NOTES FROM THE EDITORS

The avant-garde is a transgression between societal norms and the strange, abnormal, and absurd. It is shocking, disturbing, and potentially enlightening and being explored in all walks of life, societies, and ideologies. It leaves the consumer walking away in an altered state, changing the way they view an issue or topic, potentially forever. In this issue our columnists have explored avant-garde aspects and pursuits of sectors from art to politics to religion, showing what avant-garde means to them, in all manners of the term. We hope that these articles leave you with a newfound appreciation for what you may have previously described as odd or peculiar, but now label ‘the avant-garde’.

Fenella Rawlins - LVI

Nothing screams radical authenticity more than the avant-garde. Yes, it defies convention through its inherently subversive nature and its unapologetic impetus to change. But avant-garde isn’t just relentless disruption and condemnation of the status quo; it is what we replace it with that truly counts. For me, the avant-garde is a bold proposition. Far from being unbound by precedent, it is in constant dialogue with it— deconstructing, reconstructing, in an act of reimagination steeped in social meaning. As these articles engage with our shared history and culture, they also ask implicit questions that drive us towards reflection and reconfiguration. I suggest you approach these articles with an open mind and an open heart, remembering always to read between the lines.

Cherie Ng - LVI

When fevered crowds tore through the concrete wall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and the world held its breath and watched it play out on television screens, the soon-to-be seismic shift in global politics was evident to all. As the East Germans found themselves touching down in the West, geographically and ideologically, they felt a bliss unlike any other: their mobility was reinstated, they had been liberated from decades of oppressive rule. To the political commentators in Washington, no barrier seemed insurmountable anymore after having taken on Soviet authoritarianism…and won. A new era was hailed, and it was to be a golden era of liberal democracy. Democracy had prevailed over dictatorship, capitalism over communism, globalisation over protectionism. Right?

The Cold War era was marked by ideological rifts exactly like the ones listed above: the two superpowers, placing themselves in diametric opposition to each other, presented an extraordinarily simple narrative for the public to follow.

This bipolarity in international order, now observable between China and the US, has since been contested; ‘middle powers’ are proving to be the new architects of the world order, and they are teasing the idea of being multi-aligned. Japan, historically one of the US’ closest allies in the East, is part of a regional trade pact that includes China while Tokyo plays an important defense role in the revived Quadrilateral Security Dialogue with the United States, India, and Australia to counter Chinese aggression. In addition to building economic ties with China, countries across the Middle East have also pursued deeper economic relationships with India, retained strong trade partnerships with the European Union, and sought to revitalize their lagging ties with Turkey. Whilst some may interpret this as countries being less willing to nail their flags to the mast, it is a strategic endeavour. They want the US as a primary security guarantor whilst being unable to resist the attractions of Chinese investment. Hence, the renewed bipolar dynamic is not as clearcut as it used to be, and the polarities themselves less assuredly defined.

BEYOND THE LEFT-

The horseshoe theory asserts that the far-left and the far-right, rather than being at opposite ends of a linear spectrum, in fact closely resemble each other.

In his 2006 book, ‘Where Did the Party Go?’, political scientist Jeff Taylor wrote: "It may be more useful to think of the Left and the Right as two components of populism, with elitism residing in the Center”. Josef Joffe, a visiting fellow at the American think tank the Hoover institution, added, “Will globalisation survive the gloom? The creeping revolt against globalization actually preceded the Crash of '08. Everywhere in the West, populism began to show its angry face at middecade…As the iron is bent backwards, the two extremes almost touch.”

Left v.s. right underwent polarisation during the Cold War, as implicit within the dehumanisation of the enemy was to consider those with the slightest ideological sympathies as traitors. The us vs. them mentality now reemerges, albeit under a different and more subtle guise. When the new millennium dawned, and the US placed itself at the forefront of the globalisation effort, left and right acquired new meanings: progressivism and conservatism. ‘Left’ became associated with progressive social policies, multiculturalism, and identity politics, whilst ‘right’ was linked to traditionalism, nationalism, and sometimes, cultural preservationism.

The new left favours globalisation and is more optimistic about multilateral cooperation; whereas the new right remains sceptical—and it is here that populism has risen inexorably. Nothing fans the flames of us v.s. them quite like populism, a movement that claims to champion the common person, usually by favourable contrast with a real or perceived elite or establishment. Think Donald Trump, Nigel Farage, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, France’s Marine Le Pen. Their appeal is strongest to those who feel left behind by the liberal left, their manufacturing jobs outsourced to other countries and their communities in decline, thus eroding their social esteem. Research has shown that districts in the United States most affected by import competition from China tend to remove moderate members of Congress and elect more extreme ones, especially on the right. Support for the ‘Leave’ option in the UK referendum on European Union membership was stronger in areas hit hardest by trade. More so than ever, the political status quo seems to be on shaky ground: in 2024, as a staggering 60+ countries went to the polls, there was a long line of losses from incumbent governments who would’ve historically had the upper hand, opening the door instead for right-wing populist parties that seem to be skyrocketing in popularity.

RIGHT PARADIGM

As many muse over the prospects of a multipolar world order asserting itself in the 21st century, it is intriguing how deeply attached we are to the dichotomies of the Cold War era. Whilst there is general agreement that the left-right paradigm is obsolete, political theorists are ready to swap it out with other contrasting principles: open vs. closed, the elite vs. the people etcetera.

On both the international and domestic fronts, world leaders and politicians seem even less inclined to cooperation and compromise. As countries withdraw from multilateral agreements and become increasingly hostile towards international peacekeeping bodies for their supposed overreach, geopolitical tensions begin to corrode globalisation itself. An increasingly fragmented world order may not hold its own against another global crisis of the likes of COVID-19. Is there a way to lower the temperature of political discourse and bridge the ideological divide? Or are we being ushered into a second Cold War, with more players and even higher stakes?

Unfortunately, the answer is no less convoluted than the conflict itself. In 1989, American political scientist Francis Fukuyama published his landmark essay “The End of History?”, arguing that ideological evolution had come to an end with the fall of the Soviet Union, and that liberal democracy was the final form of government for all nations. He was evidently misguided and has since revised his position. In “Liberalism and Its Discontents”, published in 2022, he retains his defence of liberalism but urges moderation, rebuilding trust in government institutions, and a consolidation of national identity, with the aim of fostering greater social cohesion. It is a long and taxing to-do list. But he then goes on to write, “At the heart of the liberal project is an assumption about human equality: that when you strip away…. accumulated cultural baggage that each one of us carries, there is an underlying moral core that all human beings share and can recognize in one another.”

We can only hope that he is right this time around.

By Cherie Ng

Making Waves: The avant-garde Mosque that divided Tehran

Whether or not to credit something with the title of ‘avant-garde’ can be an interesting conundrum, in a world so keenly focused on moving forward. To be radical is eeting, a moment of controversy swiftly absorbed into the surge of the newest innovation, the next generation. This begs the question as to what it takes to be de ned as avant-garde at all. To be progressive, to be ahead of your time. A visionary caught in the midst of revolution, on the cusp of a breaking boundary. This is certainly applicable to the architects of the Vali-e-Asr mosque in Tehran, Iran, which was credited with such a title upon completion in 2018.

The Vali-e-Asr mosque encountered controversy from its earliest stages of creation. Proposed construction was met with outrage amongst religious hardliners, who were adamant that such a building could not possibly be used for worship, since it failed to meet the structural requirements of an Islamic Mosque. They feared that the building’s architectural ambiguity insinuated a secular takeover seeping into the Islamic republic. The ght over construction escalated to such an extent that funding was cut and one of the architects, Reza Daneshmir, had to appear before a parliamentary committee.

