The South Side Weekly is an independent non-profit newspaper by and for the South Side of Chicago. We provide high-quality, critical arts and public interest coverage, and equip and develop journalists, artists, photographers, and mediamakers of all backgrounds.

Volume 12, Issue 17

Editor-in-Chief Jacqueline Serrato

Managing Editor Adam Przybyl

Investigations Editor Jim Daley

Immigration Project Editor Alma Campos

Senior Editors Martha Bayne

Christopher Good Olivia Stovicek

Jocelyn Martinez-Rosales

Community Builder Chima Ikoro

Public Meetings Editor Scott Pemberton

Interim Lead

Visuals Editor Shane Tolentino

Director of Fact Checking: Ellie Gilbert-Bair Fact Checkers: Ella Beiser

Patrick Edwards

Christopher Good Jinny Kim

Lauren Sheperd

Rubi Valentin

Layout Editor Tony Zralka

Executive Director Malik Jackson

Office Manager Mary Leonard

Advertising Manager Susan Malone

The Weekly publishes online weekly and in print every other Thursday. We seek contributions from all over the city.

Send submissions, story ideas, comments, or questions to editor@southsideweekly.com or mail to:

South Side Weekly

6100 S. Blackstone Ave. Chicago, IL 60637

For advertising inquiries, please contact: Susan Malone (773) 358-3129 or email: malone@southsideweekly.com

For general inquiries, please call: (773) 643-8533

Cover by Gaby FeBland

Last July, the killing of Sonya Massey by a police officer downstate placed police responses to mental health calls in Illinois in the national spotlight. Though it took place nearly 200 miles away, the shooting echoed loudly in Chicago, where officers respond to hundreds of mental health-related calls per day.

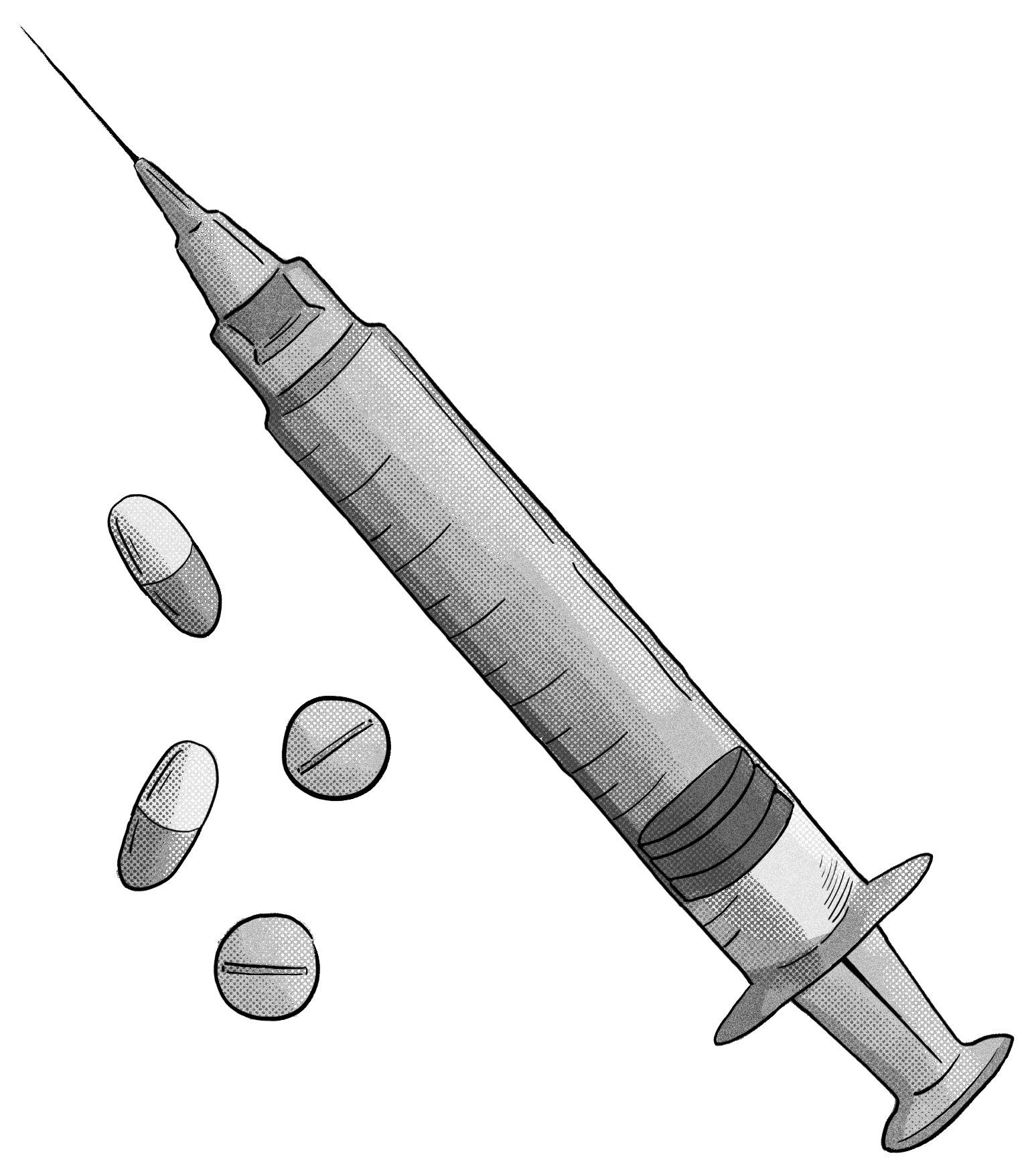

These calls range from mundane complaints about loitering to those that elicit a SWAT response. Some end in arrest. Sometimes the caller agrees to go to a medical facility. But our investigation shows that officers are increasingly strapping residents to gurneys and forcing them into ambulances, then hospitals. Experts we interviewed say it has become the “default” response.

Though it’s hard to find reliable data, it’s not just happening in Chicago. And with the mounting mental health crisis and an executive order from the White House to force unhoused people into institutions, it’s bound to become a more and more popular choice.

For the last two years, the teams at the Invisible Institute and MindSite News dug into data from the Chicago Police Department to find out just how often the police are hospitalizing Chicago residents—more than six a day last year. We also wanted to know how these often violent interactions play out in the real world. Are the people who get hospitalized helped? And what happens once the police leave? Too often, it can be a trauma that continues to haunt people and undermine their mental health.

For this special issue, we wanted to look at the whole mental health landscape in Chicago. We enrolled student journalists from Medill Investigative LabChicago, who spent six months diving into the CARE unit, the city’s alternative crisis response team that police were removed from last year. They also looked into what happens when police respond with force to a growing number of those mental health calls per day. And they explored Crisis Intervention Team training, a widely-used effort designed to help police better recognize and respond to people experiencing a mental health crisis.

Hopefully, this package can serve not only to document growing problems, but as a springboard for thinking through solutions—starting right here on the South Side.

Thanks for reading, Josh McGhee Chicago Bureau Chief, MindSite News

crisis response in turmoil: chicago’s care program at a tipping point

Bureaucratic dysfunction and fading federal support threaten its survival.

rachel heimann mercader, claire murphy ......................................... 4

expiring federal funds threaten chicago’s alternative crisis response effort

Chicago will need to dig deep to sustain and expand the CARE program, but state funds could offer hope.

janani jana and nicole jeanine johnson .......................... 7

paramedics out, emts in: chicago care program caught in labor crossfire

According to the Chicago Firefighters Union, CARE crisis response teams are ill-equipped to handle medical emergencies when EMTs are substituted for fire department paramedics.

charlotte ehrlich ................................. 9

from the elevator to the floor in eighteen seconds

When Chicago police fail to de-escalate mental health emergencies.

maggie dougherty and skye garcia 11

despite crisis training, many chicago police officers still resort to force in mental health crises

Last year, 169 police officers who received training used force at least once during a mental health-related incident in Chicago.

emma sullivan ....................................... 15 shadow arrests

Thousands in crisis get involuntarily hospitalized despite little evidence of effectiveness.

josh mcghee, dana brozost-kelleher, isabelle senechal, sam stecklow, jenna mayzouni, allende miglietta, stephana ocneanu ................................ 18

Credits

Stories on CARE and the use of force were produced by the Medill Investigative Lab-Chicago at Northwestern University. Medill students Janani Jana, Rachel Heimann Mercader, Claire Murphy, Maggie Dougherty, Skye Garcia, Nicole Johnson, Rachel Yoon, Tyler Williamson, Jai Indra, Charlotte Ehrlich, Emma Sullivan, Margarita Williams, Sam Biggs, Hope Moses, Ashley Quincin, Jasmine Kim, Mariam Cosmos, Tom O’Connor, Sara Cooper, Sin Yi Au, Christiana Freitag, Mitra Nourbakhsh, Angeles Ponpa, Nora Rosenfeld, Britton Struthers, Arthi Venkatesh, and Sarah Xu contributed. The lab is led by Medill assistant professor Kari Lydersen; Medill assistant professor Matt Kiefer’s students led data analysis and visualization.

The story on involuntary commitments was produced by Invisible Institute and MindSite News. Josh McGhee of MindSite and Dana Brozost-Keller, Isabelle Senechal, and Sam Stecklow, of Invisible Institute reported the story, along with Medill externs Jenna Mayzouni, Allende Miglietta, and Stephana Ocneanu.

Project edited by Rob Waters, Josh McGhee, Kari Lydersen, Andrew Fan, Diana Hembree, and South Side Weekly editors.

Fact-checked by South Side Weekly’s Ellie Gilbert-Bair, Ella Beiser, Patrick Edwards, Christopher Good, Jinny Kim, and Lauren Shepherd.

in pittsburgh, involuntary psych hospitalizations do more harm than good

“The real thing to do is that, if you’re in doubt, then discharge the person.”

venuri siriwardane, pittsburgh’s public source 24

public meetings report

A recap of select open meetings at the local, county, and state level.

scott pemberton and documenters 27

Chicago’s mental health crisis teams were meant to replace police with clinicians. Bureaucratic dysfunction and fading federal support now threaten their survival.

BY RACHEL HEIMANN MERCADER, CLAIRE MURPHY

Originally published by MindSite News, Chicago Sun-Times, and South Side Weekly on July 25.

On a chilly afternoon in October 2023, a single mother stood in her living room on Chicago's North Side as her teenage daughter erupted in rage, kicking, screaming and threatening to take her own life.

The mom, Pamela, was frozen, phone in hand, caught between a daughter having a mental health crisis and a system that previously had failed them.

A few years earlier, she says, her daughter had been outgoing. Good in school, she loved sports and had plenty of friends. But as an adolescent, her moods grew darker, her behavior volatile.

Amid her mental health struggles, Pamela—whose last name is being withheld to protect her daughter's identity—was left grasping for support.

When she needed help for her daughter and called 911, police officers responded, and that usually left her daughter shaken. At times, she says, the police acted aggressively—raising their voices, getting too close, putting their hands on the girl, making things worse.

“When you have a dysregulated human, and you escalate, most often, that human will continue to escalate,” Pamela says. “Having the police come in and out of your house is very traumatizing.”

So this time when she called 911, she asked for the Crisis Assistance Response and Engagement or CARE team—a program created in 2021 to offer clinical help in a mental health crisis and limit police involvement. Within a few minutes, a van carrying a mental health professional,

paramedic and police officer pulled up to Pamela’s home.

