8 minute read

Wollstonecraft on Equity

Wollstonecraft on Virtue and Equity

By Luke Briner

Advertisement

In her Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Wollstonecraft sets out to discover what has grounded the inequality of the sexes and what that ground has consisted in throughout history. In her attempt to answer these questions, she begins by setting down some preliminary principles concerning reason and virtue in general:

In what does man’s pre-eminence over the brute creation consist? The answer is as clear as that a half is less than the whole; in Reason. What acquirement exalts one being above another? Virtue; we spontaneously reply. For what purpose were the passions implanted? That man by struggling with them might attain a degree of knowledge denied to the brutes; whispers Experience. Consequently the perfection of our nature and capability of happiness, must be estimated by the degree of reason, virtue, and knowledge, that distinguish the individual, and direct the laws which bind society: and that from the exercise of reason, knowledge and virtue naturally flow, is equally undeniable, if mankind be viewed collectively. (p. 11)

If human beings are naturally preeminent due to their capacity to reason, and if their excellence is found in virtue, then our virtue depends precisely upon the exercise of our reason, since “it is a farce to call any being virtuous whose virtues do not result from the exercise of its own reason” (p. 21). If the virtues that we possess are merely incidental, that is, not proceeding from willful and rational determination, then they are in fact not rightly called virtues at all.

But if our excellence, our worthiness consists in our virtue, and if virtue is itself necessarily founded on the possession and exercise of our reason, then it follows that if women have an equal possession of reason to men, they will also have an equal capacity to participate in virtue, and thus in a general human excellence. Since women do possess the same inborn capacity for reason that men do (p. 20), and since the reason that serves as the foundation of virtue is itself uniform, it follows that there is a single, universal standard of virtue that both men and women are subject to, or that simply exists beyond the distinction between men and women to begin with:

I see not the shadow of a reason to conclude that their virtues should differ in respect to their nature. In fact, how can they, if virtue has only one eternal standard?

I must therefore, if I reason consequentially, as strenuously maintain that they have the same simple direction, as that there is a God. (p. 27)

In face of the unitary nature of virtue, and thereby the basic equality of men and women on the basis of their shared possession of the rational faculty, the inequality that has existed between men and women appears to us as even more nonsensical and egregious. “Who,” Wollstonecraft asks, “made man the exclusive judge, if woman partake with him the gift of reason?” (p. 4). Since the natural capacities of men and women for reason and virtue are fundamentally one and equal, the social inequality that women have historically suffered, must be basically unnatural, must be something artificially imposed from without. Although she admits that a “degree of physical superiority cannot… be denied” in the male sex (p. 7), this is “the only solid basis on which the superiority of the sex can be built” (p. 40). The general subordination of women over men might be justified if we did not possess a rational faculty and were thus no different from wild animals, but it is precisely because human pre-eminence consists principally in reason rather than brute physical strength that such a subordination of cannot be justified simply on that basis. Any systemic social inequality between the sexes that goes beyond the inherent difference in physical strength must be something cannot, therefore, be explained or defended as “natural”; thus, Wollstonecraft remarks that, “not content with this natural preeminence, men endeavour to sink us [women] still lower” (p. 7).

Women, in fact, have thus sunk lower due to their own kind of exceptional physical quality; unfortunately, this is simply their sex appeal to men. Seen by men only as objects of sensual pleasure, women are accordingly “taught from their infancy that beauty is woman’s sceptre” (p. 46); their mind, consequently, “shapes itself to the body, and, roaming round its gilt cage, only seeks to adorn its prison” (ibid). In order to reflect and reinforce this sentiment, men have relegated women to an education that teaches them to attend to subordinate, sensual, and strictly practical duties rather than the duties that would genuinely exercise their sovereign reason or edify their souls. In being kept to this kind of education, women are kept in their subservient social position not only by a general lack of knowledge, but also by the artificial distinction made between “masculine” and “feminine” virtues which is reinforced externally by men and internally by women themselves, rendered in such a way ignorant of even this artifice.

To combat this artificial inequality, Wollstonecraft deems it necessary to reject this binary conception of virtue and return to the natural, uniform one which patriarchal society has deviated from. She thus exhorts women to acquire those qualities that have previously been conceived of as belonging only to men, and thereby to break free from the petty femininity that only reinforces their subservience:

I am aware of an obvious inference:- from every quarter have I heard exclamations against masculine women… but if it be against the imitation of manly virtues, or, more properly speaking, the attainment of those talents and virtues, the exercise of which ennobles the human character, and which raise females in the scale of animal being, when they are comprehensively termed mankind;- all those who view them with a philosophic eye must, I should think, wish with me, that they may every day grow more and more masculine. (p. 9) Since virtue is one and universal, and since all people as rational beings have the capacity to attain it, then there is no justification for the relegation of the sexes to different moral norms, or for respecting one sex’s capacity for virtue and excellence while preventing the other from even endeavoring toward the same. Wollstonecraft ventures even further than this, however, and points toward the transcendence of the very binary of sex that has served as the basis of this inequality in the first place: A wild wish has just flown from my heart to my head…I do earnestly wish to see the distinction of sex confounded in society, unless where love animates the behaviour. For this distinction is, I am firmly persuaded, the foundation of the weakness of character ascribed to woman; is the cause why the understanding is neglected, whilst accomplishments are acquired with sedulous care: and the same cause accounts for their preferring the graceful before the heroic virtues. (p. 60) “Mary Wollstonecraft” by John Opie Since distinct social and moral norms men and women are arbitrary and have served to perpetuate the subservience of one sex to another, the very notions of “man” and “woman” must themselves contain something artificial, unnatural, invented. Wollstonecraft hints at this when she observes that men have developed the habit of “considering females rather as women than human creatures” (p. 6), acknowledging the distinction between the mere biological realities of the female sex, independent of the many extraneous assumptions and impositions that have been put upon it, and the socially-constructed idea of “woman” that has in fact alienated women from being simply and fully human.

