ATRIUM

Paradise Lost

Milton’s Epic is Central to Christianity

In Conversation Mark Rosenblatt and Theo Hobson discuss Giant

Last Word Sam Freedman is Set Right

ST PAUL’S ALUMNI MAGAZINE

Editorial

Atrium has received a letter from two Old Paulines who suggest that it had moved too far away from being a traditional alumni magazine. The letter from Bob Porter (1963-67) and Merrick Willis (1961-66) is published in full on page 5. It asks for more about OP events and what old boys are doing.

Our vision for Atrium is different. It is to publish a magazine that displays the talents and interests of Paulines and not just reports on what alumni are doing or have done (as in the obituaries section). In summary, Paulines writing about interesting things and not only us writing about interesting Paulines.

We have Bernard Levin (sadly not an OP) as our guide. When one of our Editorial Board members, Jonathan Foreman (1979-83), edited the pupils’ newspaper Folio in his final year at School, he wrote to Bernard Levin asking for his views on school magazines. The great columnist wrote back, “I have always thought that school magazines should not concern themselves too much with school itself: that is the job of the graffiti writer. A school magazine should aim to be as close to a ‘real’ magazine as possible and to encourage good writing on a wide variety of subjects.”

We thank Bob and Merrick for their letter and respect their view but continue to believe that Levin’s advice holds good. The Old Pauline News section is, however, weightier than in the recent past with 15 events highlighted, reflecting improving engagement levels across OPs.

For a few weeks after Atrium is published, our inbox bulges with OPs asking to be put in touch with each

other. Two of these introductions are featured later in the magazine. Derek Coleman (1942-48) is now in touch with Michael Simmons (1946-52) sharing their love of jazz and disagreeing over bepop. Both are in their 90s. After reading Jonathan Foreman’s article on Edward Behr (1940-44), Robert Silman (1953-58) has been in touch about when he met Edward and about Ian Young’s (1954-58) book The Private Life of Islam: An Algerian Diary which we highlight in Pauline Books. Edward reviewed it in Newsweek in 1974, praising the book for being ‘the most important book to have been written about Algeria since Independence’ and saying that it should be compulsory reading for every member of the Algerian government.

This magazine’s articles include Richard Davenport-Hines (1967-71) on being gay at School, current Pauline Theo Frankel’s prize-winning essay on Laurence Binyon (1881-88), a Pauline playwright, magicians and ventriloquists and Theo Hobson (1985-90) reviews the latest book about John Milton. The School’s copies of Paradise Lost, that were once owned by Burns and Napoleon, feature on our cover.

Jeremy Withers Green (1975-80) OPC President

The Editorial board thanks all contributors, information providers and proof readers and particularly Hilary Cummings, Kaylee Meerton and Kelly Strickland.

Atrium’s Editorial Board: Omar Burhanuddin, Jonathan Foreman, David Herman, Theo Hobson, Neil Wates and Jeremy Withers Green.

Cover

photo: John Milton’s works from the Rare Book Room photographed by Tom Bradley

Design: haime-butler.com

Print: Lavenham Press

Richard

Theo

David

Jeremy

When

Hilary

Lorie

Neil

Sam

Simon

Hilary Cummings arrived at St Paul’s as the Librarian in 2018. Hilary gained her degree in Management Science from UMIST then worked in transport management before returning to university to retrain as a Librarian. She worked in university libraries for many years before a family relocation to Shanghai brought a move into children’s librarianship. She has worked in school libraries since her family’s return to London in 2014.

Kaylee Meerton joined St Paul’s as the Marketing and Communications Manager in 2023, taking on the role of managing the School’s internal and external communications, as well as leading the marketing of the Old Pauline Club. Originally hailing from Australia, Kaylee relocated to London in 2022 with a short contract at King’s College London before joining St Paul’s. Prior to that, she graduated from Curtin University with a degree in Journalism and International Relations, picking up work experience in China and the United States. Her career started in Australian regional journalism, with roles as an editor and reporter for Fairfax Media, Australian Community Media and Student Edge.

Theo Frankel is a current pupil at St Paul’s School, studying English, Philosophy, and Drama for A Levels and will be going to Oxford to read English Literature. Theo is currently rehearsing for the Spring Term senior play, Hangmen, and made a garment inspired by sustainable practices for his Extended Project Qualification.

Michael Simmons (1946-52) read Classics and Law at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. He qualified as a solicitor and, after serving for two years as an officer in the RAF, practised Law in the City and Central London for 50 years. Since retiring, he has pursued a new career as a writer. Michael is in touch with a sadly diminishing number of members of the Upper VIII of 1952.

David Abulafia CBE (1963-67) is Emeritus Professor of Mediterranean History at the University of Cambridge, a Fellow of Gonville and Caius College, and a former Chairman of the Cambridge History Faculty. His books include Frederick II, The Discovery of Mankind, The Great Sea and The Boundless Sea which was the winner of the Wolfson History prize in 2020. He is a Fellow of the British Academy, a Member of the Academia Europaea, a Commendatore of the Italian Republic and Visiting Professor at the College of Europe and at the University of Gibraltar. He has been the Apposer at Apposition and is a Vice President of the OPC.

Richard Davenport-Hines (1967-71) is a Quondam Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, a former trustee of the Royal Literary Fund and of the London Library, and a former member of the staff of the London School of Economics. His first book was awarded the Wolfson History prize in 1985. He has written biographies of W. H. Auden, Marcel Proust, John Maynard Keynes, and King Edward VII, historical studies of the Security Service, sexually transmitted diseases, drugs trafficking, the Profumo Affair, and the sinking of the Titanic

David Herman (1973-75) studied History and English at Cambridge and English and American Literature at Columbia University. He produced arts, history and talk programmes for BBC2, Radio 4 and Channel 4 (when it was good) for nearly 20 years and since then, has written about literature, and Jewish culture and history.

Jeremy Withers Green (1975-80) read History at Magdalene College, Cambridge before starting work in finance. After 27 years in the city, he left J.P. Morgan Cazenove and began working as a volunteer and trustee in the charitable sector at The Haller Foundation, The 999 Club and Friends of the Elderly. In 2016 he joined the OPC Executive Committee and has worked as Communications and Engagement Director and Editor of Atrium and remains a member of the Editorial Board. In June 2023 he started his two years as Club President.

Theo Hobson (1985-90) studied English Literature at York University, then Theology at Cambridge. He has written some books about religion including God Created Humanism: the Christian Basis of Secular Values and much journalism, including for the Spectator. He is currently a part-time teacher, part-time writer, and part-time artist.

Zahaan Bharmal (1990-95) read Physics at the University of Oxford and won a Fulbright Scholarship to Stanford University where he earned an MBA. He spent his early career as a policy adviser and speechwriter for the British Government and the World Bank and is currently a senior director with Google. Zahaan has recently published his debut book, The Art of Physics. He also writes about space for The Guardian and has won NASA’s Exceptional Public Achievement Medal for services to science communication. He lives in Yorkshire with his wife and two young sons.

James Grant (1990-95) sits on the Old Pauline Club’s Executive Committee as Sports Director, as well as holding the posts of Chairman of the Old Pauline Cricket Club and Honorary Secretary of the Old Pauline Golfing Society. After a career in event organising and charity fundraising, he now works at St Paul’s School as Associate Director, Alumni Relations and still feels nervous entering the staff room.

Lorie Church (1992-97): when he is away from the workplace, Lorie encourages people to put letters in little squares. He has had puzzles published in various titles internationally. As well as contributing to the Listener series, Mind Sports Olympiad and Times daily, he sets Atrium’s crossword.

Edward Evans (1993-98) received his BA in Ancient and Modern History and MPhil in Oriental Studies from the University of Oxford. He then received his Ph.D. in English Literature from Bar-Ilan University. He currently teaches literature at the Tel Aviv School of Arts and had Shakespeare’s Mirrors published in September 2024 by Routledge.

Sam Freedman (1994-98) is a senior fellow at the Institute for Government and a senior adviser to Ark Schools. He has spent his career working in different policy-focused roles around Westminster, including as an adviser to the leader of the opposition and three years at the Department for Education as a senior policy adviser. He writes about policy and politics for numerous outlets including the Financial Times, Sunday Times, Guardian and New Statesman. With his father, Lawrence Freedman, he runs ‘Comment is Freed’, Britain’s most popular politics substack. He also has a following of over 140,000 on Twitter.