“When the CARE team came in, they were trained, and they knew how to calm the situation in a very professional, respectful way that my daughter was able to respond to,” Pamela says.

CARE became a lifeline, assisting her daughter, now nineteen, at least six times over the past four years and bringing stability to moments that once spiraled out of control.

But that, increasingly, is not the way the program is working. A six-month investigation by Medill Investigative LabChicago and MindSite News found that CARE teams are responding to fewer and fewer mental health calls, that police are responding to the vast majority, and that the overall effort is hampered by dysfunction and bureaucratic infighting.

Operators answering 911 calls are dispatching CARE teams to mental health calls less frequently—a sign, former CARE

staff members say, that dispatchers and first responders have lost confidence in the program.

Another hurdle looms, too: The federal COVID recovery funds that have paid for most of the program's operations to date will run out next year. Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson said in a statement sent to Medill and MindSite News that he is committed to funding the program with city dollars and ultimately expanding it.

A movement emerges, and recedes

The use of mobile crisis teams to respond to mental health crises expanded nationally during the reform movement that intensified after a white Minneapolis police officer murdered George Floyd, a Black man, during an arrest. But today, many cities are struggling with increasingly uncertain funding and staffing shortages.

In Eugene, Oregon, CAHOOTS— the country’s most celebrated crisis response

program—shut down this year. New York’s B-HEARD program has been mired in controversy, and responds to only a fraction of eligible calls. And federal budget cuts to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) are worrying operators of mobile crisis programs nationwide.

“I think everyone’s concerned right now,” Dr. Margie Balfour, chief clinical quality officer of Connections Health Solutions in Arizona, told Behavioral Health Business. “SAMHSA block grants fund a lot of this work. We’re definitely keeping our eye on that, but it’s hard to know what we’re facing just yet.”

What began as a bold experiment in public health is now at risk of becoming a cautionary tale.

In Chicago, calls to reform the mental health system long predated the launch of the CARE program. Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s decision to close six of twelve city mental health clinics in 2012 spurred citywide protests.

Advocates worried the closures would disproportionately affect underserved communities, many of whom relied on these clinics for mental health care and a sense of community. City officials said the clinics would be replaced with higherquality private care through partnerships with more than sixty clinics, saving millions of dollars.

But vulnerable populations bore the brunt of the drop in access to care, increasing the likelihood that those suffering a mental health-related emergency would be met with police force rather than medical

treatment, advocates say.

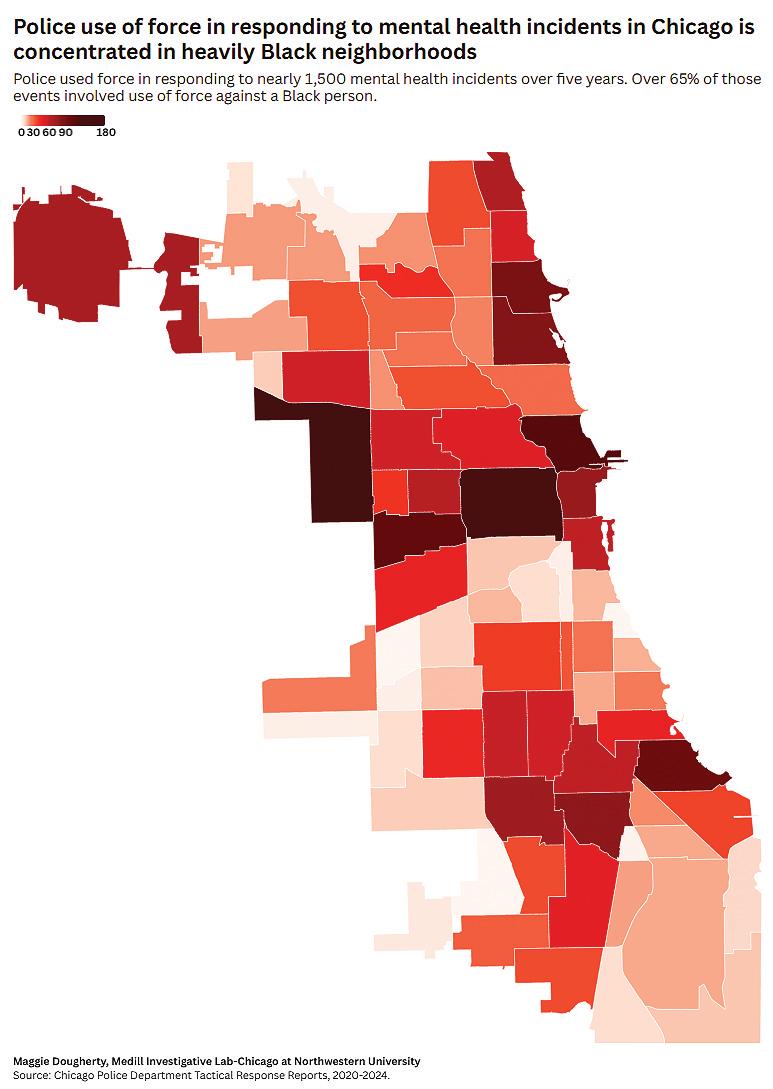

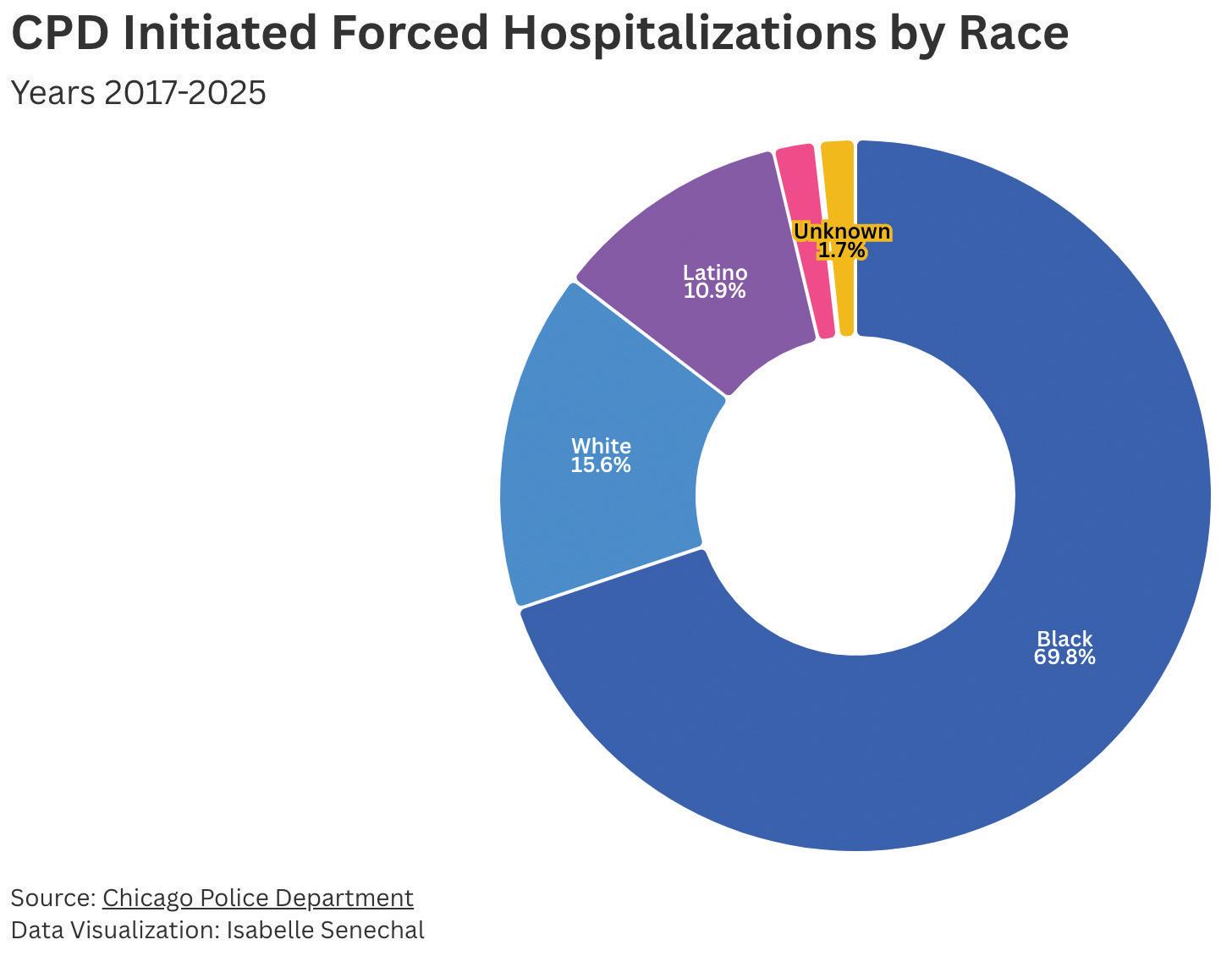

Indeed, as Medill and MindSite News previously reported, during almost the same period—August 2020 through August 2024—Chicago police used nonfatal force including taser, batons and nonfatal gunfire against more than 150 people following mental health-related calls to 911. Police also fatally shot one person in the midst of a mental health crisis, according to a Washington Post database. These encounters disproportionately affected Black people, who comprise 27 percent of the population but experienced two-thirds of the use-of-force incidents.

The push for reform accelerated in 2020. The Collaborative for Community Wellness—a coalition of mental health professionals, community-based organizations and residents—launched the “Treatment Not Trauma” campaign, demanding a citywide crisis-response system that didn't rely on police and a plan to reopen the shuttered clinics.

Pushing for care, not punishment

In September 2020, Ald. Rossana Rodríguez Sánchez (33rd) introduced an ordinance calling for a move to non-police responses.The proposal, she later told Medill and MindSite News, reflected demands from Black and brown communities "that people experiencing mental health issues are met with care, not punishment.”

Opponents on the council and in the police union opposed the proposal as a move to "defund the police."

CARE was then-Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s compromise: a two-year pilot involving teams of police officers, paramedics and mental health clinicians. Some activists opposed police involvement, but then-Police Supt. David Brown said officers would provide safety.

Including the police “was a really bad idea, and we fought against it,” says Arturo Carrillo, a founder of the Collaborative for Community Wellness and deputy director of health and violence prevention with the Brighton Park Neighborhood Council.

The CARE pilot launched in September 2021 with a $3.5 million budget, and its limitations were clear from the start. It operated in only a handful of neighborhoods between 10:30 a.m. and 4 p.m.—not what reform advocates had envisioned.

From the start, researchers at the University of Chicago's Health Lab—

which was commissioned to evaluate the pilot—saw serious challenges stemming from the need for police, fire and health department officials to collaborate. The agencies clashed over authority and approach, as well as seemingly mundane issues such as coordinating uniforms and meal breaks, said Jason Lerner, director of programs at the Health Lab.

Insiders agree, and say turf battles have hampered the program.

“There was a fight between the three entities” —police, fire and health—says one former CARE worker who spoke on condition of anonymity. "Who’s gonna be in charge? There was no real collaboration.”

That made it difficult to do the job effectively and made interdepartmental interactions feel “very quid pro quo—very ‘you do me a favor, I do you a favor,'" said former CARE clinician Patrick Cornelius.

