a

Scholars and Soldiers:

history of alumni of St Paul’s School and the 1st World War

Graham E Seel has taught History since 1987. He was Head of History and Head of Faculty Humanities at St Paul’s School, 2012 2021. The author may be contacted on spsworldwarone@btinternet.com

Cover image: SPS OTC Officers and NCOs, 1916. St Paul’s School Archive

Preface

List of Illustrations

Introduction

Part A: those who served the ‘2,914’

1.1 OP volunteerism

1.2 volunteerism: the cases of Kenneth Gordon Garnett (SPS 1904 1911) and Edward Thomas (SPS 1894 1895)

1.3 Chapel, Classics and Competitive Athleticism i) chapel ii) Classics iii) competitive athleticism

1.4 the case of John Sherwin Engall (SPS 1912 1914)

2.1 Army Forms

2.2 Volunteer Corps

2.3 the South African War, 1899 1902

2.4 the Officers’ Training Corps (OTC), 1908

2.5 ‘The Corps is Too Much With Us’

2.6 after the War

3.1 in which they served: armies

3.2 in which they served: corps / regiments

3.3 in which they served: infantry regiments

3.4 in which they served: battalions

5.1 awards won

5.2 OP VCs

Part B: those who fell the ‘511’

Chapter 6. Recording the Fallen: the ‘511’

7.1 Scale of loss 7.2 Deaths by year

7.3 Age at death: a Lost Generation?

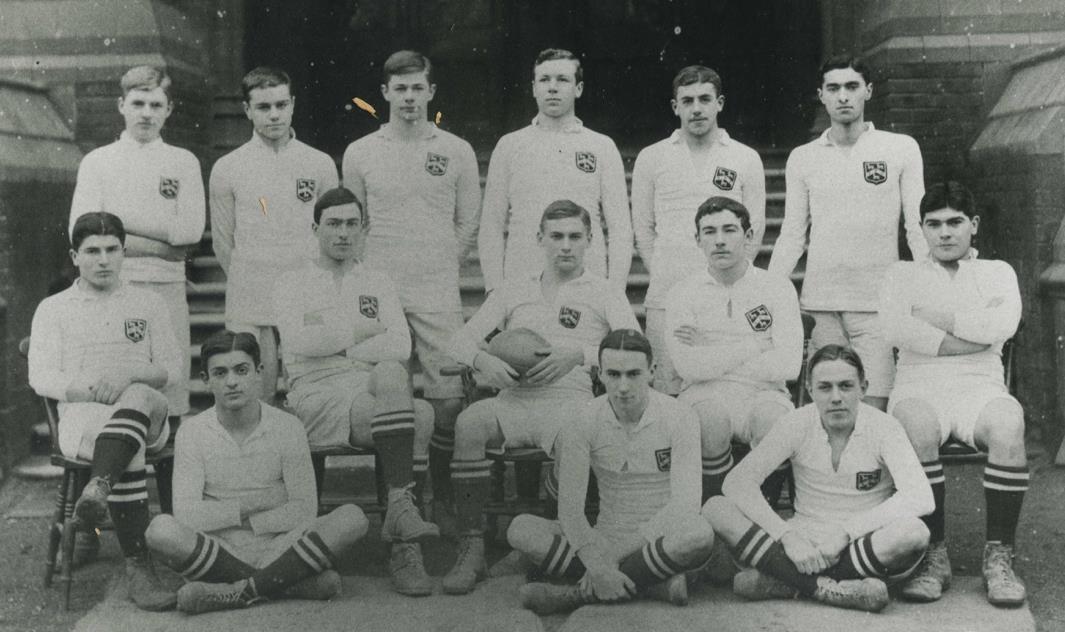

8.1 First and Last i) the first to fall ii) the last to fall 8.2. Youngest and Oldest i) The youngest ii) The oldest 8.3 The deadliest day in SPS military history: 1 July 1916 8.4 Pauline Poets 8.5 Fallen Friends 8.6 A Prisoner of war 8.7 1st XI Cricket, 1912: fatalities and survivors i) 1st XI Cricket 1912: service record ii) 1st XI Cricket 1912: biographies 8.8 1st IV Rowers, 1914: fatalities and survivors i) 1st IV Rowers 1914: service record ii) 1st IV Rowers, 1914: biographies

8.9 1st XV Rugby, 1914: fatalities and survivors i) 1st XV Rugby 1914 service record ii) 1st XV Rugby, 1914: biographies

8.10 Brothers in arms i) brothers Harold Drummond Hillier (SPS 1906 1910) and Geoffrey Stewart Drummond Hillier (SPS 1907 1911) ii) the Campbell brothers 8.11 The only Indian fighter Ace of the 1st World War 8.12 Captains of School

8.13 Spanish Flu, 1918 1921

i) Masters’ service record

ii) Masters who fell: biographies

iii) Servants’ service record

iv) Servants who fell: biography

10.1 criteria for commemoration

10.2 in which they lie: countries

10.3 upon which they are remembered: memorials

11.1 Brotherly ambulance drivers

11.2 Prisoners of war and Internees

i) prisoners of war: Holzminden

ii) Internees: the ‘Ruhleben eight’

11.3 Soldiers of war 11.4 Artists

11.5 Authors 11.6 the rose grower 11.7 the oenophile 11.8 the great survivor 11.9 a modern Don Juan

12.1 Memorialisation

i) the South African War Memorial, 1906 ii) the Memorial Chapel, 1926 a) fund raising b) the memorial panels c) the new chapel, 1926

iii) the 2nd World War commemorative panels

iv) the War Memorial, 2011

12.2 Commemoration

i) Commemorative items

a) the A J W Pearson cricket ball b) the ‘Lambert’ Boat c) the High House memorial tablet ii) commemorative displays

a) Library sponsored displays b) teacher sponsored displays iii) centenary commemorations a) 2014

b) 2018: ‘First World War Research Project’ and inter Faculty projects c) 2018: making and planting of 490 ceramic crosses for the fallen

Appendix 1: volunteers and conscripts the evolving age criteria Appendix 2: letters from serving OPs published in The Pauline

a. Carpenter, John A, Royal Engineers. John was a Master at SPS from 1910 1919. A description of the attack on Hulluch on 25 September 1915, the first day of the Battle of Loos. The letter is dated 29 September 1915.

b. Shaw, Massey Shaw (SPS 1909 1912) 11th (Service) Bn. Middlesex Regiment. Description of an attack near Pozieres, in the Somme sector in late July 1916.

c. ‘F.G.B’, M.D (This is likely Major Frank George Bushnell (SPS 1882 1885); RAMC.) A description of life in a front line medical unit with the Salonika Force.

d. ‘C.N.B’. ‘News from Italy’. (This is likely Lt Col Charles Norman Buzzard (SPS 1885 1890); Siege Brigade, 94th HAG, Italy.) A description of the experience of retreat while serving with the Heavy Artillery e. News from ‘C.S’. A description of becoming a casualty.

f. Anon. An episode in the experiences of an OP flying a single seater scout with two Vickers guns

g. Spaull, Cecil Meckelburgh (SPS, 1911 1915); 87th Punjabis, Indian Army. A description of fighting at Ad Diwaniyah, one hundred miles south of Baghdad.

h. A report received from Lt Batho, John (SPS 1905 1912) in which he describes the capture of a German prisoner.

i. An anonymous account of the lighter side of life in the trenches.

j. An anonymous letter from an OP serving on board HMS Invincible during the Battle of the Falklands 1914. The letter is dated, 10 December 1914.

k. The extraordinary near death experience of Capper, Athol Harry (SPS 1905 1911).

l. A letter from Brilliant, Leopold (SPS 1909 1914) describing his experience while serving with the Indian Army in East Africa.

m. An anonymous account by an OP in the Royal Flying Corps in which he describes the experience of encountering shells while in flight.

n. An account of an attack on a pill box known as Somme Farm redoubt by St Legier, Gerald William (SPS 1911 1914), 2nd Lieutenant in the Devonshire Regiment.

o. Butt, Wheatley Clegg (SPS 1893 1894) recounts his wartime travels.

p. A letter from Lord Esher, referencing an unnamed Pauline who died at Puchevillers on the Somme.

q. A letter from Sams, Hubert Arthur (SPS 1887 1894) referencing OPs in India and describing an OP dinner held in Baghdad

Appendix 3: ‘Letters from the Front’. A curated series of 13 letters from serving OPs published in The Pauline

a. Warner, George Francis Maule (SPS 1910 1913); 1st Bn. Royal Berkshire b. Montgomery, Bernard Law (SPS 1902 1906); 1st Bn. Royal Warwickshire Regiment

c. Doake, Samuel Henry (SPS 104 10); 55th Howitzer Battery

d. Barnett, Denis Oliver Barnett (SPS 1907 1914); 2nd Bn. Leinster Regiment

e. Batho, John (SPS 1905 1912); 54th Field Company Royal Engineers f. Gaunt, Kenneth MacFarlane Gaunt (SPS 1909 1912); 2nd Bn. Royal Warwickshire Regiment g. Ritchie, Arthur Gerald Ritchie (SPS 1893 1897); 1st Bn. Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) h. Woods, Denys (SPS 1905 1907); Army Service Corps, attd. 85th 1/3 London Field Ambulance (Driver)

i. Carlisle, John Edward Gordon SPS 1898 1901); 107th Indian Pioneers, Indian Army j. Scott, Robert H (SPS 1912 1914); Honourable Artillery Company k. Henderson, William Lewis (SPS 1896 1901); 10th (Service) Bn. West Yorkshire Regiment l. Anon.

m. ‘John’

Appendix 4: units, ranks and Order of Battle

Appendix 5: the High Master’s Address 28 Sept 1914

Appendix 6: infantry regiments

Appendix 7: battalions

Appendix 8: an officer’s commission

Appendix 9: summary record of inter Faculty activities during the 2018 centenary commemorations at St Paul’s School

When Graham Seel speaks directly about his research into the 511 fallen Paulines and others of the 2,500 OPs who volunteered for service in the 1st World War, his passion for understanding and recording accurately the history of both the school and its pupils is evident. His work narrates much fascinating hitherto unknown detail about the generations of OPs who fought and as such it will become a key reference work for those interested in St Paul’s School and the 1st World War. I am proud to be part of an institution that facilitated such work and acknowledge its importance. I also feel privileged to have overlapped with Graham during my time as High Master and to have had the chance to discuss its progress with him and to see this project reach its completion. That it did so during a global pandemic, when another group of young Paulines had their lives impacted by factors beyond their control, only served to emphasise further the need to record our unique experiences for those who will follow us.

