24 minute read

Zimmerli Series: Glorious Fanfare

SATURDAY

March 20

Advertisement

Online Premiere @ 7:00 pm | my.sphil.org/watch 2021

Study in Grieg . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .Jocelyn Chambers 2 min

Concerto for Two Violins in D minor, BWV 1043 . . . . . Johann Sebastian Bach Callie Brennan, violin 17 min

Haelee Joo, violin Alvoy Bryan, viola Ian Bracchitta, bass Brianna Tam, cello Brennan Szafron, organ

I. Vivace II. Largo ma non tanto III. Allegro

Sinfonia Concertante in D Major, Kr. 127 . . . . . . . Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf 8 min I. Allegro

Dissent . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Peter B. Kay 7 min

Concerto for organ, timpani and strings in G minor, FP 93 . . . Francis Poulenc 20 min

Study in Grieg Jocelyn Chambers

(1997-)

Readers with friends or family members prone to muttering crankily that young people today have no sense of gumption, no get-up-and-go, no drive, would do well to arm themselves with the work of Jocelyn Chambers. At the ripe old age of 23 she has hosted a series of podcasts, written a book, and for 12 years run a small pop-up bakery currently based in Austin Texas. (It delivers locally but doesn’t ship, which is a shame because the Lemon Rosemary Cake looks killer.)

And those are, as they say nowadays, her side hustles. Her main gig is composing, and in the last two years she’s scored films and had her music performed by organizations all over the country. Of Study in Grieg she writes:

Study in Grieg was written for my first course in UCLA’s film scoring certificate program: Scoring for Strings. We were given three assignments for the quarter — to write a string quartet, quintet, and sextet — and each piece would be written in a different style of classical music. This assignment called for the romantic style and we had to choose between Grieg and another composer (who I don’t remember at the moment) to emulate. I chose Grieg because he’s responsible for my favorite piano concerto.

We only had one week to write the piece because each assignment was professionally recorded. I wrote it into my engraving software which came with preloaded mediocre instrument samples. The quality of the samples distracted me from creating, so I chose to mute my laptop altogether and trust myself to hear the music on my own. What you hear today is the finished result.

This is one of my favorite pieces for two reasons. One: It contains constant rhythmic motion and compelling melody. Two: It’s a manifestation of the truth that I can write good music on a deadline. When I started UCLA’s program, I wasn’t sure I was cut out for the work. And this piece of music says that I am. I enjoy listening to Study in Grieg over two years later, and I hope you enjoy it, too.

Get to Know Our Principals MORE Learn a little something about our principal players who are Get to Know Our Principals featured on our March 20 concert Glorious Fanfare (see page 38).

Alvoy Bryan Principal Viola

A. The Henry Purcell Room in the Queen’s Hall in London. It was the first time I performed outside the country.

Q. What is your most bizarre talent or skill? A. I have a photographic memory.

What makes a piece of music great? Musicians, theorists, and philosophers from Plato (in The Republic) to Barry Manilow (In “I Write the Songs”) have offered their ideas on the subject, but we have yet to arrive at an answer.