“That was part of the learning curve for the city,” Lerner said. “People look at CARE and think, ‘Why isn't it responding to more calls? Why isn't it more widely available?’ But from my perspective, that's the reason you have pilots.”

When Brandon Johnson took office in 2023, mental health reform was key to his agenda. He promised to reopen closed clinics, expand CARE's hours and phase police out of CARE operations. Johnson has long been an outspoken advocate on the issue, having lost his brother to struggles with mental health.

Last September, Johnson's office announced that CARE had transitioned to a non-police model and was being moved from the police department to the health department. He framed the change as a major step forward.

“By directing 911 mental health calls to public health teams, we are ending the criminalization of these issues,” the mayor said in a statement. “I am pleased that (police and firefighters) can transition back to their primary roles of protecting community safety and responding to medical emergencies.”

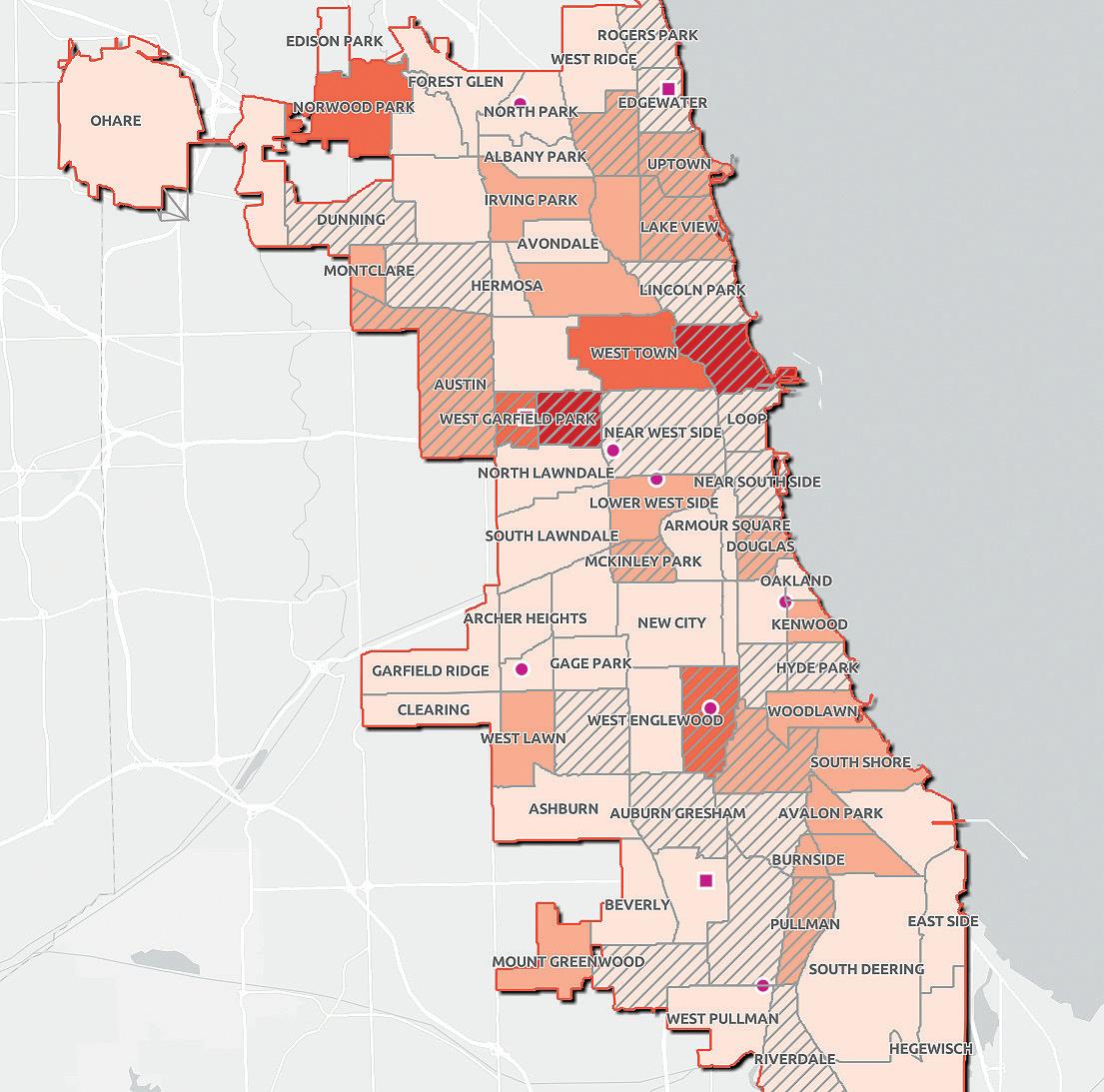

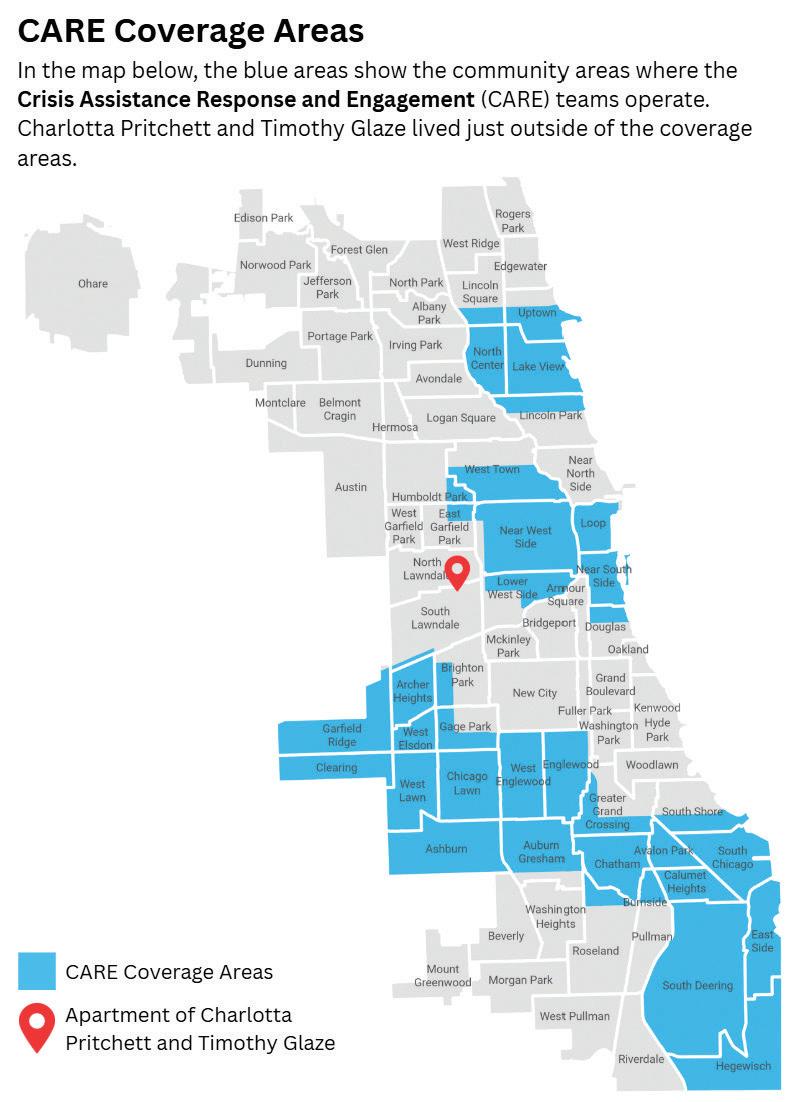

Today, seven CARE teams— composed of a mental health clinician and an emergency medical technician— respond to low-risk 911 calls involving mental health issues in specific police

districts, mostly on the south and west sides, as well as Uptown, the Loop and several other North Side neighborhoods. One team can respond citywide.

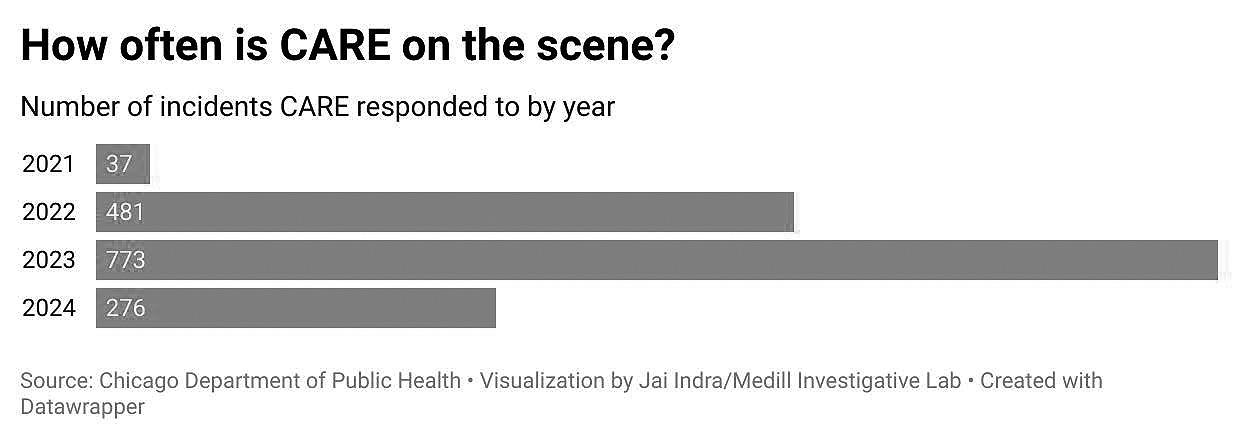

Health department call logs obtained by Medill and MindSite News show a slow rise and then an abrupt decline in the number of calls handled by CARE teams: They responded to 37 calls in 2021, 481 in 2022 and 773 in 2023. Then, amid Johnson's 2024 restructuring, that number plummeted to 276.

This year, preliminary data show, CARE teams appear to be going on calls at roughly 2023 levels, but with a significant difference. When a CARE team responds, they are most often doing so after team members hear a radio call that police are already responding to.

Police are responding to the vast majority of calls designated in public records as CARE calls, mostly alone but sometimes alongside separate CARE clinical teams.

