Special Feature: Indoor Air Quality

Special Feature: Indoor Air Quality

Born in Bradford: Is this the UK’s most important air quality research project?

Born in Bradford: Is this the UK’s most important air quality research project?

Special Feature: Indoor Air Quality

Special Feature: Indoor Air Quality

Born in Bradford: Is this the UK’s most important air quality research project?

Born in Bradford: Is this the UK’s most important air quality research project?

We are connecting the dots of a new mobility revolution that is transforming our towns and cities.

With the broadest end-to-end portfolio of intelligent traffic management solutions, we work with cities, highway authorities and mobility

operators to make their road networks and fleets intelligent, enhance road safety and improve air quality.

It’s time to make the world a better place. We are ready. Are you?

www.yunextraffic.com/uk

Publisher: David Harrison

d.harrison@spacehouse.co.uk

01625 614 000

Editor: Paul Day paul@spacehouse.co.uk

01625 614 000

Business Development Manager: Jason Hall jason@spacehouse.co.uk 07889 212414

Finance Manager: Jenny Leach jenny@spacehouse.co.uk

01625 614 000

Administration: Jules Pointon admin@spacehouse.co.uk 01625 614 000

AirQualityNews Procurement Guidepublished by Spacehouse Ltd, Pierce House, Pierce Street, Macclesfield. SK11 6EX. Tel: 01625 614 000

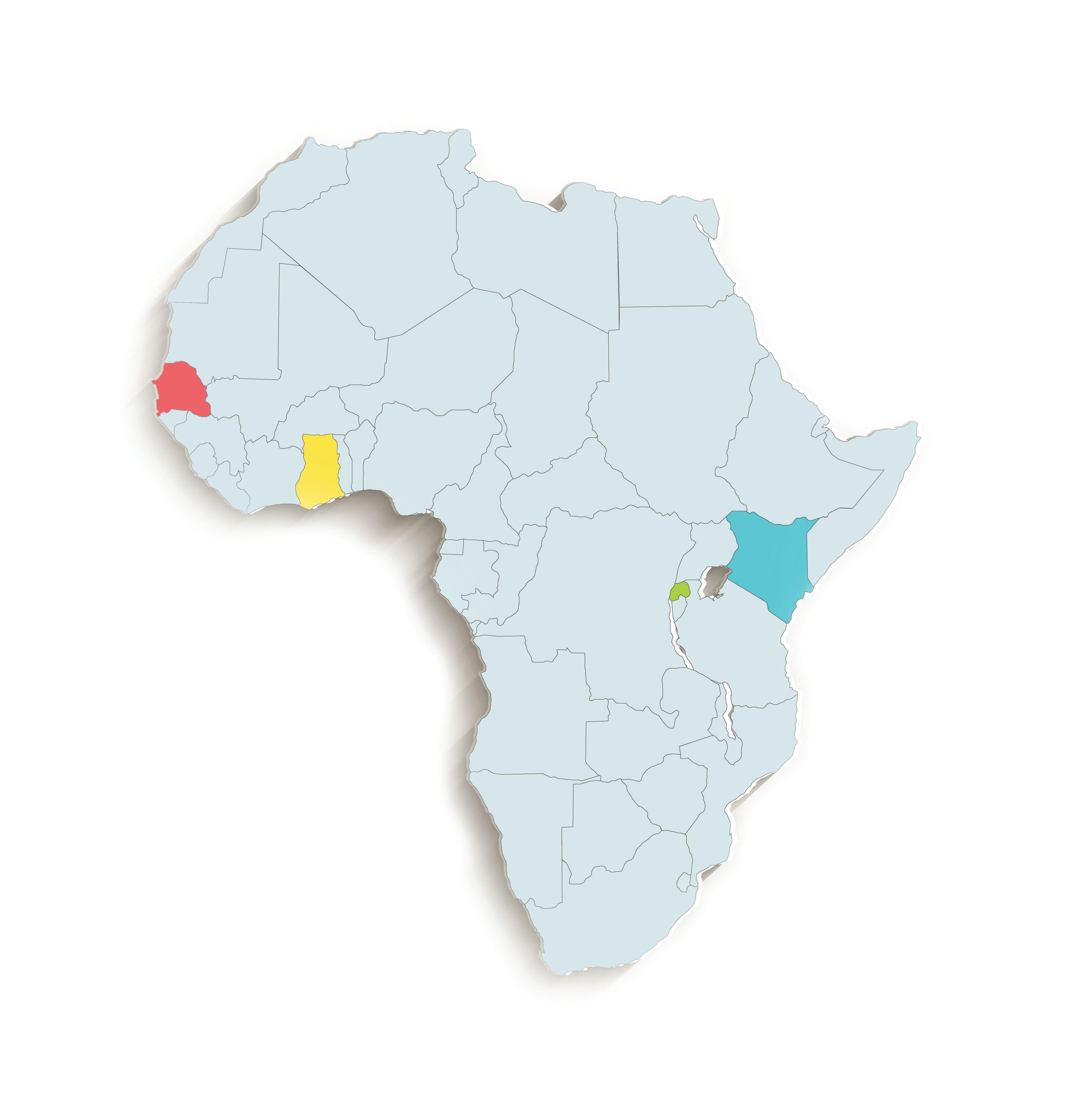

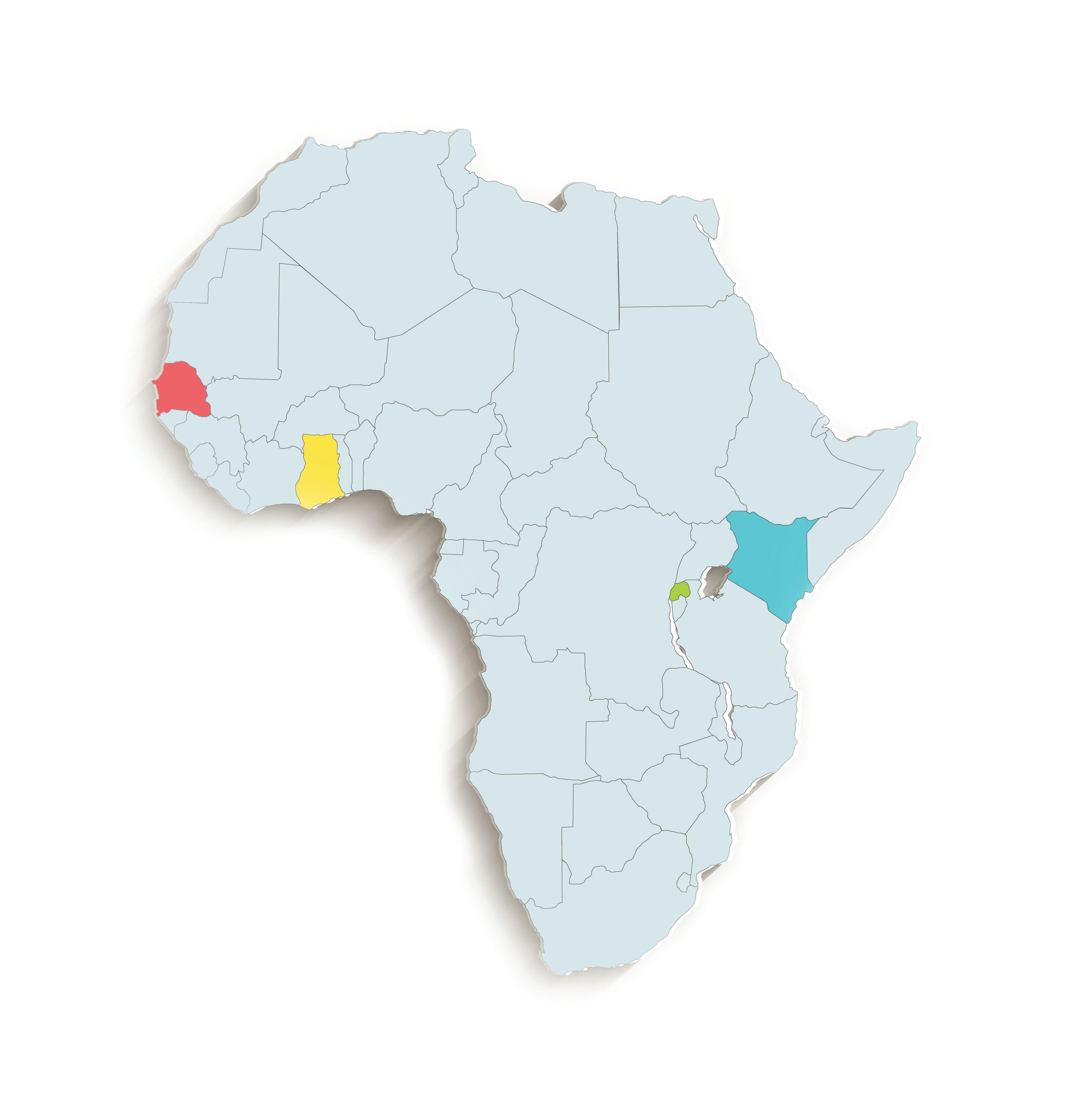

At the time of writing, the Africa Climate Week & Summit is taking place in Nairobi, Kenya. The fact that I’m 4,388 miles away doesn’t make it less consequential.

