SPEC

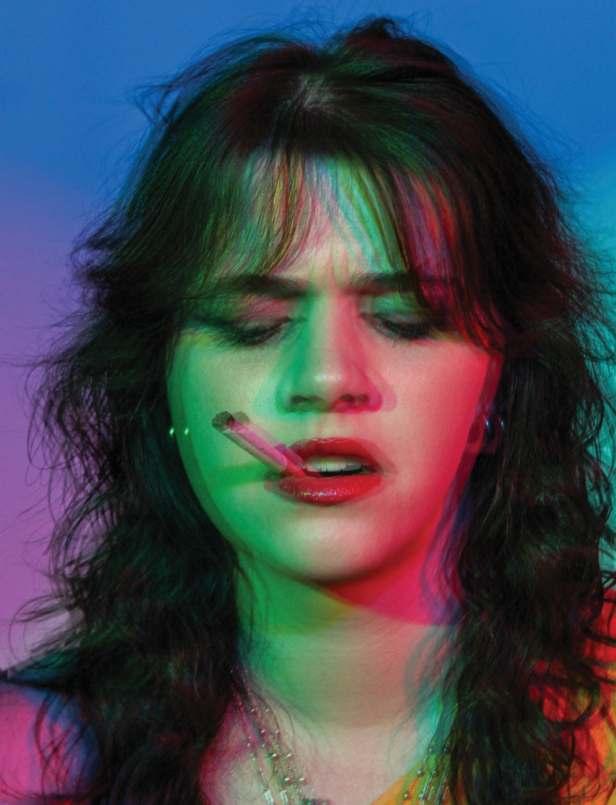

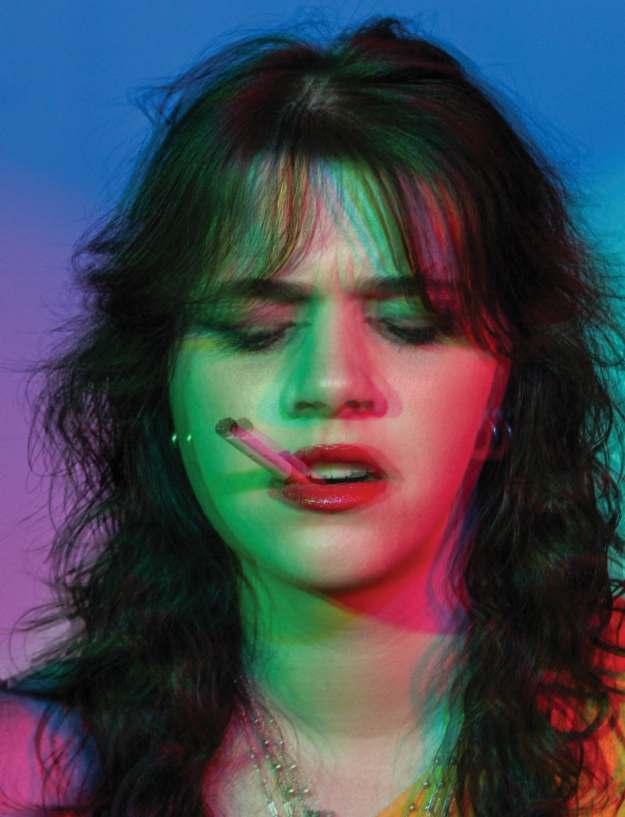

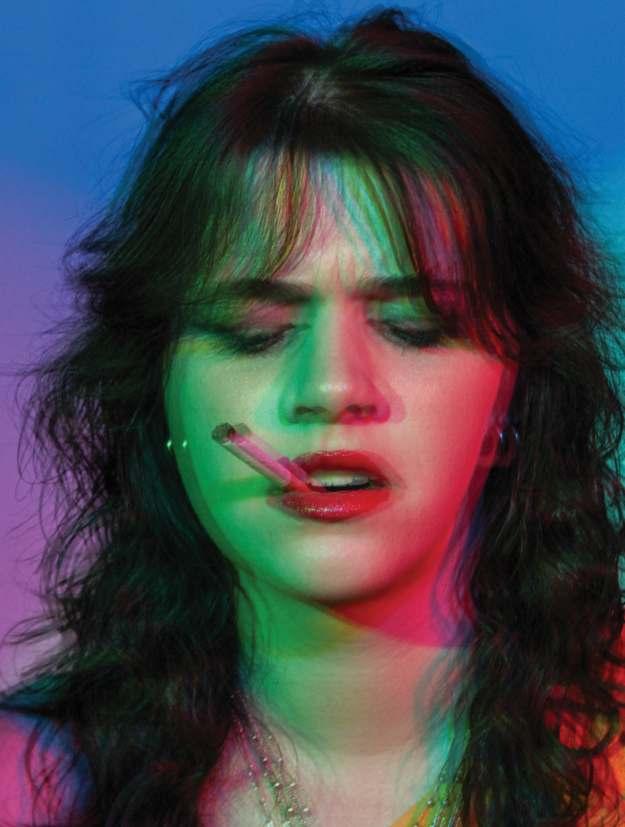

Addiction is Trendy.

