Cover Designed By Jenna Jokhani

Cover Designed By Jenna Jokhani

Volume 2 | Issue 1 | Winter 2024

Founded in 2021, the Stanford Undergraduate Law Review is a student-run publication at Stanford University with the mission of providing a home for undergraduate scholarship on law with an emphasis on civil liberties. SULR accepts submissions from undergraduate students worldwide. By publishing a diverse array of articles drawing from a variety of academic disciplines, SULR seeks to cultivate the next generation of legal thinkers and heighten awareness of the importance of law as a tool of social progress.

Letter from the Editors-in-Chief

A City With A Mission of Structural Racism? Gabriel Frank-McPheter, Stanford University

Witnessing Racism: Black Womanhood as Lack of Credibility in Witness Testimony

Old Times They Are Not Forgotten: Challenges to Felony Disenfranchisement in Mississippi

Impossible Demands: Reparations, Racial Capitalism, and Human Rights

“A Race So Different”: Asian Americans in United States Supreme Court Decisions, 1889-1925

CLAUDIA SUNG HAILEY ROCHIN

Director of Content Director of Publishing Director of Outreah

GRACE GEIER

SERENA ZHOU PALOMA RONIS

VON HELMS

Senior Editors

NICOLE DOMINGO SERENA ZHOU

SKYLAR VOLMAN

LORA VACHOVSKA

LEXI KUPOR

ANDREW GERGES

JULIA DONLON

DIVYA MEHRISH

SAMIYA RANA

NADIA CHUNG

Content Staff

SAKSHI UMROTKAR

MEDHYA GOEL

General Editors

ASHWIN PRABU

ALEX ELLISON

GRACE GEIER

NATALIE WANG

GABRIEL FRANK-MCPHETER

GABRIELA HOLZER

LAISHA OZUNA

KYLE FEINSTEIN

BRANDON RUPP

CATHARINE CORLISS

GRETA REICH

ERICK ROCHA

OLIVIA JESSNER

DAVID LEE

NABIKSHYA RAYAMAJHI

JENNA JOKHANI

KIMBERLY SHIRAI

ABIGAIL MATSUMOTO

Dear Reader,

The editorial team is proud to present the second volume of the Stanford Undergraduate Law Review.

This collection of articles features a diversity of issue areas ranging from redlining in Los Angeles to felony disenfranchisement and reparations within the strictures of international law. Our student authors provide critical reflection on historical and racial injustices manifest in the law and the contours of society shaped by their legacies. Each offer a unique, pointed perspective on the institutions delimiting for whom civil rights and liberties protections are afforded— legal scholarship crucial for building a more just and equitable society. We encourage you to engage deeply and critically with their work.

We would like to thank the many contributors who have made the publication of this issue possible. Our dedicated student staff and editors have worked tirelessly to highlight the work of our writers over the course of the year They, along with our authors, are truly the foundation of the journal's success. We would also like to extend our sincere gratitude to the SULR Executive Team: Serena Zhou, Nicole Domingo, Grace Geier, and Paloma Ronis Von Helms. Their continued dedication and leadership has been invaluable to preserving the vision of the journal.

Hailey Rochin & Claudia Sung SULR Editors-in-Chief

How Redlining Angeles

Gabriel Frank-McPheter | Stanford University

Winter 2024

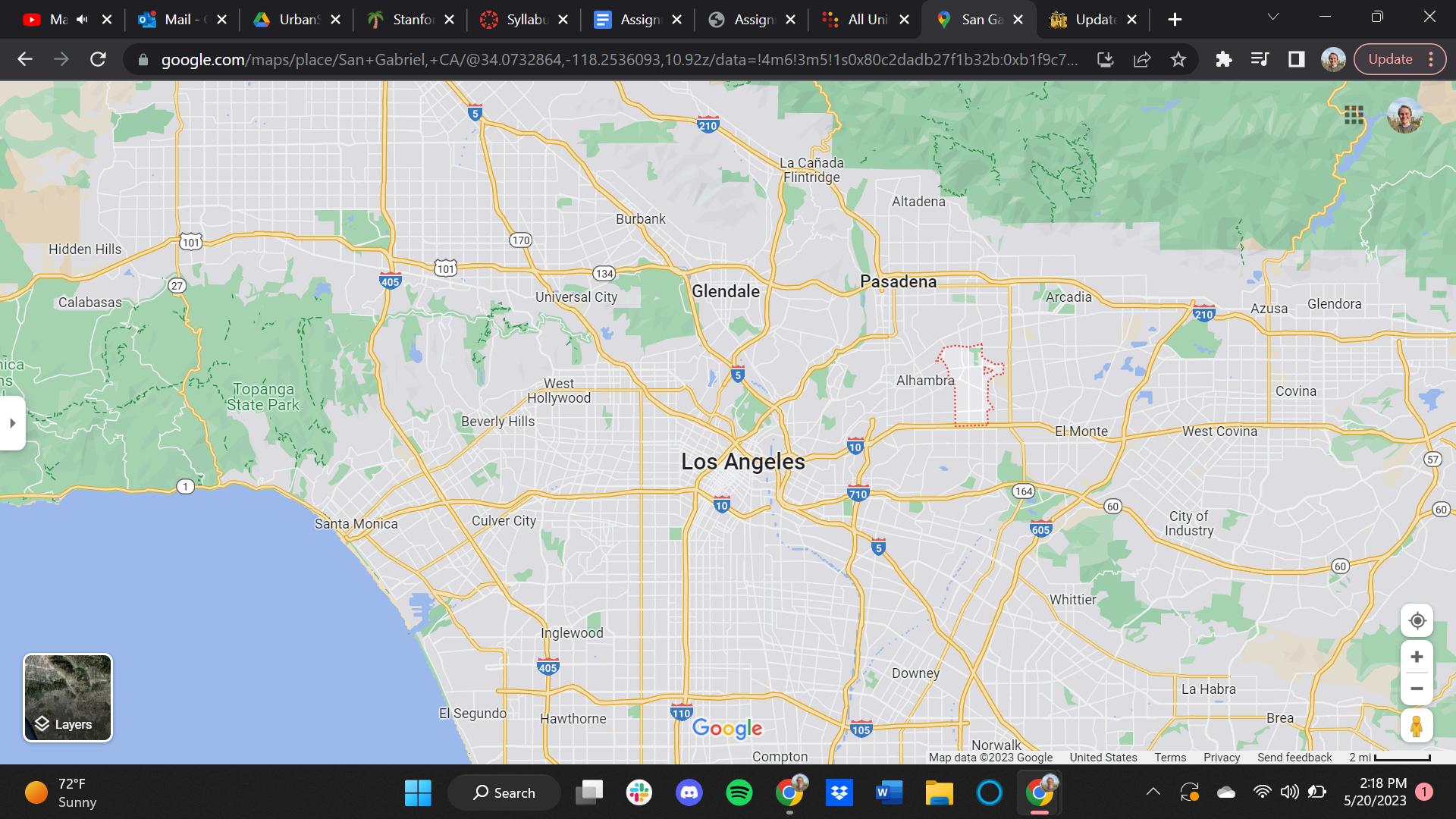

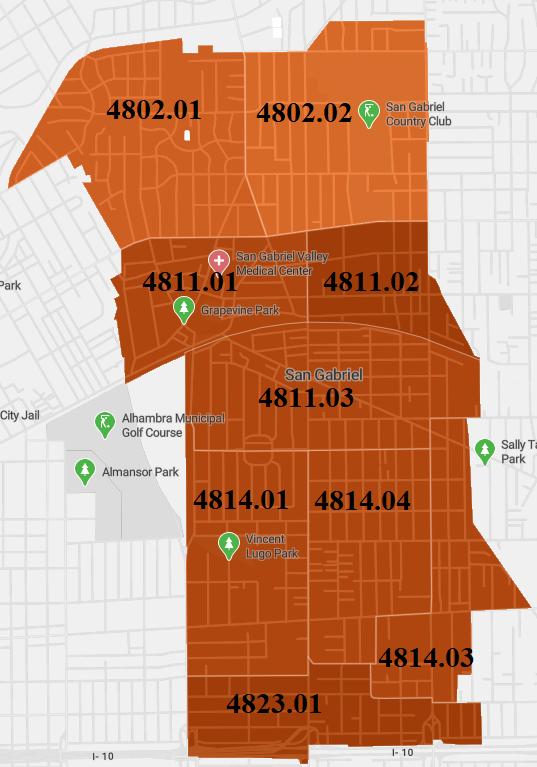

Los Angeles is the direct descendant of San Gabriel— a city that at first glance appears to be just another LA suburb, yet carries a past marred with colonialism, housing injustice, and economic change. In 1771, Spanish colonist and priest Junipero Serra founded the San Gabriel Arcángel Mission, subjecting the indigenous Tongva to “religious indoctrination, labor, restructuring of gender structures, and violence” (Yvette, 20). As California passed from Spanish to Mexican to American colonial hands, the San Gabriel Mission laid the foundation for the growth of Los Angeles, and still stands to this day. (see Figure 1). Playing on words, the present-day City of San Gabriel brands itself as a “City With A Mission” in official government documents and signage. But, what has the city’s symbolic mission throughout history been? From redlining, to rapid suburban development, to waves of Asian-American immigration, San Gabriel has a unique history of demographic and economic change worthy of substantial investigation. Based on historical redlining and trends in demographics and wealth, this paper focuses on what it classifies as the Mission Road Neighborhood of San Gabriel (Census Tracts 4811.01 and 4811.03, see figures 2, 3, 4, and 5). Statistical and historical evidence indicates that redlining produced economic disparity and Latino segregation in the Mission Road neighborhood, but also in part facilitated Asian-American migration that produced white flight and a gentrified ethnoburb.

