Legendary magazine editor Diana Vreeland began her career at US Harper’s Bazaar in the 1930s, going on to achieve immortality in the fashion world. With the release of an intimate documentary on the style icon, film-maker – and Diana’s granddaughter-in-law – LISA IMMORDINO VREELAND describes her journey to uncover the lore surrounding the family’s enigmatic matriarch

www.harpersbazaar.co.uk

September 2012 |

H A R P E R’ S BA Z A A R

| 289

▼

PHOTOGRAPHS: HORST P HORST, 1979, © ESTATE OF HORST P HORST/ART & COMMERCE, COURTESY OF THE DIANA VREELAND ESTATE

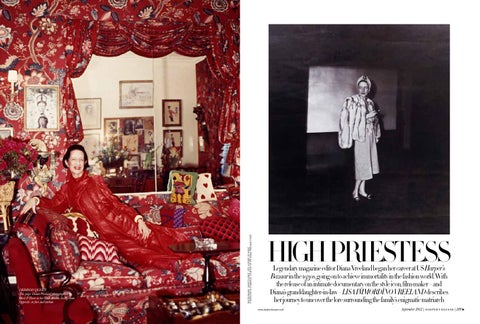

CRIMSON QUEEN This page: Diana Vreeland photographed by Horst P Horst in her Park Avenue living-room. Opposite: in furs and turban

HIGH PRIESTESS