Chapter

Chapter

South Kent School was conceived in early 1920 in the minds of Father Frederick Herbert Sill and George Hodges Bartlett. Fr. Sill had founded the successful Kent School in 1906, and was its Headmaster; Bartlett was a young teacher there. The men had a vision for a new private boarding school for boys based on the founding principles of Kent, although Bartlett’s ideas differed from Sill’s slightly in the details.

Fr. Sill was the son of an Episcopal minister who was “concerned about social conditions and worked hard for improving the lot of working people,” according to the written history of Kent School.1 Sill himself was a monk of the Order of the Holy Cross, an international Anglican monastic order that follows the Rule of St. Benedict. In founding Kent, he set out to establish an Episcopal Church school for boys whose families could not afford the tuition at the more expensive schools that were popular at the time. It was a risky approach, but it worked.

Several years later, in 1923, he was to write in a letter to George Bartlett’s brother Sam: “What we have at Kent, we learned by actual experience. The only thing that could be called an ideal was expressed in our Purpose…We were ‘to provide at a minimum cost for boys of ability and character who presumably on graduation must be self-supporting, a combined academic and scientific course of study. Simplicity of life, self-reliance and directness of purpose are to be especially encouraged in the boys.’ I have no idea when I put those last phrases together and I am sure at the time I did not realize their full significance but we have tried to make them real.” The two sentences became the Mission Statement and Trinity of Values of Kent School, and eventually of South Kent as well.

As Kent School entered its second decade, Fr. Sill began to worry about the increasing size of the student body, believing that the survival of the school depended upon his ability to be involved in all aspects of his students’ lives. He was not only headmaster, he also taught classes, coached sports and nurtured the boys on a very personal level, and so he wanted to keep the school at around 200 students. This meant turning away an increasing number of applicants, which was not easy for him and he fretted about it.

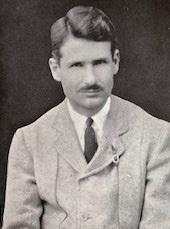

The answer to his dilemma appeared on his doorstep in the fall of 1918 in the person of George Bartlett, who was from Webster, MA, and a graduate of Harvard University. George’s younger brother Sam had just graduated from Kent, as had a Harvard friend named Roger Sessions (the well-known composer), so he had learned about this small, self-reliant school from them. George was a scholar, a musician, an athlete and someone with a mind open to change. While he was deeply committed to the basic principles of Kent, he saw room for improvement in the system. After joining the faculty that year, he quickly bonded with Fr. Sill and together they began to envision an expansion of Kent School through the establishment of other small schools, with the same principles, to handle the overflow. Fr. Sill, known to most people simply as “Pater,” wanted to put those schools nearby in South Kent, East Kent, North Kent and West Kent. George, however, was not focused on the location as much as on the substance of the schools. On May 20, 1920, he wrote a letter to his dear friend Roger Sessions, discussing his own dreams for a new school. “I am conceiving a plan at present which may prove the solution of the struggle within me as to what to do in the future. Kent has long been overcrowded and is becoming more sought after every day. When Sam leaves college I want him to help me establish a new school somewhere in New England in which the good things of Kent are perpetuated and some additions made. The greatest difficulty with the situation here at Kent is that the relation between headmaster and boys is one too much of personal affection. As long as the boy fits into the mold more or less completely he gets along beautifully and is made much of. Pater tries awfully hard to cram other boys, who won’t fit, into the mold and blames the boy rather than himself for the failure. There is no doubt that he is a great man, and, in many cases, a miracle worker, but he might go a step further and draw out the qualities which each boy has in him rather than try to stuff him with material he cannot assimilate. I certainly can make no more successful school than Kent, but I should like to have one where the unattractive and silent boy would have a better chance.”

To put this divergence into context, it is worth noting that 1920 is considered to be the beginning of the Progressive Era of education in the U.S. and abroad. Led by famed University of Chicago philosopher, psychologist and educator John Dewey, it was a movement which focused more on developing the individual needs and interests of children than on teaching by rote and dictation within a set traditional structure. New research in psychology and social sciences was expanding the understanding of how children learned and what they needed to grow into well-rounded adults. The concept of the need for active participation in a healthy community and the understanding that individuals must be recognized for their own merits were both a major part of the Progressive movement.2 Fr. Sill had already introduced some of the first concept with his Trinity of Values for the school community, but he was in his mid-50s and very busy with the job of running the school at this point, so probably was not as attuned to the latter focus on the students’ individual merits.

George, on the other hand, was young, brilliant and inquisitive about new trends, so he was quite willing to take the next step beyond his mentor.

But tragedy struck before the step could be taken. Later that same year, George’s heart, weakened by childhood rheumatic fever, began to fail him. The family tried everything, even taking him to France for treatment, to no avail. George died on May 3, 1921, just 24 years old, and for a while it seemed like the dream had died with him. But in 1922, George’s younger brother Sam graduated from Lafayette College, and returned to Kent School to teach. Heartened by this turn of events, Fr. Sill began to revive the dream of a new school, determined to turn it into a reality, right in his own valley in northwest Connecticut, with Sam at the helm instead of George.

He needed a partner for Sam, because he knew that Sam was not quite as well-rounded as his brother had been. Yet he trusted his former Head Prefect completely and loved him like a son, as he wrote on Sam’s June 6, 1918, diploma. “My own boy Samuel Slater Bartlett, dear to me as a son. This is your diploma as a graduate of Kent School. I am sorry I am obliged to state the fact that I don’t know how we can get on without you; and who can take your place. I am deeply grateful for all that you have done for me. You came here as a small boy and for seven years you have given Kent your loving service. I know that you are going to be one of our great men. Try to show your love for the dear Saviour who gave himself for you by leading a life dedicated to his Honour and Glory. May God bless you — your loving Pater, FH Sill OHC”

Fr. Sill’s hunt for a partner for Sam turned out to be easy. Sam’s roommate, fellow prefect and best friend at Kent, Richard Matthei Cuyler, had taught for one year at Kent before heading off to Princeton in the class of 1923. Fr. Sill knew he would be the perfect balance for the energetic, sports-minded Sam, whose famous ancestor Samuel Slater (inventor of the first manufacturing mill

in America) had instilled in the family a reverence for physical labor. Coming from an aristocratic Southern background, Dick Cuyler had a sharp intellect, as well as respect for eccentricity and artistic creativity, and so would be well-equipped to handle the academic side of life at the new school. He also was a superb athlete, which was important to both Sam and Pater.

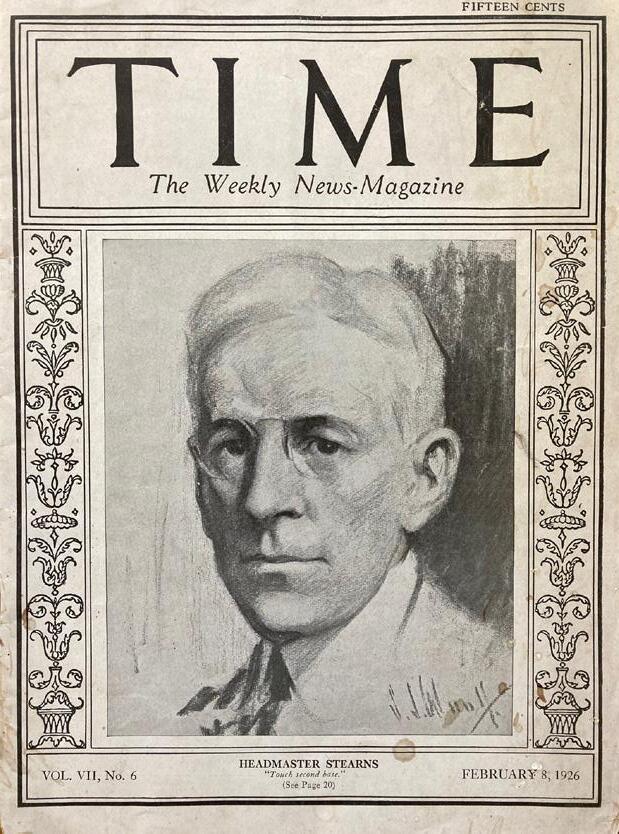

In 1926, TIME Magazine did a cover story on the headmasters of notable New England private schools. After learning about such legends as Dr. Drury of St. Paul’s, Dr. Peabody of Groton and Dr. Thayer of St. Mark’s, readers of the magazine turned the page to see a picture of the “Youngest Headmaster, Samuel S. Bartlett.” The article discussed the origins of the school with Fr. Sill, and went on to say, “The headmaster of South Kent is Samuel Slater Bartlett, a 26-year-old New Englander now four years out of Lafayette College. Keen, vigorous, a young man of many interests and opportunities, he determined to make the school his career. His fellow prefect, Richard M. Cuyler, graduated by Princeton in 1923 with a high record, made the same choice and took the post of dean and registrar. Four other recent college graduates (Harvard, Lafayette and Princeton) soon joined them, and there is building today, not only a school, but another specific tradition of teaching that will reach out to other schools and back to the colleges.”3 It is ironic that Sam very quickly was dubbed the “Old Man” by South Kent students, an affectionate nickname that would stay with him for the rest of his life.

