Temporal Citizenship: Towards an Empathetic City

Stephanie Siy Cha

Urban Interiority

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 2 3

Abstract Introduction Literature Review Community of Practice Phase 1: Preliminary Investigations Urban Subjects Urban Space City of Melbourne’s Challenges and Aspirations Phase 2: Towards a New Urban Interiority Phase 3: A New Urban Interiority for Melbourne Site Selection: More Than Just an Economic Exchange Conversations with Melbourne Thinking beyond the self Phase 1: Collection Phase 2: Activation Phase 3: Circulation Creating a Design Language Temporal Citizenship: Toward an Empathetic City Conclusion Annotated Bibliography Image List Bibliography 4 5 7 10 18 20 20 24 26 36 44 45 48 49 50 56 60 62 63 64 66 74 76

Content Acknowledgements

First and foremost, to the council of the City of Melbourne, thank you for giving us this opportunity to design these series of interventions for the betterment of the City of Melbourne. Because of this opportunity, I learned and appreciated Melbourne more, especially as an international student.

To Jessica and Feng, thank you for all of the contributions you have made for this project and putting all your efforts into the group. This research design would not have been where it is today without your help. Our work ethic and our chemistry as a group helped us accomplish all our goals as a team, creating a project that we are truly proud of and stand by at all costs.

To Dr. Roger Kemp, thank you for your help and cooperation throughout the writing process of this project. Thank you for all the advice and notes that you have provided, which helped me understand the project and motivate me more throughout the semester.

To Associate Dean Suzie Attiwill and Lingas Tran, thank you for all the feedback and advice that you have so generously provided to my group, especially when there were issues with the design process.

This research investigates the relationship of individuals and the urban environment in an interior context, through the understanding of urban interiority. By doing so, we are changing the conventional way of designing the city and the urban space. More than just designing for efficiency and liveability, urban interiority allows us to think of urban design as the individual’s personal relationships and experiences with the city and vice versa. I first analysed the factors surrounding “urban subjects” and “urban spaces” and related them to the City of Melbourne to provide further context. Working in a team to explore new ideas, we were able to create a new urban interiority through an experimental phase, which we titled “Temporal Citizenship.” Here, we defined key terms and key beliefs in relation to what it means to have a sense of temporal citizenship and the potential of this for a city. A series of interventions were made in the City of Melbourne. These interventions focus on the actions of saying, listening, and seeing, showing the importance of these actions in exchanging experiences with one another. Through this, people can create their own experiences while also learning and relating to others’ experiences, allowing them to think beyond themselves and more about the people and Melbourne.

Keywords

Urban interiority, temporality, citizenship, interiors, exchange

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 4 5

Acknowledgements Abstract

In 2011, the International Federation of Interior Architects/Designers (IFI) held a global workshop. In this workshop, they expanded the definition of Interior Design as more than an architectural space making approach. From this workshop, they declared that Interior Design focuses on the relation between people and their environment[1]. This means that Interior Design is now not constricted to designing within enclosed spaces, which ultimately resulted in designers thinking and working more into the concept of urban interiority.

The discourse around urban interiors, however, is not new. In fact, philosophers such as Walter Benjamin often discusses the relationship and the dynamics of the interior and urban[2]. Camillo Sitte’s book, City Planning According to Artistic Principles, argues to approach city planning with “artistic methods of arrangement and aesthetics at the time when urban planning was increasingly focused on challenges of transportation.[3]” However, because of the new realised definition of Interior Design, the concept urban interiority has just recently started being more widely practiced by designers, which invites designers to think about designing the urban environment with the sensibility and techniques of interior design. Urban interiority challenges the single inwardness of the term “interiority” to a more “outward” approach. Allowing interiority to be “outward” changes people’s relationship with the city and the city’s relationship with the people.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 6 7 Introduction

[1] Suzie Atiwill, “Interior Designing in the Urban Environment: Practices for the 21st Century,” in Handbook of Research and Methodologies for Design and Production Practices in Interior Architecture, eds. Evin Garip and S. Banu Garip, (USA: IGI Global, 393).

[2] Suzie Atiwill, Elena Enrica Giunta, David Fassi, Luciano Crespi, and Herminda Belén, “Urban + Interior,” Idea Journal, 15, 1, (2015): 2.

[3] Atiwill, “Interior Designing in the Urban Environment for the 21st Century,” 393.

“Interior Design is now not constricted to designing within enclosed spaces”

The City of Melbourne have various plans and projects that focus on opening up the city to allow people to engage with it more. The goal of these developments and projects is to improve the wellbeing of the city’s residents. Especially with the impacts that COVID-19 has done to the city and its people, there is now a better appreciation and demand for a resilient city that can respond to such events, focusing on the mental and physical wellbeing of the residents[4]. However, even before the pandemic, projects have already either been planned or started in developing a more hospitable city. In fact, many of the City of Melbourne’s current projects and aspirations is to create many open spaces and parks around the city as it is known that these types of spaces can improve the physical and mental health of the residents.

To gain a better understanding of the concept of urban interior and how other designers and academic view this discourse, a series of literature reviews were discussed at the beginning of the design research process.

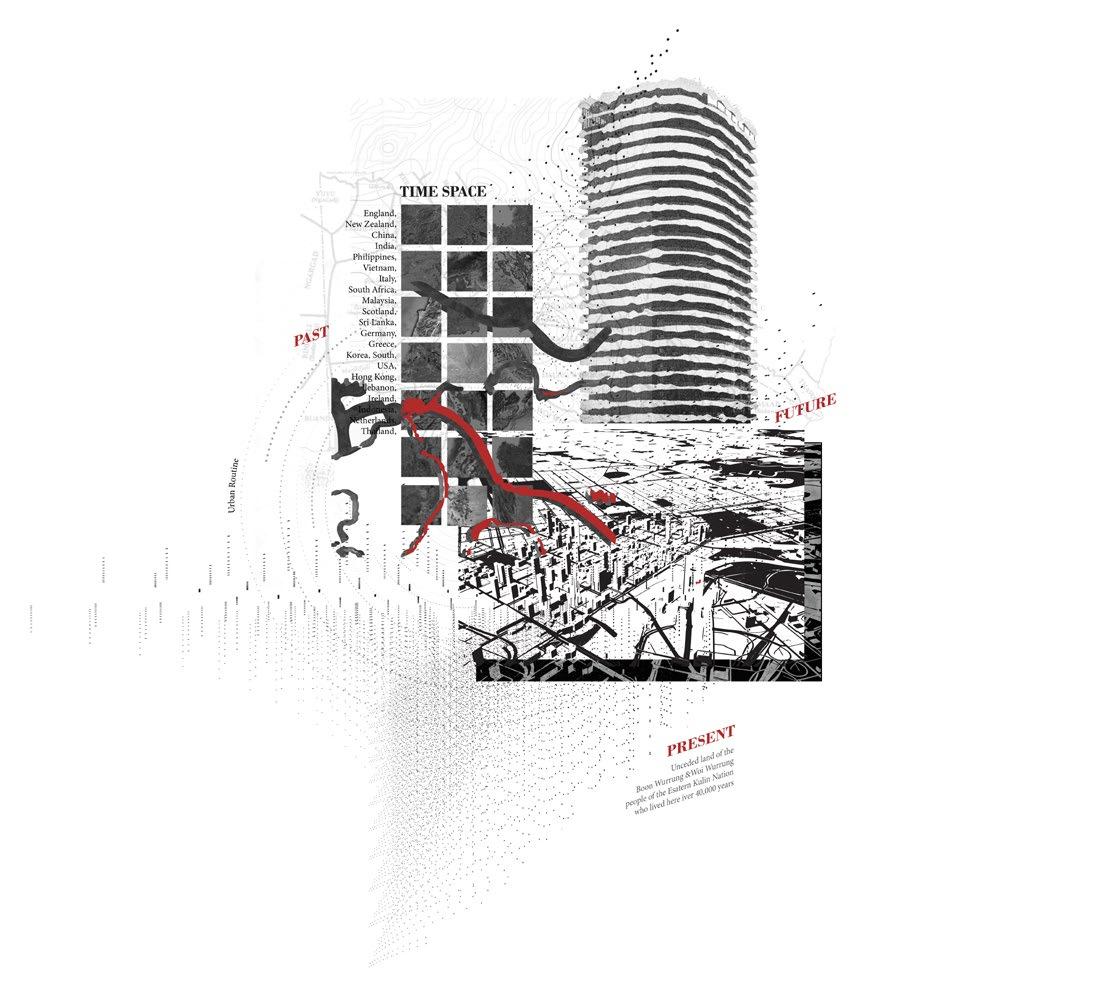

Working in a team of international students, we strongly believe that a citizen need not be tied to the community politically. Thus, the term “temporal citizenship” was made, which argues that the notion of citizen should also be able to reap the benefits of the socio-cultural aspects of a city. Temporal citizenship focuses more on how the individual experiences in the city, rather what the individual experiences. It allows a sense of agency, security and curiosity, allowing them to truly feel a part of the city, even without being politically tied to it.

The urban interiority was realised through a program that allowed the inhabitants to share their concerns, testimonies, and stories about Melbourne and their experiences in Melbourne. The objective of this program is to encourage people to think beyond themselves and to experience the city through self-reflection and also through the experiences of other inhabitants of the city. With this exchange, the hope is to have a better personal relationship with the city and the people around it, creating a better Melbourne.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 8 9

[4] City of Melbourne, COVID-19 Reactivation and Recovery Plan: City of the Future, 2020, 23.

Ariel Vvew of Bourke Street Redevelopment

Literature Review

A diverse series of works were thoroughly studied about the concept of urban interiority. Through this, we are able to learn more on how the term and concept of urban interiority is being used by different designers and philosophers, which can lead us into forming our own thoughts and ideas on urban interiority.

A common theme across many of the references collected is the history of the concept of urban interiority, specifically, the relationship between the ‘urban’ and ‘interior’. Jacopo Leveratto’s paper, Urban Interiors: A Retroactive Investigation, looks into the history of the concept of urban interiors, both from a theoretical and practical point of view[5]. Leveratto argues that to understand the practice of urban interiority, we must have knowledge of its historical context. The author cites and provides critical analyses on what previous designers and philosophers have already said regarding the relationship between urban and interiors. Through the paper’s comprehensive investigation on the historical context of the concept of urban interiors, Leveratto was able to conclude that the discussion of “interioritizing” the urban environment is not entirely recent. Moreover, by outlining the history of the concept of urban interiors, he argues that that interior disciplines can be solid precedents for current and future urban studies and can be used as effective research to identify innovative strategies to create a hospitable urban space[6].

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 10 11

[5] Jacopo Leveratto, “Urban Interiors: A Retroactive Inveestigation,” Journal of Interior Design, 44, 3 (2019), 162.

[6] Leveratto, “Urban Interiors,” 168.

Top: Giambattista Nolli’s Map of Rome, 1784

Bottom: 19th Century Parisian Arcades as described by Walter Benjamin

In Liz Teston’s On the Nature of Public Interiority, she argues that “interiority” is a “condition of senses rather than an indoor place[7].” She notes that a space does not need to be enclosed in an architectural form for it to feel like an interior. The paper further argues that having a strong understanding of the public interiority allows us to appreciate how to design with the human condition in mind[8]. According to Teston, “we can perceive conditions of interiority based on several factors – formal, psychological, programmatic and phenomenology and object-oriented-ontology. Therefore, the author further explores the nature of interiority by citing the works of those who are well versed in these topics such as Kant, Sennett and Pallasmaa. Finally, after identifying and critically discussing these ontologies, Teston analyses the taxonomy of public interiorities using real-world examples from previous research that she has conducted. Teston concludes that “interioritizing” public spaces allow users to interpret space and place in multiple ways, therefore creating a space that is centred on the experience of the human and allowing the interior to be brought to the city.

The Public Interior: The Meeting Place for the Urban and the Interior, an essay by Tine Poot, Martine Van Acker and Els De Vos begins by defining public interiors as more than just public buildings such as libraries, shopping malls and hospitals. Public interiors also include publicly owned spaces such as passages, arcades and inner courtyards to name a few, which are often considered as “secondary public spaces [9].” Throughout the paper, the authors explore different methods to analyse the concept of the public interior in multiple fields such as urbanism, architecture, interior design and other related fields. Consequently, the authors argue that the designers with different backgrounds bring different perspectives that can work together to support a design outcome to form a more welcoming urban space[10]. This paper observes the different practices of each profession within the broader design industry emphasising the opportunity to learn from one another to create great public interiors.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 12 13

[7] Liz Teston, “On the Nature of Ineriority,” Interiority, 3, 5, (2020): 61.

[8] Teston, “On the Nature of Public Interiority,” 63.

“Interiority is a condition of senses rather than an indoor place.”

[9] Tine Poot, Maarten Van Acker and Els De Vos, “The Public Interior: The Meeting Place for the Urban and the Interior,” IDEA Journal, 15, 1 (2015), 44.