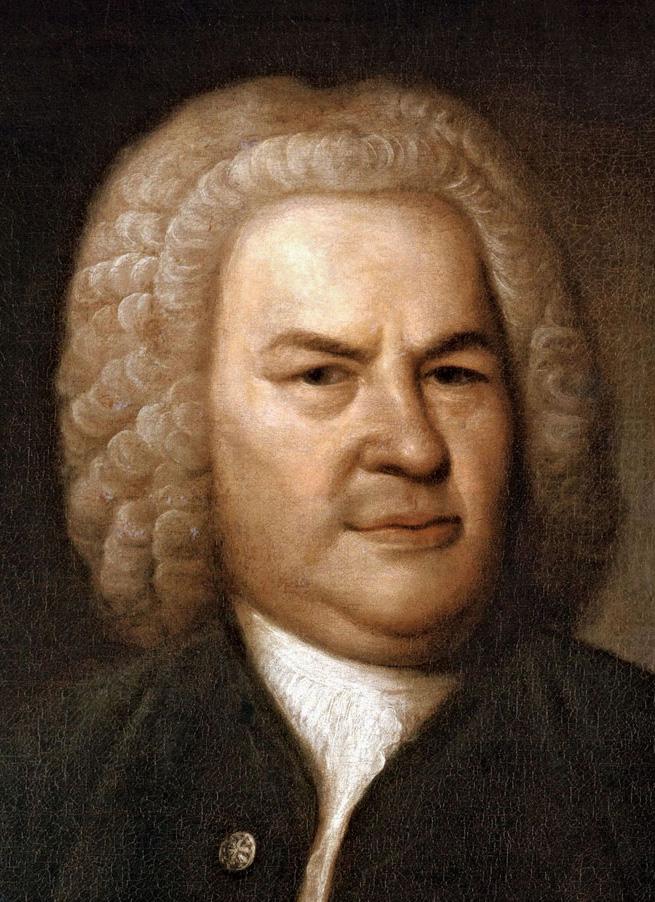

Or, more to the point, we have yet to agree on an answer. Is it, as Plato proposed, the music’s value as an agent of moral uplift? Is it a piece’s originality of conception? Is it a piece’s power of its listeners’ emotions? Is it a product of something a little more nebulous, like the music’s seemingly inherent, organic unity? Or is it ultimately undefinable – something we simply know when we see it, to paraphrase Potter Stewart’s definition of another subject entirely? Whatever the definition and whatever the standard, though, it’s almost impossible not to apply the term to the finest work of J. S. Bach.

And this concerto is surely among his finest work. Written around 1730, it would have received its first performance in – remarkably – a coffee house. Bach was at that time Music Director in the prosperous German city of Leipzig, and while the duties of his post would have stunned a lesser person (among other things, he was responsible for creating and seeing to the performance of a new cantata each Sunday at the city’s main church), he managed to find time to lead the city’s Collegium Musicum as well. The Collegium Musicum was a group of proficient instrumentalists who gathered to perform secular music on a more or less weekly basis. In 1730 public concert halls were still a thing of the future, and the group chose the next best thing: the city’s biggest coffee house. But notwithstanding the decidedly secular setting of its first performance, there can be little doubt that Bach – sincere Lutheran church musician that he was – intended the piece to be morally educative as well as engaging. Bach repeatedly endorsed Johann Mattheson’s suggestion that even instrumental music must “represent virtue and evil… to arouse in the listener love for the former and hatred for the latter. For it is the true purpose of music to be, above all else, a moral lesson.” These moral lessons were taught through the combination of key area, rhythm, and form. Each of those musical elements had extramusical associations, usually with emotional states: the key of D minor, for instance, was closely associated with religious devotion, while ritornello form invoked constancy.

So it’s likely no coincidence that Bach chooses D Minor as the concerto’s home key, nor that its first movement is a perfect example of ritornello form (wherein sections where the full orchestra states the main theme recur, like a refrain, alternating with contrasting sections where the soloists explore new melodic ground). In the concerto’s second movement the two violins unite in a soaring love duet in the key of F (one associated with pure love and the calm of heaven), and we can imagine that here Bach is telling a story of two faithful lovers – or perhaps a soul constant in loving faith – experiencing the bliss of heaven. In the exuberant closing movement the soloists dance together in close imitation, and we can be sure that we’ve found a work on whose greatness even Plato and Barry Manilow would agree.

Concerto for Two Violins Johann Sebastian Bach

(1685-1750)

A. Learning how to record and edit videos.

Q. When driving or traveling, do you prefer music or podcasts and what’s your go-to choice?

A. Podcasts: Questlove Supreme, Expeditiously,

All The Smoke, and The David Banner Podcast

Q. What would your perfect day look like?

A. Wake up and walk/jog for 3 miles. Have breakfast with my wife and children. Play video games with my children. Have lunch with my wife and kids. Watch a movie with my wife and kids. Have a nice dinner with my wife and kids. Smoke a nice cigar and have a beer with my wife to end the day.