In late December, 1922, Fr. Sill made his move. In 1947, the Pigtail, South Kent’s student newspaper, featured a regular column called “Early Days,” which described what happened next. “Pater finally descended from the hills of Kent with a light in his eye, summoned Sam Bartlett from his home in Webster, Mass, where he had gone to cut wood for the winter, snatched Dick Cuyler from some tea dance which he was attending as part of his extra-curricular life at Princeton, and sat down to a weighty conference at the Columbia Club in New York. What actually transpired at that meeting is now somewhat hazy, but Pater was soon able to convince his two promising wards that they should renounce the marts of the trade and embark on a new adventure in a strange and alien

field.” Not only was it a strange and alien field, but Pater wanted it done right away, by September of the very next year!

The incubation period from December 22 to the September 26 opening day was full of frantic activity and planning. They had to search for a site for the school and simultaneously begin raising funds to buy the property, renovate it and fully equip it before opening the doors for the fall term. Sam began a diary during this process, and the second entry describes their visit to the quiet South Kent hamlet known as “Pigtail.” After investigating a few locations elsewhere in town, the entry for Sunday, April 8, 1923, says “F.H.S [Sill] and S.S.B. [Bartlett] journey to S. Kent in the Hup [Hupmobile car] and look over prospective sites. The barns and brook on the Straight farm were in favor of the place while the shore front and general location of the Judd farm were greatly in its favor. F.H.S. was much impressed as I had been at the beautiful views at the top of the hill. On our return F.H.S interviewed Mr. Johnson [a local real estate dealer] about purchasing the Judd farm and plans were made for Mr. Judd to see F.H.S. on Tuesday or Wednesday.” The diary entries continue:

“April 11/23, Mr. Judd and Mr. Johnson interview Pater at Kent. Mr. Judd’s price is $12,000 and F.H.S. writes to a man putting it up to him.”

“April 21, 1923, Dick comes up from Princeton and we go down to S.K. He is as much impressed with the place as I was.”

“April 28/23, Pater hears from Mr. Rives of Washington, D.C., that he will give enough to buy the Judd farm. Great rejoicing in camp.” The purchase was made.

The John Judd farm, described in 1897 as “one of the largest and best farms in the town of Kent,”4 included an old ten-room farmhouse, barns, a lakeshore and many acres of land on which Fr. Sill envisioned athletic fields for a variety of sports. It also included a farmer named Martin Tomasovski and his wife, Louise. Martin, whose name was pronounced “Marteen,” quickly proved himself to be a critical part of the successful transformation of the farm into a school. Martin and Mrs. Martin, as they were called, would settle into a routine with Sam and Dick, teaching them about the crops that the school would continue to grow for its own sustenance (and for income, in the

on the Hillside 1923-2024

case of the annual tobacco harvest), as well as helping out on the grounds and in the kitchen and laundry.

First, they had to assess the condition of the house itself. Fr. Sill brought in contractor H.H. Taylor of New Milford, who did much of the work on the Kent School buildings, to see what needed to be done before the house could be converted into a space for a dormitory, classrooms, offices and more. Taylor decided that the chimneys and roof were in bad shape, but that the rest of it was pretty sound.

The May 3, 1923, diary entry goes on to say, “As for an athletic field the piece of land north from the house beyond the lower hay barn was considered the best. The springs will always provide ample drinking water while it will be a simple matter pumping water from the lake.” Sam would soon find out that providing any kind of water was not a simple matter at all, but they did eventually surmount those difficulties in true South Kent self-reliant fashion.

The next entry addressed an equally important issue — what to do with the farm. “May 15, 1923, Went to S.K. with Mr. Judd and went around the boundary. Much larger than I expected. Talked with

Mr. Judd about tobacco, potatoes and his man Martin…On consultation with F.H.S. in the evening, it was decided to start with as near a clean slate as possible. Therefore for the first year we will buy all potatoes and our milk. Although the tobacco might bring in $300-400 it was thought too risky and requiring too much labor to take a chance on. I am to see Mr. Judd and tell him of the decision and also see that Martin understands. I must see Dr. Barnum [head of the local power company] about getting electricity over to S.K. from Bulls Bridge.”

“May 17, 1923. I went to see Mr. Judd and Dr. Barnum this morning. I told Mr. Judd that it would be impracticable for us to try to grow anything for a year or two and that it would be just as cheap to buy our potatoes and milk. He was very nice about it and only wanted Martin to be allowed to take in his potatoes, wheat and possibly some tobacco. He is a fine man to deal with. Dr. Barnum was also most cordial and said that… he thought it would be easy to have the poles put over to S.K. A few other people want it and among us it should pay in a few years.”

In spite of the decision not to get involved with planting tobacco and potatoes, by May 27th they had decided to do just that, most likely because of assurance from Martin that it could work. Mr. Judd and other friends gave bushels of seed potatoes for the first planting. On June 4, Sam noted that they had planted 11 ½ bushels with help from some friends at Kent School. That may have been the very first tradition established at South Kent School because harvesting the potato crop continued to be an annual all-school project and source of great pride for the boys for many decades to come. Tobacco, however, was eventually discontinued, in spite of its being a good cash crop.

At the same time, Sam was also working with Fr. Sill on a “circular letter” to be sent out to prospective students’ families, and hoping that he would be able to find the right man to teach mathematics. Plans for the renovation were being developed with a Mr. Sylvester and interviews with the first potential student applicants were conducted. He noted that Mrs. Ransom had come to look at the school and was “rather apprehensive about her boy getting in.”

Meanwhile, Mr. Taylor was scheduled to set to work on a variety of projects on July 1st, the most important of which was adding a significant addition to the old house in order to provide the various necessary rooms. Plans were quickly drawn up. With Mr. Rives’ $12,000, a mortgage was secured, and Sam wrote in his diary on June 21st that Taylor had actually started work that morning. He noted that he also was looking for a house for Mr. and Mrs. Martin, and still pursuing the power company to get the electric lines strung from Bulls Bridge — haggling over the cost per pole. And, as if that were not enough, he was going

to New York the next day to ask someone named Jack Wallace for financial help. A few days later, he went down to New Haven to buy a new 1923 Ford Drop-side pickup truck, which quickly became an indispensable tool on the developing campus, along with Martin’s elderly but sturdy team of horses, Susie and Helen.

The middle of July found busy Sam back in the fields with Martin and a Kent School student, spraying potatoes, sawing wood and pitching “tons” of hay. The hay was to be a cash crop that might sell for as much as $20 per ton the following spring. It is clear that they were working every angle possible to raise enough money to meet the September 26th opening day deadline. But they had a bit of great news on that front. Fr. Sill, who was doing the bulk of the fundraising, had cannily struck a major deal that netted $10,000 for the new school. The 1947 Pigtail described it well: “It seems that at that time a Mrs. Bessie Kibbey came up to Kent to enroll her nephew in the school. Finding the school already overcrowded, she expressed regret and said that she had always prayed that her nephew might one day enter Kent. Pater thought the matter over carefully and came back with the rejoinder that it had always been his prayer the he could get $10,000 to get a school started down in the valley and he allowed as how if she would answer his prayer, he would answer hers. And so it was agreed.”

