At the movies • Brigham Young on the big screen.

> Page 3

Home front • Families are forever — different.

> Page 5

Monson • What the church gets right.

> Page 10

Dollar signs • The church’s bottom line.

> Page 13

At the movies • Brigham Young on the big screen.

> Page 3

Home front • Families are forever — different.

> Page 5

Monson • What the church gets right.

> Page 10

Dollar signs • The church’s bottom line.

> Page 13

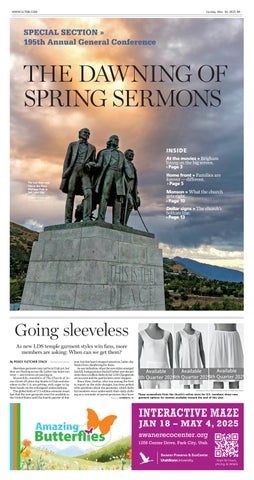

As new LDS temple garment styles win fans, more members are asking: When can we get them?

By PEGGY FLETCHER STACK | The Salt Lake Tribune

Sleeveless garments may not be in Utah yet, but they are floating across the Latter-day Saint universe — and reviews are pouring in.

Meanwhile, members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Utah and elsewhere in the U.S. are getting, well, eager to lay their hands on the redesigned underclothing.

The global faith of 17.2 million remains steadfast that the new garments won’t be available in the United States until the fourth quarter of this year, but that hasn’t stopped American Latter-day Saints from clambering for them.

As one indication, when the new styles emerged last fall, Instagrammer Rachel Gerber says she got more than a million clicks on her LDS Changemakers account and the queries have never stopped. Since then, Gerber, who was among the first to report on the style changes, has been pelted with questions about the garments, which faithful members wear underneath their daily clothing as a reminder of sacred promises they have

made to God.

Can women really wear tank tops over the new sleeveless styles, unlike the current versions? Will the new slip (or halfslip) model allow women to wear their own nonsacred briefs? Will the fabrics be lighter for those living in hotter climates?

And can the revised styles finally put an end to the judging of fellow members over whether they are — or are not — following the prescribed rules? Will it end the condemnation of so-called porn shoulders and the mantra on modesty?

The church has posted images of the garments — four new styles for women and two for men — but they are already for sale in many countries, including Kenya, South Korea, the Philippines and Japan, to name a few.

They will be available in the United Kingdom and New Zealand midyear, Gerber says she has learned.

When the redesigns first appeared online, some women were skeptical that they would make much of a difference, she says, but now that some have actually tried them on, it turns out, a few inches does alter the look and feel.

Some conservative Latter-day Saints say they feel “betrayed” by the change, Gerber says, and insist they will stick with the current styles — which will remain available — as “a badge of righteousness.”

Most women, though, are salivating at the chance to try the new designs, Gerber says. She knows of brides-to-be who have paid friends in other countries to pick up pairs of the new garments so they could wear sleeveless wedding dresses.

And when Utah influencer Vika Froelich, who got a pair from relatives in Korea, volunteered on social media to buy a few for others, she says she got more than 4,000 direct messages taking her up on it.

She had to politely pull back the offer.

Saint women, she says in an interview, “so it wouldn’t be such a shock when they see women coming to church in sleeveless dresses and wonder if they were wearing their garments.”

She hoped “to open the door before they are released here,” she says, “to get people thinking.”

And when Froelich, whose Instagram account specializes in modest fashion, put them on, she says, it was even a “shock” to her. She discovered that traditional tank tops, indeed, will now be “garment-friendly.”

The open-sleeve garment was 2 inches lower in the armpits and 2 inches shorter at the waist, Froelich, who is 5-foot-4 and weighs 110 pounds, says in the video, though she knows it may fit differently on other women.

“I can’t wait till everyone gets these garments because they really are so amazing,” she says, “and I’m so happy with all of the changes.”

Froelich recently posted a video of her in a sleeveless dress entering the meetinghouse. “The anxious feeling you get when you walk into church wearing the new sleeveless garments,” the clip states. “Wish me luck.”

Jaime Perry, a Latter-day Saint in Guam, says the neckline was “too high” on her, which means she can’t wear the new garments with many of her dresses.

She also finds the material, which contains spandex, “too tight,” Perry says in an interview. “I don’t think [the new style] will be a viable option for many in my country.”

Her fiance, William Lyle Stamps, an American Latter-day Saint who works for Guam’s attorney general, offers his own review of the new men’s garments.

He was “surprised,” he says, “that the hot-weather guy bottoms basically imitated the woman’s top of the last five to 10 years … It had a mesh strip to increase breathability.”

And the sleeveless top means “exposed underarms,” Stamps says. “I felt like a teenager again, oddly.”

Still, Stamps prefers the former style.

“They already work well for hot weather,” he says. “I’ve worn that for 30 years … except for when I had to wear military garments, which only had the cotton.”

Stamps notes that there was a male bottom “support” version.

“It worked as intended,” he says, “but I don’t recommend long-term wear. It’s to wear for the gym or sports activity, then change.”

For women, though, such a version is a long-term concern.

That time of the month

For years, Latter-day Saint women have endured the fabric and fit of garment bottoms during bladder leakage, staining and monthly menstruation.

In her massive survey on women’s attitudes toward garments, researcher Larissa Kindred says complaints about coping with their periods topped the list. Some 62% of traditionally devout women said that wearing garments was “difficult to navigate” during menstruation.

“When I first started wearing them, it took me about two years until I found the best period product to use with the garments,” a respondent wrote. “I preferred pads, and it is hard to find pads for ‘granny-style pants.’ They are either too small, the bottoms would not be easily moved, causing the pad to misalign, or I would end up sticking three to four pads on at a time.”

Adapting garment bottoms for periods was among the revisions Colorado L atter-day Saint Afton Southam Parker

suggested to a church committee. It also was among the reasons she proposed a “slip” version, so that women could choose what to wear beneath it.

“There really needs to be elastic to be able to hold the wings from a pad in the crotch area not farther down the leg. That was an important part of the feminine products,” she told church officials, “and even without the wings, just having it cradled in the regular crotch area of underwear was so much better than shorts/boxer-style.”

Apparently, the church took those suggestions to heart. The faith’s General Handbook now says women can choose how and when to use their own underwear (bras and panties) with the sacred undergarment.

“It is a matter of personal preference,” it states, “whether other undergarments are worn over or under the temple garment.”

There also are plans for women’s bottoms that incorporate more layers of fabric, says Gerber, who says she has seen prototypes.

Whatever the design, Parker is thrilled to see church leaders address this issue.

“I just firmly believe that women need to choose their own underwear to address these very personal issues,” she says, “because it’s hard to feel anything spiritual or uplifting when your body has physical issues with the very thing that you’re supposed to feel special and sacred about.”

Out with ‘porn shoulders’

Whether believers like the new designs and fabric, there is no question that the modesty defense of the old style is gone or at least fading. And some longtime members feel betrayed by that.

“I was taught to hate my shoulders and my body because of the male gaze and their purity,” a commenter wrote on Froelich’s post. “To see the church now say tank tops are fine, that doesn’t undo the trauma and shame I was taught to feel.”

Some women are “grappling with how these changes affect long-held teachings about modesty,” writes Utahn Carol Rice, director of communications for Latter-day Saint-focused Public Square Magazine.

The redesign, she argues, “comes with an opportunity to revisit personal understanding of why one wears the garment and what it truly represents, inviting a deeper understanding of modesty and sacred identity.”

To Froelich, it’s an important messaging shift.

The Instagrammer grew up in Tremonton, an “extreme modesty culture” where teenage girls had to kneel to ensure their shorts touched the ground. She served an 18-month mission for the church, with its strict dress code. She internalized General Conference messages about “covering shoulders” and about the “tie between modesty and garments.”

Now Froelich believes garments have “nothing to do with modesty,” she says, “and everything to do with covenants.”

Modesty isn’t about “what we are wearing. It’s about who you are on the inside.” The young mom is delighted by the change, she says. It will get believers “to focus on the right things.”