[10] Tine Poot, Maarten Van Acker and Els De Vos, “The Public Interior,” 52. Top: Liz Teston’s taxonomy of public interiority

Gretchen Coombs’ Inside Out: When Objects Inhabit the Streets, explores the way in which participatory art projects can transform into urban activities. She looks at how interactive art projects affect how people experience the city. Art installations, particularly interactive ones, disrupts the way in which the urban environment normally functions, thus enticing the people to experience their urban habitat differently[11]. The paper investigates two key participatory art projects by Sheryl Oring and Michael Swaine. Oring and Swaine both displaced objects that are normally “interiorized” (a typewriter and a sewing machine respectively) and brought them outside to the public. By doing so, it created a sense of enclosure and proximity, thus, people tend to move closer to each other, further supporting the point that interiors and objects found in interiors “influence the relationship and the spaces between people[12].” The author argues that interiorising urban space in any ways allows people to actually experience the city and interact with one another instead of simply getting to their destination as quickly as possible.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 14 15

[11] Gretchen Coombs, “Inside Out: When Objects Inhabit the Streets,” IDEA Journal, 15, 1 (2018), 90.

[12] Coombs, “Inside Out,” 92.

“Interiors and objects found in interiors influence the relationship and the spaces between people .”

Left: Michael Swaine, The Free Mending Library, 2004-ongoing

Top: Sheryl Oring, I Wish to Say, 2004-ongoing

Bottom: Sheryl Oring, Maueramt, 2014

E-Urbanism: Strategies to Develop a New Urban Interior Design, a paper by Barbara Di Prete, Davide Crippa, and Emilio Lonardo looks into new ways to “interiorize” and urban environment to constantly improve user experience. According to the authors, when exploring the city, we usually notice and focus on its interior qualities, identifying them as familiar spaces[13]. We notice these qualities more than the unfamiliar as it brings a welcoming hospitality, creating a domestic experience for us as inhabitants of the city. The critical point here is to show that there could be new ways to develop an urban interior design, especially in the digital age. Di Prete, Crippa, and Lonardo examines different projects using placemaking, place-branding and crowdfunding, most of which are executed online via different platforms of social media, that creates this idea of “Co-Urbanism,” where urban planning now promotes a bottom-up approach (i.e., the community is encouraged to participate in the planning process of their neighbourhood or city). The authors propose to shift the term “CoUrbanism to “E-Urbanism” with the argument that the world we live in today is often more virtual rather than physical[14]. Thus, from this view of a participatory design, citizens are more active in contributing to their cities in different ways. Engaging is important here, involving citizens to feel as though they do belong in a space allows them to be closer and experience the urban environment in a more personal way instead of considering it as an unknown place[15].

Having read multiple literature regarding urban interiority helped shape my understanding on the concept. By first reading on how the concept of urban interiority came about, I learned that this notion of urban interiors is not a new discourse and that it has been a topic of conversation by academics and designers that are not in the Interior Design field. Through Leveratto’s writing, there is now a better understanding on investigating innovative strategies on creating a hospitable urban environment. Many of the works reviewed in this section though approaches the idea of urban interiority in different ways beyond what it is and how the concept came to be. A commonality between these articles is that the projects, whether it be art installations, urban planning, or other forms of design, is that these projects studied by the different authors conclude that they create a sense of interiority even if they are in open spaces. Based on these readings, the meaning of ‘interior’ now is more than just a space contained in four walls. It now also means the individual’s relationship with the space and the feelings the space gives the individual.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 16 17

[13] Barbara Di Prete, David Crippa and Emilio Lonardo, “E-Urbanism: Strategies to Develop a New Urban Interior Design,” IDEA Journal, 15, 1 (2018), 15.

[14] Di Prete, Crippa and Lonardo, “E-Urbanism,” 18.

[15] Di Prete, Crippa and Lonardo, “E-Urbanism,” 25.

“The meaning of ‘interior’ now is more than just a space contained in four walls.”

Community of Practice

MODULARITY

MODULARITY

CONNECTION TO NATURE

Incorporating nature in the design

CONNECTION TO NATURE

Incorporating nature in the design

SIMPLICITY/MINIMALISM

SIMPLICITY/MINIMALISM

“Less is more”; Using materiality and nature to the its full potential

OPENNESS

Design allows elements to be moved around to create new spaces

MIND AND BODY

“Less is more”; Using materiality and nature to the its full potential

OPENNESS

Blurring the boundaries between the outside and inside through open space

Blurring the boundaries between the outside and inside through open space

Design allows elements to be moved around to create new spaces

MIND AND BODY

Design with the intention of the user’s physical and mental wellbeing

MATERIALITY

Design with the intention of the user’s physical and mental wellbeing

MATERIALITY

The level at which the materials used influences the design

The level at which the materials used influences the design

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 18 19

• Ballarat Community Health Centre DesignInc Studio • Barcelona Pavilion Ludwig Mies Van de Rohe • Fallingwater Frank Lloyd Wright • KAIT Workshop Junya Ishigami • Moriyama House Ryue Nishizawa • Parkroyal Hotel WOHA Treehouse Coliving Apartments BO-DAA Architects # Modernism Unilever Headquarters, Jakarta AEDAS Architects • Villa M House Liag Architects

• PROJECT # IDEA/MOVEMENT/PRACTICE

OF USE OF PRECEDENT IMPORTANCE • Ballarat Community Health Centre DesignInc Studio • Barcelona Pavilion Ludwig Mies Van de Rohe Fallingwater Frank Lloyd Wright • KAIT Workshop Junya Ishigami • Moriyama House Ryue Nishizawa • Parkroyal Hotel WOHA Treehouse Coliving Apartments BO-DAA Architects # Modernism • Unilever Headquarters, Jakarta AEDAS Architects • Villa M House Liag Architects

FREQUENCY

• PROJECT # IDEA/MOVEMENT/PRACTICE FREQUENCY OF USE OF PRECEDENT IMPORTANCE

1: Preliminary Investigations

The purpose of this phase in the research was to recognise the of the concept of ‘urban interiority’ by analysing and gaining a better understanding of Melbourne’s environmental, cultural, political, economic, and ethical issues. This phase explored two topics that ultimately lead to understanding the concept of urban interiority through urban subjects and urban space, within the context of Melbourne, Australia.

URBAN SUBJECTS

The first investigation looked specifically at the idea of ‘urban subjects.’ It sets ut to describe and define the urban subjects and their role in the city.

To understand the concept of urban interiority, I formed a definition of urban subjects as people or objects that contribute to the urban environment one way or another. I then created a taxonomy of urban subjects, identifying the different kinds of urban subjects including people, places, transportation, events, and economy. The taxonomy in the city visualised the relationship of each urban subject to each other.

[16] The

Before defining the meaning of urban subjects, I knew it was important for me to truly understand and define what ‘urban[16]’ is. In my work, an urban subject is considered to be anything or anyone that make up the urban environment and impact the city’s function, structure and form. The function, structure, and form are vital elements of the city.

FUNCTION STRUCTURE FORM

URBAN CITY

Above: Urban city elements

These are the tangible and intangible elements, such as buildings, laws, and parks to name a few, that allow the urban subjects to interact with each other and the city. In developing a taxonomy, I considered the subjects that impact the function of the city. I acknowledged that there is more than just the people that make up the city’s urban subjects as, while they are the main beneficiaries and contributors of the urban environment, there are still other factors that allow the city to function the way it does. Therefore, I identified four more urban subjects to this taxonomy. The second urban subject is the economy, which are establishments, services, and the like that allow the city to run financially and economically. Events are one of the more intangible urban subjects. Events are opportunities for the people to interact with each other and other urban subjects, allowing for a more diverse city. Transportation (and infrastructures) are the means of going around the urban setting, also making up its function, structure, and form. And finally, places are an important factor within the urban subjects. In this project, places are considered anywhere that the urban subjects can meet and interact with each other. In creating the taxonomic diagram, I showed the relationship of the urban subjects with each other, (i.e., what urban subjects impact the other).

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 20 21

Phase

urban setting is anything that helps the environment be liveable and allow people to interact with each other.

PLACES EVENTS

• public vs private

• commercial vs residential

• heritage listed buildings

• educational vs occupational

• cultural

• religious

• music

• festivals

• art

• political

• local

• international

PEOPLE ECONOMY TRANSPORTATION

• demographics

• culture

• occupation

• residency

• businesses

• government

• education

• tourism

• infrastructure

Public Private

• trams

• taxis

• trains

• rideshare

• rental

• car

• bike

• motocycle

• skateboard

The taxonomic diagram revealed that all the different kinds of urban subjects were related in one way or another. For instance, transportations and infrastructures affect the way that people travel within the city. They also affect the economy in terms of public transportation and infrastructure. I concluded that ultimately, the people are at the top of the hierarchy as they are the ones that can actively experience and interact with the other urban subjects and the urban setting, where all the other urban subjects are usually made for them and by them to support a functioning city.

This is not to say though that the other four urban subjects are less important. Without any one urban subject, I believe that the city could not function to its full potential. This interdependence impacts the way that the city functions daily. If one urban subject is not able to perform its role in the city, it creates an imbalance within the city, risking potential issues that the inhabitants could face.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 22 23

URBAN SETTING

Above: Urban subject taxonomy diagram

URBAN SPACE

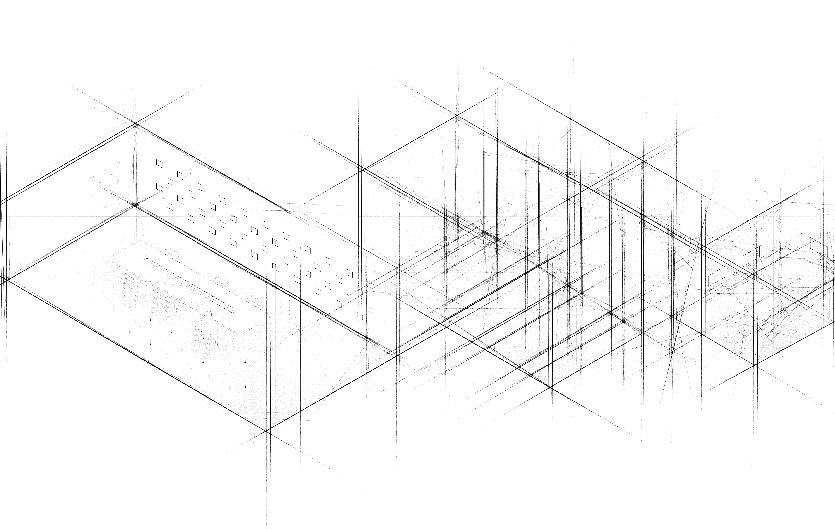

Following the investigation into urban subjects, I then considered the concept of urban space. What are the qualities of urban in general and what are the specific qualities within Melbourne? The primary question here is what, how, why, and when is a city?

This stage took a more creative approach compared to the first investigation. A story of the urban space of Melbourne was produced to understand and explain the urban space. Then spatial and temporal diagrams were made in regard to Melbourne to further analyse Melbourne as a city and its urban space.

Qualities of a Good Urban Space

After understanding what ‘urban’ and ‘urban subjects’ meant, it is possible to define urban space as any space where the urban subjects are given the opportunity to function[17]. These spaces could be open spaces, buildings, and even the in-between spaces within the city – it is where urbanisation is created and fuelled through the different roles of each urban subject. After understanding what urban space is, it was important to consider its qualities; what a city is – its qualities, how a city becomes a city, and when a city becomes a city. Through this reflection, I was able to create a story on Melbourne, showcasing its qualities as a city and its urban space. The story was written from Melbourne’s point of view, which helped me reflect on its spatial and temporal qualities. The spatial diagram included some of Melbourne’s famous landmarks that have become vital to the city’s characteristics, whereas the temporal diagram shows Melbourne’s population growth over the years, which could be a testament to Melbourne’s good urban space and liveability.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 24 25

Diversity of Uses Spaces that stimulate the economy Spaces that allow for social participation Residential • Apartment • Student Housing • Social Housing • Festivals • Rallies • Social and Cultural Events • Improves the environmental features of the city – quality of air – overall climate Infrastructure that allows inhabitants to feel safe Open Space • Parks • Parklets • On-street green space • Vegetation Commercial • Malls & Shops • Offices • Markets • Schools • Restaurants & Cafes ` Infrastructure Environment Above: Diagram of the qualities of a good urban space Right: Spatial map of City of Melbourne’s famous landmarks

[17] A good urban space allows communication, transit, and social interaction of the inhabitants within the city.

Through the research, story, and diagrams, I found that urban space is more than just the city’s buildings and urban planning. It is also about the in-between spaces, open spaces, and little and obscure spaces that are present in the city. By comparing Melbourne to the list of qualities of a good urban space that was identified, I learned about Melbourne as a city and its urban space at a deeper level.

current and upcoming projects. They addressed the current challenges that the city is facing due to the pandemic, their immediate and long-term plans to regenerate the city. They also detailed their aspirations beyond revitalising Melbourne because of COVID-19.

Following Cunningham and McDowell’s presentations, a summary was made on the City of Melbourne’s current challenges and aspirations, focusing on three key points in the presentation. The key initiatives in this investigation, particularly the projects ‘Off the Grid,’ ‘Grey to Green,’ and the COVID-19 action plan, were ones that I believed to be the most important. Images and diagrams were then shown to further explain the observations made from the presentation.

CITY OF MELBOURNE’S PRESENTATION ON CURRENT CHALLENGES AND ASPIRATIONS

Investigation 3 set out to understand the current challenges that face Melbourne following the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown restrictions. By appreciating the current complexities, this investigation also set out to understand the aspirations for the city moving on from the impacts of the virus.