The Mission Road neighborhood was deliberately redlined to segregate Latinos. In the 1930s-1940s, the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) assessed neighborhoods for “investment potential”, assigning them a letter grade and color often corresponding to the prevalence of people of color in the neighborhood, draining investment from minority communities and keeping them segregated (Coates, 58). What now makes up most of the Mission Road neighborhood was assigned the worst grade, a redlined “D13” (see figure 6, 7, and 8). In its description of the neighborhood, the HOLC wrote “Construction and maintenance are uniformly of poor quality and the area [sic] has an extremely shabby and ill-kept appearance… The vast majority of the population, while American-born, are still ‘peon Mexicans’, and constitute a distinctly subversive racial influence… hybrid Mexicans of American birth who are a distinctly less desirable type…This area is considered a menace to this whole section and pressure is being exerted to confine the population and keep it from infiltrating into other districts” (Mapping Inequality). Because Latinos were classified as “white” and San Gabriel was not divided into smaller census tracts, it is difficult to conclude if the Mission Road neighborhood was completely homogeneously Latino (See Figure 9). Nonetheless, the overtly racist language unambiguously demonstrates that the Mission Road Neighborhood was redlined to segregate Latinos.

This redlining produced economic disparity in the Mission Road neighborhood. According to HOLC’s description of the neighborhood, “Construction and maintenance are uniformly of poor quality and the area [sic] has an extremely shabby and ill-kept appearance.” HOLC went on to describe the population as “laborers, artisans and WPA [Works Progress Administration] workers. Income level $700 to $1200” (See Figure 8). Conversely, the North San Gabriel neighborhood, “greenlined” as a neighborhood ripe for development, was described as being racially “homogeneous,” with “good standard quality and architectural designs [that] are individually attractive and collectively harmonious… the area will continue its rapid growth.” Likewise, HOLC described the population as “Business and professional men, public officials, Jr. executives, and white collar workers. Income $1800-$5000.” Clearly then, in the 1940s, the population of the Mission Road neighborhood consisted predominantly of working class Latinos,

many of whom were likely direct descendants of the blatant colonization that took place at the Mission, or migrants from within or outside of the Los Angeles area who settled there given the pre-existing Latino community. Redlining, however, prevented these Latinos from accessing social mobility post-colonization, diverting the capital funds needed to improve the Mission Road neighborhood to the white and wealthy North San Gabriel area, while confining Latinos to Mission Road. As shown in Figure 8, disparities in income, home values, and demographics between the Mission Road and North San Gabriel neighborhoods consequently persist to this day Evidently, then, the law in the U.S. directly perpetuated economic disparities in San Gabriel traceable to colonialism.

Figure 6, Redlining Overlayed with Current Census Tracts (University of Richmond, Mapping Inequality)

Figure 7, Legend and Accompanying Chart for Figures 6 and 7 (University of Richmond, Mapping Inequality and Social Explorer)

HOLC Grade A18

Present-day Neighborhood North San Gabriel

2021 Census Track

4802.01, 4802.02

1940 Income $1800-$5000

Split between north and mission road neighborhoods; south of Las Tunas and west of Del Mar is Mission Road neighborhood

Portions of 4802.01, 4811.1, and 4811.02

Split between Mission Road neighborhood and an eastern neighborhood Mission Road Neighborhood Southern San Gabriel Neighborhood

Portions of 4811.1, and 4811.02

4811.01, 4811.03

4814.01, 4814.04, 4814.03

Figure 8, Demographic Makeup of San Gabriel, 1940 (Social Explorer)

As the suburb developed in the 1950s-1980s, ethnic heterogeneity increased, but economic disparity and racial segregation in the Mission Neighborhood persisted. In 1980, the

Mission Road Neighborhood was included in a larger census tract (See Figure 10), making the dataset not perfectly comparable with the previously redlined or present-day neighborhood.

Nonetheless, this central census tract had a plurality concentration of Latino residents at 46.9%, with a 44.2% non-Latino white population. Comparatively, the previously greenlined “homogenous” white North San Gabriel neighborhood had a non-Latino white population of 81% and a Latino population of just 13.1%. Likewise, median incomes in North San Gabriel were 64% higher than incomes in the central and southern tracts (See Figure 11). Thus, despite some increase in ethnic heterogeneity, disparities in geographic location and wealth between whites and Latinos persisted.

Moreover, redlining had an unintended consequence: depressed property values and ethnic heterogeneity likely encouraged the influx of Asian-American migrants. Excluded from homeownership in most white neighborhoods, Chinese and Japanese Americans in Los Angeles began immigrating to less racially restrictive Monterey Park and neighboring cities in the 1950s, forming an “ethnoburb” in the San Gabriel Valley (Cheng, 16). Consequently, in 1980, the Asian-American population in San Gabriel was 12.5% in the southernmost census tract, 7.3% in the central Mission Road Neighborhood tract, and just 4.9% in the northernmost tract (See Figure 11). Proximity to the increasingly Asian-American Monterey Park is likely in part responsible for these trends. However, given that Asian Americans immigrated disproportionately to neighborhoods previously red-lined as risky investment and “yellow-lined” as moderately risky investment, it is somewhat likely that redlining produced depressed property values and ethnic heterogeneity, partly motivating these migration trends.

Figure 10, Demographic and Income Distribution of San Gabriel in 1980 (Social Explorer)

Census Tract

4802 (North San Gabriel)

Census Tract

4811 (Central, Mission Road Neighborhood)

Census Tract

4814 (Southern San Gabriel)

Census Tract

4823.1 (Southernmost, Bordering Monterey Park)

By 2021, the Asian-American population in the Mission Road Neighborhood had exploded, but the legacy of redlining remained. A second wave of Asian-American immigrants, predominantly wealthier first-generation immigrants from China, formed an ethnoburb in the San Gabriel Valley (Chang). In 2021, San Gabriel had a 60.2% Asian-American population, and every census tract was plurality Asian-American. Nonetheless, the two tracts comprising the Mission Road Neighborhood (See Figures 4 and 5) still contain some of the largest Latino populations, at 32.9% and 35.0%, compared to 25.8% city-wide. Likewise, economic disparity persists: Mission Road Neighborhood tracts have the highest poverty level at 13.9% and 16.8% compared to 0% and 4.9% in the previously green-lined northern tracts; its median household income is $68,000 and $75,000 compared to $135,000 and $99,000; and 0% and 6% of homes are valued at above $1,000,000 compared to 31.7% and 26.3% (See Figure 13). These economic disparities and the disproportionate concentration of Latinos in the Mission Road Neighborhood

indicate that the legacy of redlining still somewhat affects the neighborhood.

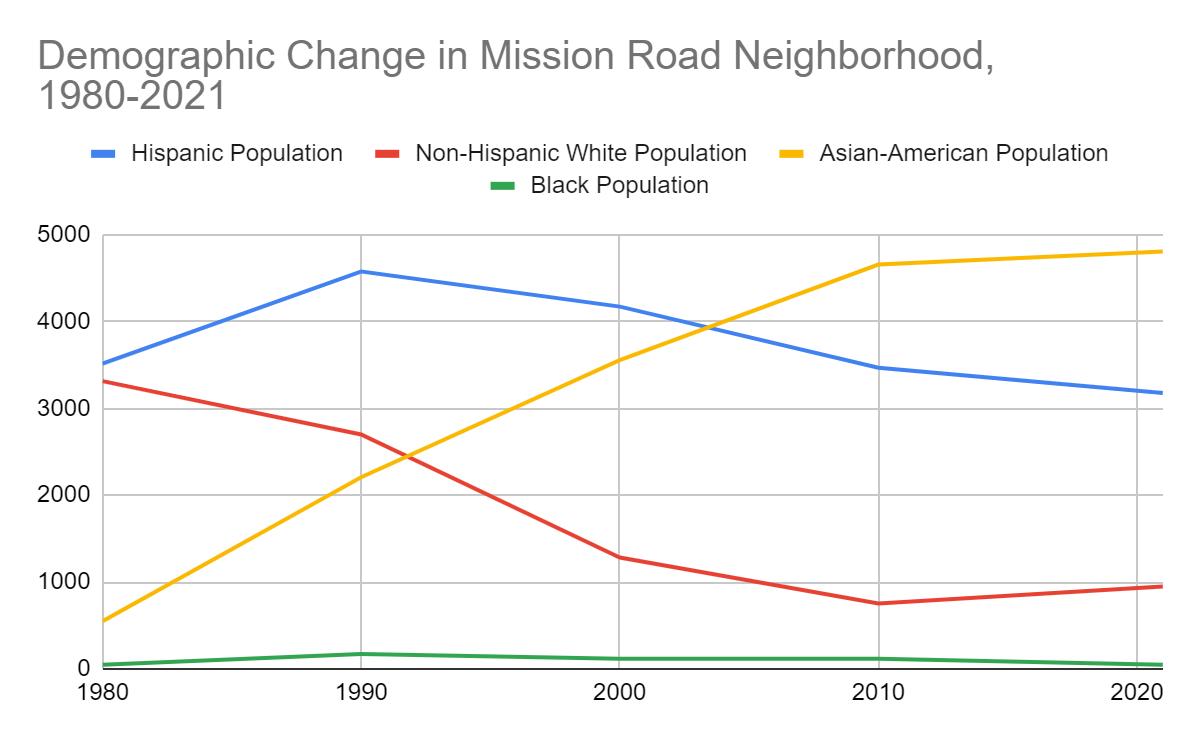

Moreover, it is evident that Asian-American immigration produced white flight across all neighborhoods, including the Mission Road Neighborhood. Scholars have recognized throughout California a “mobilization and suburbanization of segregation” as some denser, poorer suburbs became more segregated as middle-income whites fled areas with minorities (Schafran 27-30). Simultaneously, between 1980 and 2021, the Asian-American percentage of the population in the Mission Road Neighborhood sugred from 7.4% to 51.5%, while the non-Latino white population shrunk from 44.2% to 10.2% (See Figure 12). These extreme trends unambiguously demonstrate the occurrence of white flight as Asian Americans immigrated to the neighborhood.