The new Air Quality Life Index, which we discuss on our news pages, casts light on the exposure of Africans to poor air quality. In areas of the worst affected countries – and four of the world’s ten most polluted countries are here –air pollution will reduce the population’s life expectancy by over five years.

Above and beyond the effects of ambient air pollution, domestic cooking exerts a painful toll on the continent’s population. Women and children are especially affected as they are more likely to be closest to the fires fuelled by firewood or kerosene. Across Africa efforts are being made to transition households to cleaner fuels and in this issue I report on the progress of a few of those schemes.

Our Special Report this issue focusses on indoor air quality and our traditional threepronged attack takes in the much-overlooked presence of VOCs in the consumer products that we take for granted. We’re grateful to Amber Yeoman from the University of York for highlighting the issue for us here. Similarly, thanks to Ronnie George of Volution for taking us on a deep dive into the mechanics – and politics – of ventilation systems. InfoTech’s Simon Guerrier completes the threesome by examining some of the smart tech available to help the public measure and control their indoor air quality.

Professor Rosie McEachan spoke to us about the Born in Bradford Research Programme at our Manchester Conference earlier in the year, and in this issue she expands on that, bringing us up to date with a unique and incredibly important piece of research.

Our legal friends at ClientEarth are back to explain the implications of the Retained EU Law Act now the ink has dried. Needless to say, there are things to worry about.

Elsewhere, Martin Guttridge-Hewitt talks to people involved in exploring the use of hydrogen as a fuel, before heading off to Utrecht – the world’s cycling capital – to speak to Belle de Gest – the city’s Bicycle Mayor.

In this issue’s Local Authority feature, Emily Whitehouse sees what Islington Council are doing to ensure that care home residents in the borough are able to enjoy clean air.

All rights reserved. Reproduction, in whole or part without written permission is strictly prohibited.

Paul Day

Tel: 01625 614000 paul@spacehouse.co.uk

Pages 6-7 News: Sadiq Khan retreats from a Zero Emission Zone in London

Pages 22-23 Feature: Good Technology: Getting to grips with the gizmos that promise us better air at home

Pages 10-12 Feature: Balance of power: Is green hydrogen the missing link in pollution-free fuels?

Pages 14-16 Feature:

A breath of fresh air: How Born in Bradford is using evidence to influence air quality policy and improve health and reduce inequality.

The hidden emissions from consumer products: How everyday goods contribute to indoor air pollution

Pages 24-26 Feature: Ventilation: The headwinds & tailwinds delivering healthier indoor air

Pages 28-29

Legal: REUL Act postmortem: what does it mean for air quality and environmental protections?

Pages 30-31 The Big Interview: Belle de Gast

International: Continental Shift: The drive to transition African nations towards clean cooking

Pages 32-35

Wildfire smoke can trigger inflammation in the brain, new research finds

The Canadian wildfires have been a huge threat to the health of North Americans this summer and new research suggests its effect might be worse than first thought.

The paper by University of New Mexico Health Sciences finds that wildfire smoke can trigger inflammation in the brain that persists for a month or longer. The team identified both pro- and anti-inflammatory responses as particles from the smoke entered the circulation from the lungs and crossed the blood-brain barrier, a layer of tightly packed cells lining blood vessels in the brain.

The findings are concerning given how many people are now regularly exposed to wildfire smoke: ‘Neuroinflammation is the seed for all sorts of bad things in the brain, including dementia, Alzheimer’s disease – the buildup of the plaques – but also alterations in neurodevelopment in early life and mood disorders throughout life.

‘If you’re a firefighter, or if a citizen in a community that has suffered smoke exposures, you could be having neurocognitive or mood disorders weeks or months after the event.’

Local authorities going full tilt at solar installations

Widespread appreciation greeted the announcement that Northumberland Council had festooned the car park at their headquarters with sufficient solar panels to save between £100,000 and £150,000 a year in energy bills, as well as providing 120 EV charge points.

The new installation features 800kW solar panels which will power the main building and provide electricity to the charge points for fleet and staff vehicles. Any excess will be stored in a 400kW battery energy storage system.

Portsmouth City Council responded by announcing they had got permission to install an even bigger system across five buildings and three car parks at the council-owned Lakeside North Harbour Business Park.

The five buildings will be fitted with 1,820 roof-mounted solar PV panels, while there will be 7,105 panels installed as solar canopies above existing car parking spaces. It is anticipated that the system will generate more than 4 million kWhs per annum, enough to power 1,300 homes for a year and is projected to save more than 860 tonnes of carbon dioxide from being emitted each year.

A new research project by Imperial College London will see air quality monitors placed in over 100 homes across West London to assess changes in air quality, both inside and outside the home..

The headline findings of the research is that more people in outer London are compelled to own cars by the lack of reliable public transport or active travel infrastructure. This is obviously timely information given the expansion of the city’s Low Emission Zone.

In the foreword Sak Gill, Vice-President and General Manager South East England, Enterprise Holdings says: ‘Outer London is, by definition, different to inner London. How residents across outer London move around is very different too. A lot of journeys are local and don’t head into or terminate in central London.’

69% of households in outer London have access to a car, compared to 42% in inner London and 77% in England as a whole.

38% of journeys in outer

London are made by car –exactly double the number in inner London – and half of these journeys are less than two miles long.

The report identifies three areas in which change is needed: the cycle network needs greater coverage, public transport routes need connecting to new developments at a much earlier stage and shared transport should be delivered more consistently.

Claire Harding, Interim

Chief Executive of Centre for London said: ‘There are 5.4 million people in outer London – as many as live in Scotland. But many of these people don’t have access to the transport options that their inner London counterparts enjoy.

‘Improving the options people have to travel sustainably for local trips, not just commuting, is at the heart of making London a more liveable city.’

The new Air Quality Life Index, which is produced by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago has been published and, as ever, it contains some startling headline figures relating to the effect of air quality around the world.

Globally reducing fine particulate pollution to meet the World Health Organization’s guidelines, would see the average person live 2.3 years longer — a combined 17.8 billion years worldwide.

The figures focus the iniquity of air pollution. Of all lives lost to poor air quality, 92.7% of them are in Asia and Africa, yet just 6.8% (Asia) and 3.7% (Africa) of governments provide their citizens with fully open air quality data. And in Africa, just 4.9% of countries have air quality standards.

These iniquities are exacerbated by the disproportionate delivery of philanthropic funding to battle air pollution. The whole of Africa receives $300,000 whereas, according to Clean Air Fund

figures, projects in Europe and North America received $34m

Michael Greenstone, the Milton Friedman Distinguished Service Professor in Economics and co-creator of the AQLI said:

‘Three-quarters of air pollution’s impact on global life expectancy occurs in just six countries, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, China, Nigeria and Indonesia, where people lose [from] one to more than six years off their lives

because of the air they breathe.

Amongst the gloom, there are stories of remarkable success which show what can be done. In China, people are still suffering from air quality that exceeds WHO limits quite spectacularly but, thanks to the ‘War Against Pollution’ that began in 2013, there has been a 42.3% fall in pollution, boosting the average Chinese citizen’s life expectancy by over two years.

Four countries in Africa are among the ten most polluted in the world: the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Burundi, and the Republic of Congo. In some parts of these regions, pollution levels are 12 times the WHO guideline, taking as much as 5.4 years off lives— and becoming as much of a health threat as HIV/AIDS and malaria.

In their newly published Air Quality and Climate Bulletin, The World Meteorological Organization has highlighted air quality’s relationship with hot weather and called for air quality and climate change to be treated as connected parts of the same problem.

Based on 2022 data, the report shows how heatwaves and desert dust were behind a dangerous drop in air quality last year, leading to more ozone pollution, increased concentrations harmful particulates and reactive gases such as nitrogen oxides.

In Europe, hundreds of air quality monitoring sites registered levels exceeding the WHO’s ozone air quality guideline levels of 100 µg m³ over an eight-hour exposure.

WMO Secretary-General Prof. Petteri Taalas said: ‘Heatwaves worsen air quality, with knock-on effects on human health, ecosystems, agriculture and indeed our daily lives. Climate change and air quality cannot be treated separately. They go hand-in-hand and must be tackled together to break this vicious cycle.’

