ZANDER BLOM MONOCHROME PAINTINGS

I have been promiscuous as a painter over the last decade, changing style and technique often. The monochrome works started as a fling, a love affair with a method of painting that revealed itself in the studio one day. The new flame took over my life, kicking everything else out, as many infatuations had done before. I was so attracted to this new manner of painting because it immediately suggested a combination of techniques that would make a very specific type of monochrome abstract painting achievable – hyper flat, sharp and scalable, with great possibilities for three-dimensional illusion, and an almost photographic, digital quality in terms of grain and gradients. The process dictates that a painting be done in a fashion akin to action painting, working quickly, using your whole body – a mode of painting that suits my temperament.

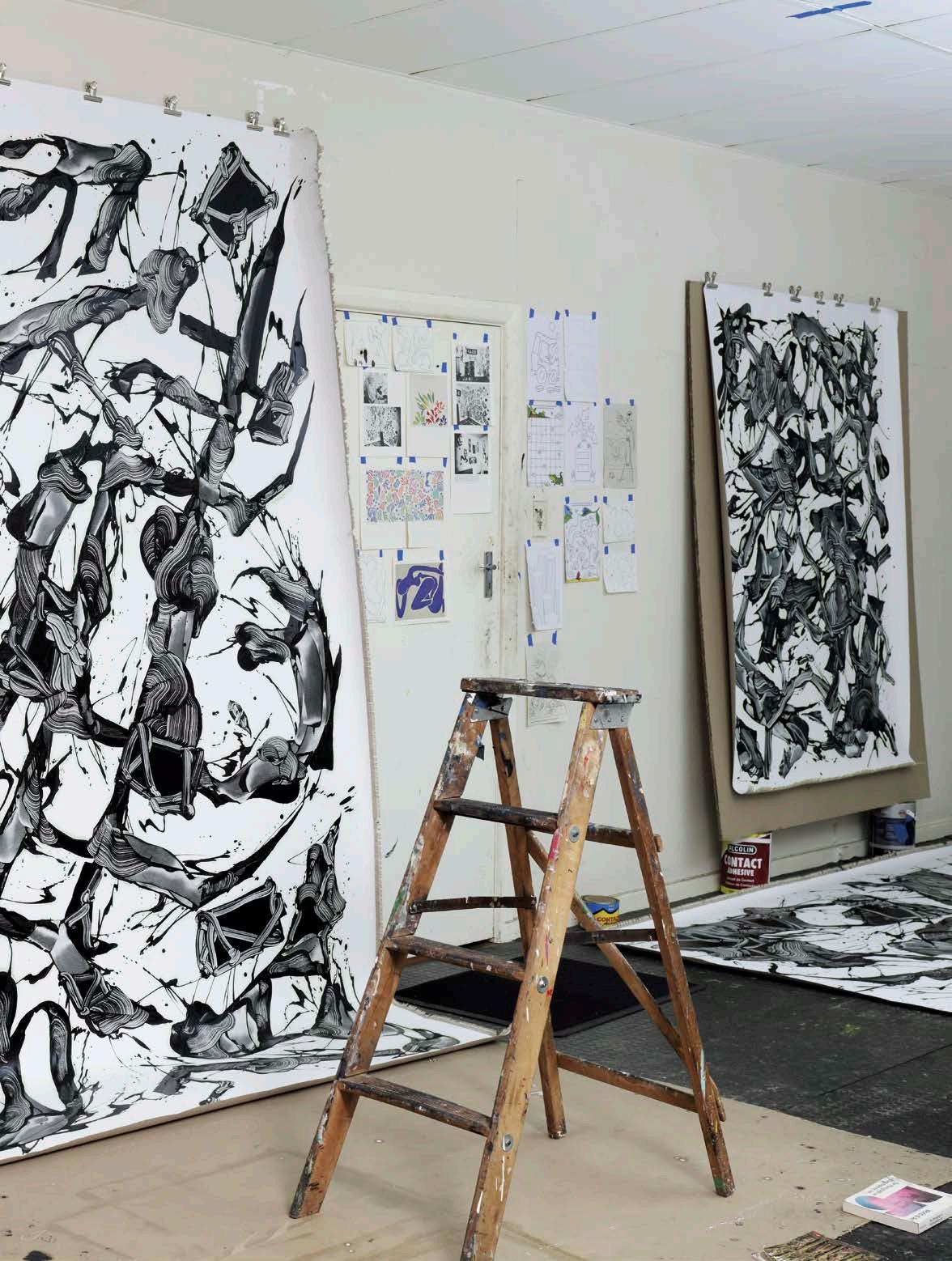

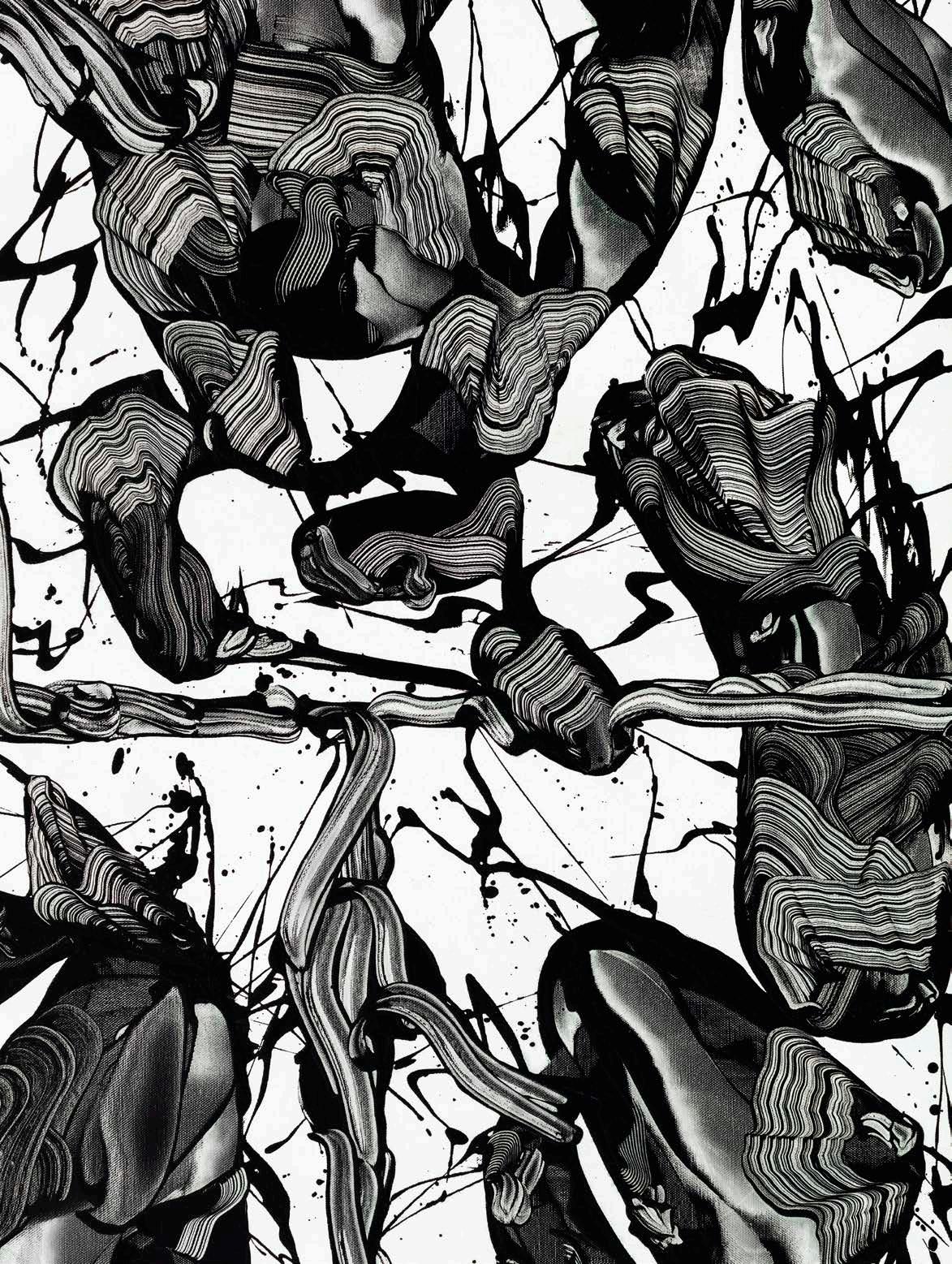

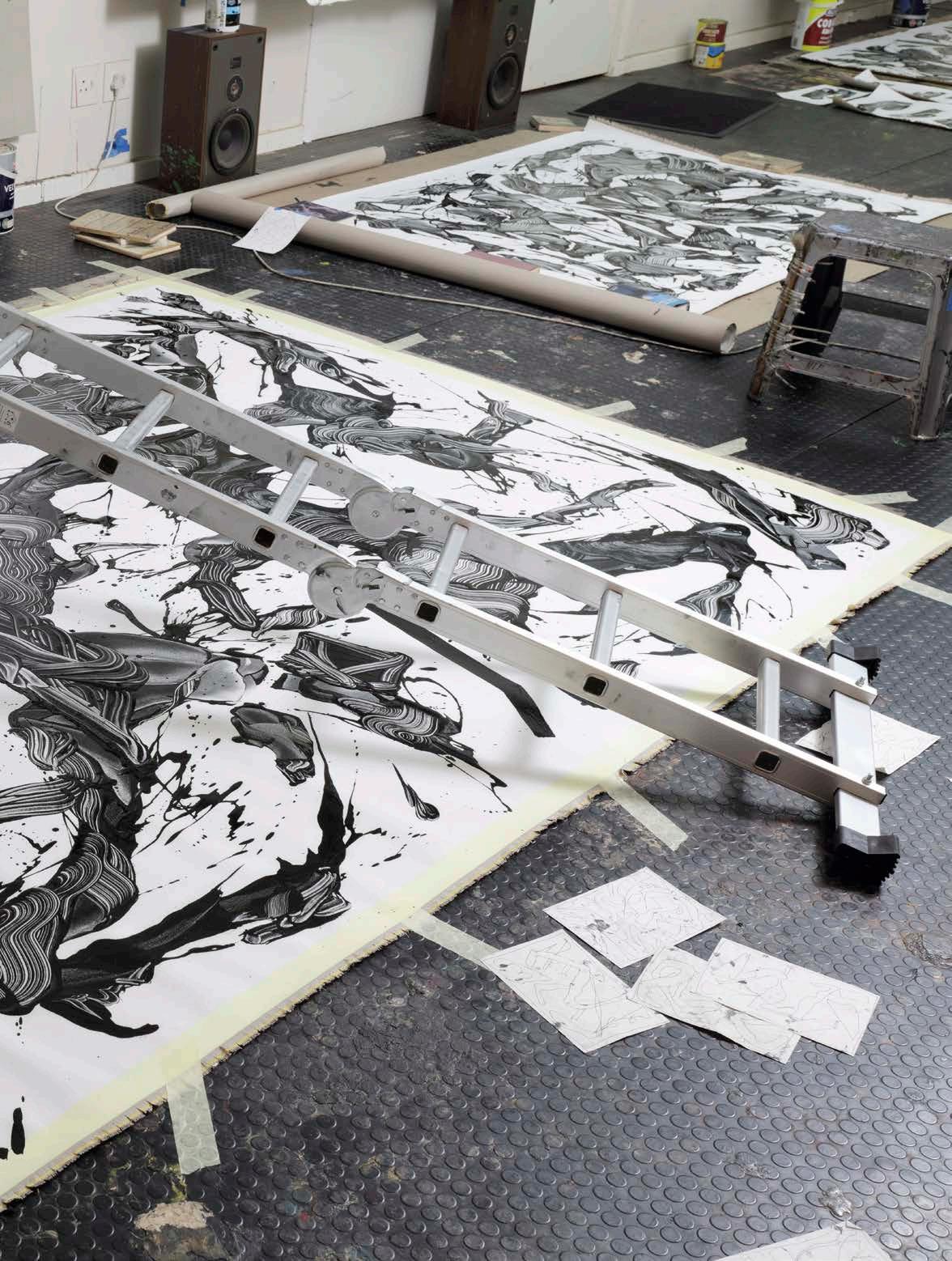

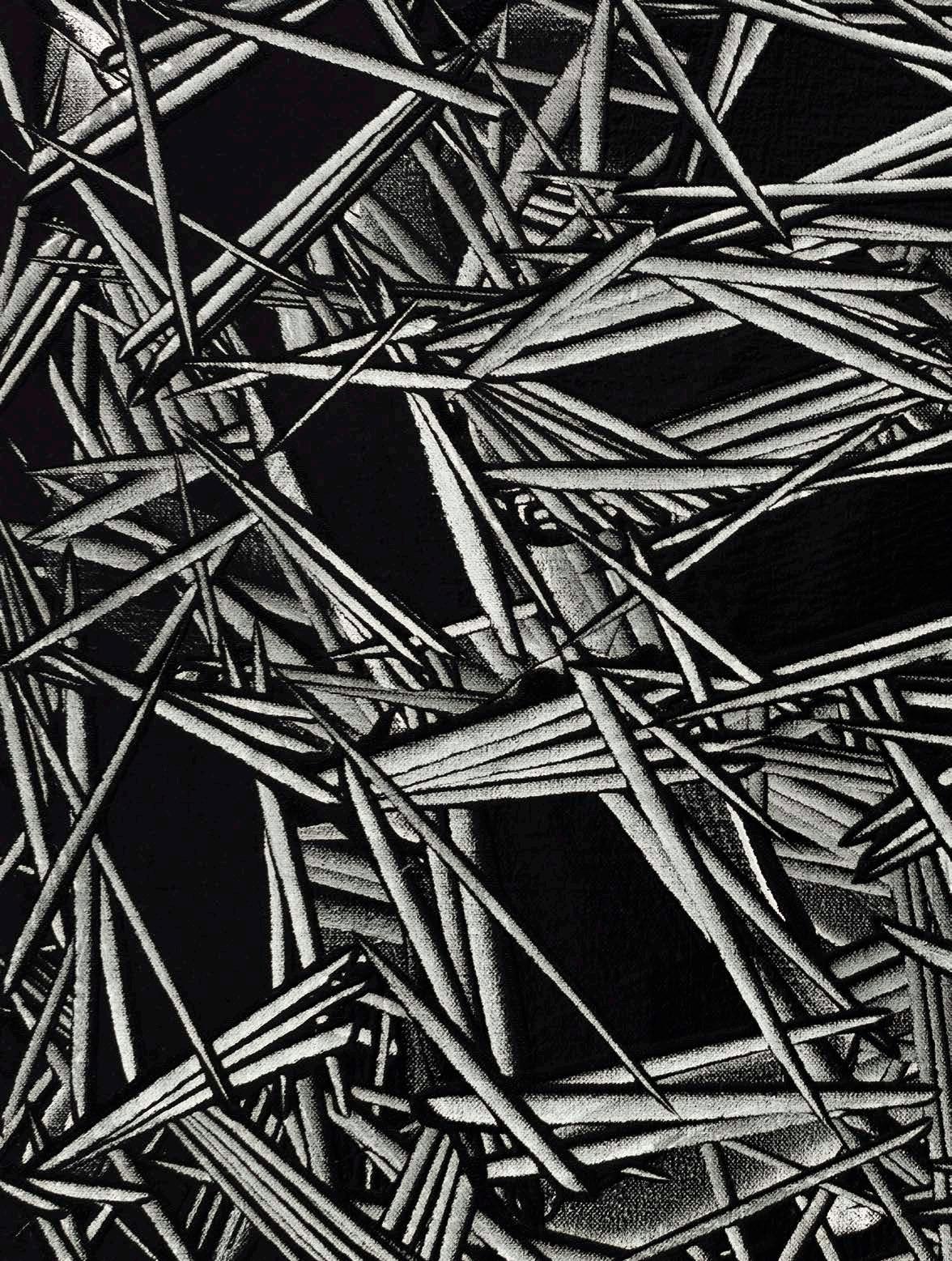

