CURRICULUM VITAE

PERSONALIA

EDUCATION

SPORTS

LANGUAGES

COMPUTER SKILLS

NAME

Nicola Stevens

DATE OF BIRTH

1 december, 1999

PLACE OF BIRTH

Sint-Niklaas

PLACE OF RESIDENCE

NATIONALITY

Belgium CONTACT

M nicola.stevens49@gmail.com

£

MASTER ARCHITECTURE / 2017 - 2022 University of Antwerp, Belgium

ARCHITECTURE SUMMER SCHOOL / 2021

Porto Academy, Portugal

MASTER HERITAGE STUDIES / 2022 - 2024

University of Antwerp, Belgium

SWIMMING / 2005 - 2012 Competitive

JUDO / 2005 -

First dan black belt judoka & teacher

Member of the Flemish Judo Federation Competitive

DUTCH

ENGLISH

FRENCH

ITALIAN

REVIT

PHOTOSHOP

INDESIGN

ILLUSTRATOR

SKETCHUP

QGIS

INVENTOR

Mother language excellent decent intermediate*

*I’ve tackled 4 extra university courses in Applied Linguistics for Italian during my second master’s year in heritage studies, racking up over 400 learning hours of Italian.

If you like it and you understand it, then it’s yours.

Matthew McConaughey

MY JOURNEY THROUGH ARCHITECTURE...

Childhood aspirations.

Growing up as a kid, my yearly family trips to Italy introduced me to the wonders of Italian culture, especially its classicist and Renaissance-Baroque architecture. This early exposure to la grande bellezza would later spark my passion for architecture and set the course to pursue it as a university degree.

Master architecture: Architectural design. (Designer)

My initial years in architecture taught me the essentials of designing buildings from scratch. My growing fascination with historical buildings, fueled by childhood interests and readings from Venturi, Scarpa, Märkli, and Vitruvius, shaped my approach to incorporating historical insights into contemporary, innovative designs. The postmodern model coupled with the Preesistenze Ambientali principle became my main design approach. Having gotten (too) comfortable with the postmodern model, Olgiati’s non-referential world inspired me to challenge my current design approaches during my master years, aiming for purely architectonic designs free from extra-architectural influences. This quest gave me a final push towards discovering my creative limits as a designer. As I finalized my studies, my longstanding yet unexplored interest in historical buildings compelled me to pursue an additional two-year Master’s in heritage studies. Wanting to combine my passion for architectural design and interest in heritage, I would put my focus on adaptive reuse during these studies.

Master heritage studies: Building research. (Researcher)

During my first master year in heritage studies, I learned how to conduct architectural history research to deconstruct and understand the complex layers that define a building’s current meaning. This was a crucial step for me towards adaptive reuse, where being able to understand and listen to a building is invaluable.

Master Heritage studies: Bridging the gap. (Design through research)

To effectively revitalize old buildings, merging architectural innovation with a building’s existing qualities is essential. A challenge not fully mastered yet in adaptive reuse, in my humble opinion. Contemporary architects often disregard a building’s inherent values by claiming ownership with overpowering modern designs, whereas restorers lack the balls and creativity to intervene, overly prioritizing historical layers at the expense of innovation. I thereby focused my second year on this integration, aiming to bridge the gap between designer and restorer.

Practical Applications and goals.

Now that I have finalized my studies, my goal is to apply these skills in a real-world setting, actively seeking opportunities to balance scholarly insight with handson architectural practice. A crucial blend, as scholarly knowledge alone can’t transform theory into structure, nor can craftsmanship demand the same amount of respect without a deep understanding of scholarly architectural principles.

About my skills.

While my core competencies extend beyond technical tools, I work exceptionally well with Autodesk Revit and am strongly proficient in all major Adobe programs, skills I independently developed to enhance my architectural research and visualizations. Additionally, my adeptness with computers makes me highly efficient and adaptable to learning any new programs etc.

ARCHITECTURE

ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN / 2017 - 2022

1. URBAN LIVING / 2020

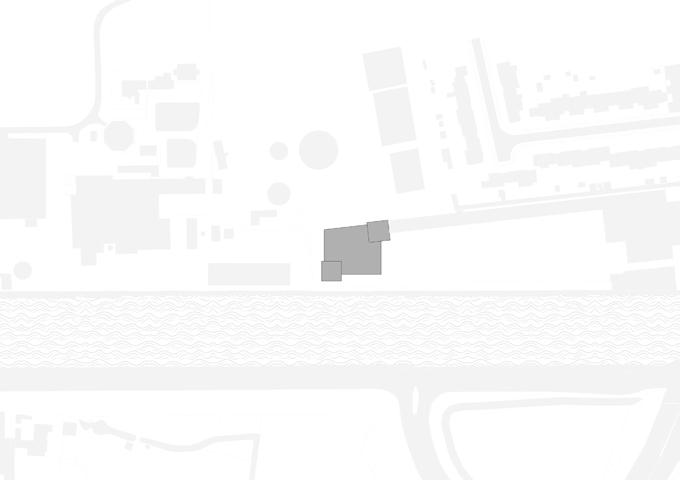

Radical Ensembles, Antwerp

2. STRUCTURE / 2019

Art academy, Zwevegem

3. DESIGN RESEARCH / 2020

Strandvejskvarteret, Copenhagen

Corner building corner, Φ

4. PURISM OF FORM / 2021

3. DESIGN RESEARCH / 2021 San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, Rome

4. PURISM OF FORM / 2022 High-Rise, Film

: Most defining w orks of the portfolio

5.

7.

BUILDING RESEARCH 2022 - 2023 HERITAGE

BRIDGING THE GAP 2023- 2024 HERITAGE

TO BE CONTINUED 2025NEXT PHASE

HISTORICAL RESEARCH / 2022 Schaliën house, Nieuwkerken-Waas

6. THESIS / 2023 - 2024 Industrial heritage of OVERSIZE

5. HISTORICAL RESEARCH / 2024 Flemish beguinages, Flanders

COMPETITION / 2023 - 2024 Saving Kortrijk railway station, 1st prize

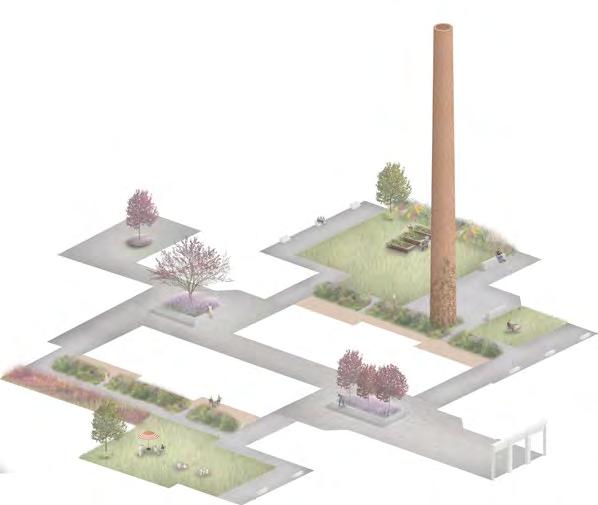

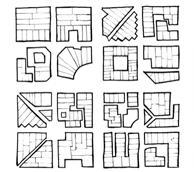

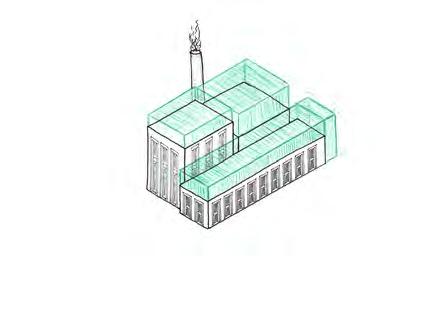

1. ARCHITECTURE - URBAN LIVING / 2020

A demolished factory in Antwerp has left behind only a chimney and an open void in the urban fabric of a residential area. A gaping void in need of revitalization through reimagination. This project reimagines the space as a colony for living by redefining the European building block through the creation of a 'radical ensemble' of residences. How this redefining unfolds is left entirely to the designer's vision, opening the door to bold and creative interpretations.

PROJECT TEAM

Helen Geens

Miriam Herst

Nicola Stevens

Patricia de la Bustos Torres

Ferdinand Coosemansstraat MY RESPONSIBILITIES

Built - Unbuilt concept

Concrete panel rowhouse Cladding (group effort)

Entrance design of building types

3D models & -axonometries

3D Rendering & -Photoshop

Eikelstraat

CUL DE SAC

Drawing on the cul-de-sac principle, the design establishes a clear spatial hierarchy, leading individuals from public spaces through semi-public areas and into private zones, all without physical barriers. The central passageway branches out into squares that function as distinct zones, creating a natural flow. Inspired by organic city layouts of ancient times, this principle reduces movement choices and directs individuals through intermediate spaces, which fosters security and order. This organization ensures privacy within the residential areas, while also encouraging social interaction. As residents move through the various spaces, they naturally engage in surveillance, taking responsibility for the communal areas and strengthening their connection with the neighborhood.

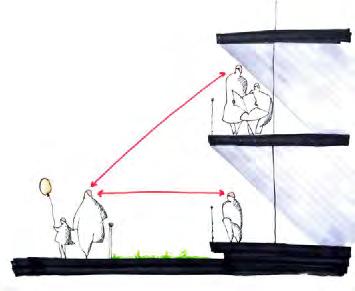

MOMENTS OF INTERACTION

Further drawing inspiriation from organic development, by adding various sizes of built/ unbuilt, a symmetrical centre with asymmetrical branching and public/ private areas, all within a respected hierarchy, a complexity within the colony ensues where various moments of interaction emerge for people to gather or retreat to.

Coosemansstraat

Eikelstraat

A sense of privacy and security by the cul-de-sac: One can only get to D by passing through A, B & C.

One of the central squares where residences meet. One can pass through or delve deeper into the maze.

Inside the central courtyard, a local retreat with residents having a VIP view to all moments of interaction.

