aa r reena eenactors ctors m magazine agazine

u u

issue iss ue 11

u u

dec december ember 2014 2014

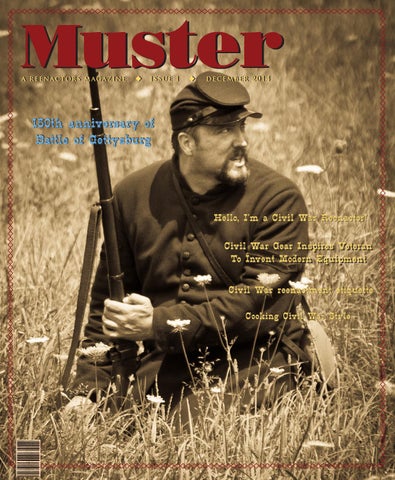

150th anniversary of Battle of Gettysburg

Hello, I’m a Civil War Reenactor! Civil Civil War War Gear Gear Inspires Inspires Veteran Veteran To To Invent Invent Modern Modern Equipment Equipment Civil War reenactment etiquette Cooking Cookin Civil War Style