Whilst Graham’s work seeks to emphasise the numbers of Paulines who survived the 1st World War and had purposeful lives beyond it, it remains the case that it’s difficult for those of us alive today to imagine what life at the front must have been like for them. However, united as we are by our school, we can feel connected to them and to the past in a special way. Therefore, I am hugely grateful to Graham and to all who supported him in this venture.

Sally Anne Huang, High Master, St Paul’s School 2020

One of the highlights of my time as President of the Old Pauline Club has been the honour of laying a wreath at the St Paul’s School War Memorial on Remembrance Day last year. The sky was the clearest blue and there seemed to be no sound of road, air or river traffic just the silence of over a thousand current Paulines remembering and honouring the 511 Paulines from over a century ago who made the ultimate sacrifice. There was such a sense of unity across generations in the silence.

In these wonderful volumes, Graham Seel chronicles the stories of the 511 OPs who fell and others who survived. It is so important that these tales of gallantry and sacrifice are being told. There is nobody better to do that than Graham given the incredible extent of his research and the quality of his writing. The Old Pauline Club extends its congratulations and enormous thanks to him. Scholars and Soldiers is a hugely important addition to the Pauline Community’s knowledge of OP bravery in the First World War.

Graham describes Pauline sacrifice in what was “the war to end all wars” at a time when there is war in Europe again. His book is timely and poignant. Ed, Lord Vaizey of Didcot, OPC President

One of the great privileges of being a Pauline is the sense of being part of a great continuum of learning and endeavour that has continued over many centuries. As governors and Old Paulines our task is to encourage and enable the new generations to share in the great history and the bright future of the school. So while supporting the future development of the school it is vital that we are alive to its past.

Graham Seel has undertaken a massive research project investigating and chronicling the contribution of so many Old Paulines to the First World War and illustrating for us the great diversity of talent that poured into the trenches. In so doing he helps to slay the myth that the soldiers were all fresh from school and heading directly to a muddy grave. Many of them were in their 20s and 30s, the majority of them survived and they participated in a variety of ways and displayed a range of talents. Many continued to have distinguished careers after the war.

It is important, as we look back over the history of the school, to recognise that the First World War dominated the lives of more than a single generation of Paulines and provided a focus for the school life and work that extended beyond the memorials to the fallen. Any study of the history of the first part of the twentieth century must reflect this as well as recognising the contributions of those Paulines who gave their lives willingly and bravely in the service of their country. Graham Seel’s work provides an invaluable record of this period and continues in the great tradition of St Paul’s history by providing a well written and discursive analysis to enlighten the treasure trove of individual stories. This is a great and invaluable resource for historians and for anyone wishing to understand the school of a century ago.

Richard Cassell, Chair of Governors, St Paul’s SchoolWhen I arrived at St Paul’s in 2011 there was no unifying memorial to the Old Pauline fallen and no annual remembrance service. My son had just started at Bishop’s Stortford College, and he rang me on the evening of 11 November to relate how they had heard in their remembrance service of the sacrifice of nearly five hundred Old Paulines in the Great War. Over the next couple of years, a disjuncture between Pauline sacrifice and commemoration was rectified: a small group of staff (notably Richard Girvan, Eugene du Toit and Patrick Allsopp), pupils (notably Joshua Greenberg) and the Old Pauline Association rallied energetically, and soon a whole school service of remembrance was introduced and an inscribed memorial stone unveiled.

But something was still missing. Whenever I looked at those stilted sepia pre war photographs of Paulines, dressed in ceremonial blazers and caps, and whenever I read about their athletic proficiency (and their years in this XI or that XV) in the stiff language of The Pauline magazine, they appeared detached, almost fictional, characters. I related to them as Paulines, but not as human beings.

Not any more. Graham Seel’s painstaking and passionate research rescues 511 Paulines from the anonymity of mass mortality. It replaces sepia with colour. His biographies reveal how various Paulines some irascible, some dubious, some sensitive, some formidable, many courageous wrestled with their conscience and died as a consequence. Graham Seel interweaves their lives with detailed reconstructions of their deaths: in many cases, he can identify where and how they fell, details which were seldom known to their loved ones.

Read in these pages about the Pauline who could throw a cricket ball further than any other, who could hurl grenades clean across no man’s land, who crawled through human detritus in the Hooge crater on a hot August morning, and who died with quiet dignity despite appalling abdominal wounds in a crowded dressing station: in so doing, the fallen are restored as human beings for posterity.

Mark Bailey, Professor of Later Medieval History, University of East Anglia, High Master, St Paul’s School, 2011 - 2020

The origins of these three volumes lie in a project undertaken by a group of pupils working under the auspices of the History Department in 2014, culminating in the production of the commemorative booklet ‘St Paul’s School and the First World War’. It was clear from this exercise that the school magazine The Pauline was simultaneously an astonishingly rich and remarkably underused repository of many of the stories of OPs who fell in the war. Thus, during the years 2014 to 2018, encouraged by the various national centenary commemorations, periodic further use was made of The Pauline, along with other materials in the St Paul’s School Archive, in order to reconstruct the experiences of some of the OPs who lost their lives. Over the same period the school Act of Remembrance evolved to become a whole school occasion, including St Paul’s Junior School, and several commemorative events took place, notably the planting of 490 crosses at the base of the War Memorial in 2018.1 From all of this it became increasingly clear that there was a requirement for a robust, comprehensive history of OPs who served in the war, for more of their stories to be uncovered and for others to be yet more thoroughly researched, and for their graves / memorials to be identified. What follows is an attempt to fulfil these requirements.

Many colleagues have helped in the production of this work, and I hope that I have duly acknowledged their various contributions in a relevant footnote. During the Summer Term of 2020 my colleagues in the History Department, already squaring up to the peculiar challenges posed by the pandemic, gracefully shouldered most of my teaching timetable to allow me to undertake sabbatical leave. I am particularly grateful to Hilary Cummings and her team in the St Paul’s School Library. Ginny Dawe Woodings, the School Archivist, has been unfailingly helpful. Valerie Nolk has been supportive throughout. Owen Toller, Mike Howat and Simon May read either parts or all of the manuscript and drew my attention to infelicities. Michael Grant and Matthew Smith provided indelible good cheer during visits to Ypres. John Knopp has shown endless patience in dealing with my questions military I am grateful to my family for giving me the space to research and to write and for coining the new verb: ‘to trench’ Finally I wish to thank the Governors, Mark Bailey and Richard Girvan for accommodating my request for sabbatical leave, thereby presenting me with time and resources for the laying of the groundwork for what follows. I appreciate that sabbaticals are increasingly difficult for school authorities to finance and to justify and I hope that the present work goes at least some little way to recompense their faith in me.

1

The figure of 490 is obtained from the number of names of OPs listed as fallen in the first part of the War List. This work revises this number to 511. (See Chapter 6.)

Volume 1: 'Soldiers and Scholars'. Images, charts and tables.

Part A: those who served - the ‘2,914’

Chapter 1 ‘All roads lead to France’: part one

A.1 Number of OPs who volunteered for service in the 1st World War by the year in which they left SPS

A.2 The grave of Kenneth Gordon Garnett

A.3 Rev Albert Ernest Hillard, High Master 1905 1927

A.4 Rugby Football match taking place on St Paul’s School playing fields. Denis Oliver Barnett is on the right of the picture, to the left of the coated figure

A.5 Trench map showing the section of German trenches attacked by 1/16th Bn. London Regiment (‘QWR’) on 1 July 1916

Chapter 2 ‘All roads lead to France’: part two

B.1 The Woolwich Army Form, winners of the Challenge Shield 1891

B.2 Caricature of Charles Pendlebury

B.3 Randolph Nesbitt pictured wearing his VC on a card inside Ogden’s Cigarettes

B.4 The unveiling of the South African War Memorial, 29 May 1906

B.5 The St Paul’s Shooting Team, Bisley, 1913

B.6 OTC officers 1916

B.7 A battalion parade on the school grounds

B.8 The OTC band during the Annual Inspection

B.9 An OTC Field Day in Richmond Park, 1915

B.10 An OTC Field Day in Richmond Park, 1915

B.11 OTC Field Day in Richmond Park, 1915

B.12 A kit inspection taking place at the Annual Camp in 1914, at Mytchett Farm, Aldershot.