Sinfonia Concertante Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf

(1739-1764)

“Canonicity.” If you were, for whatever reason, paying attention to the literary world in the 1990’s and 2000’s, you might remember that this word came up a lot in debates among academics. You’d be forgiven for having forgotten it, though: after all, what reason would you have had to think that it would impact your life?

Well, it turns out that the question of canonicity rears its head in many places in the cultural world, and even a casual music lover is impacted by it. Canonicity is how we determine the answer to a central question in studying any kind of art: time being limited, how do we decide what to study? Or what to read, or what music to teach our students, or what art to show them?

The works we decide to teach to our students are, after all, usually the ones our teachers decided were worth teaching us – which were usually the ones their teachers decided were worth teaching them, and so on and so on, back through the years. Those works are canonical. From the Classical era of music, for instance, Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven have for over two centuries constituted a canon, their music being familiar, beloved, and performed consistently in concert halls around the world.

But we all have only so much time, of course. Musicians haven’t got the time to learn all the thousands of pieces written for their instrument during that era, and audiences don’t have time to listen to them all. This means that, if a composer isn’t quite good or lucky enough to enter the canon soon after his or her death, it can get harder and harder to break into it as generations go by – and so a lot of really good composers are practically forgotten about.

Exhibit A: Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf. Carl Ditters was a hugely successful composer in the Vienna of Haydn and Mozart, and in fact was a good friend and frequent chamber music partner of both. He acquired the second surname “von Dittersdorf” when Emperor Joseph II – among his many fans – elevated him to the nobility (an honor even Haydn and Mozart never attained). As prolific as both his contemporaries, he wrote over 120 symphonies and dozens of operas– most of which are now completely unknown, as there was just no room in the canon for them. Most have been catalogued and are awaiting revival.

One hopes they will be, and soon, for a couple reasons: 1) their titles are hugely intriguing – what could an opera called Die 25000 Gulden, oder im Dunkeln ist gut munkeln even be? And 2) what we know of Dittersdorf’s music is tremendously charming. The Concerto for Viola and Bass is less neglected than most of his music (probably because neither Mozart nor Haydn wrote for that combination), and its commitment to the charms of unbroken melody is more absolute than either Mozart or Haydn was willing to make. Its language is familiar but its voice is unique, and it offers rewards to all of us willing to broaden the range of our musical canons.

Chris Vaneman

Contributing Author

Brianna Tam Principal Cello

Q. What is your ultimate comfort food?

A. Ask what you can provide for the music, rather than what the music can provide for you.

On the evening of September 18, 2020, the Spartanburg Philharmonic gave an extraordinary performance of Beethoven’s third symphony… to a completely empty hall. With a global pandemic still raging, the doors of Twichell Auditorium remained closed to the public. It was a new and strange feeling for all of us, on and off the stage, but one moment in particular left a lasting impression on me.

As I and other staff members sat backstage listening to the orchestra record an impassioned rendition of the second movement, the Marcia funebre, our phones began to light up with breaking news: Ruth Bader Ginsburg had succumbed to cancer.

There we were, less than six weeks away from a highly contentious national election, gripped in the midst of a pandemic with no end in sight, torn from any sense of “normal,” and with an ever-growing sense of uncertainty and even dread. And there we were, unwittingly performing a Funeral March from the Heroic symphony for this iconic Champion of Hope. It took time for me to appreciate the full emotional impact of that confluence of events, but it was this feeling that inspired Dissent.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg (RBG) was only the second woman on the U.S. Supreme Court in our nation’s history, serving from 1993-2020, and was well noted for her ardent dissenting opinions. A staunch advocate for Equal Rights, RBG fought tirelessly for fair treatment, regardless of gender, race, or income level. Though part of the court’s liberal wing, she enjoyed a close friendship with conservative Justice Antonin Scalia, with whom she shared a passion for opera.