Neil Wates (1999-2004) worked in the property sector for 15 years before training as a Psychodynamic Therapist and Counsellor. He is a trustee of a UK based charitable trust and an NGO committed to the alleviation of social violence in East Africa. He also founded Friendship Adventure; a craft brewery based in Brixton. Neil is on the OPC Executive Committee.

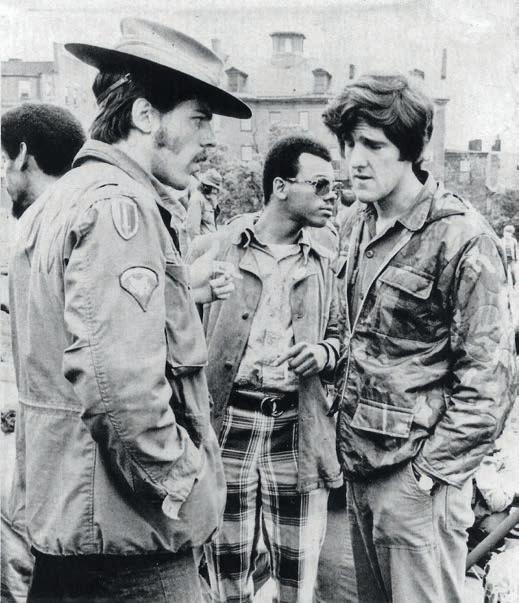

A confident Pauline ventriloquist

Letters

Dear Atrium,

I look back at my days at St Paul’s with much appreciation. Getting up at 6am to commute an hour on the number 33 bus and then returning home at 6.30pm only to start two hours of homework was the norm.

Some unique memories include listening to a couple of boys discussing the 100 ways they could tie their neckties – apparently there are over 177,000. Getting a detention from Mr Smith (Classics Department 1962-98) for rolling up my sleeves and for picking a leaf off a tree. Being so terrified of my Latin teacher that my textbook had thumb holes through the pages where I had sweated through them with fear. To this day he remains the scariest human being I have ever encountered. I once returned to St Paul’s in my 20s and found myself cowering away from him as he passed me in the corridor. Yet during the next lesson we threw paper balls at the music teacher. What makes one teacher terrifying and one not?

My “journey” did not take a typical Pauline route. One day in the Walker Library I discovered a book called 100,000 jobs in the USA. Little did I know that it would lead me to taking a gap year in the States. There I would see a man perform with a puppet, which ultimately would result in me becoming a ventriloquist. Little did I know that my job would one day entail public speaking to thousands. I discovered there is a mathematical formula to dream achievement. Apparently, it is proportional to the size of one’s dreams, the desire to achieve them and one’s ability to overcome disappointment. Can we get up one more time and push through all those disappointments? As Paulines, we learn we can.

Perhaps my biggest takeaway from my time at St Paul’s is a sense of confidence. Of never being overawed by anyone but rather being able to communicate and relate to anyone, whether that be in a high-end cocktail party on a cruise ship or to the hurting and homeless who need an encouraging word.

Thank you to my father and mother who gave up their holidays so they could give me one of the best educations possible. Thank you to St Paul’s for the confidence that you helped install in me.

With much appreciation, Marc Griffiths (1984-89) (Marc’s book ‘Get Happy’ is included in Pauline Books)

“...who have no memorial” Dear Atrium,

What a wonderful “Last Word” from Malcolm Sturgess (1947-52) in Autumn/Winter 2024’s Atrium. Despite our being of different vintages (I was mid 1960s), I identified wholeheartedly with Malcolm’s observations about Pauline “also-rans”.

I remember that, at my parents’ interview with the then High Master, Tom Howarth (High Master 1962-73), he made it clear that St Paul’s was an “elitist institution” (reminiscent of the scene in the film if...., when the headmaster says to his senior masters that he makes no apology for being “elitist”), and this ethos followed me throughout my time at School.

I was competent academically. I even came “top of the class” once, which occasioned a trip to the High Master to be personally congratulated. My standards must have slipped, because, in a subsequent High Master’s Report, he wrote “5% more effort, and this would be a really good report”; this has haunted me for the rest of my life.

As A Levels approached, I decided that I did not want to follow the expected path to Oxbridge (or Redbrick, if you must...), but would train to be a journalist. I remember the look of disapproval on Tom’s face as I told him this at my Valete interview; it was akin to an Army “interview without coffee”!

Years later, when I found myself in the lower reaches of the Civil Service, I wanted to be at the “coal face”, as I saw it, rather than devising Policy, I was brought up short when a colleague, on learning that I was not the expected “Fast Streamer”, remarked, “Ah, one of those Pauline failures”! I was no longer part of the elite.

By and large, and despite not conforming to the Pauline ideal, I was very happy at St Paul’s, and had a varied career. I have fond memories of my friends at the school (several of whom, inevitably, have now “gone beyond”) and remember some of the staff who were also contemporaneous with Malcolm “Willie” Gawne (Master 1947-77), a lovely man, who would take members of the Selborne Society on jaunts (“field-trips”) into the countryside, and was always very apologetic if he had to beat a boy.

Happy Days, Mike Ricketts (1963-68)

On reading Jonathan Foreman’s (1979-83) excellent article on Ed Behr (1940-44), I am reminded of Ed’s encounter with another Old Pauline in the 1970s.

Ian Young (1954-58), a pupil of Philip Whitting (History Department 1929-63) in the late 1950s, had gone on a medical elective to Tizi Ouzou in Algeria and turned his experience into a fascinating book on the emergence of Islamic fundamentalism within socialist Algeria. The book was titled The Private Life of Islam published by Pimlico Press, and without Ed knowing anything about Ian, he wrote a full-page review in Newsweek praising the book for being the most important book to have been written about Algeria since Independence and that it should be compulsory reading for every member of the Algerian government.

Ian wrote to Ed at Newsweek to thank him for the review, and Ed replied by saying he had to speak with Ian urgently and in private. At their meeting, Ed told how he had been invited to Algiers to interview the Foreign Minister before he had written his review. On arrival at Algiers airport, Ed had been arrested by the security services and the question they repeatedly asked him was who the author of the book was that he had reviewed.

Ed was detained, refused entry even though invited by the Foreign Minister, and expelled. His urgent message to Ian was to warn that he must not set foot in Algeria because if he did, he would never get out alive. Ian heeded Ed’s advice, and they subsequently became the best of friends.

With very best wishes, Robert Silman (1953-58)

Warts and all Dear Atrium,

I was delighted to see the “warts and all” approach in the Autumn/Winter 2024 magazine – the gratuitous unpleasantness revealed in Nick Birbeck’s “not all happy days” letter about his time at Colet Court and, in particular, the article about Josh Hawley, the former temporary staff member who so distinguished himself in the US Senate on 6 January 2021.

Perhaps, in the light of the commemoration of that notorious figure, it might be time to add reminiscences of another former staff member, who died recently. Richard Williamson (English department 1965-70) was the Holocaust denying former bishop of “l’église de Dreyfus était coupable” (AKA the Society of St. Pius X), who in the mid-1960s was able to unite an otherwise disputatious class against him, memorably in his description of one of the favourite comedies of the time, Peter Cook and Dudley Moore’s Not Only But Also as “evil”.

With best wishes, Peter Davis (1962-66)

Ed Behr and Ian Young Dear Atrium,

The PT Squad – a preparation for adult life Dear Atrium,

David Herman’s (1973-75) excellent Pauline Profile of Jonathan Miller (1947-53) omitted one rarely mentioned feature of school life in the postwar years. Jonathan was a proud member of the PT Squad, a gaggle of rebels and misfits who avoided joining the cadet force or the Scouts by spending two hours in the gymnasium every Monday afternoon under the supervision of the luckless Mr Williams. Miller was not the only joker that the teacher had to deal with. I recall one Eighth Year hiding in the hated vaulting box and only emerging twenty minutes into the session. In later reminiscences Jonathan spoke of the ‘Jewish PT Group’ but it was open to boys of all beliefs and none (especially none). The School’s hierarchy ignored its existence except for the Annual Parade, where we had to lurk in the basements, primed to emerge and discreetly to remove any cadet who fainted.

I served five years in the group and when I was leaving St Paul’s in 1957, I went to bid farewell to Mr Williams. He stared at me and grunted ‘Well, you were one of the more co-operative ones’. He had occasionally put me in charge of some younger boys and I soon discovered that I could instruct them to perform exercises which were beyond me completely. Perhaps that is why I went on to spend half a century as a schoolteacher and lecturer. The PT Squad – a preparation for adult life.