Throughout this frantic time, Dick Cuyler was finishing his studies at Princeton, so was not available to help with the intense amount of on-site work to be done. While he and Sam had kept in touch, it must have been a real relief when Dick was finally able to come north at some point in August, joining Sam who was still living on the Kent School campus. His arrival was a great comfort, and the pair set to work to put the finishing touches on the school. Sam’s last long entry in his diary before the actual opening of the school was dated Sept 16, 1923. In it, he noted that the power lines had been installed and that they hoped to have electricity in a few days; that Mr. Taylor was finished with the buildings but that the plumbers and steam fitters were not; that Martin and Mrs. Martin had agreed to work as farmer and kitchen helper; that he had moved his office to S.K.; that he had hired Miss Clara Dulon to act as house mother; that they had twenty boys

enrolled and finally that he and Dick had moved to the school. He wrote that they had tried washing in the horse trough, but because that was a bit chilly, they were “reserving their ablutions for Kent.” He expressed great respect and admiration for Martin, Mrs. Martin and Miss Dulon, a faith that was to be borne out daily as the new school grew and matured. All three were major fixtures in the lives of the South Kent School boys for a long time to come.

Sam had also hired Stanley Goodwin to teach mathematics and Theresa Wortman to be the cook, and so had a staff of seven ready to meet the charter scholars ten days later. There was still much to do. The Pigtail history has this glimpse into the evening of September 25th: “The night before the school opened the staff was busy indeed. Sam Bartlett and Dick Cuyler with Stan Goodwin were still unpacking bureaus by the light of the moon in the front courtyard, while Miss Dulon was putting the finishing touches on the kitchen department…It was only after the staff had finished its work and was sitting out on the front porch in the cool air and wondering what was in store for them the next day, that Dick Cuyler happened to remember that, after all their efforts at stocking the place, there was not a book in the school. That evening before turning in the staff took one last look around the grounds and tried to figure out whether or not there was anything else that they had forgotten. Books could be ordered but everything else had to be in good shape. True, the plumbing was not all that could be desired and there were a few minor deficiencies elsewhere, but they felt safe in starting off although a bit apprehensive.” South Kent School was born the next day, when Sam, Dick and Stan became Mr. Bartlett, Mr. Cuyler and Mr. Goodwin, and stood on the porch of the farmhouse, waiting with Miss Dulon to greet their charter scholars.

The role that Fr. Sill played in the establishment and success of South Kent cannot be overstated. He functioned as intimately in the process as he routinely did at Kent. He raised tremendous amounts of money, recruited students, and gave advice on a daily basis, often on-site. Once the school opened, he served as Chairman of the Board of Trustees for many years, and as substitute chaplain and teacher on many occasions. He also often brought over his Kent School sixth formers to give advice and support during the early months of school, especially the first night when they helped to tuck 24 very young boys into bed before heading back over the river to their own dorms. Perhaps Fr. Sill’s biggest contribution to Sam personally was the regular, lengthy letters he wrote to his young friend as their journey proceeded throughout 1923. The letter quoted above was the first of a long series in which Fr. Sill spelled out in great detail the steps

he had taken to establish the institutions, traditions, programs and community that were flourishing at Kent, and gave advice to Sam about how to best profit from that knowledge. Though the Kent — South Kent relationship was never a legal one, the founding principles were identical, and Sam freely instituted at South Kent much of what had been instilled in him as a student at Kent, right down to the Mission Statement and Trinity of Values that are the bedrock of both schools.

Fr. Sill’s greatest gift to the school was his focus on the Chapel. South Kent was founded on strong Episcopal principles, and the Chapel, both physical and in essence, has been a centering force since the very first day when a service was held in the schoolroom. This influence has continued today even as the student body has expanded to include many other faiths. The question, “What is a Church School?” has been addressed repeatedly throughout the school’s history. In 1963, Headmaster Wynne Wister wrote that a simple answer would be that a “church school has a chapel with regular services and all the boys take a course in Sacred Studies.” But he then discussed in detail the way the Christian spirit would permeate every aspect of life on campus, citing concern and respect for fellow community members, leadership by example of both faculty and students, hospitality and sportsmanship in athletic competitions, and responsibility for one’s own actions. Mr. Wister’s thoughts echoed those of Fr. Sill and Sam Bartlett as they had discussed it in 1923. Fr. Sill wrote to Sam that the greatest goal was to have the graduates leave school as “upright, reverent, unselfish men,” and even suggested a daily voluntary morning Eucharist. He urged Sam to set an example by always attending the service himself. Their objective was to have the Christian lessons combine with the progressive ideals on classroom education and spill over into athletics and the rest of community life. As Sam would later write in the 1927 yearbook, “Without the Chapel, South Kent would not be South Kent.”

People in the quiet little hamlet of Pigtail in South Kent, Connecticut, watched with curiosity as a straggling parade of unfamiliar cars made its way up the twisty dirt road towards the brand-new South Kent School throughout the day on September 26, 1923. These neighbors had seen all the frantic activity going on over the previous four months at the old Judd farm, with some of them actually lending a helping hand with the preparations. Pigtail was about to acquire 24 new residents, from all over the country. Today was the big day.

Curiosity, along with a healthy dose of nervous apprehension, surely was felt as well by the growing cluster of young boys in knickers, who, having bid tearful goodbyes to their families, began to take in their new surroundings. Bits of building material and plumbing supplies cluttered the yard, and a new flagpole lay flat on the ground, awaiting the time when it could be placed upright and the flag hoisted. But the school building in front of them shone with a fresh coat of paint, and the barns and fields around them held the promise of many places to explore. The new grownups in their lives, Mr. Bartlett, Mr. Cuyler, Mr. Goodwin and Miss Dulon, hiding their own apprehension, greeted them warmly and began the process of settling them in.

Diary entry for September 26, 1923: “School has started. I cannot quite state my feelings. At times I feel utterly incapable of the job and then again I feel very confident. MacManus and Ward came in early yesterday spending the night at the Inn with their mothers. Today all the boys come except for Crawford whom we are to hear from. Thompson’s grandmother nearly caused a scene saying she couldn’t bear it, etc. Our first meal went off in fine style, the boys turning to and helping immensely. We had our first chapel in the schoolroom and sang ‘The Son of God Goes Forth to War.’ The boys are now in bed. Dick and I are sitting in the office talking things over. He is a great help and I don’t know what I would do without him. The [Kent] Sixth Form just called up from the Study and bid me good night. May I have a Sixth like that someday. Crawford is not to be entered. Financial reasons.”

By the boys’ own account, written several years later in the 1928 yearbook, “school started off with a bang the first night. The air in the dormitory was virtually thick with missiles of shoes, slippers and the like.” Those 24 charter scholars were Aaron, Brown, Buckingham, Colt, Cumming, deCoppett, Dingwall, Gilbert, Gustafson, Harris, Hazen, Kimball, McManus, Meyer, Murphy, Newhall, Ransom, Schurz, Stevens, Thompson, Ward, White, Whitney and Woodward, entering the Second and Third Forms. They were to be joined in January by four more boys: Balch, Gillette, Simpson and the very young 11-year-old Files, who was often quite homesick. The Second Form was the equivalent of eighth grade, with the average second former being 13 or 14 years old. As the school grew over the next three years, Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Forms were added, with the Sixth Form being the equivalent high school senior class.

