UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Marium Abdulhussein

MANAGING EDITOR Karen Zhang

FINANCIAL EDITOR Jackie Truong

CONTENT EDITORS Hanna De La Garza • Loryn Smith

DESIGN EDITORS Aryam Amar • Mercy Tsay

PHOTO EDITOR Daniyah Sheikh

PR DIRECTORS Xinni Chen • Jackie Truong

WRITERS Aliza Ahmed • Susie Chen • Morgan Hurd • Keil

Lapore • Sana Motorwala • Dzung Nguyen

DESIGNERS Sarah Husney • Mya McGrath • Navya Nair •

Tiffany Vivi Nguyen • Kate Lynne Pudpud • Lauren Shee

PHOTOGRAPHERS Sarah Husney • Uyen Le • Annika Thiim

PR STAFF Vivian Chen • Tammy Nguyen

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Isha Harshe

MANAGING EDITOR Amy Pham

FINANCIAL DIRECTOR Anagha Hesaraghatta

PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR Fariah Ansari

CONTENT EDITOR Padma Vasanthakumar

PHOTO EDITOR Mridula Singh

DESIGN EDITOR Prakash Vasanthakumar

PROGRAMMING EDITOR Sanikaa Thakurdesai

WRITERS Fariah Ansari Riya Choksi Anushri Gade Isha

Harshe • Olivia Hemilton • Anagha Hesaraghatta • Khoa

Hoang • Sayona Jose • Sanika Kende • Krisha Patel • Vaidehi

Persad • Amy Pham • Sanikaa Thakurdesai • Quyen Tran

PHOTOGRAPHERS Kaniz Angel • Riya Choksi •Mridula Singh

DESIGNERS Riya Choksi • Nimrit Doad • Riddhi Gupta •

Sanika Kende • Amreen Naveen • Yasaswi Nimmagadda

• Linh Nguyen • Dan Pham • Ishita Sen • Mridula Singh • Padma Vasanthakumar • Prakash Vasanthakumar COVER

DESIGN Denise Ferioli

MODELS Anna Bulatao, Abbie Huynh, & Natalie Nguyenduc

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA

FACEBOOK Sparks at the University of Central Florida INSTAGRAM @ucf_sparks_mag

TWITTER @ucf_sparks_mag

sparks-mag.com

NATIONAL BOARD

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Jason Liu

CHAPTER DEVELOPMENT DIRECTOR Aleem Waris

MARKETING DIRECTOR Ingrid Wu

DEVELOPMENT DIRECTOR Chelsey Gao

CHAPTER MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR Catherine Le

CHAPTER MANAGER Bryant Nguyen

SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER Sally Zhu

LEAD GRAPHIC DESIGNER Esther Zhan

WEB DEVELOPER Chris Tam

FUNDRAISING MANAGER Kim Moya

MARKETING/SOCIAL MEDIA INTERN Jade Wu

UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL FLORIDA

PHOTO Reggie Ocampos

2 | SPRING 2022

E-BOARD

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Asma Ahmed • PR DIRECTOR Grace Casanova • FINANCIAL DIRECTOR Natalie Nguyenduc

PR MANAGER Narmeen Chanda • LEAD DESIGNER Denise Ferioli • LEAD DESIGNER Reagan Hollister • LEAD

DESIGNER Kaila Garton-Miller • WEB DESIGNER Liana Progar • LEAD PHOTOGRAPHER Reggie Ocampos • LEAD

PHOTOGRAPHER & COPY EDITOR AJ Johnson • COPY EDITOR Kissimmee Crum • COPY EDITOR Zoey Young

G-BOARD STAFF

WRITERS Asma Ahmed • Chelsea Della Caringal • Narmeen Chanda

• Zoey Young

PHOTOGRAPHERS Narmeen Chanda

• Denise Ferioli

DESIGNERS Asma Ahmed • Arianna Flores

Mayumi Sofia Porto

• Anna Pham

PR COMMITTEE Grace Casanova

• AJ Johnson

• Adrian Lee

• Caitlyn Mari Koerner • Liana Progar • Zohra Qazi

• Abbie Huynh

• Denise Ferioli

• Manaal Sheikh

• Narmeen Chanda

• Natalie Nguyenduc

• Kaila Garton-Miller

• Denise Ferioli

• Reggie Ocampos

• Reagan Hollister

• Kaila Garton-Miller

• Ilise McAteer

• Breanna Pham

•

SPRING 2022 | 3

A LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

DEAR READERS,

Sparks Magazine has always put creating space for our voices to be heard at the forefront. We all share as many differences as we do similarities, and as such, it is important that we are able to see each other outside of our own intersections. Only then will we be able to create a thriving space for ourselves and lay down a foundation for love to flourish.

In this issue, you will notice a constant between two themes: love and belonging (or the lack thereof). At its core, this issue represents how we define Sparks Magazine– home. These articles demonstrate our ability to find meaning by seeking out our own communities as we find our places between what we love and what we are meant to do. Finding what you love, from film and music to the people around us

and ourselves, and being able to dedicate your time and resources to it is a beautiful thing. For Sparks, love looks like teamwork. Love looks like wanting to be seen and heard, standing up for what you believe in, and knowing that you deserve a voice. Love looks like learning from others and sharing what you know. Sparks Magazine is a labor of love.

If I had the words to describe what this issue means to me, I would be writing volumes. Instead, I will try my best to put it in a few words: it is a work of art. Sparks has always emphasized creative expression, and with this issue, I can say with pride that our staff have let their many talents shine through. Over the course of this semester, I have watched the development of this issue with excitement for what is to come, and it is with great joy that I am able to present these works to you! I am forever grateful for the dedication and compassion our staff has for this organization and our community as a whole, and am honored to have been their Editor-in-Chief for another semester.

I hope you are able to see this love for yourself within the hard work and talent of our staff. I hope that their work resonates with you, and that you too are able to find love, wherever that may be.

SINCERELY,

ASMA AHMED EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

4 | SPRING 2022

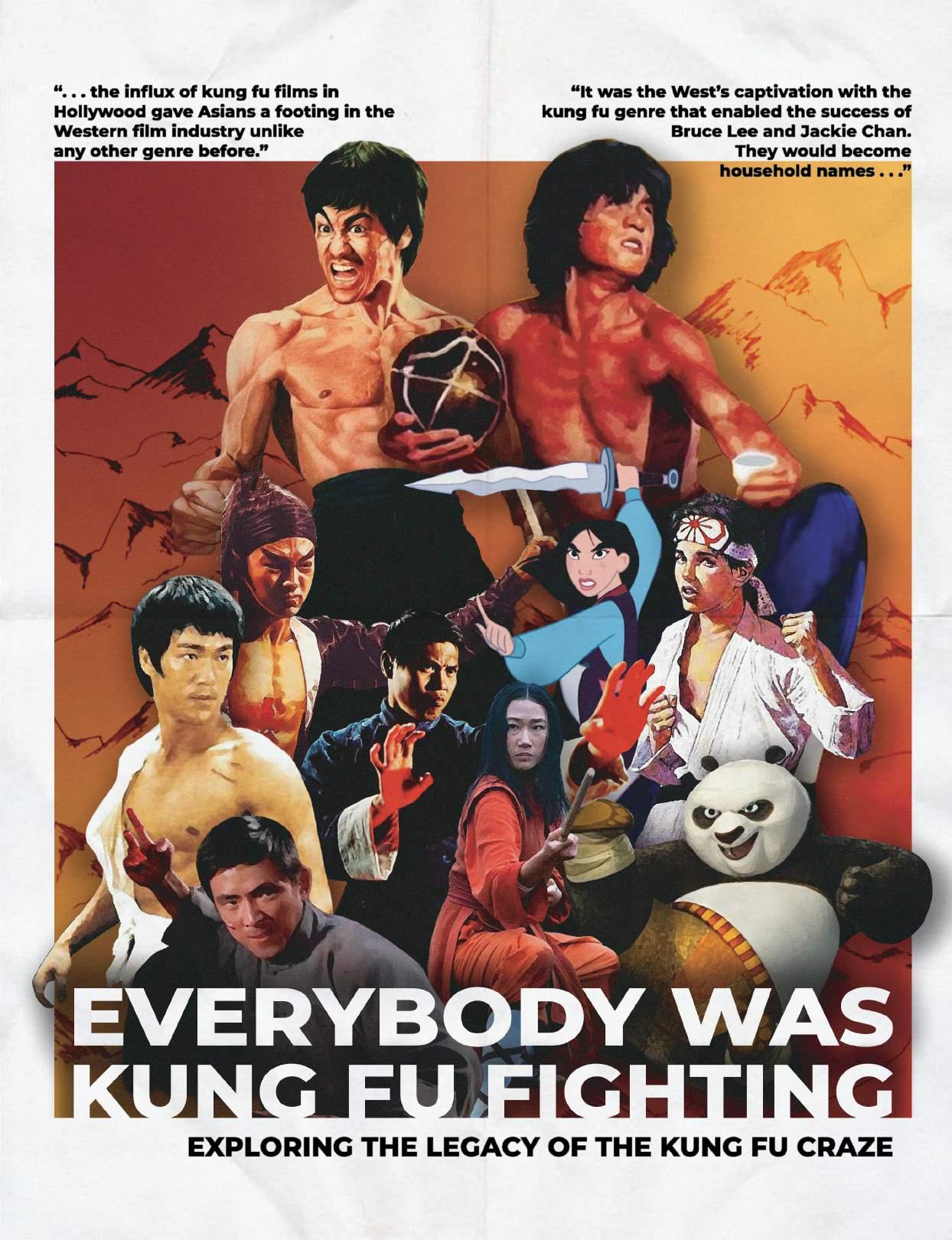

TABLE OF CONTENTS 09 12 14 16 19 22 26 28 30 06 EVERYBODY WAS KUNG FU FIGHTING ON BEING ASIAN AND HAVING ADHD WEDLOCK AND LOCKDOWN IN THE MOOD FOR LOVE & REVOLUTION FROM SILENCE TO VOLUME IN LINE AND BACK AGAIN HORROR AND THE SOCIAL SCENE THE STORY SO FAR THE “___” GUY RELATIONSHIPS PORTRAYED IN ASIAN MEDIA AJ JOHNSON CAITLYN MARI KOERNER ALIZA AHMED ASMA AHMED KRISHA PATEL LIANA PROGAR ZOHRA QAZI ZOHRA QAZI & ADRIAN LEE ZOEY YOUNG CHELSEA DELLA CARINGAL SPRING 2022 | 5

