IMPERMANANCE

SPRING 2024

Nature’s first green is gold, Her hardest hue to hold. Her early leaf’s a flower; But only so an hour. Then leaf subsides to leaf. So Eden sank to grief, So dawn goes down to day. Nothing gold can stay.

Dear Readers,

-

When we began working on this issue, we very quickly became drawn to the subject of change. An unavoidable part of life, reliable in its inevitably, change appears in small and large doses. A broad subject with room for interpretation, we call this issue Impermanence, translating its essence into our issue through a seasonal perspective. Divided into four sections—summer, fall, winter, and spring—Impermanence offers an anchor for our content, an aid for interpretation.

Beginning with summer, we open this issue with an emulation of life, mature and comfortable. We wanted to open with summer for various reasons. First, as undergraduates, summer acts as a transitionary period between college years. But, full of life, sun, and freedom, the season also feels fulfilling. Jasmin Jin’s article “Fragments Reborn” introduces impermanence through used and disregarded objects, acknowledging their once pristine quality despite their decay. Placed in summer, amid artworks like George Stoica’s Coastline and Svetlana Stepanova’s Gazing Upon King Street, the article sets the tone of the issue, embracing the present while acknowledging its inevitable loss to history.

Fall brings a stark change. The stability and comfort of summer give way to the structured routine of the school year as leaves, once an array of vibrant greens, turn to a golden hue. The season symbolizes the inevitable change brought by the passing of time. The shock of a transition

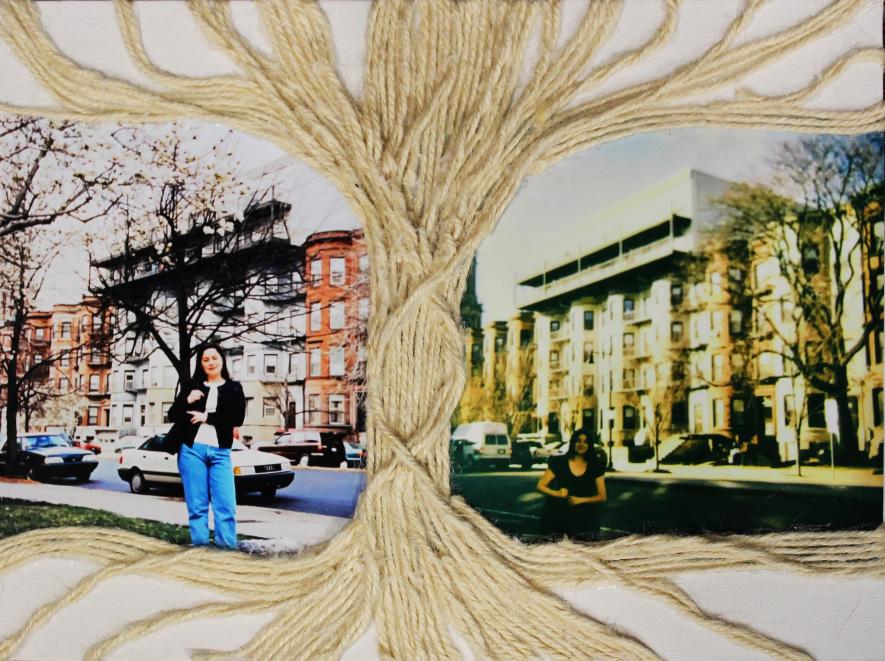

triggers reflection. Emma Claire Everett’s article “Connecting Two Collections from Panopticon Gallery’s ‘First Look’ Exhibition” reflects on collections from the Panopticon Gallery in Boston by artists who reflect on trauma and childhood. But although the fall brings an inescapable change, life continues. Sara Sierra-Garcia’s multimedia piece, 30 Years, shows the same woman in the same location 30 years apart. Romy Binstein shows the comfort still present through transitions in I Made You Tea, part of her series, “Stains of Life.”

Winter turns deadly. The stark cold air and dead trees feel alien to the lush greenery of months before. Change has come as even the most resilient begin their decay. Alexander Gee’s photograph #22 captures a serene yet isolating scene, while Lauren Boysa captures her battle to remain present despite the bitter cold brought by winter in her oil painting, Doorway. Offering an interview with Boysa, writer Berrett Walsh provides a glimpse into the artist’s relationship between artistic creation and temporal pressure.

Finally, spring arrives, bringing with it a sense of renewal, a fresh start. Though different from before, life presents us with new opportunities, priorities, and challenges. Spring reminds us that although nothing lasts forever, even the most daunting change can serve as a catalyst for growth and transformation. Anna Novick captures nature’s perseverance and rebirth in her oil painting, Juxtaposition. Similarly, Elena Jordan’s Spring embraces the inevitable rebirth after death.

I opened this letter with a poem by Robert Frost, “Nothing Gold Can Stay.” In only a few lines, Frost says more than I ever could, allowing others to expand upon his observations of love and loss. In my last semester at Boston University, I leave with an extreme sense of pride over what Squinch has become. Since our revival in 2022, we have become a complete collective. This issue comes to you from the hands of every member in Squinch, amalgamates and unifies our vision to embrace the present. Although sad to leave the community Squinch has become, I will forever remember the work and bonds it brought. I go with gratitude as I hand the publication off to the next generation.

Squinch Magazine Editor-in-Chief, 2024

Summertime, as the sun rises, I walk down the Costa Rican shoreline. I watch the waves come and go as the ocean stretches my gaze. The mind wanders out onto the horizon and later onto a canvas as this moment in time takes shape. Colors and brushstrokes are utilized to form waves as I feel the sunlight. I try to grasp that old sense of summer bliss that I so miss.

Xinyue Jin

My mother, guided by her love of collecting, once plastered a whole refrigerator with photos and souvenirs from places she traveled to accompany her collection of tea sets. She started fiddling with her collections in her free time as she was pretty particular about where she placed each item. Poking fun at herself as a collector, she remarked on how her collections hold no expensive objects. Nonetheless, she ascribed their value as vessels for memory.

“I’m always happy to go back and remember bits and pieces of the past, which is really amazing. Going back and remembering to think about every single thing from the past, it all makes up my life now and who I am now.”

One day, when I was back home, I flipped through my mother’s sugar paper collection, dipping a toe into her childhood. I opened the forest-covered sugar collection booklet in the sunlight. Every piece of candy paper inside had been carefully unfolded by my mother, smoothed out at the creases, and

taped to each page with washi tape. They were like soap bubbles, gleaming and reflecting the light of the afternoon’s rays. I turned through the pages, witnessing bubbles that remained unpopped for the thirty years between my mother’s twenties and mine.

“Some of the candy papers aren’t so much because they’re pretty, but they have my own memories: what I felt happy about that day, what I felt sad about, or what kind of special person I met,” she revealed. “Sugar paper is more of a vehicle at these times, a vehicle for my emotions.”

Sugar paper collecting is hardly done by anyone nowadays, but at the time, she saw the large number of identical sugar papers glinting in the light of society’s rapid development and the Industrial Revolution. Because she was born in the 1970s, my mother witnessed China’s reform and rise into a new era.

China’s integration into the global economy in the 1990s wove conspicuous and lamentable changes into its urban fabric: the exchange of old and new created contemporary ruins as close and harmonious relationships between neighbors ceased to exist. By expressing their sentimental experience, artists like Beijing native Yin Xiuzhen became preoccupied with these developments by the end of the twentieth century.

As one of China’s most important contemporary artists, Xiuzhen’s work locates cultural memory and contextualizes the scale of its rapid evolution at the end of the twentieth century by collecting materials that preserve these historical moments. Through her multimedia installation works, the artist spotlights new attitudes toward long-surviving structures, artifacts, and traditions now “treated as ephemeral or disposable.” [1]

Common themes in Xiuzhen’s work include memory, the past and present, and the complex relationship between the individual and a changing society. By collecting and combining materials from these contexts, she weaves together past and present experiences while alluding to the inevitable fading of memory.

Abandoned City (1996) professes perhaps the most powerful and persuasive statement of Xiuzhen’s oeuvre. The artist collected thousands of pieces of demolished houses and furniture and rearranged them into a pseudo-archaeological site. Here, randomly selected objects from chaotic ruins are assigned poetic rhythm with a sense of order.