However, Asian American immigration may be causing gentrification. Many academics have focused on the phenomenon of Black middle-class homebuyers moving into and gentrifying poor Black neighborhoods (Patillo, 85-86). A similar process of a racially marginalized but wealthier group gentrifying a racially and economically marginalized community may be occurring in the Mission Road Neighborhood. Luxury apartments are in construction at the previous site of a nursery (Figure 14). In 2021, the Chinese-American-owned, middle-income priced food court Blossom Market Hall opened next to the colonial site of the mission (Figure 15). Median home values in the Mission Road Neighborhood rose from between $150,000 to $299,000 in 1990 to a little under $750,000 in 2021. It is difficult to draw definitive causal conclusions from this data alone, but the Latino population has declined by over 30% from an apex of 4,574 in 1990 to 3,175 in 2021 (See Figure 13). These trends make it somewhat likely that Asian-Americans have gentrified the Mission Road Neighborhood and displaced some poorer Latino residents.

Figure 12, Graph of Demographic Change in Mission Road Neighborhood from 1980-2021 (Social Explorer)

Figure 13, Demographics, Income, and Home Values Across San Gabriel, 2021 (Social Explorer)

000

Historical and statistical examination produces nuanced understanding of the development of the Mission Road Neighborhood in San Gabriel. The neighborhood was redlined in the 1930s-1940s with overtly racist intentions of confining the Latino population, exacerbating and perpetuating economic disparity. Despite increased racial heterogeneity in the 1950s-1980s and beyond, disproportionate representation of Latinos and economic disparity in the neighborhood persists. Asian-Americans began to immigrate into the neighborhood in the 1950s-1980s, and rapidly immigrated in the 1980s-2021, likely in part because redlining depressed property values and prevented a white ethnic majority from discriminating against Asian-American home buyers. This, in turn, produced mass white flight from the area and potentially caused gentrification, with a changing business and real estate landscape, soaring home values, and a significant decline in the net and proportional Latino population. These conclusions, however, are limited. The previously redlined neighborhoods do not perfectly overlap with current or previous census tracts, causing some differences in the precise geographic regions examined. The data also does not allow for the examination of micro-segregation within neighborhoods, or income disparities between ethnic group. It is also difficult to determine conclusively the causal weight of redlining on Asian-American immigration, and the causal weight of Asian-American immigration on gentrification and the displacement of Latino residents. Nonetheless, it is clear that the legacy of redlining, and the failure of policymakers to address it, has perpetuated disparities in San Gabriel to this day.

Unfortunately, San Gabriel is not alone. As the birthplace of Los Angeles, its history is indicative of the broader trend in the City, State, and Nation. The lasting effects of redlining in San Gabriel demonstrate the ability of the law to perpetuate inequities for decades, and the need to wield the law to correct its mistakes. The failure of San Gabriel to adequately invest in previously redlined communities, protect tenants from displacement through policies like rent control, and address its history of legal wrongs demonstrates the need to ensure equal opportunity for all even after equal protections under the law are granted to end the most direct forms of discrimination. It’s time for the “City with A Mission” - and the rest of the country - to make its mission of protecting and investing in the communities the law has left behind.

Works Cited

Cheng, Wendy. “The Changs Next Door to the Diazes: Suburban Racial Formation in Los Angeles’ San Gabriel Valley.” Journal of Urban History 39, no. 1 (2012): 16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144212463548.

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. “The Case for Reparations.” The Atlantic, February 2, 2023. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/.

Cole, Carolyn. A fire at the San Gabriel Mission burned most of the roof and interior Photograph. San Gabriel, July 11, 2020. Los Angeles Times.

Kotowski, Jason. Lines form early for vendors inside Blossom Market Hall. Photograph. San Gabriel, February 12, 2022. KGET.

Pacific Plaza Premier Development Group. Pacific Square San Gabriel. n.d. Photograph.

Pattillo, Mary E. “The Black Bourgeoisie Meets the Truly Disadvantaged.” Essay. In Black on the Block: The Politics of Race and Class in the City, 85–86. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Robert K. Nelson, LaDale Winling, Richard Marciano, Nathan Connolly, et al., “Mapping Inequality,” American Panorama, ed. Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers, accessed May 23, 2023, https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=14/34.092/-118.116&city=los-angeles ca

San Gabriel Historical Walk - Mural. n.d. Photograph. Spanish Missions in California.

Schafran, Alex. “The Suburbinization of Segregation.” Essay. In The Road to Resegregation: Northern California and the Failure of Politics, 27–30. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2019.

Total Population, 2021. Social Explorer, (based on data from U.S. Census Bureau; accessed 23 May 2023 at 22:28:18 GMT-7).

Total Population, 2010. Social Explorer, (based on data from U.S. Census Bureau; accessed 23 May 2023 at 22:28:18 GMT-7).

Total Population, 2000. Social Explorer, (based on data from U.S. Census Bureau; accessed 23 May 2023 at 22:28:18 GMT-7).

Total Population, 1990. Social Explorer, (based on data from U.S. Census Bureau; accessed 23 May 2023 at 22:28:18 GMT-7).

Total Population, 1980. Social Explorer, (based on data from U.S. Census Bureau; accessed 23 May 2023 at 22:28:18 GMT-7).

Total Population, 1940. Social Explorer, (based on data from U.S. Census Bureau; accessed 23 May 2023 at 22:28:18 GMT-7).

Witnessing Racism Witness Testimony Winter 2024

Seeing Black is always a problem in a visual field that structures the troubling presence of Blackness.” - Nicole Fleetwood

I am going to tell you about a time that I fell victim to implicit racial bias. Implicit racial bias is “a negative attitude, of which one is not consciously aware, against a specific [race].” This instance of bias was a time when my thoughts conflicted with the anti-racist 1 agenda I’ve laid out for my life. As a Black woman, I had never thought of myself as having racial bias against Black women. Sitting in a courtroom on the seventh floor of the Los Angeles Central District Court, that perception changed. Here’s what happened.

At home, I work as an intern for a federal judge, and the cases that come through his court frequently involve Black people, both in the audience and on the side of the defense. During one sentencing, the daughter of a murder victim came up to the podium to give a statement of victim impact, and I am ashamed to reflect on the thoughts that came into my head when she began to speak. She was a young Black woman, and I remember looking at her outfit—tight athleisure, Yeezy slides, and big gold hoops—and wondering why she didn’t wear something more professional to court. I remember looking at her hair, worn natural, and wondering why she didn’t put any more effort into making it look presentable At the time, I was also shocked by her use of African American Vernacular English (AAVE). These thoughts, about factors of her appearance completely separate from the powerful statement she was making, prevented me from absorbing the full message of her speech. She was speaking about the profound impact her father ’s murder had on her Why was I musing about her appearance and language use?

During that experience, I called myself out and began reflecting on the thoughts going through my head. Not everyone would have done that, in fact, I’d wager most people wouldn’t have done that, and that lack of awareness can have huge consequences— consequences exemplified by the treatment of one Rachel Jeantel.

Rachel Jeantel is a young Black woman who was a key witness in the trial for policeman

1 American Psychological Association, Implicit bias, https://www.apa.org/topics/implicit-bias.

George Zimmerman’s killing of Trayvon Martin. Jeantel’s testimony was meant to be a turning point for the trial, and it did end up making an impression, but not for the reasons it should have. In the media and in the courtroom, Jeantel’s entire being was picked apart. Being of Haitian and Dominican descent, her citizenship was called into question. Being a woman, her romantic 2 history (or, truly, lack thereof) with Martin was called into question. Being a Black woman, her 3 size, language use, and overall respectability were all called into question. Something that was 4 rarely, if ever, focused on by the public was her actual testimony. Jeantel lost her credibility because of her persona, which was inextricably tied to Blackness, but nowhere in any legal document is a witness required to comport themself as another race. So where is the expectation of whiteness coming from? Ruminating on that question led me to ask the central question: How do respectability politics and implicit racial bias affect the treatment of Black women’s witness testimonies in the courtroom? In my research, I have come to the conclusion that implicit anti-Black racial bias in the courtroom necessitates the unfair usage of respectability politics, specifically for Black women witnesses. Due to courtroom elevation of whiteness, marginalization and ostracization of Blackness, and jury bias against Black womanhood, Black women witnesses are forced to employ respectability politics in order to gain any semblance of credibility in the courtroom, ultimately sacrificing racial justice in rejecting honest self-expression.