6 | SPRING 2022

by AJ Johnson design/Ilise McAteer

ong before the inkling of pursuing a film major entered my mind, I fell in love with movies, but not in the pouring rain, dramatic lifts and heartfelt stares kind of way. Instead, I would liken it to Dorothy’s pure, “There’s no place like home,” rather than Rose’s declaration, “I’ll never let go, Jack!”

Whether screened from the comfort of a couch or projected in a shabby room with floors sticky to the sole, films are one of my ultimate comforts. Simply put, I find them mesmerizing. I settle into my seat, eyes locked on the screen. Whatever story is told whisks me away for the runtime, and then some. Though some experiences are better than others — “Drive My Car” at the historic Tampa Theater was unparalleled whereas streaming “Don’t Look Up” at 2 a.m. left much to be desired — my film critique stops there. I’m easily entertained, to say the least, and ordering a large popcorn with free refills is just a bonus.

However, as I have grown older, the power of film as an agent for change has become more apparent. Though not every movie is beholden to this responsibility, it is impossible to ignore the power that film has, whether the production is cognizant of it or not. My own relationship with movies perfectly exemplifies this. I am enthralled, even obsessive sometimes, and the filmmaker is my enchantress.

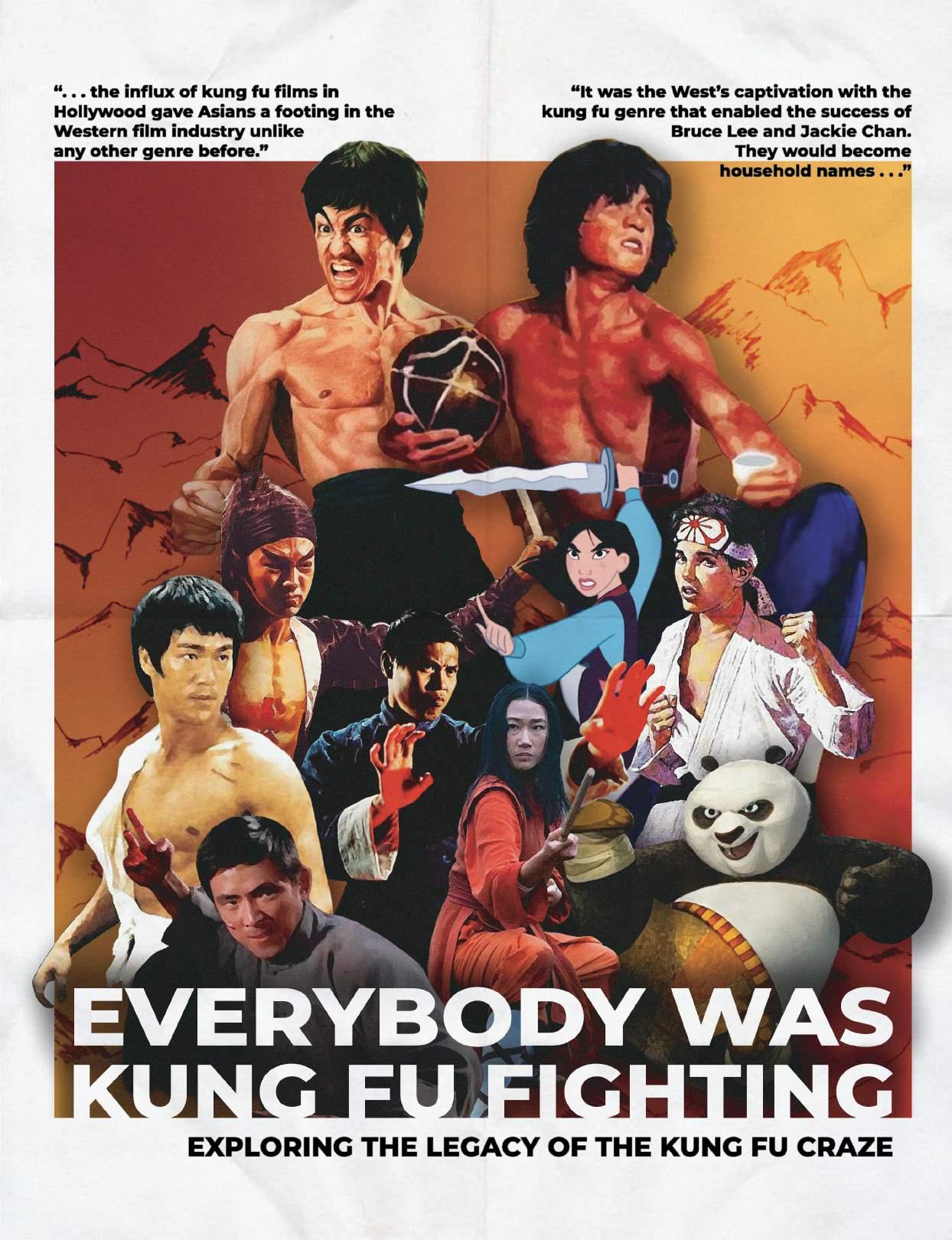

One of the very first movies that I can recall having such a hold on me is “Kung Fu Panda.” My best friend had it on DVD; in fact, she had both Kung Fu Panda films, which sat on a gorgeous wooden shelf adjacent to her collection of Disney movies. A few years later, the third installment would join its predecessors to be similarly well-loved and today, Dragon Warrior Po and Master Oogway hold a very fond place in my heart.

Barring the original “Mulan,” these movies were my first exposure to East Asian culture on the big screen and were certainly my introduction to kung fu. I didn’t learn who Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan were until middle school, at least five years after my first “Kung Fu Panda” watch. It would take even longer for me to know of the “kung fu craze” and connect the dots between how franchises like “Karate Kid” contributed to my classmates throwing a kick in a supposed imitation of “Chinese people.”

The portrayal of Asians in American cinema has a long history of persisting offenses, from whitewashing, to yellow and brownface, to the hypersexualization of Asian women. Though the influx of kung fu films in Hollywood gave Asians a footing in the Western film industry unlike any other genre before, it has not been without its consequences. The association of Asians and martial arts was brought into the mainstream where it has remained, with a recent example being the reference to the COVID-19 pandemic as the “kung flu.” Furthermore, stereotypes based on the East Asian men who fronted the kung fu blockbusters during the height of the craze continue to stifle the breadth of roles these kinds of actors are offered today and more largely, the perception of East Asian men by Westerners.

To understand the depth of these limitations, we must examine the history of martial arts in Western film, beginning with its origins. Kung fu cinema was born in Hong Kong during

the mid-1900s and expanded in tandem with Hong Kong’s growing economy. Notable films credited with bolstering the genre include “The Chinese Boxer” and “Vengeance,” both released in 1970.

The “kung fu craze” describes the success of these Hong Kong-produced films in America during the 1970s and 1980s, which were so popular that they even received their own name: chopsocky. This is a portmanteau of the dish chop suey and the term sock, as in a punch. First coined in 1973 by Variety reviewing “Five Fingers of Death” (1972), it quickly became a part of the general media’s vernacular and further reinforced the image of Asians in Western culture.

It was the West’s captivation with the kung fu genre that enabled the success of Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan. They would become household names with their debut films, “The Big Boss” (1971) and “Drunken Master” (1978), respectively, and were instrumental in the continued popularity of martial arts in American cinema. Lee and Chan portrayed a new kind of hero, with their influence differing from that of Sessue Hayakawa, the first Asian celebrity actor in Hollywood. Hayakawa was restricted to roles where he played forbidden, often vengeful lovers, and his high-profile contributed directly to the negative messaging about interracial relationships during the 1900s. As the Center for Asian American Media’s executive director Stephen Gong puts it, “[Hayakawa’s] transgressive stardom . . . elicited a ‘forbidden’ fan response . . . The industry was quietly but completely determined not to allow Asians or nonwhites to become ‘stars.’”

In contrast, Lee and Chan headed storylines that Western audiences had rarely seen before. The unfamiliarity of the kung fu craze went beyond the newness of the genre; it was more remarkable that Asians were leading protagonists. From Lee sparring in “Fist of Fury” (1972) to Chan outmaneuvering his opponent in “The Big Brawl” (1980), they were skilled, likable and most of all, victorious. The international box office success that these films garnered led major Hong Kong studios to market movies specifically for Western audiences.

