STOKE STOKE

Winter..... switched on.

Winter..... switched on.

We’re not a company we’re a crew. A handful of people doing what we love, chasing stories that matter to us, and building something that feels honest.

Philip Hutchinson

Founder, Publisher & Editor-in-Chief

Photographer from Michigan Founder of Northern Territory Imaging I started Stoke because I felt like it needed to exist something that captures the energy we live in Snowboarding, motorsports, music, art, adrenaline, and storytelling all under one roof It’s not about trends It’s about people doing real things in a place we care about. I’m just doing my best to document it the way it deserves to be seen.

Yorg

Chief Hype Man & Founder of The Drop

Taylor Jepsen

Rider & Creative Contributor/Sales

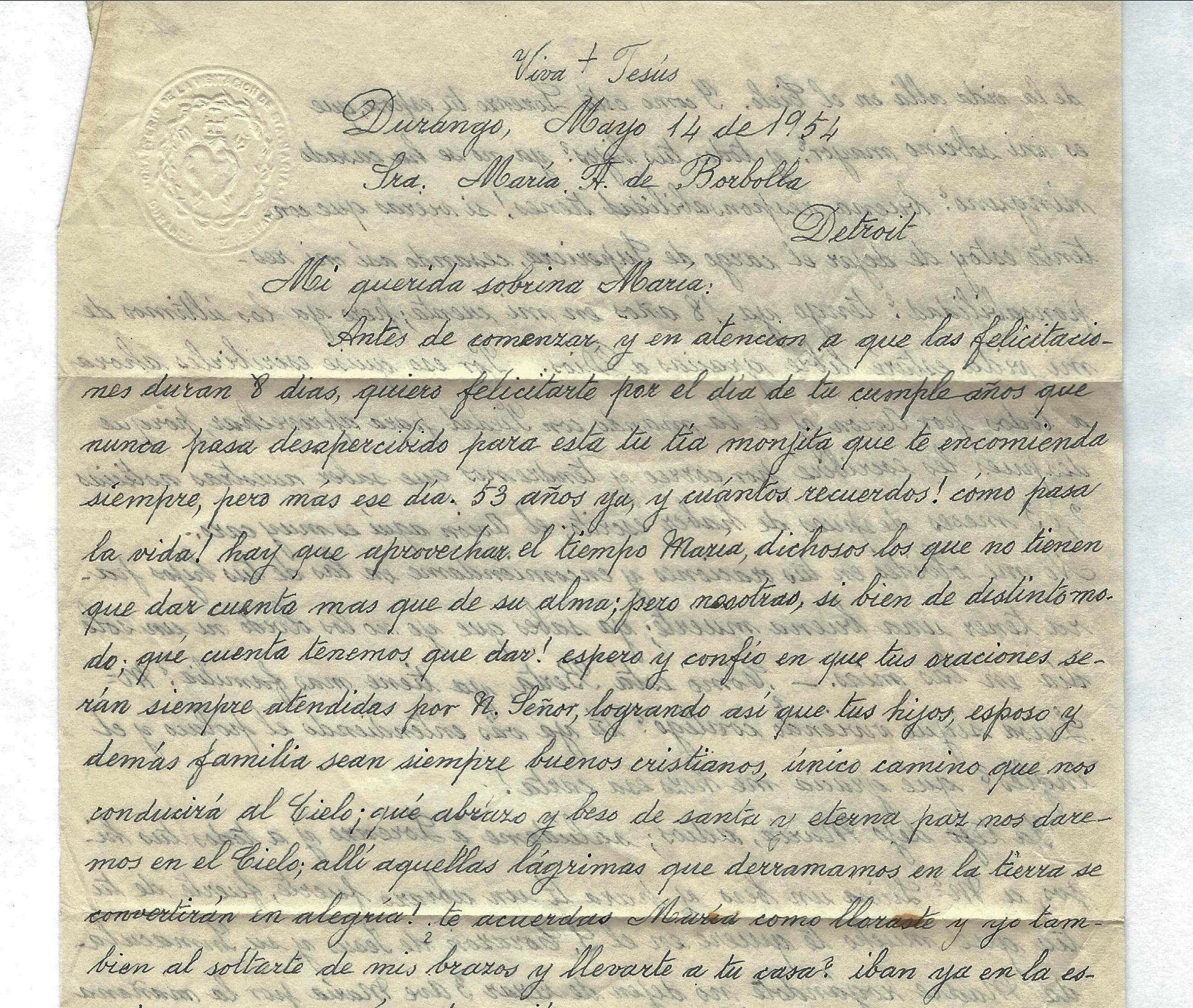

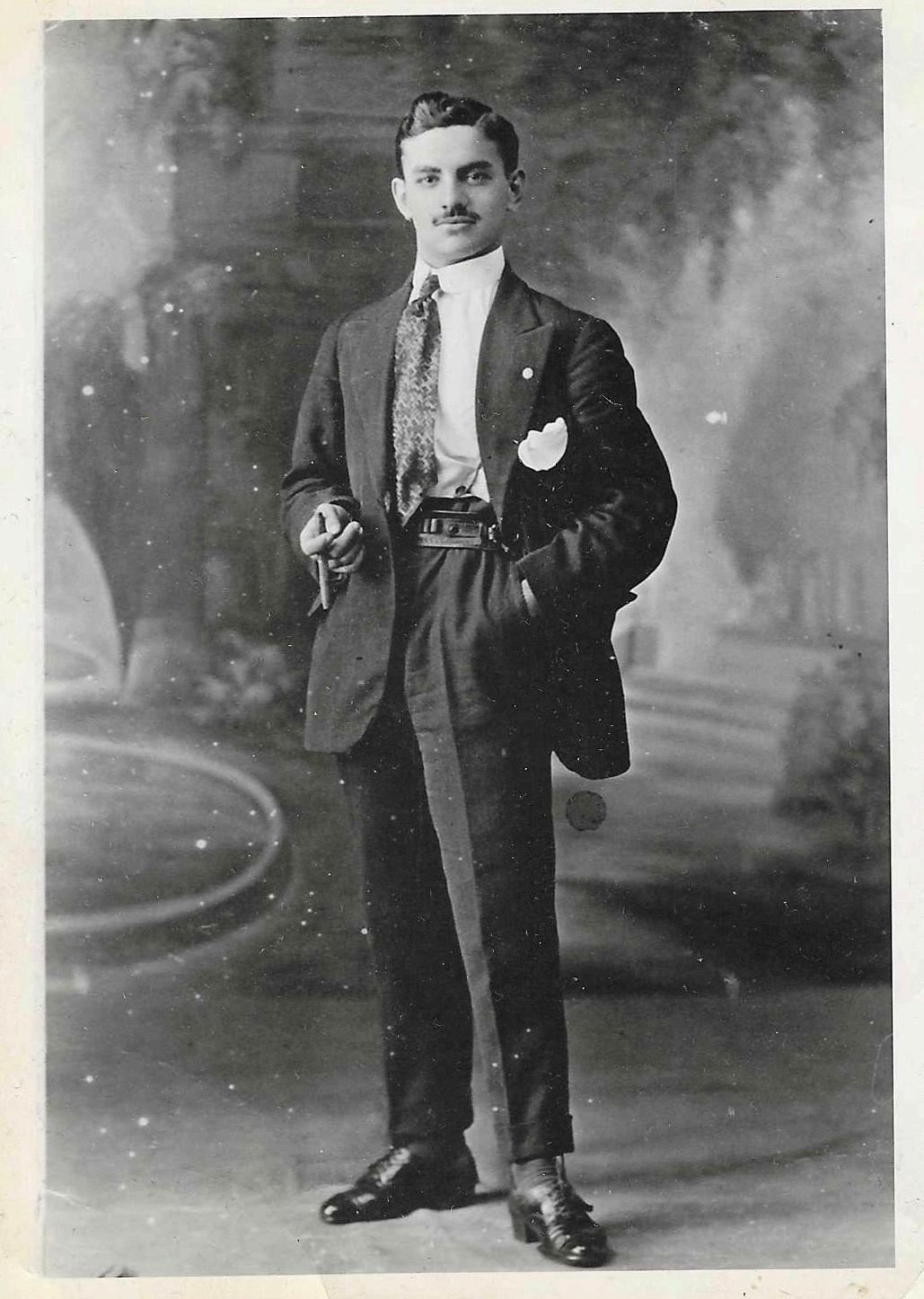

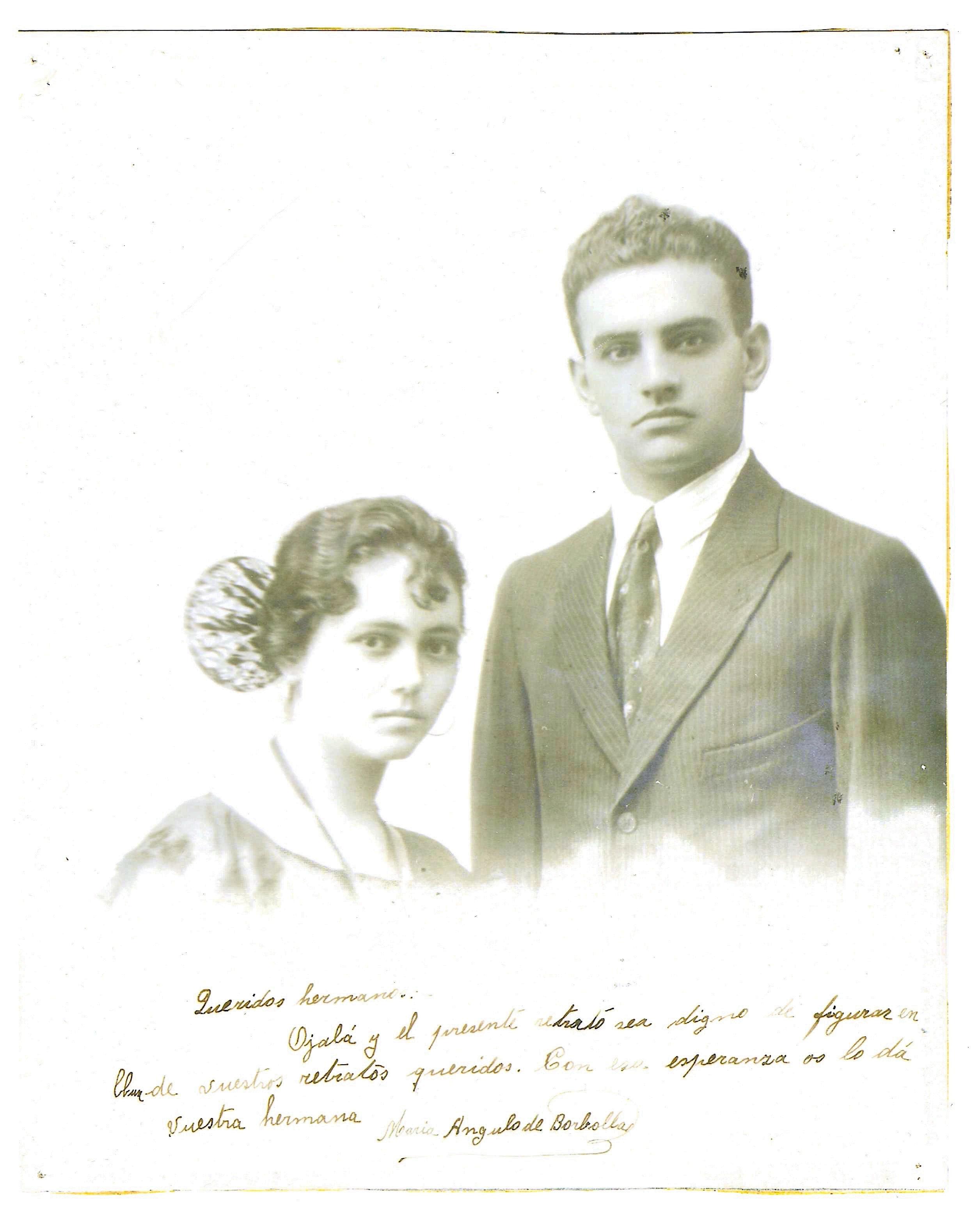

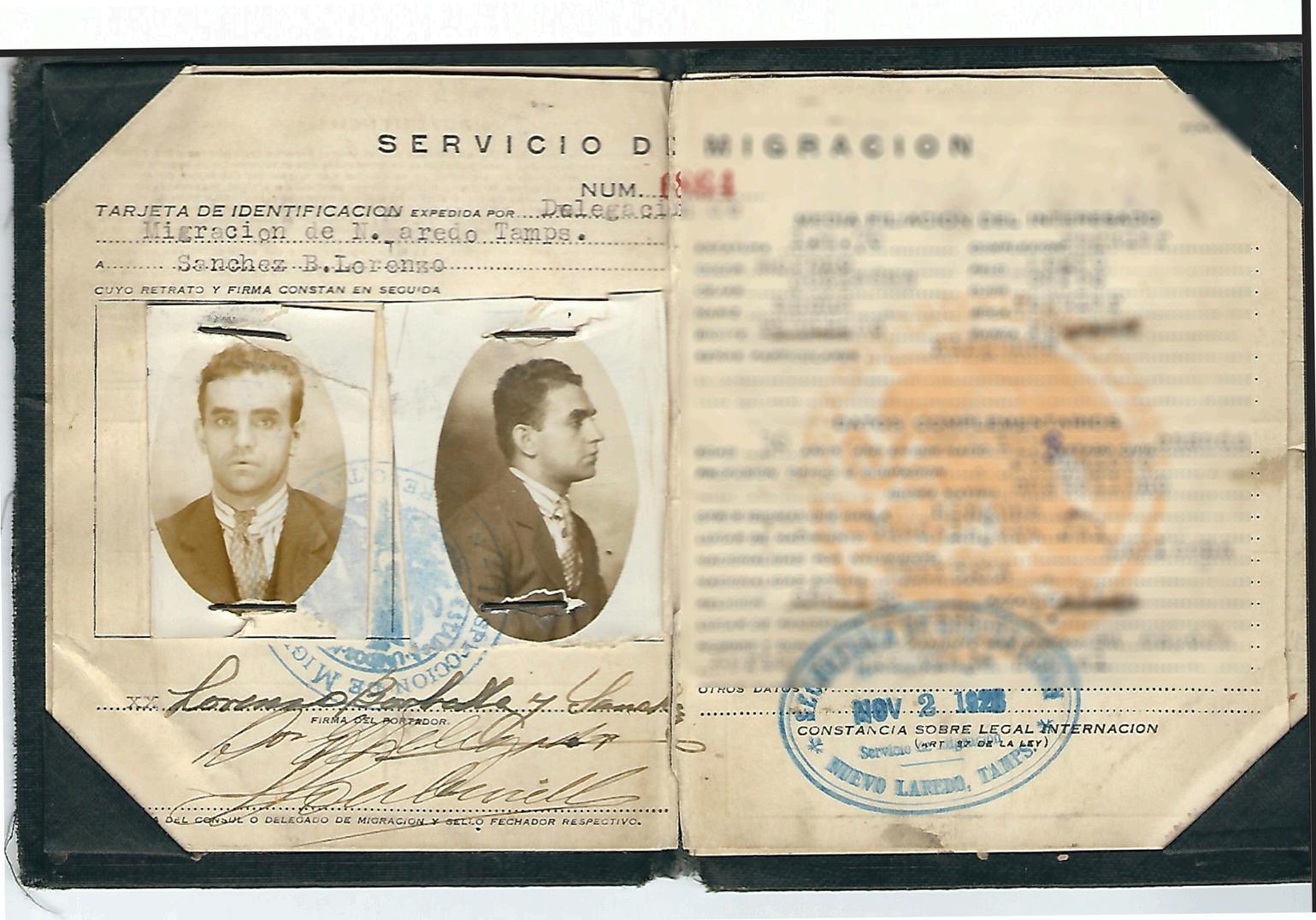

Vince (Borbolla) Kowalewicz Pen behind Lorenzo’s Journey,

AL KING

EMILY VELCHANSKY

KENNY “THE MISSILE” FORTON

STACY “IN THE SNOW” POKRYWKA

SKINNYBONES JEFFERSON (ROBROB)

THE MISSION

Stoke is about the people who bring fire to this state whether they’re carving lines in the Keweenaw, dropping sets in packed clubs, tuning rally cars in a pole barn, or sewing art into clothing that carries generations It’s for the ones who move differently and think louder It’s for the creators, the makers, and the brave

A Note on the Magazine

There’s no formula Each issue changes shape Some regulars will be there The Drop, Welcome to the Pigpen but nothing is guaranteed. The stories shift with the season, the inspiration, and the people who show up. Stoke is a platform for creatives in the adrenaline and art worlds who are pushing what’s possible and doing it in Michigan

The Bigger Picture

We’re just the core. The truth is, Stoke only happens because of the whole crew around us— photographers, riders, creatives, people who give their time and talent because they believe in the vision. We’re all part of the same spine—no one’s more important than anyone else.

