Welcome to the first edition of the

Literature Festival Magazine, featuring new commissioned fiction, poetry and non-fiction from Festival writers and poets Jay Bernard, Joe Rizzo Naudi, Jody Burton, Courtney Conrad and editor Aliya Gulamani,

Welcome to the first edition of the

Literature Festival Magazine, featuring new commissioned fiction, poetry and non-fiction from Festival writers and poets Jay Bernard, Joe Rizzo Naudi, Jody Burton, Courtney Conrad and editor Aliya Gulamani,

Librarian, historian, author and local resident, Jody Burton discusses Deptford’s hidden involvement in transatlantic slavery ahead of her 2024 Festival event: ‘Deptford Dockyard’s Buried History’.

THE FESTIVAL THEME of Untold Stories, Unheard Histories, echoes my Presentation on Deptford Dockyard’s Buried History; and follows on from my audio guide “Black History Walking Tour of Deptford” from last year’s festival. Both of which aim to raise those untold, erased, and marginalised stories to tell a broader British history for all.

Did you know that the roots of the British Transatlantic Slave Trade were established at Deptford Docks?

At St Nicholas’ Church in Deptford; inside this place of worship, you can view two banners titled “Deptford Ships” which document Deptford’s maritime history. One banner lists the ships built from 1551-1869 and

the other summarises the history of shipbuilding. Neither has any reference to the “human trade” they dealt in. Over 3,000 slaving voyages departed from the stretch of the Thames between Deptford Docks and Greenwich during the period of transatlantic enslavement. Two of the ships listed are named at the Transatlantic Slavery display at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. A third listed ship. The Primrose, is highlighted by Joan Anim-Addo in her book Longest Journey, A History of Black Lewisham by Joan Anim-Addo (1995), as forming part of the first fleet of ships to make contact between England and Africa.

As a result of this erasure, I nominated St Nicholas’ Church as part of

the 50 Plaques and Places project run by Transatlantic Trafficked Enslaved African Corrective Historical Plaques (TEACH). This project, founded by Gloria Daniels, highlights 50 sites tied to the transatlantic slave economy. 50 plaques have been created from 50 testimonials which Daniels hopes will be accepted and installed at their respective sites. I was one of the contributors which also included Bell Ribeiro-Addy MP, Poet and Activist Linton Kwesi Johnson, and musician Dave Okumu. Okumu is an alumni of Goldsmiths

University and his plaque references the Deptford Town Hall building, now part of the university campus. The building is decorated with statues of naval figures who had connections to the Transatlantic Slave Trade, including Sir Francis Drake. In recognising this building’s history, Okumu also highlights the Goldsmiths AntiRacist Action Group (GARA) which protested and demanded acknowledgment of this history.

In 2021 Lewisham Council established Black History Lewisham 365

to champion Black History all year round. In 2023 Arthur Torrington CBE, Director and Co-Founder of the Windrush Foundation and Equiano Society, was awarded a Mayoral Special Recognition award for his contribution in championing Black history. The Equiano Society seeks to educate and celebrate the life and work of Olaudah Equiano, who was born in Nigeria and enslaved as a child. In 1762, during naval service, he was kidnapped at Deptford Docks and resold into enslavement. Equiano went on to become a prominent Abolitionist in London and used his autobiography The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano (1789) to champion the anti-slavery message. He has numerous memorials including in central London, Lewisham, and Greenwich, and is one of the few Black figures known in British history.

However, how many people locally or nationally are aware of the historical significance Deptford Docks played in the British Transatlantic Slave Trade? Its significance was not something I was attentive to nor has it been a narrative of British history that is widely told. I hope that through my work exploring Black history across London, as well as initiatives like TEACH — and their two nominated plaques in Lewisham — we can provide further steps towards continuing the conversation and widening the

education and acknowledgment of our shared history.

As the back cover of Joan Anim-Addo’s book Longest Journey; A History of Black Lewisham states:

“This is Black history, This is British history, There is no contradiction…”

JODY BURTON is a historian, librarian and writer who has worked in both public and college libraries. Prior to this, her background was in adult education. She is the co-author, with Avril Nanton, of the Black London History Map and Black London: History, Art and Culture in Over 120 Places.