Located in one of the most culturally

sensitive places in Tehran, where Revolution Street meets the famous Vali-e-Asr junction, it neighbours the renowned City Theatre of Tehran. This itself is an architectural masterpiece and prominent staple of Tehran’s landscape, built before the revolution of 1979. It was therefore paramount to the construction of the mosque, that it should sit in harmony with the City Theatre and acknowledge both its cultural and religious signi cance, as a symbol of the future.

The mosque takes reference from the cyclical form of the neighbouring theatre, in its curved spine that stretches from ground to sky. Sleek and striking, the rst thing to compel the viewer to the Vali-e-Asr is that it does not resemble a traditional mosque. Conventionally, mosques have an exterior comprising of intricate minarets and domes. The outline is conspicuous and easily identi able, the imposing structure intending to embody the majesty of Allah.

However, the architects at Fluid Motion, Catherine Spiridonoff and Reza Daneshmir, forewent the norm in favour of unobtrusive grey undulations. The roof slopes elegantly skywards, inspiring worship and re ection. The window slits, reminiscent of a staircase to heaven, guide the onlooker’s gaze and allow sunlight to stream into the halls within. The architects defended their vision against attacks from hardliners, arguing that the Qu’ran does not dictate that there must be domes or minarets, and in fact the convex on the roof can be seen as a form of ‘open dome’. Acknowledgements to the mosque’s heritage and faith are imbuedthroughout, starting with the owing slope of the roof that nods to the graceful script of Arabic calligraphy.

The Vali-e-Asr Mosque in Tehran, Iran

Waves are a distinct feature of Fluid Motion’s style, evident in the philosophy by which they create: “We are living in a world of forces and waves, in progress in all inner and outer dimensions. To be sensitive to these waves and to demonstrate them, requires the invention and utilization of systems that are capable of upholding them in exible and cohesive structures without loss of energy. Architecture has the potential to detect, direct and record these waves within a speci c time related process and yield a space which articulates the association between large scale issues of urban space, universe and history in a broader setting.” (Fluid Motion). Their unique perspective of movement, form and rhythm emerges as a building which feels almost alive, dynamic yet settled in its surroundings. It carries its identity with both humility and pride, simultaneously acknowledging the rich history of the religion it stands for while looking ahead to the future of progression.

These themes of time and place are essential to the nature of the Islamic Mosque. The strict timing of prayer concedes a exibility of space (no speci c place is required for prayer to Allah) and a harmony of juxtaposing expectation that is remarkable to this religion. It is this accommodation of the oxymoron that makes the Vali-e-Asr so incredibly unique. A building with an equal standing in heritage and exploration, in subtlety and prominence, in the well-trodden path and the avant-garde one.

The Vali-e-Asr joins the movement of postmodern architecture that engages actively in the political and social structures of its time. According to the architects, “our biggest source was the Qur’an itself”. Inspiration is taken from the

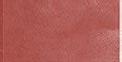

MAAT (Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology) in Lisbon, which was designed by the award-winning British architect Amanda Levete. This incredible feat refers to the rhythm of the wave, intending to emulate the motion of the river Tagus which ows alongside it, thus uniting the cosmopolitan city with the dynamic forces of nature. Likewise, the Vali-e-Asr pays homage to the British-Iraqi architect, Dame Zaha Hadid, who was dubbed ‘Queen of the Curve’, for her trailblazing structural mastery that took the architectural world by storm in the late 20th century. Hadid herself grew up in Iraq, surrounded by Muslim and Arab in uences, which are manifested in the buildings she created throughout her life. She became the rst woman to win the most coveted prize in her eld, the Pritzker Architecture Prize.

Despite the controversy surrounding Tehran’s most avant-garde mosque, it

The MAAT museum in Lisbon

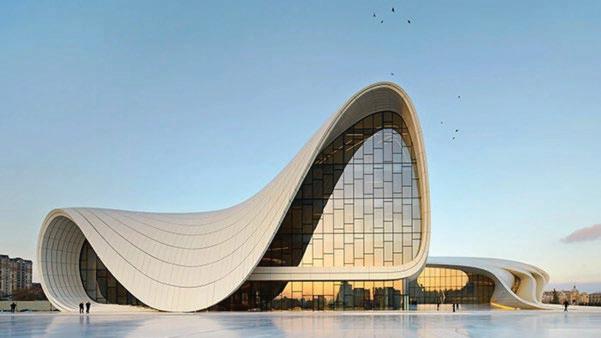

Zaha Hadid, Heydar Aliyev Centre in Azerbajan

gained tremendous acclaim from the architectural world. Notably, in 2018 it won both the Middle East Architect Award in Dubai, the Architecture Master Prize in California, and came highly commended in the World Architecture Festival in Amsterdam. In 2019, it was shortlisted for the Abdullatif Al Fozan Award for Mosque Architecture, Saudi Arabia.

Controversy aside, it is undeniable that the Vali-e-Asr mosque has earned its title of extraordinary. Seamlessly gliding between the worlds of the well-trodden

and the groundbreaking, it has a distinct harmony of personality, a perfect equilibrium between pride in identity and humility to its fellows. It is a reflection, therefore, of the ingenuity of the minds behind this creation, to have realised the avant-garde in both intention and production.

They are, quite spectacularly, making waves.

By Luisa Gallwey

The Vali-e-Asr Mosque in Tehran, Iran

FEMME FATALE

MERITABLE OR MISOGYNISTIC? MERITABLE OR MISOGYNISTIC?

BY FENELLA RAWLINS BY FENELLA RAWLINS

Aeschylus's ‘Oresteia’ (5th century BC), ‘Promising Young Woman’ (2020), ‘Macbeth’ (1623), ‘Dracula’ (1897) and ‘Jennifer’s Body’ (2009). What do they all have in common? They all revolve around the femme-fatale. The persistence of this character throughout history shows her cultural relevance time and time again, and how she represents societal anxieties of each period in which she appears. Throughout this article, I will explore the concept of the femme-fatale and whether this revolutionary trope is meritable or misogynistic. Feminists throughout history have debated whether this trope is liberating through its introduction of female empowerment and using the patriarchy’s stereotypes for personal gain, or if it is a tool of the patriarchy to oppress women and reduce them to sexist stereotypes.

Literally translating to the ‘deadly woman’, the ‘femme fatale’ is a blanket term that involves a dark, manipulative, sexual, dangerous, independent being. She’s been wronged by men and thus seeks her revenge on his entire sex by leveraging her femininity against them, either through underestimation or sexual enticement. Thedebate of who ‘counts’ as a femme fatale is never-ending, so I have narrowed my selection down to characters I personally believe best embody this trope.

In Ancient Greek mythology, ‘femme fatale’ characters such as Clytemnestra and Medusa are displayed as monstrous, hysterical savages whose role is to be killed and overcome by men for the ‘greater good’. I believe they constitute as ‘femme fatale’ due to their dark, sexual, powerful, and deadly characteristics. These characters were male authors’ way of perpetuating the stereotype that women can’t be powerful without being ugly, mad, and isolated, and associating strong females with their inevitable downfall at the hands of a strong, respected male. These Greek women have also been portrayed in art as well as literature. John Collier’s ‘Clytemnestra’ depicts her after murdering her husband

Agamemnon, who had sacrificed their youngest daughter, Iphigenia in return for good winds to sail to Troy. In this painting, Clytemnestra is depicted with a haunting expression as she stands proudly in a victorious pose, wielding a bloody axe tainted with the blood of her husband. Clytemnestra embodies the ‘femme fatale’ as she kills Agamemnon while he’s in the bath, a vulnerable and sensual place for the acclaimed war hero to ultimately meet his demise. Clytemnestra met her death shortly after by the hands of her son, Orestes, the parricide subverting all sense of natural order and the status quo. Therefore, the ‘femme fatale’ dying through this brutal and unnatural manner reinforces the notion that a woman in power is brutal and unnatural.