CLADDING & STRUCTURE

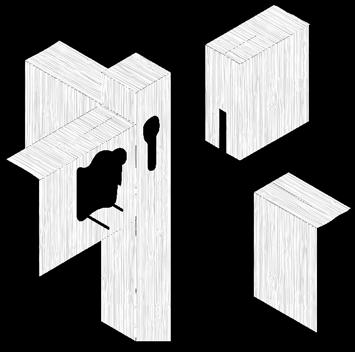

Three main structural types are used to form the ensemble, each designed to accommodate varying sizes, positions, and residential types. The facade cladding remains consistent across all structures, following the preesistente ambientali principle, with subtle variations in its application to highlight the specific structure it houses.

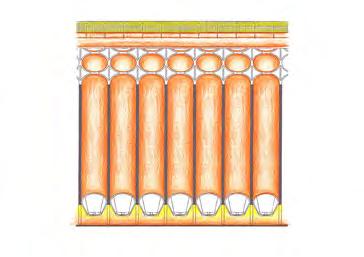

I. CONCRETE PANEL ROWHOUSE

STRUCTURES

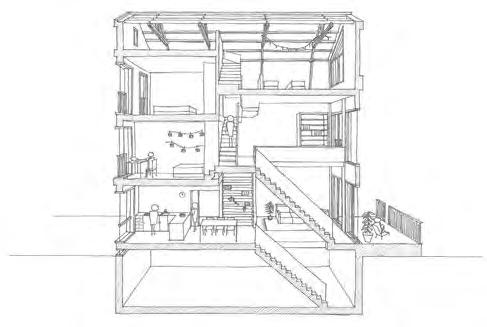

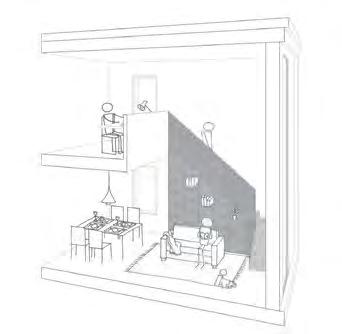

Derived from the traditional row house, this type uses concrete panels for an open-plan layout, maximizing light, views and controlled interaction to both the street and inner courtyard. It features a basement, an open ground-floor living area, and a gable roof with an attic. Split levels offer private spaces for children, ensuring a balance of openness and privacy in the family.

II. CO(RE) HOUSING

This type features concrete cores that support surrounding slabs, creating an entirely open floor plan. The cores function as circulation oe private living units, while the free slabs offer flexible space usage. A design ideal for cohousing, providing affordable and spacious living options for young people and recent graduates, with solid cores offering privacy within shared spaces.

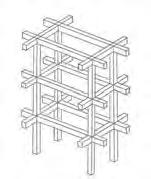

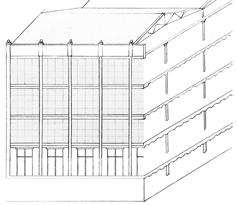

III. TRANSPARENT GRID DUPLEX

This type features a skeleton structure that offers spacious living for diverse residents. The open-plan layout allows for double-height duplex rooms and terraces with views to both the passageways and central courtyard. A more comfortable residence for various living manners that fosters interaction between private and public spaces within the colony.

GRID

GRID

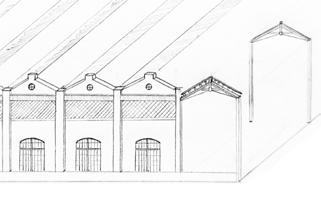

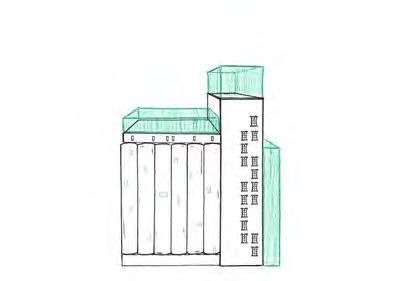

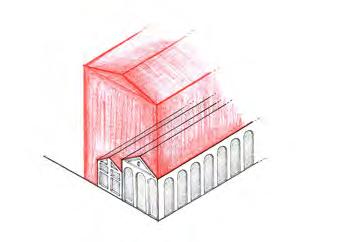

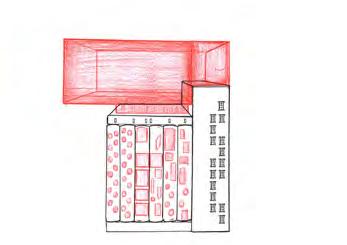

2. ARCHITECTURE - STRUCTURE / 2019

The Transfo industrial site in Zwevegem, once home to the Transfo power plant and La Flandre textile factory, is undergoing revitalization to reestablish its role as a vibrant part of the municipality. Beyond the adaptive reuse of existing structures, the site will feature a newly designed art academy to host functions such as ateliers, library, theatre, exhibitions, classrooms etc. The academy aims to strengthen the community's cultural and educational landscape.

distinct role in ensuring adaptability and sustainability. The primary structure is a robust, independent framework formed by columns, which supports the roof and acts as an outer shell of the building. This shell, constructed with CLT (crosslaminated timber) and laminated beams, allows for large spans of up to 10 meters. Inside this primary structure, the secondary system is built, consisting of flexible and replaceable components that can be easily adjusted or replaced in the future. This modular approach ensures that the building can evolve over time, as the secondary structure can be adapted or reconfigured for different functions while the primary shell remains intact. The third structure consists of two towers, designed with vertical continuity in mind, using a stacked construction system for high-rise expansion while maintaining flexibility in its layout.

PROJECT TEAM

Nicola Stevens Royd Goolaerts

MY RESPONSIBILITIES

Structure (group effort)

Design & Layout (group effort)

All 3D models & digital imagery

Second floor + structural layout

A central entrance hall surrounded by ateliers and other art functions, two towers for classrooms & education

2. ARCHITECTURE - STRUCTURE / 2020

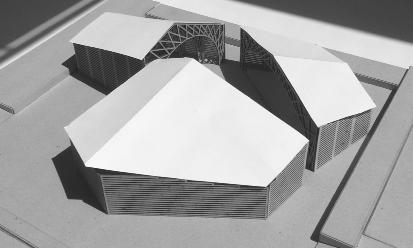

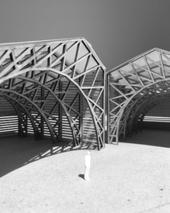

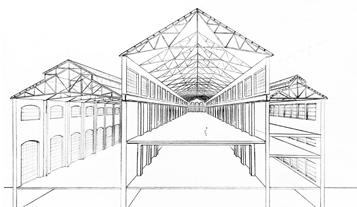

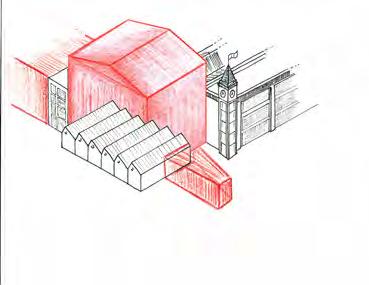

At the MAS museum square in Antwerp, a temporary hall is planned to host various cultural events, contributing to the port’s transformation into a vibrant cultural hub. Each design team is assigned a specific structural system, emphasizing demountability to align with the hall's temporary nature. In this case, trusses have been assigned as structure, one that can be used in however way deemed fit to design a striking and adaptable venue at the square.

their straight lined use. Typically used as a singular spaced shed, we explore this hidden versatility to design a concert hall with trusses of many heights and sizes, forms and spaces. By warping a traditional grid into perspective, the trusses following the grid can be fine-tuned into nonconventional forms, deviating from its traditional use for spatial richness.

TRUSSES OF INTIMACY

By varying the form, height and length of the trusses, we shape the space into moments of intimacy and interaction. The layout of the trusses is manipulated to create areas that invite both gathering and retreat. These diverse truss forms embody flexible spaces, where visitors can engage one another or find a quiet spot. The result, a dynamic environment that encourages social connection and a variety of activities.

MY RESPONSIBILITIES

Concept design & layout

Structural design (group effort)

All 3D models & digital imagery

3. ARCHITECTURE - DESIGN RESEARCH/ 2020

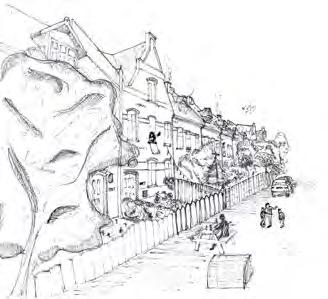

Denmark is renowned for its forward-thinking architecture and urban design, hosting residential projects in diverse forms. At first glance, Strandvejskvarteret appears to be an unremarkable, repetitive neighborhood, similar to many across Europe. Yet upon closer inspection, it reveals a quality of life and charm, transforming it into an enviable place to live. What makes this neighborhood stand out? How does it achieve what others fail to deliver?

CASTRUM ORGANIC ORDER

Unlike many linear, repetitive neighborhoods, this layout reflects the principles of both organic order and a Roman castrum, similar to traditional European cities. A clear hierarchy is established, with a symmetrical center branching into smaller streets where houses slightly vary in form and appearance. While all buildings follow a shared building code, subtle variations in design foster individual authenticity, while still maintaining the overall uniformity and cohesion of the ensemble.

SCALING HIERARCHY

Strandvejskvarteret's residential blocks adopt a trinity-based scaling hierarchy that connects the largescale block to its smallest elements. This approach divides the building into three distinct parts, fostering a sense of orientation and belonging. The hierarchy extends further within each building, with individual rowhouses scaled to approximately 6 meters wide, maintaining the connection to the overall 100m length. This division extends throughout each building, starting with the plinth, corpus, and corona. The variations in windows, doorways, lintels, and brickwork further scale this division down to the individual brick. This intermediate scaling unites the smallest brick to the entire block, bringing the whole building block down to human scale.

