TheOriginsoftheStakeholderConcept

Formanycontemporaryscholars,organizedthinkingaboutthestakeholderconcept beganwithFreeman'sseminalbook, StrategicManagement:AStakeholderApproach (1984).But,asFreemanhimselfacknowledges,thegeneralideaantedatedhisbookbyat leastseveralyears,perhapsbycenturies.Togainafullunderstandingofthehistoryofthe concept,onefirstneedstoexploretherelatednotionofcorporatesocialresponsibility andsomeofitsantecedentideasandthenreviewrelatedthemesfromtheliteraturesof corporateplanning,systemstheory,andorganizationtheory.

Corporatesocialresponsibility

Corporatesocialresponsibility,definedbyJonesas“thenotionthatcorporationshavean obligationtoconstituentgroupsinsocietyotherthanstockholdersandbeyondthat prescribedbylaworunioncontract”(1980,pp.59–60),clearlyhas“stakeholders”atits core.Theoriginsofcorporatesocialresponsibility alsoshowconcernforstakeholders, evenifthisspecifictermwasn'tused. Eberstadt(1973) arguesthatconceptsanalogousto socialresponsibilityhavebeenwithusforcenturies,evenmillennia.Forexample,in classicalGreece,businesswasexpectedtobeofservicetothelargercommunity.Inthe Medievalperiod,roughly1000–1500AD,agoodbusinessmanwashonest“inmotive andactions”andusedhisprofitsinasociallyresponsiblemanner(Eberstadt,1973).For centuries,theideaof“noblesse oblige” – roughlydefinedas“theresponsibilityofrulers totheruled” – representedananalogousconceptamongmembersoftheEuropean

aristocracy.Ifoneassignssimilarresponsibilitiestomembersofaneconomicaristocracy inAmerica,acountrywithoutahereditaryaristocracy,theanalogyisnotfarfetched.This conclusionisparticularlycompellingsincethepowerwieldedbycorporatemanagers (andowners,duringthe“robberbaron”era)mayinmanycasesrivalthatoftheir Europeanaristocracycounterparts.

Furthermore,althoughtheydidn'tusethetermcorporatesocialresponsibility,Berleand Means,intheirclassicworkontheseparationofownershipandcontrol, TheModern CorporationandPrivateProperty,invokedthegeneralconcept.Theydid notbemoan thisseparationofownershipandcontrolasmanyeconomistsdid,butrathernotedthatit liberatedmanagerstoservethelargerinterestsofsociety.Intheirwords:

Thecontrolgroupshave,rather,clearedthewayfortheclaimsofagroupfar widerthan eithertheownersorthecontrol.Theyhaveplacedthecommunityinapositiontodemand thatthemoderncorporationservenotalonetheownersorthecontrolbutallsociety (1932,p.312).

ThisconclusionmusthaveseemedsomewhatoddtofollowersofadebatebetweenBerle andE.MerrickDoddinthepagesofthe HarvardLawReview (1932) andthe University ofChicagoLawReview (1935) from1931to1935.AlthoughDoddpersuasively advocatedabroadersetofcorporateresponsibilities,Berledidn'tconcedethepointuntil 1954in TheTwentiethCenturyCapitalistRevolution.

BerleandMeanswerenotaloneamongscholarswhoadvocatedbroaderresponsibilities forbusinessexecutivesinthe1930s.ThenotedauthorChesterI.Barnardstressedthe fundamentallyinstrumentalroleofthecorporationin TheFunctionsoftheExecutive (1938).Thepurposeofthefirm,heargued,wastoservesociety;corporationswere meanstolargerends,ratherthanendsinthemselves.

Manybusinesspeoplealsotookstepstopubliclyembracetheideaofsocialresponsibility. Inapost-depression(andpost-WWII)fitofdefensivenessaboutthevirtuesofcapitalism andapropagandablitzintendedto“sell”capitalismtotheAmericanpublic,theybegan toadoptposturesofbroadresponsibilitytocorporateconstituents(Cheit,1956).Included inthesepronouncements,commoninthe1950s,weredepictionsofexecutivesas corporate“statesmen”whobalancethemanifoldinterestsofsocietyintheirdecisions.In somesense,corporatesocialresponsibility,asanidealatleast,wasimposedonbusiness bybusinessitself.Itwasn'tuntiloutsidersbegantoquestiontheresultsofthis statesmanshipthatcorporatesocialresponsibilitybegantoacquirealargerexternalgroup ofadvocates.ItwasalsoduringthisperiodthatHowardBowenpublishedhispathbreakingbook, SocialResponsibilitiesoftheBusinessman (1953).Bowenwroteofthe gatheringintellectualforceofthedoctrinethatbusinessleadersare“servantsofsociety” andthat“managementmerelyintheinterests(narrowlydefined)ofstockholdersisnot thesoleendoftheirduties”(1953,p.44).

Eachofthehistoricalandintellectualpredecessorsdiscussedthusfarfocusonwhat DonaldsonandPreston(1995) callthenormativeaspectsofstakeholdertheory.Although

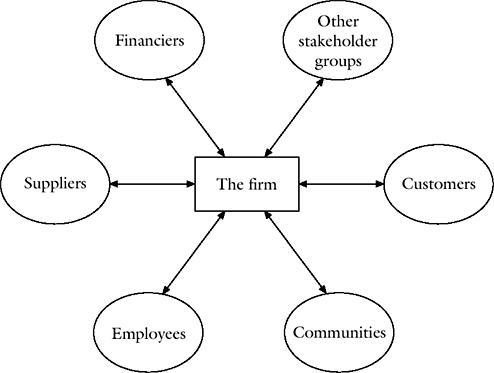

nooneusedtheterm“stakeholder”atthetime,theseperspectivesheldthatcorporations should behaveinwaysthatwerequitedifferentthanthoseprescribedbytheconventional goalofthefirm.Accordingtothisalternativeperspective,firmsshouldbeoperatedin ordertoservetheinterestsofcustomers,employees,lenders,suppliers,andneighboring communitiesaswellasstockholders.

Corporateplanning

Anothersetofantecedentideasapproachedthestakeholderquestionfromaquite differentangle,however.As FreemanandReed(1983) and Freeman(1984) carefully document,astrainofstakeholderthinkingwasalsodevelopinginthecorporateplanning literatureandrelatedwork.Theterm“stakeholder”wasfirstusedattheStanford ResearchInstitutein1963andwasemployedtoconnotegroups“withoutwhosesupport theorganizationwouldceasetoexist”(Freeman,1984).1 ToSRIresearchers,corporate planningcouldnotproceedeffectivelywithoutsomeunderstandingoftheinterestsof stakeholdergroups.Inthisviewandinmanyviewsderivedfromit,attentionto stakeholderconcernswasclearlysubsidiarytosomeother,dominantinterest –stockholderreturnsorfirmsurvival,forexample.Ansoff's CorporateStrategy (1965) dealtwiththestakeholdernotionbyarguingfortheexistenceoftwotypesofcorporate objectives – economicandsocial – withsocialobjectivesbeingsecondarytoeconomic objectives.Althoughthesesecondaryobjectivesmightconstrainormodifythepursuitof theprimary(economic)objectives,theywereinnowaytoberegardedas “responsibilities.”

Inthecontemporaryvocabularyof DonaldsonandPreston(1995),managersshouldbe concernedaboutstakeholdersonlyfor instrumental reasons – asameanstoimprovethe financialperformanceofthefirm.Oneoftheextensionsofthis instrumentaluseof stakeholderthinkingwasenvironmentalscanning,aprocessbywhichplannersattempted toforecastchangesinthesocialenvironmentsoffirms.Withbetterassessmentsofthese environments,bettereconomicforecastsand,ultimately,bettercorporatestrategicplans couldbemade.

Systemstheory

Freeman(1984) alsopointstothesystemstheoryliteraturein hishistoricalaccountofthe developmentofthestakeholderconcept.Theworksof Churchman(1968) and Ackoff (1970) figureprominentlyinthishistory.Accordingtothesystemsview,manysocial phenomenacannotbefullyunderstoodinisolation.Rather,theymustbeviewedasparts oflargersystemswithinwhichtheyinteractwithotherelementsofthesystem.Inthis context,theconceptof“stakeholdersinasystem”hasmeaningquitedifferentfromthat employedbyauthorsinthestrategyliterature(Freeman,1984).Accordingto Ackoff (1974),stakeholdersmustplayaparticipatoryroleinthesolutionofsystemicproblems. Inthisframework,theoptimizationofthegoalsofindividualcomponentsofthesystem (sub-systemgoals)istobepursuedonlytoanextentcompatiblewiththepursuitof overallsystemgoals.Theintrinsicvalueofsubsysteminterestsisclearlysubordinateto overallsysteminterests.

Organizationtheory

Accordingto Freeman(1984),organizationtheoristswerealsoimportantfore-runnersof theformaldevelopmentofthestakeholderconcept.Inparticular,heconsiders Rhenman (1968),whooffersaformulationofstakeholder-basedideasverysimilartothatofthe corporateplanners.Aleadingedgethinkerofhisera.Rhenman2 designates“the individualsandgroupswhichdependonthecompanyfortherealizationoftheirpersonal [and,presumably,group]goalsandonwhomthecompanyisdependant”asstakeholders (Freeman,1984,p.41).Other“pre-stakeholder”ideasfromorganizationtheoristsinclude thenotionof“organization-sets”(Evan,1966),an“open-systems”approach(Katzand Kahn,1966; YuchtmanandSeashore,1967),organizational“clientele”(Thompson, 1967),aswellascontributionsby EmeryandTrist(1965) and Dill(1958),amongothers. Theworkof PfefferandSalancik(1978) isprobablytheorganizationtheorymost directlyanalogoustoastakeholderapproach.Theirconceptof“resourcedependence” capturestherelianceoforganizationsonprovidersofkeyresourcesandsupportina formalway.Therelianceofothergroupson“resources”fromthefirmisnotemphasized inresourcedependencetheory,althoughmanyoftherelationshipsinquestionareclearly reciprocalinnature.

However,someorganizationtheorists(PenningsandGoodman,1977)wereconcerned withthefullrangeof“outputs”oforganizations,ratherthanjustefficiencyor,inthecase ofcorporations,profit.Thesescholarsoftenstressedthedifferencebetweenefficiency andeffectiveness,thelatterbeingdefinedintermsoftheappropriatenessofan organization'soutput. Nord(1983) madeexplicitthenormativenatureofany measurementoforganizationaloutput.Intheprocess,he(perhapsinadvertently)linked theorganizationaleffectivenessliteraturetotheexplicitlynormativeliteratureof corporateresponsibility.Amoredetailed accountofdevelopmentsinorganizational effectivenesscanbefoundinEhreth,whoarguesthat“organizationaleffectivenessisnot anobjectivestatebutisarelationalconstructthatfitstheneedsandinterestsof constituencies”(1987,p.9).