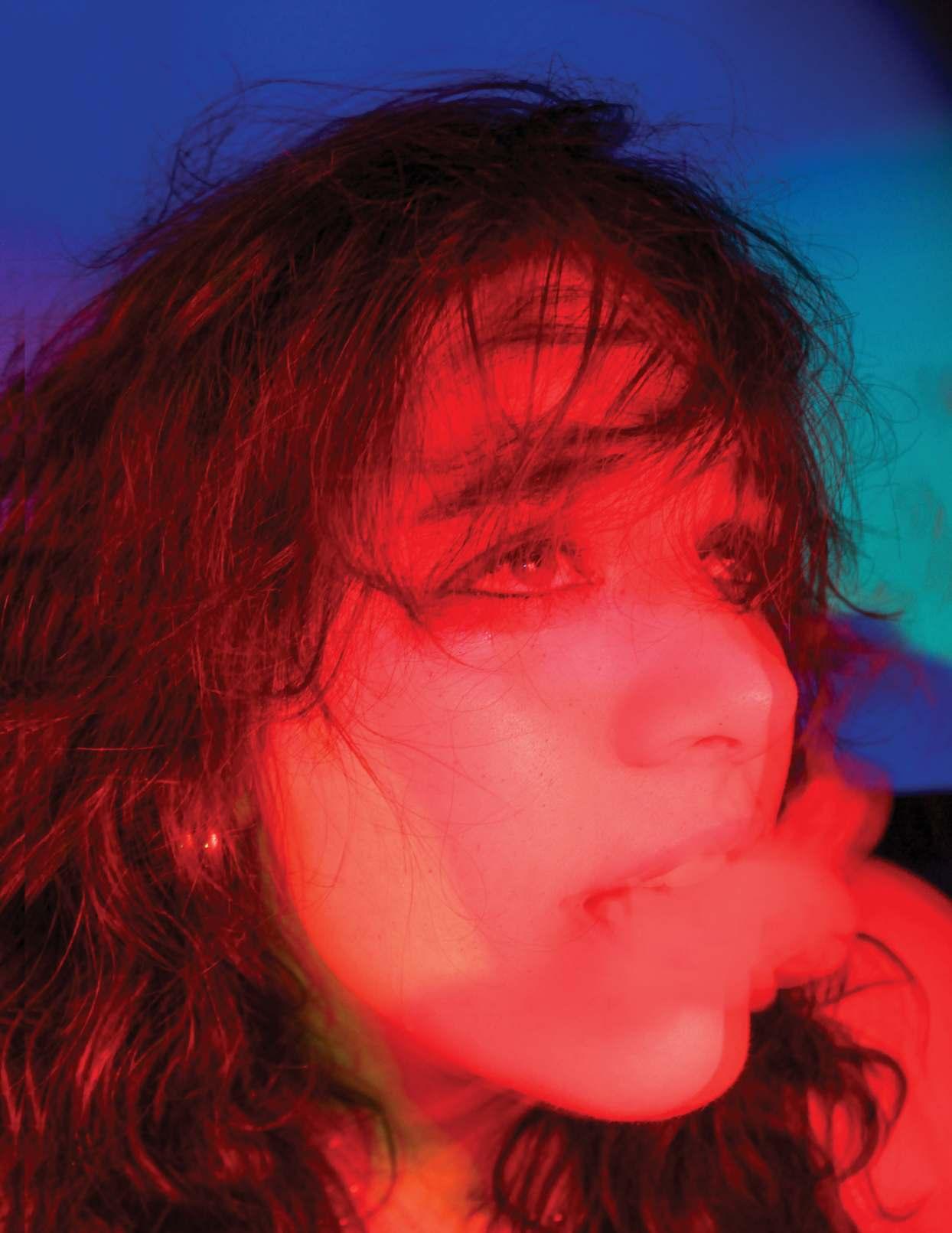

I am nine years old and alone, sitting cross-legged at an airport terminal, waiting to board my transiting flight. My parents aren’t far; only ten feet away, but separated by the glass doors of an airport smoking lounge. I watch them from afar, like fish in a smoke-filled aquarium. I squint through the haze, trying to make out the faces of the strangers unified by their shared addiction. My parents are among them, laughing and leaning in. But they don’t look cool. There is no effortless elegance, no Hollywood mystique—just yellow stained fingertips and deep, wrinkled frowns. To me, their habit wasn’t rebellious or alluring; it was routine, obligatory, and desperate. I swore myself against it. To sit in an airport smoking lounge is nothing but glamorous—it’s addiction in its purest form.

WRITING

Jacky Rutherfurd

DESIGN

Kate D’Amaro

PHOTOGRAPHY

Emma Lloyd

PR

Anisa Diamond

Addiction manifests in many different ways, whether it’s alcohol, weed, gambling, or sex. It drives us to the furthest of ends, allowing us to rationalize things once unimaginable. How far would you go to chase that next high? Would you steal to feed a craving? Lie to protect a habit? Risk your health for a fleeting moment of relief? I myself am guilty of addiction. I was once revolted by the smell of burnt tobacco that clung to my parents’ clothes. Now, I indulge in the very thing I once condemned.

Not every relationship with smoking looks the same. In France, a cigarette is as much of an embellishment to an outfit as a designer handbag or a pair of sunglasses. In Indonesia, cigarettes offer an affordable symbol of hospitality and masculinity. In our city of Los Angeles, smoking thrives in contradiction; it coexists in a climate that worships green juice cleanses and exclusive workout classes. SThey rationalize smoking is rationalized as an occasional indulgence rather than a habit. Regardless of where you are, the true virality of addiction lies in the illusion of control: the belief that one can participate without consequence, that lung cancer happens to other people and not themselves. As we partake in smoking against the backdrop of social rituals, we blur the line between an occasional indulgence and a full fledged dependency.

In 1964, the United States Surgeon General published a report linking cigarette smoking to the incidence of lung cancer. The recognition of its ill-effects left Americans with no choice but to change their habits. It first began with a ban on indoor smoking, which quickly expanded as a shift away from the social acceptability of smoking as a whole. Somewhere along the way, smoking has made its way back into the cultural zeitgeist of Gen Z—not as a vice, but as an aesthetic. The media idolizes public figures like Lily-Rose Depp and Lana Del Rey who are often photographed in chic outfits accessorized by a cigarette, . to curate the perfect cool-girl facade. In films like Call Me by Your Name and Saltburn, cigarettes are more than just props, they set the mood for romance and seduction. Exposure leads to acceptance and as smoking reemerges as a trend among Hollywood stars, our generation becomes more and more willing to disregard science.

So why have we begun to renormalize smoking despite “knowing better”? For our generation, this ‘trend’ is not exactly about the chemical relief of a nicotine buzz.