SHAPING THE NEIGHBORHOOD

Residents of Strandvejskvarteret were given the freedom to shape their own outdoor spaces and modify elements like doors and windows, infusing personal touches while maintaining the overall morphology of the buildings. This autonomy in design created distinct identities for each block, enriching the streetscape and fostering a stronger sense of community and connection.

Representation of a residential building block facade.

Allowing residents to shape their buildings within a shared morphological framework enriches the streetscape with unique character and identity while maintaining a collective whole.

3. ARCHITECTURE - DESIGN RESEARCH/ 2020

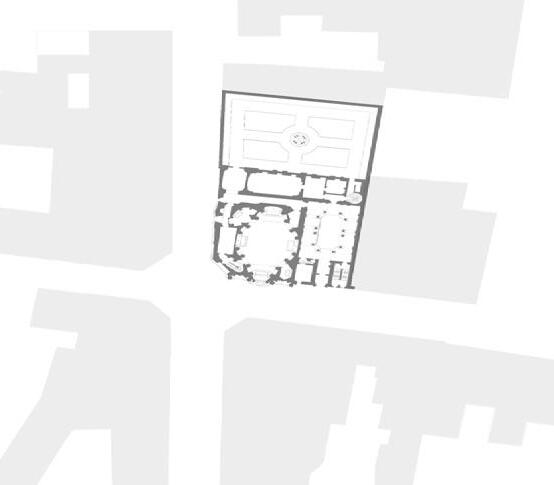

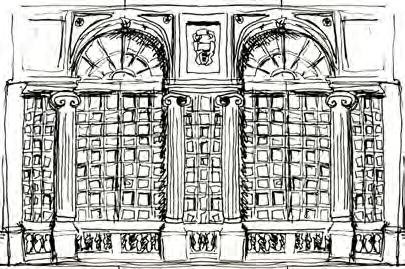

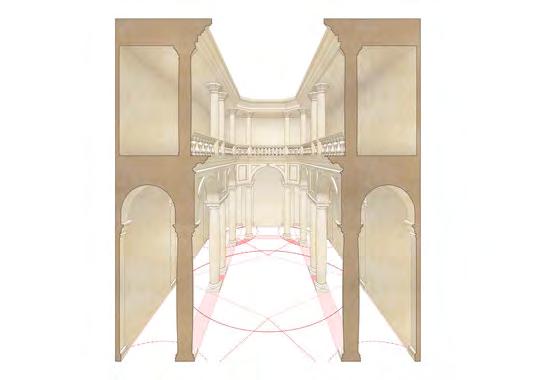

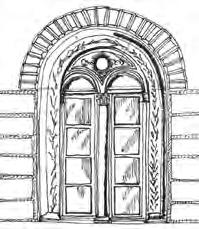

San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, designed by Francesco Borromini in 1638, is a Baroque masterpiece in Rome. Known for its dynamic forms and intricate geometry, the church showcases Borromini’s innovative architectural approach. This research examines the step-by-step process behind its design, focusing on how brilliantly the plan layout, spatial organization and architectural elements came about to create the eventual building.

San Carlino exemplifies the nihil addi principle—nothing added. Every element of the church is derived from an intricate geometrical plan, ensuring coherence and unity from the ground up. The church plan originates from the tre et uno assieme foundation: two equilateral triangles sharing one side, forming the basis for the church’s build. This precise geometry allows all components, from the layout to ornamental details, to emerge naturally from the scheme.

SERLIANA

OVERLAPPING SERLIANE

Geometrical plan studies w/ imagery

All

SERLIANA

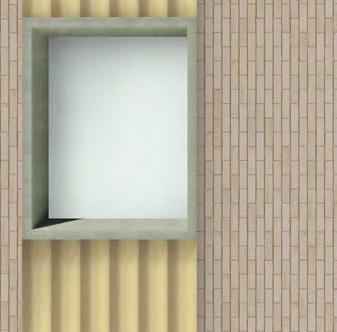

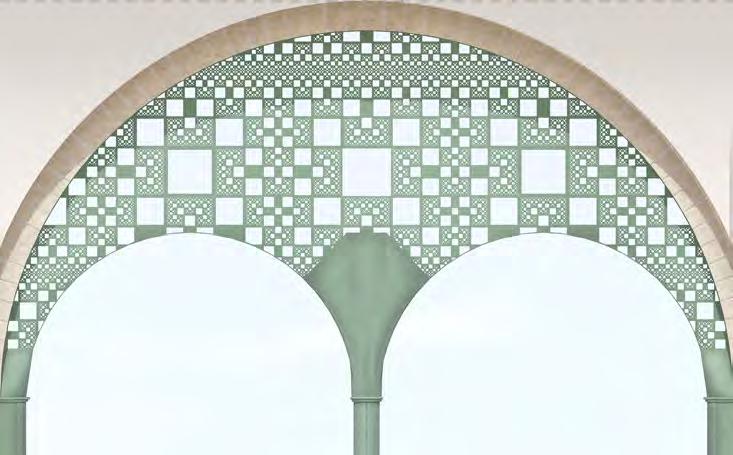

The serliana, introduced by Palladio, is a classical architectural motif consisting of a central arched opening flanked by two rectangular openings. Borromini reimagined this two-dimensional window into a threedimensional architectural element. In San Carlino, overlapping serlianas enclose the building, integrating seamlessly with its geometric plan. This transforms a static, isolated motif into a dynamic form generating a spatial continuation.

INNER COURTYARD PLAN

The inner courtyard perfectly adheres to Borromini's nihil addi principle, using 3:2 ratios & 45° angles as a geometrical foundation to mold into architectural space. This plan produces an enclosed arcade of overlapping serliane, embracing an open central courtyard. The same ratio governs the continuous façade, uniting horizontal & vertical elements. A design that achieves absolute precision, ensuring every aspect of the space is perfectly placed.

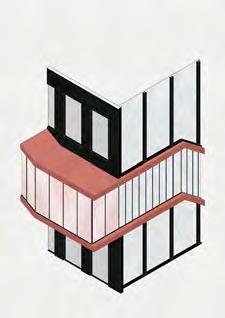

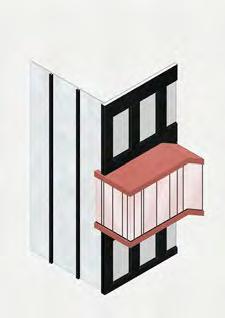

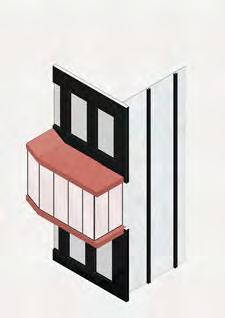

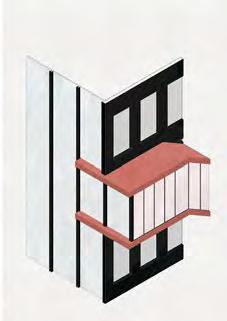

4. ARCHITECTURE - PURISM OF FORM / 2021

This assignment required us to design a building corner. Before starting, we had to study a corner from an existing building, which would inform our own design later. Our chosen case study was San Carlino, with Borromini's serliana serving as a major inspiration for our corner design approach.

SERLIANA / BIFORA

The initial inspiration for our case study came from the corner façade of San Carlino. What truly captivated us however was Borromini’s innovative use of the serliana as a continuous spatial element through overlapping corners. This discovery pushed us to rethink the idea of corner windows. We chose the bifora, a window type popular during the Romanesque and Gothic eras, characterized by two vertical openings divided by a central mullion. Reinterpreting the bifora, we would try and envision it as a threedimensional architectural feature, transforming it from a flat ornamental element into an active spatial corner form, inspired by Borromini’s mastery of spatial continuity and geometry.

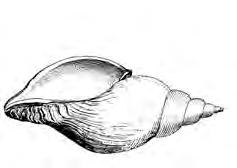

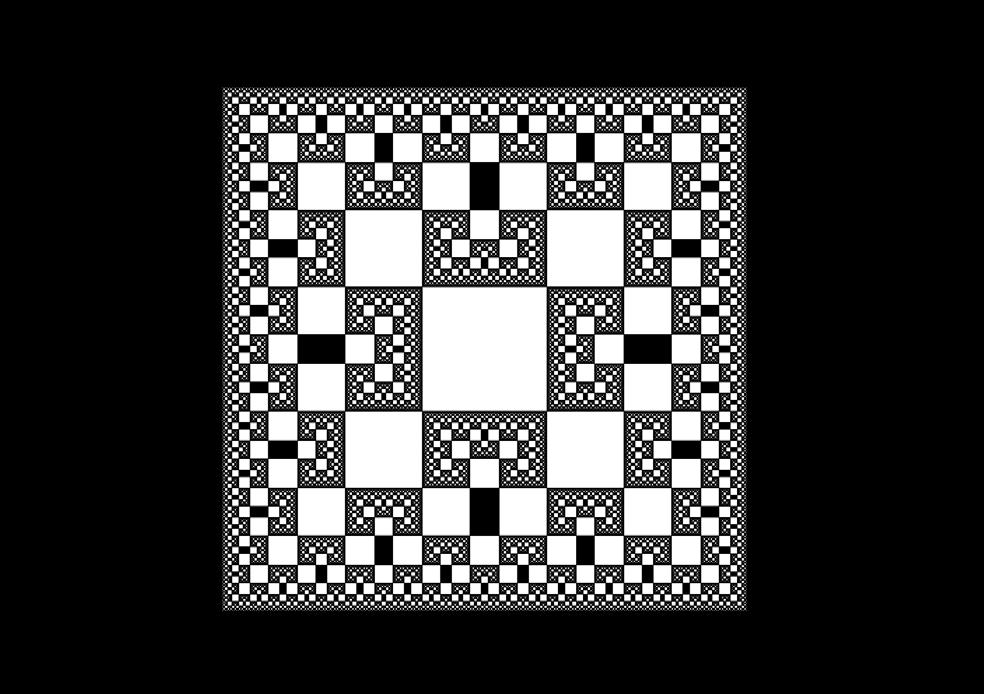

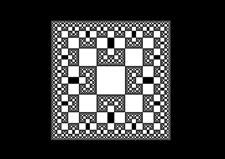

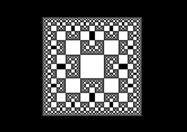

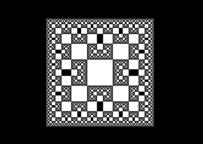

NIHIL ADDI / Φ

Borromini’s nihil addi emphasizes a design where every element derives from a foundational principle, creating a holistic whole. Inspired by his 3:2 ratio in the inner courtyard plan, we sought a similar ratio to drive our design. One aligned with nihil addi, a universal foundation connecting all elements. Naturally, we turned to the golden ratio, ±1.618, regarded as the foundation of harmony and proportion in the universe. Appearing in phenomena from spiraling galaxies to plant growth and living proportions, it suggests a foundational ratio order of balance and beauty that interconnects all. This universal balance became the nihil addi guiding our corner design.

