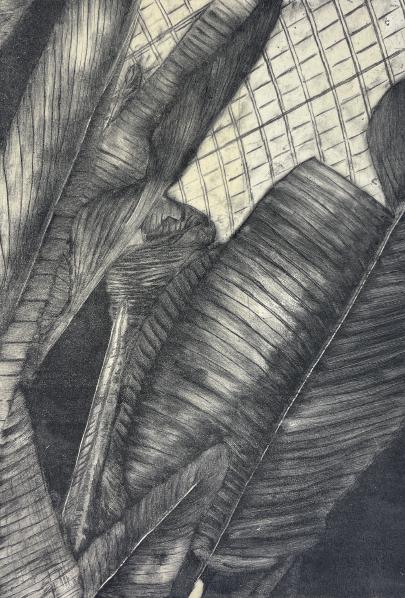

Front cover artwork by Grace Desport

Front cover artwork by Grace Desport

Principal Editors:

Serene Kong

Edith Ko

Artists:

Maggie Ruan

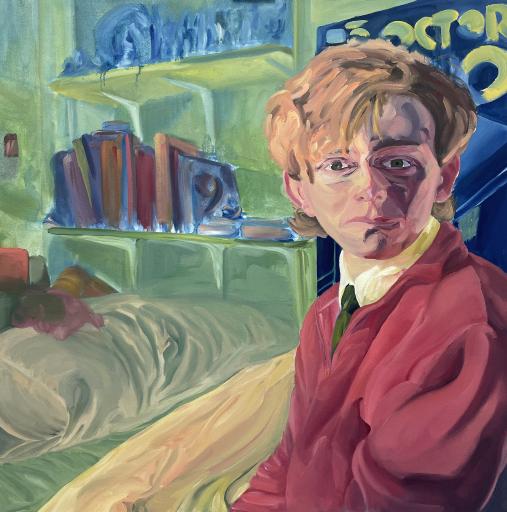

Grace Desport

Alex Vause

Arina Zenevich

Madi Spence

Isobel Legg

Writers: Amanda Chittock

Sylvia Sharp

Eryn Watson

Maggie Ruan

Katie Butler

Róísín Gleeson

Madi Spence

Edith Ko

Serene Kong

Amelia Harrison

Arina Zenevich

Serena Derby

Designers:

Serene Kong

Edith Ko

Róísín Gleeson

Madi Spence

Arina Zenevich

Serena Derby

With huge thanks to: Ms Edgar, Ms Harter-Jones, Jennifer Campbell, Abby Green

Booker Review: Wild Houses by Amanda Chittock

Booker Review: Playground by Sylvia Sharp

Greek influences by Eryn Watson

Legal lore of Shakespeare’s Hamlet by Maggie Ruan

Yayoi Kusama Phalli’s Field by Katie Butler

Interview with Ms Edgar

Time Zones – Róísín Gleeson

Centric theorems by Madi Spence

Interview with Paddy

Race against time: Covid by Edith Ko

Ethics of Clinical Trials by Serene Kong

Interview with Mr McAleese

Evolution of Women by Amelia Harrison

Climate Clock by Arina Zenevich

Interview with Mrs Hall

Interview with Miss Mounter

Interview with Gareth Barlow

Time

Ilona Maher by Serena Derby

Leaders of Tomorrow by Róísín Gleeson

US Elections by Serena Derby

Upper Sixth: A day in the life...

Dear Reader,

With this year being our final year at St Peter’s, our decision to base this year’s magazine theme on ‘Time’ stemmed from our wish to create a timeless magazine. You will find how ‘Time’ has woven throughout the arts and culture, social, science, history and politics of our lives. Assembling this magazine together with our other dedicated editors allowed all of us to combine interests and stories from the ‘Time’ before us, after us and now. Overall, creating an inspirational and meaningful project with lots of fun!

We would like to thank all the incredible writers and artists, contributing and curating a magazine with a wide selection of topics such as ‘The Legal Lore of Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet’ and ’US Election, 2024: Is it time for a change to the constitution?’. Of course, we cannot thank Ms Edgar and Ms Harter-Jones enough for their support, time and advice during this journey.

We hope you enjoy reading this!

Serene Kong and Edith Ko

When I read Colin Barrett’s Wild Houses, I was shocked by its narrative style and ‘all or nothing’ plot.

"Action, mystery, and suspense dominate the narrative while allowing for undertones of authenticity and honesty."

It captures the claustrophobia of growing up in a small town full of people that all know your name in a new and revolutionary fashion. However, the countryside setting of Wild Houses is not idyllic or serene but one of great troubles, even despite the vastness of its landscapes eclipsing violence.

The story follows the brother of a small-time drug dealer, Doll English, who is kidnapped and drawn into problems he does not initially understand. As the gravity of his brother’s mistakes are realised, he is surrounded by the company of violent and dangerous criminals. His girlfriend, Nicky, sets out to find him over the course of one fateful weekend...

The book successfully highlights a range of issues: the stark differences in how the male and female characters approach conflict, the effect of neglecting the mental health of the youth, the dangerous toxic masculinity that plagues society in underdeveloped areas and across our country as whole. Perhaps a cause of this is due to the expectations of young men in society and how damaging this can be. Barrett’s imagery of the effect on mental health caused by this is beautiful yet chilling. It is not chilling because it is extreme or overly confrontational, but because it is relatable. His experiences as a teenager are almost universally shared experiences, making you feel one in the same. So, when he is facing the chaos and adversity within the chapters of the book it suddenly does not feel like an exaggeration of feeling and highlights, with exceptional craftsmanship, the ease for the youth to be drawn into violent crime. The tactful interweaving is increasingly profound considering this is Barrett’s first novel. Literature is one of the oldest methods

of communication, Wild Houses coveys the importance of this while with the authorial debut showing the shift in literature of displaying a more complex world.

The unsettling gravity of the plot exemplifies the book in a way that would typically feel burdensome to a reader yet Barrett manages to conceal it in a blanket of warmth by showing raw, unabridged relationships. From the evolving bond between high school sweethearts, Nicky and Doll, to the complex dynamics between a wayward son and his mother, and the internal struggles of a young boy. The unapologetic validity of these relationships is refreshingly honest among a wave of hidden vulnerability in both life and literature, the illuminating way we connect - both internally and under societal rule.

While this sounds like a lot of social politics, Barrett presents this in a subtle way. The storyline never ventures into the realms of predictability. While reading Wild Houses you know roughly where the story is going, enough for some level of relief, almost cushioning the blow of the oftendiscomforting topics of conversation that Barrett poses. Barrett’s dialogue is so witty and inventive, that the conversational tone induces the addressing of these key themes. Moreover, these topics matter through writing on The Troubles; this accessibility promotes conversation, opposing Ireland’s historic affinity to silence in the face of violence. Wild Houses stand its ground and importance without being priggish and preachy. The moral value of this book is wrapped up in an enthralling and, in places, heartwarming story - it is hard not to appreciate the message.

Overall, Wild Houses considers a range of modern issues while engaging readers in an exceptional story to be immersed into. Whether you are interested in the social politics, the action, or the relatability of the characters emotions.

"Wild Houses is worthy of your time."

By Amanda Chittock

A highly anticipated and fiercely competitive school event returned for the annual instalment of St Peter’s own ‘Booker’ debate. A-Level English Literature students read and analysed a Booker novel and then, united with a teacher, argued their case of, ‘Why does your book deserve to win the Booker prize?’. Excitement and motivation built leading up towards the event as speeches were finalised and rehearsed. Mrs Wong hosted in the library; the room was transported into something resembling a fiction novel with fairy lights, posters and cupcakes. This set the tone for the evening where we heard from the six different pairs about their novels. Exemplified below is a comprehensive review of ‘Playground’ by Richard Powers which featured in this year’s debate.

