13 minute read

The Black Box

{the black box}

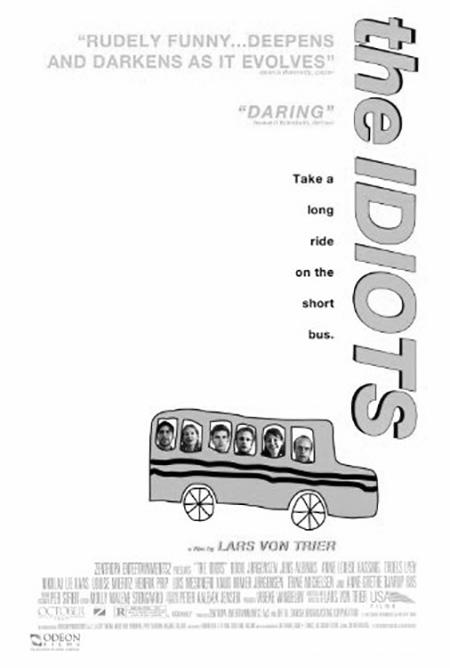

Gruppeknald: anAnalysis of Lars Von Trier's The Idiots

Advertisement

Ranger Kasdorf

The Black Box is a new column intended to serve as a home for polity submissions that engage with television, movies, and cinema. In this inaugural column, Mr. Kasdorf gives a compelling account of the film The Idiots and the themes of community and cruelty within.

It is rare– more now than ever– that a person belongs to just one community at a time. Beyond being part of the loose community of St. John’s College Annapolis, we, the Annapolis Johnnies, have also cleaved to one another independently, forming our own bands, groups, troupes, clubs, and cliques– not to mention any non-Johnny communities which students occupy on their own time. One would have to be the most reclusive Room Johnny imaginable and lack an internet connection to be solely a part of the St. John’s student body.

These various communities tend to be both wholly compatible and wholly separate. A student who goes to church on Sunday, attends seminar on Monday, and watches a movie with their Discord server on Tuesday acts as a member of three separate communities, and not one of them is ever in conflict with either of the other two. What’s more, each community’s activities are self-contained: nobody in your seminar needs to hear about your priest’s latest sermon, nobody in your Discord server needs to hear about the Unmoved Mover, and nobody in your church needs to hear about last night’s heated debate over whether or not Robert Pattinson was a good choice to play Bruce Wayne.

But, as many readers of this newspaper are likely aware, this is not an absolute rule. Anyone who spends a lot of time in many different communities– especially since the advent of the internet and forum culture– will, at one point, encounter a disagreement between two communities more significant than a scheduling conflict, a cross-pollination of two incompatible groups, and be forced to choose one over the other. A particularly gut-wrenching example of this is the climax of the 1998 Danish film Idioterne, or The Idiots, directed by Lars Von Trier,1 of which I recently held a latenight, post-seminar screening with a group of friends.2

The central character of The Idiots is Stoffer, a young, mop-haired aspiring socialist with a taste for the profane, the obscene, and the pseudo-intellectual. He is the patriarch of the titular Idiots, a commune of middle-class Danes who all live together in a suburban home owned by Stoffer’s uncle. He is also the visionary who came up with the idea for the commune’s primary activity, which they call spassing3 and which I will euphemistically call performing for the remainder of this article. When they’re not sleeping on the floor4 or throwing parties for themselves, they go out to public places– including a public pool, a bar, and a restaurant– and pose as a group of developmentally disabled people, with one Idiot filling in as their “handler”. This is as upsetting to watch as it is to imagine, but the Idiots themselves, with rare exception, find it hilarious. Over the course of several sequences, which are both so offensive and so absurd that they provoked a curious kind of riotous, disdainful laughter among my friends during our screening, the Idiots use their perceived disabilities as license to do whatever obnoxious thing they please.

Stoffer in particular views this act not just as idle recreation, but as a bold, revolutionary statement, like a combination of performance art and civil disobedience– a way of striking back at a conformist society, man. Or at least that’s the justification he gives. In one pivotal scene, the commune is visited by a smartly-dressed member of the local housing council, whom (after asking him to use the battery of his car to provide one Idiot with impromptu

electro-shock therapy) Stoffer chases nude down the street,5 repeatedly calling him a “f*cking fascist”. This incident may provide evidence of some authentic conviction in Stoffer’s belief that he is some kind of forward-thinking iconoclast, although by the end of the film the more obvious conclusion is that Stoffer is merely a sadistic misanthrope who enjoys exerting dictatorial control over those around him, even if those around him are a handful of unlikable malcontents with nothing better to do all day than mock disabled people and eat caviar.