Althoughthisbriefsummarycannotdojusticetotheintellectualantecedentsof stakeholdertheory,itdoessuggestthatthosewhohavedoneacademicworkon stakeholdertheoryhavenotdonesowithoutguidancefromscholarsinrelatedfields. Thosecontributionsareherebygratefully,ifnotfully,acknowledged.And,itisnoted thatsomeoftheongoingargumentswithinthestakeholdertheoryliterature – manyof whichcuttothecoreofitspurposeanddesign - areindebtedtoitsmultidisciplinary origin.Each disciplinebringsaslightlydifferentsetofassumptions,implicitnorms,and methodstothedevelopmentofstakeholdertheory.

TheCurrentStateoftheArtofStakeholderTheory

Thepast15yearshaveseenthedevelopmentoftheideaofstakeholdersintoan“ideain goodcurrency.”Talkofstakeholdersisincreasinglycommonwithinbusinessand academiccircles.Therearescoresofessaysfocusingonstakeholderswithinmanagement asethicsandsocialissuesbecomemoresalient,andasourattentionexpandsbeyondthe

strictfocusonshareholders.Evenrestrictingourattentiontoacademicwritingsstill leavesamyriadofdifferentwork(spanningempiricalandnormativeresearch),theexact relationshipsamongwhichareoftendifficulttoidentify.Thequestionis,whatkindof sharedunderlyingthemesandideasmakeupstakeholdertheory?Thatis,ifweexamine thecurrentstateoftheartwithinthisfield,whatsortoftheorydowefind?

DonaldsonandPreston(1995) providedoneinfluentialmethodforsynthesizingthearray ofworkthathadbeendonetodate.Theyadvancedfourkeyideasthattheyclaimedwere centraltostakeholdertheorywhichmakeitadistinctivetheoryratherthanasetof disparateideasabout“stakeholders.”Accordingto DonaldsonandPreston(1995), stakeholdertheoryis descriptive,instrumental,normative and managerial.Itis descriptive inthesensethatresearchersadvancingstakeholdertheoryattempttotalk about,ordescribe,whatthecorporationis(i.e.howpeople atthecorporationbehave). Theythencomparethattosomelargerschematictoevaluatetheirperformance(e.g.do theyactasthoughthestakeholderorshareholdermodelisdrivingtheirbehavior?).

Stakeholdertheoryis instrumental inthatresearchers advance“if…then”typesof propositions,specifically,thatactingaccordingtostakeholdermanagementprinciples willbeassociatedwithpositiveoutcomesforthecorporation. DonaldsonandPreston (1995) thenclaimthatthecentralstrandofstakeholdertheory,andthe“glue”which holdsthetheorytogether,isits normative content – claimsthatfocusonwhatmanagers ought todo.Stakeholdermanagementprinciplessetoutthelegitimateinterestsofvarious stakeholders(includingbutgoingbeyondshareholders)inthecorporationandusethese asabasisfordetermininghowmanagersshouldbehave.Indeed,itisthisdistinctive normativecorewhichhelpsgiveshapeandsubstancetothefirsttwostrands.This normativestrandprovidesadescriptivestoryorscript(i.e.respectthelegitimateinterests ofstakeholders)onecouldusetocomparetorealmanagerialbehaviortoseeiftheyare similarordifferent.Thesenormativecommitmentsprovideasetofbehaviorsonemight testtoseetheperformanceimplications(i.e.the“if…then”statementscharacteristicof instrumentaltheory).Finally, DonaldsonandPreston(1995) claimthatstakeholder theoryis managerial,inthatitaimstoshapeanddirectthebehaviorsofmanagersatthe corporatein aspecificandsystematicway.

Thecoreappealofthe DonaldsonandPreston(1995) articleisthatitprovidedorderand coherencewheremanysawchaosandconfusion.Stakeholderresearchersinbusiness ethics,businessandsociety,strategy,humanresources,andotherdisciplinesintuitively sensedthattherewasaconnectiontothewritingsoftheirpeers,buttherewerefew theoreticallydevelopedideaslinkingtheirworktogetherbeyondtherecognitionthat groupsbeyondshareholdershadlegitimacyatthecorporation.Thoughitdidn'tresolvea numberofkeyloomingproblems,3 the DonaldsonandPreston(1995) typologyappeared toprovidepartofthismissinglink.Itofferedanumbrellatocoverexistingresearchin stakeholdertheory,organizeitintodistinctstrands(i.e.descriptive,instrumental, normative),anddirectfuturework(i.e.tomakesureitiscoherentandfollowsthe typologysetoutintheirarticle).Italsohelpedtocombattheperceptionthatstakeholder theorywasanamorphousandill-definedconstruct,bornofgoodintentions,butdoomed tofailforitsbreadth,itsemphasisonpeopleratherthanprofits,anditsinabilitytodirect theday-to-daybehaviorofmanagers.

However,thereemergedvoicesofdissenttothisgrandreconciliation. Freeman(1994, 1999,2000) tookdirectaimatthe DonaldsonandPreston(1995) typologyfortwomain reasons.First,Freemansawtheirworkasreinforcing,ratherthanovercoming,the separationthesis.Second,hethoughtthesharpconceptualseparationamongnormative, descriptiveandinstrumentalwasuntenable.

Intermsofthefirstcriticism,Freemanhaslongbeenconcernedwiththeimportanceof languageandmetaphorandhowthisshapesexistingpractice.Theseparationthesisposits thatpeople,forthemostpart,tendtoseethelanguageandconceptsofethicsand businessasseparateandthattheyoccupy distinctrealms(e.g.ethicsdealswithaltruism andconcernforothers;businessdealswithselfishnessandprofits).Thedifficultyis tryingtofindawaytogetthesetworealmsbacktogether,oratleasttooverlapenough sothatyoucanconvincemanagersthatbeinggoodattheirjobdoesn'tmeantheyhaveto bea-,orim-moral.Freemanpointsoutthattheproblemwiththetworealmsisnotthat somepeoplearehappytokeepthemseparatewhileotherswanttobringthemcloser together,butthatthis metaphorforthinkingaboutbusinessandethicsisfundamentally misguided.Businessethicsshouldinsteadbeabouthowweunderstandthenatureof business,asamorallycompellingandinterestingdomainofhumanactivitythatcould neverbedevoidofmorality(i.e.sothedivideneveroccursinawholesaleorsystematic way).ForFreeman,the DonaldsonandPreston(1995) articlemakesthemistakeof settingupstakeholdertheoryasthefoiltoshareholdertheory,therebyreinforcingthe ideathatethics(i.e.stakeholdertheory)isfundamentallydifferentfrombusiness(i.e. shareholdertheory)andmanagershavetochoosebetweenthem.Forthisreason, Freeman(1994,1999,2000) didn'twanttomakestakeholderaspecificandsingular theorythatcouldbecomparedtoshareholdertheory.Rather,hesoughttomake stakeholdertheoryagenreofresearchinwhichanyaccountofthefirmthatpositsa purposeforthefirmandasetofresponsibilitiesofmanagersisa“stakeholdertheory.” Underthisview, theshareholdertheoryisitselfa“stakeholdertheory.”Thepurposeof thismoveistounderscorethenormativeunderpinningsofanytheoryofthefirmandto helpmakeusallbettercriticsofcorporationsbyforcingustoevaluatewhetheragiven corporationhasacompellinganswertoquestionsregardingthepurposeofthefirmand theobligationsofmanagerstostakeholders.

Freemanalsoobjectedto DonaldsonandPreston's(1995) workbecauseheclaimedit sharplydividedconceptualcategoriesthatarenotfundamentallydifferent.Following Quine,Davidson,Rorty,andothermodernpragmatists,Freemanarguedthatasharp separationofthesemodesofinquiryisneitherconceptuallyplausiblenorpragmatically desirable.Indeed,sharplyseparatingfactsandvalues,normativeandempiricalinquiry, risksreinforcingtheseparationthesisalloveragain(WicksandFreeman,1998). Freemanclaimsthatthesemodesofinquiryareinterrelatedandtogethermakeupa coherentanswertothestakeholderquestion:whatisthepurposeofthecorporationandin whoseinterestsshoulditberun?Anyadequateanswertothatquestion,heclaims,isa normativecoreornarrative.Itwillhaveaspectsofwhat DonaldsonandPreston(1995) calldescriptive,instrumentalandnormativediscourseandallplayakeyroleinproviding acompellingtheoryornarrative.Nooneelementcanbesharplyseparatedandnoone stranddoestheprimary“work”ofcreatingacompellingandjustifiedtheory.

Althoughstakeholdertheoryhasmadesubstantialadvancesoverthepastdecade,much workremainstobedone.Tobeginwith,thevastmajorityofstakeholder-basedresearch papersthathavebeenpublishedtodateareeithertheoreticalorconceptualinnature. Giventhattheorybuildinginastakeholderframeworkcantakeonseveralforms,threeof which – normative,instrumental,anddescriptive – weredescribedby Donaldsonand Preston(1995),itisnosurprisethattheoreticalperspectivesdominatetheliterature.

Thisdominancenotwithstanding,moretheoreticalworkisneeded.Forexample, narrativeinterpretation,advocatedby Freeman(1994),anddescribedbyJonesandWicks as“…thecreationofnarrativeaccountsofmoralbehaviorinastakeholdercontext” (1999,p.209),hasnotbeenexhaustedasagenreofresearch.Inparticular,weareaware ofnonarrativestakeholdertheoriesbasedontheoriesofdistributivejustice.Although unconventionaleveninthealreadyunconventionalworldofnarrativestakeholder theories,suchdistributivejustice-basedaccounts – forexample,a Rawlsian“difference principle”basedtheoryoran“entitlements”basedtheoryderivedfromtheworkof Nozick(1975) arenotbeyondimagination.Anaccountbasedon“effortocracy”could alsobeformulatedinanarrativeformat.

AccordingtoDonaldsonandPreston,instrumentalstakeholdertheory“isusedtoidentify theconnections,orlackofconnections,betweenstakeholdermanagementandthe achievementoftraditionalcorporateobjectives(e.g.,profitability,growth)(1995,p.71). Todate,onlyoneformallypresentedinstrumentalstakeholdertheoryhasbeenadvanced. Jones(1995) arguesthatfirmswhosemanagersareabletocreateandsustainmutually trustingandcooperativerelationshipswiththeirstakeholderswillachievecompetitive advantageoverfirmswhosemanagerscannot.Otherinstrumentalstakeholdertheories arecertainlypossibleandtheinstrumentalrealmmightconstituteafertilegroundfornew stakeholdertheorydevelopment.