The concept of self-help was introduced right off the bat, with the boys pitching in to get the first dinner on the tables and washing up afterward. Dinner consisted of scrambled eggs cooked by the Headmaster, and was followed by the first chapel

Balch came to School halfway through the year, lugging his own bags up Spooner Hill from the train station, thus learning his first lesson in self-reliance. That and the next lesson of simplicity of life must not have agreed with him because he did not stay long enough to graduate.

service, held in the classroom, at which they sang, “The Son of God Goes Forth to War.” The altar was a packing box topped with a cross made of a couple of sticks, and the congregation was made up of two masters, the Housemother and three boys who knelt on the floor between the desks. The next day, instead of heading for the classrooms, the boys were given shovels and rakes, and put to work alongside the masters to help get the yard cleaned up and tidy. Part of the reason may have been that the main classroom was still full of plumbing supplies, and also the fact that there were no books to be had! But soon they all started to settle into the beginnings of routine, with classes, chores, meals, athletics and chapel. The boys were very young, however they learned very quickly that much was expected of them as integral players in getting the new school up on its feet. Though the old farmhouse had been doubled in size, the school building was packed tight. The third floor held the dormitory, a washroom with showers and lockers, and rooms for Mr. Cuyler and Mr. Goodwin. The dorm rooms were so small that most of the boys did not have their own dresser in which to store their clothes, but there was a large one down the hall that they shared. A small, rudimentary infirmary was on the second floor, along with rooms for Miss Dulon and Mr. Bartlett. The first floor housed the dining room, classrooms, reception room, living room with a makeshift library, and finally the kitchen and other utility rooms. Eventually, space for a chapel was created in a room in the basement. The 1929 Class History spelled out the truly spartan conditions of the first few years: “Our study-hall was what is now a supply room. In the winter the temperature in this room went down to fifteen degrees above zero, and classes were held in mittens and sheepskins. The blackboard was only a large piece of card-board which soon became useless as every chalk-mark scratched off the paint.”

In the beginning, all aspects of running the school were done by the same few people. Teachers doubled as coaches, dorm masters and even business

managers, while Mr. and Mrs. Martin and Miss Dulon took care of just about everything else, usually with the help of the boys. As the school grew in later decades, the workload came to be distributed over many more-focused staff positions, but at the start, the self-help system with the boys was a true necessity as well as an educational goal. There was no set job program at first, yet there was no end of work for the boys to do. Mr. Bartlett noted in his diary, “Miss Dulon has proved herself a gold mine. She is a wonder and there is nothing she cannot do. The boys and the parents think very highly of her… Stan Goodwin has without doubt proved a success. He has all the boys at his heels and his table is continually in a roar of laughter… Of course Dick is the stump to which I always tie my ship in case of storm. He is working harder than any of us.”

It took a while for the academic aspect of the boys’ education to get started. The editors of the 1928 yearbook wrote about the earliest days, “Although we didn’t appreciate it at the time, we practically had a holiday for the first two weeks of school but we soon were put to work in the classroom.” Mr. Bartlett taught history, while Mr. Cuyler taught English and Latin and Mr. Goodwin taught mathematics. The next year they were joined by Fr. J.H. Kemmis, who was able to add the necessary French classes as well as lead the chapel services. In 1925, Lewis “Buzz” Cuyler, brother of Dick, joined the faculty to teach English and Latin. The faculty increased slowly over the years, and by the time the school completed its tenth year, there were eight faculty members, and the classes included history, English, Latin, mathematics, French, Spanish, physics and chemistry. One of those eight was William. P. Gillette, a member of the Class of 1929 and the first of a great many alumni who returned to teach.

Mr. Bartlett noted in his diary during the first year that there had been complaints about the lack of music instruction. That lack frustrated him, but he knew that he couldn’t do it all right away. His main focus was on getting the right people on the faculty, and so the subjects offered varied a bit over the decade, depending on the skills of the individual masters he decided to hire. One such example was Albion Patterson,

who joined the faculty in 1927, taking over the French instruction from Fr. Kemmis. An article in a January, 1928, issue of the Pigtail proudly announced, “One of Mr. Patterson’s French exams was seen by a teacher at Lawrenceville. This teacher made the following statement: ‘I believe that many college graduates would be unable to pass this.’ It is interesting to note that there were three flunks in this exam, while six passed, one of which passed was an 83.” Mr. Patterson was clearly a good teacher, and was popular with the boys as well. Mr. Bartlett had made a good choice.

A significant addition to the faculty was Samuel Woodward, who arrived in 1926. There is an amusing anecdote about his hiring that shows the careful scrutiny to which Mr. Bartlett subjected his potential faculty members. During the summer of 1925, Woodward arrived in a large Cadillac to interview for a position at the school. He was dressed in a natty fedora and an elegant suit, with two beautiful ladies on his arms. He was not hired. He drove back up Spooner Hill a year later, alone, in an old Ford, and got the job. “Woody,” as he quickly became known by all, taught history and English and would eventually become the school’s skilled and wily business manager whose talent for finding WWII surplus supplies, ranging from water pumps to faculty housing, will be discussed in a later chapter.

Classes were held in the morning, after chapel, breakfast and jobs. There was a recess in the middle of the morning, and then study periods after lunch and supper. Everyone was required to attend the full hour and a half evening study period, which seemed to be quite a trial for the youngsters in the beginning.

The May 28, 1928, issue of the Pigtail includes an item titled “STUDY PERIOD,” which describes the less-than-productive use of that time: “Macomber in a weird position leaning against the wall, Kimball with his eye shade and drawing instruments, Thompson with a broad grin walking in from a conference with a master, Sherwood opening a window, Dudley shutting it, Owen throwing a wad of paper in the general direction of the box, Harris putting it in, Borgstedt and Macomber shoving away moths and June bugs, Campbell trying not to smile, Sproule sucking a finger, Rice studying.”

Perhaps that portrayal was only in jest, but by the following fall, the faculty had decided to make some changes. The new plan allowed boys with marks over 75% to skip the evening study period. Those under 75% had to stay for an hour, and then could leave if they wanted to. The faculty felt that the shortened times

“Woody”

would encourage the boys to knuckle down and “exert all their efforts on the given work” instead of getting bored and messing around.

The faculty was also paying attention to the percentage marking system that had been traditionally used at Kent, and so instituted at South Kent. In the fall of 1927, they declared that there was too much emphasis being placed on achieving a high number just to pass courses when the boys had been sent to South Kent for a life-impacting education. So, they introduced an experimental new system for the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Forms that awarded an “S” for a satisfactory academic performance, and “U” for those who fell short. By 1931, however, the marking system had reverted back to percentage points for all forms. Marks were given out monthly to the Second, Third and Fourth Form, and twice a term for the two upper forms. The boys had to send a letter home every Sunday, and were expected to include their marks monthly. Not completely trusting that the boys would do so, the school also sent them out to the parents a few days later. Mr. Bartlett would announce the marks, ranking the forms in order of performance and noting the top-ranking student and members of the Honor Roll. He also gave a holiday when the overall percentage reached a certain level.

On the flip side, he announced in February, 1927, that for every point under seventy in the school average, one day would be lopped off their upcoming spring vacation. They had a scant five weeks to pull their grades up — another example of teaching them to put their community’s interests ahead of their own. This led to an amusing advertisement placed by a business-minded student in the Pigtail: “YOUR BEST FRIEND WON’T TELL YOU, but it is easy to raise those grades if you know how. APPLY MODERN METHODS TO YOUR WORK. Our PSYCHOLOGICAL system has proven its worth. We guarantee success or your money back. SEND FOR FREE INFORMATION. PSYCHOLGICAL INSTITUTE. P.O. Box 9, South Kent School, South Kent, Conn.”

An academic hammer hanging over the heads of the Fourth and Fifth Forms every year was the dreaded College Boards, standardized tests that anyone who wanted to enter college would have to pass. High marks during the school year would give parents an idea about their sons’ chances of passing the College Boards. After the Prize Day ceremony was over, those boys who did not want to go on to college went home, leaving the others to study hard during the “Cram Week,” after which the tests were taken at Kent School. Not until then could they, too, go home for a well-deserved summer break. Cram week was abolished in 1930, after extensive debate over how much students really retained in that short intense study time. The feeling was that the students should work hard all year long to truly absorb what they were being taught, rather than just filling their heads with facts and figures during the aptly-named Cram Week.

For the first year, the duties of the chaplain, including the teaching of Sacred Studies as well as leading the various chapel services, were carried out by Fr. Sill and Fr. Alan Whittemore, also from Kent School, and by Mr. Bartlett himself, each filling in as the need arose. Fr. Kemmis was hired the next year and stayed until 1929, during which time he played a very important role in the boys’ lives. A member of the class of 1933, Alexander Hamilton, said that Fr. Kemmis “was an Englishman who spoke with an Upland accent but it was quite clear. He was a very kindly sort and was understanding of growing boys.” The early school movies show an active, happy man, teaching the boys to play cricket, riding one of the school’s huge work horses and generally keeping spirits lifted in whatever way he could. Between 1929 and 1931, two more chaplains came and went, likely because the pay was low and the workload heavy. Fr. Sill and Mr. Bartlett once again had to share the duties until a steady replacement could be found. It was worth the wait. They found Fr. William Robertson, a retired parish priest, who loved working with the boys, and was able to get them more involved in the chapel service by taking turns reading the scripture in front of the congregation. He also enjoyed telling ghost stories in the dorms after “lights,” and regularly gave teas in his rooms.