The pioneer church leader has been shown as a master manipulator, a film historian says, except in a classic 1940 Western.

By SEAN P. MEANS

The Salt Lake Tribune

When Netflix debuted its “American Primeval” miniseries earlier this year, viewers saw a brutal depiction of the American West — particularly the Mountain Meadows Massacre in 1857, when more than 100 members of a California-bound wagon train were slaughtered in southern Utah.

For James V. D’Arc, the depiction of the massacre was nothing surprising.

“Not much has changed in the cinematic representation of Brigham Young or the Mountain Meadows Massacre,” D’Arc, a longtime film historian and emeritus curator of the motion picture archive at Brigham Young University, said in an interview.

The scenes in “American Primeval” echoed similar moments in “September Dawn,” a 2007 movie that plowed the same narrative ground — and both, D’Arc said, got the history and even the geography of the place wrong.

“Audiences know that they have to participate in the willing suspension of disbelief in ‘American Primeval,’” D’Arc said, but “they have to be suspended so long that they might die from the noose.”

Over more than a century of moviemaking, D’Arc said, the depiction of Brigham Young — the man who led the Latter-day Saint settlers to the Salt Lake Valley in 1847 and served as Utah’s first territorial governor — has been largely negative. Either Young was shown as a villain or the production was generally lackluster.

There is one notable exception,

a movie that D’Arc called a “bright ray of relative sunlight”: The 1940 Western “Brigham Young,” with Dean Jagger in the dynamic title role.

Here are D’Arc’s thoughts on six portrayals of Young in movies and on TV, spanning from silent films to the streaming era:

Richard Cummings, ’A Mormon Maid’ (1917)

The first known cinematic depiction of Young, D’Arc said, was for this silent feature in which a scout wants to marry a young woman whose parents lead a wagon train headed to Salt lake City. When they arrive in Utah, however, the leader of the church tells the woman’s parents that they must practice plural marriage, which they don’t want to do.

The leader is never identified as Young but is called “The Lion of the Lord.” He’s played by Richard Cummings in what D’Arc called “pretty much a 19th-century depiction of Brigham Young — very authoritative, very demanding and everyone obeying his decrees.”

Being a silent movie, there is not much to say about Cummings’ performance, D’Arc said, as “you’re basically a slave to inter-title descriptions and visuals of his summary pronouncements.”

The actor playing the scout, Frank Borzage, was a Salt Lake City native who shifted from acting to directing and won two Oscars in the early talkies era.

“A Mormon Maid” was one of many silent movies produced essentially as propaganda against The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. One of the few that has survived is “Trapped by the Mormons,” a 1922 melodrama about a missionary with the power to mesmerize innocent young women into joining the faith.

Dean Jagger, ‘Brigham Young’ (1940)

Tyrone Power and Linda Darnell are the credited leads, playing a Latter-day Saint scout and an outsider who fall in love on the trail between Illinois and Utah in the 1840s. What sets apart director Henry Hathaway’s historic melodrama is Jagger’s performance as Young, speaking eloquently as he leads his people away from per

secution while quietly confiding his doubts to his rock-steady wife, Mary Ann, played by Mary Astor. (Mary Ann is the only one of Young’s wives mentioned in the movie, which generally avoided the topic of polygamy.)

“His portrayal was one of great force and vigor, and sometimes stubbornness that the historical Brigham Young has been characterized by,” D’Arc said. “But there was also a tender side to him, and he was plagued by doubts that he couldn’t talk to God.”

Heber J. Grant, then the president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, took a personal interest in the movie’s development, D’Arc said. “He decided, ‘Let’s be pro-active. Let’s work with the studio to see if we can give assistance, especially from our church archives, to whatever factual research they want to undergo for this screenplay.’”

Grant dispatched one of the church’s apostles, John A. Widtsoe, to take novelist Louis Bromfield, who worked for 20th Century Fox and received the original story credit on the film, on a twoweek automobile tour of Utah, ending with dinner at the Lion House (Young’s family home) in downtown Salt Lake City. D’Arc noted Grant also sent one of Young’s descendants, Levi Edgar Young, to the set.

Levi watched Jagger shoot an early scene in which Brigham Young stands in court to defend

the church’s founder, Joseph Smith (played by Vincent Price). The scene was fictitious but was added by screenwriter Lamar Trotti, D’Arc said, “as a way to bring together all of the elements that explain the persecution and the injustices the Latter-day Saints were undergoing.”

The scene worked on Levi, D’Arc said. “When I closed my eyes,” Levi said, “the inflection of Dean Jagger’s voice made me think of the Brigham Young I knew as a little boy.”

The movie was shot primarily in California, D’Arc said, but a key scene was filmed in Utah: The devouring of crickets by seagulls. The gulls were filmed at Utah Lake, D’Arc said, and the visual effect of the crickets was added later.

A decade after “Brigham Young” was released, Jagger won an Academy Award for his supporting performance in the World War II aviation drama “Twelve O’Clock High.” Holiday movie watchers also know him as Maj. Gen. Thomas Waverly, the retired military man who gets helped out by Bing Crosby and Danny Kaye in “White Christmas” (1954). According to D’Arc and

historian Davis Bitton, Jagger late in life became a Latter-day Saint. Maurice Grandmaison, ‘Brigham’ (1977)

The makers of this low-budget biographical drama “claimed that they did research in the church archives,” D’Arc said, “and that this was going to be a friendly film to the church.” Unfortunately, he added, it was “poorly written, poorly photographed and unfortunately cast. Maurice Grandmaison [as Young] had no presence at all on the screen.” (Former Utah resident Richard Moll played Joseph Smith, years before becoming famous as the bailiff Bull on the sitcom “Night Court.”)

Outside of the “Mormon corridor” — Utah, Idaho and Arizona — and a few theaters in California, nobody saw it, D’Arc said.

Charlton Heston, The Avenging Angel’ (1995)

Tom Berenger played the title role in this TV movie for TNT, a Please seeB BRIGHAM YOUNG, NEXT PAGE

Stellar convert hobnobbed with Hollywood actors, and played a starring role in helping to establish and build the church in Spain.

By MARK EDDINGTON | The Salt Lake Tribune

Long before “The Best Two Years,” “The Singles Ward” and “Mobsters and Mormons” graced movie screens, Jose Maria Oliveira was exposing audiences to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

But rather than a lighthearted focus on quirky Latter-day Saint behavior, this largely forgotten Spanish filmmaker’s creations were laced with murder, adultery and heavy church doctrines, including the fate of unrepentant sinners in the afterlife.

Indeed, Oliveira’s art house “horror” flicks “Beware of Darkness” (1973) and “The Dead, the Devil and the Flesh” (1974) played in theaters across Spain, earning critical acclaim and respectable box office returns.

Moreover, as director of the William Morris Agency in Spain in the 1960s, Oliveira, a Latter-day Saint convert, hobnobbed with Hollywood stars. Later, he helped cast major American films.

Today, Oliveira’s movie work is remembered mainly by Latter-day Saint cinephiles, according to Brigham Young University film archivist Ben Harry, who digitally restored both of Oliveira’s movies and showcased them in special screenings at the churchowned school in 2022.

“There were rumors … that there were these Spanish horror movies from the 1970s,” Harry said. “So people had heard about them, but very few had seen them.”

Like a ‘rock star’

Oliveira, who helped the U.S.-born religion take root and blossom in Spain, is better known nowadays for his service to the faith than his career in film.

After his baptism in 1966, Oliveira helped the church win formal recognition in Spain and served, at varying times, as the country’s first Spanish branch president, district president, stake president and stake patriarch.

“He was like a rock star,” recalled Cedar Hills resident Paul Laemmlen, who served a church mission to Madrid in the late ‘70s. “He was a leader everyone looked up to and was kind of an emissary between the Salt Lake church and the Spanish people. Gringo missionaries serving in Spain adored him.”

For his part, Oliveira, who now lives in the same Salt Lake City apartment he and his wife, Patricia, moved to in 1989, would rather talk about his role building the church than revel in his personal or professional accomplishments.