Another piece entitled Transformation (1997) features a collection of 128 concrete roof tiles from thousands of fragments displaced after

the destruction of Siheyuan in her neighborhood. On each tile, she secures a photograph immortalizing the neighborhood’s vitality. Binding these photos to the fragments engages them in conversation about the change the neighborhood forcibly endured. For Xiuzhen, these unconventional materials embody the memory of a place and time that is rapidly disappearing. She explains the process, noting that in bringing rubble directly into the artwork, the physical histories of the materials become self-evident. [2]

Like my mother’s sugar papers, Xiuzhen’s selected fragments host individual and collective memories, enshrining faint traces of past life. When these materials reappear in the contemporary cultural consciousness, artistic concepts are adjoined to lived realities. This allows objects to speak, to have a voice of their own.

This issue exhibits three pieces from my series, "Unititled," following the life cycle of a rat. This piece, while first in the issue, comes last in the series—with a representation of summer as new life is born. Against the floral background is a mother rat with a pup in her mouth. In this piece, I used acrylic on canvas and a diversity of colors to emphasize the abundance of life during the summer.

Summer brings travel, exploring new places, and learning about different cultures. I took the reference picture for this piece on my way to my gap year in Europe. The heightened colors emphasize my excitement for change and the new season to come.

Caitlyn Bains

Archibald Motley’s The First One Hundred Years: 1863-1963 (1963-72) depicts the reality of Black life in America in one hundred years between the Emancipation Proclamation and the Civil Rights Movement. As a Black artist, Motley uses this piece to connect the past to his personal experiences. The work, depicting a ghastly and nightmarish scene, reflects the living conditions of Black Americans.

Initially, the painting seems quite strange: a Black man rides a ghoulish horse. Then, it becomes horrific: there is a klansman, hands stained with blood, and two concurrent protests—one for Black American rights, the other for white supremacy—while a lynched Black man hangs on a tree. In the background, the Statue of Liberty stands idly, overlooking the scene.

Motley’s work invokes an unavoidable, visceral reaction from the viewer. As the viewer enhances their observation, more horrors seem to unfold. At the time it was made, The First One Hundred Years deviated from Motley’s typical style. Made as a reaction to the changing artistic and political tides and the younger generation of artists, it shows soci-

ety’s understanding of “radical” as constantly changing.

Motley graduated from the Arts Institute of Chicago in 1918, one of the only schools to accept Black students at the time. There, he audited a course taught by the Ashcan School artist George Bellows. Bellows inspired Motley to paint scenes of city life.[1] He continued the Ashcan School tradition of Urban Realism, a group of artists predominantly made up of White men. But unlike other artists involved in the school, who felt representations of urban Black life looked “undignified for high artistic expression,” Motley solely painted scenes from Black life. [2]

Motley felt a sense of duty to depict the Black experience realistically. He once said, “[I] always wanted to paint my people just the way that they were.” [3] But rarely selling his work, Motley found his passion challenging to sustain economically. Institutions also neglected his talent, refusing to show the work of any Black artist for fear of attracting a larger Black audience. There was a lack of patrons as well, as many white patrons lacked

an interest in collecting works with Black subjects, and there were not enough wealthy Black patrons to sustain the artist.

But, in spite of it all, Motley persisted. Maintaining his revolutionary passion, he continued to use Black life as the sole subject of his work. He recognized the importance of Black life as a subject in art, even despite the surrounding stigma. Through his ambitions and perseverance, he became the second Black artist to hold a one-man show at a New York Gallery, in 1928.[4]

Another keystone of Motley’s Harlem Renaissance work is Black Belt (1934). The scene shows the bustling nightlife in Chicago’s Black Belt, a historically Black neighborhood. It matches Motley’s earlier works’ lively and generally celebratory nature but includes a Black police officer in the foreground, the first of many depictions. While the Black police officer depicted is just directing traffic, he represents a very real danger to many Black Americans in the 1920s—the over-policing of Black life. As an urban artist, Motley saw it as his duty to paint the realities people faced during those times, though the piece may be a celebration of Black life and joy. He would not and could not ignore the other part of reality facing Black Americans, one filled with discrimination and systemic violence.

Motley’s works elicited negative reactions before The First One Hundred Years’ completion, especially among Black artists. As

Motley put it, “I know they criticize me, that they say a lot of these things are sort of Uncle Tomish and all that stuff.”[5] The use of “Uncle Tom’’ as an insult has been seen before during the 1920s. The New Negro by Alain Locke, originally published in 1925, states:

“The day of ‘aunties,’ ‘unclies,’ and ‘mammies’ is equally gone. Uncle Tom and Sambo have passed on, and even ‘Colonel’ and ‘George’ play barnstorm roles from which they escape with relief when the spotlight is off.” [6]

These stereotypes of Black life perpetuated insults and reminders of the past. Writers and artists called for these stereotypes to be left behind to create a new and more accurate reflection of Black identity. Criticizing Motley’s works as “Uncle Tomish” shows the next generation’s desire to leave happy scenes behind and to create more revolutionary works. Motley’s The First One Hundred Years lived up to that call, adapting to sociopolitical expectations without sacrificing his artistic standards.

Art depicting Black life developed interestingly from the late 1800s to the 1960s due to changing ideology. The First One Hundred Years is the result of Motley’s ability to adapt and reflect the changing times.

Motley continuously pushed the boundaries of Black art, and The First One Hundred Years does this most visibly. It is emphatic, visceral, and leaves a lasting impression on the viewer. Through his art, viewers can reflect on themes of resilience, adaptability, and spirit, thus drawing parallels into our contemporary world.

Playing on the idea of change as my childhood comes to an end, this composition depictics the sunset view outside my hometown art studio. It embodies a sense of nostalgia, a dominant feeling as I start a new chapter of life. This piece illustrates that bittersweet feeling, and alongside Staying After Hours in the fall chapter, the two paintings encompass a vital location to my development as an artist.

The exit sign that illuminates my hometown art studio at night represents the transition from high school to college. Because of this setting's familiarity change and the impremanence of such comfort are exhibited through this painting. I am “exiting” that part of my life to enter the next phase.

As part of the series “Seasons of Life,” which explores the seasons of the year as different periods in one’s life, Thirty Years represents fall through nature and youth in life. It is a cyclical period of change represented with a growing twine tree, a woman on a street, and her daughter in the same spot 30 years later.

Emma Claire Everett

Whenwalking down the halls of a hotel, one expects to see a series of “Do Not Disturb” signs with the occasional remnants of room service along their path. However, a stay at Boston’s Hotel Commonwealth presents guests with an artistic gem tucked away in what appears to be an unassuming firstfloor hallway.

Located between the hotel lobby and restaurant is the Panopticon Gallery. The current exhibition, “First Look,” consists of twenty-five works on view until the end of April. Panopticon Gallery is free, open 24/7, and contains some of the most eclectic and evocative photography I have encountered in Boston. As the exhibition’s title implies, the photography is impressive at first look, but each collection benefits significantly from an investigation into the artists’ intentions.

Jordan Douglas’ series, “My Father’s Things” captures memoryladen objects to create an intriguing viewing experience. After sorting through his late father’s possessions, Douglas selected the items he felt most reflective of his life. Using black-and-white film, the artist photographed each object on top of a lightbox, capturing “eccentric and aesthetic” indirect representations of his father.

“My Father’s Things” comprises five collage-based works totaling fifty-six images. Some images focus on unique possessions— face glitter, an array of scissors, and a book detailing the meanings of flowers—alluding to Douglas’ father’s creative side, as he, too, was an artist. Other items like a matchbox, mousetrap, comb, and note that says “I’ll be back soon” are emotionally evocative, leading the viewer to contemplate Douglas’ father’s day-to-day life. With this background, the viewer is inspired to appreciate the interesting objects and consider the life that collected them.

C.E. Morse’s “Farrago Series” is a vibrant collection of abstract, expressionistic photographs reminiscent of Jackson Pollock canvases or microscope slides. However, a closer look at Morse’s techniques reveals the strange images as close-ups of car scraps and other

junkyard bits. He explains that his photos required a hunt for “wild art” and that their abstract nature is intentional. In an interview with Panopticon Gallery, Morse details that “the abstract imagery of the series coaxes a personal interpretation contingent upon the viewer’s imagination.” Although an interpretive approach is encouraged, the knowledge that his collection was captured in such an unpredictable setting is essential for receiving its full impact. With this context, viewers walk away from the “Farrago Series,” searching further for unique scenes in unexpected locations.