• “The Only Thing to Do Is Do”

Mattie Armstrong on art, sobriety, and starting over at 50 a raw look at rebirth and creative purpose from one of Detroit’s most fearless voices.

• The Heart of the Hill

A conversation with Ben Doornbos of Nubs Nob — exploring community, tradition, and what makes this Northern Michigan resort the soul of Midwest skiing.

• Sugar, Leather, and a Michigan State

The Pig Pen sits down with Emerson Meyer the local legend behind Michigan Mittens and Waffle Cabin to talk hustle, homegrown flavor, and living the dream in the mitten.

• The Drop

Yorg shines the spotlight on SKYELEA Traverse City’s newest breakout superstar. A multi-instrumentalist and soul songstress redefining what Michigan music sounds like.

• Lorenzo’s Journey: Chapters 5 & 6

Vince Borbolla continues his serialized story tracing legacy, loss, and love through Detroit’s immigrant heart.

“The Only Thing to Do Is Do” — Detroit’s Mattie Armstrong on Art, Sobriety, and Starting Over at Fifty

By Vincent Kowalewicz, Stoke Magazine

In the basement of a Detroit house, beneath a laundry line and a stack of half-finished canvases, Mattie Armstrong is still chasing color The smell of acrylic and espresso hangs in the air Feist hums from an old stereo while the brush drags slow and deliberate across canvas

His story doesn’t start here It runs through the Marine Corps, two decades managing bars in Detroit, and the kind of darkness that nearly swallows a man What he found on the other side wasn’t redemption so much as work the kind that saves your life one brushstroke at a time

Vincent: Let’s start at the beginning the Marines, the bar years, and how it all led you here.

Mattie: ** It actually goes back Stuart Sutcliffe, their first bassist, who quit the band to b the Beatles to paint?* But that idea stuck with me.

After high school, my options es So I joined No regrets The Corps taught me discipline, pr vant I knew I wasn’t built for that