Prof. Taalas points out that while this report refers to

meteorological events from 2022, this year has proved to be even more extreme, ‘July was the hottest ever month on record, with intense heat in many parts of the northern hemisphere and this continued through August.’

finding them to seriously impact biodiversity, drinking water and air quality Prof. Taalas said: ‘Wildfires have roared through huge swathes of Canada, caused tragic devastation and death in Hawaii, and also inflicted

The 2022 CAZ report published by Bath & North East Somerset Council reveals that compared with 2019, there has been a 26% reduction in annual mean NO2 within the zone, representing an average reduction of 8.5 µg /m³.

A Class C Clean Air Zone was implemented in March 2021, whereby all higher emission vehicles except private cars and motorbikes were charged. A consultation on the CAZ in 2018/9 showed the overwhelming opinion was that a Class C would strike a better balance between tackling pollution and protecting businesses and vulnerable residents.

Until recently, the widescale air quality impact of wildfires has been little understood, but the report draws on new research that examined the deposition of compounds containing nitrogen, downwind of major fire events,

major damage and casualties in the Mediterranean region. This has caused dangerous air quality levels for many millions of people, and sent plumes of smoke across the Atlantic and into the Arctic.'

In 2018, the Mayor of London laid out his plans from getting the capital to net zero by 2050. A schedule was presented that ultimately ends in 2050 with a London-wide Zero Emission Zone and zero emission road transport.

In confirming that he had now dropped that ambition, a spokesperson from the Mayor’s office explained that it would now focus on finding other ways to achieve the capital’s target for net zero emission.

In January this year, the mayor seemed to remain keen on a ZEZ, but was introducing the idea that the London boroughs may be the main drivers of it.

The figures in the recently published CAZ report also show that in the urban area outside the zone, there has been a 27% reduction in annual mean NO2 concentrations (an average reduction of 7.1 µg /m3) with only one site exceeding the legal limit of 40 µg /m³. Ten sites had exceeded the limit in 2019.

The figures also indicate an additional reduction of 6% in annual mean NO2 concentrations in 2022 compared with 2021, as well as a reduction of 7% within the CAZ boundary.

Since they launched the Parcels Not Pollution scheme in 2019, Hammersmith & Fulham has helped more than 100 local businesses switch to using cargo bikes instead of vans for their deliveries around the borough.

Through the scheme, the council are supporting businesses with free advice and support in the form of oneoff subsidies to help them switch to using cargo bikes, including electric ones, in their day-to-day business.

The scheme offers £1,000 towards purchasing or leasing a cargo bike or 5o% off the cost of using a cargo bike service in a two-month period (up to £300 per month) and runs until April 2025.

In order to reach those targets, a Central London emission zone was slated to take effect in 2025 but in the wake of the ULEZ expansion kerfuffle, he has distanced himself from those ambitions.

Following the launch of a central ZEZ, the original plan was to follow the ULEZ pattern by rolling it out right across the capital, as described in Proposal 35: ‘The Mayor, through TfL

and the boroughs, and working with Government, will seek to implement zero emission zones in town centres from 2020 and aim to deliver a zero emission zone in central London from 2025, as well as broader congestion reduction measures to facilitate the implementation of larger zero emission zones in inner London by 2040 and London-wide by 2050 at the latest.’

Replying to a question from Zack Polanski, he said: ‘Since my commitment to a central London ZEZ was made in my 2018 transport and environment strategies, I have since set an objective for London to be a net zero carbon city by 2030. TfL’s focus will now be on developing plans to deliver this, alongside supporting boroughs who wish to implement local ZEZs. The scope of any update to the ZEZ guidance document is therefore under review.

Fulham-based ManMaid are recent beneficiaries of the scheme, using electric cargo bikes instead of delivery vans.

Mungo Morgan, founder and CEO of ManMaid. said: ‘The biggest win with cargo bikes is the parking. Being able to park them right outside is a massive time saving.

‘If we forget a screwdriver we can just pop outside and pick it up’ The company previously spent more than £7,000 a year in parking fees. ‘That pays for a new bike in itself,’ he said.

The combined power of Vortex and Videalert. Monitor air quality and traffic levels for unprecedented insight and impactful outcomes.

Accessible data dashboard to inform better decision making on clean air interventions.

Identify pollution hotspots

Analyse how congestion impacts air quality

Identify vehicle categories

Identify vehicles above CO emission standards

Find out more at vortexiot.com

Enforce parking and moving traf fic contraventions Part of Marston Holdings

Moving from traditional traffic control methods, the London Borough of Waltham Forest has installed an integrated solution to digitally monitor traffic contraventions and air quality outside schools to improve road safety, enhance air quality and encourage active travel.

Waltham Forest was one of the first London boroughs to take charge of their environment with digital technologies that support decarbonisation, traffic reduction and, most importantly, resident safety and health. As part of a phased development plan, the Council is working towards making Waltham Forest a safer place to live with current interventions to encourage active travel and improve road safety. The existing schemes will integrate with their pollution reduction and traffic management scheme outside specific schools to improve the air and remove idling vehicles from areas where people are most vulnerable.

Over the years, several pollution reduction and traffic management approaches have been trialled and are currently in operation. However, previous interventions have been difficult to validate accurately due to a lack of localised data monitoring from new technologies. Pollution in the borough stems from various sources, including external origins. Within the borough, major contributors to pollution are motorised vehicles, emitting particularly NO2 and particulate matter. The Council sought an approach to gauge and oversee the impact of a school street intervention for pollution attribution. This involved temporal analysis of air quality fluctuations, especially during school pick-up and drop-off times, when exclusive vehicle access applies around specific schools.

Our goal is to make Waltham Forest a safer place to live. Thanks to installing VTX Air sensors and Videalert CCTV cameras, we now have real-time insight into our air quality and controlled traffic measures that aim to improve road safety, improve traffic flow and reduce traffic-related emissions."

Anthony Hall Assistant Director for Highways and Parking Services at the London Borough of Waltham ForestWaltham Forest upgraded its traffic monitoring, where needed, by replacing existing CCTV cameras with advanced Videalert devices, a leading UK provider. Integrated with the latest PCN (penalty charge notice) processing systems, these certified cameras are used to capture vehicles with unauthorised access during school pick-up and drop-off times. By reducing traffic outside schools, the Council gauges carbon reduction impact, validates school street effectiveness, and plan engagement programmes for a sustainable community. The combined data informs policymaking for clean air and road enhancements, contributing to residents' quality of life. This will also help the school encourage active travel transport that has proven studies to improve children’s mental and physical well-being through walking, cycling or scoot to school.

21 unattended CCTV cameras

12 Maintenance-free and SIM-card-free

VTX Air monitors

Integrated data platform – Insights on traffic contraventions, weather, and air pollution

Real-time, hyperlocal air quality data - on NO2, O3, PM2.5, and PM10

Bespoke-built Mesh Network – calibrations and updates are done remotely

Service desk support

Can the most abundant element in the universe be used as a propellant for heavy vehicles and off-grid gas replacement? Martin Guttridge-Hewitt explores the emerging hydrogen market to better understand costs, emissions, and access.

Professor Nigel Brandon is more than qualified to talk about the UK’s future energy mix. Dean of the Faculty of Engineering at Imperial College, London, where he holds a chair in Sustainable Development in Energy, until late-2022 he was director of the UK Hydrogen and Fuel Cells SUPERGEN Hub.

He’s also co-founder of The First Element, a group of technology, science and engineering experts exploring commercial, industrial and consumer use cases for hydrogen and green hydrogen, and identifying potential routes to market. A clear advocate of this fuel type, nevertheless he’s quick to point out that environmental cure-alls do not exist.

‘Green hydrogen is made through electrolysis, [renewable] electricity is our input and there will always be a penalty for that, an efficiency loss

in conversion. Therefore, there will also be a cost associated with the process. So, the first thing to say is if you can use green electricity to power something directly you should do that. A more electric future is the direction of travel,’ says Brandon. ‘But if we’re taking a picture across the whole UK economy, there are a lot of industrial processes which are hard to decarbonise electrically.

‘The First Element is also very concerned with making hydrogen more accessible at a consumer level. So, could homeowners and other building operators produce hydrogen locally from a renewable source, most likely a photovoltaic panel, but for larger applications it could be a wind turbine, and store that locally? Then, can it be used locally to decarbonise energy consumption?’, he continues.

Several markets are being

considered, many of which are off-grid and currently reliant on bottled gas. For example, cooking on a stove without a piped connection, or firing up your barbecue. Others, such as chemical production and steelmaking are too power-intensive to consider electricity alone.

‘It’s not as clear as just saying ‘it’ll all be electricity’ or ‘it’ll all be hydrogen’. It will end up a mix, with more electricity than today and hydrogen … but it depends on where you are and what you need,’ says Brandon. ‘Electricity is going to be the cheapest per unit energy, then hydrogen, then synthetic fuels made from hydrogen.’