The basic method is as follows: paint black shapes in oil with brushes on unstretched white-acrylic-primed linen, flat on the floor or table. Then work into the shape/s with rubber, steel and (especially) silicone tools while the paint is wet. This is the core of the trick, the technique that enables the illusionistic mark-making. These tools bring back the white surface of the canvas to varying degrees, each with different effect, and each subtle change in the movement or

pressure of the hand re-invents the effect of the tools. It’s a subtractive process that almost feels like sculpting or painting with light.

This moment in my journey with painting has been somewhat of a homecoming. The fling turned into a long-term relationship. I’ve worked with this process for over two years now and I don’t see an end on the horizon. When I started out as a young artist in the early 2000s I was working in monochrome because of limited funds as well as a fascination with stripping things down to the bare essentials. Back then I worked mostly with ink on paper, printmaking and later photography (which was also mostly heavily desaturated). Since I began painting with oil on canvas, around 2010, I’ve only returned to monochrome for short bouts of time, as a way to gather strength and find clarity, but never for very long.

So why is this? Why have I stuck with this method instead of jumping into the next exciting direction, trying to be every artist I’ve ever been interested in at the same time? This monogamous moment has become about daring myself to stay the same after many years of almost predictable and consistent change. Yet it was not simply born from a desire to remain anchored in one place. It has to do with the possibilities that the current method offers. It allows me to do things with compositions and forms that simply weren’t possible for me in the early years. It has enabled me to return to fundamental interests, immovable impulses, armed with much more advanced techniques, better technology if you will. It’s startling to look at ink and paper

works from the early 2000s and see how forms and compositions have re-emerged. Many of those drawings look like they could be primitive studies for the new work. I also haven’t grown tired of starting a painting simply to see what will happen, where it will go. Whenever I’ve thought the end was looming, I’ve been surprised the next day by my own excitement at the effect of some new tool, a subtle change in composition or new choice of silhouette.