**Vincent: ** Let’s start at the beginning the Marines, the bar years, and how it all led you here

**Mattie: ** It actually goes back even farther to the Beatles. There was this movie about Stuart Sutcliffe, their first bassist, who quit the band to become a painter. I remember thinking, *how do you leave the Beatles to paint?* But that idea stuck with me.

After high school, my options were limited: work at an oil-change place or join the Marines. So I joined. No regrets. The Corps taught me discipline, pride, grit. But it also boxed you in cop, firefighter, civil servant. I knew I wasn’t built for that By my last year I was already dreaming of art school. When I got out, I dove in Art school became therapy After years of structure and silence, I wanted chaos color, freedom, people who thought differently It cracked something open in me

But the whole time I kept asking, *how do you actually make a living at this?* Everyone could paint, but nobody could pay rent

So I started managing a bar in Detroit Then bartending Suddenly I was making four to six hundred bucks a night that’s like selling a painting every shift. But the money wasn’t meaning. The bar taught me that. It showed me what eighty-hour weeks and a hollow soul feel like.

I got sober two years before I finally walked away I couldn’t handle the noise anymore inside or out I wanted to be kind, but I couldn’t be kind to myself in that place

After that, I worked for Live Nation, catering rock shows feeding crews, watching the chaos backstage Cooking felt like painting: mix, balance, improvise Then came Trader Joe’s good people, good pay, funny shirts It felt like breathing again

“Oh, I’ve been there. You finish a piece, post it online, and the silence hits hard.”

Then COVID hit Because of lung problems from my Marine days, I stayed home Down in my basement, I started painting every day I even found thirteen huge canvases in someone ’ s trash and dragged them home Just painted Every Day A buddy, Chris George, stopped by one afternoon His sister had just opened a gallery She came over, looked around, and said, “You’re doing this in your basement?” That was the moment. I was fifty years old when I said to myself, *if I don’t take a chance now, I never will.* That’s when I claimed it I’m an artist.