MY RESPONSIBILITIES

Golden section calculations & translation into architecture

All 3D modeling & digital imagery

PROJECT TEAM

Janne Peeters

Nicola Stevens

Exterior view of the corner

GOLDEN SECTION

The golden ratio, Φ (approximately 1.618), is a mathematical principle with profound implications. It appears in the Fibonacci sequence, where each term is the sum of the two preceding ones. As the sequence progresses, the ratio of consecutive terms (Fn+1/ Fn) converges toward Φ. This ratio defines the golden section, dividing a line so the whole relates to the larger segment as the larger relates to the smaller. It also manifests in the golden rectangle, where the ratio of length to width is Φ. When a square is removed from this rectangle, the remaining shape is another golden rectangle, continuing the proportion. This geometric relationship creates harmonious proportions and is seen in endless natural and living forms in the universe (shell given as example).

FROM BRICK TO BUILDING Φ

The golden ratio brick is the cornerstone of our design, embodying nihil addi. Just as the golden ratio underpins the universe, the brick serves as the foundation of the building. By designing a brick based on the golden ratio, we derive all elements of the corner building from this starting point. From the golden ratio brick comes a golden ratio wall, then a facade, and so on, ultimately creating a cohesive corner building governed by the golden ratio.

SPATIAL OVERLAPPING BIFORA

Φ

Much like Borromini’s overlapping serliane to establish a corner, we designed our corner by clashing two bifora on either side of the building. Instead of a symmetrical overlap at the center mullion, the golden façade proportions allow an overlap to occur at the golden section of each bifora. Both colliding bifora have now merged into a spatial corner, manifested through a golden ratio.

Φ GOLDEN FACADE

Using the fibonacci sequence, the golden rectangle is further divided into more sections as a basis to establish all other architectural elements like brickwork pattern,

The reciprocal coming together of all architectural elements results in a golden bifora corner building founded out of a reinterpretation of the nihil addi/ serliana principle. The ground floor, following a reversed golden section of the facade, has been given a double height, elaborating the ratio all the way from brick to building itself. The corner bifora showcases a golden clash between two facades, not as opposing forces but seamlessly fused into one another.

INTERIOR CORNER

A bracing system of interconnected bifora governs as the structural system to uphold the corner building. Through fibonacci derived structural parameters, reciprocal to all other architectural elements, an outer shell is established that serves to uphold a golden arcade. While this arcade is totally open to walk through, the bifora and diagonal bracing upkeep a soft barrier between the golden rectangles of the arcade plan. A transparent division that could further serve purpose for various uses.

STRUCTURE

There are two types of load bearing columns that make up the bracing system of the corner building. The outside column that also serves as a center mullion to support each bifora and the inner columns of the arcade that also supports the inner wall . The corner bifora column features double mullions at their golden intersection, while the inner arcade column supports the double corner mullions and bracing system of both façades with a total of four arches.

These columns are made more efficient through a sublayer of golden fractal pattern perforations, reducing weight and allowing soft light to filter through.

4. ARCHITECTURE - PURISM OF FORM / 2022

For this thesis, the goal was to research an object and translate it into a 40x40 meter fictional lobby as the foundation for a high-rise. While many explored architectural works like Koolhaas, I chose to challenge myself with cinema, seeking overlaps between film and architecture. By examining visual storytelling through a new lens, I aimed to uncover parallels between these disciplines, revealing innovative ways to design spaces through a cinematic approach.

THE ARCHITECT AS DIRECTOR

Why study film as an architect?

An architect can create whole cities with reality of mass and space. He can however, not interfere with living events nor guarantee the future of his vision. A storyteller on the other hands can not only make cities, he can make whole worlds. He can reform systems, connect people and even go beyond the physical. His creations however, remain to be only fiction. A filmmaker, compared to these two, can move in time to embrace space. He can do this in an unsolicited time frame and change the image of space and time by his imagination. Both architect and storyteller look upon the filmmaker for what they lack.

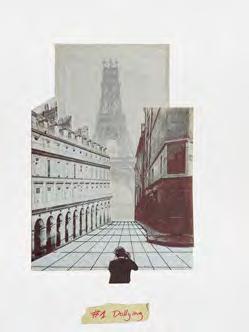

RESEARCH I - NOSTALGHIA (1980)

Nostalghia by Andrei Tarkovsky explores the journey of a Russian poet in Italy researching composer Beryózovsky, whose nostalgia led to his tragic end. Longing for home, the protagonist’s alienation deepens, blurring time, space, and reality. Tarkovsky’s linear perspective camera movements and evolving settings sculpt space in time, challenging me to translate this technique into architecture through a lobby structure.

RESEARCH II - TRANSITION

This study also explores cinematic transitions between scenes and their translation into architecture. In this lobby, each corner acts as a transition device between two façade scenes. Just as in film, where overlaps create specific narrative flows, the corners are reimagined with the same purpose to guide movements between architectural scenes.

I. PERSPECTIVE FILMOGRAPHY

Deriving inspiration from Italian Renaissance art, Tarkovsky sculpts his scenes using two perspective techniques: dollying, moving the camera toward or away from the subject, and tracking, which follows the subject laterally. These calculated motions manipulate space and time, altering reality throughout the scenes.

I. DOLLYING

In Nostalghia, Tarkovsky masterfully employs the dolly technique, moving the camera closer or farther from the subject to sculpt the scene dynamically. Inspired by the Renaissance's use of linear perspective to draw viewers into their compositions, Tarkovsky mirrors this approach in his cinematography. Many scenes in Nostalghia feature a central focal point, acting as the axis of meaning. The dolly’s calculated motion intensifies this focus, transforming the setting into a narrative force. By aligning cinematic composition with Renaissance artistry, a similar sense of depth and storytelling ensues like in a painting.

I. TRACKING

Tarkovsky’s use of tracking, where the camera moves laterally with the subject, creates a seamless flow of storytelling. Inspired by Renaissance paintings this technique mirrors how artists used horizontally elaborated perspectives to tell layered narratives within a single composition. In such paintings, viewers follow the story by visually moving from left to right, akin to reading a text. Tarkovsky translates this into film, using tracking to guide the audience through evolving scenes within one continuous take. This motion not only connects spatial elements but also enriches the temporal experience, making every frame a layered tapestry of meaning. It’s a choreography of space and time that immerses viewers in the evolving narrative.

Track

Dolly

▴Nostalghia, by Andrei Tarkovsky (1980)

▸Camera movements of tracking and dollying in cinema

The 1-point perspective for central attention & context in perspective, prominently used during the quattrocento

Six examples of dollying composition in Nostalghia

The Annunciation of Cortona. A horizontally unfolding perspective narrating multiple stories within one composition

Three examples of tracking scenes in Nostalghia

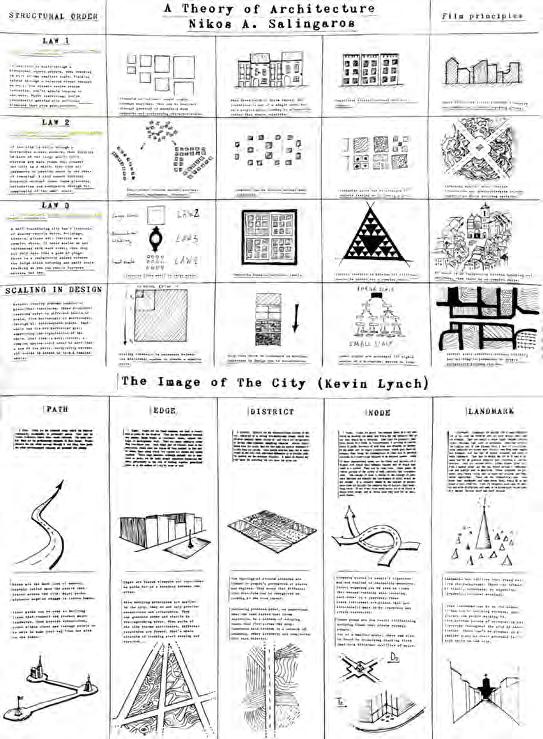

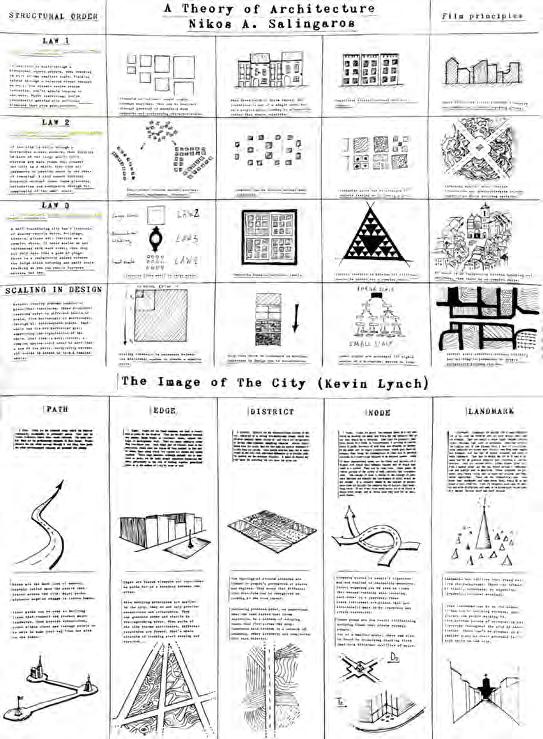

I. TRANSLATING DOLLYING & TRACKING INTO ARCHITECTURAL THEORY

This first part of the research investigated how dollying and tracking principles from cinema align with architectural theories. Using Salingaros’ hierarchical systems, dollying translates to large-scale elements like main roads, creating orientation and linking landmarks, while tracking corresponds to small-scale, dynamic spaces fostering curiosity and discovery. Similarly, Lynch’s concepts of paths, edges, nodes, and landmarks parallel these cinematic techniques. Dollying reflects ordered paths and landmarks, structuring a city’s coherence, while tracking embodies the smaller, intricate spaces that animate districts. Together, these cinematic and architectural principles highlight the reciprocity between scales, forming a cohesive framework for translating movement and storytelling into spatial design.