I am aware that there is seemingly a lot of repetition. People in my orbit have expressed that many of these works look very similar, and I don’t disagree. What fascinates me is that this doesn’t bother me – for the first time in my life. I used to want a show of paintings to consist of a lot of variation in colour, scale, mark-making, etc. Like Picasso or Matisse. But now a room with ten paintings of the same size with iterations of the same thing sounds perfectly fine to me. Better even. Take Warhol’s Shadows or Josh Smith’s Reapers, for example. In terms of making the work, I am still obsessed with finding tiny refinements and technical innovations within this narrow monochrome method. I’m not feverishly looking towards the next thing. Maybe I’m also just calming down a bit (having recently turned 40), but I feel that I owe it to this method to really dig deep for all that it has to offer me.

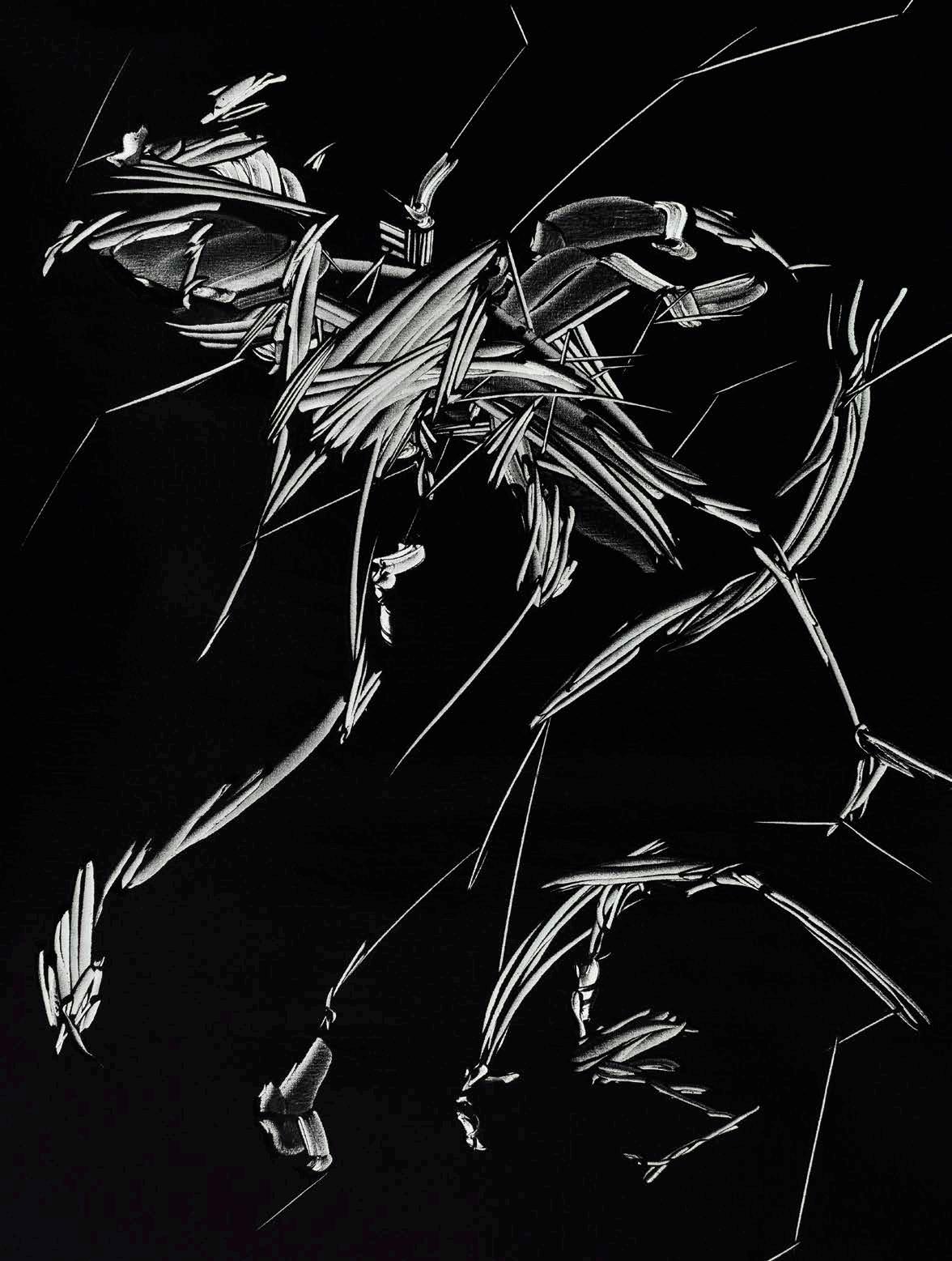

In the new works the forms can be seductive and joyful yet dark and menacing; they sit on top of the canvas twisting and turning, other times they recede into an abyss where space seems to collapse in on itself. Some compositions feel like portals, others like gilded

baroque gates, cages or fences. Some doff their caps to minimalism and futurism while others flirt with the decorative. These pictures are open in the sense that they never settle into recognisable forms, yet they aren’t simply abstract elements arranged to please the eye. They often seem to be tangible ‘things’ or images of events in time and space, perhaps just not from our world. For the most part there is nothing subtle or understated about them. They are not hazy, far away or out of focus. They are sharp and crisp. They announce themselves with confidence, yet what are they? What do they say? What language do they speak? Are they silent or do they scream? Do they even have a sound? Are they moving fast, hurtling through space, or are they perfectly still? I don’t exactly know what they are or mean but they fascinate me. I’m drawn to making them and I like to look at them. What combinations of line, texture and form invoke what kind of emotional response or visual interpretation – and how does our own time, knowledge and experience affect those perceptions? What combination makes an image that is compelling to look at? And why is one thing dead and another alive?

It seems that I want to make limb-like forms that writhe around. I want to give them sharp menacing tendrils, and little pitchblack portals going who-knows-where. I must want to see big pools of black darkness filled with fragmentary lines and unrecognisable shapes colliding. I want them to feel organic, warm, soft, weirdly familiar, sensuous, elastic, natural, alive, sentient, inviting, yet also

technological, hard, cold, angular, jagged, foreign, unsympathetic, threatening – this is what this particular painting method wants to do, what it’s good at, what it brings out of me, and in that sense I’m in alignment with the possibilities of the method. These must be the kind of things that I want to pour out onto the canvas at this time, and paintings like these will likely continue to crawl out of the studio until the alignment goes out of sync.