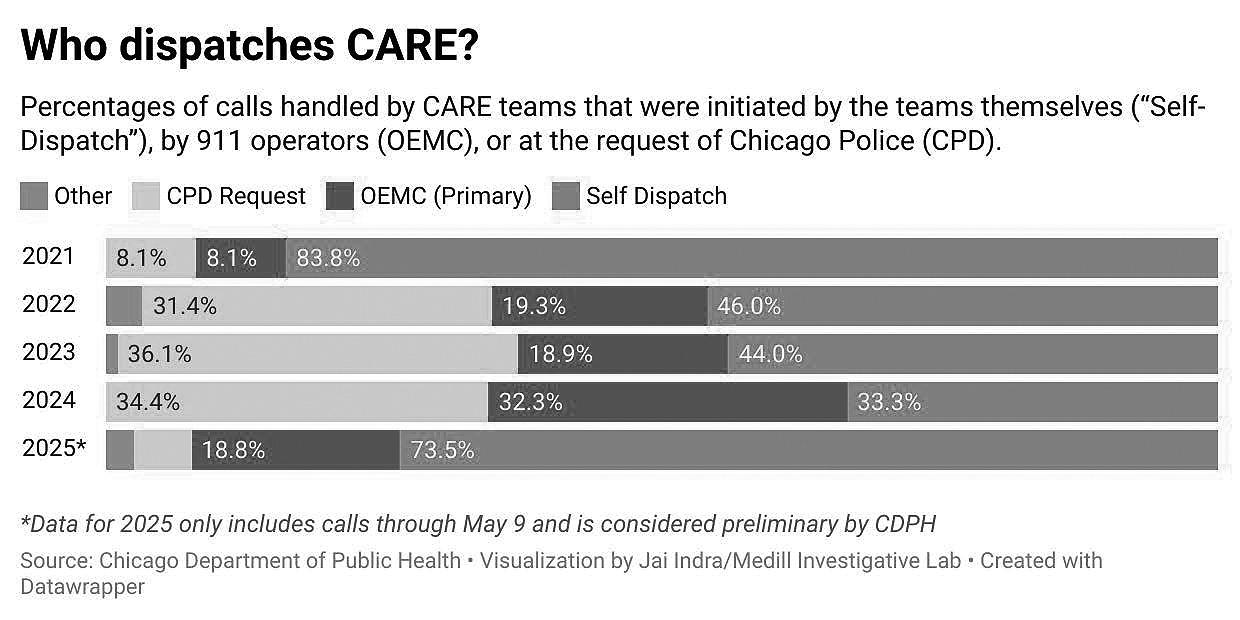

Since only the police can transport people to a hospital against their will, 911 operators often are reluctant to dispatch CARE teams. That frequently leaves CARE team clinicians sitting in their offices unsure what to do, a former staffer said. And since CARE vans operate without sirens, it takes them longer than police to get to a call.

In 2021, only 8 percent of CARE responses were initiated by 911 dispatchers. That number rose to 19 percent in 2023 and 33 percent in 2024, according to health department data.

After the police were removed from CARE teams in October 2024, the portion of CARE responses initiated by 911 dispatchers fell from 46 percent in September to just 9 percent in December, while the portion of responses the CARE team initiated on its own rose from 29 percent to 86 percent.

The number of police calls for CARE assists also plummeted, from 62 percent of all CARE responses in August 2024 to just 5 percent in December 2024.

By another metric, CARE teams responded to fewer than 1 percent of 96,000 calls that 911 dispatchers categorized last year as potentially mental health-related.

The mayor's office said in a statement to Medill and MindSite News that city officials are “aware” of these numbers and working to “develop solutions so that the

CARE team is dispatched more frequently to meet the need for mental health services."

The mayor is also appointing a committee to include his policy chief, Jung Yoon, and unnamed department heads, alders and community partners to develop an "action plan within the next 45 days“ to take corrective actions and address concerns.

In the program’s early days, the criteria for dispatching CARE changed frequently, said CARE clinician Drake Schoeppl, leaving dispatchers confused about which calls qualified.

“A lot of dispatchers were scared because they didn’t want to get in trouble” if a situation became violent, he says.

The health department wants 911 operators to deploy CARE teams more often, rather than the teams selfdispatching, says Dr. Jenny Hua, Chicago’s interim deputy commissioner for behavioral health, but it's a hard call since dispatchers are supposed to be sure there’s no crime or medical emergency.

“We have investigated very, very, very, very, very thoroughly” why CARE is dispatched so infrequently, Hua says. In part, it results from having "a program that is meant to meet mental health needs sort of rubbing against the necessities of a 911 system that is designed to encounter emergencies.”

Hua says calls that have "nothing but a mental health component” and are clearly eligible for CARE are “a needle in a hay stack” of 911 calls.

The mayor’s office concurred. “The 911 system must assume the worst, because they don’t want emergencies missed," its statement said. "A person could be lying on the street because of a heart attack, or an overdose, or a schizophrenic episode. In a medical emergency, a paramedic is the default first responder. In a violence-related call, police is the default.”

City records show CARE teams have responded to a wide range of settings with success.

In one case, CARE clinician Drake Schoeppl says, a woman barricaded inside her home because she thought the FBI was coming. Police surrounded the house for thirty minutes. When Schoeppl intervened, he listened without challenging

This map shows concentration of potentially mental health-related 911 calls and areas served by CARE. Community areas with cross-hatching had 5 or more CARE responses in 2024. Darker colors indicate a higher number of mental health-related 911 calls. The city’s public mental health clinics are represented by pink dots, and libraries with public mental health services are represented by pink squares. ARC-GIS mapping by Kelsey Rydland, Northwestern University Librarian

her delusions.

“Cops a lot of times can get really impatient, don’t want to deal with it, or they don’t know how to deal with it,” he says.

Eventually, he says, she walked out on her own and agreed to go to a hospital for help—the kind of outcome CARE aims for.

In another case, in February 2023, a sixty-six-year-old woman was walking in traffic, incoherent and underdressed in freezing weather. CARE clinicians got her the hospital care she needed, records show.

About one-quarter of CARE calls in 2024 resulted in the person being taken to a hospital emergency department for evaluation.

Krista Murphy, a clinical social work lead in the psychiatry emergency

million through this year. But that money will be mostly spent this year and must be fully spent by the end of next year, leaving a major gap in subsequent years.

Despite that challenge, Johnson "is committed to continued funding of the CARE program using city Corporate dollars," his office said. "Even in a difficult budget year, CARE is a priority for the administration and Mayor Johnson will do everything in his power to expand resources for the program."

His primary focus now, the statement said, is "effective implementation before we begin to plan for future expansion" that would grow the program's geographic footprint and expand it to daily, round-theclock operation.

Budget talks for fiscal year 2026 begin in August, and Rodríguez Sánchez is adamant that the city continue funding CARE. “To those who say CARE isn’t working: the truth is, we haven’t given it the full scope of resources or structure to thrive,” she says. “We can’t walk away."

Pamela, the North Side mother, says CARE teams have helped de-escalate her daughter's crises, connected the family with resources and helped them develop a plan.

“If CARE hadn’t come into our lives, I think things would have been much worse,” she says. "I think I would’ve been led down a different path, instead of focusing on her wellness."

She worries what might happen if the CARE teams disappear or their roles become limited.

department at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, says police officers or paramedics who bring people with mental health symptoms to the ER "aren't able to really speak to their clinical symptoms just because they don't have training in mental health.”

The mental health expertise of CARE workers, on the other hand, enables them to expedite assessments, allowing hospital staff to quickly determine whether psychiatric admission or alternative care is needed and benefiting patients, Murphy says.

Since the CARE program launched in 2021, the American Rescue Plan Act has been its biggest source of funds—$6.87

“I’m at the end of the road with this kid and the options available to her,” she says. “People with mental illness—they need help.”

Rachel Yoon, Janani Jana, Tyler Williamson, Jai Indra, Nicole Johnson, and Kari Lydersen contributed reporting.. ¬

Rachel Heimann Mercader is a freelance investigative journalist based in Chicago. She is also a graduate of Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism.

Claire Murphy is a freelance investigative journalist based in Chicago. She is also a graduate of Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, where she specialized in investigative reporting.

BY JANANI JANA AND NICOLE JEANINE JOHNSON

Federal pandemic relief dollars that help pay for a Chicago program that sends clinicians instead of police to mental health crises are expiring, and under President Donald Trump’s administration, new funds for mental health and police alternatives seem unlikely.

Mayor Brandon Johnson has pledged to expand the Crisis Assistance Response & Engagement (CARE) program citywide; currently it serves only a limited number of neighborhoods. But the likely end of federal support means the city will need to find millions of dollars to sustain it—and even more to pay for the proposed expansion. A state program that provides funding for mental health crisis services is a potential source to help fill the gap.

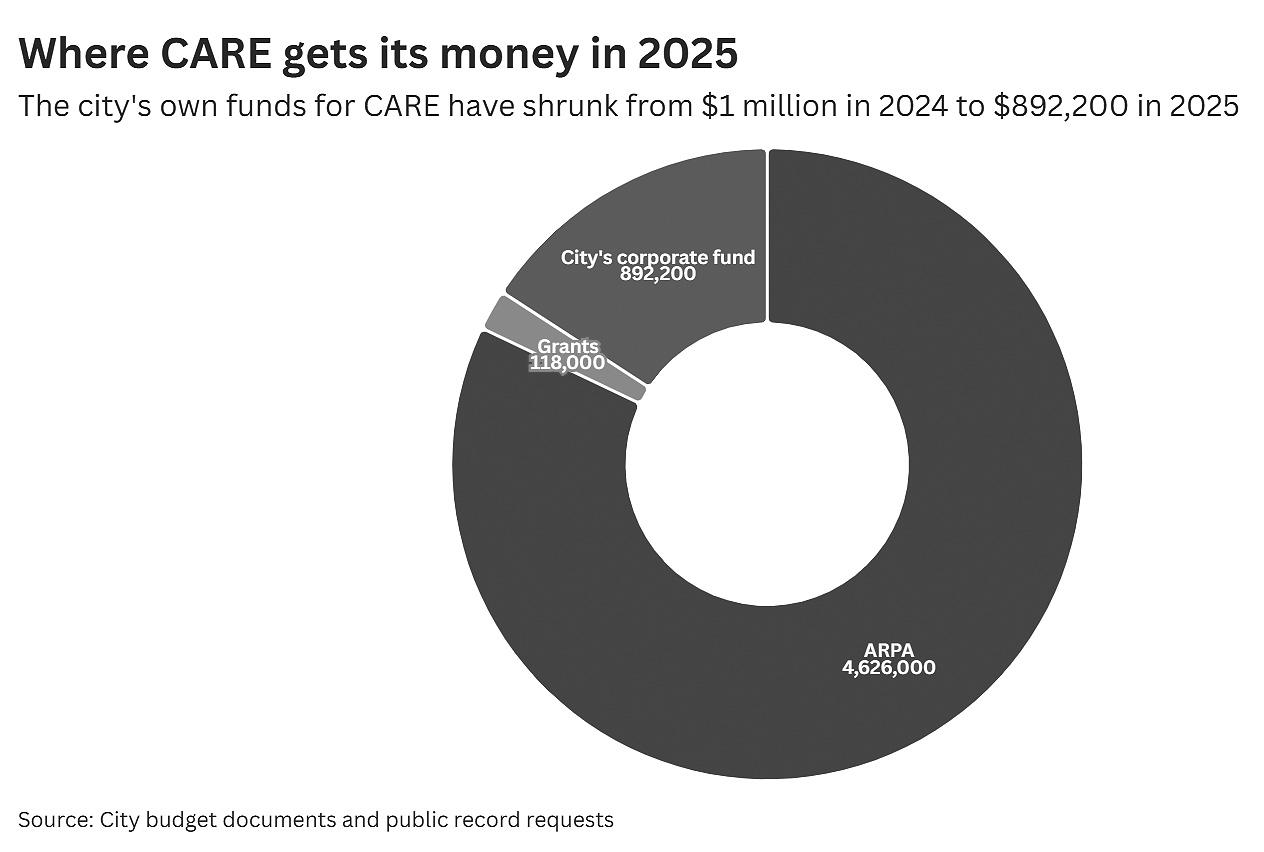

This year, more than 80 percent of CARE funding comes from the federal American Recovery Plan Act (ARPA), which provided COVID-19 pandemic relief, according to an analysis of budget documents by Medill and MindSite News.