Education is continually on Wollstonecraft’s mind, and her emphasis on its importance for womens’ political, intellectual, and moral equity spans from the beginning to the end of her Vindication. “My argument,” she sets out, “is that if she [woman] be not prepared by education to become the companion of man, she will stop the progress of knowledge and virtue; for truth must be common to all, or it will be inefficacious with respect to its influence on general practice” (p. 3). This companionship we aim for, as opposed to the turbulent and degenerate inequality that has thus far defined the relations of men and women, can be achieved by instructing men and women in common, and with a common subject matter. By educating everyone equally and without any regard for sex, we are alike exercised in our sovereign capacity for reason, thus granting us all the opportunity to rise to that “universal standard” (p. 27) of virtue. Moreover, in having each sex embrace, in their recognition of the unitary nature of virtue, the virtues previously withheld to the other, or, better yet, discard outright the arbitrary polarity between “masculinity” and “femininity,” we will be far closer to being able to live with other not as enemies in a bitter hierarchical struggle, but as friends and simply fellow human beings. “Let,” therefore, “an enlightened nation then try what effect reason would have to bring them back to nature, and their duty; and allowing them to share the advantages of education and government with man, see whether they will become better, as they grow wiser and become free.” (p. 178).

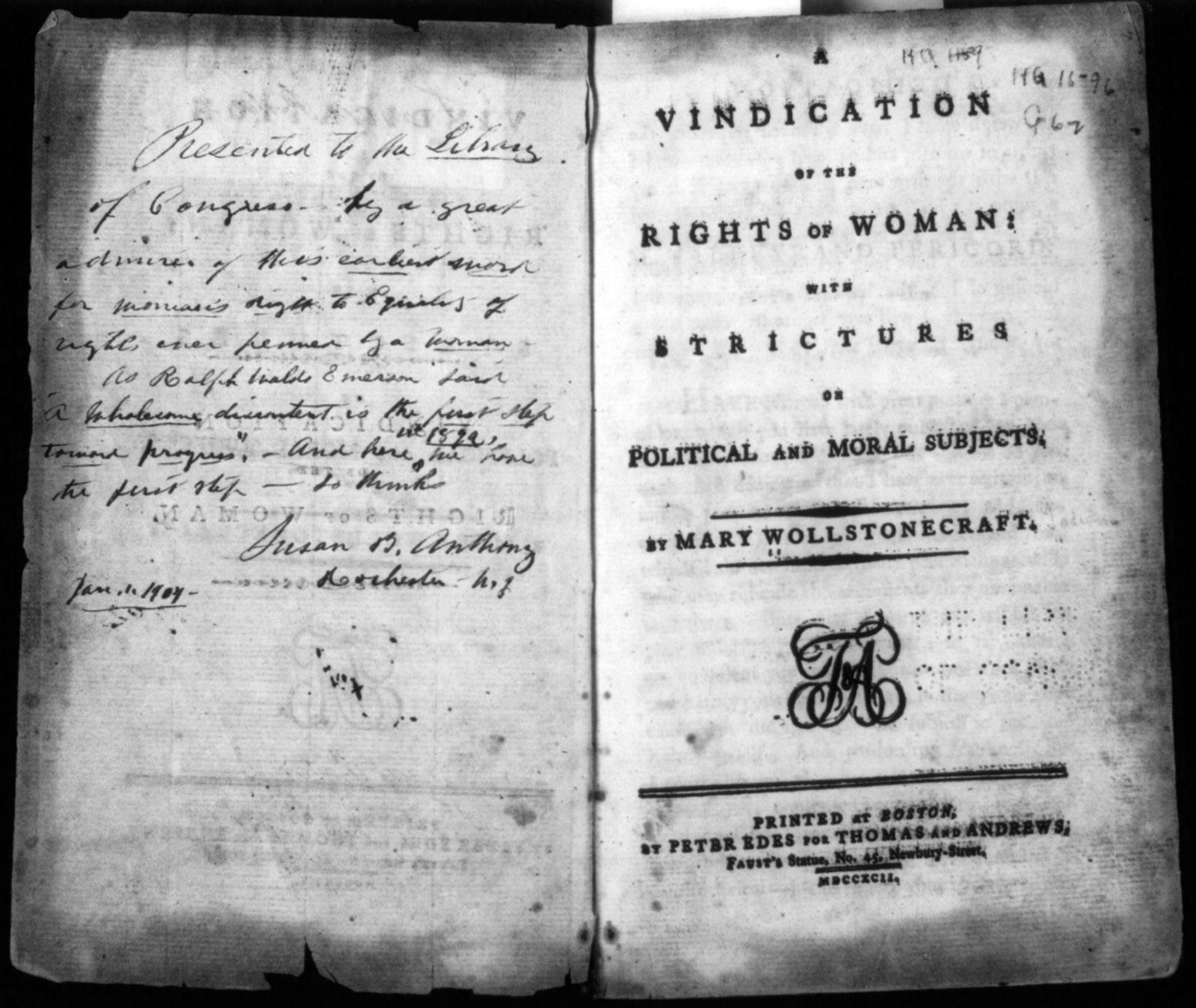

Title page of A Vindication with inscription by Susan B. Anthony on facing page