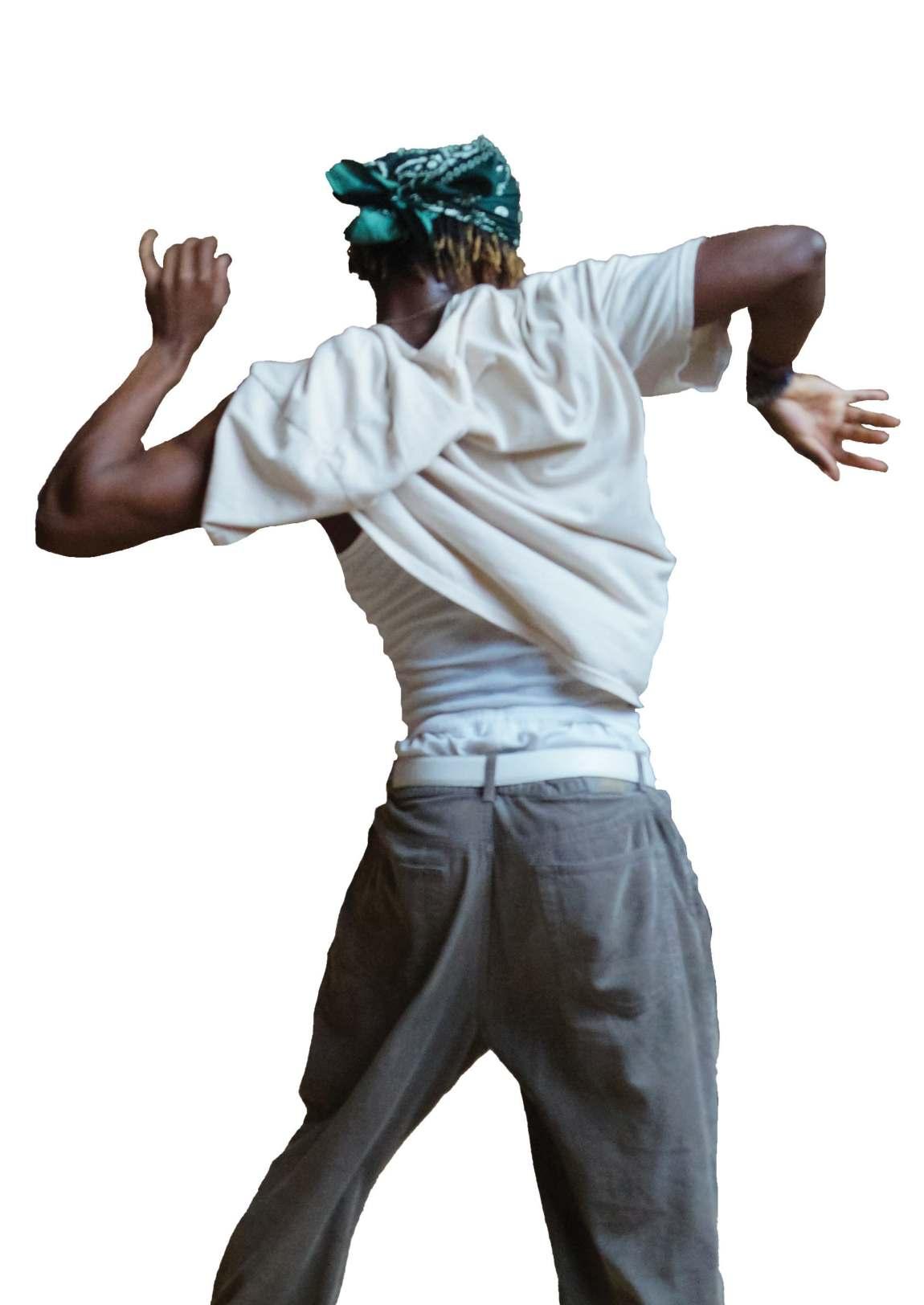

The complex social implications of smoking are just as much to blame. It’saboutthesexyallureofholdingaflickeringflametoyourfacebefore unleashing a slurry of cancer and sex. It’s about the instant comradery formed between two strangers who share a lighter outside the bar. It’s about the desire to project indifference to the world, despite the knowledge that you are hurting yourself—an active rebellion against science and society.

My peers of non-smokers exist as proof that resistance against addiction is possible. They see the cigarette not as a symbol of rebellion, but as what it truly is: an expensive, carcinogenic crutch. In a culture that romanticizes self-destruction, addiction is often downplayed as something casual or controlled. The first step in Alcoholics Anonymous meetings is to stand up among your group members and introduce yourself point-blank: “Hi, my name is Jacky and I’m an addict.” To be reduced to your addiction is supposed to be the ultimate form of shame, but what shame are we left with when we live in a generation that reframes addiction as humorous and quirky. Habits that should be plainly recognized as “addiction” are now usually prefaced with a list of contingencies:

“I only drink to loosen up.”

“I only do coke at parties.”

“I only smoke when I’m around my friends.”

Whether you’re California sober or an occasional dabbler, our generation refuses to acknowledge the underpinnings of what we choose to romanticize. Somewhere along the years, I’ve found myself in a place I’d never imagined. When I’m at a house party and am offered a cigarette, I nod in agreement. With slacked wrists and a cigarette in hand, I carry on with the night: dancing, laughing, and getting lost in conversation. It is only until I am hit with a wave of nostalgia that I am able to actively make sense of the position I am in. My hair reeks of ash and my voice is beyond hoarse. I’m in a hot box of smoke plumes, no different from an airport smoking lounge. What can I say, I’m a sucker for fashion, and smoking is officially back in vogue.

SOIL SHIFTS

APPROPRIATION & GENTRFICATION

Have I been living in a paradox this entire time? Southeast Asia was all I had ever known; the “I heart NYC” crop tops worn by locals, familiar smells of fusion restaurants and radio infiltrated by western pop. But was my reality an authentic reflection of what it meant to be Asian?

Living in Bali, Indonesia, I learned to embrace tourism, accepting it as an homage to traditional Balinese culture. In Singapore I learned that I could still find some of the best western flavors despite living on an island only 280 square miles wide. In Malaysia the opening of a new jumbo mall every month was no shock to the community — pushing out poorer communities and increasing the cost of living was normalized.

Any and all cultural landscapes are made up of a garden of flowers slowly being plucked away by gentrification’s global dominance. The deep-rooted traditions of a melting pot of cultures — those of which are slowly withering right in front of our eyes. It is undeniable that America is profoundly impacted by this brutal process — one that is, in many ways, deeply dehumanizing our community.