With Bruce Lee’s death in 1973, a phenomenon known as Bruceploitation arose. Hong Kong studios feared that without the face of kung fu cinema in Hollywood, profits would suffer. Actors began to appear on the bills of martial arts films with names like Bruce Li, Bruce Lai and Brute Lee. This pattern, though humorous, speaks to the importance of Bruce Lee in revolutionizing the kung fu genre. Though he only starred in five films, as Nicholas Raymond explains for Screen Rant, Lee “made studios realize that trained martial artists were essential to kung fu movies.” This can be reflected in Hollywood’s continued absorption

L

SPRING 2022 | 7

Lee and Chan headed storylines that Western audiences had rarely seen before. The unfamiliarity of the kung fu craze went beyond the newness of the genre; it was more remarkable that Asians were leading protagonists.

of the genre, such as by the extensive training that Keanu Reeves received for “The Matrix” (1999) and Uma Thurman underwent for “Kill Bill” (2003).

Following Lee, Jackie Chan was the next major Asian actor to find critical success in Hollywood. He similarly began his career in Hong Kong but transitioned after being catapulted into the international limelight. Though Chan returned to Hong Kong during the late 1980s, he found renewed success in the West with “Rumble in the Bronx’’ (1995) and the “Police Story” franchise. He is still active in the filmmaking industry, despite moving away from stunt work during the early 2010s. Chan may have been dependent on the legacy of Bruce Lee, but he is a critical contributor to the martial arts genre in his own right, particularly for his work with action comedies.

As a side effect of furthering the chopsocky genre, Lee and Chan unwittingly cemented the synonymity of the Asian actor and the martial arts role. How do we reconcile the irrefutable importance of martial arts cinema in bringing Asian actors into the mainstream with the limitations it has posed on the exact kind of actors it gave opportunities to?

This “all Asians know kung fu” trope is discussed in an article by Diep Tran for NBC News. Tran acknowledges that “because Hollywood tends to replicate things that sold well before, playing a kung fu fighter soon became one of the only ways that Asian actors could get work in Hollywood.” For example, much of Lee’s personal philosophies about openness, expression, and personal growth that informed his training in martial arts have been forgotten. Instead, he is largely remembered for his physicality alone. His daughter Shannon Lee points to him as “the origin of the kung fu master stereotype” because he “[made] such a huge splash in Hollywood,” but argues that “there was not enough of that continued impact from other [Asian Americans] . . . just due to the systems in place.”

Kung fu is traditionally a symbol of nationalism and virtue for Chinese citizens, but much of this cultural significance was lost on American audiences during the kung fu craze. Furthermore, the production and distribution of martial arts films that were produced in America, inspired by the original Hong Kong films, was controlled by white executives. This only reinforced the systems and stereotypes that Shannon Lee speaks of.

Martial arts cinema has remained an active industry, though to a lesser extent than it was in the 1970s and 1980s. However, a number of opportunities for Asians to make their mark on Hollywood have arisen over the years.

Television shows like The CW’s martial arts action-adventure drama “Kung Fu,” which began airing in 2021, wish to redefine the genre by exploring American identity and politics through the lens of a complex, majority Asian cast. The series’ director, Bao Tran, explains that “Asian American kung fu narratives are using the genre to explore contemporary issues of identity” in contrast to the genre’s focus on fantasy and crimefighting elements during the kung fu craze. This helps break away from the original martial arts films that shaped the stereotypes Asian American men have been subjected to for decades.

“Kung Fu” showrunner Christina M. Kim has discussed how her decision to make her lead character female pushes the boundaries of the martial arts genre. Though there are several well-respected female martial artists in the industry, they have often been overshadowed by their male counterparts, especially in the West where they were not featured to the same degree as in Hong Kong.

As the creative team behind “Kung Fu” represents, one of the biggest differences between martial arts films coming out of Hollywood during the kung fu craze and today is who the filmmakers are. The boundaries of the genre are changing and stereotypical roles are being challenged because its creators are Asian American.

As Diep Tran writes, “Bruce Lee wasn’t able to get complete creative control over his work until he made films in Hong Kong. These newer properties [in Hollywood] are headed by Asian American creators, who have control over their vision.” Relevant to this conversation is the lack of non-East Asian actors in the West. There has been no such “craze,” or importation of regional cinema into Hollywood from other parts of Asia. While Bollywood thrives and has its share of interest in the West, Hollywood remains the largest film industry with the most international influence and it is decidedly absent of diverse representation for Asians. Though East Asian actors are making waves, there remain many hurdles in the way of securing proper representation. Non-East Asian actors are hardly present at all.

The role that martial arts cinema has played in the multifaceted issue of proper representation is only one factor of many, though analyzing its history reveals an indisputable conclusion: Without the kung fu craze, Asians would not have the presence in the industry that they do today. The work of icons like Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan introduced American audiences to the possibility of Asian heroes, and while Asians face stereotypes borne from the popularity of martial arts cinema, the precedents are being rewritten by a new generation of filmmakers.

Like the Soothsayer says in “Kung Fu Panda 2,” “Your story may not have such a happy beginning, but that doesn’t make you who you are. It is the rest of your story, who you choose to be.”

The boundaries of the genre are changing and stereotypical roles are being challenged because its creators are Asian American.

8 | SPRING 2022

Kung fu is traditionally a symbol of nationalism and virtue for Chinese citizens, but much of this cultural significance was lost on American audiences during the kung fu craze.

ON BEING ASIAN AND HAVING ADHD

The first time I had heard of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, also known as ADHD, was when I was introduced to the Logan Touch. I was in fourth grade walking to lunch with a couple of my friends from class. While we were chatting about whatever problems 9-year-olds face, I felt a fingertip jab the back of my arm and a kid from another class exclaimed, “You have the Logan touch!” He ran across the courtyard into the cafeteria, giggling triumphantly.

Confused and somewhat afraid, I turned to my friends with concern.

“What did he say?” I asked in disbelief. “He said that you have the Logan touch,” one of them responded dryly, starting to pick up her pace again.

“You know the Cheese Touch from ‘Diary of a Wimpy Kid’? It’s the same rules as that but Logan is the cheese. Anyone who touches him, even if it’s a total accident, is treated like Logan until you touch someone else to get rid of it.”

Logan was notoriously known as the most annoying kid at my elementary school. While he was undoubtedly intelligent and was even enrolled in the Gifted program, it could be said that “he didn’t apply himself.” He couldn’t sit still for his life, letting his arms sloppily flop around and he’d always try to talk to the kids around him in the middle of a lesson. We knew that he had ADHD, but we never were given a proper explanation as to what that meant. On top of the other issues he was dealing with, we were making his life even more difficult.

Up until my diagnosis in the eighth grade, I always thought of ADHD as something only chaotic white boys could have. The Logan Disorder. So, you could imagine my shock when the psychologist who did my testing sat me down at the beginning of my debrief and told me—an organized, generally quiet girl—that I had the same diagnosis as Logan. Of course, being fairly older and slightly more educated about ADHD as a concept, I could definitely empathize more with kids like him. Their restlessness was just a part of who they were. It is pretty miserable to be glued to your seat all day long and feeling like you’re going to implode if you don’t move. In all honesty, I felt the same way myself. I just could never imagine myself being able to act in the way those kids did. If any of my relatives saw me behaving

in that way, they’d be calling the local odaisan to purge me of any curses that could have been placed upon my family and I.

I know I’m not the only person who feels like this. Why is ADHD known as the rowdy white boy disorder? Why do we never think of Asians or Pacific Islanders?

Asians and Pacific Islanders are often under researched in psychological studies and as a result have been severely underdiagnosed compared to other racial groups. According to a recent chart by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, ADHD is more than twice as likely to be diagnosed in boys rather than girls–and that’s without race in the equation. For every 11 white kids that are diagnosed with ADHD, only 3 Asian kids are diagnosed. Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders aren’t even included on the chart; only asterisks and dashes appear across their rows, indicating that for this group, there is no significant data being collected. Even when Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders are included in ADHD research, they are lumped together with Asians so for both parties there aren’t any separate sets of data, causing unnecessary confusion.

This is all thanks to good ol’ systemic racism served with a side of cultural bias. Asian Americans are commonly referred to as the “model minority,” the racial minority group in the United States that seemingly has it all,

SPRING 2022 | 9

by Caitlyn Mari design/Manaal Sheikh

despite how they were treated throughout the nation’s history. They are often stereotyped in a seemingly positive light and are described as orderly, motivated, smart and obedient. It has been statistically proven that Asians tend to have higher levels of income and academic achievement compared to other groups in the U.S., but this success equally has a cost. This monolithic conception of an entire race is harmful because it fails to consider the tremendous amount of pressure being put on Asians to perform well, no matter what their background is. Asians who aren’t considered to be “exceptional” by society’s standards–people who get average to poor grades, aren’t a part of all of their schools honor societies and/or have career interests or hobbies that their parents or community don’t approve of–may feel like who they are at the core is inherently wrong. Self-esteem is hindered and confidence becomes dependent on purely external factors.