It’s pretty clear that, apart from Stoffer, none of the Idiots have any delusions that what they’re doing is at all important or brave, or anything more than just a bit of fun. During one of the documentary-style talking head interviews that appear intermittently throughout the film, one Idiot says that their activities were essentially treated like a game, though Stoffer wouldn’t see it that way. Indeed, when Stoffer isn’t ordering them around, we do see some moments where the Idiots seem to just be enjoying each other’s company. There are even moments of genuine romance between Idiots. Aside from its primary directive, the commune is, in several scenes, distantly comparable to a totally benign social club.

Up to a point, that is. This impression that the Idiots are just a group of friends hanging out together and occasionally doing something unconscionable does not last, and a little over halfway into the film something happens which reveals that the dynamic between the Idiots– more specifically, between the Idiots and Stoffer– is much more insidious and toxic than it first appeared. After the aforementioned nude car chase, the rest of the Idiots organize a party to cheer Stoffer up. At this party, when asked what he wants to do next, he utters a word which the viewer will hear at least thirty more times before the scene is over: gruppeknald. Or, in English: gangbang.

What follows is a six-minute6 scene of Stoffer and several of the other Idiots engaging in a variety of apparently unsimulated sexual acts which, combined with the cinéma vérité filming style and deliberate use of low-budget filming equipment, make the sequence feel just a little too much like actual amateur pornography.7 This was perhaps the most challenging part of my post-seminar screening, as the incredulous laughter and irreverent riffing which had been so instrumental in getting us through the film up to this point were suddenly nowhere to be found, and we were all forced to sit in silence for six minutes as Lars Von Trier abused his power as director and made us watch his dirty home movies.

Yet, despite the apparent crass artlessness of this scene, it ends up being one of the most important moments of the film. While the gruppeknald is going on in the main room of the house, two Idiots, Jeppe and Josephine, share a strikingly tender moment in one of the bedrooms, with Josephine suddenly “breaking character”8 and confessing to Jeppe that she loves him as they embrace. As Stoffer, like so many cult leaders before him, forces his followers to gratify his perverse desires, at the same time in another room a new, genuine love is consummated, and it is, despite itself, strangely beautiful. And then it is all torn away.

Not fifteen minutes later, Josephine’s father arrives at the commune, reprimands Josephine for not taking her pills, and drives her home, as Jeppe screams, cries, and pleads in one of the most arresting acting moments in the whole film. By now, the notion that this commune is just a group of regular people bonding over what happens to be a horribly insensitive hobby is forever cracked. These people are all damaged, we realize, and while they had previously shown indifference to the cruelty of their “performances”, we now see that this cruelty is not incidental to their activities– it’s the whole point.

In the next scene, Stoffer seeks to test the commitment of the Idiots by commanding them to go and “perform” in front of people they know. From this we learn that many of the Idiots have entire other lives which they’ve been neglecting in order to be a part of this commune, including one named Axel who apparently has a wife and a child. Something is deeply wrong in the lives of all of the Idiots, and in order to cope with their own dissatisfaction they mock a group of people whom they see as worse off than themselves, while at the same time bonding with others just as broken as they are. It is a kind of desperate, therapeutic cruelty. And at the center of it all is Stoffer, who, apart from an uncle whom he clearly doesn’t respect, doesn’t seem to have any family or life outside of being an Idiot. Being the leader of this strange, miserable little congregation is all he has to live for, and he lives out his sick power fantasy through them in order to cope with whatever made him the way he is.

There’s one character whom I haven’t mentioned yet: the protagonist, Karen. Karen joins the commune at the start of the film and acts as a kind of audience surrogate as the audience is introduced to the Idiots and their customs. She observes the antics of the Idiots, she criticizes Stoffer for mocking disabled people– though she’s apparently not offended enough by this to leave the commune– and, at one point, she sits on a windowsill and stares off into space, drooling and making infantile noises in an attempt to “perform” herself. Despite this effort, we never see Karen fully assimilate into the group, and she is clearly set apart from them to the viewer. Notably, she is much older than the rest of the Idiots, looking to be pushing forty while the rest of the commune are clearly in their twenties.