Born in Huelva, where Christopher Columbus departed in 1492 to sail to the New World, Oliveira moved with his family to Madrid after the Spanish Civil War. Upon earning a law degree from the University of Madrid, he spent a year in London perfecting his English. After his return, he went to work as legal counsel for the William Morris Agency in Spain.

Part of his duties was to provide services to actors contracted with Hollywood studios to make movies in Spain. One of them was

Above • Jose Oliveira speaks at a screening of his movie at BYU in fall 2022. Right • A frame of Jose Oliveira’s 1973 movie, “Beware of Darkness.” It shows Patricia Wright (her maiden name and stage name; she is Oliveira’s wife) conducting a seance

British star David Niven.

Now 91, Oliveira still vividly recalls the day he was instructed to pick up Niven at the airport and keep him entertained in Madrid all day until the actor could board a flight that night for Morocco.

Carousing with celebrities, converting to Mormonism

True to his task, Oliveira took Niven to a popular bar. There, the actor ran into two close friends: Luis Miguel Dominguín, a famous Spanish bullfighter who once had an affair with Ava Gardner while she was still married to Frank Sinatra, and Cristóbal Martínez-Bordiú y Ortega, a heart surgeon and 10th Marquess of Villaverde.

“We spent the rest of the day with them at the heart surgeon’s home drinking and talking … and then they drove us to the airport late at night,” said Oliveira, who was not yet a Latter-day Saint. “David was worried about missing his flight. And [the Marquess] said, ‘Don’t worry about missing the plane because I will stop the flight. I’m Franco’s son-in-law’” — referring to Spanish dictator Francisco Franco.

Oliveira’s interest in Mormonism was sparked in 1959 after he began dating Patricia Wright, a Utahn who was living in Madrid with her brother, David, who worked at the U.S. Embassy.

At first, Oliveira was hardly impressed by the religion.

bodyguard assigned to protect Latter-day Saint leaders — but it was Charlton Heston, a legend for roles in such biblical epics as “The Ten Commandments” and “Ben-Hur,” who took the juicy role of Young. Heston “really enjoyed playing Brigham Young,” said D’Arc, who interviewed the actor in 1999 for a book. “He was terrific in it. That nicely cropped beard, the square jaw that he had. He just exuded Moses or El Cid, and every other powerful leader that he had played in the past. He brought it all to bear on his portrayal of Brigham Young.”

Terence Stamp, ‘September Dawn’ (2007)

British star Terence Stamp, whose long career has included the title role in the naval drama “Billy Budd” (1962) and playing General Zod in “Superman” (1978) and “Superman II” (1980), played Young as a stereotypical bad guy. “When you have Brigham Young making such statements

“When I read the pamphlet of [church founder] Joseph Smith, I told her that we have visions like that by the hundreds in the Catholic Church,” he recalled in an interview with President R. Raymond Barnes, who opened the first Latter-day Saint mission in Spain in 1970.

That changed several years later, Oliveira said, when he read “The First 2,000 Years” by W. Cleon Skousen and the “Articles of Faith” by apostle James E. Talmage. Fascinated by the church’s belief in a preexistence, he attended a Latter-day Saint branch, or congregation, for U.S. military members in Madrid and was taken by the humility of the worshippers.

After further study, Oliveira was baptized in March 1966 in Bordeaux, France, because there was no religious freedom in Spain for non-Catholic churches. Two months later, Jose and Patricia married. The only Spaniard in the American branch, Oliveira soon began teaching a Sunday school class in Spanish.

Oliveira then invited his mother and other relatives to attend the class, who in turn invited their friends. After going nearly a decade without Spanish converts, the branch suddenly had 25 of them. A few months later, in 1967, the Spanish Parliament enacted a law that granted religious freedom to non-Catholic faiths.

There was, however, a catch. For a church to be recognized, it had to already be established with a Spanish congregation. Fortuitously, the influx of Spanish converts had led to the formation of an independent branch for the new members, enabling the Utah-based church to apply for formal recognition, which the government granted in 1968.

“The Lord waited,” Oliveira stated in his earlier interview, “until a few months before the law of freedom [was passed] to form this group of Spanish Mormons … so we [would] have the right to apply.”

‘Thou shalt not lie’

Oliveira recounted another significant moment in the church’s evolution in Spain about the time he accompanied apostle Marion G. Romney to meet with the government official in charge of non-Catholic religions.

Oliveira, who was acting as translator, cautioned Romney not to tell the official about the faith’s plan to send missionaries, saying “we can do it, but we can’t talk about it.” When the apostle insisted on full disclosure, Oliveira countered with “we have to be wise as a serpent.”

as ‘I am the voice of God, and anyone who doesn’t accept that, I will hew down,’” D’Arc said, “well, that pretty much says it all about his depiction of Young.”

The movie portrays the Mountain Meadows Massacre, when scores of Arkansas emigrants en route to California were gunned down by Latter-day Saint militiamen in southwestern Utah. Historians have long debated whether Young knew about the massacre in advance, but the movie’s screenwriters, Christopher Cain (who directed) and Carole Whang Schutter, show no doubt in their mind that Young ordered the killings.

As Stamp plays him, D’Arc said, Young “comes across as morose, very soft-spoken, unless he’s delivering his revelations and pronouncements.”

Kim Coates, ‘American Primeval’ (2025)

Coates’ performance matches the general tone of the Netflix miniseries, D’Arc said. “The entire series comes across as dark visually, dark morally and dark musically. … There is no rhythm, there is no break from this morose, dark tone.” Coates portrays Young as “very manipulative,” D’Arc said. “He’s very shrewd. He knows how to handle people, both

Romney’s rejoinder: “Thou shalt not lie.”

So what went down? Here’s how Oliveira explained it at a Utah gala celebrating the 50th anniversary of opening Spain to Latter-day Saint missionary work:

“When the official asked, ‘What are the plans of your church for Spain?’ I said to President Romney, ‘He asked what are the church’s plans. ….’ [Romney] said, ‘Well, you know, tell him.’ So I said, ‘Our plan is to build a chapel.’ I did not mention the missionaries.”

“We converts do strange things,” Oliveira quipped at the gala.

Today, Spain has about 66,000 members, more than 130 congregations and one temple (with plans for a second).

Old movies get a new look

While the church has grown exponentially, Oliveira’s two horror films seemed destined for obscurity — despite the fact that critics named “The Dead, the Devil and the Flesh” the country’s top movie for spiritual and artistic values in 1974 and it was selected for the Chicago Film Festival.

Harry, the BYU film archivist, said Oliveira told him that he screened the movie at a Salt Lake City theater after moving to Utah and invited Latter-day Saints from his congregation to attend.

“He said church members who came left after 10 minutes because they were expecting to see a family movie,” Harry recalled. “They were expecting something like “Where the Red Fern Grows,” and they were seeing people [in the movie] with sex and heroin addictions … and they were murdering each other. So they walked out.”

Conversely, he added, foreign film aficionados were put off by the obvious nods to church doctrine and began shaking their heads before they, too, headed for the exits. Within 20 minutes, Harry said, Oliveira was sitting alone in the theater.

Impressed by the success of “The Exorcist,” Oliveira wrote, directed and produced both movies in the mid-1970s and cast his wife and Spanish actors. Besides seeking commercial success, the filmmaker wanted to subtly introduce audiences to Mormonism’s plan of salvation.

Without giving away too much of the plot, Harry said “Beware of Darkness” deals with a love triangle gone murderously wrong.

“All three of them are dead,” Harry said, “and they wake up in the spirit world trying to figure out what happened.”

Latter-day Saints believe the souls of people who die reside in a spirit world — the righteous in paradise, the wicked in a spirit prison — until the coming resurrection and judgment day.

“The Dead, the Devil and the Flesh” also involves murder and deals with tortured souls in the afterlife. It features Satan, two Latter-day Saint missionaries and a spirit guide named Alma, who tells one of the anguished spirits to talk to the proselytizers.

“It’s about a husband and a wife,” Oliveira told The Salt Lake Tribune. “She is an adulterous woman who gets killed and goes to the spirit world, and her husband goes there to rescue her. It is based on a Greek tragedy.”