It further excludes the fact that most Southeast Asian groups are largely left behind in this so-called Asian American Dream. The U.S. Census revealed in 2019 that Burmese American households make a little over $40,000 in annual income while Indian American households bring in over $120,000. Also, I cannot emphasize this enough, but there are barely any studies conducted on learning disability symptomatology among Pacific Islanders. In an article by Liu & Alameda, the researchers point out that even though Native Hawaiians are significantly more likely to have a diagnosis compared to nonHawaiians, there is still a large gap in mental illness research about them. These weren’t even official diagnoses; this statistic was a result of a survey sent out to Natives that only asked them diagnostic questions. Most school authorities, psychologists and psychiatrists fail to grasp the weight of context and permit unconscious bias seep into their decision making. A predominantly white workforce failing to question their own biases and stereotypes makes Asian kids silently suffer.

“Don’t bring shame onto the family” is a phrase that was gradually chiseled on the surface of my amygdala throughout my childhood. The traits of poise, tact, and modesty were some of the most important traits to have in my family. Gender didn’t make a difference in how this was upheld; boys and girls were equally expected to act in a respectful way. My grandmother was the primary enforcer of this concept. She taught my mom and her siblings that they shouldn’t eat or drink at the same time they were walking; nobody was

allowed to go out with unironed clothes; public displays of affection were inconceivable as well as talking about politics, religion or money. This all boils down to one point: you cannot act out of line. Being disruptive, impulsive and ill-mannered were looked down upon the most, especially if you were in public.

A lot of other Asians can probably relate to this. I was raised in Hawai’i for most of my early childhood, swimming in a melting pot of Polynesian and Asian cultures who all upheld collectivist ideals and mores. Collectivist cultures are characteristically known to emphasize the needs of the group–specifically the family–over the needs of the individual. Elders are held to the highest level of respect and their word is the final say-so. When the family elders are happy, the individual can be happy. When the family elders are upset by something you do, something about you needs to change; or, if you did something beyond forgiveness, you may even have to leave the group entirely. This loyalty to the family is known as filial piety and causes the people within the group to repress their emotions and individual wishes. Confucianism additionally plays a foundational role in many East Asian cultures, which emphasize keeping social harmony, respecting elders and embracing education to the fullest extent.

There is a tendency for Asians to avoid seeking out mental healthcare services. A 2007 study conducted by the University of Maryland School of Public Health’s research team investigated the major stressors of Asian American students. One of the top reasons as to why Asians strayed away from mental health services was because discussing topics related to mental health was considered to be taboo, leading many people to dismiss or deny their symptoms. My mom can attest to this: in Hawai’i, it was considered highly taboo to go to a psychiatrist when she was growing up. “We were brought up to think that only crazy people went there,” she explained. “That’s just it. If you go to a psychiatrist, you’re a crazy person. It’s something we just didn’t talk about. And it never came up in our family where someone said ‘I want to talk to someone.’ My mom would say that ‘Crazy people only see a psychiatrist.’” It wasn’t until later on in her life that my mom would talk to a psychologist, which she attributes to my dad who was already seeing one. It took her a while to finally get her there, but to her relief her psychologist was also a local Japanese man who fully understood her cultural background. In another study titled “Cultural

10 | SPRING 2022

perspectives on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A comparison between Korea and the U.S.,” researcher SeokYoung Moon discovered that Korean children having a disability or mental disorder reflects negatively on parents and other authority figures, which in turn causes their parents to blame themselves for their child’s perceived “deficiency.” This belief further exemplifies how filial piety and Confucian ideals hinder people from seeking help even if they desperately need it.

After my family and I moved to the mainland when I was seven, it seemed like every other week my parents received comments on how “well-behaved” their children were. I remember how pleased my mom would look passing this information on to my little brother and I, giving us a little speech about how lucky her and my dad were and that we were so mature for our ages.

accomplishments by contrasting myself with the people I love, the people I found community in, made me feel unworthy of their presence in my life. Furthermore, it minimized my loved one’s own struggles and insecurities when I put them on that pedestal.

As I got older and made increasingly more decisions that jeopardized this high standing with my mom or other authority figures, I became hyper aware of my behaviors and attempted to limit the amount of offenses I could potentially make. A majority of my friends had neurodivergent traits as well (and in the future were coincidentally diagnosed with ADHD) so thankfully I had them to relate to, but with my other peers, I didn’t feel like I was taken seriously. Learning to mask behaviors that felt normal to me, like getting overly emotional around others or gushing over my new favorite topic of fixation, felt like my only key to success. I abused my medication and turned myself into a productivity machine, watched countless YouTube tutorials on how to “properly” conduct myself in social situations (whatever that means) and would stay quiet about my political beliefs and morals even when I felt strongly about something.

This method of trying to blend in worked for a while up until my sophomore year of college when I finally burnt out. I felt like I lost countless parts of myself by this time; I had no hobbies, my friendships and relationships felt faulty because I wasn’t showing up as my true self and when I looked in the mirror all I could see was a total, complete fraud. I would compare myself to my other friends with ADHD who I perceived as more successful, hilarious and creative; they seemed to know how to make their diagnosis work for them rather than let their diagnosis control them. I felt like I couldn’t fit the stereotypical Asian definition of success or the cool, witty and girlboss ADHDer that those neurodivergent TikTok accounts love. Discounting all of my unique traits and

Today I can finally say that I am starting to pick up the pieces of my identity that I thought I had lost and fit them together in a way that is empowering and uplifting. It’s taken lots of introspection, difficult but honest conversations with others and practicing radical self-compassion even on days where I feel like a formless blob. Letting go of generational shame is no easy feat and is a slow process. Dismantling racial stereotypes is even more difficult, especially when we are surrounded by people who still buy into them everyday. Collective healing is only possible when we take it upon ourselves to question what we’ve been conditioned into. It also means that we need to redefine a new normal for what ADHD looks like (so our first introduction to it isn’t something that resembles the Cheese Touch) and what it means to be Asian American. We can maintain our cultures and identities without the presence of shame within it. And for my neurodivergent Asians reading this who are still figuring it all out: take your time. Give yourself hugs and let yourself cry and allow yourself to feel everything you were holding in for so long wash through your body–immerse yourself in it. Talk to others who you feel comfortable with about your feelings when it’s appropriate. Teach yourself what your needs are and ask for accommodations when you feel ready; you aren’t any weaker for knowing what you want and need to thrive. You are enough and always have been enough.

SPRING 2022 | 11

“That’s just it. If you go to a psychiatrist, you’re a crazy person. It’s something we just didn’t talk about. And it never came up in our family where someone said ‘I want to talk to someone.’ My mom would say that ‘Crazy people only see a psychiatrist.’”

Wedlock and Lockdown

TheeffectsofCOVID-19onSouthAsianweddings

Finally, the day she’s been waiting for. The day she’s been dreaming of. A bride’s wedding day. After months of planning the theme, the decorations, the reception and the guest list – it is finally time. She gets ready, her family members helping her into her dress and ensuring that she looks her best on her special day. Once she’s ready, she is escorted – not to a wedding aisle, but to her… living room? In front of her are her family members smiling and taking pictures – not in person, but through a Zoom call. She and her spouse-to-be say their wedding vows, and just like that their virtual wedding is complete.

While this may seem like a far-fetched, exaggerated scenario, this has been a reality for many getting married during the COVID-19 pandemic. Large, extravagant processions are reduced to short services. Milelong guest lists are capped to a

handful of close and immediate family members, with the rest of the attendees being faces on a screen or voices through a phone, congratulating the couple from afar. While these are necessary measures to ensure everyone’s safety, they are far from what many imagine when they think of their wedding day. Those who could not afford to push their wedding date back held a majority of their wedding virtually, maintaining social distancing. An article from ABC News Australia focused on one couple getting married entirely over Zoom. “Instead of the groom circling the sacred fire by her side – an important rite of a Hindu marriage ceremony – he was beamed in from Sydney onto Ridhi’s computer screen via the video conferencing platform Zoom.”

Thus, one can see that the impact that the early pandemic had on traditional weddings was drastic. Wedding planner

design by/ Tiffany Vivi Nguyen model/ Esha Sattar

Written by Aliza Ahmed 12 | SPRING 2022

photography by/ Sarah Husney

and coordinator Kiran Mohan of Sonaa Events expressed the difficulties she faced in early 2020. “The wedding that I

weddings – more specifically, South Asian weddings – are well-known for their extensive guest lists and celebrations spanning several days. Hence it is no secret that the pandemic and the health regulations that came with it had a major impact on similar important cultural practices. Anna Price Olsen, writer for Brides, an online bridal advice website, wrote an article exploring weddings that were held early in the pandemic. One couple, Jasmine and Avneet Singh, had planned to have a traditional Punjabi wedding. “The actual day was far from what we had ever imagined.”

Kamila*, a bride from Orlando who tied the knot in a traditional Indian-Muslim wedding ceremony in the summer of 2021, expressed her dismay about some family not being able to attend due to COVID-19, “I was definitely sad since 90% couldn’t make it, but I was happy they were able to join me through Zoom.”

Even in 2022, after such restrictions have been lifted, traveling comes with its risks. Jennifer Coenen, travel writing professor at the University of Florida, recently attended her nephew’s IndianSyrian Orthodox Christian style wedding this year. She noted that there was a large number of people at the event, but that there would have been “One or twohundred more people at the reception if it hadn’t been for COVID.” Again, the reduced attendance was due to fear of spreading COVID-19 via inter-state and international traveling.