Crunching the numbers casts this point in sharp relief. From an efficiency point of view, it makes most sense to run an electric heat pump to warm a house. As Brandon tells us, this offers

around 3.5 units of heat per unit of power. However, installing the system is hugely disruptive and incredibly expensive. By comparison, switching from natural gas to hydrogen requires fewer and simpler upgrades, making it significantly cheaper, but as a result efficiency suffers.

‘There are also going to be sectors of the transport industry which are very hard to electrify with batteries. Aeroplanes are a classic. You’re never going to fly across the Atlantic in a battery electric plane,’ he continues, before adding maritime and shipping to a list of sectors that need too much power for direct electrification. ‘Buses and trucks come next. It might be possible with battery electric, but you might also need a fuel.

‘That may come directly as hydrogen, or a synthetic fuel made from hydrogen, which involves mixing

biogenic CO2 with hydrogen. This gives us a drop—in fuel, which can be used in a standard combustion engine,’ he continues, adding that fuels produced from hydrogen and green hydrogen have their own Achilles heel - price. ‘I often say to folk that synthetic fuels are going to be used for two reasons, one is flying you to New York, and the other is to drive your classic Aston Martin. Beyond that they're not going to have much use because of the cost.’

When it comes to the future of transport, and in particular the role green hydrogen plays in this, Juergen Guldner has plenty to share. As Manager of Hydrogen Technology at BMW, his team plays a central role in investigating how the automobile giant’s production line can decarbonise over the coming decades by incorporating green hydrogen.

The firm currently has a pilot fleet

to showcase what can be achieved with the technology, and some vehicles could be available to buy later this decade. While proud the company now offers a battery electric option for every internal combustion model it makes, Guldner is also clear that a single fossil fuel alternative will not suffice.

‘We’re thinking long-term the world needs a second zero emission technology. There are some use cases where battery electric will have limitations. In the transport sector it’s a complex picture, but the general gist is the heavier the vehicle the more hydrogen makes sense,’ says Guldner, explaining BMW has been researching the gas for 40 years. ‘But we also see potential on the passenger side of things, with vans and light duty vehicles… we get feedback from a certain set of customers that battery electric won’t fulfil their mobility needs,

and they want zero emission.

‘Hydrogen vehicles can offer good value propositions… they have great acceleration, a silent ride, are emission-free - providing it’s green hydrogen - and refuelling is fast, like a combustion engine,’ he continues.

‘Many people don’t want to plan their lives around electric charging, and 20 or 30 minutes to recharge is a hassle. So, for hydrogen we’re talking people who don’t have home charging and rely on public infrastructure. This will always be a problem in big cities. At BMW we think worldwide, and a lot of metropolitan areas will find it difficult to have electric charging everywhere.’

The UK is not immune to this. An October 2022 investigation by AirQualityNews revealed that of the 300,000 charge points Downing Street wants to install by 2030, just 30,000 were in place and the national roll-out shows no signs of speeding up. There are several reasons behind this, including the expense of installing completely new infrastructure. By comparison, hydrogen and green hydrogen can use existing equipment.

‘Electric charging infrastructure has its limitations once you consider the end game – getting 100% of vehicles done. This is where hydrogen really comes into its own because it can use existing gas stations, we just need to retrofit them. The cost is pretty much the same for each unit, it might actually go down once more people are building

the compressors, pumps and so on at stations,’ says Guldner. ‘The interesting bit is studies from Germany and the EU Commission have shown dual infrastructure – hydrogen and electric charging – is the cheaper option if you want to reach all vehicles.

‘Electric charging infrastructure has an increasing cost curve because it involves upgrades to the grid, transformer stations, and so on, to get all the electricity needed to feed charge points. When we think about the kind of big parking garages we have in cities, if you want most parking spaces to be electric it becomes really expensive. We even have to dig up roads to put bigger cables down,’ he continues. ‘The general theme and thinking now is that two infrastructures are better than one, especially as we have to build for peak. If we want to avoid chaos on holiday weekends and so on, when everyone is on the road, hydrogen could be a big relief to the pressure on infrastructure.’

Signs of this approach are becoming apparent, especially on the continent. EU member states have already agreed to build hydrogen fueling stations in all major ‘urban nodes’. This term refers to 424 cities across the region with more than 100,000 inhabitants, where ports, airports and rail terminals are found. Stations will also be placed every 200km along the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) of nine core travel corridors that criss-cross the bloc. Meanwhile, in the UK, the first

purpose-built hydrogen stations will open in 2024 thanks to British start-up Element 2 and an £8million government investment.

‘A lot of the components in hydrogen vehicles, I’m tempted to call them ‘standard’, because the automotive industry has been making them for more than 100 years. Sensors, valves, pipes, the air system, compressors, all these are industrial components. Suppliers today are very interested in this [hydrogen] technology because for them it’s a continuation of their business,’ says Guldner, explaining that the favourable price of infrastructure compared with battery electric vehicles continues through to the parts found in hydrogen engines. ‘So, there are a lot of factors that suggest costs overall will come down, too.

‘While admitting there is still some way to go before we can expect to see hydrogen costs come down, or even widespread adoption - for the time being at least, BMW’s focus is on the last people to transition from high emission vehicles, rather than the first - Guldner is also sure of hydrogen’s place in the future fuel mix. Given what we know about consumer culture, not to mention the ecological impact of elements and metals many green technologies rely on, the idea of plurality and choice is sensible in terms of sales, and absolutely essential if the coming decades stand a chance at stabilising the environment.’

pollution and improving the city’s health.

Nestled in the Yorkshire Dales in the North of England is the City of Bradford. With over half a million residents, it is one of the largest districts in England. It is also a young city, with more than one than one quarter of its population aged under 20, a third of whom are from ethnic minority groups. It is a vibrant city in which to live and work but like many other cities it does have challenges, including areas of very high deprivation. A third of the population live in the most deprived decile compared with England and Wales averages and in tandem with high levels of deprivation are high levels of ill-health. In Bradford people living in the poorest areas will die ten years earlier than those in the wealthiest areas. This isn’t fair.

Based within Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, The Born in Bradford (BiB) project was set up by clinicians, researchers and education practitioners in the city in 2006 to explore the reasons behind ill-health in the city, and most importantly, what we could do about it. To do this we set up a birth cohort. Birth cohort studies are one of the most powerful epidemiological research methods that can explore the factors which influence our health and development over time. As the name suggests, parents (and their babies) are recruited to these studies during pregnancy, and the health and wellbeing of families tracked as they grow up. Families complete regular measurements of health, their life circumstances, behaviours and attitudes, and scientists can measure the quality of the environments in which they live. The richness of the data collected in this

way can help to disentangle exactly which are the crucial aspects of our lives impacting on our health. Importantly, they can also help us to identify the factors which cause health related inequalities.

Between 2007-2011 BiB recruited over 12,500 families with over 13,700 babies to the study and have been following these families ever since. Our oldest BiB children are now reaching their 16th birthday. And the BiB project has grown too: over 50,000 Bradfordians are actively involved in our research, and we host the Connected Bradford database which links up routine health, care and education data for the entire population. BiB works closely with communities and stakeholders to co-produce research priorities and provide a model for the translation of research into practice. This, combined with our research infrastructure makes Bradford a very good place to come if you want to understand the impact of policies to improve health.

We have spearheaded the concept of a City Collaboratory.1 This is an environment where the public, scientists, the local authority, policy leaders and practitioners work with each other. The City Collaboratory co-production model consists of a multistep interactive cycle that places local communities at the heart of decision making (Figure 1). There is active participation in both shaping and using the research, and this also connects academic expertise with policymakers.

Professor Rosie McEachan, Director of the Born in Bradford Research Programme and applied health researcher describes their ‘City Collaboratory’ approach to reducing

Professor Rosie McEachan, Director of the Born in Bradford Research Programme and applied health researcher describes their ‘City Collaboratory’ approach to reducing

research found links between pollution and low birth weight of babies in Bradford.4 As children grow up we found exposure to air pollution during early life to be related to higher blood pressure,5 and poorer brain development 6 at ages 4-5 and indoor air quality to be related to childhood obesity at ages 6-11.7 At a molecular level BiB found exposure to pollution relates to shorter telomere length (an indicator of biological aging).8 We recently looked at healthcare attendances for respiratory health across the city and estimate that one in two visits to accident and emergency as a result of breathing difficulties could be due to high pollution levels. 9

We have demonstrated the stark inequalities experienced by families living in deprived areas which are not only blighted by pollution, but by other environmental hazards such as noise and lack of green space, exacerbating health inequalities.10 (Figure 2).

Over the past 10 years we have been working closely with our partners in the city using our Collaboratory approach to drive down levels of pollution.

Bradford has illegal levels of pollution, centred around the inner city, deprived areas. Rates of respiratory disease are high. The most recent figures in Bradford suggest that 500 people die from respiratory disease each year; there are over 13,000 diagnosed cases of COPD and more than 41,000 people diagnosed with asthma.2 It is estimated that a third of asthma cases in the city are as a result of air pollution.3

BiB research has been crucial in highlighting the importance of pollution on health in the city. Our early

In 2018 Bradford was one of 28 local authorities to receive a ministerial direction to explore ways of improving air quality as quickly as possible, including implementation of a charging clean air zone.