Duygu Aytaç’s collection “Full With The Question” consists of five striking photographs of human subjects, departing from Morse’s abstract approach. The photos appear to be taken at dusk, allowing Aytaç to capture silhouettes and contrasts unique to the specific time of day. She was inspired to create the collection while reflecting on a James Baldwin interview from 1969 in which he voiced his confusion about humanity’s constant fear of love. Via this context, the viewer receives the collection as five beautiful photos from her homeland and as a venture into some of humanity’s most fervent dilemmas. Viewers are encouraged to consider universal themes, including religion, childhood, and identity, in “Full With The Question.”

Douglas, Morse, and Aytaç’s collections are captivating and complex. They share an ambiguity that leads viewers to wonder about the photographer’s process and question the message of their collections, leading to the unexpected potency of the final two collections.

Connecting “Zen Xan” and “The Missing Photographs”

Lawrence Hardy’s “Zen Xan” presents five dark scenes from Aroostook County, Maine. Four of the five photos focus solely on New England’s nature. Hardy captures falling snow, leafy vines wrapped around a telephone pole, an assortment of daisies, and thick tree roots. The fifth photo, Ol’ Humble, shows an isolated, deteriorating cabin surrounded by a thick snow cover. The collection is beautiful in its clarity but simultaneously harsh and structured with sharp angles and bold contrast. Hardy does not relieve his viewer with color but replaces a location known for its natural beauty with scenes of imagined darkness. This atmosphere is furthered when looking at the titles: falling snow hosts an ominous alternative identity with the title “Murder Flies;” vines are condescendingly named “How Quaint;” daisies are labeled with a lamenting “Ignored Daily;” and winding roots are enshrined in a breathtaking image entitled “Bodies Beneath.”

The collection becomes frightening when considering the challenging images alongside their dark titles. We are left to question why Hardy vilifies what could be so lovely. A look into his inspiration, however, gives reason for his creative decisions:

[Zen Xan] unveils the impact of a childhood marred by violence, childhood abuse, and the abrupt loss of a guiding figure, his father.

In his interview with Panopticon Gallery, Hardy explains that his collection also functions to portray his journey of loss, addiction, and ultimate recovery. By exploring his history, his work is revealed to the viewer as a therapeutic method for him to approach the pain of his past. This knowledge transforms the photos that once seemed cold and harsh into softer scenes meant to recreate a difficult story.

Similar to “Zen Xan,” Denise Laurinaitis’s collection, “The Missing Photographs,” captures outdoor images using a black and white lens. The photos show children blowing bubbles, on the beach, toying with a hose, running through a field, and playing with a model airplane. Though the scenes are simple, they demonstrate Laurinaitis’s eye for ambiguity. Hose Spray shows a garden hose moving in a snake-like manner while the girl to its left dances similarly. In Bubbles, a boy is framed by a bubble so that his eyes are erased from the image, though the rest of his face is centered.

Each photo obscures the children’s faces in various ways. Since those photographed are Laurinaitis’s children, she may have concealed them for anonymity purposes. But their unknown visages also allude to Laurinaitis’s uncertain past. In her interview with Panopticon Gallery, she explains that, when looking through photos from her childhood, she realized that a period of her life was never captured. She describes “[t]he gap between early childhood and adolescence as if it didn’t happen. The gap between my father’s death, and when we kids were old enough to photograph with our pocket-sized 110 film cameras.”

Similar to Hardy, Laurinaitis’ loss of her father at a young age has an impact on how she remembers her past. The loss left Hardy without the person he considered his guide, and, for Laurinaitis, his passing destabilized her family to such an extent that years of memories were never captured. Hardy chooses to dive deeper into the darkness of his past in “Zen Xan.” Zen Xan, translated from Basque,

means “it was.” This title perfectly encapsulates the direct reality Hardy presents to his viewers. Laurinaitis alternately chooses to pull on the ambiguity of her past. Through scenes of her children’s lives, they grapple with the years of her life never captured and, through it all, imagine what might have been.

Although their journeys from unsettled childhoods to creative careers vary incredibly, similarities exist in how they approach their pasts. Both collections capture landscapes in black-and-white. Through the coloring of the images and the figures (or lack of figures) pictured, viewers sense that something is awry in the environments captured.

An investigation into Laurinaitis and Hardy’s histories demonstrates this is due to the collections’ underlying meanings. In their images, they explore childhood, memory, and identity. They both depict how the loss of their father at a young age affected them; Hardy chooses to chart his path from then to now, and Laurinaitis revives that period of her past through her current life as a mother.

The initially solemn themes of “Zen Xan” and “The Missing Photographs” become far more optimistic through the photographers’ commentary in their interviews with Panopticon Gallery. Hardy explains his collection as intending to comfort viewers with similar struggles. “It is an arresting visual expression of a personal story of feeling lost and gradually understanding life,” he describes. “It persistently offers reassurance, telling those facing similar challenges: You’re not alone; there’s always a different path.” Laurinaitis similarly considers her creative process as allowing her to revisit a childlike

perspective, noting, “The days pass quickly, and I take it all in. Childhood is fleeting, and I get to experience it all over again. The wonderment, the skinned knees, the giggles, and the in-between. I feel that excitement in holding a firefly, its tickle so gentle as it walks across my hand. Did I actually live this before?”

Their commentary is enlightening. Though the collections appear solemn, the photographers’ voices gesture to a different perspective. Viewers can come away from “Zen Xan” and “The Missing Photographs” with an idea of the positivity and possibility that can come from pain.

The first look a viewer takes at their collections — and the collections of Jordan Douglas, C.E. Morse, and Duygu Aytaç — is revealing. First impressions register the most striking elements of a piece of art and often reveal a viewer’s potential preconceptions; the context that follows permits nuanced reflection. By exploring the background of the featured “First Look” collections, visitors at Panopticon Gallery are reminded to pause, contemplate, and appreciate what can be found in a closer look.

This series, titled “Stains of Life,” utilizes ink as the medium to ‘stain’ the paper and preserve memories. This work captures the feel warmth as someone makes you a warm drink on a crisp fall day.

35mm black and white film. Push processed. Boston.

All of a sudden, people start deviating from the path. No longer interested in the statues along the walls, they shift their attention to a young girl in the middle of the room. Soft whispers turn fervent. People point, take pictures, and clutch their hearts to ease the pounding.

Among the bodies stands a girl, a ballerina. She relaxes into the fourth position, setting all her weight onto her back leg, letting her front leg extend comfortably forward. Refusing to acknowledge the crowd, she raises her gaze, grazing the tops of their heads. Hands clasped behind her back, the comfort of her stance softens her stoic expression. Her bronze skin attracts the light bouncing off the statues surrounding her, framing her as the center of attention.

D.C. – The gallery beckons you to enter. Whispers bounce off the walls. Warm yet artificial, track lighting bathes the room in a comforting but unfamiliar hue. Bodies move through the space, bumping into each other to avoid getting near the art and wire guards. As you wander through the room, your eyes are graced with beauty across the ages: Ernest, Rodin, and Degas present stories of Amazonian warriors, mythological scenes, and Parisian dancers. Rays of golden light bouncing off the statues direct the viewer’s gaze. In and out, eyes and bodies follow the imaginary path around the room.

Poised, proud, and peaceful—the perfect ballerina. Viewers inch closer to her pedestal, fiending to connect with her. Visions of childhood dance classes, Victorian operas, and Impressionist painters flash in viewers’ minds. Secrets of faraway lands and lives hypnotize viewers, rendering them oblivious to the bodies moving around them.

With one sound, the sea of people evaporates. Disembodied voices begin shouting, their cries slicing through the peaceful gallery. All hypnotic trances break as bewildered museumgoers struggle to grasp their surroundings. Pushing and shoving to get out of the way, people flee from the stampede, roaring through the gallery, not daring to be associated with the two figures behind them. What was once bathed in bronze light now bears interjections of red and black.

Two people sit on the ground, screaming at the room of innocent bystanders. Confusion and fear hang heavy in the gallery; what was once a space of tranquility and enlightenment has been tainted by malice.

The ballerina stands unwavering at the scene, separated by space, time, and a glass box. Was that a twinge of fear that spread across her face or just a shadow from the paint? Perhaps this scene reminds her of something all too familiar—her “terrible reality” as a student dancer at the Paris Opera Ballet.