It is likely this side of RBG that made her passing so much more poignant to me. In any other year, she just might have been sitting in the audience enjoying our concert. In fact – had music been her calling instead of law – she just might have attended Converse College, playing in the orchestra under the direction of Henry Janiec. As a young woman, RBG played the cello and the piano, and her passion for the arts never waned. Later in life, she even had honorary walk-on roles and speaking parts in productions by the Washington National Opera.

In writing Dissent, I returned again and again to Beethoven’s Marcia funebre. Although Dissent is does not directly quote Beethoven’s work, I drew inspiration from several important elements. For example, in his piece, whenever a melody moves upward, some aspect of the harmony moves downward. Whenever a melody moves downward, the harmony moves upward. This kind of counterpoint is not unique to Beethoven by any means, but the extent and effectiveness of his contrapuntal writing in this particular movement is breathtakingly brilliant. Furthermore, the sheer prevalence of contrasting motion makes the few moments of unity that much more emotionally striking.

As a final note, I also took a little, tongue-in-cheek inspiration from the legal scholar Cass Sunstein’s description of RBG as a “rational minimalist,” who sought to always build on precedent.

Peter B. Kay

Composer

Dissent

Dedicated to Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Peter B. Kay

(1980-)

Ginsburg reportedly took a liking to her nickname “Notorious RBG,” which she received after her dissent in a landmark case in 2013. If you don’t know, the moniker was based on the stage name of the 90s rapper Christopher George Latore Wallace, who was known as “The Notorious B.I.G.” Both Ginsburg and Wallace were vocal opponents of oppressive systems, talented and witty writers, and Brooklyn natives. Now you know!

Q. What is your greatest accomplishment of which you are the most proud?

A. I’m proud that I’ve been able to develop my music business, my way. Soon,

I’ll be releasing my first solo album.

A. Busking on the streets of Asheville, NC. It was a great contrast to the usual concert stage in which there is already an audience that expects to hear music. While busking, I had to attract my own audience and then keep them interested.

Concerto for Organ Francis Poulenc

(1899-1963)

The lot of the music critic can be an unhappy one. The critic is called upon, usually on an absurdly short deadline, to pass judgement on composers and pieces with which he sometimes has had little opportunity to become intimately familiar, and on performances which, by their nature, are fleeting and transitory. While composers and conductors take good reviews for granted, the dangerously unstable nature of these artists frequently causes them to react to poor notices with irrational hostility, and the critic lives in fear of the vicious threats he all too often receives. And history is no kinder: generations after his death, a critic may be held up to ridicule for any article of his that fails to coincide with present opinion, as those critics unfortunate enough to have dismissed Beethoven’s Fifth and Ninth Symphonies after their premieres could readily testify. Too frequently all this responsibility weighs heavily on the shoulders of the critic, and his life becomes a tortured Gehenna of drink, debauchery, and debasement.

The story of the Parisian critic Henri Collet is a happier one, though, for Collet brought people together. Specifically, Collet brought together six French composers who have remained linked in textbooks ever since as Les Six. In a 1920 article depicted six young composers who at that time had relatively little in common as being a closely-linked, like-minded group of friends bent on reforming French music. The six composers in question (Poulenc, Milhaud, Tailleferre, Auric, Honegger, and Durey), while understandably surprised, grew curious about one another, and before long became close friends. They spent nearly every Saturday evening for over two years together, eating, drinking, and haunting Paris’ fairs and music halls.

Those Saturday evenings had a great impact on the music of Francis Poulenc, for Poulenc developed an affection for jazz and popular music that remained throughout his life. Claude Rostand wrote that “there is in Poulenc a bit of monk and a bit of hooligan,” and it was the hooligan side of his musical personality he developed on those evenings. The monk side came a little bit later, when – shocked by the tragically early death in 1936 of his friend, the brilliant young composer Pierre-Octave Ferroud – he made a pilgrimage to the Catholic shrine of Rocmandur and recommitted himself to that faith.