The Bradford Clean Air Programme board was formed comprising representatives from health, planning, transport, and researchers. With a clear focus on health and the reduction of inequalities, the board worked with communities and stakeholders to develop the Bradford Clean Air Plan. Plans were developed based on science and evidence recognising that everything is connected in a whole city approach to tackle the clustering of environmental risk factors.

BiB research from seldom heard communities informed the development of the plans. Communities reported that they were worried about the health impacts of pollution but also worried about the impact that charging the taxi-trade would have on families already on low incomes.11 As a result of this, appropriate mitigation strategies were planned including over £30 million funding to support taxis, buses, lorries and vans to upgrade their vehicles to compliant standards.

In September 2022 Bradford switched on a ‘class C’ clean air zone (CAZ) which charges non-compliant buses, coaches, heavy goods vehicles, vans, minibuses and taxis a daily fee to enter the zone. Private vehicles are not charged. The CAZ includes exemptions and support packages for locally registered vehicles and those that are regularly in the zone. These include financial support for upgrade or retrofit, and the provision of infrastructure for low emission technologies. The CAZ is the third largest in the country and encompasses an area of 22.4km 2. Around 20% of the Bradford population live within the zone.12

These types of policies are increasing momentum. There are currently seven charging Clean Air Zones in England, an expanded Ultra-Low Emission Zone in London, and plans for a range of Low Emission Zones in Scotland. But these policies can be divisive and unpopular, and, as many of the policies are new, UK based evidence on their effectiveness is still in its infancy. Robust research is needed to evaluate the health and economic impacts of these policies.

In Bradford we will use our City Collaboratory to evaluate the impact of the Bradford CAZ on health in the city as well as unintended consequences.12 The impact on lung, heart health and birth weight will be measured by comparing the health of over 500,000 Bradford residents in the three years before and three years after the Clean Air Zone is in place.

The research will examine whether the impact is different for people from more deprived areas or different ethnic groups. We will look at whether the policy changes the way people choose to travel using surveys, and we will also conduct group discussions and interviews with key groups of people including businesses, transport companies, families, and pedestrians. These discussions will explore what may have helped or hindered the success of the policy and any unexpected effects. We will explore if the Clean Air Zone is good value for money, for example, do any improvements in health justify the costs.

Our findings, which will complement those of colleagues evaluating the London Ultra Low Emission Zone13, will allow us to judge the impact of these policies both in terms of health, but also how they interact with the social, economic and political contexts in which they operate. There is a moral imperative to reduce levels of pollution

to improve the health of city dwellers. There is also an imperative for researchers to work together with policy makers to build in rigorous and transparent evaluations of policies aimed at reducing pollution. We need to be open to learning what works and what doesn’t work, and to encourage ambition and innovation. By working together, we can create a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts.

1. Wright, J. et al. ActEarly: a City Collaboratory approach to early promotion of good health and wellbeing. Wellcome Open Res. 4, 156 (2019).

2. City of Bradford Metropolitan District Council; Joint Strategic Needs Assessment: The Population of Bradford District. https://jsna.bradford.gov.uk/documents/The population of Bradford District/1.2 Health Inequalities and Life Expectancy/Health Inequalities and life expectancy. pdf (2020).

3. Khreis, H. et al. Traffic-related air pollution and the local burden of childhood asthma in Bradford, UK. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 8, 116–128 (2019).

4. Pedersen, M. et al. Ambient air pollution and low birthweight: a European cohort study (ESCAPE). Lancet Respir. Med. 1, 695–704 (2013).

5. Warembourg, C. et al. Urban environment during earlylife and blood pressure in young children. Environ. Int. 146, (2021).

6. Binter, A. C. et al. Urban environment and cognitive and motor function in children from four European birth cohorts. Environ. Int. 158, (2022).

7. Vrijheid, M. et al. Early-Life Environmental Exposures and Childhood Obesity: An Exposome-Wide Approach. Environ. Health Perspect. (2020) doi:10.1289/ehp5975.

8. Clemente, D. B. P. et al. Prenatal and childhood trafficrelated air pollution exposure and telomere length in european children: The HELIX project. Environ. Health Perspect. 127, (2019).

9. Mebrahtu, T. F. et al. The effects of exposure to NO 2 , PM2.5 and PM10 on health service attendances with respiratory illnesses: A time-series analysis. Environ. Pollut. 333, 122123 (2023).

10. Mueller, N. et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in urban and transport planning related exposures and mortality: A health impact assessment study for Bradford, UK. Environ. Int. (2018) doi:10.1016/j.envint.2018.10.017.

11. Rashid, R., Chong, F., Islam, S., Bryant, M. & McEachan, R. R. C. Taking a deep breath: a qualitative study exploring acceptability and perceived unintended consequences of charging clean air zones and air quality improvement initiatives amongst low-income, multiethnic communities in Bradford, UK. BMC Public Health 21, (2021).

12. McEachan, R. R. C. et al. Study Protocol. Evaluating the life-course health impact of a city-wide system approach to improve air quality in Bradford, UK: A quasi-experimental study with implementation and process evaluation. PREPRINT, (2022).

13. Mudway, I. S. et al. Impact of London’s low emission zone on air quality and children’s respiratory health: a sequential annual cross-sectional study. LANCET PUBLIC Heal. 4, E28–E40 (2019).

• HIDDEN EMISSIONS FROM CONSUMER PRODUCTS

• VENTILATION

• SMART AIR QUALITY TECH FOR THE HOME

Shampoo, deodorant, moisturiser – no one thinks twice about regularly using these products, and many others like them, so embedded are they into our daily lives. Whilst these products are extremely popular and frequently used, they’re also a source of pollutants that are emitted into homes during use.

Sources of indoor air pollution that traditionally come to mind are cookers, wood burners, candles, airborne viruses, mould, and allergens such as pollen, pet hair and dust. But emissions from consumer products are often overlooked.

Defined as any personal care (cosmetic and hygiene) or household cleaning product that is available for the public to purchase for personal use, consumer products are frequent emitters of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). These are emitted as gases and are a significant component of indoor

pollution, but a class that often goes unnoticed. Our homes are full of unique mixes of VOCs, being dependent on occupant behaviours and ventilation. Anyone who breathes indoor air, which we do on average 90% of the time, will be exposed to a distinct mixture of VOCs that often differ between rooms, even in the same building. Some will likely be more vulnerable to the negative health effects of breathing indoor VOCs, for example the very young, very elderly, and anyone with a significant pre-existing respiratory conditions such as asthma. In addition, VOCs can react indoors to produce secondary products, and some of these are known to be harmful to health, such as formaldehyde and fine particulate matter.

Quantifying any possible negative health effects from consumer product emissions is not straightforward, in part because their formulations are

complicated and often undocumented. There are thousands of different consumer products on sale and each one has the potential to emit any number of VOCs. Even two products of the same type, but with different scents, will emit different VOC at different concentrations. For example, a body spray with a vanilla fragrance will have a different VOC emission to the exact same product with a fruity fragrance. Generalising how consumer product VOCs impact indoor air quality is near impossible, without products being tested for their emissions in the lab.

What we do know is that typically ethanol, propane, and butane are the VOCs found in the highest concentrations in UK homes, and these are commonly emitted from consumer products. Propane and butane are used as propellants in aerosol products; while it is well known that improper use of aerosol products is dangerous to health,

even appropriate use can result in high VOC concentrations accumulating in a poorly ventilated room. There is little data on the long-term health effects of exposure to common everyday levels of aerosol propellants, or indeed many of the other common VOCs used in consumer products.

Ethanol is used in thousands of products - it’s a cheap and readily available solvent. On labelling its often called ‘denatured alcohol’ or ‘alcohol denat’. Whilst there are many indoor sources of ethanol - baking bread, breathing, and alcohol consumptionconsumer products are a particularly large source. Fragrance compounds are also very commonly emitted and are the easiest type of VOC to detect without using specialist equipment - we can sense them with our noses. This doesn't necessarily mean they are present in high concentrations, however; they just happen to be the most noticeable VOC to us as we can smell them even in tiny amounts.

Asides from propellants, solvents, and fragrances, consumer products are formulated to contain preservatives,

emollients, UV blockers, conditioning agents, and other compounds which enhance product delivery, all of which can be emitted to air both during and after use. There is also the possibility of VOC contaminants such as benzene and toluene being present in trace amounts in bulk solvents such as ethanol. These VOCs have been classified as hazardous to human health and are banned in all consumer products, but sometimes still find their way onto the shelves by accident.