A key term that I mentioned in my central question is respectability politics, which must be defined and subsequently explored in answering this question. The term “respectability politics” was coined in 1993 by Black woman and Harvard professor of African American Studies Evelyn Higginbotham. She used the term to refer to how “early 20th century Black women presented themselves as polite, sexually pure, and thrifty to reject stereotypes of them

2 Amanda Carlin, “The Courtroom as White Space: Racial Performance as Noncredibility,” UCLA Law Review 250, (2016): 4.

3 Jelani Cobb, “Rachel Jeantel on Trial,” New Yorker, June 27, 2013, https://www newyorker com/news/news-desk/rachel-jeantel-on-trial

4 Alexander Abad-Santos, “My Star Witness Is Black: Rachel Jeantel's Testimony Makes Trayvon a Show Trial,” The Atlantic, June 27, 2013, https://www theatlantic com/national/archive/2013/06/rachel-jeantel-testimony-trayvon-martin-trial/31379 2/.

as immoral, childlike, and unworthy of respect and protection.” According to Higginbotham, 5 the politics of respectability require “reform of individual behavior as a goal in itself and as a strategy for reform.” In 2003, Paisley Harris, a Black female scholar for Johns Hopkins 6 University, added nuance to the concept: “respectability politics had two audiences: African Americans, who were encouraged to be respectable, and white people, who needed to be shown that African Americans could be respectable.” If I were to synthesize all that I’ve read about 7 the concept and define it as it stands now for Black women, I’d say that respectability politics is when, as their sole means of social mobility, Black women are forced to pander to respectability and in that process reject their cultural practices or anything associated with Blackness, since their identity as Black women has been denigrated by society To provide context, I will speak specifically about respectability manifestations in hair, attitude, and language.

For Black women, hair is everything: “Identity is inextricably linked to their relationship to and presentation of their hair.” If you ask a Black woman about her hair, there is no way that 8 the conversation won’t turn personal; hair is part of the Black female identity But the act of wearing her hair natural, for a Black woman, is much more societally charged than for women of other races. For instance, a young Black girl was once disciplined at school for “breaking the dress code,” since she had worn braids, a Black hairstyle, to school. To exemplify this 9 phenomenon, a study conducted by psychologists at Princeton University found that “African American women wearing natural hairstyles are explicitly [seen] as less competent than African American women wearing Eurocentric hairstyles.” In other words, in order to garner bare 10

5 Evelyn, Higginbotham Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880–1920 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993), Chapter 1

6 Higginbotham, Evelyn, Righteous Discontent, Chapter 1

7 Paisley Harris, “Gatekeeping and Remaking: The Politics of Respectability in African American Women’s History and Black Feminism,” Johns Hopkins University Press 15, no. 1 (Spring 2003): 3.

8 Tabora Johnson and Teiahsha Bankhead, “Hair It Is: Examining the Experiences of Black Women with Natural Hair,” Open Journal of Social Sciences 2, (2014): 1

9 Rosenblatt, Kalhan, “Louisiana girl sent home from school over braided hair extensions,” NBC News, August 22, 2018, https://www nbcnews com/news/nbcblk/louisiana-girl-sent-home-school-over-braided-hair-extensions-n902811

10 Aladesuru et al, “To Treat or Not to Treat: The Impact of Hairstyle on Implicit and Explicit Perceptions of African American Women’s Competence,” Open Journal of Social Sciences 8, Vol. 10 (October 2020): 10,

minimum levels of respect, Black women are expected to hide their natural hair

Hair is not the only thing that Black women must police, however, which brings me to attitude. In her renowned piece, “When White Women Cry,” Dr. Mamta Accapadi describes women of color as “fish that must swim upstream.” She argues that women of color are 11 oppressed from multiple directions, causing them to have to work harder to police their attitude, particularly when compared to white women. Black women who are not completely devoid of any “attitude” are stereotyped using prominent stereotypes of Black women’s character, such as the infamous Angry Black Woman stereotype. In summary, Black women who do not behave 12 absolutely perfectly by white patriarchal standards are quickly stereotyped based on their race and gender. Where white women are given the room in society to make mistakes, a Black woman cannot step a toe out of line without being made into an example or caricature of everything perceived as ‘wrong’ with Blackness.

Also victim to respectability judgments is Black women’s language use. A large part of Black culture is the use of AAVE, a dialect of English that follows its own—valid and grammatical—syntactic rules, but is often treated as inferior in modern society For instance, 13 you may have heard of the ‘achievement gap,’ often touted as existing between white and Black students, where Black students are found to perform worse academically than white students.14 In fact, much of the reason for the ‘achievement gap’ is that teachers in American schools

4236/jss.2020.810002. For reference, natural hairstyles may include a Black woman’s natural curls or a protective style, like braids To achieve a Eurocentric hairstyle, a Black woman must braid her hair or wear a wig

11 Mamta Accapadi, “When White Women Cry: How White Women's Tears Oppress Women of Color,” College Student Affairs Journal 26, no 2 (2007): 1

12 Some other popular stereotypes of Black women include the Mammy, the Sapphire, and the Jezebel, to name a few. To learn more on this, I recommend reading Woodward and Mastin’s “Black Womanhood: Essence and its Treatment of Stereotypical Images of Black Women.”

13 AAVE developed because of antebellum-era anti-literacy laws that prevented Black people from learning “standard English” grammar For more on this, I’d recommend Gelsey Beaubrun’s “Talking Black: Destigmatizing Black English And Funding Bi-Dialectal Education Programs ”

14 Carrie Spector, “Racial disparities in school discipline are linked to the achievement gap between Black and white students nationwide, according to Stanford-led study,” https://ed.stanford.edu/news/racial-disparities-school-discipline-are-linked-achievement-gap-between-black-and-whi te.

punish Black students for how they communicate: AAVE is often used among Black kids, but teachers in schools whose curriculums are based on whiteness will mark down or even refuse to teach AAVE-speaking kids due to their bias against it. AAVE is no less a language than the 15 mythic “Standard American English”—which is simply upper class, white English—but the way it’s treated when used in academic or professional settings leads many to believe it is.16 Most importantly, the dialect is staunchly a part of Black culture and is something that would be incredibly difficult for many Black people to simply not use, much like their natural hair or authentic attitudes.

In order for the courtroom to ostracize Blackness, whiteness first had to be established as a baseline. In her article on exclusion in the courtroom, legal scholar at UCLA Amanda Carlin establishes that the courtroom was, at its inception, an exclusionary white male space (the very opposite of a space made for Black women). As a result of courtroom practice in America being founded solely by white people and therefore on exclusively white behavior, “truth developed as distinctly white, as only white people ever spoke legal truths.” In other words, everyone in the 17 courtroom, a center for truth in the pursuit of justice, established white-coded behavior as the only way to express legal truth. This whitewashing developed passively, but that does not change the fact that a problematic status quo evolved. People of color were eventually permitted to provide testimony in a courtroom, almost a century later, with the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which granted citizenship to anyone born in the United States “without distinction of race or color, or previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude.” However, this 18 change did not mean that people of color were readily welcomed into the courtroom. When witnesses of color entered the court to take the stand, they entered a space that was entirely built in opposition to their being. When they entered this space of such opposition, where they

15 Gelsey G Beaubrun, “Talking Black: Destigmatizing Black English And Funding Bi-Dialectal Education Programs,” Columbia Journal of Race and Law, (July 15, 2020): 4.

16 Laura Greenfield, Writing Centers and the New Racism, (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2011), “The ‘Standard English’ Fairytale,” 2

17 Carlin, “The Courtroom as White Space” 4

18 Ballotpedia “Civil Rights Act of 1866,” https://ballotpedia.org/Civil Rights Act of 1866#:~:text=The%20Civil%20Rights%20Act%20of,United%20Stat es%20 Congress%20and%20the.

couldn’t help but stand out, this racial difference impacted testimonies of all races, not only contributing positively to perception of white testimonies, making them “legally unassailable,”19 but also generally shooting down the credibility of non-white testimonies. When humans make decisions of uncertainty, as when members of a jury must decide whether to interpret a witness testimony as truthful, we fill certain gaps in immediate clarity by relying on what we know, in other words, what is in our subconscious. Accordingly, in an environment where something is 20 intrinsically marked as different or as not belonging, one will become even more uncertain, and their evaluation of its truth will lean away from that thing. The courtroom as a white space 21 encourages implicit bias that arises from basic human processes to begin the systemic discrediting of people of color ’s witness testimonies.