Medusa usually evokes less sympathy. She was a beautiful youth who was seduced and overpowered by Poseidon, the sea god, in a temple to Athena. Athena, upon hearing this, cursed Medusa’s beautiful looks and caused snakes to grow in place of her beautiful locks that would set whoever looked at her in stone. This made it impossible for her to be physically or emotionally intimate with anyone ever again, desensitizing her into the villainy history has condemned her to. Her victims were usually men, as a means of revenge against Poseidon. Her decapitation at the hands of Perseus led to the birth of her two children, Pegasus and Chrysaor, through the spilling of her blood. This occasion, supposedly a woman’s crowning moment in Greek society, doubled as Medea’s death, conditioning Greek women into believing that a similar fate would befall them should they lust for power. I believe that Medusa was not a barbarian female monster, but a woman unfairly punished for having sexual experiences, epitomising the patriarchal view that women must not desire but be desired.

The 2009 film, ‘Jennifer’s Body’, starring Megan Fox and Amanda Seyfried, has its titular character become a demonic maneater after being sacrificed to the devil. From this point

onwards, she must seduce and eat men to survive. Megan Fox was a model, ‘sex symbol’, and every teenage boy’s fantasy, and the film attracted an eager male audience; however, she was depicted with blood and black liquid drowning her once ‘desirable’ features as she fed on the flesh of men just like them. Jennifer weaponises her sexuality to isolate men and prey on men, which some feminist critics argue merely perpetuates the status quo, as she does so in low waisted jeans and small strappy tops. It suggests that women must, at the outset, be attractive to gain power, meaning that the existence of the ‘femme fatale’ character is contingent upon patriarchal permission. However, there is an argument to be made that this inversion of gender roles, of the woman being the predator rather than the prey, is empowering. As male characters are thrust into the ‘damsel in distress’ role, there is redistribution and redefinition of what it means to be a woman in media.

Though there are certainly limitations to the power of the ‘femme fatale’ in correcting the patriarchy, I believe that it has, on the whole, done more good for women than bad. From the outset, the trope has clearly identified itself women, and during the war when only women were in the audience, these films were all the rage. Today, ‘Jennifer’s Body’ is considered a cult classic. There is something in these films that compels women to come see them time and time again; this onscreen externalisation and projection of their ‘female rage’ evidently serves as a form of catharsis. They may not be able to do exactly as she does, but they can revel in her success and vindictiveness. Even if it is radically subversive, and even if it crosses the line at times, the resonance of the ‘femme fatale’ makes for an enduring phenomenon.

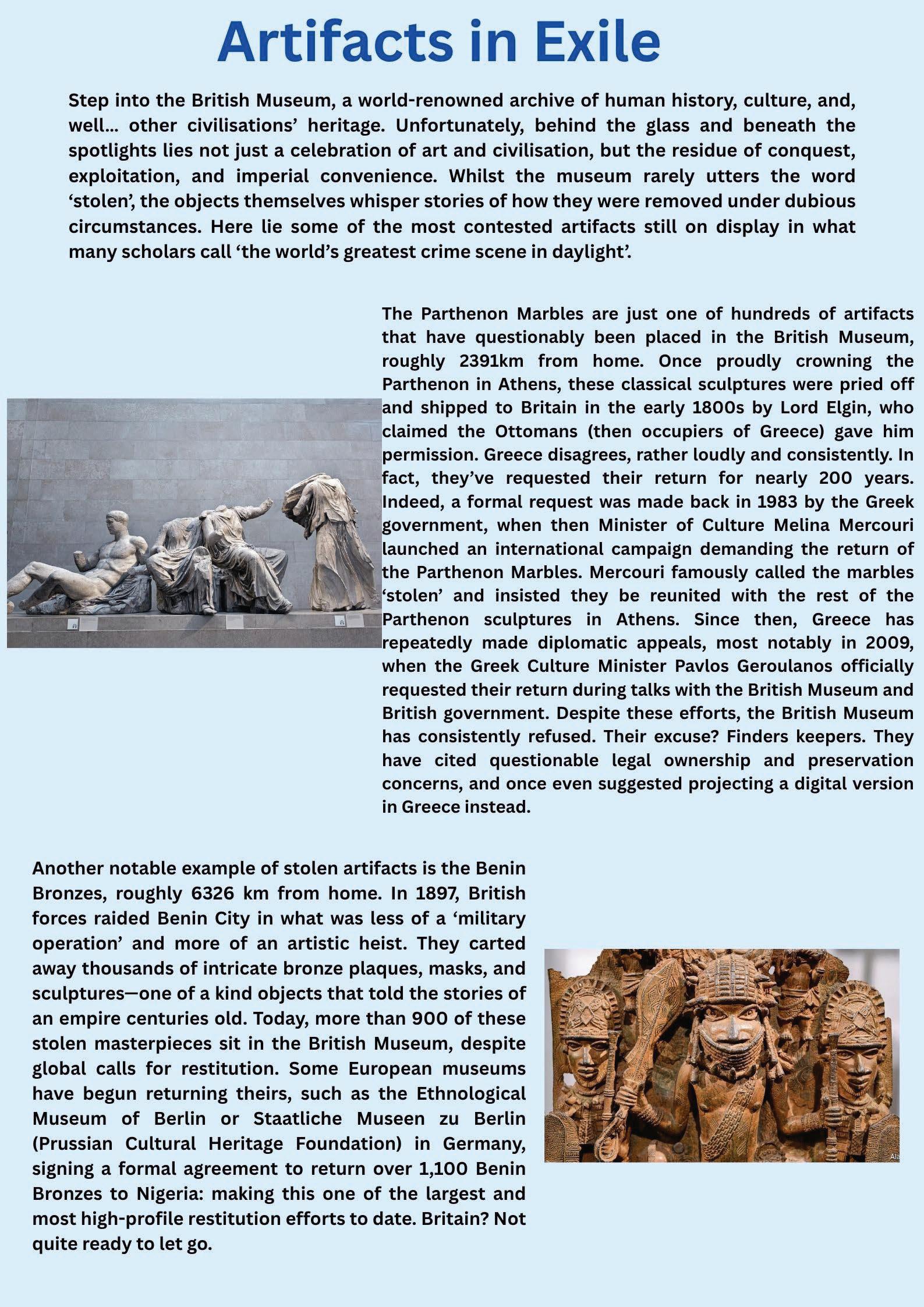

Ukrainian Artists and Writers: A Legacy of Resilience and Identity

By Victoria Stefak

The establishment of the Russian Empire in 1721 and later Soviet rule in 1917, compromised Ukraine’s cultural identity for decades. Literary legends in the early 19th century, to creatives in the Avant Garde renaissance of the late 19th century, and further, were rebranded, renamed and reclaimed as Russian. Now, over 80 years later, Ukraine is once again on the frontlines, fighting not just for its territorial integrity, but for its identity.