Every kind of technique comes with its own rules of engagement and parameters. All the new works have to be done in one sitting. From the moment you start a composition you only have a couple of hours before the paint settles, and then it can’t be worked into anymore. It’s like writing an exam. So I have to be prepared, rested and ready. This means I have to pace myself. You can’t write a two to eight hour exam every day – you’ll burn out or get resentful towards your work.

I have to watch myself now. I have to get my head straight or wait out anxiety before starting a painting. Some days I’ll go to the gym or for a run on the mountain if I’m not feeling ready. Often I can sense that I’m in a destructive obsessive mood, then nothing I do will be good enough. From experience I’ve learned that in this state I’ll make marks just for the sake of making marks. I’ll end up destroying whatever I do, because I’ll be in a place where I won’t be able to see and assess what is happening on the canvas, I won’t be able to zoom out, notice the bigger picture, the whole composition. I’ll just obsess

over small details and keep working the same areas over and over, hoping for better/different results until the whole thing is just one big overworked mess.

The more minimal works need restraint and it follows that these tend to be my favourites. I often pat myself on the back if I’m able to let something simple or elegant survive. I’ve lost beautiful compositions by going too far, so when things are flowing I try not to ask too many questions. An effortless moment is a real gift, because the next obstacle is always just around the corner.

Although the parameters of limited time and not being able to layer work can often be exhausting and stressful, this suits me better than the reverse. If I work in a way in which you can keep going in, keep making changes, then I can never stop. If anything is possible at any time, nothing becomes possible. I’ll just paint painting on top of painting on top of painting, never satisfied.