The courtroom as an anti-Black space continues this process of systemic discrediting. It not only uplifts whiteness, but also, in turn, rejects Blackness. When Black people step into the courtroom, they are stepping into a place that is not built for them— they will never benefit from the privilege of invisibility, from knowing that their race will never be a negative factor in their perception. A major way in which Blackness is shot down in the courtroom is through the phenomenon of “Blackness as character evidence,” described by scholar Mikah K. Thompson. Implicit bias against Black people has created a widespread societal belief that Black people are, among other things, “inherently violent.” This belief is hard—if not impossible—to avoid, as it 22 permeates all levels of social exposure. The community least likely to hold this belief is Black people, since they can refer to their lived reality to rebut it. Since most juries are majority white and thus more likely to hold implicit bias against Black people, the majority of jurors will enter the courtroom harboring these beliefs. The court exacerbates this problem in an unexpected 23

19 Carlin, “The Courtroom as White Space,” 4

20 Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, “Judgment Under Certainty,” Science 185, no 4157 (September 27, 1974): 3

21 Joseph W Rand, “The Demeanor Gap: Race, Lie Detection, and the Jury,” Connecticut Law Review 33, no 12 (2000), 11.

22 Richard R Banks, “Discrimination and Implicit Bias in a Racially Unequal Society,” California Law Review 94, no. 4 ( July 2006): 5. Further context for this finding: in the words of Mikah K. Thompson in “Blackness as Character Evidence,” there is an “institutionalized narrative in our society that Blacks are intellectually inferior to Whites, inherently violent, and more likely to commit crimes than Whites ”

23 Dora Mekouar, “Why a Jury’s Racial Composition Matters,” VOA News, April 21, 2021, https://www voanews com/a/usa all-about-america why-jurys-racial-composition-matters/6204882 html#:~:text= He%20 found%20that%20diverse%20juries,longer%20than%20all%2Dwhite%20juries. (If you are looking for more information on how this phenomenon has taken shape in America, I very much recommend reading this

way Beliefs of inherent Black violence (and thus, criminality) are not talked about or addressed in the courtroom, since racism is rarely, if ever, used as a means of arguing a case, but these 24 beliefs are instead reinforced by playing into implicit bias. By keeping the preconceived notions implicit, the manifestations of these biases are used to sway court verdicts in favor of whites. Blackness is used as character evidence in the courtroom in that lawyers will play into proven stereotypes about Black people to make them seem more guilty, or, in turn, to make whites seem less guilty. In not using racism as concrete evidence but allowing lawyers to play into 25 stereotypes of a Black person’s race as character evidence, Blackness is further discredited in the courtroom.

Another way in which the racial coding of the courtroom becomes very apparent is language. Witness testimonies are given verbally, so language becomes the main universal indicator of witness credibility, and, as we know, language is often a way through which Blackness is separated from whiteness (recall: AAVE). In the words of Amanda Carlin, “underlying notions of powerful and powerless speech is the tradition of whiteness in the courtroom.” The norm for language in the courtroom is that spoken by white men.

26

Accordingly, a study on racial language bias against witnesses conducted by Lara Frumpkin found that “higher-status accents were rated more favorably than lower-status accents in black eyewitnesses,” causing them to view defendants as consequently more guilty. Further, a study 27 by Kurinec and Weaver found that “jurors found defendant[s] who used AAVE less professional and less educated.” This juror perception of defendants logically implies the application of this 28 belief to anyone speaking AAVE in the courtroom, like a witness. Devaluation of a witness, viewing them as unprofessional and uneducated due to their vernacular choices, would lead to

24 Mikah K Thompson, “Blackness as Character Evidence,” Michigan Journal of Race and Law 321, no 20 (2015): 14 article )

25 For those who are curious, an example of this phenomenon occurred in the trial of the officer who shot young Black man Ahmad Arbery to death. The officer had confederate flag memorabilia in his truck, but that was never mentioned as a possible motive for the murder. Rather, the trial was spent trying to prove that Arbery seemed violent For more, visit The Guardian’s “Ahmaud Arbery murder: trial laid bare America’s faultlines on race ”

26 Carlin, “The Courtroom as White Space,” 21

27 Anna Stone and Lara A Frumkin, “Not all eyewitnesses are equal: Accent status, race and age interact to influence evaluations of testimony,” Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice 18, no 2 (February 6, 2020): 2

28 Charles A. Weaver III and Courtney A. Kurinec, “Dialect on trial: use of African American Vernacular English influences juror appraisals,” Psychology, Crime & Law 25, no. 8 (2019), 18.

One might argue that AAVE is merely incomprehensible for non-Black witnesses, but “policing language is more about race and class than it is about communicative ability.” AAVE 29 is a mutually intelligible dialect to a speaker of any kind of English; the difference it carries is merely in the widespread implicit racial bias it carries. Further, it has been proven that the discrediting of AAVE in the courtroom does not come from concern about legibility but rather concern about witness demographics, particularly since, as Frumkin found, jurors tended to view AAVE speakers as less educated. Rachel Jeantel’s treatment by the jury provides an example: the grammar that Jeantel used was referred to as “subpar,” and juror B37 from the trial was interviewed and said that Jeantel was hard to understand and that “she did not think that Ms. Jeantel made a good witness because of some of the language that Ms. Jeantel used.” Notably, 30 though, no juror asked for a transcript of Jeantel’s witness testimony, even when it was completely available to them, which is just further proof of the fact that complaints lodged 31 against Black language in the courtroom take issue solely with the fact that the language comes from Black people. For those with this linguistic bias, the issue with the use of AAVE is not that it inhibits the expression of truth; it is that AAVE allows for the expression of Blackness in a space where it is traditionally unwelcome.

Until now, I have only addressed how the courtroom makes itself a hostile space to the performance of Blackness in general, but where does Black womanhood come in? For everything aforementioned, Black women are the most acutely affected and burdened by it. If the courtroom is established as a safe space for white men, the person who is, resultantly, least welcome there is the Black woman, and that is because Black women must not only navigate the obstacle course of anti-Blackness in the courtroom, but also misogyny Ultimately, “the intersectional experiences of women of color place them at the bottom of the credibility hierarchy, as they are refused both the privilege of whiteness and the privilege of maleness.”32

29 Carlin, “The Courtroom as White Space,” 26

30 Montre D Carodine, “Contemporary Issues in Critical Race Theory: The Implications of Race as Character Evidence in Recent High-Profile Cases,” The University of Pittsburgh Law Review 75, no 4 (2015): 11

31 John Rickford, Variation, Versatility and Change in Sociolinguistics and Creole Studies, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), Chapter 12.

32 Carlin, “The Courtroom as White Space,” 28.

Women, as linguist Robin Lakoff argues in “Language and Woman’s Place,” are expected to demur in their speech; one would imagine that this occurs greatly in formal settings like that of a courtroom. Contrastingly, if a woman takes the witness stand and uses the subservient 33 language and attitude Lakoff argues that society so regularly requires of women, that damages her credibility as a witness; she seems unsure.

So what if a woman does what Jeantel did, and refuses to portray herself as lesser than, and does not shy away from combat, ‘like a man’? Then the arsenal of name-calling and respectability comes out: the Angry Black Woman trope gets thrown around like a grenade. 34 Jeantel was viciously attacked for her “difficult” persona. As Accapadi lays out in her piece on respectability, there is no successful persona for a woman of color to employ, but when she stands up for herself in any way, the vitriol that emerges is overwhelming. Being perceived as angry results in the dismissal of women of color, and their expected submission and silence when trying to avoid being stereotyped does nothing to help them advocate for themselves, either, something made apparent in the courtroom. Further, with regard to gender, the 35 allegations lodged against Jeantel by the attorneys in their attempts to discredit her were distinctly gendered: for a significant portion of her cross-examination, Jeantel was interrogated by a prosecutor about whether she was Trayvon Martin’s girlfriend and about the details of her sex life, something which never would have come up had Jeantel been a man. Even after the trial, Jeantel was given a very public “makeover” to fix some of what society had so hated about her: her hair, her weight, her clothes. It is hard to imagine that anything similar would ever 36 happen to a man after a witness testimony It is apparent, then, that Black women who take the stand are facing overlapping forces of opposition to both their race and their gender. When we examine what happens to a Black woman who takes the witness stand in terms of the hostility built up against her, it is no wonder that she might feel forced to employ respectability politics. If the courtroom so clearly privileges whiteness and denigrates

33 Robin Lakoff, “Language and Woman’s Place,” (Stanford: Stanford University, 1972), 6

34 Melissa V Harris-Perry, “Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America,” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 25

35 Accapadi, “When White Women Cry,” 6

36 TheGrio, “Rachel Jeantel Gets Makeover Compliments Of Ebony Magazine,” Huf ington Post, November 19, 2013), https://www.huffpost.com/entry/rachel-jeantel-makeover-ebony-thegrio n 4303277.

Blackness, that is a phenomenon that asks, or rather, virtually requires a Black witness to perform whiteness to gain credibility. Respectability politics never arises without reason; it has always been employed out of necessity, and the courtroom is no exception. That being said, how is a Black female witness supposed to know about this expectation with which she must comply in order to be taken seriously? The oath she will take, promising only to be truthful, says absolutely nothing about that. Jeantel came to the witness stand, angry, grieving the murder of her friend, and profoundly Black; in other words, she came as herself. She was torn to shreds as a result. For the sake of credibility, she would have had to completely change her being (without ever directly being told to do so) to be respected, to be listened to. What are Black women supposed to do, then, when these rules at play are implicit, and the stakes are so high in both scenarios—either sacrificing justice in the courtroom, or sacrificing justice to herself? If she employs respectability politics, she must reject her very being; if she does not, justice may not be served. Ultimately, it seems that either way, an injustice will occur.

