For Monica Rudquist, there is little that distinguishes her creative practice from her teaching, her home life from her studio routine, her parenting from her mentorship. Being an artist is the fabric of her life, informing her relationships and her teaching, guiding her through personal challenges and sustaining her joy. Though never knew her late father, Jerry Rudquist, am learning that he, too, built a fulfilling life of art, family and professorship. While this exhibition traces the formal connections evident between Monica’s ceramics and her dad’s paintings, it also marks a major shift in her career: soon she will move on from teaching to return to a full-time studio practice. As she contemplates her sabbatical year and prepares for her upcoming retirement, Reflections and Conversations follows Monica’s creative journey during a time of transition.

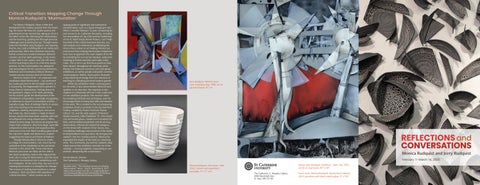

Monica’s newest work — an expansive wall installation titled Murmuration — has anchored her studio practice for the last eight months. It is inspired by the fragmented forms present in many of Jerry’s abstractions. Feeling drawn to the geometric shapes in her dad’s paintings, she let instinct guide her development of the installation’s composition, eventually recognizing its reference to nature’s murmuration of birds — typically a large flock of starlings that fly in unison, each one reacting to the movements of its neighbors, swirling and pulsing as one across the winter sky. Murmuration is made of wheelthrown vessels that have been carefully split and reconfigured into wing-shaped pieces. When viewed at close range, the pieces are angular and sharp; from a distance, they form large, wave-like compositions that narrow and expand as they move across the wall. Black crackling glaze lends the clay forms depth and dimension, indeed suggesting the texture and flutter of feathers. Though Monica didn’t intend to create an image of a murmuration, am struck by the symbolism of the installation at this particular moment in the artist’s life. Those who know Monica’s past work can likely see the shift in her visual vocabulary, both in the shape of the forms she is using for Murmuration, and the more immersive environment she is establishing with the installation. At the same time, the very act of creating Murmuration is a metaphor for change.

The science of starling murmurations is rooted in physics, “best described with equations of ‘critical transition,’” when systems are at a

tipping point of significant and substantive transformation, such as a liquid changing to gas. When consider Monica’s 16 years of teaching for and service to St. Catherine University, including her stewardship of Clay Club and her leadership of the St. Kate’s Empty Bowls Project, can’t help but think of the critical transition that she, too, will embark on in retirement, recalibrating her time to focus solely on art making. Monica has mentioned that creating Murmuration helped her learn how to approach this next chapter of her life by reminding her to trust her intuition, rediscover meaning in formal curiosities and make, make, make. This is not to say that these practices have been absent: throughout her teaching career, Monica has balanced numerous solo and group exhibitions, as well as private and public commissioned projects. Rather, Murmuration illustrates a repositioning of energy from the structure of teaching to cultivating personal creative growth. While this exhibition marks a turning point for the artist, it also demonstrates Monica’s best qualities as an educator. She regularly invites students to collaborate with her in the studio and on her exhibition projects. She mentors them by modeling methods and techniques, and she encourages them to bring their skills and interests to the work. This is evident in the accompanying exhibition of Jerry’s portraits in the Second Floor Gallery, curated by Project Assistant Sophia Gibson ’25, and the vital support of Monica’s Studio Assistant, Sofia Osterlund ’25, who mixed clay and tested glazes, loaded and unloaded the kilns, and provided empathetic and discerning observations. Monica has shared her progress on this show with students in her classes, too, normalizing challenges and successes in the studio, inviting feedback and questions. By bringing her students into her creative practice, Monica has expanded the impact of her work as a teaching artist. The community she and her students have made around this exhibition reminds me of the starlings — moving together, responding to one another, deepening the conversation.

