selected articles from back issues now available in audiomag format click here to HEAR the mag

selected articles from back issues now available in audiomag format click here to HEAR the mag

The evolution of a fly angler corresponds directly to the pace at which they fish. Eventually, the urges to simply catch a fish, catch a lot of fish, and catch a big fish give way to angling intention—the desire to fish on one’s own terms. How we want to fish is a clearly-defined approach years in the making, a synthesis of personal experience and preferences mixed with the tutelage of traditions, peers, and mentors. Casts are less frequent, but more meaningful—we see, hear, and —most importantly—feel more.

Pace is minimized but awareness is maximized, and observation becomes paramount. We spend days, sometimes weeks, in waiting for the hatch, anticipation steadily building. Finally, when patience has been adequately and thoroughly tested, a mayfly emerges. One cast is all it takes but that may also be all we get. Our fishing is inspired by time and place, and the places that inspire us tell us to take as much time as we can, to slow down. In doing so, we find there is always more to be observed, learned, and felt. Including that one, specific fish.

Presenting CLASSIC

98

Cola (Super Sleuth)

Sluicing

FALL 2025 issue no. 57

Managing editor

John Agricola

Editor at large

Michael Steinberg

Creative Director & Design Chief

Hank

Director of Advertising

Samuel Bailey

Merchandiser

Scott Stevenson

Media Director

Alan Broyhill

contributors:

Flip McCririck

Rob Benton

Poon Bishop

Tom Wetherington

Will Coker

Ben MacKinnon

Austin McDonald

Judson Vail

Brandon Brown

Kendall Mayers

Managing editor emeritus: David Grossman

Creative Director emeritus: Steven Seinberg

copy editor: Lindsey Grossman

ombudsman: Shad Maclean

general inquiries: southerncultureonthefly@gmail.com

advertising information: sam@southerncultureonthefly.com

cover image: Connor Koch by the Watertower; by hank

back cover image: Honky Tonk Angel, Austin McDonald

by

For over 80 years, we have been at the forefront of innovation. Sharpened by experience. Pushing the boundaries of material science to make our lines stronger and more durable. Then testing in the most demanding environments with the world’s best anglers. Those who demand the best choose Scientific Anglers.

Dear readers,

If Hunter S. Thompson had traded Aspen for Gadsden, Vegas for Bristol, and swapped mescaline for willowflies, this might’ve been the issue he wrote. Call it Southern fried journalism with a hangover and a hymn book. What you’re holding isn’t just a magazine— or a phone. It’s a field report from the mudline between memory and myth. The bourbon’s half gone. The starter solenoid’s busted. The story still runs.

These pieces don’t care for tidy endings. They ask what keeps us casting when the water turns against us— what makes a man chase belonging down a backroad with a new dog riding shotgun and significant ghosts crowding the rearview?

Autumn hits like feedback in an old amp. The light slants. The air bites. Rivers roll from heat into breath. This issue is that turnover—the in-between—where the South spray-paints its name on a water tower and dares it to fade.

Prodigal Clyde and Merla Haggard Goes to Carrabelle are road stories. A beat-up truck, an equally beat-up albeit rescued dog, and the long way home. Grace rides shotgun with Merla the barn dog. Gas fumes and faith run neck and neck.

Welcome to Southern Issue Number 57: The Water

Hold tight. Winter’s coming,

Rainbow City Auction and Fly Fishing, Frank the Ranger, and The Lord Giveth and the Lord Taketh Away dig into the marrow of small town generosity. A fly shop turns into a church. The tithe is time, advice, and the occasional TFO rod traded for a story worth retelling. Then there’s Blue Ridge. TVA opens the sluice gates and the water comes out toward death. The town that mix of engineering community isn’t a logo—it’s common current isn’t a mood; So what does it mean the living systems that hold Maybe it means tying better Carrying the weight without because the river’s gonna can do is meet it with a cast This issue is our hymn beauty—holy, profane, redemption. Whenever you contradiction, we at SCOF paradox.

out too warm. The trout edge town flinches. And somewhere in and emotion, we see it plain: logo—it’s a system of survival. The mood; it’s a mandate. mean to belong to a place when hold it together start to turn? better knots. Listening harder. without complaint. And laughing, gonna do what it does, and all we cast that matters. hymn to that strange Southern and one cast away from you find yourself in a seeming SCOF recommend embracing the Southern Culture on the Fly’s Fall Water Tower. coming, and this current is dropping.

by cola

Rust hums down the road— ghosts ride shotgun, grace in chrome, home is what won’t die.

Clyde leaks gas and faith, Broc prays, I gamble his pay— Lord, tow us home straight.

By John Agricola Jr.

Ihope to tell a story of Clyde, but more than likely it’s a story of myself, projected onto a 1974 Mercury Marquis known to many as The Drake Mobile.

The first time I ever rescued Clyde was under similar circumstances of distress. He’d been under the care of Dun Magazine editor and publisher Jen Ripple. The night before my father and I left under cover of darkness for Kentucky, we were watching football. When the late game ended, we loaded his 2001 Dodge Ram with a too-small trailer and a too-loose hitch ball — a quarter inch shy of safety. By some act of mercy, that trailer didn’t pop off on the cracked Alabama roads. It waited until Jen tried to drive Clyde up on it. After a warped hour of wrestling with ramps, gas leaks, and the Drake Mobile’s wide frame, we finally got him aboard, bolts and all, popping a few of his tired sidewalls in the process.

My father’s patience that night was its own quiet sermon. He didn’t fully understand why I’d drive five hours to wrangle a hooptie covered in stickers, but he knew it mattered to me — this strange inheritance of story and steel. Supporting the budding artist inside my goofy frame was something he’d done all my life.

For a while, Clyde and I had our run — a few fishing trips, a turkey hunt, loops through Walnut Grove with the windows down. Then my father fell into the fog

of dementia, and my attention shifted. Clyde sat neglected under a pecan tree, gathering dust and mice. After a friend helped me redo his fuel lines and replace the gas tank, I took my mom and son for a joyride. On the next outing, a blonde rat shot out from under the passenger seat like divine punishment. I even wrote a Kafkaesque story from that rat’s perspective — a piece of absurd grace hiding inside rust.

Not long after, the late Larry Littrell took Clyde up to his summer camp in Bristol. My partner Sam Bailey at SCOF helped coordinate the exchange, and before long Clyde was back on the road, reborn. The Trailer Trash boys shot a short film that turned him into a legend, and when I saw it premiere in Atlanta, any sense of loss melted into pride. Watching him on the screen was like watching a son go out into the world and not squander his inheritance.

Since then, both my father and Larry have gone on to that great flat in the sky teeming with 10-pound bonefish, while my life just kept trucking. Then one day, Elliott Adler — storyteller and podcaster behind The Drakecast — called to say I might be a good candidate to take Clyde again. It felt like a gift. The kind you might regret later, like a treadmill or a meditation course you never finish. A second shot at storytelling with Clyde, unfinished business circling back.

This time, I didn’t have my father’s steady hand, but I did have Broc — a mechanic, an Air Force vet, a friend who’s part wingman, part attaché, and all heart. Since my dad’s passing and the divorce, he’s filled a lot of quiet space in my life. He brought his 1991 Dodge Ram, packed meticulously with every possible tool we

might need. This time the trailer fit Clyde’s frame, and Broc’s precision offset my chaos. Clyde would still be The Drake’s flagship rig, but SCOF was stepping in to breathe new life into him — videos, podcasts, stories. We had plans.

We left the farm before sunrise on a late-October Wednesday, running on no sleep and too much ambition. Broc queued up Young Joc’s “It’s Goin’ Down” as we hit the interstate. It was, in fact, going down. Before I start complaining about how many hands had claimed and reclaimed Clyde, I should confess: I’m no better. Part of me just wanted to ride loose women near his V-8 rumble and feel the vibrations in their trunks. Divorce will do that to a man.

We stopped at Jack’s Hamburgers in Fort Payne. Broc usually flashes his veteran’s discount, but the cashier must’ve misheard him. “What? You want more butter?” she asked. Then, realizing her mistake, she thanked him for his service. Somewhere in that moment between misunderstanding and grace sat the whole absurdity of our trip — two tired men, a car full of ghosts, and a long road north.

We missed the Chattanooga exit and ended up toward Nashville, tacking on two extra hours. But it gave us a good stop at Shenanigan’s in Sewanee, where Broc schooled me on the meaning of “minding your Ps and Qs” — pints and quarts, he said, grinning. I believed him; he’s the kind of man who knows things most folks don’t.