In the 1800’s, the Russian Empire imposed restrictions on Ukrainian language and culture, notably through the Valuev Circular and Ems Ukaz. The Circular quoted from the Kiev Censorship Committee that "a separate Little Russian language never existed, does not exist, and shall not exist, and the tongue used by commoners (i.e. Ukrainian) is nothing but Russian corrupted by the influence of Poland." These decrees banned Ukrainian publications and performances, in an attempt to abate Ukraine’s cultural presence. Taras Schevchenko, a famous Ukrainian poet, was born in Kiev in 1841. He utilised his works to express Ukrainian opinions and critique Russian’s oppression. His poems are a foundation for Ukrainian education, with children across the country learning about his life and works.

Another notable writer in the 19th century is Mykola Hohol, more often referred to as Nikolai Gogol, who was born in Poltava, Ukraine, in 1809. Although he is widely recognised as a Russian writer, there is compelling evidence contrary to this assumption. In a letter dated April 20, 1834, Hohol investigates the use of particular words used by Maksymovych, a scholar, in both Russian and Ukrainian. He refers to the latter as “our language,” clearly expressing Ukrainian language as his and Maskymovych’ native tongue. His works often include Ukrainian characters and folklores, particularly within his collections of ‘Evenings on a Farm’ near Dikanka and Mirgorod. These writings describe Ukrainian life with Ukrainian phrases and expressions used throughout. I personally recommend one of his short stories, The Overcoat. The supernatural story contains a mix of dark humour and satire, and its perspective on the dehumanising effects of bureaucracy made it a fascinating read.

Despite these restrictions, Ukraine flourished in an avant-garde movement in the 1890's and 1930's in response to a broader European trend in art, literature and drama. Artists like Alexandra Exter and Kazimir Malevich set aside traditional concepts and presented unconventional and unique ideas and works.

Alexandra Exter was born in Poland in 1882 and died in Paris in 1949 where she spent most of her life. Although she is claimed as a Russian artist, her art was often tied with her Ukrainian identity through the introduction of vibrant colours to monochrome Cubism paintings which brought Ukrainian folk art into her works. Cubism is a concept which was of a significant

influence in the avant-garde renaissance and illustrates a unique way to depict objects without using shading or other traditional means.

Kazimir Malevich was born in 1879 in Kiev to a Polish family. In his life, he created Suprematism, a concept where art creates its own world, and is not fixed to a singular, traditional depiction. The priority in such work is to focus on expressing basic, human emotions in a simple colour palette. His most famous painting is the Black Square which embodies minimalism and is a total purification of colour and form. Although he is often misinterpreted as Russian, he identified himself as Ukrainian and Polish. In 1930, he was arrested under suspicion of spying for Poland and was threatened to be killed. He spent three months in prison where he was tortured by Bolsheviks, a far-left group led by Vladimir Lenin, in order to gain information. Russian art critic, Irina Vakar, was allowed access to his criminal file in which it was noted that Malevich declared himself as Ukrainian.

After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, the opportunity to take back Ukraine’s identity arose. Many artists and writers, such as Oksana Mas, Serhiy Szhadan and Yuri Andrukhovych, carry the torch of Ukraine’s legacy and help bring Ukrainian art and literature into the modern world and the global spotlight. With each new creation, Ukrainians honour their past and shape a future where Ukraine’s voice is heard.

Danit Peleg and the Revolution of 3D-Printed Fashion -

By Cordelia Dwyer

In a world stitched together by tradition and tangled in fast fashion’s fraying seams, Danit Peleg burst onto the runway like a digital phoenix from a printer bed. Her claim to fame? Creating the world’s first 3D-printed fashion collection from the comfort of her own home. No ateliers, no sewing machines humming late into the night, just some desktop printers, a healthy disrespect for the status quo, and a vision bold enough to be called avant-garde.

Peleg didn’t just design clothes—she printed them. Layer by meticulous layer, like a couture croissant or onion, her collection emerged not from fabric bolts but from reels of flexible filament. The material of choice was Fila Flex, a surprisingly wearable thermoplastic polyurethane that behaves more like soft rubber than the stiff Lego-esque plastic most people imagine when they hear ‘3D printing.’

In 2015, for her graduate project at Shenkar College of Engineering and Design, Peleg unveiled five fully 3Dprinted looks: jaw-dropping, stylish, and entirely wearable. Vogue and Wired raised their collective eyebrows. The fashion world had been revolutionised.

Peleg didn’t stop there. She turned her work into an opensource movement, inviting the world to tinker, remix, and reimagine the very process of making clothes. Her studio’s mission is as radical as her designs: to democratise fashion production, decentralise manufacturing, and utterly disrupt how we think about clothing.

And disrupt it must. The fashion industry is famously fickle but also environmentally catastrophic. It’s the secondlargest consumer of water globally and is responsible for a sobering percentage of global carbon emissions. Enter 3D printing: a method that produces zero waste, uses recyclable materials, and allows on-demand, made-tomeasure garments that eschew mass production’s gluttonous overreach. It’s the fashion equivalent of farmto-table: cleaner, leaner, and infinitely more bespoke.

Yet 3D-printed fashion has struggled to strut its way out of the conceptual and into the closet. For years, it existed as haute tech: a novelty more at home in galleries than on sidewalks. Designers like Iris van Herpen turned it into wearable sculpture, exquisite and unapproachable. Meanwhile, Peleg took a different route: grounded, practical, and uniquely, printable. She asked not only what could be made, but who could make it. Spoiler: it’s you. All you need is a computer, a printer, and some pluck.

This shift, this turning of the power dial from Paris to personal, is the beating heart of what makes Peleg’s work so innovative. It’s not just about materials and machines; it’s about reclaiming the creation of our clothes. In an era when individuality is algorithmically flattened and trends flicker and vanish, 3D-printed fashion offers permanence with personalisation. Why buy off the rack when you can download, tweak, and print your next outfit at home? It’s cyberpunk meets sewing bee: a sartorial utopia as imagined by Ada Lovelace and Marie Kondo on a good day.

The avant-garde, by its very definition, pushes forward, probing the limits of what’s possible. It doesn’t always have to wear neon or scream for attention. Sometimes, it whispers through innovation. Peleg’s work is precisely that kind of quiet revolution. It seduces rather than shouts, inviting us to rethink not just our closets, but our entire relationship with clothing.

Of course, there are growing pains. The technology still has limitations in speed, comfort, and variety. Don’t expect to download a cozy cashmere jumper just yet. But as materials science advances and printers become faster and more accessible, the idea of a “digital wardrobe” where you choose, customize, and fabricate your outfit in a matter of hours, feels less like science fiction and more like next season’s must-have.

So where do we go from here? Perhaps the better question is: where do you go from here? Because the power dynamic is shifting. Fashion is no longer a top-down command; it’s becoming a bottom-up conversation. And Danit Peleg is one of the voices leading that dialogue, not with bombast, but with innovation, elegance, and a printer whirring softly in the background.

1970s oftheGarde AvantFeminist 0s 1970s oftheGarde AvantFeminist s

The 2017 exhibition ‘Feminist avant-garde of the 1970s: Works from the Verbund Collection’ was displayed in London at the Photographer’s Gallery. Featuring the work of 48 female artists from around the world and more than 150 major works, it explored the innovative works and techniques of the Feminist Art movement of the 70’s. The exhibition featured a range of mediums but focused on performance pieces, collages, photographs and film. The collection examined how during the 70’s the feminist movement became increasingly prominent in public life. The slowly growing openness of the public contributed to breakthroughs not only on these matters but also to the way artists could dissect them. The exhibition aimed to increase the representation and awareness of the revolutionary 70’s feminist art movement.