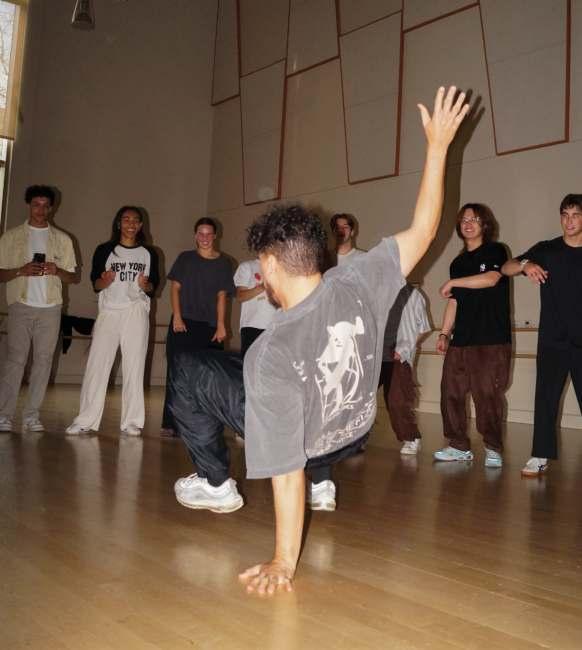

Now, coming to California, I have witnessed this process continue most overtly in pop culture bedrock of Los Angeles: hip-hop. Distilling cultural awareness directly into the listeners earbuds; utilizing turntablism, repurposing elements from past artists and incorporating drum machines (i.e. Roland TR-808), artists help this garden regrow its roots — reclaiming self-identity in the process. Though this is only below the surface of the soil. Each sound nurtures the growth of lyricism, providing the flower with distinct nutrients transported through the phloem of what is — hip-hop music.

The ultimate voice for those in Black and underrepresented communities is Kendrick Lamar. He is among the many who remind us of the tumultuous journey Black Americans have experienced as a result of marginalization and oppression. This reminds us that our personal gardens are so vulnerable to pruning — our roots distorted beyond the control of our own gardening tools. The epitome of reclaiming what was once ours.

Lamar’s album “To Pimp a Butterfly” (2015), explores how a butterfly derives from a caterpillar — inherently less refined, grounded in the struggle of transformation. The caterpillar is always finding a way to reap the benefits of the butterfly and thus “pimping” it out. The butterfly is weak, or so it seems, in the lens of the caterpillar. This is a comment on Black American culture, being constantly terminated and challenged by the gentrification of America.

The butterfly complex is what it is: once a caterpillar is exploited by the industry then it can spread its wings and be the butterfly it always wanted to be — but at what cost? At the cost of neighborhoods being stripped away from its roots, at the cost of erasing history, and the cost of what it means to be human.

Similarly, big-name rappers such as J.Cole and SZA are in the pursuit of bringing light to these withering stems through their music.

The effects of this drought go beyond the words of famous rappers and is a reality for many. For the first time in nearly 40 years, D.C. has experienced the highest degree of gentrification of Black communities, characterized by the cultural shift taking place in the DMV. What was once a place open to all walks of life is now an environment made to make you feel like an alien species.

KeLow LaTesha, musical artist who grew up in the DMV, mentions that “What comes before helps birth what comes next in a sense,” in an interview with Respect. The seeds we plant affect the blossoming of future generations, but in D.C., musical influences such as Go-Go and Neo-Soul no longer have the same standing they once did before. One thing that Latesha’s experience does tell us though, is that growing amongst minorities has a profound impact on the way in which we view the potential within ourselves. Struggle is part of the human experience — the mere chance to realize that adversity provides the fertile ground needed to grow branches beyond conventional thought.

“Adversity provides the fertile ground needed to grow branches beyond conventional thought”

LaTesha is the very rose in a garden of thorns that made it out alive. Despite external pressures in the DMV attempting to drive her community out, her cultural armor (that being her eclectic array of muses), remains in her system. A subtle form of protest against what is happening around us lies in our ability to remain as who we are — as people, daughters, sons, and members of society.

On a visit to Puerto Rico this Spring, I couldn’t help but hear hip-hop artist Bad Bunny’s lyrics in my ear. He, Benito Martinez, has gathered his own bouquet of commentary on gentrification within Puerto Rico.

The release of his short film titled “DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS,” translated to “I should have taken more photos,” to accompany his album with the same name (2025) was pivotal in bringing back color to Puerto Rico’s landscape — an homage to his hometown. Martinez explores how a coquí, a frog native to Puerto Rico’s environment, is a reminder of those instrumental pieces that help foster the growth and maintenance of the garden he, and many others, call home. That garden that is Puerto Rico; a tropical island that requires those moving pieces to help preserve the past.

For decades, the fashion industry operated under an unspoken rule: Black designers, creatives, and voices were pushed to the fringes. Virgil Abloh changed this rule. As the first Black man to lead Louis Vuitton menswear, he proved that luxury fashion could belong to those who had been excluded. Abloh was never interested in fitting the mold; with degrees in civil engineering and architecture, he saw himself as a “maker, not a designer.” His work blurred the lines between art and culture—whether it was the embroidered “TILL DEATH DO US PART” in Hailey Bieber’s wedding veil, his role as creative director for Kanye West, or the founding of his own label, Off-White. Abloh didn’t just leave a legacy; he left a mindset: wear what you want, create what you want, and exist how you want.

Virgil Abloh redefined the possibilities for Black designers in high fashion, showing that cultural influence was just as important as traditional aspects of fashion design. His success created space for other Black creatives to challenge industry norms. One key visionary to emerge was Kerby Jean-Raymond, the founder of Pyer Moss. Jean-Raymond took a different approach, using fashion as a medium for activism and storytelling. His collections have addressed racial injustice, celebrated Black innovation, and challenged the fashion industry’s failure to acknowledge Black designers. Though his presence in the fashion world has diminished in recent years, his impact is still felt and continues to inspire, and today, a new generation of creatives has emerged.