While nowadays drastic measures such as hosting weddings entirely online are scarce, there are still lingering remnants of early-pandemic health procedures that remain in use for most celebrations with large gatherings of people. According to Quartz India, for weddings planned during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, about 59.05% of couples prioritized the vendors’ vaccination status. Kamila required all guests to be vaccinated at her wedding, as she “wanted everyone to be safe especially since we had a lot of elders coming.” In addition to this, as per any large gathering of people, masks were expected to stay on unless eating or taking photos. Modifications to how food was prepared and served were not uncommon to see as Kiran described, “Sikh weddings for example, for longer services it [food] had to be pre-plated. For buffet services they had to have servers behind plexiglass or masks.” While necessary for health reasons, the sight of servers behind walls of glass and masks may be offputting in contrast to the open, allyou-can-eat buffets typically seen at wedding receptions.

Despite the initial hardships, after two years of living in a pandemic, people began to adjust. Kiran explained that, for many of her clients, the pandemic “changed their perspective on life, meaning they don’t necessarily need the gigantic floral arrangements, they don’t necessarily need the big elaborate live food stations. All they needed was close family and friends to be able to celebrate that union.” Coenen described a beautiful and heartwarming fusion-style wedding ceremony between her nephew and his wife-to-be that went off without a hitch despite the pandemic. She and her sister wore traditional saris and lehenga outfits with glammed-out decorative masks to match, participated in a Mehndi party, a traditional milk ceremony, and even walked her nephew down the aisle on his wedding day. She stated, “I had such a wonderful time, it was a very meaningful experience in my life.”

people are beginning to open up again to the idea of large gatherings. While now there is no obligation to wear masks, there is still the option to do so if one feels it is necessary. Coenen stated that she and her sister “chose specifically to wear masks,” mainly due to the fact that they had traveled from the coasts of the United States, “We didn’t want to bring anything to anybody and we didn’t want to take anything home with us.”

Kamila remarked that – as expected of a wedding – her wedding was “an exhausting day but it was a beautiful one, surrounded by the people I love.” When asked whether there was anything she missed having at her wedding that she could not have due to COVID-19, Kamila said, “Honestly, just my family that couldn’t make it. Other than that, the whole wedding went perfectly and I couldn’t have asked for anything better.”

*Name changed to preserve the anonymity of the interviewee.

“Our 300 -plus guest list shrunk down to just three.”

This story is by THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA SPRING 2022 | 13

“It was just kind of weird to see at a wedding.”

Relationships Portrayed in Asian Media:

Relationships Portrayed in

Asian

Media:

The Problems With BL The Problems With BL

CONTENT WARNINGS: Mentions of Sexual Abuse, Rape, and Bullying

Iwas first introduced to Boys’ Love stories in my senior year of high school. I was looking through dramas to watch and I stumbled upon a Thai drama called “Make It Right.” The plot sounded interesting, so I clicked to watch the first episode. Within the first five minutes, the main character Fuse, who was heavily drunk, drops his keys and along comes Tee, a friend whom he hasn’t seen in a while bends down to grab it the same time he does. The two characters touch fingers and look into each other’s eyes. I was hooked.

BL is a somewhat controversial genre as it depicts romantic relationships between men. It was first introduced in the 1980s and was created mainly for teenage girls. The usual role of a gay man in a show is to be a side character that doesn’t contribute too much to the plot besides being the “gay best friend.” They are mostly shown to be overly feminine and a comic relief. So when a show comes out that actually focuses on their lives, it suddenly becomes interesting and exciting. BL has become immensely popular in Asian countries, especially Thailand and Taiwan. Thailand has been producing BL shows since before 2011 but it did not fully blossom and garner its fan base until 2014. Japan also has yaoi, the anime and manga form of BL. Yaoi has been around for much longer than live-action BL as it is easier to produce and would get into many controversies.

Though BL had come under attack for depicting menloving-men relationships, not all of the criticism is rooted in homophobia. BL’s problem isn’t what lies between its harmful and portrayal of gay men or its fans receiving unfair

criticism because it was made for women (women are always unfairly criticized). It is not because of homophobia or the lack of representation in the genre. BL’s problem is how it was created. Since it was made for women and not solely for representation, the way they have been structured to portray love stories of men is the main problem.

“It is not because of homophobia or the lack of representation in the genre. BL’s problem is how it was created.”

“The ones I’ve seen are problematic in that—like I’ve said— they weren’t made for me,” said Seth Gozar, a University of North Florida alumni. “The plots and characterizations lean on rigid clichés that appeal to the BL demographic. It gets tiring to see the problematic tropes from that genre repeated over and over again, such as a spineless bottom, an abusive top, leads that aren’t too gay, and more varied portrayals of boys’ love relegated to homophobic punch lines.”

Romanticizing rape and sexual abuse in these shows are very common. One of the more “masculine” characters would often be too aggressive towards the other and force them into situations they expressed they don’t want to be in. The latter would then get sexually assaulted or even raped by the other character but somehow they fall in love and end up together. If this was a straight romance: the assaulter would’ve been immediately painted as the villain, the main character would definitely not have

by Chelsea Della Caringal design/ Anna Pham

2gether: The Series (2020), Source/ GMMTV

14 | SPRING 2022

fallen in love with them, instead, they would be saved by a dreamy man. These tropes in BLs make sexual assault so easy to get away with simply because they are men. People often forget the fact that men, too, get sexually assaulted.

The popular “top” and “bottom” trope is also a heavy topic to point out in the BL community. Most shows would make it obvious which one is the top and which one is the bottom i.e., the character that is the more dominant or masculine one. The top would usually treat the bottom as if they were female and would even refer to them as their “wife.” It is a very stereotypical scenario of what a straight couple would be like. These shows do not address the dynamic between two male couples and their struggles in society. What I’ve noticed in most shows is that the characters would hide their relationship at first but the moment they come out, everyone suddenly becomes accepting of them and everything is all rainbows and unicorns. They don’t show the real struggles of samesex relationships and how hard accepting people can be.

“I wish I could enjoy BL dramas more,” continued Gozar. “Most of my BL dramas I’ve seen are Asian productions, and on paper they sound great--watching romance where the leads look like me. However, most of the dramas are obviously not made for me, and that’s my main barrier of enjoyment.”

just as much as there are in BL and they shouldn’t be given a free pass just because they are aimed towards men.

There aren’t a lot of women in BL which is understandable, but the few that are present are also not represented very well. The portrayals of women in BL shows are always mean. They’re usually the villain. Most of the time, the typical trope that is used towards writing a female character in a BL is that they are used as the main character’s girlfriend as they fall in love with the guy they are supposed to end up with. This ends with the main character cheating on their girlfriend just to be with the other guy they started falling for. They end up becoming the villain when they realize that their man is being stolen (though they were portrayed as a very nice person in the beginning) and they do all sorts of ridiculously mean things to keep their boyfriend. They are made for the audience to hate on. While their feelings are very much valid, they are put in a negative light because the woman wasn’t the one who’s supposed to end up with the main character. It is, after all, a BL story.

Yuri or GL is the female counterpart of BL. It encounters the same problems as BL as it is often made for men’s viewing pleasures. As of this writing, there aren’t many GL shows that are produced as they aren’t as popular as BL. Yuri, however, is very mainstream as they focus more on the sexual side of the romance between two women. There are also themes of rape and sexual assault in Yuri’s storylines

Though these shows are only a work of fiction, these works of fiction affect people’s perception of reality. These constant inaccurate portrayals of same-sex relationships often give fans false hope. A very good example of this is the Thai BL show that aired in 2016 called “SOTUS.” When the character Khongpobe finally comes out to his friends that he and the character Arthit are going out, his friends ask, “Oh we didn’t know you were into guys.” In which, Khongpobe simply answers, “I don’t like guys, I only like Arthit.” These lines give the girl fans the sense of false hope that they can have a chance with the character that they liked from the show, or even the actor themselves. By saying that they’re not completely only into men and are only into that one person that the fan approves of, it gives the fans the satisfaction that they crave for and a character to project onto.

There aren’t many Western BL being produced as of yet, however, ”Love, Simon” and “SKAM France” have some very good plots. The tone is much different from Asian BL as Western ones are more direct and open to their desires.

Boys’ Love dramas have become a phenomenon and it will continue to get bigger as years pass by, especially in a generation where everyone is more accepting of their sexuality. I still remember when one or two BL shows would only get produced a year and now there are BL shows that are airing back to back. Representation and community are always good but I hope that the producers of these shows learn the dangers and impact their stories have on society and the LGBTQ+ community. The BL community still has a long way to go but we can always learn from past projects and make something better from our mistakes.

ThranType: The Series (2019), Source/Me Mind Y

“...On paper they sound great—watching romance where the leads look like me. However, most of the dramas are obviously not made for me, and that’s my main barrier of enjoyment.”

SPRING 2022 | 15

— Seth Gozar

In the Mood for Love &

Revolution

On the foundation of love in activism

Is this love?

For as long as I can remember, preparing for the worst has always been a part of my routine. Growing up as a South-Asian-Muslim-American in post 9/11 America, I was not allowed the same kind of innocence my peers had as children. I learned that for every hyphenation my identity accrued, I was perceived as a greater threat against what it meant to be American, and therefore unwelcome. Eventually, “go back to where you’re from” became less like vitriol hurled at me and more like kindness. After all, isn’t it a much safer place to be where everyone else looks like you, knows your culture and speaks your language? This country had no love for me, but I was still loved within its borders by the people I came from, and that had been enough.