“CARE is currently federally funded. And that funding is set to expire at the end of next year,” Dr. Jenny Hua, the medical director and deputy interim commissioner of behavioral health for the Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH), told Medill and MindSite News.

She added that a reduction in federal funding creates “a terrible crisis for not just the health department but for all city agencies.”

The city used $4.46 million in ARPA funding for CARE employee salaries and pensions in 2025. Just $892,200 was devoted to CARE from the city’s corporate fund, the main pot of city revenue. An additional $118,000 was carried over from the previous year’s CARE budget.

So, millions in expiring pandemic funds will need to be replaced in coming years just to maintain CARE at its current level of

service. In 2024, CARE responded to 239 calls, mostly in seven of the city’s twentytwo police districts, between the hours of 10:30 a.m. and 4 p.m.

There are currently fifteen police districts without CARE teams. Adding an additional team to each would cost about $9.75 million and expanding CARE service around the clock would cost about $7 million, according to the 19th Police District Council, an elected public safety body. 19th District Councilor Jennifer Schaffer said the figures are based on discussions with the mayor's office.

The Mayor’s Office did not respond to questions about the cost of citywide expansion or other questions about the CARE budget.

In a statement to Medill and MindSite News, a spokesperson for Johnson said: “Mayor Johnson is fully committed to putting forward a budget that maintains funding for the CARE program and for mental health services generally. In his first two budgets, Mayor Johnson doubled the funding for CARE and, in spite of the serious fiscal challenges that the City is facing, Mayor Johnson plans to maintain funding for the CARE

program while continuing to make reforms and adjustments so that the program can be successful and serve as many Chicagoans as possible within its current scope.”

CARE was launched as a pilot program in 2021, and in the 2022, 2023, and 2024 budgets, the city allocated $1 million a year for the program.

An additional $6.87 million of ARPA money has also been budgeted for CARE since 2022. All pandemic relief money must be spent by 2026 or returned to the federal government.

Hua said that ARPA funds allocated for CARE will likely be used up this year and that in 2026, CARE would tap ARPA dollars that were originally allocated to another health department program for housing stabilization. According to the city’s ARPA dashboard, less than ten percent of the stabilization funds have been spent, leaving $4.87 million seemingly available for CARE.

The city’s Office of Budget Management did not respond to queries

about such a reallocation.

CARE launched in 2021 as a joint program of the police, fire and public health departments under police administration. In September 2024, CARE was moved from the police department to the Department of Public Health and police officers were removed from the CARE teams. As part of the transition, the city reduced its reliance on contractors in favor of city employees, documents obtained by Medill show.

As of 2024, CARE had twenty-two fulltime employees including crisis clinicians, community intervention specialists, and Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs). Seventeen of them were assigned to the CARE team that year, with the bulk of their salaries paid with federal pandemic funds.

ARPA funds also paid for uniform allowances, office supplies, computer hardware, and communication devices.

In 2025, $500,000 in city funds were spent on paramedics who work with CARE clinicians and almost $300,000 was spent on gift cards used for Narcan, fentanyl test strips, and other supplies.

On a Saturday afternoon in May, Patrick Lindley sat at the back of a small room in McFetridge Sports Center on Chicago’s Northwest side for a meeting of the 17th Police District Council.

The Albany Park neighborhood where Lindley resides is not part of CARE’s coverage area, but there’s plenty of need for CARE response. More than 700 calls were made to 911 for potential mental health emergencies in 2024 from the Albany Park community, according to city data.

“I don't know how many of the folks that we have responding to 911 calls in our district are trauma-informed,” said Lindley, a community volunteer who would like

CARE to extend to his neighborhood. "An ounce of prevention saves a pound of pain.”

Alderperson Rossanna Rodríguez Sánchez (33rd Ward) agreed.

“What we are missing is the commitment to funding that is going to allow us to expand this in a way that our communities need,” she told the group. “This saves lives, this saves us money.”

State funding potential

Could state funds provide the lifeline that CARE needs?

A 2021 law called the Community Emergency Services and Supports Act (CESSA) funds programs similar to CARE that sends mental health workers instead of cops. In 2024, the state awarded almost $70 million through CESSA to county public health departments, hospitals and nonprofits, including some in Chicago.

A spokesperson for the Mayor’s Office said the city is looking to the 590 program as a source of funds for CARE, but the Illinois Department of Human Services (IDHS) told Medill and MindSite News that the program is not accepting new applicants for fiscal year 2026.

Hua said the health department is “in communication with the state to see if we're eligible to apply and if the application is open.”

Clinicians or police?

Schaffer, a member of the 19th Police District Council, said while she and other CARE proponents are not seeking to

According

"defund the police," they believe that unfilled positions built into the city's $1.8 billion police personnel budget could be used to help fund CARE.

In 2025, The TRiiBE reported that $170 million was budgeted for vacant police positions; advocates have called for those funds to be used for youth and public health programs. As of April, the department had vacancies for 142 police officers, seventyseven field training officers, and fifty-five sergeants, according to the Chicago Public Data Portal.

Expanding CARE would take mental health crises off the police department’s plate, freeing officers to do the work they are trained for, Schaffer said.

Budget discussions that began this month will help determine CARE’s future.

Rodríguez-Sánchez, Schaffer, and other leaders are urging the mayor and City Council to keep it going.

“If they don't find a way to fund it, it's going to go away,” Schaffer said.

“It is the mayor's job to hear what the community wants and figure out how to get it funded.¬

Janani Jana is an international journalist with multimedia experience in business, government policy, and data reporting. She’s a graduate of the investigative masters program from Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University.

Nicole Jeanine Johnson is an investigative journalist from Chicago, IL. She’s a graduate of the investigative masters program from Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University.

to the Chicago Firefighters Union, CARE crisis response teams are ill-equipped to handle medical emergencies when EMTs are substituted for fire department paramedics. But according to the city, the modification is required to maintain program staffing.

BY CHARLOTTE EHRLICH

Lack of enthusiasm from the fire department was among the troubles plaguing the CARE (Crisis Assistance and Response Engagement) program. Documents and interviews with former CARE staff reveal that CARE teams could often not be deployed to mental health emergencies because fire department paramedics who were part of the teams were unavailable.

But when the city decided to remove fire department paramedics from CARE and replace them with new emergency medical technicians (EMTs), the union representing firefighters fought back with an unfair labor practice charge and a grievance.

Union officials say the city’s decision to replace fire department paramedics with EMTs means CARE teams are less prepared to deal with medical emergencies, reducing the number of calls that CARE can handle. The city argued that EMTs are equipped for the work that CARE does, and as CARE is a relatively new program, the fire union has no contractual right to the work.

In June, an official arbitrator decided

against Chicago Fire Fighters Union Local 2 and in favor of the city in the dispute. Union president Pat Cleary said the union is dropping the fight for now, as “we’re hearing from the city that they’re going to disband the whole program, so we’re not going to waste our time.”

But Mayor Brandon Johnson’s office told Medill and MindSite News that the city plans to fully fund CARE, with budget discussions ongoing for the next fiscal year. And Cleary said that if CARE does continue, the union will “one hundred percent” revive its fight to include fire department paramedics on the teams.

Modeled after similar initiatives nationwide, the CARE pilot launched in 2021 deployed eight Chicago Fire Department community paramedics, more than twenty police officers with training in crisis intervention, and about half a dozen mental health professionals working for the public health department to neighborhoods with high rates of mental health-related 911 calls and emergency transports.

The fire department had trouble finding enough paramedics who wanted to work with CARE, according to a June 9 report by arbitrator Peter Meyers. Difficulty filling the eight slots for fire paramedics meant that CARE vans sometimes weren’t deployed. Meyers found that seventy to eighty fire department employees were eligible to take an extra training to work with CARE, but only four responded to the department’s multiple requests for volunteers, and two were ineligible while one was already assigned to CARE. However the University of Chicago Health Lab was contracted to do an evaluation of CARE, and noted that the fire department and police department were “enthusiastic partners” who contributed to the program’s success.

The fire department paramedics on CARE teams would conduct a brief medical assessment of the patient, taking vital signs to ensure they were not experiencing a medical emergency. If they were, the team called for a fire department ambulance; if not, the CARE team completed an assessment and determined where to transport the patient.

Fire department paramedics were still “riding on the CARE vans,” which the department donated to the program, when the union was notified on April 11, 2024, that the city had posted a job opening to hire EMT-Bs—a lower classification than the fire department paramedics—for the same vans.

Anthony Snyder, the firefighter union’s director of emergency medical services, says the EMT job posting came as a surprise, sowing anxiety and resentment. Less than two weeks later, the union filed the grievance and unfair labor practice charge.

A difference in training and capacity

Snyder emphasized that the fire department has “strict hiring guidelines” and only employs people qualified as EMTParamedics. When the fire department was removed from CARE, EMTs without the paramedic qualification—EMT-Bs—were hired in their stead.

Nationwide EMTs make a median annual wage of $43,000, according to 2023 data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The EMTs working for CARE currently start at $46,516 per year, according to public records obtained by Medill, whereas

union fire department paramedics earn over $62,000 a year, according to a city website.

Victor Chan, a co-owner and instructor at the company Chicago EMT Training, said, “You have the expectation [as a paramedic] of being the highest level of care when someone calls 911.” He explained that paramedics train for around

cardiac monitors, apply electrocardiograms (EKGs), and interpret heart rhythms to assess potential cardiac issues. In contrast, EMT-Bs are trained to use automatic external defibrillators during cardiac arrest, according to Chan.

Daniel Cronin, a doctor and professor at Northwestern University’s Feinberg

“We’re hearing from the city that they’re going to disband the whole program, so we’re not going to waste our time.” — Pat Cleary

a year, compared to three to five months for an EMT-B, or Emergency Medical Technician-Basic.

The two primary levels of EMT certification are EMT-Basic (EMT-B) and EMT-Paramedic (EMT-P). Often, EMTPs are just referred to as paramedics.

Chan said paramedic training “feels like a full-time job. You’re doing many more clinical rotations; you’re rotating through every ICU and many other rotations through various hospitals.” With that understanding, he said, the amount of medications that EMT-Ps work with “exponentially expands” from the approximately dozen that EMT-Bs are trained on.

EMT-Ps are also trained to use

or helping them up the stairs. EMT-Bs operate under basic standing orders and can perform CPR if someone is unconscious; however, they cannot “run a code,” meaning they cannot give directives or manage a cardiac arrest situation independently, according to Cronin.

“They don’t carry any drugs, they’re not trained on a cardiac monitor, things like that,” said Snyder. “And the labor rate that they’re offering was less than half what they’re paying a paramedic.”

One CARE EMT who replaced a fire paramedic, Kameron Younger, was hired on September 4, 2024. In January, Younger was charged with one misdemeanor count of possessing ammunition without a valid license. Younger was no longer employed by CARE as of spring 2025.

In March 2022, when Younger was a candidate to join the fire department, he threatened to shoot up the Fire Academy—a full-time, six-month training program for paramedics and firefighters.

“They were giving our work to other people, and the people they hired were people with bad histories,” Cleary said, then referenced Younger. “One guy was thrown out of our Fire Academy for having mental issues. He was one of the guys they hired. I’m like, ‘You’re sending this guy on mental health runs? He has his own issues.’ It’s pretty hard to get kicked out of the Academy.”

As of January 2025, the CARE program employed nine EMTs, according to a staff roster obtained by a public records request. Two had left in 2024, including Younger.