Doug Borgstedt’s early cartoons appear in the 1928 and 1929 yearbooks. A keen observer of the human race, Doug went on to have a prolific career as a nationally recognizable professional cartoonist. After college, he drew cartoons for the Saturday Evening Post, and became its cartoon editor and then its photography editor. In the army during WWII, he helped design Yank magazine and was its first editor. Later his cartoons were syndicated in over 90 newspapers and magazines, including the New Yorker, Saturday Evening Post, New York and Esquire magazines, and were featured in exhibits at the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum.

At the time of Fr. Robertson’s arrival, chapel was held in a small room in the basement of the Old Building. It was next door to the room with the showers and lockers, which led

to Fr. Kemmis’s famous crack, “At South Kent, cleanliness has always been next to Godliness.” Fr. Kemmis and Miss Dulon worked hard to beautify the little room, and managed to acquire an organ to accompany the singing. The Pigtail editors bemoaned the access to the chapel: “Sliding down precipitous stairs into the cellar with the coal bin to our left and the furnace to our rear, we sidled past the cistern, which is now the Sacristy, to our benches.”

A chapel bell, given to the school in memory of George Hodges Bartlett, was mounted in the belfry on the roof, and rung by a rope that hung down into the third-floor dorm. The 1928 yearbook editors described the daily service: “This service is the acme of simplicity and beauty and is held every evening before supper; a few moments of quiet, a hymn, and a few prayers, how delightful and sincere.” They also noted that the need for a permanent chapel was obvious to everyone, and it was hoped that fundraising would begin soon. It did.

Dismayed by those precipitous stairs and the cramped quarters in the dark, damp basement, Fr. Robertson fully supported Mr. Bartlett’s desire for an actual chapel building, and immediately set about helping to raise the needed funds. He and Mr. Bartlett made trips to New York, and he also encouraged the boys to do their bit in the effort. An architect was hired, and by the fall of 1931, the foundation for a fine new chapel had been laid. Lack of funds prevented any further building that year, but the effort continued in earnest, and by the spring of 1933, construction began again. Sadly, the elderly Fr. Robertson had retired, but his contribution to the Chapel in his two short years was enormous.

The October 13, 1945, issue of the Pigtail began a series of articles about the principal buildings of the School, and, fittingly, started with the Chapel: “In the spring of 1933, they were just short of the amount they had set as a goal so it was decided that the construction should start. Forty of the older boys volunteered to do the heavy work such as hauling brick and mortar. They were divided into groups of four and worked one

day every two weeks. Towards the end of the Spring Term, with Father Sill and Father Mayo present, the cornerstone was laid. A copy of THE PIGTAIL, a school list, and the names of the boys who worked on the Chapel as well as the contractor and the foreman were put in the cornerstone, which Mr. Bartlett and Mr. Cuyler sealed. The next fall the boys returned to find the Chapel completed.” The boys were proud of their role in the construction, no matter what it was, as Sandy MacPherson, ’37, later remembered, “Usually my job was to push a wheelbarrow. It would be full of sand, or dirt, or bricks, or trash. Sometimes I toted a load of lumber.”

In addition to an official Chapel, there was another aspect of life for the boys that Mr. Bartlett felt right from the start was critical, and that was the sense of family. He encouraged his young teachers to consider marriage and children, and set the example by marrying Carol Mead as soon as school got out in June of 1925. Carol moved from a comfortable Westchester County, NY, existence to the extremely spartan situation at South Kent. They lived in his small apartment over the common room. There was no kitchen, so she cooked on a one-burner counter-top stove and washed the dishes in the bathtub. She was immediately put to work wherever help was needed, including assisting Martin and his team of horses get the tobacco crop planted. When the babies began to arrive, the apartment was clearly cramped. But there was no other available housing yet, so the school built a curious contraption known as either “The Carbuncle” or “The Incubator.” Their son George later described the Carbuncle: “It was sort of a window-greenhouse kind of thing, and that is where the baby lived. One time on a cold winter night, they put my sister Mary out there with a ham — just to keep the ham cold — and the next day the ham was frozen, but luckily my sister was alive.” Everybody on campus adored that little baby girl, Mary Spaulding Bartlett, so her survival was greatly celebrated. The

Carbuncle was detached and re-installed in other school buildings as more babies were born over the next several decades.

In 1926, Mr. Morehouse brought his bride to campus, and they lived in a small apartment in the recently-constructed New Building. Two summers later, in 1928, Mr. West and Mr. Bagster-Collins were both married, and the Wests moved into the newly acquired Straight House, which had been bought the previous year. Mr. Woodward was married on December 18, 1930, to Elizabeth Hall (one of the two beautiful ladies in that Cadillac in 1925). Carol Bartlett and Betty Woodward, joined in 1934 by Dick Cuyler’s new wife, Ellen Walker, were to become the quintessential surrogate mothers for decades of South Kent students. Much was asked of them, but they could always be depended on to rise to every occasion with grace, kindness, humility and hospitality. In his Fiftieth Anniversary Weekend Address in 1973, Headmaster George Bartlett had this to say about the three women: “Can you imagine the number of cookies and cakes

these ladies have baked? The number of tea cups they have filled? The number of bruised young spirits they have comforted? Most of all, can you imagine the kind of patience it took to bring up the families all by themselves, while their husbands centered their attentions, night and day, on other people’s children? Ladies, we have taken this all completely for granted… our debt to you is infinite; our gratitude is imperfect but none the less sincere.”

In the summer of 1930, a separate house was built for the Headmaster and his growing family, and the Bagster-Collinses moved into the apartment vacated by the Bartletts. That same year, a small cottage was also built for Fr. Robertson, again with manual labor help from four boys. It was set beyond the Chapel at the brow of the hill looking down over the Straight House, and thus began the expansion of the faculty housing across the combined farm properties, truly knitting the campus together. When Fr. Robertson retired in 1932, Mr. Cameron and his new bride moved into the cottage. These moves were the beginning of a long tradition of faculty housing “musical-chairs” during summer vacations, driven largely by the arrival of new babies and the departure into the adult world by maturing “Faculty Brats,” as the offspring soon became affectionately known.

To round out the atmosphere of family on campus, a nod needs to be given to the Faculty Dogs, who roamed freely around the courtyard, classrooms, dorms, fields and ponds. The early school movies show several dogs, helping or interfering with all sorts of activities, or just resting on the front porch with whoever happened to be sitting on the benches at the time. The very first dog mentioned on campus was Barney, who died in May 1924, according to Mr. Bartlett’s diary. She was found dead on the shores of Hatch Pond, where she presumably was killed as she tried to chase away some intruders that had been breaking into cabins in the woods farther down the lake. The early school movies show several other dogs, including a litter of puppies, and

Underpinning everything at the School from the very first day was the staff, which at the time consisted of just Miss Dulon and Mr. and Mrs. Martin, plus Mrs. Wortman in the kitchen. Sam relied on them just as heavily as he did Dick Cuyler. Miss Dulon was known to both Sam and Dick, since her brother taught at Kent School. She was a lay nun — an associate of the Order of St. Anne — which explains the sharp eye she kept on the Chapel and how it was operated through a series of chaplains in the first decade. She willingly and cheerfully did whatever was needed, from sweeping and scrubbing floors to planning all the meals. She was even known to cook special birthday dinners for students.

Miss Dulon was a surrogate mother to all of the students, and probably to the early teachers, who were themselves just barely out of college. She also functioned as the school nurse for the first couple of years when there was no nurse and no real infirmary. In the spring of 1925, some of the students tangled with some poison sumac vines while dismantling an old stone wall. To handle the ensuing outbreak of miserable boys, she turned both her room and Fr. Kemmiss’ into a makeshift infirmary and tended to them until they recovered. She also befriended a rather tragic neighbor of the School — Florence Maybrick, the convicted (but pardoned) murderess known locally as Mrs. Chandler. Miss Dulon made sure that the boys paid regular visits to the impoverished old lady down the road, bringing her food and supplies, and carrying in her firewood — a lesson in love and compassion that they never forgot. Perhaps Miss Dulon’s most visible accomplishment was her committee known as the Gardeners who enthusiastically kept the school grounds not only neat and tidy but also full of a wide variety of flowers. The committee did not continue after her death, but the custom of having blooming gardens was kept going by Martin as best he could.