Harry said the film also features an evil Korihor, a nod to an anti-Christ in the church’s signature scripture, the Book of Mormon, who urges the characters to fulfill their physical appetites they are unable to satisfy as spirits.

Unlike Oliveira’s fellow members and the film fans at the Utah debut years before, the enthusiastic cinephiles who gathered at BYU in 2022 to watch the movies ate them up, according to Harry, who hosted the screenings.

“Everyone found them fascinating because the Mormon angle in the movies really brings them alive,” Harry said. “We have never seen anything like them. Nobody from our [Latter-day Saint] community has ever made movies like this.”

Oliveira enjoys the recognition but said he prefers to bask in the glow of the restored gospel. He now lives alone (Patricia died five years ago). Of all of his life’s roles, he gives top billing to his church service. He doesn’t foresee that changing in his next life.

“My plan for the future is in the next world because I’m going there soon,” he joked at the 50th anniversary gala. “... I love to preach the gospel, and I’m thinking about what I am going to preach to the dead people there.”

If variety is the spice of life, then even LDS families are well seasoned

There’s a common misconception outside of the Jello Belt that all Latter-day S aints are roughly the same. That, as a whole, the religion is packed with a mass of homogenous doe-eyed Osmonds who have never tasted anything spicier than a banana. It may be true that if you put a thousand members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in a room together, you’d see some patterns (and a lot of filler and Botox), but the levels and ways in which one’s devoutness manifests can vary pretty drastically.

These variations in gospel commitment probably don’t seem like much to those on the outside, but for anyone who has ever spent any significant amount of time as a citizen of Zion, the differences are stark.

As a child, if I ever found out a friend of mine was permitted to do something that was forbidden in my home, like play sports on Sundays or listen to explicit music, I would complain to my parents about this. They’d usually respond by saying something like, “Well, that’s how they do things at their house, and this is how we do things at ours.” There was no judgment in it. Just a simple acknowledgment that every family is different and sometimes ours

was just more lame than someone else’s.

I like to describe my own Latter-day Saint upbringing and family as the kind that almost never actually did Family Home Evening, but we also were the kind that felt supremely guilty about that. We were the type who drank caffeinated sodas but never turned down a church calling. We didn’t go shopping on Sundays, but we also didn’t attend church while on vacation. We weren’t like the family down the street who got dressed up to watch General Conference from the living room and went to Nauvoo and Kirtland for every family trip. But we also weren’t like that other (wicked) family who sometimes went boating on Sundays and let the kids watch “The Simpsons.”

Quick note: The inconsistency in my parents’ rules around which television programs were prohibited during my childhood should honestly be studied. If a character of an animated TV

show said “damn” one time, it was forever banned in our home. But we also regularly watched gritty prime-time procedurals as a family without batting an eye. When I was 7, my mother announced one day we were no longer allowed to watch “Care Bears,” an animated television program for toddlers, citing some vague content-based reason. A few years ago, I asked her if she remembered what she found so morally objectionable about “Care Bears,” and she responded in a tone like she was finally ready to let me in on a family secret. “Oh, honey, I just couldn’t handle one more second of that obnoxious theme song.”

Ward talent shows? Nah.

Mine is a full-tithe paying sort of family. Well, excluding me. When The Salt Lake Tribune showers me with the outrageous sums of money I get for writing these columns, I immediately spend it all on babes and booze

without even considering setting aside 10% for the Lord.

Mine is a family that goes to ward activities and stays after to help clean up, but not the type to volunteer for the choir or perform in the ward talent show. When I stopped going to church a decade ago, my membership records somehow got transferred to my childhood ward, so I started getting a lot of ward emails asking me to come in for tithing settlement or some other thing. I was finally dropped from the email distribution list when the ward activities committee sent around a Google document asking people to sign up for the talent show and I booked my 70-year-old parents to do comedy magic in drag. (My parents and I have never once discussed this incident, but these people raised me to be this way so I can only assume they thought it was funny.)

Even in my extended family, there were substantial variations in how we practiced the religion. I experienced my own personal hell when I was 10 and was sent off to spend the weekend with my cousins who were the 6 a.m. daily-scripture-study type of family. After sitting through three hours of church that Sunday, I was informed that part of keeping the S abbath holy in their house included wearing our ties for the rest of the day. We also weren’t allowed to watch TV, besides “Saturday’s Warrior” and old VHS tapes of past General Conferences. I hugged my parents extra hard when I next saw them. This was around the time someone at church told my dad if he didn’t shave his beard, he would never be called as bishop. My dad responded “promise?” (He still has never been a bishop.)

Looking back, I’m not sure as a child I really knew what to make of the fact that a shared religion could produce such different rules for different people. Was my family made up of godless heathens or were we too buttoned-up or were we, perhaps, the perfect Goldilocks “just right” kind of Latter-day Saints? That’s not a question anyone can really answer, even though there are certainly people reading this who already have.

Last Easter, my in-laws flew in from Portland, Oregon, for a weekend visit. My husband and I took them to my parents’ house for a large family dinner with all my siblings and their children. After dinner, my dad read several New Testament passages and then led the group in a religious discussion about the meaning of the holiday. When we returned to my house after the dinner, we opened a bottle of wine and sat in my living room, where my husband’s nonreligious parents commented that they had never really participated in a religious Easter celebration like that, asking me if that w as a common occurrence with my family. Warm memories from my childhood of singing carols at Christmas and attending ward activities flashed through my mind. Family prayers where my dad would take the opportunity to reference each of his children individually and tell God t he specific reasons my parents were so proud of us. Quiet Sundays my family would spend together, playing card games after church and declining invitations from friends to go out and play. There was the boring stuff, too, and the aspects of the faith that are the reason it’s no longer mine. But when it comes to my kind of Latter-day Saint family, it’s the happy stuff I most remember. I must acknowledge, even though I no longer practice the faith, I have a lot of nostalgia for some of those times. Certainly not enough nostalgia to introduce these traditions in my home, but nostalgia even still. I sipped my wine, thinking of my parents, and told my in-laws, “Well, that’s how they do things at their house, and this is how we do things at ours.”

Eli McCann is an attorney, writer and podcaster in Salt Lake City, where he lives with his husband, new child and their two naughty (yet worshipped) dogs. You can find Eli on X, formerly known as Twitter, at @EliMcCann or at his personal website, www. itjustgetsstranger.com , where he tries to keep the swearing to a minimum so as not to upset his mother.

Aquestion that may seem absurd at first merits further contemplation: Could missionaries for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints help save the Catholic monastic movement in the United States?

I have great affection for monks. Their recent decline in numbers saddens me. I explain why in my 2021 memoir, “Monastery Mornings: My Unusual Boyhood Among the Saints and Monks,” about growing up at an old Trappist monastery in Huntsville.

Having lived in Utah for six decades, I also know that a Latter-day Saint missionary is monklike. A mission involves community living, lots of prayer, and stepping away from “normal” life. Years ago, Latter-day Saint men often prepared for missions with weekend retreats at the Huntsville monastery. My friend, former Church Historian LeGrand R . Curtis Jr., walked the peaceful grounds with me just a few months before his own second mission, in Rome.

In many ways, the Latter-day Saint missionary system is an exemplar for us Catholics. At least one other blogger shares my holy envy for the program.

The writer said he’d like to ask Pope Francis this question: “How different do you think the world would be if every Catholic young person aspired to serve a two-year mission like Mormon young people do?”

A call to service

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops should create a national service program that — among other things — would bring young Catholics into close contact with monks. My friend Bill White gets the credit for this great idea.

Bill — a fellow lawyer and friend of the Utah monks — served a Latter-day Saint mission in California. While he established the conservation easement that saved the monks’ Ogden Valley farmland, Bill also saw that the abbey had struggled to show young people how a monk lives a wonderful life.

He has told me, and several monastic leaders, that if young Catholic missionaries were assigned to do service work for a year or two at monasteries, not only would it help aging monks, but it also likely would call some of those young folks to monastic life. Bill is on to something.