Nicole Watson, Director

The Catherine G. Murphy Gallery

1Brandon Keim, “The Startling Science of a Starling Murmuration,” Wired – Science, November 8, 2011, https://www.wired.com/2011/11/starling-flock/#:~:text=Starling%20flocks%2C%20it%20turns%20out, is%20connected%20to%20every%20other.

February 1–March 16, 2025

Growing up surrounded by my father’s artwork never really looked closely at it, or considered if my own artwork might have some connection to it. He was my dad. During my 2022–23 sabbatical, had the opportunity to reflect on our parallel lives as artists who teach, and consider if there was a relationship between our art.

see my life reflecting his in many ways: we both began making art early in our lives, we had supportive families, and attended the same graduate school where we met our life partners, who we brought back to Minnesota. Those partners support(ed) us and our creative work unconditionally. Exhibiting our work has been critical to our lives as artists — during his early career in the 1970s, my father was represented by Suzanne Kohn Gallery, and later Groveland Gallery, where he showed his work until his death in 2001. received exhibition opportunities when joined the Women’s Art Registry of Minnesota (WARM) in 1986, and in 1991 became a founding member of the Northern Clay Center in Minneapolis. Since then have participated in local, regional and national solo and group exhibitions, juried exhibitions and art fairs. Both my dad and found teaching was where we engaged with a community that fostered our creativity. My dad’s first and only teaching job was at Macalester College in St. Paul, where he taught painting for 42 years. My path as an educator has been different: began by teaching all-ages and allmediums classes at art centers across the Twin Cities. My first higher education position was a sabbatical replacement at St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota, which led to my adjunct and eventual full-time positions here at St. Kate’s. Though Dad never saw my work in higher education, his dedication to teaching and his mentorship of students became a model for my own approach. From lesson plans on the dining room table to students who became lifelong friends, my work as an educator mirrors my dad’s role as an art professor. My father was my first mentor, showing me how could live my life as an artist and have a thriving family. We both filled the traditional role of caretaker. Our partners, both architects, had demanding careers of their own and teaching provided a flexible schedule that allowed for engaging in school activities with our kids, helping with homework and making daily dinners. My dad was always ‘working’ with a drawing book by his side, the dining room table covered with schoolwork and a small workspace for painting in our sunroom. Yet he was always there for his family, and we knew that we came first. His work ethic and ability to balance home activities, daily art practice and the work of being an educator is something that have strived for but have learned is difficult to sustain. We share an internal need/drive to make/create that is more of a lifestyle as opposed to a career that can be separated from our being. My sabbatical made it clear that teaching through the pandemic had left me creatively drained. needed to return to my studio practice full-time in order to make work. This led me to the difficult realization that needed to retire from teaching. It was also at this time that I began sorting through my dad’s archive with my sister; was looking closely at my dad’s art for the first time, and discovered a series of conversations between our artworks. Similarities, or moments of alignment, in the ways we approach form and space; our tendency to work within a series, utilizing abstraction and surface texture. These conversations led to my new work titled Murmuration. Working on this installation and curating this exhibition brought me back to my studio and re-energized me. haven’t felt this free in the studio for a while, where I could experiment, trust myself, and just work. As my mom used to say, “Make what is in your head because no one else will.” Thank you, Mom and Dad, for helping me through this big transition.

A first glance, Monica Rudquist’s porcelain ceramics have little in common with her father Jerry Rudquist’s body of work. Monica’s sculptural and functional ceramics are three dimensional, and Jerry’s paintings, drawings, prints, and photographs are resolutely two dimensional. Monica utilizes a limited palette of neutral glazes — white, black, with the occasional celadon interior. Jerry, on the other hand, was declared by one arts writer to be the “guru of color,” known for employing a full range of highly saturated, almost shocking, hue interactions. And in this exhibition, Jerry’s work is from the previous century (he died in 2001) and Monica’s work is brand new, started during her sabbatical leave in 2022–23.