I. CASE STUDIES OF ARCHITECTURAL FILM THEORY

This second research part applies prior architectural findings in cinematic principles to architectural case studies from Europe and Asia, demonstrating how both dollying and tracking manifest in real-world designs. In examples like Rome’s Tridente and Beijing’s Temple of Heaven, dollying and tracking show to coexist in a hierarchical structure. Larger pathways guide movement, while smaller, dynamic spaces unfold, creating a clear presence at different urban scales.

I. TRANSLATION INTO ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN

In the third phase of the research, many collages were made to transform the findings of dollying and tracking into real architectural designs. These collages explored how both principles could manifest in concept design, to eventually incorporate dollying and tracking into a fully developed lobby layout, where both principles will govern the structure.

Dollying represents the hierarchical order of the design, where a strict grid maintains overall structure, divided by landmarks at each corner and connected paths. A steel frame with a central core is aligned with these dollying paths, guiding circulation throughout the space. These paths serve as points of orientation, ensuring cohesion and preventing chaos. Beyond the dollying edges, controlled chaos emerges. The open areas allow for organic development and freedom, where tracking roams freely, letting users shape spaces to their needs. Within the dollying boundaries, freedom thrives without oppresion, creating a lobby structure where both principles coexist, guiding movement and interaction.

GEOMETRICAL PLAN 1:100

DOLLY LANDMARK

ELEVATOR

GEOMETRICAL PLAN 1:100

DOLLY LANDMARK

ELEVATOR

SHAFT

SHAFT

CORE

GEOMETRICAL PLAN 1:100

DOLLY LANDMARK

CORE

ELEVATOR

DOLLY PASSAGE

SHAFT

WET CELL 77

CORE

DOLLY PASSAGE

WET CELL

0 5 15 40

II. CORNERS OF TRANSITION

DOLLY PASSAGE

WET CELL

While inside the architectural experience can be seen as a camera movement in film, on the outside each façade acts as a distinct scene with the corners serving as transition devices. The four facades contrast in material and openness, reflecting different scenes. While dollying through the 40x40x40 lobby, five vantage points—five corners— translate cinematic transitions into architectural form.

II. FADE

The fade is a gradual transition where a scene slowly dims to black (fade-out) or brightens from black (fade-in). It’s used to indicate the passage of time, a shift in tone, or the end or beginning of a narrative sequence. Psycho (1960), Alfred Hitchcock.

II. WIPE

The wipe transition replaces one scene with another through a line, shape, or motion moving across the screen. It’s a dynamic and noticeable effect often used to signal a shift in location or time while maintaining visual momentum. The Graduate (1967), Mike Nichols.

II. JUMP CUT

A jump cut is an abrupt transition between two sequential shots with noticeable discontinuity. It skips time or action, drawing attention to the edit. Used intentionally, it creates energy, disorientation, or emphasis within a scene. Breathless (1960), Jean-Luc Godard.

II. CUT

The cut is the most straightforward transition, where one shot instantly replaces another. It’s seamless and unnoticed in continuity editing but can be jarring in montage. It’s used to maintain rhythm or shift focus within the narrative. Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), Wes Anderson.

II. DISSOLVE

The dissolve transition overlaps two scenes, with one gradually fading out while the other fades in. It creates a smooth, temporal or spatial connection between scenes, often used to suggest a passage of time or link related imagery. Stoker (2013), Park Chan-wook.

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), Wes Anderson.

FADE

The fade corner starts at the beginning, where one is introduced to the building when walking in. Walking to the entrance of tinted windows and entering is a fade-out–fade-in experience on itself. The mullions of this corner resemble this experience by transitioning from a strict, repeating rhythm to a gradual, open, more spacious mullion rhythm when passing the corner of the entrance facade.

WIPE

In a wipe transition, one scene linearly emerges over another, gradually claiming the screen. In this corner, the mullions reflect the beginning and ending of the transition as red windows take over from the blue window scene. The floor and roof slabs show the linear overlap of the shift. Just as in film, a straightforward transition occurs between the two facades as one walks through this corner.

JUMP CUT

In this corner, abrupt interruptions occur within a scene, leading suddenly into the next without announcement. The mullions reflect this with an irregular, unpredictable rhythm, disrupting any sense of continuity. As one walks through the corner, the final jump cut delivers them into the second scene— the open facade—emphasizing the abrupt transition inherent to this device.

CUT

This transition device is straightforward, both in cinema and architecture. Walking beside the open facade, everything feels seamless until reaching a spatial point where a sharp cut transitions fully into the second scene. This abrupt yet precise boundary shifts one from one scenic space to another without overlays or interruptions, delivering a clean and decisive spatial transition.

DISSOLVE

The gradual overlapping of scenes in a dissolve is mirrored by merging the facades until one fades away and the other takes over. The first facade extends through its slabs, while the second overlaps with its mullions. As the transition progresses, both facades coexist momentarily. At the point where the slabs end, the second facade fully emerges, completing the dissolve.

5. HERITAGE - HISTORICAL RESEARCH / 2022

This assignment focused on conducting a full architectural historical research of a building, involving in-situ analysis, photographic documentation, and archival research to uncover its construction phases, history, significance and value assessment. I chose to focus on a 17th-century barn as my subject, exploring its historical context, architectural features, cultural relevance and values within its time and setting for the now and future.

IMPORTANCE OF RESEARCH

A building is like a person: it starts off fresh and unmarked, but over time, it carries the marks of its experiences. The more you learn about its history, the more fascinating it becomes once you listen to its story. Architectural history is the art of reading buildings, understanding their story, strengths, weaknesses, and potential. It forms the basis for 'living with buildings,' allowing their heritage values to come to the forefront while ensuring their place in the world of tomorrow.

OVERVIEW

This extensive 100-page research provides a comprehensive framework for the entire site, analyzing all structures, alterations, additions, and demolitions throughout its history. Each structure undergoes in-depth analysis, including construction, style, historical significance, and condition of both exterior and interior elements. Contextual research covers the surrounding area and its architectural styles, offering a broader framework. A complete value assessment is conducted, examining architectural, historical, emotional, material, societal, and communal values. This ensures appropriate safeguarding and preservation for the future, aligning with UNESCO’s heritage criteria as a basis for its safeguarding in the future.

5. HERITAGE - HISTORICAL RESEARCH / 2024

For my internship, I aimed to combine my architectural studies with my background in architecture, contributing to a heritage project. I joined Miss Miyagi, an alternative real estate developer focused on projects with positive social impact. They manage the entire process, from concept to construction. Under the guidance of Laura Joosten, heritage project architect & advisor, I focused on gaining practical insights into the field of heritage and adaptive reuse.

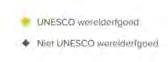

▴Example of a beguinage project fiche

BEGUINAGES IN CONTENTION

I worked on building a framework for the preservation of Flemish beguinages, with the Dendermonde Beguinage as a first case study. The focus was on exploring new usage scenarios, with cooperative housing as a potential solution for revitalizing these heritage sites. I contributed by researching beguinage cooperatives, gathering information, and organizing workshops to involve stakeholders and build a network for further development of the model.

BEGUINAGE RESEARCH

I first got acquinted with the Dendermonde beguinage. I reviewed management plans, feasibility studies etc. to build a solid foundation. This knowledge was then applied to study all Flemish beguinages, collecting various data on actors, stakeholders, ownership, and housing specifics. The goal was to compile detailed project fiches for each beguinage to create an overview, which would later inform the development strategy and be presented at the workshop.

WORKSHOP

I then organized a workshop to discuss safeguarding Flemish beguinages through cooperative living. The event brought together participants from various fields, including residents, NGOs, government officials, and university representatives. Focusing on cooperative housing, an overarching structure concept, and its potential for heritage preservation, the event sparked valuable discussions and set the stage for further progress.

▸Poster made for the workshop

Remaining flemish beguinages

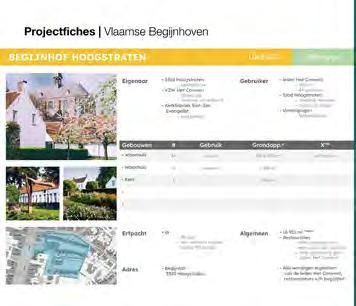

6. HERITAGE - THESIS RESEARCH / 2023 - 2024

OVERSIZE:

of Industrial Heritage in Belgium's Urban LandscapesExploring Architectural Strategies for Repurposes. This thesis investigates how industrial structures of 'oversize' often seem to be dismissed and at risk of demolition due to their collosal scale. Rather than viewing oversize as a drawback, the study looks to redefine it as a feature of immense potential. Through defining and understanding 'oversize' in architecture, historical analysis, case studies, and adaptive reuse strategies, the research highlights their architectural, cultural, and societal significance. This work aims to uncover the untapped value of oversize and advocate for its preservation and reimagining for future generations.