Wisdom Kaye, a Gen-Z fashion content creator and model, turned what once made him a target into his greatest asset—his appearance. After facing bullying for his looks and struggling with body image, he found confidence through fashion, using it as a form of self-expression. His rise on social media shows how individuality is now more valued than exclusivity.

After Abloh passed away in November 2021, Louis Vuitton’s search for a successor was not just about filling his role — it was about preserving the legacy he had built. When they appointed Pharrell Williams, it signaled a shift in the industry, and his influence on Black men’s fashion is undeniable. His appointment wasn’t just a business move; it was a statement that fashion is changing.

Much like Abloh, Pharrell has pushed hip-hop culture, sneakers, and streetwear into the luxury space. However, Pharrell’s impact extends beyond just this—he brings a new vision to Louis Vuitton. A vision that can be seen in his Winter 2025 menswear collection, created with Nigo. This collection is a statement—a modern reinterpretation of dandyism featuring suits, workwear, and bomber jackets. By acknowledging the origins of dandyism and incorporating traditional elements like suits, Pharrell reshapes them through the lens of modern fashion. His vision recognizes that today’s Black culture, particularly in hip-hop and streetwear, has a redefined version of dandyism—one that is just as sophisticated and just as influential.

“Hip-hop wasn’t something I found—it was just life,” he explains. “It was always there. The way people walked, the way they spoke, the way they dressed—it was Black culture, which meant it was

tling the speakers of his father’s car, in the way people in his childhood neighborhood carried themselves, and in the unspoken languageunspokencoded language of rhythm and movement and rhythm

That inheritance guided him from his earliest days in battle circles

proved that hip-hop could stretch beyond the streets and into the world, that it could be both deeply personal and universally understood.

Hip-hop has always had to fight for space—on stages, in academia, in art. ; Bbut for all the battles Rose had fought for hip hop—on the dance floor and in the industry—none compared to the one he never saw coming.

A life-threatening brain tumor forced him to confront something far greater than competition or career ambitions. The thought of brain surgery had always unsettled him—the idea that someone could open his skull and reach into the very place that housed his artistry and change his thoughts or sense of self was his greatest fear. “I was okay with a broken bone,” he admits, “but the thought of someone going into my brain, touching something and changing who I was? That scared me.”

The uncertainty was suffocating. So much of who he was lived in his body–, in his ability to move, to translate rhythm into motion. He had spent years refining that instinct. Iif the surgery altered even the smallest part of itthat, what would be left?

“I was terrified. It wasn’t even just about survival—it was about who I’d be if I survived. What if I woke up and something fundamental was different? What if I lost something in that operating room, something I couldn’t get back?”

When the time came, on the operating table and under the sterile lights, he was confronted with a stillness he had never known. The future, always something he had envisioned in motion, now hung in uncertainty. He was paralyzed by the idea that he might close his eyes and wake up different— or even not wake up at all.

But that fear had only one escape: through it.

The only way out of that fear, he realized, was through. When he woke up from his surgery, something inside him had crystallized. “If I had died in that surgery, would I have been satisfied with what I left behind? The answer was no.”

It was not just relief he felt—it was clarity. “The worst had happened, and I was still here. So what the hell was I afraid of anymore?”

He had spent too long hesitating and second-guessing whether his vision would be received the way he intended. “I realized I had spent too much of my life holding back—not out of fear of failure, but out of fear that I wouldn’t get it exactly right. And that’s no way to live.” The constant waiting for the perfect moment had kept him stagnant for too long, but survival had given him an urgency he couldn’t ignore. “So much of my life felt defined by untaken chances,” he admittedadmiteds. “But after that surgery, I wasn’t going to second-guess anymore.”

That realization became the catalyst for Vinyl & Brush, a production company he founded to amplify underrepresented voices. His mission isn’t just about telling stories, it’s about telling the right stories. “There’s something incredibly powerful about joy in the face of oppression,” he saidys. “That’s hip-hop’s story— it’s resilience, it’s celebration despite everything.” He’s interested in narratives that reflect the complexity of Black life, not just its struggles, but its victories. “I want to see stories that show the allyship between cultures, our differences and our connections. I want to see more of that.”

MASTERING ART of IT ALL

“Sando” is breaking the mold of what constrains and defines an “artist” through his graffiti art and seemingly unlimited artistic passions.

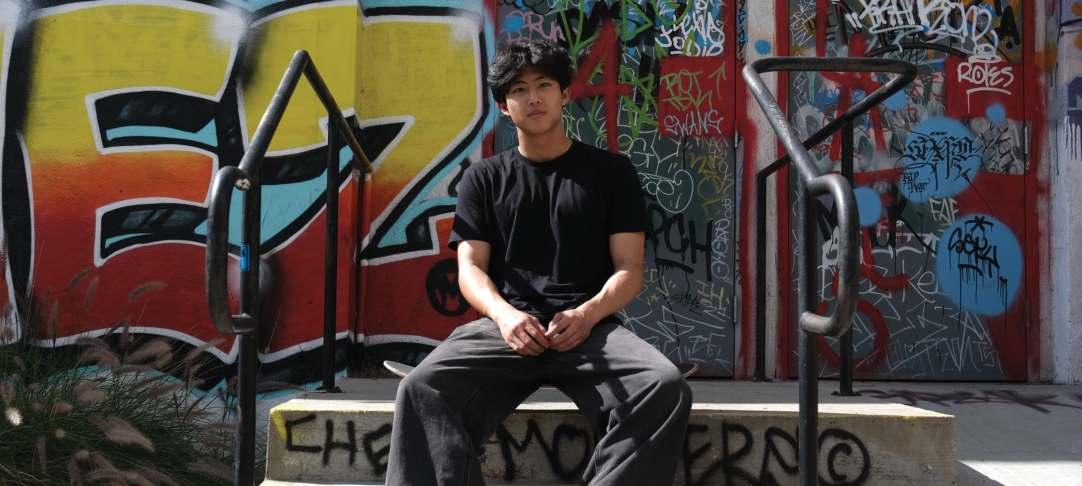

Sando glided over to our interview on his skateboard wearing a bright blue beanie, paired with his matching Honduran football jersey. His hands were decked out in silver rings, and his right wrist was enveloped by layers and layers of beaded bracelets–I later found out that these “Mala beads” were a gift from Sando’s mother–which he fiddled with throughout our interview.