Accordingto JonesandWicks(1999),therealchallengetostakeholdertheoristsisthe creationof“convergent”stakeholdertheory.Convergentstakeholdertheoryistheorythat is simultaneouslymorallysoundinitsbehavioralprescriptionsandinstrumentallyviable initseconomicoutcomes.Accordingtotheseauthors,narrativeaccounts(or,forthat matter,anynormativestakeholdertheory)withoutsomeevidence(broadlydefined) asto theirpracticability,areoflittlevalue.Similarly,instrumentalstakeholdertheorythatcalls foradherencetobehavioralstandardsthatarenotmorallysoundshouldalsohavelittle appealtoscholarswithastakeholderorientation.Recallthatthemostbasicnormative tenetofstakeholdertheoryistheviewthattheclaimsofalllegitimatestakeholdershave intrinsicvalue.Itfollowsthatstakeholdertheorywithseriousmoraldeficienciesshould notbeacceptabletostakeholdertheoryadvocates.Although JonesandWicks(1999) do notfullydevelop Jones's(1995) “mutualtrustandcooperation”instrumentaltheoryintoa formalconvergenttheory,theydosuggestthegeneraloutlinesofanextensionofthat type.Extendingtheideaofpossibledevelopmentofadditionalnormativetheories presentedabove,convergenttheorybasedonthesenormativepremises – thedifference principle,entitlements,andeffortocracy – isalsopossible.Finally, Donaldsonand Dunfee's(1994) IntegrativeSocialContractsTheory(ISCT)wouldseemtobeagood candidatefordevelopmentintoaconvergentstakeholdertheory.

Theworldofbusinesspracticealsoprovidessomepotentiallyrichsourcesfordoing stakeholdertheoryresearch.Workslike CollinsandPorras'BuilttoLast(1994) and Paine's“ManagingforOrganizationalIntegrity”(1994) bothfocusoncompaniesthat providethe morecomplexandmorallyinterestingapproachestorunningafirmthatare attheheartofstakeholdertheory.Indeed,muchofwhatdrivestheworkoftheauthorsof theseworksisasenseofthelimitationsandshallownessofdescribingthecorporationas solelyaboutmakingprofitsandenrichingshareholders.Onecoulddescribethe “corporateideology”ofthefirmsprofiledby CollinsandPorras(1994) andthe“integrity strategy”ofthefirmsdescribedbyPaine,as(atleastpartial)normativecores.These works,andotherslikeitfromthepractitionerrealm,holdspecialpromisetoaddressthe managerialandpracticalchallengesofstakeholdertheory.Thatis,suchworkdrawsclear connectionbetweenvaluesandpurposeontheonehandandmanagerialactivityonthe other(i.e.itismanagerial),andtheseresourcesprovidecredibleconceptualand anecdotalevidenceastohow agivenfirm'snormativecoremayenableittobehighly competitivewithinthemarketplace(i.e.itispractical/workable).

Anotheravenueoftheoreticaldevelopmentinstakeholdertheoryinvolvesdescriptive theory – theorythatpurportstoexplainand(perhaps)predicthowmanagerswillactually behaveinthecontextofstakeholderrelations.Itmustbeacknowledgedthatneoclassical microeconomictheory,basedontheassumptionofrationalself-interestedbehavioron thepartofeconomicactors,representsalegitimateandhighlydevelopedversionofthis typeoftheory.Thefactthatmanystakeholdertheoryadvocatesdisputethemoral foundationsofboththeprocessesandoutcomesofthetheorynotwithstanding, neoclassicaltheoryisauthenticdescriptivestakeholdertheory.Although Jonesand Wicks(1999) expressdoubtthatatheorywiththebreadthanddepthofneoclassical economictheorywillemergefromthestakeholdertheoryframework,severalother approachesarepossible.Paperscurrentlyworkingtheirwaythroughthereviewprocess atvariousjournalsshowconsiderablepromise.Forexample,onemanuscriptmerges prospecttheory,resourcedependencetheory,andorganizationallifecycletheoryinan attempttoexplainwhichstakeholdergroupswillbeattendedtoatvariouspointsina firm'sdevelopment.Anotherpaper,anempiricaleffort,examinestherelativepreference (ofstudentgroups)for“across-decision”attentiontostakeholderinterestsasopposedto “within-decision”methods.Within-decisionmethodsattempttostrikeabalanceamong theinterestsofstakeholdergroupswithinindividualdecisions;across-decisionmethods merelyattempttobalancethoseinterestsovertime,inessence,relyingonanimplicitset ofIOUstoproducelong-termequityamongstakeholdergroups.Adescriptive stakeholdertheorybasedon DonaldsonandDunfee's(1994) IntegrativeSocialContracts Theoryisconceivableaswell.

Theemphasistodateontheoreticalworkshouldnotunderstatetheimportanceof empiricaleffortsintheinterestofadvancingstakeholdertheory.Asnotedby Jonesand Wicks(1999),instrumentaltheoryisempiricaltheory.Itmattersagreatdealwhetheror nottheestablishmentandmaintenanceofmutuallytrustingandcooperativerelationships do,infact,leadtocompetitiveadvantageaspredictedby Jones(1995).Inaddition, empiricalevidenceisonemeansofaddressingthe“practicability”facetofconvergent stakeholdertheory(JonesandWicks,1999).Economicallydisastrousoutcomesresulting

ofthefirm.Forinstance,inmostbusinesses,customers,suppliers,communities, financiers,andemployeesallhaveaclearstakeinthefirm.

Recently, Phillips(2001) hassuggestedthatsuchstakeholdersbecalled“intrinsic”or “definitional”whileothergroupsarestakeholdersinstrumentally, insofarastheyaffect thedefinitionalstakeholders.Hearguesthatfirmshavecommonmoralobligationsto bothdefinitionalandinstrumentalstakeholders,buthavespecialobligationsonlyto definitionalstakeholders.Thus,theinterestingquestion, onthisanalysis,becomeswhat doesthefirmowetoacustomer,(andthereciprocalquestionofwhatacustomerowesto afirmbyvirtueofbeingacustomer).

Alternatively,ifthenarrowdefinitiondefineswhohasastake,thenitisincumbentto givean accountofwhoandwhatcountsasa“community.”Inarecentpaper, Dunhamet al.(2001) havesuggestedthatif“community”isinterpretedwidelyenough,thenthe narrowdefinitionofstakeholdersexpandsintothewidedefinition,oncecommunityis understoodtoconsistofacollectionofthoseintereststhatsharesomecommons,ora politicalentitydefinedbycompetinginterestgroups.

Thisargumentraisesthenextchallenge;namely,itisimperativetopaymoreattentionto thebackgroundtheoriesthatareatwork.Theupshotofthesedifferingviewsof definitionisthatitisdifficulttosaywhatkindsofmoralobligations areatwork,when theverynatureofwhohastheobligationisobscure.Morepractically,ifwhoisa stakeholderisimprecise,itisdifficulttoformulatepriorityrulesaboutwhoseinterests countandwhentheycomeintoplay.However,sincedefinitions areembeddedinthe backgroundnormativetheoryshapingsuchinquiry,perhapsananalysisofthe backgroundtheoryproblemwillprovidesomeusefulresourcesforaddressingthese issuesaswell.

Thebackgroundtheoryproblem

Givenitsmultidisciplinaryorigins,muchofthedisagreementaboutstakeholdertheoryis diagnosableasdifferingsetsofbackgroundtheoriesatwork.Forinstance,inthestrategy literaturetherehastraditionallybeenlittleconcernwithethicsandvalues,sothemore subtleproblemsofdefinitionaredifficulttoappreciate.(Onesolutiontothisproblemis todefinestrategytheoristsoutofthestakeholdertheoryrealmandnotetheirmuchcloser affinitytoresourcedependencetheory.) Mitchelletal.(1997) havesuggestedatypology offeaturesthatdeterminewhichstakeholdersaremostimportantfromthreedifferent pointsofview.However,thisvery typologyassumesthatmanagersarethebestjudgesof stakeholderinterestsand/orbehavior,andimplicitlyassumesthatmanagers'orfirms' judgmentsaretheonesthatshouldbeusedtodeterminestakeholdersalience.

Therearesomescholarswhohavesuggestedthatstakeholderanalysisofthecorporation mustproceedfromwithinaframeworkthatacknowledgesthatthecorporationisalegal entity – alegalfiction.Thus,corporatelawanditsitinerantcompatriots,thelawoftorts, contracts,andagency, mustserveacentralroleinanystakeholdertheorythatistohave practicalsignificance.Atthispoint,thosewhoadvocatethispositionhavetheburdenof

Supposethattherecanbemultiplestakeholdertheories,each basedonanormativecore andasetofbackgrounddisciplines.Eachtheorywoulddescribehowfirmsmight actuallyrealizethatnormativecore,andthepropositionsthatconnectthenormativecore tootherfacetsoftheenterprise.Inadditioneachparticularstakeholdertheorymighthave asetofinstrumentalpropositions,suchas“ifyouwanttocreateshareholdervalue,you shouldmanagethefirminasustain-ablemanner”or“ifyouwanttomanagethefirmina sustainablemanner,youmustpayagreatdealofattentiontoenvironmentalists-criticsof thecorporation.”Theverylanguageusedtoframethesepropositionsmightdiffer dependingontheframingassumptionsthatmakeuptheparticulartheory.Eachparticular theorymightwellproduceadifferentsetoftradeoffsorprioritiesamongstakeholder groups.

Inthisthicketofpluralism,whatwouldbetheroleofanoverarching“stakeholder theory”?Perhapsitwouldsimplybe,aswearguedabove,theroleofgenre:pointingout whatasetofrelatedtheorieshaveincommon,andthencomingtoseethemasrelated alongparticulardimensions.

Supposehowever,thatweassumethataparticularstakeholdertheoryinitswell-worked outform,mightgiveanexecutiveorastakeholderareasonforactinginacertainmanner. Surely,thereisroomforconflictamongfullyspecifiedstakeholdertheories.Indeed,any stakeholdertheorybasedonnormativetheoryfrommoralphilosophywillalmost certainlybeinconflictwithothersuchtheories,giventhattheconflictsamongnormative theoriesarewelldocumented.Theexistenceofsuch“areasonablepluralism”maywell inducethesearchfora“minimalist”stakeholdertheory,orasetofbasicconditionsthat allnormativecoresmustmeettobelegitimate.Thiswould bothconstrainanddirectthe creative,pluralisticdrivetofindanarray,perhapsawidearray,ofnormativecoreswithin stakeholdertheory(Freeman,1994,1999,2000; WicksandFreeman,1998).Akintothe public-privatedistinctiononwhichpoliticalphilosopherssuchas Rawls(1993) have relied,wecouldevaluateactionsacross(andperhapsindependentof)variousstakeholder genresaccordingtosuchcriteria.Somecandidatesforsuchaminimalistorpublicsetof reasonswouldincludethoseprinciplesarticulatedby Freeman(2000) asgivingriseto stakeholdercapitalism,orthesuggestionsby JonesandWicks(1999) forconvergent stakeholdertheory.