B.13 The OTC Annual Camp, Salisbury Plain, August 1916

B.14 Annual OTC inspection by Brigadier General Broadwood 1915

B.15 The Annual Inspection June 1917. Undertaken by Lt Col W T Bromfield

B.16 SPS OTC Officers and NCOs 1916

B.17 SPS OTC Officers and NCOs 1916

B.18 St Paul’s School OTC badge

B.19 St Paul’s School OTC cap badge

C.1 Chart showing the proportion of OPs serving in the British Expeditionary Force, Indian Expeditionary Force, Canadian Expeditionary Force and Australian Expeditionary Force

C.2 Table showing the number of OPs who served in each of the main corps / regiments in the BEF

C.3 Table showing Infantry Regiments by army precedence and the number of. of OPs who served in each

C.4 Chart showing the five regiments most patronised by OPs

D.1 Table showing the number of OPs who served in each of the main ranks of the army and the percentage loss in each rank

E.1 Table showing number of gallantry medals awarded to OPs

E.2 Map dated 8 April showing Rossignol Wood and the trench systems in the associated area

Part B: lives lost the ‘511’

Chapter 6 Recording the Fallen: the ‘511’

F.1 The Pauline, July 1917. ‘Our Roll of Honour’

F.2 Roy (Richard) Hill’s grave at Thornton Dale (All Saints) Churchyard, Yorkshire

F.3 Table summarising methodology for obtaining the total number of OPs who fell

G.1 Percentages killed of those who had attended public schools in which the total number of Old Boys who served was at least 2,000

G.2 Table showing OP death rates in the main Corps of the Army

G.3 Table showing OP death rates in the RFC / RAF and Navy

G.4 Table showing scale of OP and OU deaths by year

G.5 The St Paul’s Shooting Team, Bisley, 1913

G.5 Chart showing the average age of death of OPs by the year in which they fell

G.6 Chart showing the age at death (in five year age categories) of the 511 OPs who fell

G.7 Chart showing the number of OPs who volunteered and the number of OP deaths in each of the annual leaver cohorts, 1890 1918

G.8 Chart showing the proportions of deaths Vs survivors of all OPs who served

H.1 Charles Bayly’s reconnaissance notes

H.2 Image of the crashed Avro 504 No. 390 with likely Charles’ charred body in the foreground

H.3 Table showing OPs who fell before their 19th birthday

H.4 George Morris’ grave

H.5 Image of an Avro 504J aircraft

H.6 Image of a replica of a DH5

H.7 HMS Furious in 1918

H.8 HM Hospital Ship Glenart Castle

H.10 OPs who fell at the Somme, 1 July 1916

H.11 Map showing trenches F.11.6, F.11.7 and F.11.8 in which 9th (Service) Bn. Devonshire Regiment formed up in the early morning of 1 July 1916

H.12 Map showing the British frontline (blue) and German trenches (red) in front of Mametz

H.13 Panorama (contained in the 20th Brigade) diary looking north from behind Mansel Copse

H.14 Devonshire Cemetery, Mametz

H.15 Table of Pauline poets who fell

H.16 Trench map showing Aps Wood

H.17 Map showing the M1 Sector and Point 127

H.18 Map showing the disposition of Companies of 1/4th Bn. Seaforth Highlanders in front of Cantaing on 21 November 1917

H.19 Map showing the likely location in which Robert Vernede was shot.

H.20 Trench map showing the location of the Strong Point (X.3.a.9.5) attacked by Eyre and Ian

H.21 Gutersloh POW Camp, July 1916

H.22 1st XI Cricket team, 1912

H.23 1st XI Cricket, 1912: service record

H.24 Trench map dated 26 June 1918 showing the German Strong Points Suffolk and Essex

H.25 1st IV Rowers, 1914

H.26 Table showing 1st IV Rowing, 1914 service record

H.27 1st XV March 1914

H.28 1st XV Rugby 1914, service record

H.29 Map showing the position of 23rd Field Company at the time that Caleb Grafton undertook his reconnaissance

H.30 Map submitted with Caleb Grafton’s Report

H.31 Plate IV (Part of Caleb Grafton’s Report)

H.32 Map showing the trench system in the vicinity of the Hohenzollern Redoubt

H.33 A sketch by Harold Hillier of his billet when at Lacouture, 26 June 1916

H.34 Map of trenches in the vicinity of the Boar’s Head

H.35 Map drawn by Harold Hillier showing Geoff Hillier’s final movements

H.36 Harold Hillier’s sketch of four graves

H.37 Table showing the service record of the Campbell brothers

H.38 The distinctive Commonwealth gravestone under which James and Ronald lie with the Campbell of Jura Mausoleum behind the railings

H.39 A sketch by Laddie of a Sopwith Camel

H.40 The commemorative stamp of Indra Lal Roy, issued by the Indian postal service in 1998

H.41 Indra Lal Roy’s Commonwealth grave in Estevelles Communal Cemetery

H.42 Captains of School killed in action

H.43 Trench map showing Haussy / Haussey

H.44 An 18 pounder Field Gun, similar to that in 307th Brigade

H.45 The memorial tablet commemorating Lewis Bryett in St Paul’s Church, Hammersmith

H.46 Map showing Ancona Farm, Adelaide House, Mutual Farm, a short distance north of Menin H.47 Map showing the points of reference used in the battalion report of the action against Ooteghem

H.48 Cross marking Thistle Robinson’s grave H.49 Table listing OPs who were probably victims of Spanish Flu H.50 Reggie Schwartz, bowling, c. 1905

I.1 Masters’: service record

I.2 A postcard of HMS Vanguard at sea I.3 Servants’ service record

J.1 Table showing numbers of OP graves / memorials in various countries

J.2 The grave of Francis Jack Chown (SPS 1912 1916) in Hooge Crater Cemetery, nr. Ypres

J.3 The family grave of Henry Augustus Mears (founder of Chelsea Football Club) and his son, Flight Lt Henry Frank Mears (SPS 1915 1915) in Brompton Cemetery

J.4 Chart showing the proportions of OPs with a memorial Vs grave

J.5 The Menin Road by Paul Nash (SPS 1903 1906)

J.6 Table listing the memorials and cemeteries in which the greatest concentrations of OPs are found

J.7 The Ploegsteert Memorial.

J.8 The Ploegsteert Memorial.

J.9 Panel 54 on the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial

Part C: lives lived the ‘2,403’

K.1 The image of the School Ambulance sent to the High Master by Captain Fairbank

K.2 The 85th (1/3 London) Field Ambulance on the road near Marseilles, preparing for its move to Egypt

K.3 Image of a Nieuport 23

K.4 A sketch of Ruhleben Camp

K.5 Old Paulines at Ruhleben Camp

K.6 The model of his barrack that Geoffrey Pether built 1915 1916

K.7 Part of a ten page Extract of Messages received and sent, and brief diary of the course of operations 7/8 April 12 April 1917

K.8 A Lamp of Maintenance

K.9 The effigy of Tubby Clayton in All Hallows by the Tower

K.10 A hand drawn map (probably by Colonel Wilcox, Devonshire Regiment) of the North Russian theatre

K.11 1st XV 1906 1907. Monty is Captain, seated in the middle

K.12 List of casualties incurred by the 104th Brigade units fighting on the Somme 19 27 July 1916, signed ‘B. L. Montgomery’

K.13 Portrait of Bernard Law Montgomery by Denis Fildes, 1956

K.14 Claude Ridley pictured in a Morane ‘bullet’

K.15 The blue plaque in Sunderland commemorating Claude Alward Ridley.

K.16 Trench map showing the section of line held by the Kensingtons on 15 December 1914

K.17 The Kensingtons at Laventie

K.18 Poster by Eric Kennington, advertising his exhibition The British Soldier

K.19 Eric Kennington’s Memorial to 24th Division in Battersea Park

K.20 A painting by Paul Nash, Spring In the Trenches, Ridge Wood, 1917

K.21 A ‘Drachen’ type balloon is held steady over HMS Manica, 1915

K.22 The Handley Page O/100 aircraft 1459, in which Paul Bewsher flew

K.23 A trench map showing the section of trench S9A , in the ‘D’ box occupied by Basil Liddell Hart

K.24 Map showing Bazentin le Petit Wood and The Bow / Flatiron Trenches at the southern end of Bazentin le Petit Wood

K.25 Poster for the film Atlantic (1929)

K.26 Map showing Ain Karim, the hill top town that fell to 2/13th Bn. Kensingtons

K.27 The collapsed bridge at Masnieres

K.28 A Caquot balloon ascending near Bruary, 10 July 1916

K.29 Image of the wreckage of the Nieuport A6671 in which Vivian Burbury was flying K.30 Vivian Burbury’s medal group

Part D: ‘we will remember them’

Chapter 12 Memorialisation and commemoration

L.1 The South African Memorial, unveiled by Lord Roberts on 29 May, 1906 L.2 A Norman Wilkinson poster featuring the South African Memorial, commissioned for the London Midland and Scottish Railway in 1938

L.3 The memorial panels in the new General Teaching Block, 2020

L.4 A close up of one of the panels, showing the lettering designed by MacDonald Gill L.5 The Old Library before its conversion into the Memorial Chapel L.6 MacDonald Gill’s drawing of the Memorial Chapel L.7 The Memorial Chapel L.8 An image of the Chapel showing the panels, lectern, altar and altar furniture

L.9 The lectern presented in memory of J. C. and H. W Hutchinson. The memorial plaque is just visible

L.10 The lectern praying kneeling stand commemorating the brothers W J Harding and R W F Harding

L.11 The 2nd World War memorial panels hung on a corridor wall in the new General Teaching Block

L.12 The War Memorial located adjacent to the Milton Building

L.13 Joshua Greenberg reading at the Service of Dedication for the new War Memorial, 11 November 2011