Edgar Degas’s 1880 statue Little Dancer Aged Fourteen captures a poignant moment: a young girl fighting to find dignity. Young girls from working-class families sought positions in the ballet to escape poverty. The girls, some as young as 11, found themselves the targets of abuse. They were called nasty nicknames, opera rats (“petits rats de l’operá”), [1] to remind the young girls of their place in the opera and the world—at the bottom. Historians believe the term originates from the sound of feet scurrying on and off stage, traveling among the shadows of the opera house. The name’s association with dirt, pests, and poverty was also intentional, referring to the girls’ working-class blood. Young ballerinas also found themselves targets of unwanted

advances. Male “protectors” took advantage of young ballerinas’ naivete and low self-esteem, pressuring them into undesirable situations. Like most cases of assault, specific instances and examples are lost to history.

Luckily, the name of Degas’s ballerina prevails. Marie Geneviéve van Goethem. The daughter of a laundress and the younger sister of a prostitute, Marie became a dancer to escape a life of poverty. [2] She joined the Opera before the age of 11. Unfortunately, most records of her life begin and end with Degas’s sculpture.

Until Now.

“The Earth is beautiful and we’re destroying it with climate change,” a woman chants as she sits on the floor. [3] Behind her stands Marie. The pedestal and case are covered in swathes of black and red paint reminiscent of pain, dirt, and blood. A man and a woman sit crisscross on the floor with their hands up as if surrendering. They think this attack is peaceful, that they did not really hurt the art, just its case.

“That is why we decided to come visit this beautiful, beloved child that the world knows. She’s imperfect like we all are imperfect, but

she’s strong and she’s not resigned to destruction.” The protestors have done their homework: they understand the public’s hypnotic fascination with the statue and the history behind the work. However, they miss the nuanced emotion of the ballerina.

She is not strong, but she has to be. The fortitude in her posture comes from the strain of her shoulders, her hands clasped behind her back as she pushes her arms to become impossibly straight. Her impervious and avoidant gaze denies her fast-approaching assailants any sign of acknowledgment. Brooding, she veils herself in confidence to mask her vulnerability. She can never escape the assaults she faced in Paris. Even after 200 years, she is still clawed at, groped, and used as a pawn. She will forever remain a potential target.

Since 2022, there have been 38 attacks on art, sculpture and painting alike. [4] The attacks grow increasingly redundant and ineffective, orchestrated by environmental activist groups that elect galleries as stages upon which they disrupt and deface. In their infancy, the attacks received scathing criticism. The “all publicity is good publicity” mentality that the protest organizations held proved fruitful, as almost every newspaper published a report or commentary on the attack. However, as the attacks continued, the outpouring of frustration turned into a lull of desensitization and disinterest.

When reflecting on the attacks, many are quick to denounce the protesters and their organizations, brushing the topic of climate change under the rug. However, ignoring the conversations surrounding climate change nullifies the attacks, meaning that the works were targeted for nothing. The public is then made to be just as ignorant as the protesters. Is this the unfortunate reality? That we must acknowledge their actions to reinstate the agency of the artworks and their subjects?

September

The leaves have started to turn red and fall, covering the ground in a mix of red, orange, and yellow. The wind blows and scatters some leaves onto the pathway. The sun is shining bright, illuminating the nearby benches and the lone tree next to them. Walking from breakfast, I stop to look at the fall beauty in front of me. I wanted to capture this moment as the tree passes through time as its leaves fall. It reminds me that change is a natural part of life and needs to be embraced. My mind thinks of all the little brush taps it would take to paint those leaves, and the layers of paint to create the benches shadows. I snap back to reality and remember, I’ve got class in 10 minutes. Sitting next to that tree will have to wait. I can’t be late.

This series, titled “Stains of Life,” utilizes ink as the medium to ‘stain’ the paper and preserve memories. My Mother’s Wall captures the memory of the Hamsa covered wall in my childhood home.

Xinyue Jin

Therain that started last night still pours.

I don’t know when it will stop. The forecast says it could last until tomorrow morning.

I sit by the window, looking out at the people coming and going. Looking at the Boston trees whose buds sprouted so recently. Raindrops slam against the window, and my pant legs are plastered with the impression of their fingertips from when I was outside. I feel connected to the world beyond the pane. It feels like its dampness will always be present in the human memory.

This dampness prompted thoughts, and I began to imagine the rain and its admirers from centuries before.

Summer thunderstorms come in hot and go out hot. The emotions that come with them are swept up in one big swath. The depression brought on by the low pressure simultaneously brings me strength. I am standing in a wheat field. The oncoming wave of humid wind passes first through the field and then to me. The straw cuts across my calves: a fierce transfer of energy. The sky presses my

body down into the earth beneath me.

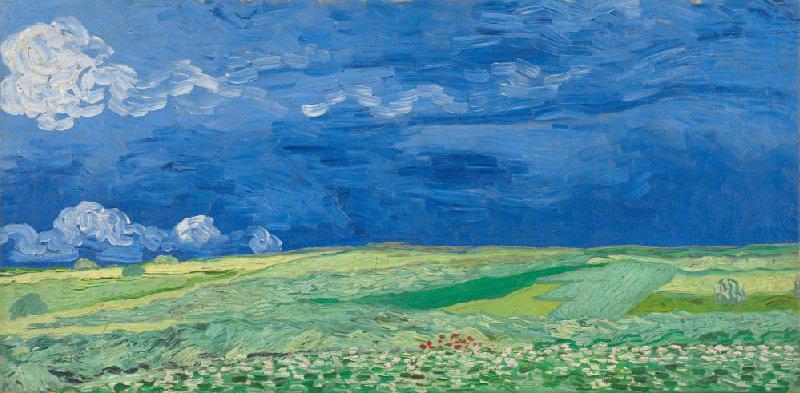

Is this the same “sadness” and “extreme loneliness” that Vincent van Gogh painted with in Wheatfield under Thunderclouds (1890)?

[1] The overwhelming emotions he experienced in nature were also sometimes positive, I imagine. In a letter to his brother, Theo, he wrote:

"I am almost convinced that these canvases will tell you what I cannot express in words, what I consider the health and solidity of the countryside." [2]

Vincent van Gogh, Wheatfield under Thunderclouds, Auverssur-Oise, July 1890, oil on canvas, 50.4 cm x 101.3 cm. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/collection/s0106v1962.

The simplicity of the composition and primitive symbolism of the colors plainly and intensely crash before my eyes, bursting with the essence of nature itself.

I’ve often compared nature to people when considering their cyclic patterns. In the fall everything goes down. Contrasting with the vivacity of the summer, the fall’s energy is diminished and muted.

One October day in 1889, Van Gogh drew a great deal of inspiration from the large gardens surrounding the building where he was hospitalized.[3] The Garden of Saint Paul’s Hospital (‘Leaf-Fall’) (1889) captures this seasonal moment: the colors, the lonely pedestrian, and the wind-swept leaves suggested by the light, frenetic brushstrokes all gesture to the mood of the season. Dreary. But Van Gogh still sets the scene with a warmtoned palette; a cool loneliness battles with nature’s force.

His lonliness, even in a hospitalized state, could not consume him because he was accompanied by autumn’s last hopeful whisper. It was possibly a final fight for his life.

I am now in the midst of the coming spring in Boston. This is a certain spring in the phases of my life. This, too, is a certain epilogue to the current rain in my life. I’m still waiting for it to stop, knowing that when it does the sun will appear again.

Vincent van Gogh, The Garden of Saint Paul’s Hospital (‘LeafFall’), Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, October 1889, oil on canvas, 73.8 cm x 60.8 cm. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/ en/collection/s0046V1962.

Sudden Silence is part of the series “Seasons of Life” series and represents winter as old age. It portrays a woman and her aging mother over a snowy street, exploring the idea of old age and the end of life; just as in winter, when cold takes over and a silence falls upon nature.

My current paintings reference the spaces I walk by daily, which I photograph through the changing seasons. Intuitively, I compile these photographs through threads of comparison. Within this imagery, the frigidness of winter is represented by a series of eerily still moments.