City of Melbourne’s John Cunningham and Lachlan McDowell gave a presentation on the city of Melbourne’s current challenges and aspirations. The talk consisted of the council’s

Before writing a summary on the council’s initiatives for the city, I first identified the projects and challenges that I thought were the most important to me as a designer and as a resident of the city. As previously mentioned, based on the presentation, three key points were identified: “Off the Grid,” “Grey to Green,” and “COVID-19 Impacts.” By choosing and summarising these three key projects and challenges, I understood more on the council’s plan of action for the city, its urban subjects, and its urban space. By having this understanding, I was able to create my own conclusions on Melbourne’s conditions and how they respond to certain issues and challenges beyond its economic and political conditions –i.e., the city’s environment, history, and its people.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 26 27

“[Urban space] is also about the in-between spaces, open spaces, and little and obscure spaces.”

challenge is to make the grid known for the land’s Aboriginal culture and history”

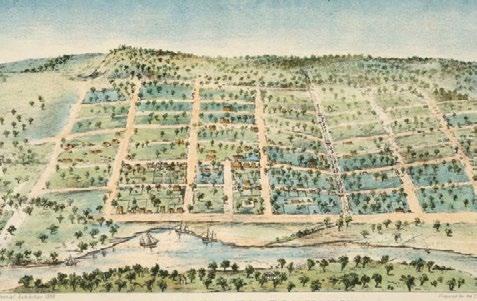

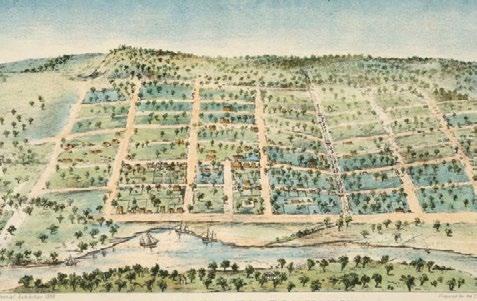

Above: Hoddle Grid circa 1838, designed by Robert Hoddle

Middle: Hoiser Lane, Melbourne, Australia

Below: ‘Little Streets’ city project by City of Melbourne

During the Industrial Revolution of the 1900s, what was once “a landscape untouched by European industry, an undulating expanse of grasslands, forests, wetlands, and rivers managed and lived on by Aboriginal peoples for at least 30,000 years[18]” was built on in a rectangular grid form designed by land surveyor Robert Hoddle. Completely disregarding the Aboriginal History that took place in this land, the British colonisers failed to consider the natural topography of the land and designed Melbourne to accommodate an industrial city. In retrospect, Melbourne’s grid system was designed for the British to expand their colony effectively and efficiently if they wanted to. Today, the council’s challenge is to make the grid to be known for the land’s Aboriginal culture and history rather than its efficiency and its colonial context. The question is how the grid can be “redesigned” or what sorts of interventions can be made to attract people into the city because of its history and culture rather than its efficiency.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 28 29

[18] Greg Hil, Susan Lawrence, and Diana Smith, “Remade Ground: Modelling Historical Elevation Change Across Melbourne’s Hoddle Grid,” Australian Archaeology, 87, 1 (2021): 22.

“The

The Grey to Green initiative is the council’s aspiration to increase the city’s green space, especially as the city’s population increases in coming years, which will likelu result in the need for more high-rise buildings.

Finally, because of the unprecedented times over the past year, the City of Melbourne has faced a lot of negative impacts – from affecting the residents’ mental and physical health, to the decline of the city’s economy. Thus, the council created an in-depth plan for how to respond and recover from the recent pandemic. More importantly though, the council needs to have a detailed plan on how these responses can still be a productive and sustainable solution in the long term. The COVID-19 Reactivation and Recovery Plan consists of four stages in responding to the pandemic, prioritising the public health and wellbeing and the reactivation of the city[19]. The first stage is what they call ‘respond,’ which is their “immediate response to the shock of the pandemic crisis” and is set for the next three months after lockdown. The second stage is the recovery stage, which is set for the next 12 months. This is the short-term response to the continuing impacts of the virus. The third stage is the regeneration stage, which is set out for the next four years after pandemic as the city responds to their understandings of “what was temporary or what will have a lasting impact.” The final stage of this reactivation and recovery plan is the future aspirations of the City of Melbourne, which will take effect over the next 10-30 years. This is the long-term vision in guiding Melbourne to be more resilient in the future[20]. For each of the stages, the council works on seven initiatives that are integral to the immediate recovery of the city and regenerating and creating a resilient city[21].

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 30 31

Above: New open space and trees at Dodd Street; Public Art in Southbank project

Middle: Sketch of new Southbank Promenade Project

Below: New park at Market Street Project

[19] City of Melbourne, COVID-19 Reactivation and Recovery Plan: City of the Future, (2020), 4-5.

[20] City of Melbourne, COVID-19 Reactivation and Recovery Plan, 21.

[21] City of Melbourne, COVID-19 Reactivation and Recovery Plan, 23.

COVID-19 REACTIVATION AND RECOVERY PLAN

RESPOND

NOW RECOVER 1 YEAR REGENERATE

4 YEARS

FUTURE ASPIRATIONS

10-30 YEARS

immediate response to the effects of the pandemic (within the next 3 months)

short-term respnse to the continuing impacts

medium-term regeneration. Understanding temporary and lasting impacts

long-term vision for Melbourne’s future

Prioritise Health and Wellbeing

Reactivate the City Build Economic Resilence Expand Equal Opportunity and Access

Transform our Spaces and Buildings

Strengthen Community and Align with Others Evaluate, Measure and Progress

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 32 33 Above:

and

Plan

COVID-19 Reactivation

Recovery

via City of Melbourne

3

1 2

4 5 6 7

The presentation and the summary gave me an insight as to what aspects the City of Melbourne prioritise. These priorities lie within the areas of environmental and the culture, together with the economy and health. I realised that the City of Melbourne, more than ever, is trying to achieve a sustainable and environmental city, especially with all the initiatives regarding green space, which goes beyond the ‘Grey to Green’ project. By doing so, they are working towards improving the people’s mental and physical wellbeing.

Through this phase of the research, I gained a deeper understanding on the concept of urban interiority, and especially Melbourne’s urban interiority. Especially after completing the first two investigations, I learned that urban subjects and urban space need each other to have a wellfunctioning city. No one is more important than the other, they must work together to take care of each other. This is especially important to understand as it will help in the design phase –to know who and what the proposal is designed for, where it is designed and how it will be executed. This phase gave me more of an insight on Melbourne beyond the economic and political aspect – it taught me more about Melbourne’s sustainability, liveability, culture, and history. This phase provided a detailed background on Melbourne. By having knowledge on the projects and challenges that Melbourne is currently facing, I was able to acknowledge what the city needs to reach their goal, which is to attract people into the city, which ultimately helps in the experimental design phase.

There are some aspects in this phase that did not have a positive result. For instance, the second investigation would have been more successful if the visual presentation of the story of Melbourne and the diagrams made were more complex and experimental. It would have given more insights on Melbourne, beyond the built environment and the demographics. Moreover, a better understanding on what spatial and temporal would have resulted in a much more effective findings for this phase.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 34 35

“The City of Melbourne, more than ever, is trying to achieve a sustainable and environmental city.”

Right: Proposed open space in front of the ABC Southbank Centre

Phase 2: Towards a New Urban Interiority

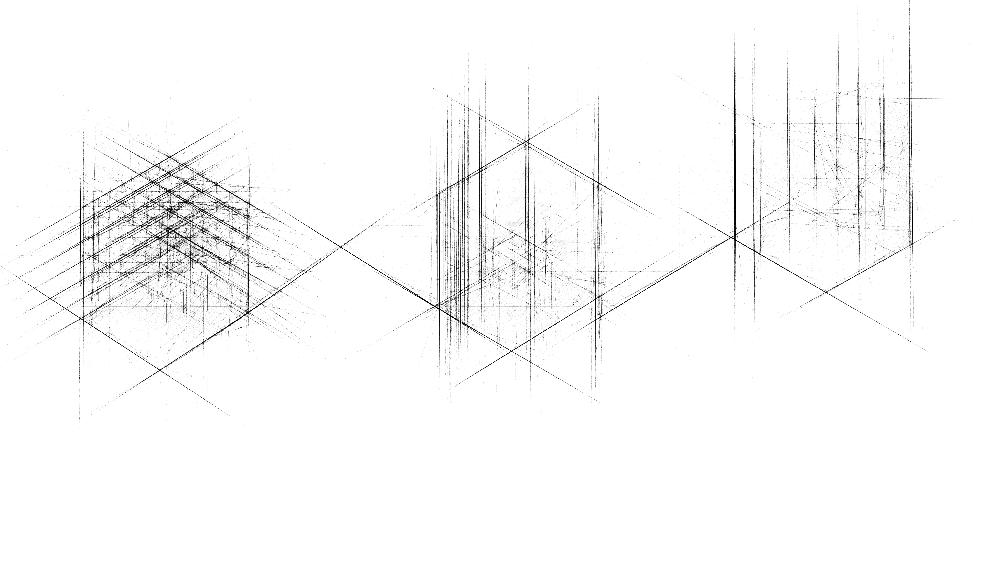

The purpose of this phase was to create and propose a new urban interiority for the City of Melbourne through an experimental design phase. Following the first phase of the project, it was then possible to address the current situations that the City of Melbourne is facing through the lens of this new urban interiority. This phase explored different ideas and potentials for the City of Melbourne. The objective was to intervene in the City of Melbourne’s urban environment through an Interior Design approach, which is best achieved by inventing a new urban interiority. By experimenting with the interiority of Melbourne’s urban space and environment, we can shift the focus from the political and economic liveability of the city to the personal temporal experience of the inhabitants of the space.