RESEARCH MOTIVATION

The Flemish Government Architect's 2020-2025 vision emphasizes reusing structures for a circular economy, highlighting neglected heritage with untapped potential. Industrial heritage, often oversized, faces demolition due to challenges in adapting massive spaces to new uses. As noted in 292° A+ magazine, oversize is not a structural flaw but an opportunity for innovative design. Both Belgian and international organizations like UNESCO and ICOMOS advocate for better documentation and preservation of industrial heritage. This thesis addresses the lack of strategies for repurposing oversized structures, aiming to prevent their loss and unlock their potential.

PROMOTOR

Philippe Lemineur

JURY

Marc Jacobs

Mario Rinke

Philippe Lemineur

Yonca Erkan

RISE TO OVERSIZE TO DEMISE TO REVISE

The rise of industrial heritage stems from 19th-century advances in technology, modular design, and urbanization, leading to colossal structures dominating landscapes. This bigness symbolizes both progress and decline as industries faded. Oversized monofunctional buildings now stand as neglected ruins, their vast spaces deterring reuse efforts. The chapter explores redefining and understanding oversize, proposing a need for clear definitions and strategies to tame it and unlock its potential for future reuse and preservation. Overcoming the challenges of oversize will require a shift in how these structures are perceived and repurposed.

What is oversize exactly? Many mention it, but few define it precisely. Oxford Dictionary defines oversize as excessive size, beyond the normal. Koolhaas builds on this, describing oversize as bigness, its own raison d'être devoid of context, embracing freedom and flexibility. But also as void, a prolific vessel of meaning transcending any form of presence. Elaborated further in Vai’s As Found , presenting it as a perceived emptiness with potential for transformation. Oversize is more than just size, it's a scale that completely disconnects from human size. To define it, I explored how much a building can grow before it dissociates from the human scale and built context, distinguishing ordinary size from true oversize.

HUMAN SCALE

Jan Gehl in Cities for People highlights that human sensory perception is limited by distance, both horizontally and vertically. When buildings exceed 100 meters in width or 31 meters in height, they surpass the human scale, diminishing our connection with them. This loss of connection indicates that buildings of such proportions can be considered oversize. Gehl’s parameters provide a foundation for evaluating oversize in architectural measurements.

SCALING HIERARCHY

Nikos Salingaros emphasizes that urban structures adhere to a natural scaling rule. These structures must maintain coherence between sizes through a hierarchical scaling ratio, derived from physics and biology. When the ratio exceeds 2.7, buildings break away from this natural order, becoming disconnected from their context. Therefore oversize occurs when this scaling ratio surpasses 3, causing structures to lose their connection to their environment.

SCALE PARAMETERS IN CONTEXT

These two oversize parameters are now tested by combining them in an architectural context considered ordinary in size. To define this, the average residential building's dimensions, along with larger public buildings (100-250 m² and 7-16 meters in height), serve as a baseline. Blocks that differ in oversize parameters are examined within this context to determine when they qualify as oversize and when they do not.

Horizontal field of

HUMAN SCALE IN CONTEXT (K>3)

Oversize occurs when a structure surpasses 100m in width or 31m in height, exceeding a scaling factor of 3 times the surrounding context. Station Kortrijk exemplifies horizontal oversize, with a 120m width compared to 5-20m urban structures. San Gimignano’s towers showcase vertical oversize, with ±60m heights disrupting the 10-20m local heights, both causing a clear architectural disparity and asserting dominance in their respective landscapes.

HUMAN SCALE IN CONTEXT (K<3)

However, when a building exceeds Gehl’s 100m width or 31m height but remains in a context where the scaling factor is less than 3, it no longer qualifies as oversize. Examples like the Haven building in Antwerp and the Atlas Brewery in Brussels show that, despite their large dimensions surpassing the human field of vision, the lack of significant scale deviation from their surroundings prevents them from being considered oversize

RESULTING OFFICIAL PARAMETERS OF OVERSIZE

Oversize in architecture is defined by two core parameters. First, a building must surpass human-scale dimensions, exceeding 100 meters in width or 31 meters in height, distancing itself from human interaction. Second, it must disrupt the scaling hierarchy, with a scaling ratio of k>3 compared to its architectural context. In settings featuring traces of oversize, such as clusters of large buildings, oversize status requires the building to match or exceed the general cluster’s scale (k≥1) and maintain a scaling ratio of k≥3 against the broader architectural landscape. Exceptions exist, highlighting that oversize is not solely determined by size but also by the relationships between structure, scale, and context.

Kortrijk train station

Haven 1200-1220, Port of Antwerp

San Gimignano high-rise

ATLAS brewery, Anderlecht

When testing oversize parameters of scaling hierarchy in architecture, four main scenarios emerge. First, a building exceeding a scaling factor of 3 demonstrates clear oversize, like the former Orshoven mill of Stella Artois. Second, structures in oversized contexts, such as smaller high-rises in NYC, lose oversize status due to minimal scaling differences. Third, comparisons should focus on the typical smaller buildings forming the general context, not larger exceptions like public buildings—illustrated by mill structures in Deinze. Finally, in clusters of oversize buildings, such as Vaartkom in Leuven, all structures maintain oversize if they align with or surpass their surrounding scale. These scenarios clarify oversize scaling dynamics in varying contexts.

REOCCURING THEMES OF OVERSIZE IN INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE

Having established the oversize parameters, the next phase involved identifying oversize structures within Belgian industrial heritage. To achieve this, multiple industrial heritage inventories were analyzed to determine which types of buildings meet the oversize criteria. This led to the identification six typologies arching four industrial themes: textile factories, warehouses, power plants (2), train stations, and silos. These categories, when compared to Liliane Wong’s typological index, align with the broader themes of manufacturing, energy, transport, and agriculture. This categorization serves as the basis for further exploration into the specific occurrences of oversize in Belgian industrial architecture.

Various mill structures, Deinze

oversize cluster at Vaartkom, Leuven

The Manhattan Logic in effect

Orshoven mill, Leuven

NYC high-rise engulfed by a context of oversize

ARCHITECTURAL QUALITY

To find architectural qualities in industrial heritage of oversize, it’s crucial first to define what architectural quality truly means. Does it refer to construction performance, geometric harmony, or patterns that enhance spatial use and life quality? This research delves into these questions through the philosophies of Laugier’s Primitive Hut and Christopher Alexander’s Quality Without a Name. Their principles—focused on architecture as a values for quality of life—offer a better understanding to identify what gives oversize buildings their unique architectural quality of life and how they can be repurposed effectively to create a building that embodies the true meaning of architectural quality.

I. GENERATE LIFE

To generate architectural quality, it’s important to understand that this quality can’t be forced, but must be generated through human interaction, as Christopher Alexander’s concept of "the quality without a name" suggests. A building's quality comes from allowing living patterns to emerge, enabling people to freely express their energies and form connections. To allow living patterns to unfold, buildings must be malleable, offering freedom of expression rather than forcing users to conform. The ability to shape a building ensures that its role in the community remains alive and evolving, securing its longterm preservation. Generating such living patterns can be strengthened through a narrative—buildings with strong social histories connect with their communities and offer more than just aesthetic or functional value, something almost all industrial heritage buildings have. It gives buildings the power to shape and sustain community identities. The creation of continuity, involvement of communities, and an ever-evolving narrative around a building ensures its relevance over time. It governs a dynamic process that encourage growth and adaptation.

III. DIFFICULT WHOLE

To generate space for living patterns to manifest, a building must become a difficult whole. Like a seed turning into a flower, each level within the scaling hierarchy must possess autonomy, while remaining interconnected. A difficult whole, as Venturi calls it, thrives on pluralism, where distinct levels, each with its own complexity, interact yet form a unified whole. Just as a flower adapts to its surroundings, a building needs to allow its occupants to influence and adapt the space to meet their needs. This autonomy across all levels of scale generates a reciprocal relationship between human and oversize dimensions. By intertwining these scales through a hierarchy of intermediate scales, a dynamic, adaptable system is formed. Urban grid systems, like the Roman Castrum or Greek cities, exemplify this idea. A solid grid allows for an effective scaling hierarchy while fostering the autonomy of different spaces. In these cities, the scaling hierarchy was supported by social change, allowing communities to evolve and thrive. A balance between order and flexibility, where autonomy exists within, allowing diverse living patterns to unfold across the city, creating a difficult whole.

Quality without a name is a process which allows the life within a person, family or town to flourish, openly, in freedom, so vividly that it gives birth, of its own accord, to the natural order.

It is with architecture as with all other arts, its principles are founded upon simple nature, and in the proceedings of this are clearly shown the rules of that. — Let us never lose sight of little rustic hut.

II. SCALING HIERARCHY

Integrating human scale into oversized buildings requires an understanding how scaling hierarchy bridges the gap. Salingaros emphasizes the importance of a scaling hierarchy to connect structures of varying sizes, with 2-3 ratios ensuring cohesion. Oversized structures can adopt this hierarchy to support both human and large-scale dimensions through hierarchical division. This promotes reciprocal interaction between different scales. Examples like the Roman Castrum grid and Strandvejskvarteret demonstrate how scaling hierarchy fosters connection and creates functional, interconnected spaces. These principles ensure both human scale and oversize structures can coexist and support one another.

ROMAN CITIES

shaped by the castrum principle, they embraced a hierarchical urban grid, separating spatial functions while allowing for citizen-driven adaptations, creating a unified yet diverse city fostering autonomy.

OSTIA, ITALY akeyRomanportcity,exemplifying a difficult whole. Its urban castrum grid, a dynamic environment with diverse functions and adaptations over time, allowing the community to evolve within a unified framework.