**Vincent: ** Any Detroit artists you’d love to collaborate with?

**Mattie: ** Michelle Tanguay I’d love to paint walls with her Robert Schefman, genius Liz Frankland her portraits kill me Jonathan Harris my hero in the city. There’s so much talent here; I’d work with any of them.

**Vincent: ** When you hit a creative block, what gets you through it?

**Mattie: ** Oh, I’ve been there. You finish a piece, post it online, and the silence hits hard. When that happens, I strip it back Just color Blending, layering, seeing how it lands No message, no masterpiece just paint That’s what brings the spark back

You don’t always have to paint for applause Sometimes you paint just to breathe

**Vincent: ** How do you know when a painting’s done?

**Mattie:** I don’t. I’ll swear it’s finished, then see it a week later and start adding again. Art’s alive; it keeps breathing.

Even the ones I’ve sold I’ll visit them and think, damn, I could’ve added more But that’s part of it They’re moments frozen mid-evolution

Most of my canvases are recycled old wood, discarded frames, whatever I find on the street

That’s Detroit, man Nothing’s wasted

**Vincent:** That’s beautiful

**Mattie:** Yeah, man You just keep doing Keep giving Energy given is energy received I’m grateful every single day I get to do this

Mattie Armstrong paints the way Detroit breathes — loud, soulful, and full of second chances. From the Marines to late-night barrooms to a quiet basement studio, his life proves that art doesn’t save you — it reveals who you already were all along.

**Vincent: ** That’s a hell of a journey What drives you now what’s the muse?

**Mattie: ** Kindness Love

When I first started painting seriously, it was rebellion anger at everything wrong in the world I wanted to fight through my art But sobriety changed that Now I just want connection I paint things people recognize Detroit landmarks, faces, moments. I want someone to look and say, *I know that place.* That connection is everything. That’s the real revolution.

**Vincent:** What’s the first piece you remember being truly proud of?

**Mattie: ** Black Panther. I painted it during COVID, right in the middle of the Black Lives Matter protests I wanted to show support but didn’t know how I’m a white guy from Grosse Pointe

When I finished it, I sat down and cried I’d never cried from joy before only from pain or regret That one broke me open Gratitude poured out

It ended up selling to a brain surgeon in Grosse Pointe Shores a Black Panther hanging in a mansion on Lakeshore Drive That irony wasn’t lost on me, but that’s the power of art: it connects across any line

**Vincent:** Paint me a picture of your studio life what’s going on down there while you work?

**Mattie: ** Coffee’s the fuel Food, not so much Music always I’ll play Feist, Townes Van Zandt stuff that hits the soul But once I start, I disappear I fall into the colors I’ll spend days on one cloud until it feels alive

**Vincent: ** If you could hang one of your pieces anywhere in Detroit, where would it go?

**Mattie: ** The DIA. That’s the dream someone walking by and saying, “That’s a Mattie Armstrong.” But if it never happens, that’s fine. I’m grateful just to be painting. I live in the day. If today says paint, I paint. If it says rest, I rest. The only thing to do is do

By STOKE Magazine

Your paragraph text

In northern Michigan, winter doesn’t just arrive it settles in And for generations of skiers and riders, Nub’s Nob in Harbor Springs has been the place that defines what winter here feels like It’s a ski area built on longevity, craftsmanship, and a fiercely loyal local community the kind of place where your liftie might have been here twenty years, and your neighbor’s kid is now teaching lessons on the same hill their parents grew up skiing.

At the center of it all is Ben Doornbos, the general manager who’s spent the better part of two decades helping keep Nub’s true to itself: family-run, skierfocused, and proudly independent We sat down before opening day to talk snow, community, and what makes this hill often called “the best snow in the Midwest” a place like no other

STOKE:

So there’s this rhythm to the week, right? Saturdays with visitors, Sundays for locals?

Doornbos:

Exactly. Saturdays tend to draw travelers people up for the weekend, maybe their first time skiing here. Sundays, though, that’s what we call “Locals’ Day” That’s when you see the familiar faces our race-league folks, ski-academy kids, families who have been here for generations

There’s a great flow to it You get the energy of visitors on the weekend, then the home-hill feeling when Sunday rolls around It’s part of what keeps the vibe balanced

STOKE:

Let’s talk about the glades they’re a huge part of Nub’s identity, especially after last year ’ s storms What’s happening there this season?

Doornbos:

The glades have always been special They really took off in the ’90s when people started craving that off-trail experience. Our former GM, Jim Bartlett, was ahead of his time recognizing that.

After last winter’s ice storm, though, the glades took a beating tree tops snapped, branches dropped, debris piled up So our team has spent a lot of time cleaning, trimming, and clearing We’ve had crews in there with weed-whips, dragging out sticks, cutting brush six to eight inches above the ground so we can open those runs early, even on low snow

Everyone talks about “Midwest’s Best Snow” I used to think that was just marketing but after shooting here for three years, I can see it What’s behind that claim?

Doornbos:

(Laughs) It’s not just a slogan, I promise Everything at Nub’s rises and falls on snow quality That’s our foundation

We build our own snow guns in-house. They’re simple but effective and we know how to make them work for our conditions. Our snowmaking crew has decades of experience. Making snow is easy; making it right is the art.

The trick is knowing when to turn the guns off. When the temps climb above 28 degrees, the snow gets wet, heavy, and turns to ice A lot of places just keep running guns because it “looks” like they’re making snow But that’s how you ruin a base for the season

Our crew ’ s focus is precision make good snow, then maintain it. Some days that means grooming twice, or delaying an opening until the surface sets up right. Whatever it takes to make sure skiers get the best conditions possible for that day.

We’re not rushing to open new glades right now The goal is maintenance A glade only matters if it skis well So for anyone coming back this year expect some fresh lines, some new looks The terrain will feel different, in a good way

STOKE:

That’s a perfect way to sum up Nub’s simple, genuine, and all about the snow Thanks for sitting down with us, Ben Here’s to another winter in Harbor Springs

Doornbos:

Thanks, Philip Here’s to a great season ahead

:

A lot of people talk about Nub’s as a locals’ hill but it doesn’t have that “locals only” edge you find at some resorts. What makes it so welcoming?

Ben Doornbos:

That’s a great observation I started here in 2008, and now I’m in my seventh or eighth year as general manager though I’d have to look up exactly when that started! (laughs) But that kind of longevity isn’t unusual here

Most of our year-round team has been here ten, twenty, even thirty years What’s really unique is that it’s the same with our guests We have second, third, even fourth-generation passholders. They come back year after year. That longevity creates ownership. People don’t just ski here they belong here. It’s part of who they are. But that sense of ownership doesn’t turn into gatekeeping The attitude at Nub’s has always been: “Welcome to the family Grab your skis”

STOKE:

Nub’s has stayed focused on skiing not hotels, not condos, not zip lines. In a time when a lot of places are chasing “resort” dollars, why stick to being a ski area?