Many would be left wondering, after learning of the outlandish unwritten expectations for witnesses, what’s the solution here? Several companies have argued that the easy solution is training witnesses to properly comport themselves on the stand. If there are these standards that witnesses have to adhere to to earn credibility, why not train them to meet them? Companies like SEAK, the “Expert Witness Training Company,” exist for this very reason. One paper on the 37 implicit bias witnesses face even makes the point that “attorneys may want to consider… whether to put the [Black] witness on the stand or not.” Although the intentions of SEAK are 38 admirable, many others, including myself, would argue that training or hiding is not the solution. To train Black women for “successful” witness testimonies or to not allow them to testify at all would be akin to allowing the masked racism inherent in respectability politics to continue to pervade society. As an article in the Journal of Hip-Hop Studies argues, “respectability politics places Black people in a box, with those who are operating within the confines of those ideologies inside, and those who do not conform to normative expectations on the outside of the

37 SEAK: The Expert Witness Training Company, https://www.testifyingtraining.com/.

38 Frumkin and Stone, “Not all eyewitnesses are equal,” 27.

box.” Black women everywhere are fighting against this box, but this fight should not be

39 fought by them alone. Further, in the words of sociologist Tressie McMillan Cottom, “the social norms around respectability that we black people use . . . do the dominant culture’s work of disciplining other black people’s identities, behaviors, and bodies.” Cottom also argues that 40 there’s no guarantee or real win when it comes to the “crapshoot” of respectability politics; it 41 will always be a way to keep the dominant culture dominant and to keep everyone else subservient, struggling to reach the top. Appropriately, the website “Therapy for Black Girls” reminds us that “the problem with respectability politics is that it doesn’t work. It places the responsibility and blame on the victim instead of the systems that uphold it.” We shouldn’t 42 blame Black women for desiring upward mobility, but we should still strive to take away the sentiment that they need it, or that they need to employ respectability politics to achieve it.

So, what should we do? Or, what can you do? The first step is to identify and evaluate your implicit racial biases. If you find yourself holding someone to a standard that realistically shouldn’t be applied to them, judging or denigrating someone just for embodying their own identity, stop yourself, and try to set your mind on a different path. Then try to continuously correct that judgemental mental pattern. I hope that this research has not only informed you of a problem of which you may not have been aware, but also taught you ways to identify when it is being perpetuated. I implore you to use them.

Further, when it comes to the courtroom, employ special caution. It is more likely than not that we will all find ourselves reporting for jury selection in the near future, and if you are chosen, that is a burden. The judicial system is an integral part of our society, but it is also always resting on some very shaky integrity. This is your chance to do your part to weave justice back into that system. If you are ever feeling doubtful about that integrity, and about one’s responsibility in upholding it, I hope the chance to do good here offers consolation.

39 Ashley Payne, “The Cardi B–Beyoncé Complex: Ratchet Respectability and Black Adolescent Girlhood,” (Journal of Hip-Hop Studies 7, no. 1 (2020): 9.

40 Tressie McMillan Cottom, THICK: And Other Essays, (New York City: The New Press, 2019), 69

41 Tressie McMillan Cottom, THICK: And Other Essays, 167

42 Jordan Madison, “The Skin I’m In: Respectability Politics in the Context of Black Womanhood,” Therapy for Black Girls, July 1, 2021, https://therapyforblackgirls com/2021/07/01/the-skin-im-in-respectability-politics-in-the-context-of-black-womanho od/.

Instead of expecting Black women to mold themselves into whiteness, embrace them as they are; accept them as they come. I am sure you would hope, and maybe even expect, that they would do the same for you.

Throughout this essay, I have unraveled how powerful implicit bias can be, which ultimately manifests in grave and tangible real-world consequences. We’ve seen how implicit bias against Black womanhood, coupled with the construction of the American judicial system, causes Black women witnesses to have to employ respectability politics for the sake of credibility The guiding case study in this essay was Rachel Jeantel, who went from a grief stricken 19-year-old girl to “everything wrong with [an entire] race” in a matter of hours due to 43 her refusal to employ respectability politics. Instead, the useful ways in which Jeantel was able to add clarity to the events of the case should have been highlighted, and her grief should have been respected. Most importantly, it is my hope that we have digested all the ways in which that is unfair and needs to be changed. And change it we can; it is, in fact, up to us to be the change.

Because yes, Black women take the witness stand promising to tell “the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth,” but the ability to freely live their truth should not be mutually 44 exclusive.

43 Meraji, Shereen “What [BLANK] Folks Don't Understand About Rachel Jeantel,” NPR, June 29, 2013, https://www npr org/sections/codeswitch/2013/06/29/196709577/what-blank-folks-dont-understand-about-rachel-jea ntel.

44 Witness Oath - ADR, https://www.adr.org/sites/default/files/document repository/Witness Oath.pdf.

Works Cited

Abad-Santos, Alexander “My Star Witness Is Black: Rachel Jeantel's Testimony Makes Trayvon a Show Trial.” The Atlantic, May 12, 2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2013/06/rachel-jeantel-testimony-trayvonmarti n-trial/313792/.

Accapadi, Mamta Motwani. “When White Women Cry: How White Women's Tears Oppress Women of Color.” College Student Affairs Journal 26, no. 2 (2007): 1-6. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ899418.pdf.

Aladesuru, Boluwatife H, Debby Cheng, Dana L. Harris, Arielle Mindel, and Madalina Vlasceanu. “To Treat or Not to Treat: The Impact of Hairstyle on Implicit and Explicit Perceptions of African American Women’s Competence.” Open Journal of Social Sciences 8, Vol. 10 (October 2020): 10. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/e5cfn.

Allen, Melissa V Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

American Psychological Association. "Implicit Bias." APA Topics. https://www.apa.org/topics/implicit-bias

Banks, R. Richard, Jennifer L. Eberhardt, and Lee Ross. “Discrimination and Implicit Bias in a Racially Unequal Society.” California Law Review 94, no. 4 (2006): 1169–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/20439061.

Beaubrun, Gelsey G. “Talking Black: Destigmatizing Black English and Funding Bi-Dialectal Education Programs.” Columbia Journal of Race and Law 10, no. 2 (June 2020). https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/d8-m5tj-dx94.

Carodine, Montré D. “Contemporary Issues in Critical Race Theory: The Implications of Race as Character Evidence in Recent High-Profile Cases.” University of Pittsburgh Law Review 75, no. 4 (2015): 11. https://doi.org/10.5195/lawreview.2014.343.

“Civil Rights Act of 1866.” Ballotpedia, https://ballotpedia.org/Civil_Rights_Act_of_1866.

Cobb, Jelani. “Rachel Jeantel on Trial.” The New Yorker, June 27, 2013, https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/rachel-jeantel-on-trial.

Cottom, Tressie McMillan. “In The Name of Beauty.” Thick: And Other Essays. New York: The New Press, 2019.

Frumkin, Lara A., and Anna Stone. “Not All Eyewitnesses Are Equal: Accent Status, Race and Age Interact to Influence Evaluations of Testimony.” Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice 18, no. 2 (2020): 123-145.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15377938.2020.1727806.

Greenfield, Laura. The “Standard English” Fairy Tale: A Rhetorical Analysis of Racist Pedagogies and Commonplace Assumptions about Language Diversity. Logan: Utah State University Press, 2011.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291978379_The_Standard_English_fairy_tale_ A_rh etorical_analysis_of_racist_pedagogies_and_commonplace_assumptions_about_languag e_di versity.

Harris, Paisley Jane. “Gatekeeping and Remaking: The Politics of Respectability in African American Women's History and Black Feminism.” Journal of Women's History 15, no. 1 (2003): 212-220. https://doi.org/10.1353/jowh.2003.0025.

Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks. Righteous Discontent: The Women's Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880-1920. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Johnson, Tabora A., and Teiahsha Bankhead. “Hair It Is: Examining the Experiences of Black Women with Natural Hair.” Open Journal of Social Sciences 2, no. 01 (2014): 86-100. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2014.21010.

Kurinec, Courtney A., and Charles A. Weaver. “Dialect on Trial: Use of African American Vernacular English Influences Juror Appraisals.” Psychology, Crime & Law 25, no. 8 (2019): 803-828. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316x.2019.1597086.

Lakoff, Robin. “Language and Woman's Place: Language in Society.” Stanford: Stanford University, 1972. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/language-in-society/article/language-and-wom ans-pl ace/F66DB3D1BB878CDD68B9A79A25B67DE6.

Laughland, Oliver. “Ahmaud Arbery Murder: Trial Laid Bare America's Faultlines on Race.” The Guardian, November 25, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/nov/25/ahmaud-arbery-verdict-race.

“Louisiana Girl Sent Home from School over Braided Hair Extensions.” NBCNews.com, August 22, 2018. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/louisiana-girl-sent-home-school-over-braided-h air-ex tensions-n902811.

Madison, Jordan. “The Skin I’m In: Respectability Politics in the Context of Black Womanhood.” Therapy for Black Girls, July 1, 2021, https://therapyforblackgirls.com/2021/07/01/the-skin-im-in-respectability-politics-in-the -cont ext-of-black-womanhood/.

Mekouar, Dora. “Why a Jury’s Racial Composition Matters.” VOA News, April 22, 2021.

https://www.voanews.com/a/usa_all-about-america_why-jurys-racial-composition-matte rs/62 04882.html.

Meraji, Shereen Marisol. “What [Blank] Folks Don't Understand about Rachel Jeantel.” NPR, June 29, 2013.

https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2013/06/29/196709577/what-blank-folks-dontunderstand-about-rachel-jeantel.

Payne, Ashley N. “The Cardi B–Beyoncé Complex: Ratchet Respectability and Black Adolescent Girlhood.” Journal of Hip Hop Studies 7, no. 1 (2020): 26-43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.34718/pxew-7785.