The role of ventilation

The simplest solution to reducing indoor air pollution is often thought to be by improving ventilation, either by opening windows or mechanically ventilating using extractor fans to move pollutants elsewhere. Whilst this is undoubtedly an important part of any good indoor air quality strategy, there are drawbacks to relying on it alone.

As some products are applied directly to our bodies, and sometimes the face, we will directly inhale a portion of the VOCs emitted before they can be removed from the room. We also have to consider that some homes do not possess adequate ventilation systems, be that a lack of windows to the outdoors or outdated and inefficient mechanical extraction. It is also not widely known that extraction systems have to be regularly cleaned in order for them to work effectively. Additionally, any VOCs that are ventilated outside will ultimately contribute to outdoor air pollution, so it is only a partial solution.

It is vital, therefore, that indoor pollutants such as VOCs are also addressed at their source. Whilst it is an overreach to tell people what to do in their own private homes, consumers do have a right to know how their purchases and behaviours are affecting their exposure to indoor pollutants, and this includes the use of personal care and cleaning products.

How can we tell if a product is a high VOC emitter?

Unless you’re looking to buy paint, varnish, or other decorating materials, then unfortunately you can't. DIY products have for years had a basic label showing VOC emissions (Low, medium high, very high), and there is evidence that the label helps to some degree guide consumer choice. For other types of VOC-containing products, at least in the UK, there is no labelling at all. Introducing this would be a quick and easy way for consumers to know what

they’re purchasing and using. The UK Clean Air Strategy 2019 floated the idea of a voluntary VOC product labelling scheme, but this could open the door to greenwashing, where companies make environmental claims with no scientific basis. To be effective, both labels and product testing procedures would need to be standardised and regulated. This would require the definition of what constitutes low, medium, and high emissions, and for the varying health and environmental impacts of individual compounds to be taken into account.

There are many descriptors used by manufacturers to boost the environmentally-friendly appearance of their products, and to make consumers feel that by using them they are being both environment and health conscious. Whilst eco labels may describe the provenance of ingredients, they are not indicative of the VOCs a product emits and cannot be used as a proxy for being clean or ‘healthy’ for indoor air. In fact, our research at University of York suggests that ‘eco’ products can emit more VOCs than those without green marketing claims. The indoor air quality impact of a VOC is the same regardless of the chemical’s source. For example, a fragrance compound derived from a natural plant extract is chemically identical to one that has been synthesised in the lab; biologically produced ethanol from crops is identical to petroleum produced ethanol, once it is released to air.

Where the responsibility lies for reducing indoor air pollution from consumer products is yet to be determined. Is it the responsibility of the occupant to control their behaviours around product use and ventilation, the manufacturers to reformulate with lower VOC content and provide testing and labelling, or the government to step in and regulate the maximum levels of VOCs that consumer products can emit? In reality, to effect long-term change, it will rely on all three. Right now, however, it’s up to consumers to take charge of their own indoor air quality by changing their consumer product buying and usage habits. In the absence of information, such as labelling, toxicology data, and government recommendations, they are left largely in the dark.

Our team analysed >9.2 million sensor readings across five schools over the 2021/22 academic year.

Scan the QR code to download the full report:

Gasp! Until recently, a lot of focus on air quality has been about the air outside, but more and more, people are thinking about what is happening in their own homes, and this is an area they feel they can, or should be able to, control. So what are they being offered and is the emerging tech as smart is it says it is?

Smart air conditioning (AC) AC units tend to draw in air from a room, either heat it or cool it as required, then release it back into the room.

Smart versions of these systems offer all the advantages of traditional AC but can be operated remotely through a tablet or smartphone. Some models can even be connected to virtual assistants like Alexa, Google and Siri, enabling voice control.

Such smart AC systems can be scheduled to run at specific times, target temperatures can be set and fan speed adjusted. A key selling point of this kind of tech is that a smart AC system will slow or stop once the target has been reached, using less energy and so saving money on bills.

On the negative side, these kinds of AC systems can be bulky and intrusive. A unit installed in a window can block light and views. Although AC units can be mounted to walls or windows and come in several sizes, this can also cause problems. The temptation is to install smaller, less intrusive units but an AC system needs sufficient capacity for the room in which it works, as an over-exerted unit can pump dirty air back into the room!

Some, but not all, AC units can run quickly and quietly. Then

there’s the issue of expected lifespan. Several smart AC units selfdiagnose faults. This kind of tech is obviously more expensive but means the unit is easier to maintain and likely to last longer than conventional models. The tech is an investment.

Even so, smart AC can be expensive – both to buy the unit in the first place and then in energy costs to run, especially in large rooms.

Given all this, the Midea 8,000BTU U-shaped Air Conditioner has proved very popular. It’s a fast, quiet and relatively inexpensive system that’s easy to install and use, with voice control through Alexa and Google.

But note that AC systems don’t necessarily improve the quality of air in the room. To do that needs a more specific kind of tech...

Air purification removes potentially harmful pollutants from the air, such as bacteria, dander from pets, pollen and volatile organic compounds. This is usually done by sucking air through a filter before releasing it again.

Smart versions of these systems often monitor air quality levels, providing useful data to the owner, and have automated functions that can make them more efficient. They can work in conjunction with other building management systems.

One impressive example is the sleek, lightweight Dyson Purifier Cool TP07, which includes a large fan and a magnetised remote control as well as app and voice control.

Purifiers such as this can remove invisible pollutants from the

A range of tech solutions have been launched recently that promise to improve air quality in the home. We asked InfoTech’s Simon Guerrier to investigate what those solutions are, and how much these promises stand up.

air. Yet often how clean the air feels – to breathe or against bare skin – is down to humidity.

Humidity – the concentration of water vapour in the air – can cause all sorts of health problems if it’s either too low or too high. More seriously, ventilation and AC systems often control temperature but not humidity, the result being to encourage

mould. Sadly, as some well publicised recent cases have made clear, spores from mould can present a serious hazard to health.

Systems that monitor and manage humidity can really help here. Most dehumidifiers work by drawing hot air over a lowtemperature coil that causes water vapour to condense and drip down – as water – into a removable container.

Smart dehumidifiers can run automatically to maintain a target humidity and provide useful data on air quality, while being easy to operate. As with smart AC systems, the ideal model is quickworking but quiet but another major issue is the size of the tank used to collect water. Obviously, the bigger that is, the longer the dehumidifier can run.

The Telegraph recently judged the Midea Cube to be the best smart dehumidifier on the market. As well as its smart tech features, this stylish device can hold 11 litres of water, but when not in use collapses down for easy storage.

There are two basic types of humidifier for adding moisture to a room:

• Ultrasonic humidifiers use high-frequency sound waves to produce a fine mist that adds moisture to the air. These kinds of humidifier tend to be smaller, quieter to run and don't need a filter – reducing the need for maintenance.

• Evaporative humidifiers aim a fan on a container of water to make it evaporate more quickly, producing humid mist. Such units tend to be bulkier, noisier and yet less expensive to buy than ultrasonic humidifiers.

The quick, quiet Levoit LV600S Smart Hybrid Ultrasonic Humidifier is a very popular model. The smart tech makes it easy to use, maintain and clean. It will even remind you when it needs cleaning.

These solutions are relatively large but some smart tech can be very small.

These are a simpler, cheaper alternative to smart AC. The sensors let you know – by sounding an alarm or sending an alert to your phone – when there are high levels of airborne pollutants. You can then respond by, for example, opening a window.

A commonly used type detects carbon monoxide (CO), which is an otherwise colourless, odourless but deadly gas. The Google Nest Protect detector is a market-leading smart device that features an industrial-grade smoke and CO sensor that will last for up to a decade. App control means any alert can be silenced easily, without having to stand on a chair. The main issue here is that smart sensors only alert you to the issue; you then have to deal with it.

Smart ventilation

Ventilation is different from air conditioning in that it draws fresh air from outside into the building to replace the stale air inside. In cycling the air in this way, any pollutants, smells etc in the building are discarded. These systems are also good at eliminating condensation.

Smart ventilation systems can operate automatically –responsive to factors such as indoor or outdoor air quality, or the number of people in the building at one time. Again, they can provide valuable data on air quality.

For all their advantages, whole-building ventilation systems can be a sizeable investment and specialist advice should be sought.

That said, on the smaller scale there are several good, smart ventilation systems available for single-room use. For example, the Vent-Axia PureAir Sense Smart Bathroom Extractor Fan is a relatively quiet and fast-working unit with automated functions and app remote control.

By Ronnie George, CEO of Volution

By Ronnie George, CEO of Volution

We may be forgiven for not thinking about the air we breathe when we are in the comfort of our own home, however this is to our detriment. While we may not see it, indoor air quality has an outsized impact on our wellbeing and major societal and economic repercussions.

Short-term health effects include irritation of the eyes, nose and throat, headaches, dizziness and fatigue. Longer-term consequences can include respiratory diseases, heart disease and cancer.