L.14 The Pearson cricket ball with attached plaque, most likely used in the match played against the MCC on 25 July 1914

L.15 The ‘C. J. N. Lambert’ boat (at the bottom of the picture) in the Boathouse

L.16 The High House tablet

L.17 Dobbin’s’ Memorial Plaque (also known as the ‘Dead Man’s Penny’)

L.18 Stephen Baldock (High Master 1992 2004) photographed in the Atrium on 11 November 2011 with one of the memorial boards created by Suzanne Mackenzie

L.19 The front cover of St Paul’s School and the First World War, published in 2014 L.20 Images of two of OPs listed in the Roll of Honour, hung on the corridor wall outside the Faculty Humanities Resources Room

L.21 A poster created by Biology students George Langstone Bolt and Milo Taylor L.22 4th Form boys in the process of making the 490 crosses, 2018

L.23 Three of the 490 crosses made by members of the 4th Form, 2018

L.24 Some of the 490 crosses planted at the base of the War Memorial L.25 Framed research into Indra Lal Roy, undertaken by Valerie Nolk

L.26 Two of the crosses, framed and hung in Reception

13

M.1 Front cover of the order of service for the Memorial Service at St Mary Abbot’s, 12 November 1919

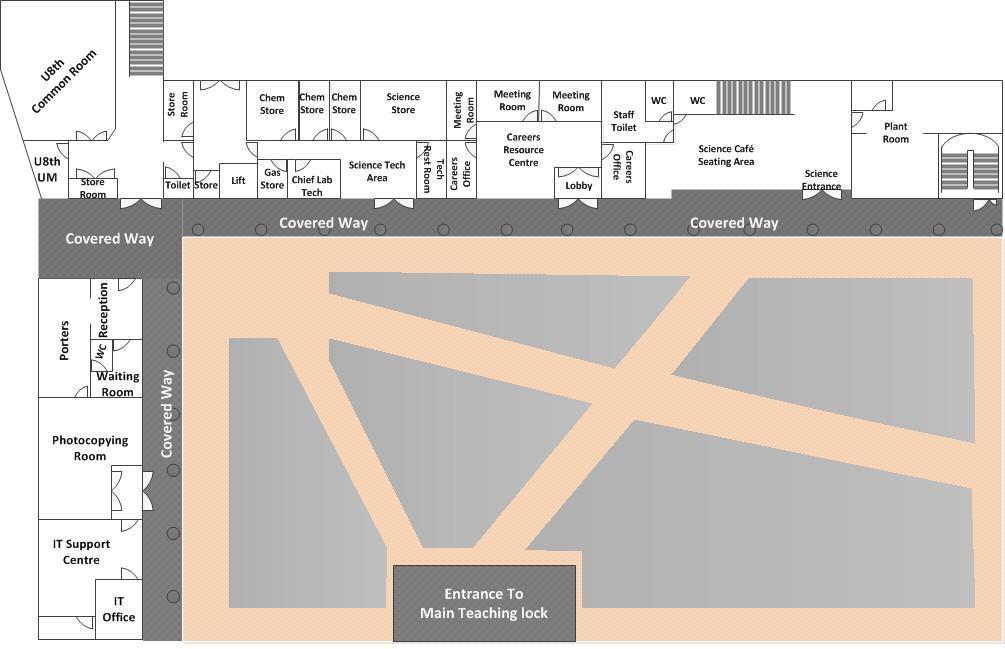

M.2 Plan of Founder’s Court detailing the locations in which Tutor Groups were to gather in 2014

M.3 Pupils gather in Founders’ Court ahead of the Act of Remembrance, 2014 M.4 The order of service for Remembrance Day in Founders’ Court, 2014 M.5 The 2018 Remembrance Day Service on Big Side in 2018

Chapter 14 Last Word

Chapter 15 Roll of Honour the 511

Appendices

The overall ambition of this work is to provide an accessible record of alumni of St Paul’s School who enlisted during the 1st World War. This material is presented in two volumes, with a supplementary third volume containing maps and photographs of many of the places mentioned. The purpose of Volume 1 (‘Service and Commemoration’) is threefold: 1) to recognise the number of OPs who fought in the 1st World War and to comprehend their reasons for so doing; 2) to identify, quantify and reveal the stories of OPs who served in the war, 511 of whom fell; and 3) to provide a record of the activities and enterprises undertaken by the School to ensure that these OPs are not forgotten. Volume 2 (‘The Ypres Salient and the ‘93’) identifies OPs who fell in the Ypres Salient and uncovers their stories.

The material assumes a broad knowledge of the context of the war the reader who wishes to engage with the historiography of the War will have to look elsewhere.2

Volume 1 is composed of five parts, A E. Part A identifies the total number of OPs who served in the war, the units in which they fought and the ranks and awards they achieved. Of this number 2,914 many were volunteers, encouraged to enlist by the culture of their public school and equipped early with martial prowess by means of a vigorous Officers’ Training Corps (OTC), an institution that became such a feature of many Paulines’ lives that some considered it was ‘Too Much With Us’.3 With the introduction of conscription in January 1916, volunteering ended. Thereafter, everyone who fulfilled certain criteria was obliged to go to war and from this date onwards it becomes impossible to perceive distinctly the extent to which OPs willingly undertook service.4 All that can be said is that the records and the data offer very little indication of recalcitrance and it thus seems likely that most OPs maintained a desire to participate in the war. Harry Waldo Yoxall (SPS 1908 1915, see Chapter 11, Section 11.7) Captain of School in 1915, admitted his discomfort after deciding to stay on to take the Balliol Scholarship before joining up. A keen member of the OTC, he confessed that:

2 Sheffield, G Forgotten Victory The First World War Myths and Realities provides an accessible overview (Headline, 2002)

3 One lunch break a week was given up to an OTC drill parade and part of the margin of the school grounds was grimly decorated with gallows from which hung straw filled sacks into which the novice would be trained to plunge his steel. Wednesday afternoons and sometimes Saturdays were taken up with OTC. See Chapter 2, Section 2.5.

4 See Appendix 1

The Officers’ Training Corps was a partial salve to conscience, and the cadet uniform at least a protection against white feathers. It was difficult to lead a school affected by impermanence, with the elder boys slipping away each week into the HAC [Honourable Artillery Corps] or the Public Schools’ battalion of the Royal Fusiliers.5

Harry’s example is unusual. In numerous cases boys left school earlier than they would normally have done. Most felt that it was their duty to do so; for most, all roads led to France.

Part B revises the generally accepted figure of 490 OPs killed in the war and replaces it with that of 511. This figure represents 17.5 percent of the total number who served, slightly lower than the death rate across all 185 public home and overseas schools.6 After a century of exposure to the ‘pity of war’ poetry of Wilfrid Owen and its associated narrative that the 1st World War begot only death, it comes as something of a shock to learn that for every OP who fell, four survived. The data also encourages a revision of the generally accepted notion that those who fell were by and large very young males composed of a tightly knit cohort who only recently had sat in the school classroom and run on the school playing field. Instances of OPs dying at a very young age exist, but they are few and far between. Their examples evoke a noisy, melancholic sentimentality frequently amplified by the pens of the war poets. In fact, the average age of death of all 511 OPs who fell was 27 years. In 1914 it was as high as 30 years, and never lower than 26 years (in 1917). The data also shows that OPs volunteered from multiple cohorts of leavers stretching back for decades prior to 1914. St Paul’s endured a loss, but it did not suffer a ‘Lost Generation’. Finally, as the stories of the OPs presented here show, there is almost no evidence to support the popular notion that OPs generally fought and fell shoulder to shoulder. Mostly of officer rank and of differing ages, OPs were deployed as leaders across multiple units, a diaspora that thwarted any possibility of a Pauline ‘band of brothers’ stalking the trenches. Indeed, it is of note that OPs often took care to mention in their letters those occasions when they encountered a fellow Pauline at the front, thereby perhaps suggesting the infrequency of such an event.7 The final chapter in Part B identifies the cemeteries / memorials in which the 511 OPs are buried / remembered. The 511 are to be found in all parts of the world, though their greatest concentration is in France and Belgium. It is chilling testimony to the character of the war that 35 percent of OPs who fell have no known grave.

5 Quoted in Mead, A H A Miraculous Draft of Fishes: the history of St Paul’s School (James and James, 1990), p 102

6 See Seldon, A and Walsh, D Public Schools and The Great War The Generation Lost (Pen and Sword, 2013) pp 255 261

Part C narrates the stories of some of the 2,403 OPs who survived the war. Many of these not only had extraordinary wartime experiences but went on to equally extraordinary achievements in their later lives.

Part D details the various projects and activities undertaken by the School to memorialise and to commemorate the 511, and latterly, others who have fallen in later conflicts, from the end of the war in 1918 to the present day. High Master Hillard (1905 1927) reflected upon the process of memorialisation as early as 1916. In his Apposition address of that year he read from a letter of Denis Oliver Barnett (SPS 1907 1914, see Volume 2), Captain of School in 1913 and 1914, killed by a sniper’s bullet at Hooge (in the Ypres Salient) on 16 August 1915, age 20. Denis had written that ‘It is only the selfish part of us that goes on mourning. The soul in us says Sursum Gorda.’8 (Translated as ‘Lift up your hearts’.) Hillard told his audience that he intended to have these words inscribed on the memorial to Old Paulines after the war, an ambition that for whatever reason remained unfulfilled. The reader may consider that this noble sentiment has been achieved nonetheless by the projects and activities herein described, and no doubt by ones yet to be conceived. Part D concludes with the Roll of Honour.