Jonathan was five years my senior so I did not know him personally. When he was producing at the Mermaid I cheekily wrote to ask if my A Level English group could sit in on a rehearsal. His Shakespeare play was due to open one day after the public exam. He did not reply. I guess I should not have mentioned the PT Squad.

Regards, Morgan Phillips (1952-57)

PS. There were two members of staff called Williams – the one who took the PT Squad and a full-time gymnastics instructor. Because of their height they were known respectively as Little Willy and Big Willy. Oh well, we were schoolboys!

Dear Sirs,

Atrium feedback

We wanted to offer feedback on the recent edition of Atrium

We understand that editorial policy is “to move away from a traditional alumni publication and to have interesting articles written by OPs about topics where they have a depth of knowledge rather than writing about Paulines and the Pauline Community.”

We have to ask: why? We receive frequent emails addressed to the “St Paul’s Community”. The only common features of this so-called “community” are the School, its alumni and activities involving either or both. While some contributions by individual OPs on areas of general interest may be welcomed, there does not seem a logical case for concentrating on them at the expense of the sort of “traditional” aspects found in most alumni magazines which are likely to be enjoyed by the widest possible range of OPs. The thoughts of someone who just happens to be an old boy on an unrelated subject may or may not be of interest but should not usurp the sort of School and OP-related material more normally associated with a publication of this type.

Some feedback on the new style may indeed be positive, but we would urge you to seek views as widely as possible in order to ensure any change is widely welcomed by Atrium’s customers, the OP community.

Bob Porter (1962–67)

Merrick Willis (1961–66)

A letter from Tel Aviv

Edward Evans (1993-98) writes: The Lighthouse on the Sea

I have the privilege of teaching literature at the Tel Aviv School of Arts. My students are at peak curiosity and restlessness, creativity and mischief, months before they leave home for the army, their bullish spirits reminding me of my senior years at St Paul’s School.

My bike ride takes me past city landmarks: the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Ichilov hospital, the Cameri Theatre, the National Opera, glass towers surrounding the Templar colony like sheets of placid sea, and the sprawling army headquarters.

I ride past images of merry grandparents and pretty girls. Graffiti on lampposts and stickers on walls demand an end to their suffering. They are the hostages; some dead, others praying for an end to the nightmare, can you ever come home from where you have been? An olive-green helicopter brings a military casualty to a helipad.

Tel Aviv is a blend of the old and the new, a city built on Eastern Mediterranean dunes, it is climbing upwards and looking towards the horizon. Her avenues are tree lined and well kept. Her people are anarchic and warm, and in the morning the streets are filled with children on their way, like me, to school. An air raid siren blared in the night. But the blue sky is clear; the day has begun, again, with quiet determination.

At the school gates, a municipal flag shows the city as a lighthouse on the sea. My students teach me that a righteous dream cannot be eviscerated or taken hostage by darkness. Our miraculous city shimmers like a mirage on desert sands. The hostages will return home and our mourners will bury our dead.

“Shalom, Dr Evans!” a cheeky student chirps.

“Good morning. Carry on,” I reply. The library of human cruelty, hypocrisy, and love has numberless texts in its timeless catalogue. We shall begin the day with Psalm 55, escaping the agony of the present on the wings of a dove. I nod at the armed guard and follow my students to class. Together, we shall shine our light across the sea. Together, we shall find salvation on the ethereal substance of sacred poetry. Together, we shall turn the dream of returning home into a tangible reality.

Tel Aviv is a blend of the old and the new, a city built on Eastern Mediterranean dunes, it is climbing upwards and looking towards the horizon.

David Abulafia’s Atrium Notes

Nowadays The Pauline devotes fascinating pages to the school trips to Greece, Italy and further afield. But, as I found when my daughters were at school, school trips have so much become part of the regular experience of children that it is easy to forget that once upon a time they were a rarer and therefore more special event. I was supposed to attend a CCF (RAF section) camp but I managed to escape its tedium by signing up for my one foreign expedition under Pauline auspices: a trip during the same days to the divided city of Berlin with about a dozen other boys. It was led by a German master whom I barely knew, as I was learning a little German with another master; and he was accompanied by a female nurse who seemed to have remarkably friendly relations with him. The cost was low, since we were subsidised by the AngloGerman Society, of which we were somewhat suspicious, as there was still a sense more than 20 years after the end of the war that one should not be too friendly to Germans. And we were constrained by the extremely tight regulations imposed by the Labour government that strictly limited the amount of money one could take out of the country. The £50 limit of those days would probably equal at least £1,000 today.

We flew directly from Luton airport – then just a shed – to Berlin, along one of the air corridors over the so-gennante Deutsche Demoktratische Republik, the so-called German Democratic Republic. The plane was an ancient, shuddering, slow museum piece that deposited us in the middle of the night at Tempelhof airport. When we reached our Pension we battled with the duvets, since we had no idea whether we were expected to climb inside them or just lie under them. But then some words of my former Classics master Mr McIntosh came to mind: there was a type of

feather-bed in Germany that you wrapped around yourself and was deliciously warm (a good idea as there was snow on the ground). That must be it.

As well as taking us to the Opera and various city monuments, the AngloGerman Association was keen that we should understand local politics, so we were taken to an observation post on the Berlin Wall and were plied with American and German leaflets and booklets. This made us all the keener to see what life was like on the other side, and we had the opportunity to do that, first with a guided tour and then on our own. In East Berlin there was a strong sense of stepping back in time, by comparison with the bustling shops and cafés of the Ku-Damm in West Berlin. (This was even more uncannily true in other DDR cities, as I discovered several years later, travelling by train to Prague via Leipzig, where the magnificent station was festooned with flags and East German soldiers were goose-stepping back and forth along the platforms). On both sides of the Wall all the men seemed to carry a briefcase. We asked the German master what they put in them and he said “Sausages”. I have no proof of that, but John Olbrich (1963-67) was brave enough to eat a sausage in a café in East Berlin, paid for with the lightweight East German coins we had acquired at an extortionate exchange rate of one East Mark for each West Mark.

On the famous Museum-Insel, Museum Island, the only museum that seemed to be open was the National Gallery. This disappointed me, as I had hoped to see the great Pergamon Altar – on every trip I have subsequently made to Berlin it has been undergoing restoration, so I have yet to see it. But the National Gallery had its compensations. Apart from a naturalistic painting of Lenin addressing a crowd that hung in the atrium, the museum consisted entirely

of remarkably similar Socialist Realist paintings of peasants and workers, divided up country by country, so there was a room for Bulgaria, another for Czechoslovakia, and so on through the Soviet bloc. I found a couple of guidebooks on sale there, guides to the ancient Egyptian and ancient Mesopotamian museums, which are sitting on the bookshelf opposite me as I write now. But where these museums might be we never discovered, and in any case the famous bust of Nefertiti, which we did see, was kept in a West Berlin museum until the city was re-unified.

Then we were off to Checkpoint Charlie or another crossing-point, where gruff East German, or maybe Russian, border guards, grilled us: “Haff you any money of ze DDR?” If so, it was supposed to be surrendered, even a few pfennigs. Nonetheless, I kept some of my last pfennigs, having spent others on that day’s Neues Deutschland, the boring, propagandist newspaper of the East German Communist Party (very good on whether the country was meeting its tractor targets), and by carrying it on the West Berlin metro I prompted quizzical glances from old Berliners. I still have that copy, with its fulsome praise for Walther Ulbricht and the other die-hard members of one of Europe’s most repressive post-war governments – though nowadays revisionist historians try to re-cast the DDR as not so much worse than West Germany, which seems to me perverse. It was certainly a marvellous educational experience, though I am not sure it did much for my German. I do wonder, though, whether modern parents, seeking to save some of the VAT they must now outrageously pay on their fees, will decide that their budget does not quite extend as far as a school trip to the Acropolis or the Alhambra.

Briefings

St Paul’s: ‘Considerably Older than the German Empire’

The Pauline in 1917 included this wonderful exchange between two Old Paulines. The correspondence of J Gibson Harris and the Editor brilliantly sums up the wit and camaraderie of Paulines during the First World War.

The Montgomery Room

Since the redevelopment of the Barnes site, the Montgomery Room has been on the ground floor to the north of the main entrance – where the G and H Club lockers used to be. Until this year its walls were decorated with many of the same paintings as the earlier first floor incarnation. Portraits of High Masters since 1968 had been added, but it was little changed.