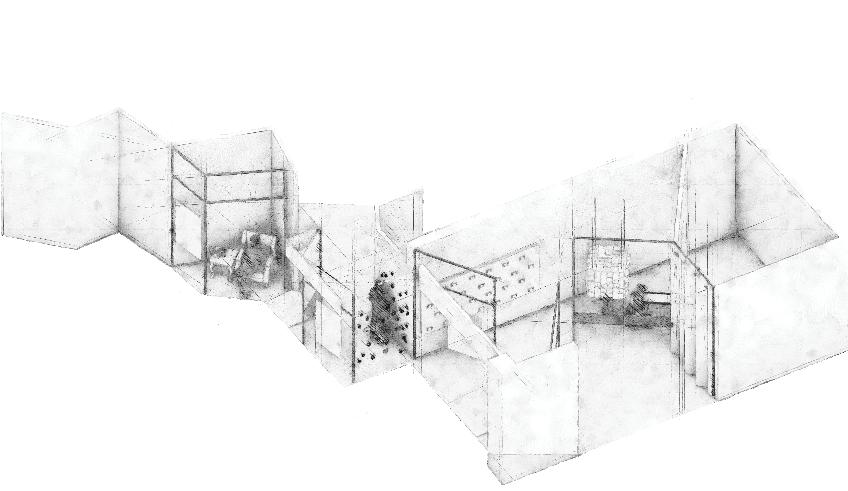

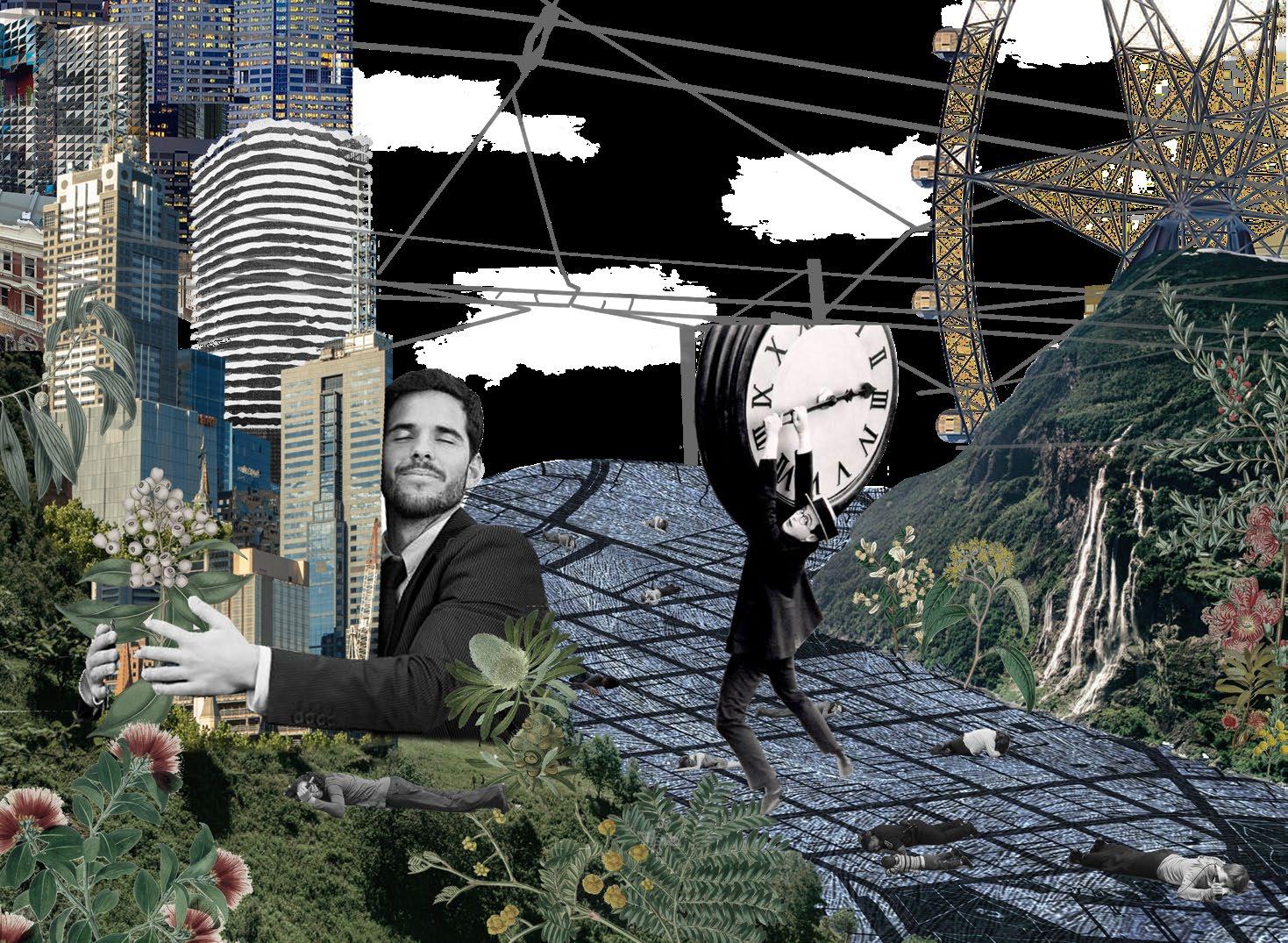

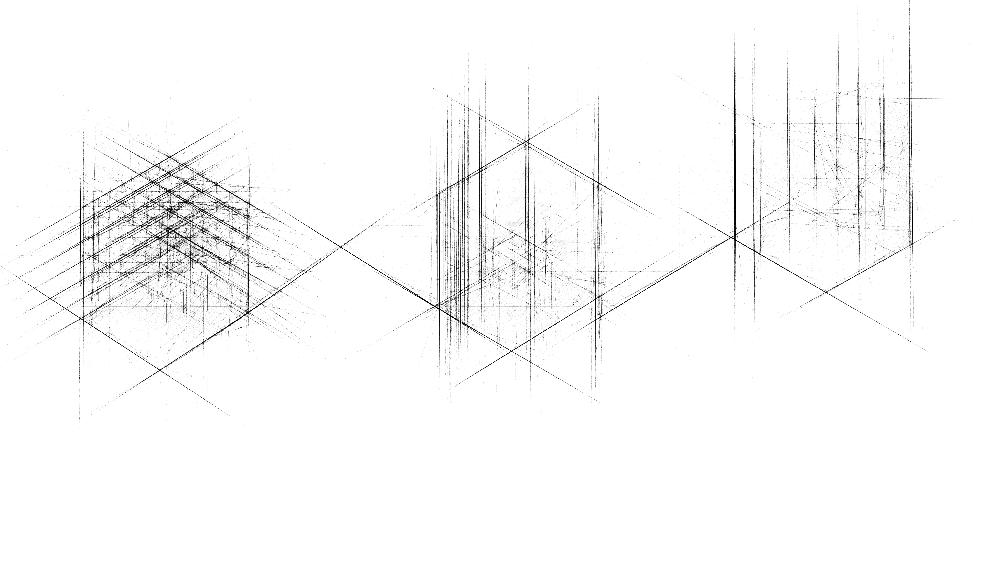

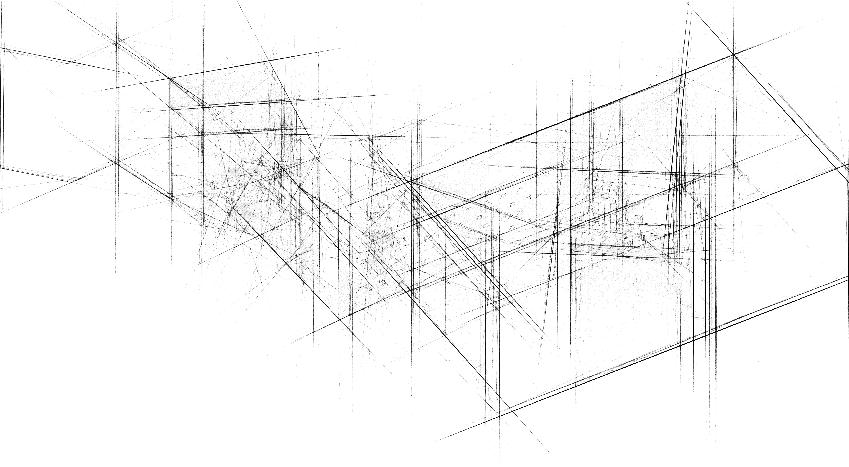

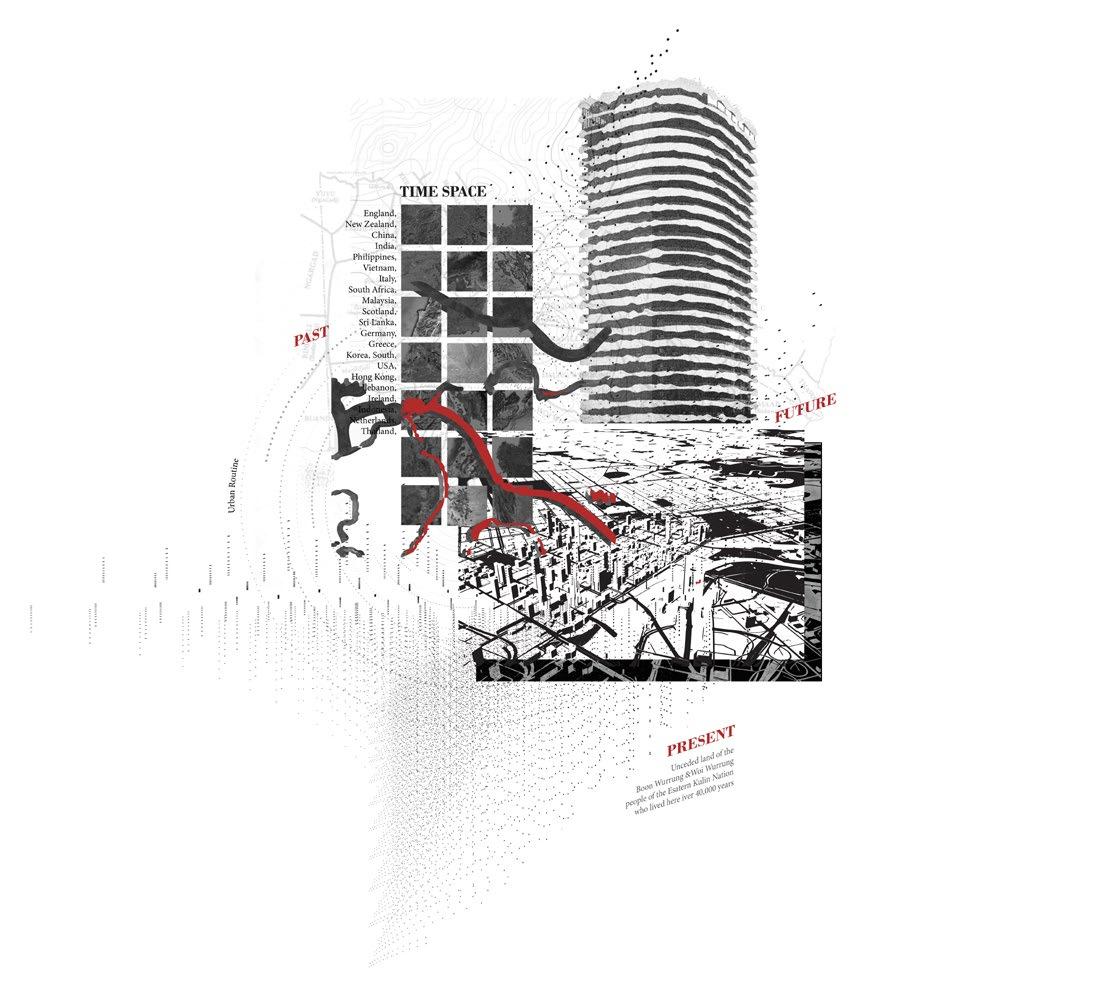

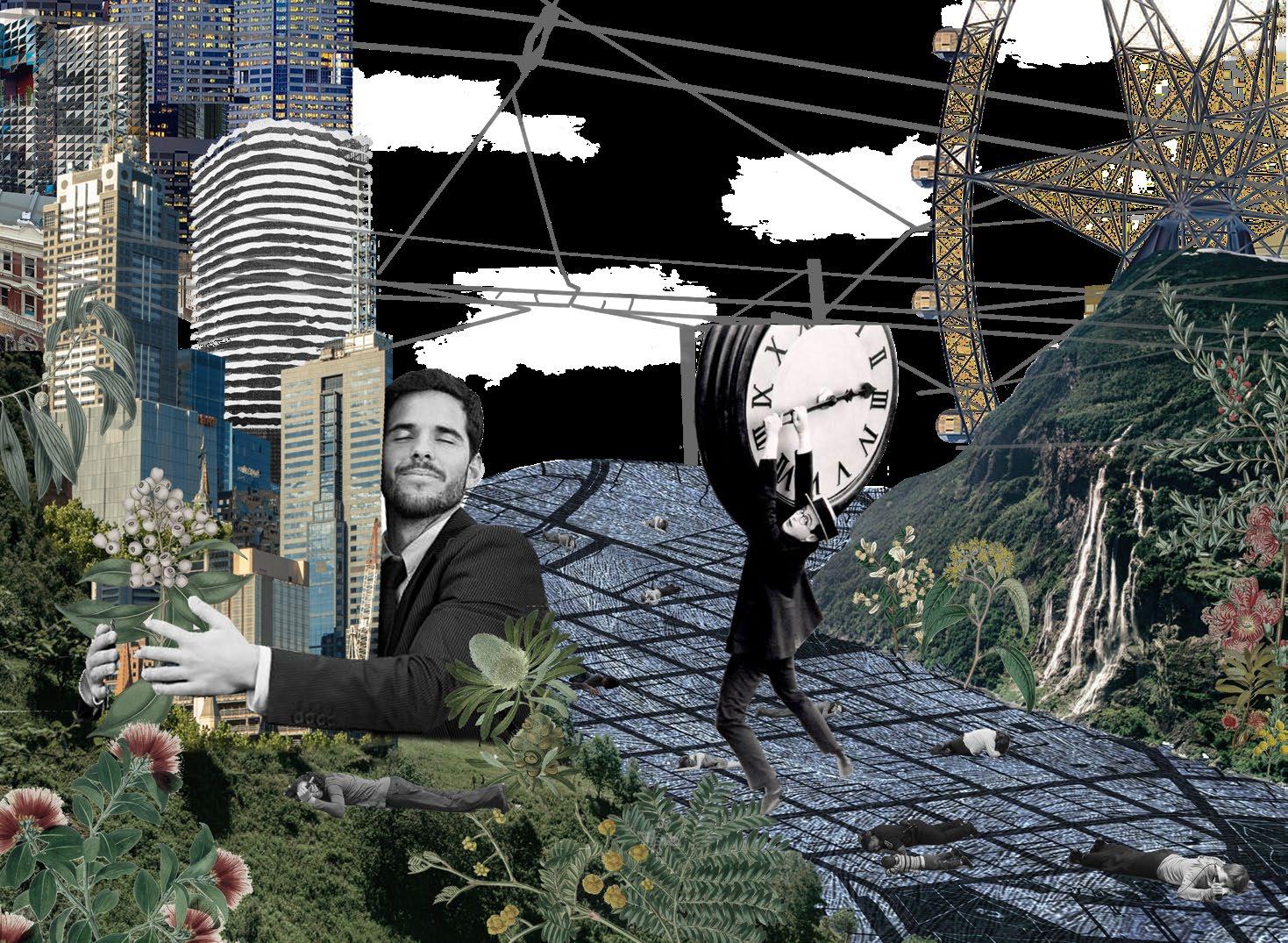

In this phase, a proposal for a new urban interiority was made through a series of works. Firstly, a manifesto was made to clearly explicate the team’s belief and arguments on the concept that has been made. A proposal was then explored through a series of visualisations: a mood board showing the urban interiority’s mental, social, and environmental ecologies, a collage visualising the group’s overall concept, and a spatial and temporal diagram in relation to the suggested urban interiority and Melbourne.

The first step in forming a concept for a new urban interiority was to come together to describe what each team member’s ideal city was. The team shared three qualities in common in creating a good city and clearly defined these qualities in our own understanding: curiosity[22], autonomy[23], and safety[24]. After identifying these three characteristics, diagrams were created showing how each of the three qualities relate to each other.