Is it a dystopian universe or a compelling novel exploring the pressing issues of our generation? Richard Powers’ novel, Playground, is an exceptionally crafted piece of literature that follows the friendships of Todd Keane, Rafi Young, Ina Aroita, and the aquanaut Evelyne Beaulieu. Through discovery and self-exploration, the characters are brought together on the French Polynesian island of Marketa, where 82 islanders face a referendum on sea steading, growth, and development.

"The book is painfully relevant to our generation as core themes of the AI revolution and the diminishing environment provokes an emotive response from readers alike."

However, Powers’ acute awareness of a bleak future contrasts with the omnipotence of the natural world, through depiction of the essence of a haven and a desire to protect it.

A compilation of the book’s ‘best bits’: The immersive realism of the book: when I began Playground, I thought I had been given a dystopian novel, set in a world not far from ours, but one ravaged by climate change and ignorant

technological advancements. But when I finished, I was hit with the sobering fact that everything Powers writes is imminent. Playground is more than a novel: it is an exploration of humanity’s relationship with nature, the forces shaping our future, and the intricate connections between us and our oceans.

A wizard of description, Powers writes with intellect and electrifying beauty on everything: from the brain structure of manta rays and beyond. The writing in these parts is selfconsciously human, and, through Evelyne, our aquanaut, the reader is enlightened about the long-held taboo against this approach and its critical significance. This is a novel that seeks to humble us, it wonders and worries about health, the Earth’s temperature, and rising levels of our seas; about poaching, plastic, and global toxicity.

Poignant themes: Powers does not just present an oceanic love letter; he addresses environmental themes into sharp relief, focusing on the seas— their ecosystems, the looming threat of human colonisation of the undiscovered depths, and our ethical obligations. Through his wonderfully fleshed-out characters, we confront our complicity in environmental degradation and the social costs of unchecked scientific exploration.

What makes Playground truly ‘Booker-worthy’ is Powers’ storytelling genius. I felt as though I was reading folklore, something deep-rooted and innate. He seamlessly weaves science, history, and philosophy into a narrative that is both hauntingly beautiful and intellectually gripping. This book is not just a novel; it is an urgent call to action. Powers’ writing inspires both awe and a renewed sense of responsibility, making Playground a beacon for literature with a purpose.

Heartfelt thanks must go to Mrs Wong and Miss Edgar for creating a fantastic evening. Congratulations to Upper 6th students Tassie H and John M who, with the help of Ms Geraghty, won the debate with a stunningly compelling speech of Percival Everett’s ‘James’.

By Sylvia Sharp

Many describe classical Greek as a dead language, but can a language ever really be ‘dead’, especially if its influences are still so prevalent in the present? To understand properly the evolution of this language throughout time, we need to begin with the Proto IndoEuropean (PIE) language – the reconstructed ancestor of the IndoEuropean languages. PIE is made up of a series of consonants and vowels, with numbers and accents to indicate a specific pronunciation. For example, méh₂tēr is the PIE word for ‘mother’. There are many similarities between classical Greek and PIE, such as the PIE word dhugh₂tḗr, which bears a very similar resemblance to the classical Greek word θυγατηρ (thu-gat-eh-r), and the aforementioned méh₂tēr is similar to the classical Greek word μητηρ (m-eh-t-eh-r). This is due to the fact that Greek is an Indo-European language, of which Proto-Indo European is their reconstructed common ancestor. We can clearly see how this reconstructed language provides a firm foundation for the words that we are able to recognise in classical Greek today, demonstrating how language is a journey that transforms and adapts. Proto-Indo European is thought to have been spoken as a single language around 4500 BCE to 2500 BCE until, through migration and shifts in pronunciation, it gradually adapted into the ancient IndoEuropean languages. For Greek, this became Proto-Hellenic (or, Proto-Greek). It still appears very similar to its Proto-Indo European ancestor, but there were shifts in the way in which it was spoken. Still, there is no recognisable alphabet which we would associate with the Greek language today. The alphabet itself can be traced back to the Phoenician script, which originated in around 11th century BC. There were 22 letters, and we can clearly see the resemblance between these and the modern Greek alphabet.

This is the Phoenician Kaph, which evolved into the Greek Kappa which resembles the modern English alphabet letter 'K'.

These similarities and clear patterns of letter evolution are also very apparent in the modern Greek alphabet letters of 'beta' and 'theta'

The Greek alphabet itself eventually came about and was standardised much later, after an era of Greek language known as ‘Mycenaean Greek’. This version is the most ancient form of Greek language that has been discovered, and was written in a syllabic script known as Linear B. Following this came Ancient Greek, used around 1200-1300 BC. As the standardised Mycenaean language was no longer used, local dialects would have continued, resulting in a varied range of dialects to follow. Ancient Greek was used in Homeric poems, philosophy, drama, and history – and thus the alphabet as we recognise it was adopted in the 8th century BC. Within this period of Greek language, there were many branches which varied from place to place, such as Attic and Ionic, Aeolic, Arcadocypriot, and Doric, many with their own further subdivisions. Hellenistic Greek then evolved from the spread of the Greek army following Alexander the Great in his conquests during 4th century BC. It is also known as ‘Koine Greek’ and is the language of the Christian New Testament, and was used as the liturgical language of services in the Greek Orthodox Church7. Medieval Greek is the stage of Greek language following Hellenistic Greek, and dates to around 1453. During this time, it was influenced by Latin vocabulary and was adopted by the Church as an official instrument of expression. This was the last period before the development of modern Greek as we would recognise it today.

Although the language has evolved distinctively over time, many of the words that we use today still have their roots within the Greek language. For example, take the word ‘democracy’. This comes from the Greek words δημος (d-eh-mos) and κρατος (kra-tos), meaning people (δημος) and power (κρατος).

Another example would be the phrase ‘eureka!’. Most people would recognise this as an exclamation of joy or triumph upon discovering something, famously used by the Greek scholar Archimedes. But the word eureka (ευρεκα) actually means ‘I have found it’ in Greek!

Furthermore, many medical terms are derived from Greek words, such as the word δερμα (derma) meaning skin – which is where we get words like dermatologist and dermatitis from. Also, the word καρδια (kardia) means heart, and so we get words like cardiac from this.

It is clear to see how this ancient language has heavily impacted the way that we speak and think about words today, demonstrating that perhaps this ‘dead’ language is not so completely dead after all.

Eryn Watson

By Maggie Ruan

Warning: the following text contains spoilers for ‘Hamlet’ and mild depictions of violence.

‘To be, or not to be, that is the question’. Arguably everyone, regardless of their interest in literature or theatre, knows of this famous soliloquy in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. This speech paints a picture of a pitiful, depressed, and suicidal protagonist. But is it morally right to feel sorry for Hamlet? It is true that he is in a miserable situation at the beginning of the story, but are his actions justifiable? You might be wondering what on Earth am I talking about. Well, you can either go and read Hamlet right now or watch Kenneth Branagh’s four-hour uncut adaptation. Or you could read the extremely condensed summary of everything you need to know on the next line (or all three, if you are really keen).

Hamlet, the crown prince of Denmark, returns home from university to Elsinore castle to find that his father has passed away (poor Hamlet). Meanwhile, his mother, Queen Gertrude, has remarried Claudius, his uncle (poor, poor Hamlet). As one would expect, everything escalates from here. Hamlet’s dad reappears as a revengeful ghost and reveals that his seemingly innocent death was a scheming murder by poison, and that murderer is no one other than his brother, Hamlet’s uncle who is also the current King of Denmark. Hamlet is urged by the ghost to take revenge and kill his uncle, to which he swiftly agrees, plotting to avoid others detecting his intentions by acting ‘crazy’. Certainly, this situation would cause some inner torment - and that’s putting it lightly. All the same, if ‘Hamlet’ wasn’t a tragic play and if Elsinore wasn’t a fortress of deception, would he be held liable for what he has done? In other words, are severe grief, anger, hatred, and above all a ‘supposed’ insanity defensible reasons for criminality in today’s society, even with a reasonable motive?