Young Catholics are generous with their time. My children performed hundreds of service hours for worthy nonprofit groups while

attending Utah’s Catholic schools. Catholics do have mission programs, such as the Jesuit Volunteer Corps and FOCUS (Fellowship of Catholic University Students) missionaries. Unfortunately, not many young Catholics join them, and they don’t really help monasteries.

Latter-day Saints could teach Catholics how to organize and operate a nationwide mission program with widespread participation. Instead of a geographic focus, however, a national Catholic missionary program could zero in on meeting various human needs.

There could be a hunger track for working at inner-city soup kitchens, such as St. Vincent de Paul Dining Hall in Salt Lake City. Other missionaries could help with refugee resettlement at Catholic Community Services in Utah.

And some young Catholic missionaries could be assigned to help aging monks and nuns at their monasteries. That assignment might foster the same type of fascinating intergenerational dialogue I watched recently when Utah’s old Trappist monks met some millennials 60 or 70 years younger than them.

After the Huntsville monastery closed in 2017, the surviving monks (in their 80s and 90s) moved to a retirement community in Salt Lake City. Sometimes my wife, Vicki, and I drove them back to see their old abbey and enjoy a barbecue with Bill and Alane White.

One summer, my daughter and three nieces — then all in their 20s — joined us. I knew my young kin would be polite to the much older monks, but I was surprised at how quickly other bonds developed.

It started with basic kindness.

The young folks assisted the monks in and out of cars, with their walkers and canes, and in moving around.

After helping the old men get their lunch, instead of burying their faces in their cellphones, the millennials sat down and ate lunch with the monks. They chatted about their work and lives.

The monks asked questions

and told jokes. One monk shared a TikTok video someone had sent him, describing the three most difficult things for people to say:

“I’m sorry, I love you, and Worcestershire sauce.”

My nieces, who are pilots, shared flight stories with Father Alan Hohl, who was a Navy pilot. He told them he missed flying but had enjoyed “a wonderful life as a monk.”

The young folks were touched. “I have no idea what I’m doing with my life,” my niece Kaylin said, “but no matter the journey, I just hope I can have that same contentment and gratefulness when I reflect back on my life the way Father Alan does.”

Nuns & Nones

Bill’s idea about a missionary program for monks also reminds me of the Nuns & Nones program, which brings together aged Catholic nuns with millennials who check the “none” survey box regarding religious affiliation yet who also yearn for a spiritual life.

The two groups inevitably find common ground.

In a 2019 article, a none said, “We millennials…hunger for spaces of community, belonging, meaning, depth, and we aren’t finding [them]. …And so to be able to find that with these Catholic sisters who hold wisdom of their traditions from centuries is a gift for us.”

A participating nun said, “I’m deeply impressed with [the nones’] wanting to make the world a better place, with their

questions, with what they’re seeking. That’s not any different from what I’m seeking or we’re seeking.”

There’s reason for both gloom and hope about the current state of decline in American monastic life. Benedictine Sister Joan Chittister says it is like grieshog, an Irish practice of burying warm coals under ashes to preserve the embers in order to start a fire the next morning.

She believes it is “a holy process, this preservation of purpose, of energy, of warmth and light in darkness. What we call death and end and loss in our lives, as one thing turns into another, may, in these terms, be better understood as grieshog, as the preservation of

the coals. As refusing to go cold.” Could Latter-day Saint missionaries help ignite those embers and start the next monastic fire? It’s a heartwarming thought.

Michael Patrick O’Brien is a writer and attorney living in Salt Lake City who frequently represents The Salt Lake Tribune in legal matters. His book “Monastery Mornings: My Unusual B oyhood Among the Saints and Monks,” about growing up with the monks at an old Trappist monastery in Huntsville, was published by Paraclete Press and chosen by the League of Utah Writers as the best nonfiction book in 2022. He blogs at theboymonk.com

At an academic gathering in 2011, the distinguished historian Richard Bushman declared that we had entered a “golden age” for Mormon studies. The setting was an academic conference held in the Springville Art Museum that celebrated Bushman’s 80th birthday, and his remarks were delivered in a room filled with artistic portraits as well as earnest scholars. A communal feeling was palpable.

“All the papers and books we produce,” Bushman proclaimed, “are implicitly acts of friendship.”

That spirit of collegiality was endemic for the new age.

As a graduate student at the time, I was thrilled with this message. I, along with around a hundred other attendees seated on metal folding chairs, shared Bushman’s optimism. It seemed the future for those of us affiliated with Mormon studies was exceptionally bright.

More than a dozen years later, the world feels quite different. Despite a continued flow of excellent scholarly work on the various faith traditions that originated with Joseph Smith, the climate appears more combative than congenial. Charting how that came to be can tell us a lot — not just about an admittedly academic niche but also about the religious community it seeks to interrogate.

The arrival of ‘Camelot’

Meadows” book. Archival access once again broadened. Academics returned to seeing the world of Mormonism as something worth investigating. And because of the democratization impulse that came with the World Wide web, Latter-day Saint authorities recognized, albeit begrudgingly, that this freedom of exploration was inevitable.

By the time of Bushman’s remarks in 2011, it seemed like the effort to cultivate a welcoming environment for Mormon studies scholarship had succeeded. He justifiably believed that “history writing in our times is built on a much steadier foundation than [Arrington’s] Camelot, with much better prospects for continuance.”

critical inquiry that is deemed too “woke.” Universities, and the scholarship performed on their campuses, became battlegrounds and the targets for those who demand a more “patriotic education.”

Latter-day Saints have experienced their own unique, though related, cultural retrenchment. BYU faculty were instructed to cease seeking secular approval and instead defend ecclesiastical priorities. Church publishers were told to edify Latter-day Saints instead of speaking to the wider academy. The list of topics that could get faithful researchers in trouble seems to be expanding, not shrinking.

The study of Mormonism has featured a turbulent history. Long skeptical of scholarly discourse, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints veered into critical investigation when it appointed Leonard J. Arrington as church historian in 1972. The position had been around since the faith’s earliest years, but Arrington was the first to have received graduate training in history. He then helped professionalize the historical department by hiring other academics, expanding archival access and initiating an ambitious publication agenda. Participants referred to their cadre as “Camelot.”

The experiment ended in disappointment.

Within a decade, conservative apostles had worked to shutter Arrington’s division, cancel most of the book plans, and move employees to church-owned Brigham Young University. Like the legendary Camelot, the legacy of Arrington’s tenure became one of nostalgia. By the 1990s, some of the best academics were even being excommunicated from the faith or fired from church employment.

Bushman, more than anyone else, helped to revive the hope of critical inquiry over the following decades. He and several others labored to build bridges between ecclesiastical and academic worlds, demonstrating that a detente was possible, even necessary. It proved a winning argument. In the early 2000s, the church again dipped its toes into enabling crucial scholarship, sponsoring the Joseph Smith Papers project as well as the acclaimed “Massacre at Mountain

There were several elements that comprised this new “golden age.” An impressive number of scholars from divergent backgrounds investigated all aspects of the Mormon tradition, past and present. This work was readily consumed by an insatiable public. Donors endowed Mormon studies chairs at prestigious universities. Religious studies programs expanded their Mormon content. Even BYU backed quality research. Most importantly, ecclesiastical authorities, following the lead of then-Church Historian Marlin K. Jensen, appeared openly tolerant, if not supportive, of academic inquiry. The outward facing, affable image that was church President Gordon B. Hinckley’s legacy shaped this vibrant community. No wonder Bushman framed his remarks around “friendship.”

The next decade did not follow that optimistic trend. While new and groundbreaking scholarship still appears every year, the cultural climate, public networks and institutional backing so crucial for the “golden era” quickly splintered along with societal currents that carried the rest of America. The tectonic shifts that accompanied the most recent iteration of the nation’s culture wars cracked the very foundations that appeared so firm just a few years earlier.

Expressions for these divisions were numerous and varied. The MAGA movement, which made substantial inroads within Latter-day Saint communities, exported a deep skepticism toward

And then there remains a pestering suspicion toward scholars who even use the “Mormon” term — despite its utility and necessity being consistently explained. The linguistic dispute is a textual embodiment of the growing chasm between ecclesiastical leaders who demand compliance and the scholars who require independence.