We immediately jumped into discussing Sando’s doodle-covered and worn-in skateboard. When thinking about Sando’s interests, one can’t help but wonder, what doesn’t he do?

The Los Angeles County native–in addition to being a graffiti artist–writes music, plays guitar, cooks, dances, draws, skateboards, and is a professionally represented model and actor. Within the first few minutes of our interview, it was evident that Sando is the antithesis of the cliché: “Jack of all trades, master of none.”

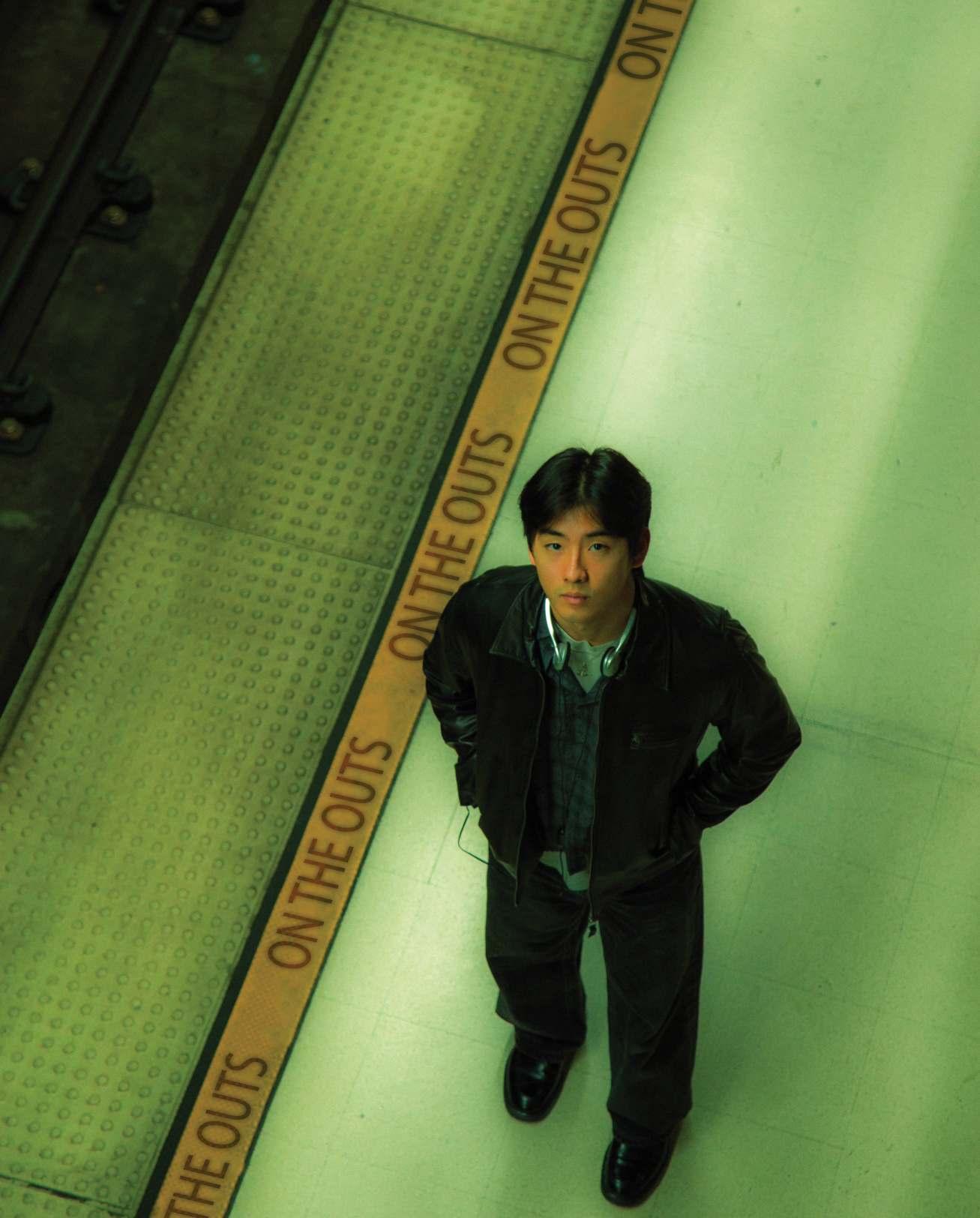

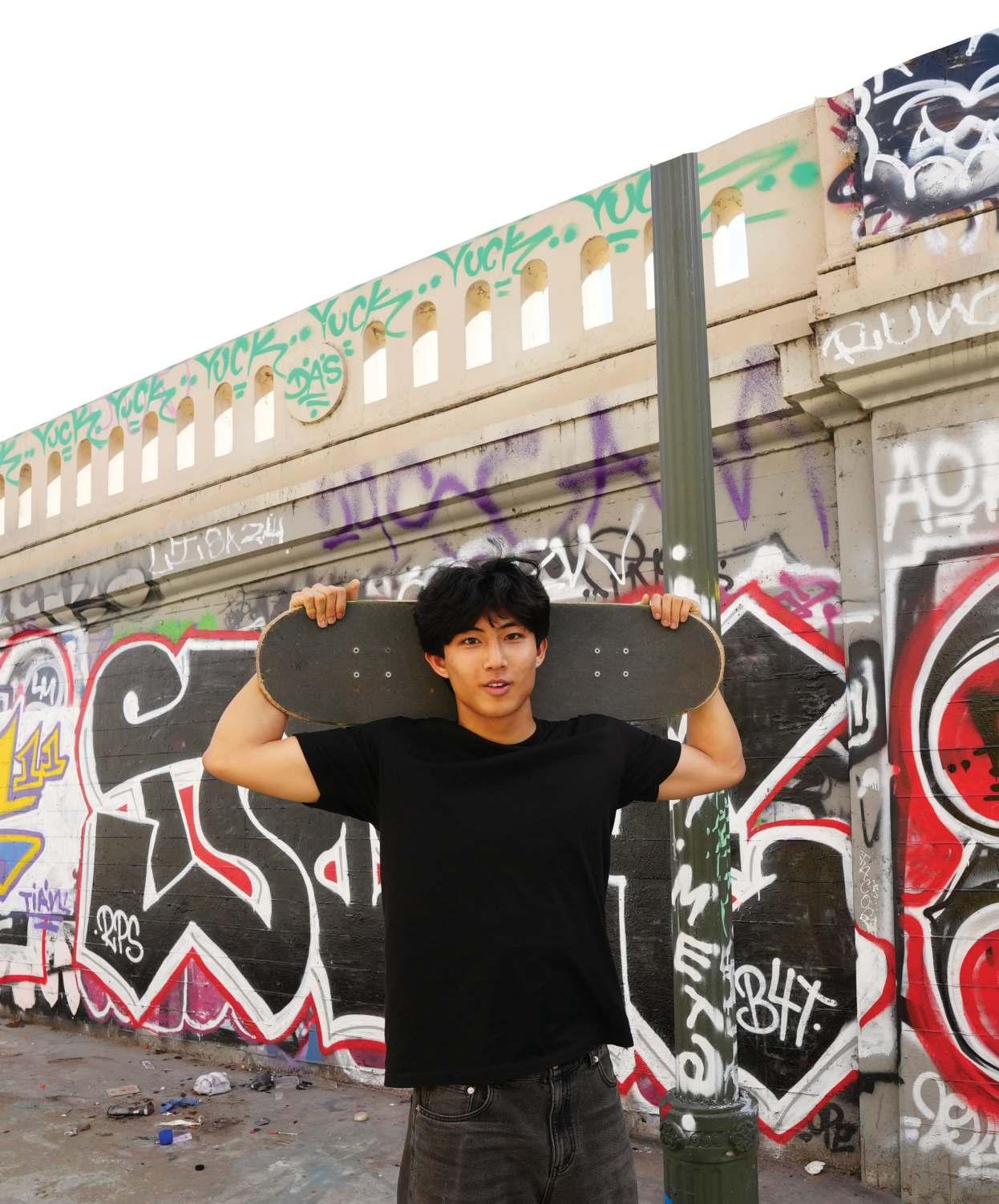

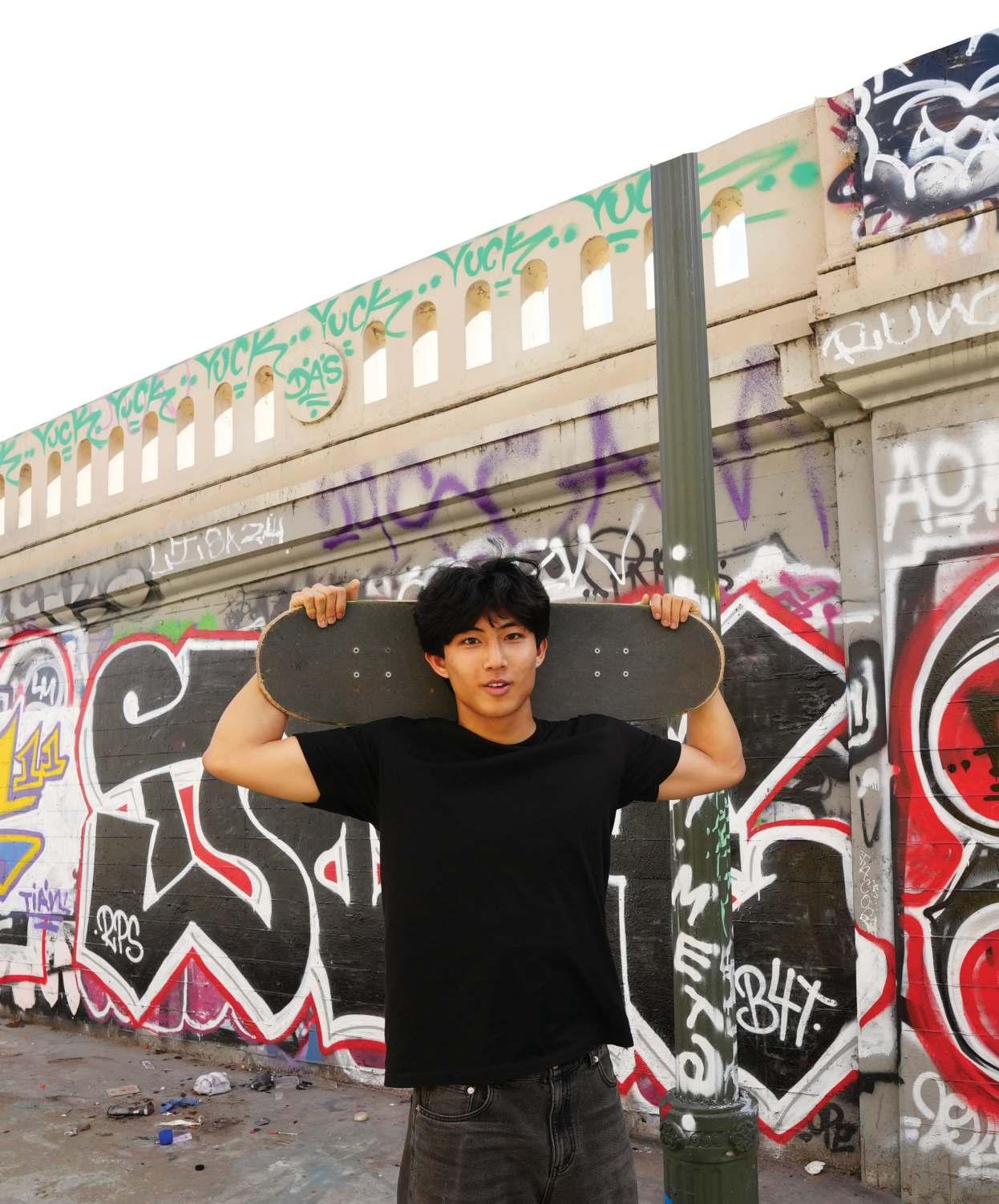

Before I met Zach Lee, I met his skateboard.