Both Jody and Dave Okumu’s plaques will be on show at Deptford Town Hall until 22 March 2024. Her audio guide Black history walking tour is available at: spreadtheword.org.uk/ black-history-walk

I made to my barber. I’d spent Christmas in Devon, out in the countryside, then my train back to France was cancelled, so I was stranded in London and ended up staying much longer than expected. Those unplanned days turned out to be a blessing. For one, I got to walk around London and ended up on Watergate Street, by the Thames. As well as a platform that allows you to look towards Greenwich, there’s a set of stairs that leads down to the foreshore. It’s not a secret – there is plenty of graffiti, including one suggestion that it’s a good place to bed down – but it feels secluded and exhilarating.

On this particular afternoon, I was trying to work out why. The river was far out, almost as far as the jetty,

and the tiny beach was like a spade, scooping green water. After a few minutes, the waves suddenly came in harder – two, three, four gallops at a time. Would I be submerged? Would the water come pouring in quicker than I could run? This was exciting. But it wasn’t the only thing: the other thing was that there was nothing between me and the river. The stairs were wet and slippery, there was glass, there were pointed sticks jutting out of the sand. If you did jump into the water, your feet and legs would be cut open for sure. But regardless of whether I was there, the water was making its slow creep upwards, according to the pull of the moon, and everything about this place spoke clearly of an earlier time, when these were working docks, when the city still had its secret parts.

I went to the Dog and Bell for an early dinner, then called my barber and asked if he was able to see me. He said yes, so I started walking up Watergate Street to John Evelyn Street, named after the famous diarist who watched the great fire of London from this very neighbourhood. Writing from Deptford in 1666, after the fire had razed much of London, and Evelyn had sent a letter to his friend Samuel Tuke, in Paris:

The miracle is, I have never in my life observed a more universal resignation, less repining amongst sufferers; Judgments do not always end where they begin; and therefore let none exult over our calamities. We know not whose turn it may be next.

At the end of Deptford High Street, I took a right down Edward street, which took me through old Fordham Park. I’d spent a long time here, by the New Cross memorial stone in particular; during the lockdowns it had been an occasional respite from the monotonous triangle of Ladywell Fields, Blythe Hill Fields and Hilly Fields. I went up Clifton Rise, then right onto New Cross Road. As well as the house, which is ever present in my thoughts, I remembered Magda Pniewska, who had been killed in a gunfight near here many years ago, and how that strange English law, joint enterprise, had been used to convict one of the boys involved. He

had not fired the gun – that assailant was unknown – but he received a life sentence since he could have foreseen the lethal outcome of his crimes. I thought about how frequently you hear shouts, shots, disturbances; the sonic world in which lives begin and end.

Then I followed the road past the station, past the old post office, past the Latin mall, and on the corner, there was my barber. An unassuming little place, with a Western Union office in the back. It was close to the new year and the place was deserted, but the TV was on, and he was happy to see me. It had been years since I’d come by, being an economic migrant and all. I told him about how much I’d moved, about how difficult it had been to find a decent place to live, how much easier it was to make a

life in Europe, and that I wanted the usual (if something can be called the usual after so long a break): a nice, tight skin fade.

He got to work, with his familiar concentration, staring into the side of my head like it was a book. As he made white dents on my temples to begin the line-up, I suddenly asked where everybody was. He laughed: Yeah, it’s quiet, nobody has money, so they stay indoors, usually, new year’s eve, there’s a big queue, but not tonight, London has gone down, it has really gone down, cost of living,

yeah, but this city, it’s just not what it used to be, everyone depressed, broke, no-one feels like celebrating.

Outside, it was very quiet. Ordinary traffic. In previous years I could remember people dressed up – sparkly pom-poms, short dresses, lads in t.shirts. I could remember groups of teenagers drinking on the bus. As he sprayed my face with alcohol, I thought about how grateful I was that he was still in business, that the pandemic hadn’t killed him off and nor had this disappointing Christmas. I thought about how little

community I had in London – how threadbare things had become. This barber was a little light.