To the Editor of The Pauline:

DEAR SIR – Has your attention been drawn to the fact that the colours of the Old Paulines (red, white and black) are those of the German nation, and I believe of the Prussian Guard? I have only recently become an OP, but since I have worn the colours, quite a number of people have drawn my attention to it. I hope some way will be found of remedying this.

Yours truly, An OP.

A reply was duly received: Editor of The Pauline – This unfortunate ambiguity had escaped us. The remedy seems to lie in persuading the German nation to change their colours – along with their Kaiser and their Kultur.

Another Old Pauline agreed.

To the Editor of The Pauline: SIR – I thought every Old Pauline was aware that the colours of the Old Pauline Club were similar to those adopted by the Prussian Guard. Some years ago, when travelling in Norway, I met a German who called my attention to the fact that I was wearing the German colours. I am afraid he was not altogether pleased with my answer when I informed him that the colours were those of a Foundation considerably older than the German Empire.

Yours truly,

J GIBSON HARRIS

Those High Masters, except for Mark Bailey, now adorn other walls on the Barnes site and have been replaced by images of eminent Old Paulines who attended St Paul’s in the last decade of the 19th century through to the Crowthorne evacuation years. The portrait of Montgomery remains, as does his map, used to plan the D Day invasion at the Hammersmith school site.

Paul Nash (1903-08)

Sir Isaiah Berlin OM CBE (1922-28)

Sir Peter Shaffer CBE (1942-44)

James Clerk Maxwell Garnett CBE (1893-99)

Three of the four OP portraits selected would be high on any list – Paul Nash (1903-08), Sir Isaiah Berlin OM CBE (1922-28) and Sir Peter Shaffer CBE (1942-44), but the fourth was less well known to Atrium

James Clerk Maxwell Garnett CBE (1893-99) was a Foundation Scholar and played for the 2nd XV. On leaving School, Garnett went up to Trinity College, Cambridge. In 1904 he started work as an examiner at the Board of Education and in 1912, became the Principal of the Municipal School of Technology at Manchester where he encouraged the municipal schools to focus on higher education. He was awarded a CBE in 1918 for this work and published on the importance of character education in schools in 1939. In 1920 he became the General Secretary of the League of Nations Union (LNU), which worked to encourage support in Britain for the League of Nations. LNU became one of the most influential peace organisations in Great Britain. He held this post until 1938.

Philip Gaydon, who teaches Theology and Philosophy and is also Head of Character Education at St Paul’s, commented “When researching Garnett as part of looking into OPs connected with character education, I was struck by his relationship with “integrity”. This clearly played an important role in his educational thinking, and his theory that good character can only be built upon “a single wide interest” that provides an individual with a philosophy and purpose typifies this (Knowledge & Character : 279). He appears to have lived this theory in his professional life as well, with a clear commitment to educating for peace. Of course, as with many who so firmly and whole-heartedly commit themselves to a cause, his colleagues were sometimes divided between admiration and frustration – with some at the LNU recounting that they used to joke that “his initials stood for ‘Just Call me God’.” (Oxford Dictionary of National Biography)”

Osterley Revisited

If you want somewhere different to walk the dog, try the grounds of Osterley House. You can combine it with a visit to the school playing fields nearby that were last used in the 1970’s.

The Thursday schlepp out to Osterley for games afternoons was a part of generations of Paulines’ lives. On the drive out from central London, you can test yourself on the order of the tube stations passed on the journey to the suburb – Hammersmith, Turnham Green, Acton Town, South Ealing, Northfields, Boston Manor and Osterley.

On finding the entrance to the Osterley playing fields, you will be denied access as they are now the training ground of the Premiership team, Brentford FC. It all looks very impressive. The Bees of course play in the OPC (and German Empire) colours of red, white, and black.

Osterley Park is fine dog walking territory – accessible, dry enough, dotted with mature trees and well maintained, but not at all municipal. It was once owned by Thomas Gresham (1531-37), who could well be the wealthiest Old Pauline ever. He bought the manor of Osterley and built a new house on the site in the 1670’s. He bought the neighbouring manor of Boston a little later – why not?

Osterley House has been rebuilt since Gresham’s day. It is now owned and run by the National Trust. The banking Child family became owners in the eighteenth century, as bankers did of many grand houses at the time. They commissioned the Scottish architect Robert Adam in 1761 to transform Osterley into what Horace Walpole described as ‘the palace of palaces’.

Here are some gobbets Atrium has gleaned about Thomas Gresham. Sir Richard, his father, wanted him to become a merchant so sent him,

after St Paul’s, to Gonville and Caius, Cambridge and at the same time apprenticed him in the Mercers’ Company. In 1543, Thomas was admitted as a liveryman and later that year, left England for Belgium. Based in Antwerp he became renowned as a successful investor on the Antwerp Exchange. In 1551 he came to King Edward VI’s financial rescue by somehow managing to increase the pound’s value so successfully that the King’s debts were almost all discharged. Gresham was well rewarded. He also served Queen Mary and notably Queen Elizabeth, becoming a Knight Bachelor in 1559. Again, he was very well rewarded. Thomas then proposed and built the Royal Exchange modelled on the Antwerp Bourse.

He accrued significant rents that were bequeathed to the City Corporation and the Mercers’ Company for the purpose of instituting Gresham College, at which he stipulated that seven professors should read lectures, one each day of the week, in astronomy, geometry, physic, law, divinity, rhetoric and music. The College was London’s first institution of higher learning opening in 1597. It remained in Gresham’s mansion on Bishopsgate until 1768. Since 1991, the College has operated at Barnard’s Inn Hall in Holborn and regularly welcomes visiting speakers who deliver lectures on topics outside its usual range and also hosts seminars and conferences. There are over 140 lectures a year, all of which are free and open to the public.

Geoffrey Matthews (1972-77) and Chris Vermont (1973-78) are current members of the Gresham College Council.

When Water Rats Meet

Paul Ganjou’s career was in Financial Services but he has always had family show business connections. His father, George, had been a variety artiste and, as an impresario in the late 1950’s, had booked several promising young artists, including then unknowns Jimmy Tarbuck and Cliff Richard.

Paul is a member of several entertainment charities, including the Grand Order of Water Rats (GOWR), where he knew OP and Past King Rat Nicholas Parsons (1937-39) well. He is also on the Executive Committee of the Royal Variety Charity (RVC), whose main fund-raising event is the annual Royal Variety Performance (RVP).

Paul’s family appeared in two RVP shows in the 1930s and he has attended most of the RVPs since 1963, when Beatle John Lennon famously invited posher audience members to “rattle their jewellery”. He kept the programme and over the years accumulated a large collection of historic programmes, many signed by the cast, which he has recently donated to the GOWR’s London museum and

to Brinsworth House, the residential Care Home for retired entertainment people, which is supported entirely by the RVC and where the history of the Charity is fully recorded.

At the 2024 RVP in the Royal Albert Hall, Paul had the honour of meeting the RVC Patron, HM King Charles III and noticed that His Majesty was wearing a Grand Order of Water Rats emblem, as indeed was Paul. It was an obvious topic of conversation especially as the lady next to him in the image below, Pat Church, is the widow of Past King Rat Joe Church, who had initiated the King into the Grand Order in 1975. The King found it highly amusing to be reminded that a ‘King’ had initiated him into the Order when he was only a Prince.

Pauline Scrabble Finalist

Better late than never, with thanks to Jewish News, Atrium has news of the final of the 2022 UK Scrabble Championship which saw Elie Dangoor (1972-76) play a grand master. It all came down to the last letter in the bag.

Elie narrowly lost in a tense match to Brett Smitheram, 43, a Scrabble grand master and the then reigning UK national Scrabble champion who is one of the most successful players in the history of the game.

Dangoor, whose brother David (1976-80) is also an OP, took an early lead with words such as ‘blowiest’, ‘pricier’, and ‘encave’ – a triple word score – but Smitheram recovered taking the match to the last letter.

“He needed an E – a one-in-eight chance – and he got it,” said Elie, who also plays backgammon, chess, and bridge. “It was most unfortunate. Still, it was a very satisfying tournament, as I was only seeded 11th. It’s a shame because I would have been the oldest national champion if I’d won.”

Elie is a real estate director who chaired the World English-Language Scrabble Players Association until 2020.

Paul Ganjou (1960-65) and HM King Charles III

Monarchs meet

Pauline Gallantry

Sam Alexander (1995-98) MC

Sam Alexander was born in 1982 in Hammersmith. After Colet Court and St Paul’s, Sam worked in construction until he decided on a change of direction. He joined the Royal Marines in July 2006 and was passed fit for duty in October 2007.