We talked about life, failures, and Broc’s invented ailments — “motivational procrastination exasperation” and “aspirational incarceration.” Beneath his humor was wisdom, the kind you only

get after service and loss. Somewhere between that laughter and the rolling hills, I realized how foolish it was to ever let pride or misunderstanding cloud the joy of sharing this car’s story. Under different circumstances, we’d all have been friends. By the time we reached Bristol, the place hummed with the electric promise of old ghosts. Elliott had warned me: Clyde’s starter was sketchy, belts loose, something always on the verge of breaking. When I sat in the driver’s seat, I heard a tiny family of mice peeping behind me — Clyde’s latest tenants. I could almost hear my father’s chuckle in the static. Elliott texted: “You know how it is with that effing car.” I did. It’s always something with Clyde. We checked into the Hard Rock Casino, because of course that’s where this story had to go. Broc turned in early; I didn’t. I chased small wins into big losses, the slot lights buzzing like fireflies around my grief. By 5:30 a.m., I was broke and raw, realizing the father in this story wasn’t me — it was Clyde, teaching me lessons from beyond the grave. Larry must’ve been laughing somewhere, watching me hustle to haul this relic out of his old hills. By 9:30, Broc was rightfully pissed, counting the last dollars we had for gas. He’d become my father by proxy, asking the same question Dad would’ve asked, “You leave enough to get us home?”

It took every ounce of faith and caffeine to load Clyde onto the trailer. Gravity and prayer did the rest. We barreled south through the mountains, two ghosts and a car in tow. When we finally pulled into my farm driveway at 11 p.m., white-knuckled and half mad, I felt it — a wash of peace that settled somewhere between exhaustion and grace. God had gifted me not one

chance, but several. And though I started this story trying to tell Clyde’s, I see now it’s always been my own.

By Cola

Two ladies of the night Broc and I had befriended were headed to Panama City Beach for Bike Week. They made it clear it was a girls’ trip — no boys allowed. We laughed about it for days. If we’d announced a boys’ trip, they would’ve pictured strippers, fishing rods, and us hitching rides from lady bikers.

So we packed up anyway — me, Broc, and the new barn dog, Merla Haggard.

Merla had one merle eye and a coat the color of a tanned deer hide. She’d been dumped months earlier and taken up residence in my barn. Skittish as a ghost from past beatings, she’d only ridden in the truck once, to get spayed. This trip would be her first taste of the road.

The ladies called on our way out: could we swing through Panama City and drop off some newly acquired party favors? That detour added two hours to the drive. Apparently, even a girl’s trip needs logistics, and a geography lesson.

By the time we crossed the bridge into Carrabelle — the so-called Forgotten Coast — the light was flat and the Gulf smelled of diesel and salt. We met our guide and friend Justin Wilson at the VRBO.

Whenever you bring two anglers who fish differently — one fly, one spin — you’re inviting a low-grade bitch fight. Luckily,

Justin could guide both styles. The weather was pure punishment: overcast, wind at 20, water turbid as sweet tea.

Unlike Justin or Broc, I’m not versatile. I came up a fly fisherman, stubborn to the end. Even with wind whipping my leader sideways, I refused to touch a spinning rod or a Gulp plug. My father never taught me to fish conventional tackle. Not out of snobbery — just omission. After that early gap, I kept finding excuses never to learn.

Broc and the Gospel of Plastic

Broc swore he could fish both ways. Maybe he could. But his love of shrimpscented Berkley grease gave him away. Principles of fly fishing didn’t apply when his fingers smelled like bait shop perfume.

I stayed seated that morning while the sun sat wrong for sight-fishing, letting Broc and Justin take the bow. To me, sight-fishing has always been the purest test—seeing the fish, reading their movements through the light, convincing it with motion instead of scent. Ignorance, maybe. But a noble kind.

Justin came from Ohatchee, Alabama. I’d met him years ago at a Gadsden Fly Fishing Club meeting, where he first got me chasing striped bass below tailraces.

By trade he’s a biologist — one of those rare souls who can name every bird, bug, and weed in a watershed. He consults for developers when endangered species complicate their plans. Ask him about policy, and his answers make the hair

rise habitat Carrabelle started cockaded State wandered told first with He’d 30 devotion The I used marketing showed Broc said silence big — mothers,” generation.” Broc all

rise on your neck. His passion for the habitat borders on high-church sermon.

Carrabelle was his sacred space. He’d started here decades ago studying redcockaded woodpeckers in Tate’s Hell State Forest, named after a man who wandered lost for days and, when found, told folks he’d been “in Hell.” Justin’s first job out of college brought him here with benefits and a government truck. He’d watched this coast change across 30 years — the long durée of one man’s devotion to a fragile system.

The Ethics of the Slot

used to think catch and release was just marketing for more guided trips. Justin showed me it ran deeper.

Broc asked if we could keep a few trout. I said sure, if they were in slot. But Justin’s silence said otherwise. When we caught big breeders — 28-inch “gator” trout — he shook his head. “Those are the mothers,” he said. “They make the next generation.”

Broc landed 10 buck trout that morning, all keepers by law. Out of respect for

Justin, he released every one — but not happily. His instinct to bring meat home collided with Justin’s reverence for the system.

And then came the friction.

AND THEN CAME THE FRICTION AND THEN CAME THE

Bitch Fight on the Bay

Broc wanted credit for his catches. We gave it, but when he started offering flycasting advice — telling me where to land the bug, how to strip it — I bristled. Hunger and fatigue made us stupid. He thought I saw him as a dumb spin fisherman. I thought he couldn’t tell a visual eat from a blind one.

Bass-tournament certainty dies hard.

Back at the truck, words flew. We argued over who respected whom, over flies and plastics, over who got to keep fish. Eventually we called a truce before rage turned the air metallic.

That night we ate with Justin, Merla asleep under the table.

Conservation and Exploitation

Over dinner, Justin said, “If you’re not a conservationist, you’re an exploiter.”

Broc leaned on what he knew — bass tournaments and Alabama reservoirs. Justin met him there. “First thing you gotta do,” he said, “is tune out the dumb-ass noise. If you want bigger fish, stop keeping ‘em. Stop killing ‘em in livewells.”

He told us about Florida’s new rules that handcuff game wardens from random boat checks. Used to be, every cooler coming off the water got inspected. Now they need “reasonable cause.” Without that panopticon, overharvest flourishes.

Justin traced his own ethics to writers like Charlie Waterman and Al Lindner in Florida Sportsman and In-Fisherman

Magazine respectively, men who preached tactics and stewardship in the same breath.

He brought it home with a story from Neely Henry Dam: a crew hauling out striped bass by the vanload to sell in Atlanta. Different regulations for recreational and commercial harvest made it possible.

“CCA fought the netters,” he said. “That’s why you still have fish on the flats.”

Broc nodded the way a man nods when his theology is being rewritten.

Merla’s Sermon

By the time we stepped outside, the night had gone still. The Gulf lay dark beyond the pines. Broc and I leaned against the truck, quiet.

Merla was curled in the backseat, twitching in her sleep. Maybe dreaming of the road, or the barn she’d once been left in.

Watching her breathe, I thought about everything Justin had said about keeping, taking, and what survives when no one’s looking. Maybe conservation starts the same way love does: with restraint.

I reached in and scratched her ear. She didn’t flinch.

Tomorrow was cancelled as a result of the twister that hit Mexico Beach.

But that night, on the Forgotten Coast, it felt enough just to let the wild things rest after the storm.

The Premier Fly Shop in Blue Ridge, GA

By Cola

“The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away.”

That’s what Zack muttered when we found my old 4-weight dangling from a pine limb along the logging road to the Locust Fork. I’d lost it a month earlier, stomped this trail half a dozen times looking for it, and finally given up. I even swallowed my pride and bought a new one.

Well, sort of bought.

Frank Roden, owner of Rainbow City Auction and Fly Fishing, had cut me a deal the way he always did. Three hundred bucks off a fresh TFO Pro III, so long as I promised to work him into a story. Frank’s deals weren’t about the money. They were about the relationship, the handshake, the story you owed him later.

Finding that rod again should have felt like a miracle. But when I snapped the tip of the new one later that same day, Zack just shook his head and quoted scripture. That’s fly fishing in Gadsden: one step forward, one step back, usually with Frank somewhere in the mix.

Frank the Ranger

I’ve known Frank for 30 years, long enough for him to stop calling me “Guy” and start calling me by my first name. He grew up a hunter in the ‘50s and ‘60s, maybe farm kid, maybe mill village, maybe a little Cher-

okee blood in there somewhere. His skin stayed sun-dark, his hair turned silver and perfect, like a general out of central casting. Turns out, he was military. A ranger. Vietnam. He doesn’t talk about it much. The three times I ever heard him mention it:

1. The Elevator Story – He got so drunk at a military ball he spent the night riding the elevator in circles until his colonel found him. The colonel told him to never drink again. Frank never did.