These new innovative techniques matched the contemporary social activism. The sixties and seventies ushered in a new era of social activism: second wave feminism. Second wave feminists had seen that the legislative advances made had not gone far enough and a gaping chasm of inequality remained. The second wave wanted societal change and believed that legislation would no longer be sufficient to make adequate progress. This approach was progressive at the time, and the innovative approach of second wave feminists is reflected in the avant-garde methods feminist artists used. The female body became an increasingly popular medium to explore bodily autonomy and freedom. A famous example of this is Carolee Schneemann’s 1975 performance piece, ‘Interior Scroll’ in whichafter reading from her book she pulled a scroll, which contained criticism of her work, from her vagina. Another innovative work was Ewa Partum’s ‘Change’, which is featured in the exhibit. Partum and a makeup artist aged half of her body into a much older version of herself. In doing this, Partum explored society’s sexist view on aging women. These works, and many more contributed to the innovation of the feminist art movement of the seventies.

The second wave is arguably when the Feminist Art Movement began. Others believes it roots go back earlier than the 1960s,with artists such as Louise Bourgeois producing art focused on the female experience as early as the 1940s. Regardless, it was during the 60’s and 70’s that the Feminist Art Movement came into its own. In New York, the movement focused on equal representation in art galleries. Female artists campaigned against galleries, such as the Whitney, who showed very few female artists. These protests had a significant impact as they forced galleries to confront the inequality. The Whitney displayed 13% more female artists (10% to 23% from 1969 to 1970). However, these inequities were not completely eradicated and were once again questioned in the third wave when in 1989 the Guerrilla Girls questioned ‘Do Women Have to be Naked to Get Into the Met Museum?’ after they discovered that ‘less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art Sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female’.

However, the exhibition has been criticised for having a very Eurocentric view, which almost entirely excludes works from women of colour. Whilst the second wave of feminism was overly dominated by white women who largely ignored the experiences of women of colour , I would argue that it is rather deceptive to substantially neglect to include the important contributions that these women made. For example, the feminist art movement had strong roots in Mexico. Following the 1975 World Conference on Women which was held in Mexico City, many exhibitions discussing the themes of the conference sprung up. By focusing on mainly white European and white American feminists, the exhibition doesn’t fully encapsulate the experience and art of all women.

Written by: Orla O’Sullivan, LVI Wr

Graphic design by: Annabel Luyckx

Ultimately, the feminist art movement of the seventies was significant as it helped feminists to engage with the public through seizing works of art and it allowed them to express their frustrations at the patriarchy. The new and exciting mediums through which artists did this perhaps reflected the enthusiasm for the new beliefs surrounding feminism. The exhibition captures the Eurocentric depiction of this but largely neglects other experiences. This shows that equal representation in exhibition and galleries, a part of the feminist art movement, has not been achieved yet and that there is still more work to do regarding equality in art.

Art as Activism: the Art of Protest -Emma Moreira

Traditionally, art was reserved for only the elite; it has now evolved to be an extremely accessible and versatile tool for social change in the form of protest art. Avant-garde is a popular term for artists whose work is visionary and ahead of their time. Protest art grew in popularity dramatically in the 1980s as the decade’s socio-cultural climate was deteriorating. As racism, sexism, apartheid, and an AIDS epidemic fragmented society, and artists were confronted by a world demanding radical change, they pioneered a new approach to address these political and cultural fault lines.

When the AIDS epidemic erupted during the 80s, many artists used their art as a platform to challenge the stigmatisation of the LGBT community. One such piece is David Wojnarowicz’s black and white photograph ‘Death = Silence’ (1986), created for a short documentary with the same title. The image depicts Wojnarowicz’s with his mouth sewn shut. Wojnarowic suffered from AIDS himself and used the performance to criticise the government’s silence on AIDS intervention; his anguished eyes express his frustration at the denigrating treatment of its victims. The pain Wojnarowicz inflicted onto himself created a gruesome image that resonates with us today, and the piece is among the most influential of protest art since World War Two.

The Guerrilla Girls is a group of anonymous female art activists, founded in 1985 New York, with the aim of trying to combat sexism in pop culture. To maintain their anonymity, they wore guerrilla masks and used pseudonyms referring to influential females such as Harriet Tubman. They led numerous street art projects where they used bold headlines, visuals, and statistics to expose gender biases.

Their most famous creation was a 1989 poster titled ‘Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met Museum?’ This iconic poster mimics French artist Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres's painting ‘Grande Odalisque’ (1814), featuring the same girl wearing a gorilla mask and the statistic “Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female”, highlighting the misrepresentation of women in the media with pop colours. The poster was displayed on New York buses, a tactic developed in the 80s, so that the issue came to be at the forefront of public consciousness. The posters are still in circulation today, having led to a wider range of female artists represented by prominent art institutions such as the MoMa and the Met.

Jean-Michel Basquiat was a Haitian American street artist whose work focused on societal dichotomies such as poverty versus wealth and integration versus segregation; he also focused on the idea of identity, advocating for marginalised communities. His art emerged on the streets of New York as he used the city as his canvas, creating graffiti art on subways and walls for all to see. Graffiti had previously been considered an act of vandalism; however, his clever wordplay and use of colour provoked a new and accepting attitude towards street art. Basquiat also broke barriers in an overwhelmingly white-dominated art scene, acting as the voice of the marginalised and paving the way for other artists of colour.

Tania Bruguera, a contemporary art activist, describes political art as “transcending the field of art, entering the daily nature of people, an art that makes them think... Political art is uncomfortable knowledge.” Art was revolutionised in the 80s, powered by and against a backdrop of rapid social and political transformation. It channelled innovation and creativity from a pool of extraordinary artistic talent that was at times provocative, but always inspirational. Avant-garde art touches a raw nerve, prompting the viewer to reflect on the world in which they live. It has made activism accessible to the public, and it is this intersection of art and politics that serves as a nexus for change.

brat a contemporary case study of avant-garde music marketing

techniques

by fenella rawlins

‘What is brat?’ was the question on everyone’s minds in the summer of ‘24. At first glance, ‘brat’ is evocative of leaving your makeup on overnight, or rocking up to a party fashionably late, but its meaning runs deeper than these seeming trivialities. ‘brat’ is not caring what the rest of the world thinks, what it means to be an individual, doing what YOU want to do regardless of outside influence. It involves strong, independent and powerful women rejecting societal norms and beauty standards as they redefine what it is to be a woman. However, whoever you pose this question to will inevitably answer differently, and that is the beauty of it. This complexity and nuance in what ‘brat’ means to different people is a direct result of the avantgarde way Charli xcx’s 2024 record was marketed, irrevocably altering how the industry operates.