The short answer is yes. But as the law is an everchanging field, let’s go back and look at the case with a view of law from Shakespeare’s time (the 16th Century), which means criminal law in Elizabethan England. Many of Shakespeare’s plays demonstrate an accurate understanding of legal

matters and terminology, most significantly in ‘The Merchant of Venice’ and ‘Measure for Measure’ but also in ‘Hamlet’ when our protagonist reflects on life upon seeing rotting skulls in a graveyard:

Why may not that be the skull of a lawyer? Where be his quiddities now, his quillets, his cases, his tenures, and his tricks? Why does he suffer this rude knave, now, to knock him about the sconce with a dirty shovel, and will not tell him of his action of battery? Humph!

(Hamlet, Act V, Scene 1, 99-104)

English Law was at a pivotal point in the 16th century when ancient feudal ways were replaced by a modern system that is still in use today. Insanity was already a well-established defence for criminal acts, dating back to 1324. If the defendant was successful, they would be allowed to go home or stay confined until a royal pardon is granted. Most importantly, after 1542, a clinically insane defendant could not be tried and could walk away for any crime, including high treason. But let’s take this back to the play.

Hamlet has a heated and rather one-sided argument with his mother, Queen Gertrude, in her closet (a private room) and becomes very aggravated, causing Gertrude to cry out for help. Polonius, the King’s counsel, who has been concealed behind a curtain to eavesdrop on their conversation (unbeknownst to Hamlet) cries out for help as well and reveals his hiding place.

Polonius:

[Behind the curtain] What ho! Help, help, help!

Hamlet:

How now, a rat? Dead for a ducat, dead!

[He stabs through the curtain with his rapier.]

Polonius

Oh, I am slain!

Gertrude:

Oh, me, what have thou done?

Hamlet:

Nay, I know not. Is it the king?

(Hamlet, Act 3, Scene 4, 23-27)

One interpretation of this scene could be that Hamlet is out of his mind and genuinely thinks there is a rat behind the curtain, so stabs at it blindly. But if this were the case, Hamlet would have been mad (i.e. out of his mind) to the point that he could not comprehend the fact that rats can’t speak, and by no means cry for help. Seeing Hamlet was extremely invested in his role as acting insane, he may be really starting to lose his mind, therefore leading to the lack of a guilty mind or mens rea during the moment of killing.

Another interpretation would be that Hamlet is very aware that there is in fact a man behind the curtain and assumes that it is King Claudius (because who else would be hiding in his mother’s room apart from his uncle/stepdad?), whom he has been seeking revenge on to kill. Therefore, his questioning of ‘Is it the king?’ could be seen as seeking an affirmation by stabbing Polonius in an attempt to kill Claudius.

To understand how to pull off what Hamlet did (do not try this at home), we can travel a few hundred years after his time, when the idea of ‘yes, I intended to kill a man but not this one!’ was reflected in the 1843 trial of Daniel M’Naghten (pronounced McNaughton), who was a woodturner-turned-assassin that shot the prime minister’s secretary, Edward Drummond because he thought Drummond was prime minister Robert Peel. But M’Naghten was dismissed as not guilty on the grounds of insanity; his paranoid delusions were testified by various doctors and witnesses from his hometown in Glasgow. Even though he was able to tell right from wrong, which was the general test for insanity in the 1300s, the delusions (serious paranoia of himself being spied on by the Tories) led to a loss of moral reasoning and self-control.

If Hamlet was a lawyer and the play was set in the modern world, another precedent that he could use as part of his defence would be the case of R v Burgess (R is short for Regina, the Queen, or the Crown and the Commonwealth).

On 2 June 1988, a bit more than a hundred years after M’Naghten’s time, Barry Burgess, allegedly sleepwalking, attacked a sleeping Miss Katrina Curtis on the head with a bottle, followed by

a videotape recorder. He was in the process of strangling her when he suddenly came to his senses and called for an ambulance (out of interest, Burgess only regained a conscious mind after Miss Curtis said “I love you Bar”). He was also found not guilty under the insanity defence as well as automatism as violence during sleep, an unconscious state, is abnormal and Burgess could have been in a hysterical dissociative state according to neuropsychiatrist Dr Fenwick, a testifying doctor for the defendant. Fast-forward to 2009, campervan ‘dream killer’ Brian Thomas was not guilty of strangling his wife as he had dreamt that she was an intruder because his actions were in line with automatism. But what does all this have to do with Hamlet?

For one, we can link M’Naghten’s paranoid delusions with Hamlet’s state of mind in Gertrude’s closet. Both men had the intent of killing a particular person in mind but ended up mistakenly killing someone else. M’Nagthen shot a secretary instead of the prime minister, and Hamlet stabbed a counsel instead of the king. Meanwhile, it can be argued that Burgess’ sleepwalking and Thomas’ nightmares are comparable to Hamlet as well, with violent actions in a state of automatism as at that moment, none of them thought of what they were doing as legally incorrect, acting on impulse or without conscious decision. So, if they could get away with it, why can’t Hamlet?

The key difference is that the men involved in all of the real cases had doctors testifying for genuine medical insanity, which is not the case for Hamlet. In the beginning of the play, he said that he would put on an ‘antic disposition’, an act to deceive the court and bid himself time in order to remain unsuspected until he kills the king. However indecisive he is in acting on his words, he does not seem regretful of the torment he has caused ever since he put on that act of insanity. It is unusual for the protagonist to be the one doing things that are generally considered ‘wrong’, but the main character does not always have to be the hero of the story. For all he claims the monarchs are ‘damned villains’, Hamlet seems to be becoming more and more alike to everything he stood against, with all the torment he has caused, along with voluntary manslaughter and towards the end, a

first-degree murder (and this is not counting the number of deaths he is indirectly responsible for, which is basically every significant character in the play). Unlike Burgess, he doesn’t have a moment where he comes to his senses until in his last moments after he has gotten his revenge which is a tad bit late. But then again, it wouldn’t be a tragic play if the ending was any different.

Nevertheless, a play is merely a story waiting to be acted out and each actor may portray Hamlet very differently based on their interpretations. One actor could make him sound regretful of his actions, with a display of fear and guilt as he examines Polonius’ dead body. Conversely, another could portray him as scheming, with an eager glint in his eyes that fades away into disappointment when he realises it is not Claudius he killed. However, based solely on the evidence from the play itself, it is much more likely for Hamlet to be found guilty of his actions if he existed in today’s society, based on the lack of medical testimonies of his mental condition and the ‘method’ in his ‘madness’, which wouldn’t really help his case (not to mention he would probably drive the judge mad in a trial by being impertinent). He must either be entirely insane, not insane but a menace or constantly hovering between the borders of the first two. The latter is a more popular opinion, but it is unlikely to be an acceptable defence in court.

Overall, Hamlet’s just verdict is a relative concept depending on the actor and the audience. Literature is much more open to interpretation than real life; words on pages do not face the same consequences as human beings- fictional characters don’t often just punishment in accordance to the crime unless they are the villain. Unlike literature, which is kept eternal in books, the law changes constantly to adapt for different values in different times. Hamlet is only one example of how ambiguity and empathy affect morality, elements that may be needed in the law at times but avoided in others.

Literature trains people in the reflection, consciousness, choice and responsibility that make up the ability to engage in moral decision making. It does so by presenting artificial but concrete universes in which premises may be worked out in conditions conducive to empathy but ambiguous enough to allow for the formation of moral judgement.

Lawyers should look to literature as a rich source of certain forms of knowledge that the law is either missing entirely or could use a whole lot more of...

Jane B Baron, Professor of Law and literary theorist in her ‘Law, Literature and the Problem of Interdisciplinarity’.

Two years ago, in the winter of 2022, my family took a trip to the M+ art gallery in Hong Kong. As we walked up the gallery stairs and entered the main exhibition hall, I turned the corner and was surrounded by a flurry of mirrors, dots, nets, and sculptures. This is how I got to see the work of Yayoi Kusama in person, and gain a greater appreciation of it.