Researchers at the University of Oxford's Department of Psychiatry have found evidence that exposure to air pollutants may lead to depression, anxiety, psychoses and possibly even neurocognitive disorders.

There is no mortality statistic for the UK, however the World Health Organization states 3.8 million premature deaths worldwide are linked to poor indoor air every year (with another 4.9 million due to general air pollution).

Indoor air can be up to 50 times more polluted than outdoor air due to the myriad pollutants we’ve invited into our home – including Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), found in many products such as everyday cleaning supplies, carpets, paints and air fresheners; carbon monoxide and nitrogen dioxide from our gas stoves; tobacco smoke; dust mites that live in our bedding and other soft furnishings; building and insulation materials such as synthetic mineral fibres, asbestos and formaldehyde; and mould.

This is worsened by the recent but much-needed trend to insulate buildings. Heating and powering buildings accounts for 30% of the UK’s total energy usage therefore reducing the built environment’s carbon footprint is integral to the UK’s Net Zero agenda. Key to constructing buildings that are more energy efficient and have significantly fewer emissions is insulation. The conundrum here though is the better insulated a building is, the more ventilation it needs because more

pollutants are trapped.

Poor indoor air quality can be found in all forms of buildings, however substandard housing intensifies the harm. A report from Shelter shows children living in sub-standard housing in the UK have up to a 25% higher risk of severe ill health and disability during childhood and early adulthood, as well as lower educational attainment and greater likelihood of unemployment and poverty. To put the issue in financial terms, poorquality housing in the UK leads to an additional £1.4 billion spent by the NHS each year.

By contrast, energy efficiency, combined with effective ventilation, is associated with reduced morbidities such as asthma and eczema and reduced blood pressure, sinusitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Putting it in financial terms, according to the Royal Academy of Engineering, £1.3 trillion over a 60-year period could be unlocked by ensuring buildings are fully infection resilient via ventilation.

As we learned during the pandemic,

ventilation is key to keeping healthy. However not all ventilation systems are equal and not all of them are up for the task of ventilating the new generation of well-insulated buildings. There are three main technologies, all ventilating continuously, which provide the best contemporary solutions.

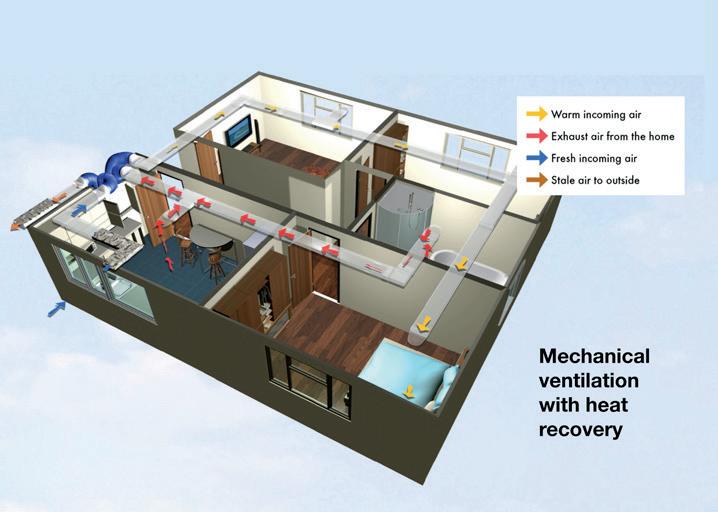

MVHR

(Mechanical Ventilation with Heat Recovery) is a whole dwelling, ventilation system delivering warmed, fresh and filtered air to the habitable rooms whilst reducing energy use and costs by recovering the heat from the stale extracted air. This is best suited to either new build or deeply renovated properties and more and more new houses are being fitted out with MVHRs however, at 30%, it’s still a minority.

MEV

(Mechanical Extract Ventilation) is a whole dwelling ventilation system that extracts air continuously at a low rate.

It is a low-energy, continuously running ventilation system designed with multiple extract points to simultaneously draw moisture-laden air out of all the wet rooms of a dwelling (bathrooms and kitchen) providing a quieter and more energy-efficient system compared to separate intermittent extract fans. This works well in renovation, where existing exhaust fans can be easily replaced to upgrade the ventilation system.

PIV

(Positive Input Ventilation) is an energy-efficient method of pushing out and replacing stale, unhealthy air by gently pressurising the home with fresh, filtered air to increase the overall circulation of air in the dwelling. This is ideal for refurbishment where there are no extract fans previously fitted and can be very quick and easy to install.

We have the tools to ensure buildings are well insulated, however we are still far away from ensuring healthy indoor air for all.

To date, there has been research by government and non-government groups, academia and corporates, however it’s just not enough. Indoor air isn’t a behemoth – the way pollutants interact with each other differs depending on the type of ventilation used, who are the occupants and how the building was constructed. Therefore all of these factors must be studied in different combinations so we can come up with the best solutions.

Optional initiatives for landlords, builders and tenants will not be enough to guarantee UK residents are safe in their own homes. What we need is a top-down approach that mandates the necessary level of ventilation – ideally continuous mechanical ventilation – for indoor safety and comfort.

The Decent Homes Standard, which is out for consultation, covers a set of standards across the rental sector. Currently, it does not specifically talk to or mandate ventilation. This is misguided as ventilation is integral to both quality

of life and a decarbonised building stock. The better way forward would be mandatory requirement for ventilation in line with the minimum requirements of Approved Document Part F (ADF) of Schedule 1 to the Building Regulations and in a number of specific building regulations. This is the only way to guarantee both new and old buildings meet the same standards.

The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government published ADF, which took effect in 2022 and requires that adequate ventilation is provided to guard against internal moisture build-up. Approved Document L (ADL) sets energy performance standards for new and existing buildings and has been modified to move away from intermittent extract fans to high-performing continuous extract fans and whole dwelling heat recovery systems.

Both ADF and ADL are due out for consultation later this year as part of the Future Home Standards from 2025, which has the aim of making all new homes built from 2025 emit 75-80% less carbon than homes built under the current Building Regulations. This is a step in the right direction but to maximise impact, ADF and ADL should

be developed together.

Moreover, what is key from Part L is an upgrade of the carbon reduction calculation SAP (SAP11), which sets the energy performance target each building must achieve. Crucially, the Government, through Part L, should ensure that SAP mandates mechanical heat recovery ventilation as the standard for new builds. It is by far the most efficient form of ventilation and, without it, Net Zero will not happen.

At the same time, the current version of SAP used for existing homes (RDSAP), now many years old, is no longer fit for purpose as it does not integrate modern ventilation equipment and heat recovery as part of a building’s carbon reduction strategy.

Then there is Awaab’s Law, driven by the tragic death of two-year-old Awaab Ishak. Awaab’s death was a completely preventable tragedy caused by the damp and mould in his home. This new amendment to the Social Housing Regulation Bill is important because it will crackdown on damp and mould and force landlords to investigate and fix serious problems within strict time limits.

While the biggest impact to our health would come from top-down

government regulation, I would also like to see more grassroots education targeting the general public. There is currently an All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for Healthy Homes and Buildings and there are some non-profits, such as Shelter, which are educating the general population about the risks of poor air quality. It is not enough though. The APPG must be strengthened and there must be more communication and education.

Lastly, the government needs to put more funding directed towards buildings. Currently, only 1% of buildings in Europe are being renovated on a yearly basis, but to hit our Net Zero target by 2050, we need to increase it to 3% per year. This will require government support. The Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund is helping, but without a fit for purpose RDSAP, the right decisions may not be made.

We all have the ability to make decisions in our best interests however sometimes the stakes are too, high. Just like seatbelts or smoke alarms, continuous mechanical ventilation must be mandated by the government for both new and old buildings. It not only will keep us safe but will be fundamental in the fight against carbon emissions.

By ClientEarth Lawyer Emily Kearsey

By ClientEarth Lawyer Emily Kearsey

At the end of June, the Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Act, known as the REUL Act, became law. This followed its tortuous passage through the UK Parliament amid outcries from legal and environmental experts that it could undo decades-old, effective environmental protections in the UK, including important laws tackling air pollution. Now that the ink is dry, we can take stock of what has actually happened and what this means for clean air and the environment.

What is the REUL Act?

When the UK government put forward the REUL Bill last year, its purpose was to revoke and amend a huge body of EU-derived laws that had been carried over into the UK’s

domestic law after Brexit and, in doing so, to reassert the sovereignty of the UK Parliament. These laws regulate a wide range of matters, such as the environment (including air quality), employment rights, and consumer protection and were known as ‘retained EU law’.

What did the government originally propose?