Monk and hooligan take turns on the stage in the seven alternating sections of Poulenc’s single-movement Organ Concerto. Written for the influential patron of the arts and leader on the Parisian social scene the Princesse Edmond de Polignac (or, as she had been known before she moved to France and married a nobleman, Winnaretta Singer, heir to the Singer sewing machine fortune), the piece was first performed at the Princesse’s salon in 1938. It begins and ends on a slow, somber, note, but its inner five sections are in turn playful and tender.

Chris Vaneman

Contributing Author

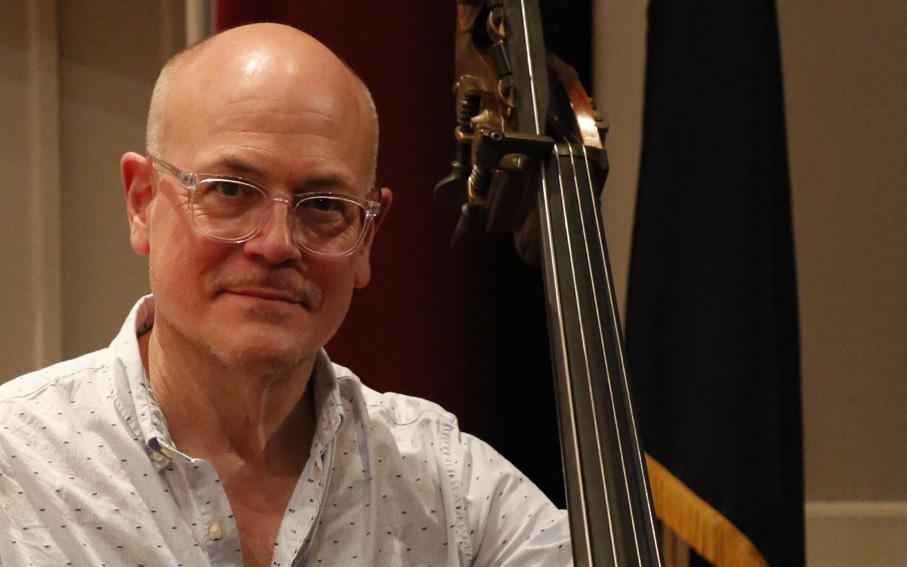

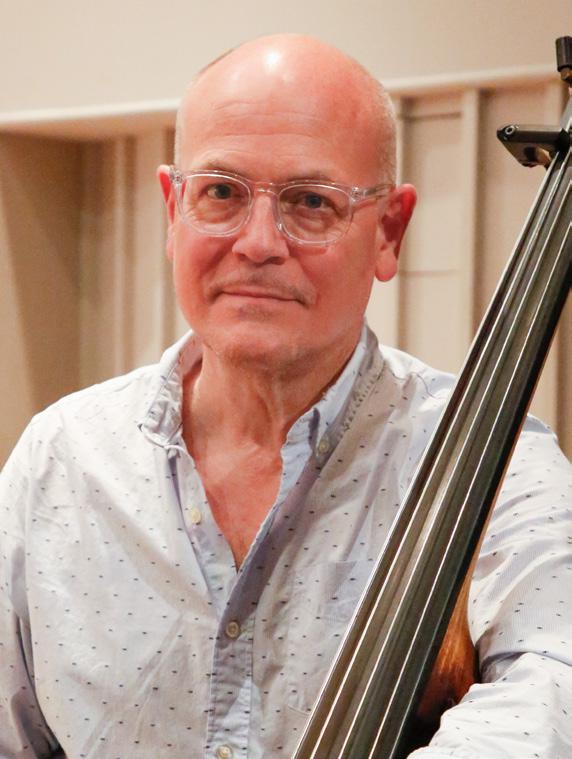

Ian Bracchitta

Princpal Bass

A. Try not to be overly critical, and avoid people who insinuate what you can’t accomplish. But above all remember the “P”s: practice, patience and perseverance.