On completion of his training, he was appointed to the Fire Support Group in Mike Company, 42 Commando Royal Marines. He later moved to Kilo Company. In 2009, he was awarded the Military Cross for gallantry.

While serving in Afghanistan, he charged down a group of insurgents to draw fire away from an injured colleague. Having used all the ammunition in his machine gun, he continued his assault with his 9mm pistol until that too was empty – forcing the enemy to retreat. The citation for his award said he carried out his brave actions “despite being completely exposed to heavy and accurate enemy fire”.

On his return from operations, Sam trained as a Heavy Weapons (Anti-Tank) specialist and was appointed to Juliet Company, before returning to Afghanistan. He was on patrol in Helmand province in 2011 when killed by an Improvised Explosive Device. He was 28. He is buried in St Mary’s Churchyard, Bickleigh, Tiverton.

Sam married Claire Wills in 2009 and in 2010, their son Leo was born. His widow, Claire died in March 2020.

A plate on Hammersmith Bridge in his memory was unveiled in 2012 by the mayor of Hammersmith and Fulham, Frances Stainton. The quotation is taken from a poem written by Sam’s mother, Serena, who taught at St Paul’s in the 1990s.

The inscription reads: In loving memory of MNE Sam Alexander MC. Born Hammersmith 1982, died Afghanistan 2011. One of the bravest of the brave, who died for you. Still whispers in your ear: “now, you, be brave too!”

Pauline Pianists

In February Aron Goldin (2014-16) released his second album as a classical pianist

It was recorded at Abbey Road Studios and features the debut of South African soprano Masabane Cecilia Rangwanasha, a rising star of the opera world, winner of the Herbert Von Karajan Prize 2024, and Cardiff Singer of the World Song Prize 2021.

Noah Zhou (2014-19), currently a Master’s student at the Royal Academy of Music, is the recipient of many awards including the Young Pianist Foundation European Grand Prix, Horowitz International Competition, Drake Calleja Trust and the Hattori Foundation.

A first prize winner at competitions in Rio and Valsesia in Italy, recent concerto performances include appearances in the Netherlands, Ukraine and Brazil. Noah’s virtuosic lunchtime recital on January 15 at the Wigmore Hall saw him perform Rachmaninov’s Etudes-tableaux Op.33, Clementi’s Piano Sonata in A Op.33 No.1 and Liszt’s Reminiscences de Norma S394

Noah Zhou

Aron Goldin

Pauline Grammy

At the 67th GRAMMY awards ceremony in February, it was announced that Dom Shaw (201217) won in the ‘Best Engineered Album, Non-Classical’ category for i/o.

Dom works at Real World Studios and is a music engineer and multi-instrumentalist songwriter performing as Waterlog. He is also a record producer and has worked with Peter Gabriel and Birdy, among other artists.

Paulines on Netflix

Henry Lloyd-Hughes (1998-2003) is set to join royalty of British cinema in a Netflix production of The Thursday Murder Club Other stars include Helen Mirren, Pierce Brosnan, Ben Kingsley, Celia Imrie, David Tennant, Jonathan Pryce and Richard E. Grant.

The film is based on Richard Osman’s novel of the same name published in 2020 about septuagenarian amateur sleuths attempting to solve a murder. One had been a spy, one a nurse, one a trade union official and one a psychiatrist.

Also on Netflix, Bank of Dave 2: The Loan Ranger continues the Dave Fishwick story. Having established his community bank for the people of his native Burnley in Bank of Dave, this time local hero Dave Fishwick takes on a new and even more dangerous adversary – The Payday Lenders of Britain, who Dave sees as having caused so much misery through debt. For a few days in January the film was the most watched on Netflix. Rory Kinnear (1991-96) again plays Dave Fishwick. During its promotion Rory said, “It was so wonderful to see how many people responded to the first film. They really seemed to love it, so it’s great to be back.”

Pauline Brit

Electronic duo, Chase & Status, won the Brit Awards’ Producer of the Year last February.

Saul Milton and Will Kennard’s (1994-99) production credits feature on tracks by major artists including Rihanna, Rita Ora, Kano, Tinie Tempah, Example and Plan B.

Chairman of the Brit Committee for 2024 and managing director and president of promotions at Atlantic Records, Damian Christian, added: “For two decades, Chase & Status have been at the heart of UK dance music. As one of the most progressive and prolific groups around, it’s no surprise that they are still at the top of their game. After an incredible 2023, Chase & Status thoroughly deserve to be crowned producers of the year”.

Reflecting on the win, the duo said: “We couldn’t be more proud – we’ve been flying the flag for British music now for a long time, we’re super proud of all the music that has come out of the UK. As producers, and as a creative duo, I think we are probably in one of the best places we’ve been.”

Dom Shaw

Will Kennard and Saul Milton

Henry Lloyd-Hughes

Rory Kinnear

Pauline Appointments

Mark Charkin (1984-89) has been appointed Executive Director of GBx. In 2013 Mark moved full-time to San Francisco. He helped scale start-ups such as Bebo, and King Digital Entertainment (Aka Candy Crush) and has worked in an advisory capacity at Snap, Brightroll and Onfido among others. More recently, Mark has worked around virtual humans and AI and was involved in ABBA Voyage. GBx is a private network for successful British entrepreneurs, investors and senior British tech executives in the Bay Area. The non-profit community has built up a large and loyal member base including a multitude of Unicorn founders and c-suite at: Apple, Airbnb, Google, Monzo, Calm, Bebo, Trulia and Slack among others. Entrepreneurial OP Amaan Ahmad (2017-19) is one of its members.

Roger Bland (1968-72) has been awarded a CBE for services to heritage. He retired in 2015 from the British Museum, where he was Keeper of the Department of Britain, Europe and Antiquities and founded the Portable Antiquities Scheme. His field of expertise is Roman coinage and hoards. He is currently President of the Royal Numismatic Society and is writing a volume in the series Roman Imperial Coinage His book Hoards and Hoarding in Iron Age and Roman Britain (with 10 other authors) was published by Oxbow in April 2020. He is a Lay Minister in the Diocese of Norwich.

Floyd Steadman (Honorary OP) has been presented with an Honorary Doctorate from Brunel University. Floyd’s careers have spanned elite rugby, as captain of Saracens, and education as Headmaster at several prep schools after his time at St Paul’s. Amongst his other commitments, Floyd, now travels the length and breadth of the country to talk to people and students about unconscious bias. He was awarded an OBE in the King’s first New Year’s Honours in 2023, for services to rugby, education and charity.

Freddie Sayers (19952000) the chief executive of Old Queen Street Ventures (OQS) and editor of UnHerd, has become the publisher of UnHerd and The Spectator Sir Paul Marshall (father of Winston Marshall (2001-06)) has completed a £100m takeover of The Spectator magazine. Marshall, a backer of GB News TV channel which launched three years ago, has acquired the magazine through OQS.

Tom Adeyoola (1990-95), co-founder of Extend Ventures, non-executive board member at Channel 4, St Paul’s Governor and OPC Vice President, has been appointed a member of the Creative Industries Taskforce led by Baroness Shriti Vadera and Sir Peter Bazalgette. The Taskforce has been set up to help deliver a plan to grow the creative industries. The plan will be published alongside an Industrial Strategy and will set out new policies and government interventions that will help to deliver a further boost to the creative industries’ potential for spreading growth and opportunity for all.

Tom Hayhoe (1969-73) has been appointed as Covid CounterFraud Commissioner, reporting to the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Chancellor Rachel Reeves said on the appointment “Tom Hayhoe brings a wealth of experience and will leave no stone unturned as a commissioner with free rein to investigate the unacceptable carnival of waste and fraud during the pandemic.”

Pauline Books

Atrium (unless otherwise described) uses reviews provided by authors or their publishers.

Edward Evans (1993-98)

Shakespeare’s Mirrors

Edward reviews his own book.

Shakespeare’s Mirrors proposes a radical new way of conceiving Shakespearean drama, the clues to which were left behind in the obsessive and voluminous use of mirror metaphors to describe “the purpose of playing”.

Mirrors had been used since early Attic tragedies as a metaphor for drama. As such, mirrors symbolised the way drama reflected truths about human performance back onto spectators. Shakespeare overturned this millennia-old

tradition, suggesting that mimetic display could not reveal the truth of human nature which lies beyond the visible, spoken and performed.