Both, however, are masters of their chosen art, with many accolades on their curricula vitae History and theory are foundational to both their practices, with exquisite attention to the techniques and nuances of their respective crafts. As this exhibition demonstrates, both Monica and Jerry work in series. In one of his handouts for his painting class, Jerry wrote, “Painting is a thinking process.” We can discern his thinking, and Monica’s, as they both individually work their way through ideas, conceptual and aesthetic, by returning to themes and forms over and over again, probing for that new insight through multiple manipulations.

In he West Gallery, Monica’s wall installation, Murmuration, flows over and around two of Jerry’s painting series, Warflowers and Must We Always Expect War.

creates the illusion of depth and space — strange as they look, these non-objective objects could be constructed in three dimensions. Remarkably, the shapes in both series have a strong connection to the negative spaces that surround them. This is especially clear when the Gemini figures touch the edge of the picture frame as in Snarf and Ubsurd the background is energized and becomes integral to the composition. Likewise, the negative spaces between and around Monica’s trays are energized too. In fact, the space in between any two trays mimics the shapes of the figures of Gemini. The positive forms of Gemini become the negative spaces between the tray pairings. Both artists are explorers of the ambiguous spaces in between.

The softness of Monica’s title (meaning the utterance of low, continuous sounds or complaining noises, according to Merriam-Webster online) belies the sharpness of hundreds of clay shards, a literal representation of brokenness. The first of Jerry’s Must We Always Expect War paintings was done in 1956 in response to the Korean War, and he continued painting these over 40 years, as there has been sadly no lack of armed conflicts involving the U.S. Screaming skull images, the intensity of saturated reds and blues, and furious brushstrokes insist on presenting the urgent horribleness of the carnage of war. While Jerry’s work sounds the alarm, Monica’s installation seems to be trying to fit it all back together, picking up the pieces in the aftermath.

We cannot turn away, even in despair, as we are surrounded on all sides with these unequivocal, devastating statements.

If the West Gallery presents a united cri de coeur the relationships are more subtle in the East Gallery. For example, Jerry’s Gemini series is juxtaposed with Monica’s trays. The Gemini works are small, jewel-like paintings inspired by his participation in the NASA Fine Art Program in the mid-1960s. In each piece, an abstract figure is presented against a flat ground, evoking the structures needed to launch rockets into space: cylindrical engines, triangular capsules, supporting gantries. Perhaps Moondog shows that moment when a capsule is jettisoned into weightless space from its booster

rocket. As a group, the Gemini series is a meditation on the uncanniness of space as experienced by our earth-bound bodies.

Monica has inser ted trays into the flow of the Gemini series. If these were flat on a table, they would function as containers for food, but here on the wall they enjoy being sculptures. These white, shell-like vessels began as traditional wheel-thrown bowls, but then mutated, having been cut apart and reassembled into dancing circles and ovals that ebb and flow.

These organic shapes are in dialogue with Jerry’s Gemini paintings. While Monica’s spaces have actual depth revealed by cast shadows and touch, Jerry

In the creative arts, the hand speaks eloquently. The marks of Monica’s hands are clear in the grooves and ridges impressed into the soft clay as she shapes it on the wheel. She exploits this aspect of her process to create texture and line — it is one of her signature marks as a ceramicist. Less obvious are the fingerprints and palm prints in Jerry’s paintings that create texture and cross-hatched shading. Aficionados of Jerry’s art know to look for these distinguishing marks across his body of work. first met Monica Rudquist when was hired, probably in the summer of 1972, to babysit her younger sister Michelle. Jerry was my painting professor at Macalester College, and he explained that though Monica was too old and mature to need a babysitter, she would hang out with us anyway. recall we three had a fine time that summer. Fast forward to 2008: was teaching art and design at St. Catherine University and found myself as chair of the Art and Art History Department. We had an opening for a ceramics instructor so I invited Monica to apply for the job. And now she is presenting her sabbatical year exhibition at the Catherine G. Murphy Gallery, and honoring Jerry’s legacy through this profoundly moving visual conversation.