Callie Brennan, Concertmaster, hails from the sunny state of Maine, which is where she first held a violin at the tender age of four. As an adolescent she studied with Ronald Lantz of the Portland String Quartet, and received regular coachings in chamber music from the PSQ.

While pursuing her Bachelor’s degree at The University of Colorado, Callie studied with Lina Bahn and Harumi Rhodes. During this time she studied abroad in Sydney, Australia, studying with Ole Bohn at the Sydney Conservatorium. This travel prompted her to look abroad for postgraduate study, and led her to The Guildhall School of Music and Drama. In 2016 she moved to London, England, where she completed two Masters Degrees in Music and Violin performance. During her studies at Guildhall, Callie studied with Stephanie Gonley and Ofer Falk, and had numerous opportunities to receive coachings from other internationally renowned musicians. She performed twice under the baton of Sir Simon Rattle, playing alongside the London Symphony Orchestra

Moving to Asheville, NC, in 2018, Callie enjoyed regular performance opportunities with the Asheville Symphony Orchestra, Brevard Philharmonic, and Spartanburg Philharmonic. She now lives in Denver, CO, and is currently principal second violin of the West Virginia Symphony, principal first violin of the Fort Collins Symphony, and has the pleasure of serving as interim concertmaster for your Spartanburg Philharmonic.

Korean violinist Haelee Joo, Principal Violin II, began her musical education in Germany. She was accepted by Prof. Ingeborg Scheerer at Hochschule für Musik Köln at the age of 16 and graduated with honours from the jury.

After she finished her studies in Germany, she moved to Vancouver to study with Prof. Robert Rozek, a pupil of the greatest violinist of the 20th Century, Nathan Milstein. She continued to study the violin with Prof. Régis Pasquier at École Normale de musique de Paris in France where she earned the Diplôme d’Exécution and Diplôme d’Enseignement. She recently graduated from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, pursuing Master of Music performance under the guidance of Dr. Fabián López.

Haelee gave performances as a soloist with the University Orchestra of Hochschule für Musik Köln standort Wuppertal, also at the Bergische Musikbiennale in Wuppertal, Germany. She was invited to the Duo Recital with a pianist Eri Uchino in Tokyo, Japan.

Haelee is also interested in Orchestra playing. She was accepted as a member of Junge Deutsche Philharmonie at the age of 17 where she toured the renowned halls in Europe such as Berliner Philharmonie, Lucerne Festival Hall, Kölner Philharmonie, Alte Oper Frankfurt, and Tonhalle in Zürich. In 2010, she toured as concertmaster, and recorded violin solos of Transfigured Night by Schönberg in Frankfurt Alte Oper.

A. Keeping my lawn looking good without dumping tons of water on it. Go ‘Emerald’ Zoysia grass!

Q. What is the most spontaneous thing you’ve ever done?

A. As a teen, I hitchhiked to Rochester, NY from near NYC to see the Grateful Dead after someone gave me a free ticket. I don’t remember much after that.

Brianna Tam, Principal Cello, originally from Connecticut, is a professional classical and electric cellist, as well as an active composer. Brianna started her classical career at eight-years old, and then continued her studies through high school, partaking in the New York Youth Symphony, Asya Meshberg’s Chamber Music Institute, and Brevard Music Festival.

Brianna furthered her schooling at Oberlin Conservatory, pursuing a Bachelors in Music Performance. However, she withdrew from the program during her second year and moved to Greensboro, North Carolina. Brianna then enrolled part-time at the University of North Carolina-Greensboro. The extra time allowed Brianna to explore professional opportunities in cello performance. Brianna became Assistant Principal of the Fayetteville Symphony, Principal Cellist of the Spartanburg Philharmonic, and joined Deans’ Duets, LLC as a trusted freelance cellist.