School of Medicine who is also a licensed paramedic, noted that paramedics in Chicago operate under physician oversight, which allows them to perform a wide range of medical interventions, as long as they follow standing orders.

“If I witness a psychiatric emergency, there are certain standards where an EMT-B would never be on scene for something like that. Two paramedics will be on scene for that, and then we can escalate. They would never put an EMT-B in that type of situation; they would call somebody else to be there," Cronin said.

He added that EMT-Bs are typically used for lower-risk transfers, such as bringing someone home from the hospital

According to a City of Chicago posting for the role, EMTs are expected to “perform patient care medical assessments to persons experiencing a crisis or problem related to unmet mental health, substance use, physical health, or social service needs.” The only listed requirement is “basic emergency and prehospital care training acquired through EMT training.”

Applicants must be certified EMTs; however, the posting does not specify the level or extent of experience required.

“This is really a question of medical care, and I know that the CARE team primarily goes to mental health emergencies,” said Snyder. “But many times, differentiating between what is a mental health emergency and what is really just a medical emergency that manifests itself with altered mental

status, sometimes, it’s hard to tell. We think the best person to do that is a paramedic.”

The fire union’s complaint alleges that the city made a unilateral change to a mandatory subject of bargaining—namely, substituting EMTs for fire paramedics on

CARE teams—without first negotiating either the decision or its effects.

“The process in which you go to the board and you file a complaint; you’re actually accusing the other party of breaking the law,” said Professor Robert Bruno, who runs the Labor Education Program at the University of Illinois, Chicago. “The firefighters are making the

case that this is work that’s covered under the collective bargaining agreement. It can’t be outsourced, and therefore it’s a violation of the agreement.”

In November, the Illinois Labor Relations Board referred the unfair labor practice to an impartial arbitrator, and then dropped the charge once the arbitrator ruled in favor of the city.

The ruling noted that: “The evidence indicates that the actual work that the paramedics on the CARE Teams were performing amounted only to very basic assessments to ensure medical stability or determine whether a Fire Department ambulance should transport the client”— so highly-trained paramedics were not necessary.

The arbitrator emphasized the fire department’s failure to recruit enough of their own paramedics to participate in CARE, and noted that “the city maintains that the effectiveness of alternate response programs is important in public safety reform, but the CARE Program cannot be effective if the city struggles to appropriately staff it.”

The CARE dispute comes amid

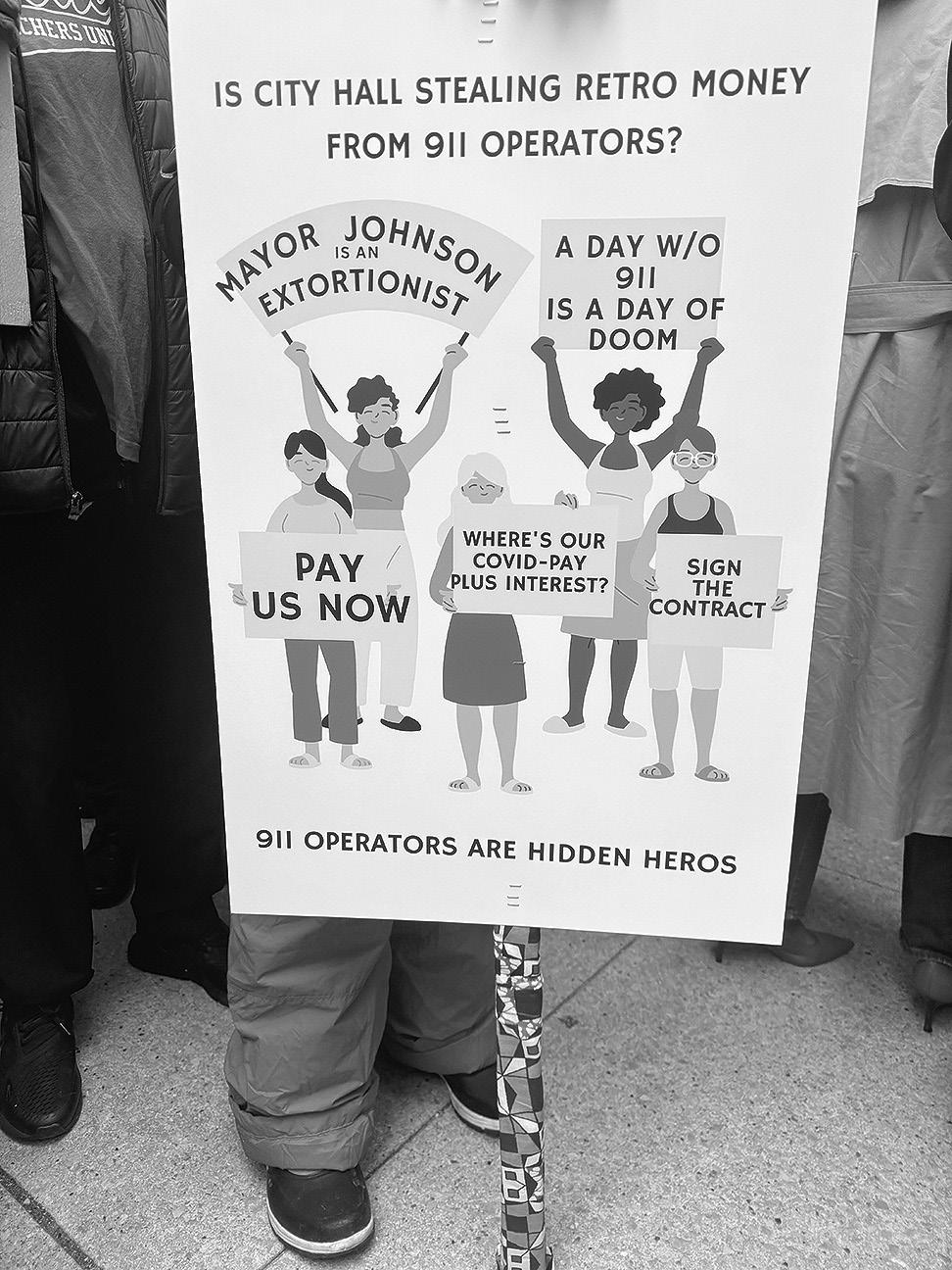

broader contract tensions between the city and the firefighters union. The firefighters’ collective bargaining agreement expired on June 30, 2021, and the parties spent months in arbitration to resolve the deadlock. A tentative deal was reached this month, which still needs to be approved by the union and City Council.

Cleary recently told Medill and MindSite News that CARE is not a priority at the moment, since the union is in a high-stakes fight over its contract. But he is adamant that any crisis response program must involve the fire department. He noted that New York City’s B-HEARD program includes union fire department paramedics.

“They’re part of the firefighters union in New York,” Cleary said. “Why wouldn’t this group (CARE responders) be part of the firefighters union?” ¬

Charlotte Ehrlich is a journalist and editor based in New York City. She’s an undergraduate of Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism.

When Chicago police fail to de-escalate mental health emergencies.

BY MAGGIE DOUGHERTY AND SKYE GARCIA

Charlotta Pritchett was four times married and divorced when Timothy Glaze asked her to marry him. And then he asked again. Both times she said no; she knew she did not want marriage again.

“Tell you what, can we be partners for life?” Pritchett recalls Glaze asking her. She agreed. “That was my partner. Little did I know, six years later, his life will be gone,” said Pritchett.

In front of the teal blue door that she used to walk through every day, eleven bullet holes served as a haunting reminder of the night this January when four police officers stepped off an elevator and shot Glaze sixteen times.

He was in the midst of a mental health crisis.

The officers were responding to a call for help, but when Glaze walked glassyeyed into the hallway, a knife in his hand, officers backed up, three with guns already raised. Within a minute, he was dead.

In 2024, more than 250 calls on average were made each day to 911 in Chicago about a possible mental health crisis, according to public records. The vast majority of these calls led to police being dispatched.

Chicago has sought to improve its response by sending mental health clinicians and emergency medical technicians through the Crisis Assistance Response and Engagement (CARE) program, instead of police, to mental health emergencies in certain areas.

However, recent reporting by MindSite News and the Medill Investigative LabChicago found the CARE program serves only a tiny slice of the city’s needs and appears to be in a state of retreat, rather than promised expansion.

Pritchett’s apartment in Little Village

fell outside of CARE coverage areas and her multiple 2am calls to 911 came after CARE’s 10:30am–4pm day had ended. Plus, Pritchett had never heard of CARE and didn’t request a mental health response.

Data obtained by MindSite News and Medill revealed that Chicago police used force to respond to mental health crises more than 400 times in 2024. The encounters occurred disproportionately in Black and Latino neighborhoods, echoing previous national findings.

Although non-Latino Black residents make up around twenty-eight percent of Chicago’s population, more than sixty eight percent of mental health-related use-offorce incidents involved Black subjects in 2024. Another seventeen percent of these incidents involved Latinos. These encounters were concentrated in West and South Side neighborhoods, which are predominantly Black and Latino. Black and Latino people were also disproportionately likely to be arrested during mental health crises that involved force from police.

The Chicago Police Department declined or did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story. The department said they could not comment on Glaze’s killing because of pending litigation, and in response to questions about use of force, provided a link to policies for responding to people in crisis.

Nationally, people with serious mental illness are eleven times more likely to experience force during interactions with police officers than those without mental illness, according to a 2021 article in BMC Psychiatry. In many cases, researchers say, police are ill prepared to recognize and address symptoms of mental illness. An

individual in crisis may act in ways that are unpredictable or frightening, or that may appear hostile or resistant to officers’ orders.

The mental health advocacy group NAMI, the National Alliance on Mental Illness, recommends deescalation—“reducing the intensity of a crisis or emotional outburst to achieve a positive outcome and keep everyone safe.” Intervenors should remain calm and use an even tone of voice, keep noise and stimulation levels low, move slowly and gently announce actions before initiating them, NAMI suggests.

“If officers come in running, whether it be guns blazing, aggressive, ‘we’re gonna stamp out this issue’ and barking orders to someone in crisis,” that can exacerbate the crisis, said Craig Futterman, a clinical law professor at the University of Chicago who directs the Civil Rights and Police Accountability Project. “Those have been proven recipes for disaster.”

When Chicago police employ any degree of force—from handcuffing to lethal force—they are required to fill out a so-called Tactical Response Report. MindSite News and Medill obtained these records for all of 2024 and the first three months of 2025 via public records request.

Although these records are supposed to include information on the subject’s mental state, officers frequently omitted this information in several violent interactions identified in press accounts as mental health-related.

That was the case in the fatal shooting of Timothy Glaze. Though ABC7 Chicago reported within days of his death that Glaze was experiencing a mental health crisis, nothing in the case file and officer reports released by the Civilian Office of Police Accountability (COPA) or other documents obtained by MindSite News and Medill noted Glaze’s mental state.

The most common type of force used in mental health situations was handcuffing and other forms of physical restraint. While

some cases, such less-than lethal weapons are used in situations where officers appear to see no other alternative.