Academic communities have begun to notice. While the LDS Church had been tentatively seen as a potential colleague in scholarly circles — a rarity compared to many denominations that eschew investigation — recent actions and attitudes have been interpreted as confirming fickle stereotypes. There is a general sense in the field that practitioners of Mormon studies, especially those attached to the Latter-day Saint faith, are on shakier ground and are the subject of more suspicion in the academy today than they were before 2011.

Simultaneously, Latter-day Saint donors and readers inevitably face torn loyalties and interests. Can they support Mormon studies when even the word “Mormon” is politicized?

There remain bright spots, of course. The Church History Department completed its two-decades-long Joseph Smith Papers project, an initiative that received universal academic acclaim. Just this year the Church History Library announced a standardized policy to grant access to the personal papers of church general authorities and officers 70 years after their death, a practice that, while

still restrictive, is at least a step forward from the previously inconsistent archival approach. (It has also become increasingly common, however, for authorities to be required to donate their papers to the Church History Library, rather than universities, in order to maintain control.)

But the success of quality documentary work can paper over the cultural divide inherent between the academy and the church. This is especially the case for those who study topics like race, class and, particularly, gender — a crucial focus in scholarly circles but a third rail in the Latter-day Saint faith. These divisions may not disappear for a while, either, as the priorities and principles on either side are only becoming more entrenched.

That warm feeling of friendship has been replaced with a cold sense of suspicion as the governing feeling for the Mormon studies community.

Back in 2011, Richard Bushman rightly observed that it was the “invisible bonds” of academic, community and institutional actors that made Mormon studies such a potent field. Unfortunately, those bonds have been severely tested by the same cultural forces that have fractured the broader nation in the ensuing decade.

The “golden age” turned out to have a staying power no longer than Camelot’s.

Benjamin E. Park is the author of “American Zion: A New History of Mormonism.”

In recent weeks, as I’ve made many phone calls to professional offices, I’ve learned to brace myself for the call to be answered by an “AI assistant,” an artificial voice instructing me to speak clearly and, in a few words, state my business.

That system has never worked for me, even a single time. “Returning Brian’s call.” “BRIAN.” “Make an appointment.” It always results in “I’m sorry. I did not understand. Please speak clearly and in a few words.” Finally, the system connects me with a living, breathing, naturally intelligent human being.

I contrast those inefficient, soulless AI responses to the appeals I read in my daily work o f transcribing historic Mormon correspondence. Latter-day Saints of the past longed for personal connections, personal responses, to the questions that arose in their lives.

In the earliest days of the faith now known as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, people often went directly to founding prophet Joseph Smith to ask the Lord’s will concerning them. Opening sections of the Doctrine and Covenants, a compilation of the responses Saints accepted as the Lord’s voice given through Smith, are described as “revelation given through Joseph Smith the Prophet” to John Whitmer or to Oliver Cowdery, or to Joseph Knight, or to others. They contained the personal responses, the personal connections for which those people of the 1820s and 1830s longed.

1886, illustrate that impulse:

‘My heart and soul’

Church membership grew, Smith’s duties became more numerous, distances became too g reat, for most individual Latter-day Saints to ask for the a nswers they sought through in-person requests of a prophet. The longing for personal responses didn’t abate, though, and people turned to letters, resulting in enormous collections of personal correspondence, much of it now housed in the Church History Library in Salt Lake City, addressed to leaders of the faith. “Dear Brother,” they begin, or “Dear beloved president,” as men and women of the 19th and 20th centuries sought answers.

Some letters are brief and businesslike: “Kindly inform me” of the date of a conference, or the meaning of a passage of scripture, they ask.

Others — the kind I like best — record the correspondent’s stories of joy or tragedy, seeking personal words of wisdom or comfort or advice, and allowing modern readers to share some part of the lives and times of the past. The letters I am transcribing right now, written to thenchurch President John Taylor, in

WThe family of Joseph A. Walston, of Pitt County, North Carolina, converted in 1882 through the ministry of Edward M. Dalton of Parowan. They had been unable to “gather to Zion” — move to Utah — to live with the Latter-day Saint communities there. “I am as firm in the faith today as when I united with the church. ... Can I remain here and still hold membership with the church? ... Though I am here, my heart and soul is with you. I cannot leave you, there is no other place for me.” Apparently assured that h e could be as faithful in North Carolina as in Utah, Walston remained in the South, with daughter Hannah traveling to Ut ah a generation later to initiate temple ordinances for the family.

Or consider the need for a personal answer from his leader, felt by James E. Talmage in 1886. The future scientist and apostle was then a 24-year-old teacher of physiology at the fledgling

hen I think about Jenna, the image that pops up is of her teaching singing time in Primary with a broken foot. I had been trying to sneak a peek at my kid through the door, but instead she caught my attention — naturally pretty with long brown hair, a pink-knit maxi dress draped over one of those scooters people use instead of crutches.

All I knew at the time about Jenna, not her real name, was that she had recently had her fourth child, her eldest son had a rare genetic disorder, and yet there she was, doing her congregational calling in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints while wounded.

I’m sorry to say the sight made me mad. Why did the church ask so much of people? And why was Jenna saying yes?

Jenna’s baby grew, her foot healed, and my impression remained that she was one of those ideal Latter-day Saint women who gives whatever she is asked for the Lord. Then I got called to be the ward choir

Brigham Young Academy in Provo. Times were hard and the school was so short of funds that Talmage had received none of the $1,200 salary he had been promised for teaching the previous year. Still, he felt loyalty to the school and did not want to abandon its principal, Karl G. Maeser, in the time of need. Should he follow the advice of apostle Francis M. Lyman from earlier in the year? Lyman had told Talmage to return to the East, “there to continue my scientific studies, and also to take a course in medicine and surgery ... not so much [with the goal] of practicing in the profession, as of fitting myself more f ully to teach physiology, and kindred branches in our schools.” Talmage stayed in Utah.

Adelia B. Sidwell of Manti had an urgent appeal in 1886, one that required advice and assistance she had been unable to secure from lawyers or local faith leaders. In 1883, her husband, George, had been killed in a logging accident, leaving her to care for their eight children. Her only financial asset was a legal judgment the Sidwells had obtained a gainst a man of some prominence who had moved to Menan, Idaho, leaving $745 of his debt unpaid. He refused to answer appeals for payment, even when Adelia, through her bishop, offered to settle for a third of the a mount due. When he finally did respond, he sent the appalling message that “all my time is devoted to church business and

I get nothing for it. ... If I had the means, I would try and settle with you, not because I think the claim as it now stands just, but to get rid of you.” I do not have John Taylor’s response to her personal appeal, but having seen his care for other widows and orphans, I have to hope that he intervened to help the Sidwell family.

Work through local lay leaders

Latter-day Saints continued to make such personal appeals, seeking personal connections and personal ancestors, with their religious leaders, as shown by the correspondence in such leaders’ document collections, through the 1960s, at least. Since then, general leaders have increasingly asked that members not contact them directly, but counsel instead with local lay leaders. I am not at all surprised by that request — just as leaders’ duties eventually reached the point where letters needed to replace in-person visits, the time and attention needed to respond to the thousands of personal letters they received eventually became too great. They have pleaded with members to share that burden with stake (regional) presidents and bishops.

But such requests from high-level leaders cannot quell the desire of Latter-day Saints to receive personal, individual attention to their questions and problems. Rather than writing those questions to general authorities, today’s Saints are advised to seek answers by having questions in mind while listening to General Conferences. “Answers to your specific prayers may come directly from a particular talk or from a

specific phrase,” apostle Dieter F. Uchtdorf advised in 2011. (And yet I cannot refrain from noting that some general authorities, including President Dallin H. Oaks, now a member of the First Presidency, still acknowledge reading personal letters from Latter-day Saints, as evidenced by his 2016 remark that “sometimes I receive a letter from a member that gives me an important insight on the subject” of a forthcoming talk.) Whether believing Latter-day Saints w ho have faith that God speaks through prophets and apostles, or simply people who acknowledge that men a nd women of experience can share wisdom in difficult times, many will be listening to conference in coming days hoping, praying, longing for the sorts of inspiration and answers we all need in difficult times — and surely our times are difficult. Personal answers will never come through “AI assistants” that cannot understand — no matter how slowly and carefully you speak. I hope you can find answers — comfort, ideas, hope, personal connection — to your own problems in the coming days.