Miss Dulon died on June 3, 1933, in New York City, where she had been hospitalized with cancer. Her body was brought back to South Kent, and the school bell tolled for her as the hearse made its way up the drive. At some point in the 1990s, Sandy McPherson, Senior Prefect of the Class of 1937, wrote down his very clear memories of her passing so many years before: “Clara Dulon became ill during the ’32-’33 year. She was sent to New York City for diagnosis, and remained for an operation. Mr. Bartlett kept us up to date on Miss Dulon’s progress, during our morning assemblies. After a few weeks, he reported that the doctors said the case was hopeless, and about a week later, he announced that she had died. When she passed on, her body was brought back to South Kent in a gray casket. It was placed down in the old Chapel in the basement, near the altar. The faculty, wives and friends were in and out of the place all day arranging flowers and doing everything they could to make things nice. The students went about their business, classes, sports, activities, jobs and routines. They all knew that Miss Dulon was lying in a closed casket, down in the Chapel, but they were working according to schedule. However, Mr. Bartlett announced that a “watch” at night would be held for Miss Dulon in the Chapel. A list was posted for volunteers to sign up, two boys at a time, at one-half hour intervals during the night to sit with Miss Dulon. I signed up and was posted for 2:AM with a boy named Beers. I was 13 and Beers was 14. My alarm went off. I pulled on some clothes and joined Beers. The building was pitch black. We creaked our way down the stairs and across hallways to the Chapel. It was all lit up with candles. Two boys were waiting

for us and they silently made off. Beers and I genuflected our way into a pew. We couldn’t take our eyes off that coffin. So we sat there with Miss Dulon, guarding her and being near her. For one half hour of our young lives, Beers and I were doing something very adult and very important. We were keeping watch. The next day, funeral services were held in the little Chapel in the basement, and then Miss Dulon was buried on the hillside next to where the new Chapel was being built.” It was the first major loss for the tight-knit South Kent family, but it must have been a comfort to all to have her there with them, right by the new Chapel building that meant so much to her.

Mr. and Mrs. Martin were equally devoted to the school grounds and to the boys themselves. The always-smiling Louise did the laundry in the beginning, and worked in the kitchen with the students who were lucky enough to get kitchen duty, while Martin kept the old farm thriving. Sam’s decision to go along with that effort may have been one of the wisest he made. Before the first decade was out, the Stock Market crashed, but South Kent was well supplied with its own food which could be harvested with “Boy Power,” and so the school barely skipped a beat. From the beginning, Martin was everywhere, often with his trusted teams of horses, first Susie and Helen, and then Frank and Katy.

Martin’s biggest contribution to South Kent School is legendary, and without it, the School could not possibly be what it is today. In 1927, the adjoining Straight farm came on the market. Sam had never forgotten it since the day that he and Fr. Sill had come to South Kent to look at prospective locations for the school. He remembered the orchard, the barns, the brook, the fields, but did not have the money to buy it. The asking price was $10,000, a great deal of money for the fledging school. Martin came to him and said that he thought the School ought to buy it. He had lived there previously when he was a farm hand for Miss Helen Straight, the owner who had just passed away, so he knew this second farm intimately as well. Sam said the School couldn’t afford it. Martin calmly replied that he had $10,000 and he wanted to lend it to the School to buy the farm. With that very generous gesture,

the size of the campus doubled, with new faculty housing, plenty of ground for new athletic fields, and several barns, one of which could store the School’s tobacco crops. That barn would later become famous as “The Playhouse,” home to some extraordinary SKS dramatic productions and hilarious Halloween skits.

There was nothing about the farmland that he didn’t know, including the various temperamental springs upon which the school depended for drinking water. That knowledge was frequently put to the test until finally in the fall of 1928 a large water tank was installed up on top of the hill connected to a 15-horsepower pump down at the lake. The next year, an emergency arose with the new water system, and Martin again came to the rescue. Alexander Hamilton was at the time Manager of the Pump at Hatch Pond. His job was to keep the big water tank at the top of the hill full. He later described the scare: “All of a sudden one Monday morning there was no water. Of course, I was looked at very dimly and somebody checked the lake I guess, and the valve was properly closed. Then they got Martin. He knew the countryside here, and he got a crowbar and went walking south of the New Building toward the Straight House and all of a sudden he went to his knees. The pipe had broken and drained 35,000 gallons out underground without anyone seeing the water. Of course, all they had to do was close the valve, take care of the broken pipe, start the pump, and we had water in an hour or so.” Martin had saved the day again, and would continue to do so until he and Louise retired in 1958.

Martin was also responsible for the arrival in 1930 of another long-time loyal staff member, his family friend from the Old Country - Victor Deak. The young man was from Martin’s hometown in Czechoslovakia, where he was prone to getting into trouble. His mother contacted Martin to see if he could find a job for her wayward son. Martin pitched the idea to Sam, saying that they’d have to meet the boat in New York and bring the 18-year-old Victor straight to South Kent, lest he find his way into the big city and get into even more trouble. Sam agreed, so Martin made the trip to the docks, and brought back a devoted hard-working assistant who would leave his own mark on campus in many ways. Victor worked on the farm as long as the School kept it going, and then shifted his attention to the grounds around the school buildings, mowing the grass, planting trees, building bird houses and doing whatever else he felt was needed to keep the place beautiful. As had Miss Dulon, he especially loved flowers, and planted them everywhere, including the famous “Kiss Me Over the Fence” that he delighted in putting behind the split rails along the walk up to the New Building.

The staff position of cook proved to be a challenging one to fill. Theresa Wortman was hired in the very beginning, but by the third year, she had been replaced by Mrs. Namit, who in turn left in rather short order. Comments in the early Pigtails suggest that she had not enjoyed trying to feed the hoard of hungry teenagers, and they had not enjoyed her fare. They were happy to see her go. The “Early Days” column in the Pigtail had this description of one turnover: “It was during this Winter

Term that the great Amberg arrived to take over his duties in the kitchen following the departure of Mrs. Namit. He was a fabulous character and in due time featured in many of the now old legends of the hill.”

Few of the legends have survived the ages, but there is one worth relaying because it describes not only the character of Mr. Amberg, but also the total involvement of the entire school community in producing the precious tobacco crop. Again from “Early Days,” about the summer of 1926: “The tobacco crop was tended early and often that summer and there was a great friendly rivalry between Martin and Chef Amberg who was doubling on the farm that summer. He was a tremendous man of great strength but he was not quite on to all the ways of farm life and as a result Martin would win most of the battles. When it came time to cut the tobacco there would be an unannounced race between Martin and Amberg, and Martin with slow steady strokes would always best the heaving Amberg who would use up most of his strength with unnecessary motions… While the tobacco was being stowed away in the barn Martin would usually be at the top of the barn taking the great shocks of tobacco from Amberg who would lift them up while standing up on the wagon. Frequently while Amberg was precariously situated Martin would give a slight cluck with his lips and the horses would start out usually depositing Amberg on the barn floor. All hands turned to help with the crop and even the ladies took their tour of duty.”

Chef Amberg left some time the next year, and was replaced by “Uncle Charlie” Taylor, who stayed for the rest of the first decade. Taylor’s skill in the kitchen was greatly appreciated by the boys, with several references to the details of his Thanksgiving dinners being made in the Pigtail. He was from England and liked to try out oddly-named English dishes on his captive diners. Like Amberg, Taylor took part in community efforts at School, most notably in a project to raise money by making ginger beer, another English staple. He wanted to buy a set of pewter plates for the dining room, and figured that if everyone on campus chipped in to help make ginger beer, it could be sold for a tidy profit. The faculty families were all given the ingredients and instructions, and some of their resulting ginger beer turned out to have a rather high alcohol content. Some bottles blew up, and others were enjoyed even by the boys who got their hands on a gallon or two. It was a successful venture, financially, and Uncle Charlie’s pewter collection was displayed in the dining room for decades, though it is now stored away.