Karen’s role is not unlike that of Jane Goodall– living among the apes, adapting to their ways, and gaining their trust despite being fundamentally an outsider. She certainly enjoys the experience; while many of the other characters go through their own personal dramas, expressing their discontent with Stoffer and with each other, Karen spends her entire time in the commune with a blank, placid smile on her face, as though just being around these people has a calming, sedative effect on her. Near the end, when it is her turn to feign disability in front of people she knows, she tears up as she tells the rest of the group that she loves them more than she has ever loved anybody, and that “being an idiot with [them] is one of the best things [she’s] ever done.”

In the film’s final scene, Karen returns home after two weeks with the Idiots, and we learn that she has an entire family: her mother, her grandfather, her teenage daughter, and her husband, Anders, none of whom are happy to see her. As the mother somberly serves tea to Karen and Anders, Karen picks up a framed picture of an infant on a table. In the opening scene of the film, Karen left a restaurant to join Stoffer and the rest of the Idiots; we now learn that this happened the day before her child’s funeral. The vacant look and soft-spoken demeanor she’s had for the rest of the film now, in retrospect, seem less like contentment and more like shock.

Stoffer at one point describes being an Idiot as “a luxury”, but for Karen, it is a necessity. The cruelty of the commune is not what drew Karen in; being around the Idiots was, for her, not an opportunity to mock those below her, but to block out reality. But now that she has returned to her family– the first community most people have in their lives– reality cannot be avoided. In the final moments of the film, as Karen’s family eats in silence, seemingly unable to forgive her, she shuts her eyes, leans back in her chair, and lets food dribble out of her mouth, “performing” right in front of her loved ones. Anders immediately hops up from his seat, winds back his hand, and smacks her across the face so hard that blood drips down her chin.

The film ends here. We are not shown explicitly whether Karen will attempt to heal her relationship with her family, or go right back to being an Idiot. But it is clear that she cannot do both; these two communities9 are fundamentally incompatible. As the credits roll, we are shown brief clips of the Idiots performing once more, while Karen stands with her back turned to the camera, staring off into the distance. And we are reminded that, no matter how abusive and miserable this commune of Idiots is, it is all but certain that she will return. It is now the only community where she is welcome– and the only one to which she cares to belong.

Notes

(1) Due to The Idiots being part of the “Dogme 95” film movement (which I don’t intend to discuss here), crediting Von Trier as the director is discouraged, but the film’s Dogme-ness is virtually irrelevant to this article, and frankly I don’t like the idea of letting Von Trier evade responsibility for the creation of this film.

(2) Let it be known that neither I nor The Gadfly condone the practice of screening The Idiots for your friends, coworkers, prayer group, or any other community to which you may belong, unless you’re no longer interested in being a part of that community.

(3) The Danish equivalent of the ableist English term “spazzing”. The fact that this is the word these characters use to describe their favorite hobby should be all the characterization they need.

(4) Bewilderingly, the Idiots sleep in sleeping bags in spite of the house having several perfectly good beds, which are only ever used for tying Stoffer down during a fit of hysteria and during the film’s climactic gruppeknald sequence– more on that later.

(5) Leading to the aforementioned tying of Stoffer to one of the house’s aforementioned beds.

(6) Though it feels like sixty.

(7) The grotesquerie of this scene is exacerbated, it should be mentioned, by the fact that the party which the other Idiots organize for Stoffer resembles a low-budget children’s birthday party in both aesthetics and general atmosphere. Hairy, slapping flesh is juxtaposed with scribbled crayon drawings, colorful balloons evidently inflated with breath rather than helium, and paper streamers. The effect is profoundly unsettling in ways which I fear to articulate in print. To cap it all off, miniature Danish flags are taped haphazardly to the walls and are present in the majority of shots, lending the sequence a bizarrely patriotic angle. After viewing this scene, Lars Von Trier will forever be known in my personal vernacular as "the Dane". Sorry, Hamlet.

(8) i.e., no longer pretending to be disabled. the Gadfly / πόλις / May 13, 2022

(9) That is, her family and the Idiots.