36 37

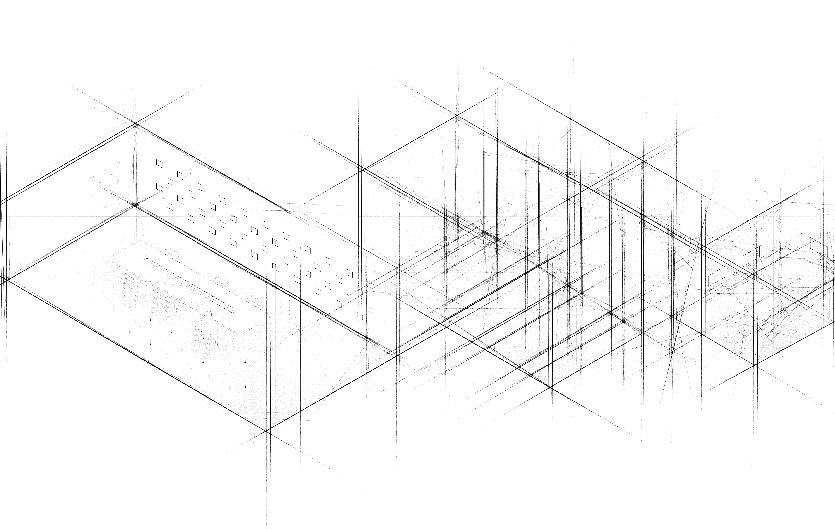

Right: Spatial and Temporal Cartography of the new urban interiority

[22] A sense of discovery; being able to search for the unknown and the unfamiliar [23] A freedom to choose to be a part of something [24] A sense of security; not feeling vulnerable or threatened in the city

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 38 39

Concept visualisation for the new urban interiority

However, after much discussion, the group faced a roadblock in which we could not come up with a consolidated concept for the urban interiority. This is because we did not first consider some of Melbourne’s existing situations. Identifying an existing condition is a vital step in the process as it helps in defining who the design is for, what the design will be and where it will be. Thus, we took a step back to discuss this, and identified a current situation that we felt strongly as a group, which is to make Melbourne memorable, especially to its temporary inhabitants. As temporary inhabitants of the city, we felt it was important to make the city have a lasting impact on the people who visit or reside there to maximise their experience in Melbourne – especially because these are the people who go into the city with the initial intent to leaving it at one point.

Through this step, we were able to create a proposal for a new urban interiority, titled A Temporal Citizenship: Towards an Empathetic City. A temporal citizenship is the notion that any inhabitant of the city can feel a sense of belonging and free to participate and engage with the city, beyond its economic and political aspects. Through this new urban interiority, we wanted to shift our design focus from efficiency into designing for experience. This notion of “temporal” allows us to have a long-lasting relationship with the city and vice versa.

It was more evident in this phase to clearly define a glossary of terms on concepts as our group found that some terms are understood differently than others. For instance, as a group, it was especially important to us to clearly define what citizenship meant for us, as the common definition for citizenship is normally tied to the political and economic aspect. As mentioned earlier, identifying the three characteristics of a good city (prior to Melbourne’s current situation) made it difficult for the group to create an overarching concept for a new urban interiority, this is because we went straight into recognising the specifics before the general issues. In retrospect, I would first find the general existing issues that the city is facing before diving into the specific concepts and designs. However, in saying that, I do not discredit the importance of the three characteristics that the group has made as it gave the group ideas on how we ultimately came up with this notion of a temporal citizenship. Moreover, I believe that these concepts of curiosity, autonomy, and safety could be vital factors in creating a new design for the City of Melbourne in the next stage of the project.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 40 41

“This notion of ‘temporal’ allows us to have a long lasting relationship with the city.”

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 42 43

“shifting our design focus from efficiency into designing for experience”

Moodboard for the new urban interiority

Phase 3: A New Urban Interiority

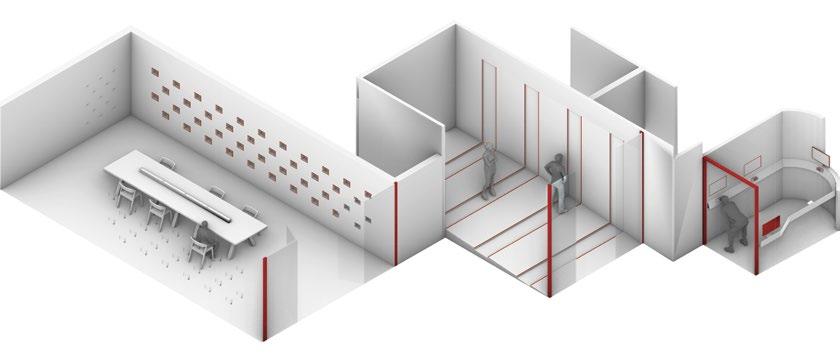

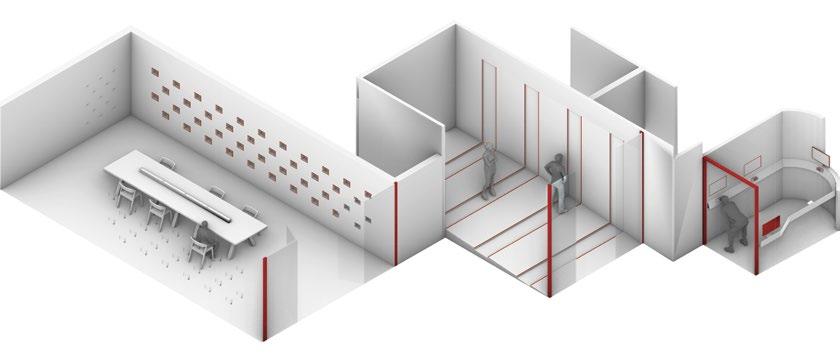

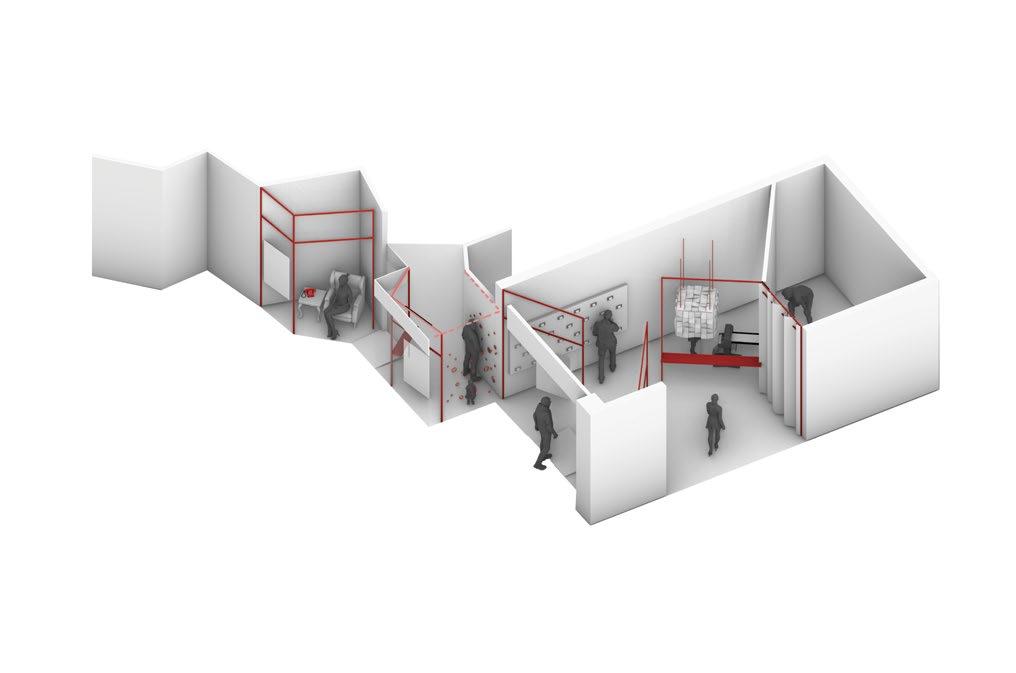

Following the previous phase, the final stage of this project was to continue and expand on the experimentation and proposition into a fully articulated design proposal for Melbourne as a pitch to the City of Melbourne. The objective was to address the city’s current situation through a realised intervention, but also considering how this intervention can still work for Melbourne in the long term.