Theproblemofvaluecreationandtrade,andethicaltheory

Traditionally,theoriesofbusinesshavebegunandendedwitheconomiclogic.Business hasbeenseen,wronglyaswearguedabove,asawayofcreating“economic”value,with ethicsperhapsservingasasideconstraint.And,businessethicsingeneral,and stakeholdertheoryinparticular,havebeendevelopedwithinaframeworkofexisting ethicaltheorythatassumesthatbusinessisprimarilyconcernedwith itseconomic (narrowlydefined)logic.Notsurprisingly,ethicaltheoryhaslittletosayaboutbusiness, orthewaythatvalueiscreatedandtraded.Yet,humanbeingshavebeenvalue-creators andtraderslongbeforetheywerepoliticalphilosophers.The practiceofbusinesshasa longhistory,yettheexistingbodyofethicaltheoryonwhichmostbusinessethicistsand stakeholdertheoristsrelypaysalmostnoattentiontotheculturalandmoralnormsof

2 ForahistoryofthedevelopmentofthestakeholderconceptinScandinavia,and Rhenman'sroleinthatdevelopment,see Nasi(1995).

3 Theirtypologyclaimsthatgroupsotherthanshareholdershavelegitimateinterests,but itdoesn'tspecifywhothesegroupsare,howwedeterminewhattheirlegitimateinterests are,orhowweresolveconflictsamongstakeholderinterests.Italsodidn't providea specificanswertothedefinitionalproblemthatthreatenedtomakestakeholdertheory vacuous:whoisastakeholderandwhydoesthefirmhaveaspecialobligationtothem? Finally,thoughitclaimstobemanagerial,itisnotimmediatelyclear howthecentral claimsofthisarticlewouldtranslateintoanymanageriallyspecificbehaviors.

References

Ackoff,R.1970: AConceptofCorporatePlanning .NewYork:JohnWiley. Ackoff,R.1974: RedesigningtheFuture .NewYork:JohnWiley. Ansoff, I.1965: CorporatePlanning .NewYork:McGrawHill. Barnard,C.I.1938: TheFunctionoftheExecutive .Cambridge:HarvardUniversity Press.

Berle,A.1954: TheTwentiethCenturyCapitalistRevolution .NewYork:HarcourtBrace.

Berle,A.andMeans,G.1932: PrivatePropertyandtheModernCorporation .New York:CommerceClearingHouse. Bowen,H.1953: SocialResponsibilitiesoftheBusinessman .NewYork:Harper. Cheit,E.1956: TheBusinessEstablishment .NewYork:JohnWiley. Churchman,W.1968: TheSystemsApproach .NewYork:DellBooks. Collins,J.andPorras,J.1994: BuilttoLast .NewYork:Harper. Dill,W.1958: Environmentasaninfluenceonmanagerialautonomy . Administrative ScienceQuarterly ,(2)(4),40943.

Dodd,E.M.,Jr.1932: Forwhomarecorporatemanagerstrustees HarvardLawReview , (45),1145.

Dodd,E.M.,Jr.1935: Istheeffectiveenforcementofthefiduciarydutiesofcorporate managerspracticable UniversityofChicagoLawReview ,(2),194. Donaldson,T.andDunfee,T.1994: Integrativesocialcontracts:Acommunitarian conceptionofeconomicethics . EconomicsandPhilosophy ,(11)(1),85112. Donaldson,T.andPreston,L.1995: Thestakeholdertheoryofthecorporation:concepts, evidence,andimplications AcademyofManagementReview ,(20)(1),6591. Dunham,L.,Liedtka,J.andFreeman,E.2001: Community:Thesoftunderbellyof stakeholdertheory .DardenSchoolWorkingPapers.Charlottesville,Va. Eberstadt,N.1973: Whathistorytellsusaboutcorporate responsibility . Businessand SocietyReview ,(7),7681.

Ehreth,J.1987: Developmentofacompetitiveconstituencymodeloforganizational effectivenessanditsapplicationtoaHealthServicesOrganization .Doctoral Dissertation.UniversityofWashingtonGraduateBusinessSchool. Emery,F.andTrist,E.1965: Thecausaltextureoforganizationalenvironments . Human Relations ,(18),2131.

Evan,W.1966: Theorganizationset:Towardatheoryofinter-organizationaldesign .In J.Thompson,(ed.) ApproachestoOrganizationalDesign .Pittsburgh:Universityof PittsburghPress,17590.

Freeman,E.1984: StrategicManagement:AStakeholderApproach .Boston:Pitman. Freeman,E.1994: Thepoliticsofstakeholdertheory:Somefuturedirections . Business EthicsQuarterly ,(4)(4),40922.

Freeman,E.1999: Divergentstakeholdertheory . AcademyofManagementReview ,(24) (2),2336.

Freeman,E.2000: Businessethicsatthemillennium . BusinessEthicsQuarterly ,(10)(1), 16980.

Freeman,E.andReed,D.1983: Stockholdersandstakeholders:Anewperspectiveon corporategovernance . CaliforniaManagementReview ,(25)(3),88106.

Jones,T.1980: Corporatesocialresponsibilityrevisited,redefined California ManagementReview ,(22)(3),5967.

Jones,T.1995: Instrumentalstakeholdertheory:Asynthesisofethicsandeconomics AcademyofManagementReview ,(20),92117.

Jones,T.andWicks,A.1999: Convergentstakeholdertheory . AcademyofManagement Review ,(24),20621.

Katz,D.andKahn,R.1966: TheSocialPsychologyofOrganizations .NewYork:John Wiley.

Kochan,T.andRubenstein,S.2000: Towardsastakeholdertheoryofthefirm:The SaturnPartnership OrganizationalScience ,(11)(4),36786.

Mitchell,R.,Agle,B.andWood,D. 1997: Towardatheoryofstakeholderidentification andsalience:Definingtheprincipleofwhoandwhatreallycounts . Academyof ManagementReview ,(22),85386.

Nasi,J.1995: AScandinavianapproachtostakeholderthinking:Ananalysisofits theoreticalandpracticaluses,1964–1980 .InJ.Nasi,(ed.) UnderstandingStakeholder Thinking .Helsinki:LSR-JulkaisutOy,97115.

Nord,W.1983: Apolitical-economicperspectiveonorganizationaleffectiveness .InK.S. CameronandD.A.Whetten,(eds), OrganizationalEffectiveness:AComparisonof MultipleModels .NewYork:AcademicPress,95133.

Nozick,R.1975: Anarchy,StateandUtopia .NewYork:BasicBooks.

Orts,E.1997: ANorthAmericanlegalperspectiveonstakeholdermanagementtheory . In F.Patfield,(ed.) PerspectivesonCompanyLaw ,(2),16579.

Paine,L.S.(1994): Managingfororganizationalintegrity . HarvardBusinessReview , (2),10617.

Pennings,H.andGoodman,P.1977: NewPerspectivesonOrganizationalEffectiveness . SanFrancisco:JosseyBass.

Pfeffer,J.andSalancik,G.1978: TheExternalControlofOrganizations .NewYork: Harper.

Phillips,R.2001: Stakeholderlegitimacy:Apreliminaryinvestigation .Georgetown UniversityBusinessSchoolWorkingPaper.Washington,D.C.

Rawls,J.1993: PoliticalLiberalism .NewYork:ColumbiaUniversityPress. Rhenman,E.1968: IndustrialDemocracyandIndustrialManagement .London: Tavistock.

governance,aspracticedintheUSA,unjustifiablyneglectstherightsandinterestsof otherconstituencies,suchasemployees,customers,suppliers,andcommunities.

Thischapterexaminesthestandardargumentfortheroleofshareholdersincorporate governance.ManydifferentjustificationsforAmericancorporatelawhavebeenoffered overtheyearsbut,in thepastthreedecades,aneweconomicapproachhascometo dominatethestudyofcorporatelaw.Inbrief,thisapproachviewsthecorporationasa nexusofcontractsamongitsvariousconstituenciesandregardsgovernancestructuresas attemptsbythesegroupstoreducethecostsofcontracting.Theargumentexaminedhere resultsfromtheapplicationofthiseconomicapproachtotheshareholders'role.Although theargumentisnotuniversallyaccepted,evencriticsacknowledgeitspowerand influence.More-over,criticsoftheargumenthavenotsucceededindevelopingan alternativetheoreticalapproachthatcouldgroundadifferentsystemofcorporate governance.Thislackofarivaltheorydoesnotmeanthattheeconomicapproachto corporatelawissound,butonlythat,atthepresenttime,thisapproachframesthe discussion.

ThepositiontakeninthischapteristhatthecentralroleofshareholdersinAmerican corporategovernanceisfullyjustified.Notonlydoesthestandardargumentprovide adequate supportfortheparticularbundleofrightsthatcorporatelawassignsto shareholders,butitdoessoinawaythatpermitsadequateconsiderationoftherightsand interestsofotherconstituenciesorstakeholders.However,thedefenseofthisposition turnsonmanycomplexandcontroversialissuesthataredifficulttoresolve.Tothe debate,eachsidebringsdifferentfactualassumptionsabouttheeffectivenessof alternativeeconomicarrangementsaswellasdifferentvaluejudgmentsabouthow economic activityoughttobeconductedandwhatitshouldachieve.Agreementabout suchmattersisunlikely,andsothebestthatcanbeachievedinthischapterisa clarificationoftheissuesthatadvancesthedebate.

TheContractualTheory

Thestandardargumentfortheroleofshareholdersincorporategovernanceisfoundedon aneconomicapproachthatiscommonlycalledthenewinstitutionaleconomicsorthe neweconomicsoforganizations.Untilrecently,neoclassicaleconomicanalysisoffered onlyarudimentarytheoryofthefirm(Hart,1989),butinthe1970s,economists,building onthepioneeringworkof RonaldCoase(1937),developedapowerfultheoryutilizing agencycostandtransactioncosteconomics(AlchianandDemsetz,1972; Williamson, 1975, 1985; Kleinetal.,1978; JensenandMeckling,1976; FamaandJensen,1983a, 1983b).TheseeconomistsfollowedCoase inmodelingthefirmasanexusofcontracts, inwhicheachcorporateconstituency,includingemployees,customers,suppliers,and investors,suppliessomeassetinreturnforsomegain.Thesecontractsincludenotonly explicitlegalcontracts,suchasemploymentandsalescontracts,inwhichthetermsare clearlyspecified,butalsolongtermrelationshipsbuiltonimplicitcontractsorshared understandings.Inaddition,thelawplaysacriticalroleincontracting.First,legislative statutesprovide“standardform”or“offtheshelf”contractsthatsavethepartiestheneed towritecontractsforeachtransactionandalsoservewhenthepartiesareunableto

thecostsofcontractingarisemainlyfromeffortstosolvetheseproblemsandfromany lossduetothefailuretofindasolution. Oneimportantkindofcostisthatincurredin monitoringtheperformanceofothers.Whenseveralpeopleworktogether,itmaybe possibleforoneormoretocontributelessandyetcollectthesameaseveryoneelse. AlchianandDemsetz(1972) arguethatworkersinthissituationwouldhireamonitor whosetaskistoensurethateveryonecontributesequally.Tothequestion“Who monitors themonitors?”theyrespondthatsuchmonitoringwouldbeunnecessaryifthemonitor wereofferedtheresidualrevenuesortheprofitoftheenterprise.Inshort,workerswould voluntarilyagreetoassignprofitstoathirdpartywhocouldsolvethemonitoring problem.