Ardis E. Parshall is an independent research historian who can be found on social media as @Keepapitchinin and at Keepapitchinin.org She occasionally takes breaks from transcribing historical documents to promote the aims of the Mormon History Association’s Ardis E. Parshall Public History Award.

pianist, which I should have thought twice before saying yes to, as I had not played the piano for some 15 years. It was a talent I long ago had hidden, but I figured I could handle accompanying an occasional hymn. The bishopric set up a meeting for me and the new choir director, and I gulped when Jenna walked in. She expressed devastation at being released as the Primary chorister but willingness to try this new challenge. Within a few days, she had sent me a binder full of sheet music. The songs were not hymns but rather sprawling Sally DeFord arrangements that had me paralyzed with fear. She created a Linktree profile with recordings of all the songs (including their individual parts) and I thought, “Great, she’s a pioneer woman, and she’s tech savvy.” I

I was at her dinnertime ambition.

“You should stay,” she said.

“For dinner?” I asked. It was 2:15 at this point.

“Yes,” she insisted. “I get so bored being home alone all day.”

I laughed nervously and deflected it, then stealth-texted my husband.

Me • She invited us to stay for dinner. Do you think she really wants me to or is she being nice?

Husband • Dinner? That’s in three hours.

Me • I know! What do I do?

Husband • Ha ha. I can’t wait to find out.

I told myself I’d go outside for 20 minutes and see how it went. My social anxiety was on high alert, but it turned out she was right. It was so much less boring to be a mom with a friend. And I was weirdly clicking with Jenna. Before I knew it, 5 p.m. came and we were side by side slicing avocados. She had gone to change a diaper when, to my horror, her husband came home from work and found me in his kitchen. “Oh, hi,” I blurted. “I’m just here because we had a playdate and then she said we could do dinner and then …”

“Rebbie lives here now.” Jenna cut in dryly, rescuing us both.

Soon enough my husband joined, and we had a lovely meal. Our collected kids sat at a Fisher-Price table in the living room, giggling at potty jokes while we asked get-to-know-you questions. I had the strange thought that maybe I didn’t actually know anyone at church. Finding harmony

The weeks have stretched on and choir has become more fun. Having never been in a ward choir, I don’t know what it’s usually like, but this one feels good. The regulars include a 6-year-old boy in the soprano section, an elderly man who recently lost his wife, and two teenage brothers who sing tenor while elbowing each other on the couch. It is odd to realize that while my attendance is born of duty, everyone else seems to be there for joy.

Jenna and I see each other more: over treats after choir, at playdates, when my printer breaks down and she offers hers. At one point, I get a pickleball injury and tell her I may need to skip a week of rehearsal. She demands I take the month off, because she knows pain sucks. At our next playdate, I ask about her foot and learn it hasn’t quite healed and might never do so. I tell her she’s born to be the choir director and she says, “Are you kidding? I barely said yes to this calling.”

We share more dinners. One where it’s leftover night and, as I start the quesadilla station for our kids, she pulls out Tupperware after Tupperware to ask what I want. Butter chicken? Chicken Marsala? Corn chowder? I pick corn chowder and am struck by the thought that perhaps the most intimate

thing you can do with a friend is eat food out of their Tupperware.

Maybe nice is simply nice

I’m not sure why I feel so compelled to tell you about Jenna. Perhaps because I’m sick of people putting Latter-day Saint women into boxes. Perhaps because I thought I was above putting them into boxes until I found myself doing it to her.

By the time the holidays roll around, Jenna has pulled out all the stops. She’s arranged a version of “He Is Born, the Divine Christ Child” that, in her words, “is a bop.”

There’s a flute involved, the choir sings a verse in French, and I practice more than ever because the first two lines are a fast-paced, accidental-filled frenzy only the piano plays.

We’ve been practicing since October, but as the piece comes together at a December rehearsal, I realize I feel it — that warm buzz I have in my best moments at church. I have always connected the feeling with the divine Christ child, but maybe it’s also to do with my having found an outlet for a talent I thought was lost — a talent that for so long connected me to the divine, and does again, thanks to Jenna.

I am ready for the fireside, er, carol-side, until I sit down at the piano. Between the packed meetinghouse and the formality of everyone in Christmas best, my performance fears come flooding back. I botch the intro, playing

loud and fast with plenty of accidentals, just not the ones written on the music. Thankfully, I’m soon rescued by the singers and recover enough to accompany the rest of the song.

Afterward, I think of texting Jenna an apology. I know how much work she put into this. But before I can, she has sent me a message thanking me for how beautifully I played and saying how grateful she is that we get to work together.

Is Jenna just being nice? I wonder again. But the more I think about it, I’m not sure what that even means. Is niceness fake if it is done with effort? Is a friendship void if it starts out of obligation?

For years now, I’ve been complaining online that there isn’t any mainstream film or TV centered around active Latter-day Saints. The reason, people tell me, is because “real Mormons” are too moral, too levelheaded, too boring. I’m told viewers want MomTok drama, or to “investigate” Ruby Franke, or to see whether a good Latter-day Saint girl will spend a night in the fantasy suite of “The Bachelor.”

But let’s imagine Jenna’s show, just to see. We’d get lots of Jenna at her computer late at night rewriting church music (boring). In her kitchen scooping leftovers into Tupperware (unglamorous). Attending school board meetings she doesn’t have time for in order to advocate for her disabled child (tedious). Maybe hitching her baby onto her hip — at home, at the store, at the park, during choir (monotonous).

Maybe we’d see Jenna working to make friends with someone who kept trying to put her in a box, and then them making quesadillas together (snooze). It’s a show so boring even I wouldn’t watch it, but I feel pretty lucky to live it.

Rebbie Brassfield is a writer and creative director in the advertising industry. In real life, she’s a mom of two boys living in the suburbs. Online, you can find her overanalyzing media representations of Latter-day Saints on her Instagram account or podcast, “Mormons in Media.”

In the past, I’ve chided and maybe even ridiculed some of the peculiar cultural aspects of my religion, a religion in which I mostly find rock-solid faith and good comfort in spiritual matters. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, indeed, has its standards and its weird adorning quirks, even a few that have leaned with harder edges toward doctrine.

Either way, there are bits and pieces the church has pretty much nailed, in some cases long before a majority of folks on the outside got around to figuring them out. What follows here, absent of too much smart-alecky sarcasm, are eight examples of sound practices, principles and notions, some of which only nudge up against doctrine or worship or strict spirituality.

The Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square was and is an enlightened idea.

It is said Brigham Young started up a small choral group within

GORDON MONSON

a month of the pioneers entering the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, and The Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square represents the continuation of that emphasis on music.

The choir — and its companion orchestra — has performed around the globe at major events. You’ve probably heard that it started a show called “Music and the Spoken Word” in 1929 and that it now is the longest continuous network radio broadcast, carried by more than 2,000 stations.

One of my more memorable sports moments came when, shortly after 9/11, the choir, dressed in jeans and T-shirts, the kind of

Smoking is bad for you.

Joe Camel and the Marlboro Man never approved, but as a part of its Word of Wisdom, the church dissuaded — and later forbade — its followers from using tobacco initially back in 1833. Believe what you want about WoW’s origin, whether it came from divine revelation to church founder Joseph Smith or simply a strong suggestion from his wife, Emma, who reportedly grew tired of cleaning up the mess created by tobacco-chewing and -smoking church leaders during their School of the Prophets meetings. Whatever prompted it, and whatever other parts of the Word of Wisdom now seem erroneous or incomplete or inconsistent,

the anti-tobacco element was not just revelatory, it also was way before its time.