*

I was there again not long after. This time, the place was full. End of the month, maybe people had just been paid. The TV was blaring, a younger guy was charging his phone in the corner. Seated next to the barber was a man, clearly a friend, with his legs spread out, stroking his beard, watching the news. A headline about possible British conscription in a fight against Russia had just ended, and this man, who I will call the Philosopher, turned to everyone and asked who’d be willing to fight for this country. Nobody answered yet everyone did. It is a peculiar talent that some people display, to suddenly begin speaking to an audience of strangers and to speak without any reply: I am an African, when I came to this country I had no idea what racism was, but when I learned about what this country did, when I discovered what they did to our countries, I said I would come here, make my money, and go home, because you know what this country does, it takes you, it chews you up, then when they are done with you, it spits you out.

The barber had just finished the guy in the chair, and as he pulled the cover off his shoulders with a dramatic flourish, the man stood up and began speaking: I’m South African, but my

brother he came to the UK to fight in the army, twelve years, he pledged allegiance to the queen, gave up his South African passport in order to do so, but you know what happened after that, he decided to leave because he’d seen too much shit, but after twelve years of service, the government wouldn’t give him a passport or leave to remain, so now he’s stateless, he can’t go back to South Africa.

Stateless? It was a strange story. But then you hear strange stories on the barbershop floor. Maybe here, more than anywhere else, the nugget of truth at the centre is core to the performance. Philosopher saw me taking notes (I was googling British military citizenship requirements) and asked if I was some kind of writer or poet. Everyone, including the Barber, turned to me. I said no. His eyes were wide open, it seemed, but he was seeing what he wanted to see. I was the smallest person in the shop, writing in a notebook with pastel coloured paper, with my legs crossed. Of course I am a writer. But I have only the slightest beard, which people take for youth, and, paradoxically, a large vocabulary, which people respect as age. I could see myself flickering in the Philosopher’s eyes.

There was another boy, just getting up to sit in the chair now, who was no older than eighteen. He had thick eyebrows, thick eyelashes, wisps of wiry hair were growing from the

corners of his upper lip. Everything about him was thin, solid, like a sapling. It’s hard to explain to others, but after years of passing in gendered spaces, you learn to blend in to your surroundings. You learn to act under the radar, to hide in plain sight, to use to your advantage all of the characteristics that preclude any possibility of being something other than what you are, in that space, supposed to be. I put my notebook away, leaned forward, stretched my shoulders, and looked up at the TV. Maybe his eyes lingered for a while longer, but the conversation moved on.

Philosopher: Would you fight for these people, were you born here, would you go and kill yourself for people who would chew you up and spit you out, do you know what these British did in Jamaica, have you read about that, if you can get another passport then make sure you apply because you will need to run somewhere, me, I am going back to my own country, the minute they say war, I’m packing up.

A feeling was gathering inside of me. The news switched to Palestine — the familiar image of a young man running with a child in his arms.

Then the scale of the devastation, shot from above. I wanted to say, yes, I am from London, and no, I don’t know where I’d go if there was a war. I don’t know who I’d fight for, and I don’t know where I’d run. But I stared out of the window — ordinary traffic on an ordinary night. New Cross Road has its own sound, its own air, which for me is both comfort and dislocation. The barber called me up, wrapped my neck with a paper collar, shrouded my body with the cloak, and began mowing strips of hair that fell in clumps around me. I didn’t speak.

*

I caught my train at eight o’ clock, and a few hours later arrived at my apartment in Place de la Nation – a tiny, grubby studio with a concealed but potent sewage problem. I opened

a gin and tonic. I lit some smoky incense. I flushed the toilet before using it. (Lesson learned: never look). I opened the sliding door and stood outside. Another year was in full swing, and I was no closer, no clearer, no surer. Now that I was alone, the feeling that had started in the barber’s chair began to widen in my chest. I was a writer, but I had nothing to say to those guys. The Philosopher had asked me directly and I’d lied. What were my poems worth if I couldn’t admit to them on the barbershop floor? What other forum was as urgent? What other question was as present? Then the cat from next door came bounding out of the bushes and nudged me with its little flat face. I was alone in Paris, longing for London, a place I can’t seem to live in or leave, condemn or defend, even as the water gets higher, closer.