On a film set packed with cameras, crew, equipment, and little to no personal belongings, Zach’s battered green skateboard peeked out from underneath a sofa. When I asked whose it was, everyone said unanimously, “Zach, of course.” Hours later, Zach appeared. Immediately, it was evident that he was a skater. From his baggy clothing, the way he stood— both relaxed and alert all at once —and even his language, littered with lingo like “dope” and “okay, word”, everything about Zach screamed skater.

Most people will never step on a skateboard, let alone attempt to learn how to skate. Kickflips require popping the tail of a skateboard, sliding your front foot up the skateboard quickly (an “ollie”), using that front foot to rotate the board 180 degrees, all whilst jumping in midair to then land on the board with two feet. But for Zach? No problem.

While the skate community in Irvine is not as prevalent compared to Los Angeles or New York City, where they not only have an advantage in population (more skaters!) but also in skateparks—35 in LA, over 40 in NYC, and yet only 1 in Irvine—Irvine’s skate community is still thriving.

“You can definitely find people skating at the local skate parks,” Zach said. Zach’s local skate park is Harvard Skate Park, the first skatepark formed in Irvine. Located at the corner of Harvard and Walnut, Harvard Skate Park first opened in the summer of 2000. The park includes a wide arrange of skate elements, most notably, a “spine,” or a double-sided ramp that is made up of two quarter pipes (a standard mini ramp), a “bowl,” an enclosed area of quarter pipes, and even lighting that allows skaters to skate at night.

“That skate park definitely helped me find a group. I remember, growing up, I’d be coming to the skate park and meeting up with the same skaters, and I was getting hyped up by the older skaters.”

It’s an art, and it’s a community: “The longer you skate for, you’re bound to meet other skaters that you vibe with. You can meet [anywhere]. It’s not a set space.” In fact, sometimes, by strokes of luck, skaters meet in the oddest places. “Two [film] sets ago, I met this skateboarder. He was in a street outfit, and I went up to talk to him. We [started] talking about skateboarding, and he turned out to be a skateboarder. We went to the skatepark after and skateboarded, and now, he’s the homie.”

“[Skating] is about friendship,” Zach said. “Sometimes you just gotta go out with your friends and let off some air and skate around with your boys.”

“There’s skateboarders of all ages, races, looks, ethnicities,” Zach said. “That shit doesn’t really matter. Whatever disability you might have, it’s literally all seen in the skate community. People that don’t have limbs skateboard, and they find new ways to skate with their hands. It’s pretty crazy what people can do.” For Zach, skating is not just a sport. It’s a mindset. Practicing tricks hour after hour, day after day may be draining, but, for many, it is also revitalizing.

“I could probably hit it ninety-nine out of a hundred times.” Zach first began skating in Irvine, his hometown. “My brother’s friends came over, and they brought a skateboard. I was watching his friend try to ollie, and I [thought], ‘Oh, that looks fun!’” Ever since then, Zach has been skateboarding, and this year will be his ninth year skating in Irvine.

It was a good skatepark to begin my skateboarding journey,” Zach concluded. However, skateparks are not the only place where people can skate. “I really love to skate street in LA. Street means not in a skate park setting, but just anywhere that isn’t a skate park. In the city, there’s staircases, random spots in the malls. Whatever you find around. There’s just a ‘the city is your skatepark’ kind of vibe. The city or whatever—your environment is your park.”

First popularized in the late 80s, street skating has long been a way for skaters to express themselves outside the confines of a skatepark. There is an originality to it that is hard to find elsewhere. Think about an artist with an unlimited canvas or an architect with an expansive world—that is what street skating is all about.

Focusing on the skate community, Zach mentioned his love for Youtube vlogs and films like mid90s, Skate Kitchen, and North Hollywood that center around the relationships made between skaters. However, while these films present skating positively, there are many other pieces of media that denigrate skate culture. From the film Police Academy 4 where skaters are called “delinquents” to an article by the Washington Post titled “Invasion of Skateboards”, skating has long been disparaged by the general public.

“It’s associated with vandalism & smoking weed. Being a menace to society and breaking stuff. Kids that don’t really focus on school, they just like to skate.”

Despite the many biases around skateboarders, the skate community doesn’t consist solely of delinquents and menaces to society. It’s made up of a melting pot of people.

“It keeps the fire burning. It’s definitely taught me to take a breath, and when shit gets tough, just hop on your board and pop a trick. You start to understand that life ain’t all that tough, and you don’t gotta take it too seriously, because we live on a rock. We’re literally pushing on a piece of wood.”

Skate culture is heavily tied to improving mental health. Not only does it reduce anxiety and boost mood, skaters tend to better communicate and develop relationships with people of diverse backgrounds. Beyond the mind, skating is also a great source of cardio. Working nearly every muscle group in the body, it improves joint and muscle health and refines balance and coordination.

“It just teaches you how to be in control of your body.”

Skating has helped many learn control not only of their bodies but of the way they present themselves. When Zach first started skating, he noted that his “fits were basic—skinny jeans and stuff.” However, he said that, now, his style has evolved, as “skateboarding is heavily tied to thrifting, baggy ass jeans, button ups, and hoodies.” Which is exactly what Zach was wearing when I first met him: a button up and baggy ass jeans.

Thrifting has long been tied to skating, because of the similar values that both activities share. “Skating is moving your body, and there’s so much style that goes into it. There can be a skater that skates crazy—he can hit anything off of everything. There can also be a skateboarder that just does a clean kickflip, but the way he does a kickflip is stylish.”

From creativity to self-expression, just as a person can have his or her own individual style fashion wise, a skater can have their own style in terms of how they skate. Skaters have a long history of owning the narrative for a sport that has been looked down upon. Similarly, skaters have now taken control of buying second-hand clothing, amplifying the voices of marginalized clothing shops.

“Skateboarding hits on all sides of entertainment, and it bridges a lot of things. It’s multicultural,” Zach said. It bridges fashion, film, youth, community, mental health, and physical health all wrapped up in an artistic package. Because, after all, skateboarding is not just a sport: “It’s a form of art. Skating is about being in the moment, being free.”