What I was never able to prepare for, though, was the sudden alienation from where I once belonged. Through greater self discovery, I became divided further by these hyphenations, and gradually became less like the people I found refuge in. I was no longer the curious and intelligent child but the insolent and disrespectful young woman who didn’t know her place as I resisted gendered expectations and grew critical of bigoted traditions. I grew aware of my culture’s flaws– the classism, racism, rampant misogyny

and homophobia, the refusal to accept those who went against the norms. I aired out these flaws and I embodied their fears, just like the Americans had. I became hard to love.

But is this love?

I often find myself grieving my own inability to find the connections I yearn for in life. Yet, I find myself wanting better for the very people I felt abandoned by. Within my complicated relationship with my own community, I can’t help but empathize. They are only like this because they have their own traumas to process. No one can hear my pain because there are things that they don’t talk about, deep aches that cannot be identified let alone cured.

I can separate myself from my culture, my community, myself but to an outsider, I am one of them still. Perhaps the reason I cannot come to hate my own community is because they are me, and whether I accept it or not, I am a part of them. I cannot simply reject or shake off the things that cause me to be marginalized, and so, I am once again a member of the community that I abandoned but cannot let go–the community that abandoned me but where I remain in its grasp.

Grief. Feelings of low self-esteem–rejecting the communities I was a part of because they were deemed

unworthy and unwelcome by those around me and because I was no longer welcome in the spaces I belonged to. I blamed myself on both accounts, using internalized racism as a shield and a means of assimilation. I viewed these hyphenations as teeth, defanging myself in order to make myself more palatable, ignoring how I would never be able to smile the same way again.

Grief. A growing apathy, a poisonous thing that festers if left unchecked. We live in a time where every bad thing that happens in this world is broadcast on big screens and streams of information that follow us relentlessly, all while we feel helpless to stop it. At the same time, we live in a world where humanity is devalued unless it is profitable or productive. How do you care about anything in a society that clearly doesn’t care about you?

It is very easy to fall into this pattern of thought and grow resentful. It’s almost comforting in its familiarity, masochistic as it is. The loss of love and the struggle to navigate the notion of love is a concept that bell hooks was all too familiar with, writing in her book All About Love: New Visions: “but it was love’s absence that let me know how much love mattered… we can never go back, I know that now. We can go forward.” In the study of care ethics, a feminist approach to moral

by Asma Ahmed art & design/ Asma Ahmed

16 | SPRING 2022

education, love and justice are intertwined, and it is implied that there is significance in the foundations of relationships and dependency on others. bell hooks writes: “there can be no love without justice.” The loss of love had given hooks the opportunity to look at the concept of love objectively. “To love consciously, we have to engage in critical reflection about the world we live in and know entirely.”

Running on resentment, your entire platform becomes a constant cycle of antagonism. You begin to isolate yourself and alienate others, and your capacity to see beyond yourself shrinks. Once you’re alone do you wonder– who are you fighting for? It’s one thing to be anti-oppression, to avoid it, and condemn it loudly– all from a position far removed from the actual site of the conflict. But where is your solidarity? Are you uplifting the people facing the brunt of the oppression you stand against?

Love and the desire for better for your community should be the driving force behind activism. Separating emotion from community does nothing but push people away from activism, making it an isolating experience rather than a collective effort. Ultimately it becomes detrimental to an individual and their cause. You are not alone. There have been people who have come before you to create the tools and language you have now, and that there will continue to be people after you to prolong the fight– as long as you give them the ground to do so. In other words, you need to know the people you’re fighting for and fighting with in order to really fight for anything. Love does not exist in a vacuum, it requires dedication and understanding. In hooks’ words, “being aware enables us to critically examine our actions to see what is needed so that we can give care, be responsible, show respect, and indicate a willingness to learn.”

For University of Central Florida professor of humanities and cultural studies, Dr. Christian Ravela, community is both his identity and profession. “My work is driven by love and curiosity for these communities” he says. “I grew up in Southern California in a largely Asian American suburb of Los Angeles. As such, it forged me and others in obvious and complicated ways that merit attention and acknowledgement. My academic community, on the other hand, has been the vehicle to explore such questions and gain critical distance and appreciation… [for a panethnic racial community like Asian Americans] The internal differences, multiplicity, and heterogeneity of Asian American as a category puts so much pressure on the very notion of community.”

Khaled Itani, a UCF alum, med student, and former leader within the undergrad Asian American community at UCF proposes that the solution to apathy is collective effort. “If we are apathetic from now in relatively minor positions, what guarantees us that once we have a greater say in society that we will be in the headspace to influence the discourse? Our communities [...] need to believe in the power of collective change and part of that is believing in ourselves, it will always be an uphill battle but if that’s our argument for complacency then what is the point of anything?

Not taking a risk is a risk in itself.” The key is to reach out to others despite the opposition you may face.

Itani connects his activism with spirituality, describing his view on his community with: “this dynamic [community] has multiple layers as not only are we connected by cultures with ultimately similar values and interconnected histories via the Silk Road and Indian Ocean Trade, but also we share a post-imperial identity as children of the global south who grapple with the effects of colonialism and empire on our histories in one way or another… being able to bring people together is a struggle no doubt, but it is a humbling privilege and quite frankly an act of worship.” For him, his relationship with his community is a labor of love, appreciating the ways the facets of his identity differ and overlap. This in turn allows him to view these communities as a collective of individuals and empathize

SPRING 2022 | 17

with them on a more personal level. He is unafraid to connect with others and understand where they are coming from regardless of where they stand. “It takes an element of faith to soften your heart and ask why our communities are the way they are [...] from fear of losing everything they gave themselves up for to build, to they themselves becoming jaded after being so optimistic and believing in the power of people to change their conditions before some tragic war or socioeconomic hardship beat that out of them, life is hard and people deal with it differently”

What I had to learn while navigating my grief was the maintenance of boundaries, objectivity, forgiveness, and recognition. A slow and painful process, the ethics of care functions as the key to balancing yourself and maintaining a healthy relationship with yourself and others. According to psychologist Carol Gilligan, the ethics of care develops in three steps: first– a focus on caring for the self to ensure survival, second– the transitional phase where the criticism of selfishness and the understanding of connections between the self and others leads to a sense of responsibility, and third– the balance of the self with others and the relationships between them.

Constantly allowing others to invade your boundaries causes a corrosion of the self, eventually leading to burnout, apathy, and a loss of love within the self. Mechanical Engineering student and former student leader at UCF, Duc-Tanh Nguyen had experienced such apathy and loss of love over the course of his leadership. Only after stepping away and refocusing his notion of community was he able to overcome it. “A way to recover from apathy is to reprioritize your own objectives in life,” he says. “If you can move forward with the new goals for yourself, do so. By doing so, if the community that you struggled to engage with comes back in your life willingly, then it was a sign that you belonged there and you just needed time.”

In a conversation with bell hooks, her mentor Thich Nhat Hanh explains: “The reason we might lose [love] is because we are always looking outside of us. That is why we allow the love, the harmony, the mature understanding, to slip away from ourselves… that is why we have to go back to our community and renew it. The love will grow back.

“So the question is are we practicing loving ourselves? Because loving ourselves means loving our community… Anything you do for yourself, you do for society… anything you do for society, you do for yourself.” The search for community is an inherent part of personhood, where people suffer terribly in its absence.

The inverse is also true, a community is nonexistent without the people within, and cannot develop or progress without individual effort. It is imperative that intersectionality remains within the foundation of one’s activism and advocacy, as no person has a singular identity. Constructive criticism of a group, movement or ideology is another form of love, a call from within that indicates that there is always room for improvement and that there is someone willing to bring changes to light.

Think of yourself and the things that make up your identity and your place in society and its intersections. Think of those around you, the ways in which you are similar, the ways that you are different, what makes you stay where you are. In All About Love, hooks writes: “Loving friendships provide us with the joy of community in a relationship where we learn to process all our issues, to cope with differences and conflicts while staying connected.” It is only really with the help of others that you will find the meaning of community, be it your family, your friends, or people you choose to do work with. Only then will you be able to find meaning in what you do.

Life involves the constant learning and unlearning of things. This is why you must constantly go back and start from the ground up. Think of the little things, like love itself. I find love in actions like peeling oranges for someone despite not liking the taste of citrus. I find it in the color green, the color of the earth, and in how plants can grow despite the hostile environment around them. It’s in the way we learned that one of the first pieces of evidence of society was a healed femur, which showed us how humanity had made it this far not through survival of the fittest but through the caring of each other.

I even find love in my own grief– because what is grief, if not the perserverence of love despite it all?

ThisarticleisdedicatedtoAminahAhmedandTamimSyed. 18 | SPRING 2022

Silence to

From Volume

My curly hair journey...