JAY BERNARD is a writer and interdisciplinary artist whose work explores issues of queerness, race and archiving through a critical lens. Their short films, artwork and literary collections have been exhibited at film festivals and galleries around the UK, and they were the recipient of the 2020 Sunday Times / University of Warwick Young Writer of the Year Award, and the 2017 Ted Hughes Award.

As part of Deptford Literature Festival 2024 Courtney Conrad and Lola Oh worked with Caribbean Elders from Entelechy Arts’ Meet Me at The Albany project; creating and sharing poems and stories of the Caribbean and migration. These are collected in an anthology Talk di Tings Dem, edited by Courtney and Lola. This poem by Courtney Conrad is inspired by that project.

COURTNEY CONRAD is an award-winning poet born and raised in Jamaica and currently based in London. Migrating from Kingston as a teenager, Courtney’s poetry interlaces subversive diasporic image, national political commentary and shatteringly personal narrative. Her poetry seeks to sensitively archive the political corruption and violence she witnessed as a young girl in Jamaica in the wake of its colonial subjugation under the British Empire. Courtney is unflinching in her attempts to uniquely capture the vibrance and violence of her experiences in the UK and Jamaica. Courtney holds a BA and two MA degrees. She is currently working on her debut collection.

The red room was like my Granny’s kitchen.

Elders huddled around a mahogany table; some crocheting and drinking fish tea soup as they took turns serving stenchful stories that had been rotting inside them for years.

Their brains, archival libraries from different Caribbean islands. They never grew tired of repeating introductions and endings for one another when eardrums gave way. Their hardships and perseverance birthed casual tones, one word away from a tearful one.

These women spoke of underground nightclubs in living rooms, butterflying their way out of maggot-filled realities of employers, neighbours and strangers who treated them like garbage bin gunk; devilish men who took their bodies and voices in alleyways,

offices, family homes. Their truths hushed and only spoken of in prayers. These women left one hardship and landed into another. All of a sudden, I cared less and less about frivolous tell-all celebrity gossip. With each story, my palm reached for my chest, grateful that these women’s courageousness contributed to transporting me from the Caribbean to England; arriving to be met by fewer trials and tribulations.

Inspired by Talk di Tings Dem, Courtney Conrad and Lola Oh will be running a workshop exploring Caribbean migration beyond stereotypical narratives at Catford Library on Saturday 13 April 2024, for tickets see the Festival website. The Talk di Tings Dem anthology is available to read on the Festival website: deptfordlitfest.com

Aliya Gulamani, Commissioning Editor at Unbound, provides an insight into the industry, which she’ll be exploring in more depth as part of the ‘Meet the Editors’ event at Deptford Literature Festival 2024.

when I say I work in publishing, particularly as a commissioning editor, that I must be reading all day long.

While reading is an important aspect of my job, as a commissioning editor, you’re involved in the entire process of bringing a book to life. Every commission starts with a submission. If it’s a fiction book I need to see the entire manuscript, if it’s non-fiction then a proposal with some chapters is ideal. Rejections are always hard. It can be a case of needing the right fit, the right team, and the right commissioner to champion your book. Other times, the writing needs more work, or the idea needs more finessing. And sometimes, it is all about timing; publishing follows trends and we’re more likely

to publish a book if we know there’s a definite readership for it.

When we find a book that we really like, we’ll make an offer. This can sometimes mean going back and forth on contract negotiations before agreeing on the definite terms. The book is then put into the pipeline schedule with publication dates tentatively pencilled in. There’s a lot of discussion on the best time to publish because we want the book to be in the market at the right time, so it has the optimum chance of reaching its audience. What I’ve learnt over the years is that publishing is essentially a business — a business about books. There’s a lot of strategic thinking as well as a bit of luck involved in the process.

Commissioning editors’ responsibilities are different to book editors’ - we work closely together but the book editors are responsible for steering the book through the editorial and cover design process, which everyone feeds into. Genuinely, everyone. Our Sales, Trade, Marketing, PR, and Editorial departments attend our covers meetings where we go back and forth to get a cover right. Typography, colour schemes, to illustrate or not to illustrate? These are all the things we discuss at length. We’re looking to create a cover that will stand out but also blend with its comparative titles in the market. All of this takes time - forget what you’ve seen in the feel-good movies, publishing lead times are very, very, very long.

advise authors to create their own platforms. As every reader will testify to, readers like to feel connected to writers and when this is in play, it can make a real difference.