This densely researched and meticulous work reimagines Shakespearean drama as the projection of conscience onto the early modern stage, revealing characters at odds with their dramatic duties (the clichéd roles of the mimetic tradition), determining instead to find poetic resolution to their sense of being separate from the action by reimagining the theatrical world in which they find themselves conceived.

Thus, Hamlet’s famous “the mirror up to nature” speech on drama overturns the idea of dramatic action as a feasible representation of the metaphysical truth – “that within which passes show”.

This rolling revolution and counter-revolution in Shakespearean drama, drawing us back to the future by recentring the Pauline doctrine of the theatre of the world – “through a glass darkly”– was made possible by two simultaneous developments: the invention of perfect glass mirrors in Venice and the publication of the Geneva Bible in the decade of Shakespeare’s birth.

Perfect glass mirrors exposed the lie that a viewer might see metaphysical reality any more clearly by staring at a reflection of themselves in the world. Meanwhile, Pauline theology translated into vernacular English in the Geneva Bible supplied an alternative ethics and ontological metaphysics to remake drama in the image that scripture provided, highlighting the obsolescence of Elizabethan mirrors as an object, like a twenty-first century selfie, in revealing the essence of humanity – “conscience”–that which Hamlet calls his “mystery”.

Mirror metaphors and the associated word “conscience”, physical and metaphysical embodiments of the Elizabethan age, were conceits accessible to Shakespeare’s audience, but quickly faded into obscurity in the centuries that followed. Shakespeare’s Mirrors reanimates the source of the dramatic revolution that saw characters formed by acts of their own imagination.

Shakespeare’s Mirrors was published in September 2024 by Routledge.

Zahaan Bharmal (1990-95)

The

Art of Physics:

Eight Elegant Ideas to Make sense of Almost Everything

Zahaan reviews his own book. People are messy. Science is methodical. At first glance, the two could not be further apart – or so I thought. In my debut book, The Art of Physics, I take readers on an unexpected journey, showing how ideas from physics can illuminate the chaotic, unpredictable, and deeply human experiences of modern life. This book is rooted in my own story. As a lonely and confused student at St Paul’s, I turned to physics for answers. Inspired by The Hitchhiker’s

Guide to the Galaxy and its tongue-incheek claim that the answer to life’s ultimate question is “42”, I began a quest for answers; answers I hoped physics could provide.

That journey led me to study physics at Oxford and set the stage for a career that has taken me from management consultancy to Whitehall to The World Bank to Google, where I have worked for the last 16 years. Yet, as I can candidly reveal, life has not always been straightforward. From losing my job to navigating heartbreak and even facing a mid-life crisis, my path has been anything but smooth. Through it all, however, physics has been my constant guide.

At its heart, The Art of Physics explores how scientific thinking can provide tools for making sense of life’s messiness. Drawing on concepts from quantum mechanics, chaos theory, thermodynamics, and more, I seek to connect abstract scientific principles to everyday dilemmas. Chaos theory, for instance, becomes a framework for dealing with crises and unpredictability. Thermodynamics sheds light on managing energy and motivation. And quantum mechanics offers insights into the seemingly irrational choices we all make.

One of the book’s main aims is to show the balance between the personal and the universal. I try to write with honesty and humour about my own experiences, from grappling with unfairness to feeling like a stranger in my own home. These moments of vulnerability I hope make the book relatable, even for readers with no background in physics. At the same time, I highlight the work of real-world physicists applying their expertise to tackle some of society’s most pressing

issues, from climate change to economic inequality. The result is a book that I hope feels both intimate and expansive, offering readers practical wisdom alongside a broader perspective on the world.

The Art of Physics has received praise from several esteemed authors and thinkers.

Alain de Botton, author of The Consolations of Philosophy, describes it as “exceptionally interesting.” Thomas Erikson, known for Surrounded by Idiots, asserts that it is “a book that will transform how you understand human behaviour.” Michael Brooks, author of 13 Things That Don’t Make Sense, finds it “joyful, fascinating and highly original.” Cal Newport, author of Deep Work, commends it for identifying “elegant explanations for our messy world.”

Readers looking for a traditional science book may be surprised by The Art of Physics, but that is precisely the point. The book invites us to see science not as a collection of formulas, but as a toolkit for navigating life’s complexities. I hope my writing is accessible, thoughtprovoking, and infused with a quiet optimism that encourages readers to embrace the unknown.

“Physics teaches us to embrace the questions.” Whether you are a physicist, a curious reader, or someone searching for clarity in a chaotic world, The Art of Physics is an invitation to think differently. By the end of the book, you may not find the ultimate answer to life, the universe, and everything –but I hope you will come away with a deeper appreciation for the beauty of the questions themselves.

You can order your copy at: www.theartofphysics.com

Nick Brooks (1965-70) Fraud

Nick Brooks spent 40 years working in the City of London as a chartered accountant. When he retired in 2018, he wrote and published his first novel – Betrayed. His second novel, Revenge was the sequel. Fraud is the third in the series. Nick is the OPC Treasurer and a Vice President of the Club. He lives in Chiswick and is the fourth generation of his family to live in this leafy suburb. In Fraud, two suspicious deaths lead Will and Jay Slater and their old adversary, Inspector Dawkin, into the murky world of powerful business and politics. A huge multi-national organisation will stop at nothing to win a contract to handle the UK’s nuclear waste. With fraud at the heart of the case, and hunted by a dangerous assassin, the Slaters travel to South Africa and Scotland in a deadly quest for the truth.

‘A hugely enjoyable read. Superbly crafted plotting, here is a depth to the narrative, which helps to build up the drama and suspense. The characters within the book are well written and fleshed out. I found myself eagerly turning the pages as the hunt to discover the truth gathered pace. It is quite a pacey read where the action moves quickly around, everything building to the finale, the action moves seamlessly between Scotland, London and South Africa. You get a real sense of atmosphere. A read which, at times, had me on the edge of my seat, where the action twists and turns. The author uses the narrative to build scenes with intensity and drama, equally, the writing creates plenty of suspense and tension, leaving you unsure as to the fate of the characters. Overall, this was a deeply satisfying read, the kind of book which would make a perfect beach read. Would certainly be looking out for the author’s previous books.’

AMWBOOKS REVIEW

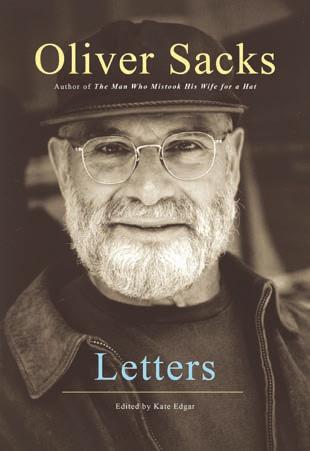

Oliver Sacks (1946-51)

Letters (Edited by Kate Edgar)

These are the letters of one of the greatest observers of the human species, revealing his passion for life and work, friendship and art, medicine and society, and the richness of his relationships with friends, family, and fellow intellectuals over the decades. After St Paul’s Oliver Sacks read medicine at Queen’s College, Oxford. He completed his medical training at San Francisco’s Mount Zion Hospital and at UCLA before moving to New York, where he soon encountered the patients whom he would write about in his book Awakenings. Sacks spent almost fifty years working as a neurologist and wrote many books, including The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Musicophilia, and Hallucinations, about the strange neurological predicaments and conditions of his patients. The New York Times referred to him as ‘the poet laureate of medicine’. His memoir, On the Move, was published shortly before his death in August 2015.

Oliver who describes himself as a “philosophical physician” and a “neuropathological Talmudist” wrote letters throughout his life: to his parents and his beloved Auntie Len, to friends and colleagues from London, Oxford, California, and around the world. The letters begin with his arrival in America as a young man, eager to establish himself away from the confines of postwar England, and carry us through his bumpy early career in medicine and the discovery of his writer’s voice; his weight-lifting, motorcycle-riding years and his explosive seasons of discovery with the patients who populate Awakenings; his growing interest in matters of sight and the musical brain; his many friendships and exchanges with writers, artists, and scientists (to say nothing of astronauts, botanists, and mathematicians), and his deep gratitude for all these relationships at the end of his life.

Sensitively introduced and edited by Kate Edgar, Sacks’s longtime editor, the letters deliver a portrait of Sacks as he wrestles with the workings of the brain and mind.

‘Here is the unedited Oliver Sacks – struggling, passionate, a furiously intelligent misfit. And also, endlessly interesting. He was a man like no other.’