2. The War Story – He told me flatly: “Those people didn’t want saving.” Nothing else.

3. The Dove Shoot Story – I invited him hunting, and he said no. After Vietnam, he’d had enough of killing. Catch-andrelease was his salvation.

That’s why Frank fished carp before it was cool. Why he chased stripers like a man possessed, but never once told me what rock to stand on. Why he winced at bowfishermen leaving dead carp floating downstream. Fishing gave him back something war had taken away.

Frank married his high school sweetheart, raised cattle, and opened an antique store with her above the old Cow Pasture driving range. Then, one day, they decided to open a fly shop: Rainbow City Auction and Fly Fishing.

The place sold Orvis, Scientific Anglers, and TFO before most folks around here could pronounce Temple Fork. He built a community the old-fashioned way—discounts, advice, and photos of local heroes holding fish bigger than your leg.

Frank also started the Rainbow Fly Fishing Club, which meant every angler in Etowah County eventually owed him something: a leader, a casting tip, a spare spool, or a debt of gratitude. He asked me to serve as president once. I said yes because when Frank asked, you didn’t say no.

Later, he partnered with the city to stock rainbows in Black Creek below Noccalula Falls. Purists griped about native species, but Frank wasn’t in it for purity. He was in it for the joy of watching a kid catch their first trout in Gadsden. And he pulled off a fly fishing festival at the Venue, no small miracle in a town that still thinks a Zebco is high-end gear.

Not everyone saw eye-to-eye with me during my tenure as president. One night, a 70-year-old member and his wife came after me with a dossier of my Substack ramblings, ready to toss me out. Frank stepped in, calmed the room, and vouched for me. He didn’t have to, but Frank always had a way of saving people, whether it was carp flats, fly shops, or foolish friends.

The best part of Frank isn’t his service, or his shop, or his fishing. It’s the little things:

» Spooling your reels like a barber who’s seen it all.

» Knocking a few bucks off a rod without you even asking.

» Listening to you talk about a day on the river while you hose down your skiff in his parking lot.

I always wanted to get him on a bigger stage — chase peacocks in Colombia, tarpon in the Everglades, or even just carp in his backyard. But Frank was content where he was. Content to keep Gadsden in waders and carp honest.

That day on the Locust Fork, I found one rod, lost another, and felt the whole circle of my fly fishing life spin back to Frank. Because the truth is, when my TFO tip snapped, I didn’t curse or throw it in the river. I just thought, Time to go see Frank. He’ll call TFO, explain in his calm way how dumb I am, and somehow make me feel like I’ve done him a favor. That’s his gift.

The day I can’t go to Rainbow City Auction and Fly Fishing, the day I’m forced to order rods off Amazon Prime like some godless heathen, will be the day something vital leaves Gadsden. Until then, I’ll keep finding and breaking rods, and Frank will keep giving and taking away, in the way only he can.

by Flip McCririck

There’s a line in the 1987 film Broadcast News, two guys are talking about life. One asks, “What do you do when your real life exceeds your dreams?” The other replies, “Keep it to yourself.”

Some 30 years ago, James Shaughnessy was camping on the beach at Bahia de los Muertos in Baja California Sur. He knew the game like few others, hence his dilemma.vEventually he opened a shop, FlyFishMEX. South of La Paz, he leased a lodge that never came to fruition. He also operated on the west side of Baja Sur out of San Carlos, fishing Magdalena Bay. I got to visit the east side thanks to my friend Kim Reichhelm. The country club atmosphere is crazy high end. Unusual for a fish lodge.

Luckily I was fishing with Kim, who lives in Baja Sur, and is familiar with the fishery. Inshore we targeted roosterfish, golden trevally, ladyfish and big jack. Offshore it’s dorado, tuna and billfish. My singular goal was to catch a rooster. Fishing with guide Ramon Jr., we were doubled up by 8:00am on day one. An unbelievable guide; he offered valuable advice, I listened. Never guide the guide — unless you want to catch zero fish. You may think you know, you don’t.

First stop is the bait boat. A critical part of the equation here. Baitmaster Rio was out early, throwing casting nets and collecting sardines in the hollowed out hull of his panga. Roosters are speed demons; they arrive mach looney, hit hard and fight ‘til in hand. Seems to me that the most insane saltwater fish have a bit of the devil inside.

We fished a few more spots along the beach near Punta Arena, and caught a few more. Soon the ocean life was onto us — birds, packs of jack, and giant needlefish forced us to play keepaway with our flies. Ramon Jr. suggested we move out to deep water to chase other species. Before I knew it, we were doubled up again. This time: dorado.

James is from Medford, Oregon. He started Beulah Fly Rods and designed the best sardine (Shaughnessy’s Nyacca) and mackerel (Holy Mackerel) flies produced by Montana Fly Co.

We are lucky that James decided to put the word out. An absolutely amazing place. I will definitely revisit Baja Sur with new goals, including catching roosterfish from the beach while surfcasting, and maybe someday a marlin offshore. Check out FlyFishMEX, real life exceeding dreams.

by Rob Beckner illos by Bill "Poon" Bishop

Drinks are flowing, country songwriters singing, the English Cocker Spaniel puppies arrive. Every year at Heritage — a hunting and fishing club in East Central Florida — hosts a Nashville songwriters night for its members. Belt buckles, boots, and top songwriting talent shows up to perform for less than 75 lucky people.

About halfway through this year’s event, one of the club’s professional quail guides pulled up in his pimped out Polaris side-by-side toting boxes full of unsold puppies. This guide breeds championship English Cockers, beautiful dogs with a crack habit for quail. Like an idiot, I’m enjoying the music, cigar, and brown drink, focused on the singalong, inattentive to my surroundings. Cowriter Jordan Schmidt was singing and telling the story behind “Watermelon Moonshine,” made popular by Laney Wilson, when my wife walked up holding a brown and white puppy. I did not think much of it as we already had a family dog, figuring it was just “pet the puppy time.”

An hour later, she walks up to me still holding the dog and says, “We have a 9:00am appointment to pick the dog up tomorrow.” After 23 years of marriage, this was the first big decision that was not discussed, instead it was a husband’s moment to shut up and smile. Not that I didn’t want another dog, but a 15-plusyear commitment isn’t something that’s purchased on a whim.

The following morning, I reluctantly drove to the guide shack to pick up the light brown Cocker with white freckles. We named him Whiskey. Just before we arrived, I told my wife that sometime soon I’m going to play my newly earned Whiskey card, my own non-discussion purchase. In the back of my head I already knew it would be a tiller skiff — I had finally found my angle to justify the unnecessary. We already had an 18-foot skiff sitting in the garage, a great family boat. Living near Mosquito Lagoon and the Everglades, I really wanted (but could not rationalize) another boat. A true technical poling skiff would vastly expand the options in our area. A selfish two-person machine that would dry launch in a pothole and float kayak shallow had been floating in my head for years. With the Whiskey card in my pocket, I patiently waited for the right skiff to come my way.

Eight months later, my buddy, who owns

our local fly shop in Melbourne, calls me up and says, “Harry Spear is in town with a 16-foot skiff he calls ‘The Legend,’ you must check this thing out.” Pulling up, I see a light gray hull with an off-white deck. This boat belongs to the famous Keys guide and boat builder Harry Spear. For those that don’t know Harry, he has won all the major fishing tournaments in the Florida Keys. He has guided all the best anglers. He’s the real deal. As a boat builder, he has a unique perspective of what a skiff should be after years on the water.

Just like our new dog, the boat found me. Harry, unaware he was about to sell his personal skiff, gave me a quick float and said, “Sure, I’ll sell this thing.” We shook hands, and I purchased the skiff right off his 2-inch stainless hitch. Driving home I was laughing, no call to my beautiful wife. I played my Whiskey card perfectly. Later at home, inspecting every inch of the boat, I found written in Sharpie under the front deck “Bless this boat and all who fish on it, let it be safe, stealthy and fishy.”

A non-alcoholic christening, no smashed champagne bottle across the bow of this craft. The perfect fly fishing set up with under-gunnel, rear-facing rod holders, 25 hp tiller outboard, 10 gallon fiberglass fuel tank under the bow. This boat is so simple, two switches that run trim tabs and a bilge pump.

A fly fishing slayer, this boat has caught every

shallow water fish that swims, from reds in Mosquito Lagoon to bonefish in Islamorada. This beloved skiff is now as much a part of the family as the brown Cocker sitting in my lap. I raise my glass and toast to the great things that come from Whiskey.

FALL fluffer by alan broyhill

Expand the possibilities and enter a new era of ne-tuned shability with the latest progressions in freshwater multipurpose y lines from RIO – new Gold XP, new Gold MAX and Classic Gold STANDARD.