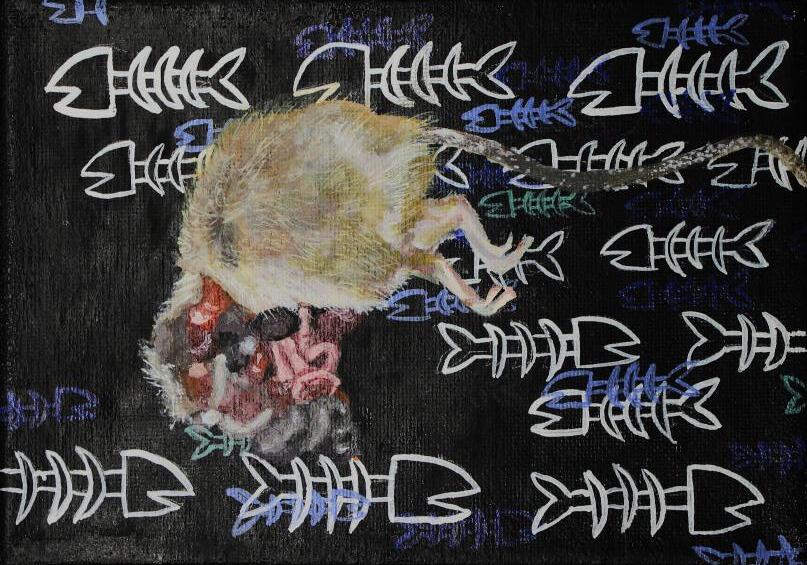

Inspired by a dead rat I saw on the Boston metro tracks, I decided to create a piece about death and hibernation during the winter season. I used acrylic on canvas; after beginning with a black wash, I painted a flat background design that would contrast against the naturalistic rat.

To understand the world around us, humans have created stories to explain the formation of the universe. One example comes from the Bible in the chapter of Genesis. God spends seven days making the sky, oceans, and land. Then, he brings every animal and plant to life. In this story, God is the creator, the one with a desire to create a new world. We see how dedication allows for an idea to become reality. Whether you are religious and believe in God or see this story as a fa-

ble, the connection between a creator and the time they spend at work is shown to readers. The connection between creation in time is important to understand when examining what it means to be an artist.

There are many ways to interpret the terms artist, creator, and inventor. In many cases, to be one is to be the other. Over the years, specialization evolved for artists, musicians, designers, and other creators to make careers out of their passions. Even chefs dedicate

their lives to the art of cooking, experimenting, and creating new recipes for the world to enjoy. The ability to study art in school allowed for even more focus on craft and resulted in an intense relationship between creators and time. Artists rely on their creativity, talents, and practice to live, resulting in a pressure and necessity to create.

Lauren Boysa is in her junior year as a painting major at Boston University’s College of Fine Arts. She began painting seriously when she was 13 and has invested over eight years in painting, learning, and practicing her art. Now, as an art student, she dedicates herself and her career to art. Her main medium is oil on canvases, but she also loves experimenting with sculpture, drawing, and more.

“Art is my nine-to-five,” said Boysa when discussing her relationship with time. Time is money for everyone, but especially for those who create. On average, Boysa spends three weeks to a couple days on each painting. Her process varies for each piece, but after practicing for so long, she has it down to a science.

Boysa begins by planning the painting, going through past sketches, finding inspiration, and imagining. She draws upon moments of reality, imagining different possible outcomes or settings to create works that are both realistic and dreamlike. Boysa also looks at photos and references, which she may incorporate into her idea. Then, she creates the canvas and the unique and detailed color palette of each painting. Time restraints may limit her color palette, though she prefers to incorporate the entire rainbow of colors.

“When you look at a finished painting you only see the final product,” Boysa said. She knows that everyone sees her work with their own biases and conceptions of what is good or bad–if good and bad even exist. For an artist, to see a painting they made is to see themselves. Boysa sees her thoughts, her time, and her creation. She recognizes the conscious and subconscious parts of her that come out in her art. The painting becomes the painter, so how is an artist meant to separate their minds from their work?

Boysa relaxes by experimenting with other mediums like sculpture and drawing–what she calls “liberating” and “fast-paced” mediums. In art school, Boysa explained, they tell you to keep creating. According to the Milan Art Institute, it is better to push through the artist’s blocks and to create anything you can

rather than stop working. [1] However, it is also important to rest, which Boysa emphasized is hard when paintings need to be done.

In their junior year, painting majors at Boston University are given their very first personal studio. The studio is a space specifically for them, where they are meant to do their work. This allows for a separation between the projects and the artist’s house, though Boysa described the studio as her “second home.” The studios bring the painting majors together to form a sense of community as they paint together. Creators need support, to keep going even when they feel stuck. Also in junior year, the painters begin creating their own body of work, with the leisure to make what they want. The whole world is at their fingertips, which can be overwhelming, especially with deadlines. Support is what gets the artists through. The community encourages open discussions, asking questions, and helping each other out. Boysa has become close friends with many other CFA students

and feels comfortable creating because she is in a positive and judgment-free space.

Going back to the story of God, we remember the creator is the driver, the one in charge, and it is what they feel inside that leads to creation. The artist themselves must decide what they think and how they want to spend their time. To see a single painting is to see an entire life and passion that led to the moment when the painter’s brush and canvas meet for the first time.

As humans have evolved, there has been an innate connection between us and creation. Humans began inventing tools for survival, eventually creating ways of expression and communication. Humans use their consciousness in connection with the physical world to make something from nothing. Growing up, Boysa did just that. Her dad, a house painter, has been influential in pushing her to keep working and follow her passion for art as a career. In all the years, her styles and themes have changed as she learns more about herself, painting, and the world around her. Currently, she focuses on surrealism, combining images of nature and animals. Boysa said she has emphasized the theme of animal and human likeness in her past works, with human-like animal forms. As a lover of nature and preservation, her art calls out how society views wild animals. As if to say they are people, too.

C.G. Jung, a well-known psychologist, notes, “Art is a kind of innate drive that seizes a human being and makes [them] its instrument.” Each medium of art and creation is different, but the definition of a creator is still the same. To be a creator is to feel a passion that drives you to dedicate your time to craft. The hours, days, months, and years that creators use for one project shows just how important creating is to them.

“There is something on the other side of every painting,” Boysa says. Starting a painting is taking a chance. She doesn’t know how long it will take her, what it will look like in

the end, or if she will be the same when it is finished. All she knows is that she is doing what feels right when spending time creating.

I was inspired by my daily walks to and from campus. In the winter season, I become more aware of each step because of the cold weather challenging all my senses. Each day, I try to remember to find new ways of looking at the same things on my route, or to find new spaces I can appreciate. This is very important to me in the midst of the cold weather: To be present while walking by enjoying every place I pass, rather than trying to get from A to B quickly to escape the bitter cold.

Romy Binstein, LetUsStopForaMoment , “Stains of Life” series. Ink on Paper, 12 x 18 inches

This series, titled “Stains of Life,” utilizes ink as the medium to ‘stain’ the paper and preserve memories. This moment in time symbolizes breaks, taken during the day to sit with someone and just enjoy the moment.

Continuing my series of rats, I hoped to mimick the cyclical nature of the seasons within the life cycle of a living organism. Naturally, after death comes rebirth. In this piece, I painted a female rat against an unnaturalistic flat background which includes an ultrasound rapidly growing fungi-like web.

Emma Claire Everett

Howcan sixteenth-century Dutch oil paintings give us a new lens for considering cartography’s history, the ocean’s mysteries, and time itself? In his February lecture at Boston University, Dr. John Durham Peters challenged his audience to consider the connections between these seemingly disparate subjects.

Dr. Peters, a notable media historian and Yale University Professor of English and Film and Media Studies, began his talk from a distance. He demonstrated contemporary images of how we conceptualize the globe (imagine a bright blue sphere captured by Google Earth) before quickly transporting us back to the advent of circumnavigation. Dr. Peters presented the primary focuses of his lecture, synthesis, and montage while examining Martin Waldseemüller’s world map from 1507. Waldseemüller’s map, the first to

ever include the Americas, is a revolutionary example of cartography’s relevance in today’s perception of the globe. By depicting the development of maps from biblically symbolic illustrations of the world to our modern-day blue marble, he demonstrated our past as a series of shots pieced together to form an engrossing “Earth Montage.”

Dr. Peters furthered his examination of synthesis and montage by investigating simultaneity in the visual arts. When approaching a painting, a viewer’s eye is typically drawn to active figures in the scene, figures in the foreground, or characters they recognize from mythological or biblical stories. Dr. Peters analyzed three Renaissance landscapes to show some artists that challenged this by treating every figure in their paintings with an equal amount of importance.