PRIENE, GREECE

Greek cities, the grid centered around citizens, with key public spaces like the agora and temples. This allowed for citizens to adapt and modify, creating a dynamic and communal urban environment.

Scaling hierarchy facade

Scaling hierarchy plan

Strandvejskvarteret facade

Castrum Timgad, Algeria

ARCHITECTURAL QUALITIES OF OVERSIZE

This part of the thesis explores the spatial dimensions of oversize, building on earlier research defining its forms and parameters within Belgian industrial heritage. The focus now shifts to how oversize manifests in architectural space and how work with these characteristics thoughtfully. Two primary forms of oversize are identified: BIGNESS and the void. Bigness refers to oversized exterior mass that dominates its environment, creating monumental structures that often overshadow their surroundings. These buildings assert their presence through scale, and while challenging

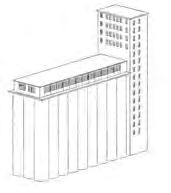

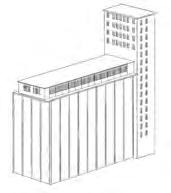

BIGNESS

BIGNESS refers to structures that dominate their surroundings through colossal scaling, claiming a place in a new context. The form, mass, and morphology of industrial buildings are derived from their monofunctional nature, designed to perform a specific function. Their brutalist nature reflects the modernist principle "form follows function," amplifying the building's raison d’être. Repurposing oversize buildings allows freedom to reshape, but altering the defining morphology risks stripping away the narrative behind its BIGNESS. Once the functional form is compromised, its identity weakens, reducing it to just a mass. Interventions must respect its authentic form to preserve its significance.

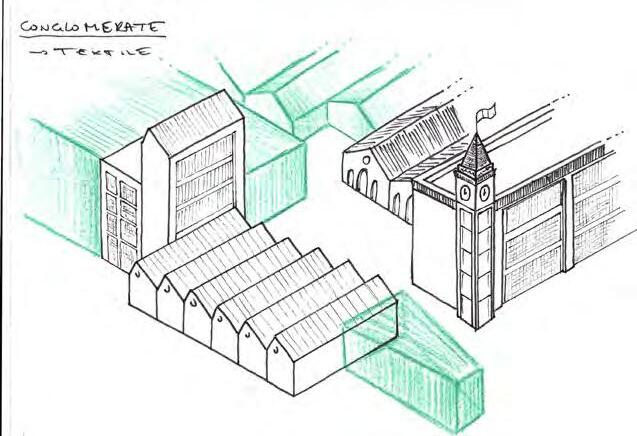

— CONGLOMERATE —

Adapting conglomerate forms can enrich their narrative of different layers overtime, if prior layers remain intact. Overwhelming new additions, however, erase the layered bigness form that defines these structures.

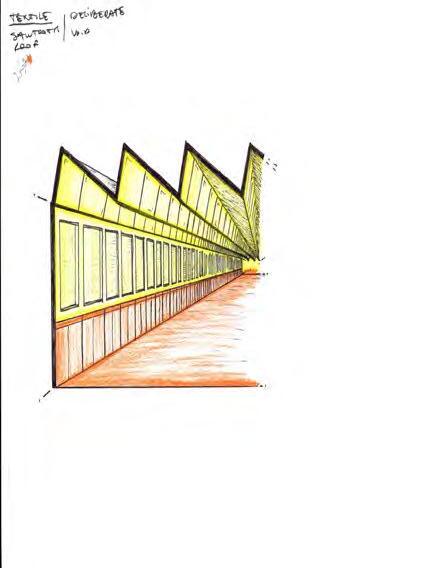

— TEXTILE —

Adding floors to multi-story factories preserves their bigness if facades remain undisturbed. However, altering iconic forms like sawtooth or gable types disrupts the structure’s essential form.

— TRANSPORT —

Train stations rely on an iconic trinity form: a central hall with wings. Maintaining this hierarchy ensures their bigness, but disrupting proportions or repetitive wings undermines their unity.

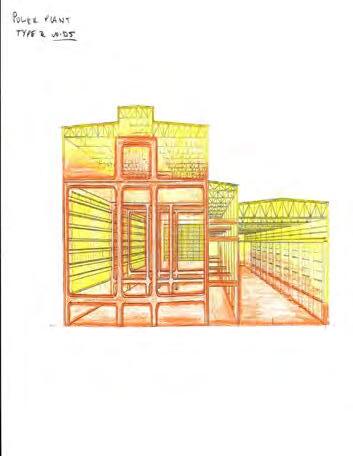

— ENERGY —

Power plants’ bigness stems from turbine and boiler halls. Respecting their spatial hierarchy enhances their form, but overwhelming additions that claim new bigness or reform, will compromise their identity.

— AGRICULTURE —

Silos derive bigness from opaque massandtoweringform.Surrounding parts can adapt, but distorting silo proportions or compromising their solid appearance undermines their founding raison d'être.

in integration, offer great potential for adaptive reuse. The void, in contrast, refers to vast, empty interior spaces that evoke awe through scale. While these empty expanses may seem impractical, they provide unique opportunities for architectural expression and flexible, multifunctional use, contributing to a building's identity and spatial experience. This chapter examines how to address both bigness and the void. This research part should aid with thoughtful design strategies, so oversized elements can enhance a building's architectural quality. The research demonstrates how these oversize forms can be read and understood, so to design reciprocally with those characteristics in question.

VOID

The void represents a perceived emptiness, a spatial surplus within a confined space, characterized by a presence of absence. Unlike bigness, its nuanced presence acts as a vessel of meaning, requiring thoughtful interpretation. There are two types of voids in oversize. The deliberate void is intentionally designed to serve a specific purpose, integral to the building's function. Altering it risks weakening the narrative, so repurposing must preserve its essence to enhance its meaning. The residual void emerges when spaces once active become empty, reflecting their former purpose. These can be revitalized by introducing new functions or living patterns to restore vibrancy. Often, both void types coexist in a single building, such as when functional voids lose purpose, leaving once-bustling areas vacant. This interplay necessitates a nuanced repurposing approach. Emotional or historically charged voids require sensitive designs to respect their narrative and avoid undermining their significance.

TEXTILE —

Sawtooth roofs create deliberate voids for daylight and visibility, while ground floors often serve as residual voids. Upper voids best remain untouched, while ground levels and warehouses allow flexibility for reuse.

TRANSPORT —

Traindepots&turbinehallsfeature deliberate upper voids for light and fumes and residual voids below. Ground-levelvoidsareidealforreuse, but upper voids require preservation to maintain their functional narrative.

ENERGY —

Boiler rooms residual voids span multiple levels, offering adaptive opportunities. Turbine halls demand transparent reuse to protect deliberate voids and daylight flow, ensuring alignment with their original narrative.

AGRICULTURE —

Silos,pure residual voids, depend on their opaque verticality. Ground floors allow flexibility, but any division disrupts deliberate voids. Enfilades canrepurposesiloswhilemaintaining transparency and structural integrity.

THESIS CONCLUSION

Industrial heritage remains undervalued, leading to the loss of irreplaceable structures despite contemporary values emphasizing sustainability and environmental preservation. While adaptive reuse is a frequent topic, the continued demolition of industrial buildings highlights a disconnect in understanding their potential, particularly regarding oversize. Often misunderstood as merely a scale issue, oversize embodies deeper layers of meaning, necessitating thoughtful research to uncover its narrative and potential for reuse. Oversize transcends dimensions; it represents a distinct presence within the landscape, imbued with functional and symbolic significance. The lack of comprehension surrounding these structures often results in their neglect and demolition, driven not by inherent flaws but by the absence of communal interest. Successful examples of adaptive reuse demonstrate that these structures' survival hinges on the narratives communities associate with them. When these narratives are absent, oversize is reduced to a problem rather than an opportunity. This thesis concludes that architectural quality in oversize lies not in physical attributes alone but in understanding its existence and meaning. Whether void or bigness, these qualities provide the foundation for integrating such structures into communities. By aligning its narrative with communal values, oversize evolves into a source of vitality, fostering a shared future for society and heritage.

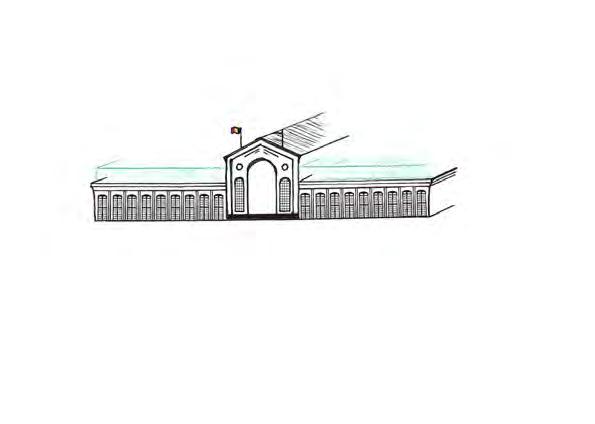

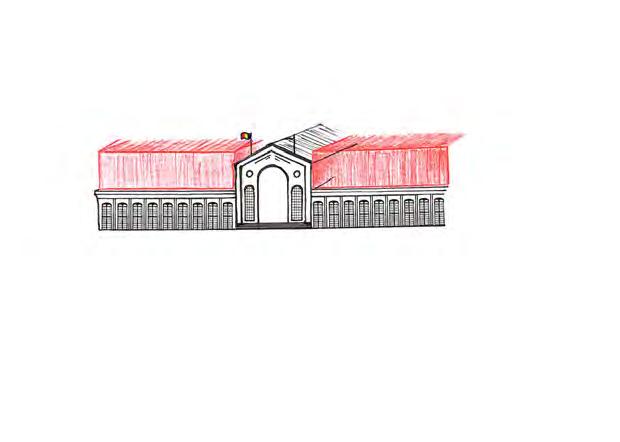

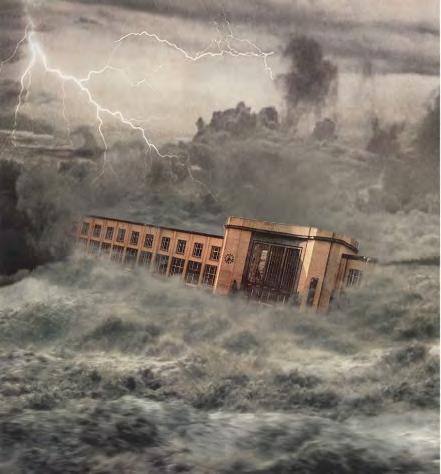

7. HERITAGE - COMPETITION / 2023 - 2024

Station Kortrijk, listed among Europa Nostra’s 7 Most Endangered Sites of 2023, faces potential demolition despite its historical value. To safeguard it, VVIA and Europa Nostra launched an idea competition, encouraging adaptive reuse concepts to highlight its untapped potential. My colleague Ellen Tielemans and I participated, presenting a winning proposal that reimagines the station as an active part of the city while preserving its architectural-historical significance.