Doornbos:

That’s one of our guiding principles We’re a ski area, not a resort Everything we do starts with one question: does it make the skiing experience better? We’ve talked about lodging, fine dining, tubing hills, even summer operations. But for now, those things feel like distractions. Our resources go into snow, lifts, food service, and people.

We’ve also tried to make it affordable and family-friendly — things like our “brownbagger” area with outlets for crockpots so families can bring their own food It’s small stuff, but it matters If you come here, you’re here to ski or ride That simplicity is what keeps it authentic — and it’s why people keep coming back, generation after generation.

“EVERY WINTER, THE HILL RESETS., YOU CAN OPEN NEW TERRAIN,” BEN SAID, “BUT IF YOU DON’T CARE FOR IT, IT DOESN’T MATTER. THE REAL BEAUTY OF THE GLADES IS IN THE MAINTENANCE IN KEEPING THEM ALIVE SO THEY CAN KEEP GIVING BACK.”

From Wall Street floors to waffle steam and rope-tow scars, Emerson Meyer has built two things that scream winter in Northern Michigan: the Waffle Cabin culture that perfumes the base areas and a tougher-thanyour-average glove brand born for our mitten state Philip Hutchinson sat down and caught up with the Petoskey lifer behind Waffle Cabin (Boyne Mountain, The Highlands, Crystal) and the Michigan Mitten Company to talk origin stories, durability, and why smell, wind, and bottlenecks matter more than you think

“THESE

STOKE: You talk about waffle ops like a race tech—wind, flow, bottlenecks

EMERSON: (Laughs) It’s real. If it’s an east wind at Crystal, we’re up ~25% because the smell rides the chair line all day. Put a cabin in a bottleneck and sales jump. Summer is different above 60 degrees, the aroma doesn’t carry, so we go visual: waffle nuggets, s’mores waffle, ice cream, whipped cream. In winter, it’s dough proofing schedules, -20° freezers so yeast stays asleep, managing 220-volt irons and sugar burn-off cycles It’s not “make a batter and go” You probably cook a thousand waffles before I set you loose solo

STOKE: Give us the short origin story how does a Petoskey kid end up building waffle culture at ski hills and launching a glove brand?

EMERSON MEYER: Born and raised in Petoskey Grew up in the family hardware store Skied Nubs, did the local sports thing I went to Western Michigan, then landed a finance job on the trading floors in New York NYSE, Amex, later a hedge fund in Tribeca My boss was a big US Ski Team supporter, so we’d take one big trip out West every year, plus quick hits to upstate New York and Vermont. That’s where I met Waffle Cabin. I thought, “Gimmick.” Then I ate one. From then on it was a $20 bill: one waffle at rope drop, one before après

STOKE: Where are people finding the mittens/gloves?

EMERSON: Focus is retail—40–50 Michigan locations is the target this season—plus the site (michiganmitten co) You’ll see resort shops and select hardwares. We do custom stamps Nub’s pairs, Walloon pairs, Petoskey pairs so locals can rep their hill or town. That’s how we compete with big-box and billion-dollar holding companies: service, speed, and local identity.

STOKE: Rope-tow kids and lift ops at Bohemia put them through hell and loved them Is that your bullseye?

EMERSON: Totally Patrol, lift ops, snowmakers, snowfarmers if you keep Michigan winter spinning, I want the product in your hands and I want your feedback. We’ve already made three major design changes from real-world use I’m not precious I’ll pivot if it makes them better

Small Shop, Big Heart

In a back room lit by work lamps, Emerson and his wife press logos into leather with a brass die that hits 400 degrees Each stamp takes time one press at a time, one glove at a time. The smell of scorched hide mixes with the hum of classic rock and the hiss of the space heater There’s nothing mass-produced about it You can still feel the human touch in every pair

STOKE: What flipped it from obsession to “I’m bringing this home”?

EMERSON: Timing The founders divorced, franchising opened up, and I was one of the first in the door with interest It took years to get Boyne Mountain on board we matched aesthetics down to cedar shakes and stain. First year was scrappy but good enough to keep the hamster wheel turning. We added a mobile Waffle Wagon, opened Crystal the next season, and now we ’ re a few winters into The Highlands Three cabins plus the mobile Ten winters of waffles at Boyne this season we’ll celebrate that with giveaways, including a pair of Shaggy’s

THE FIRST PROTOTYPES LOOKED ROUGH — SEAMS CROOKED, EDGES SCORCHED FROM THE HEAT GUN — BUT THEY HELD. THEY DIDN’T TEAR. THEY DIDN’T QUIT. THAT WAS THE START OF THE MICHIGAN MITTEN COMPANY — A BRAND NOT BORN FOR STYLE, BUT SURVIVAL.

Ask any rope-tow rat what kills gloves. It’s friction — that grinding steel cable that eats through cheap leather before Christmas. Big-box brands keep their padding where it’s pretty, not where it matters. Emerson flipped the script.

Full-grain pigskin. Reinforcement stitched all the way up the palm to the fingertips.

Every piece snow-sealed, stamped hot with brass, and tested until the seams turn black with rope dust.

“These aren’t souvenirs,” he says. “They’re tools.”

own Skyelea is turning heads as one of Michigan’s most dynamic new voices a singer, songwriter, and multi-instrumentalist with a sound that feels both timeless and entirely her own Rooted in soulful honesty and sharpened through years of performance, she’s part of a new wave of artists redefining what “ up north” creativity sounds like From jazzlaced melodies to stripped-down acoustic sessions, Skyelea carries Northern Michigan’s rhythm in her bones In this conversation with The Drop, she opens up about her roots, her inspirations, and the pulse behind her music.

Yorg: What inspired you to pursue music?

Skyelea: My grandparents, mom, and dad all are performers. I grew up taking every single dance class offered and joined every choir I could I’ve always loved being on stage, but it wasn’t until I started studying Audio Technology in college that I realized just how much I love to record and share my original music

: What

Skyelea: One of my biggest challenges as a local artist is pacing my performances and not oversaturating the market In a smaller scene like Traverse City, playing too often can make it harder to sell tickets, but being selective also means fewer opportunities to perform Working at The Alluvion adds another layer I love the connections and community it brings, but sometimes people recognize me more in my staff role than as an artist Finding that balance between supporting the scene and building my own identity within it is an ongoing dance

Yorg: How does Traverse City influence your sound?

Skyelea: Traverse City probably influences my sound in more ways than I even realize Sometimes when I hear hints of jazz and bluegrass in my songs I think to myself, “ yep, that’s the TC scene influencing my creativity,” and I’m never mad at it

Yorg: How do you balance music with everyday life?

Skyelea: Music truly is my everyday life. The balance comes naturally.

Yorg: What’s your favorite local venue to perform at?