Part E contains ten appendices. Appendices 2 and 3 consist of letters composed by OPs serving in various theatres of the war and published in The Pauline. Together they provide a compelling, if eclectic, insight into OPs’ experiences of the war.

Volume 2: the Ypres Salient and the ‘93’

Volume 2 is composed of two Chapters. Chapter 16 provides a description of the character of the Salient and presents an overview of the 93 OPs who fell in this place. It includes a Roll of Honour of the ‘93’. Chapter 17 narrates in detail the stories of each of these 93 OPs, thereby presenting a compelling case study of the experiences of those of junior officer rank who fought and fell in the Ypres Salient 1914 1918.9 The stories of the 93 OPs are presented in the sequence in which they fell rather than alphabetically by surname. This arrangement means that if the reader chooses to read the material en bloc they will thus gain an outline chronological narrative of the pattern of the war in the Salient.

Volume 3: maps and photographs of the Ypres Salient

8 The Pauline, Vol 34 14 Nov 1916 No. 228 p 157. High Master Hillard’s Apposition Address, 26 July 1916.

9 The number of OPs with no known grave in the Salient is appreciably higher (48 percent) than for all who 511 OPs who fell (35 percent), testimony to the particularly grim conditions that prevailed in the Salient.

This volume contains a series of photographs and maps relevant to the stories of the 93 OPs who fell in the Ypres Salient

All sources are identified in footnotes. Inter alia, extensive use has been made of the school magazine, The Pauline, and the WO95 war diary material at The National Archives (TNA). I am grateful to the families Hansell and Hillier for allowing me to use material from their respective family archives.

Every effort has been made to identify holders of copyright material. The author would be grateful to hear from any such holder not hitherto contacted.

The war was almost a year old when, on 28 July 1915, nineteen year old Harry Waldo Yoxall (SPS 1908 1915, see Chapter 11, Section 11.7), Captain of St Paul’s School, gathered his notes and strode onto the stage in the Great Hall. In front of him were arrayed the customary gathering of dignitaries and associates parents, OPs and current Paulines, among whom many of the prize winners in this last group were attired in the khaki uniform of the OTC rather than the previously obligatory evening dress. The occasion was Apposition, the school’s anciently instituted Speech Day, the first since the outbreak of the war on 3 August 1914.10 The proud, boastful words of the High Master’s Address still hung in the air. He had told his listeners that :

Many times in his life he had been proud to be a schoolmaster. He was prouder than ever today; prouder still to be a master of an English public school, and proudest of all to be the master of that School. … All the boys who had the stamina to do it were postponing the avocations for which they had been preparing, in order to take up some patriotic service for their country, either in connection with fighting or munition work. About 1,800 old boys were now engaged in fighting.11

Of this number, 83 OPs had thus far fallen in the conflict, their average age 29 years; 36 had no known graves, testimony to the industrial scale character of the war now waging.

12

10

The first Apposition appears to have been held in 1581. McDonnell, Michael F J, A History of St Paul’s School (London, 1909) p 136

11 The Pauline, 33 221 Oct 1915 p 203

12 St Paul’s School Archive

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

Continuing the theme established by the High Master, the Captain of School asserted that:

It is better to read in the papers of Old Paulines joining the forces, mentioned in dispatches, honoured with the various medals and orders, even dying or rather, more than anything, dying than to read of their exploits at Lord’s, or Henley, or Queen’s Club. It is finer to feel that one belongs to a corporate body which has this year sent nearly two thousand of its members to fight for their country than, as in an ordinary year, to one which has produced, say, three Blues, a Craven Scholar, and the bestselling novelist of the year. The war has enabled one to feel the bond between present and past Paulines, not only between those still here and those now fighting for us, but between this generation and men like Marlborough [OP] and still more Milton [OP], very much more nearly than before, and to take an even greater pride in our School. We have indeed always been proud of it, but never so conscious of our pride. And now this year is over, and many of us must go. Most who are leaving are joining one or other of His Majesty’s forces: and it is only the thought that I am going to an even greater school the school of the British Army that can reconcile me to leaving this place and mitigate my regret at saying what I know must be my last word as a scholar of John Colet’s foundation.13

Harry duly enlisted in the 18th (Service) Bn. King’s Royal Rifle Corps, rising to the rank of Captain. He served with distinction, winning the MC. Harry survived the war and became Chairman of Vogue and a renowned oenophiliac. He died in 1984.

What were the influences and pressures that motived Harry and so many other OPs to volunteer? Why was the impulse to fight so powerful that it trumped any contrary sensation? Above all, what formed the sentiment articulated by Harry that the greatest honour was begot by ‘dying or rather, more than anything, [by] dying’.

As shown in chart A.1, the cohorts of Paulines who left the school in each of the years 1914 and 1915 represent the high water marks of Pauline volunteerism. In these two years it seems that practically every leaver volunteered to serve 168 in 1914, and 158 in 1915. The High Master reported at Apposition in 1915 that:

The usual honours in the School had been won. The number of scholarships won at Oxford and Cambridge was seventeen, with two at the hospitals. [However], most of these boys were not going into college, but were taking the King’s commission. All the boys who had the stamina to do it were postponing the avocations for which they had been preparing, in order 13 The Pauline, 33 221 Oct 1915 p

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

to take up some patriotic service for their country, either in connection with fighting or munition work.14

A.1 Number of OPs who volunteered for service in the 1st World War by the year in which they left SPS.

No. of OPs Who Serve By Year of Leaving, 1884 - 1918

160

140

120

OPs

100

80

180 No. 0f

60

40

20

0

Year of Leaving SPS

The decline in numbers of OPs serving from 1916 at first strikes as peculiar, especially considering that conscription became operative from January of that year, obliging all single men to enlist age 18 41 years. (See Appendix 1.) This downward trend is probably best explained by the school population on average becoming younger rather than any recalcitrance to enlist The haemorrhaging of older boys Harry Yoxall had observed ‘the elder boys slipping away each week’ was facilitated by the absence of any legal obligation to remain at school to age 18 and by the established practice of boys departing at the end of any one of each of the three school terms, not only at the end of the summer term as is the current practice. Similarly, many boys who sought a scholarship and had thus traditionally stayed at school beyond the age of eighteen, seem likely to have enlisted directly, perhaps in an ambition to ‘bag’ a temporary commission in a ‘smart’ unit like the Public School Brigade. Indeed, at least in the early stages of the war, there was a palpable sense that a failure to act quickly would mean missing out altogether, either because the war would prove short lived or because of a belief that there were simply not enough commissions to go around. As the official history of the University and Public Schools Brigade put it: ‘So 14 The Pauline, 33 221 28 October 1915 pp 203 204

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

great was the flood of applications for the limited number of commissions available [after Lord Kitchener’s appeal on 5 August for the first 100,000 men for the New Armies] that it soon became apparent that applicants not immediately successful would probably have to wait a long time before they could hope to obtain commissions’.15

Also evident in chart A.1 is the fact that it was by no means only boys who left the school during the war years who volunteered. A majority (81 percent) of the 2,914 OPs who were at one time in the service of His Majesty’s armed forces 1914 1918 presented from each cohort that left the school between 1884 and 1913.16 (In addition, a further 37 OPs who served had been at the school before it moved to Hammersmith in 1884, the oldest of whom Joshua Duke (SPS 1856 1863 was age 67 in 1914.17) Practically all OPs at university, who were physically fit, presented for service.18 The fact that the impulse to serve cut so deeply into the OP community meant that many careers were placed on hold and many retirements abruptly ended; for many OPs, it also meant undertaking a long and difficult journey back to Britain. The High Master reported at Apposition in 1915 that ‘Numbers of [OPs] had come from distant parts of the Empire, from India, China, Canada, the States, Ceylon, the Gold Coast, from sheep farming in Patagonia. There was hardly a part of the world from when Old Paulines had not come home to serve their country.’19

1.2 volunteerism: the cases of Kenneth Gordon Garnett (SPS 1904 1911) and Edward Thomas (SPS 1894 – 1895)

The stark figures presented above suggest that the majority of OPs exhibited an unqualified impulse to volunteer. This was certainly true of Kenneth Gordon Garnett (SPS 1904 1911) and no doubt many others. The response of some, however, such as Edward Thomas, was more circumspect. A small number was actively hostile: George Douglas Howard Cole (SPS 1902 ?) became a conscientious objector and was prominent in the campaign against the introduction of conscription.

15 The History of the Royal Fusiliers ‘UPS’, University and Public Schools Brigade, The Times (London, 1917) p 14

16 The number 2,914 is obtained from the SPS War List. Hillard reported at Apposition in July 1915 that ‘about 1,800 of our old boys were now engaged in fighting’. The Pauline 33 28 October 1915 No. 221 pp 203 204

17 A career soldier, Joshua had served as a medic in the Afghan War of 1878 1880, about which he wrote a memoir. He rejoined the service on 31 December 1914 and served in York Place Indian Hospital in Brighton and, from 31 December 1915, in a hospital in Bermondsey. He died on 13 February 1920, age 72.