Her approach began with an elite private Instagram finsta ‘360_brat’—xcx’s way of interacting and rewarding long-term fans by releasing exclusive content and asking their opinions on certain topics regarding the album. Whilst it is commonplace for artists to use social media platforms such as Tumblr and X to connect with fans, ‘360_brat’ was a personal window into xcx’s life. The breaking down of this barrier between the artist and the fans, the producer and consumer, was revolutionary. There was incredible activity on the page and, as a result, the participation and excitement surrounding the record pre-release was heightened; naturally, individuals felt emotionally invested. People would go out of their way to promote and post, giving the album even more digital traction. Lastly, the official music video for ‘360’, one of the most popular songs on the album, featured a number of pop culture icons, including a table of ‘it girls’ lip-syncing to different parts of the song, described as “an earth-shattering moment for chronically online people”. Amongst these were Quenlin Blackwell, Alex Consani, Emma Chamberlain, Julia Fox and many others. This video amassed over 25 million views at the time of writing, as it called every fanbase of each star to watch the video, creating further exposure and engagement. The diversity of individuals in this music video showed the multitude of meanings ‘brat’ could take for them and the audience, which would synthesise to become a celebration of individualism and female empowerment. Ultimately, this was what her album’s release thrived on –

ambivalence and controversy. The ‘brat’ and the ‘messy girl’ aesthetic overtook trend after trend, kicking to the curb the beauty standard of the ‘clean girl’. Women were free to wear however much makeup they wanted or didn’t want, concurrently liberating themselves from the male gaze.

These revolutionary marketing techniques amalgamated to ‘brat summer’ becoming the phrase on everyone’s lips. ‘brat’ was no longer just an album but a lifestyle, hence why it received a nomination for Album of the Year at the Grammy’s alongside some of the largest names in music. The lyrics of ‘brat’ deserve to be spotlighted as well; lines such as ‘'Cause I couldn't even be her if I tried / I'm opposite, I'm on the other side’ and ‘'Cause for the last couple years / I've been at war with my body’ represent the ubiquity of the internal struggles girls and women experience. Track 10, ‘girl, so confusing featuring lorde’, explores a difficult ‘frenemy’ relationship between xcx and Lorde, a fellow successful artist often considered xcx’s doppelganger. The song follows a relatable and authentic discussion between two mature women, showing that the music industry’s tendency to pit women against each other can be overcome – through ‘brat’. The song ‘Apple’ went viral for the famous ‘Apple’ dance, but the fun, upbeat tune explores family trauma and unrest: ‘I think the apple’s rotten right to the core, from all the things fell down from all the apples coming before’. However, the fact that this artist unpacks her difficult familial relationships through an electronic dance beat showcases her ability to both acknowledge and grow from it. Equally, the track ‘Sympathy is a knife featuring ariana grande’ explores complicated relationships with the media through lyrics such as ‘the next step is they wanna see you fall to the bottom’, and ‘It’s a knife when they dissect your body on the front page’. With an upbeat synth underneath these heartfelt lyrics, the dichotomy of xcx herself as both a ‘365 party girl’ but also ‘just a young girl from Essex’ is explored, demonstrating the complexity of her character and that women may break free of these binary constraints.

The efficacy and revolutionary design of ‘brat’’s marketing will be studied and replicated in years to come. For the meantime, I think it’s safe to say that WHAT is ‘brat’.

By Ana Schraepler De Devise

to explore new sounds and ideas, whether it is discordant, like John Cage’s pieces, or tranquil like Glass’.

The Impact of The Avant Garde on Language

-Sophia dowsett

As the avant-garde swept through the creative world in the beginnings of the 20th century, literature and culture as we know them were completely transformed. The avant-garde pushed societal boundaries, particularly in the way we visualise art, however what many fail to appreciate is the impact the avant-garde had on language itself. The movement revolutionised not only what we say, but also how we say it.

The structure of language was challenged throughout this period as movements like Dadaism, Surrealism and Futurism forced a linguistical transition away from traditional grammatical conventions in favour of more chaotic sentences that upon first impression, don’t always make sense. Language was no longer bound by the constraints of punctuation and grammar, which can be seen most famously in the works of the Romanian poet, playwright and critic of the arts Tristan Tzara. Tzara draws on his passion for Dadaism in arguably his most famous play “Handkerchief of Clouds” staged in 1924, in which the language used is borderline nonsensical and the order of scenes is extremely fragmented. The play was both fascinating and disturbing to audiences of the time, however its main goal was to shock and critique the world of art, which Tzara found overly materialistic. Tzara also gained renown through his poetry, in which he cut random words from newspapers, jumbled them and then randomly reassembled them, resulting in nonsense that forced readers to

acknowledge the notion that meaning is not concrete, it is designed. This approach reflects the disillusionment of the world after The Great War, and thus through Tzara’s work we can appreciate how language was used as a tool of the avant-garde, in order to disrupt traditional art forms in a particularly disturbing way.

The pronunciation and sounds of words were also put into question during the avant-garde movement, as writers began to use tools like onomatopoeia to a much greater and more intense level. For example, when the Italian Futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti wrote the “Futurism Manifesto” in 1909 which was printed on the front of Le Figaro newspaper, he used the avant-garde to invent the idea of "parole in libertà" (words-in-freedom). “Parole in Liberta” used onomatopoeia, typography and fragmentation to evoke a sense of panic and chaos in the reader, with the intention of emulating the pain of battle. In his work, sounds mimicking the roaring of engines or the hustle and bustle of cities can be heard, demonstrating his capacity to transform writing into real life scenarios. Marinetti advocated for the use of spontaneity, speed and expression in literature, instead of syntax and logic in order to increase the emotional level of writing.

Surrealism, an extremely prevalent movement of the avant-garde, also revolutionised language as it began to be used as a means of exploration of the

subconscious and irrational. The work of André Breton, a French writer, poet and theorist of the time, is the most notable example of this, as he emphasised the importance of automatic writing as a way to access the unconscious mind and avoid the imposition of an authoritative narrative. Breton wrote down whatever came into his mind, without grammar or any sense of logic, resulting in a pure stream of consciousness lacking any form of rationality. Therefore during the movement of the avant-garde, Breton revolutionised how language can be viewed as a gateway to the inner self, and is much more than simply the relaying of facts or information.

Breton’s work changed how language relates to emotion and identity, through his use of Surrealism and the avant-garde.

The avant-garde also continues to have an impact on language today in a range of different ways. Postmodern authors still experiment with themes such as non-linear storytelling and chaotic structures, which are both hallmarks of the movement.

Authors such as James Joyce and Kathy Acker are the most famous contemporary poets for this style of writing, as they often step away from conventional grammar and the traditional sounds of words, in order to convey the deep emotions of their content. The exciting and fun nature of typography, used in Dadaism and Futurism is also now

mirrored in the use of memes and emojis. The avant-garde was renowned for mixing words with art, which is extremely similar to the way that in the modern day online we use GIFs and hashtags to convey our emotions, highlighting the long-lasting effect the avant-garde has had on how we view writing. Finally, traces of the avant-garde can also be found in modern media and marketing, as brands often intend to shock viewers in their adverts, in order to make their brand more memorable. This technique draws upon the movement of surrealism which grew rapidly during the avant-garde period, as often slogans and the names of brands defy logic and anything we could have expected.

To conclude, the avant-garde dramatically changed the way in which language is viewed and communicated, which continues to have an overwhelming impact on the art of writing today. The avant-garde used language as a means of expressing the discontent of a post-war world, in which traditional writing was not seen as adequate. Although at the time much of the new language produced, influenced by movements like Dadaism and Surrealism was shocking and caused public disruption, we can now appreciate its significance in revolutionising the meaning of words.

Rebels In Rebels In Rebels In

As the visionary Italian architect Vico Magistretti once said, the objective of art and design is to 'look at usual things with unusual eyes'. It is this that the avant-garde tries to achieve: by pioneering innovation andd experimentation, the avant-garde acts as rebellion against societal and cultural norms in an attempt to embrace or challenge change. The most radical examples of this have been the abstract expressionism which marked a departure from representational art to champion a change towards individuality and freedom, or conversely, the Dada movement, which was a response to the societal change following the first world war. However, in spite of the enthusiasm and widespread attention given to these movements initially, novelty, by its very nature, ultimately wears off as the once insurgent ideas are institutionalized. This article will explore the extent to which this domestication is inevitable by looking at the specific case of Pop Art.