THE ALL-WEATHER CAYO TM BACKPACK

by Tom Wetherington

Cape Lookout, North Carolina.

“Fisherman’s Paradise” — or so says one of the water towers. Drive in any direction here or through nearby Morehead City and you’re guaranteed to see a boat within 30 seconds. It’s either passing you on the way to a ramp, parked in someone’s yard, or sitting on a trailer for sale at a dealership. Stop for gas or sit at a red light and you’ll probably see a truck with rods hanging over the Tailgate.

October might be king mackerel, bluefish or redfish month, but around here, another species is on everyone’s mind: albies.

False albacore, little tunny, or just “albies” if you’re in the know. Their season is short but wild — all speed, chaos, and heartpounding runs. Albie fishing isn’t delicate, it’s not slow, and it’s definitely not relaxing. It’s pure adrenaline. If you like throwing streamers and watching your reel scream, this is your jam.

From late September through Thanksgiving, north winds push the bait offshore while albies blitz in from the Gulf Stream. It’s a perfect collision of predator and prey — fast,violent, and beautiful.

They’re not much for the dinner table, but these little tuna pack more punch than anything else you’ll find close to shore. Birds dive, bait explodes, and boats spin in every direction trying to keep up. It’s like playing Whac-A-Mole on water. One

pod blows up a hundred yards away while another erupts right off the bow. You chase, curse, cast, and repeat. And somehow it never gets old.

Albies have become part of coastal North Carolina’s identity, and the Cape Lookout Albacore Foundation keeps that spirit alive with the annual Albie Fest. The event started back in 2002 as a fundraiser for children’s cancer care at Duke Children’s Hospital. When it was revived in 2014, the focus shifted to Project Healing Waters Fly Fishing, helping veterans heal through time on the water. Each fall, more than 100 veterans come to learn to tie flies, cast, and fight albies. It’s chaos, laughter, salt

spray, and gratitude all mixed. A perfect match between the fish’s energy and the people who’ve served.

So yeah, mark your calendar for next fall. Coastal North Carolina, a boat, a few friends, and a blitz of albies will change the way you think about inshore fishing. You won’t regret it.

By Alan Broyhill

Is this a sweet lil' rod??

Well, I’m no Scott Stevenson, but I’ve cast a rod or two, and this one ranks high in my trout-rod category.

Lately I’ve been casting 5 wts way more often than I’d like to admit. On my normal adventures, I’m usually leaning on something 7 wt+. But these days I’ve been addicted to the after-work trout session, or maybe that's all I've had time for?...Anyway, I’m fortunate enough to have a few choices in the 5 wt category and a trout river nearby. This rod honestly does look classy. I’ve owned a lot of TFOs over the years, and that’s a first coming out of my mouth. The wooden reel seat looks primo and matches the subtle wraps on the lower rod and the paint on the reel locks. The blacked-out hardware keeps it low-profile without trying to look like the Batmobile. I personally love the unsanded blank look because it reminds me of all my old-school trout rods I’ve collected over the years. On the functional side, TFO threw in some of the recoil guides. Being a frequent boat fisherman, I approve of this move—it gives it that extra classy touch as well.

But does it cast?

I’ve put this rod into about 20 clients’ hands over the past 5 months, and my fiancé keeps stealing the damn thing and giving it to hers (without asking). TFO claims it’s a moderate-fast action rod, and I’ve got to agree. Even the newbies pick up a multi-fly indi rig with ease. Of course, the right line helps with that, but it’s still no easy task. Most of these folks have never picked up a rod before, and I’ve got to say the taper makes it work for them. The clients who do have some experience seem to dig how smoothly this rod loads.

For myself, I’ve been using it to throw afternoon streamers after what little rain we’ve had and the occasional dry fly instead of carrying two rods up the river. If you don’t overload it with too big of a streamer, it does surprisingly great (it is a 5 wt, after all). But it really excels at the dry under the rhodo or the dry-dropper rig. I think this rod really responds to a semi-fast stroke (yes, I chuckled when I typed that), and there’s no need to overline it with a 9-foot leader.

So what’s the verdict?

This is an accurate, primo 5 wt coming out of TFO’s lineup—perhaps my favorite 5 wt from them that I’ve ever cast. At 2.9 oz,

it’s light enough in the hand, yet I haven’t found a reasonable rig this 5 wt struggles with. It’s not overly flashy but has an upscale finish. First-timer or expert, this rod does just about anything I ask it to. In full transparency I have not had a chance to cast this rod in heavy wind or land a fish over 16 inches, so take that at face value. I lined mine with an SA Amplitude Textured Trout line in 5 wt on an old Lamson Konic. I’m giving this one my "sweet little rod" stamp of approval— especially at $550, tough to beat.

Did I do that right, Scott??

on the Fall Line stretch of the James River in downtown Richmond, VA. Between the size of the river (it can be a quarter of a mile across at its wider sections), highly pressured bass population, the everpresent host of environmental bad-actors, and a strong and volatile flow, it’s a good day if you catch two or three smallies in a six hour

personal flotation device that I purchased after a hard lesson learned.

Of course she has flaws, but I love her alongside them. She can be brutal, but that’s because she isn’t curated for your pleasure. She isn’t flush with bass, but that’s because she gives the fish a ton of options to hole up and it’s your job to exercise discernment to find them. She

man.

I hear folks often say “it’s not about the fish,” and I’ve largely stopped believing it. To be clear, there’s nothing wrong with saying “it’s about the fish.” Here’s something to acknowledge though: do we really need to go fly fishing to love fly fishing? For most of us, the jury is in! We know that we love it, so instead what if we shifted our focus onto loving local (and likely less productive) water? Loving a mountain where you don’t live is only something you can do as you

blow through it, but loving the water in your own backyard is something that requires tending and engagement.

Yes. I’m proposing a mentality that will mean less fish, and that should sound absurd. For those of you who make your living off of putting your clients on fish, this sacrifice is simply too much. You aren’t my target audience here, so you can disregard everything I’m saying from here on out. It has been observed by many that our world at present assumes that acceleration should be the norm. We have entire industries built around optimization and single-minded utilitarianism. If you wanted to find a way to optimize your life, you’d have to optimize the query of your search. I have caught myself doing this with my fishing. There have been spells where it felt like every decision was made with the intention of maximizing the number of fish in hand because I wanted to catch more than last summer. More. Bigger. Growth. Etc. I have found that the best defence against this is a violent offense on the side of its opposition. Instead of driving an hour and a half away to catch thirty smallmouth in an afternoon on a creek-sized stream, I drive ten minutes and rock hop over rapids to catch a few (at best) smallmouth. Do I still get hung up on numbers? Of course! But when I’ve intentionally lowered the ceiling of those numbers, it does shift my mindset more towards exploration and appreciation over growth and success. Just by choosing less productive and more local water, we are engaging in a counter formational process that can be really helpful in keeping our recreation untainted by utility.

For what it’s worth, I’m not the only one who feels this way. If I’m out and I see someone across the way covering water like his life depends on it, I know that’s Ray.

He does really impressive custom metal work with knives, and one time I let him borrow some leader material on the water. I’ll see the boats of our local guide services taking folks out for the stripers and shad when they make their way up from the saltwater every spring. My son got to strip in a hickory shad with one of the guides last spring, which was really special. Stu, the owner of a guitar and ukulele shop in the city (which also happens to sell whopper ploppers), will be roping in a truly horrific flathead catfish downstream of the rapids by the financial district of the city. All of this will be happening at once, and most of the fly fishers in Richmond are missing it; their car isn’t in park yet because they’re driving out west to the trout streams.

When we stay local, we allow ourselves to plug into the local community of anglers. For me, these are folks who can be on the water when I’m not since I have three young children. On nice days, I’ll get pictures of 14”-22” smallmouth in my texts because the folks who I’ve met are showing off their big catches. They aren’t tight lipped about what’s working either, because I’m not coy about where I get the catches I text them about. We’re all seeming to work as a team, because we have agreed that our river is worth our time. It’s definitely not a “less is more” mentality, but rather a “less is enough” mentality. My wife often says that we love something most when we love it into beauty. As I’ve caught less fish, with an inefficient style of angling, on a river that has teeth, I have fallen more in love with the work of fishing and the office in which I do it. When we choose the more inefficient means of travel, say the low CC engine motorcycle, we open ourselves up to adventure in places that we become overly familiar with.

As I catch more (and less) fish on my local river, I am more and more taken with not only my river, but the city which it undulates through. Truthfully, I don’t even have to fish it to love it anymore. It’s almost as if the river itself has trained me to stop viewing it through the lens of accomplishment; I’m now freed up to see this river as a river instead of a fishing spot. Now, it’s beautiful because I love it, and not because it gives me what I want.

Practically speaking, I have found that creating a bucket in my mind for “fishing” versus “fishing trip” is appropriate. When I attach “trip” to something, my lizard-brain sees that as a special and non-normative thing. The default is “fishing” and that’s done on the Fall Line of the James River. I want to encourage you to try the same thing, and give yourself the opportunity to love your less productive local waters into something beautiful.

By Will Coker

The White River in Arkansas is straight-up Jurassic Park. You float it and swear the banks are gonna rumble with a T-Rex at any second. Only instead of dinos, it’s 4-foot-long browns stacked like logs under every ledge, waiting to ruin your ego and break your rod.

We came down for a bachelor party, half fishers and half dumbasses who wanted nothing more than to drink beer and apply sunscreen. Branson, Missouri, was our pre-game: neon lights, washedup country singers, and us beating the streets for any kind of old poon that’d give us the time of day. Didn’t find much worth writing home about, but it got us in the proper headspace for the river.

We got there and the water was low. We made 500-yard laps below the dam, and the dry fly bite was on — risers sipping daintily like they were at high tea in Charleston. But when the dam turned on? It was game on. Jurassic, big-brown, hang-on-for-your-life game on.

I hooked my beast on a size 20 midge, under a wool indicator, fishing 6x like some kind of idiot. As soon as it ate, I set, and it felt like I’d snagged a cypress stump. I looked over at my guide, BJ (and no, it doesn’t stand for blow jobs, though after what he pulled off, maybe it should). We both gave each other that no-teeth, shoulder-shrug smile like, “Oh fuck.”

I asked him what size tippet we were on. He wouldn’t say. I asked if he tied a surgeon’s knot or a blood knot. Wouldn’t tell me that either. He just kept rowing, grinning like a man who’d seen this movie a hundred times and knew the ending.

Twenty minutes later, after enough downstream runs to put me in cardiac arrest, we slid that prehistoric slab into the net. We didn’t shake hands, didn’t highfive, we straight up hugged, like two men who’d just survived combat together. And no blow jobs were had.

That’s the White River — Jurassic trout, mystery knots, and a guide named BJ who’ll leave you questioning everything but your love for this river.

by Hank

There’s a restaurant owner from New York named Will Guidara, who wrote a Unreasonable Hospitality. He talks about how doing small but absurdly personalized things for your customers (not necessarily extravagant things) can improve the quality of your service drastically. Not only that, but he believes the more people who adopt this posture, genuinely seeking personal connection through service, the better the world will be. I think he’s right, though I wonder about all the people who scream at waitresses for serving them cheeseburgers with unwanted slices of tomato. If angry cheeseburglars grow to expect unreasonable hospitality, how will Guidara raise the bar? He probably thought of that, and wrote about it in his book, which I admit I haven’t read. His

In his TED Talk, Guidara makes it pretty obvious that giving people a memorable experience is easy and mutually beneficial. He got the idea when he overheard a table of foodies he was serving in his fancy New York City restaurant express regret that their trip was over and they never got to try an authentic NYC street hot dog. He went down the street and bought them a twodollar hotdog, and that gesture started a movement. Telling you about Guidara’s idea isn’t really important for contrast with what I’m about say, as much as it is important to get you, reader, thinking about what makes you feel cared for, and what your bar for unreasonable hospitality is in the fishing industry, which, let’s face it, is as much about service as it is about commodity, community, and conservation.

Brownie Liles, the owner of Watauga River Lodge, may have read Guidara’s book, or maybe he has a Southern intuition for making you feel good. During my stay at his lodge with the SCOF gang, he had several cheeseburgers made for me (with tomato) and asked me about my marriage. He offered me a sound bath behind the giant gong in his boat shop. He admonished me graciously for parking on his grass, grass that he had to re-seed after Hurricane Helene nearly wiped out his business. He made me feel like a kid, but not because I felt small or castigated. Because I felt provided and prepared for. I felt like equal parts guest and family.

Everything was ready for us when we got to the Watauga River Lodge just outside of Elizabethton, Tenn. Brownie (named as a baby by his older brother for his resemblance to a house elf) and his wife were waiting at their barn on a repurposed horse therapy farm tucked neatly in a hillside facing west. As the sun set, we drank Miller Lites and watched the show, discussing our favorite victuals at the periphery of popular edibility. For some reason, Brownie avoids swine. He and his son Stokes, a wild-haired whitewater fanatic with an ironically stillwater temperament, keep a mostly Halal diet, though they wouldn’t call it that. This quirk made it all the more fun to discuss things like souse, which I know to many mountain people is either a delicacy or a freakish vestige of harder times. We all relished the opportunity to gross each other out with our favorite nondelicacies. Sam Bailey sang the praises of Spam. I love a NYC street hotdog. Being prepared for, I’ve learned, is the mark of true hospitality. Arriving at your host’s accommodation and seeing

that you’ve been expected and provided for is always heartwarming. We all got our own neat cabins with stocked refrigerators, welcomed in by the sound of the Watauga River washing the bluffs, obviously commanded by some authority to lull us guests perfectly to sleep. If it was Guidara’s lodge, maybe there would have been a box of oatmeal creme pies waiting for me in the room, but Brownie’s generosity is not about trying to impress you with stuff. His style of hospitality is about generosity of spirit, and the promise of provision on the banks of his sacred river. It’s a God thing. It is necessarily unreasonable.

In the morning, we took off with borrowed boats and fished another river with better prospects for smallmouth. Brownie stayed behind to prepare the grand re-opening feast planned for that night. In his stead, he sent Davis Park, the valedictorian of the Brownie Lilies School of Hospitality. At the ramp with two of the Blue Ridge Boatworks drifters, I offered to row Davis’ boat first, a gesture of thanks for hosting us. (I’ll warn you, if you always offer to row first, your friends will catch on to your scheming — you watch and try to learn what’s working while you row, and then hop up in the bow when the fishing gets good. It may keep you from being called a bow hog, but it won’t ever be called hospitable.)

I watched and waited for a while as Eric Dickinson, our third, multi-tasked with ease from the stern seat. He spent the first hour casting a Chuck Kraft Excalibur bug with one arm, and a bone-chartreusecolored fluke with the other. Although he never rowed a stroke all day, he provided enough entertainment to make it clear that he was no novice in hospitality either. He guides for an outfit in Bristol.

Then the rain came. “It’ll burn off,” I said, knowing nothing about the weather patterns in the mountains except that they can be unpredictable and devastating. It was a prayer I learned in Southeast Alaska, where it rains 90% of the time. Despite my prayers, the bottom fell out. I stashed my shirt so I’d have something dry to put on after rowing, and I burned it down to the bridge for shelter because I did not have a rain jacket or a motor. Anchored underneath, we watched lightning strike and estimated the proximity of the bolts that were landing. Eric and I were both shirtless, but Davis lent him a pair of waders that were cut into bibs. He looked like Orvis McDonald, and sang E-I-E-I-O through chattering teeth. After a few moments, Spam, Bailey’s boat, pulled up beside us with Alan Broyhill and Al’s fiancée, Lydia Dann. We ate pickled okra and passed around a tray of max-stuffed Oreos, trying not to spill as we shook from the cold and jumped at the cracking booms. Eventually, we abandoned the safety of the bridge and pushed on, following another pair of guides whose clients were mummified in Gore-Tex. Davis took the oars and gave them a hospitable amount of space, though nobody needed it. The fish weren’t

To preserve morale, the guides in my company tried hard to keep the boat filled with laughter. Every silence was interrupted with a parroted sound bite from the funniest reels we’ve seen on Instagram. Joining in, I spent most of the afternoon impersonating the kid chef who throws “unguns” (onions) “into the bowl!” I can’t really explain why it’s so

Focus groups don’t fish.

We don’t chase trends. We chase hatches, tides, moon phases, weather windows, and risers. High-performance apparel designed for better days on the water.

funny, but to the three of us, it was. The way our senses of humor meshed so perfectly made me feel like we all lived the same childhood. I don’t know if they were intentional about making me feel like their brother, or if it was again that Southern intuition that kept me laughing through the rain.

Then the rain stopped. Even though I only got to experience what Davis said was the best sight fishing opportunity in Appalachia for a few hours, we did get a few chances at perfection. I got to see Eric expertly shoot a stealth bomber that was sipped at 70 feet, and I got to watch a big smallie chase a streamer across a clam bed. Neither fish was landed, though

others were caught. The stoke that the two guides were able to conjure out of bad conditions was inspiring to me, and it got us through a long night of podcasting. Really, the only reason it felt long was because I wagged my jaw for too long about fisheries ecology, and I was tired from laughing all day. The rest of the podcast is really good, especially the parts when Davis and Brownie talk about the business. I won’t spoil it for you, but if you listen, it will become clear why Brownie is in his own tier of unreasonable Southern hospitality.

.

by mike steinberg

I recently attended the 8th International Bonefish and Tarpon Trust (BTT) Science Symposium in Fort Lauderdale. The event was an interesting mix of old and new, science and sport, etc. It’s really a one-of-a-kind symposium given the balance between our sport and the sum of the latest research that shapes the management of our sport fish populations and habitat. In other words, there were just as many guides and sports as scientists. For the purposes of this column, I thought I’d highlight my favorite presentation. I will admit as an academic, I largely attended the science sessions, although I sat in on a couple of panels such as the Tarpon Panel led by tarpon luminary Andy Mill.

My favorite science talk was given by Jose Trujillo, a BTT staff scientist, titled, “Co-producing knowledge to reduce conflicts between sharks and fishers in the sportfishing capital of the world, the Florida Keys.” That’s a long title that describes the growing problem between anglers and sharks in some very specific, very popular angling destinations in the Florida Keys and Everglades. If you fish regularly in South Florida, this issue probably isn’t new to you. I lost a large permit to a bull shark under my boat more than 20 years ago near Marathon, and hammerhead predation on large tarpon under the Seven Mile Bridge is a long running, contentious issue.

Trujillo’s presentation wasn’t made to an audience of half-engaged anglers on their smart phones. There was a distinct tension and focus in the room as many,

especially among some of the guides whose livelihoods depend on the Keys and Everglades, wanted answers about what to do about the increasing heavy rates of shark predation on sport fish. To Trujillo’s credit, he didn’t promise any dramatic solutions. That wasn’t his job or part of the presentation. He calmly presented his data on predation “hot spots” and described the changing behavior of sharks in response to the presence of more anglers. He did mention there are some experimental shark deterrent technologies emerging, but there are no easy, quick solutions. This didn’t satisfy everyone, but I think everyone understands it’s a complicated issue. We didn’t get to our current place overnight, nor will it be “fixed” overnight. For my two cents, I think it’s easy and understandable to simply say, “There are too many sharks. Kill them.” We as humans have a long history of blaming

predators who learn and react to actions that we put into place. We can see other examples of this with wolves in the West, coyotes in the South, and even Cooper’s hawks divebombing birds at our bird feeders. We as humans expect order and predictability in the natural world and are uncomfortable when that order threatens our well-being or our recreation, or both. This reaction is understandable on many levels, but it also presents no solutions. Nature is neither orderly or predictable.

Predation in the natural world is part of the natural order of our planet. And when we do manage to reduce or eliminate predators, we create other cascading problems that we often have to clean up later on. If you haven’t read it, take a few minutes to read Aldo Leopold’s essay, “Thinking Like a Mountain” in his 1949 publication A Sand County Almanac. I won’t give the plot away because it’s one of the most important environmental essays of the 20th century and well worth the read.

My takeaway from the presentation was that sharks have learned where anglers concentrate and therefore potentially have access to an easy meal. Sharks aren’t the mindless creatures demonized through the movie Jaws. And as some in the audience pointed out, when we concentrate angling efforts in consistent locations, we are basically ringing the dinner bell. Perhaps it’s time, as was mentioned by some after the presentation, that we think about our role in this issue, not just the predator’s. There are more anglers, more boats (rentals, day trippers, and guides), and thus more pressure in certain areas in the Keys and Everglades. Even the most seasoned guides on various panels lamented the growing pressure on sport fish populations

and in some cases declining fish numbers such as tarpon as a result of this pressure and habitat change.

Perhaps it’s time to start a conversation about “managed access” to certain hot spots to begin to break what seems to be a multi-generational learned behavior on the part of sharks. Perhaps it’s time to shift our focus largely from snook in certain areas to jacks or snapper. Like the sharks, we (especially clients) are trained to have expectations about what an expensive day on the water looks like and its results. That, too, is untestable, especially for the casual angler, who only gets out a few times a year. But again, it’s probably time we change some of those expectations to better fit the reality of the current situation. In the end, I’m not sure we really have a choice given that nature dictates her rules on her terms.

I also want to briefly mention one other presentation titled, “Flats food web study: Assessing permit and bonefish prey across our flats,” by Ryan James. My big takeaway from this interesting study was fish more crab flies, yes, even for bonefish!

by dr. professor mike

Campeche is a hard place to describe. It’s on the Yucatan Peninsula, but not in the Yucatan state. Campeche City is in Campeche state, so you need to differentiate between city and state. Many Americans are geographically challenged, so I usually just tell people it’s to the southwest of Cancun, on the other coast, and leave it at that. I’m not sure that is very helpful, but it’s the best I can do. As opposed to Cancun, there are no nearby beaches, so you don’t have the crush of American tourists that you have on the eastern side of the Yucatan. In fact, besides small numbers of American anglers, its mainly Europeans and Mexicans who visit the city based on my cursory observations. Beyond the simple location, it’s also a challenge to describe Campeche from a purely angling standpoint because it offers much more than angling. Overall, it’s probably the most interesting spot I’ve fished given the rich history and nearby geography. The city of Campeche is a well-preserved colonial city that surrounds a classic plaza with an ancient cathedral. Its perimeter wall, built in the 17th century, still stands in many places that was originally constructed to defend against English pirates. About an hour outside the city is the Mayan ruin Edzna, a sprawling well-preserved site with multiple multi-story pyramids. If you are at all interested in Mayan archaeology, it’s well worth the side trip that can be easily set up by Alejandro Hernandez, owner of Campeche Tarpon, my outfitter.

Don’t get me wrong, I enjoy the lodge scene, but this isn’t the typical lodge destination where you see the same people night after night and hear the same stories night after night. During my last trip, I didn’t have a single conversation with a fellow angler outside my buddy I was travelling with, so not a single pissing contest about the biggest fish or longest cast ensued. Every night, we found a different restaurant and a different bottle of excellent Mexican wine from their emerging wine economy centered in the Baja region.

Now, onto the angling. I’ve fished Campeche four different times dating back 12 or so years. It’s one of my favorite angling destinations not only because of all the interesting landscape features, but also the large numbers of juvenile tarpon. Some of these fish, deep in the mangrove lagoons, are tiny. But you can also find plenty of eight- or nine-weight-worthy fish on the mangrove edges and the short rivers that lead into the mangroves. And while many fish enthusiastically thrash a fly with abandon, these fish are not always easy to land. They don’t have much flesh in their mouths when they are just a few pounds, so it’s easy to under strip set (based on their size), watch the fish jump once, and then say, “Goodbye, amigo.” Or I reverted to trout setting, thinking that would be plenty of pressure to hook a few-pound fish (mistakenly), much to the chagrin of my guide.

The angling takes place on a long, thin strand of protected mangroves that stretches from Campeche far to the north along the coast filled with birds and tarpon. In fact, the birding is

so good that King Charles (then Prince Charles) toured the area in 2014 in the very skiff from which I fished. Some of the fish cruise the edges depending on tides and sun conditions, but many more ply the narrow canals and small lagoons inside the mangroves adding to the challenge. I saw schools of 1020 fish cruising and rolling, but also some singles and doubles of bigger fish moving along the edges. The higher the sun, the shyer the fish become and deeper they retreat into the mangroves, so this is an early riser destination with first cast in near pre-dawn conditions. I’ve never lost a fish to a shark. I’ve always been curious as to why until I visited the fish market and noticed a lot of small, gilled netted sharks for sale. There are some snook and barracuda, but this is all tarpon all the time.

I think sometimes we think smaller fish represent smaller challenges, but this isn’t the case at all in Campeche. It was humbling at times, but a great experience in saltwater fundamentals that helped me refocus. No, you won’t need your 12-weight gear unless you want to hook a frigate bird, but it’s a hell of a lot of fun jumping innumerable mini-megalops, especially with a bottle of Mexican cabernet waiting for you at the end of the day.

by Judson Vail photos by Brandon Brown

It’s a bad day to be a piece of trash in the river.

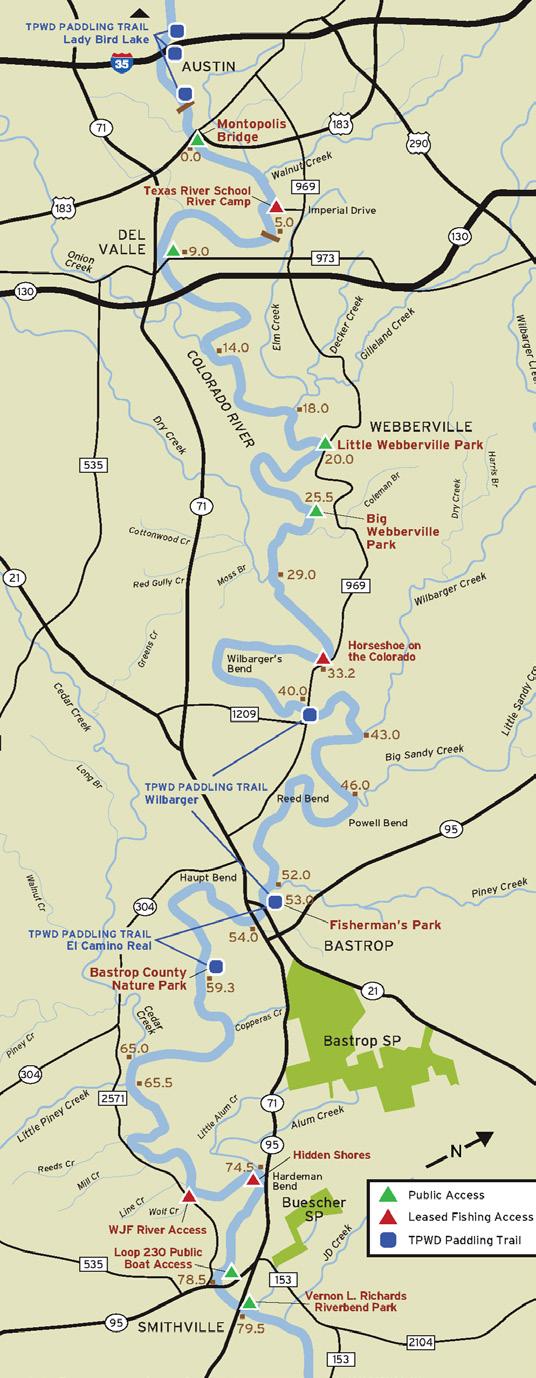

That’s what I keep thinking to myself as I race out of Austin, down FM 969 towards the hamlet of Webberville. I stuff an unripe 7-11 banana in my mouth and wash it down with some decaf. The sun is still well below the horizon on this warm and muggy Saturday, but you have to wake up pretty early if you want to get a jump on Colorado River litter.

I’m on assignment for Southern Culture on the Fly. Well, we haven’t actually made a deal about anything yet, or even spoken. I’m just sort of pretending I am. Nevertheless, I’m going to give them a hard-hitting story on the 7th annual LoCo Trash Bash, the big river clean-up hosted by Alvin Dedeaux and All Water Guides. LoCo means Lower Colorado to us here in Central Texas. Although, we know what it means in Spanish too. ¿Comprende? No fishing today. Just pure, raw garbage collection.

I arrive at the Little Webberville boat launch right at 7:00. A few other people are backing up trailers and milling about in the dark. Gibson from AWG is passing out nylon mesh trash bags and longhandled grabbers, and also making sure we waive our right to litigate in the event of a mishap: snakebite, tetanus, Giardia. The usual hazards attendant to a river cleanup. We chat about the water and fishing as the gray dawn breaks and the rest of my squad pulls up. Without delay we get to unloading our canoes and gear onto the lawn by the boat ramp. We’ll be serving in two Old Towns on this day, a Penobscot and a Camper, both classics.

We set off under overcast skies just before 8:00, ready to bash some trash. The Old Town Boys consist of myself, Cig Man Tim, and Branson, old friends and fellow paddlers. Last year we picked up 17 tires. This year we’re on a stretch farther downstream, drifting beneath towering sycamores and sprawling Texas ash trees, bringing up the rear of a loose flotilla of Trash Bash vessels. The event spans a total of 26 miles, from Austin to Webberville. Since 2018, hundreds of volunteers have cleaned more than 60 tons of trash out of this section of the Lower Colorado.

We paddle along and prowl among invasive water hyacinth and overhanging hardwoods, eyes peeled for floating plastic, disintegrating styrofoam, vulcanized rubber hiding under the surface. We collect some here and there, but there isn’t much. Just to fill a bag and boost morale Cig Man breaks protocol and exits his craft, climbing up on the bank where some domestic refuse lies scattered. Clothes, shoes, blankets. He holds up a used diaper with his grabber.

“I think it’s just got pee in it!” he calls out to us.

But something eerie is going on in the water: hardly any trash. Has the event been so successful over the years that little refuse remains? Are people finally learning that you Don’t Mess With Texas, and properly disposing of their waste?

Then we find the gyre. The river channel splits in two around a very large island, and an eddy beneath a willow tree has collected a human lifetime’s worth of garbage. Plastic bottles of all shapes and

sizes, grocery bags, textiles, coolers, food wrappers, noodle cups, sandals, liquor bottles, aluminum cans. Bonding it all together is a kind of loose sludge of mushy, disintegrating, everlasting styrofoam. Not far away a water moccasin slides through the shallows and up into a hole on the muddy bank.

We tie off our canoes and attack the trash, wading thigh-deep into the mire with bags and grabbers in hand. We are surrounded by garbage on all sides, in the very thick of it. It’s like the Star Wars trash compactor scene. Branson is Skywalker, Cig Man is Solo, and I am Chewbacca, writhing around and groaning incomprehensibly. There is no Princess Leia. Plastic bottles are everywhere. It’s powdered Gatorade from here on out for me, I swear to myself. We are inundated, subsumed, assimilated. We have become the trash.

But we persevere and methodically pick away, keeping an eye out for sharp things — the formidable fangs of certain snakes, hypodermic needles. We are determined that this eddy under the willow is returned to its natural state as a largemouth bass hole, as it must have been in the days before the trash gyre. The Old Town Boys fill bag after bag, 1015 in total, and after an hour or so the bulk of the refuse is gone.

As we drift downstream with our haul and slide past the tail of the island, we see a skiff jetting upriver towards us. It’s Alvin and his crew. The founder of All Water Guides and organizer of the Trash Bash stands tall at the tiller like a messiah, a savior, suffused with warm October sunshine. He might be the best fly angler in this entire great

state. People line up to fish with him. He has his own popper bug bearing his name. Legend has it he can catch two Guadalupe Bass with one cast, no dropper. I believe it.

They motor up alongside us and relieve us of our burden, loading our bags of trash onto their skiff to run back down to the takeout. They let us know there’s an overturned boat hull just downstream. People have been talking about extracting it all day, but the task has yet to be accomplished. We’ve heard rumors of this particular hazard up and down the river ourselves. So it’s true. The Old Town Boys are on it. They thank us for our service and jet away.

It’s not long before we come upon the target on river left. Indeed, a tethered vessel has capsized. We wade into the muddy shallows and try to flip it, but soon discover the deck has separated from the hull and is submerged in the muck,

and that’s what we keep tripping over. There’s also a sizable outboard motor still mounted on the transom, and the cables running between it, the deck, and the hull are holding everything together, making a morass of it all. A skiff putters up, and some fellow Bashers hop out to assist. They are two brothers and a son. The dad plays country music of the Red Dirt variety. The son sounds like he’d rather be fishing than trying to pull some old busted boat out of the mud. The other guy assumes an air of impatient superiority, as if neither his brother nor nephew are endowed with the same manliness and general knowledge about everything that he himself possesses. On his shoulder blade is a lone, shitty tattoo of a Confederate flag with “Dixie” written in script over it. Faded as it is, perhaps it’s a regrettable decision from his younger days. Or maybe it’s the badge of a lifelong moron.

After Cig Man saws away at the steering cables for a while with only a dull razor knife like some jailhouse escapee, we get the deck detached from the hull. The five of us can now overturn the boat if we heave hard enough. In the process a minnow nibbles on one Dixie’s nipples, upsetting his poise, and he flails about for a moment, describing the power and size of the aggressor. Finally the hull sits right side up, a beautiful sight. We bail it out, plug some drains and bilge holes, and declare it seaworthy enough for a tow in. We watch as the Dixie Skiff tugs the fiberglass shell downriver, barely afloat. They said it couldn’t be done, but here stand the Old Town Boys, muddy and proud.

We arrive at the takeout ramp at Big Webberville park around 3:00, the afternoon sun hot and bright. We unload and haul our canoes up out of the water and make for the pavilion where the afterparty is going down. A big crowd sits at picnic tables in the shade, eating grilled sausages and drinking cold beer. There is tens of thousands of dollars worth of Yeti gear and other products staged on a table, waiting to be raffled off. We pull on our complementary Howler Bros Trash Bash edition mesh caps and listen up as Alvin takes the microphone to address the congregation.

The first thing he does after thanking the volunteers is give remembrance to his late wife, Lenee, whose birthday it would’ve been. She was a major part of organizing the annual LoCo Trash Bash, and an accomplished fly angler herself. I had the good fortune to fish with her some years ago and in a few hours she put my brother and me on more fish than

we usually find in a year. Alvin tells us the event is dedicated to her, and that she would be proud.

