Germaine Tailleferre

Margaret Bonds

Teresa Carreño

Tania León

Joan Tower

Hildegard von Bingen

Kaija Saariaho

Laurie Anderson

Alma Mahler

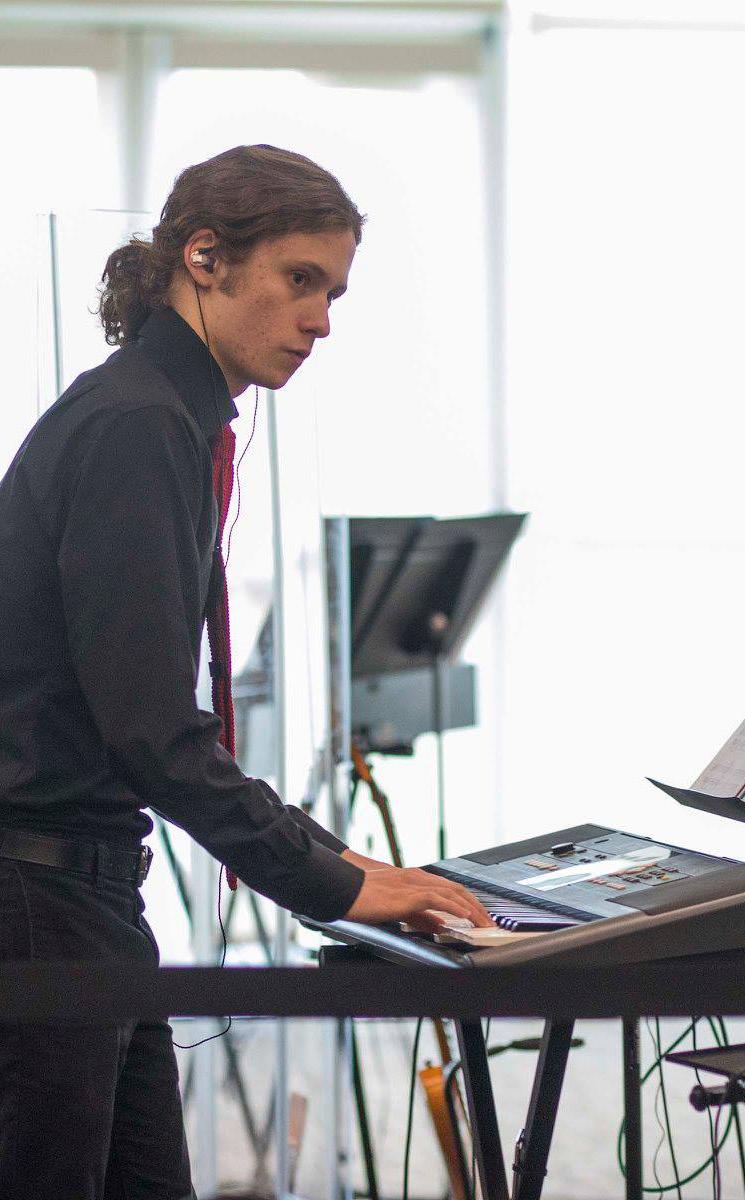

Rachel Lanik Whelan

Belonging In All Places Music is Being Made Evolution of equality in classical music

Rachel Lanik Whelan Contributing Author

A Little History and Context It seems too obvious to say aloud: women and nonwhite people have been creating, writing, and making music throughout history and today, yet most orchestral seasons focus on the music of dead White men. When I started composing music in high school, I began to notice how infrequently the names on concert programs looked like mine, how the dates next to these names indicated years of centuries past. As with most professions before the mid-20th century, women and people of color in Western society were not provided the opportunity to acquire skills that might allow them to have self-sustaining careers as composers. The disproportionate number of white male composers speaks more to the values of society throughout history than it does to the quality of music written by the women and composers of color. We’re fortunate to live in an era where anyone can be encouraged to compose and perform music as a career, but programming efforts haven’t yet caught up with the wide range of contemporary music available. In the last ten years there have been increased efforts to diversity programs to include works by historically underrepresented composers. The Institute for

Composer Diversity published an analysis of 120 orchestras and their concert programming of the 20192020 season. The data showed that 8% of the music programmed was by women composers and 11% of the music programmed was by composers from underrepresented racial, ethnic, and cultural heritages. The study also found that the most performed composers of the 2019-2020 concert season are all white European men, most of whom have been dead for over a century. A similar statistic is true for programming at Spartanburg Philharmonic, with the most performed composers being Brahms, Mozart, John Williams, Tchaikovsky, and Beethoven. The music of these composers is wonderful; we’re captivated by the power, drama, and emotion of these classic works. But doesn’t an audience in upstate South Carolina have more in common with living American composers, women composers, and Black composers than they do with dead German composers? Don’t we feel more connected to the music when the composers and performers are expressing ideas which relate to us more personally? continued on page 27

25