Just as the futurists were fascinated with the dynamism of industrializationand the surrealists engrossed themselves with the human psyche, most avant-garde movements arise from the radical philosophies that thrive on the fringes of our society. Similarly, pop art began as a rebellious reaction against the elitism of abstract expressionism, challenging the post-World War II economic boom and the subsequent rise of consumerism in Western societies. Famously influenced by mass media and consumer culture, pop art served as a critique to consumerism, with artists such as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein employing bold striking colours, iconic figures (e.g. Marylyn Monroe and Mickey Mouse) and easily interpreted imagery to explore the boundary between necessity and consumerism, accessibility and elitism.

The first pop art works, as with many avant-garde movements, were seen as transgressive and blatant symbols of resistance; however, these pieces soon became highly sought after commodities, creating a profound irony to the movement's initial critique. For example, Warhol's art has become a universal symbol of cultural prestige, with his piece ‘Shot Sage Blue Marilyn' (1964) setting a record for the most expensive 20thcentury artwork, sold at a Christie's auction in New York, for a staggering $195 million . Through mainstream commodification, pop art is just one of the many examples of avant-garde movements' critical stances becoming obscured by mainstream acceptance. Hence, through the case of pop art this paradox arises: for a movement to succeed, it must be recognised and disseminated, but to what extent does this process shift art from the periphery to the centre of conventionality?

Perhaps it is this very relationship between rebellion and institution that ensures the vitality of art; the endless cycle of disruption, assimilation and renewal acts as a clean slate for new and emerging movements. Ultimately, for the avant-garde to succeed, it must lose its insurgent status to achieve a lasting impact. The rebels of one era are the classics of the next.

Written by: Ginevra D’Avanzo, LVI

Graphic design by: Annabel Luyckx

MAKING THE PERSONAL POLITICAL: HOW FAR CAN FEMINIST THEORY GO?

CHERIE NG

‘The personal is political’

A phrase popularised by second-wave feminism in the 1960s, has become the rallying cry in each emergent social justice movement, shedding light on the intricate interplay between public and private spheres of life. Notable examples that come to mind include the Wages for Housework campaign that considered housework feminised labour deserving of compensation, and the #MeToo movement when personal grievances over sexual assault were offered up for public scrutiny. In 2022, the line between personal and political blurred into one when the overturning of Roe v. Wade made women’s bodily autonomy the subject of heated national debate. In the final months of 2024, a bill put forward in Iraq’s parliament proposed slashing the age of consent for girls to nine. When women’s reproductive rights fall under the jurisdiction of the legislature and the courts, the notion that political institutions inform our lived experiences within them is hardly to be disputed. But is there any remaining demarcation between the personal and the political? To what extent should these power structures be held accountable for, and made to rectify, seemingly personal grievances?

Arguments for the inseparability of the two are often advanced by radical feminists[1], and most succinctly by Andrea Dworkin in 1983: “The personal is political because private life is where we experience the effects of public policies, where we are most directly subjected to the power of the state”. This state power manifests itself, on a microcosmic level, in the nuclear family model where the father is the patriarch. Conversely, paternalism—a mode of governance that justifies restrictions on personal liberty by claiming it is in the people’s best interests—has its etymological grounding in the adjective paternal. The personal and political are thus in a symbiotic relationship. Marxist feminism provides a further layer of analysis to this: as the state/bourgeois oppresses the people/proletariat, women are oppressed in the household by men who undervalue and exploit their domestic labour, which in turn sustains the capitalist system by keeping production costs low. Engels, the co-founder of Marxist theory, argued that that “the first-class oppression coincides with that of the female sex by the male” in 1884. It attests that the commodification of domestic labour has resulted in the personal made political. This is a compelling argument, albeit one that should not be taken at face value: Marxist feminism has come under fire for grounding itself exclusively in class struggle. However, whilst it may be lacking in intersectionality, it has nonetheless been a potent force in the diversification of feminist thought.

An institutional problem is much harder to resolve. It requires identifying systems that perpetuate inequality and holding its enablers accountable, and then restructuring these to deconstruct patriarchal narratives. The first step is necessarily entering an issue into public discourse; in other words, recognising how the personal and the political are interwoven, possibly even one of the same. Consciousness raising emerged in the 1960s as a form of political activism; women gathered to reflect upon how seemingly isolated, individual experiences of sexism shared the same backbone of common conditions indicative of systemic injustice. Ellen Willis wrote in 1984 that consciousness raising has often been "misunderstood and disparaged as a form of therapy” but had been "the primary method of understanding women's condition” and constituted "the movement's most successful organizing tool." At its height in 1973, an estimated 100,000 women in the US belonged to these groups. It is worth noting that these were exclusionary, with the overwhelming number of participants being white, middle-class women; hence, dialogue seldom addressed the intersectionality between race, class, and gender. Organisations with a similar methodology but distinct ideological framework, such as the Combahee River Collective, emerged to combat interlocking systems of oppression with a focus on identity politics.

In my opinion, to dismiss the political from the personal would be imprudent. Labelling an issue as apolitical absolves governments and institutions of the responsibility of tackling it head on to construct a more equitable society conducive to the common good. Feminist schools of thought have always been embedded in historical, cultural, and socio-economic contexts, and the feminist movement in the political currents of its time. They seek to challenge the status quo that politicians uphold, however unwittingly, to retain their position at the top. At present, as many fear the adverse impact global democratic backsliding may have on women’s rights, the personal seems, more so than ever, constrained within the political. But this is also where sites of resistance may be built. Grassroots education initiatives can dismantle gender stereotype and avert the harm that would otherwise be done to impressionable young minds.

The sharing of personal accounts of sexual harrassment, on platforms such as Everyone’s Invited, or Laura Bates’ Everyday Sexism Project, can amalgamate to create political pressure for legislative reform. Separating the personal from the political makes the latter seem an incontrovertible truth and an unalterable reality; it is antithetical towards the spirit of social reform.

By recognising the personal as political, we become the players rather than played. We reassert the belief that we can be the driving forces of change.

The Theatre of the Absurd: The Avant Garde of Literature

Theatre of rd: Absurd: Avant Av of G

rld W W

With the move nty, trauma t it cam diers f inse return to normal life retu mselves th themsel damage irreversible and . The world was thrown into a new w victim to. Th tha consumerism boomed with a rise i suburban middle

While on the it seemed that what had cracks be to traum to.

does one even begin to face it? The Theatre o Absurd seemed, in an unconventional t thecracks.TheTheatreoftheAbsurdmayn

War 2, a, from and he fell way of this n class. been egan ma How f the o fill

By Caroline Stephens

By

“Est absurde ce qui n’a pas de but…” (“Absurd is that which has no purpose or goal or objective”). A definition by Eugène Ionesco, A Romanian French playwright who is considered the uncrowned king of absurdism. If he is right, why has absurdism had such an impact to the world of theatre and literature, why is it that it meets the exact objectives, needs, and wants of the audience or reader without them knowing it?

reader without them it?