Perhaps all of this feels a bit corporate, a bit cold and distant from the heart and soul process of writing a book. In truth, it sometimes is: we’re making decisions based on an existing marketplace for books, and we’re crafting endless strategies to find the book’s readership. Everyone in a publishing house looks after a different element of the business, and collectively we make it work efficiently. And we do need to talk about profit - not because making money enables us to keep publishing books, but also because when we make money from books, so do our authors.

“ ”

And that’s when the reading comes into it. Books change lives. They keep changing mine.

Closer to publication dates, commissioners will feed into the sales, PR, and marketing strategy for the book. We want to make sure we get as many eyes on your book in the run up to the pre order campaign and post-publication. Often, it’s useful if the author has networks of their own that can boost this process, which is why we

However, underneath all of this is a genuine human drive. And that’s when the reading comes into it. Books change lives. They keep changing mine. I relish the moments when I’m reading a submission that makes me tear up, teaches me something new or transports me into an entirely different world. In every publishing

house, all our endless meetings and discussions are triggered by this urge, this need to connect readers to the book, to ask them – to keep asking them: “do you feel what I felt when I read this?”

ALIYA GULAMANI (she/her) is an awardwinning commissioning editor at Unbound –the world’s first crowdfunding publisher. She is also the Editorial Lead for Unbound Firsts, an imprint for debut writers of colour. In 2022, Aliya was selected as one of the Bookseller’s Rising Stars and awarded The Ola Gotkowska Young Independent Publisher of the Year Award. Aliya is also a manuscript assessment reader for The Literary Consultancy, and is currently a Trustee at Bookworks.

A recorded stream of the Meet the Editors event is available until Sunday 24 March 2024 on the Festival website: deptfordlitfest.com

London writer Joe Rizzo Naudi utilises 19th and early 20th Century texts for an unusual found poem.

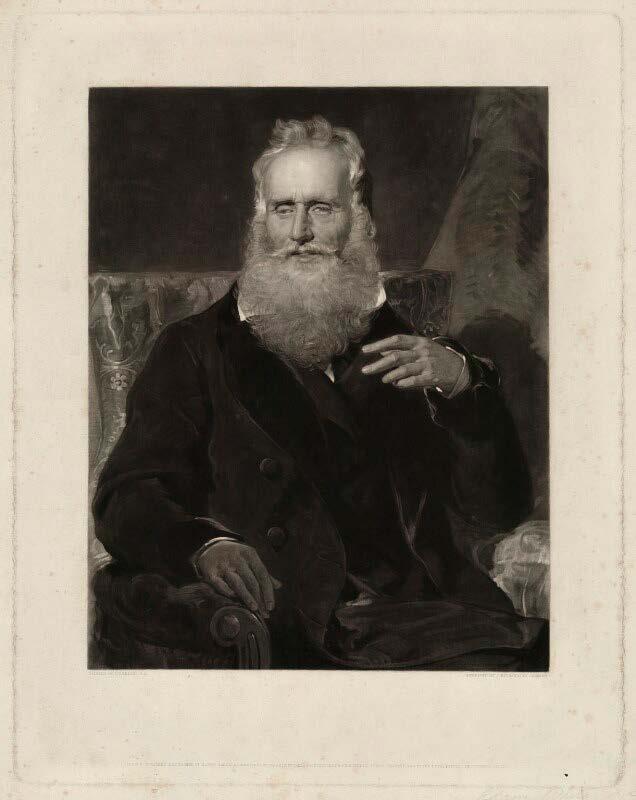

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: An older white man with a voluminous white beard. He sits comfortably, facing us and with his left hand raised as if to emphasise a point he is making or to gesture towards his beard. Beneath halfopen lids, his left eye looks in our direction while his right eye is cast downwards and askance.