Throughout her music career, Brianna has held a great curiosity for many genres of music besides classical. Two years ago, she purchased a loop pedal and electric cello, drawn to their creative potentials by allowing her to independently create a full ensemble. This propelled her into areas of her career prior unknown. Currently, she is not only a classical cellist, but also an electric cellist, composer, arranger, and session musician. She has written a full album of originals (release date - TBD), has worked with local bands as both a full time member and as a session musician, and has been collaborating as a session musician online with composers and songwriters worldwide.

Alvoy Bryan Jr., Principal Viola, holds a B.M. in music performance from Indiana University (Bloomington, IN), a M.M. in music performance from University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and a D.M.A. in music performance from the University of South Carolina. He is a native of Decatur, G.A. and began studying the violin at the age of ten, and the viola at the age of eighteen. Some of his principal teachers have been Ronda Respess (Joseph Gingold student), Mimi Zweig, Dr. Scott Rawls, Frits De Jonge, and Ryan Kho (Dorothy Delay student).

Alvoy is a member of Spartanburg Philharmonic, Greenville Symphony Orchestra, Augusta Symphony, Aiken Symphony (Principal Viola), and has performed with orchestras such as South Carolina Philharmonic Orchestra, Charleston Symphony, Greensboro Symphony, Long Bay Symphony, Danville Symphony, and Charlotte Philharmonic Orchestra. Alvoy has also performed chamber music in Europe and South America with a few professional chamber music groups. He served as the violist in the Atlantis String Quartet, and he was the founding member of the Gervais String Quartet and the Bryan Chamber Ensemble.

Alvoy has maintained a private violin/viola studio for over fifteen years. He has also taught master classes for high school string students throughout the Southeast. Alvoy has served on the faculty at Allen University, Benedict College, Presbyterian College, South Carolina State University, Claflin University, and Webster University. Currently, Alvoy is the Orchestra Director at Cardinal Newman School in Columbia, SC. Dr. Bryan also serves as the CEO and Co-owner of Bryan Music Group L.L.C.

Q. What is your absolutely favorite piece to play, classical or otherwise?

Q. What is your most bizarre talent or skill?

A. Denis Bedard’s Festive Toccata. It’s the happiest piece of music on the planet!

Ian Bracchitta, Principal Double Bass, is a versatile double bassist equally at home in the classical, jazz and popular idioms. Ian is Principal Bassist of the Spartanburg Philharmonic, Assistant Principal Bassist of the Greenville Symphony and is a freelance bassist with the Charlotte and Charleston Symphony Orchestras.

As a jazz bassist he performs extensively in the area and has appeared with The Tommy Dorsey, Nelson Riddle and Cab Calloway Orchestras, Kate McGarry, Kevin Mahogany, Freddie Bryant and Dianne Schuur among many others.

Ian can be heard on his recent cd, Reflections. Additionally, he has performed with the orchestras for the national tours of countless Broadway shows such as Phantom of the Opera, Wicked, Beautiful, West Side Story, Porgy and Bess, Evita and My Fair Lady and has been heard on regional commercials and industrial soundtracks.

A dedicated teacher, Ian teaches at the South Carolina Governor’s School for the Arts and Humanities, Furman and Clemson Universities and has taught at the University of South Carolina’s School of Music and UNC-Asheville.