That year was a new beginning for me, I had just started seeing a psychologist, I was considered fragile, delicate, and sensitive. I was regaining my identity, after being lost in my struggles for so long.

I found I was able to relate to Kusama, when I walked into that gallery, I thought she was just another famous Japanese person that my mother wanted to go see, to instil a greater sense of pride about my heritage. Yet, as I read every note on the gallery walls, I realised that Kusama was more than this. She was someone open about her mental health in a country where it is considered a personal weakness, ¼ people aged 18-22 have contemplated suicide, over 70% of those individuals have never received help about it.

Kusama was born on March 22, 1929 in Nagano, Japan to a wealthy middle-class family. Growing up, she suffered physical and mental abuse from her mother. In fact, Kusama suffered many traumatic experiences related to her family life, such as being forced to spy on her father by her mother, the consequence of which was the younger Kusama to witness her father’s affairs. A mental scar that left her with a phobia of sex.

Kusama has always been open about the hallucinations, anxiety and depression she experiences. She has talked about when her vision has been clouded by polka dots as a child. In fact, since 1977 Kusama has voluntarily lived in a psychiatric hospital in Tokyo where she commutes to and from her studio nearby to work everyday.

If you recognise Kusama’s work, you likely know that the polka dot is not an unfamiliar concept. In fact the polka dot and Kusama have become almost

synonymous with one another. Whether it be during a trip to the Tate Modern, or the collaboration with Louis Vuitton, both the work and Kusama herself are depicted with an army of endless dots.

Dots have been a symbol which she has worked with for her whole life. One of her earliest known works; this drawing made by Kusama in 1939, aged 10. A woman, Kusama’s mother, wears a kimono and her face is covered by polka dots.

The dots link to the idea of infinity. She aims to represent the infinite, everything yet nothing all at once, as it allows her to self obliterate into the work. It is a physical manifestation of her working through her trauma and a form of self-medication.

The installation is roughly 25 square metres. It’s a mirrored room where the floor is covered completely by phallic, stuffed, soft sculptures which are covered in red polka dots.

As you enter, the door closes behind you, leaving you in a completely mirrored space. The mirrors immerse and envelop the viewer. It draws you into an endless plane of multiplicity, as the sculptures that cover the floor continue to stretch out and create a plain, or field (hence the name) which countless versions of you roam, reflected in the mirrors and assimilated into the work.

‘Phalli’s Field’ first appeared in her 1965 exhibition ‘Floor Show’ at the Castellane Gallery, New York. This was the first of Kusama’s works incorporating mirrors, beginning a series which Kusama continues to this day. She has likened herself to Alice, from the tale Alice in Wonderland, going through the glass and entering a whole other world.

The phalluses were likely the first thing you noticed when you see the piece, it feels obscene and discomforting; especially with the bright, cool toned light illuminating from the ceiling, creating an almost clinical feeling in the room.

The bright red spots which cover Kusama’s phalluses contrast the white fabric and overhead

lighting in the room. This creates a conflicting experience as your eye is drawn to them yet simultaneously, the sheer volume of and varying sizes on each protrusion create a sense of movement and disorient you.

The soft sculptures were in part Kusama’s attempt to confront her phobia of sex from witnessing her father’s affairs in childhood. They became part of her major works in 1961, when she began her Accumulation series. She used the skills she learnt from sewing parachutes in WW2 to hand sew each soft sculpture, which was then used to cover everyday objects. Yet these lacked her iconic polka dots in ‘Phalli’s Field’.

Kusama desacralizes the male genitalia with her accumulations, applying a humorous and obscene take on the revered male form. Artists within the Western tradition, considered the male body to be the peak of perfection and human virtue whilst creating their idealised image of women often through a voyeuristic lens, where women’s bodies are both objects of desire yet must remain chaste. Thus, the phalluses can be seen as a form of commentary of the sexualisation of women within society. The portrayal of women has often depicted them as the softer, weaker sex. Their figure is emphasised by delicate curves, akin to the curved shapes of the soft sculptures.

Kusama was also an innovator, inspiring many of her male contemporaries such as Andy Warhol, yet never fully receiving credit for it. In 1963, Kusama presented her piece ‘Aggregation: One Thousand Boats Show’ in the Gertrude Stein Gallery. A 10-metre boat, covered in her phalluses occupied a room where the walls had 999 photos of the boat on the wall. Warhol complimented the work, especially the wallpaper used, and in 1966, he unveiled his ‘Cow’ wallpaper. In many ways, by trivialising the male form, she is also commenting on the male domination of the art world – something she experienced firsthand.

When describing herself, Kusama has used the phrase “obsessional artist” Like most of her works, the specific symbol used here becomes another obsession of Kusama, and it continues to be used throughout her work, often being taken to the extreme.

Personally, they remind me of sea anemones or villi, the lining within your intestines. They look

as though they should be moving, wriggling with life all individually. I think this is amplified by the curving shapes and direction of each protrusion that seem to reach outward towards you.

In recent years, following her propulsion to stardom, Kusama’s Infinity Mirror rooms have continued to evolve. They are now one of her most popular works, drawing lines of people to queue for the opportunity to enter for sometimes less than a minute. They continue to be an immersive experience as she plays with light and dark. The dots which are so indicative of her art have now expanded into a universe, resembling shimmering stars in the cosmos.

Her work’s explosion into infinity, whether it be through painted polka dots, phallic protrusions or twinkling lights, allows Kusama to remove herself, into the work, and invites the viewer to do so too.

Kusama has said “My art originates from hallucinations only I can see. I translate the hallucinations and obsessional images that plague me into sculptures and paintings”

During struggles with my own mental health, feelings of isolation and loneliness have been overwhelming. Yet for me, the thing which has brought me strength was knowing I wasn’t alone in what I was facing.

Negative stereotypes about mental health plague our society today. Many people fear those they perceive as different and cast judgement upon them. This prevents people from speaking out about their experiences and closes important discussions. The way Yayoi Kusama communicates using one of the most powerful languages, art, to connect with others, to turn the experiences which have been so negative or frightening to her into something vibrant, so they can see the world as she does, is something I find beautiful.

To finish off, I wanted to leave you with a quote Kusama said: “Accumulation is how the stars and Earth don’t exist alone”, just like Kusama’s accumulations or dots, we are united and present all together, another dot in the ever-expanding universe.

By Katie Butler

How long have you been teaching at STP?

This is my 5th year in St Peter’s and my 4th year as the Head of the English department. This is my 15th year of teaching all together

What is the main difference between when you were taught at school and how you teach here at STP?

When I was a student, there wasn’t such an incredible range of subjects on offer as you have at STP. You only had the opportunity to learn one Language, and that just depended on which form group you were in. I had some wonderful teachers and much of what they brought to lessons has stayed with me. We didn’t have as many big community events like Commemoration or House Singing- and certainly no regular visits to anywhere as impressive as The Minster.

What is your favourite time of the school year?

The Christmas term is probably the busiest and most intense but it’s a lot of fun. Certainly, in the first couple of weeks, everyone is quite nervously excited for the start of the new term. By week three, when you know all your classes, you’re just very excited to see how they can develop and how they will enjoy lessons together.

There is also that huge change of season. It’s always still so hot when you return in September, then just before Christmas, it becomes cold and dark and it feels like a completely different world outside.

Although it’s a long and busy term, I really enjoy things like House Singing and getting to know classes. And I really love the build-up to Christmas!

What has been a challenging time you’ve experienced at STP?

I think probably for me, it was during the times of COVID lockdown. I started teaching in St Peter’s in September 2020, so my first few weeks were strange.

We were teaching in ‘bubbles’, everyone was wearing masks, and I taught in different parts of the school. Quite a lot of my English lessons took place in the Science department, Pascal and Geography. I got to see different parts of school that I wouldn’t necessarily have seen otherwise, so it was actually a nice way to get a sense of the whole school and getting to meet different colleagues. This was a nice way to get introduced to the school. However, what was most challenging, even more than teaching in bubbles, was when we turned online. It lasted about 3 or 4 months, and it was hard to not have the human connection and build in-person relationships. I think that was a really challenging time for everyone.