Skyelea: My favorite local venue to perform at is definitely The Alluvion, and I’m not just saying that because I work there! Even before I was on the staff, I recognized how intentional and special the space was

Yorg: How do you connect with your audience?

Skyelea: During live shows I have some interactive elements that are always really fun, and through social media I try to just keep it real I feel like my audience appreciates and understands the power behind exchanging authentic energy I do my best to honor that

Yorg: How do you handle criticism?

Skyelea: I’m thankful for my background in dance it’s made receiving critiques normal for me I deal with constructive criticism by actively listening and deciding whether or not it aligns with my artistic vision If it does, I apply it, and if not, I simply say thank you and keep moving forward

Yorg: What role does social media play in your career?

Skyelea: The role social media plays in my life is hard to describe for me it almost feels like an extension of my art and everything I create. I do my best to share everything, but there’s always the little voice saying I could be doing more (and I should, and I’m working on it!).

Yorg: Have you collaborated with other artists from Traverse City?

Skyelea: I’ve collaborated with many other artists in Traverse City, and I’m eternally grateful for them Specifically, Jimmy Olson (piano man and MPC extraordinaire) and Sam Briggs (touring sound engineer) have been the most pivotal to my career so far

Yorg: What’s the most memorable performance you ’ ve had?

Skyelea: Right now my most memorable performance was definitely my debut gig in Detroit at Aretha’s Jazz Café I had locals Tariq Gardner (drums) and Houston Patton (sax) back me up and it was literally magic

Yorg: How do you promote your music?

Skyelea: I mostly use social media for promotion. I also use public playlists and my local radio stations!

Yorg: What’s your songwriting process like?

Skyelea: My songwriting process is almost never the same, but most of the time I start with my guitar and a chord progression

Yorg: What advice would you give to aspiring musicians?

Skyelea: If you want to play shows, watch live shows! Go to concerts at a variety of levels (stadiums, bars, venues, etc ) It’s also so valuable to be involved in your scene as a fan before you start asking for collabs and shows Make your presence be known as a supporter, and a lot of time people will be excited to return the favor

Yorg: What’s your dream venue to play in?

Skyelea: Radio City Music Hall!

Yorg: How do you stay motivated in the industry?

Skyelea: I’m really fortunate to feel like I have to create like I have music that I just need to get out. Even when I feel unmotivated, I still pick up the guitar because if I don’t, I’m doing a disservice to myself.

Yorg: What themes do you explore in your music?

Skyelea: I talk a lot about water, my mom, and telling the truth I didn’t even realize it until recently, but they’re definitely recurring themes in my music

Yorg: How important is community support for artists?

Skyelea: Community is, in my opinion, the most important and valuable support an artist could have I’m so thankful for Traverse City and the way it’s lifted me up on this wild journey, and I wish every artist was as lucky as I am

Yorg: What’s your vision for your music career?

Skyelea: Full-time touring and recording artist

Yorg: How do you define success in the music industry?