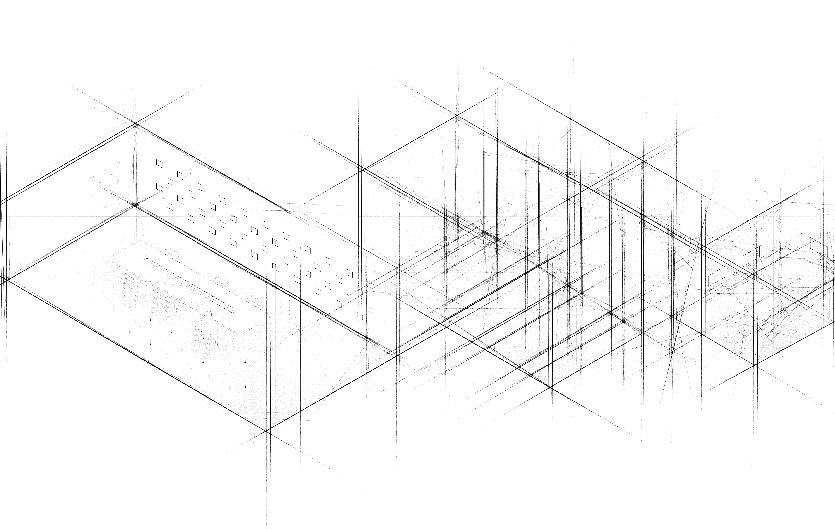

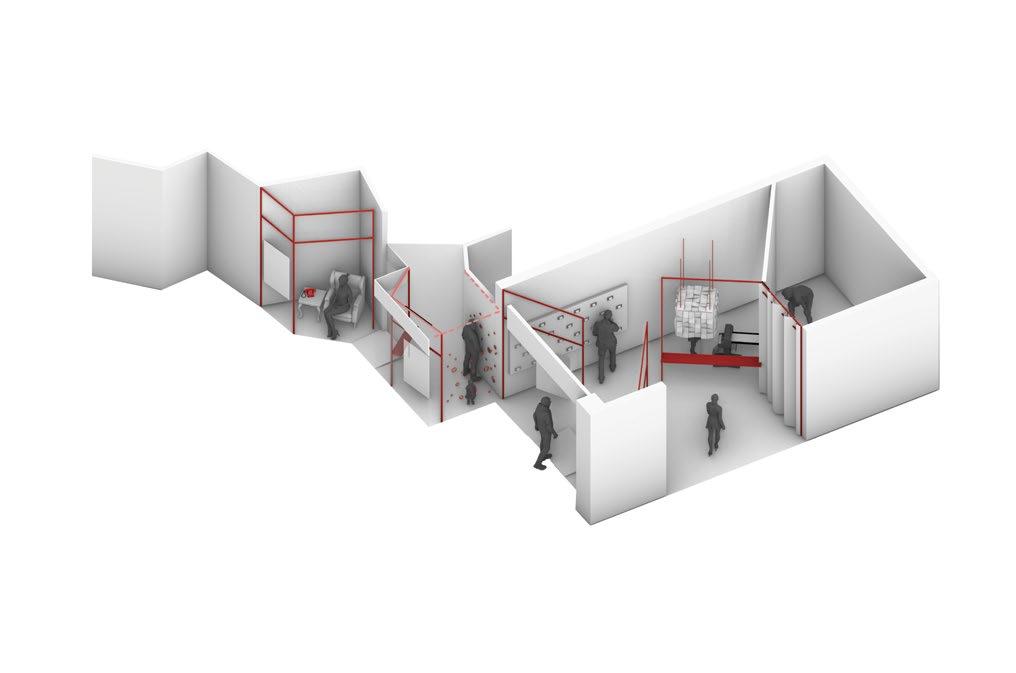

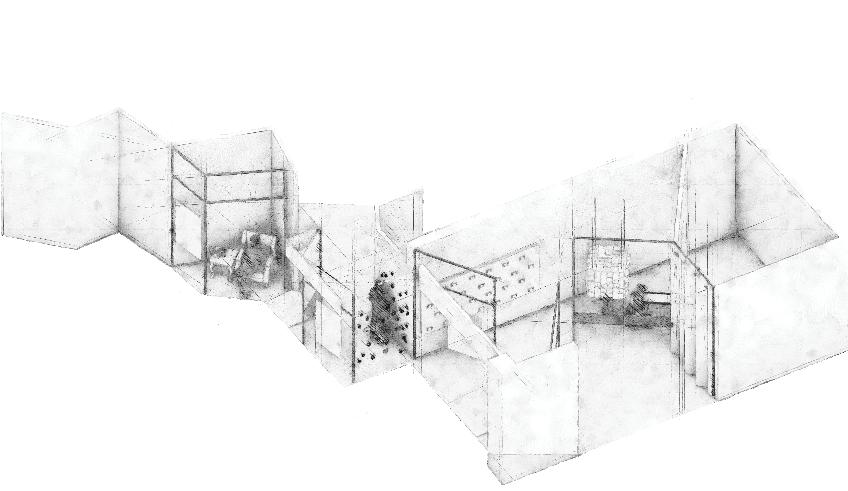

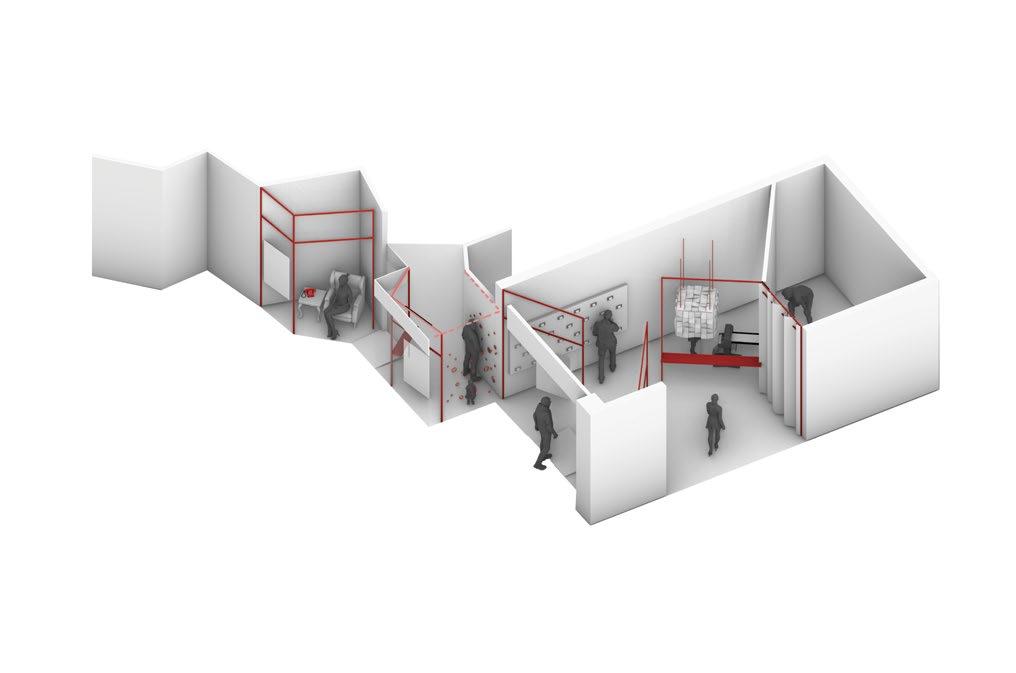

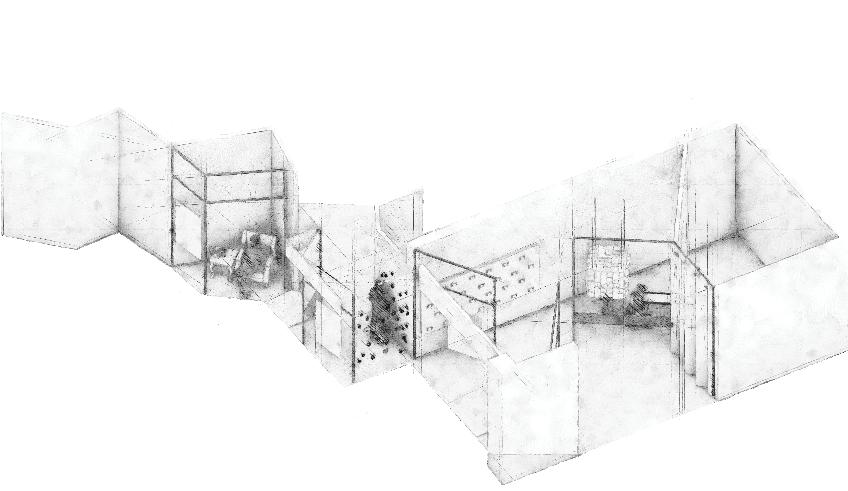

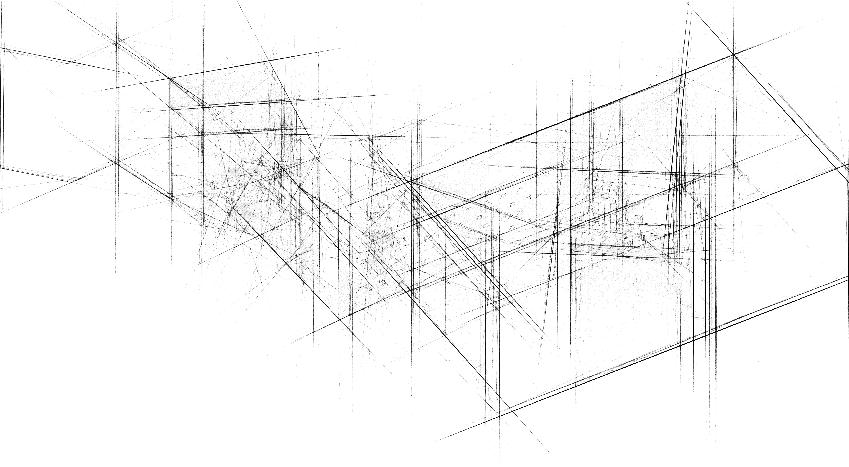

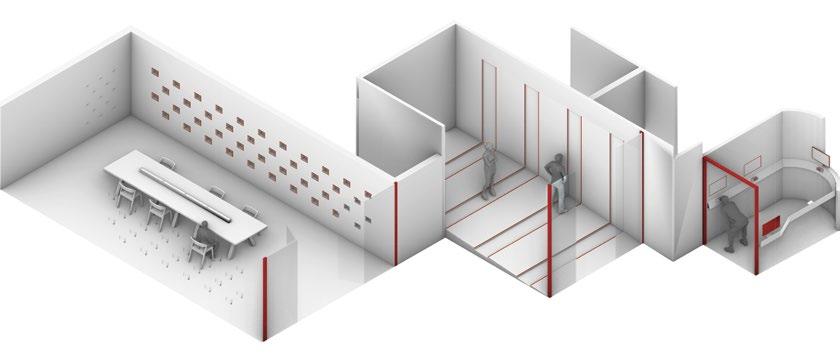

Drawing on the results from the previous phase, the team created a design proposal for the new urban interiority: Temporal Citizenship: Towards an Empathetic City. A series of drawings, diagrams, and visualisations were made to communicate the design proposal and the strategies made in creating the intervention.

SITE SELECTION: MORE THAN JUST ECONOMIC EXCHANGE

Before working on the design, the team did a series of dérives around the city, particularly the CBD, to understand the conditions of the city – how people use different parts of the city, where in the city receive the most foot traffic, and the overall environment of the city. From these dérives, we concluded that there is a huge disconnect with the city. Many of the people around the city are simply getting to their destinations without actually noticing and experiencing their surroundings. From this, we realised that this notion of Temporal Citizenship does not necessarily have to be obtained by international inhabitants (i.e., international students and workers), as many of those who are currently inhabiting the city do not even have this connection with the city.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 44 45

Left: Closed down currency exchange booth in EzyMart repurposed to display cereal boxes

Right: Current condition of the currency exchange stores and booths

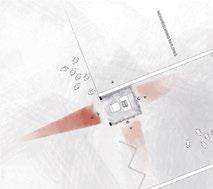

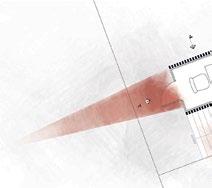

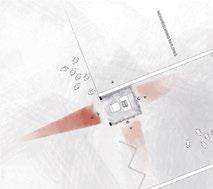

In selecting the sites, we chose the stores along Swanston Street as this street is usually packed with people. Swanston Street is the longest street in the City of Melbourne and can be considered as the spine of the city. Because it stretches from St. Kilda Road all the way to College Crescent in Carlton, Swanston Street sees many diverse experiences. We decided to locate our interventions along this street and add on to these experiences.

As we walked along Swanston Street, we noticed that there were many currency exchange stores and booths that were either closed or closing down. Currency exchange has this nature of international exchange within the city. However, with the economic impact of COVID-19, these stores and this act of exchange have started becoming obsolete as travelling in and out of the city has been put to a sudden stop, forcing these stores to close or move online. Thus, following the nature of international economic exchange, we decided to use these stores and booths as our locations to articulate the notion of exchanging experiences, ideas, and cultures. Our strategy for this project was to create situations that would disrupt people’s static flow of moving from point A to B.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy

46 47

Cha

“following the nature of international economic exhcange ... our locations articulate the notion of exchanging experiences, ideas, and cultures”

Swanston Street site selection

CONVERSATIONS WITH MELBOURNE

In creating the program, we first took a step back and reflected more on the concept of temporal citizenship. The question “what makes people feel they have temporal citizenship?” allowed us to then create experiences for this to happen. Elevating our initial ideas on temporal citizenship, we believe that to have a temporal citizenship means that the individual is able to grow and continue to grow with the city, freely participate and interact with the city and other inhabitants, have a say in community matters, and learn and live with the history, culture, traditions, and lifestyles of the city.

From there, we asked what kinds of experiences we can create to allow people to have this sense of temporal citizenship. With the concept of temporal citizenship, it made sense for u to design a program of situations rather than structures. Moreover, keeping in mind the three qualities of a good city, our group designed programs and spaces that allow people to have the freedom to feel safe and comfortable in sharing and participating in this program, while sparking curiosity through the design of the interventions.

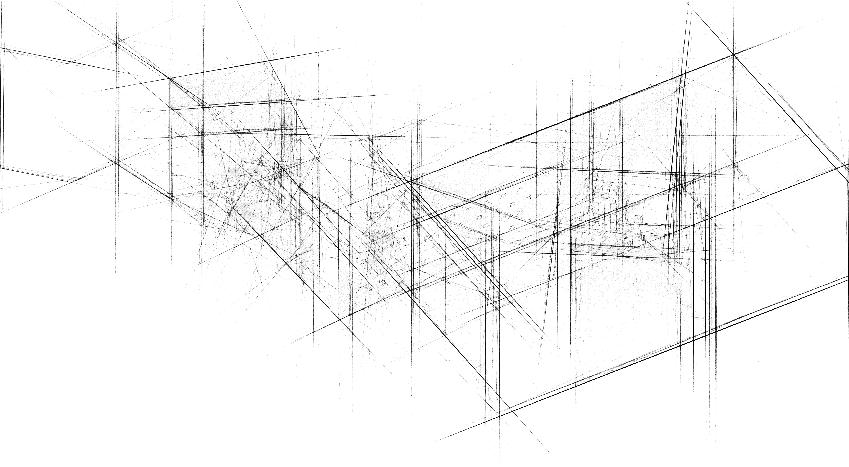

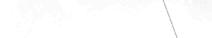

Through these questions, we were able to create a realised design proposal for our urban interiority. In three phases: collection, activation, and circulation, the program, particularly the first and second phases, was further divided into nine interventions in the selected sites that drew focus on three important acts: saying, seeing, and listening. These three actions are very commonly used actions that we normally end up just going through these motions. Through this program, the group articulated the importance of these actions in exchanging experiences with the city by creating different ways of saying, seeing, and listening. The objective of this project was not to educate people on the City of Melbourne, but to encourage people to think beyond themselves and more about the other citizens and the city that they live in.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 48 49

BEYOND ONESELF

THINKING

Program timeline diagram

“What makes people feel they have temporal citizenship?”

To

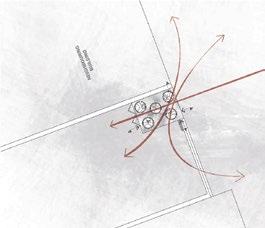

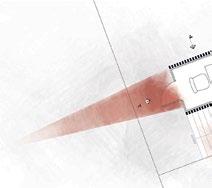

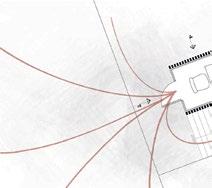

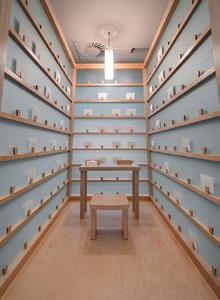

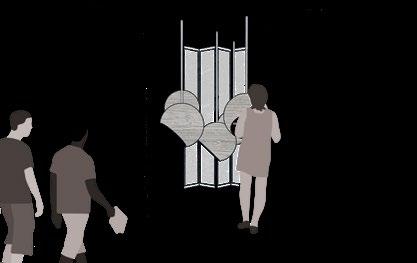

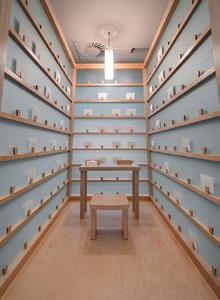

PHASE 1: COLLECTION

This first phase focuses on the act of saying. In three of the selected sites, we created interventions that allow the inhabitants to freely share their concerns, testimonies, stories, and experiences in response to prompt questions and statements in relation to the City of Melbourne. As previously mentioned, there are a multitude of ways in responding to the prompt questions. So, we designed three spaces that allow people to share their responses in different ways: typewriting, letter writing, and speaking through a phone[24]. Taking advantage of the size of the currency exchange booths, these spaces are designed to only fit one person at a time for them to first create and have their own experiences without influence from other people, before being able to share them with others and gain new experiences with others.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 50 51

[24] Taking inspiration from Sheryl Oring’s idea of taking an interiorized object from I Wish

Say, there is a juxtaposition in bringing activities that are normally done in closed intimate spaces in such public spaces, which sparks curiosity with passers-by.