The first work Dr. Peters examined was Pieter Bruegel’s The Census at Bethlehem (1566), which places Mary and Joseph in a Belgian village. He noted how Bruegel had the iconic Virgin Mary blend into her surroundings. Her blue dress fails as an identifier because others are dressed in similar clothes, while other aspects of the painting catch the viewer’s eye before any of its Christian themes. Dr. Peters focused on various figures to show the audience’s instinct to jump from the census-goers to the ice-skaters, and to take in the painting in its entirety, before locating the arriving Mary.

"Pieter Bruegel the Elder: The People's Census at Bethlehem" by larsteglbjaerg48 is marked with Public Domain Mark 1.0. To view the terms, visit https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/?ref=openverse.

Dr. Peters then shifted to Nicolas Poussin’s Landscape with a Man Killed by a Snake (1648), which depicts the aftermath of a man’s fatal snakebite. A deep analysis of the painting uncovers how many scenes can be contained in a single temporal space. Although the three figures in the foreground serve as the initial focal point of the scene, Dr. Peters challenged the audience to look past them. Specifically, he focused on the fig-

ures on the boat, wading in the stream, and on horseback. It could have taken the men on horseback hours—even days—to receive word of the man’s death. Dr. Peters explained that Poussin’s choice to include them reveals the chain of communication that will result from the man’s death. Once the viewer recognizes these figures and the events to come, they are placed in a state of anticipation. The importance of the future surpasses the figures in the foreground, and the viewer begins to see the endless waves that can disperse from one moment in time.

By Nicolas Poussin

- http://www.aiwaz.net/panopticon/ landscape-with-a-man-killed-by-a-snake/gi4975c530, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7215265

For the final landscape, Dr. Peters returned to Bruegel with his Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (1560). The title references the Greek myth of Daedalus and Icarus. At the story’s onset, Daedalus crafts a set of wings for his son to escape their island prison. Icarus accepts the wings but disregards his father’s warnings, consequently flying too close to the sun, resulting in his fatal plummet into the sea. In Landscape with the Fall of Icarus,

Bruegel challenges his viewers’ expectations by placing the drowning Icarus inconspicuously in the foreground. The viewer’s gaze is likely first drawn to the horizon, the ships, or the unnamed farmer. Without the guiding title, it would be easy for onlookers to miss Icarus entirely. Dr. Peters punctuates here the way that stories we consider of great importance are of equal weight to other strands of time. William Carlos Williams explains this sentiment in his poem inspired by Bruegel’s painting: “the edge of the sea / [was] concerned / with itself” during Icarus’ fall. [1] In the presence of a legendary myth, ships continue to sail, a farmer continues to work, and the ocean remains relatively the same as before Icarus’ fall.

"File: Pieter bruegel il vecchio, caduta di icaro, 1558 circa 01.JPG" by Pieter Brueghel the Elder is licensed under CC BY 3.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/?ref=openverse.

Dr. Peters’ examination of the montage of moments that create these three landscapes can aid viewers in recognizing human history as it is: intricately layered and infinitely complex. Referencing Ferdinand Magellan’s navigation during the early 1500s, Dr. Peters said, “every day that he traveled was like a breath into the globe.” Magellan is not only credited as the first explorer to circumnavigate the globe but also the first to confirm Waldseemüller’s 1507 depiction of the strait explorers should pass through to reach the Americas. [2] In this period of exploration, maps were continually drawn up and compared. Cartographers’ layering of explorers’ discoveries steadily created the globe we know today. Synthesis is essential in cartography, and it has maintained the same importance in fields like history, medicine, and, as Dr. Peters made clear, the visual arts.

After his lecture, Dr. Peters opened the floor to questions and comments from the audience. The primary topic discussed was the issue of montage in language. One member raised the question of whether or not writing can maintain the same simultaneity that occurs in the visual arts if the reader is intended to move through a text sequentially, one word at a time. This question reminded me of Dylan Thomas’ poem “Vision and Prayer” and E.E. Cummings’ poem “r-p-o-p-h-e-s-sa-g-r.” These works challenge readers in their

perplexing structures. Should “Vision and Prayer” readers start at the top of the page, though it is easy to be drawn to the lone words in the poem’s center? Where should readers turn when Cummings has splattered indecipherable letters across the page? Perhaps they will just find themselves stuck on his interesting chains of faulty punctuation. There is, of course, no charted path for readers who approach poems that confront convention so blatantly. And that is likely the intention of these writers. Their puzzling syntax challenges readers’ preconceived notions of what parts of a poem are most important.

As Dr. Peters explained through his examination of cartography, montage is essential in forming factual knowledge. But it can also be employed to break down tradition. Thomas and Cummings confront typical literary layering in their structures. Poussin and Bruegel’s works similarly make viewers question the central aspects of their paintings. Poussin connects a chain of figures to the dead man in the foreground; Bruegel tucks Mary into a packed crowd and hides Icarus in a corner, allowing his title figure to slip from the viewer’s sight. These odd decisions remind viewers that a painting’s focus is never clear-cut. In the same way, each map from the fourteenth century played a unique part in the creation of the globe; each word in a poem ties the work together, and every figure on the canvas is essential to the scene. Instead of letting viewers take their words at face value, these painters have them consider the synthesis necessary to make one moment.

on notable characters in paintings, viewers should look deeper into the landscape, to the figures herding the sheep and plowing the earth. Whether it be in a painting, poem, or human history in its entirety, we should always strive to consider the pieces needed to make one whole. Once we break from custom and take a broad step back, we can begin to imagine our endless “Earth Montage.”

Readers should allow their eyes to wander first to odd words at the center of the page. In the same vein, rather than focusing only

As the final piece in my “Seasons of Life” series, Blossom represents spring as motherhood. It portrays a young woman behind her childhood self, now connected to her own children and to her older self. Blossom explores the idea of spring as a period of rebirth and growth in nature as well as in life.

The two faces shown are based off of cardboard sculptures that I built with my friends. My goal was to present geometric and rigid objects as softer figures. This is similar to the rebirth that that takes place from winter to spring. What once was cold and dead can change into something lively and beautiful.

Xinyue Jin

In my early childhood, I always wondered how the seasons could change so suddenly. It was as if only within the blink of an eye, satin green leaves turned a coarse yellow and withered away. Still, I always want to witness every moment of change, like the instance in which the second hand of a watch completes a revolution and the minute hand jumps. My yearning to find the first flower that blooms at the onset of spring, the first beam of hot sunlight at the onset of summer, the first leaf that tumbles to its demise at the onset of fall, and the first strong wind at the onset of winter, persists. The desire to perceive time through these vehicles and register each seasonal transition is an indelible mark on human nature. With this in mind, artist Park Yunji uses water and light as a medium to symbolize life and the flow of time.

Park Yunji, a contemporary South Korean artist born in 1990, combines traditional Asian art techniques with the characteristics of Western Impressionism. Her brushstrokes draw on the Chinese ink painting technique of rendering.

The multidimensional relationship between natural objects and the nuances of light and shadow is highlighted by superimposing each diaphanous layer of color. Via this technique, Yunji visually translates how light and shadow appear to the human eye as objects ebb and flow between clarity and haze. To better emphasize this effect, Yunji uses a special traditional Korean painting paper called Jangji that leads the pigment to deviate from the shape of the brushstroke and flows or spreads to create a coincidental effect.

Echoing the hallmarks of Impressionism, the artist focuses on the dynamics of light and shadow, the passage of time, and change in the natural world. Yunji’s interpretation of this dynamic is reminiscent of artists like Claude Monet. In the early 1890s, Monet moved into an apartment across the street from the main cathedral in Rouen. Here, he was inspired by the sunlight that shone on the monotonous gray facade of the church. He set up his easel in three locations, moving from place to place as the light and time altered. The artist intended to capture the subtle shifts in the hue of

the ever-changing atmosphere of the Norman sky, creating an architecture of colors that he brought to life on the canvas one by one. It was not so much the cathedral’s Gothic architecture that intrigued Monet but the pulsation of light and shadow projected on its surfaces. His infatuation with color’s emotive dance through nature is one shared by Yunji, evident in the way she delicately defines the silhouette of time and space.