Absurdism was a movement that in

have a traditional format, a clear beginning, middle and or a clear villain and hero but it

phenomenon. According to Martin Esslin in his book ‘The Theatre of the a reason. audience is watching, was coined to show what happens, as Adamov mov says, whenhumancommunicationbreaksaksdownwhich absurdism “can arouse or and conjure up an atmosphere of poetry even if devoid of motivation and unrelated to human characters, emotions, and It artistic norms and is an ‘antiplay’ with actors to “act the

Absurdism was a movement that emerged in Europe in the 1950s and 60s and is seen to be an avant-garde phenomenon. According to Martin Esslin in his book ‘The Theatre of the Absurd’, absurdism “can arouse laughter or gloom and conjure up an atmosphere of poetry even if devoid of logical motivation and unrelated to recognisable human characters, emotions, and objectives”. It rejects artistic norms and is an ‘antiplay’ with actors having to “act against the dialogue”. It was established to unravel the real meaning behind the human language and often many lines would be spoken in a different order or have a different meaning to what was said. Actors would swap characters halfway through and parallel scenes may not have anything to do with what was happening in the play.

With the movement appearing post-World War 2, it came after a time of uncertainty, trauma, insecurity, and instability. Soldiers returning from battle were expected to return to normal life and re-integrate themselves into society after the irreversible and unforgettable damage they fell victim to. The world was thrown into a new way of life that no one knew how to deal with. To fill this void, consumerism boomed with a rise in suburban living, conformity and the middle class. While on the surface, it seemed that what had been broken had been put back together, cracks began to show. It was impossible to erase the trauma World War Two had caused; despite trying to. How does one even begin to face it? The Theatre of the Absurd seemed, in an unconventional way, to fill the cracks. The Theatre of the Absurd may not have a traditional format, a clear beginning, middle and end, or a clear villain and hero but it runs deeper than both those things, philosophically.When Arthur Adamov (another key absurdist writer) was writing his first play, La Parodie (1947) he said, “This gave me the idea of showing on stage, as crudely and as visibly possible, the loneliness of man, the absence of communication among human beings”. It should be made clear though, that despite it expressing exactly what is needed to be said, it is called The Theatre of Absurd for a reason. The audience is not meant to understand what they are watching, nor would they be able to if they tried. It was coined to show what happens, as Adamov says, when human communication breaks down which is what happened in the Post-War world. The audience is incapable of understanding a reflection of what is going on in their own lives, their own reality when put on stage, seemingly a foreign concept.

It was established to unravel the real ften o nt order or was said. Actors would swap characters parallel scenes may not ha t what was hap down world. The un f a i on in their own lives, their own wn p en seemingly a foreioreign

The theatre of the absurd is a significant aspect of the avant-garde, exploring the fundamental absurdity of the human-condition. It quintessentially explains what humanity was lacking and is lacking today. Despite it being unconventional, untraditional and perhaps unsettling, ‘The theatre of the Absurd is the true theatre of our time’ – Martin Esslin.

The t he of ring h he human-condition. It ally g un – Esslin.

Food as Performance: Avantgarde Gastronomy in East and Southeast Asia

–by Aryana Cadbury

Figure 2: Frozen red curry and lobster salad

Figure 1: Mango sticky-rice

Figure 3: Sea-urchin omakase

Figure 4: fatty tuna nigiri with caviar and gold leaf

Figure 6: example of Gaggan dish

Figure 5: example of Gaggan dish

Does avant-garde Art still exist today?

Adolph Gottlieb, who was an American abstract expressionist painter, once made the remark that artists are “at war with society”, which is why they suffer from “social neglect”. Throughout the history of art, there has always been a restless urge to break through boundaries , and find new concepts and ideas. This has become the expected from a modern audience, that all art should be extraordinary and groundbreaking. So therefore, in the modern world, could it be possible that the audience’s expectations of art means that ‘avant-garde’ art can no longer exist?

Avant-garde is French for ‘advanced guard’, and in reference to art this term means any artist, movement, or artwork that is regarded as innovative and radical as well as carrying an association of being daring, experimental, and unconventional. Because of the fact that it challenges existing ideas, processes, and forms, avant-garde art has often been met with resistance and controversy.

One could say the idea of avant-garde art originated with the Realism of Gustave Courbet, as this is often cited as the first avant-garde movement. Art historian Linda Nochlin said Courbet is “the painter who best embodies the dual implications – both artistically and politically progressive – of the original usage of the term ‘avant-garde”. For this time, it was a new concept to be emphasising the harsh realities of life, especially the working-class life, hence why Courbet has gained the title as one of the first avant-garde artists, with his provocative works such as The Stonebreakers.

Throughout the history of art since then, artists have been coming up with new and experimental concepts, each pushing the boundaries of previous art a little further. It was not Realism but Impressionism which was the first avant-garde movement to gain widespread influence and fame. Coming together in the 1860s, Claude Monet, PierreAuguste Renoir and Paul Cezanne to mention a few had developed a radical technique, involving loose and spontaneous brushwork, as well as painting outside to capture the optical effects of light. This movement shifted the concept of avant-garde towards an emphasis on formal and aesthetic innovation rather than social or political reform.

The number of avant-garde movements and artists are countless, from post-impressionists such as Georges Seurat, Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, who all took radically divergent and individual paths that profoundly influenced subsequent avant-garde art. To other 20th century movements such as Cubism, (which reduced everything to geometric outlines and cubes), and conceptual art, (art in which the idea or concept is more important than its appearance or execution). Therefore, it is no surprise that art has now pushed almost every limit, and broken countless boundaries, each more extreme and thought provoking than the last which in turn creates revolutionary art. Now, we see all kinds of ‘modern’ art, such as Damien Hirst’s works of dead animals, preserved in formaldehyde. These works would have been unthinkable one-hundred years ago, but since art knows no boundaries now, it appears seemingly ‘ordinary’.

At the pace in which new concepts are being explored, has it become a norm in society, that art is simply expected to be original and innovative? Avant-garde art, is supposed to stimulate a shock and discomfort for the viewer, whether this is through disbelief, or complexion, or any other extreme emotion. But since it is getting more challenging to achieve this reaction in the viewer, as no concept seems impossible any more, would this mean that there is no longer such thing as avant-garde art?

Many contemporary artists have spent the last two decades obsessed with the question of media, and some have even become media entertainers of sorts, as they want to be credible as avant-garde but at the same time to be loved by an audience. The question of avant-garde is whether it is still possible to create such a revolutionary concept, that it can still be considered avant-garde, rather than just another artwork conforming to existing limits.

Many contemporary artists have spent the last two decades obsessed with the question of media, and some have even become media entertainers of sorts, as they want to be credible as avant-garde but at the same time to be loved by an audience. The question of avant-garde is whether it is still possible to create such a revolutionary concept, that it can still be considered avant-garde, rather than just another artwork conforming to existing limits.

As one idea emerges, seemingly daring and unconventional, it is hastily replaced by an even more extraordinary concept, which in turn downgrades the former idea to something ordinary and not quite so avantgarde. Artists have now become so daring, that nothing appears to be impossible. Ai Weiwei, for example is one of the great provocateurs of our time. His work Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995 depicts the artist as he smashes a 200-year-old ceremonial urn, of significant symbolic and cultural worth. If even the destruction of art can now be considered art itself, has almost every limit has been reached?

Can we speculate that this new day and age is the death of the avant-garde? One could argue that no movement in art can be so radical and extremist that it can be considered avant-garde; as for art to be considered avant-garde it must appear to be wildly daring and progressive. Although this it may be, our modern day audience is so used to unconventional and revolutionary art that it no longer considers new art concepts to be this. I believe the world is moving at such a pace today that there is barely room in society for the avant-garde in art.