James Holman (1786-1857) by John Richardson Jackson, published by Henry Squire & Co, after John Prescott Knight, mezzotint, published 23 May 1849. NPG D37565. © National Portrait Gallery, London

1

He and the others arrived in Valença at nine, where they stopped for breakfast and where nearly all the town’s inhabitants collected to comment upon them. It so happened that he was the principal object of curiosity, with this unlooked for distinction arising from two circumstances. First, his wearing of a long beard and secondly, his blindness. These peculiarities produced numberless exclamations—such as, how could he travel, why did he travel, why did he wear such a beard and so forth—until they became so pressing that he was glad to get within closed doors. 2

He could well understand that a simple people—whose experience was limited to their own habits and who had never had an opportunity of intermixing with other nations—might indeed be startled by the novelty of a beard

although their astonishment at the sight of a beard

was not greater than his on discovering that they were destitute of such a dignified appendage, which in the torrid zone was at once an article of comfort and utility.

3

After a day’s long journey, the luxury of immerging his face in cold water and leaving the beard

half dry was most refreshing, the evaporation producing a reviving and agreeable effect.

4

Alone in Doctor Dickson’s carriage, he was greatly surprised at the noise and confusion caused by fire-works in the street, crackers as loud as blunderbusses, and rockets so close to the carriage that he began to be alarmed for his beard

only afterwards learning, upon inquiry, that this was the third and last day of a religious festival at one of the principal churches in Rio.

5

It was understandable, he thought, that in the absence of her husband, the lady would be alarmed at the uncommon if not barbarous appearance of his beard

which gave him a very ferocious and brigand aspect.

6

He was not at all satisfied with the state of his head, while his denuded nose and lacerated lip were rendered very painful by the contact of the night air, and he was therefore

most sincerely thankful when the barking of dogs gave signal that he and the slave boy were approaching the environs of Cape Town. He spread alarm and consternation through the household, however, when he presented himself without a hat and with a silk handkerchief bound round his forehead, and with his clothes, face and beard covered in blood, and the little black boy trembling by his side, fearing punishment for his disasters.

7 And yet he could not forbear smiling at the curious picture their party must have presented to European eyes: Don Bastian, with his black face, attired in a sort of demiBritish fashion, his head uncovered, his long black hair plaited and turned up like a woman’s with a comb, while a servant held a huge umbrella over his head; and he on Don Bastian’s arm, dressed in a short drab jacket, brown moleskin pantaloons, blue waistcoat, white boots, a broad brimmed straw hat and a long beard the tout ensemble well powdered with dust.

8 He was next seen at the consul’s house preparing to depart, sitting on his mule with the guide he had hired alongside him, his strong

frame, his manly English face, his sightless eyeballs and his grey beard

giving him a noble appearance in the crowd of wondering Sicilians.

9 As they left the table d’hôte, a ministering garcon informed them that a blind gentleman had caught English accents at a distance and wished for the pleasure of speaking with fellow countrymen. They went to him and found a venerable man with a long beard who introduced himself as Mr. Holman, the blind traveller, on his way to Egypt. He averred that in the vicissitudes of the atmosphere and the feelings suggested by unseen objects, he perceived all the varieties of nature and art that could be detected with the eyes.

10

Knowing both men familiarly, Mr. Jerden took an opportunity to introduce them to each other, and as the one was blind and the other could not see, he advised the cultivating of a further intimacy by the mutual stroking of beards a ceremony they performed with hearty laughter, and to the no small amusement of a little circle of admiring spectators.

NARRATIVE OF HIS BEARD is a collage text composed of edited extracts from: A Voyage Round The World by James Holman, 1834; Vacation Rambles & Thoughts by T. N. Talfourd, 1845; Men I Have Known by William Jerden, 1866; and Francis Parkman by H. D. Sedgwick, 1904.

JOE RIZZO NAUDI is a London-based writer, curator and facilitator. In 2022 he was awarded a London Writers Award by Spread The Word and received an Arts Council England grant to develop literature and performance projects exploring blindness. He has presented his work at the Wellcome Collection, the BFI Southbank, Brixton House, Vault Festival, Rich Mix and the ICA.

Sounding Deptford, a self-guided audio walk created by Joe and poet James Wilkes for the 2024 Festival is available via the Festival website deptfordlitfest.com

IMAGE DESCRIPTION: A bearded, smiling white man in his mid-thirties wearing a denim shirt and jeans. He sits in front of a microphone and holds a mobile phone.