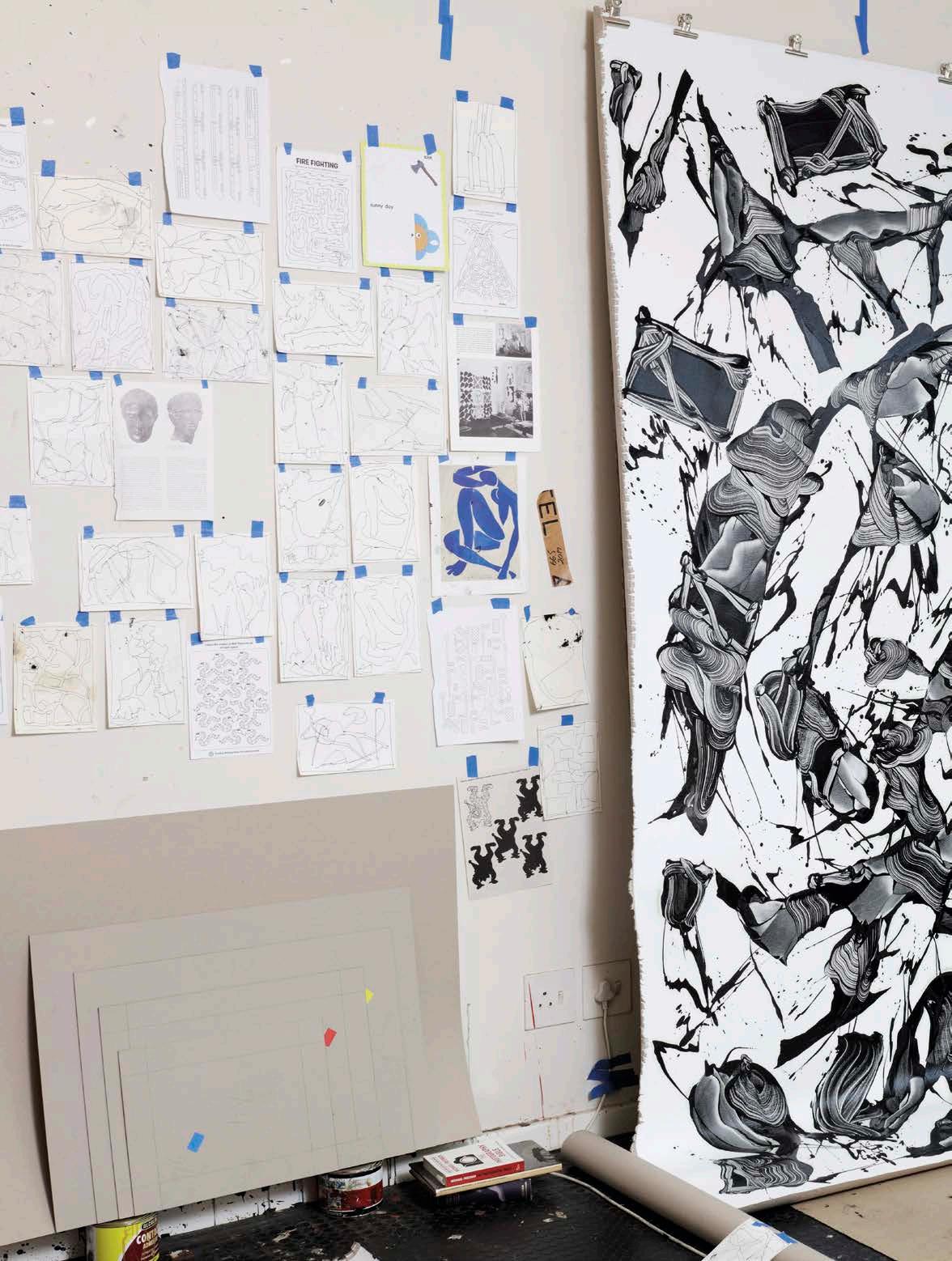

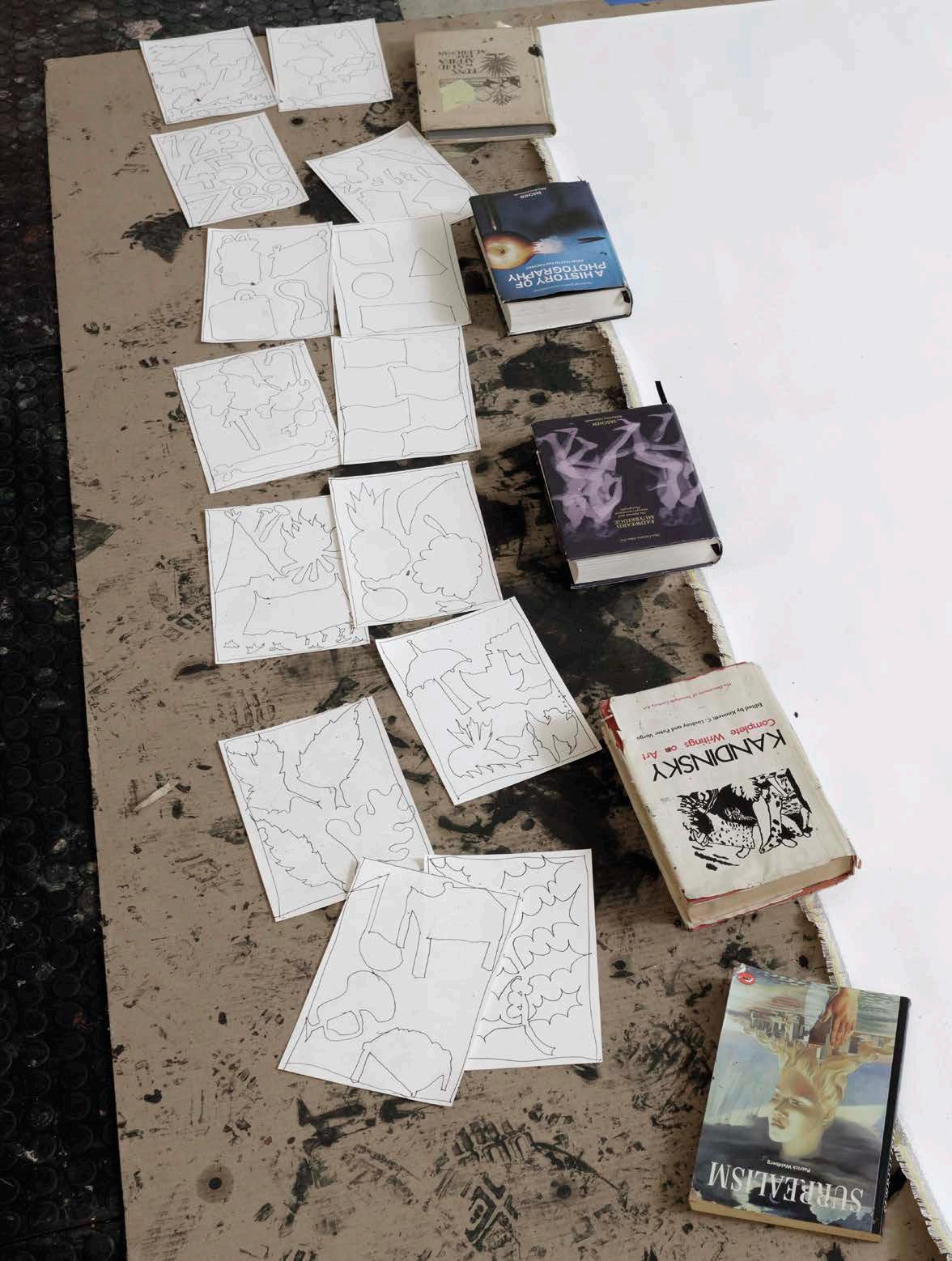

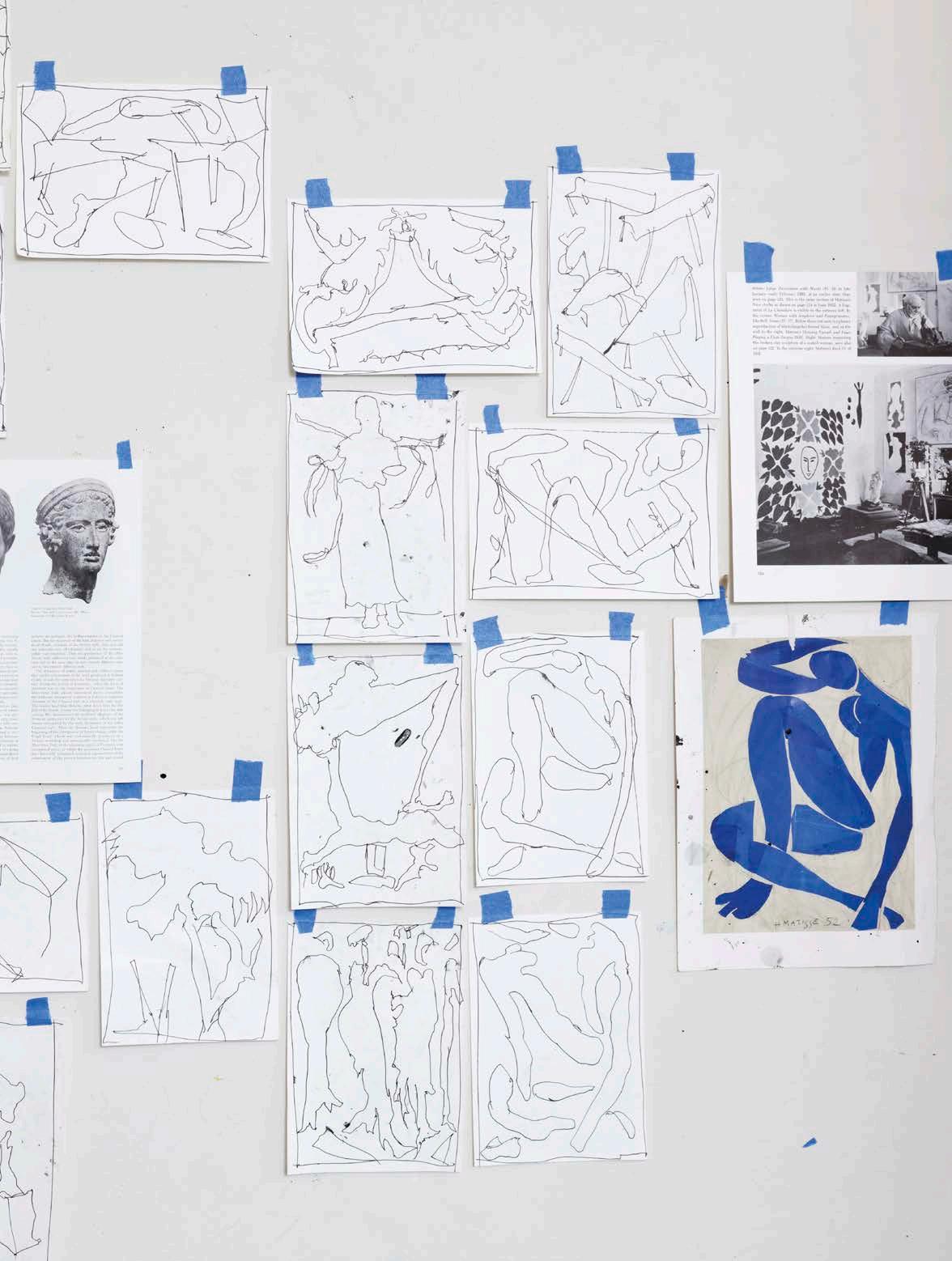

This mode entails quite a bit of prep work which keeps me happily busy too. A lot of my time is spent drawing endless sketches that serve as potential starting points for paintings. I hunt through various references for interesting silhouettes that I can bend and distort. Surprisingly I’ve found the line drawings in children’s colouring, educational

and games/task books to be a wonderful and deep well for strange and unexpected arrangements of form. Once I’ve made a loose and distorted sketch of the reference, I don’t look back at it again. Then from the sketch I draw the outline/silhouette very lightly with charcoal on the canvas. Here things get distorted again and another step removed. So by the time I get to a finished painting it will be almost unrecognisable from the original source. This process is about creating a scenario where I can go in with confidence and commit to certain