Skyelea: I think if you like the music you ’ re making, you ’ re doing it right

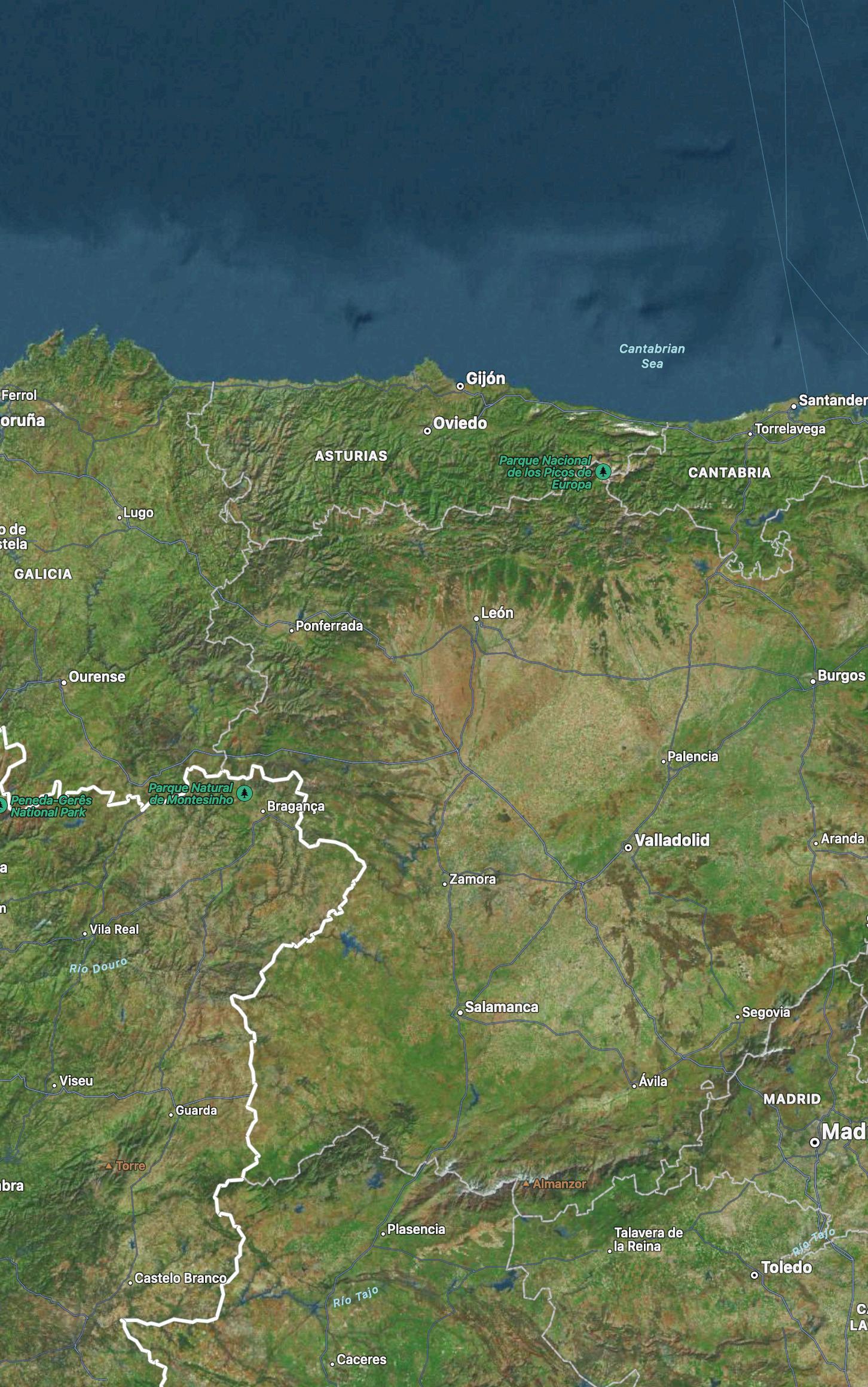

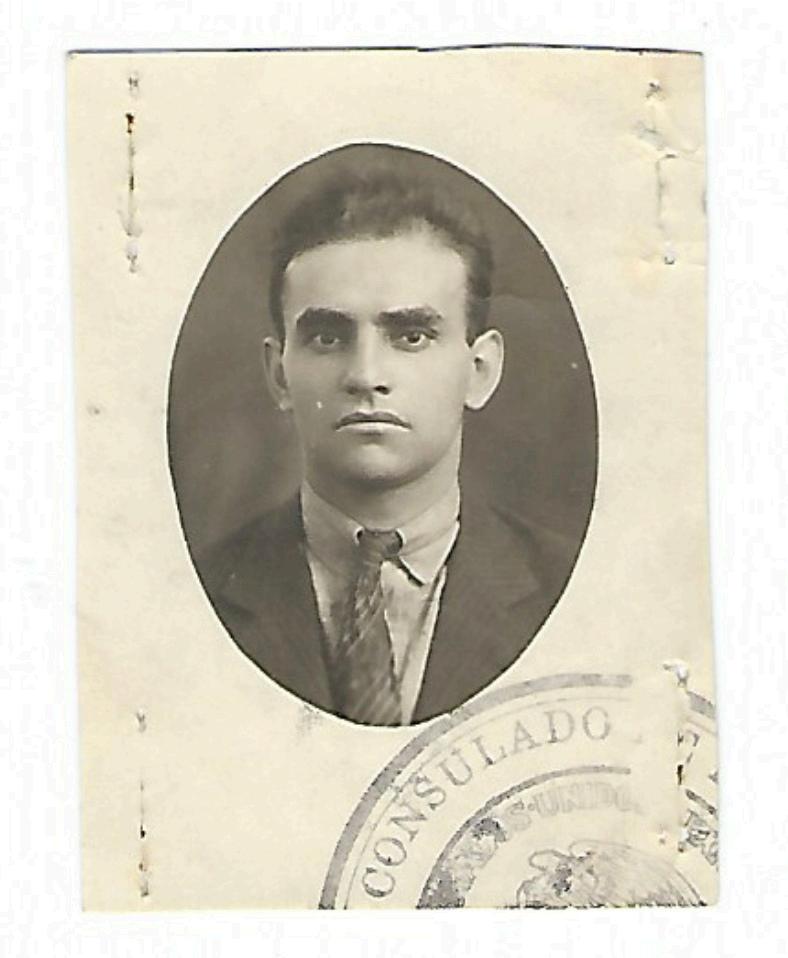

BY VINCE BORBOLLA

I did not look back, for fear my dear mother might see the tears I fought to hide

The road to Unquera was quiet, save for the soft thud of my boots and the cry of unseen gulls overhead I walked alone, with the wind at my back and the sea ahead an ocean I had never crossed, toward a world I did not know In my chest, hope and fear wrestled like brothers

The ship was no grand liner, no polished vessel of promise. It was sturdy, blackbellied, and stank of salt and coal. Men shouted in sharp Castilian:

“¡Rápido, muchacho!” "Quickly, boy!"

“¡Cuidado con esa carga!” "Careful with that load!"

I watched them, feeling smaller than I had in years

A sailor checked my papers, nodded once, and waved me forward I stepped across the gangplank as though crossing a threshold into something beyond my imagining

In the hold, hammocks swung low and close I stowed my trunk beneath one and clutched the medal my mother had given me Her words echoed:

“Vete con Dios, hijo mío” "Go with God, my son "

I did not sleep that first night The ship groaned and heaved beneath me, and I lay awake, listening to the creak of rope and the hush of prayers in the dark Some wept Others whispered stories of Havana of jobs in sugar mills, fortunes made and lost, land so hot your skin smoked by midday

By dawn, the coast of Spain had disappeared, and with it, the life I had known

The days at sea blurred together, marked only by meals of dry bread and thin broth, and by the changing moods of the ocean

We slept shoulder to shoulder in the dim belly of the ship, swinging in hammocks like laundry on a line The air was thick ripe with sweat, seawater, and the slow sickness that crept into men ’ s stomachs Some grew pale and silent Others clung to their rosaries and murmured prayers through cracked lips

I kept to myself I read from my Bible, though the words swam at times, blurred by fatigue or the lurch of the waves I thought of my former life often the scent of the fields after rain, the rhythm of the church bells, the heavy silence that settled in our home after my father passed

There were boys not much older than I who had already seen the world’s darker corners They spoke of men who vanished in the cane fields, of overseers with cruel eyes, of heat so fierce it burned through your boots But they also spoke of wages real money and of a chance to become something more than poor

One man, a bricklayer from León, told stories every night He claimed Havana was full of marble palaces and women in silk “It’s no Spain,” he said, “but if you keep your head down and your hands moving, you’ll eat better than you ever have.”

At times I believed him.

At others, I simply stared at the waves and tried to believe in anything at all

After nearly two weeks at sea, Havana rose out of the mist like a mirage white facades glowing in the sun, towers and domes catching the light, palm trees swaying as if to welcome us But there was no grand welcome, only the bark of orders and the rush of bodies pushing toward the dock

The heat struck like a blow It was not the warmth of a Spanish summer, but a thick, pressing force that wrapped around the lungs and soaked the skin My shirt clung to me before I even reached the end of the gangplank

Customs was chaos Men shouted in Castilian and Cuban Spanish, lifting sacks, checking names against smeared ledgers I stood with my trunk beside me, trying not to look lost, though I felt it with every breath

My cousin Manuel found me just before I feared he wouldn’t He wore a straw hat, sweat darkening his collar, and when he called my name, it took me a moment to place the voice He grinned, clapped me on the shoulder, and shoved a little cigar into my mouth

The very first cigar I ever smoked

“Bienvenido a Cuba, primo,” he said “Aquí se trabaja duro, pero se come ” "Welcome to Cuba, cousin Here we work hard but we eat"

I coughed on the smoke, but he only laughed and led me into the heat of Havana I followed him through the streets, wide-eyed at the sheer life of the city carts rattling over cobblestones, women selling fruit beneath striped awnings, children darting barefoot through narrow alleys Music drifted from open windows, and everywhere, there was color: yellow walls, red flowers, bright fabrics hanging from balconies

But beneath it all, I felt the weight of distance I was far from home, and everything familiar had been left behind on the other side of the sea

Manuel led me through a maze of side streets until we reached a modest boarding house wedged between a tailor shop and a bakery. The air smelled of yeast and tobacco. Inside, the walls were stained with old humidity, and ceiling fans creaked overhead like tired birds A woman named Estela ran the place She gave me a narrow bed, a chipped washbasin, and a plate of rice with beans so spicy they made my eyes water

“You’ll get used to it,” Manuel said, smirking

The next morning, he woke me before the sun “Come on, ” he said. “Time to earn your keep.”