Rand, Joseph W. “The Demeanor Gap: Race, Lie Detection, and the Jury.” Connecticut Law Review 33, no. 1 (Fall 2000). HeinOnline: https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/conlr33&i=11.

Rickford, John R., and Gillian Sankoff. “ Chapter 12 - Language and Linguistics on Trial.” Variation, Versatility and Change in Sociolinguistics and Creole Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Spector, Carrie. Stanford Graduate School of Education. "Racial Disparities in School Discipline Linked to Achievement Gap Between Black and White Students." Stanford Graduate School of Education News.

https://ed.stanford.edu/news/racial-disparities-school-discipline-are-linked-achievementgap-between-black-and-white.

TheGrio. “Rachel Jeantel Doesn't Look like This Anymore.” HuffPost, November 20, 2013.

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/rachel-jeantel-makeover-ebony-thegrio_n_ 4303277.

Thompson, Mikah K. “Blackness as Character Evidence.” Michigan Journal of Race & Law 321, no. 20 (March 1 2015). https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/mjrl20& i=331.

Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman. “Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases.” Science 185, no. 4157 (1974): 1124-1131. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4157.1124.

Witness Oath - ADR. https://www.adr.org/sites/default/files/document_repository/Witness_Oath.pdf.

Woodard, Jennifer Bailey, and Teresa Mastin. “Black Womanhood: Essence and Its Treatment of Stereotypical Images of Black Women.” Journal of Black Studies 36, no. 2 (2005): 264-281. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934704273152.

Landon Miller | Stanford University

Winter 2024

Mississippi has the highest incarceration rate in the nation, imprisoning 584 per 100,000 residents. Comparatively, the rest of the nation has an average incarceration rate of 358 per 100,000 residents. Inhumane prison conditions and absurdly delayed trial dates are cause 1 2 enough for profound scrutinization of the civil rights granted to the citizens of Mississippi, and yet the implications of incarceration do not end after the completion of a citizen’s sentence. Per the 1890 Mississippi state constitution, convicted felons are barred from ever voting in federal, statewide, and local elections. Article XII Section 241 of the Mississippi state constitution currently disenfranchises over 200,000 people and over 16% of the African American electorate3 in the Magnolia State, where the last gubernatorial election was decided by a margin of 26,619 votes.4

Furthermore, the abject racism of the 1890 constitution and the disproportionate rate at which African American Mississippians are charged and convicted of felonies has put the statute under great scrutiny under various constitutional provisions, including the Eighth Amendment protection against cruel and unusual punishment and the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause. In 2017, the Southern Poverty Law Center raised these objections and sued the Mississippi Secretary of State’s office on behalf of disenfranchised citizens in Hopkins v Hosemann. As of November 2023, the plaintiffs await a ruling from the Fifth Circuit’s en banc hearing where all judges on the circuit court will decide the case by a majority vote after the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled § 241 unconstitutional. A similar disenfranchisement statute in Alabama was struck down in Hunter v. Underwood (1985) under the Fourteenth Amendment, yet the Fifth Circuit has failed to apply the same precedent to Hopkins Thus, the plaintiffs’ argument now rests upon the Eighth Amendment protection against cruel and unusual punishment.

This article will examine the history of voting rights in Mississippi, tracing the expansion

1 Carson, “Prisoners in 2021 - Statistical Tables ”

2 Mitchell, “Conditions at Mississippi’s Most Notorious Prison Violate the Constitution, DOJ Says ”

3 Mississippi NAACP, “Felony Disenfranchisment in Mississippi.”

4 Times, “Mississippi Governor Election Results 2023.”

of voting rights in Mississippi from the Reconstruction amendments to the Voting Rights Act. It follows from the discriminatory history of the 1890 constitution that § 241 should be challenged on Fourteenth Amendment grounds; however, due to the rulings in Cotton v Fordice and Harness v Watson, the court will not hear such challenges. I will analyze the validity of the arguments in Cotton and Fordice, finding them both erroneously decided, before providing my own argument that § 241 undoubtedly violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment in accordance with the precedent set by Hunter v. Underwood. Nonetheless, since the Fifth Circuit cannot overrule the Supreme Court’s ruling in Cotton, the plaintiffs in Hopkins now depend on a novel Eighth Amendment challenge, a weaker yet still viable claim. I will conclude by illustrating what the next courses of action might be for proponents of voting rights in Mississippi should Hopkins be thrown out by the Fifth Circuit or Supreme Court.

A. Reconstruction Amendments and “Redeemers”

After defeating the southern states in the Civil War, the Republican-controlled federal government occupied and directly administrated the southern states and passed sweeping reforms, including civil rights and voting rights legislation for newly freed African Americans. Following the passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, African American men in the South experienced previously unimaginable equality in the political sphere. Under the federal administration of Mississippi, African American men in Mississippi enjoyed equal protection under the law and the right to vote and hold office in the state that just 20 years prior denied their humanity. African Americans, who made up a majority of Mississippi’s population, were elected to every federal and statewide office. Mississippi 5 elected the first and second African American U.S. Senators, Hiram R. Revels and Blanche K. Bruce. In compliance with federal demands, Mississippi adopted a new, federally pre-cleared 6 constitution in 1869 and was readmitted to the union in 1870.

5 U.S. Census Bureau, 1870 Aggregate Population with Race, State of Mississippi

The Republican government that led the Reconstruction era remained dominant in the state for a short time, until white conservatives executed the first step of a grand scheme to 6 Miss. Department of Archives and History, “The First Black Legislators in Mississippi.”

regain control of the political system. These so-called “Redeemers” who sought to redeem their idealized Southern social order of white supremacy were enraged by the ascension of African Americans in the political and social spheres. They began plotting a strategy for reestablishing white supremacy in law as soon as federal administration of the state ended. In the late 1870s white conservatives executed the first step of the “Mississippi Plan,” a coordinated effort to end African American political participation and codify white supremacy in law By intimidating African American voters and blatantly committing election fraud, white 7 8 conservatives regained control of the state legislature, and by 1876, they impeached the sitting Republican governor and lieutenant governor.9

B. The 1890 Mississippi Constitutional Convention and § 241

After regaining control of the state government, conservatives in Mississippi wasted little time before convening a constitutional convention to restructure the state government fundamentally The express and undeniable goal of the convention, according to its participants, was to reestablish the antebellum state of race relations. Delegate George P. Melchior of Bolivar County said, “It is the manifest intention of this Convention to secure to the State of Mississippi, ‘white supremacy.’” The president of the convention, Judge Solomon Saladin Calhoon of Hinds 10 County addressed the assembly thus: “Let’s tell the truth if it bursts the bottom of the Universe. . . We came here to exclude the Negro. Nothing short of this. . . . Negro suffrage is an evil.”11

There is no doubt that the contemporaries of the 1890 constitution were determined to relegate African Americans to their former state of oppression through whatever legal means were available.

The 1890 constitution included infamous provisions such as the poll tax, literacy tests, and a kind of electoral college for statewide elections that ensured African Americans could never elect leaders, even with an outright majority Among these provisions is § 241, the lifetime disenfranchisement of citizens convicted of felonies, which states:

7 Miss Department of Archives and History, “The Clinton Riot of 1875”

8 Equal Justice Initiative “Reconstructions’s End,” 89

9 Miss Department of Archives and History, “Adelbert Ames”

10 Martin, Journal of the Proceedings, 275.

11 Miss. Department of Archives and History, “Isaiah T. Montgomery, 1847-1924 (Part II) - 2007-02.”

Every inhabitant of this state, except idiots and insane persons, who is a citizen of the United States of America, eighteen (18) years old and upward, who has been a resident of this state for one (1) year, and for one (1) year in the county in which he offers to vote, and for six (6) months in the election precinct or in the incorporated city or town in which he offers to vote, and who is duly registered as provided in this article, and who has never been convicted of murder, rape, bribery, theft, arson, obtaining money or goods under false pretense, perjury, forgery, embezzlement or bigamy, is declared to be a qualified elector 12

The federal government, weary after years of Reconstruction and now dependent on votes from Southern states’ representatives, had no desire to intervene in Southern states to enforce racial equality. In Williams v. Mississippi (1898), the Supreme Court upheld the discriminatory voting provisions in the 1890 Mississippi constitution, saying that the provisions had no explicitly discriminatory language. There was no consideration of the fact that there was overt discriminatory intent in creating the law, and the operating principle was merely to call overt discrimination in voting laws unconstitutional. As a result, African Americans were disenfranchised en masse, as the laws were unequally applied to African American and white citizens. While the former were expected to produce entire sections of the state constitution to county registrars, the latter could get away with writing mere sentences or even just their names. In 1964, immediately before the Voting Rights Act banned most disenfranchisement provisions of the 1890 constitution, African American voter registration was abysmal, at 6.7 percent.13

These discriminatory voting laws remained in place until the Civil Rights era in the 1960s, after widespread organization and protests by African Americans in the South and sympathetic Northerners. The ratification of the Twenty-Fourth Amendment rendered poll taxes unconstitutional, immediately striking down such provisions in several southern states. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, an “act to enforce the fifteenth amendment to the Constitution,” outlawed literacy tests and provided federal oversight of elections in places with prevalent racial

12 Miss, Const art XII, § 241

13 U.S Commission on Civil Rights, “The Mississippi Delta Report,” Ch. 3

discrimination like Mississippi. It also included a provision that such states with a history of discriminatory voting laws and practices had to receive pre-clearance from the Department of Justice for any legislation concerning voting. As a result of the Voting Rights Act, African Americans across the South were guaranteed their voting rights for the first time since Reconstruction, and African American voter participation skyrocketed.14

Past Fourteenth Amendment Challenges to Felony Disenfranchisement A. Hunter v. Underwood (1985)

Despite the dramatic expansion of voting rights in the 1960s, no act of Congress explicitly outlawed criminal disenfranchisement provisions such as § 241 of the Mississippi state constitution. One such provision, § 182 of Alabama’s 1905 constitution, prevented plaintiffs Carmen Edwards, an African American, and Victor Underwood, a white man from voting after each man was charged for writing bad checks. After finishing their sentences, the men brought suit to the Alabama Board of Registrars, challenging the constitutionality of the provision under the Fourteenth Amendment on account of the racially discriminatory impact and intent of the provision.