18

The Pauline, 33 221 28 October 1915 pp 203 204

19 The Pauline, 33 221 28 October 1915 p 203

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

Garnett, Lt Kenneth Gordon MC b. 30 July 1892; d. 22 August 1917

SPS 1904 - 1911 111th Bty RFA Putney Vale Cemetery Age 25

Kenneth Gordon Garnett20

On 30 July 1914 Kenneth Gordon Garnett (known as Ken), the son of Dr William Garnett and his wife, Rebecca, was enjoying his twenty second birthday at the family home in Hampstead.21 A brilliant scholar and a great athlete with a looming presence (he stood six foot and five inches in his socks), he had much to celebrate. After leaving St Paul’s (1904 1911) he went up to Trinity College, Cambridge in October 1911 and the following summer obtained a First Class in the First Part of the Mathematical Tripos. The month of August he habitually spent in the Alps, on one occasion summiting the Matterhorn and, on another, climbing the Lyskamm and four peaks of Monta Rosa in a single day. In his second and third years at Cambridge Ken divided his time between rowing and reading for the Mechanical Sciences Tripos. Increasingly impressive on the water, he rowed at No. 5 in the Cambridge

20

SPS Archive Box 296 Kenneth Gordon Garnett Biography (London, 1918). Facing page 30. 21 Ken’s two elder brothers also attended SPS: James Clerk Maxwell Garnett (SPS 1893 1899) and William Hubert Stuart Garnett (SPS 1894 1900). All three brothers attended Trinity College, Cambridge. James did not serve in the war. He went on to become the General Secretary of the League of Nations Union.

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

Eight that defeated Oxford by four and a half lengths on 28 March 1914.22 As dusk bled into evening on that 30 July Ken’s future looked sparkling and bright.

About 9.30 pm the convivial birthday party was interrupted by someone who had obtained a copy of the evening paper. No doubt breathless with an excitement tinged with trepidation, they announced that: “Negotiations have been broken off between Austria and Serbia; we shall have war”.

Ken turned to those around him and said unhesitatingly: ‘Of course we must go’.23

Ken was as good as his word and enlisted within weeks of the outbreak of war. Initially he joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and engaged for four and a half months (September December 1914) in the arduous duties of mine sweeping, serving on a vessel commanded by his brother, Lt Commander William Herbert Garnett, (SPS 1894 1900).24 Upon receiving a commission, Ken transferred to the Royal Field Artillery in January 1915, serving with the rank of Lieutenant in 111th Battery, 24th Brigade.

Ken sent home a steady flow of letters, their contents on occasion at once whimsical and serious in equal measure. On 1 November 1915 he informed an acquaintance that:

Life is good out here, despite the great depth of mud and the fact that we live in dugouts. … But the mice or rats run all over one’s bed, and face, at night time. I had one that seemed to want to build a nest on my face … Of course, it may have been mere affection for me, or perhaps it was tired and wanted to sit down.25

In a letter of 19 December 1915, that must have caused his mother a good deal of consternation, Ken described related how:

At 5.30 am the enemy machine guns started making a beastly noise, and soon afterwards Blakemore, our Captain, came into my room in a tremendous hurry “gas attack, tumble out quickly [gas] helmets on”. So I shoved on a coat and a pair of gun boots, a helmet and dashed out to the guns. We had already opened fire when I got there, but the sentry had not warned the men that it was a gas attack as a result they all got a dose before they

22 The race was filmed and can be viewed here: https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch oxford and cambridge boat race 1914 online

23 SPS Archive Box 296 Kenneth Gordon Garnett Biography (London, 1918) p 21

24 William Herbert Stuart Garnett known as Stuart transferred from the RNV to the RFC and was killed at a flying school on 21 September 1916, age 34. He had attended Trinity College, Cambridge. William known as Stuart is buried in Upavon Cemetery.

25 SPS Archive Box 296 Kenneth Gordon Garnett Biography (London, 1918) p 25

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

returned to put on their helmets. I couldn’t get the beastly tube mouth piece for exhaling to work the rubber had stuck and so I soon got in a bad way. … It was very bad in the [gun] pits … I felt sure we were done in though I was not in a funk I told the men (and I had to shout through the helmet) to trust in Jesus and this was an easy way to die … then just later my helmet started to work and things went better. … Never mind many rats and mice here in the trenches have been slain or rendered inactive bless the Bosch for that! … Yes, it is a great life I really thought my end had come this morning a curious feeling Heaps of love to all.26

On 24 August 1916, in the neighbourhood of Delville Wood on the Somme, Ken suffered wounds that ultimately proved mortal. After spending a day on the parapet of the trench, observing for his battery, he was hit in the neck by a fragment of shell and paralyzed. He returned to England to convalesce, the once great athlete obliged to spend a year lying on his back, initially in the Empire Hospital in Vincent Square, Westminster and latterly in the Hospital for Convalescents (Templeton House) at Roehampton.

Ken died on 22 August 1917, age 25. For his military service he received the MC and, from the French authorities, the Croix de Guerre, the former presented to him in hospital by H M the King. He is buried in Putney Vale Cemetery. His grave is not marked by a Commonwealth War Grave headstone, the family seemingly preferring a private marker.

A.2 The grave of Kenneth Gordon Garnett27

26

19 Dec 1915 27 Author’s photo

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

The poet Edward Thomas (SPS 1894 1895, Chapter 8 pp 41 44), famously vacillated for months as to whether to volunteer, torn between the options of either following his friend, Robert Frost, across the Atlantic or crossing the Channel and descending into the trenches. ‘Frankly I do not want to go [to the trenches]’, he confessed, ‘but hardly a day passes without my thinking I should. With no call [conscription had yet to be introduced] the problem is endless’.28 The ‘problem’ was brought to an end when Robert published his poem Two Roads, soon to be rechristened The Road Not Taken. The last verse read:

I shall be telling this with a sigh Somewhere ages and ages hence: Two roads diverged in a wood, and I

I took the one less travelled by, And that has made all the difference.

Edward chose to interpret this as a commentary on his lack of direction, a character trait that he told himself amounted to cowardice. It pricked him into enlisting on 19 July 1915 in 1/28th Bn. London Regiment (Artists Rifles). Yet even now Edward could not explain why he had volunteered. ‘Several people have asked me [why]’, he informed his wife, Eleanor, ‘but I could not answer yet.’29 Shortly afterwards he pronounced in a poem called Roads:

Now all roads lead to France And heavy is the tread Of the living; but the dead Returning lightly dance.

Edward was killed in action, age 39. He is buried in Agny Military Cemetery.

A.3 Rev Albert Ernest Hillard, High Master 1905 192730

28

Quoted in Hollis, Matthew Now All Roads Lead to France, The Last Years of Edward Thomas (Faber and Faber, 2011) p 233

29 Quoted in Hollis, Matthew Now All Roads Lead to France, The Last Years of Edward Thomas (Faber and Faber, 2011) p 240

30 St Paul’s School Archive. Image painted by Kennington, Eric (SPS 1904 1908; see Chapter 11, Section 11.4)

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

In a special assembly on 28 September 1914 the High Master offered an explanation for the high rate of volunteerism. He said:

I find scores upon scores of those who recently were our companions here laying aside their careers for the time and risking all, offering their lives for this purpose they have in mind. What are they doing it for? … I answer that they understand the difference between what is worthy and what is mean; that they can distinguish between justice and oppression; that liberty has not become a cant word to them; that they understand what duty to friends is, and that they feel with a sensitiveness which many of the great intellectuals cannot emulate when a choice is presented that involves more than gain or loss, to be calculated in material terms. That is why so many tens of thousands of our public school boys have offered

themselves. … [Reflect upon] the thrill of thanksgiving you must feel that those you lose give their lives in the noblest cause ever championed by a people 31

That so many Paulines developed a ‘sensitiveness’ to which the High Master alluded was because of the school’s rigorous adherence to a well established three course diet of Chapel, a study of the Classics and participation in competitive athleticism. By these means a public school education instilled a spirit of patriotic duty infused with a responsibility to lead when required and to care for those who were duly led. It also fomented a symbiotic relationship between such schools and the armed forces. A presentation to new officers in 1914 by a senior commanding officer assumed a tone not dissimilar to Hillard’s assemblies. The new officers were told: ‘You are responsible for maintaining the honour of England, for doing all you can to ensure the security of England, and of our women and our children after us’.32 This was akin to what the High Master referred to as the ‘sacredness of our cause’.33

Nearly 3,000 OPs took roads that ‘led to France’, some more direct than others. For these OPs, the prevailing national mood of patriotic endeavour, combined with their experiences at St Paul’s, meant that to volunteer to serve in the war amounted to more than a moral obligation; it was a sacred imperative. Ken Garnett had spoken for many when he had said, ‘Of course we must go’

In public schools up and down the land, a spiritual movement known as Muscular Christianity had been gaining momentum since the middle of the nineteenth century. The tenets of this movement were characterized by discipline, duty, self sacrifice, masculinity, celebration of the moral and physical beauty of athleticism and, perhaps above all, by an imperative to act as Christ’s soldiers on Earth.34

31

The Pauline, 32 212 213 Oct 1914 pp 185 190. (See Appendix 5 for the complete text of Hillard’s Address.)

32 The Duties of an Officer: Knowledge and Character. Delivered by a Senior Officer to a School for young Officers in France, republished in The Times.