The church was among the first corners of society to side against smoking. Back in the day, John Wayne, Ronald Reagan, physicians, dentists, the Flintstones, even Santa Claus appeared in cigarette commercials. Then medical research came along. An activity/habit once seen as a signature of cool — think Marlene D ietrich standing in silhouette, blowing smoke in a dark doorway — is now denounced by health officials. Chalk one up for Joseph and Emma.

Alcoholic drinks are unhealthy.

Throw another bone to J.S. As a part of the Word of Wisdom, the founding Latter-day Saint prophet indicated that alcoholic beverages should be shunned. That was not completely religiously revolutionary — even biblical verses warn against “strong drink.” But Smith further canonized that warning to the point that modern church leaders have made abstinence a calling card for devout Latter-day Saints. It’s an identifier for church members. If they don’t dri nk wine at dinner or a beer at a game, they’re often asked, “Are you Mormon?” Yeah, often they are.

As a matter of law, Prohibition was a lousy idea. The 18th A mendment succeeded in fertilizing ground for the rise of organized crime, failing miserably a s a bastion of prim-and-proper

knock-around attire fans would wear to a Utah Jazz game, took the floor during halftime at the Delta Center and sang a song about America that, well, let’s just say it stirred up a whole lot of dust in the arena. Music does that, its effect on people conjuring emotion and giving hope and solace. I talked a few days

ago to a choir member, a dude with a fantastic voice, and asked him what the best thing is about being a part of it. His response: “You go to perform in front of all kinds of people who might be happy, who might be sad. Some are going through hard times, going through hell for whatever reason, and to give them

just a bit of peace is a remarkable feeling.”

The choir sings religious, patriotic and popular songs. I just wish it would occasionally belt out a Beatles or Led Zeppelin tune. I’d pay good money to hear the choir’s rendition of “Let It Be” or “Stairway to Heaven.”

The church’s welfare system provides positive opportunity.

The church historically has looked for ways to aid its own people, and, in 1936, with the nation in the grips of the Great Depression, it formed a welfare system that enabled unemployed people to gain assistance for labor they provided, work that included building churches, cultivating farms, and growing and processing food.

The welfare plan has evolved over time, but it still helps millions of individuals and families in nearly 200 countries, according to the church, with food and water, health care and housing, education and employment. That aid assists followers of the faith and those outside of it. Not bad.

The Relief Society creates sisterhood.

A women’s organization inside this patriarchal church that has existed since 1842, the Relief Society, with more than 8 million members, was and is set up to help individuals and families with temporal and spiritual support. The group’s aim is to provide charitable association and assistance when and where those needs emerge.

The women of the church make up a remarkable force. In fact, it would be an inspired idea at an upcoming General Conference to have the Relief Society leaders run the whole show, pick the speakers, dominate the talks, share their ideas freely, do whatever they want to do to make the sessions better, more memorable, even more meaningful.

righteousness. Many people enjoy an adult beverage or two or t hree in moderation. No big surprise there. Still, as far as what recent research has shown, alcohol is straight poison for the human body.

You can look it up. According to the World Health Organization, there is no “safe” level of drinking. And the U.S. surgeon general’s office has called for labels — like those on cigarette packs — warning consumers of alcohol’s proven ties to cancer.

I’m no expert on this, and I appreciate Jimmy Buffett having wanted, as he sang it, “that frozen concoction that helps me hang on,” but it appears that doctors and researchers in the 21st century are discovering what Smith was onto nearly 200 years earlier.

Called to serve — right away.

A young Latter-day Saint family in Lagos, Nigeria, watches General Conference in 2021. The church emphasizes the need for strong families.

An emphasis on family helps society.

Folks inside and outside the church may agree or disagree with the manner in which the faith defines family, and there is room for criticism regarding the narrow view Latter-day Saint leadership has taken on that issue. But in a world where the splintering of families — however they are made up — has hurt many people, especially

Genealogy, for some, is fun.

Not sure if awareness of the church’s genealogical work spread by way of the enormous popularity of the 1970s television epic “Roots,” but however it caught on, pursuing family history has mushroomed as more and more people explore a simple yet profound question: Where did I come from?

The result has brought some families closer, connecting generations spanning hundreds of years. It’s kind of cool to discover who your great-great-great grandfather and great-great-great aunt was, where they lived, what they did and whom they loved.

A family member once informed me that our line went back to a king of England, but that story seemed suspect. I do know that an ancestor on my mother’s side was a horse thief. So there’s that.

children, the church’s emphasis on the importance of preserving these circles of love is notable. It iterates and reiterates the significance of marital fidelity. If that counsel were followed, it would spare a whole lot of heartbreak. Were the church to expand its definition of marriage and family, making it more inclusive — granted, a big if — its family approach would help heal even more around the world.

Partly because of the church’s connected and efficient organizational structure, when community needs come up, Latter-day Saints are able to help — and in a hurry.

An example: When the horrific wildfires broke out in Los Angeles County, destroying so many residents’ homes, Latter-day Saint bishops and other regional leaders almost immediately were in contact with their congregations, seeking detailed information on who was affected and who needed help — a place to stay, clothing to wear, food to eat.

Whenever disaster strikes, those yellow-shirted Latter-day Saint Helping Hands volunteers have become almost as ubiquitous as Red Cross tents. And the faith has stepped up its cash donations to help in humanitarian efforts around the world, spending some $1.3 billion in 2023 and promising to boost that amount in years to come. Ah, the colors of charity — yellow,

red and green.

“We will double the humanitarian work again and then again,” W. Christopher Waddell, first counselor in the church’s Presiding Bishopric, pledged in a national TV broadcast.

Like members of other faiths, such service is baked into the Latter-day Saint culture, and the church has the neighborhood framework, collective mindset, scriptural motivation, people power and growing wealth to give more — so much more — when needs arise.

Maybe it would do Latter-day Saints and the church that claims them good to laugh at themselves a little more when cultural peculiarities edge toward the bizarre, to acknowledge and apologize when mistakes are made, and to give credit to themselves when and where due. Nothing wrong with any of that. After all, credit in these eight cases — and in a number of others, too — is due.

The four ‘churches’ within the LDS Church — and who leads them

For a religion sometimes critiqued for its conformity, there are a variety of Churches of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that you might see at General Conference this weekend.

Of course, I don’t mean literal churches. Rather, there are different ways of understanding the faith, different emphases and different visions of what the project of the church might be.Members often divide leaders into categories such as “conservative” or “liberal” or “progressive,” but those labels don’t tell us much. Their meanings are fluid, and though they might carry with them religious connotations — about belief in evolution, say, or how literally to read some stories in scripture — they are also increasingly associated with politics. This only muddles the water even more. The label “conservative” in politics today might indicate support for Donald Trump, for instance, or it might mean opposition to him. All this is to say, these labels are often not terribly useful for understanding what exactly somebody believes — particularly when it comes to religion. So what follows are other ways of talking about what being a Latter-day Saint means to various church leaders. I should emphasize that I don’t consider these “churches,” as I call them, mutually exclusive, with clean and clear lines separating the people I discuss. Rather, think of them as ideal types and the figures I invoke as representing that type, even as they might fit into others as well. Nor do I insist these are the only types. These are simply some of the various ways to understand and practice religion that I see on the current Latter-day Saint landscape.

Representative • Russell M. Nelson. Past representatives • David O. McKay, Bruce R. McConkie.

Former apostle Bruce R. McConkie and former church President David O. McKay could be gregarious and sociable in private, given to jokes and belly laughs. In public, though, McKay was generous and warm, while McConkie was stern and doctrinaire. They also took differing positions on particular points of doctrine. McConkie despised the theory of evolution; McKay was open to it. Such differences obscure a common similarity. Both men were deeply optimistic about human capacity to make the right choice if told what the right choice was. For McKay, this faith manifested in deeply humanistic sermons about our divine potential. For McConkie, it manifested in a strict focus on proper belief and right behavior.

For both of them, these impulses grew out of the early 20th-century progressive era, a time when Americans invested deep faith in education to teach people to be good, and many church leaders used that language to understand their faith.