In 3:06pm (2020), Yunji depicts shades that cradle the restless shadows of treetops. She fills her canvases with light, low-saturation pigment to conjure the serenity found in our natural environment. Though they are flat, Yunji’s paintings present an illusion of dimensionality, a sense of lyrical movement in her delicate brushstrokes that animate the light’s dance. Through her paintings, it is as if one can feel the cool breeze grace their cheeks and hear the rustling leaves whisper in their ears. The hustle and bustle stops instantly. Time is suspended. You cannot help but put your hands in front of your eyes to shield them from the naughty, ever-dancing sunlight.

When admired in isolation, each work appears to harness the essence of a single moment impervious to time. When observed collectively, though, time transcends the conceptual and becomes observable. In 2:50pm (2022), 3:06pm (2020), and 8:53pm (2022), the scumbling of the pigment on the wet paper is repeated several times and then stuck to the canvas. Although this process is repeated over multiple days, it is as if a singular moment is harnessed, depicted, and penetrated into the memory.

Yunji’s art is like a flowing pool of emotions, touching the sensitive, emotional nerves of the viewer with color. The unassuming pockets of nature that we may overlook in our daily life— the velvet texture of spring flower petals, the tender green of plant buds, the transitional hues of leaves—all appear in her artworks with delicacy and faithfulness to the natural realm.

Yunji is always searching for a theme or philosophical question. As sentient beings, in what way do we face time? What is certain is that constant time is evenly distributed to everyone. What differs is how we spend it. The artist chooses to look at time by placing herself directly in front of it and allowing the medium to interpret the moment.

She writes in her artist statement that the “sense of sight [creates] imagination by all the other senses” so that her art engages the full body and spirit.[1] The artist creates to confront time and to superimpose, separate, and emulate its effect in a still image.

Each of her paintings feels like a déjà vu in our lives, looking at the shadows of the gaps hidden inside these continuities. In those painful and joyful, some moments lay with the past while others accompany us on forward paths, affecting our movement through life like the natural world we navigate. In any case, having the present and immortalizing its essence in painting is precious.

To paint the Lily of the Valley, I took inpiration from its form that represents the passage and cylical nature of time. These plants blossom in my front yard every spring. They depict the familiarity, comfort, and hope that spring provides us with. Every time I see these plants begin to blossom, I am filled with excitement about the months ahead.

Eboard:

Lauren Glogoff - Editor in Chief

Lauren Glogoff is a senior studying History of Art and Architecture and minoring in English at Boston University. She fell in love with art history during her first year at college and quickly grew passionate about creating a lasting art community on campus. She revived “Squinch Magazine” in the spring of 2022 and has since served as its editor-in-chief. She also serves as president of the Boston University Undergraduate Art History Association. With a strong interest in the ontology and authenticity of art, especially in the age of Modernism, Lauren works to understand art’s understructure and its shaping within society. Next year, she will continue her exploration in London at the Courtauld Institute of Art to obtain her MA in History of Art.

Willa Barry - Business Manager

Willa is a sophomore studying art history with a minor in entrepreneurship. She currently serves as the head of operations for Squinch. Willa enjoys contemporary art, with a keen interest in photography.

Kayla Palmer - Advertising Director

Kayla is a Junior studying Media Science and International Relations. In Squinch, Kayla is able to combine her interests in communications and visual arts/design. She is excited about all the work the Ad Team has done this semester, and is looking forward to continuing to increase Squinch’s visibility within the BU community.

Romy Binstein - Creative Director

Romy Binstein is a senior studying Architectural Studying and minoring in Visual arts. She currently also serves as the president of the Undergradaute Architecture Association. Her current interests are sustainable vernacular architecture and water-based artworks. She aspires to work in the field of architecture by combining art and architecture in continuous conversation with the surrounding environment and community.

Gabriella Sproba - Senior Editor

Gabriella is a senior studying history of art & architecture at Boston University. Her current interests include museology, curation, and the contemporary art market. She aspires to work as a private art consultant and gallery owner with an approach that emphasizes fair artist representation.

Gabriella Rice - Senior Editor

Gabriella is a senior studying art history at Boston University. She is fascinated by the iconography developed in the Medieval and Renaissance periods, wishing to study their progression and use through time. Gabriella hopes to become an art curator, specifically highlighting Renaissance works and their connection to modern topics. Through her time at Squinch, she hopes to explore the interactions between artworks and their viewers.

Alexander Gee - Finance Director

Alex is a sophomore in the Questrom School of Business, concentrating in finance, and minoring in philosophy. He enjoys experimenting with the photographic process and currently prefers to shoot black-and-white film. Alex hopes to one day return to the darkroom.

George Stoica

George is a sophomore in the College of General Studies with plans to major in biochemistry and molecular biology. He typically works in oil paint and loves learning new painting techniques to create greater technical works. George enjoys painting, as it allows him to express creative ideas on canvas, which is a great way for him to relax.

Elena Jordan

EJ is a sophomore in the College of General Studies where she majors in art history and minors in visual arts. She is excited to continue growing Squinch for the remainder of her time at Boston University.

Lauren Boysa

Lauren is a Junior studying Painting and History of Art and Architecture at Boston University. In Lauren’s current work, forms can surface both as individual and relative to the surrounding imagery. Compositions are created through a stream of consciousness, therefore each form could not exist without the previous image. Lauren’s photography practice informs the reference images for the painting, which consists of spaces she sees daily, compiled intuitively in a collage. When representing an image, subsequent memories are associated with the imagery and create a narrative. The process of naming these unplanned associations comes through automatic writing which rationalizes the content through reviewing threads between words or phrases.

Romi Fernandez Riviello

Romi is a sophomore at Boston University, majoring in architecture, with minors in art history and business administration. She is passionate about how art can form connections, not only on a personal level, but also with others. Exploring expression in different mediums is something she is currently experimenting with. Romi hopes to combine her love for art and travel with increasing the accessibility of art. She loved her time at Squinch this semester and is excited to continue.

Sara Sierra-Garcia

Sara is a freshman at Boston University, majoring in art history, and minoring in visual arts. As an artist for Squinch, she hopes to explore different artistic mediums and help grow the magazine. She often works with ceramics but has recently explored mixed media with a special interest in collaging and photography.

Svetlana Stepanova

Svetlana is a freshman at Boston University studying painting (CFA) and architectural studies (CAS) in hopes of completing a dual degree. She primarily works in oil paint with an interest in realism but loves several other mediums and styles as well as photography. Svetlana hopes to pursue a career combining both art and architecture and is excited to continue working with Squinch. ** Chapter header Artist

Anna Novick

Anna is a freshman at Boston University majoring in graphic design and minoring in business administration and advertising. She enjoys mixed media and experimenting with different forms of art. As an artist for Squinch, she hopes to help grow the magazine and create meaningful connections for the future. Anna is excited to continue to work for Squinch and expand her knowledge of art.

Writers:

Barrett Walsh

Barrett Walsh is a junior studying journalism and minoring in computer science at Boston University. She is a multimedia journalis and artis. She began writing for Squinch in 2023 and found a welcoming outlet for expression and connection with other creators. In the future, Barrett hopes to work as a photojournalist and continue her education in graduate school. She is inspired to share the real stories of people, their art, and unique experiences with the world around her.

Caitlyn Bains

Caitlyn is a sophomore studying art history at Boston University. She is interested in the provenance and repatriation of art with further interests in the turn towards modernization and globalism during the late 19th century to the early 20th century and how that intersects with art. Caitlyn hopes to become an art curator specializing in provenance research.

Emma Claire Everett

Emma Claire is a junior studying English and history at Boston University. She is interested in abstract forms of painting and photography and is particularly fascinated by the Surrealist movement and Postmodern photographers like Cindy Sherman and Bob Mazzer. After senior year, she hopes to continue creative research by pursuing a doctoral degree in English literature.

Gabrielle Wylie-Chaney - Junior Editor

Gabrielle is a freshman studying History of Art and Architecture and Italian, minoring in Cinema and Media Studies and Urban Studies at Boston University. On campus, she works as a Junior Editor at Squinch Magazine, as part of the Videography Department on the BU Buzz, part of the Art Direction Department at Off the Cuff, an Intern for Special Projects and Photo on the BUnion and Pinky Toe, is a DJ for Issa Vibe on WTBU and apart of the Food Delivery team at Student Food Rescue.