Cries and brushes embraced the comb as it grasped the tight, tangled curls. The purple comb had become the enemy that never left and brought back cries every morning. Every day, I sat in front of the mirror dreading the ritual about to take place. As Mum tightened her grasp on the enemy in her hands, I tightened my fists. The initial entanglement began, then the next, and the next, while I held back the water puddling in my eyes. I trained my eyes on the blurry reflection of a girl with an untamed mane as the voices of “frizzy, puffy, junglee (animal-like)” screamed in my head. Stop, stop, stop, I yelled internally, but that didn’t stop the comb. Relief fell over my eyes as I saw Mum placing the comb on the white counter and then grabbing the blue bottle with a little palm tree on it. A familiar smell of coconut arose as Mum rubbed her fingers together. The thick, soothing oil is heavily lathered to tame the mane. Although my mane glistened with shine, worry swirled in my mind for the words I would hear today. I could just hear them say “Eww, why is your head so oily?” and “Why does your hair smell?” They made me hate the mornings. They made me cry. They made me hate my mane.

They soon became everyone. Everyone made comments about my mane and I stood in silence. The silence was covered in self-loathing and insecurities that grew deeper with every stinging comment. Some about the texture and some about the appearance. One voice whispered “not smooth and silky” and another whispered, “Do you even brush your hair?” I thought the torment ended with my classmates and friends. I was

quickly proven wrong when my aunt spoke in a proud and bold voice, “Why don’t you get your hair permanently straightened in India?” The idea of silky straight hair was so appealing. The voices would quiet down and my silence would clear. Fourteen-year-old me appreciated the idea. My mane would finally be tamed.

Silky and straight are words that embody the beauty standard of hair in the Asian community. The beauty industry pushes products and commercials that support the idea of shiny, pin-straight hair. Products such as Streax straightening cream (intense), Oxyglow Herbals Hair Straightener Cream, and Shiseido Professional Crystallizing Straightener encourage chemically destroying curly hair. They define flaws by promoting the ideal aspects of straight hair, instilling self-doubt in individuals with textured hair. Due to the strict standards, many people in the Asian community trade their voluminous curls for breakage and dryness. All in the hopes for the sleekness and shininess of straight hair. After building insecurities, the beauty industry feeds the consumers with products that will help them fit into the ideals.

I was a victim of the insecurities pushed forward by the beauty industry and the Asian community. Aisles and aisles in supermarkets were filled with products. The glistening bottles of sprays and serums were all promising solutions to my problem known as the mane. They promised to fulfill the insecurities that were drilled in me. I grabbed two bottles to compare which one held the most hope for my mane. I was enticed

by Krisha Patel design/ Dan Pham photography/ Lilly Dang & Amber Jani

SPRING 2022 | 19 This story is by THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA

“However, each of these Asian women decided to leave the straightener in the drawer. Now, their curly hair products soak in the spotlight.”

by the buzzwords like “anti-frizz”, “creates shine”, and “sculpts curls.”

My search for the perfect product started with a never-ending trial and error. A system that led to a cabinet filled with unused and unfinished products with the excuse that they will serve a purpose later in life. Only to recognize that fifteen-year-old me was scared to waste more money on products that guaranteed “antifrizz” and “sculpts curls”. I couldn’t afford to have healthy curls. I was tired and done.

However, the industry was not done with me. Now, there were large insecurities and small pockets. Guilt and sadness lingered with the insecurities that were developed by damaging comments. The temptation toward the glistening straightener on the marble counter grew as the voices in my head began to shout “You are ugly.” The idea of leaving the hidden walls wearing natural curls haunted me because of the backlash I would receive about my mane. Again, the mirror stood in the bathroom to mock the unwavering image. In the image, the messy and uneven textures are attentively focused on. The easiest and least expensive solution was to burn my curls in heat to obtain a silky and straight look. Laughter and taunts paused, replaced by compliments. Fifteenyear-old me started to glow as the darkness of self-loathing blew away. The wanted ideals and irreversible damage disguised the mane. The mask was compelling because it received love instead of hate.

Masking coils is a talent in the Bollywood industry. Actresses modeled silky, straight hair, upholding the beauty standards. The ideals of beauty were standardized where there was no room for natural curls to be shown proudly. Actress Taapsee Pannu was prohibited from movie roles because of her naturally

curly hair. A Hindustan article states that Pannu had to get her hair chemically straightened while growing up because she realized no Bollywood actress had similar features to her. She then initiated a movement where movies capture her curly hair. When I watched Pannu star in Badla, I was shocked to see her curly hair. The soft, bouncy coils framed her face as she expressed distress and happiness throughout the various scenes. My head spun in excitement. The representation came after sixteen years of growing up with the industry. I stopped taking my curls for granted because I saw that they can be styled to be elegant.

Similar to Pannu, Kangana Ranaut has inspired curly hairstyles by

a curly-haired role in the film, Queen, where the character glows up by straightening her hair. Curly hair is demonized in the industry. In the movie Sanam in Teri Kasam, there is a scene in which the hairstylist takes the actress’s hair out of the braid and it begins to expand in frizz around her head and shoulders. The actress’s face is in despair. The frizz, texture, and volume are soon lost after it is fried with a “magic tool.” As she turned toward the mirror, a smile grew on her face. The industry’s ability to manipulate the representation of curls encouraged desperation for straight hair.

Hopelessness stands amongst the numerous hair products for straight hair. Tons of information about styling straight hair is accessible through generations and online resources. Year after year, the Asian community leaves curly-haired individuals

generation Asian American with curly hair, I grew up with a lack of information about how to care for my curly hair. From primary school to middle school, my mother was

20 | SPRING 2022

lost on how to deal with my hair. We dug and dug through products of all promises. Nothing worked and I had no one to learn from. Until one day, I discovered a whole curly hair community on YouTube. All of my knowledge about maintaining and caring for curly hair comes from Black women. Unlike the Asian community, caring for curly hair is a long-standing tradition in the Black community. Hence, I started to value my curls by observing how Black women cared for their curls. I realized that the lack of education about curly hair leads to a lack of acknowledgement for curly hair.

Amongst the learning process, there have been other Asians who suffered through a similar journey. Various Asian women have written blogs to share their knowledge about curly hair. Kanya London discusses that the curly hair movement is always catered to White, Black, and Latin communities where Asians are left out of the conversation. Supermarkets create aisles filled with products catered to the Black community. Curly hair varies tremendously from texture to curl shape, requiring

However, each of these Asian women decided to leave the straightener. Rathod states: “While my mum and grandma treasured my long, healthy hair, it never really stood a chance to curl up at its length.” Curls fight to be in the spotlight but the glorified straight hair shields the curls from the light. Before, there was a desire for silky straight hair. However, each of these Asian women decided to leave the straightener in the drawer. Now, their curly hair products soak in the spotlight.

As the light shines upon the mirror, a reflection highlights the black, soaked ringlets. Now, the morning begins with a comb, leave-in-conditioner, and gel. The hums and beats in the back spark motivation to pick up the plastic strip with narrow teeth to thread my hair back, leaving it in a middle part. The unwavering tangles cry for attention as the beige cream paste is spread through the struggles, covering the unspoken damage. The curls grow as they are conditioned to move past the heat, leaving them to gleam in the sunshine. The conditioner and scrunches support the shining curls as they bounce in the joy that once was covered. Joy is held by the clear jelly that laminates the permanent coils. Once again, the mirror emphasizes the defined curls that seemingly lay

I gazed at the mirror, reflecting the strong

SPRING 2022 | 21

In Line and Back Again

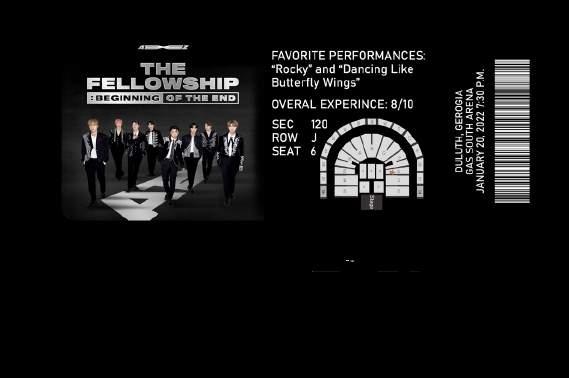

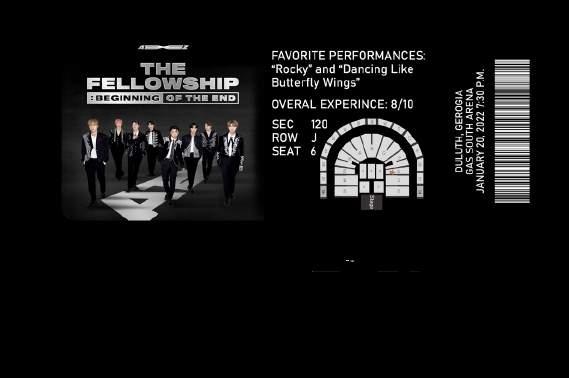

After over two-year break from concerts, K-pop acts are finally back on the road again. With many artists stopping in Georgia and Florida, this year, I made it my goal to try and go to as many K-pop concerts as possible. I know not everyone has this luxury, so I wanted to share my experiences with everyone, highlighting rthe ups and downs of each concert. Please note that while I love every artist I got to see, my reviews are a result of multiple factors, not just the artists’ performance alone.