South Kent also went through a number of nurses in the early days. Miss Dulon had keen nursing instincts, but she had no official medical training. The school needed a skilled nurse on campus and so, in 1925, hired Miss B. L. Dickinson to care for sick boys in the Infirmary which had just been established on the second floor of the main building. She was succeeded the next year by Miss Stanis Hoyne, who stayed for only two or three more years before leaving. By 1929, the Infirmary had been dubbed “Little America,” most likely a reference to the Antarctic base camp established with the same name that year by Admiral Robert Byrd. It suggests a rather remote and chilly environment, and no doubt was not the most comfortable place for sick boys or their nurse to be. Mrs. James was next in the short list of early nurses, and the last to preside over Little America. She apparently gave it her best effort, but for the sake of the School, it is good that she decided to move on, because the woman who replaced her in 1930, Amy Lyon, became another of South Kent’s revered figures in the lives of the students, the faculty and the rest of the staff for decades to come. Mrs. Lyon was from Scotland, where she had been designated a “Queen’s Nurse,” in recognition of her dedication to the highest standards of nursing practice. Her signature official blue cloak, with its red lining and a Queen’s Nurse pin on the collar, was the only outward indication that this tiny, modest, but tough woman was something truly special. Mrs. Lyon arrived the same year that a new infirmary was built, with nurse’s quarters adjacent to the infirmary room. She quickly established herself as a force to be reckoned with, fiercely protective of her patients, who did her bidding with no questions asked… ever. She was famous for her tea and home-made Scottish scones, served with proper formality in her tidy quarters, and later in the equally tidy little cottage built for her right next to the Infirmary.

The final lady to join the South Kent staff was Miss Christine Bull, who came at the very end of the decade to take over the business management duties vacated by Stan Goodwin when he retired at the end of the 1931 school year. As the school grew, Miss Bull kept a keen eye on the business dealings and developments on the Hill, eventually being joined by many other ladies fulfilling secretarial and management duties.

The ever-cheerful Miss Bull.

Last but not least in the line of hardworking staff members for at least the first decade of South Kent are the horses! Martin’s old team of Susie and Helen worked valiantly for three years, doing everything

from plowing fields to scraping the ice on Hatch Pond for the hockey rink. Upon their retirement in the spring of 1927, they were replaced by Frank and Katy, a pair of huge black Percherons, who stood so tall that the top of the frame of the barn door had to be cut away to allow them to enter. Eventually, more gas-powered assistants were acquired, but Frank and Katy, then Nellie and Bessie, and finally Prince and Princess, continued to be Martin’s preferred help until he and the last team retired in 1958.

By the fall of 1925, the school had grown to the point of having boys in the Second through Fifth Forms. It was time for the faculty to plan to hand over much of the leadership in running the school. In the spring of 1926, a full Student Council was appointed. It consisted of a Senior Prefect and three other Prefects from the rising Sixth Form, as well as two members of the rising Fifth and Fourth Forms. Also appointed were the Inspectors of the Main Building, the Dining Room and the Infirmary; a Superintendent of Plants and Structures; a Manager of Cooperative Stores; a Manager of Rolling Stock and a Manager of the Water Pump. The Council took care of all the routine daily activity, including study periods, job assemblies, bells, inspections, discipline and lights out. This gave the young men significant power, but they could be reined in by the Headmaster when needed. The students themselves were aware of the challenges of wielding such power. A thoughtful Pigtail editor mused, “This school has run, is run, and will continue to be run along independent ideas of responsibility and self-government. What then happens, if one of these self-governing boys puts a friend before his first obligation to the school, there is a fall which affects first the individuals concerned and ultimately the school itself.”

By 1931, each class chose its president for each year, to augment the Council. The Editor of the Pigtail that fall wrote, “The election of form presidents and council members is a vital part in the self-government organization of the school. This school, like its predecessor, Kent, is based on ideals of self-reliance which are most substantially attained by this movement.” Fr. Sill expressed in a letter to Sam that both schools needed to “knock out a sense of entitlement to privileges just

because they are sixth formers. Their one privilege must be to serve the school community. A good Sixth Form means a good school.” He also stressed that there needed to be a strong friendly relationship between Headmaster and Sixth Form, and suggested regular Sixth Form teas as a tool for achieving that goal. Those teas with Mr. Bartlett are mentioned by graduating class after class as a truly wonderful experience.

All but the most egregious instances of misbehavior were handled by the Sixth Form. Official punishment ranged from the issuance of a specific number of hours of manual labor to actual paddling with a wooden paddle. Though this latter practice is looked upon with horror today, and is illegal in most of the United States, in the first half of the twentieth century it was very common. Because schools were considered by common-law to be “in loco parentis,” paddling was considered a fair and rational form of discipline5. A variety of tools were acceptable, with the wooden paddle being the most benign. Hand-spanking did exist but was much less common. In fact, Sam wrote in his diary that he was not in favor of spanking. He did not note any objection to paddling, which suggests that his views on that subject were in keeping with the relatively widespread acceptance in his day. There is frequent mention in many yearbook class histories of paddling, always related in a matter-of-fact way that makes it clear that it was common practice. The 1934 Class History has a humorous take on one misadventure involving several of their class, early in their Second Form year, ganging up on one unfortunate boy: “The second day here, we persuaded him to chin himself on the chapel bell rope with disastrous results both to the peace of the countryside and to the seat of Chapman’s pants.” The last paddling at South Kent occurred in the fall of 1943, and its recipient, Ralph Woodward, ’47, described it thus: “Paddling was administered with a foot-long wooden paddle. Two solid strokes (not very painful) were applied to my bent-over buttocks…the punishment was regarded by me and my dormmates as a badge of honor.” But the latter part of the twentieth century brought change to boarding school discipline as medical, pediatric and psychological research showed that paddling produced little benefit and possibly caused lasting damage. Shockingly, it took until 1977 for the U.S. Supreme Court to address the issue, and now the laws regarding corporal punishment are set by individual states, with all but a few having outlawed it.

At South Kent, not all discipline involved such drastic measures. The “stinging” of hours of manual labor was accepted and respected by the boys. One of them wrote in the Pigtail in 1929, “One of our many blessings at South Kent for which we might consider ourselves fortunate is the hour system for correction. An hour like a demerit (the prevailing form at present) is a form of punishment for any offense, from being late or tardy at an assembly, to fooling in study hall. The material difference, however, is that a demerit is merely placed in record against a boy’s name and if too many of these marks pile up, he is forced to leave the school. Whereas the hour means that the boy having one must do some constructive bit of work towards the welfare of the school, and this task

is assigned by a student of the graduating class who has absolute charge in this department…After this chore is finished to the satisfaction of the upper former, the slate is clean.”

Sometimes the Headmaster carried out the punishment. In one instance, several boys had gone skating without permission, breaking a cardinal safety rule, so he made them sit in the school room for four hours to think about it. Another time, some miscreants were put to the task of washing all the windows on the first floor of the building. He regularly reacted to slug-a-beds, who refused to honor the rising bell, by running through the dorm flipping their beds over, dumping them abruptly on the floor.

He also, on very rare occasions, convened a “Who-dun-it” if some misdemeanor had occurred and the identity of the guilty party was not known. The whole school was summoned to the school room, where they were required to sit with hands clasped on desks, waiting for someone to confess. Charles Marvin, ’31, remembered the events clearly, saying that the boys “sat, silent and motionless, until the guilty party broke down. They were evidently counting on underground knowledge and peer pressure to do the trick. After a couple of squirming hours of this, it was not uncommon for several students, independently of each other, to rise simultaneously and ‘confess’.” Ralph Woodward later wrote, “More often than not this worked, but if, eventually, the Who-Dun-it was called off without a result everybody felt the burden of disappointment and failure and guilt. There was a skunk (no hero) among us.”

In general, however, the responsibility of discipline was solely that of the Sixth Form, with the goal of teaching them the responsible leadership that was an essential part of their South Kent education, as it still is today.