We walked for nearly an hour until the buildings thinned and the air turned even heavier. He brought me to a sugar mill el ingenio where men were already lined up, dark with sweat and soot. The foreman barely glanced at me before putting a machete in my hand and pointing to the fields

The work was brutal

We cut cane in rows that seemed to stretch into eternity The sun was relentless, the blades sharp, the rhythm punishing: swing, cut, haul, stack My hands blistered by midday By sundown, I could barely lift my arms And still, I went back the next day, and the next

At night, I collapsed into my bed, too tired to eat, too sore to speak But something in me hardened not bitterness, not yet but a kind of resolve I had come to Cuba to survive I would do more than that One evening, as I soaked my hands in cold water, Manuel handed me another cigar “This one ’ s earned,” he said And this time, I smoked it all the way through Weeks passed The ache in my muscles dulled into something familiar, almost expected I learned how to pace myself, how to wrap my palms to keep the blisters from splitting open. I stopped flinching at the heat. I stopped thinking about comfort. There wasn’t time for it. The men I worked with came from all over Andalucía, Extremadura, León, even a few native Cubans. Most were older. Some had been cutting cane for a decade. They spoke with thick accents and smoked between cuts, their shirts soaked through by noon A few took to me kindly One, Ramón, showed me how to sharpen my blade properly and told me to drink salt water to keep from fainting “The strong aren't the ones who endure the most they're the ones who get up the next day” I never forgot that By the end of the month, my pay came in a small envelope, folded and creased It was more money than I’d ever held in my hand I counted it twice, then tucked it beneath my mattress It wasn’t much But it was mine And for the first time since leaving home, I began to believe I might build something here

Something real

The days blurred together sugarcane and sweat, sun and sores My body adjusted before my mind did The pain dulled into a rhythm, and I found myself moving through it like a cog in a great, churning machine The mill consumed us all: our time, our strength, our names Manuel was quiet most days, but I came to know the meaning behind each grunt and nod He watched over me, in his own way If I faltered, he steadied me If I lagged, he barked me forward But he never asked questions, and he never offered comfort That wasn’t the way of things

The other men were a mix Cubans, Haitians, a few like me from Spain. They spoke little and worked hard. At night, we’d collapse in the same barracks, breathing the same hot air, sharing a silence forged by exhaustion.

I wrote letters to my mother in my head. I imagined her reading them in the quiet of our kitchen, her hands folded on the table, my father's empty chair beside her I wondered if she would recognize me now leaner, darker, quieter

One evening, I counted a few coins in my hand tarnished and warm from my pocket They weren’t much, but they were mine I stared at them a long time, thinking of all they had cost me

That night I bought a bar of soap, a small tin of tobacco, and a pouch of beans Manuel nodded in approval when he saw “You’re learning,” he said I slept better that night

The routine settled in Wake before the sun March to the fields Cut until my arms felt hollow Back to the mill for hauling, stacking, sorting Return in silence, wash with cold water, sleep in sweat

Manuel never missed a day Neither did I I watched the way he moved economical, precise He knew how to make each swing count, how to save his energy for when it mattered I copied him as best I could.

The meals were simple rice when we were lucky, beans more often, a bit of boiled plantain. Meat was rare. Once, a man traded a week’s wages for a fish, but it had gone bad by the time he cooked it. We ate it anyway.

Most of us sent what little we could spare back home I asked Manuel how “There’s a clerk at the post,” he said “Every few weeks he goes into town Give him your envelope, a coin or two, and pray it gets there”

So I wrote a letter Just a short one I didn’t say much only that I was alive, working, and thinking of her I folded it carefully and tucked it into a shirt pocket until I had enough coins to send it

That small act writing, sealing it, handing it off felt heavier than the sacks of cane I carried

A few weeks later, I received a reply

The envelope was smudged and creased, but my name was still clear across the front Inside was a letter from my mother, written in her careful hand She told me the harvest in Villanueva had been poor, that Father’s absence was still felt at Mass, and that she prayed for me every day

She didn’t say she missed me but I read it between every line

I read that letter so many times I could recite it from memory I kept it folded inside my shirt, close to my chest, and when the days felt too long or the work too cruel, I would touch it through the fabric, just to remind myself of why I had come

The men began to treat me differently Not warmly, not exactly but with a kind of respect I kept up, I didn’t complain, and I did my share. That was all anyone asked. That, and to stay out of trouble.

Manuel started talking more short stories about his village, his time in Santiago, the brother he hadn’t seen in years He never asked about my past, but I told him some things anyway He listened without reacting, just gave a short nod, then went back to his cigar

The work didn’t get easier But I got stronger When Sunday came, work slowed Some of the men played dominoes Others washed their shirts in buckets or mended holes in their shoes I went to the chapel once a small shack with a rusted cross nailed above the door. The benches were splintered, but I sat for a while, not to pray exactly, but to breathe.

I thought about my father. About how he would handle my work with relative ease. In my heart, I know he would be proud of my hard work

The days began to pass with more certainty I knew what to expect from the sun, the work, the men And I began to feel something I hadn’t felt since I left Villanueva a sense of control, however small My body obeyed me now My coin purse, though light, no longer sat empty I had routine, and in routine, I found a kind of peace One evening, Manuel and I sat outside the barracks, smoking the scraps of rolled tobacco we’d saved The sky was streaked orange and purple, the kind of sky you only see after a long, punishing day

“You ever think of going back?” I asked him He let out a dry laugh “Back where? There’s nothing left back there but dust”

I didn’t answer I thought of home my mother at the window, the narrow streets, the sound of the church bell on Sundays There were moments when it all felt like another life.

“ You?” he asked.

I took a long drag from my smoke before answering. “Sometimes. But I don’t know if I’d still fit there.” He nodded slowly, as if he understood. “That feeling doesn’t go away You stay too long in one place, you start to vanish in another”

We sat in silence after that The night air was thick, but cooler than the day had been The stars above us blinked through a haze of cane smoke and dust For a moment, I felt still like I was finally standing on solid ground, even if it wasn’t the one I was born to

When the bell rang the next morning, I rose without thinking My legs carried me forward, my hands reached for the blade I didn’t need to be told what came next The weight of sugar was mine now on my back, in my hands, in my bones

And for the first time since stepping off the ship, I didn’t feel lost

I took a long drag from my smoke before answering “Sometimes But I don’t know if I’d still fit there” He nodded slowly, as if he understood “That feeling doesn’t go away. You stay too long in one place, you start to vanish in another.”

We sat in silence after that The night air was thick, but cooler than the day had been The stars above us blinked through a haze of cane smoke and dust For a moment, I felt still like I was finally standing on solid ground, even if it wasn’t the one I was born to

When the bell rang the next morning, I rose without thinking My legs carried me forward, my hands reached for the blade I didn’t need to be told what came next The weight of sugar was mine now on my back, in my hands, in my bones

And for the first time since stepping off the ship, I didn’t feel lost

THANKS FOR RIDING WITH US.

STOKE has never been about being polished — it’s about being true. Every issue gets tighter, every story hits harder, because of the people who step up to bring it. Some have already carried the torch, others are just about to.

September’s around the corner, and with it, a whole new crew keeping STOKE burning in Michigan.

A LITTLE HINT OF WHATS TO COME.....