Fairbank Papers MS Add.10082 MS Add.10082/9 p 69+

33 High Master Address to the school on 28 September 1914. The Pauline, 32 212 213 October 1914 pp 185 190

34 Edward Thring, the Headmaster of Uppingham School between 1853 and 1887, defined Muscular Christianity thus: ‘The learning to be responsible and independent, to bear pain, to drop rank and wealth and luxury is a priceless boon … With all their faults the public schools are the cause of this manliness.’ Parkin G R, Life, Diary and Letters of Edward Thring, Vol II p 196

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

Alfred Waterhouse’s design for the new St Paul’s School, opened in 1884, rather curiously did not include a chapel amongst its buildings, perhaps bringing into question the extent to which ‘Christian Muscularity’ was inculcated at St Paul’s. 35 Nevertheless, formal prayer occurred each morning in the school, Sunday services were held in the Great Hall at intervals throughout the term and the Bishop of London instituted a special annual confirmation service for Pauline’s at St Paul’s Cathedral. It is impossible to quantify the number of OPs who considered themselves Christ’s soldiers, but it seems likely that this figure was substantial. Kenneth Gordon Garnett was certainly one such. Upon learning of Ken’s death, an acquaintance wrote to his mother to inform her that ‘I for one shall always thank God for such Christian Knighthood as was typified in Ken’.36 Others advertised their affinity with the tenets of Christian Muscularity and Christian Knighthood via the epitaphs on their gravestones. For instance:

Dick, 2nd Lt George Frederick Graeme (SPS 1906 1908) and Johnson, 2nd Lt Harold George (SPS 1912 1915) each lie under gravestones inscribed with the epitaph: I Have Fought A Good Fight I Have Finished My Course I Have Kept The Faith Long Innes, Lt Selwyn (SPS 1891 1894): My Son He Is God’s Soldier Let Him Be I Would Not Wish Him To A Fairer Death R. I. P Pridham, Gunner Hugh Trevor (SPS 1912 1917): His Watchword Was Endure Hardness As A Good Soldier of Jesus Christ Penderel Brodhurst, Bernard Richard (SPS 1906 1908): His Body To Fair France His Pure Soul Unto His Captain Christ Webb Carter, Desmond Patrick (SPS 1911 1914): God’s Brave Young Knight

35 This was rectified with the creation of the Memorial Chapel from a redundant classroom in 1926.

36 Herbert George, a YMCA worker in France. SPS Archive Box 296 Kenneth Gordon Garnett Biography (London, 1918) p 39

37 St Paul’s Archive, Digby La Motte Collection. (Patrick’s brother, Brian Wolsely, also attended SPS (1914 1919). Brian was too young to serve in the 1st World War but he became a career soldier, rising to the rank of Brigadier. He was awarded the DSO and OBE.)

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

The obituaries of OPs published in The Pauline frequently evoke sentiments informed by Muscular Christianity. Ian Osborne Crombie (SPS 1909 1913, see Chapter 8, Section 8.5) was killed in action on the Somme on 30 July 1916, age 21. He is buried in Bouzincourt Communal Cemetery. The epitaph on his grave asserts: As Dying And Behold We Live St Paul. Ian’s obituary reads:

In word, thought, and deed he stood for that which has made the one time English Public schoolboy the noblest type of manhood. He was of those who, knowing the responsibilities of office, neither seek it nor shirk it, yet one to whom great responsibility naturally came. … Crombie had the greatest of ambitions to be of service to his fellow men. There was nothing blind about his enthusiasm; he knew its price: yet there was such gladness in his soul when last he left for the front as was never there during all his years of boyhood. He had earned his place in the great kingdom.38

In addition to exposure to the tenets of Muscular Christianity, Paulines undertook a study of the Classics, perhaps informed by J W Mackail’s highly popular Greek Anthology, first published in 1890. Boys read Greek and Roman authors whose work worshipped the male athlete, portrayed war as a natural part of a leader’s duty and articulated a belief that a military death was understood to be swift, clean and brave. It was a sentiment that accompanied them to the trenches. Edmund John Soloman (SPS, 1906 1912) was killed on 2 June 1917. A contributor to his obituary in The Pauline remarked that:

I have as a memorial of him, returned to me from the trenches, two battered volumes of Monro’s Iliad, which he and a fellow Oxonian had, as he told me in his last leave, read again

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

with all the old enthusiasm as they worked out together an essay on the Homeric view of death. Only a few days after that leave “the end of death” came to him.39

A study of the Classics encouraged a belief that war was ennobled, and that participation in it amounted to a rite of passage. If death occurred it took a form in which it had lost its sting and instead had become a wondrous thing so much so that it was perhaps, in certain circumstances, to be positively courted. It was no accident that the St Paul’s South African War Memorial, erected in 1906, assumed a classical form, boasting a Latin inscription and a list of names of the fallen. (See Chapter 12, Section 12.1, i.) Standing prominently at the front of the school, it was at once a shrine to noble death and an advert for immortality classically wrought.

Arthur Gerald Ritchie attended SPS from 1893 to 1897. He was the winner of the John Watson and Landscape prizes three years in succession, along with the Shepard Cup in 1897, awarded to the winner of the greatest number of athletic events in the annual sports day. He also played for the 1st XV. After leaving SPS Arthur became a career soldier, serving in the first instance with the 1st Bn. Cameronians (Scottish Rifles), in which unit he rose to the rank of Captain. He rejoined this unit in October 1914, two weeks shy of his thirty fifth birthday. Arthur was mortally wounded by a sniper on the night of 29 30 October and died at Boulogne on 22 November. He lies in Boulogne Eastern Cemetery.

A.1.4 Front cover of the Army Gazette, composed by Arthur, December 1896. His name is inscribed in the bottom right hand corner. The letter ‘P’ and the prawn on the shield are 39 The Pauline, 35 234 Nov 1917 pp 144 145 40 © IWM HU 124974

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

humorous heraldic devices referencing Charles S Pendelbury (SPS 1877 1910), the master in charge of the Army Form. 41

A brilliant wit and artist, Arthur had made good use of these attributes in the production of an issue of the SPS Army Form Gazette in December 1896. In 1926 Maurice McClean Bidder (SPS 1892 1896), who appears to have been in the same Army Form as Arthur, sent a copy of the Gazette to the school accompanied with a letter in which he observed that ‘Ritchie of course was killed in France in 1914, an end which he had always hoped would be his’.42

41 St Paul’s Archive

42 St Paul’s School Archive. Bidder, Maurice McClean (SPS 1892 1897); Letter to The Secretary, SPS, 25 Feb 1926. St Paul’s School Army Form Gazette

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

Arthur was by no means the only OP who desired such an end. Cyril Steele Perkins (SPS 1899 1902) was among the very first OPs to fall. A career soldier from a family who had served with distinction in each branch of the armed forces over several generations, he was severely wounded by a shell on 26 August 1914. It was reported that ‘he died one of the grandest deaths a British officer could wish for. He was lifted out of the trenches wounded four times, but, protesting, he crawled back again and remained there till he was mortally wounded.’43

The work of author Ernest Raymond (SPS 1901 1904, see Chapter 11, Section 11.5), frequently referencing patriotic, noble death is evidently informed by the academic diet he ingested while at St Paul’s and further refined by his experiences at the front. Indeed, the very title of Ernest’s great wartime novel, Tell England: a Study in a Generation (1922), is of Classical derivation, an abbreviation of the epitaph he composed for the dead of the public schools:

Tell England, ye who pass this monument We died for her, and here we rest content.45

These lines are a direct crib of Simonides’ epitaph upon the Spartan dead at Thermopylae: ‘O Stranger, tell the Lacedaemonians that we lie here obeying orders’.

In August 1914 Ernest was twenty five. Recently ordained, he immediately applied to the Chaplain General for service overseas with the army and duly served as Chaplain to

43 The Bond of Sacrifice, Vol 1. 44 © IWM HU 118514

45 Raymond, Ernest Tell England: a Study in a Generation (1922)

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

the 1/10th Bn. Manchester Regiment and to the 9th (Service) Bn. Worcestershire Regiment. He survived the war, becoming one of England’s most popular authors.

Tell England narrates the stories of three boys Rupert Ray, Edgar Doe and Archibald Pennybet as they make their way through their public school, ‘Kensingstowe’ (a thinly disguised St Paul’s), and thereafter follows them to the beaches of Gallipoli. In one instance Rupert reflects upon the prospects of achieving a noble death, a sacrifice made in patriotic circumstance:

I see a death in No Man’s Land to morrow as a wonderful thing. There you stand exactly between two nations. All Britain with her might is behind your back, reaching down to her frontier, which is the trench whence you have just leapt. All Germany with her might is before your face. Perhaps it is not ill to die standing like that in front of your nation.46

In another instance, Edgar Doe remarks to Rupert:

If I’d never known the shock of seeing sudden death at my side, I’d have missed a terribly wonderful thing. … Tiens, if I’m knocked out, it’s at least the most wonderful death. It’s the deepest death.47

Later in the book, when Edgar is killed, Rupert experiences the following exchange with an army chaplain, Monty:

“Rupert”, [said Monty], “Edgar is dead.... And there’s only one unbeautiful thing about his death, and that is the way his friend [i.e. Rupert] is taking it”. … “There’s no beauty in death and burial and corruption,” I said. “Yes, there is, even in them. There’s beauty in thinking that the same material which goes to make these earthly hills and that still water should have been shaped into a graceful body, and lit with the divine spark which was Edgar Doe. There’s beauty in thinking that, when the unconquerable spark has escaped away, the material is returned to the earth, where it urges its life, also an unconquerable thing, into grass and flowers. It’s harmonious it’s beautiful.”48

Denis Oliver Barnet (known as ‘Dobbin’) (SPS 1907 1914, see Volume 2) was eighteen when war broke out. An accomplished athlete and brilliant prize winning Classicist, Dobbin eschewed his place at Oxford and immediately enlisted in 28th Bn. London Regiment (Artists Rifles). The apparent circumstances of his death on 15 – 16 August 1915 as described at the

46

Raymond, Ernest Tell England: a Study in a Generation (1922)

47 Raymond, Ernest Tell England: a Study in a Generation (1922)

48

Raymond, Ernest Tell England: a Study in a Generation (1922)