Despite all this, the school was really good at keeping in touch with people as much as possible. We had online photo challenges for the pupils to take photos of their pets reading, staff yoga over ‘zoom’ and recorded assemblies,

I think that’s such an interesting question because teaching is quite different now from 15 years ago when I started. Technology has certainly changed in the past 15 years from not many people having devices to us now relying on them. So, when St Peter’s pupils have access to more technology it will be interesting. But, overall, I think that the fundamental things won’t change. The kind of pastoral care that we offer will still be excellent, and the lessons that we teach will still be excellent and really wide ranging.

By Róísín Gleeson

In total, there are 24 time zones around the globe, 11 in the continent of Asia alone – and, theoretically, these sections of the earth are the only things that make time travel possible. It’s surprisingly simple: catch a flight west over the Atlantic Ocean, and you’ll find yourself several hours behind those back at home. However, this viable impossibility doesn’t come without its side effects. Adjusting to a new time zone can be difficult as in the end you’ll often spend much more time recovering than the time you saved. So, how can this be resolved? How do you recover from jet lag?

Many will suffer from a change in time zones when going on holiday to a sunny, tropical destination, which is evidently different to what we’re acclimated to in the UK; nonetheless, weather itself is the perfect solution to jet lag. Enjoy as much sunshine as possible, allowing your brain to adjust to the new time frame. In addition, even simple things like sticking to your usual nightly routine and setting an alarm in the morning to avoid oversleeping can make all the difference.

So, there may be a way to reduce their effects, but do you know why, or how time zones came to be? Time zones have always existed, long before even humans roamed the earth, but in 1878, Sir Sanford Fleming first put forward the idea of dividing the world into 24 separate regions – each one 15 degrees of longitude apart. This was, and still is necessary, because the earth rotates about 15 degrees each hour, meaning the time zones can be in line with the earth’s orbit. However, it took a few years for Fleming’s proposal to he accepted. It was not until 1884 that Greenwich, England was finally appointed as the ‘prime meridian’, meaning all other time zones would be centred around this location. This is where the terms, ‘GMT+0,’ ‘GMT+1,’ and more come from, which you likely have seen before.

Still, it must be noted that when we think of time, we tend not to think of present time, such as the time zones, but of legendary stories of the past, like heroes in Ancient Rome or medieval kings and queens whose legacies still live on but fade more and more as time passes. Their very actions are defined by a date and little more. But when we think of time in greater detail, these dates become less significant, in the same way that time zones do; just like the time zone system could have been created differently, so could the measurement of years. Perhaps if everything was decided a year later, we would be in 2026 now, not 2025 – and yet nothing else would change, exactly alike to how if Sir Fleming’s idea was in any way different, the world would still be the same as it is. In simpler terms, the earth is the same whether or not we recognise time zones, or even time at all.

Yet what bewilders many is that the creation of these time zones is a phenomenon arranged solely by people, much like the names assigned to colours or even the laws of a country, which may make you wonder: how is time itself separated from this? Is it completely out of our control? Or is the concept of time – all that we can see, sense and understand of it – orchestrated by humans?

As time passes, our knowledge evolves. As time moves on, so do our theories. Our knowledge of the universe is constantly changing. Our knowledge is impermanent.

If I asked you to think of an idea that changed our understanding of the universe what would you think of? The Big Bang, The Theory of Relativity, Cosmic Inflation, or the Four-Dimensional SpaceTime Theory might spring to mind. But what if I told you that none of these theories could’ve ever come to light if it weren’t for one fundamental idea: The Heliocentric Theorem.

To put it simply, The Heliocentric Theorem (also referred to as the Copernican system, titled after its founder, Nicolaus Copernicus) is the idea that everything in our solar system orbits the sun. But to you, that might not seem like a massive revelation; it’s likely something you learnt around the same time you were learning 1+1=2, a cow goes ‘moo,’ or that when you throw a ball up in the air, it will fall back down. So, why is it such an important system? It all dates to long before our time, with the creator of the geocentric model being born in 400BC.

“To know that we know what we know, and to know that we do not know what we do not know, that is true knowledge. In the midst of it all dwells the Sun.” - Nicolaus Copernicus.

Eudoxus, a Greek mathematician, created the original geocentrism model. It was the idea that everything in the solar system orbited the earth, including the sun, the stars, and the planets - which we weren’t quite fully aware of at the time. Accordingly, many famous philosophers or astronomers including Plato, Aristotle and Ptolemy stood up for the theory; to people of their time, it made perfect sense. Geocentrism was believed for many centuries (specifically, from the 8th to 13th), and the powers, at the time, had geocentrism as one of their firm beliefs.

Interestingly, even though geocentrism was pushed to be the main centric belief, the heliocentric system was not completely unheard of. A Greek scholar named Aristarchus of Samos had proposed the idea of the heliocentric system, circa 310-230 BC. We don’t hear about this in many recordings, as the idea was viewed upon in a negative light.

So how did we arrive at the idea of the heliocentric theory?

Nicolaus Copernicus was the first scientist to fully tackle the idea. Copernicus read the works of other astronomers and had made his observations. Intriguingly, he discovered that geocentrism could not explain the movements of the planets, and that the heliocentric system was the only clear way to explain this. And so, Copernicus put his beliefs down on paper, in his first book De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (‘On the movements of the heavenly spheres’) in 1543.

Unsurprisingly, this was much to the dislike of the people around him for many reasons. Supposedly, his calculations and predictions were incorrect, they had stated that the orbits of the planets were circular, rather than elliptical as we understand today. Additionally, people were very close-minded; the idea that something that society had relied on for millenniums could be false was simply unacceptable.

If society would not listen to Copernicus, another scientist would have to pave the way.

Galileo Galilei was the next to follow up in the heliocentric theorem.

Whilst attending the university of Padua, Galileo had been researching the works of Nicolaus Copernicus. Whilst at work he had come across the copernican system and was absolutely fascinated. The system made complete sense to him, so with this new profound inspiration, Galileo went to a local shop and purchased a spy glass in order to formulate his own telescope. Galileo was determined to prove the Copernican system, so he gathered proof and information about the phases of Venus and Jupiter’s moons to dispute any uncertainty about the theorem. Galileo’s findings displayed that our solar system simply couldn’t be geocentric because Jupiter’s moons orbited something other than the Earth, but also that smaller objects orbited bigger objects - this would bring in the question of how gravity works. He then published his findings, although

upon prosecution by the Catholic Church, Galileo was sentenced to house arrest till the end of his career, because his discoveries disagreed with that of the church, who held geocentrism as a steady belief - bringing Galileo’s career to an end.

And so, after yet another fail in terms of globalising the heliocentric system, another scientist would brave the challenge and bring the world to light: none other than Johannes Kepler.

At the time, Kepler too was studying planetary movements. Kepler published his three laws of planetary moments between 1609 - 1619. Keplers main goal was to bring elliptical orbits of planets into the picture. He began to prove the heliocentric model by looking at the distance between mass and the sun; Kepler observed that the further Mars was away from the sun, the faster it moves. So, not only did this prove elliptical orbits, but it proved that the planets cannot orbit the earth, but instead, the sun.

Kepler’s findings completely disproved the geocentric theory, and for once, the heliocentric theory became the main centric belief in our solar system.

All thanks to three great astronomers, we now have such a broad understanding of our solar system. Without the understanding of the centric systems, we would not be able to progress any further in therms of cosmology, astronomy and astrophysics.

How long have you been teaching at STP? I have been a teacher since 1978 and started teaching at STP in 1982. That comes to a total of 43 years.

What is the main difference between when you were taught at school and how you teach here at STP?