In January, for example, police reported a Black man in his late twenties standing in the middle of a West Roseland intersection with a knife. The man began walking toward a squad car, blocking its path. When officers exited the car and ordered him to drop the knife, he refused and asked officers to kill him. For the next fifteen minutes, a kind of dance took place—the man

“I will never call 911 again in my life, because they took Timothy’s life. That’s not what it’s supposed to do.” — Charlotta Pritchett

less harmful than a weapon, handcuffs can cause damage to the soft tissue, nerves and bone structures of the hands and wrists. They also imply that the person has done something criminal, contributing to potential stigmatization or shame.

Chicago police officers were more likely to use a weapon in encounters with a person experiencing mental health symptoms than with others. In more than half of the cases where police used weapons against a person in a mental health emergency, the person was unarmed.

Tasers were the weapon most commonly used against people in crisis. In

would advance with his knife, then retreat backward as officers tried to convince him to disarm.

Finally, the man approached one officer protected by a sergeant holding a shield, and another officer fired his Taser, hitting the man twice and causing him to stumble backwards and drop the knife.

A sergeant used his shield to hold the man on the ground until he could be restrained and placed in custody. He was transported to St. Bernard’s Hospital for mental health evaluation.

Police records indicated that a review found the use of force to be “objectively

reasonable, necessary and proportional” and in compliance with the department’s guidelines.

A man in crisis

At the time of his death, Timothy Glaze’s body was riddled with cancer. He was rail thin, carrying only 137 pounds on his 6’1” frame, according to the autopsy report.

“I watched cancer eat him alive,” Pritchett said. “I would see him get out of the shower. It was a skeleton getting out of the shower with skin on it.”

Adding to the emotional turmoil of facing his mortality, Glaze struggled with his mental health in other ways. He told Pritchett that he’d been diagnosed with manic depression, better known as bipolar disorder. She described days when the two of them would be enjoying time together, and suddenly a cloud would come over him. And that, she said, is what happened on the day he died.

Throughout the day, he kept picking up a knife and carrying it around absentmindedly. When she would ask him why, a confused look would come over his face and he would set the knife down, only to pick it back up again a few hours later. Eventually, he sat next to her on the couch, again holding the knife. But this time, he didn’t want to put it down and would not listen to reason. Pritchett grabbed a screwdriver, just in case. She didn’t think Glaze would try to hurt her,

In 2024, 911 dispatchers in Chicago recorded 28,822 calls to 911 regarding mental health issues including mental health-related disturbances and suicide threats and attempts. They logged another 67,796 calls as “check wellbeing,” a category that signifies possible mental health issues.

The police department itself recorded 58,656 calls for service—an average of 160 a day—that it designated as eligible for Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) service, indicating a mental health issue.

The police department also logs encounters that result in force by officers, and notes whether they include a mental health component. These records show 402 incidents in 2024 where force was used in a mental health situation.

That is likely an undercount, however; since officers don’t always note a mental health issue when one occurs. The Timothy Glaze case is an example. His girlfriend Charlotta Pritchett told MindSite News and other media that he had a long history of mental health problems, and he was acting erratically the night she called 911 for help. But the police report of Glaze’s killing by officers makes no note of mental health issues.

Medill and MindSite News analyzed reports on 402 incidents where police used force in responding to a mental health call. Our analysis showed:

• In forty-one percent of the occasions when police deployed force on people experiencing a mental health emergency, they arrested the person in crisis.

• Of the 166 people arrested, 143 were identified as Black, Latino or both. The vast majority of the 166—over eighty-five percent—were unarmed.

• In eighty-six percent of cases when police used force in a mental health situation, the person was hospitalized, often against their will. Officers are authorized to transport such people to a mental health facility with or without their consent to protect them or others from harm, according to department policy.

• When officers deployed a weapon during mental health crises in 2024, they used tasers 80% of the time. Past reporting by MindSite News and Medill has shown that tasers can cause long term damage, and in rare cases, leads to death.

• On at least fifty occasions last year, police data shows a person in a mental health crisis was injured by police before being hospitalized, by tasers or otherwise.

• Over eighty two percent of mental health force incidents resulted in use of handcuffs or other physical restraints. Of the 333 individuals handcuffed, only 139 were placed under arrest, meaning many were handcuffed when they had committed no crime. Of those people, forty-four were armed, generally with a knife or blunt weapon.

but recognized that he was not himself. And, she remembered, murder-suicide is a real thing.

At 2:08am, Pritchett called 911 for the first time. At the start of the call, Pritchett primarily addressed Glaze, telling him, “The police are on the phone.” She gave the 911 operator both of their names and the address. “We’ve both been drinking,” Pritchett said to the operator.

Three minutes later, Pritchett called again. This time, she was yelling. She told the second operator that Glaze, knife in hand, had trapped her in a corner and would not let her out of her bedroom. She told the operator that she had a screwdriver.

At 2:18am, four police officers stepped out of the elevator onto the floor of Pritchett’s apartment.

Officer Salah Saleh knocked on the door and announced their presence. The door swung open at his knock, revealing an empty entranceway.

Glaze walked out from the apartment, knife hand coming up and into view as he approached the officers.

“Woah,” an officer said. “Step back.” All four officers quickly backed down the hallway; only one did not aim his firearm at Glaze. The two in front, Saleh and Officer Alejandro Urbano Mateo, fired their weapons eleven and nine times, respectively.

Within three seconds, the two officers fired twenty shots. Sixteen bullets hit Glaze. Four struck his chest. Others hit his thighs, both arms and his stomach.

Four stray bullets traveled down the long hallway—past the doors of eight other apartments—embedding in the wall.

Saleh and Urbano Mateo flipped Glaze’s unresponsive body over to cuff him, hitting his head against the wall in the process. Only then did they call for an ambulance.

“I got blood on my hands,” Urbano Mateo said in the body camera footage.

Eighteen seconds after officers entered the hallway, Glaze was dead.

Pritchett heard the shots from a neighbor’s apartment, where she had taken refuge to wait for police.

“My blood just turned ice when I heard all the shots,” said Pritchett. Her neighbor looked at her and said, “I’m sorry, but your friend is dead.”

Glaze’s body was transported to Mount Sinai Hospital and he was declared dead at 2:51am.

Chicago has been under fire for decades for its history of deadly and non-deadly force against Black and brown individuals. In 2015, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) opened an investigation into Chicago police practices following the killing of Laquan McDonald, seventeen, a Black high school student who was shot sixteen times in the back as he walked away from police while holding a knife and acting erratically.

The DOJ found a pattern of civil rights violations by Chicago police including unconstitutional use of force, and in early 2017, the department and the city agreed to develop a consent decree mandating reforms. A week later, Donald

It further required that officers using firearms take “reasonable precautions” to protect subjects other than the target. As of December 2024, the department is in full compliance with only sixteen percent of the consent decree’s hundreds of requirements.

After Trump reassumed the presidency this year, he signed an executive order negating other cities’ police-related consent decrees. The Chicago consent decree, however; remains in effect and is overseen by an independent monitor. Despite the decree, police use-of-force incidents involving mental health have increased nearly sixfold over the past decade.

Two lives for the price of one

Timothy Glaze's death comes almost ten years after McDonald’s and the parallels are striking. Two Black men impaired by mental illness and intoxication, each holding knives, killed by Chicago police officers firing sixteen shots—although neither was an imminent threat to those officers.

Pritchett, who said she used to have a cordial relationship with police, no longer sees Chicago’s law enforcement system as serving her or other Black people.

“I will never call 911 again in my life, because they took Timothy’s life,” said Pritchett. “That’s not what it’s supposed to do.”

Trump assumed the presidency and his administration soon abandoned that effort.

Then-Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan stepped into the breach and sued the police department, resulting in the consent decree that tracks the department’s performance in multiple areas, including how it responds to people experiencing mental health crises. The decree also requires officers to de-escalate potential applications of force and encouraged the creation of an alternative to police response. Since 2019, the department has been required to reform how it trains officers, and to document and hold officers to account for their use of force.

“CPD officers may only use deadly force as a last resort,” the decree stated.

She now fears that if she leaves her apartment, she’ll run into the officers who killed Glaze. Both appear to be back on patrol in her neighborhood, since they appear again in police use-of-force data for March. Pritchett takes Ubers to the grocery store instead of walking and tries not to go out unaccompanied.

“I would want them to look in my face and know how you’ve destroyed me, how you’ve traumatized me,” Pritchett said of the officers.

Isaiah Jackson, an activist with the group Dare to Struggle, questioned why officers are allowed to return to patrol when COPA, the police review board, has not yet completed its investigation.

“If the investigation is ongoing, why are these people back on patrol?” Jackson asked. “What is the significance of an investigation if they’re allowed to return to work before you have the outcome?”

For months after her partner's death, Pritchett was faced with the memories of

the worst day of her life. For five months, the Chicago Housing Authority refused to move her to another empty apartment so she would no longer have to walk over the spot where Glaze was killed. She was finally moved to another building in late June after her attorney intervened.

Building management even asked her to pay for the damage to the hallway, Pritchett said, telling her that she was responsible for Glaze, as he was her guest.

Without Glaze’s income, Pritchett said, she is struggling to pay for groceries and other costs and relies on donations from a GoFundMe, which has had no new contributions since April.

In a recent interview, she described Glaze as a gentle soul and caretaker who would carry her groceries for her and do the cooking.

She played a video on her phone of Glaze dancing to music in the kitchen and showed photos of them together.

“He always did things like that to make me smile,” Pritchett said. “They’ve taken that smile.”

She wants people to remember him as she does.

A wrongful death lawsuit has been filed by the mother of Glaze’s two children alleging that “The City of Chicago has a custom, practice, and policy of ignoring the rights of individuals who are in psychological distress, escalating matters, and causing deaths.” Pritchett has struggled to find an attorney to represent her in a

similar wrongful death lawsuit; she is not a plaintiff in the suit filed by his children.

Now, Pritchett has joined activists from Dare to Struggle demanding that the city and Mayor Brandon Johnson acknowledge and provide accountability for the killing of Glaze and other victims of

In April, Johnson’s administration placed flyers around Pritchett’s building advertising a planned visit by the mayor to discuss safety concerns with senior residents. The flyers did not mention Glaze by name. Dare to Struggle and residents of the building organized a protest, but the mayor did not appear. Since then, the group has continued to seek explanation from Johnson about why the two officers are back on patrol. They’ve confronted the mayor at community meetings—and were escorted out by security on at least one occasion. Although she does not feel listened to, Pritchett said she is not giving up.

“He would be so proud that I’m trying to fight for what’s right, and that’s justice for him,” Pritchett said.

“I could almost see him sometimes, when I’m at the State Attorney’s Office and I’m talking about his life, I can almost feel him next to me saying, ‘Way to go, babe.’ You know, ‘let me rest in peace, because I’m not.’”

Additional reporting by Medill students Hope Moses, Ashley Quincin, Sam Biggs, Margarita Williams, Jasmine Kim, Tyler Williamson, Mariam Cosmos, Emma Sullivan and Charlotte Ehrlich ¬

Maggie Dougherty is a freelance journalist based in Chicago specializing in datadriven investigative journalism. She is also a graduate of Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, where she specialized in investigative reporting.

Skye Garcia is an investigative journalist based in New York City. She is a graduate of the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University, specializing in data and investigative journalism.

It’s that exciting time of year again—the highly anticipated Best of the South Side (BoSS) keepsake edition is on its way, and we invite you to be a part of it!