Monitoringispartofamoregeneralproblemarisingfromconflictinggoals. Organizationsbringtogetherpeoplewiththeirvariousgoals,mostofwhichareaimedat advancingtheirowninterests.Aneconomicorganizationofanysize mustdevelop mechanismsforenablingpeoplewithdifferentgoalstocooperateproductively.Thisis accomplished,inpart,bystructuringmanybusinessrelationsasagencyrelations,in whichoneperson,an agent,agreestoactonbehalfofanother,the principal (Jensenand Meckling,1976).Agencyrelationsarecriticaltotheorganizationofafirm,buttheyalso involvecosts,bothinmonitoringagents'performanceandinsufferinganylossfrom nonperformance.Thetaskofmonitoringagentsisespeciallyacutewhenthereis asymmetricinformation (aswhenonepersonhasinformationthatotherslack)and incompleteinformation (aswhencertaininformationisnotandperhapscannotbe known).Thesefeaturesaremostpronouncedinthecaseofthemanagersofanenterprise, whoaregenerallybetterinformedaboutimportantmattersandmustbetrustedintheir judgmentaboutthefuture(which,ofcourse,cannotbeknownwithassurance).The agencycostsofcontrollingmanagersareenormousandconstituteamajorportionofthe totalcostofcontractinginafirm.

Othercontractingcostsarisefromrisksthatarecreatedbyentering intocontractual relations.Onekindofriskresultsfromprovidingfirm-specificassetsthatcannoteasily beremovedfromproduction.Forexamples,employeeswhodevelopskillsthatareofuse onlytotheircurrentemployerorasupplierwhoinvestsinmachinerytomakepartswith onlyonebuyerbecome“lockedinto”theirposition.Notonlymaytheotherpartiestake advantageofthislock-in.butthebenefitofalong-termrelationmaybeupsetby unforeseendevelopments.Forexample,asupplier'ssolecustomermaydiscontinuea productorfindanothersource.Inaddition,arelationsuchasthatbetweenafirmandits employeesorsuppliersmaybeverycomplex,withtheresultthatthepartiesmaybe unabletoanticipateandplanforeverysituation.Thisisespeciallytruewhenpeoplehave “boundedrationality”duetoalimitedabilitytoacquireandprocessinformation(Simon, 1955,1957,1979,1997).Sopeopletakeriskswhentheyenterintoalong-termrelation fromwhichtheycannoteasilywithdraw(lock-in),whosedimensionscannotbefully grasped(complexity),andwhosefuturetheycannotpredict(uncertainty).Thecost of protectingoneselfagainsttheserisksorincurringalossbecauseofthemarealsopartof thecostsofcontracting.

Thefundamentalpropositionoftheeconomicapproachtothestudyofthecorporationis thatalleconomicorganizationscanbeunderstoodasanexusofcontractsthatresults frombargainingamongalltherelevantconstituenciesorcontractingparties,eachof whichisseekingtogainthemaximumbenefitfromengaginginajointproductive enterprise.Thechallengeforeachgroupistocontractwithafirmsoastoobtainthe greatestbenefitatthelowestcost,whichisprimarilyamatterofreducingthecostsof contracting.Morespecifically,thismeansdevelopinglong-termrelationsinacooperative endeavorwithprotectionagainsttherisksoflock-in,complexity,anduncertainty.The managersofafirm,whohavethetaskofmakingthesecontractsonbehalfofthefirm, facethesamechallengeoforganizingjointproductioninawaythatreducescontracting coststothemaximumfeasibleextent.Managersthusserveasanintermediarybetween thevariousconstituencies,contractingwitheachoneinawaythatcoordinatesthe contractsmadewiththeothers.

TheShareholder'sContract

Abusinessenterpriserequiresmanyinputs.Economists classifytheseasland,labor,and capital.Inaddition,afirmneedsmanagerialexpertisetocoordinatetheseinputs. Neoclassicaleconomicsassumesthateachproviderofaninputownsthatinputandthata managerorentrepreneuristheownerofthefirm,whobuysinputs,sellstheoutput,and pocketsthedifference.Thatis,profitisthecompensationreceivedbythemanager-owner forhisorhercontributionofmanagerialtalent.However,thisisnottheonlypossibility. Wecouldimagineagroupofworkerswhohiremanagerstocoordinatetheirproductive activityandwhokeeptheprofitsforthemselves.Alternatively,thesellersofaninput, suchasgrainfarmers,orthebuyersofanoutput,suchfarmerswhobuyseedsand fertilizer,couldhiremanagers toorganizethesaleoftheirgrainorthepurchaseofseeds andfertilizer,respectively.Theseareexamplesofworker-owned,supplier-owned,and customer-ownedfirms,andtheseformsofenterprise,usuallycalledcooperatives,are quitecommon(Hansmann,1996).Inmostlarge,publicly-heldcorporations,the providersofcapitalaretheshareholders,buttheroleofshareholderorownercanbeheld byanygroup.

Althoughshareholdersarecommonlycalledtheownersofacorporation,theconceptof ownershipasappliedtothemoderncorporationisdifferentfromitsordinaryuse (Schrader,1996).Nogroup“owns”GeneralMotors,forexample,inthesamewaythata personownsanautomobileorahome.Rather,shareholdershaveacertainbundleof rights, whichincludetherightofcontrolandtherighttoreceivetheresidualrevenuesor profits(Hansmann,1996).(Residualrevenuesarethenetearningsofafirm,whichisto saytherevenuethatremainsafterallfixedobligationsaremet.)Therightofcontroland therighttotheresidualarelogicallyseparate,whichistosaythattheycouldbeheldby differentgroups.Indeed,inanot-for-profitcorporation,trusteesexercisecontrolbutare legallybarredfromanypersonalbenefit.(However,anonprofitcorporation,strictly speaking,hasnoowners;itisanassetheldintrustforsomebeneficiaries.)Inpractice, therightofcontrolandtherighttoresidualearningsgotogetherbecausetherighttothe residualwouldbeinsecurewithoutcontrol.Nogroupwithoutarighttoresidualearnings wouldhaveanincentivetooperateafor-profitcorporationsoastomaximizethese

Inadditiontothekindsofcontractingcostsintroducedsofar,thereareothercoststhat attachspecificallytotheassumptionoftherightofcontrolandtherighttoresidual earnings.Althoughtheserightsareusuallyregardedasbenefits,theirexerciseinvolves coststhatmustbeconsideredbyanygroupthatseekstobe theshareholdersorownersof afirm. HenryHansmann1996)identifiesthese“costsofownership”asthecostsof controlling managers,thecostsofcollectivedecisionmaking,andthecostsofrisk bearing.Thefirsttwocostsareinvolvedintherightofcontrolandthelatterintheright totheresidual.

First,controllingmanagersincurscostswheneverthereisaseparation ofthelegalright ofcontroland defacto day-to-daycontrolofacorporation,which BerleandMeans(1932) calledtheseparationofownershipandcontrol.Infirmsthatarestillrunbytheowners, thereisnodivergenceofinterestsinasmuchasthemanagersandtheshareholdersarethe samepersons.However,BerleandMeansobservedthatascorporationshavegrownin sizeand outlivethefounders,theiroperationsareincreasinglycontrolledbyprofessional managerswhoseinterestsdifferfromthoseoftheshareholders.Theassumptionisthat managers,ifnotrestrained,wouldseektoenrichthemselvesbylavishpayand extravagantperquisites.Otherpossibilitiesincludeself-dealing(forexample,owninga supplier),competitionwiththefirm(asintakinganinvestmentopportunityforoneself insteadofthefirm),andexcessiveretentionofearnings(alsoknownas“empire building”),whichinflatesthesizeofthefirmandhencethemanagers'importance.These costsareaformofagencycostsandincludeboththecostsofmonitoringmanagersand thelossesthatresultfromafailuretopreventthemfrompursuingtheirinterests tothe detrimentofthefirm.

Second,decisionmakingisacostlyprocessevenwhenonlyonepersonhascontrol becauseoftheneedtogatherandprocessinformation.Whentwoormorepeoplemake decisionscollectively,furthercostsareincurredinresolvingtheinevitabledisagreements. Evenpeoplewiththesameinterestmaydifferintheirjudgmentofthemosteffective courseofaction,butdifferencesofinterestcreatemoreprofoundconflicts.Forthis reason,thecostsofownershiparereducedwhen onlyoneconstituencyhascontrol. However,themembersofanygivenconstituencymayhaveconflictinginterests,which resultinsomedecision-makingcosts.Forexample,investorsmayhavedifferentrisk preferencesortimehorizonsthatleadthemtofavororopposecertaindecisions. Moreover,thecostsofdecisionmakingincludenotonlythecostofthisinvestmentbut alsoanylossescausedbylessthanthebestdecisions.Gooddecisionmakinginan organizationrequiresasubstantialinvestment,butno amountofmoneycanguarantee thatthebestdecisionswillbemade,sosomelossesofthiskindareinevitable.

Third,businessisaninherentlyriskactivity,andthisriskcanbesharedbyeveryoneor bornebyasinglegroup.Anycorporateconstituency thatprovidesanassettothefirmin returnforaclaimonresidualrevenuesassumesalargeportionoftheriskofthe enterpriseandinsodoingprovidesaservicetoeveryoneelse.Everycontractorwitha firmassumessomerisk,butalllegalobligationstothosewithfixedcontractsmustbe metbeforeresidualclaimantsreceiveanyofafirm'srevenues.Residualclaimantsarenot guaranteedanyspecificreturn,andtheirpaymentistheonlyobligationthatafirmcan

failtomakewithoutbecominginsolvent.Thus,bondholderswhoarenotpaidcanforcea companyintobankruptcy,whileshareholderscanonlycounttheirlosses.Therighttothe residualisabenefitthatisoftenthoughttomakeshareholdersespeciallyprivileged,butit comesataprice, namelythecostofbearingtheresidualrisk.