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

time evoke sentiments of mortality as portrayed in Homer’s Iliad a warrior winning glory by implacably facing death while simultaneously finding the spirit to fight courageously. One account of Dobbin’s death described how:

[On the night he was killed] Barnett had to start a working party at a place where our trench touched the German trench, with only twenty yards of unoccupied trench in between. He was warned to be careful, as the Germans had a machine gun and several rifles trained on the spot, but with his usual courage he got up on the parapet, and from there directed the working party. A flame showed him up and he was fired at immediately, and one bullet hit him in the body. . . . His men mourned his loss deeply, for they all, like ourselves, loved him.49

Another report evoked a noble death:

I was with [Dobbin] just before he died at the dressing station, and his uncomplaining courage was an object lesson as to the way a brave man should face his end. He was quite conscious all the time. His face looked beautiful in its calmness, as if chiselled in white marble. I only hope I shall meet my end when it comes with half his nobility.50

Games existed at St Paul’s long before the outbreak of war in 1914: cricket was played from some point during the first half of the nineteenth century; Rugby Football was introduced to the school in 1867; the Rowing Club appears to have been founded by the mathematical master, Charles S Pendlebury (SPS 1877 1910) in 1881 (though some evidence suggests it may be earlier); a gymnasium and covered fives courts were established on the school site in 1890 and a swimming pool was built in 1900. Lacrosse and hockey were played for a while. Regular competition was undertaken against other schools and in internal competitions. The greatest of all Pauline athletic successes was in boxing, St Paul’s frequently winning in a number of weight categories in the annual Public Schools’ Boxing Competition at Aldershot.

School athletics at St Paul’s much benefitted from the establishment in 1896 of compulsory games on one afternoon a week. In 1899 the school was divided into six permanent clubs (or ‘houses’) which competed against each other in the various athletic disciplines. Following the opening of the new playing fields in October 1908, the school was divided into a senior and a junior division, and on each of the two weekly athletic afternoons one of the divisions was out of school.

49

The Pauline, 33 220 Oct 1915 pp 178 179

50 The Pauline, 33 220 Oct 1915 pp 178 179

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

It was generally recognised that the playing of games conferred the benefits of personal pleasure and bodily exercise; but it was also understood that frequent and well organised games and associated competition were important to establishing and maintaining an esprit de corps that bred sentiments of mutual loyalty, selfless commitment and, for those who captained a team, instilled a culture of command. As Field Marshall Douglas Haig put it, team games required ‘decision and character on the part of the leaders, discipline and unselfishness among the led, and initiative and self sacrifice on the part of all’.51 These attitudes are referenced in Henry Newbolt’s famous poem written in 1892, Vitai Lampada (a quotation from Lucretius, meaning ‘the torch of life’), and likely well known to all Paulines who stepped onto a pitch and latterly paraded in khaki:

The Gatling’s jammed and the Colonel dead, And the regiment blind with dust and smoke. The river of death has brimmed his banks, And England’s far, and Honour a name, But the voice of a schoolboy rallies the ranks: “Play up! play up! and play the game!”

A.4 Rugby Football match taking place on St Paul’s School playing fields. (Denis Oliver Barnett is on the right of the picture wearing a striped shirt, to the left of the coated figure.)52

51 Haig, Douglas, A Rectorial Address Delivered to the Students in the University of St Andrews, 14 May 1919, St Andrews, 1919

52 St Paul’s School Archive

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

The poet Robert Vernede (SPS 1889 1894, see Chapter 8, Section 8.4) was 39 when war broke out and knew his Newbolt. Despite the fact that he was four years beyond the age for volunteering, he did not hesitate to enlist. Robert’s motivation can be gleaned from his poem, The Call, published in The Times on 19 August 1914. It includes the following verse, elevating war as the ‘game of games’:

Lad, with the merry smile and the eyes Quick as a hawk’s and clear as the day, You, who have counted the game the prize, Here is the game of games to play. Never a goal the captains say Matches the one that’s needed now: Put the old blazer and cap away England’s colours await your brow.

Team games bred loyalty: internal House games imbrued fidelity to the House; fixtures against other schools birthed an intense loyalty to the school and its ideals. In the poem K.L.H Died of Wounds Received at the Dardanelles by Paul Bewsher (SPS 1907 1912, see Chapter 11, Section 11.5) K L H likely Kenneth Aislabie Longuet Higgens (SPS 1908 1913) is pictured contemplating the honours boards at his school:

He read the names: and wondered if his own Would ever grace the walls in letters bold. He knew not that he for the School would gain A greater honour with a greater price

The intensity of allegiance to the school and the impulse to uphold its honour by fighting for crown and country thus trumped all, even life itself. As Robert Vernede (SPS 1889 1894, see Chapter 8, Section 8.4) put it: ‘England, for thee to die’.53

1.4

John (known as Jack) Sherwin Engall (SPS 1912 1914) had left St Paul’s before the outbreak of hostilities. He did not thus witness the growing influence of the OTC during the war; nor did he experience the collective ‘sacredness of our cause’ sentiment that settled on the school like a miasma from August 1914. The letter he wrote to his parents the day before his death in 1916 thus provides compelling insights into the motivations of an OP volunteer of the pre war cohort.

53 Vernede, R ‘A Petition’, War Poems and other verses p 61

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

At the time hostilities broke out Jack had recently passed the Preliminary Examination of the Institute of Chartered Accountants. Age eighteen, Jack’s world lay before him, but, like numerous other OPs, no more than six weeks after the outbreak of the war, he chose to suspend his career and enlisted with 1/16th Bn. London Regiment (Queen’s Westminster Rifles), with whom he undertook training. After completing his training Jack gained his commission (rather unusually in the same unit) and crossed to France on 31 December 1915, one of the 511 OPs destined not to return.

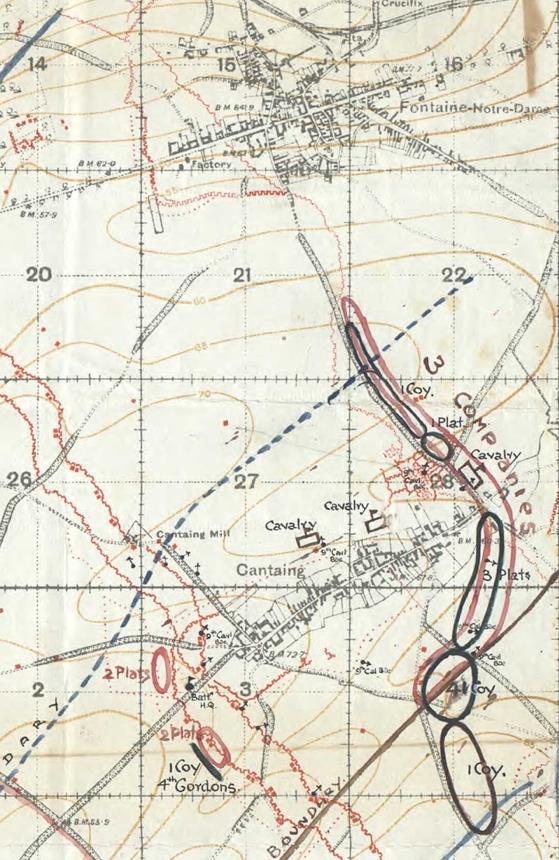

In the early morning of 1 July 1916 2nd Lieutenant Engall, Queen’s Westminster Rifles, attached 169th Machine Gun Company, was making his way up the trenches before Gommecourt, about to play his part in a diversionary assault designed to protect the northern flank of a massive attack directly to the south, later to become known as the Battle of the Somme. Detailed to assist his mother unit in their objective of capturing of the ‘Quadrilateral’ (shown on the map as Quad’l), an excited and apprehensive Jack informed his parents that:

I’m sure you will be pleased to hear that I’m going over with [A Company] the Westminsters. The old regiment has been given the most ticklish task in the whole of the [56th] Division; and I’m very proud of my section, because it is the only section in the whole of the Machine Gun Company that is going over the top; and my two particular guns have been given the two most advanced, and therefore most important, positions of all an honour that is coveted by many. So you can see that I have cause to be proud, inasmuch as at the moment that counts I am the officer who is entrusted with the most difficult task.54

A.5 Trench map showing the section of German trenches attacked by 1/16th Bn. London Regiment (‘QWR’) on 1 July 1916. (The British trenches lie to the south, out of image.)55 54 Housman L (ed), War Letters of Fallen Englishmen (1930), p 115 55 TNA WO 95 2957 1 6

1. ‘All Roads Lead to France’: part one

Fierce German resistance, most especially in the form of a day long barrage, combined with a shortage of ammunition on the British side, meant that Jack fell at the second line of German defences. A report described how:

The Vickers Gun which accompanied A Coy [i.e. Company] got as far as the junction of Etch Feed and Feint [trenches] and was there brought into action by 2nd Lieut J S Engall, who had only one of his team left with him he fought the gun himself [until] he was killed at this spot.

56

The 169th Brigade diary recorded that on 1 July:

56 TNA WO 95 2963 2 Report on 1/16th Bn. London Regiment Attack on Gommecourt, 1 July 1916

[At first] all battalions did extraordinarily well, but at the end of the day we held our trenches only. Estimated casualties, 2,000.57

Jack was recommended for a gallantry award but this was never made, most likely because no other officer survived to offer verification of the action. Jack’s body was lost in the fighting, churned and captured by the infamous Somme mud. He lies there still and is one of the 72,333 officers and men commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial. Jack was two weeks short of his 20th birthday.

Elsewhere in the letter penned on 30 June, Jack explained to his parents that: