Our Father in Heaven, Rock and Redeemer of Israel, bless the State of Israel, the first manifestation of the approach of our redemption. Shield it with Your loving kindness, envelop it in Your peace, and bestow Your light and truth upon its leaders, ministers, and advisors, and grace them with Your good counsel. Strengthen the hands of those who defend our holy land, grant them deliverance, and adorn them in a mantle of victory. Ordain peace in the land and grant its inhabitants eternal happiness.

Lead them, swiftly and upright, to Your city Zion and to Jerusalem, the abode of Your Name, as is written in the Torah of Your servant Moses: “Even if your outcasts are at the ends of

the world, from there the Lord your God will gather you, from there He will fetch you. And the Lord your God will bring you to the land that your fathers possessed, and you shall possess it; and He will make you more prosperous and more numerous than your fathers.” Draw our hearts together to revere and venerate Your name and to observe all the precepts of Your Torah, and send us quickly the Messiah son of David, agent of Your vindication, to redeem those who await Your deliverance.

Manifest yourself in the splendor of Your boldness before the eyes of all inhabitants of Your world, and may everyone endowed with a soul afrm that the Lord, God of Israel, is king and his dominion is absolute. Amen forevermore.

The buses and carpools are gone from the curb. Students have packed up the contents of their lockers and teachers have lef for the summer, but the Stein Circle Campus is anything but empty and the ha l s are anything but quiet. Architects and construction personnel fl the building and the sounds of hammers and heavy equipment permeate the air.

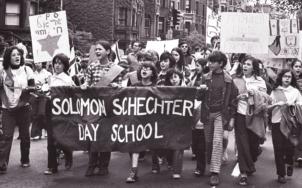

Since Schechter’s founding in 1961, the school has undergone many physical changes from moving to di ferent facilities as we have grown, to establishing ourselves in our permanent homes at 60 Stein Circle and 125 We l s Avenue in 1978 and 1994, respectively. The most recent major renovation to the Stein Circle Campus was in 2000-2001, and the We l s Avenue Campus was last updated in 2007-2008.

We are embarking now on a major undertaking that is so much more than just breaking down wa l s and recon fguring classrooms. We learn and gather and teach and live di ferently today from how we did a decade ago, let alone a generation ago. To that end, this is a grand reimagining of our needs and dreams, and our educational and communal spaces. We are also planning for Schechter’s unique and growing role as not only a school, but an increasing hub in the Boston Jewish community.

In the fa l/winter issue of Schechter Stories, we shared the extraordinary news that Schechter is one of fve Jewish day schools in North America to have been chosen by the Ronald S. Lauder Foundation to help ignite and broaden young family engagement in Jewish life. Through vibrant communal activities, creative partnerships with local Jewish

organizations and grassroots work to envelop young Jewish families, Schechter is poised to grow our enrol ment from the ground up. We are proud to be the place in which so many families experience the diversity and richness of Jewish life and learning, and the joy and strength that comes from being together.

By the spring of 2027 when construction is complete, we wi l have doubled capacity for our early childhood program to be able to welcome 160 students from ages 15 months through Pre-Kindergarten. Our third-grade classrooms wi l be newly located on the We l s Avenue Campus and the space formerly housing our preschool wi l be completely revamped as a STEAM Center with art and music studios, fexible design spaces and science labs.

To lead the school I once atended through this breathtaking next phase is a profound responsibility and exhilarating process. With the steady and passionate dedication of Judy Flad as the project manager, and the indispensable input and col aboration of our faculty and sta f, we wi l move through this work from a place of sure footing and solid experience.

As with everything in life, we do not know exactly where this wi l a l go, but we are as con fdent, iterative and col aborative as always. This is the ride of a generation and it’s thri l ing.

Rebecca Lurie, Head of School

spring/summer 2025

Growing Community

Writing

Stephanie Fine Maroun AP ’09, ’11, ’12, ’14

Assistant Director of Admission

Contributing Photographers

Heidi Aaronson ’96, AP ’24, CP ’27

Gary Alpert

Ted Borgman, Bright Spot Film

Diana Levine CP ’27, ’30

Stephanie Fine Maroun

Aviram Shahal CP ’27, ’30, ’34

Design Joel Sadagursky

Printing Puritan Capital

We have made every efort to ensure accuracy. Please contact schechterstories@ssdsboston.org.

Prof les illumination: ariela housman ’99 master plan: ben schwartz ’14 the golden compass: eran hornick ’02

2024 arnold zar-kessler

38–45 grandparents and special visitors day a tribute to yakov dov schechter archiving project 32–37

outstanding alumni award: benjamin kasdan ’06 the grade 8 all-hebrew play: seussical, the musical israel study tour

46–49

Class Notes

Schechter Soccer

Jamie Zeitler, School Operations Coordinator, scanned 13,524 photos over the course of the 2024-2025 school year to create Schechter's first digital archive. Decades of school history and institutional memory are now catalogued, labeled and easily accessible. See more pictures from the archive on page 42.

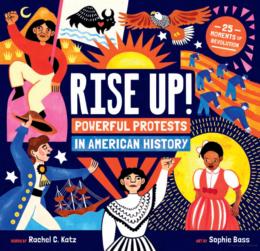

Kindergarten teacher Emily Beck has been awarded a prestigious Covenant Foundation grant of $20,000 to develop a new curriculum for Pre-Kindergarten through Grade 1 focused on initiating and guiding students to have Sicha Amitza (courageous conversations). The Covenant Foundation focuses on supporting Jewish educators in Jewish schools, community organizations and other institutional settings to develop and launch education programs and curriculum that can potentially be used in other settings.

While there are plentiful resources to support older students in having challenging

conversations, there are insufcient curricula that provide Jewish content and materials for younger students. The Sicha Amitza project includes templates for asking questions such as How did this book make you feel? What would you do in this situation? Through practice, students become more comfortable contributing to discussions about important topics such as identity, community, diversity and fairness.

Emily shares, “Our new curriculum will be anchored in read-alouds and will expand on the existing Courageous Conversations curriculum which I co-created with a Federal Teacher Leadership Grant, for the Boston Public Schools during the 2019-2020

school year. The lesson routine also includes opportunities to make connections: Have you ever had an experience similar to the character in the story? How can what we learned from this book help us work together to support our community?

Under Emily’s leadership, the Sicha Amitza Project will harness age-appropriate Jewish and general literature to help foster curiosity, active listening, and social-emotional learning. Building the skills of respectful dialogue and thoughtful interactions at the earliest ages in a child’s development is core to Schechter’s belief that our students are ready to tackle big ideas at young ages in the safe environment of our classrooms.

The Schechter community fulfilled the mitzvah of Ma’ot Chitim by collecting 308 boxes of matzah for Jewish Family and Children’s Services to support families in need of help for Pesach.

The Power of Purim In the life of a Jewish day school, there are many cherished holiday celebrations and sustaining traditions, but perhaps Purim reigns

supreme. From the daily dose of fun and imagination during Spirit Week beforehand— Monochrome Day! Sports Day! Fancy Day!— there was also a Megillah reading for Grades

4-8 led by students and teachers alike on Purim. Thirdgraders designed and ran the Lower School carnival for the first time, creating homemade booths, games and cchallenges for the

enjoyment of our younger students. Our littlest costumed students at Gan Shelanu delighted in the fun of wearing their favorite dress-up outfits from home at school.

Israel is far, but it is near to our hearts at Schechter every day. In a poignant tribute to the Bibas family whose love of Batman will forever remain a symbol of lost joy and a family rent asunder, the Schechter community dressed in Batman shirts and gear on the day before Purim. Even if our youngest students were not aware of the exact inspiration for Batman Day, the chance to impersonate a superhero is never lost on anyone and channeling our best selves is an important message every day.

No Limit to Beter. There has never been a time in our school’s history when we did not have big ideas or grand plans for our program and our future.

From its inception in 1961 with fve students to our enrol ment of 475 today, when our preschool has a waitlist and many of our grades are fu l, we have the courage and self-con fdence to dream big. And bigger.

schechter’s motto of “No Limit to Better” is a constant tool of self-assessment. It is an energizing reminder and a critical touchstone: Are we doing enough? How can we improve? How can we expand our role in the Boston Jewish landscape in the way families want? How can we fix whatever is not working as it should? How can we be everything our students deserve and need? How can we keep growing?

Schechter Boston is flourishing. We are one year into our work with the Ronald S. Lauder Foundation, one of five Jewish day schools in North America selected to pioneer and pilot bold initiatives to grow Jewish day school enrollment. Under the auspices of the Lauder Impact Initiative (LII) and our LII Steering Committee, we have been given the financial and intellectual support to marry our own expertise and imagination with the successful models and outcomes of the Lauder Foundation’s work in Europe to revitalize Jewish communal activity and involvement. Tapping into timely research on the thought processes of young Jewish families as they make life decisions around education and community is helping us chart this course not only for ourselves, but for other Jewish day schools and communities.

We believe in קזחתנו קזח קזח (from strength to strength). It is from this place of strength that we have laid the groundwork for doubling our early childhood program which is the cornerstone of growing Schechter’s enrollment. We embrace this worthy challenge at a time the Jewish community needs to stay resilient in the face of of-the-charts antisemitism. The joys and lightness of Jewish life and learning, of communal strength and connection, will always sustain us.

Sure, there will be some noise and dust, but creativity, problem-solving and building are the best kind of messy. No crystal ball or time travel can inform us now if this bold venture will have worked, but we believe that the future of the Jewish community needs what we do.

REMODEL, RETHINK, REIMAGINE

This is so much more than breaking down wals and changing where things are.

AN

As we begin construction this summer, Schechter’s leadership team is focused on both the physical recon fguration of classrooms and our facilities as wel as optimizing and remaking the way we learn through creating fresh multi-purpose spaces, reimagined learning communities and the complete redesign of parts of both campuses.

The Stein Circle Campus wi l house our Early Childhood Program which includes Gan Shelanu (ages 15 months to Pre-Kindergarten) through Grade 2. Our Intermediate Division wi l gain Grade 3 as it moves from the Lower School building to the Wel s Avenue Campus, joining Grades 4-5, and our Middle Division which is composed of Grades 6-8.

Schechter Stories sat down with Dr. Jonah Hassenfeld, Director of Learning and Teaching, to hear about the developmental, social and programmatic benefts behind this work.

How is this major construction going to change the way we teach, learn and gather at Schechter? What are the core goals in creating learning communities? Students and teachers form closer relationships when the classroom designs and building

spaces refect how we want to use them programmatica ly. Having Gan Shelanu on the same campus as Kindergarten a lows for a much smoother transition. It cultivates a sense of safety and security to have an integrated program from 15 months through Grade 2 in which the facility is designed speci fca ly for that age group. We inherited the space that Gan Shelanu currently occupies and we are actua ly constrained by its layout. The construction wi l provide opportunities for open-ended free play, fexible movement and groupings. We get to design the space intentiona ly to promote kids being able to make choices for activities.

Can you share some examples of newly designed spaces?

One idea is to create an atelier space at the Lower School which is basica ly where special items and art materials are stored, displayed and maintained for shared use.

In the new STEAM Center on the Wel s Avenue Campus, we can rea ly lean into the fact that people learn in new ways. For example, there are very few contexts in which a student must sit by themselves to write. That doesn’t mean

that writing isn’t important, but instead that we have to make sure a student can encounter a question or a problem and be able to draw on a wide range of interdisciplinary perspectives to respond or come up with a design solution.

Moving Grade 3 to the Wells Avenue Campus is a big change. Why is this an important shift in divisions?

We are a place where we make human beings. Every student is an individual, but there are developmental and educational reasons why Kindergarten through Grade 2 is its own time of life. Foundational ski l s like literacy and numeracy at this age unlock a l of our future learning. At the same time, emotional development and understanding how to be part of a community is a key focus through Grade 2. How do I f nd my place? How do I solve a minor con f ict?

Broadly speaking, there is a big transition that happens from Grade 2 to Grade 3. Students start developing much more sophisticated executive functioning ski l s. Third-graders need to manage more things at the same time such as planning out longer term writing projects which is an order of magnitude that is very di ferent from second grade.

We’ve talked for a long time about the social/ emotional level of most third-graders by the middle of the year. There is a growth and uptick in their social dynamics that goes along with the intelectual development. They are beginning to need a larger landscape than our Stein Circle Campus. So at the same time they might be holding more numbers in their head for a math problem than they did in second grade, they are also starting to fgure out how they are situated in the world in a way that they could not do the year before. Most second-graders have very dyadic friend relationships like two poles, basica ly twosomes. Third-graders are becoming part of groups and navigating the realm of being with more than one person socia ly at the same time. Third-graders are genera ly more aligned academica ly, cognitively and socia ly, and are dealing with similar types of questions more akin to fourth- and ff h-graders.

Why did you decide to group each division into these grades and what impact will that have on students and teachers?

The symmetry of each division having three grades is a nice change while also lining up beter with where kids are in their development. This rea ly

The school is kind, warm and grounded in a wonderful philosophy of teaching. We have found an amazing community here.

ben

parent of

in grades 6, 4 and kindergarten

a lows us to create a more distinct character for each division. I do not believe in one-size-ftsa l developmental progressions, but when we consider our facility and our curriculum, having a streamlined Early Childhood Program on one campus wi l be an important change for our teachers since Gan Shelanu is currently separated from Pre-Kindergarten and Kindergarten. In addition, this move brings Pre-Kindergarten back under the umbrela of Gan Shelanu.

What type of learning community is the Middle School?

There is another leap in complexity from ff h grade to sixth grade. Kids have shorter and longer term projects and the executive function demand jumps. In ff h grade, most kids are squarely rooted in family life, but in Middle School, kids are shi f ing some part of their focus to friends. They are developing their capacity to navigate the world more independently. Middle School is a pathway to adulthood.

People usually think of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) rather than adding the A for Art. Why is the A critical?

There is a joke in education that if you add the A in, isn’t STEAM everything then? Doesn’t it cancel itself out if it’s everything? I get this question a l the time and it’s interesting because STEAM is a design orientation. If you are trying to create a functional pot in a ceramics class or design a computer program or answer a physics question, a l these problems share a quality: they are amenable to being solved by design. So, the idea of a creation center, or a STEAM Center, is that the ceramic studio and the science lab, is that these are a l di ferent modalities and we believe in teaching kids how to be designers, engineers and artists.

Think about a sof ware company. You have the back end and the front end. There are people who are designing the graphic user interface who have to talk to the people who are building the back end database. Through this investment in STEAM, we're acknowledging that this is where the world is, and we're also excited about it, and we want to make sure that our kids get practice bringing together these di ferent things and being able to design and create.

The faculty and sta f are extremely keyed in to each and every student and demonstrate their expertise through caring, warm and supportive practices, ensuring every student has the opportunity to succeed and cultivate a love of learning. The community is truly special and we feel lucky to be a part of it.

brina parent of students in grades 1 and preschool

Why is this the direction we are choosing?

Schechter has long dreamed of a single campus housing our entire program. We have come to realize that as our school grows, the time has come to embrace fully and finally a two-campus model by maximizing and revitalizing our two campuses, both of which ofer multiple, flexible options for redesign. Delivering an exceptional student experience remains our driving goal at Schechter. Our student community is broadly diverse from age to learning style to interests, and will be better served by two campuses whose identities and footprints are clearly and strategically delineated.

Our future is as bright as our students. A cornerstone of our program, Gan Shelanu has reached capacity, with waitlists for toddler classes every year. With more than 75 percent of our Pre-Kindergarten students continuing into Kindergarten, it is clear that Schechter provides the loving and vibrant foundation for learning and community that so many young Jewish families seek. As we double the size of Gan Shelanu, we will be able to open our doors to more families than ever before, meeting the needs of the Jewish community and ensuring sustainable enrollment growth for Schechter.

At the same time, our oldest students will have the physical space and state-of-the-art equipment to build robots, craft pottery and push boundaries in our new STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art and math) Center on the Wells Avenue Campus.

Classes will continue, learning will go on and we will remain on our campuses as the project unfolds. How are we doing this?

Spring 2025

• Finalization of designs and permitting.

Summer 2025

• Targeted construction begins at the Stein Circle Campus to ensure that all students have appropriate learning spaces during the 2025-2026 school year.

Fall 2025

• Construction will be underway on the first floor classroom wing of the Stein Circle Campus. Kindergarten-Grade 3 classes will take place on the second floor and Pre-Kindergarten classes will take place in the back wing of the first floor.

Summer/Fall 2026

• Grand opening of expanded Early Childhood Center on the first floor of the Stein Circle Campus.

• Construction begins on the Wells Avenue Campus STEAM Center in the space formerly held by Gan Shelanu.

• Grade 3 joins the Upper Elementary Division with Grades 4 and 5 at the Wells Avenue Campus.

Spring–Fall 2027

• Grand opening of the STEAM Center.

As our campuses undergo construction, we will simultaneously streamline and improve our program as well as day-to-day logistics. Key areas include:

Program Enhancement

During the quiet phase of our capital campaign, we raised over $10.4 million for this project. We express tremendous gratitude to our earliest supporters. As we launch our public phase this fall, we look forward eagerly to bringing the broader community into this exciting renovation.

We will expand innovative learning opportunities including STEAM initiatives, experiential learning and exploration, and interdisciplinary projects to equip our students with the skills, creativity and critical thinking needed to thrive in a rapidly evolving world.

School Operations

We will fine-tune school logistics to make the two-campus experience as smooth and seamless as possible for families and students.

Talent Management

We will continue investing in the recruitment, retention and professional development of top-tier educators to bring our vision to life.

Our new facilities will be coupled with redefining our academic structure in four learning communities. This regrouping will allow our teaching teams to focus more deeply on cross-curricular educational and developmental opportunities in order to augment the student experience.

• In Early Childhood, we will expand and relocate Gan Shelanu to our Stein Circle Campus. We will double the size of our Early Childhood Program (15 months through Pre-Kindergarten) over the next three years, renovating the first floor of the Stein Circle Campus to house 14 early-learning classrooms and create communityoriented indoor and outdoor spaces for all of our students.

Early Elementary: Kindergarten-Grade 2

• In Early Elementary, we will enhance the Stein Circle Campus second-floor classroom spaces to allow for focused classroom learning and community building experiences.

Upper Elementary: Grades 3-5

• In Upper Elementary, we will relocate Grade 3 to the Wells Avenue Campus to join Grades 4 and 5, creating an Upper Elementary (Grades 3-5) community on the first floor.

Middle School: Grades 6-8

• In Middle School, the second floor will continue to house Grades 6-8. We plan to transform the current Gan Shelanu space in the Wells Avenue Campus into a dynamic Maker/ STEAM hub for innovation and exploration for our Upper Elementary and Middle School students.

One of the most interesting learning communities at Schechter, one that transcends grade level and defes neat defnitions, is that of the STEAM Center. It is a public square at school, a crossroads for science, technology, engineering, art and math, and also a meeting place for minds, ideas and creations that develop so rapidly and electrifyingly that we sometimes just have to stand back, watch what our students can do and simply be there to assist them.

First, everyone does STEAM, so to speak, because STEAM is everything. Certainly, there are devoted groups of students who frequent the makerspace to tinker, work on a design project or convene for the LEGO robotics league. Any number of projects in progress are carefu ly stowed on shelves with polite “Please Do Not Touch” signs taped to them. Plenty of foor space in the makerspace is impassible as other creations set or dry or wait for a student’s return.

What we have known for some time is that our students’ imaginations are limited only by the con fnes of our current makerspace at the Wels Avenue Campus. As we ready ourselves for the construction of a new STEAM center, we eagerly await its opening in the spring of 2027 when our facility “catches up” with the potential of our students.

Penina and Amanda are in a position many educators would envy. For the f rst time, Schechter’s active makerspace, extraordinary arts program and Intermediate Division science lab wi l be more than neighbors on the same f rst-foor ha lway. They wi l form the basis of our new leading edge STEAM Center. Construction begins in the fa l of 2027 a fer Gan Shelanu moves to its expanded and redesigned space at Stein Circle. Along with school coleagues, architects, contractors and engineers, Penina and Amanda are knee-deep in conceiving and planning a creative hub that refects a l that we value as a school and, even more speci fca ly, a Jewish community.

“Penina and I talk about this a lot,” Amanda says with a smile and energy that refects the magnitude of this opportunity. “We have a lot of goals for this space in order to create an environment that lets kids blend a l of their ideas. These new classrooms should mirror how easily kids code switch between art and science or drawing and using textile. It’s not that we want kids to be profcient in a l of these ski l s. We want them to have a space they can run to between classes or come in during a STEAM block or lunch and do whatever is top of mind for them. I want a place where the answer is always ‘yes.’”

Penina concurs. “We want to move from this concept of having classes and classrooms to a space that is about the students and their dreams. We don’t create by divvying up di ferent types of rooms. That’s not how we imagine or design. It’s about a l kinds of resources from tools to equipment to the adults who are there to help kids make what they want. The goal is that the STEAM Center is fexible enough to accommodate whatever kids need in the moment.”

Visits to community artist colectives, schools and other self-described creative wonderlands such as MassArt in Boston and the Artists Asylum in Somervi le have ofered rich, fertile examples of inclusive communities in which makers can access resources, beneft from mentorship and training or experimentation.

Projects do not always folow linear paths and those proverbial “creative juices” ofen fow unpredictably.

“Rather than a 3D printer on a countertop,” shares Penina, “we envision a digital design center with green room technology, woodworking, an outdoor

learning space, computers and sof ware for photo editing, laser cut ing and 3D printing. When you cook, for instance, you do not always need your fancy mixer, but it’s right there if you have to use it. We would like an artistic environment with a l the art studio tools and a science environment that has a l the science lab tools, but for everything to be part of a central hub surrounded by classrooms where kids can gravitate.”

The goal is that the STEAM Center is flexible enough to accommodate whatever kids need in the moment.

penina magid

Amanda notes that while some tools and equipment might be siloed—the kiln wi l be housed in the art room and woodshop tools wi l remain in a safe zone, for instance—the students’ ideas are“democratized.” She explains, “We don’t want kids to walk in and feel as if they need credentials or special access to use anything or ‘go behind that door’ or pu l up a chair ‘over there.’ Everything is unlimited as long as you folow protocols and procedures.”

While there wi l sti l be art class or science in the traditional way we understand a scheduled period during a school day, Penina and Amanda are doubling down on the concept that students be able to come into the STEAM Center to create whatever they want from the ground up. “We a l might have di ferent ideas about how this might look, in the end, we are a l commited to this vision of a space that harnesses kids’ excitement. We see what happens a fer school or during free periods or enrichment blocks when kids are self-motivated and enthusiastic about a question they want to solve. We want that to be possible a l the time.”

Penina adds that envisioning an open-ended space, stocked with supplies, equipment and porous disciplinary boundaries, refects Schechter’s values. They describe a format in which a grade can begin with a mini lesson, then break out individua ly, each student being able to access whatever they need to learn and progress, make mistakes and move forward. Schechter’s “fail forward” spirit and embrace of risk-taking, among faculty and students alike, is rife for such a concept.

“Right now, it’s frustrating because the kids have big, amazing ideas and visions that are way beyond what we can even fathom as adults, but also beyond what our current spaces a low,” Amanda says. “We simply have a physical bot leneck in our extant makerspace. The biggest problem is that there are too many kids who cannot f nd a tool or need just a

We want them to have a space they can run to between classes or come in during a STEAM block or lunch and do whatever is top of mind for them. I want a place where the answer is always ‘yes.’

amanda strawhacker

We made a last-minute pivot from public school to Jewish day school for Kindergarten and we couldn't be happier with Schechter! The school environment is warm and nurturing, the teachers take a deep interest in the children, and the community is supportive and wonderful. We’ve decided to send a l three of our children to Schechter.

irene parent of student

in grade 1

lit le bit of help to f x something broken or who could code on their own with a lit le bit of direction, but the room is too sma l and limited for a l of that to happen.”

We always return to a guiding principle that the Schechter experience must be relevant and personal to each student.

Amanda has thought deeply about the complexity of designing a makerspace for a Jewish day school. “I keep coming back to this dichotomy that we are raising kids to be bearers of an ancient tradition that every student carries within themselves and wrestles with and f nds meaning in di ferently. We have an opportunity here, especia ly in these creative design spaces, for kids to use our history and heritage in solving problems that are only going to be unique to them and their generation.”

Penina continues, adding that we teach our students about ti k un olam and their responsibility in the world in the face of daunting problems that require even more complex solutions. “Students have the capacity to respond to real-life cha lenges. One mark of success is that we bring Jewish tradition into our work because it helps us in the blending of art and repair and problem-solving. Another mark of success would be that students have the chance to work with community members who can ofer expertise or training.”

Amanda ofers the example of ancient agricultural practices outlined in the Torah that can be used to build a community garden or learn about cycles of ecology. “We spend so much time thinking about Israel, but what if we also thought about Israel as a point on this planet that is interconnected to the rest of the world. Perhaps we come up with a design that is distinctly Jewish and marked by our culture of Judaism that helps the planet.”

What would that idea be? “I have no idea,” says Amanda. “The kids haven’t invented it yet.”

Honoring a teacher with a gi f to the Annual Campaign highlights the impact of the sacred work we do at Schechter each and every day as we grow the Jewish leaders of today and tomorrow. Scan the code below or visit ssdsboston.org/give.

an interview with :

Ariela is a soferet—a scribe—responsible for adhering to a rigorous Halakhic process, working in quiet, focused solitude to write sifrei kodesh (holy scrolls). To see Ariela‘s work is to see ink strokes that go from feathery to bold, thin to thick, delicately frilled to solidly straight. Each stroke of her quill leaps of the parchment, each Hebrew letter a precise, miniature creation whose perfection is required. The lines and columns of Torah that Ariela handwrites are a window to our ancient tradition’s past and a mirror to an unbroken history that continues to this day, crafted painstakingly at Ariela’s very modern drafting table.

A fellow scribe whom Ariela knows was once asked if being a sofer is like being a prophet. “My first reaction to such a question was to be incredulous and maybe even a little flippant,” Ariela recounts. “I’m not a prophet and have never been one. I suspect there is this idea that scribes spend their days in a mystical state of elevation. That’s not possible, but the more I thought about it, the more I thought it was a really interesting comparison.”

She continues, “The job of the Prophet was to convey God's words, not their own, as precisely as possible, but the Prophets brought their personalities and gloss into

what they did. Most of the job, though, is to get out of the way. It's an abnegation of self. You are not the point, you are not the star. I feel as if writing the Torah is the same thing. I want people to look at my work and see a lovely Torah, but my calligraphy is not what makes it special. It’s the content.”

the start of it all was learning calligraphy with Art Teacher Joy Chertow in fifth grade. “I remember being aware of calligraphy, but it was instant love when I first tried it,” Ariela reminisces. “I got a calligraphy set from my parents that year. When I began preparing for my Bat Mitzvah the next year, I made my own invitations. I went through a period of being very embarrassed by them, but now, looking back at them, I am quite fond of what I made.”

In 2024, Ariela finished a grand, multi-year project for Temple Beth Shalom in Needham, namely her first commission to write an entire sefer Torah. “My classmates used to say that I could never make a living doing art. Well, sorry guys, you were wrong,” she laughs. At first, though, Ariela did not work in the art world and she had even decided against going to art school. “I was reluctant to discover that working in art stole the joy from it.”

Fans of science fiction and fantasy will chuckle at Ariela’s analogy that she kept “refusing the call.” She jokes, “You know, the hero is summoned for a mission and rejects it. Ultimately, they yield to the call and go of to fulfill their quest. I was the one ignoring the call.”

Ariela often turns to a truth she has come to realize. “I was the only person in my life who was surprised I became a scribe. From a young age, I was in love with Judaism and in love with calligraphy. What more obvious way is there to express both of those loves than to be a scribe? At first, I didn't know that was a thing you could do. I was blessed with extremely supportive parents. My mother encouraged me to take the time to foster my creativity and kept telling me I could make it work. I got here with the help of the village and with the help of God.”

as a senior in high school at Gann Academy, still the New Jewish High School at that time, Ariela’s grade was unable to spend the third trimester in Israel because of the Second Intifada. An internship with famed ketubah artist Mickie Caspi proved to be more than just a worthy stand-in for the canceled Israel trip. Ariela describes "a felicity of timing" learning to write ketubot at the

You can't be a productive person without containing multitudes. It’s important to recognize that scientific, technical, mathematical and creative thinking all inspire each other.

beginning of the wedding season. At the end of her internship she was gifted a set of pens and invited to return for a summer job.

The technology for printing ketubot has changed dramatically, Ariela explains. “I was doing mostly fill-in work. Most ketubot were mass-produced with a design, then the rest of the text and names had to be added in matching calligraphy by hand. It just wasn’t economical to custom print every single ketubah, so they would order 500 to 1,000 ketubot, then fill them in as they processed orders.”

Ariela remains grateful to the calligraphy training she received, but perhaps even more to the business know-how and professionalism she acquired under Mickie Caspi and her husband and business partner, Eran Caspi. “Many of my peers are artists as a satellite business, but I was thinking about how to structure a calligraphy career from the ground up.” To this day, Ariela depends on her business partner, Terri Ash. “I am making the art, but Terri is the one who's making things go. I believe firmly in recognizing the importance of administrative work even if it is not the glamorous frontfacing work most people see.”

With a B.A. in history from the University of Pennsylvania, Ariela segued into her first post-college job at the Penn Museum in 2007. The museum was digitizing one of its collections as a trial run for a larger project. Ariela was hired for her art experience, but her supervisors soon discovered that she had a knack for “translating English to English,” as she says, between the archivists and the IT Department.

Ariela was initially expected to do postproduction work on photos of Native American objects and art soon to be repatriated under NAGPRA, the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which protects and returns Native American human remains, sacred objects and cultural works to lineal descendants, Indian Tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations. Her role quickly shifted as curators struggled to communicate their needs to the tech department who, in turn, struggled to explain what their computer programs could efectuate.

“They were talking right past each other,” Ariela recalls. “It was often a case of completely diferent professional jargon, though actually conceptualizations of the same goal. The archivists were thinking of the

physical object, category tags, the experience the user will have searching for images. The IT folks are thinking about the data model, how to cross-reference tags. I just happened to be someone who had both of those models in my head.” Ariela stayed for a year, then it was time to pivot. She spent a year in a Torah Lishma program at The Conservative Yeshiva. “I wanted to immerse myself in Jewish learning. I had never taken a gap year and it felt like an opportune time because nothing was tying me down.”

on paper, Ariela says, she is a good match for the Conservative movement, but the lived reality can feel diferent, and difcult, for her. “I am traditionally observant, shomeret Shabbat, shomeret kashrut, I daven frequently. My father studied at Pardes, so this idea of a personal, independent commitment to Judaism is very much part of my family. While I don’t consider myself Orthodox, I’m part of a partnership minyan because there is a vanishingly small number of places where you can find egalitarian values and the degree of traditional, Halakhic observance that I find necessary to my life.”

Post yeshiva in 2009, Ariela was interviewing for jobs—“just throwing pasta at the walls to see what would stick”—when she was

hired by the Union of Reform Judaism(URJ), where she stayed until 2021. “I can hold complex systems in my head,” explains Ariela, which was well suited for cleaning up system bugs and reforming the technical aspects within URJ’s email marketing and communications department. The stability of the job ofered the luxury of continuing her art outside of work hours.

“I started doing ketubot from scratch, some custom calligraphy and art work.” Ariela found the juxtaposition between the random personalization of a ketubah and the halakhic requirements to be alternately challenging and amusing. Couples requested ketubah themes that reflected their lives— crossword puzzles, Star Wars or Star Trek fandom, steampunk or the location of a proposal to name a few!—for which Ariela would design a beautiful and cohesive document.

Ariela relished the quirky requests so much that she created Geek Calligraphy in 2016 for which she has been nominated three times for a Hugo Award, an annual literary award for the best science fiction or fantasy works. “I love the playfulness and absurdist humor behind incorporating beautiful text and very unexpected images.”

When I first started out, 10 lines a day was a triumph. At this point, I consider 42 lines, which is a column, to be a standard work day. I have to get in the zone.

Already a professional calligrapher for 12 years, Ariela enrolled in a mezuzah writing class, tackling the most strenuous category of a scribe’s work. “It’s not because mezuzot are small which is the most common misconception. They have to be written Halakhically ksidran (in order) which means every letter must follow the next. If you make a mistake, you have to catch it immediately. Otherwise, anything you write after the mistake is not kosher. Sometimes, it’s possible to scrape of an error with a scalpel, refinish the parchment and keep going. If you have written the name of God, you are not allowed to erase it so all your work goes straight to the geniza. That level of pressure is not for beginners.” Scribes make a verbal declaration to demonstrate that they intend to write for the sanctity of the text, then each word is said out loud before being written.

“Even in the privacy of my studio, I say it audibly,” Ariela shares. “Most people choose Megillat Esther for their first project because the name of God is never mentioned.”

In October 2021, a colleague connected Ariela with Temple Beth Shalom in Needham, thus launching an exhilarating and daunting three-year project. She adds that the synagogue was invested in the fact that this

was her first Torah scroll, and ofered her enormous support.

Ariela employs the Spanish Portuguese style in part to salvage it from extinction, but also because it is extremely readable.

“Temple Beth Shalom is not a Sephardic synagogue, but they found my scribal hand to be very recognizable for people who are used to reading in print rather than the more standard Ktav Arizal. As communication increases, the globe shrinks. There is a lot of flattening of regional customs. Torah script has changed dramatically over time and space. The idea that there is one right way to form the letters has no historical basis.”

Some days the task was easy, some days more taxing. “It was and is a huge cognitive load and learning process on more multiple vectors than I anticipated. When I first started out, 10 lines a day was a triumph. At this point, I consider 42 lines, which is a column, to be a standard work day. I have to get in the zone.”

During the project, Ariela put her personal art on hold, contributing to “an embarrassing backlog of mezuzot” owed to clients. Eventually, she would like to write another Torah, especially with her acquired wisdom

and experience, but for now she deploys her artistry on repair work for sacred texts which is “much less glamorous,” as Ariela says, but critically important to maintenance. Ariela also speaks frequently in schools and synagogues about the process of being a scribe.

Inevitably, Ariela is asked how she became a scribe. Her path is not as linear as the systematic, methodical words and lines that flow from the tip of her quill. “How one becomes a scribe and how I got here are two diferent things. I had so much technical experience that I worked backwards by taking a crash course on Halakhah. I also had to practice transitioning from metal pen nibs and paper to parchment and quills, and mastering the diferent properties because it’s a very diferent physical exercise to write with such traditional instruments.”

Ariela shatters any ideas about dividing art and creativity from science and math. “I have a very mathematical brain. I love puzzles and logic. I love reading and thinking. Calligraphy is a very mathy art. There is no ‘one side of the brain.’ For a very long time, I had a career in a fairly technical field that enhanced my skills as an artist. You can't be a productive person without containing multitudes.

ariela, left, and business partner terri ash

It’s important to recognize that scientific, technical, mathematical and creative thinking all inspire each other.”

the complexity of Ariela’s opus is second only to its beauty. Safrut, the practice of scribing, is as formulaic as math and as demanding as decoding Talmud. It is simultaneously about embellishing while conforming, yet the soferet’s output is as purely unique as any artist’s work. The finished piece is preordained as the sofer or soferet is a purveyor of God’s words, but the scribe’s influence on a scroll’s style and the delicate rendering of each Hebrew letter is quietly, powerfully present without interfering.

Ariela’s relationship to Judaism and to God and to her art are serious, treasured and contemplative. “I have been blessed with the talents for this momentous undertaking, but it is an immense responsibility. There are many things that render a Torah unkosher that do not even show, but depend on the integrity of the scribe. I feel the intensity of the faith placed in me by a synagogue or a client. I’m not burdened, but I feel the weight of it. It’s grounding.”

an interview with:

Conjure up a Middle School social studies class: map projects, dioramas, history and civics lessons, the rudiments of sociology. To hear Ben describe his social studies major at Harvard, imagine all this at the undergraduate level—minus the shoebox dioramas, of course—as an interdisciplinary course of study encompassing political science, statistics, economics, design and high level sociology. “It’s a little bit all over the place, but a well-worn major,” Ben quips, and in his case the most straightforward approach to studying issues around afordable housing and urban planning.

In a way, everything is social studies. Now at Columbia University Ben is working towards an M.S. in Urban Planning which he describes as a “deliberately amorphous choice.” Ben got here by compiling an array of professional and volunteer experience, coursework, even hands-on construction, all to tackle the labyrinthine challenge of afordable housing development and access. He lists other parallel degrees that miss the mark for him. “If I enrolled in a real estate development program, I would be studying real estate finance, law and development, for example.” Urban planning coursework, however, allows for a plethora of focus areas from design to transportation to zoning.

“It’s very broad which was attractive to me because I don’t want to be pigeonholed in my career,” Ben shares. “I will get hard skills wherever I work, but I want a holistic understanding of these issues beyond

numbers on a page. Some aspects of planning are technical like when I learned how to use geospatial software to make detailed maps. I also enrolled in real estate classes, so I am studying finance and real estate law, but urban planning is flexible which is what drew me in just like social studies did as an undergraduate.”

ben recounts his years after Schechter. “I went to Newton North High School, then did a year of national service in AmeriCorps before starting college. I spent 10 months traveling around the western United States doing everything from rebuilding afordable housing to clearing land in a Redwood Forest to help mitigate forest fires to filing people's income taxes in Montana, which might sound kind of dull, but actually is the work I found most impactful.”

At Harvard, Ben pieced together the disparate but intertwined classes he would need to complete his social studies major as a sort of relevant proxy for a nonexistent undergraduate major in urban planning. He enrolled in graduate level courses at the Graduate School of Design at Harvard where the Urban Planning program is housed. “I took a second year of from school after my sophomore year during which I worked full time for the city of Boston as a data analyst in the Boston Planning and Development Agency,” Ben shares. “I worked alongside a lot of planners which convinced me to follow this path.”

long before Ben was ofering tax help or toiling in national parks, his trajectory was forming. “I am influenced by my personal set of values and interests, and also my religious values,” Ben explains. “I see my career as a form of tikkun olam. Being Jewish is central to my identity and how I view the world. This is my little way of helping to repair the world which was a value instilled in me at Schechter and also at Camp Ramah in Palmer. The thing I appreciate most about Schechter is that I have the tools now as an adult to engage with Judaism meaningfully and be fully comfortable in any environment.” During this tumultuous period of political divide in the United States and a rise in antisemitism, Ben draws comfort and strength from being “tethered to the Jewish community.”

Ben’s methods for tackling housing shortages are anything but textbook as evidenced by his inventive DIY learning style. Amidst power tools, sawdust and safety goggles, Ben acquired an array of real-world skills in Newton North’s top notch carpentry program. “I was interested in the physical aspects of construction, so I stayed in the program all four years of high school, then worked for a residential contractor in Newton one summer.”

In the decade and a half since Ben’s family moved from New Jersey to the house where they still live near Heartbreak Hill the neighborhood has completely changed, Ben reflects. “I was becoming increasingly aware

that the area had been unattainable even for a comfortable family like mine. In college, I began writing papers about afordable housing production. I interviewed a lot of city councillors because I was very bothered by the trend.”

Ben describes the confluence of his interests in construction and his watchful observation of housing prices and new developments as another defining motivation for him. All at once, Ben says, he could see the small, then bustling advancement of demographic and socioeconomic forces in the streets and neighborhoods around him. For six years during school breaks, he picked up extra money working for a moving company. The stark disparities in income and housing prices were plain to see as Ben loaded and unloaded furniture and belongings into people’s homes all over the Boston area.

he explains. “My fundamental argument is that if the government were deliberate and exercised the foresight to set aside enough afordable housing in a community before it gentrifies, the gentrification could be an imperfect tool for integration. A South End townhouse costs millions of dollars now, but the neighborhood is still extremely diverse by income and race because 40 percent of the housing there is permanently afordable. The South End may appear integrated on paper, but living in the same neighborhood does not mean people actually interact with each other meaningfully in their daily lives.”

Subsidized, afordable housing is often misunderstood, Ben notes. He points to the lack of supply as the most critical, persistent issue, but adds that he is sympathetic to crowding and congestion. “It is diferent from town to town, development to development, but if Newton built 500 new units on an

This is my lit le way of helping to repair the world which was a value insti led in me at Schechter and also at Camp Ramah in Palmer.

“I became compulsively interested in housing prices,” Ben notes. “My senior thesis at Harvard was an investigation designed to ask whether gentrification could serve as a mechanism for integration by race and class using two Boston neighborhoods as case studies: the South End and East Boston. I wanted to complicate the discussion around gentrification as not being purely good or bad. We live in such a segregated society. People talk about moving people to the suburbs from the city, but that doesn’t happen at scale on its own. The reverse happens all the time with no intervention. I was curious if this could be a real solution to integration.”

Ben arrived at an answer he found deeply unsatisfying: maybe. “It is very nuanced,”

empty lot, the increased tax revenue would be far greater than the cost of providing seats in schools and extra water.”

Concurrently, Newton public schools face declining enrollment while costs such as electricity, heating and cooling, and maintenance are fixed. School funding is allocated per pupil at the state level, forcing the city to consider alternate means of filling seats such as busing students from other cities to Newton, Ben details. “It is these sorts of complicated demographic issues that lead to school closures and funding cuts in cities and towns.”

Restrictive zoning is one of the most formidable culprits and roadblocks. “For

example,” Ben says, “if you go to Brighton near Soldiers Field Road, there are new multifamily developments going up everywhere because Brighton is one of the few areas of Boston that is zoned for multi-family housing even if there had not been that sort of housing there before.”

Ben lists another hindrance. “If empty big box stores were rezoned, a developer would snatch them up and build housing, but rezoning is extremely contentious because of concerns around increased trafc or fewer parking spots, who will live in the housing, and whether new construction will create shadows or block views.”

“nothing is simple, ” Ben states. “ But I want to dispel an extremely common misconception. People usually think of afordable housing as ‘the projects’ which have a very bad reputation for a variety

reading torah at harvard chabad for my friend's bar mitzvah ceremony • (l-r): ben schwartz ’14 with friends alex feldman, ben leikind, alex crystal ’14 and ben’s friend, aj, from high school

of reasons that often have to do with government mismanagement.” With both wistfulness and frustration in his voice he adds, “This image of public housing is what people think is being constructed for new afordable housing, but it’s completely diferent. The United States is singular among developed countries for not investing to provide housing that its citizens can access, and there is little appetite for it.”

Income eligibility is calculated by the median income in a particular area, Ben explains. “Let’s say the median income in Newton is $100,000. If I set aside 20 units for people who are only making 60 percent of that, it’s $60,000 a year which is middle class and still out of reach for people earning 10 percent

of the median.” Ben believes that creating housing for people earning 10 percent of the median alone is not ideal either. “There are a host of reasons why it’s better to have a range of people living in developments together. One of the reasons public housing is such a failure in the United States is because it became a housing of last resort. It plays an important role because millions of people would be homeless without it, but these are often environments of concentrated poverty and disadvantage that are outside the control of the residents and that weaken their ability to improve their situation.”

Supply is another pervasive misconception, Ben adds. Shiny new developments filled with $3,000 per month apartments may not appear to be a solution, but are actually an indicator of the staggering lack of housing. “If the rich cannot find enough housing, where are the middle class going to live? Where are

the poorer people going to live? No one is building for them.” Nevertheless, according to Ben, increasing the supply of housing even by building “luxury” units is still an important step in the afordable housing crisis in Boston and the country at large.

Ben ofers the fascinating example of Vienna, Austria, a major city that has tackled and managed housing issues well. “The Viennese city government builds housing, not just for poor people, but for middle class people. It's completely normal to live in subsidized government housing. The program required a lot of initial upfront investment decades ago when it began, but now is financially selfsustaining. Government housing takes up a

large share of the private market which keeps pricing very competitive. With high quality public housing, private rents are significantly lower and units must be exceptional to be worth renting or buying.”

Ben is realistic about the possibility of major changes. “It’s an invitation to roll up my sleeves, not throw up my hands. I’m pragmatic. I have ideals, but I am not an idealist. No one can fix this alone, but we can chip away at this problem, try to inspire others to address these critical social issues, and build a better understanding of what we can accomplish. I’m just going to do what I can, which makes this work all the more meaningful.”

this summer, Ben will intern at Strada Ventures, a real estate development company that consults with afordable housing developers. While Ben’s title of

income thresholds. “Most government aid programs in the United States are structured through the tax codes. When low income families file their taxes, especially if they have children, that is how they qualify for government benefits. This can be the diference between making a month’s rent or not. Typically, I file 50 to 80 people’s taxes a year.”

will it be hammer in hand? Pencil to paper? There are many tools, many drafts and plans, and no single answer to housing shortages, but anything is possible which is key to Ben’s ethos. Literal and figurative scafolding needs to be constructed to pave the way for development as unremitting factors contribute to housing issues that only seem to cycle repetitively, worsening each year.

“intern” appears straightforward, the role actually entails just the sort of complex and comprehensive approach he believes will best address this exigent problem. “I could not have dreamt up a better position for myself because Strada Ventures is made up of people who have worked either at afordable housing developers or in relevant city agencies in New York. They work with clients on every stage of the development process from securing and underwriting loans, setting up contracts and meeting contractors, to managing completed assets.”

Through Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA), a national program run by the IRS, Ben will also continue to help people file income tax returns if they meet certain

Yet, for every roof that shelters a family, for each new building that opens up to a broader range of occupants, Ben counts a win. A critical win, however small in the face of the problem’s scale, is immeasurable to the family who now has a place to call home. Ben’s most efective tools are determination, a nuanced and grounded perspective, and a persistent commitment to tikkun olam, all more durable, more versatile, and more limitless than the roadblocks he faces.

If anyone can nail this, Ben can.

an interview with:

Eran has amassed a long list of teachers who inspired him as a writer and a reader from Schechter to Gann Academy to Brown University. All these years later, now a teacher himself, Eran continues to draw from the inefaceable impressions left by those teachers. Gentle guidance, a thoughtful concession or knowing recognition of Eran’s aptitude were the wise and steady directionals that shaped him.

“I recall making books in Kindergarten and writing journal entries and, later, creative pieces about Jewish thought in middle school when I had Rabbi Victor Reinstein as a teacher,” Eran shares. “I ran into him about 10 years ago and he remembered my writing. He’s just one example of a person who helped me find myself as a writer earlier than I even realized and whom I try to emulate to this day.”

Eran thinks back to his seventh-grade Language Arts teacher Donna Cover who allowed him to pull out The Golden Compass when the rest of the class was reading The Pearl “There were many teachers who meant a lot to me. Sometimes I struggled with not wanting to be told what to do, but Mrs. Cover found a way for me to engage.” Eran says he remains moved by her astute understanding

that flexibility was not a capitulation, but rather a way to win Eran’s attention.

“I never expected to be on this side of the education system,” reflects Eran. “And yet so much of my career has included pieces of teaching.” While an undergraduate student at Brown University—with a major in Creative Nonfiction Writing—Eran taught Hebrew school, Hebrew language and youth education classes in Jewish thought at a synagogue near campus in Providence. “One of my Hebrew school students accepted my ofer of Hebrew tutoring which eventually helped her place out of the first level of Hebrew in college.”

Eran also nabbed some side work as an SAT tutor. “I interacted with students of diferent ages and it just clicked. They could feel that I was on their side. There is such joy seeing the moment a student says, ‘Oh, I get it!’ Eventually, I won’t be needed, which is the whole point. For years, friends and family had told me, ‘Eran, you’re a good teacher. Maybe this is something you’re meant to do.’”

in 2021, Eran learned of a job opening through a college friend from Window Rock, Arizona, the capital of the Navajo Nation, which spans large portions of New

There is such joy seeing the moment a student says, ‘Oh, I get it!’ Eventually, I won’t be needed, which is the whole point.

Mexico, Arizona and Utah. Eran was eager to experience a diferent part of the country and quickly accepted the ofer to teach ACT and college prep at Wingate High School. Eran shares, “Many colleges have actually moved away from requiring the ACT, especially in the Four Corners (Utah, Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico), which is fortunate since I don’t believe the tests are an accurate reflection of a student and are typically geared towards financially privileged populations.”

As a tribal school, Wingate falls under the Bureau of Indian Education which is overseen by the Bureau of Indian Afairs in the Department of the Interior. All students are Native American, though like so many young generations do not speak Navajo as fluently as their parents or grandparents. Despite this, Eran explains the Navajo language continues to survive even with such erosion. “Centuries of persecution and increasing technology like TikTok have created so much distance between earlier traditions and this generation. Students complete at least two years of Navajo language class at school.”

“Older generations try to keep the language alive,” Eran adds. “Many of the senior teachers at Wingate speak it fluently. I hear them chatting and joking with each other in the hallways. The youngest of my colleagues who is fluent is in his 40s, and there are a few students who speak Navajo as well, but it’s increasingly rare.” Eran remarks on the similarities between his great-grandparents, who spoke Yiddish as their first language, learning English later in life, followed by his grandparents, who turned to Yiddish only when they didn’t want his parents to understand, and now to Eran, who knows only a few phrases and precious tidbits.

When Eran first came to Wingate, he focused on acclimating to classroom teaching and developing his comportment in front of a group of students. “I like tutoring one-on-one more than teaching in the classroom setting,

but there is a big advantage to the classroom since it gives me the opportunity to get to know all of our students, and to meet them early on in their high school careers,” Eran shares.

Now, four years later, Eran has added a literature course to his roster and runs a student magazine. “At the beginning, I didn't have the bandwidth to think about a literary magazine, which is something I had participated in at Gann and Brown, and loved. I certainly enjoy helping students with math, but it’s not as close to my heart as literature and writing. We’ve produced three volumes so far. It is incredibly rewarding to these students to see their work in a bound, published volume.”

The “litmag”—to use Eran’s hip and loving jargon for the publication—is not only an impressive showcase for student talent, but a vehicle to connect with kids and potentially kindle an underlying, untapped skill. “If I notice a kid doodling during their tutoring hours, I say, ‘Hey, you should come to litmag. We need more artists like you.’ I catch them in their artistry and try to nurture and find space for it.”

Eran believes that truly seeing and discovering the spark in each student comes from demonstrating appreciation of their individuality and making them feel valued. “Sometimes a student won’t open up to the material we’re covering in class. I tell them to draw. I would rather them be engaged in some way rather than completely checked out. I see the efectiveness of this approach because many of my more disengaged students came around when I ofered them a diferent avenue to express themselves. If they’re not engaged, if they don’t feel recognized and respected, all my ACT and college prep material is pointless.”

In its inception, the magazine had half a dozen members of whom just a few would participate each week. The core group

of student contributors—from writers to artists—has grown to a committed 15. “It’s fantastic to see that none of my core litmag students are in my actual classes. A freshman I noticed drawing during study hall is now our strongest member. Most of our core group are friends he has invited.”

it is always top of mind for Eran to approach his interactions from a place of learning and respect. At first, he felt shy about discussing Native issues with his students. Eran’s college friend who had connected him with the position, herself a member of the Navajo Nation, encouraged him. “She told me that it would mean a lot to the students to hear afrmation coming from an outsider.” Eran credits this colleague with forming the central maxim of his teaching philosophy: “More than anything, these kids need to know that there’s an adult who cares about them, who believes in them. Everything else will follow.”

Eran recalls a student drawing for the litmag of a wendigo, a supernatural being that is part of Native American folklore. The magazine was nearing completion, so Eran consulted the student about the drawing’s placement. “Is it acceptable to put this picture in a spot that matches artistically, but perhaps not thematically? I want to make sure nothing is mistakenly ofensive.”

Eran strives to run his classes from a point that synthesizes Native sensibilities with preparation for post-secondary school life. He explains, “The idea of a resume breaks a cultural norm for my students since, in Navajo tradition, people are taught not to sing their own praises. So, we reframe a resume as showcasing and highlighting one’s well-earned skills as opposed to just inflated boasting. I tell my students, ‘We’re doing this because in order to have the kinds of jobs that will make you feel good about yourselves, you’re going to need a resume. You deserve to be recognized for your skills, and this is how we do that. Some of the

I’m grateful that my students and fellow teachers have welcomed me here. I’m a guest, being invited to partake in these students’ growth, and the fact that so many people share their traditional creation stories and songs with me is an honor. I may be a guest, but when I walk down our school’s halls, I’m greeted with a sea of smiles.

experiences you’ve had may not seem like they belong on a resume, but so much of what you do is worthwhile and applicable in a professional setting. Your skills are your unique contribution to the world, and when you’re proud of yourself others will see that, too.’”

Growing up, Eran’s father exposed him to some Native culture and history, yet after four years living on the Navajo Nation Eran sees how much more there is to know. “I’m grateful that my students and fellow teachers have welcomed me here. I’m a guest, being invited to partake in these students’ growth, and the fact that so many people share their traditional creation stories and songs with me is an honor. I may be a guest, but when I walk down our school’s halls, I’m greeted with a sea of smiles.”