In Hunter v Underwood, the Supreme Court ruled that laws with racially disparate outcomes that were written with discriminatory intent violate the Equal Protection Clause, even if the wording of the law itself is neutral. Hunter set an important precedent by which other 15 criminal disenfranchisement provisions also be examined, especially in Southern states, and several challenges to Mississippi’s voter disenfranchisement provision were argued along the same lines.

A. Cotton v. Fordice (1998)

In another suit brought against the governor of Mississippi, the plaintiffs in Cotton v. Fordice argued that § 241 violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment due to the racially discriminatory intent of the lawmakers at the time of passage in 1890. The Fifth Circuit then ruled that the updates to the law, in 1950 and 1968, removed the discriminatory taint of the law, thus differentiating this case from the precedent established in Hunter v 16

14 Times, “U S Negro Voters Put at 5 5 Million ”

15 Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S. 222 (1985)

16 Jarvious Cotton v. Kirk Fordice, 157 F.3d 388 (5th Cir. 1998)

Underwood The standard since Cotton has been that any subsequent amendment to a discriminatory statute must also have established discriminatory intent to violate the Fourteenth Amendment.

In August of 2023, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals refused to hear challenges to § 241 rooted in the Fourteenth Amendment, citing the precedent previously established by the Eleventh Circuit Court in Johnson v Governor of State of Florida (2005), that the “felon disenfranchisement provision did not violate the Equal Protection Clause because the current provision was adopted without discriminatory intent” In Johnson, the 1898 provision in 17 question had been amended by legislators in 1968, leaving the court to decide whether the precedent in Hunter was satisfied. Along those lines, the majority of the Fifth Circuit cited the fact that the state legislature amended § 241 in 1950 to remove “burglary” from the list of crimes that triggered disenfranchisement and in 1968 to add “rape and murder.” Thus, the discriminatory taint of the law was removed, rendering any Fourteenth Amendment challenge invalid.

The problem with the ruling in Cotton is the nature of the amendments, especially the most recent amendment, which in no way diminishes the effect of the statute as passed in 1890. I argue that the most reasonable standard for removing the discriminatory taint of a statute is that any amendment must amount to a fundamental change in the statute or a dramatic decrease in how restrictive the statute is. As it stands, there is a strict line of continuity between each version of § 241 that neither amendment fundamentally altered. Firstly, the 1950 amendment removing burglary from the list of offenses cannot amount to a fundamental change in the law since the general meaning and content of § 241 that most felonies will result in lifetime disenfranchisement was not changed. The well-established discriminatory intent of the 1890 delegates lives on in all of the other listed crimes that were left unchanged. Secondly, the fact that the legislature made the provision more restrictive in 1968 by including rape and murder makes the notion of § 241’s removal from discriminatory intent even more implausible. The conclusion that increasing the restrictiveness of a law first enacted as an overtly discriminatory measure could somehow wash away the discriminatory nature of the bill is absurd. Suppose that

17 Johnson v. Governor of State of Florida, 405 F.3d 1214 (11th Cir. 2005)

the Twenty-Fourth Amendment, banning poll taxes, was never enacted, and in 1968, the provision in Mississippi’s 1890 constitution for a $2.00 poll tax stood. By the precedent in Cotton, are we to say that the discriminatory intent of the poll tax could be washed away if the legislature in 1968 increased the poll tax to $4.00? Increasing the degree to which the law fulfills the intent of its discriminatory passage cannot wash away the intent. The only way to change such a statute per the Fourteenth Amendment is to fundamentally alter the restrictions of the law, and typically the best way to ameliorate the intent is to simply strike down the law. C. Harness v. Watson (2022)

In 2022, plaintiffs Roy Harness and Kamal Karriem, two Mississippi natives and convicted felons, brought suit against Mississippi Secretary of State Michael Watson in his official capacity. They sought injunctive relief to restore their voting rights as convicted felons, claiming § 241 violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause because the 1890 provision maintained its discriminatory intent despite subsequent amendments. The case was heard because the question was whether the 1968 amendment to § 241, adding rape and murder to the list of disqualifying crimes, was passed with discriminatory intent. The Fifth Circuit, in an en banc hearing, reaffirmed the ruling in Cotton, saying that the provision as it currently stood had been washed of its discriminatory taint, and since the plaintiffs were unable to establish discriminatory intent in the 1968 legislature’s passage of the amendment, the precedent was maintained. The following year, the Supreme Court declined to hear the case. 18

For the reasons above, I believe the standard in Cotton was asking the wrong question, and the court’s reaffirmation of the decision has led to Fourteenth Amendment challenges of § 241 being unreliable for plaintiffs. Harness also sets the troubling standard that any amendment to a law passed with discriminatory intent, however trivial, can remove the initial intent’s relevance in Fourteenth Amendment challenges. Such a standard puts civil rights casework generally into an awkward position, as many discriminatory provisions passed in the post-Reconstruction era have been amended at some point thereafter

18 Harness v. Watson, No. 19-60632 (5th Cir. 2022)

Having established why Cotton and Harness were decided poorly, we may now proceed to challenge § 241 on Fourteenth Amendment grounds. My argument is not a novel one, but rather it seeks to apply the standard the Court established in the 1985 case Hunter v. Underwood. Due to the similar nature of both cases, I argue that the standard applied in Hunter should also be applied to Hopkins.

In Hunter, the Court stated the need for evidence of both racially disparate outcomes and racially discriminatory intent in making the law. After both have been established, the burden shifts to the defendant to prove that the law would have been written otherwise if not for the racially discriminatory intent. By this standard, § 241 should also be ruled unconstitutional by the Equal Protection Clause. I will walk through each step of the Court’s standard, showing how the plaintiffs in Hunter met them and how the plaintiffs in Hopkins would meet them. Firstly, Mississippi’s § 241 and Alabama’s § 182 are exceedingly similar, both in that they are the only constitutional provisions in the country that explicitly list the crimes that disqualify citizens from voting and in their neutral wording. The list of offenses that prevent Mississippi citizens from voting is as follows: …and who has never been convicted of murder, rape, bribery, theft, arson, obtaining money or goods under false pretense, perjury, forgery, embezzlement or bigamy, is declared to be a qualified elector…19

The statute is generally taken to mean any felony conviction results in lifetime disqualification from voting. Similarly, Alabama’s § 182 disenfranchised: All idiots and insane persons; those who shall by reason of conviction of crime be disqualified from voting at the time of the ratification of this Constitution; those who shall be convicted of treason, murder, arson, embezzlement, malfeasance in office, larceny, receiving stolen property, obtaining property or money under false pretenses, perjury, subornation of perjury, robbery, assault with intent to rob, burglary, forgery, bribery, assault and battery on the wife,

19 Miss. Const. art. XII, § 241.

bigamy, living in adultery, sodomy, incest, rape, miscegenation, crime against nature, or any crime punishable by imprisonment in the penitentiary, or of any infamous crime or crime involving moral turpitude.20

Alabama’s statute is rather more restrictive specifically, the disqualifications of any person who commits a crime punishable by imprisonment or a crime involving moral turpitude, which, as one might expect, were very flexibly applied. Both statutes used racially neutral language, making them permissible under the Fifteenth Amendment at the time these constitutions were adopted.

Mississippi’s statute also meets the same standard of creating sufficiently disparate outcomes by race as Alabama’s statute. In oral arguments before the Court, the plaintiffs in Hunter cited one of the historians called as a witness:

In fact, the Defendants' own expert, the Appellants' own expert testified that 90 percent of the people who were disfranchised in the first year after the passage of the Constitution for commission of a misdemeanor were Black. African Americans were disenfranchised at such an 21 extreme proportion despite making up only 45% of the population of Alabama in 1900, clearly 22 showing disparate outcomes. Similarly, the impact of the Mississippi provision has led to demonstrably discriminatory outcomes. According to a petition filed by the Mississippi Center for Justice on behalf of the plaintiffs in Harness, “African American adults are … 2.7 times more likely than white adults to have been convicted of a disenfranchising crime.” The statute creates 23 extremely disparate outcomes in the present day, and it has historically been even more overwhelmingly discriminatory. Thus, the challenge of § 241 reaches the standard established by Hunter for discriminatory impact.

The plaintiffs in Hunter, further, had to establish discriminatory intent in the passage of the law to challenge it on Fourteenth Amendment grounds, and the evidence they used is near-identical to evidence used in other cases to prove discriminatory intent in the passage of § 241. They offered up the words of the presiding officer of the 1901 Alabama constitutional

20 Ala Const art VII, § 182