It goes without saying that ATEEZ’s performance was beautiful and enthralling. ATEEZ’s facial expressions, powerful dances and vocals are on a completely different level live. “WONDERLAND (Symphony No.9 “From The Wonderland”)” had my jaw on the floor, frozen in place out of shock of how talented they truly are. Their stage presence held me captive from the beginning to the end; even in the songs where members just walked around, they demanded your attention with freestyle dances and big smiles. I think their graphics and lights complemented the songs well. The graphics did not draw attention away from the performers, but added to the atmosphere of each song; for example, the traditional Korean inspired graphics for “The Real.” Lighting wise, happy songs had bright warm lighting while dark intense songs had strobe lights and cooler colors; the lights matched each songs’ vibe. I do wish they would have connected the lightsticks through bluetooth so everything looked more cohesive. The hi-touch experience was limited due to COVID; members waved from behind a plastic divider, but fans were able to record hi-touch which was a plus. The tour merch could have been more exciting (and less expensive); if the merch had included tour dates it would have been better. The biggest negative of the night was finding out multiple fans knowingly went to the concert with COVID and some even attended hi-touch.

ATEEZ

by Liana Progar design/ Arianna Flores

22 | SPRING 2022

photos/Allison Kamla, Britney Dyer

BLITZERS

This was honestly one of the best shows I have been to ever. Despite not being even a year old, it felt like Blitzers performed with the experience of fourth-year idols. Blitzers gave it their all, singing and rapping their hearts out. For how labor intensive their choreography is, they still delivered beautiful and stable vocals. Even their light, fun performances left me happy and excited for more. There were only a couple hundred fans, but the smaller number made the show more intimate. The boys were able to focus on fanservice, and even played a mass game of Rock, Paper, Scissors with the crowd (I placed 6th and lost). For the group picture, one of the poses was with their hand signal. Blitzers took the time to sit down on the stage to teach people the hand

positions, they even went fan to fan confirming the hand signal was correct which was sweet of them. One thing I found rude was that some fans would not stop screaming during their ments. It got so loud that Chris, the only one fluent in English, had to start translating because the official translator couldn’t hear the boys. After the concert, one of the hi-touch participants was rumored to have COVID. Before starting hi-touch, the staff rapid tested the person which I admired. For hi-touch we actually got to shake hands with them and record!

SPRING 2022 | 23

photos/Allison Kamla, Liana Progar

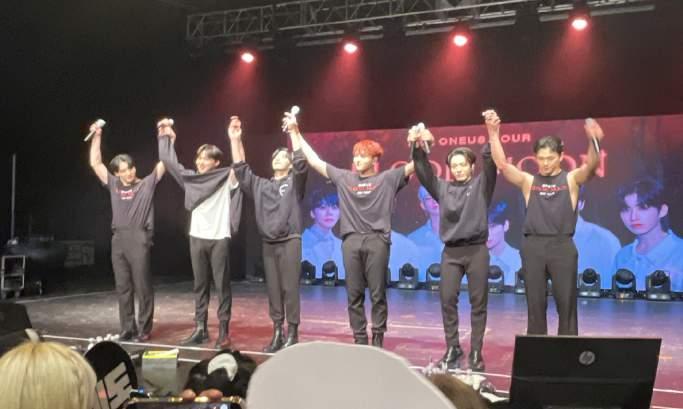

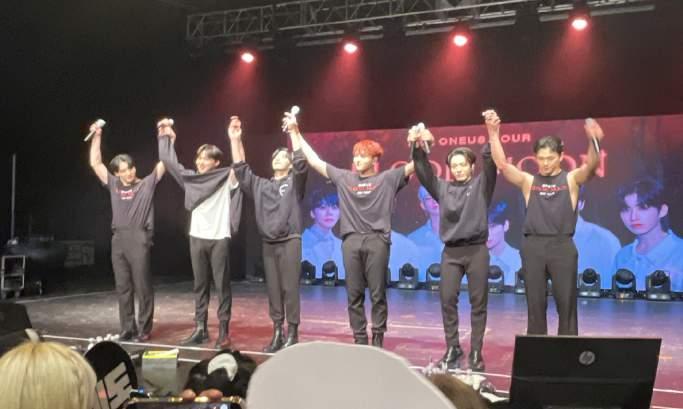

ONEUS

My friends and I got there super early and it was blazing hot. Fans were very nice and handed out free cold waters. The staff weren’t very organized, but the venue did require a mask and a negative rapid test or a vaccine card for entrance which was nice. Oneus are great performers and their vocals live are stunning. I was just standing there, no thoughts head full of amazing performers, during their first stage. I wish I could’ve seen more of the concert, but somehow the pit was packed enough and people shoved so much I ended up standing behind tall people. Being in the pit wasn’t great for this concert, we barely had room to move a single arm and really took away from the experience. I left the concert feeling like I just watched an online concert, for a majority of the concert I felt removed despite physically being present. For hi-touch, staff did not clarify which side we would be using to high five the boys with so those of us who only had one glove had to panic switch which hand it was on. Unfortunately, we were not allowed to record hi-touch. Oneus’ merch did include tour dates and were reasonably priced.

24 | SPRING 2022

Eric Nam

Having been to an Eric Nam concert before, I had high expectations walking into this concert. While this concert did not beat my first time seeing Eric, it came very close. Overall, the atmosphere of the concert was immaculate. Eric brought Audrey Mika as an opener and she really helped set the light hearted, fun tone for the night. It goes without saying that Eric’s crowd engagement was on point that night; he took the time to do song requests and sing happy birthday to over 14 people. Having recently become an independent artist, you could feel a change in Eric’s energy. He seems happier, freer now, which was reflected in the joy he brought the audience. To top it off, the setlist was well curated. It was fast paced but gave everyone a break when needed with slow songs. Eric also brought a live band which enhanced the songs and added to the excited atmosphere. Fans were super chill and for the most part did not push or try and cut in line. Some people did get unnecessarily in our personal space when they had room to not be right on top of us, but luckily after a little bit everyone settled down and spread out. Unfortunately, despite the crowd being on the shorter side, for most of the concert there was just a wall of arms and phones so I had to watch some parts of the show through someone’s phone.

photo/Britney Dyer

photo/Britney Dyer

SPRING 2022 | 25

Ocampos

26 | SPRING 2022

by Zohra Qazi photography/Reggie

design/Mayumi Sofia Porto

HORROR IS TERRIFYING, DISGUSTING, FRIGHTENING AND SCARY.

In the Western world, this fiction and cinematic genre has been known for its vampires, werewolves, dystopian societies, zombie apocalypses, and serial killers—ranging from the slashers to the survivals to the supernaturals.

In Asia, though, horror looks somewhat different. Due to the cultural, religious and societal differences, horror from countries like Japan and Indonesia have perfected the art of shocking and haunting their audiences—both at home and abroad.

Yet, with these horror movies, one fact remains clear: these stories, that frighten us and leave us feeling repulsed, are metaphors for our society. From the serial murders of 1960s America came the slashers horror like “Silence of the Lambs;” with the Cold War and the fears surrounding potential nuclear attacks came the space-themed horror and invaders like “It Came From Outer Space.” We also see religious and cultural folklore as a strong influence on creating new, demonic monsters like in Malaysia’s supernatural horror film “Roh.”

In this sense, our present shapes our horrors, both real and fictional. Our culture, our society and our politics all combine together in horror, reflecting back our greatest fears in the shape of ghostly possessions, costumed serial killers or dangerous aliens. What makes our daily reality also makes our nightmares.

Whatever monster creeps around our darkened corners, we know, somehow, it starts with us.

SPRING 2022 | 27

The “_______” Guy

Students Use On-Campus Asian Organizations to Refine Their Appreciation of Asian Culture

If you were to attend a general body meeting hosted by the University of Central Florida’s Asian Student Association (ASA), you would inevitably come across self-proclaimed, “white guy,” junior Kyle Smith. In an organization known for its community of Asian American students, Smith stands out. Such a blunt nickname invites laughter and light teasing, which he gladly accepts and even encourages, through his frequent use of the phrase in officer introductions, and tabling events.

“I genuinely think it is funny. I can take a little beating from it; sometimes I am the only white guy,” Smith said. “I feel like [for] people who want to experience the culture, sometimes it is easier [if] I am the white guy.”

As the fundraising chair for ASA, Smith has a more exaggerated role in club promotion. He thinks of the combination of his race and his position as a positive, inviting signal to prospective non-Asian members, especially those who are concerned about fitting in.

“I liked seeing Kyle, as well as other non-Asian members take part in the club. To me, it showed that the Asian members were open to sharing their space with their non-Asian friends,” junior Kayla Andries said.

Though she is Jamaican-Guyanese, Andries started practicing her Mandarin in third grade and continued to learn about Asian culture from her friends in high school. She was interested in furthering her ASA membership into college and has found its members to be very encouraging. Asian culture is difficult to precisely describe, but it is safe to say that Asian pop culture is widely accepted. The likes of anime and K-Ppop are widely popular in the West, with passionate fans from both camps eager to share with anyone who will listen.

Still, this is not what many of the Asian organizations, such as ASA and the Asian Pacific American Coalition (APAC), are about. Andries is aware of the difference between culture and pop culture; such consciousness does cause her to hesitate to participate.

“As an African American, I have felt alone at times when my friends aren’t around. As much as I like the opportunity to get to know new people, I’m reluctant to introduce myself because I fear some people will think that my interest in Asian culture is superficial,” Andries said. Such reluctance is not unique to Andries.

Senior Romel Scott felt similar, but instead, pushed himself to be more active. As an African American brother in Delta Epsilon Psi, a South-Asian interest fraternity, Scott did have some reservations about engaging in Asian organizations, but was interested in exploring outside of his own culture.