ON THE BRINK OF DROWNING

In line with Kortrijk’s ambition to become the EU’s cultural capital by 2030, the mayor proposes to demolish and replace the current station for a massive(ly expensive) new European hub, superficial in design and cheaply mimicking Liège’s station. Kortrijk's industrial heritage is central to the city's cultural capital ambition. The station, a key example of the city's post-WWII reconstruction architecture, is one of the rare remaining train stations in this style, with many others already demolished. Revitalizing the station is crucial to preserving Kortrijk’s industrial narrative & cultural identity.

MY RESPONSIBILITIES

Concept approach (group effort)

Design interventions & narrative

3D Axonometries

PROJECT TEAM

Nicola Stevens

Ellen Tielemans

Co-working, workshop, atelier, studeren, vergaderen Loket, wachten, passeren, bezoeken

Expositie

Pop-up winkel

Eten, drinken

ONDERWIJS SPORT

Supermarkt

De Lijn

BUSSINES CENTRA CREATIEF NETWERK TOP TIEN KORTRIJK CREATIVE CITY TOUR

BUSSINES CENTRA CREATIEF NETWERK TOP TIEN KORTRIJK

CREATIVE CITY TOUR

ANALYSIS & AMBITION

Durability

Duurzaamheid

Creativiteit en kunst

Art & Creativity

Co-working, workshop, atelier, studeren, vergaderen Loket, wachten, passeren, bezoeken

Industrial history of Kortrijk and railways

Co-working, workshop, atelier, study, congregate Ticket window, waiting, passage, visit Exhibition

Industriële geschiedenis van Kortrijk en spoorwegen

Ondernemen en business

Enterpreneurship & business

Design & innovation

Design en innovatie

Expositie

Pop-up store

Pop-up winkel

Food & drinks

Eten, drinken

Supermarket

Supermarkt

Bus office

De Lijn

CONCIËRGERIE

SPIJSZAAL (dining hall)

WASPLAATS

WASZAAL (washing basin personnel)

Creativiteit en kunst

BUREAU

BODE

BODE (postal services)

SPIJSZAAL (dining room)

HAL (entrance hall)

LOKET (ticket office)

LOKET

Duurzaamheid

BUREAU (offices)

A city shaped by its industrial past, embodies a rich spirit of entrepreneurship & adaptability, especially after WWII. The station, central to this transformation, now stands as a symbol of the city's resilience & growth. Positioned in a prime location, it holds immense potential to become a dynamic center for various functions. The vision is to transform the station into a hub where diverse disciplines can meet, collaborate & innovate, en suring the station remains integral to Kortrijk's evolving narrative.

REINVENTING THE NARRATIVE

Industriële geschiedenis van Kortrijk en spoorwegen

Ondernemen en business

Design en innovatie

BAGAGE (bagage storage)

SPIJSZAAL BAGAGE

BEWEGING (movement functions)

DIENST (services)

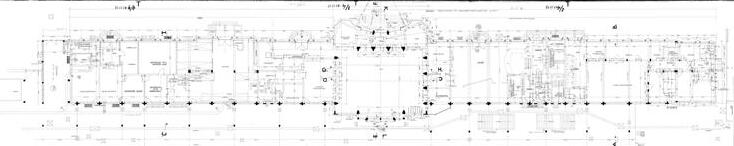

To reinforce the building's narrative and enhance user orientation, spaces are named after their original functions, as identified in historical plans. This connects the station to its past, creating a story for users to engage with. Areas like Spijszaal (Dining Hall) & Loket (Ticket Office) will help users navigate and strengthen the building’s connection to Kortrijk’s history. The preservation of existing structures coupled with modern interventions will thereby reciprocally strengthen the building's narrative.

I. INTERVENTION PHILOSOPHY

A dynamic approach to the building is enforced, prioritizing its ability to evolve while preserving its architectural qualities. Non-invasive, targeted interventions will enhance existing spaces without altering their original character. By working with what is already in place, the building can adapt to future needs while retaining its value. This philosophy focuses on sustainable, thoughtful changes, with minimal disruption to the structure and function. Working with what is present, for the future.

II. INTERVENTION PHILOSOPHY - NEOCLASSICISM

The building’s modern classical style blends classic aesthetics with functional layouts and modern construction techniques. Its monumental façade, inspired by Renaissance principles, features a symmetrical three-part structure. The central section, marked by concave forms and a grand entrance crowned with stone cornices, projects prominence, while the wings exhibit a rhythmic balance of brick patterns, pilasters, and stone-framed windows. This hierarchy enhances its grandeur. Disrupting such elements, as is happening as of now, compromises the building’s identity. Interventions must preserve these neoclassical features, ensuring the station retains its impressive and monumental presence.

FACADE STATION SQUARE

The station square facade is activated with platforms added to both wings to bring a more interactive connection to the station square. Flexible seating and sit-steps foster activity, while a narrow clay-brick plaza offers a warm, versatile space for gatherings and events.

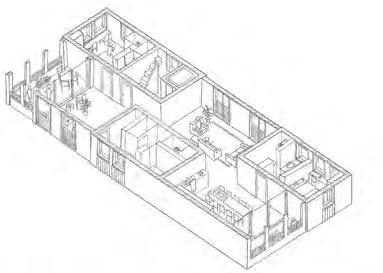

CENTRAL HALL AND PASSAGE BETWEEN WINGS

Residual spaces, previously unused and closed off, are transformed to connect the building’s wings, fostering moments of interaction between their users. Enhanced with seating spaces, these spaces offer quiet retreats and encouraging moments of dialogue.

The left wing area next to the central hall, previously the dining area (Spijszaal), is reimagined as a space for exhibitions and events, showcasing Kortrijk’s creativity. A connection is made to the enclosed bunker, allowing visitors to experience the post-war period narrative.

The vibrant modernist accents of the central hall are restored and kept open, reviving its original charm. The discontinued ticket counter is adaptively repurposed into a seating and dining area for travelers, retaining its narrative identity under the name 'Loket'.

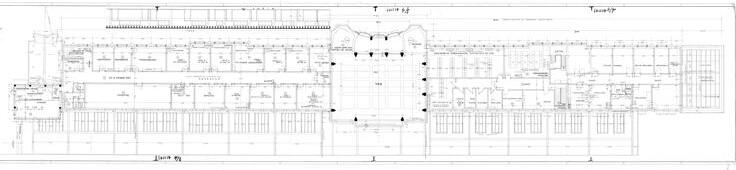

CHILLING AREA BETWEEN WINGS AND OFFICES

A former residual space now connects the wings, offering moments for interaction or retreat. Adjacent is the 'Bureau,' once the station’s administrative offices, with the hallway entrence featuring openings transformed into areas for individual work or group seating.

The space, named "Bode" after its former role in postal services, could host pop-up stores displaying products, art, and ideas. Reversible split-levels in light materials create smaller spaces with a 5-meter ceiling, connecting to an atrium to enhance flow and interaction.

CENTRAL HALL

EXHIBITION WITH BUNKER

POP-UP STORE

II. INTERVENTION PHILOSOPHY -

The building's modernist elements are reflected in its construction, particularly the central hall’s transparent concrete column structure. Many vibrant features, like tile patterns and coloring accents of architectural elements, symbolized the innovation of post-war reconstruction architecture. Now these are masked, the hall reduced to a monotonous space. The wings in contrary exhibit functional variability, with structures tailored for specific functions. Our interventions aim to restore the central hall’s openness, reintroducing its original vibrancy, while leveraging the structural diversity of the wings to cultivate intimate, autonomous spaces that generate life patterns and enhance user interaction and retreat.

MULTI-USE SPACES

The first floor, this area formerly a bathing area for personnel, is to host creative and entrepreneurial users. Coworking spaces, offices, meeting rooms, workshops, and classrooms. The layout remains flexible and fairly untouched to accommodate diverse functions.

The other wing receives an additional stair for accessibility, our largest intervention. Residual spaces are opened up for individual work, calling, and sitting areas. This fosters interaction, encouraging mingling between entrepreneurs and creative minds in the space.

UANTWERPEN.BE/NL/ STUDEREN/AANBOD/ALLE-OPLEIDINGEN/MASTER-ERFGOEDSTUDIES/MAJOREN/ GEBOUWD-ERFGOED/STATION-KORTRIJK/

UNIVERSITY OF ANTWERP PUBLISHED ARTICLE

Our competition win gained significant attention across various news outlets, with the University of Antwerp being the primary source of coverage. As we were studying there at the time, the university took great interest in our project, interviewing us about the concept and its background. The publication highlighted the importance of preserving Station Kortrijk, focusing on raising awareness about the value of industrial heritage. It also emphasized the university's role in the study of built heritage. The official winning concept note and panels that were submitted for the competition are available on the university's website for those interested in more detailed information.

HALL RIGHT WING