The biggest change is when we went fully mixed in 1987. We’d already had sixth form girls but we only took in girls completely 38 years ago. And without a doubt, it’s the best change in the school’s time. Music, especially choir changed overnight following the addition of girls to St Peter’s. Allowing us to really start to push the music forward. As well as this, the girls sport has gone from being something small to now having girls that girls’ sports has increased to have the same level as national finalists. I would say that the way as the boys, has been huge. Girls’ hockeythey’ve been in national finals, girls’ netball, they’ve been national finals, girls’ tennis - they’ve been national finals, alongside very successful female rowers, some even having experience in Commonwealth games and so on.

What is your favourite time of the school year?

This is a really difficult question! I love the build up to Christmas, with the proper carol service, as we’re back to nine lessons and carols. It’s super - finishing the Christmas term with house dinners and in the Minster is a very special way to end a term. As well as this, I also think the end of the summer term is great. Especially for the Upper Sixth Cricket, with the final cricket match and also with the rowing at Henley. It’s a very special time of year. Commemoration, on the last day of school, which used to be separated into two different days but now combined on one day now and the proper end of term ball for the Upper Sixth, it’s huge. That’s a really big thing. We didn’t used to have this ball, in fact a female member of staff called Gene Wagstaff started it back in the 1980s.

The Easter term for me is always the more difficult term, because there’s not really that much to look forward to for at least two year groups - the Fifth Form and the Upper Sixth. It’s just more work, more work, more work. The pressure academically can be horrid, even worse than the summer term with the exams actually. But from the rugby point of view, specifically, the Rosslyn Park Sevens always provide something huge for those year groups, especially now that the Third Form are involved as well as the other juniors and Sixth Form. And you meet a lot of people through that.

But throughout all of this, you’ve got music that is consistent throughout the year. You get a lot of music in the first term, which is great to watch. In the second term, you’ve normally got the Whole Foundation Concert. And then the third term, you’ve always got the cabaret to look forward to. Proving the balance of the extracurricular with academics is really important.

What has been a challenging time you’ve experienced at STP?

For me, it was the early doors, in the 1980s. That was when I had to get used to having a level of responsibility and taking over a dayhouse when I was 26/27. Alongside this, when the school went mixed, there was quite a lot of resistance to that. I come from a mixed school and a mixed college at university, so it was entirely normal for me. In fact, I found being at an all boys school with girls difficult. So the challenge then, was making sure that the girls were able to get a fair crack of the web, whilst the boys wouldn’t have felt disadvantaged. There was quite a lot of resistance, some Old Peterites were very resistant to that move, and were determined that the mix would cause our sport to change, it fortunately hadn’t. We worked very, very hard to make sure that worked.

school, we have moved on from essentially just a reversion of ‘chalk and talk’. I think we have to bring the testing in line with modern society.

How do you imagine STP in 10 years’ time?

I see St. Peter’s being in a very, very strong position in 10 years’ time because of the foundations that it has now.

As we are able to embrace the changes that we’re making, and with our girls properly embedded as part of the school, making us a truly mixed school - and not girls in an all boys school. And better sports facilities and drama and performing arts developments, we will be at that very, very strong position.

I very much hope that the Pastoral side, with a Sixth Form centre planned to be built, will enable the Sixth Form to have more of an influence on the junior pupils, in a mentoring role. Where they are able to get more responsibilities to be part of the mentoring side of the school, so that the pastoral side is an integrated whole school thing in 10 years’ time. With these plans in place, I think that our school will certainly go in that positive direction. With a more restorative approach, where you’re able to challenge very early the sort of behaviour that goes on in the middle school, which is often simply born of embarrassment or not really knowing how to behave, we can challenge it, without it becoming hugely disciplinary. We’re not necessarily punishing the action, but the attitude that says, ’I won’t change.’. And we all need to change.

This will make a big difference as we allow the sixth form to have more influence, especially on the eleven year olds when they come in J4, allowing the whole school is able to come together.

For example, part of the time when I was in the Manor, was the sixth form becoming mentoring roles, which many of them embraced. And by the last few years, they were very used to the sixth form being the ones who looked after the junior pupils. They were the ones that the junior pupils would go to first. If there was a problem, they’d tell them. And then the staff could get the filter of that information. Enhancing the role of the sixth form within the pastoral system and being part of the process is something that I would hope is in place in 10 years’ time.

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, the clock started ticking. Every passing hour added urgency to the global effort to develop a vaccine. What normally takes years in vaccine development was compressed into mere months. But while the speed of development was unprecedented, the passage of time revealed the complexities and challenges that came with such a monumental task. In this article, I will discuss the changes in the Covid vaccine developing process which lead to the invention of a safe vaccine in a short period of time.

Before starting, let me introduce the normal process that normal vaccines need to go through before being published and manufactured. Firstly, preclinical research has to be conducted, which means researchers have learned about the targeted pathogen. Then, design and develop the vaccine by using inactivated virus, live-attenuated virus, protein subunits, or viral vectors to stimulate an immune response which makes sure the vaccine is effective. After that, there are animal trials and clinical trials. Finally, data collected from the trials can be sent to agencies, for example WHO, to get the final approval for the post-marketing

license so vaccines can be published and manufactured. The whole process would usually take around 4 to 10 years.

However, the development of the Covid vaccine is different. The process got modified due to urgency.

First, the preclinical process was replaced by prior research, which means scientists used knowledge of previous studies on coronavirus (e.g. SARS and MERS) to inform the Covid vaccine. Despite this leading to a broader collection of knowledge, the messenger RNA (mRNA) technology and information on the structure, vaccine platform and response of the immune system to

the previous variants of Coronavirus helped speed up the process. Add on to that the genetic sequence of the SARSCoV-2 virus, which causes COVID-19, was quickly made available in early January 2020, allowing scientists to begin developing the vaccine almost immediately.

In the vaccine designing stage, new technologies, like mRNA vaccines (e.g., Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna), were utilised, which significantly sped up the process. Instead of using live or inactivated virus, these vaccines use mRNA to instruct cells to produce a piece

of the spike protein from the SARSCoV-2 virus which triggers the immune system. This technology had been in development for years and allowed scientists to design a vaccine once the virus’s genetic sequence was known.

Clinical trials are the starting point for global collaboration. Instead of separating animals, individuals and group trails, they were done simultaneously, allowing for rapid data collection. One of the difficulties that researchers usually face is the lack of volunteers. However, for the Covid vaccine, there was an unprecedented global willingness to volunteer for vaccine trials, accelerating recruitment

and increasing the speed of data collection. Additionally, the step of getting approval from global agencies was replaced by rolling reviews of the trial data as it was collected, rather than waiting for the trials to finish before reviewing all the data. This allowed for quicker decisions on whether to approve the vaccine for emergency use.

In terms of manufacturing process, due to the urgent need, manufacturers started producing large quantities

of COVID-19 vaccines even before full approval. Governments provided substantial funding to set up manufacturing facilities at risk. In some cases, multiple companies built and scaled production simultaneously for different versions of the vaccine (e.g., Pfizer and Moderna). This also means that the post-manufacturing license is rousted. This accelerated distribution helped ensure vaccines were available following approval.

The rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines was nothing short of groundbreaking. Thanks to innovations like mRNA technology, global collaboration, and years of prior

research, we were able to respond to the pandemic at a speed no one thought possible. While it was a huge challenge, the vaccines have proven to be both safe and effective, giving hope to millions around the world. It is important to recognise and thank the researchers, scientists, and healthcare workers who worked tirelessly to make this happen. Their dedication, hard work, and collaboration are what made this achievement possible.

Edith Ko

By Serene Kong

Scattered across the world, religions have varying priorities and values, and therefore have varying beliefs on whether a practice is ethical as well as its treatment options and reasons as to why a practice should be done. Traditional practices of abortion, homotransplantation, allotransplantation, surrogate motherhood and euthanasia are common practices that are known to raise ethical concerns. For example, for euthanasia, many hold strong ethical debates which have been referenced as ‘playing the Nazi card’ or ‘playing God’. Clinical genetic trials, having an ethically debatable situation, like euthanasia, can be seen in the same way, as researchers are making a physical difference towards someone’s body, which could ultimately result in life or death, depending on how selectively advantageous the genetic variation has been.