Wearenowinapositiontounderstandtermswhycertaininvestorswouldcontractwitha firmtobetheownersortheshareholders,andwhyotherconstituencieswouldcontract differentlyandbewillingtoallowtheseinvestorstoassumethisrole.Thecontractual theoryexplanation,inbrief,isthatthesystemofcorporategovernancethatprevailsin mostlarge,publiclyheldcorporationsisthatwhichenablesallconstituenciestogainthe greatestbenefitfromjointproductionatthelowestcontractingcost.Manybusiness organizationsadoptothergovernancestructures,suchasthoseofsoleproprietorships, partnerships,cooperatives,mutualcompanies,andthelike,butthetheoryexplainsthese aswellbynotinghowthecostsandbenefitsarealteredbydifferentconditions.Thereis nooneidealformofcorporategovernancethatisappropriateinallcircumstances,and rationalcontractorswillexperimenttofindthemostsuitableforms.

Thisbriefexplanationomitsmanycriticaldetails,andsoweneedtounderstandmore specificallyhowsystemsofcorporategovernanceresultfromcontractingbyallofthe relevantconstituencies.Thatis,howdowegetfromcontracttocorporategovernance?

FromContracttoCorporateGovernance

Peoplewithcapitalareasnecessaryforproductionasworkersandthesuppliersofraw materials,buttheyarenotownersofanenterprisemerelyinvirtueofprovidingcapital. Indeed,lendersandbondholders,whoprovidecapitaldonothavetherightofcontrolora righttoresidualrevenues.Theinvestorswhoprovideequitycapitalgenerallyholdthese rights.Equitycapital,bydefinition,iscapitalthatisprovidedwithouttheobligationto repayovertimetheprincipalwithinterestthatdefinesloansandbonds.Itiscapitalthatis providedforthelifeofthefirmwithwhateverguaranteestheinvestorscanobtain.From theinvestors'pointofview,theremustbesomeadvantageinprovidingequitycapital ratherthandebtcapital.Fromacompany'spointofview,theremustbesomeadvantage inobtainingequityratherthandebtcapital.Intheory,afirmcouldobtainallthecapitalit needsbyborrowing – thatis,bytakingondebt – buttherearemanydisadvantagesto operatinginthismanner.Thecreationoftheinvestor–ownedfirmcouldbeexplained fromeitherpointofview,butitisperhapsbetterexplainedbyaskingwhyfirmswould seekequitycapitalandwhattheyneedtodotoattractit.

Capital,likeanyotherinput,isobtainedinamarket.Managersoffirmsseekcapitalat thelowestcost,whiletheownersofcapitalseekthehighestreturn.Thereisalimittothe amountofcapitalthatafirmcanraisethroughborrowingfrombanksandissuingbonds becauseofthe increasingrisk.Asafirm'sdebtobligationsconsumeagreaterportionof itsrevenues,theabilityofthefirmtomakeitsdebtpaymentsbecomeslesscertain.Ifthe riskissharedwithallconstituencies,thentheywilleachdemandhigherreturnsfortheir inputs,orelsegotootherfirmswheretheriskislower.Notonlythecostsofcapitalbut alsothecostsoflaborandrawmaterialsrisewiththerisk.Thesolutionistopersuadeone

classofinvestorstoprovidecapitalinreturnforafirm'sresidualrevenues,sothatthose investorsassumeapreponderanceoftherisk.Soleproprietorshipsandpartnerships functionwithoutshareholders,buttheindividualsinvolvedassumegreatrisk.Suchfirms typicallyrequirelittlecapitalorelsehavegreat difficultyraisingsufficientcapital,and theyoccasionally“gopublic”toshareriskandobtainneededcapital.Lessfrequently, publicfirmswill“goprivate”throughamanagementbuyoutoratakeoverinwhichthe newownersassumegreaterriskandprovidetheirowncapital.

Managersoffirmscanobtaincapitalatalowercostiftheyreducetherisktoinvestors. Forexample,theinterestrateonbondsislowerforfirmsthatobtainahigherratingfrom investorservicescompaniessuchasMoody'sandStandard&Poor's.Theriskforresidual riskbearerscanbereducedbytheadoptionofformsofcorporategovernancethataddress themajorcontractingcosts,especiallythecostsofownership.Corporationshavewide latitudeinchoosinggovernancestructures.First,intheUSA,corporatelawisthe provinceofthestates,andsostatescancompeteforchartersbyvaryingthetermsthey offer.Althoughsomewriterscomplainofa“racetothebottom,”inwhichstatescompete tooffertermsthatfavormanagementovershareholders(Cary,1974),othersarguethat competitionamongthestatesproducescorporatelawthatstrikesanideal balance(Winter, 1977; Romano,1993).Second,muchcorporatelawis“default”legislationthatcanbe “contractedaround”bypartiesthatsochoose.Thatis,corporatelawprovidesabasic modelthatcorporationsmayaltertosuittheirneeds.Sothe reductionofcontractingcosts isamajorconsiderationintheadoptionofspecificformsofcorporategovernancebya firm.Bychoosingonegovernancestructureoveranother,firmscompetewitheachother inattractingequitycapital,andfirmsthatmake amistakeintheirchoicepayapricein themarketforcapital.

Ifchoosingasystemofcorporategovernanceisamatterofdeterminingwhich constituencycanassumetheroleofowneratthelowestcost,thetaskmightseemtobe dauntingbecauseofthe informationrequired.However,ifthischoiceislefttothemarket, thenthebestformsofcorporategovernancewillemergethroughcontractingamongall therelevantconstituencies.Thatis,employees,customers,suppliers,investors,andother groups,willcalculateforthemselvesthecostsandbenefitsofownership,aswellasthe costsandbenefitsofotherarrangements,andexpressthesecalculationsinthe marketplace.Governancestructuresthatarenotefficientwilldisappear,alongwiththe firms thatadoptedthem,inaDarwinianstruggleforthe“survivalofthefittest.”Thus, corporationsneednotbedesignedinonefellswoopbysomeknowingmindbutcan emergefromthemyriadchoicesofindividualsovertime.However,atheoretical explanation ofthecost-reducingadvantagesofthedominantsystemofinvestor ownershipcanbeofferedbyconsideringthethreecostsofownership,namelythecosts ofcontrollingmanagers,thecostsofcollectivedecisionmaking,andthecostsofrisk bearing.

First,noconstituencywouldassumethecostsofcontrollingmanagersunlessthe expectedreturnsexceedthecosts.Generally,residualriskbearers,whoreapthefull benefitofimprovementsinmanagementperformance,gainthegreatestreturnfrom incurringthesecosts.Inthestandardargument,residualriskbearersoughttohave

morewillingtoacceptgreaterriskfortheprospectofahigherreturn.Again,lessaffluent employeesgenerallypreferthesafetyofaknownpaychecktotheuncertaintyof receivingaportionoftheresidual.

Forthesereasons,equitycapitalproviderscangenerallyincurthecostsofownership at lowercostthanotherconstituencieswiththeresultthatthetotalcontractingcostsofall constituenciesisreduced.Undersomecircumstances,however,therearebenefitstosome otherconstituencythatmakeitadvantageousforthatgrouptoobtain control.For example,employeeownershiptypicallyoccursintroubledcompaniesinwhich employeesareaskedtoacceptlowerpaytoenablethefirmtosurviveorelseassume greaterrisk,includingthenonpaymentofpromisedwagesorevenunemployment.The potentiallosstoemployeeswhoarelockedintosuchafirmmayoffsetthecostsof ownershipandleadthemtoseekcontrol.Inaddition,customerswhoareforcedbya singlesellertopayhighpricesmayreducetheiroverallcostsbyformingacooperativein whichtheycontrolthesupplier.Similarly,suppliers,suchasmilkproducersorcranberry growers,whohaveonlyonecustomercanavoidlossfromthemarketpowerofthebuyer byobtainingcontrol.LandO'LakesandOceanSprayareexamplesofproducer cooperativesforthemarketingofdairyproductsandcranberryjuicerespectively.

Whetheracorporationisownedbyinvestors,employees,customers,suppliers,orsome otherconstituencyisdeterminedbythecostsandbenefitsofownershipasreflected inthe marketchoicesmadebyeachgroup.Thestandardargumentholdsthatwhateverthe assignmentofownership,theresultingsystemofcorporategovernanceisoptimalnot onlyfortheconstituencywithcontrolandaclaimontheresidualbutalsoforallother constituencies.However,theideathatallgroupscanbenefitfromownershipbyone grouprequiresfurtherexplanation.

ProtectingOtherConstituencies

Inthecontractualtheory,everyconstituencyentersintoarelationshipwithafirm. Althoughcontractsareusedbyeachgrouptobuilditsrelationship,thetypeofcontracts andthetermsofthesecontractsaredifferentbecauseeachgrouphasuniquecontracting problemsthatrequiretailor-madesolutions.Wehavepreviouslyobservedthatthe problemsofcontractingaredueprimarilytotheneedtoprotectfirmspecificassetsunder conditionsofcomplexityanduncertainty.Inpractice,thereareagreatmanywaysforall constituenciestoprotectthemselvesandtoplanlong–term,beneficialrelationshipswitha firm,andthemeanschosenbyonegroupneednotbe,andprobablywillnotbe,thesame asthoseadoptedbyanother.Theimportantquestioniswhethereachgroupisadequately protected.Thatis,aretheyallwellservedbythemultiplicity ofrelationshipsthat constitutethenexus-of-contractsfirm?

Thestandardargumentholdsthat,ingeneral,theinterestsofnonshareholder constituenciesarebestprotectedbyavarietyofsafeguardsthatareunrelatedtotheright ofcontrol.Incontrast,shareholderinterestsareverydifficulttoprotectbythesamekind ofsafeguards,andsocontrolrightsarethemeansthatbestprotecttheuniquely vulnerableinterestsofshareholders.Thispartoftheargumentinvolvesseveralpoints.

First,itshouldbenotedthatcontractingisnottheonlysourceofprotectionforcorporate constituencies.Inparticular,eachgroupcanseektoavoidlock-in,anddoingsois advantageoustotheextentthatthegainsexceedanyloss.Forexample,asupplierhas greaterprotectionwhenitsellstomanybuyers.Asuppliermightmakemoreprofitby sellingonlytoonefirm,buttheresultinglock-increatesgreaterrisksthatmustbe weighedagainstthebenefits.Generally,consumerswhomakeone-timepurchasesand have awideselectioncanavoidbeinglockedin,ascanemployeeswithhighly marketableskillsinatightlabormarket.Inshort,themarketplaceitselfprovidesaform ofnoncontractualprotection.