Xinyue (Jasmin) Jin

Xinyue (Jasmin) Jin is a junior studying History of Art & Architecture at Boston University. Her pursuits are centered on exploring the impact and utilization of digital techniques within contemporary art. She aspires to highlight the elegance of traditional Chinese artistry through digital media, with the ultimate goal of founding a creative agency that embodies the distinctive beauty of Asian art.

Julia Cheung

Julia is a junior studying graphic design at Boston University. Her career goals involve pursuing packaging/product design, social media design, and branding. However, she also has a strong passion for singing, film photography, printmaking, and flower farming. During her time at BU she has developed a few brand visual identities for projects and start up-companies and will continue to expand these skills into the advertisement of Squinch magazine.

Mia Hand

Mia is a sophomore studying History of Art & Architecture with a minor in political science at Boston University. Her passions lie in contemporary photography and mixed-media art, particularly exploring their connections with gender and public policy. During her time with Squinch, she aims to enhance the community’s online visual representation and foster its growth.

Summer

“Preserving Memory via Repurposing Material”

By Jasmin Jin

In Text Citations:

[1] Pace Gallery, “Yin Xiuzhen,” Pace Gallery: Artists, accessed April 7, 2024, https://www.pacegallery.com/artists/yin-xiuzhen/

[2] Hon Hanru et al., “Interview: Hou Hanru in Conversation with Yin Xiuzhen,” Yin Xiuzhen (Phaidon Contemporary Artists Series), (London & New York: Phaidon, 2015), pp. 15

Bibliography:

Hon Hanru et al., “Interview: Hou Hanru in Conversation with Yin Xiuzhen,” Yin Xiuzhen (Phaidon Contemporary Artists Series), (London & New York: Phaidon, 2015), pp. 15

Pace Gallery, “Yin Xiuzhen,” Pace Gallery: Artists, accessed April 7, 2024, https://www.pacegallery.com/artists/yin-xiuzhen/

“A Reflection of Time and Changing Radicalism: The First One Hundred Years By Archibald Motley”

By Caitlyn Bains

In Text Citations:

[1] R. Bearden and H. Henderson, A History of African-American Artists: From 1792 to the Present (1st ed.; Pantheon Books, 1993), 149.

[2] Ibid., (1993), 143.

[3] A. Motley Morgan, “Archibald John, Jr.,” in The Oxford Dictionary of American Art and Artists, Oxford University Press, accessed April 5, 2024, https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bu.edu/ view/10.1093/acref/9780191807671.001.0001/acref9780191807671-e-931.

[4]Ibid.

[5] R. Bearden and H. Henderson, (1993), 155.

[6] Alain Locke, The New Negro (1st Touchstone ed.; Simon & Schuster, 1997), 5.

Sources:

Alain Locke, The New Negro (1st Touchstone ed.; Simon & Schuster, 1997), 5.

A. Motley Morgan, “Archibald John, Jr.,” in The Oxford Dictionary of American Art and Artists, Oxford University Press, accessed April 5, 2024, https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.bu.edu/ view/10.1093/acref/9780191807671.001.0001/acref9780191807671-e-931.

R. Bearden and H. Henderson, A History of African-American Artists: From 1792 to the Present (1st ed.; Pantheon Books, 1993), 149.

“ Connecting Two Collections from Panopticon Gallery’s “First Look” Exhibition”

By Emma Claire Everett

Sources:

All quotations are sourced from “First Look 2024” at www.panopticongallery.com.

“An Assault Across Time”

By Gabriella Rice

In Text Citations:

[1] “Little Dancer Aged Fourteen,” Art Object Page: Overview, www.nga.gov/collection/art-objectpage.110292.html#overview, accessed April 7, 2024.

[2] Amy Henderson, “The True Story of the Little Ballerina Who Influenced Degas’ ‘Little Dancer,’” Smithsonian.Com, Smithsonian Institution, November 4, 2014, www.smithsonianmag.com/ smithsonian-institution/true-story-little-ballerina-who-influenced-degas-little-dancer-180953201/.

[3] Ellie Silverman, “D.C. Climate Protesters Smear Paint on Case of Edward Degas’s Sculpture,” The Washington Post, April 27, 2023, www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2023/04/27/climate-protest-paint-degas-little-dancer-national-gallery-dc/.

[4] Giovanni Alloi, “After 38 attacks on art, climate protesters have fallen into big oil’s trap. It’s time to change tack,” The Guardian, February 6, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2024/ feb/06/after-38-attacks-on-art-climate-protestershave-fallen-into-big-oils-trap-its-time-to-changetack.

Sources:

Alloi, G. (2024, February 6). After 38 attacks on art, climate protesters have fallen into big oil’s trap. It’s time to change tack. The Guardian. https://www. theguardian.com/artanddesign/2024/feb/06/after38-attacks-on-art-climate-protesters-have-fallen-into-big-oils-trap-its-time-to-change-tack Henderson, A. (2014, November 4). The true story of the little ballerina who influenced Degas’ ‘Little Dancer.’ Smithsonian.com. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/true-story-little-ballerina-who-influenced-degas-little-danc-

er-180953201/

National Gallery of Art. (n.d.). Little Dancer Aged Fourteen [Art Object Page]. Retrieved from https:// www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.110292. html#overview

Silverman, E. (2023, April 27). D.C. climate protesters smear paint on case of Edward Degas’s sculpture - The Washington Post. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-mdva/2023/04/27/climate-protest-paint-degas-little-dancer-national-gallery-dc/

Winter

“Entry 03282024: The Rain & I” By Jasmin Jin

In text:

[1] Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, “Van Gogh Highlights: The Letters: To Theo v. Gogh and Jo v. Gogh-Bonger, Auvers-sur-Oise, on or about Thursday, 10 July 1890, Letter #898,” accessed April 7, 2024, https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/highlights/letters/898.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, “Vincent van Gogh: The Garden of Saint Paul’s Hospital,” accessed April 7, 2024, https://www.vangoghmuseum. nl/en/collection/s0046V1962.

sources:

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, “Van Gogh Highlights: The Letters: To Theo v. Gogh and Jo v. Gogh-Bonger, Auvers-sur-Oise, on or about Thursday, 10 July 1890, Letter #898,” accessed April 7, 2024, https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/highlights/letters/898.

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, “Vincent van Gogh: The Garden of Saint Paul’s Hospital,” accessed April 7, 2024, https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/collection/s0046V1962.

“Creation and Time: through the eyes of a painter”

By Barrett Walsh

In text:

[1] Milan Art Institute. (2024, March 25). Overcoming creative blocks: 8 tips to get your groove back. Overcoming Creative Blocks: 8 Tips to Get Your Groove Back. https://www.milanartinstitute.com/ blog/overcoming-artist-s-block-8-ways-for-finding-

your-artsy-groove-again

Sources:

Milan Art Institute. (2024, March 25). Overcoming creative blocks: 8 tips to get your groove back. Overcoming Creative Blocks: 8 Tips to Get Your Groove Back. https://www.milanartinstitute.com/ blog/overcoming-artist-s-block-8-ways-for-findingyour-artsy-groove-again

Spring

“Countless Moments on One Canvas: An Overview of Dr. John Durham Peters’ “Earth Montage” Lecture”

By Emma Claire Everett

In text:

[1]Williams, W. (1962). Landscape with the Fall of Icarus. Collected Poems: 1939-1962, Volume II. New Directions Publishing Corp.

[2] Delaney, J. (2010). The Strait of Magellan: 250 Years of Maps. Princeton University Library. Retrieved February 15, 2024, from https://library. princeton.edu/visualmaterials/maps/websites/pacific/magellan-strait/magellan-strait-maps.html.

Sources:

Williams, W. (1962). Landscape with the Fall of Icarus. Collected Poems: 1939-1962, Volume II. New Directions Publishing Corp. Delaney, J. (2010). The Strait of Magellan: 250 Years of Maps. Princeton University Library. Retrieved February 15, 2024, from https://library.princeton. edu/visualmaterials/maps/websites/pacific/magellan-strait/magellan-strait-maps.html.

Park Yunji & the Fugitive Silhouette of Nature By Xinyue Jin

In text:

[1] Park Yunji, “about: yunji park,” yunji park, accessed April 5, 2024, http://www.yunjipark.com/ index.php/about/

Sources:

Artsy (n.d.). Park Yunji - Artworks for Sale & More. Artsy.net.

https://www.artsy.net/artist/park-yunji Yunji, P. (n.d.). about: yunji park. yunji park. http://www.yunjipark.com/index.php/about/