The Job System was a critically important part of teaching the boys community spirit and responsibility. By carrying out daily assigned chores, some by nature menial or distasteful, they learned that their own individual performance was critical to the success of the whole school. At no time in their lives would everything always go the way they wanted it to, so they might as well pitch in with their heads held high to do whatever was needed to help their community.

In July of 1927, a reporter from the venerable Hartford Courant came to interview Miss Dulon for an article about the self-help The

system at Kent and South Kent. That reporter was clearly smitten with her, for he titled the section “The House Mother with the Happy Laugh.” The article continues, “The door was opened by the pleasantest little woman in the world with such a happy laugh that we wickedly desired to ask as many questions as possible to hear her talk…The housework jobs, Miss Dulon explained, are classified into skilled and unskilled labor. Dishwashing, if you please, is skilled labor and a favorite. It calls for an hour all at once. When you have washed your last dish or hung up your towel you are through for the day. Unskilled labor demands half an hour both morning and night. You find where you are as to jobs bright and early in the morning by consulting the bulletin posted by the head prefect. There you find your name with a number opposite. Get your number and you have your job…All the housework that the boys do has been analyzed into units that can be done in an hour or half hour.”6

Popular jobs included that dishwashing spot, called by one Pigtail writer, “the most choice job… an honorable school office.” The menial jobs were given to the younger boys, and almost everyone looked forward to building the skills that might land him on the dishwash crew or working in the laundry. Alexander Hamilton said in an interview many years later, “I came here as a very immature child and became a fairly adequate teenager with an increasing sense of responsibility…By my Fifth Form, I ran the Laundry. The Laundry was sorted here because it was cheaper, and then sent to the Danbury and Troy Laundry (also known as The Destroy). When it was returned it was sorted and put under the name of the individual student. Everyone got a towel on Wednesdays and Saturdays and got a clean sheet on Saturday. You were supposed to turn in your dirty ones. The School owned the sheets and towels.”

Fr. Sill encouraged Sam to be honest with the boys about the School’s finances and how much their hard work was needed, saying that it would teach them self-respect and self-reliance, and keep all boys on the same level. “In luxury-loving and easy-going days, it seems to me that we are on the right track in giving our boys the chance to share in a life which is robust, healthy, simple,

virile, common sense and wholesome, and I think that the typical American boy deserves the chance.” Sensible advice for a new headmaster starting a school during what would come to be called The Roaring Twenties!

In addition to the official daily jobs, there were work projects carried out by the schoolboys. Miss Dulon quickly realized that there were some who were not interested in athletics, so she gathered them into a group called the Gardeners. Together, they set to work cleaning up the last detritus from the Judd farm operations, planting flowers and turning a chicken coop into a beautiful flower garden (near where today’s kitchen is), with a trellis and chairs for relaxing. Their mission was to make sure that the campus always looked attractive. They raised money to buy their tools and supplies, and became so financially adept that they were able to buy a “motion picture machine” with which to entertain their schoolmates on weekends. The Gardeners became indispensable to the community, with the 1930 yearbook noting that “they have made paths, laid flagstones, sodded bare ground, made roads, planted trees, emptied the ashes and, in short, cleaned up for us for seven years.”

There were other special work projects carried out by more than just the Gardeners. In February, 1928, Martin corralled a number of boys to go down to Hatch Pond, where an enormous new ice house had been built on the opposite shore to store big blocks of ice, cut from the frozen lake to be shipped south to New York City. Martin taught the boys how to cut the blocks and load them onto a sleigh which was dragged by the two new school horses, Frank and Katy, up to the School’s ice house on campus. Two less-pleasant but necessary jobs were done annually when the local train delivered a car-load of either manure in the spring for the farm fields or coal in the fall for the furnaces. All hands turned out to shovel the dirty contents into the wagons that were hauled up the hill by Frank and Katy or by the old Ford truck. The early school movies show the boys, caked with muddy clay, digging ditches to drain the future athletic fields and planting potatoes by the bushel. They also helped to harvest the important cash crop of tobacco each fall until the school discontinued the tobacco growing. There wasn’t much that they didn’t learn how to do.

The biggest Boy Power accomplishment was the building of the new entrance road in the winter of 1926/27, under the supervision of the Gardeners. Two stone walls were torn down, and the rocks

smashed to bits with sledgehammers, to which the boys quickly gave names such as “Leavenworth Special,” “Sing Sing Sport Model,” “Gerald Chapman Autograph” and more. The crushed rock formed the base of the road that is now the formal entrance to the school by the Headmaster’s house. Work “holidays” became a tradition that lasted for many more decades, with the Headmaster announcing that the boys would be given a day off from classes in order to carry out some necessary major project.

In discussing the slack period between the end of football season and Christmas vacation in 1931, the Pigtail editors wrote about the value of doing tasks around campus instead of lolling about on useless November afternoons. “This year, several groups of boys have spent the afternoons doing various jobs which are usually done on those only too-infrequent work holidays. The stone wall has been removed from the place where the chapel is to be situated. The dining room floor has been scrubbed by fifth form according to tradition and all the ‘public’ windows have been washed. All this work has been done by the boys whose labor has certainly become an integral part of the school life. So let us be up and doing, let us find something to occupy our minds; let us do something constructive each afternoon while November behaves like November.”

Somewhere along the line, the Sixth Form began the custom of returning to campus early each fall to clean up after the long summer absence and make sure that everything was ship-shape for the arrival of their younger charges. It was a chore which they took very seriously. The final verse of South Kent’s unofficial hymn says it all, “Come, labor on. No time for rest till glows the western sky, till the long shadows o’er our pathway lie and a glad sound comes with the setting sun: Servants, well done.” Those last three words are still received with a lump in throat and a feeling of communal pride by students at South Kent today - truly the watchword of the School.

There wasn’t much spare time in the first years, so extra-curricular activities were few and far between, aside from the Saturday night movies sporadically provided by the Gardeners. But after about five years, things began to change. Several boys were keenly missing music, which was not yet part of the academic curriculum, so at some point an informal singing group was formed, meeting in Fr. Kemmiss’ room. They were officially recognized as the Glee Club by the end of the 1929 school year, but did not survive for long after that. A band of sorts was gathered, featuring a saxophone and a couple of banjos, in the winter of 1926/27. In the spring of 1928, the Fourth Form organized a hamburger and hotdog roast on the shores of Hatch Pond at which “large quantities of hamburger, steak, hot dogs, ice cream, iced tea and marshmallows were consumed. The boys in that Form attended classes as usual the next day,” according to the Pigtail. The paper also reported on other informal activities, such as the organizing of the school library, which previously had been neither catalogued nor supervised, and the contributions by the boys and faculty of $115 to a fund to help a family on the other side of Hatch Pond rebuild their house after a fire. Another time, they actually went to help extinguish a fire on Leonard Pond just north of Hatch Pond. A front-page article of the Pigtail described in detail the two-day ordeal that involved all of the students walking over the hill to Leonard Pond to fight the fire. The School received a check from the State of Connecticut in thanks for the dedicated Boy Power.

An interesting new Saturday night activity began in the fall of 1929, when Mr. Bartlett reintroduced the Kent School program of Public Speaking, which had been practiced off and on at South Kent in the first two years. The Pigtail reporter wrote, “The two reasons which Mr. Bartlett gave for this innovation, which we think is very good, were, first, that it will give an opportunity to every boy in school to speak before a group of people, which is an excellent experience, and, secondly, that it will offer welcome relief from the weekly movies.” The article

goes on to list the wide variety of subjects chosen by the boys in the first two sessions, and closes by noting, “None of these speeches were marvels of rhetoric, yet on the average they were by no means bad, all things considered. They at least afford interesting examples of what the average fellow is capable of in this activity, and we look for improvement with experience.”

But in 1933, Mr. Eschmann, who had donated the first movie projector, gave the school a new “talking movie machine,” a DeVry portable projector, which allowed for the screening of the new movie format. The first movie shown was “Phantom Express,” and the students all agreed that it was a great step forward, since the movie was only a year old. They also were able to see sports reels such as the Notre Dame — Southern California football game, and current news events. One Saturday they even watched all eight reels of the first Sherlock Holmes talking picture. From then on, Movie Night and Public Speaking were in fierce competition for best Saturday night entertainment.