ATUL GAWANDE

Author of Being Mortal

Ian Young (1954-58)

The Private Life of Islam: An Algerian Diary

Ian Young spent a summer as a medical student in a provincial maternity unit in Algeria. This book is taken from the diary he began on arrival, when he found himself the privileged witness of the insides not just of Kabyl women, but also some muchtrumpeted ideology. The immediate villains are a couple of expatriate Bulgarian gynaecologists.

Dr Vasilev, at the closing stages of a career of fathomless incompetence, forms a bond of affection with the author and they spend many hours in the office over an old route map of Bulgaria, discussing mileages and motorcycles as Maternity drifts beneath them like an abandoned ship.

Dr Kostov packs a powerful bedside punch and saves his humanitarian feelings for the health of the Deutschmark. The two form a macabre comic team as they take the reader through a series of medical nightmares. But their lot is scarcely more enviable than that of their female victims: the foreign doctors working in blood, excrement and death are the unhappy executors of the most respected attitudes in Algeria. The Private Life of Islam is a ruthlessly clear-sighted view of a particular place at a particular time. It is also a classic in the art of storytelling.

Robin Renwick (1951-56)

The Intelligent Spy’s Handbook: Spies and Writers, Writers and Spies, and the Contribution of British Spies to English Literature

Robin Renwick, Lord Renwick of Clifton KCMG, was a crossbench peer in the House of Lords. He was ambassador to South Africa in the period leading to the release of Nelson Mandela, then British ambassador to the United States between 1991 and 1995. He was also the author of Fighting with Allies, A Journey with Margaret Thatcher and Helen Suzman: Bright Star in a Dark Chamber

Few professions comprise such an eclectic mix of personalities as that of intelligence. The characteristics required to thrive as a spy – ideological conviction, ego, the ability to manipulate, deceive and remain cold – have created some of the most compelling and enduring figures in history.

In The Intelligent Spy’s Handbook, Robin Renwick provides an overview of the biggest names in the world of espionage, with a wonderful eye for the details that bring each of them to life. We hear, for instance, of how Kim Philby, to have fun at the expense of his colleagues, kept a photograph in his office of Mount Ararat – taken from the Soviet side.

We see how the audacious, far-fetched ideas of the naval officer Ian Fleming, aside from creating the most famous of all spies, may have actually inspired the real-life Operation Mincemeat. And the darker side of some of our more heroic stories is exposed, from the chemical castration of Alan Turing to the personal sacrifices Oleg Gordievsky made to become Britain’s most successful Soviet mole.

(An obituary for Robin appears later in the magazine).

‘A real achievement, personal as well as literary.’

DAVID PRYCE-JONES

The Times

‘The most important book to have been written about Algeria since Independence and that it should be compulsory reading for every member of the Algerian government.’

EDWARD BEHR

Newsweek

Sam Freedman (1994-99)

Failed State: Why Nothing Works and How We Fix It

In Failed State, Sam Freedman, one of Britain’s leading policy experts, explains why it is harder than ever to get a GP appointment. Burglaries go unpunished. Rivers are overrun with sewage. Real wages have been stagnant for years, even as the cost of housing rises inexorably. He asks why everything is going wrong at the same time?

It is easy to blame dysfunctional politicians who are out for themselves. But, in reality, it is more complicated. Politicians can make things better or worse, but all work within our state institutions. And ours are utterly broken. Sam offers a devastating analysis of where we have gone wrong. With historical depth and plenty of infuriating examples, he explains why British governance has fallen so far behind. Speaking to politicians of all stripes, civil servants and workers on the frontline, this book bursts with insight on the real problems that are so often hidden from the front pages. The result is a witty, landmark book that paves the way for a fairer and more prosperous Britain.

Marc Griffiths (1984-89)

Get Happy: Make your dreams come true NOW!

Marc Griffiths has addressed more than a million people in over 5,000 talks. As a keynote speaker, he has researched, written, and spoken for 25 years, speaking to all types of audiences on the subjects of Happiness, Personal and Professional Development, Self-Esteem, Goals, and Dream achievement.

His humour and ventriloquism make his talks exciting and different, while his inspiration and wisdom bring immediate and long-term results. Originally from the UK, Marc speaks internationally and now lives in Los Angeles with his wife and five children.

Jack Furniss (1998-2003) Between Extremes

‘We can only hope that every member of the new government will read and digest this book’

DAVID AARONOVITCH

‘Brilliantly timed and frighteningly true’

SIR ANTHONY SELDON

Everyone lives in a box. Are you going to keep living an average life, or are you going to get out of your box and start to make your dreams come true? There is a secret to success. There is a specific key you need. How much do you want it? Get Happy: Make your dreams come true NOW! is an inspirational book, filled with humour, to help you get you what you want.

Jack is head of the History and Politics Department at Old Palace of John Whitgift, in Croydon. He has graduate degrees in History from the University of Oxford and the University of Virginia. Between 1861 and 1865, northern voters fortified Abraham Lincoln’s administration as it oversaw the end of the institution of slavery and an unprecedented expansion in the size and scope of the federal government. Since the United States never considered suspending the democratic process during the Civil War, these revolutionary developments – indeed the entire war effort – depended on ballots as much as bullets. Why did civilians who, at the start of the conflict, had not anticipated or desired these transformations to their society nonetheless vote to uphold them? Between Extremes proposes an answer to this question by revealing a potent strand of centrist politics that took hold across the Union and provided the conservative rationales that allowed most northerners to accept the war’s radical outcomes.

‘A scintillating explanation of how, during the political turbulence of the Civil War, the American Union’s key state governors harnessed the electoral muscle of conservative centrist patriotism. Furniss’s astute examination, fresh in conception and compelling in argument, rightly casts the malleable Union party coalitions as essential to Lincoln’s purposes and national survival. Quite simply, a lasting gem of a book.’

RICHARD CARWARDINE

William Mallinson (1965-70)

The Real Story of the Relationship between Britain and Greece

There are thousands of books about England, on the one hand, and Greece, on the other, but none which looks specifically and critically at the story of the relationship between the two countries and their peoples, and in particular at how England has influenced modern Greece, not always to the latter’s benefit.

This book has been written by a former British diplomat with a Greek mother and English father, who has lived for the last 30 years in Greece. The book gives a true picture of the good, the bad and the ugly, warts and all, up until today, despite the efforts of various party-politically influenced academics and officials to play down embarrassing facts which do not fit their agenda. The book will appeal to discerning tourists as well as to international historians, Anglophiles and Hellenophiles, and will inject more transparency into the story, in order to rock the boat of apathy, rather than paper over the cracks, and thus promote and improve relations between these two countries.

William is a member of the editorial committee of the Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies. His books include Cyprus: A Modern History; Cyprus, Diplomatic History and the Clash of Theory in International Relations; Britain and Cyprus: Key Themes and Documents since World War Two; Kissinger and the Invasion of Cyprus; and Guicciardini, Geopolitics and Geohistory: Understanding Inter-State Relations

Nick Bromley (1958-62) Cakes and Ale:

Mr Robert Baddeley and his Twelfth Night Cakes

Nick Bromley’s book is a highly illustrated biography of the life and times of Baddeley, who was a member of Garrick’s company at Drury Lane for over 30 years. A sterling actor, he was married to the infamous Sophia Baddeley and fought a duel with George Garrick because of her. It also tells the story of the Baddeley Cakes which have been cut at Drury Lane on each January 6th from 1795 to the present day.

Cakes and Ale: Mr Robert Baddeley and his Twelfth Night Cakes explores the rich history of a beloved British tradition. It delves into the life of Mr Robert Baddeley, a renowned actor from the 18th century who was famous for his Twelfth Night cakes which remain an integral part of the festivities surrounding the Twelfth Night celebrations. The book offers a fascinating glimpse into the culinary and cultural significance of these delectable treats, providing a captivating read for anyone interested in British history, theatre, or gastronomy.

Bernard O’Keeffe (Honorary OP)

The Masked Band

Bernard O’Keeffe taught English at St Paul’s from 1994 to 2017 and was Senior Undermaster from 1997 to 2006. Since he retired, he has written a series of novels featuring DI Garibaldi, all of them set in Barnes.

The Masked Band is the fourth in the series. It starts with a concert. Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan, Paul McCartney, David Bowie and Debbie Harry. They call themselves The Okay Boomers and it is quite some band. And it is quite incredible to see them playing the Bull’s Head in Barnes on a Sunday night.

But all is not as it seems. Behind life-like masks are five local celebrities. They are playing for fun and trying to keep their identities hidden, but when the body of a man is found at one of their houses their secret’s out. DI Garibaldi is on the case and he is soon asking a few questions.