forms when I begin, just to have a little bit of direction. Once you have this basic form down you can start manipulating and twisting it to your will. Often I’ll have a big empty canvas lying on the floor for days, brooding over how to start, deciding on a reference and then at the last minute choosing something completely different.

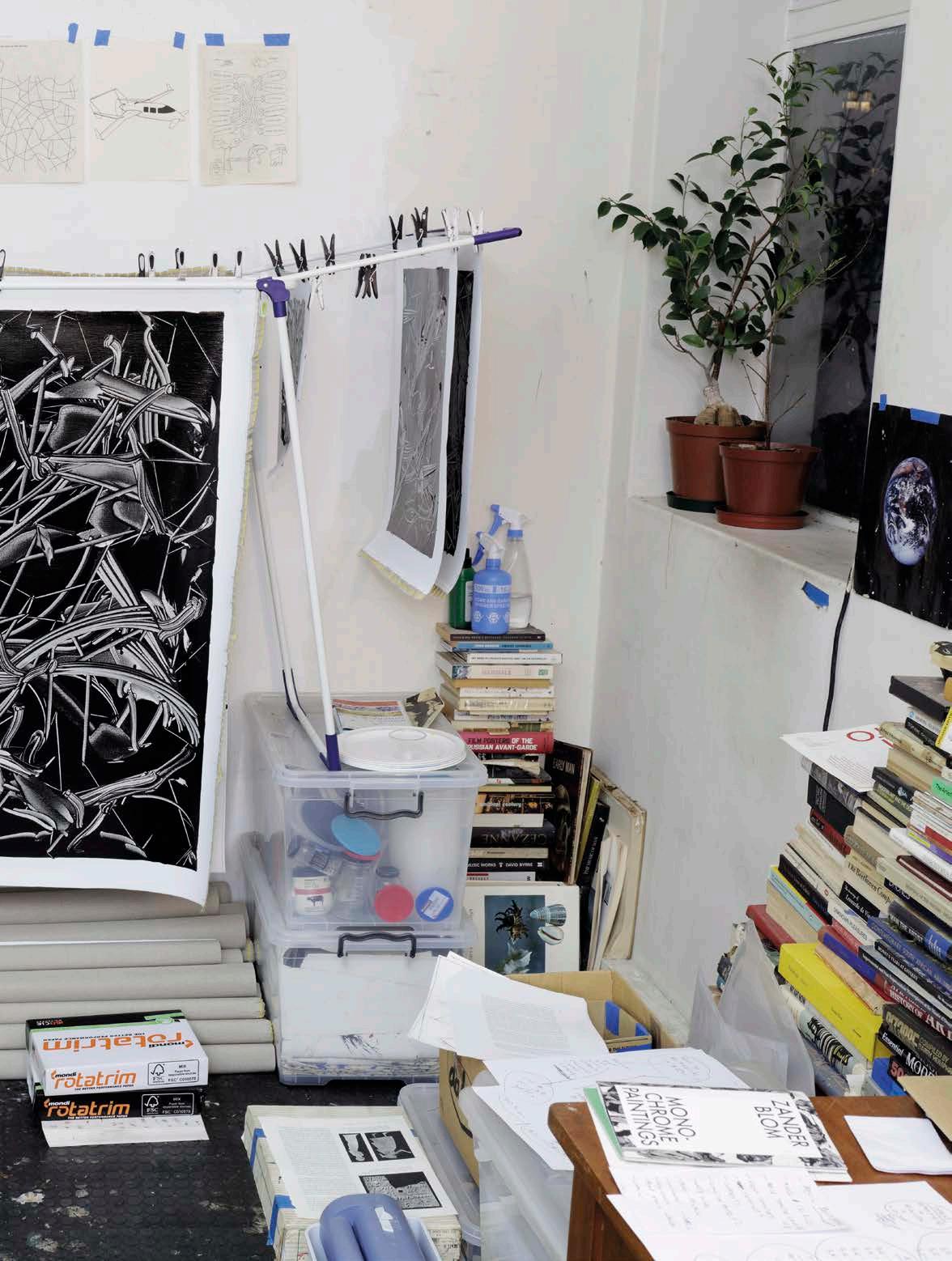

The works that have a black background are approached a little bit differently. Here my sketches determine even less of how the form will settle; they are more about getting a feeling for the handling of line and shape before diving in.

A lot of time is spent mixing oil paint to get just the right mix of blue, brown and black, together with linseed oil and turpentine. The goal is to have something with a rich tone, that has enough linseed oil and turpentine in it, to enable light gradients

to be sculpted out of the black pools of paint. The tools essentially function as erasers that reveal the original white surface of the linen.