The UK government proposed that under the REUL Bill (now the REUL Act), ministers would be able to revoke, replace, restate or update any retained EU law, but in fact, contrary to what was promised, there would be very limited parliamentary oversight without any public consultation. The original bill also included a concerning provision that would result in the

automatic expiration of any retained EU law that wasn’t specifically ‘saved’ by the government by the end of 2023, under a ‘sunset clause’. It was also unclear which laws ministers were planning to keep. It was also plausible that some laws could be lost by mistake, given the short window of time that government departments would have to trawl through and assess what was estimated to be almost 5,000 pieces of retained EU law.

What’s happened since?

After months of parliamentary debate and advocacy from a broad range of coalition groups such as Greener UK, the UK government did scale back on the final form of the law. It did this by reversing the presumption in the Act, so that all retained EU law

would remain on the statute book, save for those set out in a specified schedule. However, fundamental issues remain despite government assurances that there will be no regression in environmental safeguards. Important elements of a key air quality regulation are set to be axed and a huge body of wider environmental laws remain vulnerable to being changed or lost.

During the parliamentary back and forth, the UK government conceded by removing its ‘sunset clause’ under which all retained EU laws would be scrapped at the end of 2023 unless saved by ministers. Instead, under the final REUL Act the government included a list of around 600 pieces of law on a ‘kill list’ that will be revoked on the 31 December 2023. All other retained EU laws will be kept for now, but are vulnerable to being changed or revoked until the end of 2026.

Up for the chop are important regulations designed to achieve cleaner air, specifically regulations 9 and 10 of the National Emission Ceilings Regulations 2018 (NEC Regulations). These laws require the UK government to prepare and implement a plan to show how legally binding emission reduction targets will be met across the UK and then to publicly consult on that plan. The targets themselves,

which cover five air pollutants that are harmful for human health and the environment, aren’t set be lost. However, the government will no longer be under any requirement to have a roadmap to show how it will achieve those targets or to let the public have their say on that plan.

The UK government has been doggedly refusing to acknowledge the importance of these rules. One of its chief arguments for their removal is that the rules are duplicative, and that the government’s Environmental Improvement Plan (EIP) contains much of the same information. This is misleading. While there is some content overlap between the two plans at present, the rules on what must be in the EIP are extremely vague, not nearly as comprehensive as those required under the NEC Regulations, and also don’t relate to the majority of pollutants covered by the NEC Regulations. While the government could choose to include such information in the EIP going forward, this would be at its complete discretion and without any requirement to seek the public’s views on its plans.

The loss of these laws would seriously undermine confidence that the UK government’s overarching emission reduction targets will be met. The need for a robust and transparent roadmap for reducing these emissions is particularly stark given that the government is currently way off track, having missed one target in 2021 and being off track to meet future targets for four out of five of the relevant pollutants. No coincidence perhaps that the government wants to be freed of the laws that require them to properly plan to fix this situation.

Scrutinising and debating changes to the law is the proper role of parliament. Under the final REUL Act, UK government ministers have granted themselves far reaching powers to change or remove any remaining retained EU law (i.e. what wasn’t on the kill list) until the end of June 2026. This means that the government can spend the next few years cherry picking and changing EU derived laws of all colours, more or less as it pleases. Parliament’s role in scrutinising changes to retained EU law has been sidelined. Voters, their elected MPs and devolved legislatures will have little say about long-standing laws, some of which have been in place for

decades. It also contradicts the notion that the REUL Act would reassert the sovereignty of Parliament. It is government ministers who hold the power now.

The weakening of the NEC Regulations is an example of how the REUL Act is already leading to environmental regression. However, more could be on its way.

Because of the powers granted to UK government ministers, the REUL Act also leaves wider EU-derived environmental protections vulnerable. For example, the fate of the majority of the UK’s air quality legislation (a lot of which is retained EU law) now hangs in the balance, alongside all sorts of other environmental safeguards, such as habitats and water quality protections. Efforts were made to require the government to include a safeguard against environmental regression in the Bill, but this was unsuccessful.

The possibility of further regression looks more likely because the Act provides that any regulation that replaces retained EU law cannot increase the regulatory burden. This effectively prevents such regulations strengthening environmental standards, since enhanced environmental protection usually involves controls over what public and private bodies can and cannot do and increases the likelihood of environmental protections being watered down. Accordingly, a de-regulatory approach has been baked into the Act, reducing the tools available to government to meet its own environmental targets.

All of this leaves EU-derived environmental protections in a precarious position for the next few years, during an air pollution public health crisis and environmental planetary emergency.

Most urgently, the UK government needs to rethink its position on the NEC Regulations and use the specific and straightforward powers in the REUL Act to remove them from the kill list before the end of October, maintaining the robust framework that the NEC Regulations provide.

Furthermore, ministers must hold true to the assurances they gave during the Bill’s final stages through parliament so that other environmental protections are not diminished.

Improving active travel provision brings emissions down, improves air quality and promotes healthier lifestyles. Martin Guttridge-Hewitt asks the woman responsible for cycle culture in the world’s bike capital for some life lessons.

In 2019 the Dutch made 4.8bn trips by bicycle, covering 10.9bn miles. Every resident rode 1.8miles each day that year, totalling 680 miles per person. This dwarfs figures in the UK, where the total distance cycled for the same period equated to just 54 miles per person.

Suffice to say, then, the Netherlands has a lot to teach us when it comes to encouraging bicycle uptake, and there are few places better to start learning than Utrecht. A picturesque town, at the start of this decade it completed a major engineering project, converting the Catherijnesingel canal back into a waterway, bringing to an end its 50 year stretch as an emissions spewing 12-lane motorway.

Now lined with wildflowers, it plays into biodiversity goals and, by cutting traffic, contributes to air quality improvements. Notably, restricting capacity for cars hasn’t increased congestion, either. This is for a number of reasons, including Utrecht’s exceptional cycling infrastructure. Residents don’t really need to look beyond their bikes to commute, a masterplan the city has been working on for almost 150 years.

Maliebaan, a short stretch of park-side cycleway, first opened in 1885 as the first bicycle path in the Netherlands. The first major undertaking of the Algemene Nederlandsche Wielrijders-Bond (Royal Dutch Tourist Association),

established two years earlier by a group of cyclists, it laid the foundations for what we see today. According to the 2022 Global Bicycle Index, Utrecht is officially the most cycle-friendly city on the planet, and Belle de Gest is understandably proud of that.

‘I’m in a nice situation, if I go to the local government everybody, or almost everybody, can see the importance of a bike. That makes it much easier to find money and support’.

A celebrated racing cyclist, this summer de Gest became Utrecht’s Bicycle Mayor, joining the global Bicycle Mayor Network launched by Dutch NGO BYCS in 2016 to support community-led urban change through cycling. As much about awareness, policy and publicity for active travel as knowledge-sharing, representatives want to engage with relevant organisations in other parts of the world to improve cycling provision.

‘I think we can all learn from each other – Utrecht is doing a lot of good things, and almost everywhere else can learn from this, but it’s not that we can’t improve too,’ says de Gest, citing safety as a big concern in the Netherlands, where ‘helmet culture’ is not as prominent as elsewhere.

‘But it’s difficult, in Utrecht, and the Netherlands, we have

real cycling societies, everybody is used to it. In the UK, you can’t just copy what we do because it’s not so much part of the culture.

‘I would say to anyone it’s important to work together with big companies and the local government,’ she continues, explaining the role of Bicycle Mayor means liaising with municipal authorities but being independent from them. ‘It can be difficult when you are trying to work alone… I’m in a nice situation, if I go to the local government everybody, or almost everybody, can see the importance of a bike. That makes it much easier to find money and support.’

As de Gest explains, a proven way of engaging with the private sector is through incentivised cycle to work schemes, which in the Netherlands often means making it financially beneficial to commute by bike. Simply put, getting more people to leave the car at home each morning is all about behavioural change, and that becomes far easier when individuals have something tangible to gain. ‘You can say to your friends, it’s good to go by bike for CO2 pollution, or the children, but they can easily think ‘that’s not my problem.’ It’s important to look at it in other ways, like what benefits them.

health and bikes and how we can reduce high costs in the health sector [through more active lifestyles],’ de Gest says. ‘In the Netherlands, most people still go to work by car, and it’s not realistic for everyone to go by bike, but the challenge is image. Like in the UK, here it’s cool to have a nice car, and often a sign of a good job, your job may even provide the car. I don’t know how exactly, but we need to make the bike cool, and deliver messages about the future - like your health, and children.’

A relatively recent phenomenon in the Netherlands as a whole, de Gest’s third point relates to falling cycling rates among younger age groups since the turn of the 21st Century. In 2008, 79% of Dutch children aged between nine and 11 cycled to school independently. Today, that has plummeted to 54%, a drop attributed to two things: increasing concern about cars and drivers, and more general worries over safeguarding vulnerable minors.

And it’s not just the number of actual commutes. According to road safety organisation VVN, fewer Dutch kids are taking cycling tests, too, suggesting numbers will continue to decline in coming years.

Clearly, then, de Gest has plenty to do. As do