Eran feels a sense of kinship and finds parallels between the Navajo and Jewish cultures such as the decline of respective languages as well as traditions such as B’nei Mitzvah and Kinaaldá, the Navajo comingof-age ceremony for girls. “I tell my students about my traditions, and want them to know that our respective histories—Native and Jewish—share so many similarities and yet sparkle with their own inimitable richness.”

Eran recounts how his students were mesmerized when he wrote their names on the board in Hebrew. Wingate students have had virtually no exposure to Judaism or preconceived ideas of Jews, which has been positive and soul-bearing. “I share about the holidays I take of. I sing Hebrew and Yiddish songs to them. It’s a privilege that my kids show curiosity, and a joy to share our varied yet relatable cultures.”

symbolic hoop, which we label socioeconomic hurdles, racial biases or being a first-generation college student. Then we start to increase the hoop size again, and talk about how Navajo culture is thriving. We talk about mentorship because when these students have someone who cares about them, the hoops begin to crumble and disappear. They have incredibly stalwart family units, and with that support, the backing of their mentors at school and their own resilience, they realize the myriad of hoops everyone faces are surmountable.”

Eran recounts how some of his graduated students have had to leave college for various financial or family reasons, and yet he feels hopeful. “When I see how resilient and future-minded these kids are, I find myself with a renewed faith in humanity. I tell my students that I get naches from them. I tell them they keep me going.”

Eran holds on to the thank you notes he has received from graduates as they reafrm for him his eforts to make his students feel known have been a success.

I remember the first day I transferred in, and I didn't know anyone, and you made me feel really welcome. I'll never forget that.

Mr. Hornick, you always put a smile on even when you were having a hard day.

These are cherished words for Eran, words that speak to his students’ hardwon accomplishments and his profound admiration for them. Long after Eran’s students graduate Wingate and leave his class, when each student’s compass is pointed in a diferent direction and they must navigate the world on their own, he hopes that these future leaders will remember not only that Mr. Hornick believed in me, but will go forth sustained by the feeling I believe in myself

a classroom game called “Opportunity Basketball” serves as a metaphor for life. Eran’s students toss crumpled pieces of paper into a box and, with each round, the aperture of the box is progressively narrowed. “It gets harder and harder to pass through each

The Arnold Zar-Kessler Award is presented to a Schechter alumna/us each year who embodies Schechter’s values in their professional, academic and/or volunteer roles.

Benjamin Kasdan is an HIV advisor working at the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in Kyiv, Ukraine. He has previously worked on HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 programming in Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mozambique, Vietnam, Namibia, South Africa and Tanzania.

Before starting at USAID, Ben worked with International Planned Parenthood Federation on their sexual and reproductive health in crisis and post-crisis settings projects in Bangkok, Thailand. He also worked at an NGO in Tanzania, supporting their capacity building program for maternal and newborn healthcare.

Ben received a B.A. from George Washington University in International Relations and his M.P.H. in Global Health with a concentration in Maternal and Child Health from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Everyday Americans resoundingly believe that foreign aid is a net positive for the country, and that the U.S. is a force for good in the world. USAID work benefts American farmers and local businesses as wel who provide essential food and other services to those in need around the world.

How do you hope your current work in Ukraine will have an impact?

After two years in Ethiopia, I got the opportunity to come to Ukraine. People ask me about this choice—my first night, there was a ballistic missile attack—but there is no better place to be right now for someone working in U.S. foreign policy. Why wouldn’t you want to be working on some of the greatest challenges of our time?

The U.S. government is the largest organization working on behalf of HIV/ AIDS in Ukraine. As the HIV Advisor, I oversee $10 million dollars worth of funding. Our focus is on testing to ensure that people who are living with HIV have access to tests. HIV is no longer a death sentence, but people don’t always know where to start or they don’t have a support system.

Since the start of the war in Ukraine, there has been increased mobilization of the population because of military conscription or people being forced to relocate. Every year, we try to figure out what the denominator is in any country: how many people in the country are living with HIV? Ukraine has the largest burden of HIV in Europe, outside of Russia. I believe the numbers have scaled up, but we won’t have a full picture until after the war with people flooding into places like Poland and Germany. There also has not been a census since the start of the war.

What happens next for you?

Up until this year, USAID was at the forefront of development activities and global health activities around the world. As of July 1, the government is moving to close down USAID which was created by an act of Congress under President Kennedy. It cannot just be closed without congressional approval. People can say that

we are withdrawing the funding because Americans don’t benefit from USAID, but disease knows no border.

Do you want to continue working for the government?

I have invested a lot into this career and I want to stay in health-adjacent programming. People who get into this line of work are motivated by national service. With USAID, U.S. taxpayers have directly contributed to millions of people being alive who would have died if they had not received treatment or prevention for HIV. We have the numbers to prove it and not many other countries can say that. If possible, I would like to continue public service, work for an NGO, or find a job in the private sector that is focused on health care.

Do you feel hopeful?

Yes, I do. Everyday Americans resoundingly believe that foreign aid is a net positive for the country, and that the U.S. is a force for good in the world. USAID work benefits American farmers and local businesses as well who provide essential food and other services to those in need around the world. This is also such a fascinating time to think about the world with a critical eye, and to consider how perspectives in development and foreign policy are not working.

What makes you the most proud about your Schechter education?

When I was in Ethiopia, I attended a nationally televised meeting about HIV. I walk into the meeting room and it's full-on cameras, lights, everything. I thought back to our Schechter play days when I was on stage for Bye Bye Birdie in eighth grade: well, I did a whole play in Hebrew, so I can do this in English.

I also remember social studies at Schechter. We were talking about current events

and we would review key news articles weekly for homework, but what we were really learning about was integrity, being a good and decent human being. I think it's important to think about what are your values as an American, as a citizen of the world, as a Jew, and then live by those.

How does your Jewish identity play a part in your life and work?

I've engaged in Jewish communities all over the world in unique ways because Jewish representation is diferent all over the world. I was in Mozambique for a work trip, and I walked into a synagogue for Kabbalat Shabbat. It was all Mozambicans who just love the music, about three Jews, and a Catholic priest. The Catholic priest had never been to Kabbalat Shabbat and he loved it. That's what Judaism looks like when you're overseas.

The whole ethos of tikkun olam, repairing the world and leaving it better than we found it, is very important to me. As the agency closes down here in Kyiv, I still want to make sure I live each day with integrity. If I can do that, I will not look back on my short period here and feel that I could have been a better person.

Eighth-graders charmed and entertained two packed and adoring audiences with the fantastical fun of Seussical, this year’s Grade 8 All-Hebrew Play. As much as this musical is known for the trademark white and red striped hats, rollicking rhymes and fanciful characters, it is equally the story of friendship, believing in oneself and the importance of every single unique individual in a community. Could any storyline be more Schechter?

Under Director and Choreographer Ashlee Benner, Music Director Aaron Newitt, Producers Penina Magid and Rebecca Finkelstein and with a playful translation of the script into Hebrew by Neta Schwartz, Seussical elicited plenty of laughter, cheers and whoops from the audience while reinforcing serious and abiding life lessons that benefit us all.

As Horton himself says in Horton Hears a Who, “Each person’s a person no matter how small.” Schechter is a Whoville of sorts, an entire world unto itself that lives and breathes and flourishes every day from the smallest of our community members to the oldest.

April 21–May 7, 2025

Crisscrossing time and place, past and present, this year’s Israel Study Tour was defined, as always, by Schechter’s unwavering commitment to Zionism. For some students, this is a first trip to Israel, for others it is a chance to visit Israel again in a new way. For all the students and chaperones, it is a unique experience to be together learning, reflecting, observing and just being in the moment.