Second,eachconstituencycanseektowritecontractsthatcovereveryaspectofa relationshipandanticipateeverycontingency.Manysalescontractshavedetailed provisionsconcerningtherightsandobligationsofeachparty,andunioncontracts provideasimilarlevelofprotectionforemployees.Suchexplicit contractinginvolves considerabledirecttransactioncosts,aswellasotherindirectcostsfromalackof flexibility.(Forexample,unionemployeesmightbemoreproductivewithoutcertain workrulesintheircontracts,butiftheycannottrustemployers tosharetheproductivity gainswiththem,thentheyarebetteroffwiththeproductivityhinderingrules.)An alternativetorelativelycomplete,explicitcontractsisrelationalcontracting(Macaulay, 1963; Macneil,1978; GoetzandScott,1981).Relationalcontractsgenerallycommitthe partiestosomecommongoalratherthanaspecificcourseofaction,andcompliance with thecontractisjudgednotbywhethersomeactionisperformedbutwhethereachparty hasmadea“besteffort”attempttoachievethegoal(GoetzandScott,1981).Themost prominentuseofrelationalcontractingisthecreationofagencyrelations,wherebya principalseekstoovercomethecontractingproblemscausedbycomplexityand uncertainty,aswellasinformationasymmetry,byengaginganotherpersonasanagent.

Third,thelegalsystemprovidesmanyprotections.Inadditiontoofferingstandardform contractsandgap-fillingjudicialinterpretations,thelawalsocreatesmanyrightsand obligations.Forexample,customersbenefitfromconsumerprotectionlegislationthat setssafetystandards,aswellasfromtortlawthatenablesthemtosueforinjuryfrom defectiveproducts.Inaddition,manytermsofsale,includingwarranties,aresetbylaw. Onthewhole,consumersintheUnitedStatesareverywellprotectedbyacombinationof explicitcontractsandlegalsafeguards.Similarly,employeesarewellprotectedbythe vastbodyofemploymentlawandbyworkerprotectionlegislation;andinvestors,suchas bondholders,areprotectedbythebodyofsecuritieslawandbytheBankruptcyCode (whichspecifiestherightsofdebtholdersintheeventofinsolvency).

Turningnowtothepositionofshareholder/owners,whichisanyconstituencythathasthe rightofcontrolandarighttoresidualrevenues,therightofcontrolitselfisthechief meansforprotectingtherighttotheresidual.Controlbyitselfconfersnobenefitand wouldnotusuallybesoughtasanendforitsownsake.Thevalueofcontrolliesratherin whatitenablesonetoachieve.Ordinarily,controlisofvaluetoresidualriskbearers becausethisisarelativelyeffectivemeansand,moreimportantly,virtuallytheonly meansforthemtosafeguardtheirpromisedreturn.Bycontrast,groupsthathave noclaim ontheresidualareusuallybetterprotectedbyothersafeguards.

Itisworthnotingthatfiduciarydutiesarenotowedsolelytoshareholders.Manystates havemodifiedthefiduciarydutyprincipleintheeventofatakeoverbidtopermitthe considerationofotherconstituencies(Orts,1992).TheEmploymentRetirementIncome SecurityAct(ERISA)imposesafiduciarydutyonmanagementinthehandlingof employees'retirementfunds(LittleandThraikill,1977).Thesedevelopmentsreflecta judgmentbylegislaturesandcourtsthatthecontractingproblemsofnonshareholder constituenciesinthesesituationsarebestaddressedbymeansoffiduciaryduties.

Theargumentforassigningfiduciarydutiesprimarilytoshareholders,then,isthatthis arrangementsolvesacriticalcontractingproblemforthisgroup;thatthissolutionwould belesseffectiveiffiduciarydutieswereowedtoothergroupsaswell;andthat,inany event,othergroupshavemoreeffectivemeansforsolvingtheircontractingproblems.

TheJustificationofCorporateLaw

Thecontractualtheoryofthefirm,aspresentedsofar,holdsthatAmericancorporatelaw representswhatpeoplewouldhavenegotiatedhadtheybeenabletodoso(Easterbrook andFischel,1991).Thisclaimassumesthatmuchcorporatelawratifiestheeconomic choicesindividualshaveinfactmadeandalsoreflectstheattemptsoflegislatorsand judgestoanticipatethechoicesthatthepartiesmighthavemade.Inboth instances,there isasearchforgovernanceformsthatreducethecostsofcontracting,whichistosaya searchforthemostefficientownershipstructures.Insofarascorporationsresultfrom privatecontracting,theycanbejustifiedinthesamewayas anyoutcomefromfree marketexchange.However,justbecausepeoplewouldcontractsoastocreateagiven formofcorporategovernance,itdoesnotfollowthatthisformisjustified.Putdifferently, efficientstructuresarenotforthatreasonjust.Efficiencyisamoralgood,butitmaynot betheonlymorallyrelevantconsiderationincorporategovernance.

Aguidingethicalprincipleofthecontractualtheoryisthatwheneverpossiblepeople shouldbefreetochoosethetermsoftheireconomicrelationswithothers.Thisprinciple canbegroundedeitherinlibertarianism,whichmakesindividualfreedomofchoicea fundamentalvalue,orinutilitarianism,whichjustifiesfreemarketchoicesforthereason thattheyproducehigherlevelsofwelfare.Both libertarianismandutilitarianismrequire manybackgroundconditionsforthejustificationoftheoutcomeofpeople'sfreechoices. Economistscommonlystresstheneedforperfectcompetition,perfectinformation,and theabsenceofforceandfraud,andtheyalsorecognizeinstancesofmarketfailurethat mayrequiregovernmentregulation.Moreover,anorganizationalformcanbemorally justifiedasanoutcomeofcontractingonlyiftheconditionsforfaircontractingare satisfied.Thatis,anyethicaltheorythatgroundstheprincipleoffreechoicemustenable ustodeterminewhenacontractisgenuinelyfairandnottheresultofcoercion,fraud,or unfairadvantagetaking.

Althoughthestandardcontractualargumentfortheprevailingsystemofcorporate governancemightbecriticizedonthegroundsthattheconditionsforfaircontractingare notsatisfied,thecriticsgenerallymountabroaderchallengetotheideathatcorporate

lawshouldbeformedmerelybyconsideringhowindividualsdoorwouldcontract. Specifically,criticschargethatacontractualapproach:

1reinforcesexistingimbalancesofpoweramongvariousconstituenciesandeven createsabiasinfavorofshareholders;

2failstoaddressadequatelythesocialcostsorexternalitiesofcorporateactivities; and

3overlooksthepublicnatureofcorporationsandtheirroleinsociety.

Letusexamineeachofthesechargesbriefly.

Safeguardsandpower

Objection

Thecontractualtheoryassumesthateachconstituencyisabletoprotectitself byselecting thesafeguardsthatarebestsuitedtoitssituation.Thesesafeguardstakemanyforms,and, accordingtothetheory,thefactthatshareholdersprotectthemselveswiththerightsof ownershipdoesnotnecessarilygivethemanyadvantageover employeesorcustomers whorationallychooseothermeansofprotection.However,ifsafeguardsmustbe bargainedfor,thentheinequalityofpowerthatexistsineverysocietywillbereflectedin thelawofcorporategovernance.Alargelydisempoweredworkforce,forexample,might beunabletosecureadequatesafeguardsinaprocessofbargaining,whileultrapowerful investorsgainmorethantheirrightfulshare.Moreimportantly,allindividualshavesome rightsthattheyshouldnothavetobargainforin amarket.Everyoneshouldbetreated fairlyandhavehisorherintereststakenintoaccount.Inshort,moraltreatmentisnota goodtobedistributedinamarketbutapreconditionforalleconomicactivity.

Reply

First,inequalityofpower,whichisa seriousmoralconcern,existsprimarilybetween individualsinasocietyratherthanbetweencorporateconstituencies.Allofusare consumersandmembersofcommunities;mostpeopleareemployees,andanincreasing numberareinvestors,especiallythrough pensionfunds.Asaresult,asubstantialequality ofpoweramongthesegroupsmaycoexistwithgreatinequalityamongindividuals.The contractualargumentisopentocriticismforalackofequalityonlyifoneormoregroups, suchasemployeesorconsumers,haveunequalpower asagroup.Moreover,ourconcern inthesevariousrolesshouldbethegreatestoverallbenefit.Thatis,employees(whoare alsoconsumers)shouldbewillingtoacceptlessinwagesif,bydoingso,theygaineven moreasconsumersthroughlowerprices.AninstructiveexampleisprovidedbyJapan, wheretherelativelyprivilegedpositionofemployeesisoffsetbyveryhighconsumer pricesandverylowreturnsonsavings.Arguably,individualJapanesemightbebetteroff onbalance iftheywerelesswelloffasemployees.

However,thisreplydoesnotaddresstheseriousinequalitythatremains.Manyworkers intheUSA,forexample,haveamuchweakerbargainingpositionthantheircounterparts

inEurope,andthisinequalityisnotwhollyoffsetbythebenefitstheyreceiveas consumersorinvestors.Whencompaniesreducetheirworkforceinordertoincrease profits,itappearsthatemployeeinterestsarebeingsacrificedtothoseofshareholders. Somecriticsarguethatthecurrentlawofcorporategovernanceundulyfavors shareholdersandthatthelawoughttobechangedtoredressthisimbalanceofpower. Theirproposalsincludeextendingthefiduciarytoshareholderstoincludeother stakeholders,givingstakeholdergroupsrepresentationonboardsofdirectors,and reducinglimitedliabilityforshareholders(Millon,1995).Eachoftheseproposalsneeds tobecarefullyevaluated,butcontractualtheoristsareskepticalabouttheefficacyof usinglegalrulestochangetheoutcomeofbargaininginamarket.Merelychangingthe rulesofcorporategovernanceisunlikelytocompensateforanyunderlyinginequalityof powersincemorepowerfulgroupscouldrespondbyextractingconcessionsonother matters(Maitland,2001).Inshort, legalrulesareweakinstrumentstocorrectimbalances ofpower.However,therulesofcorporategovernanceprofoundlyaffecttheefficiencyof firms,andsoanychangedesignedtoreduceinequalitymustbeweighedagainsttheloss ofefficiency.

Thepointthatrightsshouldnothavetobebargainedforinvolvestwomisconceptions. First,contractingitselfpresupposesarighttocontractandcertainminimalconditions, suchastheabsenceofforceandfraud,andcertainkindsoftreatmentofothersiswrong, notwithstandinganycontractualagreements.Forexample,exposingemployeesto unreasonablydangerousworkingconditionsismorallyimpermissible,evenwiththeir consent.However,aboveamoralminimum,therightsandobligationsofpartiesmay justifiablybeopentonegotiation.Thus,employersandemployeesmayjustifiably bargainoverthelevelofsafety,recognizingthatthechoicemayinvolveatradeoffwith othergoods,suchaswages.Thecontractualtheoryholdsthatmostoftherightsinvolved incorporategovernancearenotpartofamoralminimumbutarerightfullysubjectto bargaining.Wehavealreadynotedthatnogrouphasapriorclaimoncorporatecontrol andthatanygroupcanassumethisrole.Thecrucialquestion,therefore,isnotwhether somerightsexistantecedently – somedefinitelydo – butwhichrightsexistantecedently andwhichresultfromcontracting.