But first, why do scientists edit genes? The common goal for gene editing is to challenge the human gene’s limit and try to use gene editing to prevent generations from diseases that cannot be cured, such as HIV or to contrast a gene mutation, by purposefully altering an individual’s gene to achieve the ‘ideal’ genome. These trials are often done to achieve a better lifestyle. Often performed by HICs with

advancing technology, these trials are presented with more of a debate whether they are ethically correct or not. To determine whether a decision is ethically right or wrong, to what extent does it depend on the socio-cultural context such as education, demographic and values? As there are over 2500 cultures and subcultures on Earth, this leads to various priorities and values that some cultures may value more than others. How can genetic ethical trials be managed globally if so many cultures co-exist together, which may have contrasting beliefs? Ethical debates on such trials have been conducted on the general public by an experiment conducted by Riggan, Sharp and Allyse from the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. This involves recruiting members of the public and surveying them to see how they engaged with scenarios on possible applications of gene editing in humans. In total, they surveyed 50 people. A variety of results were received.

Firstly, many participants ‘expressed a strong support’ for applications of gene editing, especially for disease prevention such as for cystic fibrosis, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis. As they expressed that if they knew about their genetic and possible heritable condition, they would want their

future generations’ DNA altered to avoid this heritable condition, as it is beneficial to the individual and their future generations - the first of the four medical ethical pillars. Second, some participants believed it depended on the individuals’ want for gene altering, as it is up to the individual’s autonomy - the second of the four medical ethical pillars. As it is still a very new medical technique in trial, its ethicality should depend on the patient’s request and belief for and in the gene therapy. On the contrary, many participants objected to the idea of gene editing. They believe that this technique could lead to misuse and that ‘vulnerable patients could be exploited’, to avoid maleficence towards the individuals and their future generations - the third of the four medical ethical pillars, nonmaleficence. This includes concerns that parents may exploit this technology to physically choose desired characteristics for their children, which may be physically damaging to the children and future generation’s physical health but may also create dangerously increasing limits to what human bodies are capable of. Therefore, many participants believe that the consequences are impossible to predict, due to the recentness of this discovered technology. It is difficult to predict whether these developing technologies will bring the medical field to a new level or begin a genetic crisis that is unforeseeable.

The exploitation of gene technology is presented with a case of China’ gene edited twin sister embryos, Lulu and Nana. Taking place in China, on November 2018, scientist He Jiankui had modified two babies’ DNA to be immune to HIV, despite one of the parents being a carrier. Using a very modern gene editing technology, CRISPR-Cas9, officially published in 2002, He deleted a region of a receptor on the surface of white blood cells known as CCR5, thus making it more difficult for HIV to infect its target, white blood cells, preventing the transmission of HIV from the father’s sperm to the embryo cells. This process has been deemed ethically wrong and irresponsible as gene editing has posed serious risks towards the babies and their experimental monkey zygotes, violating the medical ethical standards in China. He and his team’s actions have been considered extremely unethical. Not only due to the lack of communication about the presence of these genetic trials between him

and the government/other experts but also the undiscussed effects that could have influenced future generations after the genetically varied individual. Some argue that this has not only violated the autonomy of the embryos and monkey zygotes but may have posed a detrimental threat to this generation and their future generations, breaching the beneficence and non-maleficence medical ethical pillars. This is because the long term effects are not certain and would not be until the twins have lived their life as well as their future generations. Should the uncertainty of these trials affect their progression? In fact, without these trials, we would never have had the confirmation that CRISPR-Cas9 technology is able to complete the once known as impossible. This trial has also been argued to have saved the lives of many generations as HIV remains to be uncured. To what extent is this confirmation worth more than the twin embryo’s possible life threats?

Another genetic clinical trial, claimed to be another case of gene editing technology exploitation is based in Seattle, conducted by Elizabeth Parrish, the CEO of BioViva. Parrish and her team are working to develop treatments to delay ageing in humans. Revealed in April of 2016, it was announced that Parrish had even put herself to undergo this treatment. The treatment had lengthened 9% of her white blood cells, which is claimed to be equivalent to reversing the biological age of her immune cells by 20 years. This was done in September 2015 when Parrish flew to Colombia to receive two experimental gene therapies. One was a myostatin inhibitor, a drug that is being tested as a treatment for muscle loss and the other being a telomerase gene therapy, the main drug that BioViva claims has reversed her cells’ biological age. This is done by lengthening the telomere parts of her genetic material. Telomeres are found at the ends of these chromosomes and its function is to protect the important genetic material from damage that can lead to diseasecausing malfunction or cell death. Telomeres also allow the cell and its DNA to divide, but as cells divide, a portion of the telomeres is lost until, after a ‘finite number of divisions’, the cell dies, a process that contributes to the human ageing process, in which Parrish’s trials have claimed to slow down this process. However,

this treatment is deemed highly controversial. BioViva had not done any necessary pre-clinical work to progress to human studies, as well as this, the US Food and Drug Administration did not authorise Parrish’s experiment, hence her trip to an unnamed clinic in Colombia. Many experts have urged caution over Parrish’s impatient approach to unearthing treatments. Despite these warnings, Parrish and her team have announced that they will continue to explore the effects of the gene therapy in other cells in her body, and to assess the effect of the muscle-loss treatment. Meanwhile, they are looking to test the treatments in more people as well as to find a country with less stringent medical ethical requirements than the US.

Both cases of He’s gene edited twin embryos and Parrish’s age delaying processes have been deemed successful and achieved both scientist’s aim, which ultimately have caused a beneficial outcome. But why are they receiving backlash and ethical arguments despite their success on doing the once known as impossible?

However, backlash is not the only response with all genetic clinical trials.

A recent hearing restoration has been able to allow an almost two year old girl, Sandy Opal, in the UK, who was born deaf, to be able to say certain basic words and hear sounds as whispers only having started treatment after her first birthday. Her inherited deafness is due to the Otof gene mutation, causing hearing impairment to that individual, as the hair cells on the cochlea, although functioning, cannot send signals to the nerve. Sandy is a part of the ‘Chord trial’ which recruits patients with similar conditions from the UK, Spain and the US. This trial replaces the faulty DNA which is causing her type of inherited deafness. The gene therapy is conducted by introducing a modified and harmless virus to deliver a working copy of the Otof gene into these mutated cells, allowing the damaged hair cells to be repaired by the gene therapy. In this trial, the first three deaf children including Opal received a low dose of gene therapy in one ear only. After, a different set of three children will get a high dose on one side of their ear. Following this, if the result is shown to be safe, more children will receive a

dosage in both ears at the same time as therapy. In total, recruiting 18 children to this trial. This trial is deemed very successful for Sandy. For comparison, Sandy had the therapy introduced into her right ear and a cochlear implant put into her left. In only just a few weeks later, she could already hear loud sounds in her right ear. And after only six months, her doctors at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge had confirmed that her right ear had almost normal hearing for soft sounds.

However, this therapy needs to be introduced early on to those young children with hearing loss conditions, as a young person’s brain starts to reduce its plasticity after the age of about three or so. At early detection, this therapy can quickly help individuals with this condition as early as possible. Unfortunately, this condition is often hard to detect at such young ages and only can be when a delay in speech develops at around the age of two to three, therefore making the time for detection short. However, Sandy’s evidence of close to hearing restoration presents this therapy as a possible and hopeful cure for this condition. Since then, more children have started receiving the Otof gene mutation therapy at the same hospital and there have been positive results.