Did the dead man fall from the first-floor window or was he pushed? Why was he wearing the Mick Jagger mask? And why have all the other masks disappeared? When members of the Okay Boomers are attacked by someone wearing those very masks, Garibaldi’s investigation closes in on each of the celebrities and he wonders what else they have been hiding.

Paradise Lost

Milton’s Epic About the Fall is Central to Christianity

Theo Hobson (1985-90), author of Milton’s Vision: The Birth of Christian Liberty discusses Paradise Lost and reviews What In Me Is Dark: The Revolutionary Life of Paradise Lost by Orlando Reade.

Paradise Lost is a very long poem written by John Milton (1620-25). It is a retelling of the Christian story of the Fall. Published in 1667, it was a staple of Englishspeaking culture for a few centuries, read by anyone with any claim to intelligence. Who reads it now?

While at School I did not try it: the aura of grand traditionalism was forbidding. At university I loved it. As a literature student with a strong interest in theology, that was not very surprising. Is the epic worth the attention of the general reader? It is hard to say. If you have no sympathy with its religious perspective, it is probably not for you. Of course, plenty of critics go on about its contemporary psychological and political relevance, but maybe they just want to write a book about something. I will come on to one of these critics shortly – first, my take on the poem.

As you might expect of a very long poem, some bits are more compelling than others. Some skipping and skimming is called for. Otherwise, you will probably give up in Book One (out of 12).

Of course you have to read the very first bit, in which Milton grandly presents himself as an inspired prophet and then introduces us to bolshy Satan. But once you have got a sense of the stormy antihero, feel free to glide over

the long political speeches in hell, which continue through most of Book Two. The start of Book Three is an interestingly weird conversation between God and Christ, then there is more of Satan’s tormented plotting. Again, feel free to skim it. Modern critics, starting with the Romantics, have over-egged Satan as the star of the epic: he is not, he is just a very naughty antichrist. The real star of the epic is Eden.

Maybe all the build-up is necessary, maybe all the grand CGI descriptions of cosmic space help us to believe in Eden, when we get there at last in Book Four. We partly see it through Satan’s eyes, as he comes aprowling. After some description of the lush landscape, we meet our first parents – and they are shockingly naked. The verbal camera lingers on Eve’s sexy hair which falls to her slender waist in ‘wanton ringlets’. It is a funny sort of para-porn, in which we are often reminded that the scene should not be viewed through the impure lens that we cannot help viewing it through –on one level we are dirty voyeurs like Satan. I find this thrillingly paradoxical, as well as more mundanely thrilling (yes, they do it).

The rest of the epic is a mix of happy (and then less happy) domestic scenes, and conversations with angels, who tell Adam about theological history (Eve goes off gardening preferring to hear

it later from Adam, so he can mix his teaching with kissing – a charming but sexist detail). There is a long description of war in heaven that you might want to skip. In Book Seven there is a lovely description of the creation of the world – for example we see mountains rising up, ‘their broad bare backs upheave / Into the clouds…’ But Book Eight is best of all: Adam recounts finding himself in Eden, at first alone, and then meeting Eve, and desiring her. She is bashful and reluctant, which does not make much theological or biological sense, but makes for a pleasing sex-scene –

As you might expect of a very long poem, some bits are more compelling than others.

‘To the nuptial bower / I led her blushing like the morn…’. There is also a lovely passage in which Adam tells the angel that his love of her feels excessive, a threat to rational and godly order: ‘All higher knowledge in her presence falls/ Degraded, wisdom in discourse with her / Looses discountenanced, and like folly shows…’ I remember finding these words very apt as a shy bookish love-struck undergraduate.

Paradise Lost

Spoiler alert: this sensual and horticultural bliss cannot last: Book Nine tells the drama of the Fall, in which a bit of flattery of Eve gets Satan everywhere. When she finally eats the famous fruit, the cosmic change is presented in ecological terms:

Earth felt the wound, and nature from her seat

Sighing through all her works gave signs of woe, That all was lost.

I happen to have re-read the epic during the pandemic – the odd silent Spring felt an appropriate setting for musing on the beauty of the natural world and humanity’s complicated fouling up of everything.

The description of Adam’s horror at her deed, but his decision nevertheless to join her, more through fear of loneliness than love, is surprisingly psychologically convincing – then there is one final, less wholesome sex-scene, of defiant and desperate carnality. The last two books deal with the fall-out and offer a preview of human history. As Samuel Johnson said, no one wishes it were longer.

So, what draws me to the epic is a mix of its grand religious purpose and its dramatic, psychological and aesthetic aspects. I am a bit wary of critics who ignore the former, and claim that it nowadays has huge importance, in secular cultural terms.

On the other hand, there is an interesting story to be told about its political and cultural afterlife, for the epic was frequently cited by all sorts of modern thinkers and writers, who found secular revolutionary energy in it. This goes against Milton’s intentions, for it is Satan who defies authority. But maybe not entirely, for Milton was a revolutionary republican and opponent of established churches, in the English civil war.

In a recent book, What In Me Is Dark: The Revolutionary Life of Paradise Lost, Orlando Reade explores this tangled history, with mixed results. First, we hear about the American revolutionaries’ love of Milton. Then we hear about the English Romantics. It was Blake who came up with one of the soundbites of literary history: because Satan is depicted so engagingly, Milton ‘was

a true Poet and of the Devil’s party without knowing it.’ But Reade focuses on Wordsworth – in fact on Dorothy as much as William. Their siblinghood was a sort of fragile Eden. Then we are reminded that in Mary Shelley’s famous novel, the sad monster actually reads Paradise Lost and learns to resent its creator, sensing itself to be ‘both Adam and Satan.’

brief comments on the epic are negligible, as is Reade’s disapproving response.

When he tries to tie up his thoughts about the epic’s relevance, they are as paltry as fig-leaves: ‘it reminds us that it is only in the world and not in any fantasy that we can be happy.’ Hmm. If Milton saw Eden as a distracting fantasy realm that humans should

I happen to have re-read the epic during the pandemic – the odd silent Spring felt an appropriate setting for musing on the beauty of the natural world and humanity’s complicated fouling up of everything.

Much of the rest of the book is concerned with slavery and its legacy. We hear of the epic’s influence on the first chronicler of the Haitian revolution, then on the abolitionist movement, then on the original New Orleans carnival, then on Malcolm X and C.L.R. James. Reade is also concerned with female readings: we hear about George Eliot and Virginia Woolf (but neither says anything very interesting about Milton as far as I can see). And Hannah Arendt is also given a section, though it seems she made only one tiny mention of Milton.

Reade interleaves this cultural history with a lively summary of the poem itself. But there are one or two missteps. When Satan first spies them, he says, Adam and Eve’s relationship ‘is already fraught with insecurities. Even as Milton describes his patriarchal Eden, he shows its difficulties.’ No: their relationship before the Fall is perfect. Milton’s imagining of it might contain sexist assumptions but it is, according to the logic of the narrative, perfect, and to question this is a category error.

At one point he refers to a passage in Malcom X’s autobiography that ‘has often been mentioned by modern scholars of Milton, hoping to make Paradise Lost seem relevant.’ This is a bit rich. His approach to the reception of the epic is one-sidedly trendy. A section on Jordan Peterson is perhaps an attempt at balance, but Peterson’s

reject, then it was an odd decision to write such a long poem about it. Sorry to be old-school – but this is surely a safe space! – but it seems to me that Milton wrote an epic about the Fall because it is very central to Christianity. It is annoying when someone wokesplains the epic’s relevance, ignoring its abiding purpose.

John Milton

Seventy-three Miltons

St Paul’s Librarian, Hilary Cummings, curates the works of John Milton in the Kayton Library Rare Book Collection. She writes:

Our last Treasures evening celebrated the work of John Milton, and we gaily committed to displaying everything by him in our Rare Books collection. We were discomfited to realise that we had too much to display easily. The Rare Books collection includes 73 books by Milton, many of these are very early editions, spanning both his political writings and his famous poem. It also includes a tiny edition of Paradise Lost which is only three inches tall.

Areopagitica; A Speech of Mr John Milton for the Liberty of Unlicenc’d Printing, to the Parliament of England is our earliest work, a first edition pamphlet dating from 1644. This is Milton’s passionate defence of free speech written at a time of heavy

censorship by the Crown. It also includes a favourite comment on the value of books:

“a good Book is the precious life-blood of a master-spirit, embalmed and treasured up on purpose to a life beyond life”