Second,themoralrequirementthateveryone'sinterestsoughttobetakenintoaccount doesnotprecludeafiduciarydutyto runacorporationintheinterestsofshareholders (MarensandWicks,1999).Inthecontractualtheory,theinterestsofemployees, customers,andotherconstituenciesarebestserved,generally,ifmanagersmakemajor corporatedecisionswithaviewonlytotheinterestsofshareholders.(Suchdecisionscan alsobedescribedasthosethatutilizeresourcesmostefficiencyandcreatethegreatest wealthforsociety.)Ifthisclaimistrue,thennonshareholderconstituencieswould consenttoasystemofgovernanceinwhichtheirinterestsarenotexplicitlyconsideredby management,assuming,ofcourse,thattheirinterestsarealreadyadequatelyprotectedby othermeans.Thisdoesnotmeanthattheirinterestsarenottakenintoaccount.Rather, theyaretakenintoaccount inthecontractingprocess,outofwhichthenexus-ofcontractscorporationisformed.Similarly,weshouldnotexpectacreditortoconsider ourinterestsincollectingadebt.Ourinterestsaretakenintoaccountwhenweborrow money,butwhenaloancomesdue,thereisnothingtobedonebuttoobservethe

agreement.Overall,asystemoflendingisinourinterest,andinsistingthatacreditor considerourinterestindecidingwhethertocollectaloanwouldunderminethissystem.

Theproblemofsocialcost

Objection

Businessactivitybenefitssociety,butitalsoimposessocialcosts.Afiduciarydutyto servetheinterestofshareholdersalonepermits,indeedseemstorequire,thatmanagers disregardthesecoststosocietyinthepursuitofshareholderbenefits.Socialcostsare commonlyviewedas externalities,whicharecostsofproductionthatarenotborneby theproducer.Acompanythatpollutes,forexample,isabletoutilizearesourceforwhich otherspaythecost.Notonlydomanagershaveadutytoignoreexternalities,whichare coststosociety,buttheyshouldseektoavoidinternalizingsuchcosts,byinvestingin pollutioncontrol,forexample.Suchadisregardofsocialcostscannotbejustifiedbythe contractualtheorywhencontractsbetweentwopartiesaffectthirdparties.Notonly shouldcontractorsbeawareofthird-partyeffectsasamatterofmorality,butnocontract canbejustifiedifitwrongfullyharmsothers.Thus,anycontractbetweenafirmandits shareholdersmustbemadewithaconcernfortheinterestsofotherconstituencies,andno contractcanjustifyactionsthataremorallywrong.

Reply

Theproblemofsocialcostistwofold.First,allcostsofproductionshouldbeweighed againstthebenefits,whichistosaythatproductionshouldbemaximallyefficient. Regardlessofwhobearsthecost,societyasawholeshouldgainthegreatestpossible benefitinreturn.Second,thecosts(aswellasthebenefits)shouldbedistributedinan equitablemanner.Intheory,bargaininginanexus-of-contractsfirmrevolvesaroundboth thecostsandthebenefitsofjointproductiveactivity.Thatis,workersbargainnotonly forwages(abenefit)butalsoforsafeandhealthyworkingconditions(becauseinjuryand illnessarecosts).Thus,thedistributionofsocialcostsis,tosomeextent,builtinto structureofafirm.Furthermore,itshouldmatterlittle,fromatheoreticalpointofview, whethercostsareexternalizedorinternalized.Ifinternalizedcostsarepassedalongto consumersinhigherprices,forexample,thenconsumersstillbearthecosts.Theproblem withexternalization isthatitleadstoaninefficientutilizationofresources.Theobjection, then,isnotthatfirmscreateexternalitiesbutthattheyimposesocialcoststhatreduce efficiencyandaredistributedunfairly.

Therearemanywaystoaddressbothoftheseproblemsofsocialcosts.Thatmanagers shouldhaveadutytoconsidertheeffectsonotherconstituenciesakintotheirfiduciary dutytowardshareholdersisonesolutionbutnotnecessarilythemosteffective.For example,workerscouldarguablyobtainmore protectionfromworkplacehazardsby bargainingforbetterworkingconditionsorbylobbyingforgovernmentregulation. Similarly,consumerprotectionlegislation,environmentprotectionlaws,andahostof otherregulatoryregimesprovidefarmoreprotectiontovariousconstituenciesthana relianceonmanagerialgoodwill.Thelegalsystempreventstheimpositionofsocialcosts

bymeansotherthanregulation.Forexample,tortlawenablespeoplewhoarewrongfully harmedtosuefordamagesandtherebylimitstheabilityofmanagerstoinflictcertain kindsofharmonpeople.Thus,thelawdoesnotpermittwocontractingpartiestoharm thirdpartiesinviolationoftheirrights.

Inaddition,marketscanservetointernalizecostsandtherebysecureboth efficiencyand fairness. RonaldCoase(1960) arguedthatexternalitieswouldnotresultinaninefficient allocationofresourcesiftherewereaclearassignmentofpropertyrightsforallresources andmeansforenforcingtheserightsatnocost.Undersuchconditions,thecostofall resourceswouldbefullyfactoredintoeconomicchoices.Thisinsight(calledCoase's theorem) underliesanapproachtopollution,forexample,thatassignsrightstopollute andrequiresfirmsexceedingpollutionlimitstopurchasetherightsfromlesspolluting firms.Awell-designedmarket-basedpollutioncontrolsystemmaybenotonlyefficient butalsofair,bydistributingcostsinaccordwithmarketchoices.

Contractualtheoristsnolessthantheircriticsareconcernedwiththeproblemofsocial costs.Theydisagreeprincipallyovertheuseofcorporategovernanceasasolution. Contractualtheoristsagreewiththeassessmentof EasterbrookandFischel(1991) thatwe shouldseektodistributeboththecostsandthebenefitsofproductiveactivityintheway thatallpartieswouldagreetoweretheyabletobargain.Theformofcorporate governancereflectsthechoicesthatthesepartieswouldmakeaboutgovernance structures,butthesechoiceshavelittlebearingondecisionsabouttheutilizationof resources.Howwemakethesedecisionisveryimportant,but,as Easterbrookand Fischel(1991,p.39)conclude,“Toviewpollution…orotherdifficultmoralorsocial questionsas governance mattersistomissthepoint.”

Thepublic/privatedistinction

Objection

Inthecontractualview,businessorganizationsareprivateassociationsofindividuals whocontractwitheachothertoachievetheirown(private)ends.However,corporations arenotmerelyprivateassociations;theyarealsopublicinstitutions,createdbysociety andendowedwithcertainprivileges,inordertoserveimportantpublicgoals.Although individualshavearighttocontractwithothersinthecourseofengaginginbusiness,the righttoincorporate,withitsattendantprivileges,isgrantedbysocietytoservesome sociallybeneficialpurpose.Moreover,conceivingthecorporationasanessentially privateassociationdeprivesemployeesandothergroupsfromactiveparticipationin decision-making.Onthecontractualview,acorporationisahierarchy,notademocracy. Thus,employees,forexample,areexpectedtoworkasdirectedbytheirsuperiors. However, ChristopherMcMahon(1994) arguesthattheuseofauthorityinbusiness organizationsismorallypermissibleonlyifitisdemocraticallyexercised.Thatis,all affectedgroupsshouldhaveasignificantvoiceinmajorcorporatedecisions.

Reply

Thecontractualapproachstartswiththeassumptionthatindividualscreateorganizations notonlyto servetheirownendsbutalsotoachievecommongoalsincooperationwith others.TheearliestlargeUScorporationswereformedtobuildrailroads,producesteel, andengageinotheractivitiesthatrequirethemarshallingofvastresources.Thereasons forincorporatingmustbestatedinacorporation'scharter.Thus,corporations do serve somelargerpurposes.Thesemayvaryaccordingtotheaimsoftheirfounders,butthey invariablyinvolvetheprovisionofeconomicgoodsandservices.Thefoundersmayalso choosewhethertoincorporateasafor–profitornot-for-profitorganization.Thischoice doesnotaffectthepurposesofthecorporationbutdetermineshowitisgoverned.For example,for-profitandnot-for-profithospitalshavethesameend – to providehealthcare – buttheformeriscontrolledbytrusteesonbehalfofsociety,thelatterbydirectors,who representtheshareholders.Thenot-for-profitformisappropriateifdonorscontributethe assetsofthehospital;thelatter,iftheassetsareobtainedfrominvestors.Ultimately,the governancestructureforahospitalwillreflecthowitisfinanced.

Althoughcorporationsmaybesaidtoexistwiththepermissionofsocietyinsomesense, wegranttheprivilegesthatenableindividualstodo businessinthecorporateform becauseoftheneedforlarge-scaleeconomicorganizationintheproductionofmost economicgoods.Wealsogainmaximumbenefitfromcorporationswhentheyoperate efficiently.Thecontractualtheoryassumesthatfindingthe mostefficientorganizational formsorgovernancestructuresisadifficulttaskandthat,forthemostpart,thistaskis bestlefttothemarketplace.Theproblemsaresufficientlycomplexthatamarket approach – whichleavesindividualsfreetoexperimentandallowsexperiencetoshowus thebestsolutions – ismorelikelytosucceedthananapproachthatviewstheseproblems asmattersofpublicpolicy.Ofcourse,weneedtomakesurethatimportantpublic concernsareadequatelyaddressed.Themainissueherebetweencontractualtheoristsand theircriticsiswhetherthepublicinterestshouldbeserveddirectlybymaking corporationspublicinstitutionsorservedindirectlybyleavingcorporationsinprivate hands,subjecttopubliccontrols.

Forexample,apublicornot-for-profithospital,nolessthanafor–profitfacility,should operateefficiently,makingthebestuseofitsresourcestoprovidehighqualitymedical care.However,apublicgood,suchascaringforindigentpatients,maybemore easily servedbyanot-for-profithospitalduetoitscomparativefreedomtobalanceefficiency withothergoals.Theresultinginefficiencyhasaprice,butitisapricethatsocietyis willingtopaytoensurethatthoseunabletopaydonotgowithout treatment.Bycontrast, afor-profithospitalwouldseektoavoidthecareofindigentpatientsinorderto maximizethereturntoshareholders.However,thepublicgoodofcaringforindigent patientscouldbeachievedwithinasystemoffor-profithospitalsbysuchmeansas governmentregulationthatrequirestreatmentorgovernmentpaymentforsuchservices. Bothsidesagreethatwewanttoobtainthebestmedicalcarefortheallocatedresources consistentwithachievingothersociallydesirablegoods, suchasequalaccesstomedical care.Inshort,weneedtomakesometrade-offbetweenequityandefficiency.Aslongas themembersofasocietyagreeon what trade-offtomake, how thetrade-offismade shouldbeimmaterial.Thesametrade-offcouldbemadewithasystemoffor-profitor not-for-profithospitals,andsothecrucialquestioniswhichsystemworksbestoverall.