The success of this trial has caused beneficence towards the young children, as they regain hearing and are able to continue their life with normal bodily functions, positively affecting their physical and mental health. However, some may argue that the non-maleficence ethical pillar is at risk, as during the trial, especially due to the young age range this trial is targeted towards, the long term effects are not known, an important argument within the He’s twin embryos and Parrish’s age delaying trial, arguing against if these trials are ethically right, with the young children’s autonomy unknown. As well as this, all trials were tested on humans, with the hearing restoration trial on young children, some would argue that the young children are in fact more vulnerable to unknown drugs and pain, in comparison to adults in Parrish’s trial as well as the embryos in He’s trial. Why was the response to the succeeded hearing restoration trial much more positive and mild in comparison to the other two trials, which also succeeded;

and could be argued as more scientifically innovative and fascinating. In conclusion, these scientific breakthroughs have continued to challenge the ethical standards of genetic trials to an incredibly large extent; posing unanswered questions such as for example with He’s trial, would genetic trials have been ethically accepted if a larger team or a governmental team had done this trial instead, like the hearing restoration trial? How many different expert’s voices and opinions for a genetic clinical trial to go through as ethical? With the scientific and social complexities of a trial to be conducted, many experts are involved to ensure minimal complications and exploitation. But even with a sufficiently professional team, is gene altering and therapy determined ethically right or wrong until the consequences have been analysed, despite needing that confirmation before the trial is officially conducted? Is there a possibility that the hearing restoration trial was only deemed ethically good after the positive results have been announced publicly? And even following these consequences have been announced, should these consequences of gene therapy be taken as a priority over the risks, especially as some trials involve very young children and vulnerable patients?

With gene editing at the forefront of scientific evolution, researched and conducted by the top, developing countries. To what extent can gene editing be deemed ethically correct if the result is wanted but not necessary for survival? In some cases, to save the lives of innocent future generations?

How long have you been teaching at STP?

Since September, I used to teach at The Mount, I taught there for 17 years.

What is the main difference between when you were taught at school and how you teach here at STP?

I went to school in Edinburgh, so the school system and the exams are completely different. In Scotland you can’t give up Maths or English after the equivalent of GCSE, you have to do them in Year 12 too! Having said that - Maths is Maths, so the content is fairly similar everywhere. However, as the years have passed, some topics which used to be done at A-Level have now appeared in the GCSE syllabus and some which didn’t appear until university have appeared at A-Level!

What is your favourite time of the school year?

Good question... my favourite term is probably the summer term when all the exams happen. It’s when everybody’s effort comes together and students get a chance to show off what they have learned- so I quite like that. It’s obviously a stressful time for students but when the sun is out everything just feels better! Previously, I used to write the school’s timetable too, so it was a very busy one- it is a nice challenge though.

What has been a challenging time you’ve experienced at

The biggest challenge from me this year has been not knowing stuff. Because I was at my previous school for so long, I knew everything that happened, I knew everybody because it’s a much smaller school, so I knew how everything worked and when everything happened. Whereas here, I still walk around and see loads of staff and students that I don’t know and there are processes don’t know or events which I haven’t seen yet. So, this has been the biggest challenge. Going from the person who people came to ask, to the person who has to go and ask has been a big change.

The planned change to the two-school model sounds interesting. I am looking forward to seeing how that might work and how I can help make that work as smoothly as possible from my area of the school.

The primary/secondary school model is all I am familiar with- hopefully that will make the transition smooth.

I am looking forward to the move to being a one-on-one device school, so every student has a device. This is a model I have seen and worked in before and was one which I liked. I am looking forward to that transition.

By Amelia Harrison

The role of women in society has often been shaped by a complex and largely turbulent history, influenced by a mix of cultural, economic and political influences aiming to suppress the lives of women around them. From prehistoric societies to modern day narratives, the rocky journey of women regaining their rightful place in society has been one of resilience and resistance. Over thousands of years, women have actively fought to create a space for themselves in a society that has disregarded and deliberately suppressed their contributions. But how have these deep-rooted social constructs come into existence, and why have they been so difficult to dismantle?

To understand how these constructs emerged, we must look back to prehistoric civilisations and understand the position that women held in society. The study of prehistoric women is of particular interest to feminist thinkers today as they seek to challenge androcentric assumptions brought about by conventional archelogy and projected modern stereotypes. Advanced research into these societies has concluded that there was no clear gender divide or sexual division regarding labour. Researchers such as Sarah Lacy and Cara Ocobock have highlighted the particular role of oestrogen in the survival of prehistoric women. Oestrogen massively helps to develop type 1 fibres within a muscle; this allows for long term endurance exercises such as marathons or, in prehistoric times, hunting and gathering. Although this does not suggest the lack of a social divide, it heavily suggests that women were most likely the prominent hunters. Lacy and Ocobock also started to research any key differences within burial rights between the genders. From this they discovered that there was no difference between grave goods or posthumous treatment afforded to men compared to women. There are many notable examples of lavish tombs dedicated to women; the most famous case is the ‘Egtved Girl’, who was found preserved with lavish gifts. As societies grew more structured and complex, the expectations and roles placed upon women shifted in response. Ancient Egypt is the earliest

society in which we can see stereotypical gender roles emerging and men increasingly beginning to dominate the influential positions within society. Ancient Egyptians largely viewed men and women as equal; the gender divide came about as a means of necessity as men performed more physically demanding tasks in order to allow the women to act out the role of motherhood. Women had a very rare status in the ancient world as they could inherit property and money as well as decide which of their children they wanted to pass their assets down to. As well as this, the menstrual cycle was fully recognised, and women could expect the men in their lives to take over the housework and childcare during menstruation. The roles and lives of women were by no means viewed as inferior, but rather different - due to societal needs. Men participated in agrarian culture while women took on tasks such as weaving, pottery, and also housework. The ancient Egyptians would have seen these roles as equal and a way to ensure the harmony amongst nature. However, it is evident that a growing patriarchal structure was slowly limiting women’s participation in certain spheres of life in Egypt. Positions of power and wealth were passed down through the patrilinear line to ensure that the top of society remained male dominated. Gods such as Osiris and Amun helped to reinforce male gendered traits such as leadership, power and creation, while Isis portrayed the archetype of a devoted mother and wife. Although women were allowed to become pharaohs, it was incredibly rare, with only seven recorded. Hatshepsut, the second recorded female ruler of Egypt, and arguably the most fascinating, navigated the maledominated Egyptian patriarchy by adopting traditionally masculine roles. To fully legitimise her reign, she was almost always depicted as a male pharaoh in statues and reliefs, complete with the correct garb and beard. On of her most notable achievements was her expedition to the Land of Punt (modern-day Sudan) in order to successfully re-establish vital trade links and therefore proving her true capability as ruler.

To this day, Hatshepsut is revered as one of Egypt’s most successful and innovative rulers. What makes her legacy particularly interesting is her understanding that adopting traditionally masculine traits and symbols of power would earn her greater respect and legitimacy within the patriarchal framework of ancient Egyptian society.

During the Roman empire, the inferiority of women was deeply rooted within society, shaped by biological assumptions, philosophical teachings and cultural norms. In the midst of this view was the idea that men were better suited for leadership, while women were confined to domestic roles due to their perceived physical weaknesses. The Romans were heavily influenced by Greek philosophers such as Aristotle, who perpetuated the notion that women lacked the rational capacity and moral fortitude that men possessed; this led to their exclusion from political and public life. Aristotle described women as “defective males” due to their physical ‘weaknesses’ and ‘vulnerability’ meaning that they could not carry out the labour-intensive tasks that men could. He viewed women as merely a ‘vessel’ in which a baby is carried and nothing more, and women’s reproductive roles naturally allowed men to assume that their rightful place was inside the domestic sphere. Moreover, Romans carried these views into a patriarchal family structure, within which each family was led by a Paterfamilias who held absolute authority over all members of the household. Romans applied these values to their philosophy as well, in which men were expected to be courageous and dignified and women were expected to embody modesty, loyalty and chastity. Overall, the place in which women were situated in society was due to a woman’s ability to reproduce.