Left: Aman Mojadidi, Once Upon a Place, 2017

Middle: Lee Mingwei, The Letter Writing Project, 1998-ongoing

Right: A letter from Sheryl Oring’s I Wish to Say

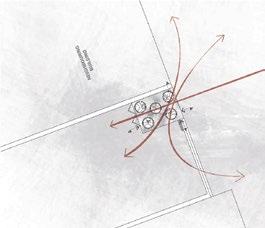

Top Left: Movement diagram for 250 Swanston Street

Top Right: Visual threshold diagram for 250 Swanston Street

Middle Left: Movement diagram for 186 Swanston Street

Middle Right: Visual threshold diagram for 186 Swanston Street

Bottom Left: Movement diagram for 65 Swanston Street

Bottom Right: Visual threshold diagram for 65 Swanston Street

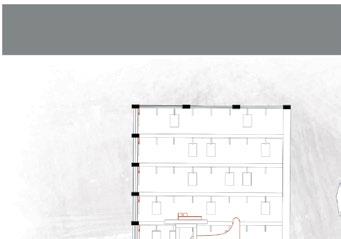

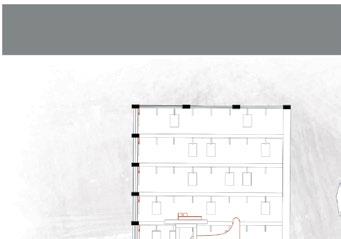

Top: Sections, 250 Swanston Street

Middle: Sections, 186 Swanston Street

Bottom: Sections, 65 Swanston Street

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 52 53

“first create and have [your] own experiences without the influence from other people, with with others and gain new experiences.”

Left: Typewriting, Saying Intervention

Middle: Letter Writing, Saying Intervention

Right: Phone booth, Saying Intervention

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 54 55

PHASE 2: ACTIVATION

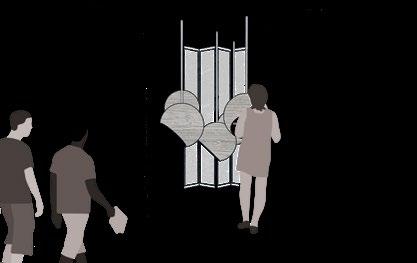

The activation phase draws focus on listening and seeing. After the organisation collects enough responses, these responses are then disseminated into different ways of listening and seeing. These acts of listening and seeing are other ways of exchanging experiences –this time, they are receiving them. Three sites were designed in experiencing these responses through listening: whispers through the wall, hearing oneself talk through an enclosed box, and answering the phone. At the same time, three sites were also designed in experiencing through seeing: reading the responses through screens that go around the walls and floor of the room,

interpreting the written responses through art, and seeing and reading a video of the response being written through a telescope. The people are able to understand and take in what others feel about the city and the experiences they have as a member of the city. The team’s intention behind this phase was that people learn from these stories, or they may be able to relate to them, allowing them to interact with the other citizens of the city, whether they personally know them or not.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 56 57

QVShoppingdistinct

titutioncollegeandIns

City Sqaure Motel

Above: Movement plan diagrams through listening installations

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 58 59

Listening interventions

AI DATABASE

[25] Because of the abundance of currency exchange stores and booths in the city and because of their size, it is very easy for them to go unnoticed by the pedestrians.

PHASE 3: COLLECTION

Following the previous phase of this research, we still recognise the importance of unfamiliarity. We concluded through various dérives around the city and conversations with our peers that when something stays in place for too long, the people, especially who are in the city longterm, will start to have this sense of familiarity, risking these spaces to almost go unnoticed, much like the currency exchange booths[25].

Top: Perspectives for postcard, Seeing Intervention

Middle: Perspectives for screen, Seeing Intervention

Bottom: Perspectives for video, Seeing Intervention

So, after some time, the hope is that the participants of the project would have a better understanding and appreciation for the city and would want to participate and even ask new questions to the city and its members. This part of the program, while realised in the far future, is an important form of exchange as this part shows the true engagement and participation of the inhabitants.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 60 61

CREATING A DESIGN LANGUAGE

As these interventions are sporadically spread around Swanston Street, it was important to make the people realise that these programs relate to one another. To communicate these ideas, there were specific elements in each intervention that were injected in other interventions. For instance, one of the programs in the first phase instructed people to pick up a phone and voice their concerns as if they were talking to someone on the other line. When it came to designing the listening programs, it was a no brainer to incorporate this into the design. The typewriting and letter writing were designed to be produced on postcards, which were also used in one of the seeing interventions where the visitor through art.

TEMPORAL CITIZENSHIP: TOWARDS AN EMPATHETIC CITY

Going through this project gave me a deeper understanding of what temporal citizenship is. Temporal citizenship is more than just being able to interact with the city, but also being able to grow within the city and with the city. Creating a program allowed the team to communicate and articulate our vision for this new urban interiority in the best ways possible. The idea of temporal citizenship is that people should be able to participate and interact with the city, thus having such interventions and installations that really allow people to go beyond just simply hearing and seeing the installations and actually participating in them was almost like allowing the people to help design the intervention as they are vital roles in allowing for a next phase to happen. Moreover, drawing on what temporal citizenship is, designing a program that allowed people to share their stories and concerns to the community could make them feel like they belong in this community, without having to rely on the political benefits of an Australian citizen, which is essentially what temporal citizenship stands for.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 62 63

“The idea of temporal citizenship is that people should be able to participate and interact with the city.”

The recent pandemic has suddenly put a paise in accepting new and returning inhabitants. Now, more than ever, did we realise the value that every inhabitant has in contributing to the function of the city, whether one is a permanent or temporary resident. The objective of this research was to realise and appreciate the conapt of urban interiority through an articulated design proposal.

The preliminary investigations helped me in understanding what urban interiority is and what it stands for allowed me to go beyond designing structures and spaces that are enclosed in four walls. Through this process, I realised that Interior Design also entails designing people’s experiences, whether they are indoors or outdoors.

Temporal citizenship challenges the common idea of a citizen[26] to a form of ephemeral and situational citizenship. It is anyone that can freely interact with the city and participate in city and community matters beyond its political and economic factors, but also through socio-cultural ways. This notion gives the citizens the freedom to create their own experiences in the city.

This project was designed to be experienced today and in the long-term. It goes beyond creating interventions to respond to the impacts that COVID-19 has placed onto the City of Melbourne. Putting emphasis on the concept of temporality, this program hopes to have this constant back and forth exchange between citizen to other citizens, authorities, and the city (and vice versa).

Beyond the physical transformation of Melbourne, this program of getting people to respond and listen and/or see others’ responses can bring the people of Melbourne together. When inhabitants, whether they are Australian or not, permanent resident or not, are able to come together as a community, they can transform Melbourne in ways that is truly thought of for them and by them together with the government. Instead of a “topdown” tactic of planning for a city, having this sense of temporal citizenship can help people to want to participate in community matters, which practices a more inclusive “bottom-up” strategy of creating a better Melbourne.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 64 65 Conclusion

[26] According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, a citizen is a “member of a political community” who is “free to act according to the law and having the right to claim the law’s protection.”

Temporal citizenship challenges the common idea of a citizen to a form of ephemeral and situational citizenship.”

Annotated Bibliography

The Subjective City: Towards a Reconceptualization of Urban Interiority

Atiwill, Suzie. “The Subjective City: Towards a Reconceptualization of Urban Interiority,” in The Interior Urbanism Reader, edited by Gregory Marinic. UK: Routledge, 2021. In this source, Atiwill[27] argues to rethink the idea of ‘subjectivity’ in terms of urbanity and the city. For most of the chapter, the author references many key sources from different authors on their views on topics in relation to ‘urban’ and ‘interior’, which allows the reader to find the relationship between interiority and urbanism. From there, the author was able to draw a conclusion on how to reconceptualise the idea of a subjective city to be more about the interiority, which she relates to as “something that belongs to the experience of the individual.” This reference is useful in this research paper as it gives a comprehensive insight into what has already been talked about in terms of urban interiority. It could give the writer a clearer understanding on other views on this topic beyond Atiwill’s argument.

an environment that does not normally encourage that. This article is helpful in this research as it shows how different authors interpret the concept of urban interiority beyond its definition and theory. While I do recognise that this article is talks about something that is a temporary installation, it could still be a good source to use to argue how different urban interiorities are made within the urban environment through different methods.

[27] Suzie Atiwill is a professor in Interior Design and has authored many journal articles and given many talks regarding the concept of urban interiors and urban interiority, which tells us that she is very well-versed in this topic.

Wellbeing and the Environment

Cooper, Rachel, Elizabeth Burton, and Cary L. Cooper. Wellbeing and the Environment. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

Inside Out: When Objects Inhabit the Streets

Coombs, Gretchen. “Inside Out: When Objects Inhabit the Streets”. Idea Journal 15 no. 1 (2018):90-101. https://doi.org/10.37113/ideaj.vi0.55.

[28] Coombs’

This journal article analysed two art projects that dealt with public participation. The article investigated how a participatory art project could transform into an urban activation by displacing what are normally interior objects into the urban environment. The author[28] notes that when interiorised practices and objects are brought outside, allows interaction among the inhabitants in

The essence of this book is about how different environments affect and effect the human wellbeing, both psychologically and physically. It investigates how humans engage with their environment, the type and quality of the environment, and consequently how the environment impacts people throughout their life. The focus of this book is to enlighten the readers as to what a city must achieve in order to produce a healthy environment for the inhabitants. It is a good source to cross reference with factors that Melbourne already has to make a good urban environment for its inhabitants and what they might need to improve physical and mental wellbeing of those who visit and stay in the city. This book talks about a wide variety of environments, but I want to mainly focus on chapters where the authors talk about the city and open spaces.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 66 67

interests include art and design and their relation to socialism, which is reflected well in this article and many of her other works.

“E-Urbanism”: Strategies to Develop a New Urban Interior Design

Di Prete, Barbara, Davide Crippa, and Emilio Lonardo. 2018. “’E-urbanism’: Strategies to Develop a New Urban Interior Design”. Idea Journal 15 no. 1 (2018) :14-27. https://doi. org/10.37113/ideaj.vi0.46. This article looks into different marketing strategies such as placemaking, place-branding and crowdfunding in order to make inhabitants pay attention to their surroundings more as the authors believe that at this point in time, we rarely stop and appreciate the cities that we live in, only paying attention to a small percentage of it. From reading this article, I found that in the three main strategies they looked at, it did not necessarily relate urbanism to the practices of Interior Design as much. However, what the authors do note is that there are many ways to create this sense of urban interiority within the citizens as they are able to interact with each other in a way they could if they were in an enclosed space. Just like the article Inside Out: When Objects Inhabit the Streets by Coombs, this is a good source in understanding a new way of interpreting the idea of urban interiority.

Urban Interiors: A Retroactive Investigation

Leveratto, Jacopo. “Urban Interiors: A Retroactive Investigation.” Journal of Interior Design 44 no. 3 (2019): 161-171.

[29] Jacopo Leveratto has a doctorate in Architecture and is an associate professor of Interior Architecture in Politecnico di Milano. Much like Atiwill, many of his works study the urban environment and its relations with interiority and Interior Design.

This paper investigates the concept and idea of urban interiority through a critical historical reading of urban interiors. The author[29] argued that while the practice of urban interiority is somewhat new, the relationship of urban and interiors is not. Thus, in understanding what urban interiority is, it is important to know how it came about. This reading is a good way to do that as the author was critical and comprehensive about many of the historical contexts of urban interiors that have been

referenced across numerous of resources that I have seen such, especially from designers and philosophers like Walter Benjamin, Camillo Sitte and Giambattista Nolli. Leveratto argues that throughout the history of urban design and planning, many designers have already argued for the interiorisation of the urban environment. This article is a good way to understand the theory of urban interiors, and consequently, the concept of urban interiority.

The Public Interior: The Meeting Place for the Urban and the Interior

Poot, Tine, Maarten Van Acker, and Els De Vos. “The Public Interior: The Meeting Place for the Urban and the Interior”. Idea Journal 15 no. 1 (2015):44-55. https://doi.org/10.37113/ ideaj.vi0.52

This article argues that publicly owned spaces like arcades, passages and outdoor spaces also fall into the category of public interiors. Throughout the paper, the authors talk about how Interior Design – its beliefs and practices – can help develop public interiors in order to create a direct impact with the urban environment. Much like other works that talk about urban interiority, the authors want to change the connotation of ‘interior’ as being confined in four walls. This is a good source to go back to as it literally talks about how interior architecture/design can be of good practice when designing and thinking about the public sphere and into a bigger scale, the urban environment. This is a good reading to reference in terms of how the inside and outside blend together as it also talks heavily on that topic.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 68 69

Understanding Urbanism

Rogers, Dallas, Adrienne Keane, Tooran Alizadeh, and Jacqueline Nelson. Understanding Urbanism. Singapore Springer Singapore Pte. Limited, 2020. This book first talks about the difference between urbanisation and urbanism, which is important to understand as to not confuse the idea behind the two concepts. Focusing though on the concept of urbanism, the authors give a detailed explanation of what urbanism is and what it entails in the first part of the book. Thus, by understanding the concept, theories and practices regarding urbanism, we are also able to understand cand analyse cities, its inhabitants and also the built environment. The book then presents 13 key urbanism ideas and themes, discussing each theme, their key debates and some critical evaluation on it. I particularly find this book a useful source to this research as it examines different examples of urbanism themes through different types of cities. From this, I will be able to understand Melbourne as a city and its urbanism.