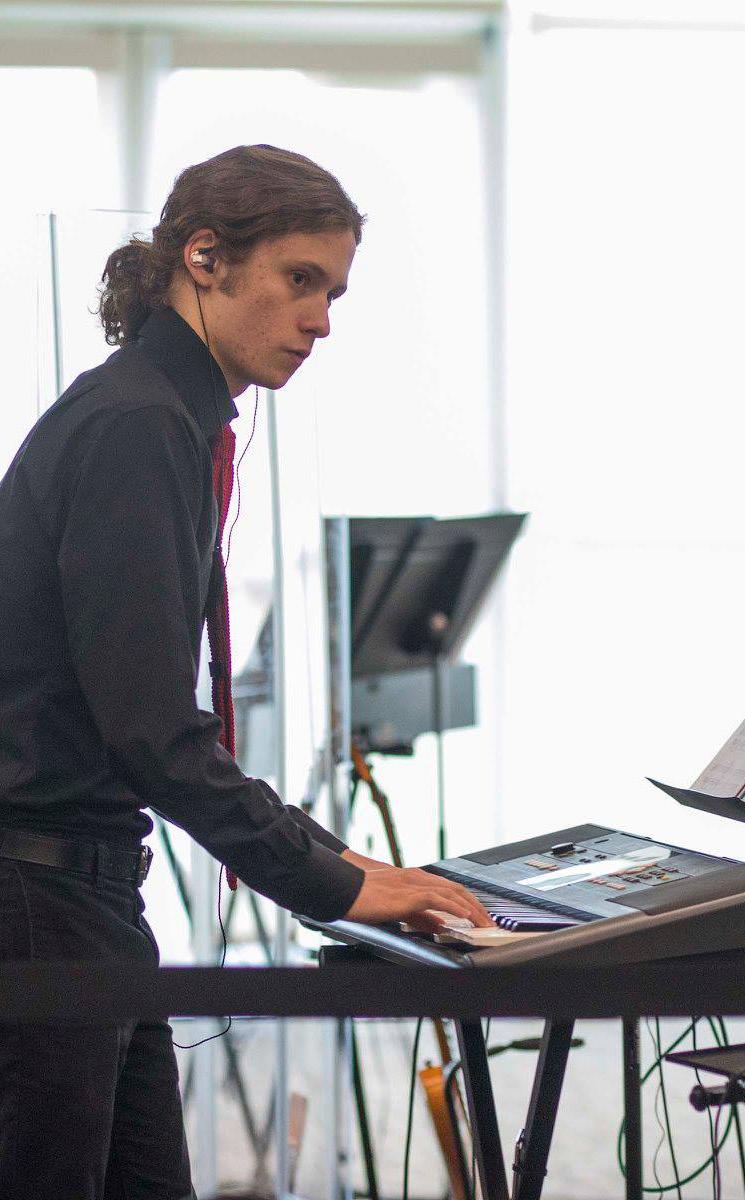

A native of Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada, Brennan Szafron, Principal Organ, is the first full-time organist and choirmaster of the Episcopal Church of the Advent in Spartanburg, SC, a position he has held since August 2003. At this church, he is responsible for playing the organ for all services, directing two adult and three children’s choirs, and directing and arranging music for the instrumental and hand chime ensembles.

Brennan’s earliest training as an organist began in Ottawa, Ontario in 1990, when he took his first year of lessons with Danielle Dubé at St. Peter’s Lutheran Church. He finished high school in Regina where between 1991 and 1994 his teachers were Verleen Baerg, Gordon Wallis, and Harold Gallagher. While in Regina, he took on his first professional positions which were as organists of St. Peter’s Anglican Church and Christ Lutheran Church. He has had continued church employment since then.

Before coming to Spartanburg, Brennan was the assistant organist and choirmaster of Christ Episcopal Church, Grosse Pointe, MI, with whom he toured France and Switzerland in the summer of 2003. He was also a student at the University of Michigan, where he received a Doctor of Musical Arts degree in organ performance, studying with Robert Glasgow. Other degrees include a Master of Music degree from Yale University, where his teachers were Thomas Murray and Martin Jean, and a Bachelor of Music degree, with distinction, from the University of Alberta, where his teachers were Jacobus Kloppers and Marnie Giesbrecht.

A. Memorizing more hymn numbers than any other Episcopal church musician.

A. The great outdoors. I just can’t spend enough time hiking.

A. Never be afraid to fail. There is no success without failure.