The raffle begins and prizes are doled out. The Old Town Boys watch from the back, having a cold one and chatting with folks. There’s old Gibson, slurping one down. We were awarded a couple of extra raffle tickets for our efforts in removing the sunken skiff, and it pays off, each of us winning some gear. After the raffle ends and the crowd disperses I catch up with Alvin. We’ve never formally met and I introduce myself. I tell him I’m from Southern Culture on the Fly, sort of, here to write a story on the event, and he smiles big. He likes those dudes.

“Let me know if you need a quote or anything,” he says.

“I will!” I say. What a guy.

By Cola

When the Toccoa ran too warm, the South’s anglers discovered that “community” isn’t just about fish, it’s about how we live together when the water turns against us.

This may register with our attuned readers as a departure from my usual gonzo storytelling, but every now and then we trade whiskey and weirdness for a bit of journalism. After speaking with a handful of folks about the early October TVA/ Blue Ridge kerfuffle over sluicing at the Blue Ridge Dam, I found myself circling a bigger question: what do we really mean when we talk about community?

That word gets tossed around plenty — we’ve got strong feelings about our bonds as Southern anglers — but we rarely stop to consider how fractured, even contradictory, those bonds can be. This essay proposes there isn’t just one SCOF community, but a constellation of them: ecological, economic, and emotional. Each is tugged in a different direction by the complicated modern South in which we fish.

The Dam, the Flow, and the Flip IIf you’ve ever stood below a dam, you’ve felt it — that low, concrete hum of control, turbines whirring beneath your boots, the water churning like an argument between God and man. That’s the tailrace, the stretch of river immediately below a dam, where what we call “release schedules” determine everything from trout survival to weekend plans.

Tailrace dams are how the Tennessee Valley Authority electrifies our lives, keeps our lawns green, and occasionally reminds us who’s boss. Water stored in the reservoir is released through turbines to generate power before it spills back downstream. Simple enough. But when the TVA needs to move sediment, replace a generator, or avoid bottom draw for maintenance, they switch to a different mode: sluicing.

Sluicing sounds technical, but it’s really just the controlled dumping of surface water through gates or spillways instead of pulling it from the cold, oxygen-rich depths. Picture it this way: instead of drawing from the refrigerator, they’re pouring from the bathtub. That’s fine when you’re trying to keep turbines clean, but downstream, where the trout live, it’s the difference between life and a slow poach.

And here’s where it gets tricky. Every autumn, Southern reservoirs “flip.” In the summer, the lake layers itself like a parfait, warm, oxygen-starved water on top (the epilimnion) and cold, oxygenpacked water below (the hypolimnion). When fall air cools the surface, that top layer grows heavy and sinks, mixing the whole water column. The lake turns over,

the temperature evens out, and that dependable stash of cold water used to feed tailraces disappears.

Now imagine TVA sluicing during that turnover, warm surface water, low oxygen, pouring into a tailrace built for coldwater trout. You don’t need a degree in ecology to guess what happens next: fish kills, stress, confusion, guides canceling trips, and a ripple of anger that spreads faster than the current itself.

The Blue Ridge Dam incident revealed not one community, but several overlapping, competing, and sometimes loving the same river for different reasons. Anglers, guides, small business owners, Chamber of Commerce boosters, TVA engineers, and yes, the trout themselves, all depend on the same fragile equilibrium.

Critical theorist Raymond Williams called this tangled web a structure of feeling, a living mood that ties together people and place even when their interests diverge. Philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy might say it’s being-in-common — that what binds us isn’t harmony, but our shared exposure to vulnerability. And as Zygmunt Bauman warned, “community” often glows with nostalgia, a word we cling to when the water runs too warm and the world feels out of tune.

That longing surfaces in Blue Ridge every time the thermometer spikes and the river smells faintly of decay. Guides talk about fish kills like they’re funerals. TVA employees — many of them anglers themselves — wrestle with the irony of their day jobs destroying the thing that brings them peace.

The South has always been a place where contradictions coexist, revival tents beside strip clubs, conservationists driving diesel trucks. The Toccoa crisis just gave that duality a new face, a trout gasping downstream while the turbine hums on upstream.

“Sometimes when trolls talk, the internet listens,”

My first call was to a TVA employee who’s a friend of the magazine, an angler, and a man who asked to stay anonymous. He started with the basics: the generator at Blue Ridge Dam was shot, federal funding was on the line, and if they didn’t act soon, those dollars might vanish. The issue, he said, wasn’t just ecological, it was bureaucratic, a matter of timing and paperwork. He reminded me that TVA’s founding mission under FDR wasn’t about recreation at all. It was about electrifying the rural South, taming floods, and modernizing the region. Trout weren’t even an afterthought back then. “Recreation came later,” he told me, “an accident that worked out pretty damn well for the fishing industry.”

He pushed back on some of the outrage. Without sluicing, he argued, the river wouldn’t have trout at all. He also pointed out something guides rarely mention: kayakers and rafters outnumber anglers by a mile, and they’re organized, vocal, and backed by tourism dollars. “The problem isn’t the water,” he said. “It’s that anglers troll TVA on Instagram instead of organizing like paddlers do.”

Before hanging up, he offered one more piece of practical heresy, “If you guide up here, you can’t be a one-trick pony. When the trout bite’s off, pivot to bass. Adapt.”

Cohutta guide Austin McDonald doesn’t buy that adaptation is so simple. “Trout are the gateway drug,” he told me. “They’re how people fall in love with fly fishing. Take that away and you lose the spark that feeds everything else — bass, redfish, tarpon. It all starts with trout.”

Austin still can’t believe their grassroots push actually moved TVA. “They never give us real-time water temps,” he said. “They just tell us when they’re sluicing.”

After social media pressure led by @ outdoorswithcape, TVA broke its silence, releasing temperature data, lowering flows from 500 to 350 CFS, and letting cooler night air do its work.

“Sometimes when trolls talk, the internet listens,” Austin laughed. The campaign even pulled in the Georgia Department of Natural Resources to take their own readings, and local landowner Wes Brock logged two weeks of independent data. “We were bridging a communication gap that’s usually deafeningly silent,” Austin said. He also mended fences with the Blue Ridge Chamber of Commerce after an initially “nasty” email exchange. “Christy Gribble thought I was a jerk,” he admitted, “but after Shannon Oyster vouched for me, we figured out we were on the same side.”

Together they leveraged the chamber’s influence to get the TVA’s attention. “Maybe because I’m a dad now,” Austin said, “it hit different — seeing people rally for the future.”

The Veteran’s Memory Guide Chase Pritchett, who’s been rowing the Toccoa since before hashtags existed, remembers the last crisis a decade ago — the pinstock repair year. Flows dropped to 60 CFS, fish died by the hundreds, and the local economy tanked. “That year changed everything,” he said. “A lot of guides left for the Hooch or South Holston. I couldn’t.”

To Chase, this year’s kerfuffle feels different. “Back then everyone was just surviving. Now you’ve got Drew, Austin, Ben — guys who used to compete — working together. Sometimes it takes a near-disaster to remind you what community really means.”

When I asked Austin for final thoughts, he laughed, then got quiet. “What’s going to come out of this,” he said, “is education, communication, and community, for this amazing bass fishery, where trout are still king.”

It felt like a small epiphany. Maybe the South’s survival — ecological, cultural, spiritual — depends less on purity than on flexibility. The TVA, the guides, the trout, the chamber moms, the bureaucrats, all of us are bound to the same current. Even the water seems to remind us: you can’t stop the turnover, you can only learn to ride it.

by Kendall Mayers barkeep at The

When Henry Ford first started mass production of the Model T in 1908, he was rumored to have said “you can have any color you want, as long as it’s black.” Now, I’m no Henry Ford. I’m just a bartender with a fishing problem, but when it comes to making cocktails, I do have a similar stance: you can use any liquor you want, as long as its bourbon. Lucky for us, we’re living in the bourbon revolution.

Wherever you are in the country, you shouldn’t have to go far to find a decent bottle. I usually stick with Buffalo Trace, but use your favorite. As painful as it is for me to admit, the bourbon you use for this particular recipe won’t necessarily be the star of the show. That honor belongs to the holy grail of bacon –Benton’s bacon from Madisonville, Tennessee. Now I’d like to believe this particular publication attracts the type

2 oz. bacon fat washed bourbon

1 oz. Cinnamon Simple Syrup

1 oz. maple syrup

2-3 drops vanilla extract

Combine all ingredients in a glass with ice and stir for 30 seconds. Strain over one large ice cube or sphere, and garnish with an orange peel.

of distinguished renaissance man who needs no introduction to the finest of salted and smoked meats on the planet, but if for some reason Benton’s bacon is unfamiliar to you, I would like to remind you that it is now 2025 – you can order bacon in the mail. Get on it.