Urbanism

Rudlin, David, Rob Thompson, and Sarah Jarvis. Urbanism. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Urbanism is a collection of places such as cities, neighbourhoods and towns, which are shortlisted and possibly awarded by the Academy of Urbanism. Each chapter of the book talks about a place and the characteristics they have in order to be considered to have good urbanism. I want to focus my attention on the chapters that talk about cities with good urbanism as this is what the research is mainly on. This is a reliable source as it gives unbiased evaluations that the Academy of Urbanism follows a certain process in shortlisting the cities for them to be considered to have good urbanism. I particularly find that this could be a strong reference as the cities that are

mentioned in this book can be cross referenced with the characteristics that Melbourne has as a city to gauge its quality in terms of urbanism. From there, the research could talk about what Melbourne may or may not need to improve or retain its quality of urbanism based on the findings I gain from this source.

The Open City

Sennett, Richard. “GSD Talks: Richard Sennett, ‘The Open City’”. Harvard GSD. 24 October 2017. YouTube Video. 1:33:47. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7PoRrVqJFQ.

[30] Many of Sennett’s recent works and talks also are about the city and its people. Because of his Economic and Socialism background, his take on the city and how it could be designed is very much centred on a more socialist point of view.

This source is an hour long talk that urbanist and sociologist Richard Sennett[30] gave to Harvard Graduate School of Design. In this talk, he argues that modern cities do not allow for a deeper experience for the citizens. Sennett believes that cities should be a place wherein everyone is able to have a positive and deep experience. Thus, he explores ways to open up the city so that place matters more. Like other sources I have found, he also investigates how individuals and groups interact with each other and as well as other factors within the urban environment. He looks into how people make social and cultural sense of material facts. Much of his talk focuses on the human and their experience within the city. I find that this talk to be helpful as Sennett gave a lot of good insight on how we might be able to create an atmosphere that focuses on the experience rather than the private individual. I also find particularly helpful that in this talk, he cited many works both by him and other authors to help him argue his case. Much like Atiwill, having cited many works can help me as the researcher understand this topic of urban interiority at a much deeper scale.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 70 71

On the Nature of Public Interiority

Teston, Liz. “On the Nature of Public Interiority.” Interiority. 3 no. 5 (2020):61-82. 10.7454/ in.3i1.72.

[31] Liz Teston’s expertise all have to do with interiority and its relation to the urban realm, which is reflected in her works and teaching courses. Much of Liz Teston’s research lies within the topics of public interiority and the politics of design to name a few.

Teston[31], throughout this article, talked a lot about the psychological relationships of the human and the public interior. She defines ‘public interiority’ as interiority that can be found in external urban places. She explores the idea of public interiority and understands the relationship it has with the built environment and the human conditions. To do this, she first investigated the ontology of interiority. And then, she goes on to analyse a taxonomy of public interiorities. With all of this in mind, she uses real-world examples in cities that she has already researched on, thus having prior (and quality) knowledge of their urban interiority. She then concluded that having interiority within the public sphere is, in fact, possible, and even affects the human conditions in a positive way as it allows the inhabitants to have a personal relationship with the urban conditions.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 72 73

Image Sources

1. City of Melbourne. “Render of ariel view from the north.” Bourke Street Redevelopment. Accessed on 19 June 2021, https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/ building-and-development/shaping-the-city/city-projects/bourke-street-precinct/ pages/bourke-street-precinct-redevelopment.aspx.

2. Wikimedia Commons. Image of Giambattista Noli’s Map of Rome. Accessed on 24 May 2021, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Giovanni_Battista_ Nolli-Nuova_Pianta_di_Roma_(1748)_05-12.JPG.

3. McDowell, Lachlan. Photograph of Walter Benjamin’s Arcade Project. 2020. City of Melbourne. CoM Laneways Project.

4. Coombs, Gretchen. “Inside Out: When Objects Inhabit the Streets”. Idea Journal 15 no. 1 (2018):90-101. https://doi.org/10.37113/ideaj.vi0.55. Figure 1.

5. Coombs, Gretchen. “Inside Out: When Objects Inhabit the Streets”. Idea Journal 15 no. 1 (2018):90-101. https://doi.org/10.37113/ideaj.vi0.55. Figure 2.

6. Coombs, Gretchen. “Inside Out: When Objects Inhabit the Streets”. Idea Journal 15 no. 1 (2018):90-101. https://doi.org/10.37113/ideaj.vi0.55. Figure 3.

7. Coombs, Gretchen. “Inside Out: When Objects Inhabit the Streets”. Idea Journal 15 no. 1 (2018):90-101. https://doi.org/10.37113/ideaj.vi0.55. Figure 4.

8. ABC. “Melbourne as it looked in 1838, shaped by surveyor Robert Hoddle.” Melbourne Grid Designed by Robert Hoddle. Accessed on 11 June 2021, https:// www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/archived/bydesign/melbourne-griddesigned-by-robert-hoddle/5689062

9. City of Melbourne. “Image of Hoiser Lane.” Visit Melbourne. Accessed on 11 June 2021, https://www.visitmelbourne.com/regions/Melbourne/ Things-to-do/Art-theatre-and-culture/Public-art/VV-Hosier-Lane.

11. City of Melbourne. “New Open Space and Trees in Dodd Street.” Public Art in Southbank. Accessed on 11 June 2021, https://www. melbourne.vic.gov.au/arts-and-culture/art-outdoors/public-art-melbourne/ projects/pages/public-art-southbank.aspx.

12. City of Melbourne. “Southbank Promenade sketch.” Southbank Promenade. Accessed on 11 June 2021, https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/ building-and-development/shaping-the-city/city-projects/pages/southbankpromenade.aspx.

13. City of Melbourne. “New Park in Market Street sketch.” New Park in Market Street. Accessed on 11 June 2021, https://www.melbourne.vic.gov. au/building-and-development/shaping-the-city/city-projects/pages/newpark-market-street.aspx.

14. City of Melbourne. “Open Space in front of the ABC Southbank Centre.” Transforming Southbank Boulevard. Accessed on 11 June 2021, https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/building-and-development/shapingthe-city/city-projects/southbank-boulevard/pages/transforming-southbankboulevard-dodds-street.aspx.

15. Oring, Sheryl. “Image of a letter from I Wish t o Say.” I Wish to Say. Accessed on 18 June 2021, http://www.sheryloring.org/i-wish-to-say.

16. Starkman, Christine. “Lee Mengwei’s The Letter Writing Project.” Lee Mengwei in Measure Your Existence. Accessed 18 June 2021, https:// rubinmuseum.org/page/lee-mingwei-in-measure-your-existence.

17. Twersky, Carolyn. “Aman Mojadidi’s Once Upon a Place.” In a Phone Booth in Times Sqaure: Immigration Stories Come to Life in Aman Mojadidi’s ‘Once Upon a Place.’ Accessed 18 June 2021, https:// www.artnews.com/art-news/news/in-a-phone-booth-in-times-squareimmigration-stories-come-to-life-in-aman-mojadidis-once-upon-aplace-8626/.

10. City of Melbourne. “Image of Little Streets Project.” Little Streets. Accessed on 11 June 2021, https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/buildingand-development/shaping-the-city/city-projects/pages/little-streets.aspx.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 74 75

Bibliography

Atiwill, Suzie. “Interior Designing in the Urban Environment: Practices for the 21st Century.” in Handbook of Research on Methodologies for Design and Production Practices in Interior Architecture, edited by Evin Garip and S. Banu Garip, 392-400. Hershey, USA: IGI Global, 2021.

Atiwill, Suzie. “The Subjective City: Towards a Reconceptualization of Urban Interiority,” in The Interior Urbanism Reader, edited by Gregory Marinic. UK: Routledge, 2021.

Atiwill, Suzie. “Urban Interiors and Interiorities,” in Cultural, Theoretical, and Innovative Approaches to Contemporary Interior Design, edited by Luciano Crespi. 58-67. USA: IGI Global, 2020.

Atiwill, Suzie. “Urban Interior: Interior-Making in the Urban Environment.” IDA Congress Education Conference International Design Alliance, World Congress, Taiwan, 24-26 October 2011, 1-8.

Atiwill, Suzie. “Urban and Interior: Techniques for an Urban Interiorist,” in Urban Interior: Informal Explorations, Interventions and Occupations, edited by Rochus Hinkel. 11-24. Bamberg: Spurbuchverlag.

Attiwill, Suzie, Elena Enrica Giunta, Davide Fassi, Luciano Crespi, and Hermida Belén. “URBAN + INTERIOR”. Idea Journal 15 no. 1 (2015):2-11. https://doi. org/10.37113/ideaj.vi0.266.

Brennan, Martin. “Towards a Collaborative City: The Case for a Melbourne Metropolitan Commission.” The Conversation. 2016. Accessed on 14 April 2021, https://theconversation.com/towards-a-collaborative-city-the-case-for-amelbourne-metropolitan-commission-57578.

City of Melbourne. “20-Minute Neighbourhoods.” Plan Melbourne 2017-2050. Accessed on 14 April 2021, https://planmelbourne.vic.gov.au/currentprojects/20-minute-neighbourhoods.

City of Melbourne. “Bourke Street Redevelopment.” City of Melbourne. Accessed on 13 April 2021, https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/building-anddevelopment/shaping-the-city/city-projects/bourke-street-precinct/pages/ bourke-street-precinct-redevelopment.aspx.

City of Melbourne. Council Plan 2017-2021. 2019. https://www.melbourne.vic. gov.au/about-council/vision-goals/Pages/council-plan.aspx

City of Melbourne. COVID-19 Reactivation and Recovery Plan: City of the Future. 2020. https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/sitecollectiondocuments/ covid-19-reactivation-recovery-plan.pdf.

City of Melbourne. Future Melbourne 2026. 2016. https://www.melbourne.vic. gov.au/about-melbourne/future-melbourne/future-melbourne-2026-plan/Pages/ future-melbourne-2026-plan.aspx

City of Melbourne. “Little Streets.” City of Melbourne. Accessed on 13 April 2021, https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/building-and-development/shapingthe-city/city-projects/pages/little-streets.aspx

City of Melbourne. Plan Melbourne 2017-2050. Accessed on 13 April 2021. https://planmelbourne.vic.gov.au/the-plan.

City of Melbourne. “Public Art in Southbank.” City of Melbourne. Accessed on 13 April 2021, https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/arts-and-culture/artoutdoors/public-art-melbourne/projects/pages/public-art-southbank.aspx

City of Melbourne. “Soutbank Promenade.” City of Melbourne. Accessed on 13 April 2021, https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/building-and-development/ shaping-the-city/city-projects/pages/southbank-promenade.aspx

City of Melbourne. “Soutbank’s Urban Forest.” City of Melbourne. Accessed on 13 April 2021, https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/building-and-development/ shaping-the-city/city-projects/pages/southbank-urban-forest.aspx

Coombs, Gretchen. “Inside Out: When Objects Inhabit the Streets”. Idea Journal 15 no. 1 (2018):90-101. https://doi.org/10.37113/ideaj.vi0.55.

Cooper, Rachel, Elizabeth Burton, and Cary L. Cooper. Wellbeing and the Environment. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

Di Prete, Barbara, Davide Crippa, and Emilio Lonardo. 2018. “’E-urbanism’: Strategies to Develop a New Urban Interior Design”. Idea Journal 15 no. 1 (2018) :14-27. https://doi.org/10.37113/ideaj.vi0.46.

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 76 77

Hil, Greg, Lawrence, Susan, and Smith Diane. “Remade Ground: Modelling Historical Elevation Change Across Melbourne’s Hoddle Grid.” Australian Archaeology. 72 no.1 (2021): 21-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/03122417.2020.1

840079

Knight, Ben. “DIY Urbanism: When Citizens Take on City Planning. UNSW Newsroom. 2020. https://newsroom.unsw.edu.au/news/art-architecture-design/ diy-urbanism-when-citizens-take-city-planning.

Leveratto, Jacopo. “Urban Interiors: A Retroactive Investigation.” Journal of Interior Design. 44 no. 3 (2019): 161-171.

Mace, Valerie. “The Transfigured Phenomena of Domesticity in the Urban Interior.” Idea Journal. 15 no. 1 (2015): 56-77. https://doi.org/10.37113/ideaj. vi0.53.

Pimlott, Mark. “Interiority and the Conditions of Interior.” Interiority. 1no. 1 (2018):5-20. doi: https://doi.org/10.7454/in.v1i1.5

Poot, Tine, Maarten Van Acker, and Els De Vos. “The Public Interior: The Meeting Place for the Urban and the Interior”. Idea Journal 15 no. 1 (2015):4455. https://doi.org/10.37113/ideaj.vi0.52

Rogers, Dallas, Adrienne Keane, Tooran Alizadeh, and Jacqueline Nelson. Understanding Urbanism. Singapore Springer Singapore Pte. Limited, 2020.

Rosmarin, Tahj and Sidh Sintusingha. “Kebab Urbanism: Melbourne’s ‘Other’ Cafe Makes the City a More Human Place.” The Conversation. 2019. https:// theconversation.com/kebab-urbanism-melbournes-other-cafe-makes-the-citya-more-human-place-112228

Rudlin, David, Rob Thompson, and Sarah Jarvis. Urbanism. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Sennett, Richard. “GSD Talks: Richard Sennett, ‘The Open City’”. Harvard GSD. 24 October 2017. YouTube Video. 1:33:47. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=7PoRrVqJ-FQ

Teston, Liz. “On the Nature of Public Interiority.” Interiority. 3 no. 5 (2020):6182. 10.7454/in.3i1.72

Urban Interiority Stephanie Siy Cha 78 79

Stephanie

Siy Cha