Your neighborhood—whether you’ve called it home for six months or sixty years—it’s yours. Now is your chance to celebrate it! At the Weekly, we believe that this year’s Best of the South Side issue will not only encourage our readers to explore uncharted neighborhoods but will also shine a light on the vibrant tapestry of our communities, the wonderful people around us, and the countless good deeds happening every day A true celebration of all the great things that happen in our communities every day

Celebrate the heart of our neighborhoods. Let our readers know what your company has to offer By becoming a trusted part of the communities, you will build credibility and become a valued member of the South Side of Chicago. Reach out to those most likely to become your patrons.

Don’t miss out—submit your ad by Thursday, September 18 and help us create a truly memorable edition. This remarkable South Side Weekly publication will be available to the public on Thursday, September 25, 2025.

Join us in making history on the South Side!

Last year, 169 police officers who received training used force at least once during a mental healthrelated incident in Chicago.

BY EMMA SULLIVAN

Every day in 2024, Chicago police officers were assigned to more than 100 emergency calls potentially related to mental health.

But despite specialized training meant to defuse mental health crises, public records obtained by Medill and MindSite News show that many officers—including those trained in crisis intervention and de-escalation techniques—still resorted to force.

The Chicago Police Department logs such calls from 911 operators as “CIT calls”—meaning they are eligible to receive a response from an officer who has received Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that a CIT-trained officer will be the one responding.

The department launched CIT training in 2004. The forty-hour program—now used by more than 2,700 police departments nationwide—is mandatory for CPD command staff and senior executives and voluntary for all other officers.

CIT-trained officers are more likely to connect people in crisis with some form of care, said Amy Watson, a leading CIT expert and a professor at the Wayne State University School of Social Work in Detroit. But many Chicago officers have not received CIT training. As of the end of February, 5,870 CPD officers, current and retired, had taken part in this training. There are currently 10,320 police officers on the force.

Even with CIT training, police aren’t the right responders for mental health crises, said Frank Chapman, executive

director of the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression.

“People who need to be treated need to be treated,” Chapman said. “They don’t need to be murdered and they don’t need to be traumatized. Too often the police show up and do the wrong thing. They’re just not trained to handle mental health crises and the experiences have been tragic.”

While CIT training is meant to help reduce the use of force in mental health crises, 169 CIT-trained officers in Chicago used force at least once during a mental health-related incident in 2024, according to records obtained by Medill and MindSite News.

A 2019 scientific review of studies on CIT training concluded that it tends to improve officer satisfaction and may help divert people from jails to psychiatric facilities. But the study, published in the Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, also found that there is little peer-reviewed evidence showing CIT reduces arrests, injuries, or use of force.

CIT training educates officers on how to recognize the signs of a mental health crisis by assessing behavior and using de-escalation techniques, such as avoiding sudden movements and validating people’s experiences. Officers also receive detailed overviews of various conditions like schizophrenia, mania, anxiety, and personality disorders, along with guidance on suicide risk and response.

While Watson hasn't reviewed CIT training materials in Chicago and Illinois, she said some curricula she’s reviewed are overly clinical and encourage officers to act more like mental-health professionals than first responders even though they lack actual medical training. While wellmeaning, this approach can be ineffective, she said.

“You may have officers trying to diagnose somebody,” Watson said. “If you’re focusing on somebody’s diagnosis, you might be missing what is actually going on with the person.”

Debunked “excited delirium syndrome” still in police training manuals

Materials used to train new recruits at Chicago's police academy have referenced "excited delirium syndrome," a debunked term that has been used by law enforcement to describe a state of extreme agitation and sudden collapse. It has been used as a defense by police officers accused of using excessive force but has been rejected as a diagnosis by medical societies including the American Medical Association. Studies have found that it has disproportionately been used to justify force against Black and Brown people.

The term ‘excited delirium’ “has been misapplied and diagnosed disproportionately in law enforcementrelated deaths of Black and Brown individuals, who are also more likely to experience excessive sedative intervention instead of behavioral de-escalation,” the AMA's policy reads.

A 2020 presentation for pre-service sergeants on bail-bond procedures notes that “a person who is in a severe emotional crisis or state of ‘excited delirium’ may not be able to comprehend or even hear attempts at de-escalation, which is based on a capacity for communication.”

Chicago Police Department officials did not respond to multiple questions from Medill regarding whether excited delirium is currently part of the department's CIT training curriculum or respond in a timely manner to a public records request for its most recent CIT curriculum.

The Chicago Police Department and Illinois State Police follow the same training guidelines and the Illinois State Police instruct about excited delirium in its CIT curriculum, which was obtained by Medill and MindSite News through a public records request. It outlines physical and psychological signs officers should

look for in order to identify excited delirium, including “intense paranoia,” “extreme agitation,” “rapid emotional changes,” and “superhuman strength.”

A February 2023 Illinois State Police CIT presentation included thirty-five slides on excited delirium.

Watson said the inclusion of excited delirium syndrome in curriculum is “alarming,” noting the lack of evidence for the condition and the opposition of the American Medical Association.

Bias baked in?

Watson said CIT programs can unintentionally reinforce racial biases within the force, noting that officers are more likely to interpret erratic behavior from white individuals as signs of mental illness, while perceiving the same behavior from Black individuals as criminal.

Chapman added that CIT training

isn’t sufficient because it doesn’t address the “military” culture of policing.

“If a guy is pulling out his cell phone and it looks like a pistol, you’re gonna kill him, because you’re not expecting him to pull out a cell phone,” Chapman said. “You’re expecting him to pull out a pistol. That’s the way you’re thinking.”

Chapman said the presence of police tends to exacerbate mental health crises in communities that are disproportionately impacted by police presence.

“When the police over a period of time come to represent the symbol of racist oppression in your community and you are a Black person in crisis and the police show up, you’re not seeing that as a friend showing up, as somebody showing up to help you, a compassionate person,” Chapman said. “You’re seeing that as somebody who is hostile to you, so that’s not going to diminish your problems. That’s going to enhance them.” ¬

‘We Can Walk the Journey With Them’: Another Way to Help

For Manuel Meza, the vice president of clinical operations at a mental health service provider named Thresholds, the need to link crisis response with long-term care is essential.

It’s also part of what makes two programs operated by Thresholds important parts of Chicago’s mental healthcare ecosystem. The Thresholds team responds to crises by offering de-escalation, stabilization and follow-up care.

Thresholds, a nonprofit organization, carries out this work through two programs: Its mobile crisis response team sends peers to assist people in crisis where they are. In addition, its Living Room program is a peer-led respite center where people can weather a mental health crisis supported by peers who have lived experience with the mental health system.

Chicago’s city-run CARE program also offers non-police response to mental health crises, though it is underfunded and serves only a small portion of people in need, according to a recent analysis by Medill and MindSite News.

“Everyone knows there’s no treatment in being put behind a police car,” Meza said. “There’s no treatment sitting at the station. What happens tomorrow? What happens tonight? When those symptoms come back—when the depression, when the loneliness, when the voices come back—what did we leave them with?”

Emma Sullivan is a magazine journalist and freelance investigative reporter based in Washington, D.C. She graduated valedictorian of the Medill School of Journalism’s undergraduate class of 2025.

Unlike most Chicago police officers, the Thresholds team tries to give individuals a concrete safety plan. While police may default to hospitalization or arrest, Meza said his team rarely has to take that step. He estimates that 97 percent or 98 percent of all cases that Thresholds responds to end without a hospitalization.

Meza attributes much of that success to the team’s peer engagement specialists. These are individuals with lived experience of mental health challenges who are trained as certified recovery support specialists. Meza said the use of self-disclosure, where peer responders describe their own experience, is a powerful tool when supporting someone in crisis.

“It just provides the extra level of empathy,” Meza said. “It provides the extra level of understanding. It provides the extra level of ‘I’ve been in your shoes and I know what that feels like.’”

Police do not receive self-disclosure training as part of CIT programming, and it would likely not be appropriate in their role. That’s one reason Meza believes it’s important for crisis response teams to include not just officers, but peer engagement specialists who can draw from lived experience.

“Not that we can fix their problems, but we can walk the journey with them,” Meza said. “And I think that’s something the CPD doesn’t have.”

BY JOSH MCGHEE, DANA BROZOST-KELLEHER, ISABELLE SENECHAL, SAM STECKLOW, JENNA MAYZOUNI, ALLENDE MIGLIETTA, STEPHANA OCNEANU

On a gloomy Sunday afternoon in Chicago, Sgt. Andrew Dakuras hopped out of his patrol car in front of a downtown highrise and strolled into the elevator, finishing a text as the doors closed. He rode up to the 31st floor, exited and stopped at the third door on the left. He knocked: tap, tap, tap, tap, tap.

“One second, I'm getting dressed,” yelled a voice from behind the door, captured on Dakuras’ body-worn camera. A minute passed. “Coming…”

When Janette Bass, a petite, fiftynine-year-old white woman, finally unlocked the entrance to her condo on this day in 2019, she also opened another door: one that led her to being taken against her will to a hospital emergency room for a psychiatric evaluation based solely on the decision of a police officer. That has now become an increasingly common event, one experienced by six Chicagoans every day, according to 2024 data gathered by Invisible Institute and MindSite News.

That summer day six years ago, Dakuras walked into disarray—dishes and pans scattered around the kitchen, papers paving the way to the dining area. Bass tried to tell Dakuras what happened.

The main water line broke in the building. A group of men entered her apartment when she wasn't dressed and refused to leave. She tried to complain and was banned from the building office. She called the police several times. She changed the locks on her door at a cost of $200. She finally filed a police report and now wants to fill in missing details, she said. Dakuras declined to sit and the conversation took a turn.

“Ma’am, if you talk to the detective, the detective can amend it,” Dakuras said. Growing agitated, he called the officer who took the original report. She’s

already talked to him multiple times, Bass told Dakuras. His voice grew louder. “Ma’am, I’m talking on the phone. Do not interrupt me.”

She tried to plead her case, then paused. “Don’t scream at me, sir. I’m the victim,” Bass said. Moments later, Dakuras ended the call and walked to the door to leave. She asked for his name and took a picture of him. He doubled back, but refused to file an additional report.

“Ma’am, are you in crisis?” he asked.

“Because of you,” she retorted.

“Are you under the treatment of any doctors?” Dakuras continued.

She told him to leave. He refused and radioed for an ambulance. “What hospital can I take you to?” Dakuras asked. “You can go one of two ways: you can go voluntarily or you can go involuntarily.”

Bass called a friend and told them she was being arrested. She’d ask the

officer to leave more than sixty times over the next four minutes as he followed her around the apartment. Then she fled.

“I felt I had nowhere to go,” Bass later told Invisible Institute and MindSite News. “I’m like a trapped rat.”

Dakuras chased her down the stairs and into the hallway on the 27th floor, threw her onto the ground by her shirt, and handcuffed her. “Janette, this is not how rational people act,” Dakuras said.

“This is not normal.”

Bass was taken to Northwestern Memorial Hospital for a psychiatric evaluation, then transferred to another hospital and held against her will for what she recalled as a "couple days" before being released.

The Chicago Police Department

handles over a hundred mental healthrelated incidents every day. Some end in arrests, some may lead to voluntary transport to medical facilities and some end with no action taken at all. But in recent years, data obtained by Invisible Institute and MindSite News shows officers are increasingly turning to a more controversial option: forced hospitalization, detaining people against their wishes at a hospital emergency room for a psychiatric evaluation.