Spread the Word has a big, bold vision to see Lewisham declared as the UK’s first Borough of Literature. We are launching a campaign to bring this to life – do you want to be part of it?

Did you know that Lewisham is already...

• Rich with word-related creative activities.

• Home to some of London’s best new writers and famous authors.

• Home to many arts charities and working with words, stories, and poetry.

What’s next?

We want to create our Borough of Literature for and with participation from all of Lewisham’s community, from school children to elders, community groups to businesses, open green spaces to public buildings. Whoever and wherever, we would like you to be involved.

Throughout 2024, Spread the Word will be hosting Open Houses (public meetings) with local communities and recruiting an Advisory Group to find out: what would a Borough of Literature mean to you? And why is it important for Lewisham? We have some ideas, but we want to hear yours!

Get involved

We would love to talk to you about our ideas and yours for the Borough of Literature, and how the project will roll out.

• Follow us on social media and keep up to date with #BoroughOfLiterature

• Sign up to our newsletter to see news as it comes out

• Sign up to help make Lewisham the Borough of Literature

Instagram: @spreadthewordwriters Facebook: @spreadthewordwriters Twitter/X: @STWevents

Find out more at boroughofliterature.com

LITERATURE FESTIVAL celebrates the diversity and creativity of Deptford and Lewisham through stories, words and performance. It is run by Spread the Word in collaboration with creative producer Tom MacAndrew, and funded by Arts Council England, with support from The Albany and Deptford Lounge. The festival takes place in locations across Deptford and features local literary talent and organisations. It explores what literature means to us in South East London, and includes a programme of workshops, talks, walks, readings and performances. It aims to offer something for everyone; whether you’re an experienced reader or writer, or just want to have a go. deptfordlitfest.com

TOM MACANDREW is a freelance producer specialising in poetry, spoken word and live literature. He has developed work for organisations including Apples & Snakes, BBC Arts and BBC Radio 4, the British Museum, Forward Arts Foundation and World Book Day. He produced three series of the Bedtime Stories for the End of the World podcast and edited an accompanying illustrated book; and he currently runs Propel Magazine which promotes work by emerging poets. He has developed and toured shows nationally and internationally with poets including Joelle Taylor, Adam Kammerling, Joshua Idehen, Francesca Beard and John Hegley. Tom is the producer for Out-Spoken, London’s largest regular poetry night, resident at Southbank Centre, and for their publishing house OutSpoken Press. He is a trustee at the Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre. tommacandrew.com

SPREAD THE WORD is London’s literature development agency, a charity and an Arts Council England National Portfolio Organisation. We create opportunities for storytellers, creatives and readers to change the conversations we have and reimagine the world we live in by running inclusive creative writing programmes and offering practical ways for writers to get their work into the world and discovering Londoners who love words and nurturing those who want to write, read and share stories. We initiate change-making research including Rethinking ‘Diversity’ in Publishing (2020) and Access to Literature (2022) and developing programmes for writers that have equity and social justice at their heart. Our work includes: the London Writers Awards, the Early Career Bursaries for London Writers, Nature Nurtures with the London Wildlife Trust, Uprising and Resistance with Ink Sweat & Tears, John Hopkins University and Black Beyond Data in collaboration with Lloyds of London, CRIPtic x Spread the Word Salon, Young Writers Collective, the Disabled Poets Prize and Deptford Literature Festival. spreadtheword.org.uk

Deptford Literature Festival celebrates local talent and introduces exciting new writers from Lewisham and nearby boroughs. The majority of the workshops, events and community projects are free to join. We do not want finances to be a barrier to anyone taking part.

If you are in a position to make a donation, please give a gift today. Anything you give will help more people come to future Festivals for free. Our typical ticket price, without donations, is £10.

Please give what you can through this link: www.totalgiving.co.uk/appeal/deptfordlitfest or via the QR code below:

Make a donation:

Tell us what you thought:

We’d love to know what you thought of your experience at Deptford Literature Festival 2024. By completing the feedback form you could win one of 4x £20 book tokens.

They’ll also be opportunities for you to share your ideas for future Deptford Literature Festivals.

Give your feedback through this link: www.surveymonkey.com/r/DeptfordLitFest2024 or via the QR code above.