I’ve realised that choice of medium and materials can be half if not more of the battle. Every combination of materials and techniques has things that it can do happily and things that it stubbornly refuses to, no matter how hard you try. The materials and techniques I’m using today are great for this very specific type of painting. But I can’t expect to make beautiful colour field paintings using the same method. For that I’ll have to rearrange the studio, change materials and develop a whole new process.

Many frustrating moments in my practice have been the result of expecting more from a medium or technique than was in its nature. I would often look at a painting and think ‘this is just dead paint on dead paint, why can’t I get this object to sing?’ And that was exactly the problem. I wasn’t really thinking about the object, about the materiality of things. I was not thinking about the fact that I was working with unimaginative materials, lukewarm techniques and very little experience – expecting miracles to happen. Materials and techniques are technologies that enable you to do certain things. For example, without a huge amount of linseed oil these monochrome paintings would be impossible. The linseed oil stops the black paint from immediately being sucked into the surface of the canvas, thus allowing me to bring back light gradients from out of the black shapes. Nor can I work on a standard primed cotton duck canvas because the combination of gesso

on cotton duck produces a surface that is very porous. I have to use a universal-acrylic-primed linen from Belgium because the surface of this particular canvas is so smooth and plasticky that it allows me to work into the black for a couple of hours before the paint starts to settle. Even the slight difference between the primers on the Belgian linen and a similar Italian linen makes the latter useless for my purposes – it’s too chalky. And if we were living in a time when the proliferation of silicone utensils for the home had not happened yet, I might never have stumbled onto this technique to begin with. All sorts of little things like this come together to make something a practical possibility.

Making and testing tools is a fun part of the job. I’m regularly in homeware stores looking for new silicone utensils to alter for my purposes. Some of them end up looking very curious, but sadly the coolest looking tools have turned out to give the least effective results. I also spend some time curating and laying out selections of tools, in the order of their intended use, before starting a work. There are many options, and you can get lost if you don’t have some kind of loose strategy before you start. Once a work is finished everything has to be cleaned with buckets of turpentine immediately. This is a nice ritual for unwinding after a long exam.

Let’s wrap up by returning to the late 1990s and early 2000s for a moment. During art school I turned into a hyper-critical and ambitious little wannabe artist, consuming the latest art magazines and books. I encountered the contemporary art world through these publications

and fell in love with this subculture. Here people took things very, very seriously, from the pristine white cube exhibition spaces to the slick layouts of the publications filled with highbrow language. I desperately wanted to be part of that world. It made me feel like I was in on something that normal people from my world just couldn’t understand. It was also around that time that I discovered philosophers like Nietzsche, Sartre, Derrida, Foucault – the popular philosophers of the time. Not that I read much of it. Nietzsche was kinda fun in his arrogance and disdain for his predecessors, but I couldn’t make it through any of the books by the others. I mostly read the blurbs on the back. I mean, have you tried to read Being and Nothingness cover to cover? Good luck. Regardless, all of this seemed to go well with monochrome black and white. For some reason it made me feel like I could be a little desaturated soldier of contemporary art. I could be part of something.

At this point in my early twenties my work and also my wardrobe turned black. I stopped buying colourful clothes; eventually even the occasional blue jeans and white shirt disappeared. When my studio couch fell apart I got it re-upholstered in black. I bought black bedsheets for my single mattress, and I drove a little black Nissan 1400 bakkie. I worked almost exclusively with black ink on paper. I had made a choice. It was a practical choice but admittedly also a style choice. It was a soft rebellion and it was vaguely ideological. It was about control and about saying no, about rejection. It wasn’t a performance, but it might have looked like one from the outside.

Monochrome was somehow tied up in my head with being a serious artist; there was a resoluteness, even a sombreness to it. And at least I was taking some kind of position – I couldn’t think of any other suitable option. I was trying to find my own way, my own language, and I went completely in the opposite direction to my mother – who painted with all the colours in the rainbow, decorated the house with thousands of colourful objects – painted stars on the ceilings, murals everywhere, every wall of the house a different colour.

Monochrome was also tied to modernism in my mind. It was form-follows-function, no added frills or decoration. Colour didn’t seem serious and would often later pitch up in my paintings denoting humour. I also saw modernism as an alibi, a way to be apolitical, to escape the dominant narratives in South African art. It was a safe blanket that I could wrap myself in. My declarations of unpacking and critiquing modernism were a little half-baked. It was an obvious post-modern move, and already dated. I was hellbent on being taken seriously, and having my efforts directed into a serious contemporary art context, but I was really just an ambitious young man putting the cart before the horse. I’m reminded of the line from Macbeth: ‘full of sound and fury, signifying nothing…’ Nevertheless, it helped me find a starting point, however cringeworthy it might look in retrospect.

I abandoned that strategy eventually and embraced painting in an abstract idiom with no ideological excuses. But in the ensuing years I’ve felt a kind of nagging shame for being an artist in the 21st century

who makes mostly abstract paintings without any real conceptual or political agenda. There’s been a voice in the back of my head that kept saying, ‘This is not enough, you should be more.’ I’ve found all sorts of ways to justify why I’ve been drawn to abstraction. But I just don’t care anymore. I like to make marks on a surface and then respond with successive marks, in order to solve a composition. I don’t like going into something knowing the exact outcome. And I tend not to be satisfied with paintings that settle into recognisable forms. I also simply enjoy working in monochrome. These are aspects of my temperament that I’ve made peace with.

I’ve come to understand that things tend to sort themselves out in the studio – by making and looking, playing and critiquing. I still don’t think I have anything to say as an artist in the way that I expected from myself when I was younger. But I’ve realised that that way of thinking about art just doesn’t serve me, nor does it have to.

Recently I’ve been asking myself questions like: What are you at your immovable core? What are your inherent strengths? What do you inevitably return to? How can you accept yourself and push the boundaries forward in terms of what is possible for you, with your particular set of strengths and limitations? How can you get out of your own way and just be a natural animal?

I feel like I’m making some progress in this direction. But who knows? This is also all just a story that I’m telling myself. Tomorrow, I’ll tell myself another freshly revised version. And on and on it goes.